Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Transition Metal Hexacyanometallates (Prussian Blue Analogs)

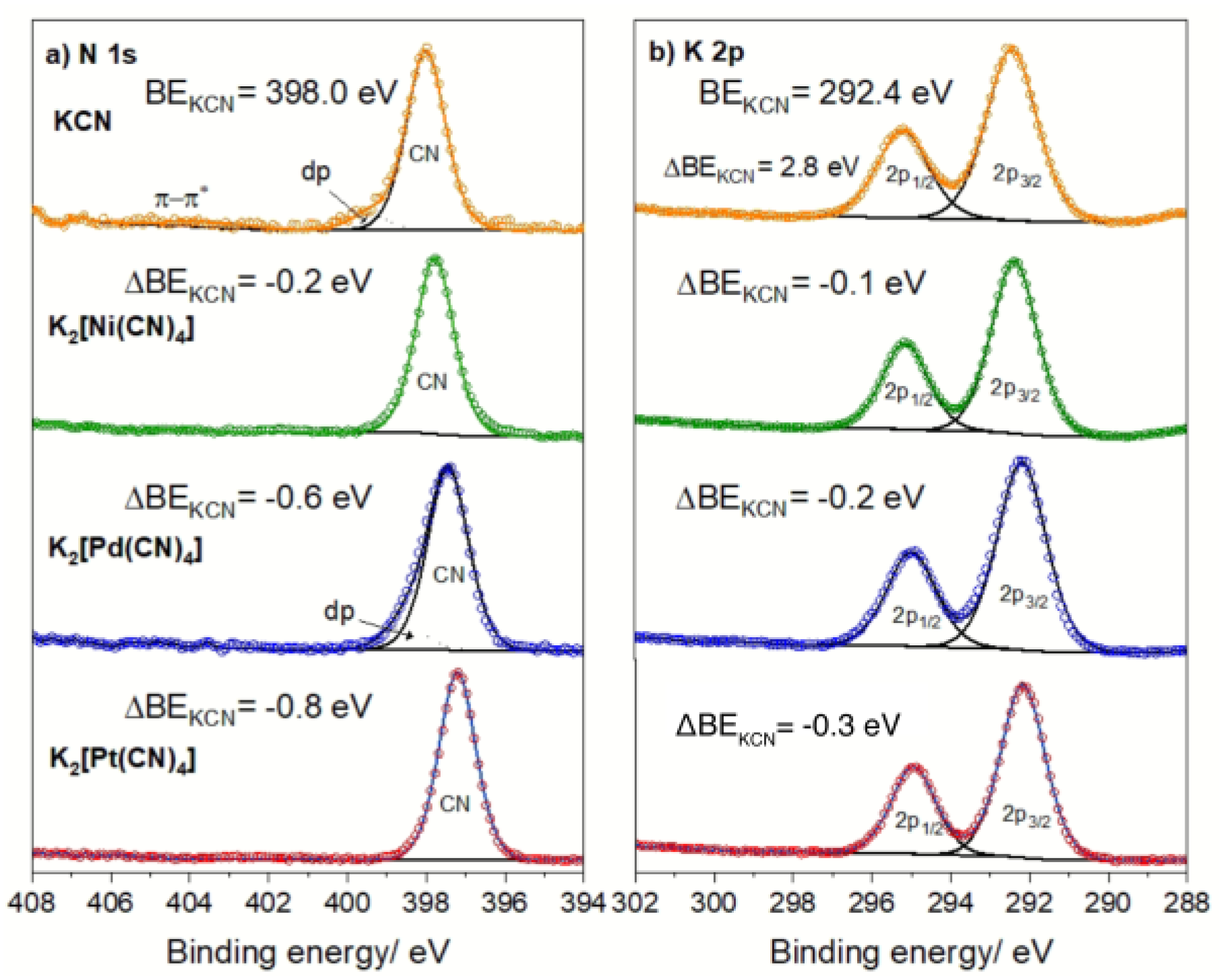

