1. Introduction

In late 2008, amid a world financial crisis, people were losing trust in traditional banking systems [

1,

2], a revolutionary new proposition for a cash system was proposed by Satoshi Nakamoto [

3], based on a new underlying technology, that promised to eliminate the middleman in online transactions: the blockchain. Although, the term "blockchain" was coined sometime after this proposition, it is no wonder that blockchain technology is mostly known in the context of cryptocurrencies, especially Bitcoin. However, it’s potential goes beyond currencies, opening the doors to many new impactful changes in the digital world [

4], stemming a race to create and implement blockchain-based systems on various sectors, with major efforts from big actors, such as the Estonian government, who’s trying to turn several services into blockchain-based digital services [

5].

By leveraging blockchain technology, it is possible to create better technological systems, allowing to effectively deal with the fake credential market, with estimates suggesting a yearly revenue of

$7 billion [

6], as its intrinsic properties of immutability, security and decentralization allow for secure, transparent and efficient processes of issuance and verification. Recognizing the potential of blockchain, the European Commission created the European Blockchain Service Infrastructure (EBSI), with the aim to enhance the delivery of cross-border digital public services [

7], including the education sector, allowing European citizens to access a wide range of digital services. Using EBSI as the underlying blockchain platform in the development of an issuance and verification system for higher education, allows for not only secure and tamper-proof digital certification but also for standardization of credentials, enabling simple cross-border verification, which aligns with the European Union’s goal of digital transformation and the establishment of a unified digital market [

8].

This paper proposes an architecture for a blockchain-based framework that will allow for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to onboard and have access to secure workflows of issuance and straightforward verification processes for their digital credentials and is structured as follows:

Section 2 details the literature review conducted to build the knowledge base needed for this project.

Section 3.1 details the proposed system design and architecture.

Section 3.2 details the development of the system, providing an overview of the implemented functionalities.

Section 3.3 details the tests carried to evaluate the system. Finally,

Section 4 concludes this article, offering a critical outlook on the developed system and details future work.

2. Literature Review

To conceptualize such a system, it is crucial to conduct a systematic literature review, as it allows to both further expand the understanding of these concepts and gain insight into what the challenges faced are and architectural choices other researchers reported on, which will result in a better and more concise architecture. Through a thorough analysis of relevant literature, this review identifies common challenges and examines the gaps in existing implementations. The chapter begins by explaining the methodology used to select relevant studies, followed by an analysis of their approaches and architectures, and concludes with a discussion of key findings and implications for future implementations.

2.1. Methodology

To ensure a systematic review, a structured search was conducted following the PRISMA framework guidelines [

9]. The search was conducted using the SCOPUS database, employing the query string: “blockchain” AND “high* education” AND (“digital certification” OR “diplomas” OR “certificates”) AND “decentralized”. The inclusion criteria required that studies: (1) describe an implementation of a blockchain-based system for diploma issuance, (2) be written in English, and (3) be readily available through open access or institutional availability. After screening 21 initial documents, 13 studies were selected for the review.

2.2. Analysis

Among the analyzed studies, the architectural choice that most impacted the proposed systems was the use of permissioned or public blockchains, as it cascaded into several other choices dependent on the type of blockchain chosen. While implementations using permissioned blockchains enforced hierarchical access control, establishing trust chains encompassing governmental and educational entities [

10,

11,

12,

13], systems using public blockchains implemented control mechanisms at the application layer, with approaches ranging from consortium governance [

14] to democratic voting system [

15].

Some chose hybrid approaches balancing privacy and transparency, combining permissioned networks for transactions with public blockchains for verification [

16], or even implementing both public and private smart contracts for different access scenarios [

17]. Most of the systems opted for storing only the hashed credential on-chain, while storing the complete credentials in off-chain storage like Interplanetary File System (IPFS). Exceptions included [

17] and [

18] which stored all data on-chain. Additionally, only [13] used standardized data models, namely W3C Verifiable Credentials (VC).

When it comes to verifying the credentials, nearly all implementations offered web applications for that purpose. Though most required handling hash values, the more user-friendly approaches employed QR codes to facilitate the verification process [

19,

20].

2.3. Challenges Faced

The literature revealed several challenges in implementing blockchain-based certification systems.

Scalability and operational cost were prevalent issues across both permissioned [

10,

17,

21] and public blockchain [

16,

22] implementations, particularly in Ethereum-based systems where fees became especially problematic as system complexity grew. To address this, [

22] implemented a mass registration mechanism for credentials, reducing transactional costs.

When it comes to privacy, both technical and regulatory challenges were mentioned, with [

10] highlighting Ethereum’s privacy limitations at both the network and data levels, explaining that encryption mechanisms would significantly impact the performance and cost of the system. Regulatory compliance, mainly with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), was brought up by [

13] and [

16], with the former ensuring compliance by the European Blockchain Service Infrastructure’s (EBSI) inherent compliance and the latter proposing off-chain decentralized storage for sensitive data.

Critical security concerns, such as the loss or compromise of private keys, were mentioned as “catastrophic” by [

16], being further emphasized by [

13], saying that re-issuance of all credentials would be necessary upon private key loss, since the key is intrinsically tied to the holder’s Decentralized Identifier (DID).

Some other challenges involved operational difficulties, mainly when integrating with legacy systems, with [

13] noting significant effort integrating the system with institutional information systems. Such issues were addressed by [

21], which implemented an Application Programming Interface (API) gateway to interface between the legacy and blockchain-based systems.

Ensuring true decentralization was presented by [

15] as being the main engineering challenge faced, noting that centralized governance of smart contracts, centralized servers for client requests and centralized data storage could undermine the decentralized nature of blockchain.

Lastly, governance and standardization emerged as overarching hurdles for the adoption of blockchain systems for the educational sector, as the lack of governance rules and laws [

16], the need for robust governance frameworks in multi-stakeholder environments [

21] and the lack of comprehensive policies on the adoption of blockchain in education [

11], are all aspects that need to mature further until widespread adoption can take place.

2.4. Discussion

This review revealed a fundamental divide between implementations that used public blockchains (mainly Ethereum) and those that used permissioned blockchains (primarily Hyperledger), each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Ethereum-based implementations prioritized transparency and decentralization at the cost of privacy and high operational costs due to fees. Although [

22] proposed mechanisms to reduce these costs, they introduced additional complexity to smart contracts implementation. In contrast, Hyperledger-based systems prioritized privacy and control through strict access systems, exemplified by [

10] chain of trust system. There were, however, some that tried to balance these concerns in a hybrid-like approach. [

16] implementation managed to ensure both privacy and transparency by combining a permissioned network for transaction handling with a public blockchain for credential issuance and verification, at the expense of added complexity in maintainability and scalability

When it comes to data handling, most systems stored the credential data off-chain, typically in IPFS, with only the hash values being stored on chain. However, both [

17] and [

18] implementations, opted for storing all the data on-chain, potentially creating privacy concerns and scalability issues. The IPFS-based approach represents a pragmatic middle ground but raises some concerns about data availability and node management. [

16] addressed this problem by delegating responsibilities to a Data Availability Committee (DAC), while [

13] innovatively used digital wallets for credential storage, enabling Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI).

The user experience of the verification processes varied considerably regarding technical complexity. Most implementations required users to work with hash values and identifiers, potentially limiting the usability of the systems. More user-friendly approaches were presented by [

19] and [

20], where QR codes are used to facilitate this process. The literature presents different tradeoffs when it comes to security. The multi-signature mechanism suggested by [

22] enhanced security but increased system complexity and cost, while [

18] automated issuance process reduced the risk of human error, resulting in a diminished need for credential revocation.

Some implementation’s technical sophistication presented interesting choices, such as [

12] use of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) for credential representation, [

15] democratic voting system for consortium management, and [

13] use of standardized data models, like W3C Verifiable Credentials.

The architectural and technical choices that stood out the most, among the literature, were: the adoption of standardized data models [

13], hybrid architectures that balance privacy and decentralization [

16], the use of digital wallets for credential storage [

13] and the automation of processes to reduce errors [

18]. However, several aspects required further investigation, including credential revocation mechanisms, how to deal with the scalability issues and how to improve key management systems to better the security and trustworthiness of blockchain-based certification systems. While only one study used EBSI [

13], its advantages coupled with insights form other implementations, provide a substantiated guide for future systems suitable for widespread adoption in the educational domain.

3. Results

3.1. Proposed Architecture

After carefully analyzing the literature, an architecture proposal was conceptualized, addressing key challenges identified, while leveraging features that positively impact such systems, to best meet the requirements of all the stakeholders involved.

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) require tamper-proof credential issuance while maintaining control over the system. Students need to have their privacy assured, while having control over their data. Employers and other third parties demand a simple verification process to assess the veracity of a credential, without requiring any technical knowledge. The proposed architecture aims to satisfy these requirements while remaining technically feasible.

