1. Introduction

Tax compliance and technological innovation consist of tools to assist Sales Tax inspections in detecting structured fraud and monitoring the movement of goods real-time. As a result of bureaucracies in normal public control structures, tax compliance is the least public control function to be thought of in terms of technological innovation. However, in Brazil, with the advancement of technology and, pressures on tax compliance, tax documents have been digitalised in electronic format, after the implementation of the Public Digital Accounting System (SPED). Several intelligence tools are now available in several automated format to identify possible ways of tax avoidance or tax evasion to reduce fiscal onus or eliminate tax payments.

In the same manner, despite all the technological innovations, there are still some aspects that remain the same over the years, such as the means to monitor goods and commodities on transit. Purporting to be carrying certain goods but the truck is loaded with different goods. Or that the truck is supposed to be on a certain route, but it is plying a different route.

To a government, as a stimulus in implementing a more agile and efficient operational policy serve as incentives to motivate investments in Innovations. Thus, even though organisations may be reluctant to start an innovation project, quasi-outsourcing could be an incentive. In-house development resources enhance the initiatives to kick-start innovation projects (Franca et al, 2024). In Brazil, due to its large territorial extension and low investment in railways, the road modal is the principal means used to transport all products within or outside Brazil. For this reason, monitoring the movement of goods is essential, because just as advanced inspection systems, companies that want to circumvent the system also advance and innovate their ways of finding a loophole in the inspection process to reduce the tax burden. The Sales Tax, otherwise, Tax on the Circulation of Goods and Provision of Interstate and Intermunicipal Transportation and Communication Services (ICMS) is the main tax and represents the largest source of state revenue. Initially, the ICM was levied exclusively on transactions related to the circulation of goods and, later, in 1967, the taxation of transportation and communication services was included; and the 1988 Constitution transferred this competence to the states (Harada, 2022). As the most iconic tax in the Brazilian environment, monitoring is necessary. In fact, when we think about monitoring goods, we immediately think of tax documents such as invoices, bills of lading and manifests. Hence, this study delves into how inspection worked with tax documents on paper and now with the advent of the electronic process. With the advent of SPED and making use of technology, what were the benefits and best practices adopted for effective return to detecting fraud?

This paper makes three significant contributions. Firstly, the study examines a quasi-experiment of development of innovative tools to implement controls aimed at providing a tax inspector with effective artefact to combat tax evasion. Secondly, the study contributes with the filling of the gaps in literature on relationships between tax law and IT control procedures, as there is still no empirical study developed to help understand these phenomena. Thirdly, it helps to mitigate the risks that this represents for the broader society from a tax compliance point of view. In this regard, given this context, the current study questions how are systemic and technologically innovative tools designed and implemented to mitigate structural control risks, to track tax evasion?

After this introduction, the work is structured as follows: the literature review and later the research methodology. Thereafter, data analysis the discussion of the results, and finally, presents the conclusion of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brazilian Sales ICMS Tax

In Brazil, the jurisdiction of each federative entity is established by the Constitution. Thus, the Federal, States, the Central District, and Municipalities may establish taxes, fees, and improvement contributions arising from public works. It is the responsibility of supplementary legislation to establish general rules on tax legislation, especially on taxes specified in the Federal Constitution and their respective taxable events, tax bases, and taxpayers (Brazil, 1988).

In addition to the jurisdiction, the States and the Federal Capital are responsible for imposing taxes on the transfer of property by death and donation of any goods or services (ITCMD); taxes do exist on transactions related to the circulation of goods and on the provision of interstate and intermunicipal transportation and communication services, even if the transactions begin abroad (ICMS – Imposto de Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços) ; and on the ownership of motor vehicles (IPVA) (Brazil, 1988).

Thus, each entity has the authority to establish certain taxes and the details for their implementation. In the case of the ICMS, this was attributed to a complementary law called the Kandir Law (Brazil, 1996). This law established all the situations in which this tax is levied. Among them, we can mention that the tax is levied on transactions related to the circulation of goods, including the provision of food and beverages in bars, and on the provision of interstate and intermunicipal transportation services, by any means, of people, goods, merchandise, or valuables. It is worth remembering that transportation within municipalities (internal transportation within the municipality) is the responsibility of the municipalities through the Tax on Services (ISS) and not of the states (ICMS). Each state can enact its own specific law, if it respects the general rules contained in the Kandir Law (General Law). Another important point is that a specific list of services was assigned to the Municipalities (Brazil, 2003) that, once the generating fact occurs, will be charged only the ISS, in some specific cases the ISS and the ICMS and, in other cases only the ICMS, such as, for example, on the transport service and, only if it is interstate or intermunicipal.

Considering that the states and the Federal District have three taxes to compose their revenue, we can assume that two of them are levied on assets (ITCMD and IPVA) and one is levied on consumption (ICMS). Considering that ICMS is an indirect tax on consumption, it affects the entire production chain and directly impacts the lives of the population, regardless of their social class. Consequently, it is the main source of tax revenue for state entities. Therefore, the need to monitor this tax is crucial to maintain the transparency and credibility of the public entity and to ensure publicity and accountability to the public.

Consequently, for the public to perceive that the public sector is actively working to combat tax evasion and the prosecution of tax violations, it is not only crucial to monitor companies engaged in these transactions involving the purchase and sale of goods, it is also fundamental to also monitor the effectiveness of circulation of these goods within Brazil. Noteworthy, that the debate is on in the national congress to reduce the number of taxes and consequently, the bureaucracies.

