Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

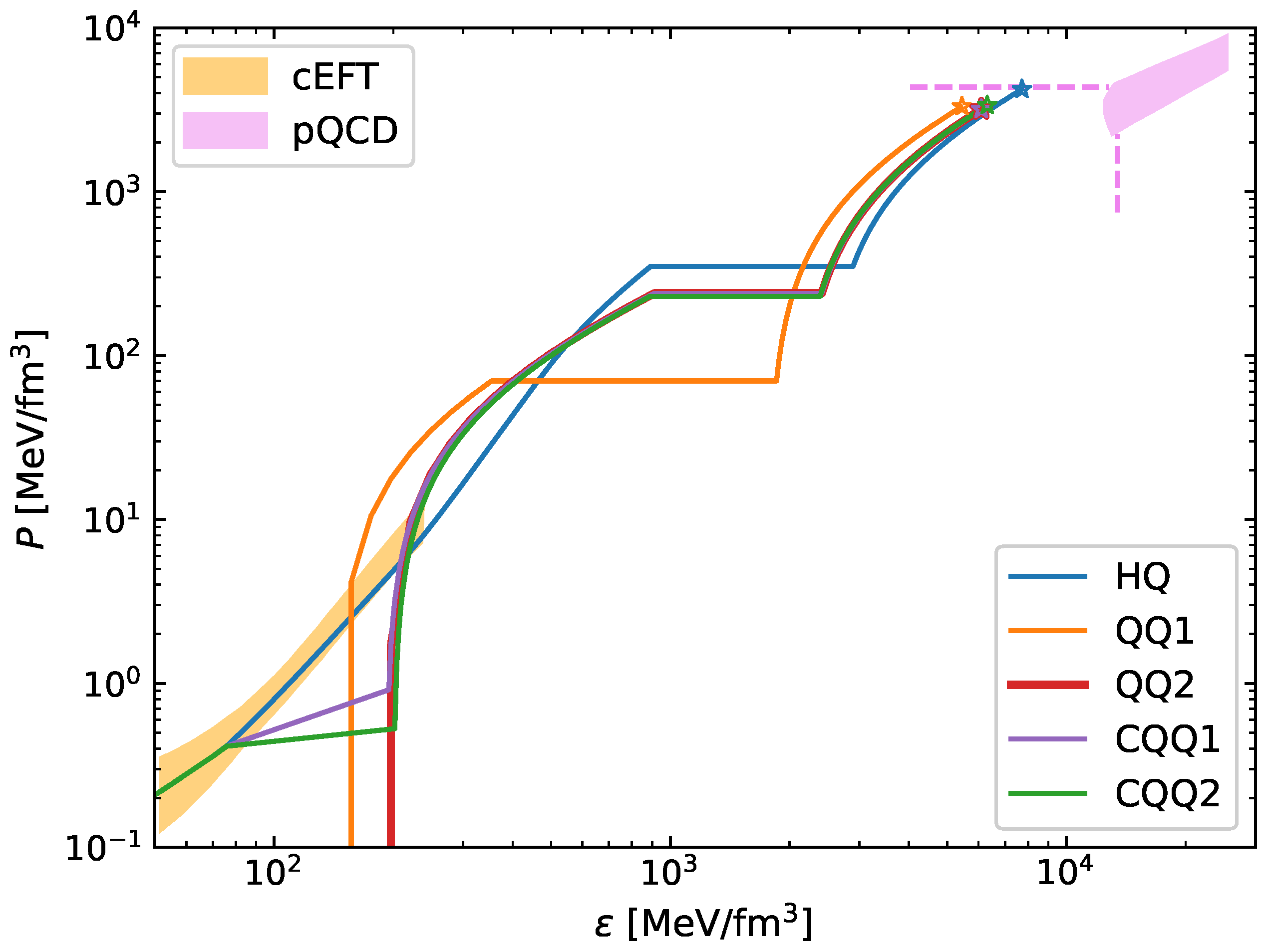

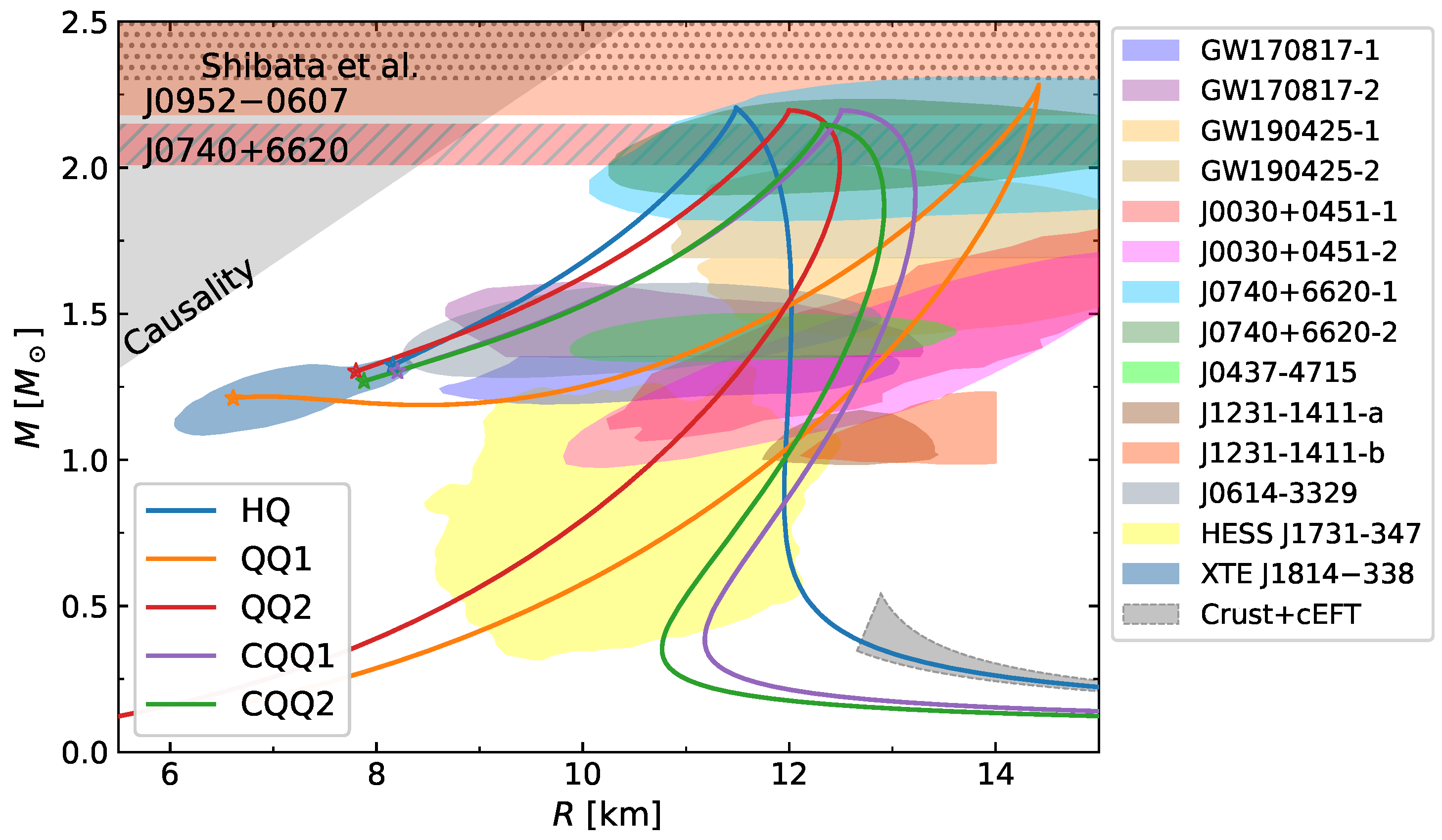

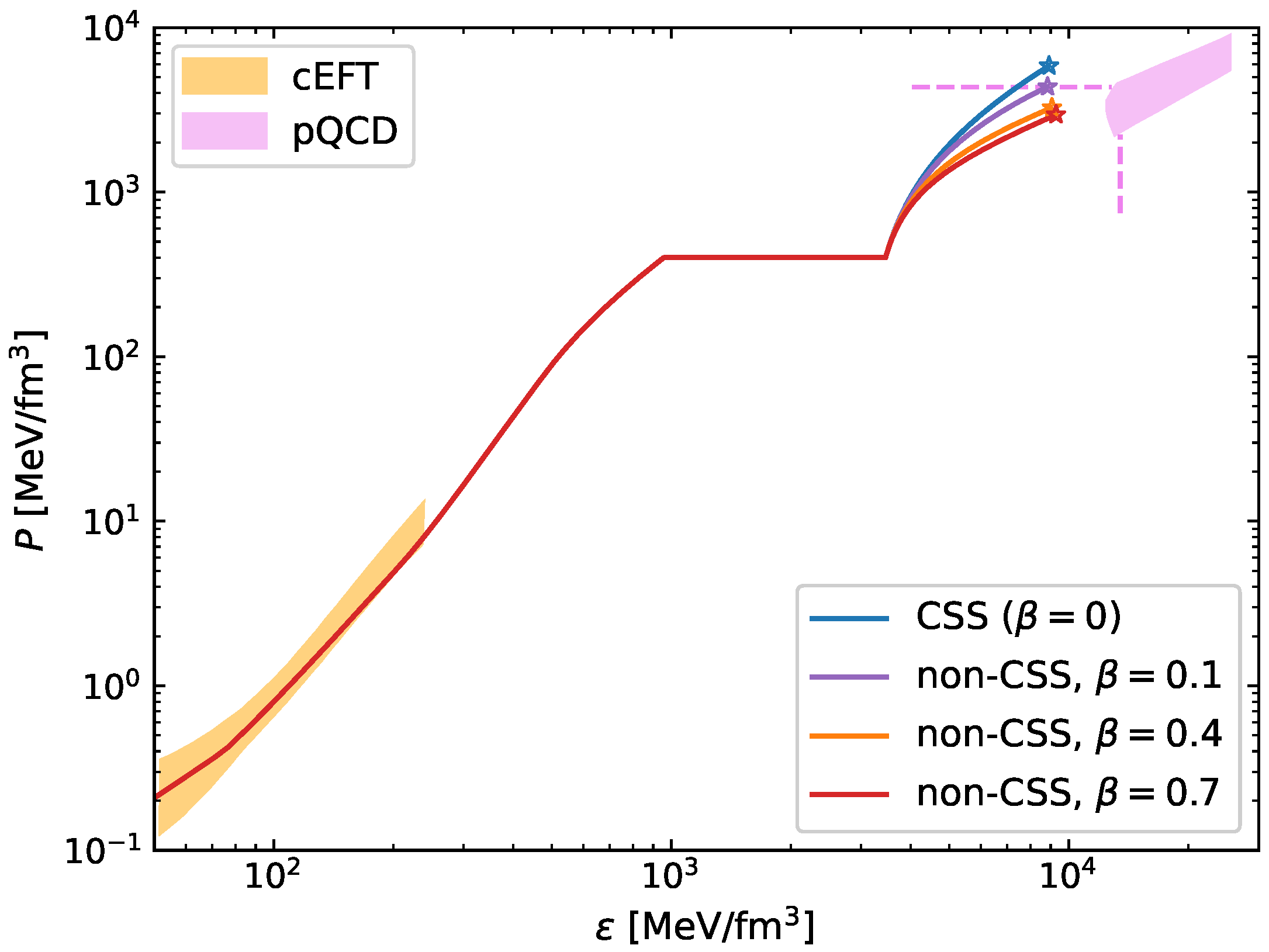

2. Hybrid EOS and HS Models

- HQ-HSs, composed of a BPS-BBP crust, a hadronic GPP outer core detailed in Table 1, and an inner core made of quark matter, modeled through both the CCS and non-CSS parametrizations.

- QQ-HSs without a crust composed of an outer quark core modeled with the MIT bag model and an inner core of quark matter described using the CSS parametrization.

- CQQ-HSs, where the BPS-BBP crust outermost layer is added at to the previous QQ-HSs configuration.

