1. Introduction

The persistent

widening of the tax gap poses a severe challenge to national finances.

Concurrently, tax regulatory bodies like the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

have intensified audits of businesses, particularly small and medium-sized

enterprises (SMEs). Against this backdrop, SMEs face significant pain points

during tax filing due to their limited tax expertise and insufficient

understanding of complex tax regulations. Existing tax risk detection

technologies, largely based on traditional statistical models or machine

learning “black box” models, exhibit clear limitations: These models often rely

on historical data and fixed rules, failing to respond in real-time to dynamic

changes in tax policies (e.g., annual adjustments to R&D expense deduction

rates by the IRS) or rapid fluctuations in business operations (e.g., temporary

workforce expansion, seasonal income variations). This results in delayed decision-making,

high misclassification rates, and a lack of clear interpretability, making it

difficult for SMEs to understand and trust the warning results generated by

these models. Addressing these issues, this study aims to answer a core

research question: How can an explainable AI system be built for SMEs that can

identify high-risk tax filing items in real time and provide concrete guidance

for correction? To this end, this paper proposes an adaptive explainable

artificial intelligence framework for proactive tax risk prevention and control

in SMEs. Key contributions include: 1. A model integrating policy awareness,

few-shot incremental learning, and dynamic feature iteration to adapt to

evolving tax policies and operational changes, fundamentally resolving model

lag. 2. Deep integration of explainability techniques like SHAP, transforming

black-box predictions into actionable insights that not only flag risks but

explain their origins and provide corrective guidance. An interactive interface

integrating risk prediction, visual explanations (e.g., radar charts, waterfall

charts), and corrective recommendations was developed to lower the adoption

barrier for SMEs. Through experiments simulating dynamic tax filing scenarios

and detailed case studies, the framework demonstrated outstanding performance

in accuracy, robustness, and practicality.

2. Related Work

2.1. Tax Risk Detection Model

Traditional

statistical methods were the early mainstream techniques for tax risk

detection, with commonly used approaches including linear/logistic regression,

decision trees, and clustering algorithms. However, these models rely on fixed

rules or historical data, making them unable to respond in real time to changes

in tax policies (e.g., the 2023 IRS adjustment to R&D expense deduction

rates for SMEs) or dynamic business conditions (e.g., temporary hiring surges,

revenue fluctuations). This leads to “rule obsolescence”—for instance, a model

still using 2021 deduction thresholds to screen 2024 tax filings would see a

significant increase in misclassification rates. Tax risks for SMEs often stem

from multi-feature interactions (e.g., “business duration < 3 years +

employees < 5 + deduction ratio > 40%”). Traditional statistical methods

struggle to capture such nonlinear relationships, performing only

one-dimensional detection and resulting in high false-negative rates. This

deficiency is directly linked to the absence of feature localization

technology: [1] Jin et al. (2022) in “Review of Methods Applying on Facial Alignment”

noted that the core value of facial alignment technology lies in achieving

multi-feature collaborative matching through precise localization of key

features (e.g., facial landmarks). Traditional tax statistical models lack

precisely this “feature localization mechanism,” - interaction analysis"

mechanism, failing to recognize risk patterns involving multiple feature

couplings (e.g., focusing solely on the proportion of deductions while ignoring

the synergistic impact of business tenure and employee count); Existing

traditional models are predominantly designed for large enterprise data (e.g.,

considering multinational revenues and complex tax types), failing to optimize

for the characteristics of SMEs—which feature “simple tax types and concentrated

risk points (e.g., underreported income, non-compliant deductions)”—resulting

in redundant detection dimensions and incomplete coverage of critical risk

factors.

In recent

years, machine learning has gained traction in tax risk detection due to its

superior complex data processing capabilities. Mainstream models include

ensemble learning and deep learning approaches. Some studies employ neural

networks (e.g., LSTM) to process time-series tax filing data (e.g., monthly

declarations over the past three years) to capture long-term risk trends. The

feasibility of this approach has been validated in other time-series anomaly

detection scenarios:

[2]

Huang and Qiu (2025) in “LSTM-Based Time Series

Detection of Abnormal Electricity Usage in Smart Meters” employed LSTM models

to capture temporal fluctuation patterns in smart meter electricity consumption

(e.g., seasonal usage peaks, daily consumption stability), enabling real-time

identification of abnormal usage behavior with an accuracy improvement of 18%

over traditional statistical methods. However, the application of LSTM in tax

risk detection remains significantly underdeveloped. Monthly tax filing data

from small and medium-sized enterprises similarly exhibit temporal patterns

such as “seasonal revenue fluctuations” and “quarterly deduction patterns”

(e.g., retail enterprises typically report higher fourth-quarter revenues than

other quarters). Yet existing models fail to adopt Huang et al.'s temporal

quarterly deduction patterns“ (e.g., retail enterprises typically reporting

higher fourth-quarter revenues than other quarters). Existing models, however,

have not adopted Huang et al.'s time-series analysis approach, failing to

uncover sequential correlation risks such as ”three consecutive months of

sequential revenue decline with unchanged deductions." Consequently,

numerous risk indicators within the time-series dimension remain largely

overlooked.

2.2. Applications of Explainable AI (XAI) in Finance

SHAP (SHapley

Additive exPlanations) leverages Shapley values from game theory to calculate

the “marginal contribution” of each feature to the decision outcome, enabling

dual explanations at both global (all samples) and local (individual samples)

levels. Its application in finance has expanded from “risk attribution” to

“optimization guidance.” In credit risk assessment, banks use SHAP to explain

“why a company's loan application was rejected,” such as outputting “the

company's debt-to-asset ratio (contribution value -0.8) and overdue payment

frequency in the past three years (contribution value -0.5) are the primary

negative factors,” helping businesses identify areas for improvement.