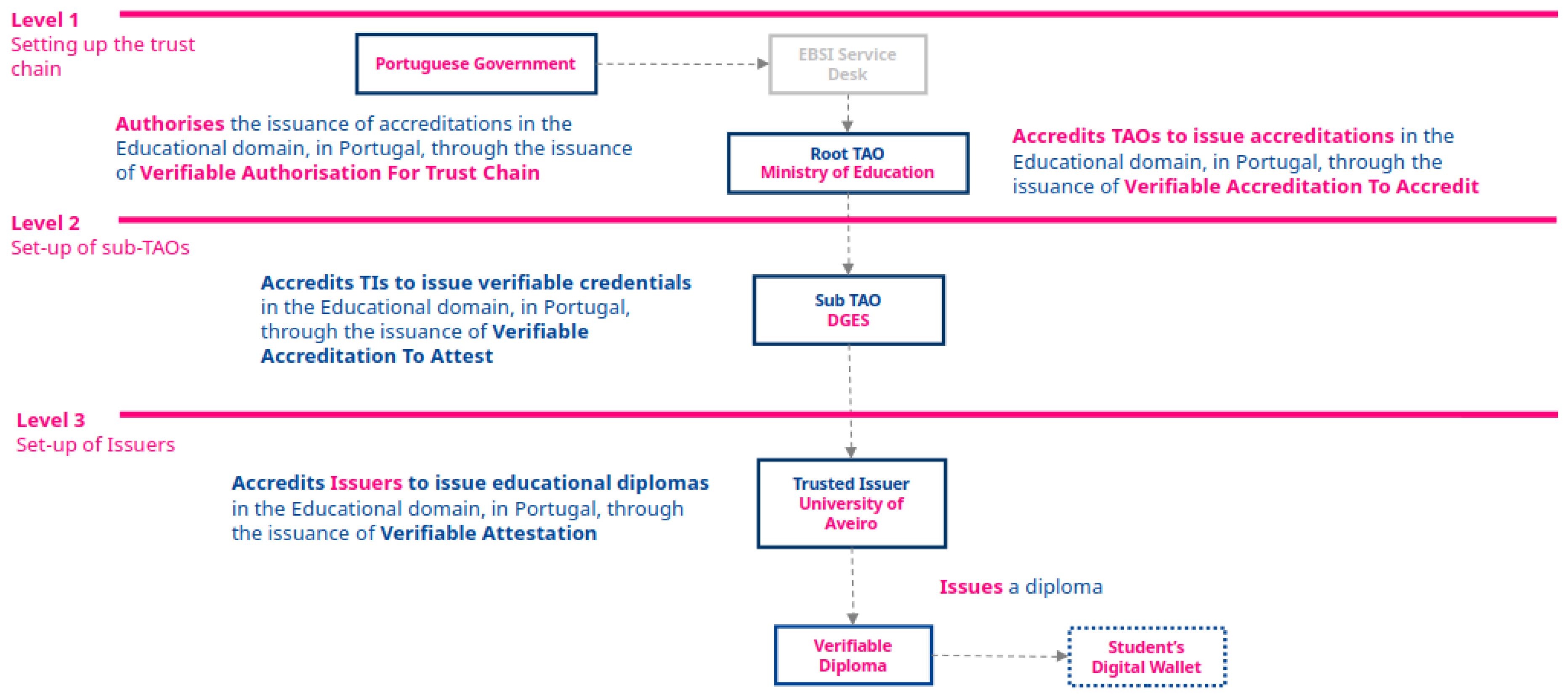

3.1.1. Trust Chain

The European Blockchain Service Infrastructure (EBSI) requires the establishment of a trust chain to ensure the security and trustability of the issuance process. Without this chain of trust, verifiers cannot confidently determine if a credential was legitimately issued by an authorized institution.

A trust chain establishes a hierarchical relationship between the actors of the systems, where trust is inherited from the top of the chain, making a system as trustable as the entity that sits at the top of the chain. By establishing trust between all the entities that take part in the system, it allows for secure, trustworthy and decentralized processes of issuance for academic credentials.

A trust chain is made up of 3 different roles: a Root Trusted Accreditation Organization (Root TAO), which represents the root of trust for the system and has complete control over it; the Trusted Accreditation Organization (TAO), which is delegated responsible, by the Root TAO, for overseeing a segment of the trust chain (the educational domain for example); and Trusted Issuer (TI), who is responsible for issuing the credentials to the end user. By building these trust relationships, the system addresses a key concern identified in the literature: ensuring that decentralization does not come at the expense of legitimacy, allowing a credential to be traced backed to the source of trust without having to rely on a single central authoritative entity.

The proposed trust chain is described in

Figure 1, spanning several governmental and educational institutions. It starts with the establishment of the Ministry of Education as the Root TAO, by having the government contact EBSI Support Office, establishing the root of trust of the educational domain. Having established the Root TAO, the entity responsible for overseeing Higher Education is accredited as a TAO, which will authorize it to accredit HEIs as Trusted Issuers, allowing them to issue Verifiable Credentials for their students.

3.1.2. System Architecture

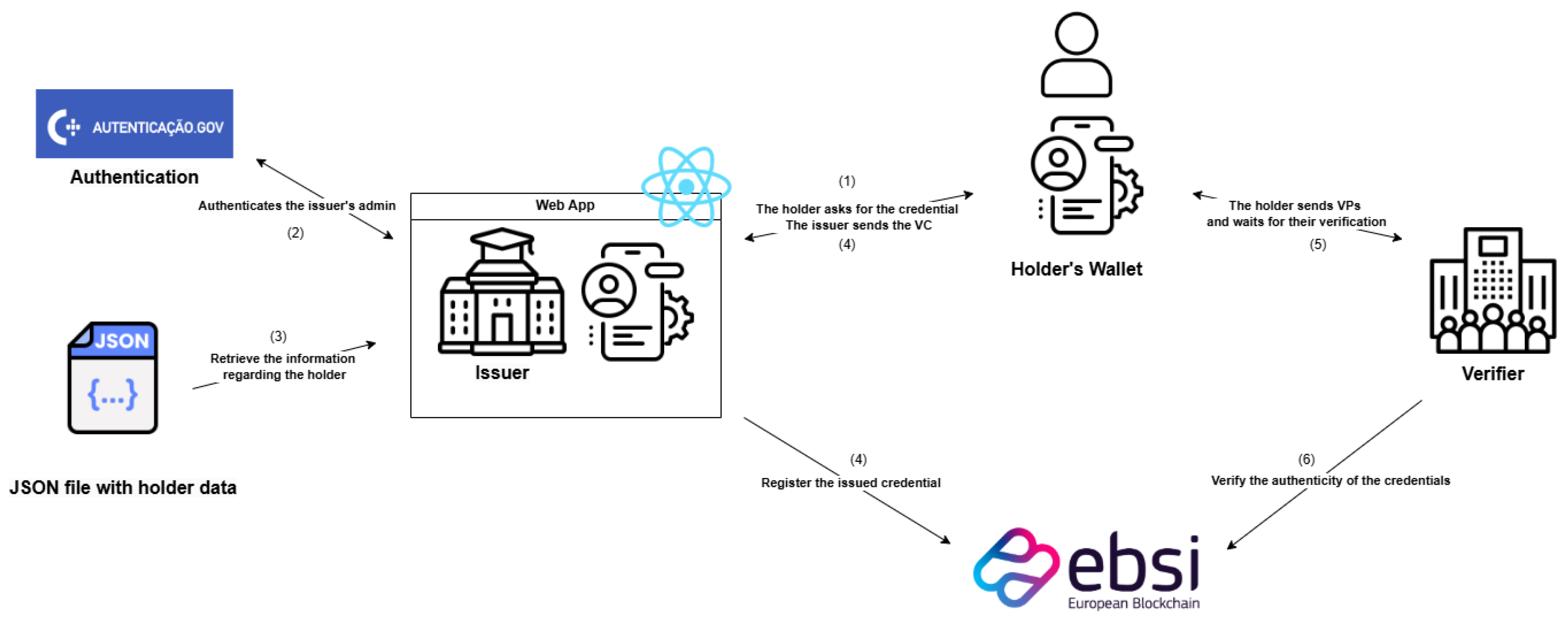

The proposed architecture was designed to address key concerns of security, standardization and usability with the objective of creating a robust blockchain-based system.

Figure 2 depicts the proposal. The architecture was built with five core insights, from the literature, in mind. First, we use EBSI and W3C Verifiable Credentials (VCs) to ensure compliance with data standardization, enabling credential recognition across institutions and national borders, providing students with portable qualifications. Secondly, a comprehensive trust chain is established with strict institutional onboarding processes. These measures ensure system wide security and reliability by allowing only authorized education institutions to access the system, thereby safeguarding the trustworthiness of the issuing process. The third architectural choice was the automation of the credential creation process where a data uploading mechanism was implemented, removing manual data handling and the probability of human error. This addresses scalability issues regarding the integration with institutional information systems, allowing this system to be used in several different HEIs in a straightforward manner. The fourth core insight was the use of digital wallets for credential storage, which enables Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) principles, allowing students to have full control over their data and to selectively disclose it, sharing only the necessary data. Lastly, QR code technology was incorporated for a streamlined verification process. Nowadays, any regular smartphone has the capability of scanning QR codes, therefore significantly enhancing the accessibility of our system for all stakeholders, requiring no specialized hardware or expertise.

A clearly defined workflow is followed, detailed in

Figure 2 by the sequence numbers: it starts when a student, having completed their academic path, submits a diploma request (1), which will trigger the start of the credential issuance process. Upon being notified, the designated HEI administrator accesses the web platform, through the governmental authentication mechanism (2), ensuring proper identity verification, and proceeds with the credential creation procedure. To create the credential, the necessary data needs to be retrieved from the institutional system and then uploaded to the platform (3), which will then be automatically packaged into a VC and issued (4). Concurrently, the cryptographic hash of the credential is stored in the EBSI ledger (4), and the complete credential is sent to the student’s account, allowing the student to retrieve the credential with it’s digital wallet (4). Whenever a student needs to share or present their academic certifications, they can share the credential with the requesting entity (5), who can instantly verify its authenticity, with a simple scan of the QR code (6).

