1. Introduction

Currently, academic data is issued and stored within the isolated systems of individual educational institutions, with little to no interoperability among them. This fragmentation directly impacts the verification process, as authenticating records or certificates often requires manual procedures resulting in significant resource and time costs.

The growing need to demonstrate skills and competencies acquired in an increasingly competitive world led to the proliferation of fake academic certificates. These fraudulent documents come from various sources, including “degree factories” [1] that generate fake certificates for sale, documents created by non-existent academic institutions [2], alterations of authentic documents with false dates or courses, certificates produced by dishonest employees of real institutions [2], and inaccurate translations of authentic documents used to meet requirements in other countries.

The inherent fragmentation of the current system, characterized by isolated institutional systems, the absence of universal standards, and reliance on manual verification, is the main cause of the prevalence of fraud and verification challenges. In this context, the problem extends beyond the existence of fake certificates; it stems from a fundamental lack of interoperability and robust trust mechanisms within the traditional academic qualifications’ ecosystem. Rather than introducing uncontrolled decentralization, the proposed solution aims to establish a controlled and verifiable decentralized system where trust is distributed and secured through cryptographic means, thereby reducing reliance on centralized, and often unreliable, authorities.

Moreover, universally accepted standards to represent academic information are non-existent. A critical aspect, usually ignored, is the lack of traceability and verifiability in the case that an institution ceases its educational activities and disappears. This affects all forms of education, either formal, non-formal or informal, which are increasingly relevant in modern professional environments, as evidenced by major companies like Google [3], Amazon (

https://aws.amazon.com/es/certification/?nc1=h_ls, accessed on 22 September 2025) and Microsoft (

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/credentials/, accessed on 22 September 2025) which issue certificates for online courses.

The GAVIN project introduces an innovative solution that leverages blockchain technology to issue, store, retrieve, share, and verify academic information. It supports a flexible format that accommodates all types of certificates, ensures scalability, and complies with the GDPR [4]. The system is designed to harness key blockchain features such as immutability and traceability without requiring educational institutions to alter their existing information systems.

A core design principle of GAVIN is to return control of academic data to its rightful owners, allowing individuals to selectively share all or part of their credentials with third parties. Uniquely, GAVIN also addresses the critical challenge of data verification and recovery in cases where the issuing institution ceases to exist. The model is explicitly designed to meet the stringent requirements of the GDPR [5], while also tackling the scalability limitations typically associated with blockchain technologies.

The primary objective of this study is to qualitatively validate the GAVIN model as a technological solution for issuing and verifying academic certifications, ensuring its scalability, perceived usefulness, and compliance with the GDPR. To achieve this, the following hypotheses are proposed, inspired by the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) for validating technological systems:

H1 (Perceived Usefulness): Participants from the education sector will perceive the GAVIN model as useful for improving the processes of issuing, verifying, and recovering academic certifications.

H2 (Security and Trust): Users will consider the GAVIN model to offer a more secure and trustworthy system compared to current procedures.

H3 (Feasibility): Participants will regard the implementation of the GAVIN model in their institutions as feasible within a medium-term timeframe (2 to 5 years), recognizing its adaptability to diverse educational environments.

H4 (Privacy Protection): Participants will positively evaluate the model’s GDPR compliance as a key differentiating factor, given that data is processed in accordance with one of the world’s most stringent data protection regulations.

2. Context

To understand the relevance and scope of the GAVIN project, the technological, legal, and systemic context in which it operates are briefly discussed below. This section outlines the foundational concepts of blockchain and smart contracts, the regulatory framework established by the GDPR, and the broader challenges posed by fraud and fragmentation in the global education ecosystem. Together, these elements provide the backdrop for the development and evaluation of a secure, scalable, and privacy-compliant solution for academic credential verification.

2.1. Blockchain and Smart Contracts

A blockchain, originally proposed by Nakamoto as the ledger for Bitcoin [6], can be understood as a distributed and decentralized database replicated across the nodes of a peer-to-peer network. Information is organized into blocks that store records and are linked together using cryptographic techniques, forming a digital ledger. Each block contains transactions and other data along with a pointer to the hash of the previous block, ensuring the continuity of the chain. This design allows any user to verify a transaction once it has been recorded. Thanks to cryptography, the records become immutable and trustworthy without the need for a central authority.

Several types of blockchain coexist, each with its specific characteristics:

Public blockchains are open and fully decentralized, meaning anyone can submit transactions, run a node on the network, or participate in block creation. Their main strength lies in transparency and data integrity assurance, although they face limitations in scalability and validation speed. Information confidentiality is virtually nonexistent, as all data is exposed to network nodes. While encrypted data can be stored, the immutable nature of the blockchain poses future risks if encryption algorithms become obsolete. Public blockchains are suitable for scenarios where transparency and decentralization are essential, such as cryptocurrencies. Examples include Bitcoin and Ethereum [7].

Private blockchains are managed by a single organization and are typically referred to as permissioned blockchains, as access is granted by the implementing entity. A prominent example includes solutions developed under the Hyperledger framework by the Linux Foundation [8,9]. Since participants in these networks are identified, consensus mechanisms are less demanding, resulting in faster block creation and improved scalability. Their main advantage is privacy, as only authorized nodes can access the data. This type of blockchain is particularly appealing to businesses and financial institutions that require control, confidentiality, and immutable record-keeping.

Consortium or federated blockchains are jointly managed by multiple organizations, each operating their own nodes. Although participation requires permission, some information can be shared publicly. This places them between public and private blockchains, combining advantages and limitations from both models.

At this point it is important to highlight the concept of smart contracts, introduced by Nick Szabo [10]. These are pieces of code that run automatically when triggered by a user or another smart contract, performing predefined functions as specified in their logic. Once deployed on a blockchain, smart contracts benefit from immutability, resistance to tampering, and autonomous execution without human intervention. Ethereum [11] stands out as one of the most prominent platforms for implementing such contracts, due to its robust support for decentralized applications.

2.2. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [4] is a regulation of the European Parliament that governs the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and the free movement of such data within the European Union. This legal framework covers both clearly identifiable data (e.g., name, address, or date of birth) and any other element that, alone or in combination, can be used to identify an individual. Given the severity of financial penalties for non-compliance, any project involving personal information must be designed according to the principle of ‘privacy, security, and legality by design,’ as established in Article 25 (1) of the regulation, through the implementation of appropriate technical and organizational measures.

The GDPR serves as a cornerstone for ensuring the lawfulness, transparency, and accountability of data processing, in line with the principles outlined in its Article 5. Its scope applies to data controllers and processors operating within the EU, as well as entities outside the EU that process data of EU residents in the context of offering goods or services. Compliance with the regulation not only mitigates legal and financial risks but also strengthens the operational integrity of systems by ensuring mechanisms for control, data minimization, informed consent, and traceability of operations.

2.3. Impact of Fraud in the Global Education Ecosystem

The growing number of fake certificates and fraudulent academic information in an increasingly interconnected society represents a real and growing threat for the integrity of the education systems and even the labour market [12]. Beyond the issue of fraud, the lack of a globally accessible platform for academic information limits the ability to gain a comprehensive view of which studies are most in demand or to compare how students across different countries obtain their qualifications. This represents a missed opportunity to extract valuable educational insights and inform policy development.

The shortcomings of the current system go beyond security concerns, making it difficult to verify diverse types of educational credentials within a unified framework. The problem is both about ensuring the security and integrity of academic records, and also about enabling global verification of educational data. A comprehensive solution, such as the GAVIN proposal, must address both defensive aspects (e.g., fraud prevention, data integrity) and proactive capabilities such as unified verification tools, transforming a security challenge into an opportunity for systemic improvement and innovation in the education sector.