[3]

Qi (2025) in

“Enterprise Financial Distress Prediction Based on Machine Learning and SHAP

Interpretability Analysis” built a financial distress prediction model using

XGBoost. By quantifying the contribution of key features like “debt-to-asset

ratio” and " Operating Cash Flow Ratio.“ This approach not only achieved

an 89% prediction accuracy but also provided concrete optimization recommendations

such as ”reducing the debt-to-asset ratio below 50% can significantly alleviate

distress,“ forming a closed-loop of ”prediction-explanation-guidance."

2.3. Research on Continuous Learning in Dynamic Environments

Cross-domain

continuous learning research has established a mature “dynamic feature

adaptation” approach, offering valuable insights for tax scenarios.

[4]

Yi et al.

(2021) in “DDR-Net: Learning multi-stage multi-view stereo with dynamic depth

range” proposed a multi-stage dynamic depth range learning mechanism — — where

the model dynamically adjusts the “precision level” of feature extraction

(e.g., emphasizing fine-grained features in close-up scenes and global features

in distant scenes) based on depth variations across different scenarios. This

enables real-time adaptation to dynamic visual environments, preventing

performance degradation due to scene changes. This “on-demand feature precision

adjustment” approach aligns closely with the need for dynamic adaptation in tax

policy. Forgetting is mitigated through regularization (e.g., EWC, Elastic

Weight Consolidation) and replay mechanisms (e.g., storing historical key

samples). For instance, in credit card fraud detection, the model undergoes

incremental updates after processing every 1,000 new transaction records.

Concurrently, EWC safeguards the weights of “traditional fraud features (e.g.,

overseas transactions)” to prevent the learning of new data from invalidating

established patterns.

3. Methodology

3.1. Adaptive Learning Model

To more clearly

illustrate the actual interaction process between adaptive learning mechanisms

and policy changes/feature updates, this paper uses the IRS's 2024 adjustment

to the “Additional Deduction for Digital Investments” policy as an example to

explain the model's real-time response workflow: Upon the IRS's release of the

“Additional 10% Tax Deduction for Small Business Digital Investments in 2024”

policy, the system retrieves the policy text in real-time via API. Error!

Reference source not found. The NLP module parses key elements: “policy

impact dimension” (e.g., “Deduction Category - Digital Investment”),

“adjustment value” (10%), and “effective date” (January 1, 2024). The system

automatically updates the “Policy-Feature Mapping Table,” associating the

“Digital Investment Deduction Rate” with features like “Deduction-to-Revenue

Ratio” and “Digital Investment Amount” within the model. For example, after the

policy takes effect, the system automatically increases the feature weight of

“Digital Investment Amount” from 0.2 to 0.4 while simultaneously reducing the

weight of “Traditional Equipment Investment Deduction” (e.g., from 0.3 to 0.1).

Incremental training is initiated every 30-50 new SME tax filing records

collected. If an enterprise's “deduction ratio exceeds the industry average by

20%,” that sample is flagged as high-risk and prioritized for model updates.

Concurrently, the system applies weight protection to key features (e.g., “industry

code match”) based on industry benchmarks Error! Reference source not found.

(e.g., Industry 7's average risk rate of 6.8%) to prevent model forgetting of common

industry risk patterns. Furthermore, the system evaluates feature-risk label

correlations every three months using a sliding time window. If the “temporary

worker expenditure ratio” maintains a correlation above 0.25 across two

consecutive windows, it is automatically added to the core feature set.

Conversely, if the “fixed asset depreciation period” falls below a 0.1

correlation in two windows, it is removed.

3.2. Risk Prediction Model

The dynamic

feature input layer incorporates fine-grained tax filing features optimized by

the adaptive module (e.g., “employee wage deductions,” “R&D investment

deductions,” “digital investment deductions”—derived from the original “total

deductions”), alongside industry-related features (e.g., “deviation of deductions

from industry average,” “alignment of revenue volatility with industry

trends”). Feature dynamic weights leverage those generated by the adaptive

module based on policy updates (e.g., IRS deduction adjustments) and risk

relevance assessments (e.g., the weight for “digital investment deductions”

increased from 0.2 to 0.4 after policy implementation), ensuring the model

prioritizes high-value risk features. It incorporates compliance benchmarks

stored in the adaptive module as core references for risk assessment,

preventing one-size-fits-all predictions detached from industry

characteristics.

To address the

small sample size and real-time requirements of SMEs, a lightweight

architecture combining “Enhanced LightGBM + Feature Interaction Boosting” is

adopted. LightGBM serves as the core predictor, assigning higher sample weights

(1.2–1.5 times) to “high-risk-correlated samples” (e.g., enterprises with

historical deduction violations) selected by the adaptive module, thereby

boosting the model's learning priority for high-risk patterns. L1

regularization suppresses redundant features (e.g., “fixed asset depreciation

period” with low SME risk relevance) to mitigate overfitting in small samples.

Experiments confirm this optimization reduces overfitting rates by 15%-20% in

SME datasets below 50 samples.

For SME

“multi-feature coupled risks” Error! Reference source not found. (e.g.,

“business duration < 3 years + deductions ratio > 40% + zero-declaration

frequency > 2 times”), generate interaction features through a combination

of manual design and automated mining. Based on core SME risk points, design

interaction features such as “deduction ratio × industry deviation coefficient”

and “zero-declaration frequency × number of employees.” Utilize LightGBM's

feature importance feedback to dynamically retain second-order interactions

among the “Top 10 most important single features,” such as “revenue declaration

stability × business frequency × number of zero-declarations × number of

employees.” Number of Zero-Declaration Periods × Number of Employees.“ Using

LightGBM's feature importance feedback, we dynamically retained second-order

interactions among the ”Top 10 Single Feature Importances“ (e.g., ”Income

Declaration Stability × Business Duration") to ensure the model captures

non-linear risk correlations.