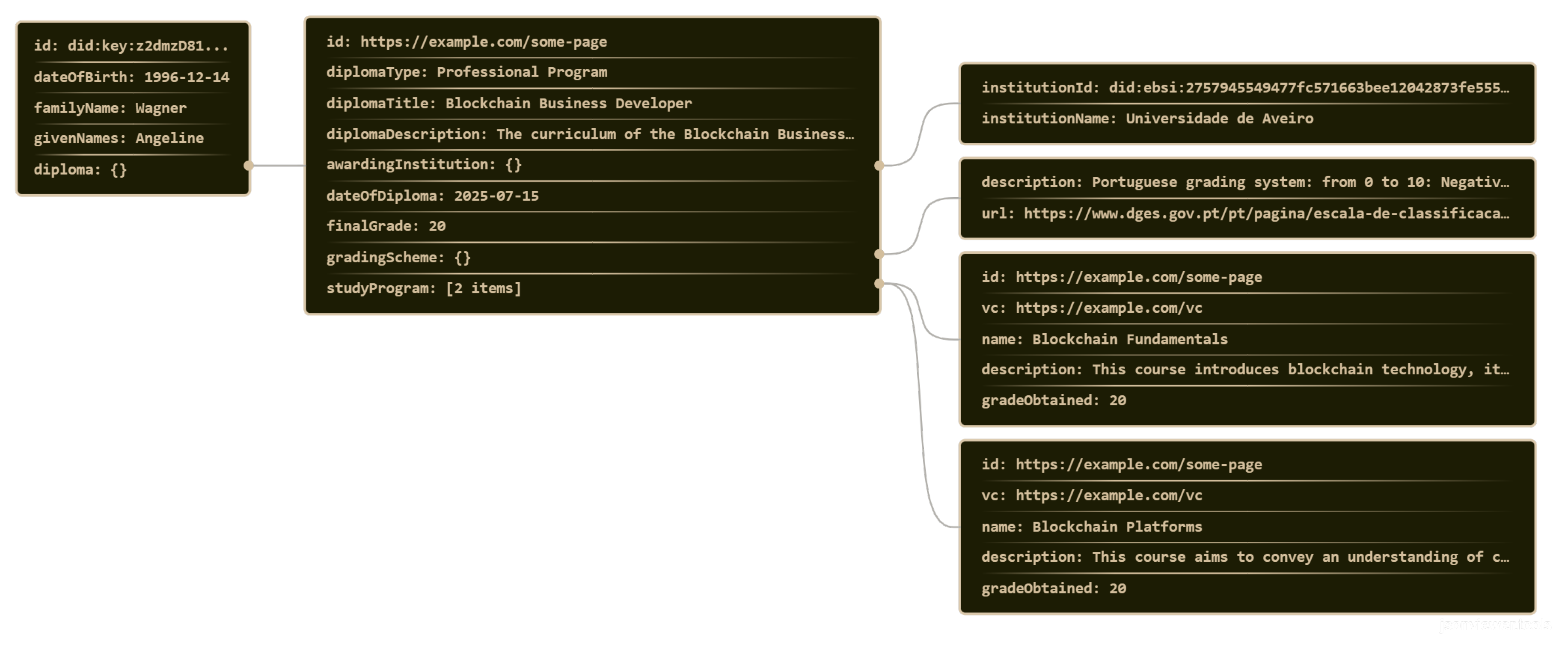

3.1.3. Data Model

A Verifiable Credential (VC) data model was developed to encapsulate the data required to represent a educational certification credential issued by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), in a standardized format. It follows the EBSI Verifiable Credential Data Model 1.1 specification, ensuring interoperability across the European blockchain ecosystem. Named “Edufiable Educational Verifiable Credential”, this data model is built upon the standard EBSI Verifiable Attestation schema, extending it and adding the necessary attributes to address the use case specific requirements, achieving both standardization compliance and domain specific functionality. This data model serves a dual purpose: it can represent both individual courses (such as micro-credentials) and complete educational programs, providing a comprehensive digital attestation of a student’s achievements. The model is specifically designed to handle the hierarchical structures of educational certifications, where a complete program comprises multiple individual modules.

In order for this data model to be usable in EBSI’s environments, it needed to be approved by EBSI’s Support Office and registered in the Trusted Schema Registry

1

The data model has two main classes: the “

issuer” class, which identifies the entity that issued the credential, containing the Decentralized Identifier (DID) and, optionally, the name of the issuing institution, and the “

credentialSubject” class, exemplified in

Figure 3, which details the information about the holder of the credential, including both personal information and information regarding the certification being attested. The “

credentialSubject” class has, among other attributes, a sub-class named “

diploma”, which details all the information regarding the educational certification, through a few sub-classes and attributes: the “

awardingInstitution” class, which details the institution that awarded the diploma, identified by its DID and name; the “

gradingScheme” class, which identifies the grading system used to attribute the grades, identified by a

URL to the grading system definition and a brief description; the attributes encompass the title, the type, the issuance date, the final grade obtained and a brief description of the diploma; lastly, there is an optional class that makes the distinction between the two usages of this data model, the “

studyProgram” class. Whenever this class is omitted from the final credential, it means that the credential represents a single course or module; however, when it is present, it details the entirety of the modules that comprise the study program, with each module having a

URL to its specification, a reference of the VC previously issued for said module, the module name, a brief description and the grade obtained.

The implementation of this data model serves as a cornerstone of the framework, enabling secure, verifiable and interoperable digital diplomas not only across the national educational ecosystem but also in cross-border domains.

3.2. Implementation

This chapter presents the implementation details of the credential issuance and verification framework using the European Blockchain Service Infrastructure. The implementation phase followed the architectural proposal, outlined in the previous section, as closely as possible, translating theoretical conceptualization into functional software, while accommodating some necessary practical adjustments.

The original architecture proposed a comprehensive trust chain involving governmental entities that consolidated the trust of the issuance process. Due to the significant administrative and bureaucratic challenges associated with integrating governmental bodies into the system, the trust chain implementation was adapted to focus on a more achievable scope.

3.2.1. Technological Stack

When it comes to frontend development,

Next.js, a React framework that enables server-side rendering, was used alongside

TypeScript, providing strong typing, enhancing code quality and maintainability, and

Tailwind CSS, for rapid UI development and consistent design patterns. This frontend stack improves performance and search engine optimization, while providing an overall better developer experience.

For the backend development, we used

Node.js, a JavaScript runtime environment that provides an event-driven non-blocking Input/Output model, making it a lightweight and efficient framework for server development. There was also the necessity to use a database for data persistence, therefore choosing to use

PostgreSQL, an open-source relational database system to store user information, managing role-based access control, and storing credential hashes, allowing the registered students to have a backup of their credential.

As for the digital wallet, the solution provided by

Triveria was chosen. This solution provides a SDK that facilities integration with our core system; a full-featured mobile wallet, that enables selective disclosure for holders; offers comprehensive processes for trust chain creation, through the SDK; and allows the platform to be able to create wallets, onboard and accredit wallets, issue and verify credentials, all without having to use multiple solutions. Integration with EBSI was achieved entirely through the Triveria SDK, which encapsulated the complexity of blockchain interactions and cryptographic operations, offering a streamlined approach to implementing EBSI-compliant credential issuance and verification processes.

Additionally,

Docker and Docker Compose were use for containerization, ensuring consistent environments, and version control was provided by Git and

GitLab, tracking code changes.

3.2.2. Application Demonstration

The following section presents implementation details supplemented by screenshots of the developed application, demonstrating the implemented functionalities. The discussion begins with the authentication mechanisms, covering both traditional authentication and citizen card-based authentication. Next, the trust chain creation process is detailed, followed by the credential issuance flow and the claiming process for these credentials. Finally, the verification process is then examined.

Authentication

This application leverages two different authentication mechanisms, each for its specific group of users. The traditional authentication based on email and password is dedicated for students, who can create their own accounts, providing their email, password and DID. The citizen card authentication is destined for the use of institutional users, that hold a role in the trust chain, therefore needing a more secure authentication method.

The citizen card-based authentication leverages PKCS#11 standards and the Portuguese eID infrastructure, which provide functionalities to safely extract the authentication certificate from the citizen card. The system scans the host in search of a connected smartcard reader interface and, once one is found, it looks through the scanned card, searching for the authentication certificate. Once retrieved, the system parses the certificate extracts the card’s identification number. Having acquired the card’s identification number, the system will look through the database looking for a registered and validated account with the same identification number. This authentication mechanism is not a viable solution due to being an outdated mechanism and, mainly, due to the way it was implemented, as it was developed as a backend module, instead of being a client-side solution, which means it only works locally. This was done in an effort to implement a proof-of-concept of the system without engaging in the extensive bureaucracy that comes with using government-owned systems.

In the traditional authentication mechanism, using email and password, the user is required to create an account to be able to access the application. The user accesses the registration page, which prompts the user to insert the necessary data. In order to facilitate the input of the DID, a feature was implemented were the user can automatically submit its DID by scanning the QR code and accepting the request with its digital wallet. Having successfully created the user account, an email will be sent to the user, with a link that will allow them to verify its account. It is only possible to sign in to the platform after verifying the account. Account verification needs to be carried by all users.

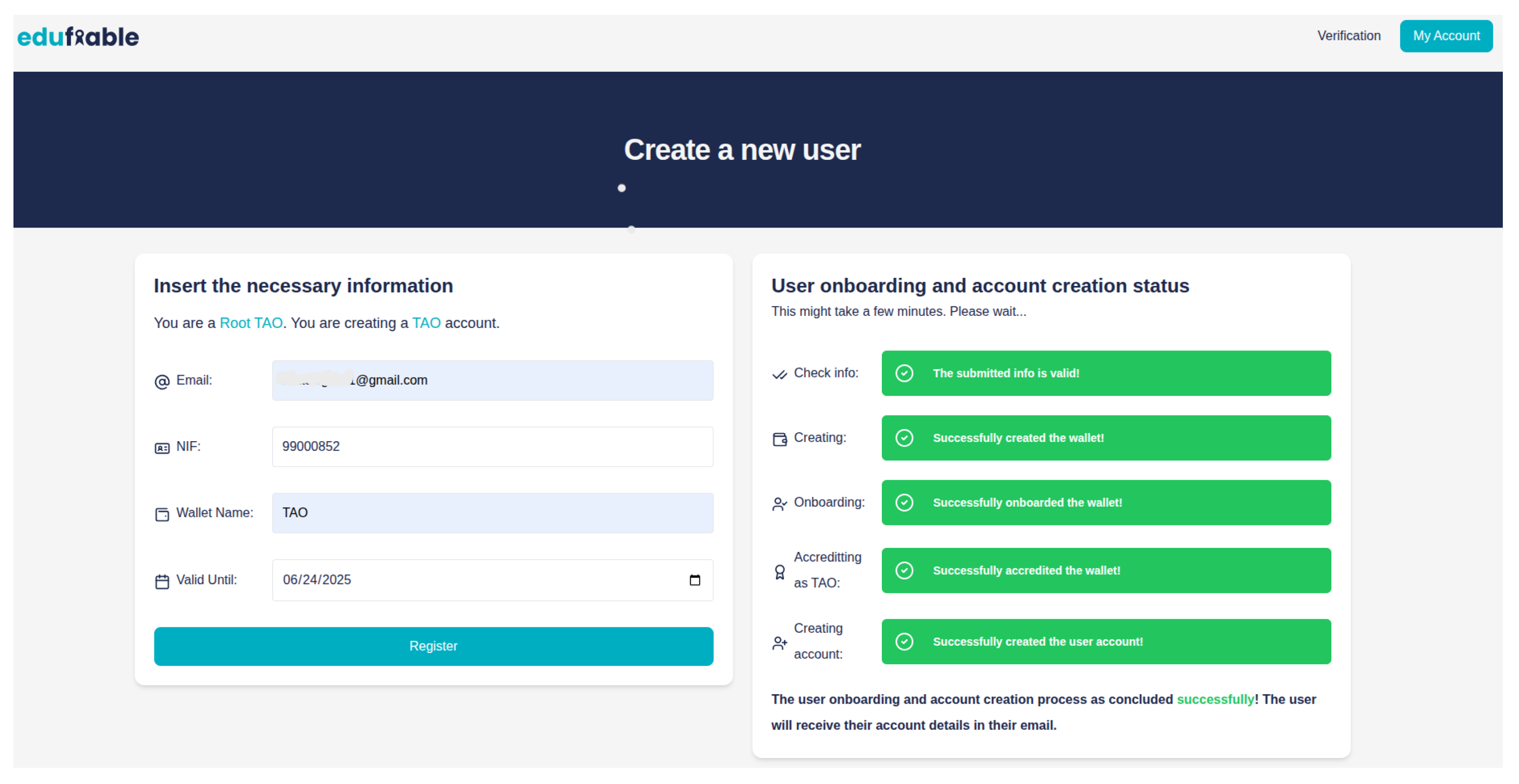

Trust Chain Creation

The process of creating the trust chain, and consequentially creating the institutional user’s accounts, is locked behind the role-based access imposed by the application, to which only the users accredited has Root TAO or TAO have access to, although having different objectives. The API endpoints are also protect by role-based access rules, only processing requests by either the users accredited has Root TAO or TAO. The Root TAO, who oversees the whole system, already has its account and wallet pre-configured in the system, but the TAO and TI need to have their accounts created by the user hierarchically superior.

