Submitted:

10 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

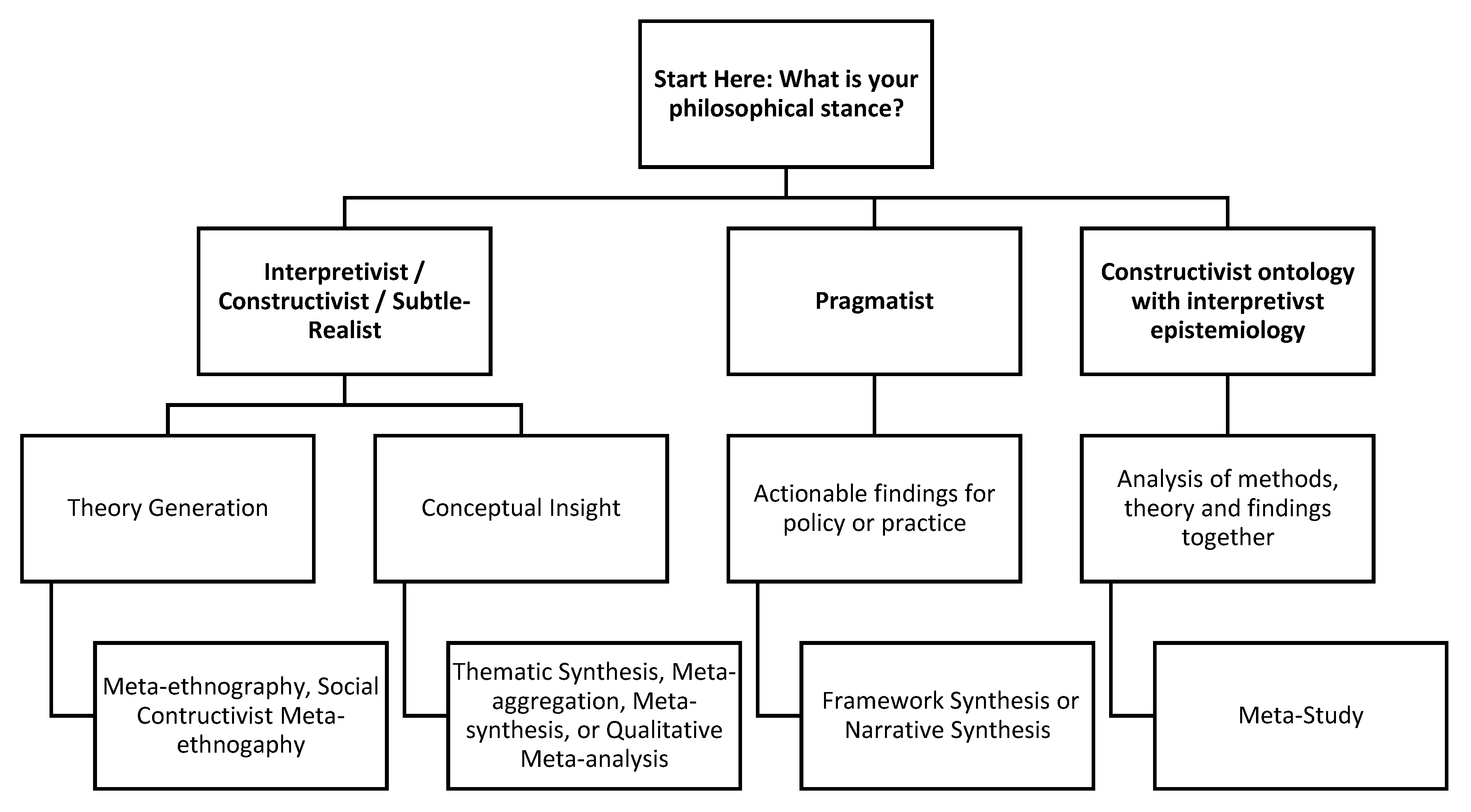

Background: There is a proliferation of terms that are used to define and describe qualitative methods of review synthesis. These terms can make understanding which approach to use difficult and the ability to generate operational clarity challenging. This is particularly important for life-span mental health research and further research is required that exams and maps the terms and approaches to synthesis. Objective: This scoping review aims to map the landscape of qualitative synthesis methods, evaluate the ability to operationalise named methods, explore their philosophical foundations and methodological associations and consider the application within a specifically identified area of life-span mental health research. Methods: Following PRISMA-ScR guidelines a scoping review was undertaken. A comprehensive search was conducted across multiple databases and grey literature sources. Articles were included that examined a methodological approach to qualitative synthesis. Data extraction and charting focused on synthesis type, frameworks, philosophical alignment, and operational guidance. Results: Fifty-four articles were identified and within these 14 qualitative methodologies were identified and 5 types of aggregative methods and 10 types of interpretive methods of synthesis. Meta-ethnography, meta-synthesis, framework synthesis were the most frequently cited methodologies. A subset of these methodologies and methods were found to be the more operationalizable and these are discussed. Conclusion: The review highlights significant terminological and methodological fragmentation in qualitative synthesis. It underscores the need for clearer guidance, standardised terminology, and stronger links between synthesis methodologies, methods and philosophical traditions. A decision tree is proposed to support researchers in selecting appropriate synthesis methodologies.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Design

Eligibility Criteria

Population

Concept

Context

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Selection process for sources of evidence