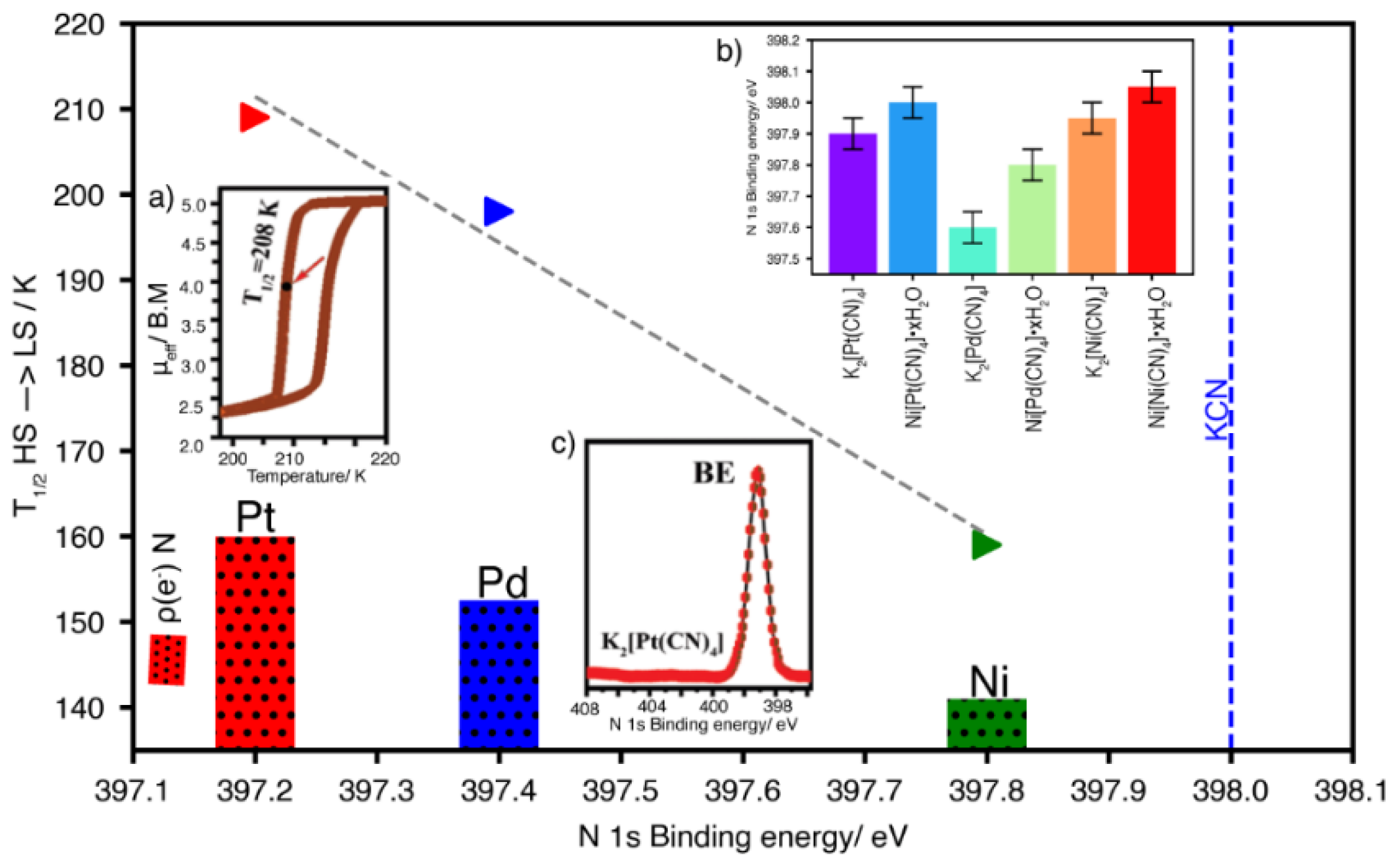

2.1. Transition Metal Tetracyanometallates (Hofmann-Like Coordination Polymers)

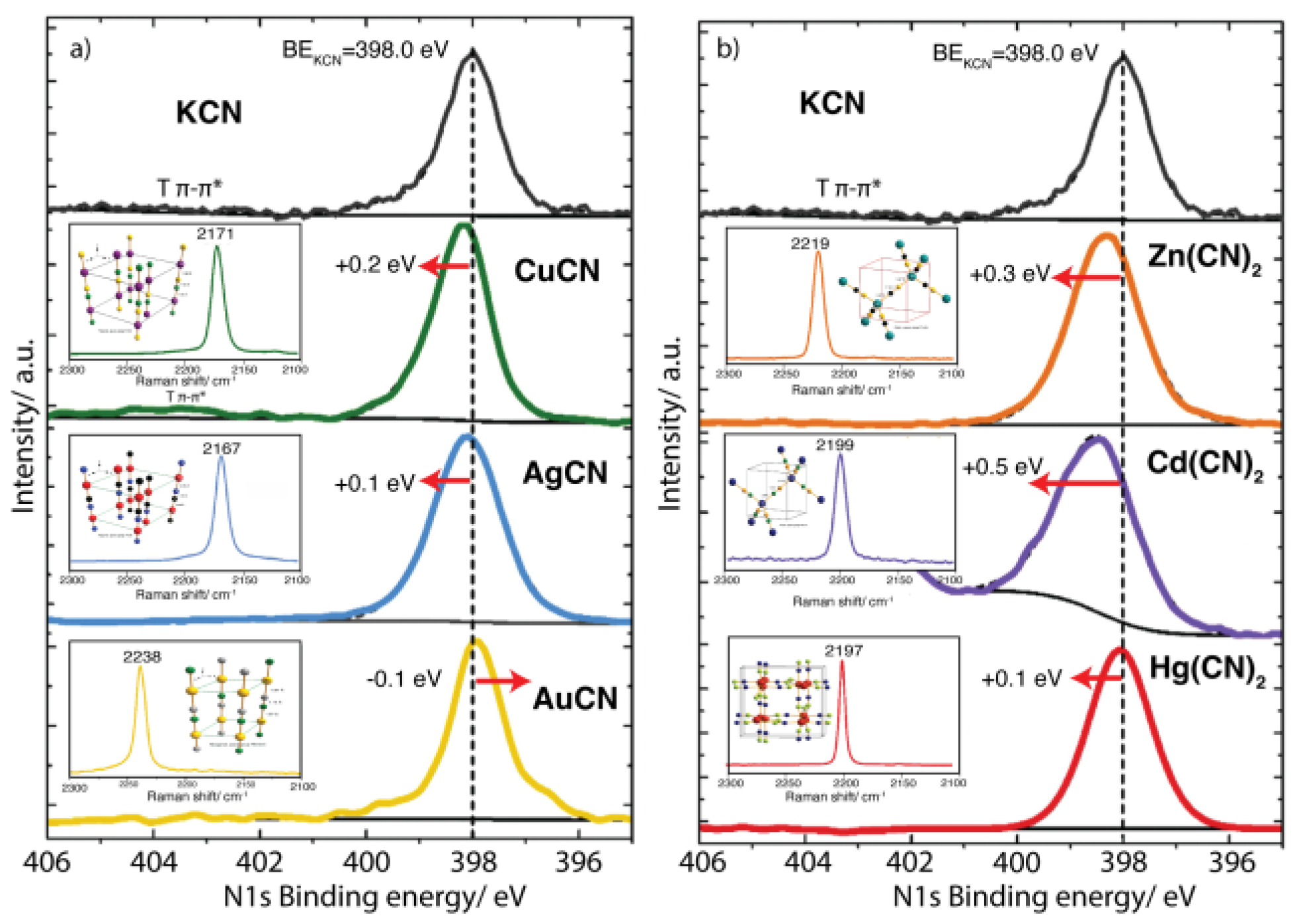

3. nd10 Metal Cyanides.