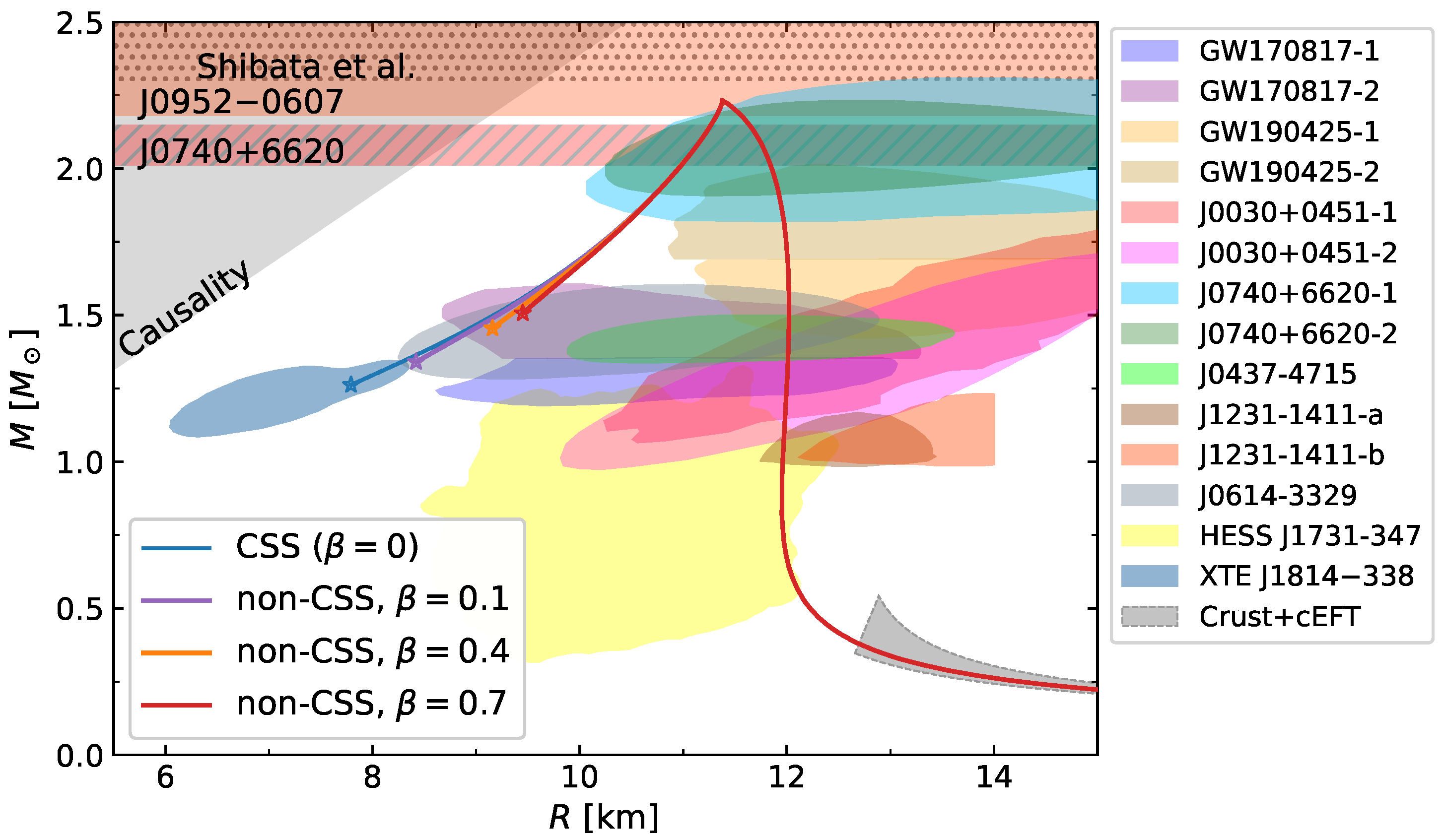

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

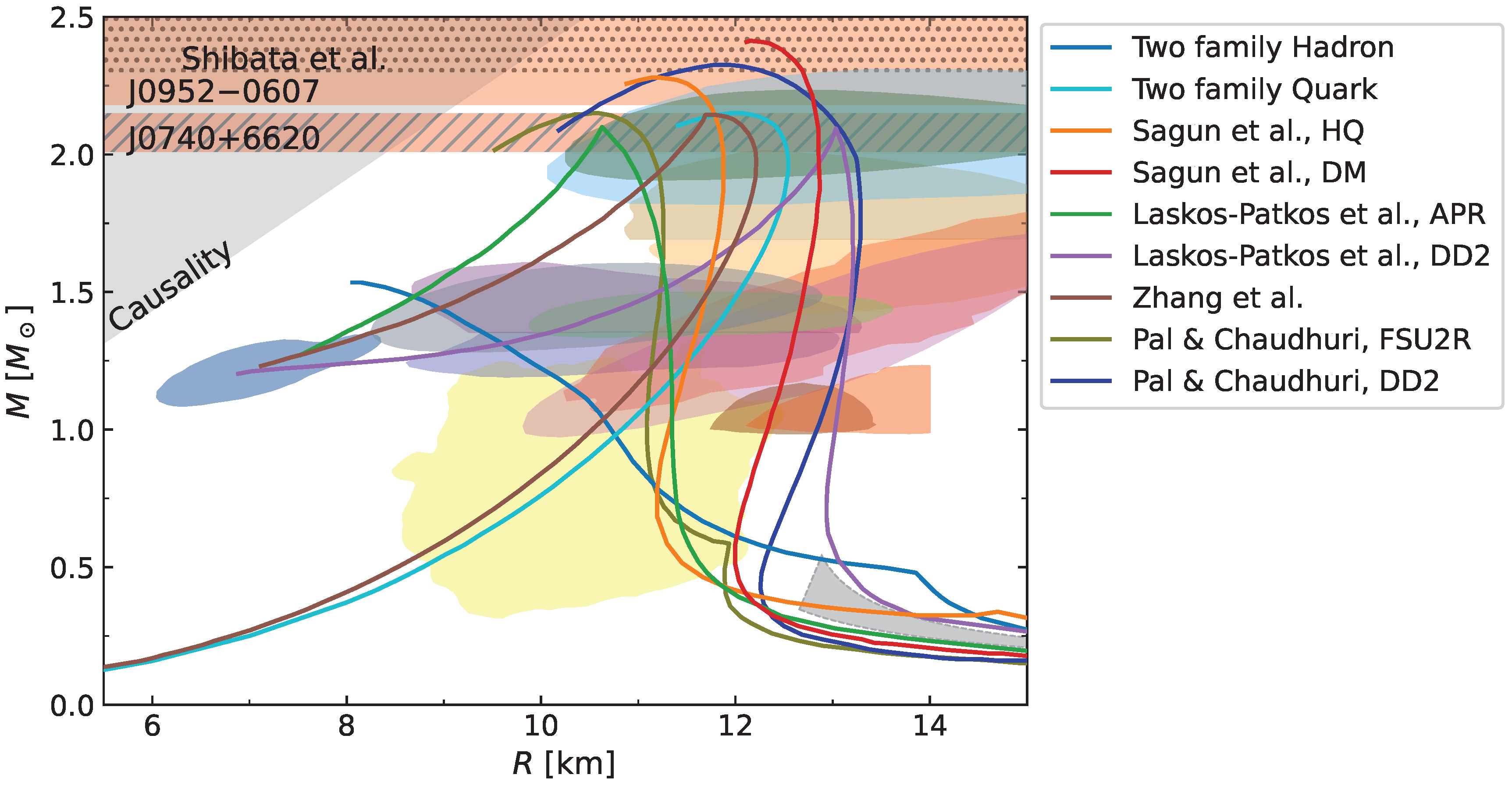

- The modern picture of astronomical constraints related to compact objects produce strong tensions, and models with some type of exotic matter seem to be favored. In particular, if the current estimations of either XTE J1814-338 or PSR J1231-1411 are confirmed (or not strongly rectified) by future analysis, the need to include some type of exotic matter in the inner core of compact stars might be strongly favored.

