1. Introduction

Microbial life is the oldest and most enduring form of life on Earth, with lineages that can be traced back billions of years to the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA), which recent estimates place at ~4.2 billion years ago[

1]. Among these lineages, some persist as “living fossils,” partially retaining potentially ancient traits that illuminate the biology of Earth’s earliest organisms while continuing to adapt to modern ecological niches. The Asgard archaea represent one of the most striking examples of such lineages. Recently discovered through metagenomic analysis of deep marine sediments in 2015[

2,

3], they have since reshaped our understanding of early cellular evolution and the origins of eukaryotic complexity [

4].

The significance of Asgard archaea lies not only in their genetic and structural repertoire but also in how their discovery has transformed models of life’s evolutionary tree. Before their recognition, hypotheses of eukaryotic origins were dominated by two frameworks. The three-domain model, proposed by Woese and Fox in the 1970s, treated Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryotes as distinct primary lineages [

5]. Later, Cox and colleagues (2008) advanced the two-domain, or “ecocyte,” hypothesis, suggesting that eukaryotes arose from within the archaeal domain but without pinpointing a specific lineage of origin [

6]. While both frameworks were historically influential, they left unresolved the evolutionary placement of eukaryotes. This long-standing gap set the stage for the transformative impact of Asgard archaea.

Genomic studies of Asgard lineages have revealed a striking enrichment of eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs), including components of cytoskeletal regulation, membrane remodeling, and intracellular trafficking [

2,

7]. These findings provided compelling evidence that eukaryotes branch from within the archaeal domain, lending strong support to the modern two-domain model of life [

8,

9]. Cultivation of Asgard species, though technically challenging, has confirmed aspects of their predicted biology, while structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy have revealed intriguing membrane protrusions and compartment-like features that blur traditional distinctions between prokaryotes and eukaryotes [

10]. Together, these insights have repositioned Asgards from obscure deep-sea microbes to pivotal players in debates about the origins of eukaryotic complexity.

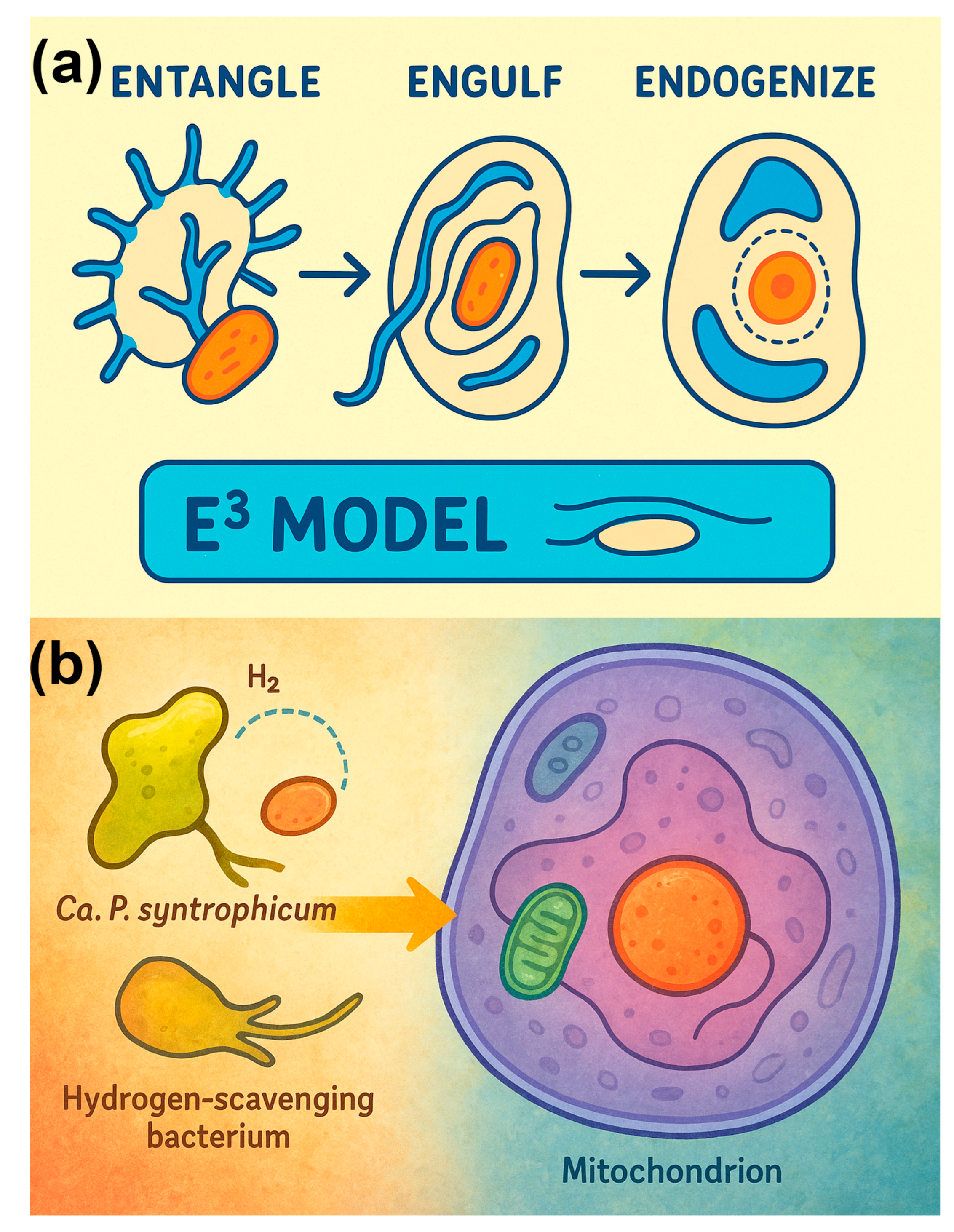

Recent work on

Ca. P. syntrophicum, one of the first cultured Asgard representatives, has added critical nuance to this picture[

10]. Although earlier predictions suggested that Asgard archaea might contain eukaryote-like intracellular complexes, no true organelle-like structures have been observed[

10]. Instead,

Ca. P. syntrophicum displays a morphologically complex architecture, including unusually long and branching membrane protrusions (

Figure 1)[

10]. These unique structures are thought to facilitate syntrophic interactions with bacterial partners, particularly methanogens. Based on these findings, Imachi and colleagues proposed the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model of eukaryogenesis, in which physical interactions via protrusions allowed Asgard hosts to enmesh and eventually internalize symbiotic partners, laying the groundwork for the evolution of eukaryotic cells[

10].

Ecologically, Asgard archaea occupy extreme, energy-limited environments such as hydrothermal vents, methane seeps, and deep-sea sediments[

3,

12]. In these contexts, they often engage in syntrophic associations with bacteria, reflecting metabolic interdependencies that may echo ancient microbial consortia from which complex cells emerged[

10]. Their capacity to thrive in such conditions not only offers insight into early Earth environments but also makes them highly relevant to astrobiology. The subsurface oceans of icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus, or the past hydrothermal activity on Mars, for example, present extreme environments that may parallel the niches where Asgard archaea are found today[

13]. Studying their biology thus informs strategies for detecting potential extraterrestrial life and refining the biosignatures that scientists search for in planetary exploration. Importantly, the obligate nature of many of these partnerships raises the question of what occurs when syntrophic bacterial partners are removed—a topic of growing interest in ecological research that could be expanded into a dedicated discussion of Asgard mutualisms.

The study of Asgard archaea has also been propelled by methodological advances. High-throughput metagenomics and single-cell genomics have enabled their discovery and comparative analysis, while transcriptomics and proteomics have provided windows into gene expression and protein function of Asgards under different environmental conditions[

14]. Structural biology tools such as cryo-electron microscopy are also revealing previously unappreciated cellular architectures[

10]. Together, these approaches are generating a holistic picture of Asgard biology, albeit one that remains incomplete given the limited number of cultured strains and the difficulties of working with extremophiles in a laboratory setting.

This review synthesizes current knowledge of Asgard archaea as living fossils that illuminate the evolutionary bridge between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. We highlight recent discoveries from the fields of genomics, structural biology, and ecology, and discuss their significance for understanding the origin of complex life. Finally, we consider future directions, including innovative sequencing technologies and astrobiological applications that will continue to expand our understanding of these enigmatic organisms.

2. Materials and Methods

Given that this manuscript is a narrative review rather than a primary research report, our methods focus on how relevant literature was identified, evaluated, and synthesized. We followed a structured approach designed to capture the breadth of discoveries on Asgard archaea while ensuring that only high-quality, peer-reviewed studies were included.

Literature Search Strategy. We conducted systematic searches of peer-reviewed scientific literature using various combinations of the keywords “Asgard archaea”, “Lokiarchaeota”, “Thorarchaeota”, “Odinarchaeota”, “Heimdallarchaeota”, “eukaryotic signature proteins”, “extremophiles”, and “cryo-electron microscopy archaea” on several search engines including PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Searches were limited to publications from 2015—the year of the first Asgard genome discovery—through September-2025. Additionally, the reference lists of recent reviews were forward and backward searched to identify additional relevant papers to summarize in our review.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. We included studies that presented original data on the genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, structural biology, or ecology of Asgard archaea (

Table 1). Both culture-dependent and culture-independent studies were considered. Excluded from analysis were non-peer-reviewed reports, commentaries without new data, and articles that only tangentially referenced Asgard archaea without presenting substantive findings.

