Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context

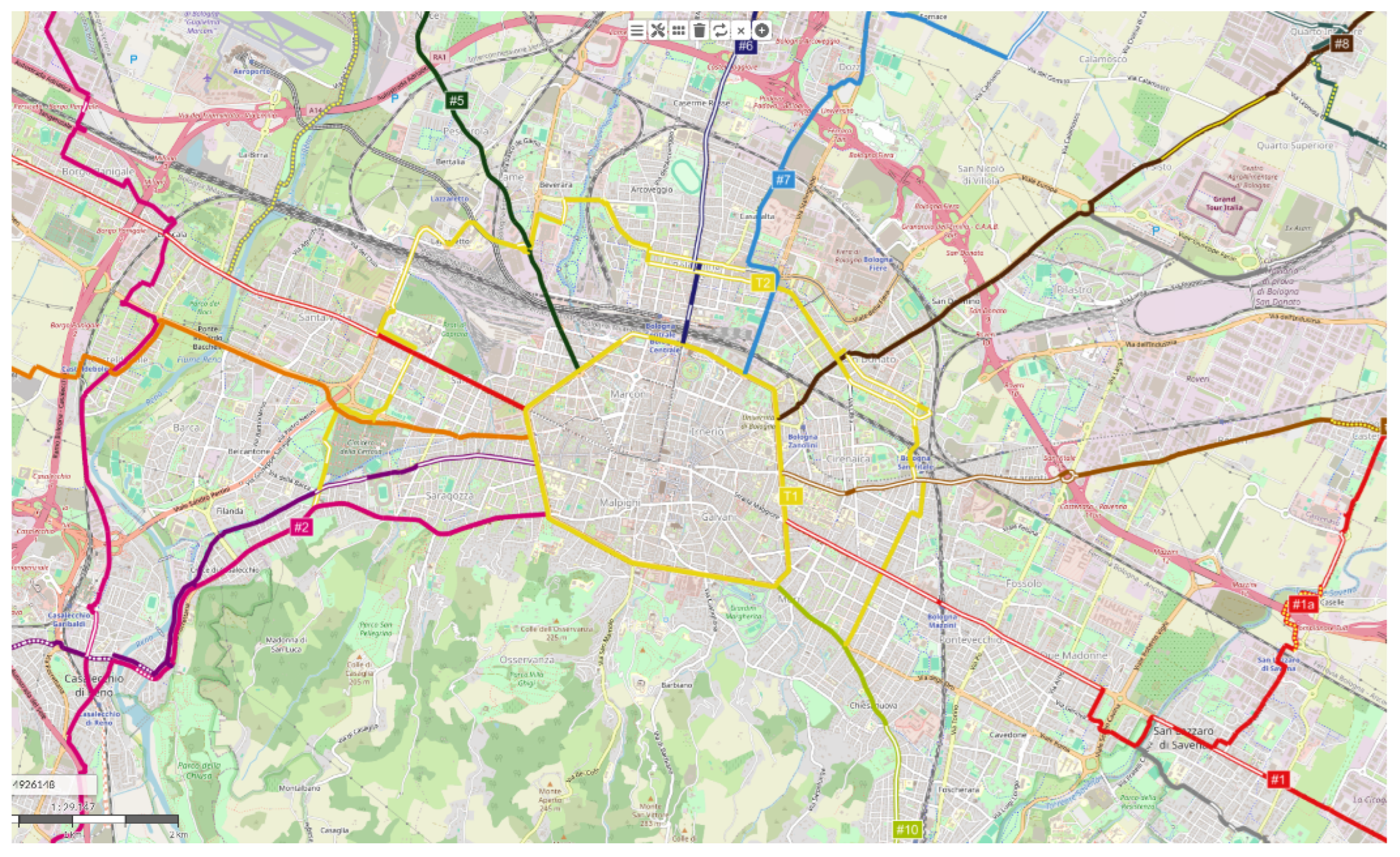

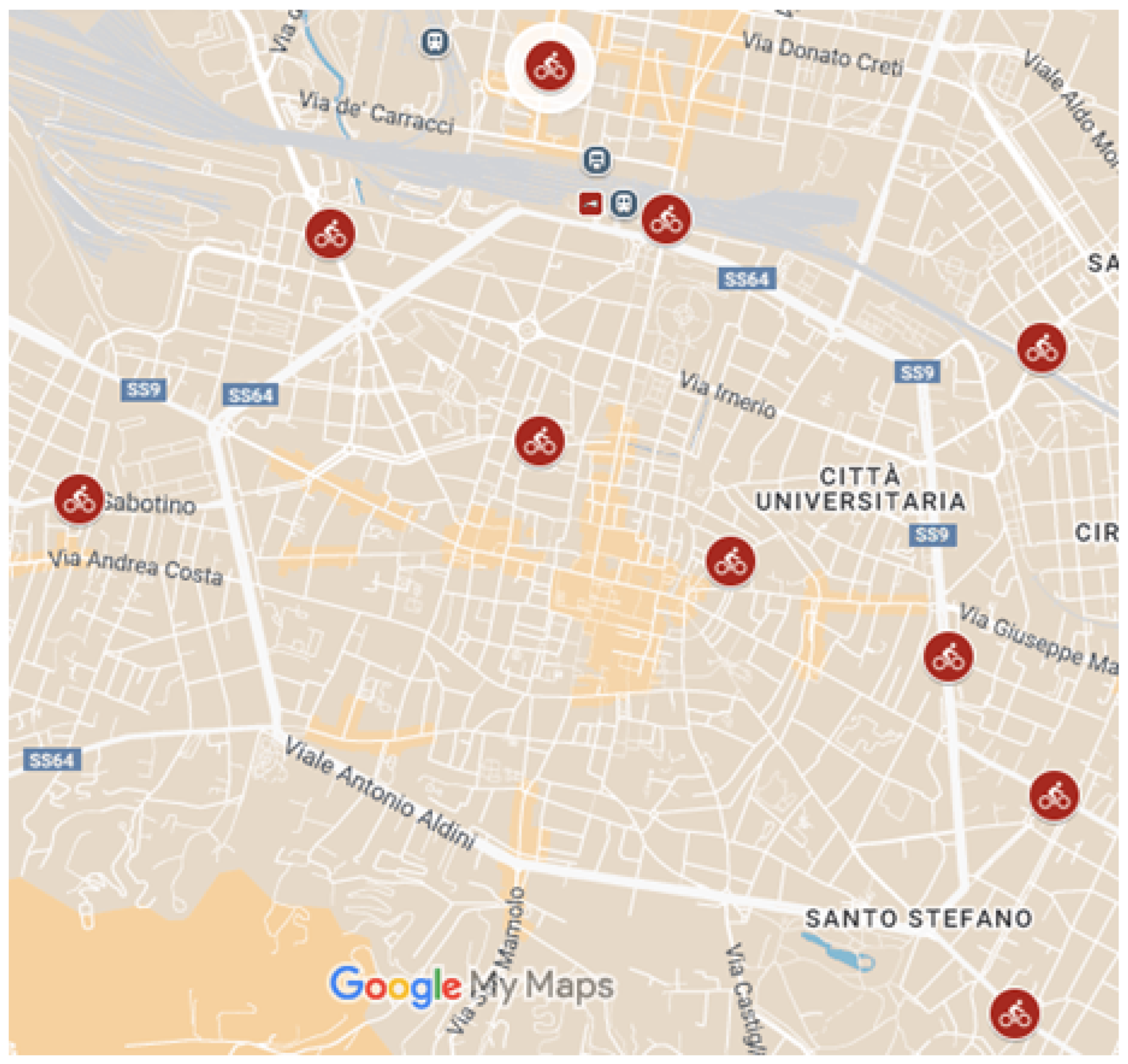

1.2. Bologna Case Study

2. Data and Methods

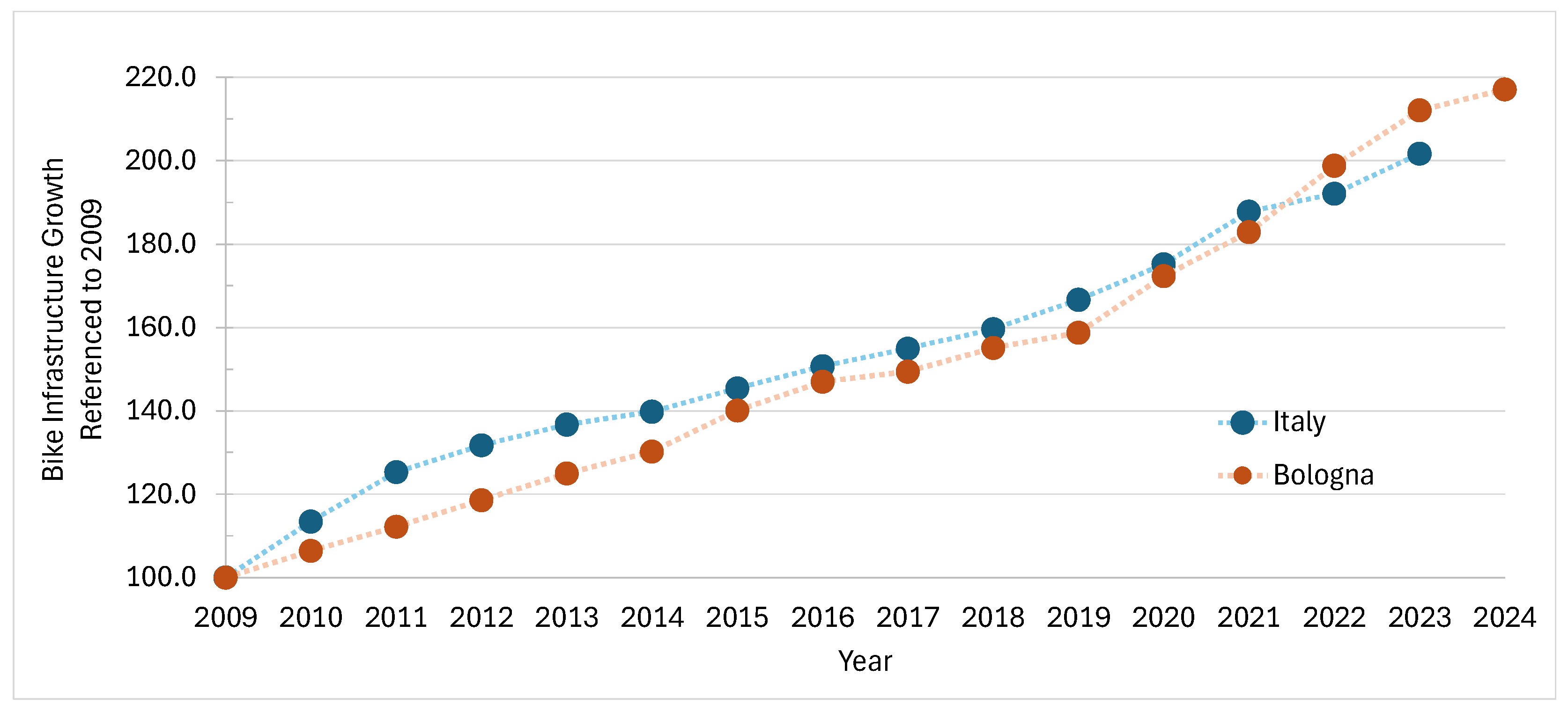

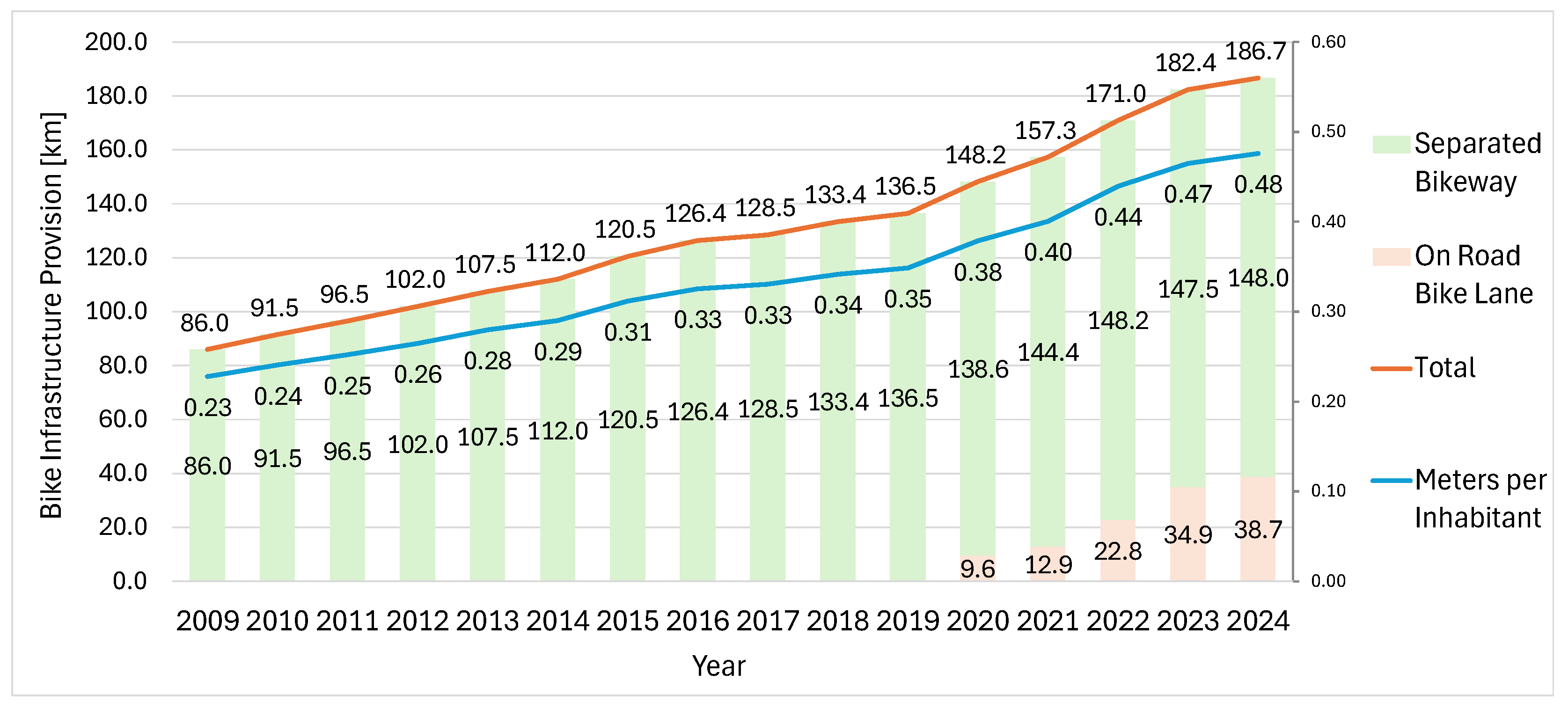

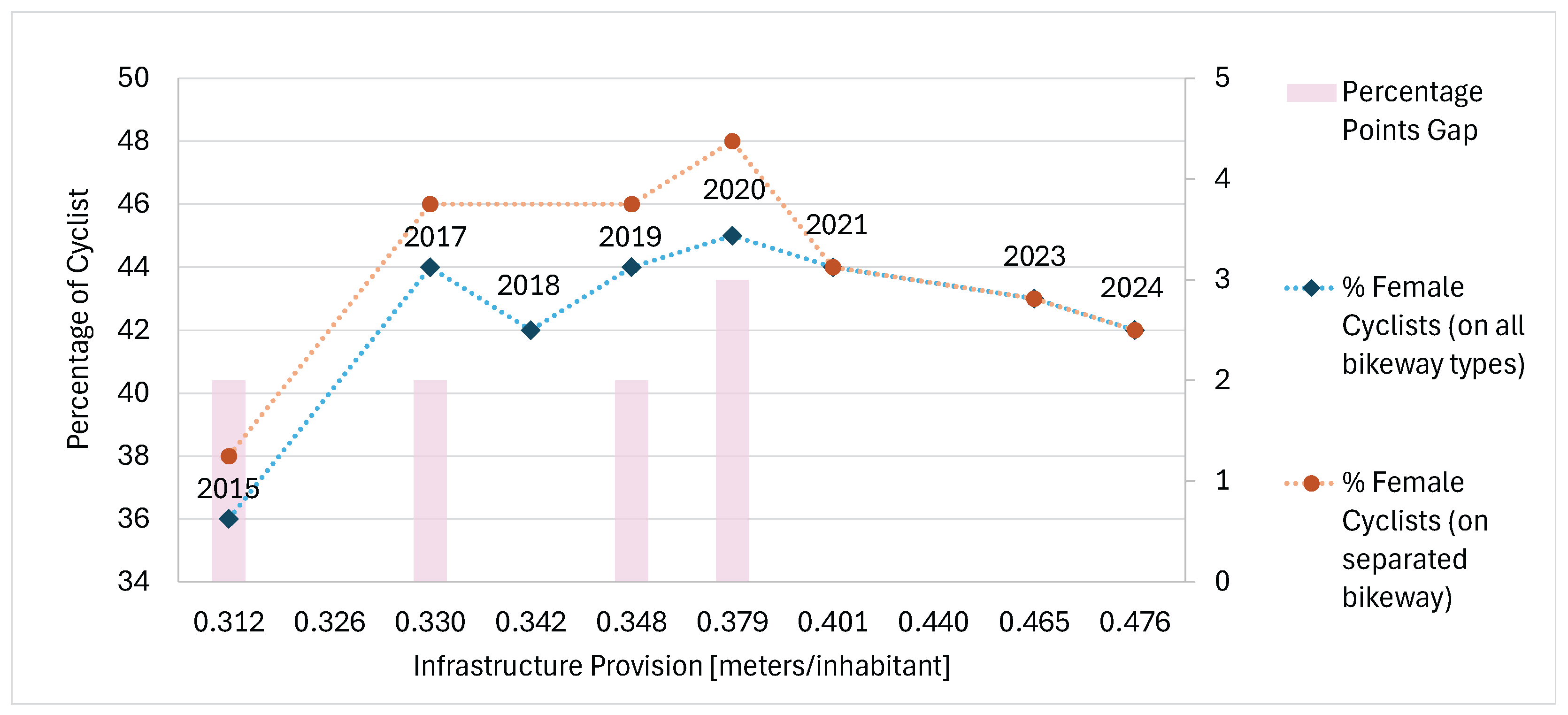

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Legambiente. Rapporto L’A Bi Ci, 2017.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Urban and transport planning pathways to carbon neutral, liveable and healthy cities; A review of the current evidence. Environment international 2020, 140, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, J.; Carr, T. Bicycle commuting and facilities in major US cities: if you build them, commuters will use them. Transportation research record 2003, 1828, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.C.; Allen, D. If you build them, commuters will use them: association between bicycle facilities and bicycle commuting. Transportation research record 1997, 1578, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.; Burns, E.K. Cycling to work in Phoenix: Route choice, travel behavior, and commuter characteristics. Transportation Research Record 2001, 1773, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, J.; Wardman, M.; Page, M. Estimation of the determinants of bicycle mode share for the journey to work using census data. Transportation 2008, 35, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Komanoff, C.; Schimek, P. Bicycling renaissance in North America?: Recent trends and alternative policies to promote bicycling. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 1999, 33, 625–654. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, B.W.; Vattikuti, V.R.; Brannick, M.T. Real-time human perceptions: Toward a bicycle level of service. Transportation Research Record 1997, 1578, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axhausen, K.W.; Smith Jr, R. Bicyclist link evaluation: a stated-preference approach Transportation Research Record 1986, 1085, 7–15.