3. Related Work

The educational sector is actively exploring blockchain technology and its applications to effectively protect academic information since 2013 [13]. Despite a growing number of blockchain-based educational proposals and applications, most are still in the early stages of practical development, with only a few truly usable by academic institutions and other stakeholders.

An exhaustive analysis of the scientific literature reveals that the most frequent category for blockchain usage in education is the issuing and verification of academic certificates [14,15,16,17,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Illustrative examples include the University of Nicosia, which was the first higher education institution to use Bitcoin to register academic certificates in 2014 [13]. Another notable exsample is Blockcerts, from the MIT Media Lab [41], an open-source platform built on the Bitcoin and Ethereum blockchains for issuing and verifying academic diplomas. Both projects primarily record a hash digest of academic certificates on the blockchain, not the complete data.

Other relevant initiatives, such as EduCTX [42], are focused on different aspects, proposing the issuance of tokens as credits for learning units, in a similar way to the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS). This research also indicates a predominant focus on the notarization and verification of academic certificates and records, with very little efforts dedicated to more complex academic information, like such as learning stories, learning content, or assessment data.

Sambasiva Rao et al. [43] explored the use of blockchain for issuing and verifying academic certificates, outlining the basic operational flow and discussing associated challenges. Their study mentions Layer 2 blockchains and Lightning Networks as potential solutions to scalability issues. However, regarding GDPR compliance, they only propose the use of protected sandboxes for experimentation with personal data, without presenting any real-world application or product.

Sudha et al. [44] address the challenge of storing certificate data on-chain by opting to store a SHA-256 hash of the data. Similarly, Al Sakib et al. [45] use hashing techniques to record data on-chain. Singh et al. [46] emphasize the need for systems to combat academic fraud and propose a solution that stores hashed certificate data on the blockchain, while using a peer-to-peer network to store the actual content. Although this approach may appear closer to GDPR compliance, it is still not acceptable because hashed data is not considered anonymous under GDPR provisions, since to be deemed as anonymous, data cannot be derived solely from the original data [47]. Moreover, fully decentralized public blockchain solutions are inherently non-compliant with GDPR, as all nodes have access to the stored content, potentially leading to privacy breaches.

Anandapadmanaban et al. [48] introduce the use of NFTs on the Ethereum public blockchain to issue certificates under the EduChain initiative. However, this approach also fails to meet GDPR requirements. Stefan-Robert and Butincu [51] propose a model with on-chain access control and revocation mechanisms, similar to the GAVIN model. Their system uses peer-to-peer networks to store original certificate data, which is not GDPR-compliant as discussed above. While their paper includes the development of smart contracts, it does not present a working prototype or any user feedback through surveys.

Most of the reviewed articles present theoretical models without practical implementation or testing. Exceptions include papers [45] and [48], which describe and showcase developed prototypes of their proposed solutions. However, none of these works include user testing or feedback from real users interacting with the systems. Additionally, studies published prior to 2021 [19] do not address GDPR compliance, nor do they explore strategies for meeting its requirements.

On the other hand, several studies used surveys to explore the adoption of blockchain in the academic sector. For instance, [49] applies the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [50] to evaluate the factors influencing individuals’ willingness to integrate blockchain into educational settings, organizing questions according to TAM’s core dimensions. Awaji et al. [51] focus on the use of blockchain by verifiers and stakeholders to validate academic information, emphasizing the need for a unified solution regardless of the origin of the data. In [52], the authors assess the acceptance of a blockchain-based model for issuing and validating certificates, using hypotheses related to trust, privacy, social influence, efficiency, and cost. Similarly, [53] investigates the feasibility of implementing blockchain technologies in higher education institutions through qualitative surveys and interviews with professors. Mohammad and Vargas [57] present a qualitative evaluation of the challenges reported by participants regarding blockchain adoption in education, based on survey responses. However, none of these studies include user testing of a specific model designed for direct interaction, nor do they assess the usability and functionality of such systems from the end-user perspective.

We can conclude that most blockchain research in education is focused on the issuing and verification of academic certificates. Previous research also shows that compliance with data and privacy regulations, which is instrumental in any open system managing academic certificates, is a challenge that was still unsolved. Existing literature also emphasizes the importance of addressing educational information beyond certification in a scenario where there are no universally accepted standards for representing academic information [41,54,55].

Almost all the analysed initiatives, with the exception of Kuvshinov et al. [56], use only one blockchain. This simplifies the design but inherently limits the performance and compromises scalability. Wahab et al. [57] suggested the use of Tangle, a fast blockchain, which currently does not offer full support for smart contracts. Insofar academic data storage is concerned, it is stored using a combination of off-chain systems and blockchain systems using diverse approaches.

Compliance with the GDPR is not fully addressed by any of these investigated initiatives, with the exception of Molina et al. [58], Daraghmi et al. [59] and Lam y Dongol [54]. However, the two later proposals address GDPR compliance only partially. Only a limited number of initiatives implement data encryption to protect the information.

4. The GAVIN Project (GDPR-Compliant Blockchain-Based Architecture for Universal Learning, Education and Training Information Management)

The current landscape of blockchain applications in education reveals several critical limitations. Most existing solutions struggle to fully comply with the GDPR, fail to comprehensively record diverse types of academic data, and do not adequately address scalability, which in turn is an essential factor for widespread adoption. These shortcomings significantly restrict their practical applicability.

A major gap in the educational ecosystem is the absence of universally accepted standards and centralized yet trustworthy systems for managing academic records. Blockchain technology has the potential to fill this void, but only if it effectively resolves key challenges related to privacy and scalability.

The literature consistently highlights that many blockchain-based educational solutions fall short in terms of GDPR compliance and scalability. These are not minor technical issues, but they are fundamental barriers to real-world adoption, often overlooked in existing implementations. GAVIN’s core purpose is not merely to introduce another blockchain solution, but to offer one that, through its architectural design, directly addresses these critical and frequently neglected challenges. This strategic focus positions GAVIN as a more mature, practical, and legally robust alternative for deployment in complex educational environments.

GAVIN (GDPR-Compliant Blockchain-Based Architecture for Universal Learning, Education and Training Information Management) also incorporates mechanisms for data recovery to prevent information loss, similar to other initiatives. However, it goes further by ensuring persistent storage even if the issuing academic institution ceases to exist, which in turn reinforces its GDPR compliance and sets it apart as a distinctive solution. Another key feature of the GAVIN framework is its ability to selectively share specific portions of a holder’s educational data. It also supports a wide range of academic information formats, offering flexibility in registry structures.

A direct comparison with other existing solutions [60] demonstrates that GAVIN is fully GDPR-compliant, being this compliance a strategic advantage validated by experts [5]. The widespread lack of GDPR adherence among current solutions underscores a significant regulatory and design challenge, which incidentally GAVIN successfully overcomes. While this achievement requires a more complex architecture, such as off-chain storage of personal data, it results in a legally stronger and more reliable system. GDPR compliance is thus a central innovation and a key differentiator for the GAVIN project, making it a viable and trustworthy solution for real-world implementation.

4.1. Architecture and Key Components

GAVIN is designed to issue, store, verify, and retrieve various types of academic information, covering both formal and informal learning contexts. It supports several application scenarios, including the issuing of certificates and the integrated management of academic information, the registry of learning paths, the tracking of competency values and recording academic credits of any kind, with a fully variable and flexible number of fields.