2.2. Relationship Between ICMS and VAT (Value-Added Tax)

The main characteristic of ICMS is its non-cumulative nature. This means that the amount to be paid in each transaction related to the circulation of goods or provision of services can be offset against the amount charged in previous transactions (Brasil, 1988).

Besides Brazil, other countries also have taxes like ICMS. For example, the United States has a Sales Tax; countries such as Australia, Canada, Singapore, and India have a Goods and Services Tax (GST); and countries such as China and the European Union use variations of the Value-Added Tax (VAT) (Silva et al, 2022).

Precisely, because of this non-cumulative nature, it is extremely complex to control the entire "Debits/Credits" offsetting process for each taxpayer and correctly calculate the outstanding balance to be paid at each stage of the production chain. Furthermore, there are several exceptions that make this control even more complex, such as tax benefits that include exemptions, reductions in the tax base, and presumed or granted credits that may or may not consume these credits depending on the transaction being carried out and the states between which the transaction occurs, among others. This also includes the timing of tax payment, which must normally be collected before the beginning of transportation but may be postponed if there is an accreditation agreement authorizing its collection a posteriori.

Therefore, to control all events and the correct amounts that each taxpayer is due to pay or receive related to ICMS, it is necessary to use certain tax documents that have all the necessary attributes for calculations, such as invoices, bills of lading, and manifests. These tax documents will be discussed in the SPED section.

2.3. SPED – Public Digital Bookkeeping System

SPED was established in 2007 and can be defined as a tool that unifies the reception, validation, storage, and authentication of books and documents that are part of companies' commercial and tax records, through a single, computerized information flow (Faria et al., 2010). Thus, it has three main objectives: to promote the integration of tax authorities through standardization and information sharing; to streamline and standardize ancillary obligations for taxpayers; and to speed up the identification of tax offenses (Brasil, 2007).

It consists of 5 tax documents and 7 bookkeeping procedures. The documents are: NF-e – Electronic Invoice, CT-e – Electronic Bill of Lading, MDF-e – Electronic Manifest of Tax Documents, NFS-e – Electronic Service Invoice, and NFC-e – Electronic Consumer Invoice. The 7 bookkeeping procedures are as follows: Digital Accounting Bookkeeping (ECD), Fiscal Accounting Bookkeeping (ECF), Digital Tax Bookkeeping (EFD), Digital Tax Bookkeeping – Contribution (EFD-Contribution), Digital Bookkeeping of Withholdings Tax, and other tax information (EFD-Reinf), Financial Bookkeeping (E-Financeira), and Digital Bookkeeping of Tax, Social Security, and Labor Obligations (E-Social).

For controlling and monitoring ICMS taxpayers, the three most important documents are: NF-e, as the invoice stores all the data on the merchandise that was purchased (name of the product according to the Common Nomenclature of Mercosur (NCM), quantity, unit, value, discounts), which taxpayer made the purchase and sale, how the delivery of this merchandise will be made, what type of operation was performed, etc.; CT-e, this document is issued when the transportation of the merchandise is carried out by a third company other than the buyer and seller and this transportation service will be paid in addition to the sale value, including the appropriate taxes. This document contains all the data regarding the freight to be carried out; MDF-e this document is the most important for controlling the transportation of goods, as this document will contain the license plate of the truck that will carry out the transportation, will indicate the cities where all loading and unloading will be carried out, in addition to providing which states this transportation will pass through on the way between loading and unloading, sometimes this detailed route is not informed.

These three electronic documents are stored in the centralized tax database located at the Rio Grande do Sul State Treasury Department (SEFAZ-RS). This database provides services for the other 26 states of the Federation to access information on the tax documents of which each state is a member. For example, SEFAZ-GO pertaining to the State of Goias must transmit all tax documents issued by it, and SEFAZ-GO must receive all tax documents issued to it or of which it is a member. For example, in the case of the MDF-e, even if Goiás is neither the origin nor the destination of that interstate transportation service, but if Goiás is on the route, then Goiás must receive the tax documents related to that transportation.

But why is this important? Because invoices are often issued by other states and should be going to other states, and Goiás would only be on the truck's route. However, in reality, the product never came from outside the state. In fact, the invoice states it was produced outside, but the truck was loaded within the state of Goiás itself and will continue enroute its destination. This discrepancy between the tax document and the actual shipment occurs precisely so that the company can benefit from potential prior credits or tax benefits. If the invoice had been issued with the correct origin in Goiás, it would not have had this credit to reduce its debt and would thus have had to pay a higher ICMS tax.

How can we determine whether the tax document truly matches the actual route taken by the goods? In other words, how can we know if the vehicle used to transport the goods performed as planned? In the past, when tax documents existed only on paper, tax offices served this function.

2.4. Tax Offices

Initially, before the advent of electronic documents and SPED, all tax documents existed only in physical form, meaning there was no electronic format. To print invoices, only printers authorized by the tax authorities could print and generate invoice booklets for the issuing taxpayer. After an invoice booklet was printed by an authorized printer, the taxpayer had to go to the tax office to obtain the invoice booklet authorized for use. There were two types of invoices, Model 1; one already had a printed numbering, and the other did not have the invoice number field printed. The taxpayer would use an electronic system to generate and print this numbering (at the time, dot matrix printers with continuous forms were used). In this case, the taxpayer controlled the sequential numbering.

In both cases, release for use occurred only after release by the tax authorities, who in turn kept in their possession a page from the notepad so they could use it to validate whether the invoices issued by the taxpayer were actually from the booklet that was validated and released for use, as without this comparison, they could use other invoices generated by unauthorized printers in an inappropriate manner.