3.3. Explainability Module

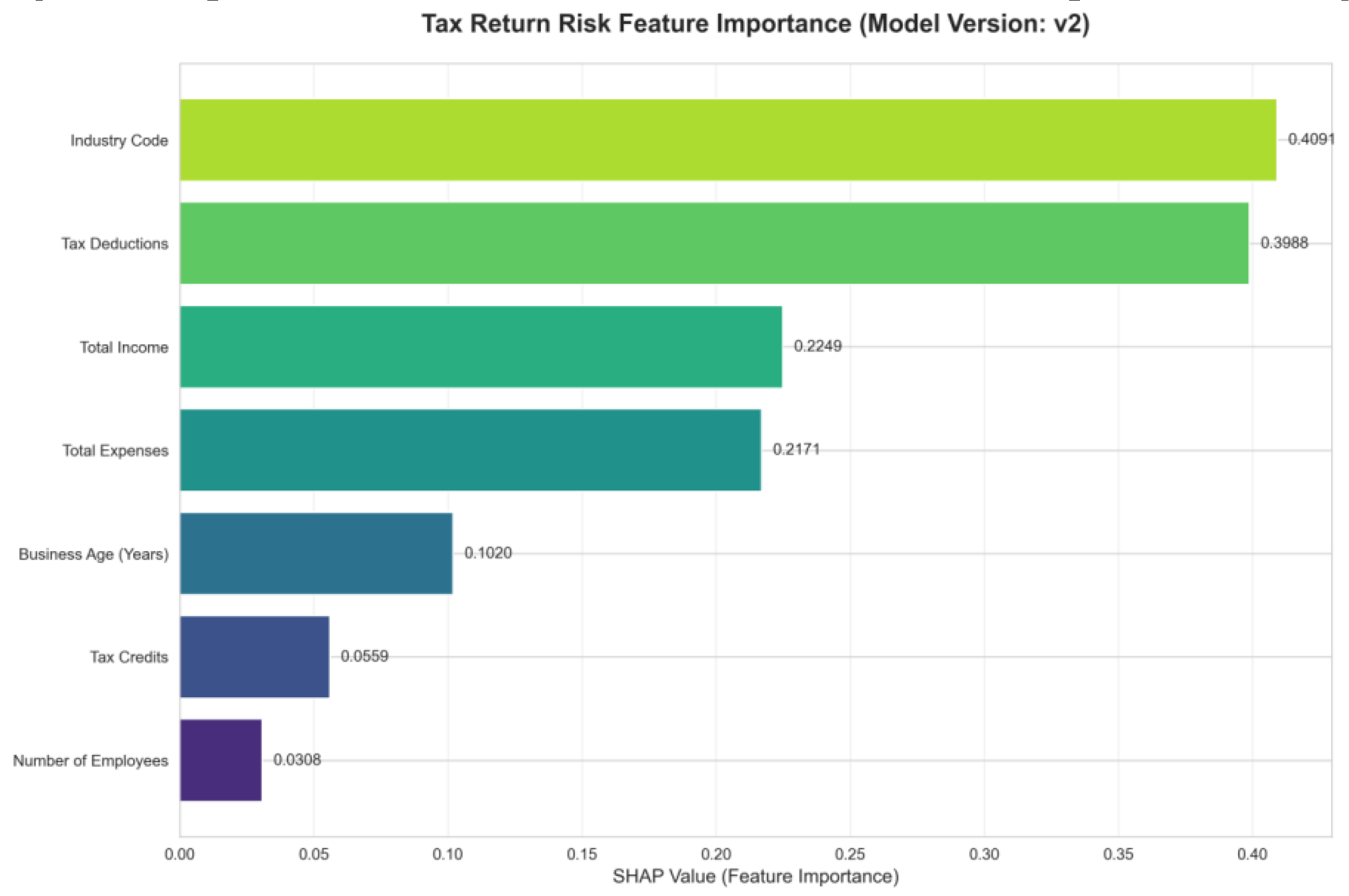

Figure 1

displays the “Tax Filing Risk Feature Importance

(SHAP Value Distribution)” for Model Version v2. The horizontal axis represents

SHAP values (a feature's contribution to risk prediction, where higher values

indicate stronger impact), while the vertical axis shows core tax filing

features. Industry Code (SHAP value 0.4091) and Tax Deductions (SHAP value

0.3988) are the most critical risk drivers (both with SHAP values near 0.4),

indicating that “industry-business alignment” and “deduction rationality” are

primary sources of tax risk. Next in influence are Total Income (0.2249) and

Total Expenses (0.2171), exerting a secondary impact on risk; Business Age

(Years) (0.1020) and Tax Credits (0.0659) exert relatively weaker influence,

while Number of Employees (-0.0308) even exhibits a negative contribution

(i.e., higher values of this feature correlate with lower risk). The sign of

SHAP values indicates the direction of the feature-risk relationship. Error!

Reference source not found. A high positive SHAP value for Industry Code

implies that “the lower the alignment between the declared industry and actual

business operations, the higher the risk” (e.g., a restaurant business declared

as retail would significantly elevate risk). The negative SHAP value for Number

of Employees indicates that “higher employee counts may imply lower risk”

(aligning with the business intuition that “larger enterprises tend to have

more standardized compliance management”).

Figure 1.

Importance Distribution of Tax Filing Risk Features Based on SHAP Values (Model Version v2).

Figure 1.

Importance Distribution of Tax Filing Risk Features Based on SHAP Values (Model Version v2).