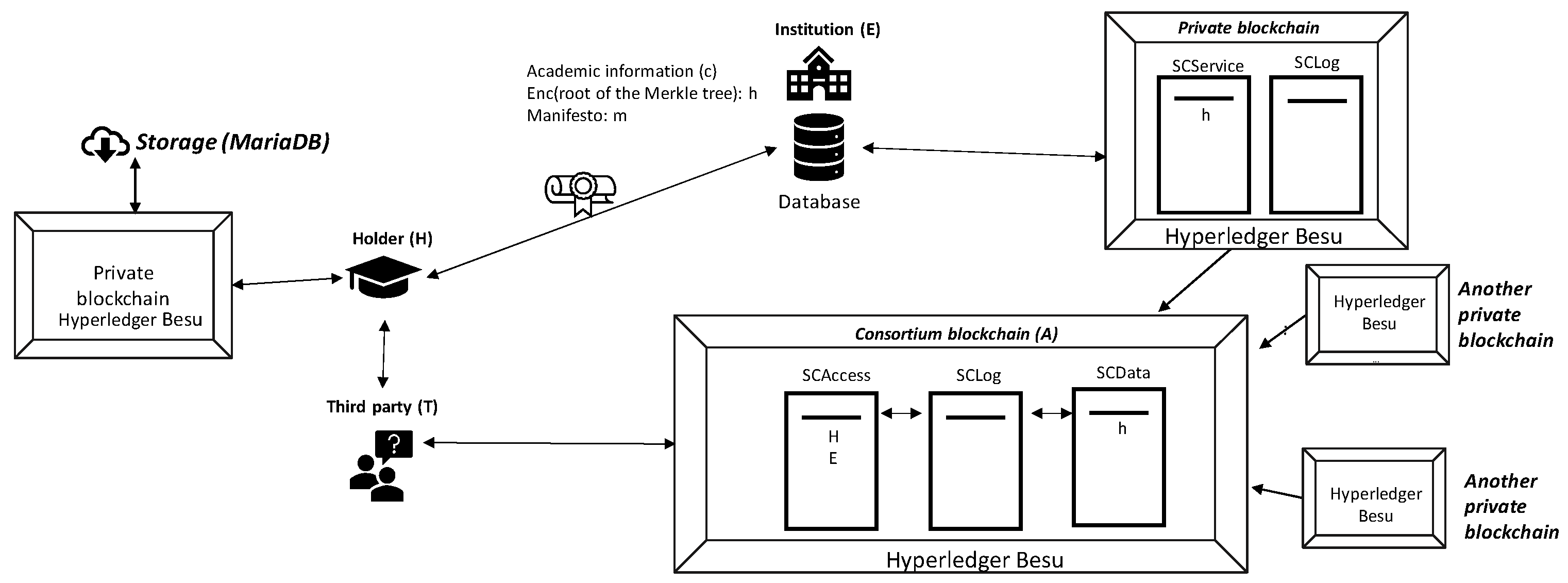

The key elements of the proposed design and its dynamics are depicted in

Figure 1, which provides a general overview of the architecture of the system.

4.2. GAVIN’s Privacy by Design

The GAVIN model is designed under the principle of “Privacy by Design” (Art. 25, GDPR) as a key requirement. It complies with the provisions of Art. 6, Section 1 of the GDPR and related articles, ensuring that data subjects retain control over access to their own personal information. This includes the capacity to partially share their data depending on their interests, to be notified when their data is processed and to request and take away their personal records (Art. 20, GDPR). Moreover, the system supports the critical functionality of granting and revoking permissions to specific third parties (Art. 7, Section 3 of the GDPR). Technically, the “right to erasure” (i.e., the “right to be forgotten” in Article 17 of the GDPR) is explicitly considered in GAVIN’s core design.

To be compliant with the GDPR, personal academic data is stored in the databases of the educational institutions and not directly on the blockchain. This design choice directly addresses the fundamental conflict between blockchain’s immutability and GDPR requirements, as hash digests of personal data are explicitly deemed as a not valid as an anonymization technique from the point of view of the GDPR [61,62].

GAVIN’s strong focus on GDPR compliance drives a key architectural decision: storing sensitive personal data off-chain within institutional databases. This choice is not merely about improving efficiency or storage capacity but a legal necessity. Blockchain’s inherent immutability conflicts with the GDPR’s “right to erasure,” making off-chain storage a foundational requirement. Combined with encryption and key management, this approach reflects an innovative response to strict regulatory demands, as it demonstrates how legal constraints can inspire new architectural models in blockchain design, resulting in systems that are both more robust and legally compliant.

4.3. GAVIN’s Multi-Blockchain Architecture

To tackle scalability and performance challenges, GAVIN adopts a multi-blockchain architecture. Its core consists of a consortium blockchain composed of prominent national and international organizations connected to the education sector. This main chain is linked to an open-ended number of private blockchains, each operated by regional or local academic institutions. These private blockchains function independently and are self-managed, periodically transmitting selected transactions to the consortium blockchain.

This distributed model efficiently handles the complex process of issuing academic credentials, aligning with modern scalability strategies. It is particularly well-suited to the globally fragmented landscape of educational document issuers.

Note that GAVIN’s multi-blockchain design is not a generic technical fix addressing scalability, but a deliberate response to the decentralized and autonomous nature of global education. By respecting institutional independence and avoiding the need for a centralized, monolithic infrastructure, GAVIN offers a solution that integrates seamlessly into legacy educational structures. Besides enhancing scalability, this architectural alignment with real-world educational ecosystems makes GAVIN more adaptable, less disruptive, and more likely to be accepted by diverse institutions.

4.4. Academic Information Workflow in GAVIN

The process starts when an academic institution (E) issues a certificate containing both sensitive data (for example, name, title) and not sensitive information (for example, academic information type, course’s name). A Merkle Tree is generated from the certificate and registered in the private database of the issuing institution (idp). Later, a transaction is sent to a private blockchain containing a pointer to the internal data base registry (idp), the location of the access point to the data base’s server (se), the encrypted root of the Merkle Tree (h), a validity indicator and a list of authorized accounts (aa).

In GAVIN’s architecture, each branch of the Merkle Tree represents a distinct data element, structured according to the issuing institution’s data model. These nodes contain not only academic information but also flexible metadata, such as certificate validity, expiration dates, and other relevant attributes.

To enhance security, each data element within the tree is associated with a unique, non-trivial secret key. A keyed message authentication code (KMAC), based on SHA3 [63], is then computed for each element. This process ensures that the final Merkle Tree root encapsulates both the academic data and its corresponding authentication codes. The issuing entity (E) shares the secret key with the data holder (H), adding an additional layer of anonymization.

KMAC plays a critical role in guaranteeing data integrity and authenticity, as only those with the correct secret key may generate valid authentication codes. Its resistance to preimage and length-extension attacks makes it particularly suitable for environments like GAVIN, where sensitive information must be shared selectively. This method is recognized as a secure approach to data anonymization [5,62].

In a nutshell, each item in the Merkle Tree combines academic data with a unique key provided by the issuer to the holder, ensuring that shared information remains anonymized and protected. This structure allows for granular control over data disclosure: third parties can verify only the specific elements required, without accessing the full dataset, supporting secure, selective sharing.

Optionally non-sensitive public data (pd) can be added to the transaction in the blockchain for the sake of global data analysis as described in the model [12]. The complete certification (c), its encrypted Merkle Tree (h) and the manifesto (m) are transmitted in a secure way to the holder. All the operations are registered in a local log, that is hashed and sent to the blockchain SCLog in order to guarantee traceability. The smart contract SCService acts as the only authorized external access point to the local institution’s data base. Periodically, the private blockchain transmits the registered information (h, idp, se, valid) to the smart contract SCData, on the main consortium blockchain, and the authorized accounts (aa) to SCAccess.