After issuing multiple copies of the invoice, the truck continued its way. As soon as it passed a tax office, usually at the state's entrance, the inspector would request the invoice and stamp it. Upon leaving the state, the credit generated by the invoice would only be granted if it bore the state's entry stamp. One copy of the invoice was retained at the tax office, which would then collate multiple invoices over a period of one or more days, take it to the police station, and then digitize all the invoices. This data was stored in the mainframe system for later use during an audit of the establishment's entry invoices, comparing them with the invoices collected by the tax authorities during the transportation of the goods. All this work required a significant amount of the auditor's time, and it was unfeasible to control the entire invoice issuance process by stopping truck after truck on the highway, significantly delaying the arrival of the goods at their destination.

With the implementation of electronic documents, the entire process has become much more streamlined and efficient. The Rio Grande do Sul State Finance Department (SEFAZ-RS) created the portal for the National State Operator (SVRS), known as the National State Operator (ONE). ONE is a system responsible for integrating the electronic tax documents of tax authorities with the various vehicle identification technologies on Brazilian highways. It generates events for traffic records on tax documents based on the truck's license plate and location, detected by a monitoring device, aiding in traffic enforcement and combating tax evasion.

This centralized system verifies the status of tax documents and makes the information available to all involved. It also reports events per tax document, such as when a document was authorized, terminated, or cancelled, as well as events reporting vehicle passages through monitored antennas. This means the equipment sends the information to the central office.

Soon, with the advancement of SPED and tax documents, and also with the use of the ONE system, the stations in Goiás gradually lost their function and were closed, as control became systemic and no longer required manual processes performed by auditors, such as stamping. However, even today, in Goiás, in the city of Itumbiara, we have one of the largest ICMS inspection stations, which operates differently, using computerized systems accessed via intranet or the web.

However, it is important to remember that the ONE system is a centralized database that provides generic services to all tax authorities in Brazil's 27 states. Therefore, its main function is to serve as a large repository and provide reliable information centrally. Services are provided, but there is no ready-made, specific application for auditors to quickly use for decision-making. Its focus is to provide centralized data and services for consumption by each state. Each state must adapt the services to the specific needs of its region and the auditing approach adopted.

With most tax offices closed and tax documents now in electronic format, how can we ensure effective oversight? Tax audits must leverage technological advances to ensure alignment, mitigate risks, and prevent tax misappropriation. Furthermore, ICMS is a tax, and therefore compulsory, and according to Article 16 of the National Tax Code (Brazil, 1966), as a tax, it is independent of any specific state activity related to the taxpayer. Therefore, it will be necessary to adopt the legitimacy theory and systemic controls to ensure its correct collection and oversight.

2.5. Legitimacy Theory and System Controls

Policies implemented under the ICMS law presuppose mandatory compliance, especially when using systemic tools that tend to legitimize awareness, adherence and homogeneous application by users. In line with the legitimacy theory that posits mandate. Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) observe that an organization's legitimacy depends on its value system aligning with societal norms and values. In the same vein, Dias Filho (2007), legitimation theory considers a "contract" between organizations and society that shares expectations about how they should act, whether explicit or implicit. However, since compliance with these policies involves significant tax payments and, consequently, reduced corporate profits, these companies attempt to eliminate or reduce the total payment of this tax, either legally (tax avoidance) through loopholes in the law, or illegally (evasion), for example, by simulating one transaction through tax documents when the transaction was another.

At this point, the use of systemic controls is essential, as they can help automatically control operations, streamlining the process, improving reliability and transparency, and enabling accountability. However, the combined use of Legitimation Theory and Systemic Controls does not completely reduce fraud, as it requires continuous monitoring, adjustments to changes in behaviour and legislation itself. Ultimately, the entire process must be closely monitored and adjusted to meet inherent changes.

However, the use of technology in tax oversight is essential to mitigate the risks that technological change has brought to the fiscal auditing of goods transit. Therefore, although systemic controls do not 100% guarantee that fraud has not occurred, it is safe to say that without them, any oversight operation would be unfeasible. It is important to keep the process constantly updated through continuous improvement to prevent it from becoming obsolete and quickly inefficient.

3. Methodology

This is a case study of a quasi-experiment of implementation of tax application. Thus, to proffer answer to our research question, a qualitative paradigm (Imoniana et al 2022) was followed by an interpretative perspective. It uses participant observation (Yin, 2014). A case study is an empirical methodology that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context. When the boundaries between the phenomena are not clear and in which multiple sources of evidence are used (Yin, 1989). It aims to present in detail how the data construction of the case, development, and implementation of online monitoring tools to assist the auditor in their ICMS inspection process in the transit of goods within the state of Goiás. As observed by Stake (1995) investigating singular cases has the intention to contribute theoretically and precisely due to its peculiarities. This process took place in the second half of 2023, but the first version of the application went into production in April of that same year. Some practical cases will be presented elucidating how this tool helped to mitigate risks of ICMS misappropriation, however, the real data will be replaced by fictitious names due to the confidentiality of the information.

Although there are 6 (six) possible sources to capture evidence (Yin, 2014), the chosen source was participant observation. This type of source has positive points, such as reality, context, the possibility of acting actively and analysing behaviours beyond interpersonal motives. However, there are negative points, the main one being bias resulting from the possible manipulation of events by the participant observer. However, as in this case the participant is a tax auditor responsible for providing a systemic solution that helps auditors quickly identify any abnormality in the process and, because he holds the effective public office of a tax auditor, the profession itself makes him impartial by nature, greatly reducing this setback.