- In accordance to previous proposals presented by Lugones et al. [57] and Mariani et al. [60] (and also in line with alternative scenarios recently presented in Refs. [61,62]), we show that SSHSs could lead to an appropriate description of modern astronomical observations of compact objects (even considering the extreme ones). Despite this being true, large values of the speed of sound are needed, and potential issues with the conformal limit of pQCD might arise for long SSHSs branches.

- Contrary to the traditional CSS model, the novel non-CSS parametrization proposed in this work is useful for avoiding potential problems with pQCD calculations, but it introduces issues, particularly when explaining the challenging XTE J1814-338 observation.

- The analysis of other recent proposals from the literature -including regular hadronic NSs, the two-family scenario, admixed DM HSs and NSs, and QQ-HSs- shows that, while all leave some room for further refinement or updating, none of them is entirely suitable. Whether considered jointly or separately, XTE J1814-338 and PSR J1231-1411 place stringent constraints on these models.

- Despite these limitations, the other proposed hadronic and hybrid models are in tension with cEFT calculations. If these ideas are used in the future, the low pressure region needs to be adjusted.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demorest, P.; Pennucci, T.; Ransom, S.; Roberts, M.; Hessels, J. Shapiro Delay Measurement of A Two Solar Mass Neutron Star. Nature 2010, 467, 1081–1083, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1010.5788]. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, J.; et al. A Massive Pulsar in a Compact Relativistic Binary. Science 2013, 340, 6131, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1304.6875]. [CrossRef]

- Arzoumanian, Z.; et al. The NANOGrav 11-year Data Set: High-precision Timing of 45 Millisecond Pulsars. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2018, 235, 37. [CrossRef]

- Cromartie, H.T.; et al. Relativistic Shapiro delay measurements of an extremely massive millisecond pulsar. Nature Astronomy 2020, 4, 72–76, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1904.06759]. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.; et al. Refined Mass and Geometric Measurements of the High-mass PSR J0740+6620. ApJL 2021, 915, L12, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2104.00880]. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.C.; et al.. PSR J0030+0451 Mass and Radius from NICER Data and Implications for the Properties of Neutron Star Matter. ApJL 2019, 887, L24. [CrossRef]

- Riley, T.E.; et al.. A NICER View of PSR J0030+0451: Millisecond Pulsar Parameter Estimation. ApJL 2019, 887, L21. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.C.; et al. The Radius of PSR J0740+6620 from NICER and XMM-Newton Data. ApJL 2021, 918, L28, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2105.06979]. [CrossRef]

- Riley, T.E.; et al. A NICER View of the Massive Pulsar PSR J0740+6620 Informed by Radio Timing and XMM-Newton Spectroscopy. ApJL 2021, 918, L27, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2105.06980]. [CrossRef]

- Salmi, T.; Deneva, J.S.; Ray, P.S.; Watts, A.L.; Choudhury, D.; Kini, Y.; Vinciguerra, S.; Cromartie, H.T.; Wolff, M.T.; Arzoumanian, Z.; et al. A NICER View of PSR J1231-1411: A Complex Case. ApJ 2024, 976, 58, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2409.14923]. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Salmi, T.; Vinciguerra, S.; Riley, T.E.; Kini, Y.; Watts, A.L.; Dorsman, B.; Bogdanov, S.; Guillot, S.; Ray, P.S.; et al. A NICER View of the Nearest and Brightest Millisecond Pulsar: PSR J0437–4715. ApJ 2024, 971, L20, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2407.06789]. [CrossRef]

- Mauviard, L.; Guillot, S.; Salmi, T.; Choudhury, D.; Dorsman, B.; González-Caniulef, D.; Hoogkamer, M.; Huppenkothen, D.; Kazantsev, C.; Kini, Y.; et al. A NICER view of the 1.4 solar-mass edge-on pulsar PSR J0614–3329. arXiv e-prints 2025, p. arXiv:2506.14883, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2506.14883]. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 161101. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.; et al. GW170817: Measurements of neutron star radii and equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 161101, [arXiv:gr-qc/1805.11581]. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. GW190425: Observation of a Compact Binary Coalescence with Total Mass ∼ 3.4 M⊙. ApJL 2020, 892, L3, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2001.01761]. [CrossRef]

- Romani, R.W.; Kandel, D.; Filippenko, A.V.; Brink, T.G.; Zheng, W. PSR J0952-0607: The Fastest and Heaviest Known Galactic Neutron Star. ApJ 2022, 934, L17, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2207.05124]. [CrossRef]

- Doroshenko, V.; Suleimanov, V.; Pühlhofer, G.; Santangelo, A. A strangely light neutron star within a supernova remnant. Nature Astronomy 2022, 6, 1444–1451. [CrossRef]