Data Extraction

Analysis

Results

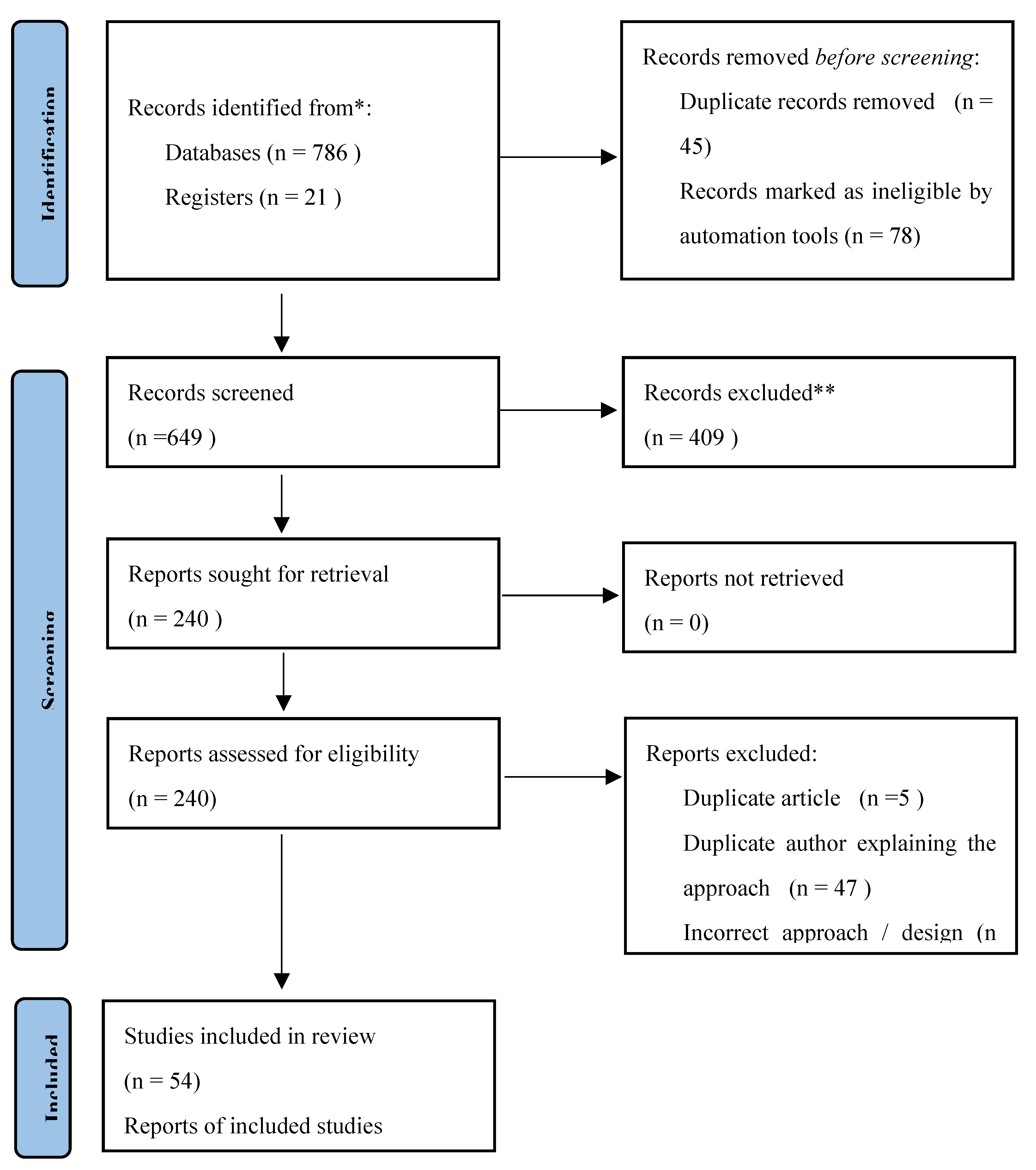

Search output

Charting the Data and Synthesis

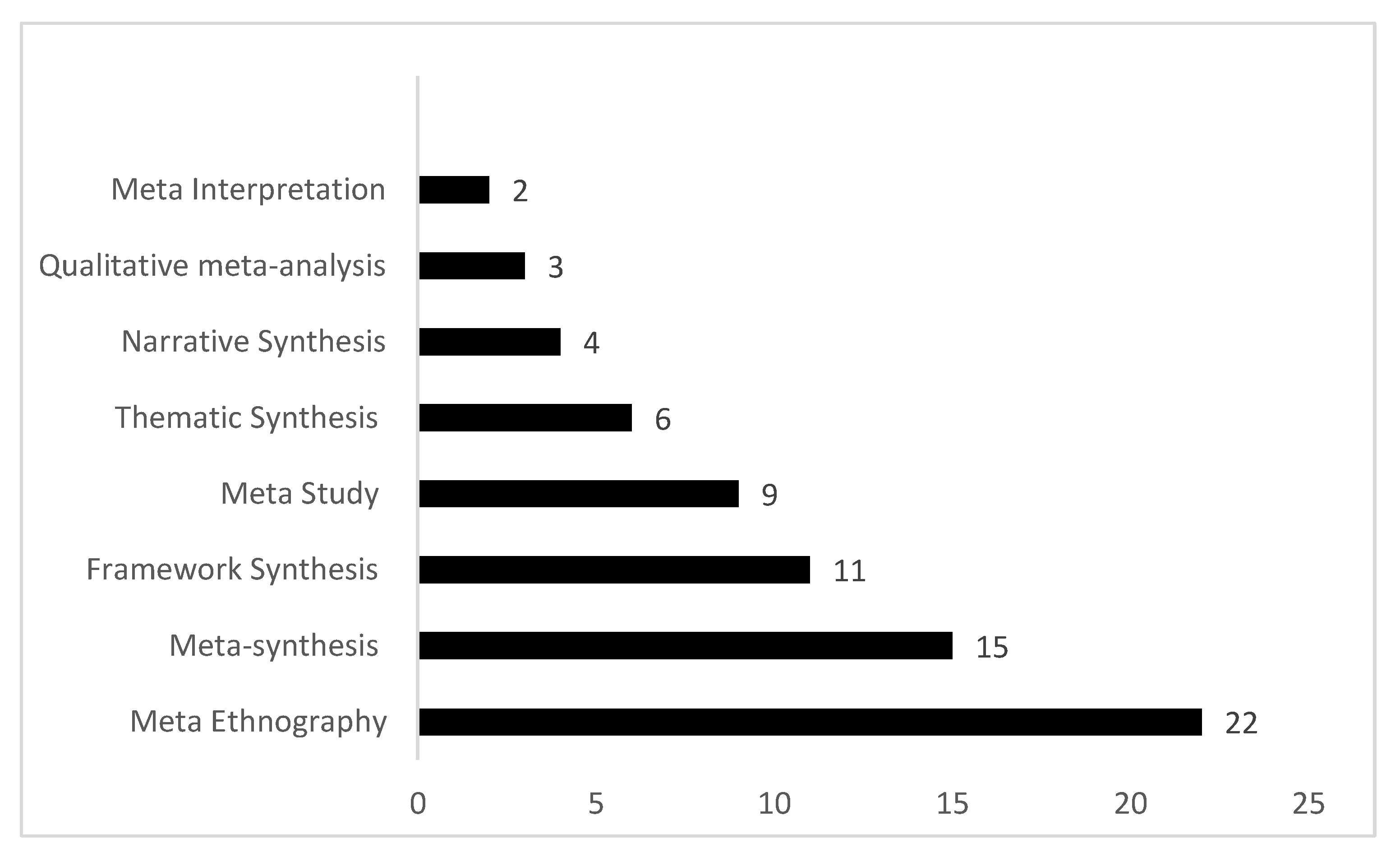

Methodologies identified

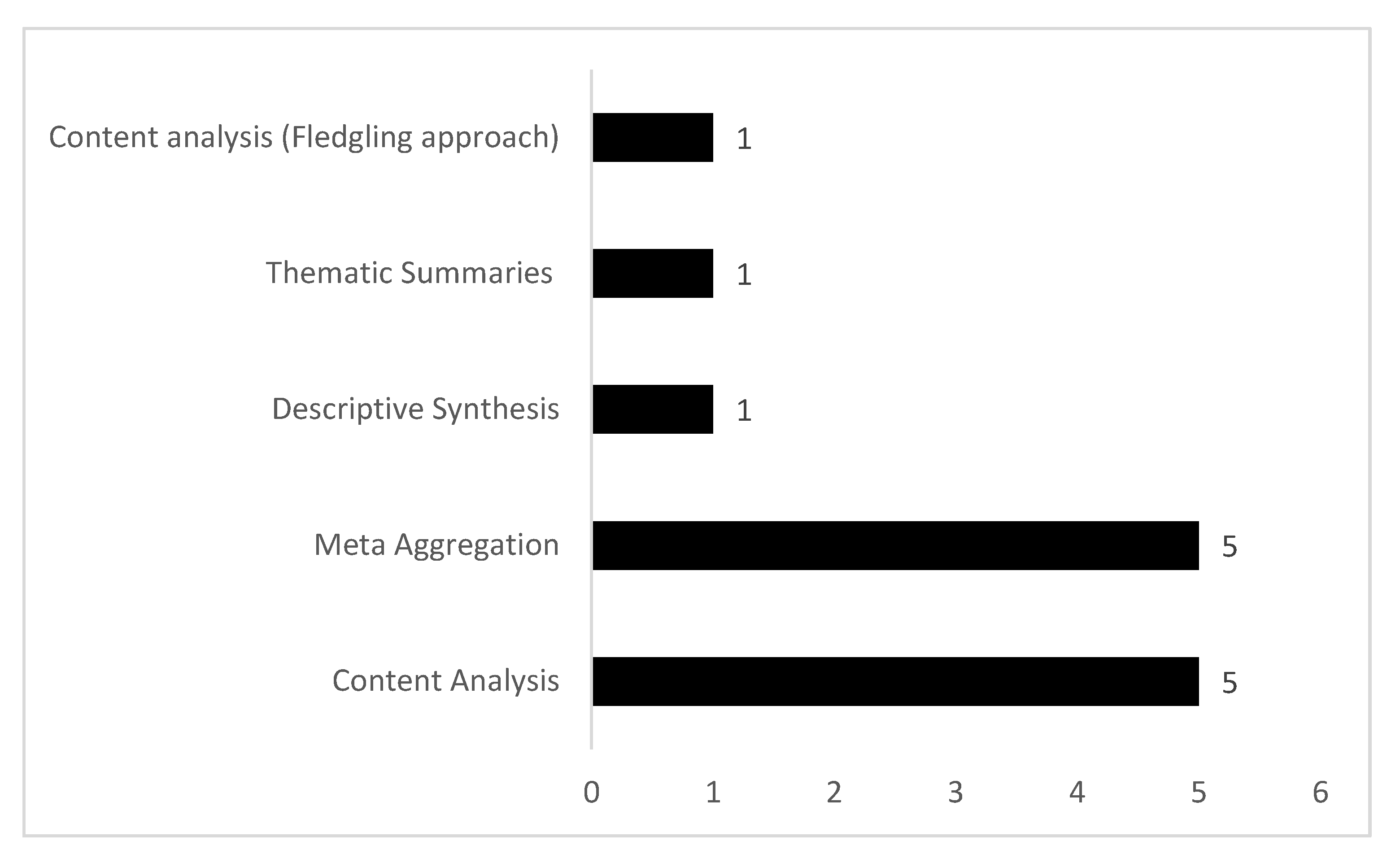

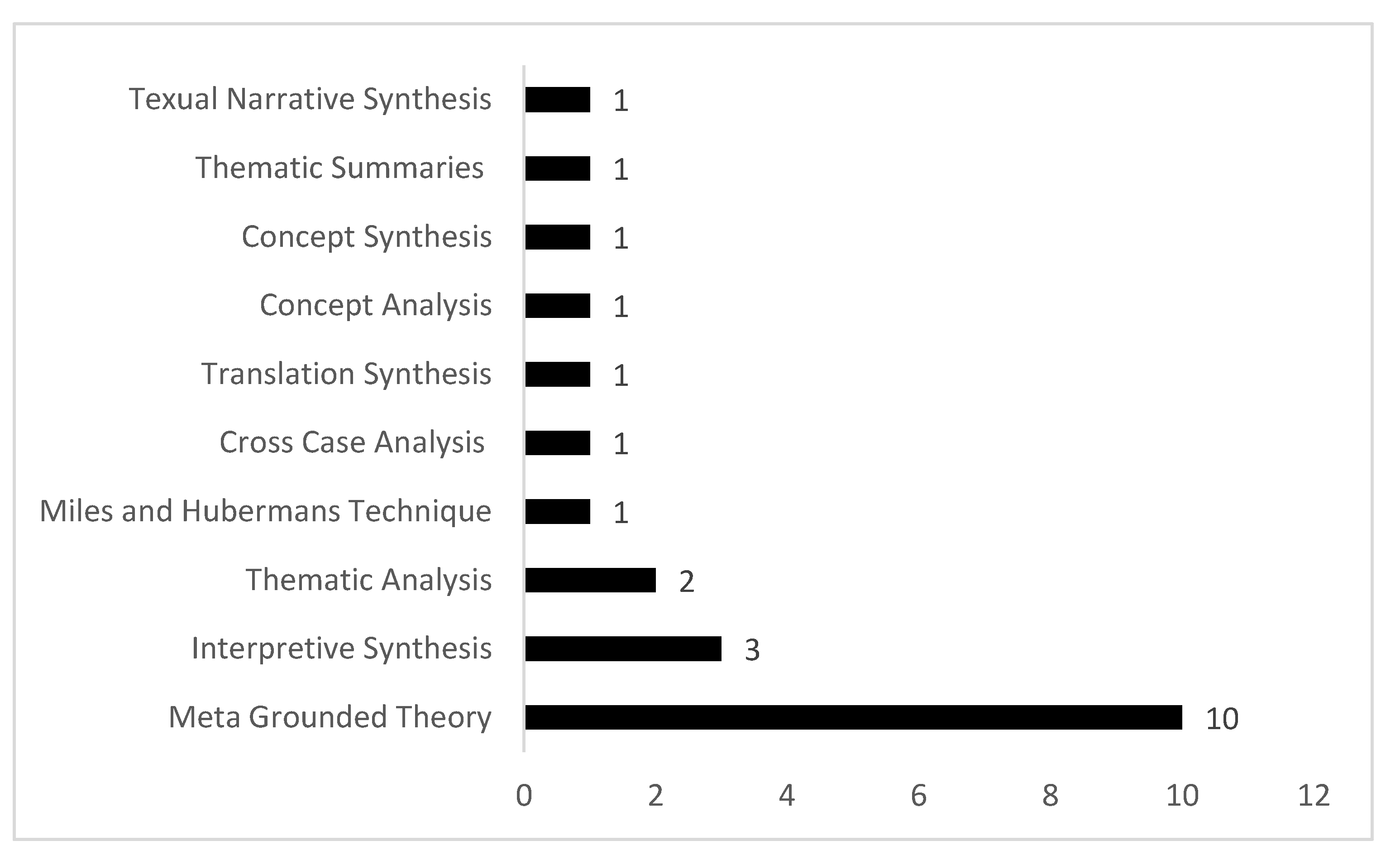

Methods identified

Discussion

Proliferation and Confusion of Terminology

Operationalisation: A Key Focus

Philosophical Foundations: Interpretive versus Aggregative Approaches

Implications for Reviewers and Methodologists

- Four methodologies have the most guidance including meta-ethnography, meta-synthesis, framework synthesis and meta-study. Each of these methodologies will provide a different output and warrant consideration.

- Clearer guidance is needed for reviewers to select and apply synthesis methods appropriately. Meta-aggregation is arguably the easiest method to apply due to the guidance being associated with the Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Methodologies can be selected using a decision tree. See Figure 5.

- Terminological standardisation could help reduce confusion and improve the comparability of synthesis approaches.

- Training and education in qualitative synthesis should emphasise the link between philosophical foundations and methodological choices, helping researchers navigate the interpretive-aggregative spectrum more effectively.