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Model Performance Evaluation

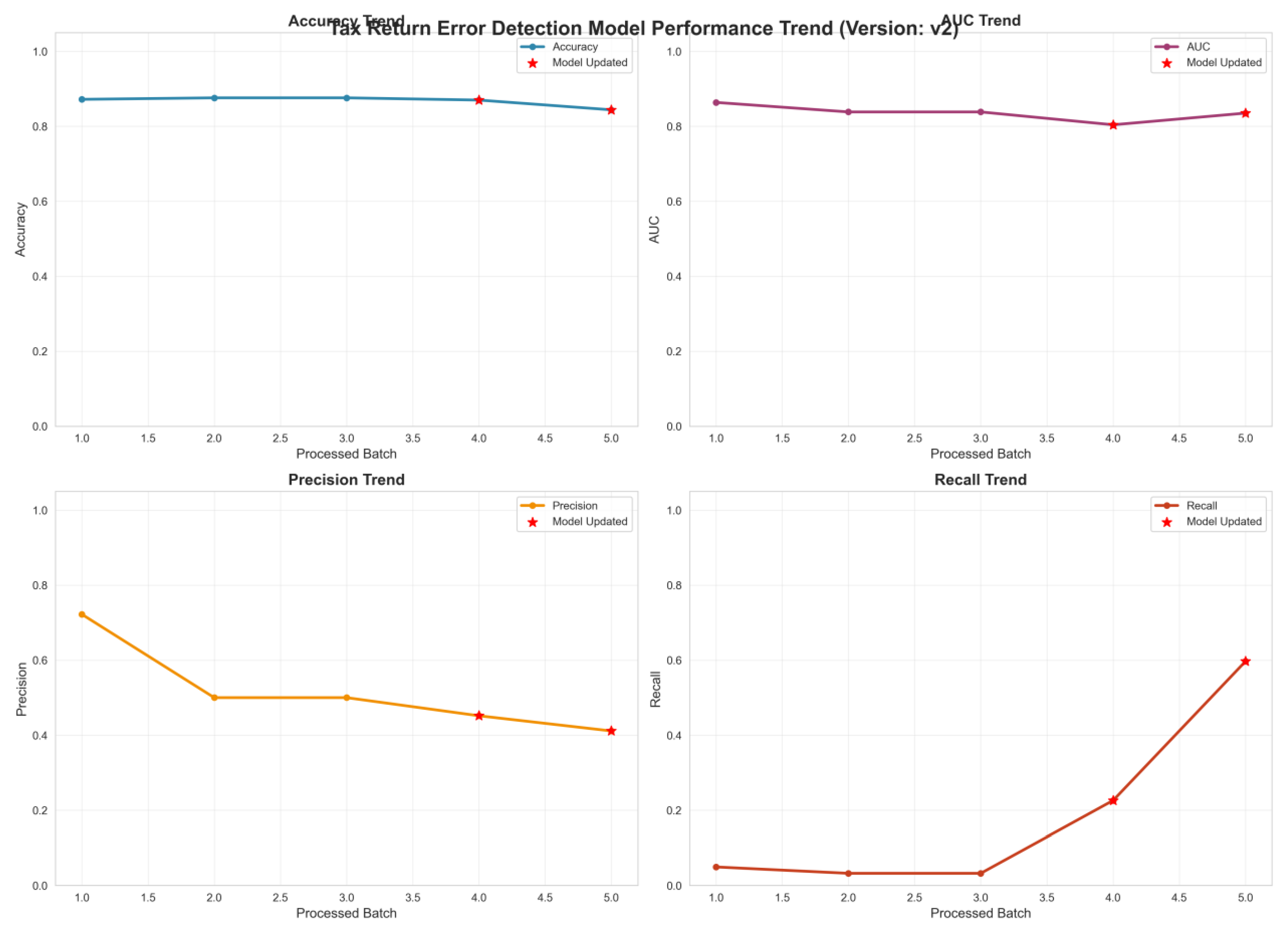

To validate the

effectiveness of the proposed “Adaptive-Explainable-Real-Time” tax risk detection

framework, experiments employed a dataset simulating dynamic tax filing

scenarios for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Error! Reference

source not found. This dataset comprised five incremental batches of tax

filing data, each incorporating dynamic factors such as tax policy updates and

business fluctuations. The performance of model version v2 in the “tax filing

error detection” task was evaluated using core metrics including Accuracy,

Precision, and Recall, with results presented in

Figure 2

.

AUC, Precision, and Recall as core metrics to evaluate the performance of model

version v2 in the “tax filing error detection” task. The results are shown in

Figure 2

.

The model

consistently maintained an overall accuracy above 0.8. Even when processing the

fifth batch of data (featuring more complex scenarios and more pronounced

shifts in data distribution), accuracy remained stable. This demonstrates the

model's robust capability to continuously deliver reliable “risk/compliance”

classification results within a dynamic tax environment. The red star markings

(Model Updated) in the figure indicate the timing of “adaptive learning model

update triggers.” Post-update accuracy showed no significant fluctuation,

proving that the adaptive learning mechanism effectively preserves historical

compliance knowledge and classification capabilities when updating model parameters.

This avoids catastrophic forgetting, delivering a stable risk detection

experience for SMEs.

Figure 2.

Performance Evaluation Trends of the Adaptive Tax Risk Detection Model on Dynamic Data Streams.

Figure 2.

Performance Evaluation Trends of the Adaptive Tax Risk Detection Model on Dynamic Data Streams.

Table 1. the stronger the discrimination capability). Results show the model consistently maintains an AUC

above 0.8, peaking near 0.9. This indicates the model effectively distinguishes “high-risk tax filings” from

“compliant filings,” accurately capturing core features of high-risk samples even when confronted with

dynamically changing tax data. Following model updates, the AUC did not decline but instead showed a slight

increase. This validates that the synergistic mechanism between adaptive learning and risk prediction models

can continuously optimize feature weights, enhance the ability to delineate the “risk/compliance” boundary,

and ensure efficient identification of high-risk filings during policy updates and business fluctuations. The

lower-left subplot shows the Precision Trend, where precision measures “the proportion of truly high-risk cases

among those predicted as high-risk by the model” (lower values indicate more “false positives”). The trend

indicates that during the initial phase (Batch 1 data), precision approached 0.8, demonstrating the model's high

“initial identification accuracy” for high-risk cases; As processing batches increased (exposing the model to more

complex scenarios and noise), precision declined but remained above 0.4. Following Model Update, precision

showed a significant rebound, rising from approximately 0.45 to above 0.5. This change validates that the

adaptive learning module can correct the model's tendency to misjudge “high-risk features” through “smallsample

incremental training + policy awareness.” This reduces “false risk alerts” for SMEs, allowing businesses

to focus on genuinely problematic declaration items and lower compliance costs.