4.4.1. Verification of Academic Information

Three different cases are considered for the certificate verification by a third party (T):

Case 1: Holder sends the certificate to a third party and allows for its verification. On this scenario, the holder (H) sends in a secure way the complete certificate (c) to a third party (T), and simultaneously grants access by adding the account of T to the SCAccess smart contract (aa). T requests the encrypted Merkle Tree root (h) to SCData, which verifies the authorization to T through SCAccess and registers the access attempt in SCLog. If access is provided, T receives the validity status and h, decrypts h with the public key of the institution and compares the result with the Merkle Tree root of (c) in order to verify the authenticity and check if it has been revoked.

Case 2: The holder only wants to share the academic information partially. In this case, the holder (H) wants to share with a third party (T) only a specific part of the academic information contained in the complete certificate (c), revealing only the data necessary to preserve their privacy. To do this, H sends T through a secure channel, only the selected data from the certificate (c), the calculated Merkle Tree paths of the shared information, and the manifest (m). In addition, as in case 1, H adds T’s account in SCAccess (aa) to grant it access, indicating that this is use case number two. When T requests the encrypted root of the Merkle Tree (h) from SCData, it consults SCAccess to verify whether it has permission or not, and it records in SCLog that the holder’s data is accessed by T (or not, if access is not granted). T retrieves the validity status of the data and h, decrypts h with the issuer’s public key, and compares the result with the calculated root of the Merkle Tree and the paths of the received information to confirm its validity and that it has not been revoked.

Case 3: The holder allows a third party to receive the certificate directly from the academic institution. In this scenario, the holder (H) needs a third party (T) to obtain the complete certificate (c) directly from the issuer (E). To achieve this, H adds T’s address in SCAccess (aa), indicating use case number three. T requests the registration of academic information in the database (idp) and the access point to the database server (se) from SCData, which, after verifying T’s permissions in SCAccess, sends them to T. Once T obtains this data and requests the certificate (c) from SCService, after verifying T’s authorization (in SCAccess), SCService consults the information in the local database and sends the data to T via a secure channel. Both SCData and SCService record in SCLog that T has attempted to access or has accessed the record. If necessary, T could confirm the authenticity and validity of (c) by following the procedure in case 1 after finalizing this case 3.

If the academic registries published on the consortium blockchain contain other non-sensitive public personal data, such as the type of academic information, the title, or the certificate’s category, this could be used to generate, in an anonymous way, statistics, learning analytics data or trends relevant to education.

4.4.2. Modification of Academic Information

If the academic institution (E) or the holder (H) want to modify any specific academic information (e.g, to correct a typographical error or incorrect data), the issuing institution would correct the information on its internal data base, generate a new certificate (c’) and send a new h, h’, to the smart contract SCService in the correspondent blockchain, which will generate a new transaction ID (ID’). This information must be sent alongside the new certificate (c’) to the holder (and, if needed, a new manifesto (m’)) so any previous data verification under case 1 or 2 indicates that there has been an alteration. Any modification of the information in the private database must be registered in SCLog. From that moment on, the procedure to verify, modify or eliminate would be the same that if the academic information was new.

4.4.3. Revocation/Deletion of Academic Information

If the issuing institution (E) or the holder (H) wants to delete the academic information, and this is legally possible, the institution must proceed by deleting the academic information and marking the blockchain’s linked data (found in SCService and subsequently SCData), as invalid, resetting the information (idp, se, h) to zero, and deleting all accounts in SCAccess for that record. Only non-personal information would remain on the blockchain in past transactions (idp, se, h, valid), and any subsequent verification of academic data would return an error.

4.4.4. Verification or Retrieval of Academic Information in Case of Issuing Institution Discontinuation

An unsolved problem in all the initiatives that do not store the academic information on-chain in order to be GDPR-compliant is that, if the issuing institution disappears, the education data cannot be recovered (something that can happen frequently, mostly in the informal and non-formal learning, where the information is generated by enterprises of any kind). In the proposed system, if the holder possesses the certificate and the linked information, and the system is yet operative but for the issuer (E) which stopped its activity, cases 1 and 2 can be executed, and the verification of the authenticity can be done without difficulties. Nonetheless, if H does not have the academic certificate anymore and E is no longer available and all its servers and data bases are not operative anymore, the full academic information cannot be recovered (case 3).

To tackle this scenario, and only in case the educational organization E is expected to disappear, the following procedure is proposed:

Before ceasing its education related activities, institution E must publish the affected educational data in its final form, as stored in its databases (encrypted with a key shared with each owner as described in this model), in a distributed database (MariaDB) connected to a private blockchain as an access control mechanism.

If a holder H wants to recover their certificate, they can do it because the private blockchain recognizes them as the data subject and, moreover, given that H has the secret key shared with the disappeared institution E, they could recover the original information.

Under these circumstances, if the holder H deletes their secret key, given that the encrypted information is only saved in a private distributed storage with limited access, the “right to erasure” is achieved, given that the GDPR considers that deleting the keys for decryption is a valid option.

The distributed storage system must have sufficient capacity and scalability, although it should not store all the certificates and academic information ever existed, but only those corresponding to educational institutions that have disappeared.

4.5. GDPR Compliance

The proposed model is designed to meet the most demanding security requirements, namely integrity, confidentiality, authentication, access control, availability, non-repudiation, and, ultimately, full compliance with the GDPR [5].

Data stored on blockchains cannot be modified once recorded due to the blockchain immutability. As a result, integrity is achieved, while only non-personal data is stored on the chain. Academic information (and so, what is considered personal data) is stored off-chain. In the event that the institution disappears, and its information is stored in the distributed database with a blockchain-based mechanism as an access control system, due to it being encrypted with a key only known by the holder and the disappeared organization, it can be considered confidential.

In addition to data security, the designed model preserves privacy through anonymity if the owner uses different accounts, one for each certificate, to avoid linking the various data issued in the chain that belong to them through the same address. As in any other interconnected system, information exchanges must be carried out using secure connections. The security of the nodes that form part of the blockchain and their interconnection with the access points to educational institutions must be properly protected, and each private key must be carefully managed and protected.

With this model, only those third parties authorized by the owner can access the on-chain non-personal information to validate or retrieve educational data, and each operation is recorded in an unalterable manner in the system to provide accountability through a log. To maintain trust in the system, it is important that only recognized entities and organizations can be part of private blockchains and the main consortium blockchain, but that is beyond the scope of the designed model, as it is a matter of official standardization whether to add certain academic organizations to the system. In any case, if any inappropriate behaviour is detected, the institution could always be revoked, and with it, their issued academic data.

Availability is a key feature of blockchain, as, by its very design, it replicates information through various nodes; therefore, this security service will be fulfilled as long as any node in the network remains operational. Non-repudiation can be verified, since to carry out any operation, as described in the model, it is necessary by the different actors to use their private keys and information to sign every transaction, and the result will be permanently recorded in the blockchain, so it cannot be repudiated.

4.6. Proof of Concept Implementation

The viability of the proposed model is demonstrated through the implementation of a proof-of-concept [64] using Hyperledger Besu, an advanced Ethereum client that facilitates confining a permissioned and privacy enabled Ethereum network using the privacy group feature [65,66], to create the private and consortium blockchains, which are connected using an Inter-Blockchain Communication protocol (IBC YUI [67], developed by the Cosmos project [68]) thsat was specifically adapted for GAVIN [69].

4.6.1. Holders and Third Parties

Both holders and third parties have a blockchain account in the system, which will be stored in a Metamask (

https://www.metamask.io, accessed on 22 September 2025) wallet and allow them to consume the services provided in the web developed for GAVIN. It is assumed that both the owner and any third-party user have an account on the main consortium blockchain, and how they obtain it is beyond the scope of this implementation, as it is a basic account generation in HyperLedger Besu.