Illustrative Application: Synthesising Qualitative Research on Adolescent Depression

Examples of reviews providing conceptual insight (thematic synthesis, meta aggregation and meta-synthesis)

An example of analyzing methods, theory and findings (Meta-study)

Example of providing actionable findings for theory and practice (framework synthesis and narrative synthesis)

Future Directions

- Develop consensus frameworks for under-defined synthesis approaches.

- Explore the epistemological implications of repeated interpretive syntheses on the same topic.

- Investigate how synthesis methods can be better linked to empirical methodologies, potentially enhancing coherence and applicability.

- Examine the impact of philosophical alignment on the quality and utility of synthesis findings, especially in applied fields like health policy and rehabilitation.

Limitations

References

- Achterbergh, L.; Pitman, A.; Birken, M.; et al. The experience of loneliness among young people with depression: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, R. T. P.; Bolton, K. W. Qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis in social work research: Uncharted territory. Journal of Social Work 2014, 14(3), 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, K. E.; Brundage, J. S.; Sweet, P.; Vandenberghe, F. Towards a critical realist epistemology? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Urpi, A.; Slade, M.; Manley, D.; Padro-Hernandez, H. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health among children and adolescents: a systematic review and narrative synthesis protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2009, 9(59). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearman, M.; Dawson, P. Qualitative synthesis and systematic review in health professions education. Medical Education 2013, 47, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, E. Is meta-synthesis turning rich descriptions into thin reductions? A criticism of meta-aggregation as a form of qualitative synthesis. Nursing Inquiry 2019, 26(1), e12273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Sommer, I.; Noyes, J.; Houghton, C.; Campbell, F. Rapid reviews methods series: Guidance on rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2024, 29(3), 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Carroll, C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis for studies of improvement in health care. British Medical Journal Quality and Safety 2015, 24, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, C. B.; Frederiksen, K. A comprehensive example of how to conduct a literature review following Glaser’s grounded theory methodological approach. International Journal of Health Sciences 2018, 6(1), 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, N.; Campbell, R.; Pope, C.; Donovan, J.; Morgan, M.; Pill, R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 2002, 7(4), 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, K.L.; Sandhu, V.K.; Sunderji, N.; et al. Youth experiences of transition from child mental health services to adult mental health services: a qualitative thematic synthesis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunton, G.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Research Synthesis Methods 2019, 11, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, M.; Robinson, K.; Pettigrew, J.; Galvin, R.; Stanley, M. Qualitative synthesis: A guide to conducting a meta-ethnography. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2018, 81(3), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Cooper, K. A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013a, 13(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Leaviss, J.; Rick, J. Best fit framework synthesis: Refining the method. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013b, 13(37). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis; Sage, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. The power of constructivist grounded theory for critical inquiry . Qualitative Inquiry 2017, 23(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Boore, J. R. P. Using a synthesised technique for grounded theory in nursing research. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2009, 18(16), 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrastina, J. (2020). Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies: Background, methodology and applications. Institute of Special Education Studies, Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc. Education Resources Information Centre. URL: ED603222.pdf.

- Collins, K. M., & Levitt, H. M. (2021). Qualitative meta-analysis: Issues to consider in design and review. In P. M. Camic (Ed.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (2nd ed., pp. 283–299). American Psychological Association. Camic, P. M. (Ed.). [CrossRef]

- de Vos, J.A.; LaMarre, A.; Radstaak, M.; et al. Identifying fundamental criteria for eating disorder recovery: a systematic review and qualitative meta-analysis. J Eat Disord 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Cavers, D.; Agarwal, S.; Annandale, E.; Arthur, A.; Harvey, J.; Sutton, A. J. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2006, 6(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Agarwal, S.; Jones, D.; Young, B.; Sutton, A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 2005, 10(1), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drisko, J. W. Qualitative research synthesis: An appreciative and critical introduction. Qualitative Social Work 2020, 19(4), 736–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.; Pearson, A. Systematic reviews of qualitative research. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 2001, 5(3), 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaves, Y. D. A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001, 35(5), 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estabrooks, CC; Field, PA; Morse, JM. Aggregating Qualitative Findings: An Approach to Theory Development. Qual Health Res 1994, 4(4), 503–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendt, J. Embracing emergence in qualitative meta-analysis: A guide to higher-order synthesis. Methodological Innovations 2025, 18(3), 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. Generalizability and transferability of meta-synthesis research findings. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2010, 66(2), 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qualitative Research 2013, 14(3), 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, K.; Dixon, A. Qualitative meta-synthesis: A guide for the novice. Nurse Researcher 2008, 15(2), 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, K.; Noyes, J. Qualitative evidence synthesis: Where are we at? International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, E. F.; Wells, M.; Lang, H.; Williams, B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5(1), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, E. F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E. A. S.; Jepson, R. G.; Noyes, J. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2019, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. Conceptualization and measurement of coping during adolescence: a review of the literature. J Nurs Scholarsh 2010, 42(2), 166–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewurtz, R.; Stergiou-Kita, M.; Shaw, L.; Kirsh, B.; Rappolt, S. Qualitative meta-synthesis: Reflections on the utility and challenges in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 2008, 75(5), 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B. G.; Strauss, A. L. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research; Aldine, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Grass, K. The three logics of qualitative research: Epistemology, ontology, and methodology in political science. American Journal of Qualitative Research 2024, 8(1), 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine 2005, 61(2), 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Gorczynski, P.; Soundy, A. A narrative synthesis investigating the use and value of social support to promote physical activity among individuals with schizophrenia. In Disability and Rehabilitation; 2015; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannes, K.; Lockwood, C. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta-aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis . Journal of Advanced Nursing 2011, 67(7), 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoon, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Case Studies: An Approach to Theory Building; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hannes; Macaitis. A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Habersang; Reihlen. Advancing Qualitative Meta-Studies (QMS): Current Practices and Reflective Guidelines for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossler, D.; Scalese-Love, P. Grounded meta-analysis: A guide for research syntheses. The Review of Higher Education 1989, 13(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, J., Campbell, F., Harden, A., & Thomas, J. (2011). Mixed methods synthesis: A worked example. In Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Jensen, L. A.; Allen, M. N. Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qualitative Health Research 1996, 6(4), 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, MH. Enduring love: a grounded formal theory of women's experience of domestic violence. Res Nurs Health 2001, 24(4), 270–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachal, J.; Revah-Levy, A.; Orri, M.; Moro, M. R. Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2017, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, H.; Walker, A. Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis methodologies: Rigorously piecing together research. TechTrends 2018, 62(6), 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H. M.; Pomerville, A.; Surace, F. I. A qualitative meta-analysis examining clients’ experiences of psychotherapy: A new agenda. Psychological Bulletin 2016, 142(8), 801–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H. M. How to conduct a qualitative meta-analysis: Tailoring methods to enhance methodological integrity. Psychotherapy Research 2018, 28(3), 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Boutillier, C.; Urch, C. Conceptual framework for living with and beyond cancer: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28(5), 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.; Olander, E.K.; Ayers, S.; et al. No straight lines – young women’s perceptions of their mental health and wellbeing during and after pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMC Women's Health 2019, 19, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A. A.; Moles, R. J.; Chen, T. F. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research: The challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2016, 38(3), 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 7: Qualitative evidence synthesis for emerging themes in primary care research: Scoping review, meta-ethnography and rapid realist review. European Journal of General Practice 2023, 29(1), 2274467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 2015, 13(3), 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, PJ; Baird, J; Arai, L; Law, C; Roberts, HM. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G., Olander, E. K., Ayers, S., Salmon, D. (2019). No straight lines – young women’s.

