Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Single-Cell RNA-seq Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

2.2. Mice

2.3. Cockroach Allergen-Induced Asthma Mouse Model

2.4. Analysis of Lung Inflammation

2.5. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.6. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.7. ROS Measurement

2.8. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Staining

2.9. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.10. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.11. RNA-seq Analysis

2.12. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.13. In Silico Prediction of AhR–c-Myc Binding Using AlphaFold 3

2.14. Chromatin Immunocoprecipitation

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

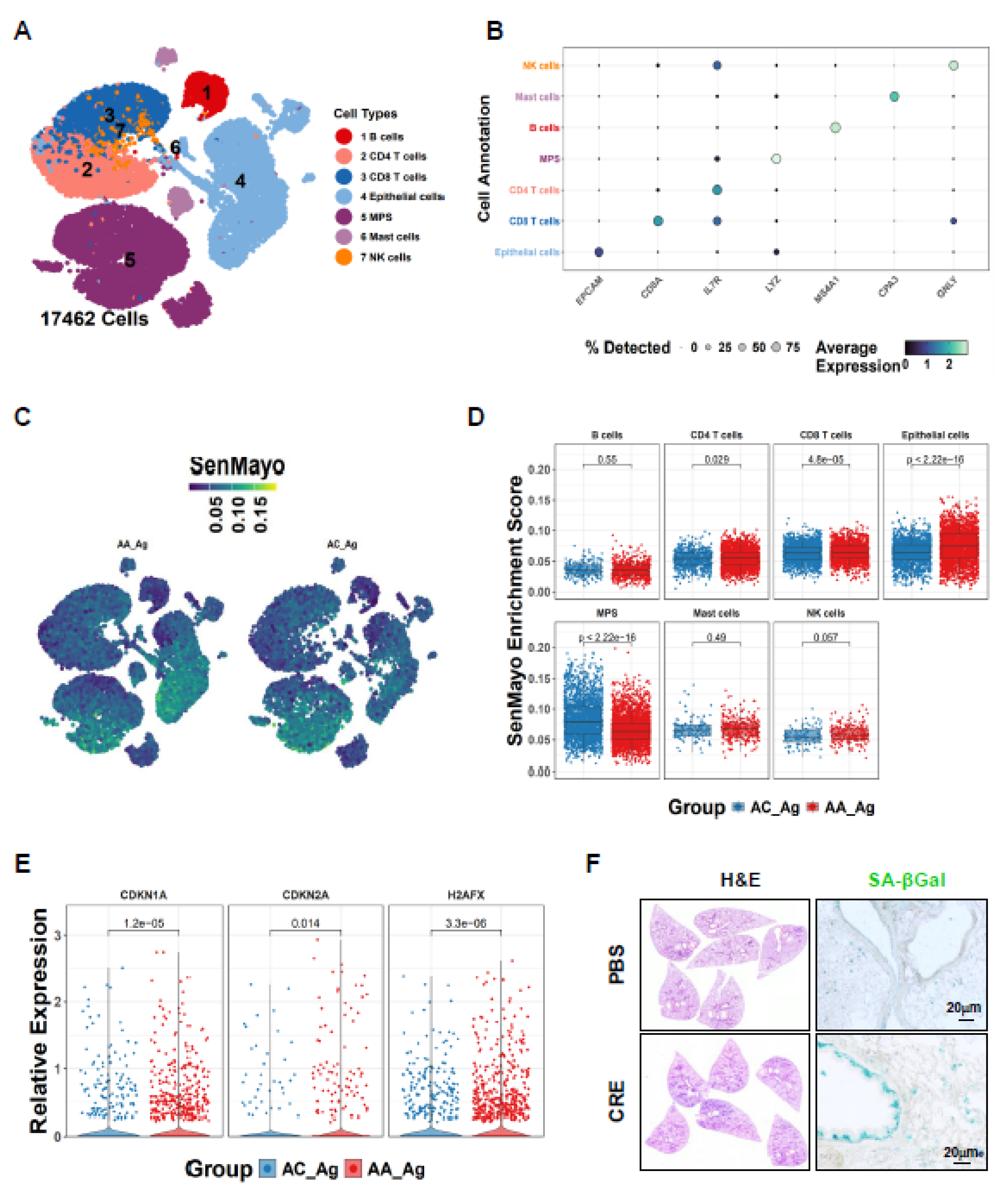

3.1. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Reveal Epithelial Senescence as a Key Feature of Allergen-Induced Asthma