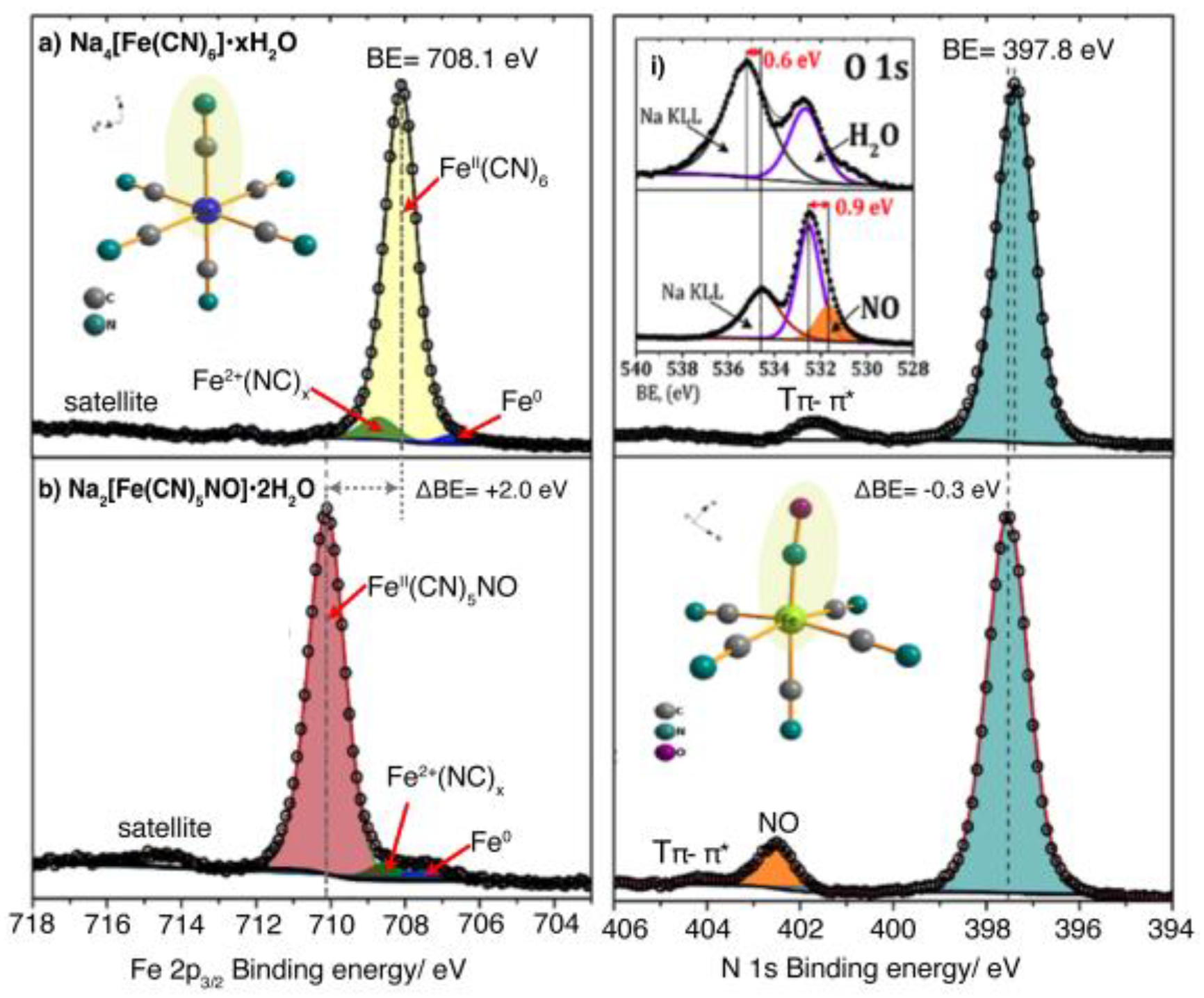

4. Transition Metal Nitroprussides

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| PBAs | Prussian blue analogs (PBAs) |

| KE | Kinetic energy |

| BE | Binding energy |

| Tc | Critical temperature |

| HS | High spin |

| LS | Low spin |

| SCO | Spin Crossover |

References

- Watts, J.F.; Wolstenholme, J. An Introduction to Surface Analysis by XPS and AES; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide, P. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy—An Introduction to Principles and Practices; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Avila, Y.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Reguera, L.; Reguera, E. Recent progress in transition metal hexacyanometallates: From structure to properties and functionality. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, K.R.; Heintz, R.A. Chemistry of Transition Metal Cyanide Compounds: Modern Perspectives. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 45, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, A.G. The Chemistry of Cyano Complexes of the Transition Metals; Academic; Academic Press: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, R.D. Structure and Bonding in Copper(I) Carbonyl and Cyanide Complexes. Organometallics 2012, 31, 7647–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, S.; Mallah, T.; Ouahès, R.; Veillet, P.; Verdaguer, M. A room-temperature organometallic magnet based on Prussian blue. Nature 1995, 378, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