Data Extraction and Thematic Organization. Each study included in our review was categorized into thematic domains: (1) genomics and evolutionary relationships, (2) structural and cellular biology, (3) metabolic pathways and ecological interactions, (4) methodological advances in Asgard research, and (5) astrobiological implications. Key findings were extracted into a comparative matrix to identify converging lines of evidence and knowledge gaps across these major themes.

Methodological Advances. We highlighted the role of cutting-edge techniques such as cryo-electron tomography, long-read sequencing, and single-cell omics in uncovering new aspects of Asgard biology. These methods were evaluated not only for the findings they produced but also for their potential to resolve ongoing debates about Asgard’s evolutionary position within the tree of life.

Astrobiological Context. Studies of Asgard archaea from extreme environments—such as hydrothermal vents, methane seeps, and anoxic sediments—were considered through the lens of analog environments on other planetary bodies. We included both direct data on Asgard metabolism and broader discussions of biosignature detection strategies relevant to astrobiology.

Review Limitations. As a literature-based synthesis, this review is limited by the relatively small number of cultured Asgard strains and the heavy reliance on metagenomic reconstructions. Many reported features remain hypothetical until validated experimentally. By explicitly noting these limitations, we aim to provide a balanced assessment of current knowledge and future directions.

3. Discussion

3.1. Genomic Insights and Eukaryotic Signature Proteins

The defining feature of Asgard archaea is their genomic repertoire, which contains an expanded complement of eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs)[

18]. These include homologs of actin, profilin, tubulin-like proteins, and components of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) system[

18]. The presence of ESPs suggests that Asgard archaea harbor the genetic toolkit necessary for membrane remodeling, cytoskeletal regulation, and vesicle trafficking—processes traditionally viewed as exclusive to eukaryotes[

16]. The functional categories of these ESPs and their predicted interactions with cellular structures are summarized schematically in

Figure 2a (see also,

Table 2).

The distribution of ESPs is not uniform across Asgard phyla but instead reflects a lineage-specific mosaic. Current classifications recognize between 12 and 18 Asgard phyla, depending on sampling depth and taxonomic criteria, and their ESP complements vary considerably (

Table 2;

Figure 2b)[

17]. For example,

Heimdallarchaeota stand out as being particularly enriched in ESPs related to informational processing and cytoskeletal regulation, with genomes encoding more than 80 distinct ESPs[

17].

Lokiarchaeota and

Thorarchaeota, in contrast, typically encode between 40 and 60 ESPs, reflecting a numerically intermediate repertoire[

17]. The number of ESPs found in

Odinarchaeota are more modest, ranging between ~25–35, while other archaeal lineages such as DPANN archaea or

Euryarchaeota contain only a handful or none[

17].

This variation, illustrated in the clustered heatmap of

Figure 2b, highlights evolutionary affinities within the superphylum. Lineages with more extensive ESP repertoires, such as

Heimdallarchaeota, cluster closer to eukaryotic protein sets, while those with sparser repertoires occupy more basal positions[

19]. These patterns suggest that the Asgard superphylum does not represent a single, uniform bridge between prokaryotes and eukaryotes, but rather a spectrum of genomic complexity that may collectively illuminates different stages of eukaryogenesis[

19]. Such diversity emphasizes the importance of comparative approaches across multiple lineages rather than focusing narrowly on a single “closest relative,” as each phylum provides complementary insights into the gradual assembly of eukaryotic cellular complexity[

19].

The distribution of ESPs across Asgard lineages highlights both shared ancestry and lineage-specific adaptations (

Table 2).

Heimdallarchaeota appear to harbor the richest repertoire of ESPs (~80–90), including cytoskeletal components (actin, profilin, tubulin-like proteins) and ESCRT machinery, reinforcing their status as leading candidates for the closest archaeal relatives to the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) [

14].

Lokiarchaeota and

Thorarchaeota display intermediate complements, with robust but somewhat streamlined ESP profiles that overlap in actin and ESCRT systems yet diverge in metabolic signatures[

14].

Odinarchaeota, by contrast, retain only a limited subset of ESPs (~25–35), suggesting either secondary gene loss or niche-driven reductive evolution[

14].

The diversity contributed by additional Asgard groups (e.g.,

Hermodarchaeota,

Freyrarchaeota) further highlights the mosaic nature of ESP evolution within the superphylum[

19]. Comparisons with non-Asgard lineages such as DPANN and

Euryarchaeota underscore the distinctiveness of Asgards: although occasional ESP homologs are detected in these clades, they are sparse, often truncated, and lack the integrated repertoire that characterizes Asgards (

Table 2) [

28]. While

Table 2 summarizes these differences in tabular form, complementary visualizations can provide greater clarity. For example, we propose that composite distance matrices can juxtapose ecological associations of Asgard lineages with environmental parameters against pairwise overlap in ESP repertoires, highlighting both environmental and genomic dimensions of Asgard distinctiveness. This gradient in ESP content across lineages suggests a dynamic evolutionary landscape where ecological context, phylogenomic distance, and selective pressures interact to shape the conservation or loss of ESP modules [

28]. A promising next step will be to systematically integrate phylogenomic trees with environmental distance matrices to test whether specific ESP subsets preferentially correlate with ecological variables such as salinity, temperature, pH, oxygen concentration, and pressure—a direction we are actively considering for future work.

Bridging genomic predictions with cellular biology, cultivation and structural studies have begun to validate the functional relevance of these ESP repertoires[

18]. For example,

Ca. P. syntrophicum has been shown to produce long, branching protrusions that may reflect cytoskeletal regulation and membrane remodeling capacities predicted from its ESP complement[

18]. Cryo-electron microscopy and live imaging have further revealed vesicle-like compartments and membrane invaginations in other Asgard lineages[

38,

39], reinforcing the idea that the genomic toolkit is expressed in morphological innovations. Together, these data provide critical evidence that Asgard archaea translate their ESP repertoires into cellular features that blur the traditional boundaries between prokaryotic simplicity and eukaryotic complexity, thereby setting the stage for deeper exploration of their structural biology.

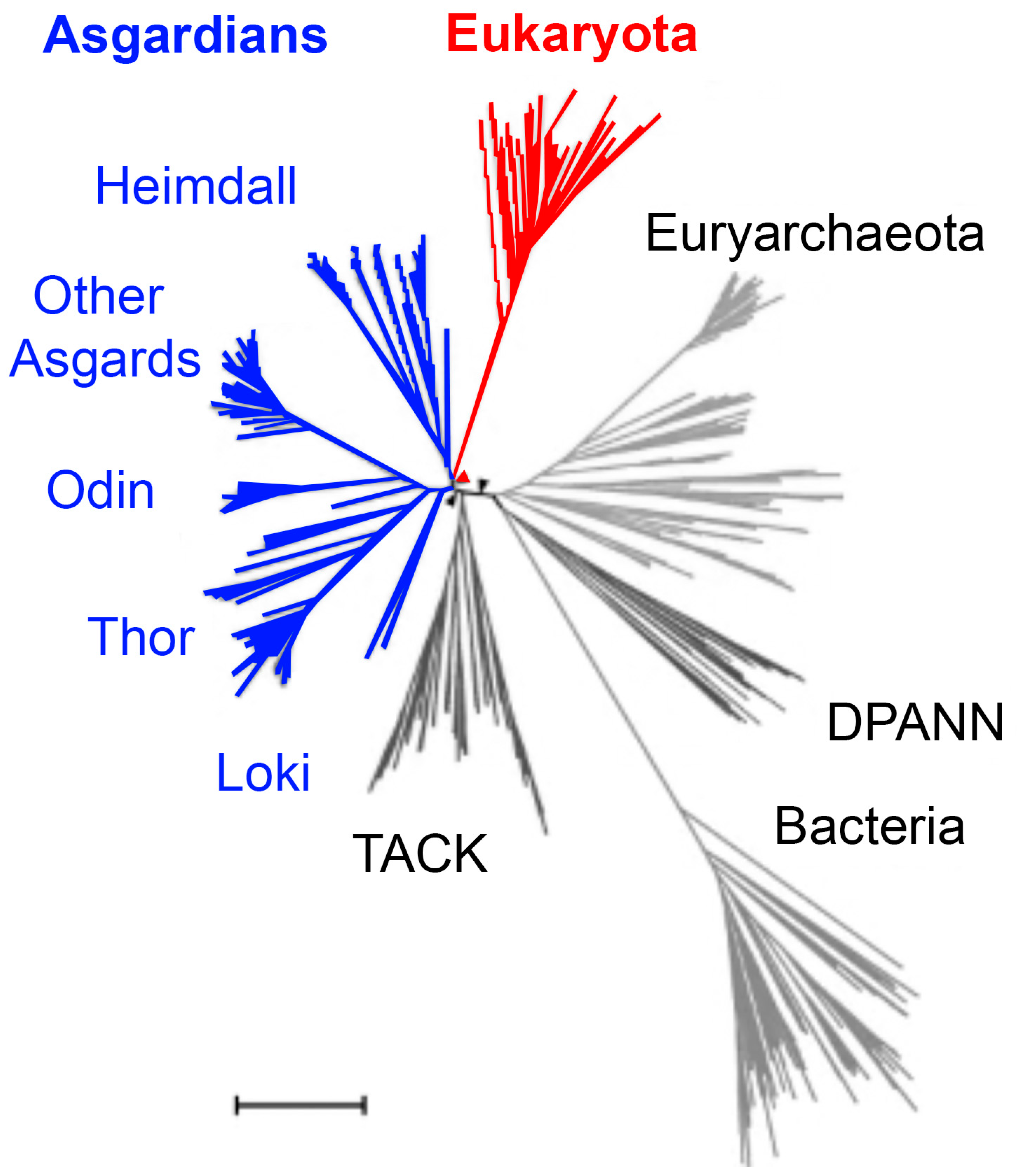

3.2. Deep Origin of Eukaryotes Outside of Heimdallarchaea

Comparative analyses based on whole-genome datasets and large-scale phylogenomic reconstructions (often using >50 conserved marker proteins) have consistently placed Asgard archaea as the closest archaeal relatives of eukaryotes, thereby supporting the two-domain model of life in which eukaryotes branched from within the archaeal domain (

Figure 4, red triangle) [

19,

40]. However, it is important to acknowledge methodological variation: some studies using alternative marker sets, different evolutionary models, or incomplete genome assemblies have produced trees that weaken or challenge this placement, instead positioning eukaryotes more distantly within the archaeal radiation [

19,

40]. These discrepancies underscore the importance of continuing to refine genome sampling, assembly quality, and phylogenetic methodology [

41].