The Root TAO user logs in and accesses the “Create User” page and inputs the necessary data into the form. Upon submitting the requested information, a new column will appear on the right side, which will show information about the different stages of the process.

Figure 4 shows the successful completion of the process.

In the backend, this process starts by checking if the submitted information is valid, checking if any other registered account has the same values, in order to avoid collisions. Upon confirming the info is valid, a wallet is created, using the submitted wallet name, and specifying what are its capabilities, either a issuer or verifier, or even both. This is powered by the Triveria’s SDK, which will create a new digital wallet, generating a valid DID and creating its DID document, that will be used in the next step, which consists in onboarding the newly created DID into the trust chain. It is also necessary to define the credentials that this wallet will be able to create in the future, and the EBSI’s configurations. This is done by creating credential templates, where several properties are defined, such as the name, type, and disclosable fields of the credential, and by defining the EBSI’s environment configurations, in which the wallet is valid. Each wallet can hold several credential templates. However, in this application, the wallets are created with a single template, defined accordingly with the data model specified in

Section 3.1.

The onboarding process consists of several steps, involving both the new wallet and the creator’s (either the Root TAO user or the TAO user) wallet: first the new wallet is notified, by the creator’s wallet, that it will be onboarded into the trust chain, which will trigger the wallet to prepare its DID; secondly, the creator’s wallet will issue a “VerifiableAuhtorizationToOnboard” to the new wallet which, for the sake of automation, will be promptly accepted; finally, being in possession of a “VerifiableAuhtorizationToOnboard”, the new wallet will trigger the onboarding onto the trust chain, therefore being officially recognized as a member of this specific trust chain.

However, the new wallet still has no role in the trust chain, in spite of already belonging to it. The accreditation process serves precisely to attribute a role to the new wallet. The onboarding process and the accreditation process follow a similar sequence, starting by having the creator’s wallet notify the newly onboarded wallet, this time that it will be accredited a role. In case of the Root TAO user being the one who’s accrediting another user, the Root TAO wallet will issue a “VerifiableAccreditationToAccredit” credential, signaling that it has been authorized to take on the role of TAO, to the new wallet. On the other hand, if the process was triggered by a TAO user, the TAO wallet will issue a “VerifiableAccreditationToAttest” credential, signaling that it has been authorized to take on the role of TI, to the new wallet. Again, for the sake of automation, the credential will be automatically accepted. Finally, upon having received either of the previously mentioned credentials, the new wallet will trigger the accrediting of the role, being formally recognized as either a TAO or a TI in the trust chain.

Finally, upon having a wallet properly onboarded and accredited, the user account will be created and registered in the database, storing the hashed citizen card identification number complying with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and a email will be sent to the new user, with the verification link.

In this proof-of-concept, any entity can be onboarded into the trust chain, but in a production-ready implementation, strict legal processes need to be created to ensure that only legitimate governmental entities and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) take part in the trust chain, that being the only way to ensure the credibility of the credentials.

Issuing and claiming a credential

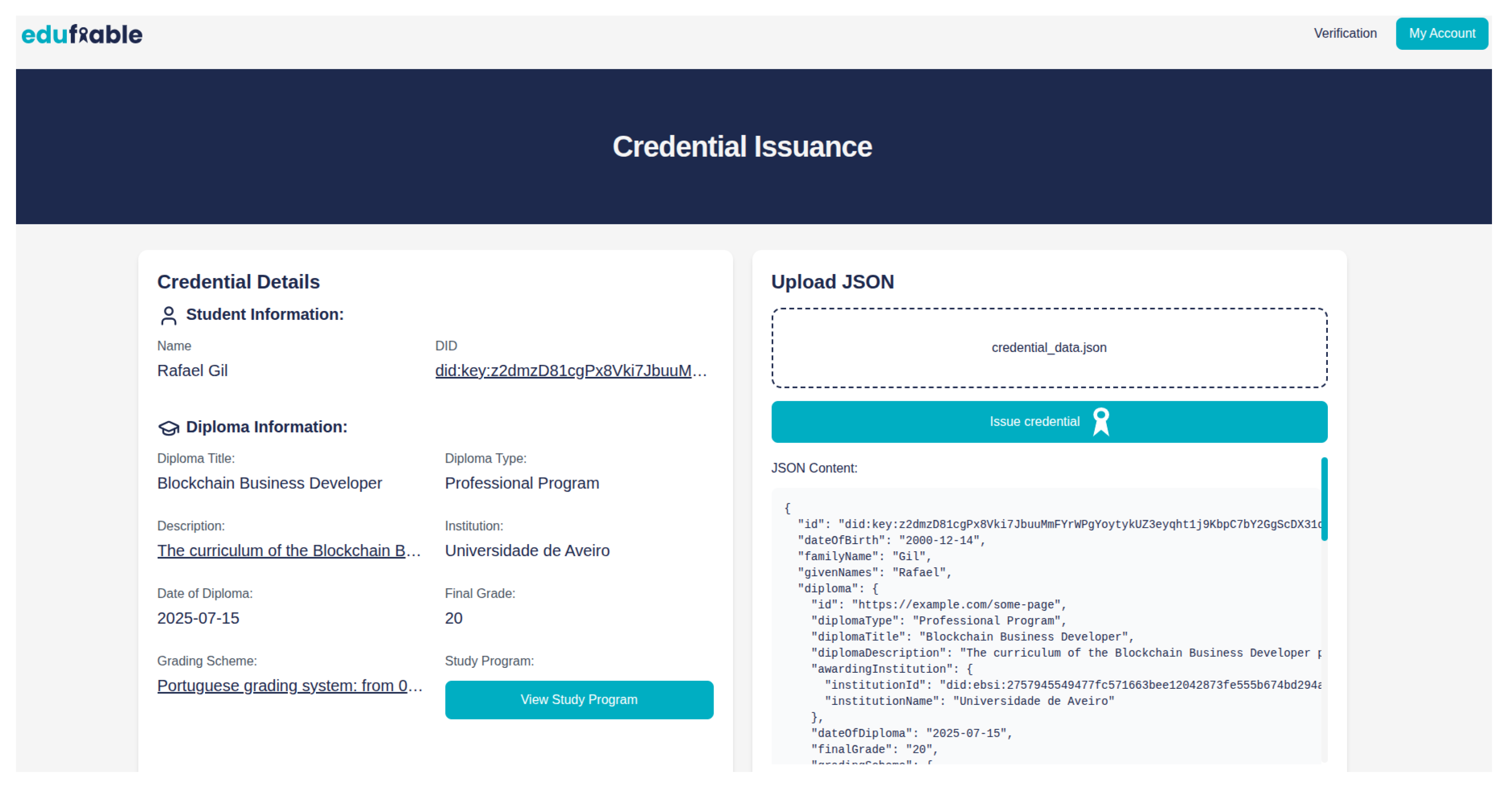

Upon having its account created, the TI user will have access to the dedicated issuance page, where it is be possible to issue credentials for the students of the institution they represent. The issuance process followed closely the proposed architecture both by utilizing a file upload mechanism and using the custom data model. The user starts the issuance process by getting the appropriate data, regarding a specific student, and uploading it to the platform, which only accepts JSON files.

Having uploaded the file, the data will be displayed in the left column (

Figure 5), facilitating the TI user work of verifying if the data is correct before issuing the credential. Having verified the data, the user submits it, triggering the issuance process. The issuance request will be received by the backend that will, first of all, verify if the request came from a registered and authorized user. Having confirmed it, the system will process the file, verifying if the data meets the required data model and if every mandatory field is properly filled. Upon the dating being verified, the system will check if the DID present in the file matches with the did of any of the registered student accounts. Finally, after the verifications are done, the data is ready to be packaged into a proper Verifiable Credential.

The data is packaged into a payload, respecting proper VC structure, and is matched against the data model registered in EBSI’s Trusted Schema Registry. If it matches, the credential issuance flow will create a credential draft, using it to generate a credential offer and acceptance code. Having concluded this step, all the necessary data will be stored on the database and a success message will be sent to the TI user, with the offer URI and PIN code. Even though it is not necessary, these can be sent to the student so that they can claim the credential.

It is important to notice that the credential can only be claimed by the wallet with the DID matching the DID bound to the credential.