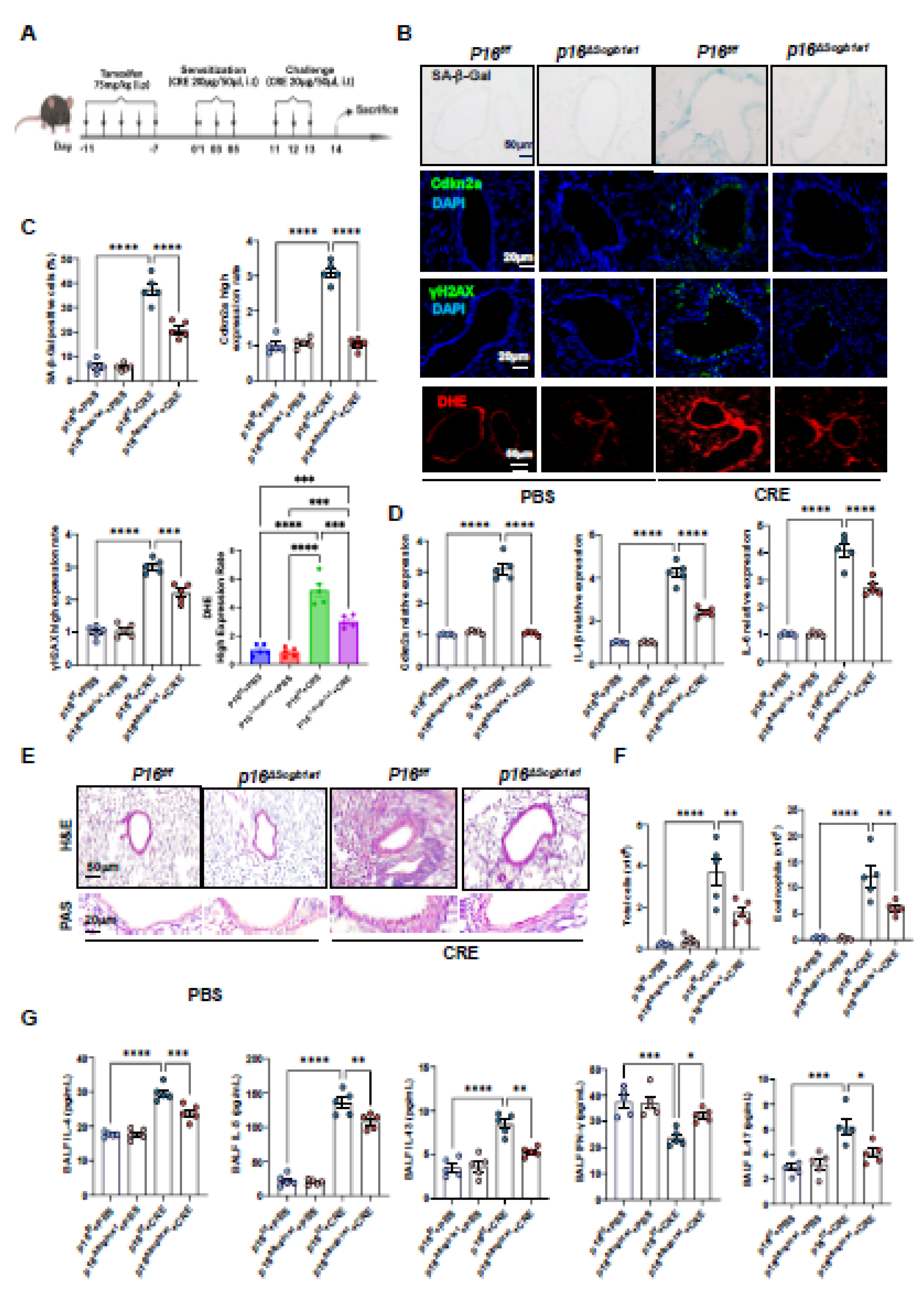

3.2. Deletion of Senescent Club Cells Attenuates Allergen-Induced ROS and Airway Inflammation

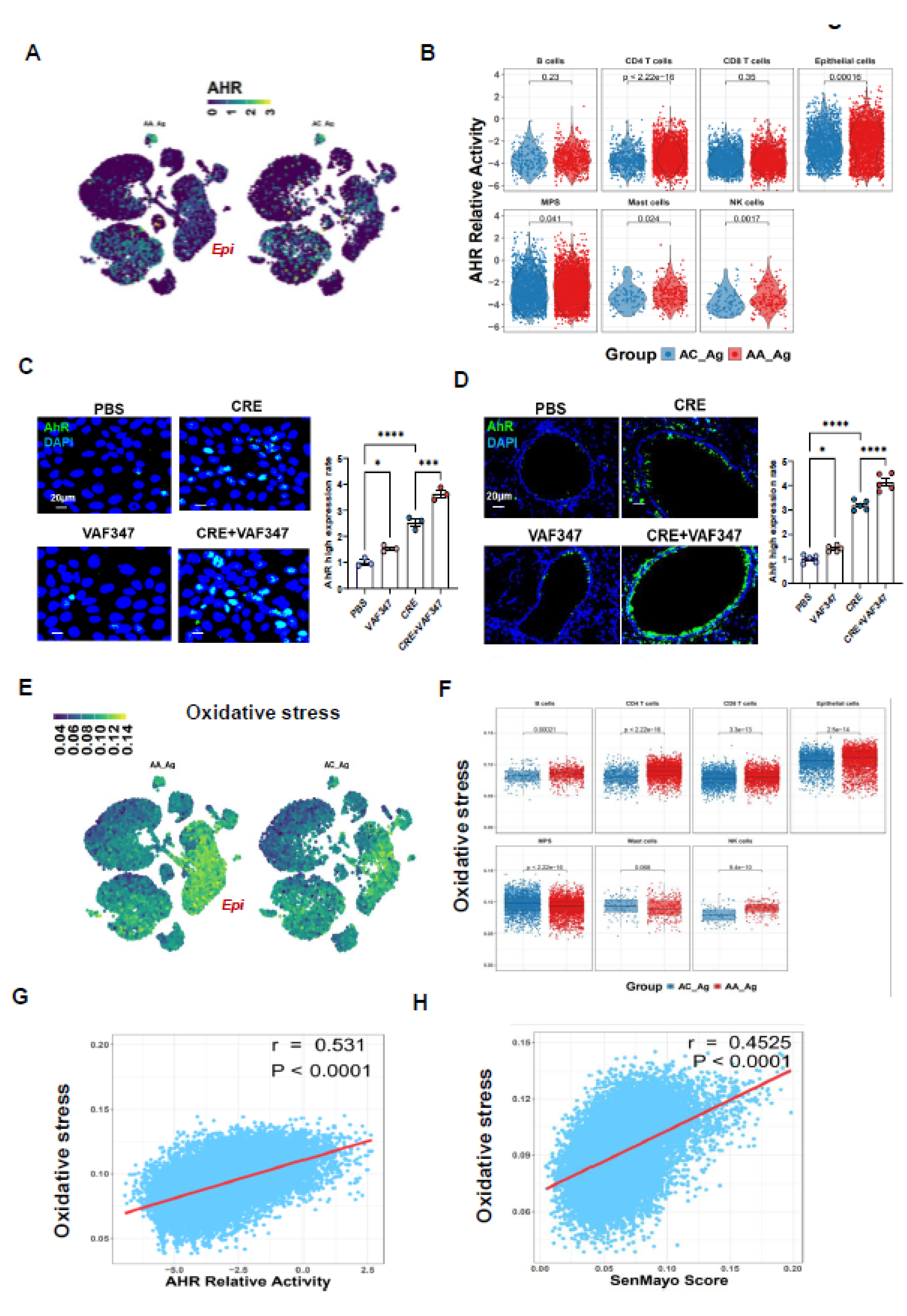

3.3. Allergen-Induced Upregulation of AhR Correlates with ROS Generation and Epithelial Senescence