Recent advances have dramatically reshaped this discussion. Zhang and colleagues (2025) generated more than 200 high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes, greatly expanding the known phylogenetic diversity of Asgard archaea and identifying 16 new lineages at the genus level or higher [

41]. Their phylogenomic reconstructions suggest that eukaryotes originated before the diversification of all sampled

Heimdallarchaeia (

Figure 3, red triangle), in contrast to earlier models that placed them more specifically within

Hodarchaeales [

41]. This re-interpretation highlights the instability of phylogenetic placement when genome completeness, taxon sampling, or marker choice vary, and it illustrates how ongoing discovery of new Asgard lineages can refine or even overturn earlier hypotheses [

41].

A key insight from this work is the recognition of the chimeric nature of certain lineages, particularly

Njordarchaeales, which appear to contain genomic contributions from both Asgard archaea and their sister phylum, the TACK (

Thaumarchaeota, Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota, Korarchaeota) superphylum (

Figure 3, black triangles) [

41]. Such mosaicism complicates efforts to cleanly resolve the archaeal branch that gave rise to eukaryotes and suggests that horizontal gene transfer and genetic admixture were important forces shaping early archaeal evolution.

Molecular clock analyses further suggest that the last common ancestor of Asgard archaea and eukaryotes arose before the Great Oxidation Event, mediated by photosynthetic organisms ~2.45 billion years ago [

42,

43], implying that this ancestor thrived in an anaerobic Earth system [

41]. Ancestral state reconstructions point toward a hydrogen-dependent acetogenic metabolism [

41], lending support to the hydrogen hypothesis of eukaryogenesis by Martin and Müller (1998) [

44]. In this hypothesis, eukaryotes arose from the partnership of an H₂-consuming archaeal host and an H₂-producing alphaproteobacterial symbiont, the precursor to the mitochondria, with metabolic syntrophy setting the stage for endosymbiosis [

44].

Taken together, these findings suggest that the evolutionary trajectory from Asgard archaea to eukaryotes may have hinged less on the gradual accretion of eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs) and more on the metabolic context in which symbiosis occurred. As Martin and Müller emphasized in their original formulation of the hydrogen hypothesis, structural innovations such as cytoskeletal filaments, membrane remodeling proteins, or endomembrane precursors—while striking—may represent downstream elaborations rather than the primary drivers of eukaryogenesis [

44]. Instead, the capacity for hydrogen metabolism, and later adaptation to rising oxygen levels before and after the Great Oxidation Event [

42,

43], provided the ecological and energetic foundation for stable host–symbiont integration.

In this light, ESPs may be something of a red herring: indispensable for explaining the later cellular complexity of eukaryotes, yet secondary to the metabolic imperatives that forged the original archaeal–bacterial partnership. Their emergence might be viewed as “the ghost of metabolic selection past”—a vestige of the ancient ecological and energetic constraints that drove the first endosymbiotic unions during the oxygenation of Earth’s biosphere. Under this view, it was not the cytoskeleton, vesicle trafficking, or informational machinery that first enabled eukaryogenesis, but rather the metabolic dependencies that forced sustained physical and genetic integration between archaeal hosts and bacterial symbionts. Only once that metabolic foundation stabilized could structural innovations like membrane remodeling and cytoskeletal control begin to evolve. Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) now allow direct visualization of these structural hallmarks in Asgard archaea, providing unprecedented insight into how such features may have arisen from simpler archaeal precursors.

3.3. Cellular Structures Revealed by Cryo-Electron Microscopy

If the metabolic symbiosis that united archaeal hosts and bacterial partners represents the foundational act of eukaryogenesis, then the subsequent emergence of cellular complexity—manifest in cytoskeletal scaffolds, vesicle systems, and dynamic membranes—was its structural consequence. While genomic surveys and comparative analyses (Figure 2; Table 2) map the distribution of eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs) across Asgard lineages, it is structural biology that provides the decisive bridge between gene content and cell morphology. Recent breakthroughs in cryo-electron tomography and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have begun to visualize how these molecular repertoires translate into physical form.

Imaging of

Candidatus Lokiarchaeum ossiferum, one of the first cultivated Asgard representatives, has revealed striking features including a dynamic actin-based cytoskeleton and extensive, branching membrane protrusions[

18] (

Figure 1). These protrusions—often several micrometers in length—evoke the appearance of primitive filopodia or lamellipodia in early eukaryotes. They likely served ecological functions central to the archaeal–bacterial symbiosis, such as mediating surface contact, nutrient transfer, or electron exchange with syntrophic partners. Thus, structural observations from cryo-electron microscopy not only corroborate genomic predictions but also illuminate the cellular mechanisms through which ancient metabolic cooperation may have evolved into the structural complexity that defines eukaryotic life.

Beyond external morphology, cryo-electron tomograms have also revealed internal membrane invaginations and compartment-like vesicular structures[

45]. Although their exact functions remain unresolved, these invaginations suggest that Asgard cells were capable of limited forms of intracellular compartmentalization, potentially representing a steppingstone toward the endomembrane systems of eukaryotes[

45]. The alignment of these ultrastructural observations with ESP profiles—for example, the presence of actin, profilin, and ESCRT homologs (

Table 3)—provides functional validation that genomic predictions may map onto tangible cellular machinery[

45].

Importantly, these findings underscore that Asgard archaea are not merely “genomes with ESPs,” but living organisms that deploy structural innovations in ways consistent with their genomic potential[

14,

46]. The capacity to generate cytoskeletal scaffolds and membrane remodeling machinery supports models of eukaryogenesis that emphasize cell biological plasticity prior to endosymbiosis. In particular, the protrusions of

Ca. P. syntrophicum have been interpreted as possible interfaces for engulfing symbiotic partners (

Figure 1), offering a plausible mechanistic link between archaeal host complexity and the acquisition of mitochondria[

14,

46].

Nevertheless, the structural dataset remains limited to a few cultured representatives from only a handful of Asgard phyla and isolated ultrastructural observations. Open questions include whether the elaborated membrane protrusions and cytoskeletal assemblies observed in Lokiarchaeum represent a universal trait across Asgard lineages or a lineage-specific adaptation shaped by environmental context. It also remains unclear how factors such as redox potential, syntrophic partners, or habitat chemistry modulate the expression and dynamics of these features.

Future work integrating cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) with live-cell imaging, genetic manipulation, and biochemical reconstitution of ESP homologs will be essential to move beyond descriptive morphology toward mechanistic insight. Such studies will help resolve how and when cytoskeletal and membrane systems became stably integrated following the archaeal–bacterial symbiosis that predated the Great Oxidation Event. Together, these advances in cryo-electron microscopy have transformed Asgard archaea from abstract genomic constructs into living cellular models that embody key transitional states in the evolution of eukaryotic complexity. By linking ESP-driven morphology to metabolic and ecological context, they set the stage for refined hypotheses about how structural innovation facilitated symbiont integration.

3.4. Updating the Inside-Out Model with the E³ Model

The discovery and cultivation of

Ca. P. syntrophicum have provided crucial new insights into the origin of eukaryotic cells[

14,

46]. In particular, the recently developed entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model builds upon the earlier Inside-Out model by refining the mechanism of symbiont incorporation. Whereas the Inside-Out model of Baum and Baum (2014) offered a broad conceptual framework for the evolution of eukaryotic cell architecture without invoking classical phagocytosis[

55], the E³ model of Imachi et al. (2020) leverages direct morphological observations of Asgard archaea—most notably the long, branching protrusions revealed by cryo-ET (

Figure 1 and interpreted in

Figure 4).

In contrast to purely genomic or “metabolic-first” models emphasizing biochemical complementarity alone, the E³ model links those metabolic exchanges to tangible cell biology. The protrusions observed in

Ca. P. syntrophicum and other Asgard lineages not only enable contact-dependent metabolite transfer but also provide a structural template for progressive envelopment and eventual endogenization of the bacterial symbiont (

Figure 5a;

Table 4) [

10]. In this sense, the E³ model operationalizes the metabolic partnership at the heart of early eukaryogenesis, transforming it from an abstract symbiotic hypothesis into a morphologically testable evolutionary pathway.