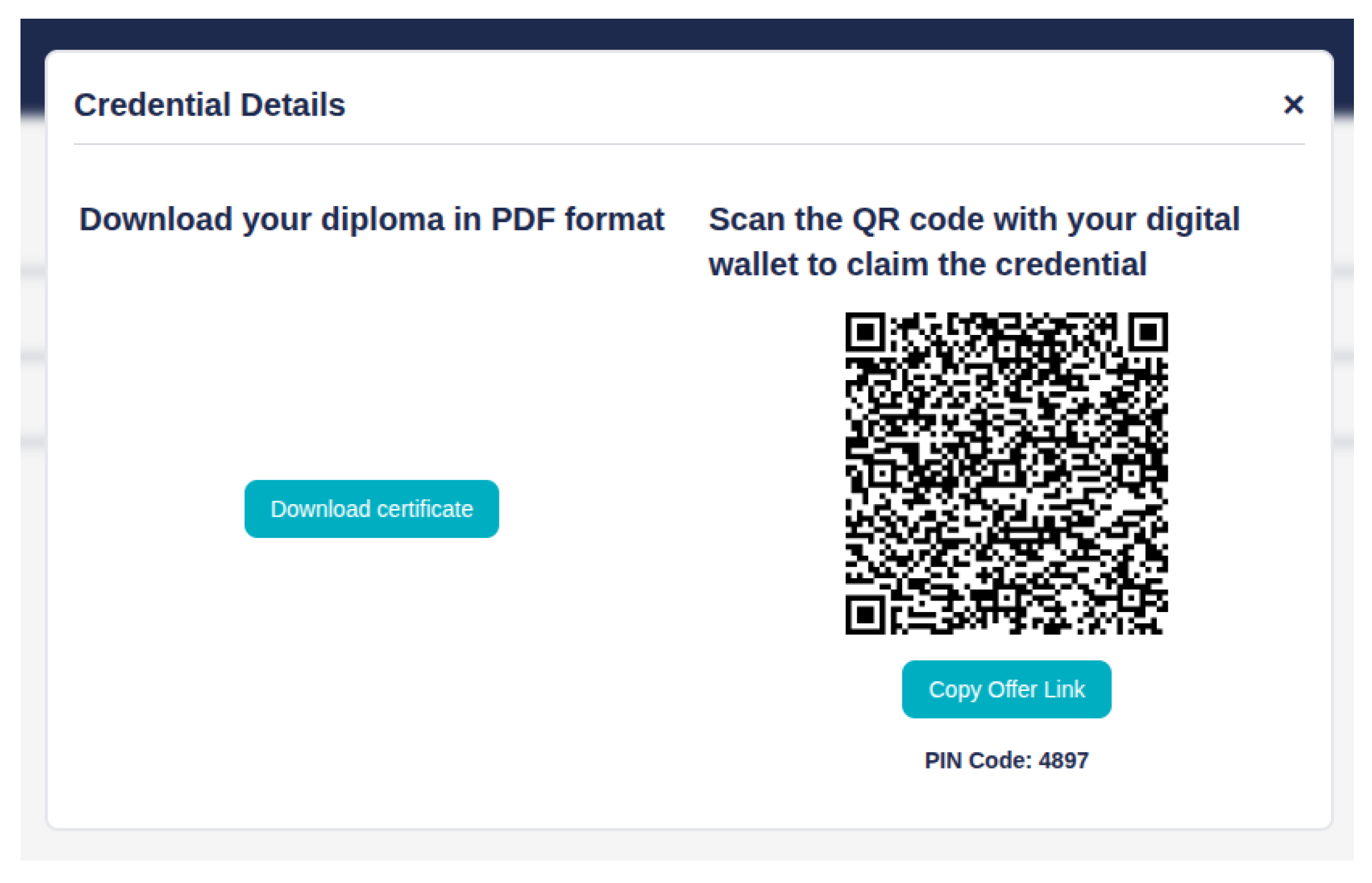

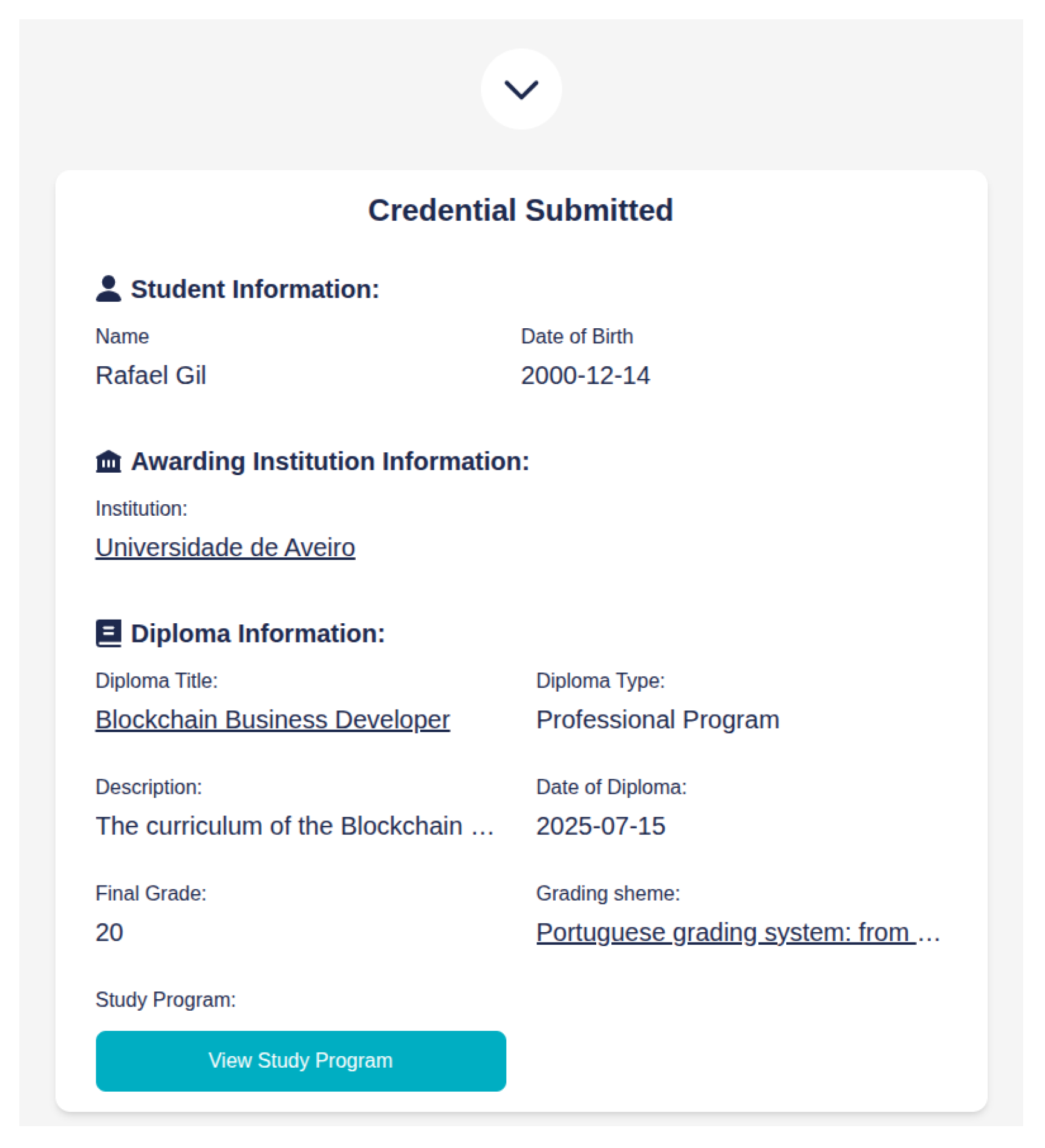

Now, having issued the credential offer, the student has to claim it with its wallet. For that, it is necessary to login into the platform and access the “My Credentials” page. After accessing the “My Credentials” page, the user will be met with a table, listing all the credentials attributed to them. Upon clicking an entry in the credentials table, a modal will open up, showing a button to download the PDF certificate and the QR code of the credential offer, seen in

Figure 6. Scanning the QR code with the mobile digital wallet, will prompt the user to insert the PIN code, exemplified in

Figure 7. After accepting the credential, it will be available in the student’s digital wallet, ready to be consulted. Having claimed the credential, the issuance process is concluded.

Verifying a Credential

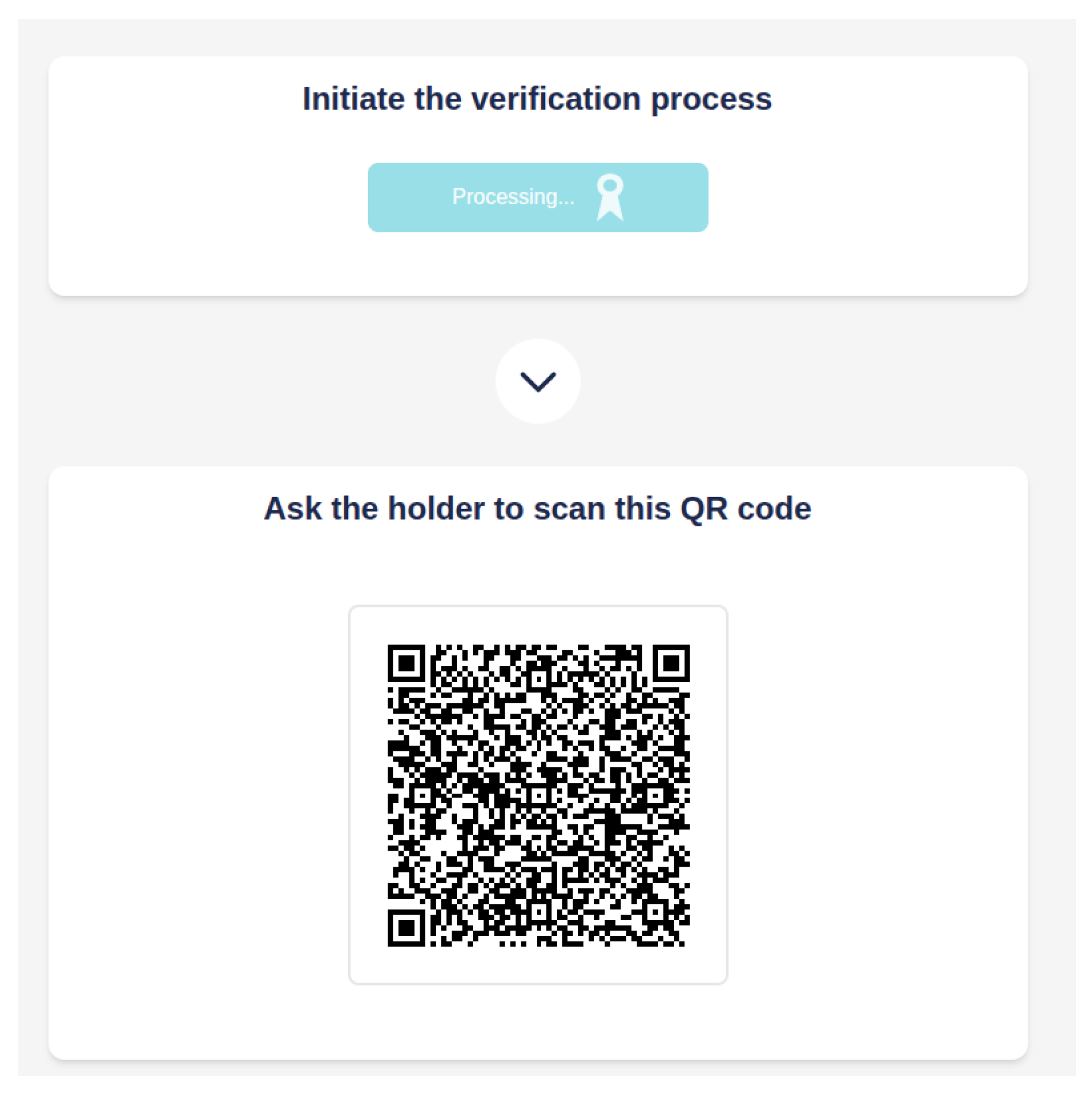

The verification process is accessible by every user, even those who are not logged in. This approach enables every user to straightforwardly verify a credential. This process involves several steps and, once again, a digital wallet. Only credentials that meet the data model specified in

Section 3.1 can be verified with this mechanism.