3.4. Enhanced AhR Signaling Protects Against Allergen-Induced Senescence in HBECs

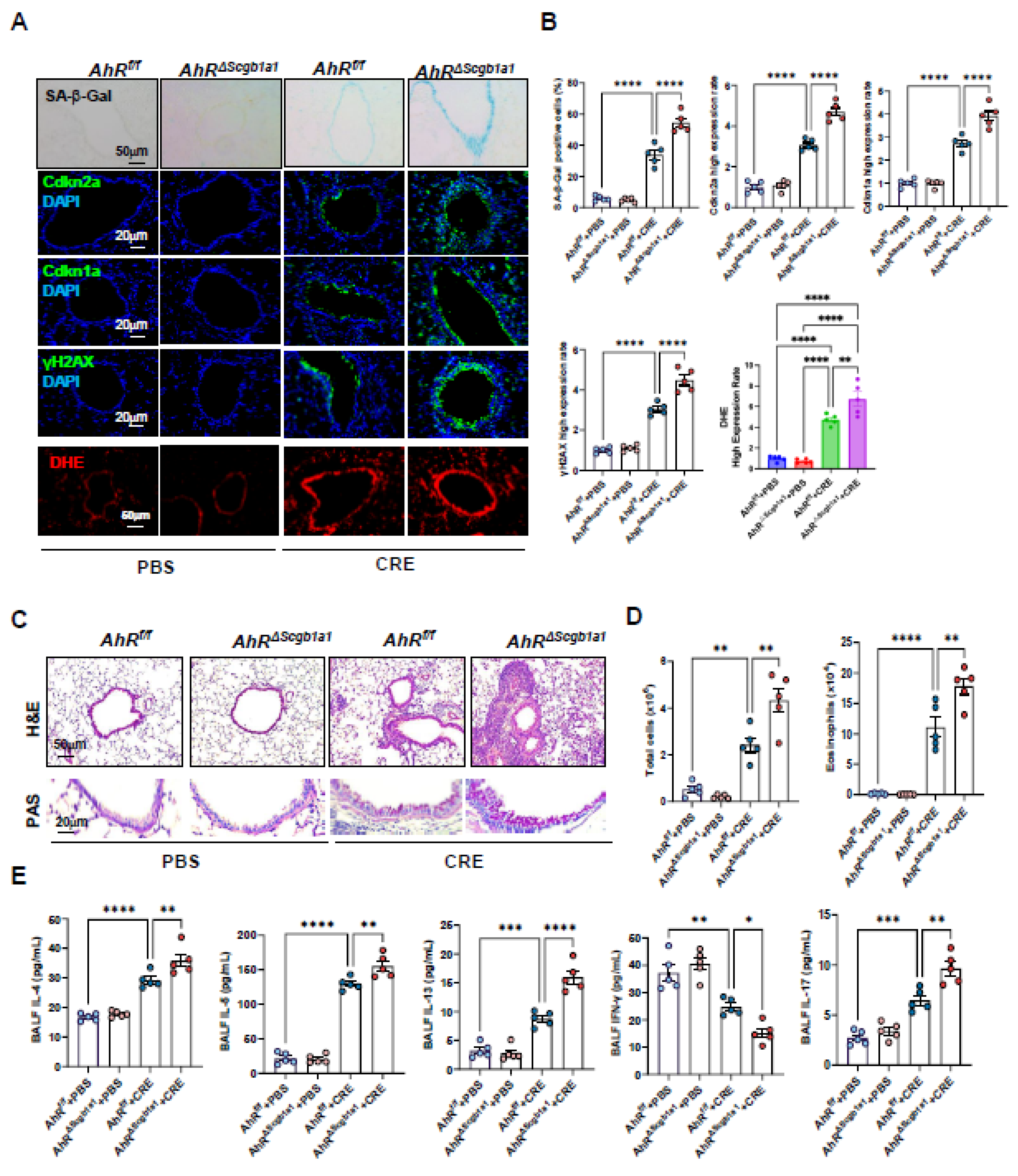

3.5. Club cell–Specific Deletion of AhR Exacerbates Cockroach Allergen–Induced Epithelial Senescence and Airway Inflammation