The Inside-Out model posits that outward blebbing of the archaeal host generated compartments that eventually evolved into the cytoplasm and endomembrane system, with engulfment occurring through gradual enclosure of bacterial partners[

55]. This framework elegantly explained the coevolution of nuclear, cytoplasmic, and endomembrane structures but left unspecified the precise mechanics of engulfment in organisms lacking phagocytosis. The E³ model updates this scenario by providing explicit steps [

10] as shown in

Figure 5a:

Entangle – Asgard protrusions enmesh or tether bacterial symbionts in intimate syntrophic interactions.

Engulf – The enmeshed bacteria are progressively surrounded by host protrusions, enabling enclosure without requiring an active phagocytic apparatus.

Endogenize – The engulfed bacterium transitions into a permanent endosymbiont, ultimately giving rise to mitochondria.

Viewed together, the two models should not be regarded as mutually exclusive, but rather as complementary perspectives. The Inside-Out model emphasizes the architectural innovations encoded in Asgard genomes (e.g., actin, ESCRT, and tubulin-like ESPs;

Figure 2;

Table 2), which provided the cellular scaffolding necessary for increased complexity. The E³ model, in turn, highlights the functional deployment of these features in living cells, directly linking morphology to endosymbiosis[

10].

The ecological and energetic emphases of the two models also differ in subtle but significant ways (

Table 4). The Inside-Out model stresses the long-term energetic benefits of symbiosis as a driver of complexity, consistent with theories of mitochondrial bioenergetics enabling genome expansion[

56]. By contrast, the E³ model situates the initial stages of endosymbiosis in the context of metabolic syntrophy, oxygen detoxification, and nutrient exchange between archaeal hosts and bacterial partners[

10]. This framing aligns with experimental observations of

Ca. P. syntrophicum forming cooperative associations with sulfate-reducing bacteria under microoxic conditions[

14,

46].

Taken together, these complementary models illustrate how genomic innovation, structural cell biology, and ecological interactions converged in the emergence of eukaryotes. The E³ model represents an evidence-based refinement of the Inside-Out framework, transforming abstract predictions into a mechanistic scenario supported by direct cellular observations [

10]. Importantly, both models also point toward the ecological and energetic dimensions of early symbiosis—nutrient exchange, oxygen detoxification, and the rising bioenergetic capacity conferred by mitochondria—topics that we expand upon in

Section 3.5.

This illustration synthesizes electron microscopy and cryo-EM findings of key morphological traits reported in cultured and uncultured Asgard species, including membrane invaginations, cytoskeletal-like filaments, and vesicle-like compartments (see

Figure 1). These features are interpreted considering the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model of eukaryogenesis, which proposes that protrusions from the archaeal host membrane physically enmeshed and gradually internalized symbiotic partners. This framework contrasts with earlier models that emphasized either a sudden phagocytosis-like event or a strictly metabolic syntrophy without significant morphological innovations. While the precise consensus on eukaryogenesis remains unsettled [

2], the E³ model of Imachi (2020) has gained traction as a unifying perspective that integrates both structural and ecological evidence, positioning Asgard archaea as key players [

11]. Their hypothesized syntrophic associations with methanogenic archaea (e.g.,

Methanobacteria) highlight how metabolic interdependence and morphological remodeling could have jointly set the stage for endosymbiosis.

3.5. Metabolism and Ecological Interactions

Asgard archaea are metabolically versatile, reflecting adaptations to the extreme and nutrient-limited environments they occupy, from hydrothermal vents to estuarine sediments[

29]. Genomic reconstructions and cultivation studies suggest that many lineages rely on anaerobic metabolisms, including hydrogen-dependent, acetate-based, and sulfur-associated pathways[

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. These strategies are often insufficient in isolation, which explains why Asgards frequently engage in syntrophic partnerships with co-occurring bacteria. Such metabolic interdependencies provide a plausible window into ancient microbial consortia in which cooperation, rather than competition, may have been the driving force behind evolutionary innovation.

A key example is

Ca. P. syntrophicum, which has been cultivated in stable associations with hydrogen-scavenging sulfate-reducing bacteria[

10]. In this system, the archaeon produces hydrogen as a metabolic byproduct, which is then consumed by its bacterial partner, preventing feedback inhibition and stabilizing growth[

10]. This experimentally confirmed syntrophy lends direct support to the idea that cooperative metabolic networks could have created the ecological scaffolding necessary for eukaryogenesis. It also illustrates how reciprocal nutrient exchange and detoxification—in this case, hydrogen turnover—could precede and facilitate the more complex energy-sharing relationships that later emerged with the mitochondrial endosymbiont.

These observations resonate with the E³ model, which emphasizes that early symbiosis was stabilized not by immediate energetic gains but by metabolic compatibility and ecological necessity. For instance, oxygen detoxification and the recycling of reduced compounds may have been as important as ATP yield in ensuring the survival of nascent archaeal–bacterial partnerships[

57]. Over time, however, the transition from syntrophy to endogenization fundamentally altered the energy landscape: the emerging mitochondrion not only relieved metabolic bottlenecks but also unlocked a massive increase in cellular bioenergetics, enabling larger cell sizes, expanded genomes, and complex regulatory networks (

Figure 5b)[

58].

Thus, Asgard archaea may exemplify how ecological interactions can be evolutionary catalysts. Their metabolic dependencies reinforce the notion that eukaryotic origins cannot be understood in purely genomic or structural terms but must also be framed within the ecological realities of ancient microbial ecosystems. This ecological perspective provides the necessary bridge to understanding the bioenergetic revolution that followed mitochondrial acquisition, which we discuss in

Section 3.5.

3.6. Asgard Archaea as Living Fossils

The persistence of Asgard archaea in modern extreme environments highlights their status as “living fossils.” Much like stromatolite-forming cyanobacteria that layer rock-like structures[

59,

60], Asgards preserve ancestral traits that illuminate ancient biology while continuing to evolve and adapt. Their ecological niches—including hydrothermal vents, methane seeps, and deep marine sediments—closely resemble conditions hypothesized to have prevailed on the early Earth[

61], making them powerful analog systems for reconstructing primordial life.

Importantly, not all Asgards are restricted to deep marine extremes. For instance,

Candidatus Lokiarchaeota has been recovered from brackish coastal sediments of Aarhus Bay in Denmark[

62], demonstrating that these lineages can thrive at marine–terrestrial interfaces. This brackish origin underscores their ecological flexibility and raises the possibility that transitional habitats could have played a role in facilitating symbiotic encounters with bacterial partners.

Although terrestrial detections remain rare, metagenomic surveys have reported Asgard archaea-like sequences in extreme soil environments such as hypersaline playas in western Australia, permafrost layers in northeastern Siberia, and sulfur-rich hot springs sediments in Mammoth Lakes, California, Yellowstone National Park, and in southwestern China[

29]. While these findings are less well characterized than marine counterparts, they suggest that Asgard archaea are not strictly confined to marine realms but may occasionally colonize terrestrial extremes where salinity, anoxia, or chemical stressors mirror ancient conditions.

By studying these diverse ecological settings, researchers can reconstruct not only the molecular innovations of Asgard lineages but also the environmental contexts that framed early microbial consortia. In this sense, extant Asgards provide a living window into the ecological and evolutionary dynamics that shaped the origin of eukaryotic cells.

3.7. Methodological Advances Driving Discovery

Progress in Asgard research has been inseparable from the development of new technologies. The initial discovery of Asgard archaea was made possible by metagenomic assembly, which reconstructed near-complete genomes directly from complex community datasets[

29]. This was followed by single-cell genomics, which captured strain-level diversity and revealed intra-lineage variability even in populations that resisted cultivation[

63]. More recently, long-read sequencing platforms such as PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore have allowed the assembly of repeat-rich, high-GC genomes with greater coverage and continuity[

64], enabling more robust phylogenetic inferences and improved functional annotations. Hybrid assembly approaches that integrate short- and long-read data now provide near-complete genome drafts, clarifying evolutionary relationships between Asgard archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes[

65].

On the structural side, advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) [

66] have revolutionized our understanding of Asgard cell architecture[

10]. Imaging studies have revealed dynamic membrane protrusions, vesicles, and cytoskeletal-like filaments—features that bridge the gap between prokaryotic simplicity and eukaryotic complexity[

10]. Complementary proteomic and transcriptomic profiling has begun to link genomic predictions with expressed phenotypes, offering functional validation of eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs) and uncovering condition-specific metabolic pathways[

14,

18]. Together, these tools integrate sequence-level insights with structural and functional resolution.

Despite this progress, key limitations remain. Cultivation of Asgard archaea is still rare, with only a handful of lineages successfully grown under laboratory conditions[

10]. These efforts typically require multi-year incubations and highly specific physicochemical environments, underscoring the difficulty of translating genomic predictions into experimental validation[

10]. Moreover, the current reliance on metagenomics introduces biases, including uneven community representation, incomplete genome bins, and potential contamination that complicates evolutionary interpretation[

67,

68].

Looking ahead, continued integration of multi-omics, live-cell imaging, and advanced cultivation strategies promises to transform Asgard biology from inference-based reconstruction into experimentally testable frameworks. Approaches such as single-cellstable isotope probing[

69], microfluidics-based cultivation[

70], and high-resolution live imaging [

71] could accelerate discoveries and deepen our understanding of how these elusive lineages function in situ. Ultimately, Asgard archaea stand as a model system for how technological innovation can repeatedly redraw the boundaries of the tree of life.