When users enter the the “Verification” page, they will be met with an action item that allows them to initiate the verification process, seen in

Figure 8. The verification process starts by creating a new wallet, with a randomly generated name to avoid collisions with other wallets. This way, each instance of the verification process will have its own individual wallet. This wallet will be delete when the verification process ends. Similarly with the wallets created during the trust chain creation process, these also need to be properly configured, stating its capabilities, in this case a verifier wallet, defining EBSI’s environment configurations and, most importantly, the credential templates. These templates differ greatly from the ones created for the issuer wallets, as these are intended for Verifiable Presentations (VPs). The template specifies what is the type of the credential it wants to check, in this instance enabling the wallet to only be able to verify credentials that meet the custom data model.

Having created the wallet, it will be used to create a request for presentation, generating an offer URI. This URI will be sent to the frontend, where a QR code will be generated (

Figure 8), ready for the student to scan and present its credentials.

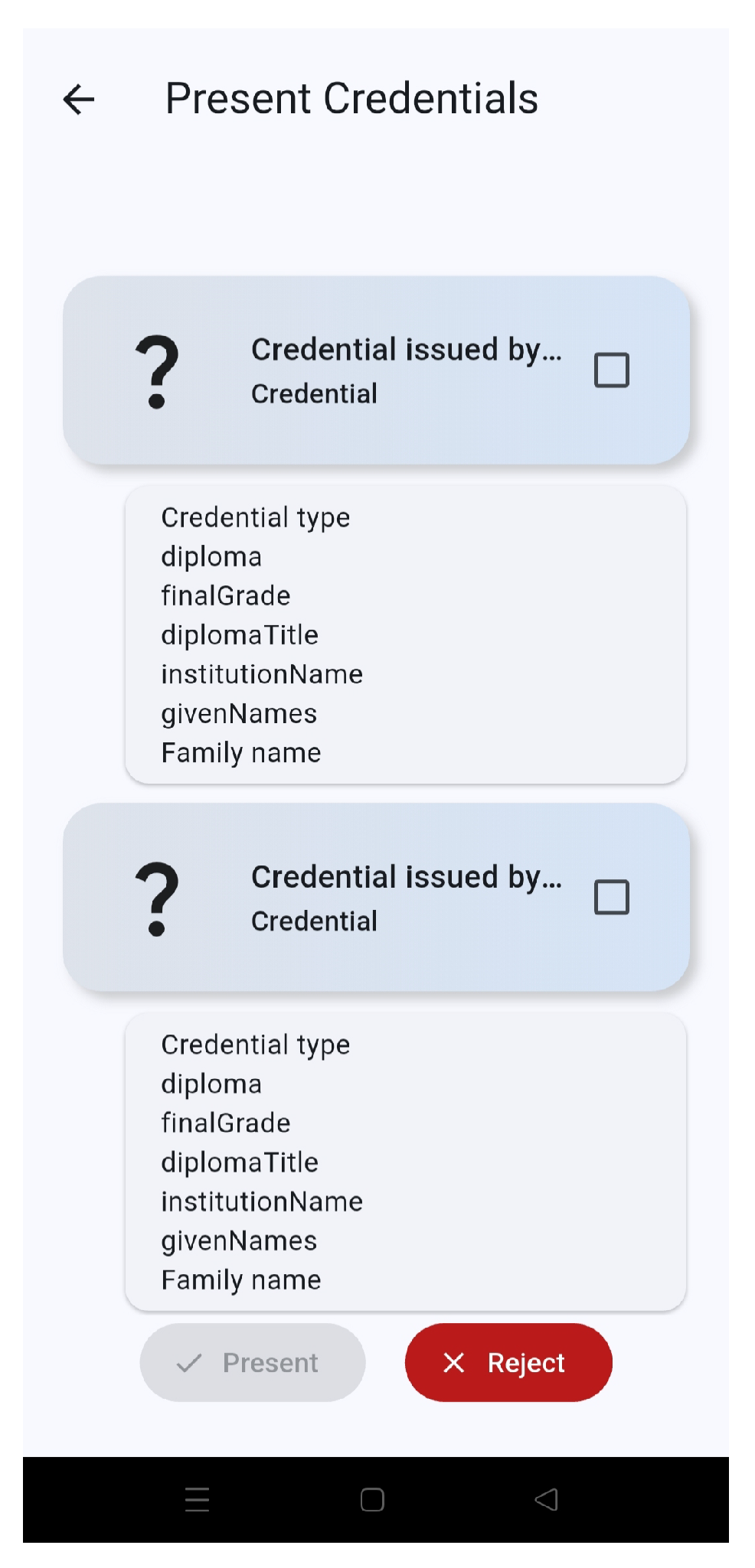

The student, after scanning the QR code with its wallet, will be presented with a list of credentials, that match the type requested by the verifier, from among all the credentials stored in its own wallet. The student chooses which one they want to share and sends it to the verifier. The chosen credential will be package into a VP and received by the verifier wallet.

After receiving the VP, the credential’s data will be displayed (

Figure 10). The verification of the credential happens in the background of the verifier wallet, where the validity of both the credential and the trust chain will be verified. Once the credential is verified and the data presented, the verifier wallet, previously created, will be automatically deleted.

3.3. Evaluation

The evaluation of software applications requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses multiple dimensions of quality, including security, performance and scalability. This chapter presents a thorough evaluation of the developed application using open-source tools. The evaluation strategy employed three distinct testing approaches: security vulnerability using OWASP ZAP, performance stress testing through Grafana k6, and runtime performance analysis using Clinic.js Doctor.

All the following tests were carried in the development environment, as the system is still not ready for production, missing some essential features. These tests provide baseline metrics for optimization efforts, aid in identifying potential problems before they become too expensive to resolve in production, provide architectural insights facilitating the identification of performance patterns and enable immediate debugging. Further testing will be required, specifically in a production environment, as the results may differ greatly from the ones presented in this chapter, due to development overhead.

3.3.1. Security Assessment

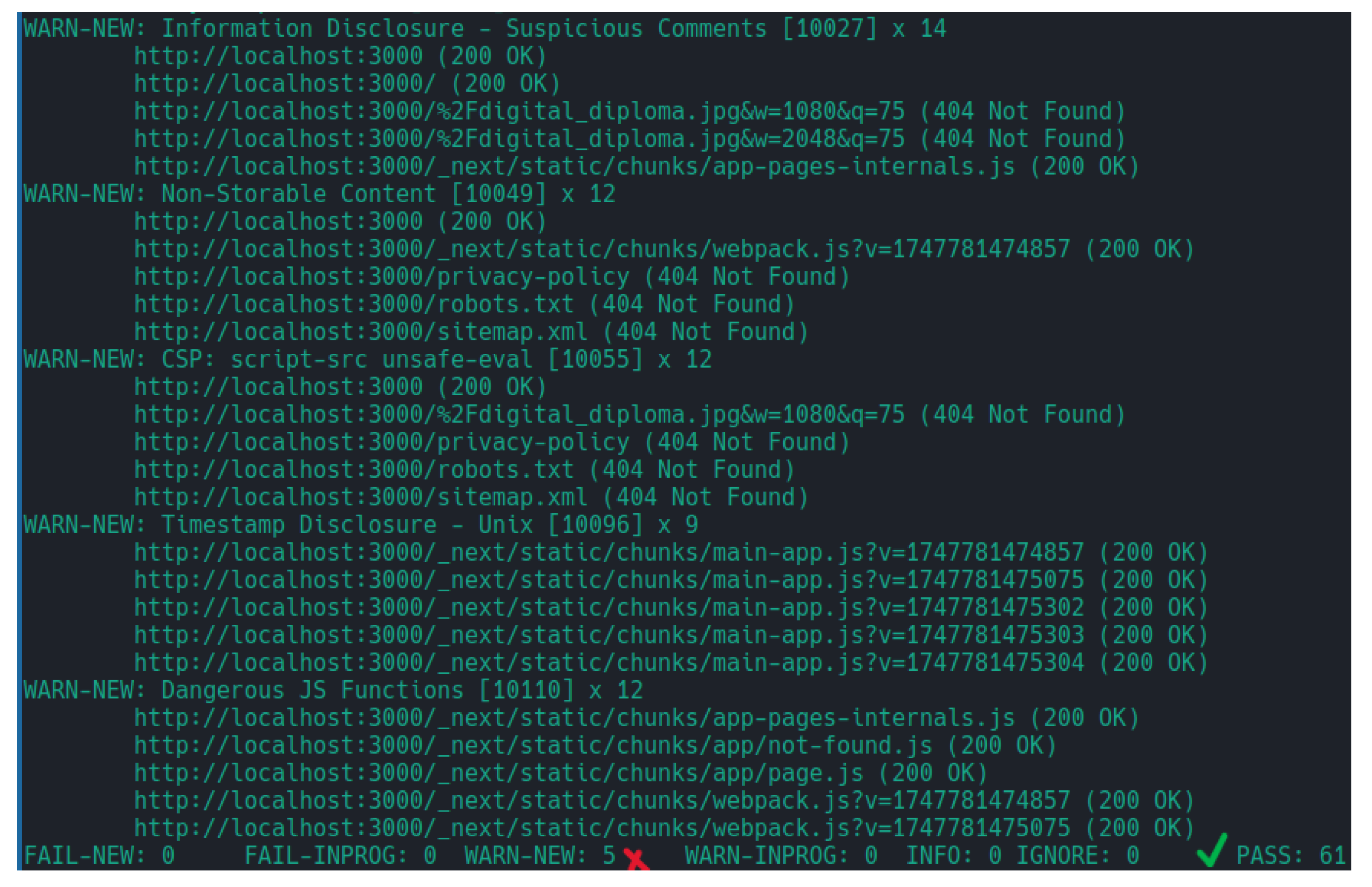

The OWASP ZAP security assessment demonstrated a relatively positive outlook for the application. The automated scan was successfully completed with minimal findings, indicating that fundamental security concerns were properly accounted for during the development of the application. The scan identified several categories of potential security issues, but the overall risk profile was not worrying. The scan results, seen in

Figure 11, show that no critical security flaw was identified, passing 61 of the security tests. However, 5 warnings, representing low to middle-level security concerns, were identified. Several of the identified issues, were detected in the static files, generated automatically by Next.js, inside the

folder, each time the project is built, therefore not being able to accurately resolve them. For this reason, these warnings were ignored, as they were likely to be false positives.