- perceptions of their mental health and wellbeing during and after pregnancy: a.

- systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMC Women’s Health 19, 152. [CrossRef]

- Meadus, R. J. Adolescents coping with mood disorder: a grounded theory study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2007, 14, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, D.; Mohajan, H. K. Constructivist grounded theory: A new research approach in social science. Research and Advances in Education 2022, 1(4), 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Sage.

- Noah, P. D. A systematic approach to the qualitative meta-synthesis. Issues in Information Systems 2017, 18(2), 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, E., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Bonell, C. (2016). Origins, methods, and advances in qualitative metasynthesis. Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford.

- Paterson, B. L.; Thorne, S. E.; Canam, C.; Jillings, C. Meta-study of qualitative health research: A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis; Sage, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R. Evidence-based policy: In search of a method. Evaluation 2002, 8(2), 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review–a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 2005, 10(1_suppl), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.; Jordan, Z.; Munn, Z. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta-aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2011, 67(7), 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, S.; Ben-Sheleg, E.; Ellen, M. E. Making sense of conducting a critical interpretive synthesis: A scoping review. Research Synthesis Methods 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Rehfuess, E.; Noyes, J.; Higgins, J. P. T.; Mayhew, A.; Pantoja, T.; Shemilt, I.; Sowden, A. Synthesizing evidence on complex interventions: How meta-analytical, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches can contribute. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2013, 66(11), 1230–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Porritt, K., Evans, C. Bennett, C. Loveday, H., Bjerrum, M. Salmond, S., Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Pang, D., Vineetha, K., Seah Betsy. Lockwood, C. Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence (2024). Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2024.Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-02.

- Rodriguez, J.; Radjack, R.; Moro, M.R.; et al. Migrant adolescents’ experience of depression as they, their parents, and their health-care professionals describe it: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024, 33, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronkainen, N.; Wilshire, G.; Willis, M. Meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2022, 15:1, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In Analyzing Qualitative Data; Bryman, A., Burgess, R. G., Eds.; Routledge, 1994; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rycroft-Malone, J.; McCormack, B.; Hutchinson, A. M.; DeCorby, K.; Bucknall, T. K.; Kent, B.; Schultz, A.; Snelgrove-Clarke, E.; Stetler, C. B.; Titler, M.; Wallin, L.; Wilson, V. Realist synthesis: Illustrating the method for implementation research. Implementation Science 2012, 7(33). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Í.; Kontio, H.; Pekkola, E. Findings from a Meta-Interpretation. In Mechanisms Affecting International Organisations’ Education Development Work; Brill, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, R.; Lawton, R.; Panagioti, M.; Johnson, J. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21(50), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schick-Makaroff, K.; MacDonald, M.; Plummer, M.; Burgess, J.; Neander, W. What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3(1), 172–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management; An International Journal: Supply Chain Management, 2012; Volume 17, 5, pp. 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Nunns, M.; Briscoe, S.; Anderson, R.; & Thompson Coon, J. A “Rapid Best-Fit” model for framework synthesis: Using research objectives to structure analysis within a rapid review of qualitative evidence. Journal of Research Synthesis Methods 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A. Social constructivist meta-ethnography – A framework construction. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2024, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A. Grounded theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Health Psychology: Contexts, Theory and Methods in Health Psychology, 2nd ed.; Brown, K., Cheng, C., Hagger, M., Hamilton, K., Sutton, S. R., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd, 2025; p. pp. [insert page numbers]. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-sage-handbook-of-health-psychology/book280824.

- Snilstveit, B.; Oliver, S.; Vojtkova, M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Journal of Development Effectiveness 2012, 4(3), 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2008, 8(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timulak, L. Meta-analysis of qualitative studies: A tool for reviewing qualitative research findings in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research 2009, 19(4–5), 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timulak, L.; McElvaney, R. Qualitative meta-analysis of insight events in psychotherapy. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 2013, 26(2), 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Barker, L. Living life precariously with rheumatoid arthritis – a mega-ethnography of nine qualitative evidence syntheses. BMC Rheumatology 2019, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twivy, E.; Kirkham, M.; Cooper, M. The lived experience of adolescent depression: A systematic review and meta-aggregation. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2023, 30(4), 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viduani, A.; Arenas, D. L.; Benetti, S.; Wahid, S. S.; Kohrt, B. A.; Kieling, C. 2024.

- Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis: How Is Depression Experienced by Adolescents? A Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 63, 970–990. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, D. C.; Walker, R. L.; Griffith, D. M. A meta-study of black male mental health and well-being. Journal of Black Psychology 2010, 36, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.; Downe, S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005, 50(2), 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. Meta interpretation: A method for the interpretive synthesis of qualitative research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2005, 6(1), Article 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. A potential method for the interpretive synthesis of qualitative research: Issues in the development of ‘meta-interpretation’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2008, 11(1), 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Chao, A.; Jang, M.; Minges, K. E.; Park, C. Methods for knowledge synthesis: An overview. Heart & Lung 2014, 43(5), 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Pawson, R. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: The RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses – Evolving Standards) project. Health Services and Delivery Research 2014, 2(30). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Buckingham, J.; Pawson, R. RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Medicine 2013, 11(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfswinkel, J. F.; Furtmueller, E.; Wilderom, C. P. M. Using grounded theory as a method for rigorously reviewing literature. European Journal of Information Systems 2013, 22(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. B.; Levitt, H. M. A qualitative meta-analytic review of the therapist responsiveness literature: Guidelines for practice and training. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 2020, 50(3), 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Methodological issues and challenges in data collection and analysis of qualitative meta-synthesis. Asian Nursing Research 2008, 2(3), 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S. Metamethod, Meta-data-analysis: What, Why, and How? Sociological perspective 1991, 34, 377–390. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1389517. [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, L. Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2006, 53(3), 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aim Category | Description | Example |

|

1. Methodological development / innovation (18 papers) |

These papers aimed to develop, refine, or introduce new synthesis methods or frameworks. They often proposed novel techniques, adapted existing ones, or created hybrid approaches to improve the rigour, flexibility, or applicability of synthesis. | “To introduce a synthesised technique for using grounded theory in nursing research” |

| 2. Overview or review of existing methods (15 papers) | These papers provided comprehensive overviews, comparisons, or critiques of existing synthesis methods. Their goal was to map the landscape of available approaches and help researchers understand the strengths, limitations, and contexts of use. | “To bring together and review the full range of methods of synthesis that are available” |

| 3. Guidance or instruction for applying methods (10 papers) | These papers offered practical guidance, frameworks, or step-by-step instructions for conducting synthesis. They were often aimed at helping researchers apply methods correctly and consistently. | “To provide clear methodological instructions to assist others in applying these synthesis methods” |

| 4. Exploration of specific synthesis techniques (8 papers) | These focused on particular synthesis types (e.g., meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis, narrative synthesis), often elaborating on their processes, benefits, and challenges. | “To demonstrate the benefits of applying meta ethnography to the synthesis of qualitative research” |