- Hunt, J.D.; Abraham, J.E. Influences on bicycle use. Transportation 2007, 34, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, K.J. Two approaches to valuing some of bicycle facilities’ presumed benefits: Propose a session for the 2007 national planning conference in the city of brotherly love. Journal of the American Planning Association 2006, 72, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, M.A.; Bhat, C.R. Commuter bicyclist route choice: Analysis using a stated preference survey. Transportation research record 2003, 1828, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, N.Y.; Levinson, D.M.; Krizek, K.J. Trails, lanes, or traffic: Valuing bicycle facilities with an adaptive stated preference survey. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2007, 41, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.; Brauer, M.; Setton, E.M.; Teschke, K. Built environment influences on healthy transportation choices: bicycling versus driving. Journal of urban health 2010, 87, 969–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winters, M.; Davidson, G.; Kao, D.; Teschke, K. Motivators and deterrents of bicycling: comparing influences on decisions to ride. Transportation 2011, 38, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Krizek, K.J.; Agrawal, A.W.; Stonebraker, E. Reliability testing of the Pedestrian and Bicycling Survey (PABS) method. Journal of physical activity and health 2012, 9, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill, J. Bicycling for transportation and health: the role of infrastructure. Journal of public health policy 2009, 30, S95–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghini, G.; Carrasco, N.; Schüssler, N.; Axhausen, K.W. Route choice of cyclists in Zurich. Transportation research part A: policy and practice 2010, 44, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.; Sall, E.; Charlton, B. A GPS-based bicycle route choice model for San Francisco, California. Transportation letters 2011, 3, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broach, J.; Dill, J.; Gliebe, J. Where do cyclists ride? A route choice model developed with revealed preference GPS data. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2012, 46, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, S.; Krizek, K.J.; Rupi, F. Quantifying the role of disturbances and speeds on separated bicycle facilities. Journal of Transport and Land Use 2016, 9, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupi, F.; Poliziani, C.; Schweizer, J. Data-driven bicycle network analysis based on traditional counting methods and GPS traces from smartphone. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2019, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupi, F.; Schweizer, J. Evaluating cyclist patterns using GPS data from smartphones. IET Intelligent Transport Systems 2018, 12, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupi, F.; Poliziani, C.; Schweizer, J. Analysing the dynamic performances of a bicycle network with a temporal analysis of GPS traces. Case studies on transport policy 2020, 8, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.; Reeder, S.; Gabbe, B.; Beck, B. What a girl wants: a mixed-methods study of gender differences in the barriers to and enablers of riding a bike in Australia. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour 2023, 94, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, R.; Elliott, B.; Woodcock, J.; Goodman, A. Cycling provision separated from motor traffic: a systematic review exploring whether stated preferences vary by gender and age. Transport reviews 2017, 37, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, Z.; Ewing, G.; Haider, M. Gender-based analysis of work trip mode choice of commuters in suburban Montreal, Canada, with stated preference data. Transportation Research Record 2005, 1924, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingil, A.E.; Rupi, F.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. An integrative review of socio-technical factors influencing travel decision-making and urban transport performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H. Causal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on daily ridership of public bicycle sharing in Seoul. Sustainable cities and society 2023, 89, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafri, N.M.; Khan, A.; Jamal, S.; Alam, B.M. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 transmission in different travel modes. Transportation research interdisciplinary perspectives 2022, 13, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anke, J.; Francke, A.; Schaefer, L.M.; Petzoldt, T. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mobility behaviour in Germany. European Transport Research Review 2021, 13, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, J.P.; Michael, J.P.; Duren, M.L.; Mui, Y.; Porter, K.M.P. Mobility patterns before, during, and anticipated after the COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity to nurture bicycling. American journal of preventive medicine 2021, 60, e277–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D.M.; Hadjiconstantinou, M. Changes in commuting behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Journal of transport & health 2022, 24, 101313. [Google Scholar]

- Monterde-i Bort, H.; Sucha, M.; Risser, R.; Kochetova, T. Mobility patterns and mode choice preferences during the COVID-19 situation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitas, A.; Tsigdinos, S.; Karolemeas, C.; Kourmpa, E.; Bakogiannis, E. Cycling in the era of COVID-19: Lessons learnt and best practice policy recommendations for a more bike-centric future. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecouteux, G.; Moulin, L. Cycling in the aftermath of COVID-19: An empirical estimation of the social dynamics of bicycle adoption in Paris. Transportation research interdisciplinary perspectives 2024, 25, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Koch, N. Provisional COVID-19 infrastructure induces large, rapid increases in cycling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2024399118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irawan, M.Z.; Andani, I.G.A.; Hasanah, A.; Bastarianto, F.F. Do cycling facilities matter during the COVID-19 outbreak? A stated preference survey of willingness to adopt bicycles in an Indonesian context. Asian Transport Studies 2023, 9, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Bologna I numeri di Bologna Metropolitana: demografia, 2024.

- Comune di Bologna I numeri di Bologna Metropolitana: indagine casa lavoro nel comune di bologna, 2023.

- ISTAT - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Aspetti della vita quotidiana.

- Directorate-General for Communication Special Eurobarometer 495: Mobility and transport, 2019.

- Comune di Bologna I numeri di Bologna Metropolitana: piste ciclabili, 2024.

- Comune di Bologna Sustaineble Urban Mobility Plan of Metropolitan Bologna.

- ISTAT - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Mobilità Urbana.

- Ancma-Legambiente. Infrastrutture e politiche di incentivazione per moto e biciclette nei comuni capoluogo italiani, 2024.