3.6. AhR Activation Suppresses Cockroach Allergen–Induced Senescence and Airway Inflammation

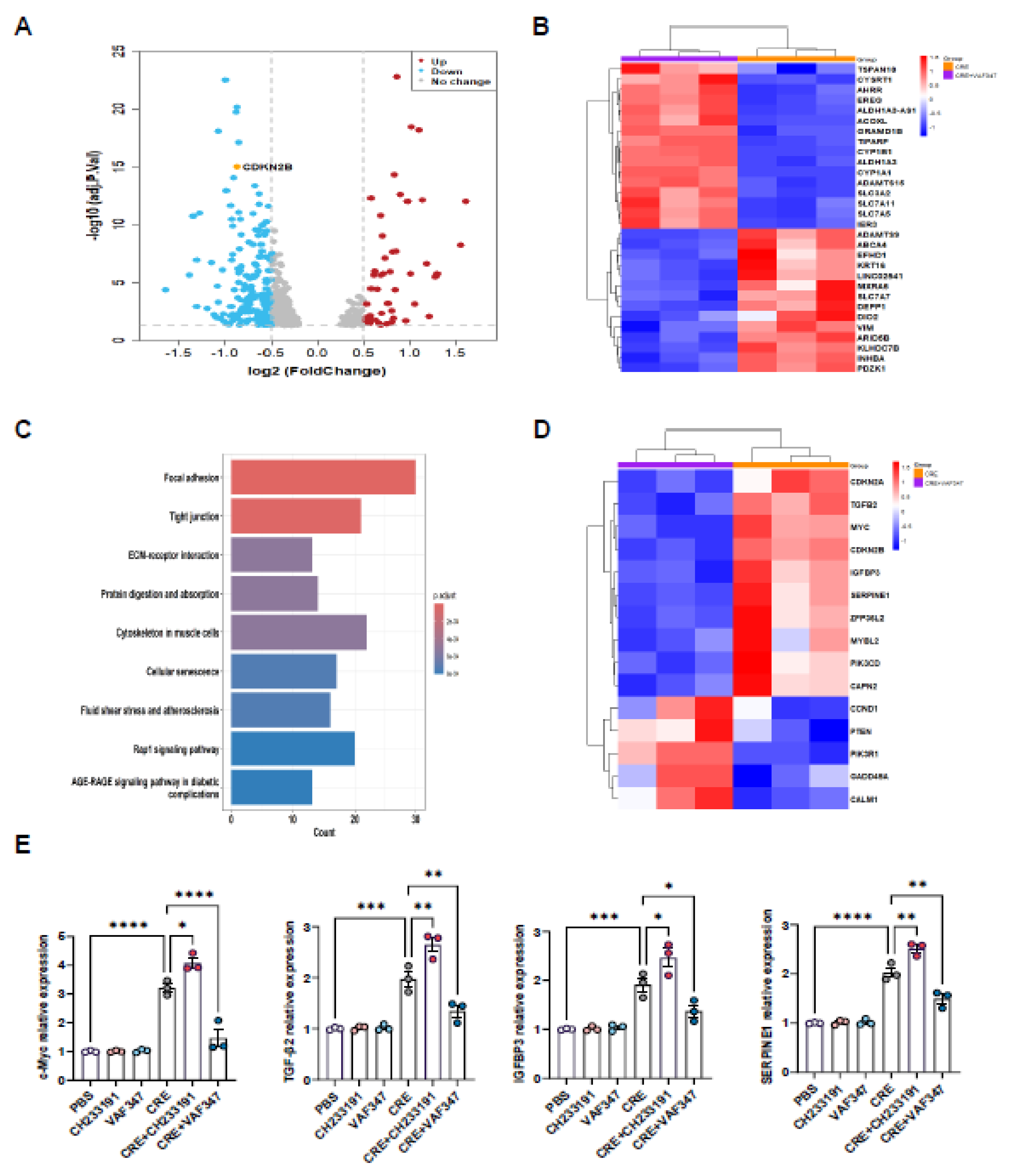

3.7. Transcriptomic Profiling Identifies AhR-Regulated Gene Expression in HBECs

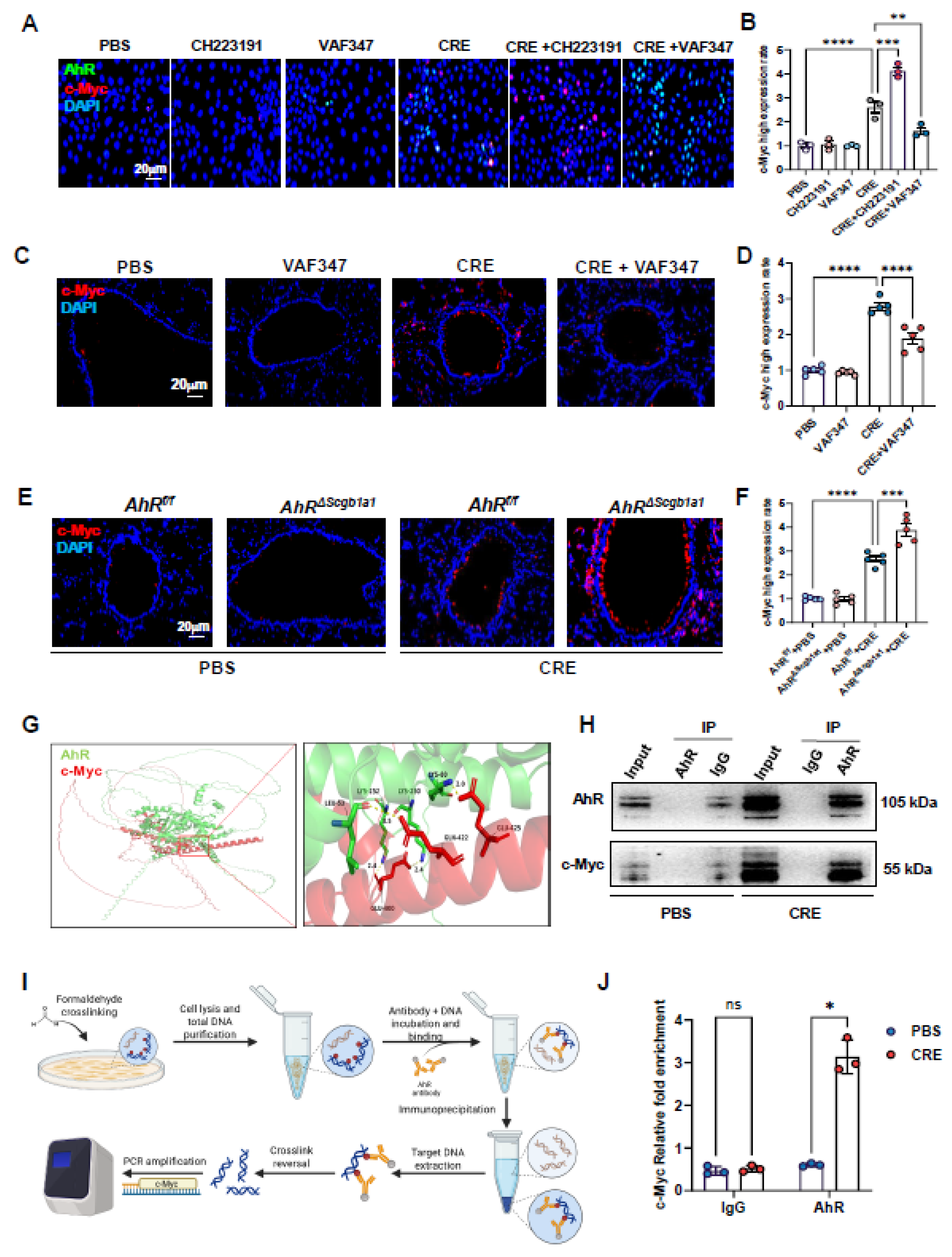

3.8. AhR Regulates c-Myc Expression Via Direct Promoter Binding

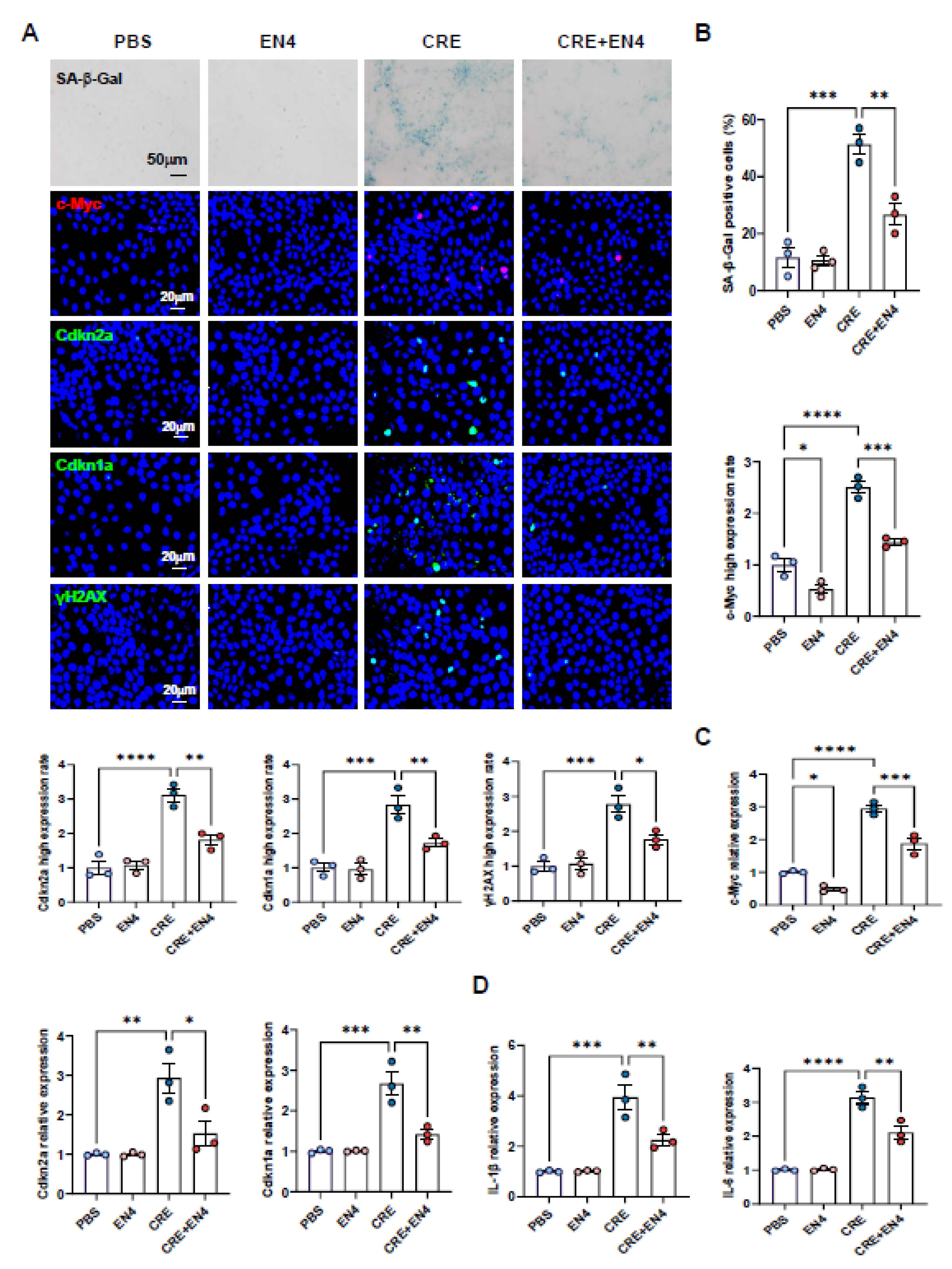

3.9. Inhibition of c-Myc Suppresses Allergen-Induced Senescence and SASP Expression in HBECs

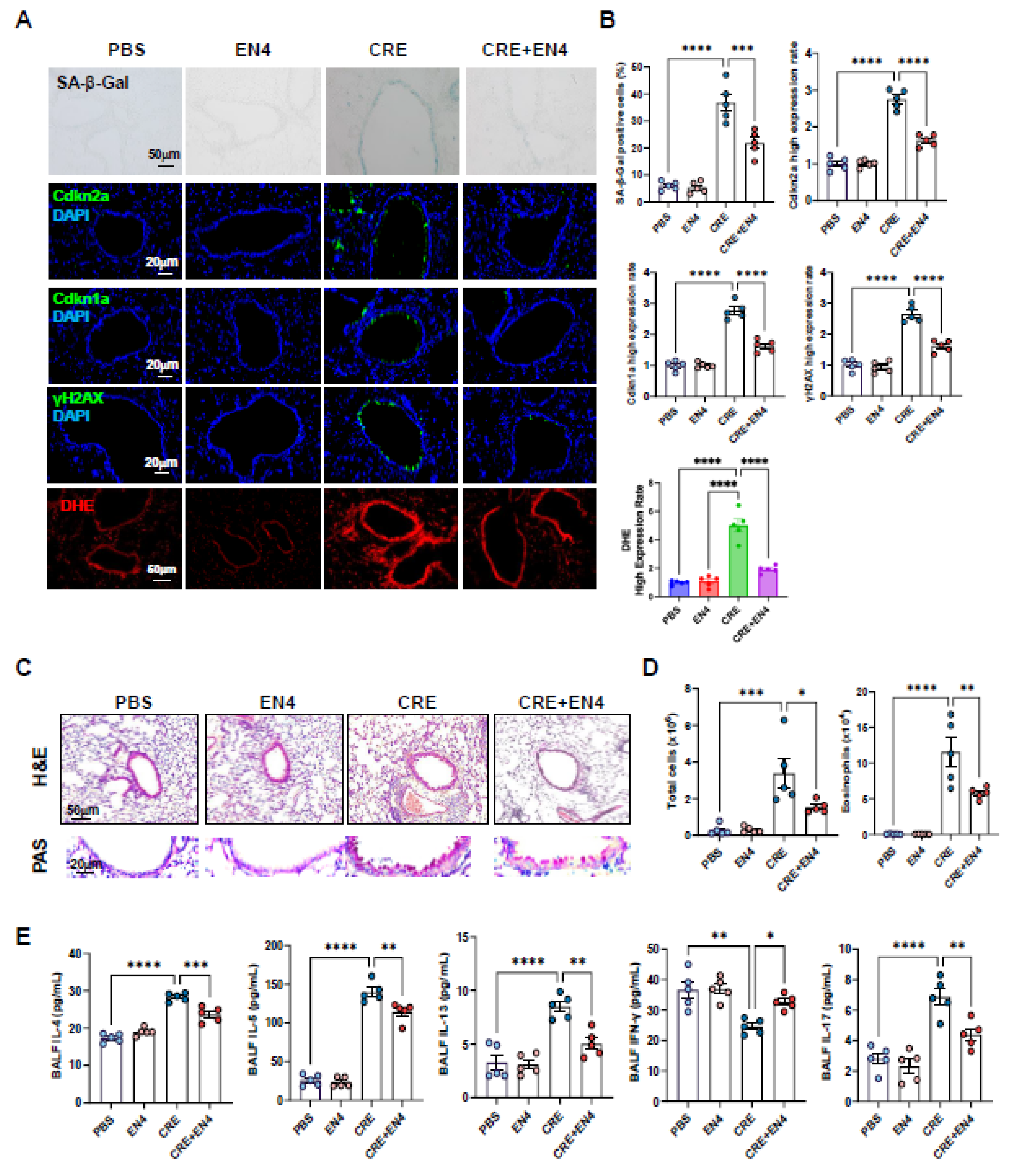

3.10. Inhibiting c-Myc Attenuates Allergen-Induced ROS, Cellular Senescence, and Allergic Airway Inflammation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRE | Cockroach extract |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA-seq |

| HBEC | Human bronchial epithelial cell |

| DEG | Differentially expressed genes |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| KEGG | Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes |

| Cdkn2a | Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| Cdkn1a | Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| IP | Immunoprecipitation |

| ChIP | Chromatin immunoprecipitation |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction |

| SA-β-Gal | Senescence β-Galactosidase |

| OCT | Optimal cutting temperature |

| DAPI | 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| ANOVA | An ordinary one-way analysis of variance |

References

- Pate, C. A., H. S. Zahran, X. Qin, C. Johnson, E. Hummelman, and J. Malilay. "Asthma Surveillance - United States, 2006-2018." MMWR Surveill Summ 70, no. 5 (2021): 1-32.