The assessment revealed warnings related to information disclosure. While these do not represent an immediate security risk, they could potentially provide attackers with information about the application architecture or implementation details. The presence of non-storable content warnings suggests that certain responses do not have the appropriate cache-control headers in place, making it possible that sensitive information be wrongfully cached by browsers. CSP warnings indicate that client-side security controls are not as strict as they could potentially be, as the presence of violations indicates that the application might allow the execution of code through , facilitating Cross-site Scripting (XSS) attacks. However, the absence of high-severity errors indicates that critical security risks, such as SQL injection, authentication bypasses or session management flaws were not detected.

3.3.2. Performance Analysis

Performance analysis is a critical aspect of software development that ensures applications can handle real-world usage scenarios effectively. This performance evaluation consists of two complementary methodologies: stress testing to evaluate scalability and load handling capabilities paired with runtime performance analysis to identify bottlenecks and resource consumption patterns.

Testing Environment Setup

All performance tests were conducted on a consistent hardware and software configuration to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The testing environment consisted of the following specifications:

-

Hardware Configuration:

- –

Processor: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-10870H CPU @ 2.20GHz 2.21 GHz

- –

Memory: 32.0 GB DDR4

- –

Storage: SSD 2T

-

Software Environment:

- –

Host Operating System: Linux Mint 21.3 Cinnamon

- –

Containerization: Docker with Docker Compose

- –

Testing Tools: Grafana k6, Clinic.js Doctor, Autocannon

Stress Testing

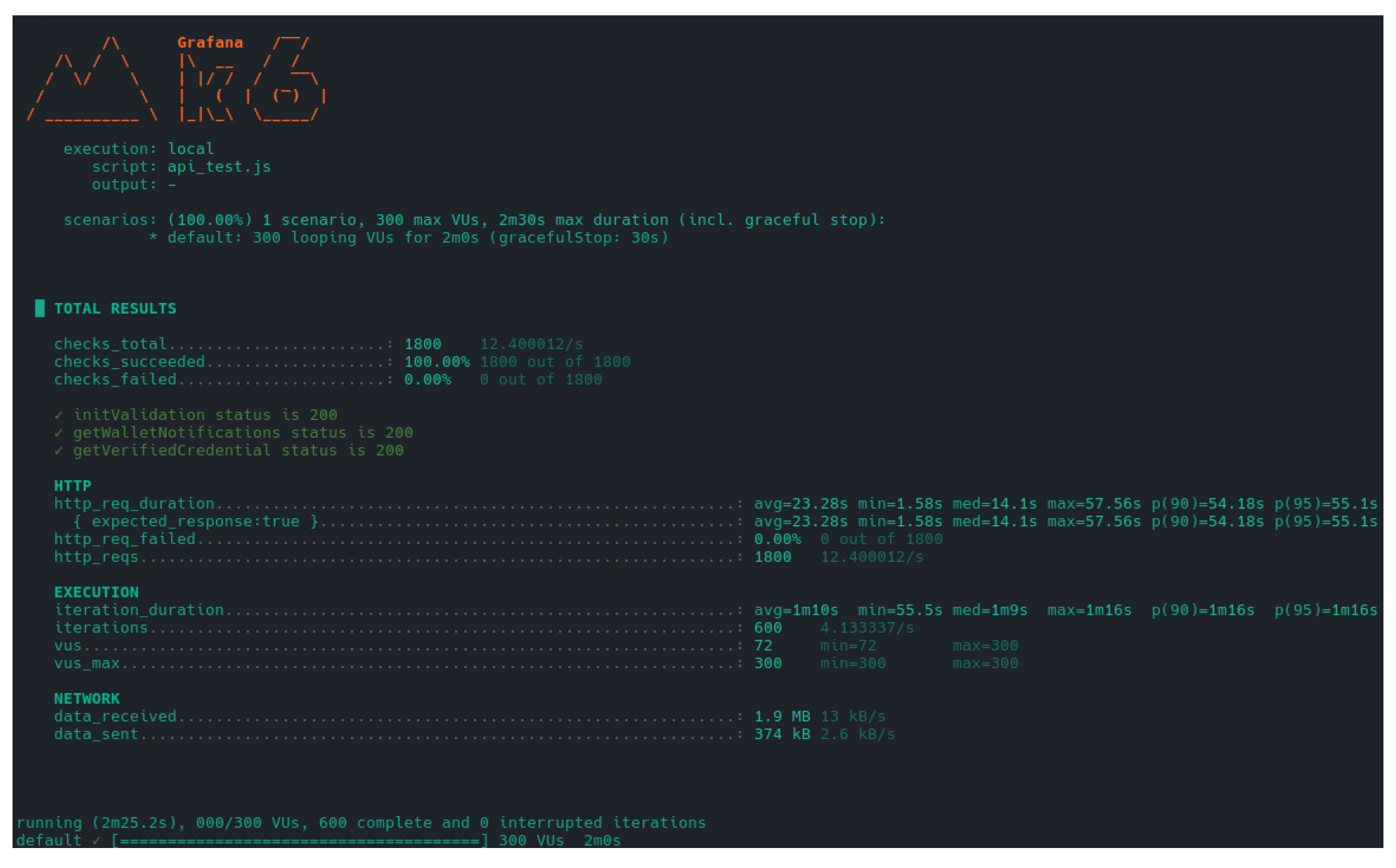

The tests were carried on the publicly accessible endpoints, namely all the endpoints in the credential validation process. The tests revealed overall good scalability characteristics, for every tested endpoint, seen in

Figure 12. The validation endpoints were tested with a total amount of 300 concurrent virtual users, as any more than that would result in failure due to the Triveria’s API rate limit, during a time period of 2:30 minutes. The results demonstrated excellent performance with 100% success rate across 1800 HTTP requests. However, the response times are high, with an average response time of 23.28 seconds and a 95th percentile response time of 55.1 seconds. Seeing that these endpoints carry operations dealing with asynchronous workflows and third-party interactions, these response times come as no surprise as their performance is bound to external factors, for the most part. Despite that, these results can be considered positive as the 95th percentile response time under 1 minute, for user validations using external third-party elements, such as digital wallets, is generally acceptable.

Runtime Analysis

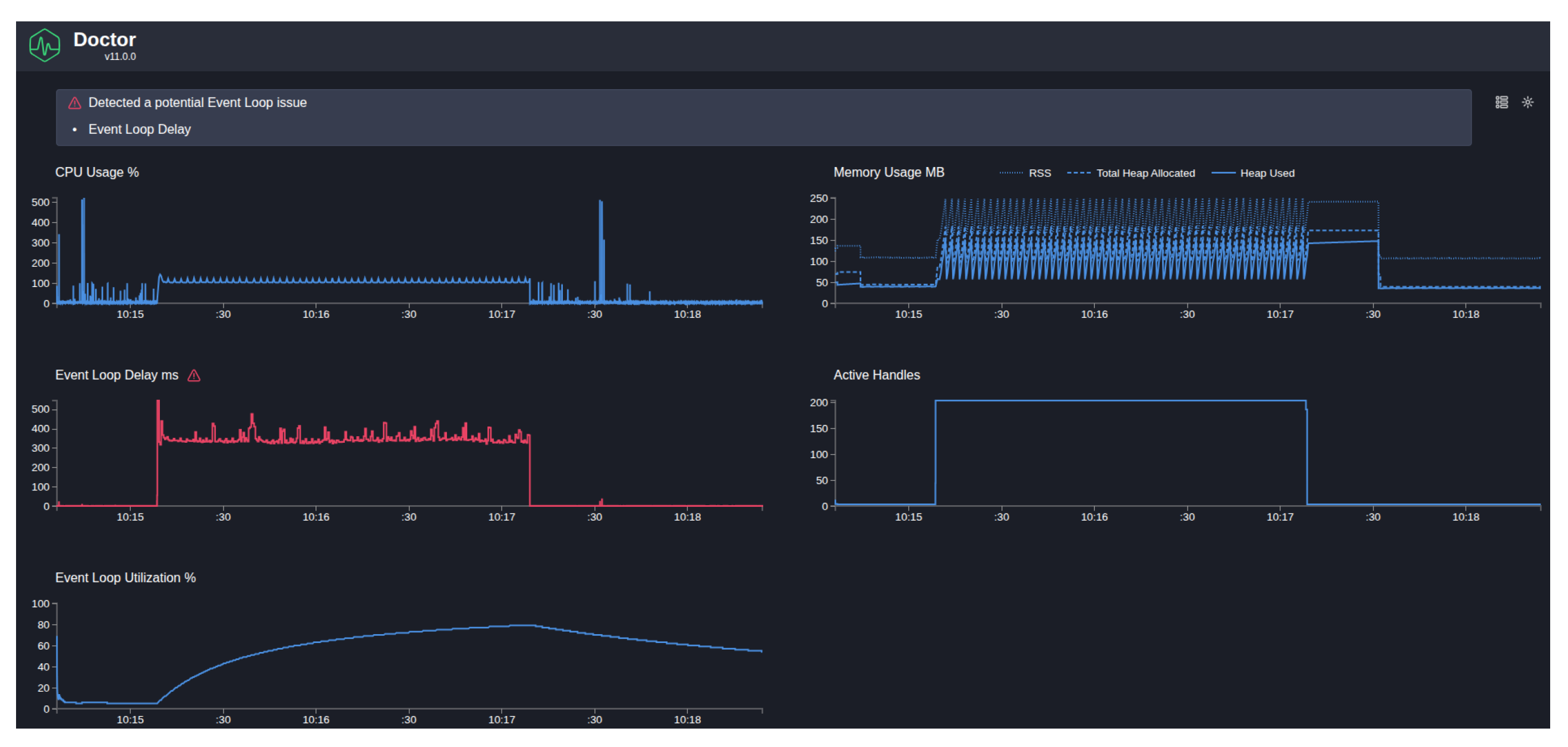

For the runtime performance analysis conducted, Autocannon was utilized, suggested by Clinic.js Doctor, as the load generation tool, configured to simulate 200 virtual users sending concurrent requests over a 2 minute time period. The analysis results, depicted in

Figure 13, revealed both strengths and weaknesses in the application’s performance. During the initial baseline phase, the system demonstrates optimal performance, with CPU utilization maintaining steady levels between 50-100%, memory consumption stabilized around 100MB, and event loop delays remaining within acceptable thresholds below 50 milliseconds, showcasing that the application is fundamentally sound under minimal load conditions. However, the load initiation phase exposes critical weaknesses in the system’s processing capabilities.