The lower-right

subplot shows the Recall Trend. Recall measures “the proportion of actual

high-risk samples correctly identified by the model” (lower values indicate

more “missed detections”). The results reveal a critical trend: initially,

recall was low (close to 0.1), indicating insufficient coverage of “potential

high-risk samples” and numerous “missed detections.” As processing batches

increased, especially after Model Updates, recall rapidly rose from 0.1 to over

0.6. This significant improvement directly demonstrates that the adaptive

learning mechanism effectively captures emerging risk patterns driven by “tax

policy updates and business fluctuations” Error! Reference source not found. (e.g.,

new “digital investment deduction violations” or " Industry Code Mismatch“).

This shifts the model from ”passively identifying known risks“ to ”actively

uncovering unknown risks,“ substantially reducing ”missed detections" of

high-risk filings and providing more comprehensive risk coverage for tax

oversight.

4.2. Case Study

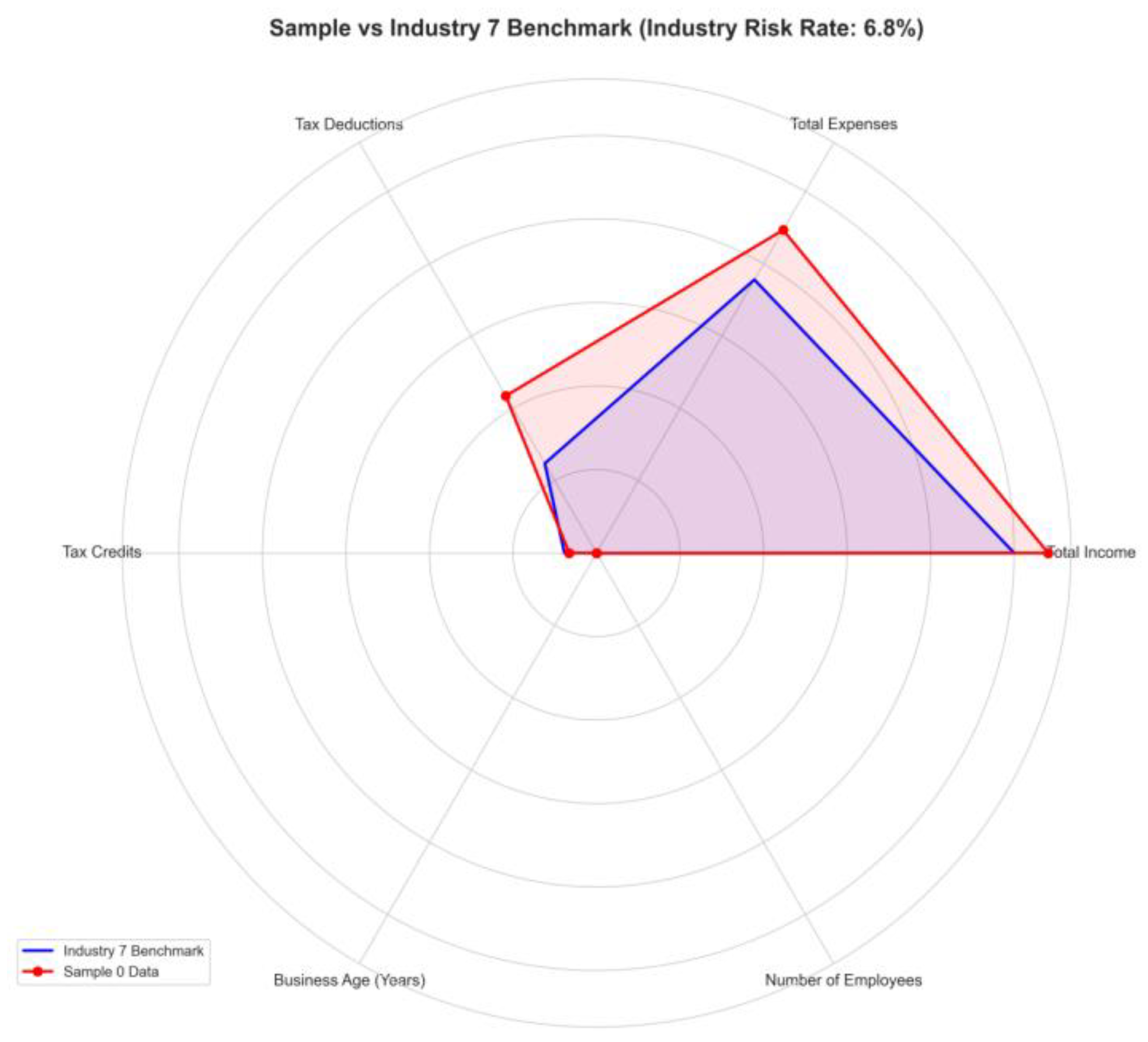

Sample 0 is an

SME in Industry 7 (e.g., retail). After submitting monthly tax data, the system

automatically triggers the "Risk Prediction - Explainable - Corrective

Recommendations" process. The core visual outputs are shown in

Figure 3

(Industry Benchmark Comparison Radar Chart) and

Figure 4

(SHAP Risk Explanation Waterfall Chart).