The process of analysing the available data and defining the scope to be monitored, as well as the entire technological design, will be presented in technical detail, but without presenting some confidential points of the tax authorities themselves for strategic reasons. However, as the main objective is to help other tax authorities to learn about best practices and start their process with an applied case study, the absence of key points will not affect the objective of this work in presenting the real experience of implementing the integrated solution to assist the work of tax auditors in the process, in addition to reinforcing the ICMS inspection process.

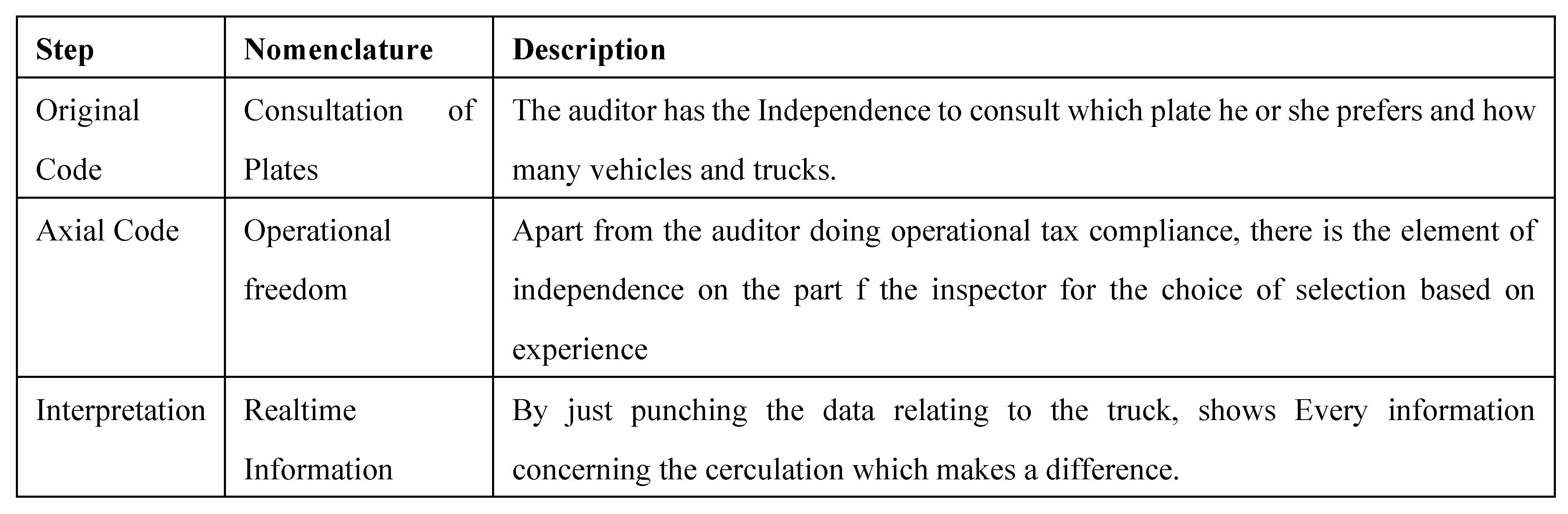

The data interpretative coding follows Charmaz (2006), which is the coding process in qualitative research. This coding process was crucial for the analysis and interpretation of the results helping to support the context-pound emerging categories. The qualitative software of MAXQDA also facilitated data organisation, coding and operationalisation of the interpretative procedures.

3.1. Data Construction

The key to the success of any technological solution is to fully understand the needs of its users/clients, this is a crucial point. Initially, a meeting was held at the Department of Economy in Goiânia with the participation of 5 (five) traffic auditors with over 20 years of experience in ICMS inspection, each from a different location (Regional Inspection Office - DRF), to have a comprehensive view rather than a specific and punctual view of a city or region.