- Dunn, R. M., P. J. Busse, and M. E. Wechsler. "Asthma in the Elderly and Late-Onset Adult Asthma." Allergy 73, no. 2 (2018): 284-94. [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A., A. P. Baptist, R. Divekar, N. Parikh, J. S. Seggev, J. S. Yusin, and S. M. Nyenhuis. "Asthma in the Older Adult." J Asthma 57, no. 3 (2020): 241-52. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. E., Y. N. Wang, M. R. Hua, H. Miao, Y. Y. Zhao, and G. Cao. "Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Targets in Aging-Related Tissue Fibrosis." Ageing Res Rev 79 (2022): 101662. [CrossRef]

- Soma, T., and M. Nagata. "Immunosenescence, Inflammaging, and Lung Senescence in Asthma in the Elderly." Biomolecules 12, no. 10 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M. J., T. A. White, K. Iijima, A. J. Haak, G. Ligresti, E. J. Atkinson, A. L. Oberg, J. Birch, H. Salmonowicz, Y. Zhu, D. L. Mazula, R. W. Brooks, H. Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, T. Pirtskhalava, Y. S. Prakash, T. Tchkonia, P. D. Robbins, M. C. Aubry, J. F. Passos, J. L. Kirkland, D. J. Tschumperlin, H. Kita, and N. K. LeBrasseur. "Cellular Senescence Mediates Fibrotic Pulmonary Disease." Nat Commun 8 (2017): 14532. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. N., R. N. Su, B. Y. Yang, K. X. Yang, L. F. Yang, Y. Yan, and Z. G. Chen. "Potential Role of Cellular Senescence in Asthma." Front Cell Dev Biol 8 (2020): 59. [CrossRef]

- Wan, R., P. Srikaram, V. Guntupalli, C. Hu, Q. Chen, and P. Gao. "Cellular Senescence in Asthma: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Challenges." EBioMedicine 94 (2023): 104717. [CrossRef]

- Aghali, A., L. Khalfaoui, A. B. Lagnado, L. Y. Drake, J. J. Teske, C. M. Pabelick, J. F. Passos, and Y. S. Prakash. "Cellular Senescence Is Increased in Airway Smooth Muscle Cells of Elderly Persons with Asthma." Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 323, no. 5 (2022): L558-L68. [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, R., V. Krizhanovsky, D. Baker, and F. d'Adda di Fagagna. "Cellular Senescence in Ageing: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities." Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 22, no. 2 (2021): 75-95.

- Santoro, A., E. Bientinesi, and D. Monti. "Immunosenescence and Inflammaging in the Aging Process: Age-Related Diseases or Longevity?" Ageing Res Rev 71 (2021): 101422. [CrossRef]

- Shvedova, M., R. J. R. Samdavid Thanapaul, E. L. Thompson, L. J. Niedernhofer, and D. S. Roh. "Cellular Senescence in Aging, Tissue Repair, and Regeneration." Plast Reconstr Surg 150 (2022): 4s-11s. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Espín, D., M. Cañamero, A. Maraver, G. Gómez-López, J. Contreras, S. Murillo-Cuesta, A. Rodríguez-Baeza, I. Varela-Nieto, J. Ruberte, M. Collado, and M. Serrano. "Programmed Cell Senescence During Mammalian Embryonic Development." Cell 155, no. 5 (2013): 1104-18. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., M. Qu, J. Li, P. Danielson, L. Yang, and Q. Zhou. "Induction of Fibroblast Senescence During Mouse Corneal Wound Healing." Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 60, no. 10 (2019): 3669-79. [CrossRef]

- Calcinotto, A., J. Kohli, E. Zagato, L. Pellegrini, M. Demaria, and A. Alimonti. "Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury." Physiol Rev 99, no. 2 (2019): 1047-78. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, R., A. L. Mausset-Bonnefont, C. Jorgensen, P. Louis-Plence, and J. M. Brondello. "Cellular Senescence Impact on Immune Cell Fate and Function." Aging Cell 15, no. 3 (2016): 400-6. [CrossRef]

- Kang, T. W., T. Yevsa, N. Woller, L. Hoenicke, T. Wuestefeld, D. Dauch, A. Hohmeyer, M. Gereke, R. Rudalska, A. Potapova, M. Iken, M. Vucur, S. Weiss, M. Heikenwalder, S. Khan, J. Gil, D. Bruder, M. Manns, P. Schirmacher, F. Tacke, M. Ott, T. Luedde, T. Longerich, S. Kubicka, and L. Zender. "Senescence Surveillance of Pre-Malignant Hepatocytes Limits Liver Cancer Development." Nature 479, no. 7374 (2011): 547-51. [CrossRef]

- Lecot, P., F. Alimirah, P. Y. Desprez, J. Campisi, and C. Wiley. "Context-Dependent Effects of Cellular Senescence in Cancer Development." Br J Cancer 114, no. 11 (2016): 1180-4. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Imoto, H., S. Minami, T. Shioda, Y. Yamashita, S. Sakai, S. Maeda, T. Yamamoto, S. Oki, M. Takashima, T. Yamamuro, K. Yanagawa, R. Edahiro, M. Iwatani, M. So, A. Tokumura, T. Abe, R. Imamura, N. Nonomura, Y. Okada, D. E. Ayer, H. Ogawa, E. Hara, Y. Takabatake, Y. Isaka, S. Nakamura, and T. Yoshimori. "Age-Associated Decline of Mondoa Drives Cellular Senescence through Impaired Autophagy and Mitochondrial Homeostasis." Cell Rep 38, no. 9 (2022): 110444. [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva, V., A. Cisneros, V. Sica, O. Deryagin, Y. Lai, S. Jung, E. Andres, J. An, J. Segales, L. Ortet, V. Lukesova, G. Volpe, A. Benguria, A. Dopazo, S. A. Benitah, Y. Urano, A. Del Sol, M. A. Esteban, Y. Ohkawa, A. L. Serrano, E. Perdiguero, and P. Munoz-Canoves. "Senescence Atlas Reveals an Aged-Like Inflamed Niche That Blunts Muscle Regeneration." Nature 613, no. 7942 (2023): 169-78. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., L. E. Pitcher, V. Prahalad, L. J. Niedernhofer, and P. D. Robbins. "Targeting Cellular Senescence with Senotherapeutics: Senolytics and Senomorphics." FEBS J 290, no. 5 (2023): 1362-83. [CrossRef]

- Whetstone, C. E., M. Ranjbar, H. Omer, R. P. Cusack, and G. M. Gauvreau. "The Role of Airway Epithelial Cell Alarmins in Asthma." Cells 11, no. 7 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Heijink, I. H., M. C. Nawijn, and T. L. Hackett. "Airway Epithelial Barrier Function Regulates the Pathogenesis of Allergic Asthma." Clin Exp Allergy 44, no. 5 (2014): 620-30. [CrossRef]