4.6.2. Education Institutions

The institution is connected to one of the private blockchains based on Hyperledger Besu and has at least one account to issue its various academic data with the appropriate permissions. The process of recovering the holder’s account, generating a shared key, issuing, encrypting, and storing the information in the database, and securely transferring the issued academic data, is beyond the scope of this implementation, as it depends on each particular case and consists of a data exchange between the institution and each student. This proof-of-concept implementation focuses on specific aspects related to blockchain.

Since the institution uses its own information systems, it is considered that they have an API that can be safely used to interact with the associated private chain. The organization does not need to change its information systems to join the initiative, given that GAVIN uses a flexible data model, although some adaptations may be required to connect internal servers to the blockchain using the API provided, which must be properly protected.

4.6.3. Private Blockchains

In this initial implementation, each private blockchain is based on Hyperledger Besu, although any other blockchain framework that supports the proposed model with account-level access control rather than node-level access control [70] can be used, provided that it can connect to the main consortium blockchain to transfer information and has a mechanism for exchanging information with institutions, as described above. The members of the private blockchain and their roles are determined offline, and the infrastructure is provided with sufficient resources to process all the data generated by the connected institutions, which are organized into private blockchains according to geographical, economic, or other criteria (for example, national public universities may be within the same private blockchain, universities belonging to the same federation, etc.). The management of each private chain falls to the group of institutions that form part of it.

4.6.4. Consortium Blockchain

The consortium blockchain is also based on Hyperledger Besu, and its members are recognized academic institutions, each with at least one account and permissions properly configured with associated roles. In this proof-of-concept implementation, at least one node of the main blockchain is connected to each of the private blockchains and periodically retrieves confirmed transactions and operations from the various private blockchains to the consortium, where a new smart contract is implemented in accordance with the proposed model to meet the specifications. The block diagram of the consortium blockchain and how it interconnects with the other private blockchains is shown in

Figure 1.

4.6.5. Data Persistence for Discontinued Institutions

As outlined in Section 3.6, GAVIN provides a mechanism to preserve academic data in the event that an issuing institution ceases to exist. In such cases, the institution’s encrypted academic records can be transferred to a distributed storage system based on MariaDB [71], with access control managed by a smart contract deployed on the consortium blockchain responsible for data verification.

To separate use cases and maintain modularity, this process is implemented using an additional blockchain built on Hyperledger Besu. The data transfer is carried out via an API, allowing an authorized system operator to upload the institution’s records to the MariaDB system. The smart contract then ensures that only the rightful data owner can access and decrypt the information. This enables continued use and sharing of the academic data, as described in use cases 1 and 2.

5. GAVIN Validation

To validate the Proof of Concept of the GAVIN project, a workshop was organized to gather feedback from potential end users. The workshop was organized to include people from various areas related to education, grouped into specific roles to ensure a wide range of opinions. The invited profiles included:

Academic Administration Staff (AAS): Issuers of the credentials, responsible for managing student data and issuing them the certifications.

Students / Job Seekers: Users of the system to whom academic information is issued, owners of their own data, equivalent to the role of “holders”.

IT Managers: Technical profile that provides an informed opinion on the technological choices and architecture of GAVIN’s Proof-of-Concept.

Human Resources and Recruiters: Verifiers of the academic certifications in the enterprises.

Academic Decision-makers: Individuals responsible for managing and defining academic courses, whose opinion is essential for the integration of GAVIN into current academic environments.

A total of 91 people were invited, 75 confirmed their attendance, 73 completed the pre-workshop questionnaire, and 60 completed the post-workshop questionnaire.

5.1. Workshop Design

The preparation for the workshop included the draft of an introductory document, a formal invitation, and a presentation of the Proof-of-Concept and demonstration videos for each of the use cases discussed above.

5.1.1. Instruments

Two questionnaires were designed, one to be responded before and the other after the workshop, to facilitate the collection of ideas and opinions, allowing for a comparison of perceptions. The questionnaires were created using Microsoft Forms and made in the three languages Spanish, Galician, and English. To evaluate users’ perceptions of the technology, the TAM [72] method was followed, which considers perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and perceived enjoyment.

5.1.2. Procedure

The workshop was structured with an introduction to the GAVIN project and its technologies, a technical demonstration, and a question-and-answer session. A video of the use cases was shown instead of a live demonstration to avoid potential technical errors during the workshop. Of the 91 people contacted, 75 confirmed their attendance, 73 responded to the pre-workshop questionnaire, and 60 responded to the post-workshop questionnaire.

5.1.3. Data Analysis

Responses were analysed quantitatively and qualitatively:

Quantitative analysis: Arithmetic means and standard deviations were calculated for each question and role.

Comparative analysis: Pre- and post-workshop responses were compared to assess changes in perception.

Qualitative analysis: Open-ended responses were categorized to identify recurring themes, concerns, and suggestions.

The analysis focused on validating the hypotheses related to usefulness, trust, scalability, and GDPR compliance.

6. Validation Results

This section discusses the outcomes of the validation workshop, that is, the analysis of the responses obtained from the pre and post workshop questionnaires.

6.1. Pre-Workshop Questionnaire

The pre-workshop questionnaire, completed by 73 participants, probed initial expectations and familiarity with relevant aspects of the project. The distribution of roles was balanced, with a lower participation of the profile “Student/Seeking for a job”.

In terms of familiarity with academic certification verification systems, there was an equal split between those who were familiar with them and those who were not, with the majority of those being familiar occasional users. Satisfaction with current verification systems was low, with an average of 2.80 out of 5 for all roles, indicating widespread dissatisfaction. The frequency of fraud issues, verification difficulties, or incomplete verification was perceived as moderately frequent, with an average of 2.63 out of 5, which proves the need for a solution.

General knowledge about blockchain technology, which is fundamental to the model, was low, with an average score of 2.37 out of 5, indicating a superficial understanding on the part of most respondents. In contrast, knowledge about the limitations of the General Data Protection Regulation was slightly higher, with an average score of 2.93, showing a higher level of understanding in comparison with the technical side.

A very positive result was the perception of the usefulness of a system to verify the authenticity of academic certificates, with an average of 4.57 out of 5, indicating strong agreement with the need for a system like that. Similarly, most respondents felt that such a system would improve their institutions’ current procedures for issuing and verifying certifications, with an average of 4.17. However, conviction about the feasibility of implementing such a system in their own institutions was lower, although still in the majority, with an average of 3.91.

The most frequently expressed expectation in the open questions was “To learn more about the model/technologies/system developed,” demonstrating clear curiosity on the developed model of GAVIN. Some respondents mentioned micro-credentials, SIGMA - a cloud-based academic management system widely used in Spanish universities (

https://www.sigmaaie.org/en/solutions/sigma-academic, accessed on 22 September 2025), and Europass (

https://europass.europa.eu/en, accessed on 22 September 2025), indicating their knowledge of current systems related to the issuance of academic certifications.

The analysis by roles in the pre-workshop questionnaire revealed perception variety. IT managers showed slightly higher satisfaction with current systems (3.00), while students/seeking for a job were the least satisfied (2.50). In terms of the frequency of fraud, Academic Administration Staff (AAS) perceived fewer problems (2.25) than HR/Recruiters (2.80). Knowledge of blockchain was low across all roles, with Academic Administration Staff (AAS) reporting the lowest level (1.86). Knowledge of the GDPR was highest among HR/Recruiters (3.20). The perceived usefulness of the system was consistently high across all roles (above 4.50), with Academic decision-makers being the most convinced (4.73). The improvement of current procedures was also highly valued, although IT Managers showed less conviction (3.89). Finally, the feasibility of implementation in the institution itself showed less confidence among Students/Seeking for a job (3.43) and IT Managers (3.67).