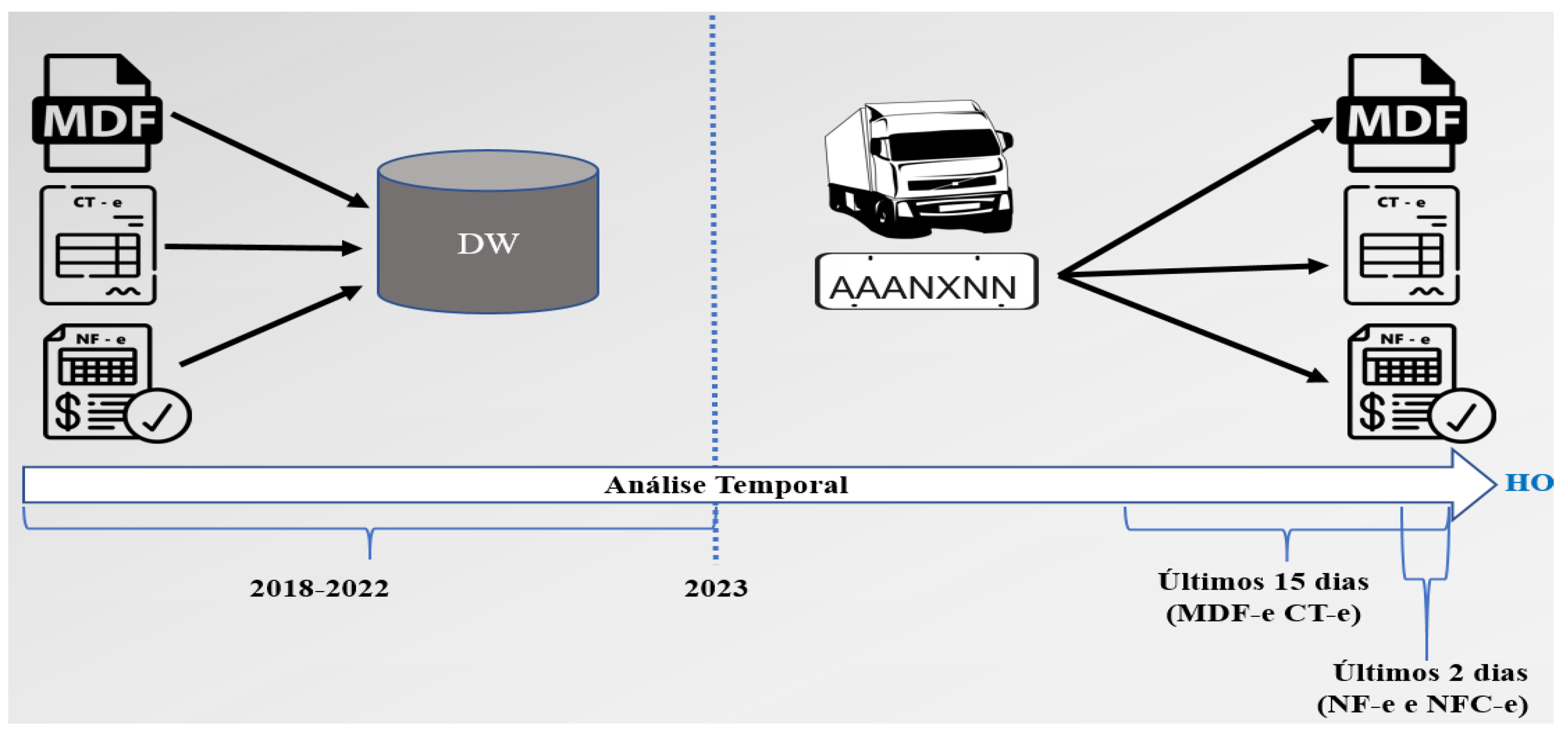

It is important to emphasize that traffic inspection work has a different profile from auditing specific companies. Inspection of certain companies involves analysing data from the last 5 years, that is, the investigation takes place by looking at the company's past behaviour (triggering event that has already occurred). Therefore, the database to be used does not need to contain real-time (online) data. It is possible to work with the Data warehouse (DW), otherwise, Data Lake as categorised by Franca et al (2024) that has data updated up to the previous day (D-1).

Traffic inspections focus on the present moment, the state of the art and how the company is behaving. Therefore, it is important for inspections to know when the vehicle is actually circulating with the merchandise and to validate whether there are valid (active) tax documents that prove that movement for tax purposes. In this case, the scope used in the search for tax documents is much smaller and depends on the study of each reality. In the case of Goiás, it was decided to consult the last 15 days of MDF-e and CT-e, in addition to 2 days for invoices (NF-e and NFC-e). This difference in scope and data analysed is fundamental and needs to be understood before any analysis of technological tools; it is a paradigm shift (

Figure 1).

The implementation group consist of the representative of the stakeholders. During the first meeting, each auditor presented their way of working in traffic, their difficulties, their expectations, their demands, in short, everyone was able to present and bring up the key points of each region. However, in this conversation it became very clear that the way of working, that is, the process used for analysis and citation, was not standardized, that is, each regional police station worked in a different way. An important point to be considered was how a single computerized system could meet the different demands. At the end of the meeting, it was agreed to prepare a report with all the needs to prioritize and equalize the demands.

After this first meeting in which it was possible to “listen” to the interested parties and understand the way of working as a spectator, the next step was taken. Participating “in locco” in the traffic inspection process under real field work conditions, but with the perspective of a tax auditor experienced in the IT area (over 20 years in the private sector), but inexperienced in traffic inspection.

During this experience, it was possible to monitor the real situation and understand how the auditors used the existing technology: they did not use the available mobile phone application, because the usability and quality of the information (tickets, tax documents, alerts) were not consistent with their needs. The problem with the usability of the application occurred according to the time of day, because in the afternoon, when the sun began to set, with the reduction of natural light and few streetlights on the road, it was difficult to view the data on the mobile phone screen.