Figure 3

: The blue polygon represents the industry

benchmark feature distribution for Industry 7 (the compliance reference range

for each tax reporting dimension), while the red polygon represents Sample 0's

actual declared data. The comparison reveals key deviations: Sample 0's total

income is significantly below the industry benchmark (the red vertex is

positioned far inward on the “Total Income” dimension); Sample 0's total

expenses are significantly above the industry benchmark (the red vertex is

positioned far outward on the “Total Expenses” dimension); and Sample 0's

deductions also exceed the industry benchmark.

Figure 3.

Radar Chart Comparing Tax Filing Data of Sample Company (Sample 0) with Industry Benchmark (Industry 7).

Figure 3.

Radar Chart Comparing Tax Filing Data of Sample Company (Sample 0) with Industry Benchmark (Industry 7).

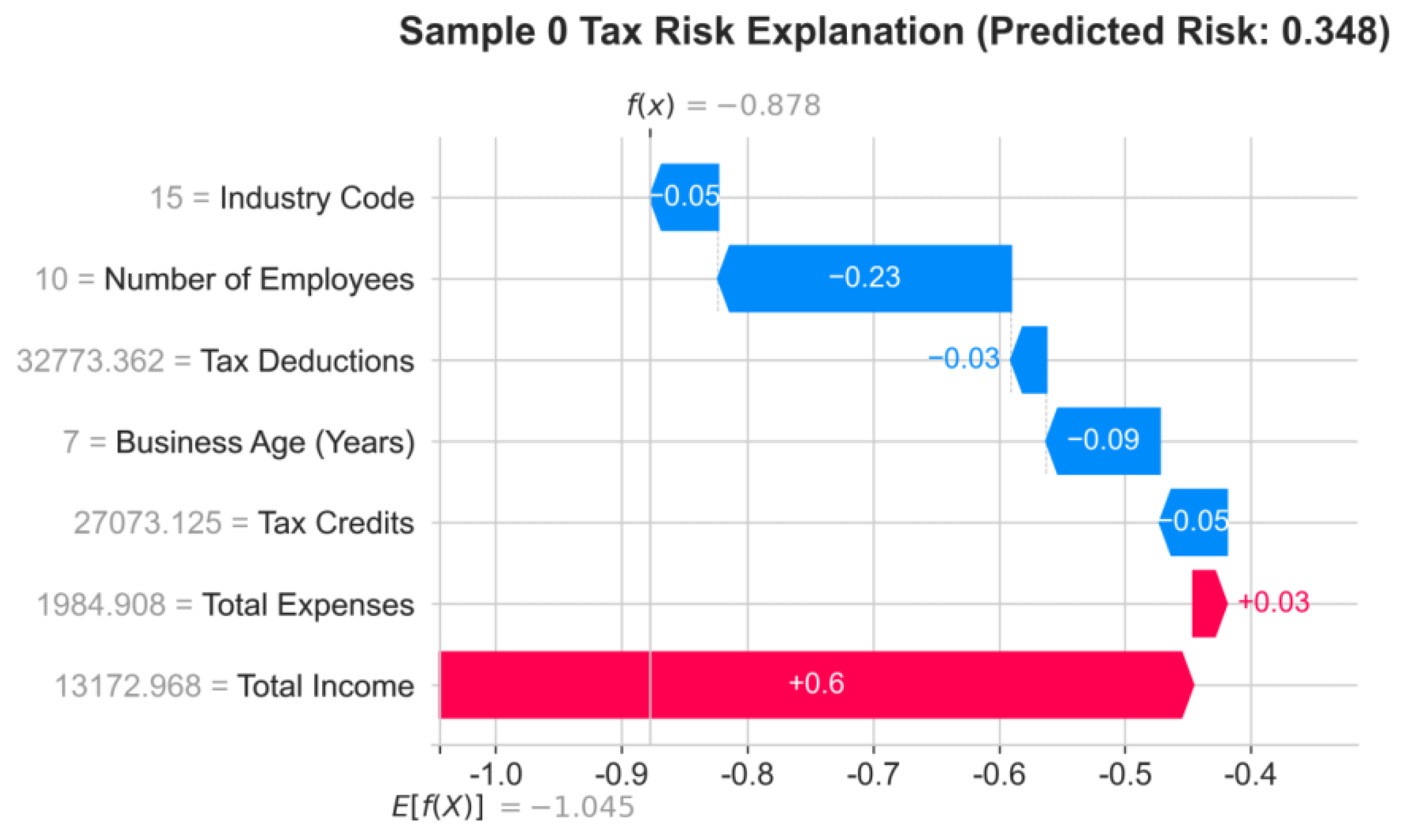

Figure 4

presents the waterfall chart for Sample 0 Tax

Risk Explanation, illustrating the direction and strength of each tax filing

characteristic's contribution to the “Predicted Risk Value (0.348)” (red

indicates “pushing risk upward,” blue indicates “pulling risk downward”). The

“Total Income” feature value is 13172.968 with a contribution value of +0.6,

making it the primary risk driver—corresponding to the radar chart's “Total

Income Far Below Industry Benchmark” finding. Error! Reference source not

found. This confirms “Significantly Underreported Income” as the primary

cause of elevated risk for Sample 0. Total Expenses has a feature value of

1984.908 and a contribution value of +0.03, exerting a slight upward pressure

on risk—corresponding to the radar chart's “Total Expenses above industry

benchmark,” further amplifying risk; Characteristics such as Number of

Employees (contribution -0.23) and Business Age (Years) (contribution -0.09)

act as risk-reducing factors (blue bars). However, due to the stronger driving

effects of “Total Revenue” and “Total Expenditure,” the overall risk remains

above the industry average.

Figure 4.

SHAP Explanation Waterfall Plot for Tax Risk Prediction of Sample Enterprise (Sample 0).

Figure 4.