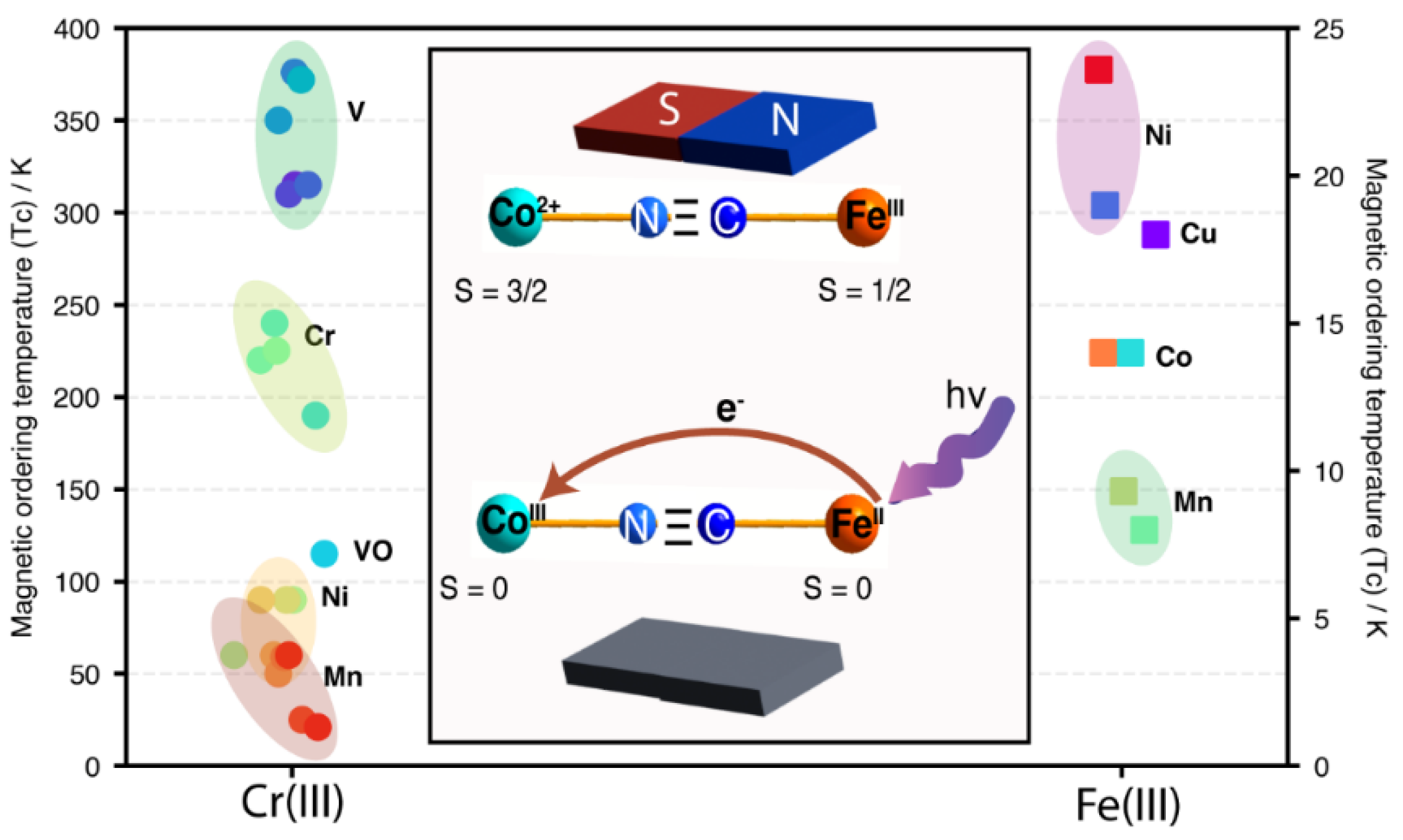

- Sato, O.; Iyoda, T.; Fujishima, A.; Hashimoto, K. Photoinduced Magnetization of a Cobalt-Iron Cyanide. Science 1996, 272, 704–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannerberg, N.G. The ESCA-spectra of sodium and potassium cyanide and of the sodium and potassium salts of the hexacyanometallates of the first transition metal series. Chem. Scr. 1976, 9, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fluck, E.; Inoue, H.; Yanagisawa, S. Mössbauer and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of prussian blue and its related compounds. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1977, 430, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluck, E.; Inoue, H.; Nagao, M.; Yanagisawa, S. Bonding properties in Prussian blue analogues of the type Fe[Fe(CN)5X]·xH2O. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1979, 41, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, I.; Thomas, J.M.; Bancroft, G.M.; Butler, K.D.; Barber, M. Correlation between core-electron binding energies and Mössbauer chemical isomer shifts for inorganic complexes containing iron(II) low spin. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1972, 751–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, G.K.; Rosencwaig, A. Characterization of Inequivalent Iron Sites in Prussian Blue by Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 3235–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, A. X-ray spectroscopy of the valence band in simple and complex cyanides. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1973, 23, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oku, M. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies on the kinetics of photoreduction of Fe III in single-crystal K3(Fe,Co)(CN)6 surfaces cleaved in situ. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1993, 89, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lummen, T.T.A.; Gengler, R.Y.N.; Rudolf, P.; Lusitani, F.; Vertelman, E.J.M.; van Koningsbruggen, P.J.; Knupfer, M.; Molodtsova, O.; Pireaux, J.-J.; van Loosdrecht, P.H.M. Bulk and Surface Switching in Mn−Fe-Based Prussian Blue Analogues. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 14158–14167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, S.J.; Erasmus, E. Electronic effects of metal hexacyanoferrates: An XPS and FTIR study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 203, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Shchukarev, A.; Reguera, E. Intercalation of pyrazine in layered copper nitroprusside: Synthesis, crystal structure and XPS study. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 273, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, L.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Reguera, E. On the Scope of XPS as Sensor in Coordination Chemistry of Transition Metal Hexacyanometallates. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1724–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Monroy, I.; Ávila, M.; Velasco-Arias, D.