Table 1 presents the questions from the pre-questionnaire.

The results of these questions are presented in

Table 2.

6.2. Post-Workshop Questionnaire

After the workshop, 60 of the 75 attendees responded to the post-workshop questionnaire, revealing a general optimism. Most participants were optimistic about the model’s ability to reduce academic fraud and facilitate verification without direct contact with the issuing institution, with an average score of 4.77 out of 5. Similarly, the vast majority believed that implementing the model would speed up the academic certification verification process with an average score of 4.60.

Respondents also perceived the system as more reliable and secure than current procedures, with an average score of 4.65. These positive results were maintained when evaluating whether the use cases presented (issuance, full/partial verification, recovery in case of institutional disappearance) reflected real-life situations and were clearly applicable, with an average score of 4.48. The perception that the implementation of the model would bring modernization to their institutions was also high, with an average of 4.73.

In addition, the general perception was that the model is fairly easy to adapt to existing systems, with an average of 4.22, a satisfactory result given that the Proof-of-Concept yet showed some manual operations to be automatized in a final product. Regarding implementation in their own institutions, a large proportion wanted to see it within the next two years, and a smaller group was positive about the next five years. Attendees had considerable confidence in the system’s ability to adapt to real cases, with an average of 4.35.

The perceived usefulness of an academic certificate verification system remained high, even improving slightly in comparison with the pre-workshop questionnaire (4.74 post-workshop vs 4.57 pre-workshop), with an increase in responses with a value of “5”. The perception that the system would improve the current procedures also became more positive (4.65 post-workshop vs 4.17 pre-workshop), suggesting that the workshop succeeded in demonstrating the applicability of the use cases despite the technological complexity. However, the opinion on the feasibility of their institutions using a system such as the one presented remained virtually unchanged (3.89 post-workshop vs 3.91 pre-workshop), which could be due to the known difficulties of integrating digital certification systems in the academic field.

In the open questions, the most interesting aspects of the workshop were the practicality of the system and its use cases, as well as the consideration of academic data privacy and security. The usefulness of partial verification and the flexibility of the model for non-formal certifications were also highlighted. Suggested improvements focused on the usability and automation of the product, something that must be implemented for a final product, and the need for a business and marketing model.

The main barriers and costs identified for implementation included the potentially high cost, the lack of systems to overall issue digital certificates (due to the education field still being largely paper based), the need for training to use the model, clarification of who bears the costs of using and maintaining the blockchains, the lack of a formal standardization, and the need for global adoption for effectiveness. Additional comments pointed to long term implementation due to the limitations of physical formats (such as The Diploma Supplement [79]), the security of user wallets, and technical complexity, especially in key management and student responsibility for their own data and accounts.

The analysis by roles in the post-workshop questionnaire revealed that students were the most optimistic, especially regarding the implementation of the system, although ironically, they were the least convinced that the system would improve verification procedures.HR /recruiters were the most pessimistic about short-term implementation and the second least convinced about process improvement. IT Managers and Academic decision-makers were the most reluctant about the ease of implementation and coexistence with the current systems, attributing this to the complexity of integrating modern technologies, such as blockchain, in a yet very traditional system, and the need to define maintenance responsibilities.

Table 3 lists the questions of the post-questionnaire.

The results of this questions are presented in

Table 4.

6.3. Perception Evolution (Pre-Workshop vs. Post-Workshop)

The methodology of the workshop, which included questionnaires before and after the presentation of the GAVIN’s Proof-of-Concept, allowed to observe changes in the perception of the participants. This section describes the evolution of participants’ perceptions, comparing the results of the pre-workshop and post-workshop questionnaires for the common questions, and analysing the open responses in bigger detail.

Three key questions in both questionnaires were analysed in order to compare the evolution of technological acceptance, namely perceived utility (i.e., question 5 pre-workshop and 10 post-workshop), improvement on current methods (question 6 pre-workshop and 11 post-workshop) and implementation feasibility (question 7 pre-workshop and 12 post-workshop).

With respect to perceived utility, before the workshop, participants rated this aspect with an average score of 4.57. Following the demonstration of the Proof-of-Concept and the detailed explanation of the GAVIN model, the average increased to 4.74. This improvement, marked by a higher frequency of maximum Likert scores (“5” instead of “4”), suggests that the practical presentation helped reinforce participants’ belief in the usefulness of a system for verifying academic certificates. Despite the inherent complexity of blockchain technology, the inclusion of real-world use cases and the emphasis on data privacy and security resonated positively with the audience.

The second key indicator analyzed was the perceived improvement over current methods for issuing and verifying academic certifications. Before the workshop, this aspect received an average score of 4.17. After the presentation and demonstration of the GAVIN model, the score rose significantly to 4.65. This nearly half-point increase reflects the workshop’s success in clearly communicating the advantages of the proposed system. Despite the potential complexity of the underlying technology, participants recognized how GAVIN’s use cases could substantially enhance existing procedures. The ability to reduce fraud and accelerate verification—without requiring direct contact with the issuing institution—was identified as a major contributor to this improved perception.

The third key indicator examined was the perceived feasibility of implementing the GAVIN model. Before the workshop, this aspect received an average score of 3.91, which remained nearly unchanged at 3.89 after the session. This result suggests that while participants clearly recognized the benefits of the system, they also acknowledged the significant challenges involved in integrating digital certificate solutions within academic institutions. These concerns reflect broader issues such as technological readiness, institutional infrastructure, and the complexity of transitioning to electronic systems for credential issuance and verification.

To contextualize the qualitative feedback gathered during the workshop, three open-ended questions were analyzed to better understand participants’ perceptions of the GAVIN model. These questions focused on (1) the most interesting aspects of the workshop, (2) suggested improvements to the system and its presentation, and (3) perceived barriers and costs associated with implementation. The responses provide valuable insights into both the strengths of the model and the challenges that must be addressed to ensure its successful adoption in real-world educational environments.

Participants consistently highlighted the practicality of the GAVIN system and the relevance of its use cases as the most compelling aspects of the workshop. The model’s strong emphasis on privacy and security in handling academic data was also frequently mentioned, reflecting a growing concern for data protection in educational technologies. Attendees appreciated the system’s ability to perform partial verification of academic certifications, allowing for selective data sharing. Additionally, the flexibility of the model to accommodate non-formal and informal learning credentials was seen as a valuable feature, aligning with the evolving nature of education and lifelong learning.

While the workshop was positively received, several participants suggested enhancements to the Proof-of-Concept, particularly in terms of usability and automation. The current version included manual steps and a limited interface, which some found restrictive. As a result, there was strong interest in organizing a follow-up workshop once a finalized product is available. Another recurring suggestion was the development of a clear business model and marketing strategy to support broader adoption. Many participants noted that more detailed feedback could be provided once the system is fully operational and ready for real-world use by end-users.

Finally, despite the enthusiasm for the GAVIN model, participants identified several barriers to implementation. The most common concern was the potentially high cost of deploying and maintaining the system, especially in institutions that still rely heavily on paper-based processes. The lack of standardized digital infrastructure and the need for user training were also seen as significant challenges. Questions around who would bear the costs of blockchain maintenance and system operation added to the uncertainty. Furthermore, the absence of formal standardization and the need for global adoption were highlighted as critical factors for achieving full effectiveness. Additional concerns included the long-term transition from physical formats like the Diploma Supplement, the importance of securing users’ wallets to prevent key loss or theft, and the technical complexity of key management and user responsibility for personal data.

Table 5 summarizes the average scores before and after the workshop, along with the absolute and percentage changes.