3.8. Syntrophy in Asgards and Beyond

Syntrophy has long been recognized as a fragile yet highly productive mode of microbial cooperation, where the metabolic success of one partner is contingent upon the removal of inhibitory intermediates by the other[

58,

72]. Manipulative partner-removal experiments across diverse bacterial and archaeal systems consistently demonstrate that when the syntrophic partner is lost, core metabolic processes collapse (

Table 5). These findings reinforce the idea that mutualistic dependencies were not accidental side effects but fundamental drivers of community structure and stability. Extending this logic to Asgard–methanogen partnerships, one can envision that the earliest steps toward eukaryogenesis similarly hinged on the stabilization of interdependent metabolisms, with the transition to organelles and nuclear complexity representing a way of internalizing and securing these obligate exchanges[

10].

Experimental studies have begun to probe the consequences of disrupting syntrophic relationships in Asgard archaea, most notably in

Ca. P. syntrophicum. When separated from hydrogen-scavenging partners such as sulfate-reducing or methanogenic bacteria, these archaea exhibit severely reduced growth or fail to survive, underscoring the obligate nature of their mutualism[

10]. This dependency reflects the classical definition of syntrophy, where metabolic waste products of one organism (e.g., hydrogen or short-chain fatty acids) are essential substrates for the partner. Such obligate interdependence not only explains the ecological stability of modern consortia but also has evolutionary implications: the metabolic fragility of the host may have provided strong selective pressure to entangle, retain, and eventually endogenize symbionts (

Figure 6). In this way, experimental manipulation of syntrophic partnerships offers a living model for testing hypotheses about how early metabolic mutualisms could have driven the transition from free-living archaea to proto-eukaryotic cells.

A rich body of microbial ecology research demonstrates that syntrophic interactions are not unique to Asgard archaea but instead represent a pervasive survival strategy across diverse microbial lineages [

78]. Classic studies of anaerobic consortia, for instance, revealed that

Syntrophomonas wolfei degrades fatty acids only in the presence of hydrogen-scavenging partners such as methanogens (

Methanospirillum hungatei), with partner removal causing complete metabolic collapse[

73]. Similarly,

Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum oxidizes propionate solely under syntrophic association, as partner elimination halts growth and forces energy-limiting redox bottlenecks[

74]. Hydrogen- and formate-mediated cross-feeding between sulfate reducers and methanogens has been dissected using isotope-labeling and chemostat approaches, further illustrating that mutualistic electron transfer can stabilize community metabolism under thermodynamic constraints[

75]. Such findings parallel the Asgard–methanogen co-cultures, underscoring that the dependence of one lineage on another is not merely facultative but a fundamental energetic principle. Taken together, this broader syntrophy literature strengthens the interpretation that early eukaryotic evolution may have been scaffolded by similarly fragile interdependencies, where removal of one partner could have prevented the emergence of stable proto-eukaryotic systems.

4. Future Studies

The study of Asgard archaea is still in its infancy. Despite remarkable progress over the past decade since their discovery, many fundamental questions remain unanswered. Future investigations will require methodological innovation, deeper integration across multi-omics platforms, and careful consideration of broader implications for evolutionary biology and astrobiology. Below, we outline key research directions with the greatest promise for advancing our understanding of these enigmatic organisms.

4.1. Expanding Cultivation Efforts

Perhaps the most pressing challenge is the limited availability of cultured strains. Current knowledge is largely derived from metagenomic reconstructions, which, while powerful, cannot fully resolve cellular physiology. The cultivation of

Ca. P. syntrophicum [

46] and

Candidatus Lokiarchaeum ossiferum [

10] demonstrated that long incubation periods and highly specific syntrophic partners (e.g., hydrogen-scavenging bacteria) are often required. Future cultivation strategies may benefit from microfluidic co-culture platforms that allow controlled interactions with bacterial partners, as well as high-throughput screening of environmental samples under varied redox conditions.

Moreover, enrichment cultures from diverse habitats—such as hypersaline brines, hydrothermal chimneys, brackish estuaries, and subsurface sediments—will expand the known diversity of Asgard archaea. Isolating new species could reveal the extent of genomic and structural heterogeneity across the superphylum, allowing researchers to test whether traits such as membrane protrusions or expanded ESP repertoires are clade-specific or universal features via common garden experiments.

4.2. Multi-Omics Integration at the Single-Cell Level

Genomics has been indispensable for identifying Asgard archaea, but understanding their biology requires integration with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics[

79]. Emerging single-cell omics technologies, including spatial transcriptomics and single-cell proteomics[

79], offer new ways to capture the dynamic states of individual Asgard cells. Such approaches could reveal how gene expression is coordinated during syntrophic interactions or stress responses.

Equally important will be the integration of lipidomics and metabolomics[

80], as archaeal membrane composition is a critical determinant of adaptation to extreme environments. Linking metabolic products to specific pathways in Asgard genomes could clarify how these organisms maintain energy balance under nutrient limitation. Ultimately, constructing a systems-level model of Asgard biology will require merging these datasets into predictive frameworks that can be experimentally tested.

4.3. Structural Biology and Cryo-Electron Tomography

The first cryo-electron tomography and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of

Ca. P. syntrophicum were transformative, revealing unexpected cellular complexity[

10] (

Figure 1). Yet many questions remain about the diversity and functional roles of Asgard cellular architectures. Future work should prioritize high-resolution imaging across multiple lineages, ideally under conditions that mimic their natural habitats.

Developing in situ cryo-EM methods that capture cells within intact microbial communities could provide unprecedented insights into syntrophic interactions. Likewise, time-resolved cryo-EM may reveal the dynamics of membrane remodeling and cytoskeletal rearrangements[

81]. By correlating structural features with transcriptomic or proteomic states, researchers can move beyond descriptive morphology toward mechanistic understanding of Asgard cell function.

4.4. Experimental Evolution and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Once a broader array of Asgard archaea are in culture, experimental evolution studies could test how these organisms adapt to new ecological pressures. For example, long-term experiments under fluctuating oxygen levels might shed light on evolutionary trajectories that facilitated the rise of aerobic metabolism in early eukaryotes.

Synthetic biology provides another promising avenue[

82]. Reconstructing Asgard ESPs in bacterial or eukaryotic model systems could test their functional roles in cytoskeletal dynamics or vesicle trafficking. Similarly, engineering synthetic consortia that replicate Asgard–bacteria syntrophy could allow controlled dissection of metabolic interdependencies. Such experimental systems may help bridge the gap between genomic potential and phenotypic reality.

4.5. Refining Models of Eukaryogenesis

Asgard archaea will no doubt continue to shape debates about the origin of eukaryotes. Future phylogenomic analyses must address unresolved questions, such as whether ESPs were inherited vertically from archaeal ancestors or acquired via lateral gene transfer. Advances in molecular clock methods and ancestral sequence reconstruction [

83] may clarify the timing of divergence events within the Asgard superphylum relative to the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA).

Another frontier is testing whether Asgard archaea represent a single lineage closely related to eukaryotes, or whether multiple lineages independently contributed genetic material to the proto-eukaryotic ancestor. Answering this question will require expanded sampling of Asgard diversity and careful reconciliation of phylogenomic data with structural and ecological evidence.

4.6. Astrobiological Applications

The study of Asgard archaea also has profound implications for the search for extraterrestrial life (

Figure 6). Their ability to thrive in anoxic, energy-limited environments makes them ideal analogs for potential life on icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus, as well as early Mars. Future studies should explore how Asgard metabolic byproducts—such as methane, acetate, or hydrogen—might serve as detectable biosignatures in planetary exploration missions[

83].

Laboratory simulations of Asgard growth under extraterrestrial conditions could guide instrument design for future missions. For example, testing whether Asgard lipids or proteins leave distinctive chemical signatures under simulated cryovolcanic or radiolytic conditions could refine biosignature detection criteria. By explicitly linking Asgard biology to astrobiology, future research can bridge evolutionary microbiology with planetary science.

A conceptual illustration linking hydrothermal vent ecosystems on Earth to putative analog environments on Mars, Europa, and Enceladus. Icons or simplified schematics represent habitats, biosignature detection methods, and connections to Asgard-like adaptations (e.g., anaerobic metabolism, extremotolerance, membrane structures). This figure emphasizes how studying Asgard archaea informs life-detection strategies.

4.7. Toward a Holistic Understanding of Asgard Archaea

Future research must integrate findings across all of these fronts—cultivation, multi-omics, structural biology, synthetic approaches, and astrobiology—into a cohesive picture. The central challenge is not only to catalog the features of Asgard archaea but also to understand how these features collectively illuminate the evolutionary processes that gave rise to eukaryotic complexity.

The next decade of Asgard research will likely yield a deeper appreciation of how ancient microbial lineages retain traces of early evolution while continuing to adapt to modern environments. As living fossils, they remind us that the story of life is not a linear progression but a branching, dynamic process, one that continues to shape both our evolutionary past and our exploration of life’s future across the universe.

5. Conclusions

Over the past decade, Asgard archaea have transformed our understanding of the microbial world and the evolutionary origins of eukaryotes[

10,

29]. Once known only from metagenomic fragments, they are now recognized as metabolically versatile, structurally complex organisms that embody transitional states between prokaryotic simplicity and eukaryotic complexity[

10]. Their unique combination of expanded ESP repertoires, dynamic cell architectures, and syntrophic lifestyles has provided a living window into the processes that set the stage for eukaryogenesis[

14,

18].