- Roth-Walter, F., I. M. Adcock, C. Benito-Villalvilla, R. Bianchini, L. Bjermer, G. Caramori, L. Cari, K. F. Chung, Z. Diamant, I. Eguiluz-Gracia, E. F. Knol, M. Jesenak, F. Levi-Schaffer, G. Nocentini, L. O'Mahony, O. Palomares, F. Redegeld, M. Sokolowska, Bcam Van Esch, and C. Stellato. "Metabolic Pathways in Immune Senescence and Inflammaging: Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Chronic Inflammatory Lung Diseases. An Eaaci Position Paper from the Task Force for Immunopharmacology." Allergy 79, no. 5 (2024): 1089-122. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R. J., and C. M. Lloyd. "Regulation of Immune Responses by the Airway Epithelial Cell Landscape." Nat Rev Immunol 21, no. 6 (2021): 347-62. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Z. Zeng, J. Yu, B. Tang, R. Tang, and R. Xiao. "The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: An Environmental Effector in the Pathogenesis of Fibrosis." Pharmacol Res 160 (2020): 105180. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Y. Shen, Y. Zhao, J. Wang, X. Zhang, W. Tu, W. Kaufman, J. Feng, and P. Gao. "Epithelial Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Protects from Mucus Production by Inhibiting Ros-Triggered Nlrp3 Inflammasome in Asthma." Front Immunol 12, no. 4810 (2021): 767508. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Y. Zhao, X. Zhang, W. Tu, R. Wan, Y. Shen, Y. Zhang, R. Trivedi, and P. Gao. "Type Ii Alveolar Epithelial Cell Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Protects against Allergic Airway Inflammation through Controlling Cell Autophagy." Front Immunol 13 (2022): 964575. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rubio, R., O. Amador-Muñoz, I. Rosas-Pérez, Y. Sánchez-Pérez, C. García-Cuéllar, P. Segura-Medina, Á Osornio-Vargas, and A. De Vizcaya-Ruiz. "Pm(2.5) Induces Airway Hyperresponsiveness and Inflammation Via the Ahr Pathway in a Sensitized Guinea Pig Asthma-Like Model." Toxicology 465 (2022): 153026. [CrossRef]

- Xia, M., L. Viera-Hutchins, M. Garcia-Lloret, M. Noval Rivas, P. Wise, S. A. McGhee, Z. K. Chatila, N. Daher, C. Sioutas, and T. A. Chatila. "Vehicular Exhaust Particles Promote Allergic Airway Inflammation through an Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Notch Signaling Cascade." J Allergy Clin Immunol 136, no. 2 (2015): 441-53. [CrossRef]

- Tu, W., X. Hu, R. Wan, X. Xiao, Y. Shen, P. Srikaram, S. N. Avvaru, F. Yang, F. Pi, Y. Zhou, M. Wan, and P. Gao. "Effective Delivery of Mir-511-3p with Mannose-Decorated Exosomes with Rna Nanoparticles Confers Protection against Asthma." J Control Release (2023). [CrossRef]

- Boike, L., A. G. Cioffi, F. C. Majewski, J. Co, N. J. Henning, M. D. Jones, G. Liu, J. M. McKenna, J. A. Tallarico, M. Schirle, and D. K. Nomura. "Discovery of a Functional Covalent Ligand Targeting an Intrinsically Disordered Cysteine within Myc." Cell Chem Biol 28, no. 1 (2021): 4-13.e17. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B. P., M. S. Denison, H. Novak, B. A. Vorderstrasse, N. Harrer, W. Neruda, C. Reichel, and M. Woisetschlager. "Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Is Essential for Mediating the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Novel Low-Molecular-Weight Compound." Blood 112, no. 4 (2008): 1158-65. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Y. Shen, Y. Zhao, J. Wang, X. Zhang, W. Tu, W. Kaufman, J. Feng, and P. Gao. "Epithelial Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Protects from Mucus Production by Inhibiting Ros-Triggered Nlrp3 Inflammasome in Asthma." Front Immunol 12 (2021): 767508. [CrossRef]

- Do, D. C., Y. Zhang, W. Tu, X. Hu, X. Xiao, J. Chen, H. Hao, Z. Liu, J. Li, S. K. Huang, M. Wan, and P. Gao. "Type Ii Alveolar Epithelial Cell-Specific Loss of Rhoa Exacerbates Allergic Airway Inflammation through Slc26a4." JCI Insight 6, no. 14 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Do, D. C., J. Mu, X. Ke, K. Sachdeva, Z. Qin, M. Wan, F. T. Ishmael, and P. Gao. "Mir-511-3p Protects against Cockroach Allergen-Induced Lung Inflammation by Antagonizing Ccl2." JCI Insight 4, no. 20 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., D. C. Do, X. Hu, J. Wang, Y. Zhao, S. Mishra, X. Zhang, M. Wan, and P. Gao. "Camkii Oxidation Regulates Cockroach Allergen-Induced Mitophagy in Asthma." J Allergy Clin Immunol 147, no. 4 (2021): 1464-77.e11. [CrossRef]

- Ibabao, C. N., R. P. Bunaciu, D. M. Schaefer, and A. Yen. "The Ahr Agonist Vaf347 Augments Retinoic Acid-Induced Differentiation in Leukemia Cells." FEBS Open Bio 5 (2015): 308-18. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., E. Hu, S. Xu, M. Chen, P. Guo, Z. Dai, T. Feng, L. Zhou, W. Tang, L. Zhan, X. Fu, S. Liu, X. Bo, and G. Yu. "Clusterprofiler 4.0: A Universal Enrichment Tool for Interpreting Omics Data." Innovation (Camb) 2, no. 3 (2021): 100141. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z., R. Eils, and M. Schlesner. "Complex Heatmaps Reveal Patterns and Correlations in Multidimensional Genomic Data." Bioinformatics 32, no. 18 (2016): 2847-9. [CrossRef]

- Alladina, J., N. P. Smith, T. Kooistra, K. Slowikowski, I. J. Kernin, J. Deguine, H. L. Keen, K. Manakongtreecheep, J. Tantivit, R. A. Rahimi, S. L. Sheng, N. D. Nguyen, A. M. Haring, F. L. Giacona, L. P. Hariri, R. J. Xavier, A. D. Luster, A. C. Villani, J. L. Cho, and B. D. Medoff. "A Human Model of Asthma Exacerbation Reveals Transcriptional Programs and Cell Circuits Specific to Allergic Asthma." Sci Immunol 8, no. 83 (2023): eabq6352. [CrossRef]