6.4. Perceptions According to Participants’ Role

The role analysis in the post-workshop questionnaire revealed that students were the most optimistic, especially regarding the implementation of the system, although ironically, they were the least convinced that the system would improve verification procedures. Nonetheless, it is highlightable that they also think a tool to verify their academic information is useful, with an unanimity of 5 points over 5. This shows that they care about the verification of their hard-earned skills, although they may not be familiar with the technical specifications. But they think that a verification process must exist, so they do not have to compete in the market with people who fake their own certifications to get a job or enter a certain university.

The fact they are the least convinced that GAVIN will improve the verification procedures makes sense due to them not being familiar with the verification process, task made by the third parties receiving the students’ certifications. Nonetheless, given how the model offers solutions to all roles involved in a certificate issuing and verification, students can see the value on having all their academic data stored in a same place, making easier for them to present it to third parties all at once. Not only that, but they see also great value in the privacy preservation of their information, being allowed to share only partial information with said third parties.

The role of HR/recruiters was the most pessimistic about implementation in the short term and the second least convinced of process improvement. This is due to the difficulties to implement any kind of digital certificates system within the educational sector. Both the need of a standardization at a big enough scale and the differences between all the academic entities systems make the implementation a challenge.

On the other hand, they were the group that would like to see this system fully implemented as soon as possible, preferable in 2 years, due to all the issues regarding fake certificates that the model solves. This makes sense due to current models, as they explained, are too diversified depending on the academic certification origin and type, which sometimes can be even manually made and therefore slow.

At the same time, it is also highlightable that HR/recruiters are the second role, after the student’s role, to believe that the GAVIN model is more secure and trustworthy than the current verification systems. They also consider that the showcased use cases in the workshop are a good reflection of the reality and real use cases executed daily. This indicates that the model accomplishes successfully all the required functionalities that its potential users need and execute, and not only that, but it does also it in a better way than current models and technologies used in the academic field.

IT managers and Academy decision-makers were the most reticent to the easiness of the implementation and coexistence with current systems, attributing it to the complexity of integrating modern technologies such as blockchain and the need to define maintenance responsibilities. They were concerned about the difficulties of implementing digital models in the education field, given how current important and widely established certifications, like the European Diploma Supplement, still are mainly issued only in traditional mediums, that meaning on paper. The lack of integration of digital models and initiatives by the authorities in the education field, regardless of technology, level of complexity or even provided solutions, makes more difficult for roles familiar with these procedures to believe in the easy implementation of a model like GAVIN.

On the other hand, AAS is the most optimistic role when thinking of integrating this model within the already existing infrastructures.

They are also the second role to want this technology to be implemented in the next 5 years. This mirrors the necessity from other roles too of having a trustworthy system to verify certifications, to fix the problem. Nonetheless, they think in the long term (5 years vs 2 years) because of the same reason behind the reply to this other question. On “I consider it feasible for my institution to use a system to issue and/or verify academic certifications, depending on the type of organization”, they are the role that changed their mind the most regarding the question about going from a 4.25 in the question before the workshop to a 3.67 after it. This question is about the feasibility of the GAVIN model being adopted by the education entities they work in, and due to similar concerns other roles, like HR/recruiters, have shown, they are aware of the difficulties to integrate any kind of digital model into their system, with a likely added difficulty due to the usage of innovative technologies such as blockchain.

We can deduce that, in general lines, all the roles see in the model of GAVIN a complete solution for their necessities that also solves the current issues of the verification systems in the educational field. But, at the same time, they also admit that the multiple bureaucratic processes, and already established traditional systems in the education field, mean an added difficulty for any digital verification system to be implemented on it.

The results confirm the initial hypotheses. Perceived utility (H1) received an average score of 4.74 out of 5, while perceived security (H2) scored 4.65. Implementation feasibility (H3) was rated at 4.40 for the next two years and 4.68 for the next five years. Furthermore, GDPR compliance (H4) was frequently highlighted as a positive aspect in open-ended responses, reflecting a strong interest in personal data protection.

7. Discussion

As a general remark, end users expressed a positive attitude toward technologies like the one proposed by GAVIN. However, due to existing challenges in integrating digital certificate systems within the academic sector, their optimism about actual implementation is somewhat tempered. This concern is especially noticeable among IT managers and academic decision-makers, likely because they are directly involved in the setup and training required for new technologies.

Despite the need for broad institutional acceptance, users acknowledged that GAVIN effectively addresses several current issues related to certificate issuance and verification. They appreciated the platform’s flexibility in supporting any data model, regardless of structure, which facilitates integration with existing systems. Notably, users found the verification process intuitive and valued the ability to check multiple certifications in one place. They also highlighted the system’s strength in detecting fraudulent certificates, thanks to its blockchain foundation.

Some participants felt that the Proof-of-Concept was still somewhat difficult to use, but this was attributed to its early-stage development. As a consequence, it was concluded that it would be beneficial to repeat the workshop with a finalized version of the product, for example eliminating manual steps and allowing users to interact directly with a polished interface.

In summary, it was confirmed that workshop results validate the proposed hypotheses. Participants recognized GAVIN’s usefulness, security, scalability, and regulatory compliance, reinforcing its potential as a technological solution for the educational ecosystem.

8. Conclusions

The outcomes of the validation workshop reflect a broad positive reception of GAVIN across various stakeholders within the education sector. Participants widely acknowledged the system’s potential to reduce academic fraud, streamline verification processes and enhance the security and reliability of credentials. Particularly appreciated were GAVIN’s adaptability to different learning formats (i.e., formal, informal, and non-formal) and its strong emphasis on GDPR compliance and data privacy. The multi-blockchain architecture and scalability-oriented design were also recognized as relevant strengths, addressing key limitations found in existing solutions.

Nonetheless, despite the positive perception of GAVIN’s utility and innovation, the study also highlights significant challenges in transitioning toward real-world deployment. Concerns were raised about the high implementation costs, the lack of standardized digital infrastructure in many institutions, and the need for comprehensive end-user training. Additionally, the absence of a clear business model and marketing strategy, along with uncertainty around blockchain maintenance responsibilities and associated costs, were identified as critical barriers to widespread adoption. The technical complexity of blockchain was also seen as a potential obstacle, particularly in the management of keys and credentials, and the responsibility placed on data holders.

The persistence of these concerns, even after the Proof-of-Concept demonstration, suggests that the challenges are not purely technical but also organizational, financial, and regulatory. The still limited integration of digital certificates in many institutions remains a fundamental barrier for solutions like GAVIN’s. To unlock its full potential and enable global adoption, greater standardization and coordinated efforts from educational authorities will be required, possibly at an international level.

The qualitative analysis of user feedback, especially the differences observed across roles, with students showing more enthusiasm and HR/IT professionals expressing greater caution, offers valuable insights for future development. To gather more precise and actionable feedback, it would be beneficial to conduct additional workshops using a finalized and fully functional version of the platform. This would allow for deeper user interaction, increased automation, and a more direct comparison with existing systems in educational institutions, ultimately helping refine GAVIN’s design and implementation strategy.