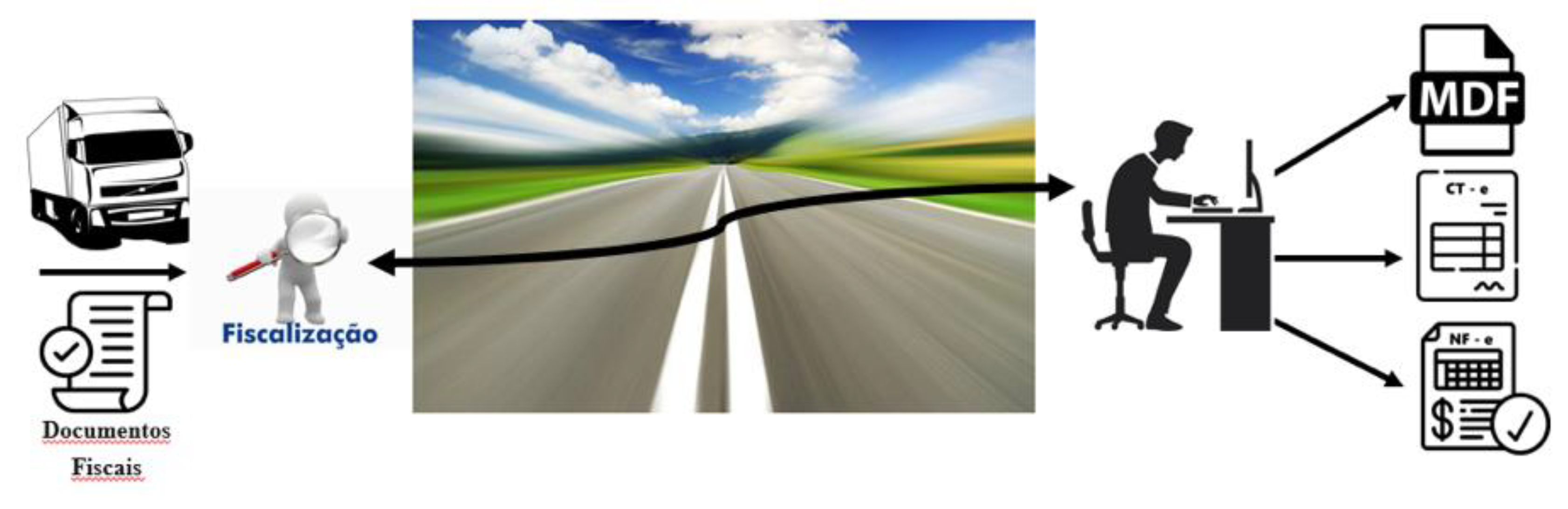

Another point that was very physically exhausting for the auditor was that several times during the day, he was forced to leave the road, enter the Federal Highway Police (PRF) inspection station, access his notebook and use the Secretariat's internal system or the ONE system (

Figure 2).

At times, additional information was needed, so they asked the PRF team for help to access their system to be able to view the route the vehicle had taken in the last few days and compare it with the tax documentation presented, because at certain points there was no equipment available that could have this information.

Another issue identified was the frequent need to access the Secretariat's large internal system to check whether the taxpayer had a valid Accreditation Term that authorized non-payment of the ICMS in advance, and once again, the auditor was forced to cross the road to access his notebook.

After this practical experience, it was possible to understand that, regardless of the way of working, what the traffic auditor needed was a tool on his cell phone (mobile) that was timely, simple and legible to reduce the need to access the desktop version and that helped him make the decision to approach the transport vehicle quickly and efficiently in case of possible doubt about some tax offense. But the fundamental point was to have reliable information available in this application, starting with the passage of the vehicles through the OCR equipment, then the result of the comparison of the license plate with tax documents until the issuance of alerts of probable tax offense; in short, the process always begins with the correct data for decision-making.