- Seth, S., S. Mallik, T. Bhadra, and Z. Zhao. "Dimensionality Reduction and Louvain Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering for Cluster-Specified Frequent Biomarker Discovery in Single-Cell Sequencing Data." Front Genet 13 (2022): 828479. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., J. Song, J. He, X. Zhang, Z. Lv, F. Dong, and J. Deng. "Hsa_Circ_0008500 Regulates Benzo(a)Pyrene-Loaded Gypsum-Induced Inflammation and Apoptosis in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells Via Activation of Ahr/C-Myc Pathways." Toxicol Lett 394 (2024): 46-56. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z., K. Chen, Z. Wang, F. Zheng, H. Ni, Y. Shang, Y. Wang, D. Xia, Y. Wu, and J. Qian. "Benzo[a]Pyrene Reduces Cellular Senescence in Ovarian Cancer by Stabilizing C-Myc Independently of DNA Damage." Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 301 (2025): 118476. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L., Z. Wang, Z. Guo, H. Zhang, Y. Liu, H. Zhang, H. Jin, F. Xu, X. Wang, C. Xie, H. Guo, T. Wang, Y. Lin, Q. Zhao, P. Zhou, J. Tan, J. X. Bei, P. Huang, J. Liu, and X. Xia. "Tryptophan Metabolite Indole-3-Aldehyde Induces Ahr and C-Myc Degradation to Promote Tumor Immunogenicity." Adv Sci (Weinh) (2025): e09533. [CrossRef]

- Akinbami, L. J., J. E. Moorman, A. E. Simon, and K. C. Schoendorf. "Trends in Racial Disparities for Asthma Outcomes among Children 0 to 17 Years, 2001-2010." J Allergy Clin Immunol 134, no. 3 (2014): 547-53.e5. [CrossRef]

- Curto, E., A. Crespo-Lessmann, M. V. Gonzalez-Gutierrez, S. Bardagi, C. Canete, C. Pellicer, T. Bazus, M. D. C. Vennera, C. Martinez, and V. Plaza. "Is Asthma in the Elderly Different? Functional and Clinical Characteristics of Asthma in Individuals Aged 65 Years and Older." Asthma Res Pract 5 (2019): 2. [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, J. A., V. Plaza, J. Dominguez-Ortega, J. Serrano, C. Cisneros, A. Padilla, M. Anton Girones, M. Mosteiro, E. Martinez Moragon, J. M. Olaguibel Rivera, J. Delgado, J. L. Garcia Rivero, C. Martinez Rivera, J. J. Garrido, S. Quirce, and Gemaforum Task Force. "Asthma, Comorbidities, and Aggravating Circumstances: The Gema-Forum Ii Task Force." J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 30, no. 2 (2020): 140-43. [CrossRef]

- Busse, P. J., T. F. Zhang, K. Srivastava, B. Schofield, and X. M. Li. "Effect of Ageing on Pulmonary Inflammation, Airway Hyperresponsiveness and T and B Cell Responses in Antigen-Sensitized and -Challenged Mice." Clin Exp Allergy 37, no. 9 (2007): 1392-403. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Y., S. Y. Lee, C. K. Rhee, S. J. Kim, S. S. Kwon, and Y. K. Kim. "Effect of Aging on Airway Remodeling and Muscarinic Receptors in a Murine Acute Asthma Model." Clin Interv Aging 8 (2013): 1393-403. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., L. J. Hickson, A. Eirin, J. L. Kirkland, and L. O. Lerman. "Cellular Senescence: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown." Nat Rev Nephrol 18, no. 10 (2022): 611-27. [CrossRef]

- Schuliga, M., J. Read, and D. A. Knight. "Ageing Mechanisms That Contribute to Tissue Remodeling in Lung Disease." Ageing Res Rev 70 (2021): 101405. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Y., G. P. Souroullas, B. O. Diekman, J. Krishnamurthy, B. M. Hall, J. A. Sorrentino, J. S. Parker, G. A. Sessions, A. V. Gudkov, and N. E. Sharpless. "Cells Exhibiting Strong P16(Ink4a) Promoter Activation in Vivo Display Features of Senescence." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, no. 7 (2019): 2603-11.

- Baker, D. J., T. Wijshake, T. Tchkonia, N. K. LeBrasseur, B. G. Childs, B. van de Sluis, J. L. Kirkland, and J. M. van Deursen. "Clearance of P16ink4a-Positive Senescent Cells Delays Ageing-Associated Disorders." Nature 479, no. 7372 (2011): 232-6. [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, W., M. Rokicki, J. Wojtacha, and A. Dzeljijli. "The Role and Importance of Club Cells (Clara Cells) in the Pathogenesis of Some Respiratory Diseases." Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol 13, no. 1 (2016): 26-30. [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J. B., N. F. Li, N. W. Bartlett, and B. W. Richmond. "An Update in Club Cell Biology and Its Potential Relevance to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease." Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 324, no. 5 (2023): L652-L65. [CrossRef]

- Poulain-Godefroy, O., M. Boute, J. Carrard, D. Alvarez-Simon, A. Tsicopoulos, and P. de Nadai. "The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Asthma: Friend or Foe?" Int J Mol Sci 21, no. 22 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Carrard, J., P. Marquillies, M. Pichavant, N. Visez, S. Lanone, A. Tsicopoulos, C. Chenivesse, A. Scherpereel, and P. de Nadai. "Chronic Exposure to Benzo(a)Pyrene-Coupled Nanoparticles Worsens Inflammation in a Mite-Induced Asthma Mouse Model." Allergy 76, no. 5 (2021): 1562-65. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J. I., M. Boguniewicz, F. J. Quintana, R. A. Clark, L. Gross, I. Hirano, A. M. Tallman, P. M. Brown, D. Fredericks, D. S. Rubenstein, and K. A. McHale. "Tapinarof Validates the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor as a Therapeutic Target: A Clinical Review." J Allergy Clin Immunol 154, no. 1 (2024): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. H., H. C. Chuang, G. Hsiao, T. Y. Hou, C. C. Wang, S. C. Huang, B. Y. Li, and Y. L. Lee. "Acteoside Exerts Immunomodulatory Effects on Dendritic Cells Via Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation and Ameliorates Th2-Mediated Allergic Asthma by Inducing Foxp3(+) Regulatory T Cells." Int Immunopharmacol 106 (2022): 108603. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. K., B. A. Lewis, and D. Levens. "Myc: A Complex Problem." Trends Cell Biol 33, no. 3 (2023): 235-46. [CrossRef]

- Gabay, M., Y. Li, and D. W. Felsher. "Myc Activation Is a Hallmark of Cancer Initiation and Maintenance." Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4, no. 6 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Felsher, D. W. "Cancer Revoked: Oncogenes as Therapeutic Targets." Nat Rev Cancer 3, no. 5 (2003): 375-80. [CrossRef]

- Shachaf, C. M., and D. W. Felsher. "Tumor Dormancy and Myc Inactivation: Pushing Cancer to the Brink of Normalcy." Cancer Res 65, no. 11 (2005): 4471-4. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L., J. Pan, M. Liang, M. A. Pasha, X. Shen, S. S. D'Souza, I. T. H. Fung, Y. Wang, G. Patel, D. D. Tang, and Q. Yang. "A Critical Role for C-Myc in Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Activation." Allergy 75, no. 4 (2020): 841-52. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).