Upon the introduction of 200 concurrent connections, CPU utilization experiences a dramatic spike, indicating that some CPU intensive processes are consuming too many resources. More significantly, the event loop delay increasing to 500 milliseconds, representing a 10-fold performance degradation from baseline values, poses a particularly concerning issue, as in Node.js applications, event loop responsiveness is fundamental to the application’s non-blocking I/O architecture. During the sustained load phase, spanning approximately one minute of continuous high concurrency, the system exhibits concerning values even if within those of a functioning service, with CPU utilization stabilizing between 300 milliseconds to 400 milliseconds. Memory usage also showed concerning values, revealing a sawtooth configuration pattern, with rapid allocation and de-allocation cycles, suggesting frequent garbage collection events.

The immediate recovery observed upon halting the concurrent load, demonstrates that the performance degradation is directly correlated with concurrent processing, suggesting that the bottlenecks are operational rather that structural. The performance issues are most likely due to synchronous operations or CPU heavy computations being executed on the main event loop of the application.

4. Discussion

As stated in chapter 1, the objective of this work was the development of a blockchain-based solution for the issuance and verification of digital credentials to tackle the ever-growing problem of fake diplomas and credentials. This objective was accomplished, as the developed application allows the execution of all the involving processes, allowing for both the issuance and verification of credentials in a faster and much more straightforward way than traditional methods. Additionally, by registering a cryptographic hash of the credential onto the EBSI’s ledger, its validity is safeguarded, by ensuring that the data of the credential is not modified, otherwise the registered hash will not match, and by having a structured trust chain, the credential’s credibility can be ensured, minimizing the impact of fake credentials with no backing from trusted entities.

This implementation accommodates a few recommendations from the literature such as using Verifiable Credentials and digital wallets [

13], the automation of the processes of credential issuance suggested by [

18], removing human error, and QR code assisted mechanisms suggested by both [

19] and [

20], offering much faster and straightforward processes. This work addressed several of the challenges related in the literature. By using EBSI, legislative compliance with GDPR is ensured when dealing with student’s credential data. Using digital wallets, the system enables SSI principles, allowing the holder to control its data, choosing which info to disclose. The portability and interoperability of the credentials is also guaranteed by using standardized data models such as VCs, allowing not only cross-institution but also cross-border sharing and verification of credentials. EBSI also enables no fees during transactions, removing financial concerns during adoption and facilitating the scalability of the system, allowing more actors to participate in system. The file uploading mechanism, although not as efficient as the API gateway suggest by [

21], provides a way of interacting with legacy systems.

The conducted tests, reveal an application with a strong foundational architecture, but requiring focused improvements in specific areas. The security assessment demonstrates adequate protection against common vulnerabilities, while the stress testing shows good scalability capabilities. However, the runtime performance analysis highlights critical concerns requiring close attention. The strong load testing results show that the application’s foundational architecture can handle a significant amount of concurrent users, making identifying and resolving the event loop blocking operations the primary concern, as these delays significantly impact user experience and application responsiveness. The security assessment, while generally positive, suggests that some improvements to the Content Security Policy could enhance the overall security of the application.

One problem this work faces is ensuring decentralization, as having an entity that oversees the entire trust chain, with the authority of allowing other entities to participate in the system, compromises decentralization, meeting with the challenges faced by [

15]. However, this comes with greater control, necessary for critical systems, such as the one detailed.

The use of digital wallets and Verifiable Credentials are the factors that most differentiate the work presented from the literature, as they fundamentally shape how the system works, removing concerns with user privacy, enabling SSI and credential portability. The use of a strict trust chain, even if it ensures the trustability of the credentials, comes at the expense of decentralization.

As future work, there are a few minor details that still need to be addressed, but the most consequential are: implementing a viable authentication mechanism for institutional users , specifically an up-to-date mechanism compliant with eIDAS 2.0, to ensure the security of the system; addressing the scalability issues of the current verification process, due to the creation of a new wallet for each request, where future developments should focus on implementing a more efficient verification architecture, either employing a new authentication instance for verifiers, where they create their accounts and bound their wallet to said account, or by implementing support for the verifier’ individual wallet; and implementing features that support the revocation capabilities already made available in Verifiable Credentials, allowing Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to manage credential life cycles effectively

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rafael Gil; methodology, Rafael Gil; software, Rafael Gil; validation, Rafael Gil and Paulo Bartolomeu; formal analysis, Rafael Gil; investigation, Rafael Gil; resources, Rafael Gil; writing—original draft preparation, Rafael Gil; writing—review and editing, Rafael Gil and Paulo Bartolomeu; visualization, Rafael Gil; supervision, Paulo Bartolomeu and João Almeida; project administration, Paulo Bartolomeu and João Almeida; funding acquisition, Paulo Bartolomeu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by the European Union / Next Generation EU, through the Recovery and Resilience Programme (RRP) [Project “Decentralizing Portugal with Blockchain” (01/C05-i11/2024.PC644918095-00000033)]. This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project 10.54499/UIDB/50008/2020, with the DOI identifier,

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/50008/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 3.5 for the purposes of aiding the development process and analyzing test results. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HEI |

Higher Education Institution |

| EBSI |

European Blockchain Service Infrastructure |

| IPFS |

Interplanetary File System |

| VC |

Verifiable Credential |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| DID |

Decentralized Identifier |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| DAC |

Data Availability Committee |

| SSI |

Self-Sovereign Identity |

| NFT |

Non-Fungible Token |

| Root TAO |

Root Trusted Accreditation Organization |

| TAO |

Root Trusted Accreditation Organization |

| TI |

Trusted Issuer |

| VP |

Verifiable Presentation |

References

- Rustemi, A.; Dalipi, F.; Atanasovski, V.; Risteski, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Blockchain-Based Systems for Academic Certificate Verification, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Ahad, M.A.; Casalino, G. A comprehensive review of blockchain technology: Underlying principles and historical background with future challenges. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 9, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Sunny, F.A.; Hajek, P.; Munk, M.; Abedin, M.Z.; Satu, M.S.; Efat, M.I.A.; Islam, M.J. A Systematic Review of Blockchain Applications, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.; Burger, E. E-residency and blockchain. Computer Law and Security Review 2017, 33, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, E.; Novack, J. How Thousands Of Nurses Got Licensed With Fake Degrees. Forbes, 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/emmawhitford/2023/02/21/how-thousands-of-nurses-got-licensed-with-fake-degrees/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Introducing EBSI, 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/sites/display/EBSI/Home (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Digital single market for Europe, 2024. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-single-market/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, 2020. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/.

- Saleh, O.S.; Ghazali, O.; Idris, N.B. A New Decentralized Certification Verification Privacy Control Protocol. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Cyber Resilience Conference, CRC 2021. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 1 2021. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Shaikh, A.A.; Bourouis, S.; Mamlouk, A.M.; Alshazly, H. Educational Blockchain: A Secure Degree Attestation and Verification Traceability Architecture for Higher Education Commission. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahlil, T.; Gomasta, S.S.; Ali, A.B. AlgoCert: Adopt Non-transferable NFT for the Issuance and Verification of Educational Certificates using Algorand Blockchain. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering, CSDE 2022. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kiiskilä, P.; Hylli, O.; Pirkkalainen, H. HOW CAN EUROPEAN BLOCKCHAIN SERVICES INFRASTRUCTURE BE USED FOR MANAGING EDUCATIONAL DIGITAL CREDENTIALS? In Proceedings of the 14th Scandinavian Conference on Information Systems, 2023, number 7.

- Nargis, T.; Salian, K.P.; Prathyakshini.; Vanajakshi, J.; Manasa, G.R.; Salian, S. A Secure Platform for Storing, Generating and Verifying Degree Certificates using Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics, ICOEI 2023 - Proceedings. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, pp. 532–536. [CrossRef]

- Serranito, D.; Vasconcelos, A.; Guerreiro, S.; Correia, M. Blockchain Ecosystem for Verifiable Qualifications. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd Conference on Blockchain Research & Applications for Innovative Networks and Services (BRAINS). IEEE, 9 2020, pp. 192–199. [CrossRef]

- Fekete, D.L.; Kiss, A. Toward Building Smart Contract-Based Higher Education Systems Using Zero-Knowledge Ethereum Virtual Machine. Electronics 2023, 12, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, P.V.F.; Huamán, C.Q.; Cangahuala, G.M.R.; Ochoa, J.E.D. BlockEP: A Blockchain Architecture to Record Academic Grades in the Peruvian Army. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the LACCEI international Multi-conference for Engineering, Education and Technology. Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ceke, D.; Kunosic, S. Smart Contracts as a diploma anti-forgery system in higher education - a pilot project. In Proceedings of the 2020 43rd International Convention on Information, Communication and Electronic Technology (MIPRO). IEEE, 9 2020, pp. 1662–1667. [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.S.; Priya, S.B. Trustworthy Blockchain Based Certificate Distribution for the Education System. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on Computer, Power and Communications, ICCPC 2022 - Proceedings. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 393–397. [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Kumar, H.A.; Lavu, S.; Reeja, S.R. Digital Degree Issuing and Verification Using Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Cognitive Computing and Information Processing, CCIP 2022. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sy, M.P.M.; Marasigan, R.I.; Festijo, E.D. EduCredPH: Towards a Permissioned Blockchain Network for Educational Credentials Verification System. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Conference on Information and Education Technology, ICIET 2024. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 434–439. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, R.; Éva Dobák, D.; Udvaros, J. Blockchain diploma authenticity verification system using smart contract technology. Annales Mathematicae et Informaticae 2023, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).