- Kini, Y.; Salmi, T.; Vinciguerra, S.; Watts, A.L.; Bilous, A.; Galloway, D.K.; van der Wateren, E.; Khalsa, G.P.; Bogdanov, S.; Buchner, J.; et al. Constraining the properties of the thermonuclear burst oscillation source XTE J1814-338 through pulse profile modelling. MNRAS 2024, 535, 1507–1525, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2405.10717]. [CrossRef]

- Drischler, C.; Han, S.; Lattimer, J.M.; Prakash, M.; Reddy, S.; Zhao, T. Limiting masses and radii of neutron stars and their implications. Phys. Rev. C 2021, 103, 045808. [CrossRef]

- Annala, E.; Gorda, T.; Kurkela, A.; Nättilä, J.; Vuorinen, A. Evidence for quark-matter cores in massive neutron stars. Nature Physics 2020, 16, 907–910, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1903.09121]. [CrossRef]

- Alford, J.; Halpern, J. Do central compact objects have carbon atmospheres? The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 944, 36.

- Malik, T.; Cartaxo, J.; Providência, C. Observational constraints on neutron star matter equation of state. J. Subatomic Part. Cosmol. 2025, 4, 100086. [CrossRef]

- Punturo, M.; Abernathy, M.; Acernese, F.; Allen, B.; Andersson, N.; Arun, K.; Barone, F.; Barr, B.; Barsuglia, M.; Beker, M.; et al. The Einstein Telescope: a third-generation gravitational wave observatory. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2010, 27, 194002. [CrossRef]

- Reitze, D.; Adhikari, R.X.; Ballmer, S.; Barish, B.; Barsotti, L.; Billingsley, G.; Brown, D.A.; Chen, Y.; Coyne, D.; Eisenstein, R.; et al. Cosmic Explorer: The U.S. Contribution to Gravitational-Wave Astronomy beyond LIGO. In Proceedings of the Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, September 2019, Vol. 51, p. 35, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1907.04833]. [CrossRef]

- Lück, H.; Smith, J.; Punturo, M., Third-Generation Gravitational-Wave Observatories. In Handbook of Gravitational Wave Astronomy; Bambi, C.; Katsanevas, S.; Kokkotas, K.D., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Baym, Gordon and Hatsuda, Tetsuo and Kojo, Toru and Powell, Philip D. and Song, Yifan and Takatsuka, Tatsuyuki. From hadrons to quarks in neutron stars: a review. Rept. Prog. Phys. 2018, 81, 056902, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1707.04966]. [CrossRef]

- Orsaria, M.G.; Malfatti, G.; Mariani, M.; Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; García, F.; Spinella, W.M.; Contrera, G.A.; Lugones, G.; Weber, F. Phase transitions in neutron stars and their links to gravitational waves. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 2019, 46, 073002.

- Dexheimer, V.A.; Schramm, S. A novel approach to modeling hybrid stars. Phys. Rev. C 2010, 81, 045201, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/0901.1748]. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Wang, Y.; Camacho, N.C.; Kumar, A.; Noronha-Hostler, J.; Dexheimer, V. Modern nuclear and astrophysical constraints of dense matter in a redefined chiral approach. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 074008, [arXiv:nucl-th/2401.12944]. [CrossRef]

- Celi, M.O.; Mariani, M.; Kumar, R.; Bashkanov, M.; Orsaria, M.G.; Pastore, A.; Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Dexheimer, V. Exploring the role of d* hexaquarks on quark deconfinement and hybrid stars. Physical Review D 2025, 112, 023027.

- Logoteta, D.; Bombaci, I.; Perego, A. Isoentropic equations of state of β-stable hadronic matter with a quark phase transition. European Physical Journal A 2022, 58, 55. [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.; Zhao, T.; Han, S.; Prakash, M. Framework for phase transitions between the Maxwell and Gibbs constructions. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 074013. [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Hu, J.; Shen, H. Hadron-quark pasta phase in massive neutron stars. The Astrophysical Journal 2021, 923, 250.

- Mariani, M.; Lugones, G. Quark-hadron pasta phase in neutron stars: The role of medium-dependent surface and curvature tensions. Physical Review D 2024, 109, 063022.

- Pinto, M.B.; Koch, V.; Randrup, J. Surface tension of quark matter in a geometrical approach. Physical Review C—Nuclear Physics 2012, 86, 025203.

- Mintz, B.W.; Stiele, R.; Ramos, R.O.; Schaffner-Bielich, J. Phase diagram and surface tension in the three-flavor Polyakov-quark-meson model. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2013, 87, 036004.

- Pereira, J.P.; Flores, C.V.; Lugones, G. Phase transition effects on the dynamical stability of hybrid neutron stars. Astrophys. J. 2018, 860, 12, [arXiv:gr-qc/1706.09371]. [CrossRef]

- Arbanil, J.D.; Malheiro, M. Equilibrium and stability of charged strange quark stars. Physical Review D 2015, 92, 084009.