Nevertheless, many uncertainties remain. The true diversity of the Asgard superphylum is likely only beginning to be uncovered, and the ecological contexts that shaped their evolution are still poorly constrained. Cultivation, multi-omics integration, structural biology, and synthetic biology approaches will be necessary to move from descriptive to mechanistic models. At the same time, Asgard archaea remind us that life’s deepest evolutionary transitions are best understood when genomic, ecological, and structural perspectives are considered together.

Ultimately, the study of Asgard archaea highlights the power of interdisciplinary science. By uniting evolutionary biology, microbiology, biophysics, and astrobiology, researchers can not only reconstruct the path to eukaryotes on Earth but also refine our search for life elsewhere in the universe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and original draft, D.M.R. Writing, review, and editing, G.R.H. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers UG3OD023285, P42ES030991, and P30ES036084.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used ChatGPT5 for the purposes of increasing the clarity of the text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. We thank Dr. Hiroyuki Imachi for the SEM images in Figure 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| POLET |

Precursors to the origin of life exist today |

| PPK |

Pre-prokaryrotes |

| ESP |

Eukaryotic Signature Proteins |

| E3

|

Entangle-Engulf-Endogenize |

| ESCRT |

Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport |

| LECA |

Last Eukaryotic Common Ancestor |

| LUCA |

Last Universal Common Ancestor |

| OOL |

Origin of Life |

| ULP |

Unknown linear polymers |

| TACK |

Thaumarchaeota, Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota, Korarchaeota |

| DPANN |

Diapherotrites, Parvarchaeota, Aenigmarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, Nanohaloarchaeota |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| Ca. P. syntrophicum |

Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum |

References

- Moody ERR, Alvarez-Carretero S, Mahendrarajah TA, Clark JW, Betts HC, Dombrowski N, et al. The nature of the last universal common ancestor and its impact on the early Earth system. Nat Ecol Evol. 2024;8(9):1654-66.

- Fournier GP, Poole AM. A Briefly Argued Case That Asgard Archaea Are Part of the Eukaryote Tree. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1896.

- Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Caceres EF, Saw JH, Backstrom D, Juzokaite L, Vancaester E, et al. Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature. 2017;541(7637):353-8.

- Leao P, Little ME, Appler KE, Sahaya D, Aguilar-Pine E, Currie K, et al. Asgard archaea defense systems and their roles in the origin of eukaryotic immunity. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6386.

- Woese CR, Fox GE. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74(11):5088-90.

- Cox CJ, Foster PG, Hirt RP, Harris SR, Embley TM. The archaebacterial origin of eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(51):20356-61.

- Albers S, Ashmore J, Pollard T, Spang A, Zhou J. Origin of eukaryotes: What can be learned from the first successfully isolated Asgard archaeon. Fac Rev. 2022;11:3.

- Williams TA, Cox CJ, Foster PG, Szollosi GJ, Embley TM. Phylogenomics provides robust support for a two-domains tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol. 2020;4(1):138-47.

- Zhou Z, Liu Y, Li M, Gu JD. Two or three domains: a new view of tree of life in the genomics era. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(7):3049-58.

- Imachi H, Nobu MK, Nakahara N, Morono Y, Ogawara M, Takaki Y, et al. Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote-eukaryote interface. Nature. 2020;577(7791):519-25.

- Imachi H, Nobu MK, Nakahara N, Morono Y, Ogawara M, Takaki Y, et al. Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote-eukaryote interface. Nature. 2020;577(7791):519-25.

- Hager K, Luo ZH, Montserrat-Diez M, Ponce-Toledo RI, Baur P, Dahlke S, et al. Diversity and environmental distribution of Asgard archaea in shallow saline sediments. Front Microbiol. 2025;16:1549128.

- Weber JM, Marlin TC, Prakash M, Teece BL, Dzurilla K, Barge LM. A Review on Hypothesized Metabolic Pathways on Europa and Enceladus: Space-Flight Detection Considerations. Life (Basel). 2023;13(8).

- Da Cunha V, Gaia M, Forterre P. The expanding Asgard archaea and their elusive relationships with Eukarya. mLife. 2022;1(1):3-12.

- Spang A, Saw JH, Jorgensen SL, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Martijn J, Lind AE, et al. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature. 2015;521(7551):173-9.

- Devos, DP. Reconciling Asgardarchaeota Phylogenetic Proximity to Eukaryotes and Planctomycetes Cellular Features in the Evolution of Life. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(9):3531-42.

- Valentin-Alvarado LE, Shi LD, Appler KE, Crits-Christoph A, De Anda V, Adler BA, et al. Complete genomes of Asgard archaea reveal diverse integrated and mobile genetic elements. Genome Res. 2024;34(10):1595-609.

- Rodrigues-Oliveira T, Wollweber F, Ponce-Toledo RI, Xu J, Rittmann SKR, Klingl A, et al. Actin cytoskeleton and complex cell architecture in an Asgard archaeon. Nature. 2023;613(7943):332-9.

- Eme L, Tamarit D, Caceres EF, Stairs CW, De Anda V, Schon ME, et al. Inference and reconstruction of the heimdallarchaeial ancestry of eukaryotes. Nature. 2023;618(7967):992-9.

- Gilbert JA, Hughes M. Gene expression profiling: metatranscriptomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;733:195-205.

- Valentin-Alvarado LE, Appler KE, De Anda V, Schoelmerich MC, West-Roberts J, Kivenson V, et al. Asgard archaea modulate potential methanogenesis substrates in wetland soil. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6384.

- Vigneron A, Vincent WF, Lovejoy C. Discovery of a novel bacterial class with the capacity to drive sulfur cycling and microbiome structure in a paleo-ocean analog. ISME Commun. 2023;3(1):82.

- Xamxidin M, Zhang X, Zheng G, Chen C, Wu M. Metagenomics-assembled genomes reveal microbial metabolic adaptation to athalassohaline environment, the case Lake Barkol, China. Front Microbiol. 2025;16:1550346.

- Pan X, Zhao L, Li C, Angelidaki I, Lv N, Ning J, et al. Deep insights into the network of acetate metabolism in anaerobic digestion: focusing on syntrophic acetate oxidation and homoacetogenesis. Water Res. 2021;190:116774.

- Wiechmann A, Ciurus S, Oswald F, Seiler VN, Muller V. It does not always take two to tango: "Syntrophy" via hydrogen cycling in one bacterial cell. ISME J. 2020;14(6):1561-70.

- Matheus Carnevali PB, Schulz F, Castelle CJ, Kantor RS, Shih PM, Sharon I, et al. Author Correction: Hydrogen-based metabolism as an ancestral trait in lineages sibling to the Cyanobacteria. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1451.

- Matheus Carnevali PB, Schulz F, Castelle CJ, Kantor RS, Shih PM, Sharon I, et al. Hydrogen-based metabolism as an ancestral trait in lineages sibling to the Cyanobacteria. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):463.

- Liu Y, Makarova KS, Huang WC, Wolf YI, Nikolskaya AN, Zhang X, et al. Expanded diversity of Asgard archaea and their relationships with eukaryotes. Nature. 2021;593(7860):553-7.

- MacLeod F, Kindler GS, Wong HL, Chen R, Burns BP. Asgard archaea: Diversity, function, and evolutionary implications in a range of microbiomes. AIMS Microbiol. 2019;5(1):48-61.

- Lopez-Garcia P, Moreira D. The Syntrophy hypothesis for the origin of eukaryotes revisited. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(5):655-67.

- Survery S, Hurtig F, Haq SR, Eriksson J, Guy L, Rosengren KJ, et al. Heimdallarchaea encodes profilin with eukaryotic-like actin regulation and polyproline binding. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):1024.

- Zhou Z, Liu Y, Anantharaman K, Li M. The expanding Asgard archaea invoke novel insights into Tree of Life and eukaryogenesis. mLife. 2022;1(4):374-81.

- Lu Z, Zhang S, Liu Y, Xia R, Li M. Origin of eukaryotic-like Vps23 shapes an ancient functional interplay between ESCRT and ubiquitin system in Asgard archaea. Cell Rep. 2024;43(2):113781.

- Tran LT, Akil C, Senju Y, Robinson RC. The eukaryotic-like characteristics of small GTPase, roadblock and TRAPPC3 proteins from Asgard archaea. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):273.

- Akil C, Ali S, Tran LT, Gaillard J, Li W, Hayashida K, et al. Structure and dynamics of Odinarchaeota tubulin and the implications for eukaryotic microtubule evolution. Sci Adv. 2022;8(12):eabm2225.

- Mahendrarajah TA, Spang A. DPANN Archaea and CPR Bacteria: insights into early cellular evolution? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2025;380(1931):20240096.

- Zhang IH, Borer B, Zhao R, Wilbert S, Newman DK, Babbin AR. Uncultivated DPANN archaea are ubiquitous inhabitants of global oxygen-deficient zones with diverse metabolic potential. mBio. 2024;15(3):e0291823.

- Souza DP, Espadas J, Chaaban S, Moody ERR, Hatano T, Balasubramanian M, et al. Asgard archaea reveal the conserved principles of ESCRT-III membrane remodeling. Sci Adv. 2025;11(6):eads5255.

- Williams TA, Low HH. The evolution and mechanism of bacterial and archaeal ESCRT-III-like systems. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2025;93:103111.