3.2. Solution Design Analysis and Implementation

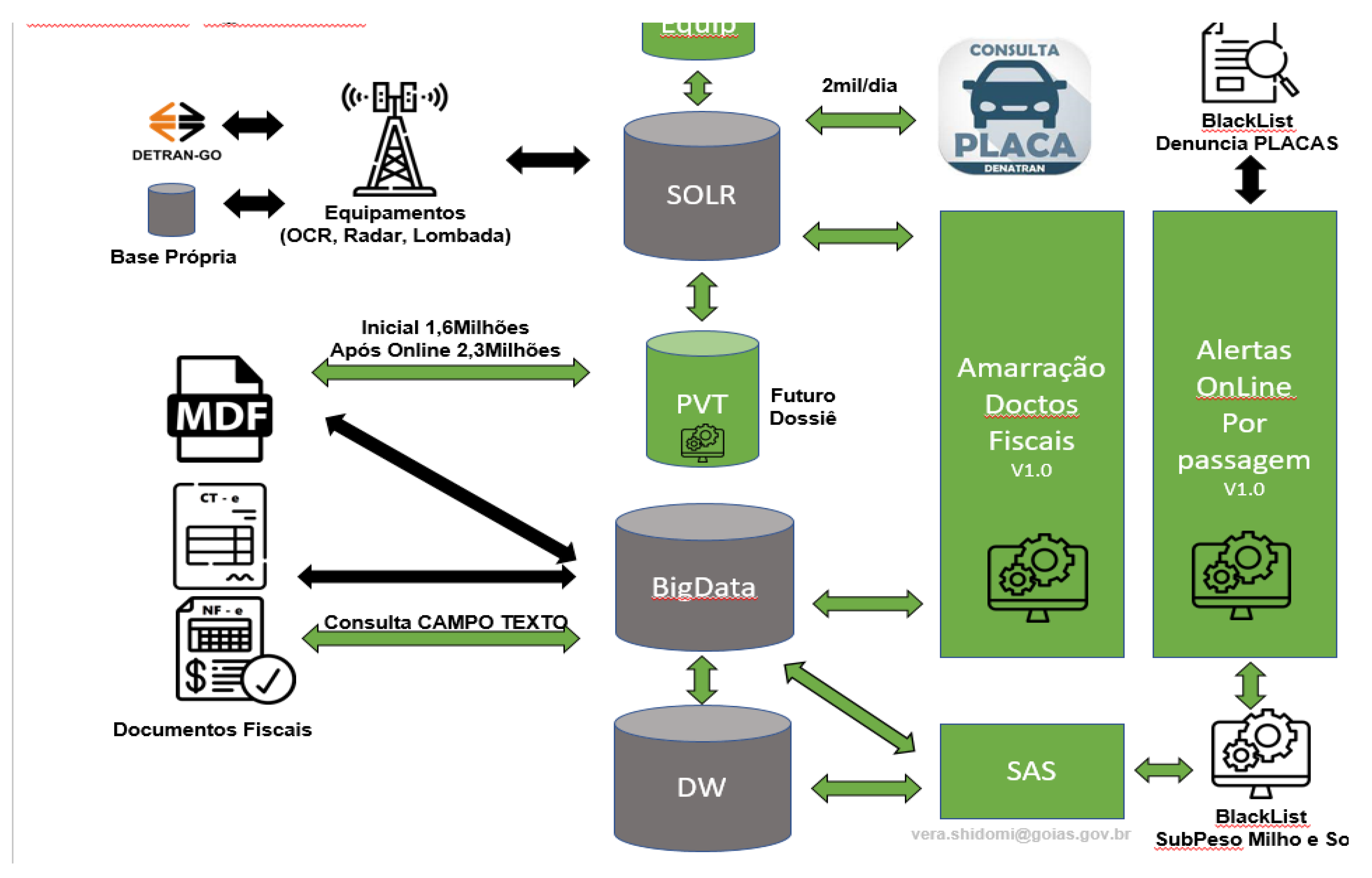

After the requirements gathering stage in practice, it was necessary to understand where and what the problems or areas for improvement in the process and internal controls were. These adjustments would need to be made so that the data would reach the center correctly and in a timely manner and thus be able to cross-reference with the tax data and present it effectively. As per

Figure 3 the complete process has been divided into parts to be analyzed: capturing vehicle tickets; data quality process; association with tax documents; applications made available for use by auditors. Each step will be described as follows:

3.2.1. Capture of Truck Passages and Refinement of Data

The first stage of traffic monitoring begins with the capture of the truck's passage using some OCR (Optical Character Recognition) equipment. It is important to remember that the Ministry of Finance itself invested in its own equipment, as this would increase the capacity to customize it according to its needs and adapt to local particularities, in addition to the reliability and availability of the information.