| 5. Conceptual or epistemological discussion (6 papers) | These papers explored the theoretical foundations, philosophical assumptions, or epistemological implications of synthesis. They often questioned the validity or coherence of combining certain methods or paradigms. | “To discuss whether this meta-aggregation form of research has a sound epistemological foundation and should be considered a viable form of meta-synthesis” |

| 6. Application to case studies or specific fields (5 papers) | These papers applied synthesis methods to specific domains (e.g., occupational therapy, psychiatry, supply chain management) or types of data (e.g., case studies), often to demonstrate feasibility or generate domain-specific insights. | “Provide the research design of a meta-synthesis of qualitative case studies” |

| Approach | What is an aggregated definition across studies of the approach | Identified sub-types of the approach and key differences? | Are there agreed stages and what are the processes | Originator or earliest reference identified | Framework that accompanies the approach & articles with detailed description |

| Meta-ethnography | Meta-ethnography is an interpretive method for synthesizing qualitative studies. It involves the translation of concepts and metaphors across studies to build explanatory theory, new conceptual understandings, and higher-order interpretations. The method goes beyond summarizing findings by merging and combining insights to form a line-of-argument synthesis. |

Social constructivist meta-ethnography (Soundy, 2024) which assumes a social constructivist philosophical position and brings grounded literature theory from the work of Charmaz. This approach emphasizes interpretation and conceptual translation, aiming to construct new theoretical understandings |

Agreed stages Yes Key stages Reciprocal Translational Analysis (RTA): Aligns concepts across studies. Refutational Synthesis: Explores contradictions. Lines-of-Argument (LOA): Builds a coherent whole from parts. |

Noblit and Hare (1988) | Frameworks: EMERGE (France et al., 2019). Social Constructivist Framework (Soundy, 2024) Articles Britten et al (2002), Cahill et al (2018), France et al (2016;2019), Mohammad et al (2016), Moser and Korstjensc (2023), Soundy (2024), Whittmore et al (2014) |

| Thematic synthesis | Thematic synthesis is a flexible and interpretative method that involves identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes across qualitative studies. It includes line-by-line coding, the development of descriptive and analytical themes, and aims to generate new insights, hypotheses, and conceptual frameworks. | No. This approach balances data-driven and theory-driven synthesis, moving from descriptive to interpretive insights. |

Agreed stages Most studies identify Thomas and Hardin (2008) and there three step approach. Step one coding text using line-by-line coding. Key stages Line-by-line coding Descriptive theme development Analytical theme generation Pattern identification, categorization, and hypothesis development |

Dixon-Woods et al (2005) | Framework No framework. Articles Flemming and Noyes (2021), Thomas and Hardin (2008) |

| Meta-synthesis | Meta-synthesis is an interpretive and systematic approach to integrating findings from multiple qualitative studies. It aims to generate new theoretical insights, holistic understanding, and conceptual interpretations of a phenomenon. Unlike meta-analysis, it focuses on synthesizing textual data and translating qualitative accounts to produce higher-level explanations and generalizations. | No. But many identify specific steps. This approach emphasizes holistic integration and theoretical insight, respecting dissonance and preserving original voices. |

Agreed stages No but many detailed approaches are available. Key stages Primary analysis and within-case coding Cross-case synthesis and translation Theory development and meta-theory Narrative presentation |

Jensen and Allen (1996) identified a 6 stage process | Framework No framework Articles: Gewurtz et al (2008) identify a 5 stage process Hoon (2013) identify an 8 stage process Jensen and Allen (1996) identify a 6 stage process Leary and Walker (2018) identify an 11 stage process Lachal et al (2017) identify a 6 stage process Walsh and Downe (2005) identify a 7 stage process Zimmer (2006) identifies a 6 stage process Xu (2008) identifies a 7 stage process Noah (2017) identify a 7 stage process |

| Meta-Study | Meta-study is a multifaceted and highly systematic research approach designed to analyse and synthesize qualitative research. It involves three core components: Meta-data analysis: Examining the findings across studies to identify patterns, themes, and insights. Meta-method: Analysing the methodologies used in the original studies to understand their influence on outcomes. Meta-theory: Investigating the theoretical frameworks that underpin the research to explore how they shape interpretation. | No. All references linked back to a book by Paterson et al (2001) This is a multi-layered synthesis, combining empirical, methodological, and theoretical insights. |

Agreed stages Yes. The agreed stages are based on work by Paterson et al (2001) Key stages Meta-data, meta-method, and meta-theory analysis Integration into mid-range theory |

Paterson et al (2001) | Framework: Ronkainen et al (2022) provides steps and best practice guidelines Articles Paterson et al (2001) Ronkainen et al (2022) |

| Framework synthesis | Framework synthesis is a qualitative evidence synthesis approach that adapts the logic and tools of Framework Analysis to reviews: it begins with an a priori conceptual framework (from existing theory, models, or review objectives), codes study findings against that framework, and then extends or revises it inductively to generate an explanatory model fit for decision-making and policy. | Yes. Best-Fit Framework Synthesis (BFFS; Carroll and Booth, 2015) starts from a pre-existing model that is the “best fit” for the review question, uses deductive coding to accommodate much of the data, and then applies an inductive phase to incorporate data not covered by the initial framework, producing a refined, context-specific model. | Agreed stages. Yes. Brunton et al (2020). Familiarization, framework selection, indexing, charting, mapping and interpretation. Alternative steps for BFFS see Booth and Carroll (2015) |

Ritchie & Spencer (1994) | Framework Brunton et al (2020). Booth and Carroll (2015) Articles Barnett-Page and Thomas (2009) Flemmings and Noyes (2021) Caroll (2013) |

| Narrative Synthesis | Narrative synthesis is “an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings. While it can manipulate statistical data, its defining characteristic is a textual approach that tells the story of the evidence across studies. It aims to bridge research, policy, and practice by bringing evidence together in a convincing narrative. The attached materials also characterise narrative synthesis as a systematic and transparent analytical process that integrates findings using conceptual mapping and reflection. | Yes. The output can vary. Excluding mixed methods application, a descriptive or thematic narrative synthesis is possible by summarising findings per study looking at common themes/patterns. Alternatively a structure synthesis with conceptual mapping. Key approaches can include juxtaposing findings, integrating and interpreting them and conceptual mapping to build a conceptual map. | Agreed stages: Yes. Based on Popay et al (2006). Key stages: 1.Developing a theory of how the intervention works, why and for whom. 2. Developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies. 3. Exploring relationships of the data. 4. Assessing the robustness of the synthesis. |

Popay et al (2006) | Framework Popay et al (2006) Articles: None that provide detail beyond framework. |

| Qualitative meta-analysis | A systematic, interpretive approach for synthesizing findings from multiple qualitative studies to generate higher-order insights and theoretical contributions that go beyond individual contexts. It emphasizes emergence, meaning new properties or insights arise from the interaction of multiple studies, not visible in any single study alone. Core characteristics: Interpretive rather than aggregative Preserves richness and complexity of qualitative data Focused on patterns, relationships, and conceptual advancements |

Yes. Emergent framework (Fendt, 2025) Grounded meta-analysis (mixed methods version not included here; (Hossler & Scalese-Love, 1989) Integrity-focused meta-analysis (Levitt et al., 2018). |