- Spang A, Eme L, Saw JH, Caceres EF, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Lombard J, et al. Asgard archaea are the closest prokaryotic relatives of eukaryotes. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(3):e1007080.

- Zhang J, Feng X, Li M, Liu Y, Liu M, Hou LJ, et al. Deep origin of eukaryotes outside Heimdallarchaeia within Asgardarchaeota. Nature. 2025;642(8069):990-8.

- Schopf, JW. Geological evidence of oxygenic photosynthesis and the biotic response to the 2400-2200 ma "great oxidation event". Biochemistry (Mosc). 2014;79(3):165-77.

- Sessions AL, Doughty DM, Welander PV, Summons RE, Newman DK. The continuing puzzle of the great oxidation event. Curr Biol. 2009;19(14):R567-74.

- Martin W, Muller M. The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote. Nature. 1998;392(6671):37-41.

- Avci B, Panagiotou K, Albertsen M, Ettema TJG, Schramm A, Kjeldsen KU. Peculiar morphology of Asgard archaeal cells close to the prokaryote-eukaryote boundary. mBio. 2025;16(5):e0032725.

- Lopez-Garcia P, Moreira D. Cultured Asgard Archaea Shed Light on Eukaryogenesis. Cell. 2020;181(2):232-5.

- Dey G, Thattai M, Baum B. On the Archaeal Origins of Eukaryotes and the Challenges of Inferring Phenotype from Genotype. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(7):476-85.

- Manoharan L, Kozlowski JA, Murdoch RW, Lof fl er FE, Sousa FL, Schleper C. Erratum for Manoharan et al., "Metagenomes from Coastal Marine Sediments Give Insights into the Ecological Role and Cellular Features of Loki- and Thorarchaeota". mBio. 2019;10(5).

- Manoharan L, Kozlowski JA, Murdoch RW, Loffler FE, Sousa FL, Schleper C. Metagenomes from Coastal Marine Sediments Give Insights into the Ecological Role and Cellular Features of Loki- and Thorarchaeota. mBio. 2019;10(5).

- Tamarit D, Caceres EF, Krupovic M, Nijland R, Eme L, Robinson NP, et al. A closed Candidatus Odinarchaeum chromosome exposes Asgard archaeal viruses. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7(7):948-52.

- Wu F, Speth DR, Philosof A, Cremiere A, Narayanan A, Barco RA, et al. Unique mobile elements and scalable gene flow at the prokaryote-eukaryote boundary revealed by circularized Asgard archaea genomes. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7(2):200-12.

- Eme L, Tamarit D, Caceres EF, Stairs CW, De Anda V, Schon ME, et al. Inference and reconstruction of the heimdallarchaeial ancestry of eukaryotes. Nature. 2023;618(7967):992-9.

- Sorokin DY, Makarova KS, Abbas B, Ferrer M, Golyshin PN, Galinski EA, et al. Discovery of extremely halophilic, methyl-reducing euryarchaea provides insights into the evolutionary origin of methanogenesis. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17081.

- Bueno de Mesquita CP, Zhou J, Theroux SM, Tringe SG. Methanogenesis and Salt Tolerance Genes of a Novel Halophilic Methanosarcinaceae Metagenome-Assembled Genome from a Former Solar Saltern. Genes (Basel). 2021;12(10).

- Baum DA, Baum B. An inside-out origin for the eukaryotic cell. BMC Biol. 2014;12:76.

- Lane N, Martin W. The energetics of genome complexity. Nature. 2010;467(7318):929-34.

- Thorgersen MP, Stirrett K, Scott RA, Adams MW. Mechanism of oxygen detoxification by the surprisingly oxygen-tolerant hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(45):18547-52.

- Libby E, Hebert-Dufresne L, Hosseini SR, Wagner A. Syntrophy emerges spontaneously in complex metabolic systems. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15(7):e1007169.

- Gerard E, De Goeyse S, Hugoni M, Agogue H, Richard L, Milesi V, et al. Key Role of Alphaproteobacteria and Cyanobacteria in the Formation of Stromatolites of Lake Dziani Dzaha (Mayotte, Western Indian Ocean). Front Microbiol. 2018;9:796.

- Kremer B, Kazmierczak J, Lukomska-Kowalczyk M, Kempe S. Calcification and silicification: fossilization potential of cyanobacteria from stromatolites of Niuafo'ou's Caldera Lakes (Tonga) and implications for the early fossil record. Astrobiology. 2012;12(6):535-48.

- Lunine, JI. Physical conditions on the early Earth. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1474):1721-31.

- Avci B, Brandt J, Nachmias D, Elia N, Albertsen M, Ettema TJG, et al. Spatial separation of ribosomes and DNA in Asgard archaeal cells. ISME J. 2022;16(2):606-10.

- Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Wolf YI. Evolution of Microbial Genomics: Conceptual Shifts over a Quarter Century. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29(7):582-92.

- Logsdon GA, Vollger MR, Eichler EE. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21(10):597-614.

- Bouras G, Houtak G, Wick RR, Mallawaarachchi V, Roach MJ, Papudeshi B, et al. Hybracter: enabling scalable, automated, complete and accurate bacterial genome assemblies. Microb Genom. 2024;10(5).

- Baumeister, W. Cryo-electron tomography: A long journey to the inner space of cells. Cell. 2022;185(15):2649-52.

- Lapidus AL, Korobeynikov AI. Metagenomic Data Assembly - The Way of Decoding Unknown Microorganisms. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:613791.

- Zhang Z, Yang C, Veldsman WP, Fang X, Zhang L. Benchmarking genome assembly methods on metagenomic sequencing data. Brief Bioinform. 2023;24(2).

- Alcolombri U, Pioli R, Stocker R, Berry D. Single-cell stable isotope probing in microbial ecology. ISME Commun. 2022;2(1):55.

- Jiang MZ, Zhu HZ, Zhou N, Liu C, Jiang CY, Wang Y, et al. Droplet microfluidics-based high-throughput bacterial cultivation for validation of taxon pairs in microbial co-occurrence networks. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):18145.

- Bourges AC, Lazarev A, Declerck N, Rogers KL, Royer CA. Quantitative High-Resolution Imaging of Live Microbial Cells at High Hydrostatic Pressure. Biophys J. 2020;118(11):2670-9.

- Morris BE, Henneberger R, Huber H, Moissl-Eichinger C. Microbial syntrophy: interaction for the common good. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37(3):384-406.

- McInerney MJ, Bryant MP, Hespell RB, Costerton JW. Syntrophomonas wolfei gen. nov. sp. nov., an Anaerobic, Syntrophic, Fatty Acid-Oxidizing Bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41(4):1029-39.

- Imachi H, Sekiguchi Y, Kamagata Y, Hanada S, Ohashi A, Harada H. Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic, thermophilic, syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52(Pt 5):1729-35.

- Stams AJ, Plugge CM. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(8):568-77.

- Rotaru AE, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Markovaite B, Chen S, Nevin KP, et al. Direct interspecies electron transfer between Geobacter metallireducens and Methanosarcina barkeri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(15):4599-605.

- Westerholm M, Calusinska M, Dolfing J. Syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria in methanogenic systems. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2022;46(2).

- Javaux, EJ. A diverse Palaeoproterozoic microbial ecosystem implies early eukaryogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2025;380(1931):20240092.

- Sanches PHG, de Melo NC, Porcari AM, de Carvalho LM. Integrating Molecular Perspectives: Strategies for Comprehensive Multi-Omics Integrative Data Analysis and Machine Learning Applications in Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Metabolomics. Biology (Basel). 2024;13(11).

- Wang R, Li B, Lam SM, Shui G. Integration of lipidomics and metabolomics for in-depth understanding of cellular mechanism and disease progression. J Genet Genomics. 2020;47(2):69-83.

- Yoniles J, Summers JA, Zielinski KA, Antolini C, Panjalingam M, Lisova S, et al. Time-resolved cryogenic electron tomography for the study of transient cellular processes. Mol Biol Cell. 2024;35(7):mr4.

- Kiattisewee, C. How many plasmids can bacteria carry? A synthetic biology perspective. Open Biol. 2025;15(7):240378.

- Prakinee K, Phaisan S, Kongjaroon S, Chaiyen P. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction for Designing Biocatalysts and Investigating their Functional Mechanisms. JACS Au. 2024;4(12):4571-91.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of Asgard archaea. Representative SEM images of

Ca. P. syntrophicum strain MK-D1, the first cultivated member of the Asgard archaea. (a) Cells displaying long, branching membrane protrusions that extend outward into the extracellular space. (b) Cells exhibiting straighter, filament-like protrusions. White arrows indicate large vesicle-like structures observed at the cell surface. These morphological features are interpreted as possible mechanisms for mediating close cell–cell interactions, consistent with syntrophic lifestyles in which MK-D1 exchanges hydrogen and other metabolites with bacterial partners. Such protrusions and vesicles have also been hypothesized to play roles in the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model of eukaryogenesis, where they may have facilitated physical association and eventual engulfment of symbiotic partners such as the alphaproteobacterial ancestor of mitochondria. Scale bars = 1 μm. Images provided by Dr. Hiroyuki Imachi [

11].