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E. Relevant electronic interactions related to the coordination chemistry of tetracyanometallates. An XPS study. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 18384–18393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Avila, Y.; Avila, M.; Reguera, E. Structural information contained in the XPS spectra of nd10 metal cyanides. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 276, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Lartundo-Rojas, L.; Shchukarev, A.; Reguera, E. Contribution to the coordination chemistry of transition metal nitroprussides: a cryo-XPS study. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 4835–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Reguera, L.; Avila, M.; Velasco-Arias, D.; Reguera, E. Charge Redistribution Effects in Hexacyanometallates Evaluated from XPS Data. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2020, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E.; Lima, E.; Balmaseda, J.; Martínez-García, R.; Yee-Madeira, H. An atypical coordination in hexacyanometallates: Structure and properties of hexagonal zinc phases. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2007, 68, 1630–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Lemus-Santana, A.; Vargas, C.; Reguera, E. Three structural modifications in the series of layered solids T(H2O)2[Ni(CN)4]·xH2O with T = Mn, Co, Ni: Their nature and crystal structures. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2011, 15, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.; Lemus-Santana, A.A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Knobel, M.; Reguera, E. π–π Interactions and magnetic properties in a series of hybrid inorganic–organic crystals. J. Solid State Chem. 2013, 197, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus-Santana, A.A.; González, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Knobel, M.; Reguera, E. 1-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone: From Exfoliating Solvent to a Paramagnetic Ligand. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazawa, T.; Gomi, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Takeda, M.; Enomoto, M.; Miyazaki, A.; Enoki, T. Spin-crossover behaviour of the coordination polymer FeII(C5H5N)2NiII(CN)4. J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazawa, T.; Hosoya, K.; Takahashi, M.; Takeda, M.; Marchuk, I.; Filipek, S.M. 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopic study for Fe(pyridine)2Ni(CN)4spin-crossover compound. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2003, 255, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoya, K.; Kitazawa, T.; Takahashi, M.; Takeda, M.; Meunier, J.F.; Molna´r, G.; Bousseksou, A. Unexpected isotope effect on the spin transition of the coordination polymer Fe (C 5 H 5 N) 2 [Ni (CN) 4]. J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