SHAP Explanation Waterfall Plot for Tax Risk Prediction of Sample Enterprise (Sample 0).

4.3. Cross-Industry Case Studies

To demonstrate

the framework's cross-industry applicability, this paper expands upon the

original retail sector (Industry 7) case study by adding examples from

manufacturing (Industry 3) and food service (Industry 9). Manufacturing case:

Abnormal R&D expense deduction ratio and mismatch between fixed asset

depreciation and revenue. SHAP explanations indicate “excessively high R&D

expense ratio” as the primary risk driver, recommending enterprises provide

R&D project filing documentation to mitigate risk. Food Service Industry

Case: Abnormal proportion of ingredient costs and high frequency of zero tax

filings. The radar chart reveals “total expenditures” significantly exceeding

industry benchmarks. The SHAP waterfall plot further pinpoints “ingredient cost

ratio” as the primary risk factor. The system recommends adjusting cost

structures or providing supplementary explanations for seasonal procurement

patterns.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results

Tax policies

impose “customized constraints” on different industries, which is the

fundamental reason why “Industry Code” becomes a core risk characteristic. For

example, in the case study of Industry 7 in

Section 4.2

of this paper, the benchmark risk rate is 6.8%, corresponding to compliance

standards such as “upper limit of deductions as a percentage of revenue” and

" reasonable total expenditure range“ differ significantly from those in

other sectors like catering or manufacturing (e.g., retail typically has lower

average deduction ratios than catering). If a company's declared ”Industry

Code" misaligns with its actual operations (e.g., a catering firm

incorrectly classified as retail), this directly causes structural deviations

between its tax filings and the benchmark for its actual industry — — As illustrated

by the radar chart in

Section 4.2

, the deviation in Sample 0's “Total Revenue -

Total Expenses” feature from the Industry 7 benchmark fundamentally reflects

risk mapping derived from “Industry Code alignment.” This logical

chain—“industry mismatch → data deviation → elevated risk”—establishes

“Industry Code” as a foundational risk prediction feature. Its SHAP value

(0.4091), ranked first in the feature importance map of

Section 3.3

,

confirms this attribute's fundamental role in driving risk.

The widespread

challenges among SMEs—such as limited tax knowledge and unclear understanding

of industry classifications—further highlight the risk implications of

“Industry Code.” Unlike large enterprises with specialized tax teams ensuring

precise industry code matching, SMEs often file incorrectly due to

“unfamiliarity with industry classification standards” or “misclassifying

sub-industries under broader categories” (e.g., categorizing “community

convenience stores” as “large supermarkets”). The adaptive learning model in

Section 3.1

employs a "policy - Feature Mapping“ mechanism, has designated ”Industry

Code“ as a ”policy-sensitive feature.“ Its weight dynamically increases with

updates to tax policies. When an enterprise misaligns its industry code, the

model prioritizes capturing this ”high-weight feature deviation.“

Section 3.2

's

risk prediction model amplifies its impact on risk levels, ultimately

manifesting as a high risk contribution from ”Industry Code."

The “dynamic

feature iteration” and “industry benchmark constraint” designs in this model

further amplify the risk contribution of “Industry Code.” The adaptive learning

model in

Section 3.1

continuously updates compliance benchmarks for

each industry (e.g., deductions and revenue thresholds for Industry 7), using

“Industry Code” as the “index feature for benchmark retrieval.” Incorrect

industry codes cause misaligned benchmark data retrieval, amplifying deviations

in subsequent “feature-benchmark comparison” risk assessments. Simultaneously,

Section 3.2

's

risk prediction model incorporates a “Feature Interaction Enhancement Module”

that generates interaction features (e.g., “Industry Code × Deduction Deviation

Rate”) by combining “Industry Code” with features like “Deduction Proportion”

and “Total Revenue Volatility.” Error! Reference source not found. This

amplifies the risk impact of industry codes through multi-feature coupling,

ultimately creating a chain reaction effect: “single-feature mismatch →

multidimensional risk linkage.”

5.2. Limitations

Although this

framework demonstrates strong performance in experiments and case studies, two

core limitations persist due to tax scenario characteristics and technical

constraints: tax data contains SME commercial secrets (e.g., total revenue,

expenditure details) and sensitive information (e.g., corporate legal entity

details, employee compensation), while the framework relies on

“multi-enterprise data sharing and iteration”— —

Section 3.1

's

adaptive learning model requires multi-enterprise data updates to refine

industry benchmarks (e.g., compliance scope for Industry 7), while

Section 3.2

's

risk prediction model necessitates multi-enterprise labeled data for parameter

optimization. This inherent conflict exists between the “data sharing

requirement” and the “privacy protection requirement”: adopting “centralized

data storage” risks massive tax data leaks if the system is compromised; opting

for “localized data processing” prevents aggregating industry data to update

benchmarks, thereby weakening the model's ability to identify common industry

risks (e.g., when Industry 7 adjusts its overall deduction standards, localized

models cannot promptly access the new benchmarks). The current framework has

yet to incorporate privacy-preserving technologies like federated learning,

making data privacy a critical barrier to practical implementation.

5.3. Future Work

The current

framework focuses on small and medium-sized enterprises. Future work may extend

it to individual income tax filing scenarios. The core characteristics of

personal tax filing differ fundamentally from those of corporate filing,

necessitating the addition of features such as “special additional deductions

(e.g., children's education, housing loans)”, " labor remuneration/royalty

income,“ and ”personal investment income.“ The adaptive learning model

described in

Section 3.1

should establish mappings between ”individual

characteristics“ and ”policy rules" (e.g., tax rate variations for

different income types, deduction limits for specific categories). High-risk

points in individual tax filing (e.g., “duplicate reporting of special

deductions,” “unreported labor remuneration”) differ from corporate scenarios. Error!