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of Asgard archaea. Representative SEM images of

Ca. P. syntrophicum strain MK-D1, the first cultivated member of the Asgard archaea. (a) Cells displaying long, branching membrane protrusions that extend outward into the extracellular space. (b) Cells exhibiting straighter, filament-like protrusions. White arrows indicate large vesicle-like structures observed at the cell surface. These morphological features are interpreted as possible mechanisms for mediating close cell–cell interactions, consistent with syntrophic lifestyles in which MK-D1 exchanges hydrogen and other metabolites with bacterial partners. Such protrusions and vesicles have also been hypothesized to play roles in the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model of eukaryogenesis, where they may have facilitated physical association and eventual engulfment of symbiotic partners such as the alphaproteobacterial ancestor of mitochondria. Scale bars = 1 μm. Images provided by Dr. Hiroyuki Imachi [

11].

Figure 2.

Proposed eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs) encoded in Asgard archaeal genomes. (a) A schematic diagram showing functional categories of ESPs identified by metagenomics and comparative genomics (e.g., actin homologs, ESCRT proteins, small GTPases). Indicated are pathways of potential interaction between these proteins and cellular structures, underscoring molecular parallels between Asgard archaea and eukaryotic cellular organization. (b) A clustered heatmap summarizing the distribution of the number of major ESP categories (ranging from 1 to 20) across representative Asgard phyla. Columns correspond to ESP functional groups (e.g., cytoskeletal, membrane remodeling, informational processing), while rows represent Asgard lineages. Hierarchical clustering highlights evolutionary affinities, with Heimdallarchaeota enriched for informational and cytoskeletal ESPs, and Thor- and Loki-archaeota showing intermediate repertoires. This comparative framework illustrates lineage-specific mosaics of ESPs that collectively illuminate different aspects of early eukaryogenesis.

Figure 2.

Proposed eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs) encoded in Asgard archaeal genomes. (a) A schematic diagram showing functional categories of ESPs identified by metagenomics and comparative genomics (e.g., actin homologs, ESCRT proteins, small GTPases). Indicated are pathways of potential interaction between these proteins and cellular structures, underscoring molecular parallels between Asgard archaea and eukaryotic cellular organization. (b) A clustered heatmap summarizing the distribution of the number of major ESP categories (ranging from 1 to 20) across representative Asgard phyla. Columns correspond to ESP functional groups (e.g., cytoskeletal, membrane remodeling, informational processing), while rows represent Asgard lineages. Hierarchical clustering highlights evolutionary affinities, with Heimdallarchaeota enriched for informational and cytoskeletal ESPs, and Thor- and Loki-archaeota showing intermediate repertoires. This comparative framework illustrates lineage-specific mosaics of ESPs that collectively illuminate different aspects of early eukaryogenesis.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic placement of Asgard archaea within the archaeal domain. A schematic phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary placement of Asgard archaea relative to other archaeal superphyla and eukaryotes. Major archaeal lineages are shown, including TACK (

Thaumarchaeota,

Aigarchaeota,

Crenarchaeota,

Korarchaeota), DPANN (

Diapherotrites, Parvarchaeota, Aenigmarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, Nanohaloarchaeota), Euryarchaeota, and the Asgard clade (blue), with branches for

Lokiarchaeota (Loki),

Thorarchaeota (Thor),

Odinarchaeota (Odin), and

Heimdallarchaeota (Heimdall). The

Eukaryota branch (red) emerges closest to

Heimdallarchaeota, consistent with prior phylogenomic consensus, with the red triangle marking the inferred split between Asgards and eukaryotes. The bacterial root (Bacteria) is included for reference, and bootstrap or posterior probability values from representative studies are shown at key nodes. The horizontal bar represents ~100 million years of evolutionary divergence. Recent large-scale phylogenomic analyses of over 200 archaeal genomes by Zhang and colleagues (2025) revise this placement, suggesting that eukaryotes arose before the diversification of all sampled

Heimdallarchaeia, (black triangles), rather than specifically with

Hodarchaeales (red triangle) [

14]. This reinterpretation is attributed to the previously underappreciated chimeric nature of

Njordarchaeales genomes, which harbor a mosaic of sequences from both Asgard archaea and the TACK superphylum [

41].

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic placement of Asgard archaea within the archaeal domain. A schematic phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary placement of Asgard archaea relative to other archaeal superphyla and eukaryotes. Major archaeal lineages are shown, including TACK (

Thaumarchaeota,

Aigarchaeota,

Crenarchaeota,

Korarchaeota), DPANN (

Diapherotrites, Parvarchaeota, Aenigmarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, Nanohaloarchaeota), Euryarchaeota, and the Asgard clade (blue), with branches for

Lokiarchaeota (Loki),

Thorarchaeota (Thor),

Odinarchaeota (Odin), and

Heimdallarchaeota (Heimdall). The

Eukaryota branch (red) emerges closest to

Heimdallarchaeota, consistent with prior phylogenomic consensus, with the red triangle marking the inferred split between Asgards and eukaryotes. The bacterial root (Bacteria) is included for reference, and bootstrap or posterior probability values from representative studies are shown at key nodes. The horizontal bar represents ~100 million years of evolutionary divergence. Recent large-scale phylogenomic analyses of over 200 archaeal genomes by Zhang and colleagues (2025) revise this placement, suggesting that eukaryotes arose before the diversification of all sampled

Heimdallarchaeia, (black triangles), rather than specifically with

Hodarchaeales (red triangle) [

14]. This reinterpretation is attributed to the previously underappreciated chimeric nature of

Njordarchaeales genomes, which harbor a mosaic of sequences from both Asgard archaea and the TACK superphylum [

41].

Figure 4.

Representative cellular ultrastructure of Asgard archaea within the context of the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model.

Figure 4.

Representative cellular ultrastructure of Asgard archaea within the context of the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model.

Figure 5.

Morphological and metabolic foundations of the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model of eukaryogenesis. (a) Parallel application of the E³ framework to mitochondrial endosymbiosis and nuclear envelope evolution. On the left, long, branching protrusions of an ancestral Asgard archaeon enmesh and gradually engulf an alphaproteobacterial partner, leading to the emergence of mitochondria. On the right, similar protrusion-driven processes are hypothesized to generate internal membrane invaginations that evolved into the nuclear envelope, partitioning genomic DNA from the cytoplasm. (b) Metabolic interactions of Ca. P. syntrophicum, which engages in syntrophic partnerships with hydrogen-scavenging bacteria. The archaeon produces hydrogen and other metabolites that are consumed by bacterial associates, stabilizing the consortium in nutrient-limited environments. The long protrusions facilitate intimate contact and metabolic exchange, providing ecological support for the E³ process and illustrating how syntrophy may have laid the groundwork for organelle acquisition and eukaryotic complexity.

Figure 5.

Morphological and metabolic foundations of the entangle–engulf–endogenize (E³) model of eukaryogenesis. (a) Parallel application of the E³ framework to mitochondrial endosymbiosis and nuclear envelope evolution. On the left, long, branching protrusions of an ancestral Asgard archaeon enmesh and gradually engulf an alphaproteobacterial partner, leading to the emergence of mitochondria. On the right, similar protrusion-driven processes are hypothesized to generate internal membrane invaginations that evolved into the nuclear envelope, partitioning genomic DNA from the cytoplasm. (b) Metabolic interactions of Ca. P. syntrophicum, which engages in syntrophic partnerships with hydrogen-scavenging bacteria. The archaeon produces hydrogen and other metabolites that are consumed by bacterial associates, stabilizing the consortium in nutrient-limited environments. The long protrusions facilitate intimate contact and metabolic exchange, providing ecological support for the E³ process and illustrating how syntrophy may have laid the groundwork for organelle acquisition and eukaryotic complexity.

Figure 6.

Astrobiological implications of Asgard archaea research.

Figure 6.

Astrobiological implications of Asgard archaea research.

Table 1.

Comparative-omics, structural, ecological and methodological approaches for studying Asgard archaea. Results from these studies represented here are summarized throughout the review.

Table 1.

Comparative-omics, structural, ecological and methodological approaches for studying Asgard archaea. Results from these studies represented here are summarized throughout the review.

| Approach |

Application to Asgard Archaea |

Key Insights Gained |

Representative Studies |

| Metagenomics |

Reconstruction of genomes from environmental samples; discovery of Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, Heimdallarchaeota

|

Identification of ESPs (eukaryotic signature proteins); phylogenetic placement bridging archaea and eukaryotes. |

[3,15,16,17,18,19] |

| Metatranscriptomics |

Gene expression profiling in ecological (environmental) contexts |

Evidence for active transcription of ESPs; insights into ecological roles and metabolic activity. |

[10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] |

| Proteomics |

Mass spectrometry-based analysis of proteins in enriched cultures or environmental samples |

Detection of ESPs at protein level; functional insights into cytoskeletal and membrane-trafficking proteins. |

[18,28] |

| Metabolomics |

Profiling of small-molecule metabolites in co-cultures or natural settings |

Understanding of energy metabolism (anaerobic vs. microaerobic processes); adaptation to extreme niches. |

[29,30] |

| Cryo-EM & Microscopy |

Structural imaging of Asgard cells and ESP assemblies |

Visualization of tubulin-like filaments and actin-like structures; evidence of internal complexity. |

[10,18] |

| Cultivation & Co-culture |

Growth of Asgard archaea with bacterial partners under laboratory conditions. |

Direct testing of physiology; confirmation of syntrophic relationships. |

[11,28] |

Table 2.

Distribution of ESPs across Asgard lineages and other archaeal groups.

Table 2.

Distribution of ESPs across Asgard lineages and other archaeal groups.