The qualitative methodology employed, including pre- and post-workshop questionnaires based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), demonstrated to be highly effective in capturing user perceptions and validating the proposed hypotheses. The structured approach and diversity of participant roles provided a solid foundation for analysis and reinforced the relevance of the GAVIN model within real educational contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.-v.-E., L.A.-R. and M.J.F.-I.; methodology, C.D.-v.-E.; software, C.D.-v.-E. and M.R-M; validation, C.D.-v.-E., L.A.-R., M.J.F.-I. and M.R-M; formal analysis, C.D.-v.-E., L.A.-R., M.J.F.-I. and M.R-M; investigation, C.D.-v.-E. and M.R-M; data curation, C.D.-v.-E., L.A.-R., M.J.F.-I. and M.R-M; writing—original draft preparation, C.D.-v.-E.,M.J.F.-I. and M.R-M; writing—review and editing, C.D.-v.-E., L.A.-R., M.J.F.-I. and M.R-M; supervision, C.D.-v.-E., L.A.-R. and M.J.F.-I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Grant TED2021-130828B-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the member of the GAVIN team at atlanTTic, Pablo Molina-Martínez, for his insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- O. S. Saleh, O. Ghazali, and M. E. Rana, “Blockchain based framework for educational certificates verification,” J. Crit. Rev., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 79–84, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Muzammil, “Corrupt schools, corrupt universities: What can be done?,” Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 385–387, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Google, “Creating Pathways to Careers in IT,” 2019. Available online: https://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/it_cert_impactreport_booklet_rgb_digital_version.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- P. Voigt and A. Von dem Bussche, The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Springer Cham, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Gómez-Vieites, C. Delgado-von-Eitzen, and D. Estévez-Garcia, “GDPR-Compliant Academic Certification via Blockchain: Legal and Technical Validation of the GAVIN Project,” Appl. Sci., vol. 15, no. 16, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Nakamoto, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System,” 2008. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, Z. Zou, and D. Song, “Ethereum Tools and Frameworks,” in Learn Ethereum: Build your own decentralized applications with Ethereum and Smart Contracts, Packt, 2019, pp. 294–335.

- Hyperledger, “Whitepaper Introduction Hyperledger,” July 2018, 2018. Available online: https://www.hyperledger.org/learn/white-papers.

- E. Androulaki et al., “Hyperledger Fabric: A Distributed Operating System for Permissioned Blockchains,” in Proceedings of the Thirteenth EuroSys Conference, in EuroSys ’18. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2018, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- N. Szabo, “Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks,” First Monday, vol. 2, no. 9, 1997. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Antonopoulos and G. Wood, “Mastering Ethereum. Building Smart Contracts and DApps.,” 1st. ed.1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472: O’Reilly Media, 2019, pp. 297–318.

- C. Delgado-von-Eitzen, L. Anido-Rifón, and M. J. Fernández-Iglesias, “Application of Blockchain in Education: GDPR-Compliant and Scalable Certification and Verification of Academic Information,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Grech and A. F. Camilleri, “Blockchain in Education,” Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Alammary, S. Alhazmi, M. Almasri, and S. Gillani, “Blockchain-Based Applications in Education: A Systematic Review,” Appl. Sci., vol. 9, no. 12, p. 2400, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Bhaskar, C. K. Tiwari, and A. Joshi, “Blockchain in Education Management: Present and Future Applications,” Interactive Technology and Smart Education, vol. ahead-of-p, no. ahead-of-print. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Caldarelli and J. Ellul, “Trusted Academic Transcripts on the Blockchain: A Systematic Literature Review,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 4, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Q. Castro and M. Au-Yong-Oliveira, “Blockchain and Higher Education Diplomas,” Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 154–167, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Dash, G. Panda, A. Kumar, and S. Luthra, “Applications of blockchain in government education sector: a comprehensive review and future research potentials,” J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 449–472, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Delgado-von-Eitzen, L. Anido-Rifón, and M. J. Fernández-Iglesias, “Blockchain Applications in Education: A Systematic Literature Review,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 24, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Hameed et al., “A Review of Blockchain based Educational Projects,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 10, no. 10, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Kabashi, H. Snopce, A. Aliu, A. Luma, and L. Shkurti, “A Systematic Literature Review of Blockchain for Higher Education,” in 2023 International Conference on IT Innovation and Knowledge Discovery (ITIKD), 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- F. Loukil, M. Abed, and K. Boukadi, “Blockchain adoption in education: a systematic literature review,” Educ. Inf. Technol., vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 5779–5797, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Malibari, “A Survey on Blockchain-based Applications in Education,” in 2020 7th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 2020, pp. 266–270. [CrossRef]

- P. Ocheja, F. J. Agbo, S. S. Oyelere, B. Flanagan, and H. Ogata, “Blockchain in Education: A Systematic Review and Practical Case Studies,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 99525–99540, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Raimundo and A. Rosário, “Blockchain System in the Higher Education,” Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 276–293, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Razia and B. Awwad, “A Comprehensive Review of Blockchain Technology and Its Related Aspects in Higher Education BT - Technologies, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Learning Post-COVID-19: The Crucial Role of International Accreditation,” A. Hamdan, A. E. Hassanien, T. Mescon, and B. Alareeni, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 553–571. [CrossRef]

- M. Talat, S. Riaz, and M. S. Farooq, “Effect of Blockchain on Education: A Systemic Literature Review,” VFAST Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 10, no. 2 SE-Articles, pp. 116–124, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Yumna, M. M. Khan, M. Ikram, and S. Ilyas, “Use of Blockchain in Education: A Systematic Literature Review,” N. T. Nguyen, F. L. Gaol, T.-P. Hong, and B. Trawiński, Eds., in Intelligent Information and Database Systems, vol. 11432. Springer, Cham, 2019, pp. 191–202. [CrossRef]

- P. Chinnasamy, D. R. Ramani, R. K. Ayyasamy, B. J. A. Jebamani, S. Dhanasekaran, and V. Praveena, “Applications of Blockchain Technology in Modern Education System – Systematic Review,” in 2023 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), 2023, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- D. Hu, D. Pongpatcharatrontep, S. Timsard, and A. Khamaksorn, “Blockchain Applications in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review,” in 2023 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), 2023, pp. 188–193. [CrossRef]

- A. Rustemi, F. Dalipi, V. Atanasovski, and A. Risteski, “A Systematic Literature Review on Blockchain-Based Systems for Academic Certificate Verification,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 64679–64696, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Al-Tawara, M. Qasaimeh, D. Jarad, and R. S. Al-Qassas, “Utilizing the Blockchain Technology for Higher Education in the Era of Pandemics: A Systematic Review,” in 2023 14th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Molopa and J. Cronje, “Research on Blockchain Adoption in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Model,” in Advances in Information and Communication, K. Arai, Ed., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 110–130.

- S. Vaezinejad, Y. Chen, M. Kouhizadeh, and K. Ozpolat, “Blockchain Technology for Higher Education and Recruitment: A Systematic Literature Review,” Eurasian J. Bus. Econ., vol. 17, no. 33, pp. 1–27, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, M. Younas, Y. Jiang, M. Imran, and N. Almusharraf, “Transforming Education Through Blockchain: A Systematic Review of Applications, Projects, and Challenges,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 13264–13284, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Silaghi and D. E. Popescu, “A Systematic Review of Blockchain-Based Initiatives in Comparison to Best Practices Used in Higher Education Institutions,” Computers, vol. 14, no. 4, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Jain, N. Seth, K. Sood, and S. Grima, “Mapping the Research on Blockchain in Education: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis,” in Digital Transformation, Strategic Resilience, Cyber Security and Risk Management, K. Sood, B. Balusamy, and S. Grima, Eds., in Contemporary Studies in Economic and Financial Analysis, vol. 111C. Emerald Publishing Limited, 2023, pp. 53–66. [CrossRef]

- A. de Alwis, A. Shrestha, and T. Sarker, “Exploring Governance for Accreditation in the Education Sector using Blockchain Technology: a Systematic Literature Review,” Discov. Educ., vol. 4, no. 1, p. 57, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Ayare A A, Jadhav V A, Banatwala M K, Shashank V. Changllere, Aparna Mote, “A Systematic Review on Blockchain-Based Framework for Storing Educational Records Using InterPlanetary File System,” Cureus J Comput Sci 2, 2025. [CrossRef]