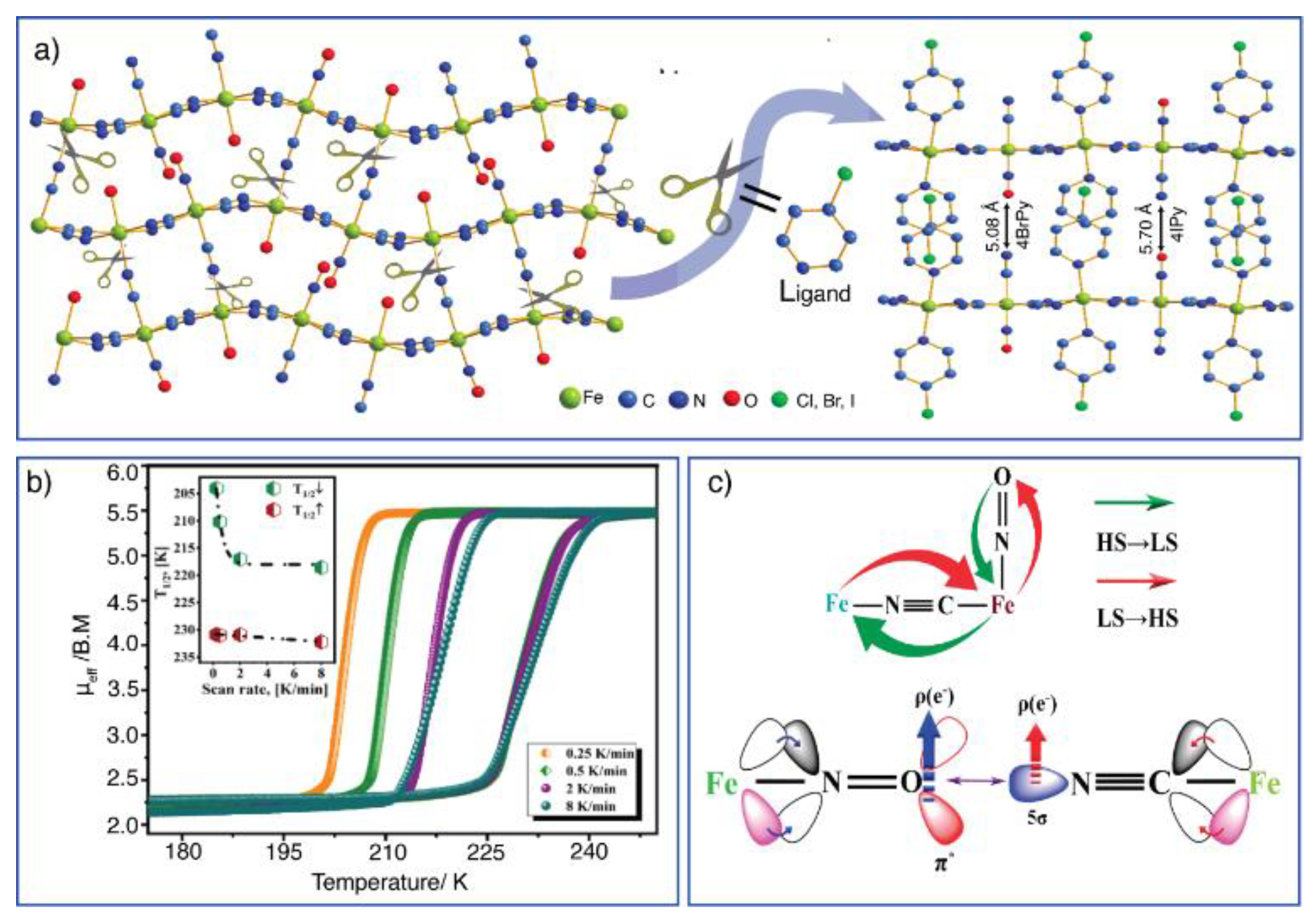

- Avila, Y.; Pérez, O.; Sánchez, L.; Vázquez, M.C.; Mojica, R.; González, M.; Ávila, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E. Spin crossover in Hofmann-like coordination polymers. Effect of the axial ligand substituent and its position. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 10781–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrero, R.; Avila, Y.; Mojica, R.; Cano, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Avila, M.; Reguera, E. Thermally induced spin-crossover in the Fe(3-ethynylpyridine)2[M(CN)4] series with M = Ni, Pd, and Pt. The role of the electron density found at the CN 5σ orbital. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 9618–9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.C.; Real, J.A. Thermo-, piezo-, photo- and chemo-switchable spin crossover iron(II)-metallocyanate based coordination polymers. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2068–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, V.; Gaspar, A.B.; Muñoz, M.C.; Bukin, G.V.; Levchenko, G.; Real, J.A. Synthesis and Characterisation of a New Series of Bistable Iron(II) Spin-Crossover 2D Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2009, 15, 10960–10971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibble, S.J.; Eversfield, S.G.; Cowley, A.R.; Chippindale, A.M. Copper(I) Cyanide: A Simple Compound with a Complicated Structure and Surprising Room-Temperature Reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 628–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibble, S.J.; Cheyne, S.M.; Hannon, A.C.; Eversfield, S.G. CuCN: A Polymorphic Material. Structure of One Form Determined from Total Neutron Diffraction. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 4990–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Arias, D.; Mojica, R.; Zumeta-Dubé, I.; Ruíz-Ruíz, F.; Puente-Lee, I.; Reguera, E. New Understanding on an Old Compound: Insights on the Origin of Chain Sequence Defects and Their Impact on the Electronic Structure of AuCN. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 2021, 3742–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Liang, E.J.; Jia, Y.; Du, Z.Y. Electronic structure, bonding and phonon modes in the negative thermal expansion materials of Cd(CN)2and Zn(CN)2. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 275224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibble, S.J.; Chippindale, A.M.; Marelli, E.; Kroeker, S.; Michaelis, V.K.; Greer, B.J.; Aguiar, P.M.; Bilbé, E.J.; Barney, E.R.; Hannon, A.C. Local and Average Structure in Zinc Cyanide: Toward an Understanding of the Atomistic Origin of Negative Thermal Expansion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16478–16489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korčok, J.L.; Leznoff, D.B. Thermal expansion of mercury(II) cyanide and HgCN(NO3). Polyhedron 2013, 52, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Vázquez, M.; Piedra, O.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, L.; Ávila, M.; Reguera, E. Structural features of the Zn2[M(CN)8] series with M = Nb, Mo, and W and their negative thermal expansion behavior. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, L.; Avila, Y.; Reguera, E. Transition metal nitroprussides: Crystal and electronic structure, and related properties. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M. Prussian Blue: Artists’ Pigment and Chemists’ Sponge. J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.M.; Girolami, G.S. Sol−Gel Synthesis of KVII[CrIII(CN)6]·2H2O: A Crystalline Molecule-Based Magnet with a Magnetic Ordering Temperature above 100 °CCl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garcia, R.; Knobel, M.; Reguera, E. Thermal-Induced Changes in Molecular Magnets Based on Prussian Blue Analogues. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 7296–7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buschmann, W.E.; Miller, J.S. Magnetic Ordering and Spin-Glass Behavior in First-Row Transition Metal Hexacyanomanganate(IV) Prussian Blue Analogues. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Her, J.-H.; Stephens, P.W.; Kareis, C.M.; Moore, J.G.; Min, K.S.; Park, J.-W.; Bali, G.; Kennon, B.S.; Miller, J.S. Anomalous Non-Prussian Blue Structures and Magnetic Ordering of K2MnII[MnII(CN)6] and Rb2MnII[MnII(CN)6]. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguera, E.; Marín, E.; Calderón, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Photo-induced charge transfer in Prussian blue analogues as detected by photoacoustic spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2007, 68, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E.; Lima, E.; Balmaseda, J.; Martínez-García, R.; Yee-Madeira, H. An atypical coordination in hexacyanometallates: Structure and properties of hexagonal zinc phases. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2007, 68, 1630–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, L.; López, N.L.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Martínez-García, R.; Reguera, E. Hydrothermal Recrystallization as a Strategy to Reveal the Structural Diversity in Hexacyanometallates: Nickel and Copper Hexacyanoosmates(II). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubkov, V.; Tyutyunnik, A.; Berger, I.; Maksimova, L.; Denisova, T.; Polyakov, E.; Kaplan, I.; Voronin, V. Anhydrous tin and lead hexacyanoferrates (II). Solid State Sci. 2001, 3, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echevarría, F.; Lemus-Santana, A.; González, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E. Intercalation of thiazole in layered solids. A 3D framework supported in dipolar and quadrupolar intermolecular interactions. Polyhedron 2015, 95, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Ávila-Santos, M.; Vega-Moreno, J.; Portales-Martínez, B.; Vera, M.A.; Lemus-Santana, A.A. Crystallographic and Spectroscopic Footprints of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Hydrogen Bonding within 2D Coordination Polymers. Cryst. Growth Des. 2025, 25, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.; Lemus-Santana, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Aguirre-Velez, C.; Knobel, M.; Reguera, E. Intermolecular interactions between imidazole derivatives intercalated in layered solids. Substituent group effect. J. Solid State Chem. 2013, 204, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, A.; Osiry, H.; Reguera, E.; Alborés, P.; Carbonio, R.E.; Ben Altabef, A.; Gil, D.M. New coordination polymers based on 2-methylimidazole and transition metal nitroprusside containing building blocks: synthesis, structure and magnetic properties. New J. Chem. 2017, 42, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Osiry, H.; Martínez, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Lemus-Santana, A.; Reguera, E. Magnetic interaction in a 2D solid through hydrogen bonds and π-π stacking. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 471, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibble, S.J.; Chippindale, A.M.; Marelli, E.; Kroeker, S.; Michaelis, V.K.; Greer, B.J.; Aguiar, P.M.; Bilbé, E.J.; Barney, E.R.; Hannon, A.C. Local and Average Structure in Zinc Cyanide: Toward an Understanding of the Atomistic Origin of Negative Thermal Expansion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16478–16489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xi, R.; Yin, S.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, R.; Wu, H. Three inorganic-organic hybrid complexes based on isopolymolybdate and derivatives of 1H-4-nitroimidazole. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 258, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; van Deventer, J. The mechanism of enhanced gold extraction from ores in the presence of activated carbon. Hydrometallurgy 2000, 58, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, P.T.; Gray, H.B. Electronic Structure of Nitroprusside Ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 3340–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, P.; Odio, O.; Ávila, Y.; Perez-Cappe, E.; Reguera, E. Effect of water and light on the stability of transition metal nitroprussides. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2021, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, Y.; Osiry, H.; Plasencia, Y.; E Torres, A.; González, M.; A Lemus-Santana, A.; Reguera, E. From 3D to 2D Transition Metal Nitroprussides by Selective Rupture of Axial Bonds. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11327–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Vázquez, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Mojica, R.; Lemus-Santana, A.; Avila, M.; González, M.; Reguera, E. Coexistence of two magnetic sublattices in 2D transition metal nitroprussides, T(L)2[Fe(CN)5NO] with T = Mn, Co, Ni; L = 2-ethylimidazole, Imidazo [1,2-a]pyridine. J. Solid State Chem. 2025, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Mojica, R.; Vázquez, M.C.; Sánchez, L.; González, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E. Spin-crossover in the Fe(4X-pyridine)2[Fe(CN)5NO] series with X = Cl, Br, and I. Role of the distortion for the iron atom coordination environment. New J. Chem. 2022, 47, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Scanda, K.; Díaz-Paneque, L.A.; Cruz-Santiago, L.A.; González, M.; Reguera, E. The Nature of the Atypical Kinetic Effects Observed for the Thermally Induced Spin Transition in Ferrous Nitroprussides with Short Organic Pillars. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 24, e202200252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Plasencia, Y.; Osiry, H.; Martínez-dlCruz, L.; González Montiel, M.; Reguera, E. Thermally Induced Spin Transition in a 2D Ferrous Nitroprusside. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 47, 4966–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Crespo, P.M.; Plasencia, Y.; Mojica, H.R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E. Intercalation of 3X-pyridine with X= F, Cl, Br, I, in 2D ferrous nitroprusside. Thermal induced spin transition in Fe (3F-pyridine) 2 [Fe (CN) 5NO]. J. Solid State Chem. 2020, 286, 121293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, Y.; Crespo, P.M.; Plasencia, Y.; Mojica, H.R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Reguera, E. Thermally induced spin crossover in Fe(PyrDer)2[Fe(CN)5NO] with PyrDer = 4-substituted pyridine derivatives. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 5937–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).