Yes. Emergent framework: Formulate research question with an emergent lens, select studies to enable emergent patterns, extract data to surface latent structures, synthesise to reveal higher order emergent insights, document emergent insights and analytical evolution, write up to communicate emergent contributions Integrity focused: identifying and describing primary studies, transforming primary findings into units of data, organising units into categories or themes, enhancing methodological integrity, |

Timulak (2009) | Framework Emergent framework (Fendt, 2025) Integrity-focused meta-analysis (Colins and Levitt 2021; Levitt et al., 2018). Articles Timulak (2009) |

| Meta-Interpretation | Interpretivist synthesis method that can maintain an interpretivist epistemology, using interpretation (not raw data) from published studies, focuses son meaning in context (valuing differences rather than reducing them to common denominators) produced. Emerging conceptual innovation and insights are valued as ouputs. | No. | Yes. Identify research area (consider theoretical sensitivity and maximum variation sampling), undertake initial analysis concurrent thematic and context analysis, iterative theoretical sampling and saturation, develop and refine exclusion criteria, maintain transparent audit trail, final synthesis and statement of applicability. |

Weed (2005). |

Framework Weed (2005) Weed (2008) Articles No. |

| Approach | Philosophical Foundation | Adolescent and mental health example and Worked examples of the approach |

|

Meta-ethnography Social constructivist Meta-ethnography |

Meta-ethnography originally was identified a relativist ontology and interpretivist epistemology (France et al., 2019; Noblit and Hare, 1988). Social constructivist meta-ethnography assumes a pragmatist ontology and relativist epistemology (Mohajan & Mohajan, 2022). |

Adolescent mental health example: Lucas et al. (2019) Worked examples: Britten et al (2002, Sattar et al (2021) Social constructivist worked example: McMillan and Soundy (2025) |

| Thematic Synthesis | Thomas and Hardin (2008) do not specifically identify the terms ontology and epistemology. However, it is likely that the ontology is relativism or contextualism. They state qualitative research is “specific to a particular context, time and group of participants” and the epistemology is interpretivist as reviewers actively shape understanding. |

Adolescent mental health example: Broad et al (2017). Worked examples: Thomas and Hardin (2008) Kavanagh et al (2011). |

| Meta-synthesis | Ontology is identified as constructivist assuming that reality is socially constructed and context-dependent and epistemology is interpretivist and knowledge generated by the reviewer by conceptualization and interpretation (Chrastina, 2020) |

Adolescent mental health example: Rodriguez et al. (2024). Worked examples: Aguirre and Bolton (2014). Finfgeld-Connett (2010). Nye et al (2016). |

| Meta-Study | Constructivist ontology identifying socially constructed reality with contextual truths. A single reality is not sought rather multiple interpretations are considered. The epistemology is interpretivist emphasising constructed knowledge (Grass, 2024) |

Mental health example: Watkins et al. (2009). Worked example: Rycroft-Malone et al (2012). Paterson et al (2001). |

| Framework Synthesis | The ontology is likely subtle realist with the attempt to gain useable common findings. The epistemology is partially interpretivist but also structured and deductive and begins within an a priori framework (Carroll et al., 2013b). |

Adolescent mental health example: Viduani et al. (2024). Worked example: Carroll et al. (2013a) Rapid best fit worked example: Shaw et al (2020) |

| Narrative Synthesis | It is likely (because not specifically stated by Popay et al., 2006) that the approach is situated within a pragmatism or post-positivism. The pragmatic positioning is supported as the approach looks to consider how the intervention works, why and for whom (Popay et al 2006; Barnett-Page & Thomas, 2009). This supports a central component of pragmatism which looks to consider what works rather than what is true. |

Adolescent mental health example: Ballesteros-Urpi et al (2019) Worked example: Gross et al., (2016). Le Boutillier et al (2019) |

| Qualitative Meta-analysis | Levit (2018) considers this approach within an emergence epistemology due to the complexity of social life, the idea is to consider new ideas when studies are combined, so knowledge is considered as interpretive and evolving. | Mental health example: de Vos et al (2017) Worked examples: Wu and Levitt (2020).Levitt et al., 2016 |

| Meta Interpretation | Interpretivist epistemology rejecting positivist assumptions of objectivity. Knowledge is considered as situated and socially constructed. Importance is considered as meaning in context. Synthesis process is described as a triple hermeneutic (interpretations of interpretations of interpretations). Value in differences contextually ad methodological as sources of insight. |

Adolescent / mental health example: No identified example. Worked example: Santos et al (2026) |

| Approach | Definition | Aggregated steps/process | Supporting sources |

| Content Analysis | A systematic, rule-governed method for coding and categorising textual data across studies to identify patterns, relationships, and conceptual structures; it can be applied inductively (codes emerge from data) or deductively (a priori categories), and may also quantify findings via counts/tabulations (manifest and latent content), thereby supporting transparent, replicable synthesis. | Preparation & material collection: define topic/keywords and scope; select and delimit literature; set unit of analysis; read and reflect on reports. Category development: build themes/categories a priori and/or derive inductively; specify coding rules and precise category definitions; allow iterative refinement. Coding & data management: code data under categories; organise coded segments in matrices/tables with citations; use software where appropriate. Analytic development: write memos; diagram relationships; interpret meaning in context; analyse frequency/meaning; count/tabulate occurrences. Reliability & transparency: use multiple coders; assess agreement (e.g., Cohen’s kappa); resolve discrepancies through discussion; document category system and rules. Iteration & synthesis: reflect and revise; assess saturation (no new insights) and conceptual fit; integrate patterns into coherent models or synthesised findings. |

Dixon-Woods et al. (2006); Finfgeld-Connett et al. (2014); Hannes & Macaitis (2012); Seuring & Gold (2012); Snilstveit et al. (2012). |

| Meta Aggregation (JBI) | A qualitative synthesis method that avoids reinterpretation of included studies and instead accurately presents findings as intended by original authors. Grounded in pragmatism and transcendental phenomenology, it aims to produce practice-level theory or lines of action for healthcare policy and practice. It is structured like a systematic review and focuses on aggregating findings rather than generating new theory. | Standard JBI process:1. Develop a review protocol (objectives, rationale, peer review).2. Formulate review question using PICo (Population, Interest, Context).3. Define inclusion criteria (participants, phenomena, context, study types).4. Conduct comprehensive search (published + grey literature).5. Appraise methodological quality (JBI checklist).6. Extract data (study details, verbatim findings, supporting quotes).7. Assign plausibility ratings (unequivocal, equivocal, unsupported).8. Three-step synthesis: group findings into categories (≥2 findings per category), then develop synthesized findings as overarching statements.9. Report findings transparently (visual models, progression from findings to synthesis).10. Develop practice recommendations (specific, measurable, context-rich).11. Assess confidence in findings (CONQual rating). | Lockwood et al. (2015); Hannes & Macaitis (2012) |

| Meta-Aggregation general descriptors | A method inspired by quantitative systematic reviews, aiming to produce generalizable statements from qualitative findings. Focuses on common meaning across studies, uses tree-like structures to categorize findings, and avoids theorization or critical interpretation. Purpose: guide practice and policy through inductive generalization. Critiques note risks of reducing rich, context-bound data into thin abstractions and ignoring contradictions. | Core steps (aggregated from multiple sources):- Extract findings from studies.- Categorize findings into themes.- Aggregate themes into recommendations or lines of action.- Present findings in structured format for decision-making.- Compare and contrast grouped data.- Ensure transparency and link recommendations to synthesized findings. | Bergdahl (2016); Booth (2024); Habersang & Reihlen (2024) |

| Descriptive synthesis | Descriptive synthesis that summarises findings from individual studies without transforming them into higher-level abstractions; maintains fidelity to original data. | • Identify relevant studies • Extract descriptive findings from each study • Organise findings thematically or categorically • Present findings in a structured narrative or tabular format • Avoid reinterpretation or abstraction beyond the original scope |