- Mohanty, S.R.; Ghosh, S.; Kumar, B. Unstable anisotropic neutron stars: Probing the limits of gravitational collapse. Physical Review D 2024, 109, 123039.

- Kain, B. Radial oscillations and stability of multiple-fluid compact stars. Physical Review D 2020, 102, 023001.

- Caballero, D.A.; Ripley, J.; Yunes, N. Radial mode stability of two-fluid neutron stars. Physical Review D 2024, 110, 103038.

- Pereira, J.P.; Bejger, M.; Tonetto, L.; Lugones, G.; Haensel, P.; Zdunik, J.L.; Sieniawska, M. Probing elastic quark phases in hybrid stars with radius measurements. The Astrophysical Journal 2021, 910, 145.

- Canullan-Pascual, M.O.; Lugones, G.; Orsaria, M.G.; Ranea-Sandoval, I.F. Neutron star stability beyond the mass peak: assessing the role of out-of-equilibrium perturbations. The Astrophysical Journal 2025, 989, 135.

- Drago, A.; Lavagno, A.; Pagliara, G. Can very compact and very massive neutron stars both exist? Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 043014. [CrossRef]

- Di Clemente, F.; Drago, A.; Pagliara, G. Is the Compact Object Associated with HESS J1731-347 a Strange Quark Star? A Possible Astrophysical Scenario for Its Formation. ApJ 2024, 967, 159, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2211.07485]. [CrossRef]

- Drago, A.; Lavagno, A.; Pagliara, G.; Pigato, D. The scenario of two families of compact stars. Part 1. Equations of state, mass-radius relations and binary systems. European Physical Journal A 2016, 52, 40. [CrossRef]

- Drago, A.; Pagliara, G. The scenario of two families of compact stars: part 2: transition from hadronic to quark matter and explosive phenomena. The European Physical Journal A 2016, 52, 41.

- Abgaryan, V.; Alvarez-Castillo, D.; Ayriyan, A.; Blaschke, D.; Grigorian, H. Two novel approaches to the Hadron-Quark mixed phase in compact stars. Universe 2018, 4, 94.

- Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Orsaria, M.G.; Malfatti, G.; Curin, D.; Mariani, M.; Contrera, G.A.; Guilera, O.M. Effects of hadron-quark phase transitions in hybrid stars within the NJL model. Symmetry 2019, 11, 425.

- Carlomagno, J.P.; Contrera, G.A.; Grunfeld, A.G.; Blaschke, D. Thermal twin stars within a hybrid equation of state based on a nonlocal chiral quark model compatible with modern astrophysical observations. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 043050. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Castillo, D.; Blaschke, D.; Grunfeld, A.G.; Pagura, V. Third family of compact stars within a nonlocal chiral quark model equation of state. Physical Review D 2019, 99, 063010.

- Pal, S.; Chaudhuri, G. Can a Hybrid Star with Constant Sound Speed Parameterization Explain the New NICER Mass–Radius Measurements? The Astrophysical Journal 2025, 991, 158. [CrossRef]

- Alford, M.; Sedrakian, A. Compact Stars with Sequential QCD Phase Transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 161104. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.C.; Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Mariani, M.; Orsaria, M.G.; Malfatti, G.; Guilera, O.M. Hybrid stars with sequential phase transitions: the emergence of the g2 mode. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2021, 2021, 009.

- Li, J.J.; Sedrakian, A.; Alford, M. Relativistic hybrid stars with sequential first-order phase transitions in light of multimessenger constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 944, 206.

- Gonçalves, V.P.; Lazzari, L. Impact of slow conversions on hybrid stars with sequential QCD phase transitions. The European Physical Journal C 2022, 82, 288.

- Lugones, G.; Mariani, M.; Ranea-Sandoval, I.F. A model-agnostic analysis of hybrid stars with reactive interfaces. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2023, 2023, 028.

- Rau, P.B.; Salaben, G.G. Nonequilibrium effects on stability of hybrid stars with first-order phase transitions. 2023, 108, 103035, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2309.08540]. [CrossRef]

- Rau, P.B.; Sedrakian, A. Two first-order phase transitions in hybrid compact stars: Higher-order multiplet stars, reaction modes, and intermediate conversion speeds. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 103042.

- Mariani, M.; Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Lugones, G.; Orsaria, M.G. Could a slow stable hybrid star explain the central compact object in HESS J1731-347? Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 043026. [CrossRef]

- Laskos-Patkos, P.; Moustakidis, C.C. XTE J1814-338: A potential hybrid star candidate. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 063058. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pretel, J.M.Z.; Xu, R. Slow Stable Self-bound Hybrid Star Can Relieve All Tensions. arXiv e-prints 2025, p. arXiv:2507.01371, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2507.01371]. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zeng, T.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, W.L.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, E. Hybrid Quark Stars with Quark-Quark Phase Transitions. arXiv e-prints 2025, p. arXiv:2507.00776, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2507.00776]. [CrossRef]

- Sagun, V.; Giangrandi, E.; Dietrich, T.; Ivanytskyi, O.; Negreiros, R.; Providência, C. What Is the Nature of the HESS J1731-347 Compact Object? ApJ 2023, 958, 49, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2306.12326]. [CrossRef]

- Alford, M.; Bowers, J.A.; Rajagopal, K. Crystalline color superconductivity. Physical Review D 2001, 63, 074016.