- Rupi, F.; Freo, M.; Poliziani, C.; Postorino, M.N.; Schweizer, J. Analysis of gender-specific bicycle route choices using revealed preference surveys based on GPS traces. Transport policy 2023, 133, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

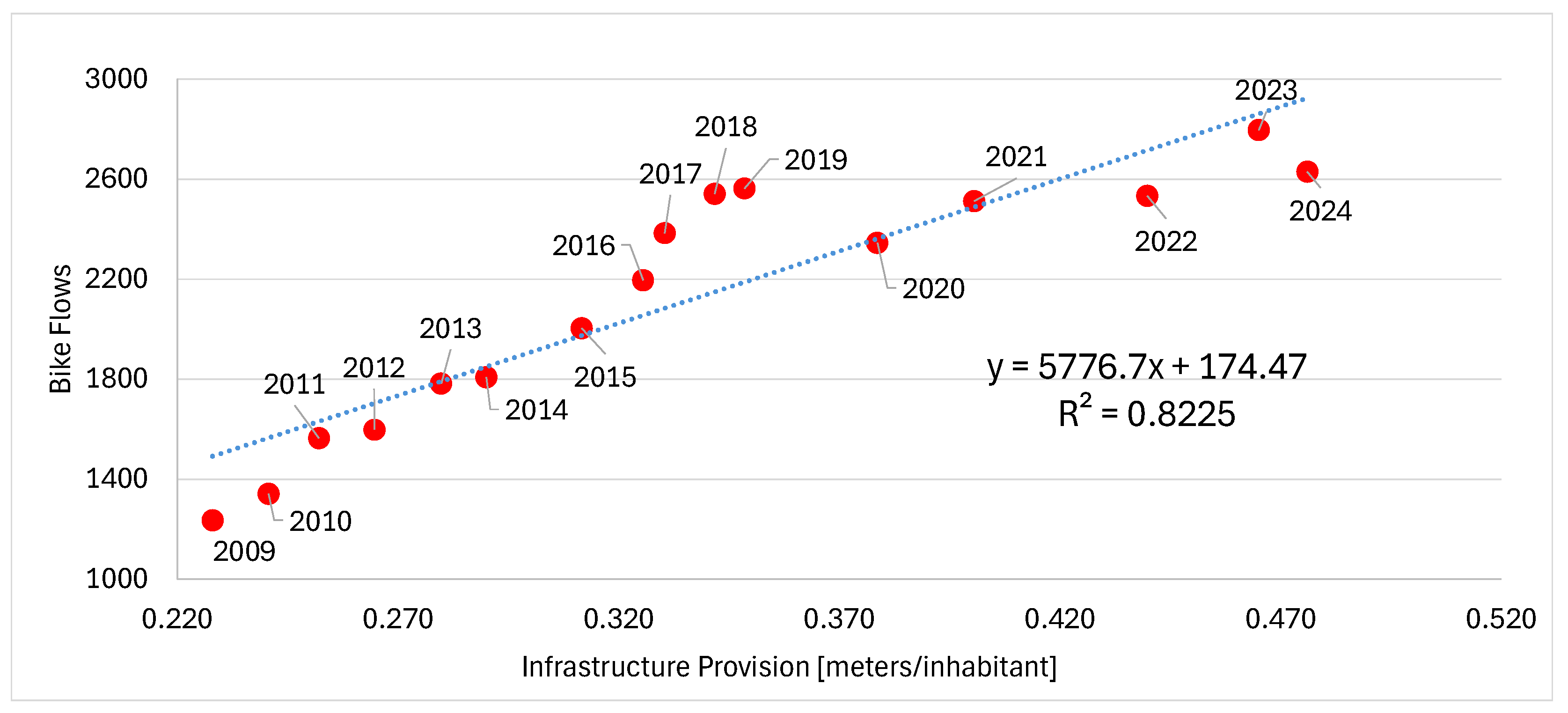

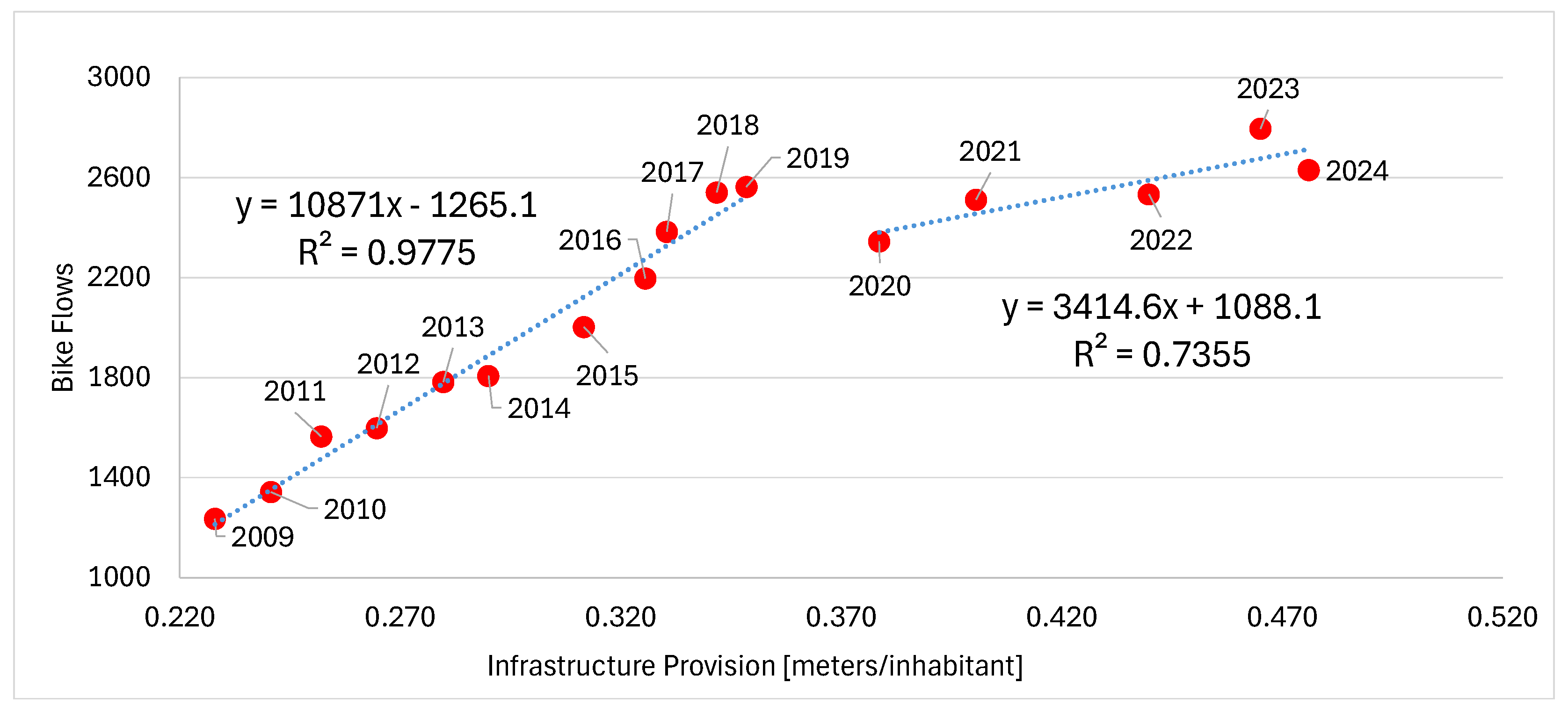

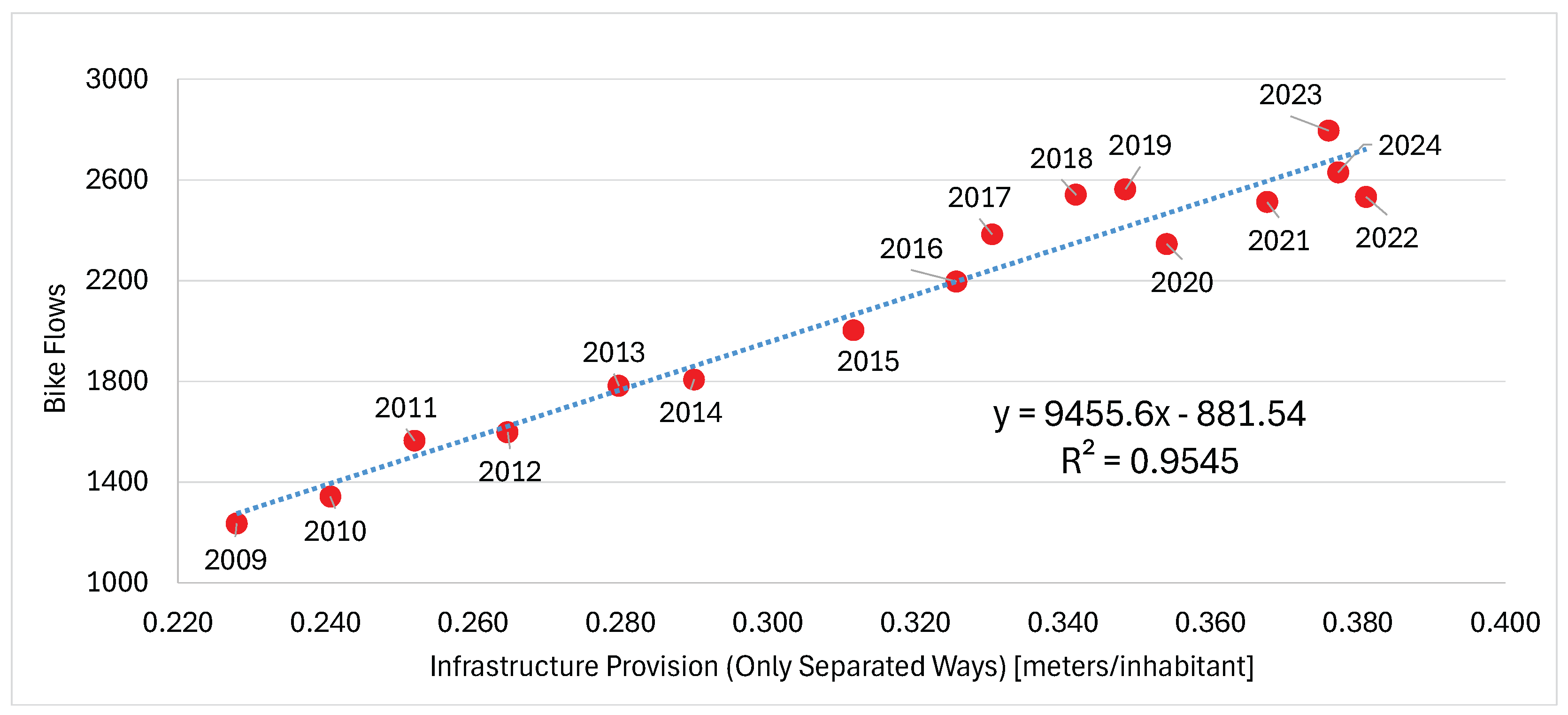

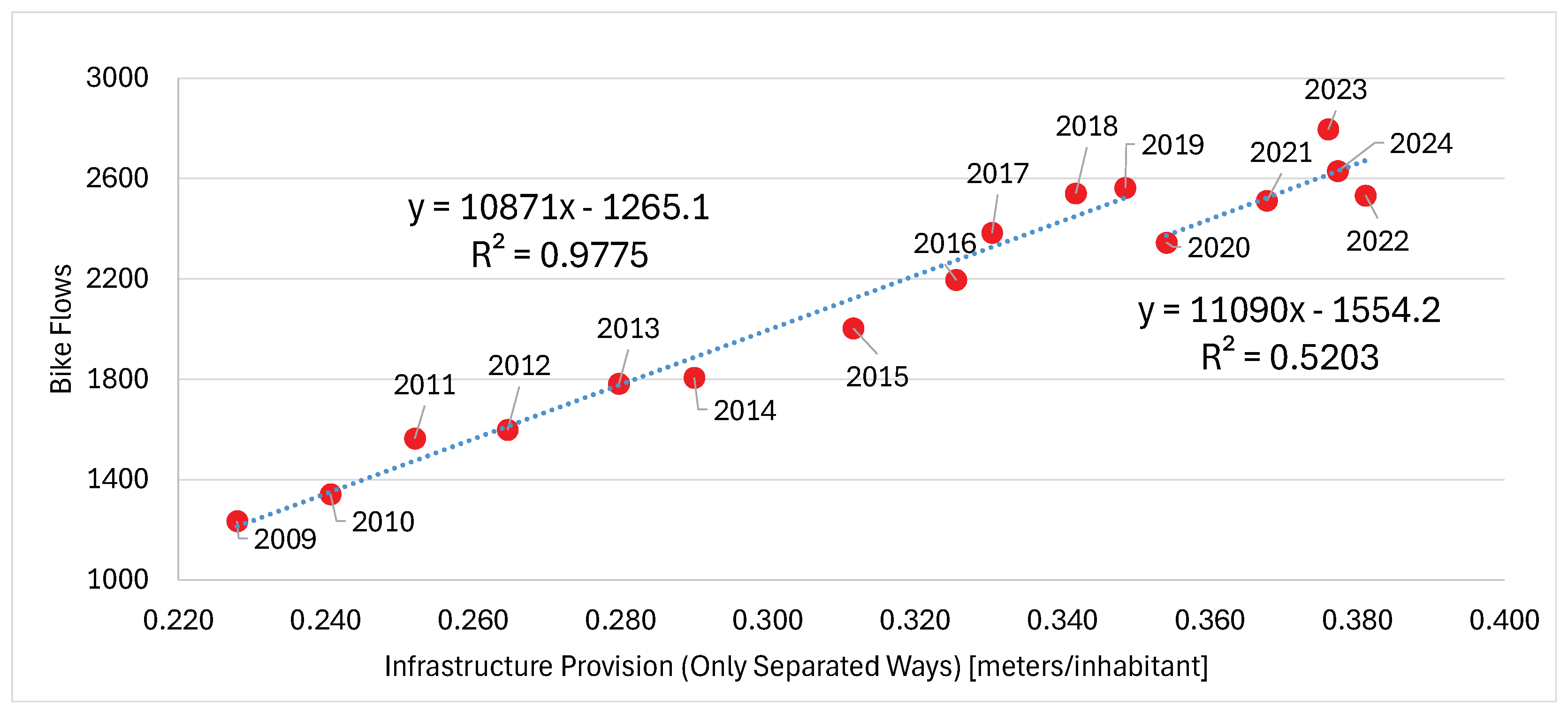

| Linear Regression Model | Model parameter | Parameter value | t stat | p | Model’s SE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. All Inf. 2009-2024 i | 174.47 | 0.7064 | 0.4915 | 217.7 | 0.8224 | |

| 5776.7 | 8.0532 | <0.0001** | ||||

| 2. All Inf. 2009-2019 i | -1265.1 | -7.8097 | <0.0001** | 73.5 | 0.9775 | |

| 10871 | 19.7895 | <0.0001** | ||||

| 3. All Inf. 2020-2024 i | 1088.1 | 2.1228 | 0.1239 | 98.4 | 0.7355 | |

| 3414.6 | 2.8886 | 0.0631* | ||||

| 4. Sep. Inf. 2009-2024ii | -881.54 | -4.9833 | 0.0002** | 110.1 | 0.9545 | |

| 9455.6 | 17.1451 | <0.0001** | ||||

| 5. Sep. Inf. 2009-2019ii | -1265.1 | -7.8097 | <0.0001** | 73.5 | 0.9775 | |

| 10871 | 19.7895 | <0.0001** | ||||

| 6. Sep. Inf. 2020-2024ii | -1554.2 | -0.6807 | 0.5449 | 132.5 | 0.5203 | |

| 11090 | 1.8038 | 0.1690 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).