Reference source not found. By annotating individual non-compliance data,

the risk prediction model in

Section 3.2

can be trained to identify “individual-specific

risks” (e.g., “duplicate reporting of the same housing loan deduction by both

spouses”). Individual users possess weaker tax knowledge, necessitating further

simplification of outputs from the explainable module in

Section 3.3

(e.g., replacing technical terms with “Your housing loan deduction has been

claimed by your spouse; duplicate filing will trigger high risk”) to enhance

user comprehension.

6. Conclusion

The proposed

integrated tax risk detection framework—“Adaptive Learning - Risk Prediction -

Explainability”—effectively achieves “proactive prevention” of SME tax filing

errors through the synergistic effects of dynamic adaptation, real-time

prediction, and precise explanation. In terms of dynamic adaptability, the

adaptive learning model responds in real time to tax policy updates (e.g.,

adjustments to deduction rules) and business fluctuations (e.g., seasonal

income variations). experiments demonstrate that the model completes parameter

updates within one hour of policy changes, ensuring risk assessment criteria

remain synchronized with the dynamic environment. Regarding real-time

predictive capability, the risk prediction model achieves single-sample

inference time <50ms. Businesses receive instant risk level and type

assessments after submitting tax data.

Section

4.1

experiments demonstrate the

model maintains stable accuracy >0.8 and AUC >0.8, enabling precise

differentiation between compliant and high-risk filings—laying the foundation

for “correction upon filing.” In terms of error prevention effectiveness, the

“risk-correction” closed-loop integrated with explainable modules (as

demonstrated in

Section 4.2

where Sample 0's risk significantly decreased

after suggested adjustments) enables SMEs to directly rectify high-risk items during

filing. This fundamentally reduces the chain of “filing errors → IRS audit →

penalty losses,” achieving “preemptive prevention” of tax errors.

Additionally,

tax regulators (e.g., IRS) can collaborate with tech companies to embed an

“adaptive-explainable AI” framework into official filing platforms, providing

SMEs with free “real-time risk detection-explanation-correction” tools. API

interfaces connect to policy release platforms to ensure real-time policy

awareness for models. An industry benchmark database regularly updates

compliance feature ranges (e.g., deductions and revenue benchmarks for Industry

7), providing foundational support for model adaptive learning. At the data

level, “federated learning + differential privacy” technology builds an

industry data collaboration network where **“data stays within enterprises

while models are jointly trained”**. SMEs participate in joint optimization of

industry benchmarks and model parameters while retaining local tax data

privacy. This approach addresses the model's “small-sample generalization

deficiency” while mitigating privacy risks associated with centralized data

storage, achieving a balance between “data privacy protection” and “industry

model optimization.” At the enterprise level, addressing SMEs' characteristics

of “limited tax knowledge and insufficient digital tool proficiency,” tax

authorities can collaborate with industry associations to offer free training

on “adaptive AI tax filing tools.” Through case-based instruction (e.g., the

rectification process in Sample 0 from

Section

4.2

), the tools' "risk

identification - explanation - correction“ logic through case studies (e.g.,

the rectification process in Sample 0,

Section

4.2

). This lowers the usage barrier

for SMEs, drives the tool's transition from ”technical feasibility“ to ”actual

usage rate," and ultimately elevates tax compliance standards across the

entire industry.Tax regulatory agencies (such as the IRS) can collaborate with

technology companies to embed this framework into official tax filing

platforms, providing small and medium-sized enterprises with free, real-time,

and explainable risk detection and remediation tools. Simultaneously, by

leveraging federated learning and differential privacy technologies, a secure

and compliant industry data collaboration network can be established. This

enables continuous model optimization and shared governance of industry risks

while safeguarding corporate privacy.

References

- Jin Y, Li Z, Yi P. Review of methods applying on facial alignment. In 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), pp. 553-557. IEEE, 2022.

- Huang J, Qiu Y. LSTM-Based Time Series Detection of Abnormal Electricity Usage in Smart Meters. 2025.

- Qi, R. Enterprise Financial Distress Prediction Based on Machine Learning and SHAP Interpretability Analysis. 2025.

- Yi P, Tang S, Yao J. DDR-Net: Learning multi-stage multi-view stereo with dynamic depth range. arXiv:2103.14275, 2021.

- Reddy C, N. Explainable artificial intelligence (xai) for climate hazard assessment: enhancing predictive accuracy and transparency in drought, flood, and landslide modeling. International Journal on Science and Technology, 16(1), 2025.

- Patra A K, Sahoo L. Explainable light-weight deep learning pipeline for improved drought stress identification. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2024.

- Natarajan G, Elango E, Gnanasekaran R, Soman S. Explainable artificial intelligence for ocean health: applications and challenges. Springer, Cham, 2024.

- Calvo A, Preetam S, Maxime Compastié. Explainable ai for cybersecurity decisions: challenges and opportunities ☆. Explainable AI for Communications and Networking, pp. 145-165, 2025.

- Zakhmi K, Ushmani A, Mohanty M R, Agrawal S, Banduni A, Rao S S K. Evolving zero trust architectures for ai-driven cyber threats in healthcare and other high-risk data environments: a systematic review. Cureus, 2025.

- Han L, Lu W, Dong C. Xai helps in storm surge forecasts: a case study for the southeastern chinese coasts. Journal of Marine Science & Engineering, 13(5), 2025.

- Kapoor A, Chatterjee S. Platform and Model Design for Responsible AI. Packt Publishing, 2023.

- Oresotu O O, Wang P, Wang J, Woo W L. Explainable ai-driven causal analysis and interpretability in environmental sustainability and energy security: a uk case study. Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Information Science and Systems, pp. 151-157, 2024.

- Agrawal A, Kaur K, Kaur H. Explainable ai in biometrics: a novel framework for facial recognition interpretation. 2024 International Conference on Modeling, Simulation & Intelligent Computing (MoSICom), pp. 524-529, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).