- Alford, M. Color-superconducting quark matter. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 2001, 51, 131–160.

- Ruester, S.B.; Werth, V.; Buballa, M.; Shovkovy, I.A.; Rischke, D.H. Phase diagram of neutral quark matter: Self-consistent treatment of quark masses. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2005, 72, 034004.

- Miralda-Escude, J.; Haensel, P.; Paczynski, B. Thermal Structure of Accreting Neutron Stars and Strange Stars. ApJ 1990, 362, 572. [CrossRef]

- Glendenning, N.K.; Weber, F. Nuclear Solid Crust on Rotating Strange Quark Stars. ApJ 1992, 400, 647. [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, M.F.; Markakis, C.; Stergioulas, N.; Read, J.S. Parametrized equation of state for neutron star matter with continuous sound speed. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 083027, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2008.03342]. [CrossRef]

- Baym, G.; Pethick, C.; Sutherland, P. The Ground State of Matter at High Densities: Equation of State and Stellar Models. ApJ 1971, 170, 299. [CrossRef]

- Baym, G.; Bethe, H.A.; Pethick, C.J. Neutron star matter. Nuclear Physics A 1971, 175, 225–271. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; et al. The MIT bag model. Acta Phys. Pol. B 1975, 6, 8.

- Alford, M.G.; Han, S.; Prakash, M. Generic conditions for stable hybrid stars. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2013, 88, 083013.

- Shibata, M.; Zhou, E.; Kiuchi, K.; Fujibayashi, S. Constraint on the maximum mass of neutron stars using GW170817 event. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 023015, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1905.03656]. [CrossRef]

- Shirke, S.; Maiti, R.; Chatterjee, D. PSR J0614-3329: A NICER case for Strange Quark Stars. arXiv e-prints 2025, p. arXiv:2508.02652, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2508.02652]. [CrossRef]

- Tonetto, L.; Lugones, G. Discontinuity gravity modes in hybrid stars: Assessing the role of rapid and slow phase conversions. Physical Review D 2020, 101, 123029.

- Sotani, H.; Tominaga, K.; Maeda, K.i. Density discontinuity of a neutron star and gravitational waves. Physical Review D 2001, 65, 024010.

- Miniutti, G.; Pons, J.; Berti, E.; Gualtieri, L.; Ferrari, V. Non-radial oscillation modes as a probe of density discontinuities in neutron stars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2003, 338, 389–400.

- Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Guilera, O.M.; Mariani, M.; Orsaria, M.G. Oscillation modes of hybrid stars within the relativistic Cowling approximation. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2018, 2018, 031.

- Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Guilera, O.M.; Mariani, M.; Lugones, G. Breaking of universal relationships of axial w I modes in hybrid stars: Rapid and slow hadron-quark conversion scenarios. Physical Review D 2022, 106, 043025.

- Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Mariani, M.; Celi, M.O.; Rodríguez, M.C.; Tonetto, L. Asteroseismology using quadrupolar f-modes revisited: Breaking of universal relationships in the slow hadron-quark conversion scenario. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 123028.

- Ranea-Sandoval, I.F.; Mariani, M.; Lugones, G.; Guilera, O.M. Constraining mass, radius, and tidal deformability of compact stars with axial wI modes: new universal relations including slow stable hybrid stars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2023, 519, 3194–3200.

- Li, A.; Watts, A.L.; Zhang, G.; Guillot, S.; Xu, Y.; Santangelo, A.; Zane, S.; Feng, H.; Zhang, S.N.; Ge, M.; et al. Dense matter in neutron stars with eXTP. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 2025, 68, 119503.

- Majczyna, A.; Madej, J.; Należyty, M.; Różańska, A.; Bełdycki, B. Precision of Mass and Radius Determination for Neutron Stars from the ATHENA Mission. ApJ 2020, 888, 123. [CrossRef]

| 1 | It is important to stress that stability in these extended branches also appears in different astronomical scenarios: electrically charged quark stars [38]; anisotropic compact stars [39]; multiple-fluid compact objects [40,41]; HSs with elastic phases in their cores [42] and hadronic NSs when perturbations are not assumed to preserve chemical equilibrium but frozen populations of particles are considered for the perturbation [43]. |

| Hadronic EOS | 14.127 | 14.55 | 14.90 | -27.22 | 2.761 | 3.80 | 2.40 |

| EOS | Hadron sector | Bag [MeV/fm3] | [MeV/fm3] | [MeV/fm3] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HQ | ✓ | - | 350 | 2000 | 0.8 |

| QQ1 | ✗ | 36 | 70 | 1500 | 0.9 |

| QQ2 | ✗ | 48 | 240 | 1500 | 0.8 |

| CQQ1 | ✗ | 48 | 240 | 1500 | 0.8 |

| CQQ2 | ✗ | 50 | 230 | 1500 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).