Habersang & Reihlen |

| Thematic summaries | Organises findings under salient themes, often structured by a conceptual framework; uses tabulation and reports divergence. | • Categorise studies into thematic groups (e.g., intervention type, participants, outcomes) • Analyse and synthesise findings within each thematic group • Use tabulation; identify divergent findings • Synthesise under each theme |

Snilstveit et al. (2012) |

| Content analysis (fledgling approach) | Condenses text into content-related categories; aggregative technique used as a fledgling synthesis approach. | • Categorise textual content into content-related groups (specific procedural details not expanded in file) | Barnett-Page & Thomas (2009) |

| Qualitative meta summary (Sandelowski & Barroso) | Aggregative rather than transformative; quantifies frequency of findings and can calculate effect-size-like metrics for qualitative data. | • Tabulate frequencies of qualitative findings • Compute qualitative effect-size-like metrics (details not expanded in file) |

Barnett-Page & Thomas (2009); Sandelowski & Barroso |

| Approach | Definition | Aggregated steps/process | Supporting sources |

| Interpretive Synthesis | A synthesis method that reconfigures findings across multiple studies to develop new concepts, frameworks, and theory. It avoids fixing concepts early, acknowledges the authorial voice, prioritises plausibility and transparency, and integrates qualitative (and quantitative) evidence through interpretation. It is presented as the most interpretive and abstract form of synthesis (often drawing on meta-ethnography) and focuses on understanding patterns, mechanisms, and causal relationships across qualitative studies. | Several steps are involved: 1) Avoid fixing concepts early; let theoretical structures emerge from the data. 2) Extract first-order concepts across included studies. 3) Develop second-order categories/themes that cut across studies. 4) Conduct third-order interpretations to produce new conceptualisations/theory. 5) Use reciprocal translation (translate concepts across studies) and constant comparison to refine links among concepts and categories. 6) Identify categories and patterns while preserving contextual integrity (retain the meaning-in-context of source findings). 7) Build theory inductively and articulate causal/relational explanations where appropriate. 8) Ensure plausibility and transparency of interpretive decisions (authorial stance explicit), rather than prioritising reproducibility. | Dixon-Woods et al. (2006); Habersang & Reihlen (2024); Hoon (2013). |

| Meta grounded theory | An inductive synthesis that applies grounded theory methods (e.g., constant comparison, theoretical sampling, memoing, and multi-level coding) across primary grounded theory studies (and sometimes broader qualitative literature) to produce a higher-order, abstract theory (grounded formal theory) that generalises beyond the original studies. It emphasises emergent theory building, process-orientation, and conceptual integration across studies, matching synthesis procedures to the methodological logic of the included grounded theories. | Several steps 1) Define & scope the review: establish inclusion/exclusion criteria, fields, sources, search terms; maintain theoretical sensitivity (openness to emergent concepts). 2) Search & select studies: perform database searches; filter by criteria; use citation tracking; ensure rigour of included grounded theory studies. 3) Prepare data for synthesis: extract study findings/segments; assemble grids/matrices for cross-study comparison. 4) Substantive/open coding (often line-by-line, in-vivo): code using participants’ words and short phrases; cluster similar codes; raise terms to concepts through constant comparison. 5) Axial/relational coding: develop relationships among concepts/categories; specify properties, dimensions, and linkages; preserve contextual integrity. 6) Theoretical coding: use coding families (e.g., Glaser’s) to connect categories and elaborate theoretical relationships. 7) Memoing & diagramming: write analytic memos; map relations and processes; iteratively refine interpretive insights and category structures. 8) Theoretical sampling & saturation: revisit studies (sample concepts, not just participants) until no new concepts emerge; test category fit across cases. 9) Core category & basic processes: identify central categories and basic social/psychological processes (multi-stage patterns of change) that integrate the theory. 10) Integrate into grounded formal theory: consolidate categories/processes into mini-theories and an overarching explanatory framework; structure and present the theory with matrices/diagrams and transparent decision trails. | Barnett-Page and Thomas (2009); Chen and Boore (2009); Dixon-Woods et al. (2005); Eaves (2001); Finlayson and Dixon (2008); Hannes and Macaitis (2012); Nye (2016); Schick-Makaroff (2016); Whittmore et al (2014); Wolfswinkel et al (2013). |

| Miles & Huberman’s technique | Cross-case interpretive approach using meta-matrices and thematic coding to compare and integrate findings across studies. | • Develop a start list of codes • Conduct within-case analysis (code & summarize each study) • Add categories and subthemes as needed • Create summary tables for each study • Perform cross-case analysis to identify commonalities and differences |

Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) |

| Cross-case analysis | Systematic comparison of categories across studies to refine and align constructs; noted as transparent, with limited guidance on sampling/appraisal. | • Systematic identification of categories • Cross-referencing and refinement across studies |

Finlayson & Dixon (2008) |

| Translation synthesis | Constructivist synthesis using reciprocal translation of studies into one another to build interpretations from multiple perspectives. | • Translate concepts across studies • Engage in hermeneutic or dialectic processes • Construct informed reconstructions of participant meanings |

Hoon (2013) |

| Concept analysis | Systematically clarifies a concept by extracting its attributes from the literature, definitions, and case examples to specify meaning in a domain/context. | • Determine purpose and aims • Delineate concept boundaries • Review literature and definitions • Analyse data sources for attributes • Develop prototype and compare with contrary/borderline cases • Test practical significance • Formulate defining features • Relate to theoretical or practical application |

Schick-Makaroff (2016) |

| Concept synthesis | Identifies concepts, viewpoints or ideas; focuses on defining attributes and developing a synthesis model. | • Identify and define concepts • Develop a synthesis model |

Tricco et al. (2016) |

| Thematic analysis | Flexible interpretive method to identify, analyse and report themes; can be data-driven (themes emerge) or theory-driven (pre-specified). | • Extract findings from studies • Line-by-line coding / code data into themes • Group themes into categories • Summarise findings under thematic headings and/or create summary tables • Interpret patterns across studies (data-driven or theory-driven) |

Dixon-Woods et al. (2006); Hannes & Macaitis (2012) |

| Thematic synthesis | Draws on thematic methods used in primary research—coding, theme development and analytical interpretation—to move beyond description. | • Line-by-line coding of findings • Develop descriptive themes • Generate analytical themes (go beyond description to implications/recommendations) |

Snilstveit et al. (2012) |

| Textual narrative synthesis | Groups studies into homogeneous sets and compares them using structured summaries; highlights context and heterogeneity. | • Group studies into homogeneous sets • Compare using structured textual summaries |

Barnett-Page & Thomas (2009); Developers: Lucas et al. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).