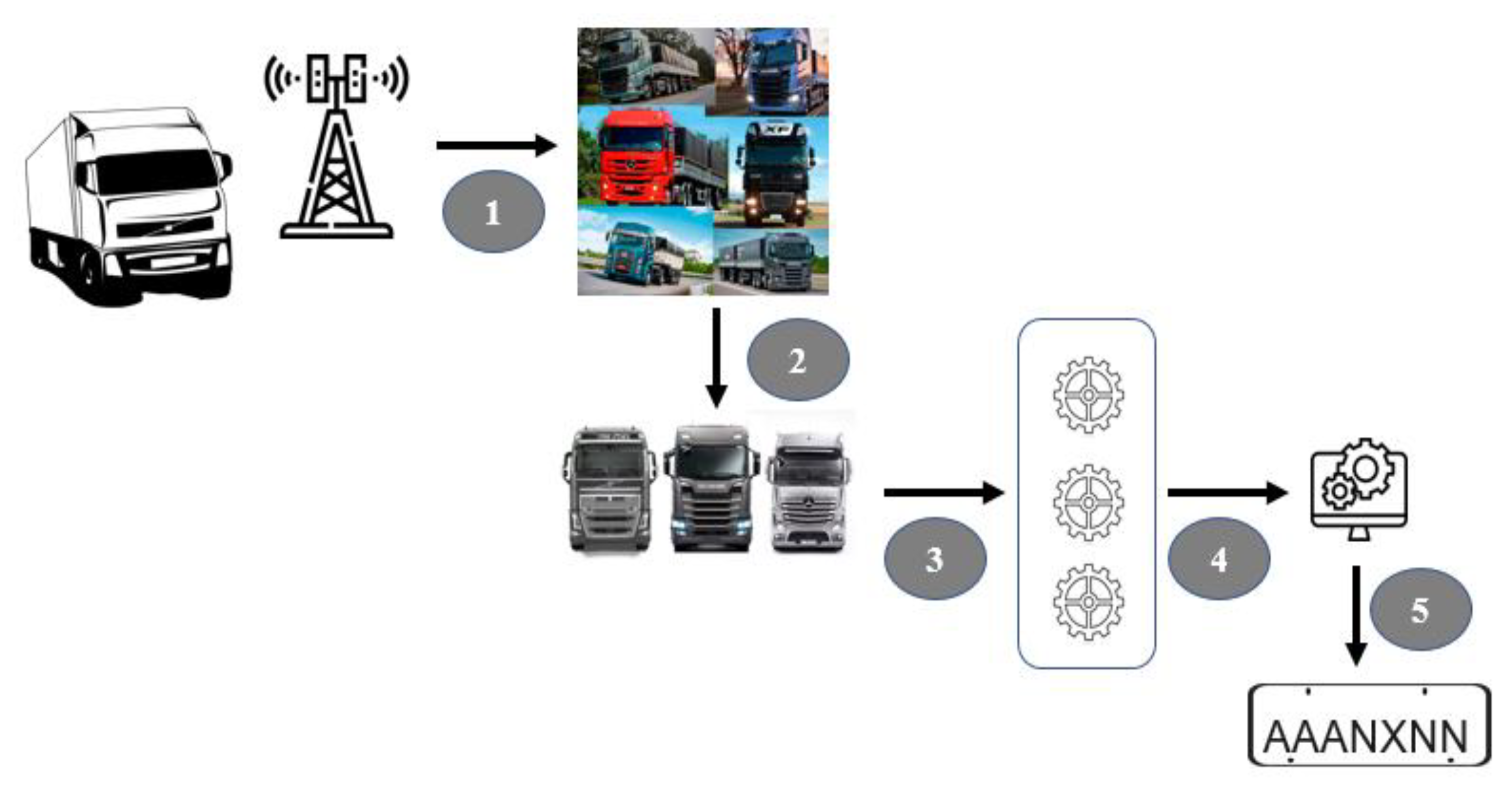

The internal process of the equipment is shown in

Figure 4. Each time a truck passes, the OCR equipment automatically records several photos (Step 1); then, through algorithms using machine learning, the three best photos are chosen (Step 2); then, for each photo, the photo is converted into license plate data using artificial intelligence (Step 3); finally, we have 3 records with the license plates and, through a simple algorithm, the best license plate is chosen (Step 4) and the Truck's passage is stored with the final license plate. During the testing of the experiment, de facto when the process was implemented in production, a problem was detected in Step 2: in some cases, the best photo was being discarded. An adjustment was requested, and the process began to choose the best photos more assertively. In addition to this improvement, there was initially a single algorithm in Step 3 that was not efficient. Therefore, by implementing three algorithms and creating a selection process (best of 3), it was possible to increase the accuracy of the process by more than 50%.

3.2.2. Data Quality

Any company's greatest asset is its data, which can be transformed into useful information. Therefore, the crucial point begins with the data itself. When it comes to using license plate data to confirm whether a Truck is in service, it's crucial to ensure the accuracy of this detection process. Several factors contribute to incorrect readings, such as worn, dirty, or bent license plates, and the color of the background and letters, which can vary from red to white or grey, making effective license plate recognition difficult. Some letters are confused with numbers, such as the letter "O" and the number "0" (zero). It was necessary to implement a data cleansing and correction process, as the digit position determines whether the value should be alphanumeric or numeric. Through programming, it was possible to correct the letter "O" for the number "0" (zero) and vice versa, thus improving the accuracy of the process.

After obtaining the correct license plate value, another problem remained: not all vehicles are eligible for tax inspection. The scope of the inspection work is to find goods transport vehicles and verify whether they have the correct tax documentation or some accreditation agreement that waives advance payment. The existing process, ineffective, only considered data from vehicles in the state of Goiás to determine whether the registration was for a truck or not.

Considering that the location with the highest truck traffic in Goiás is located on the border between two states (Goiás and Minas Gerais), in the city of Itumbiara, it can be inferred that more than 50% of the vehicles do not originate from Goiás, but rather from other states. And that is exactly what happened: the existing process could only classify less than 10% of the actual number of trucks traveling in that location as "trucks." It was therefore, determined that this truck identification process was ineffective and needed to be modified. Initially, the possibility of accessing the national vehicle database was questioned, but there was a monthly limit on accesses, and this limit would not be sufficient for the number of vehicles traveling on Goiás highways.

As per department's suggestion, it was decided to create a database of license plates used by the department's own transportation vehicles. These plates were obtained from all Electronic Manifests (MDF-e) from Goiás contained in the DW environment. This resulted in what was called the PVT (Transport Vehicle License Plate Database), which includes not only trucks, but any vehicle considered a transportation vehicle when issuing the MDF-e tax document). After analysing the data, it was necessary to clean and correct the data registered in the MDF-e. Considering the possible formats for filling in the license plate field, whether in the old format (AAA 9999) or the Mercosur format (AAA 9A99), several registration issues were detected. Therefore, a corrective process was implemented that considered the letter "O" as the number 0 (zero) and vice versa, depending on the position. This corrective process was implemented in batch mode during the initial data load, but it was also implemented online when new records were added to the PVT database, without affecting the data in the manifest itself, which was stored as originally entered.

Once the PVT database was created, the initial load, including front-wheel drive and rear-trailer license plates, generated approximately 1.6 million distinct license plates. A few weeks after the online process was released, it already included approximately 2.3 million transportation vehicle license plates. Thus, when a vehicle was detected by the equipment and its license plate was read, the process checked whether the equipment itself identified it as a transportation vehicle (some equipment uses artificial intelligence to identify it as a truck or not). If it was already marked, the license plate would be entered into the PVT database. Subsequently, a batch process would query the national database to verify whether it was actually a transportation vehicle, correct the marking, and enrich it with more information about the vehicle and its owner. Otherwise, if the passage was not marked, the PVT database would check whether the license plate already existed; if it did, it would be considered a transportation vehicle.

Why is it important to separate a transport vehicle from a passenger vehicle? This is important for tax audits, as only transport vehicles will be validated to find tax documents authorizing the transportation of goods. Imagine if this separation didn't exist, then all passenger vehicles would go through the tax document identification process, burdening the system and generating unnecessary processing costs. Therefore, with the creation of the PVT database, only the correct vehicles are identified and enter the tax document validation process.

Another significant improvement implemented was the process of standardizing equipment data. Because they were from different suppliers, the registration data (road location, direction, address) of the equipment was inconsistent, making it difficult to understand in the application.

3.2.3. Relationships Between the Fiscal Documents

The tax documentation validation process was implemented online. Each time a vehicle passes through an OCR device, the license plate is read and identified as a transport vehicle. If so, the process begins in parallel to find the license plates in the tax documents: Manifests (MDF-e), Waybills of Lading (CT-e), and Electronic Invoices (NF-e). The search universe was defined as the last 15 days of MDF-e and CT-e and the last two days (48 hours) of invoices. Once a tax document is found, it is also analysed whether it was "open" at the time of the inspection, as a tax document status identifies whether a specific tax document was valid at the time of inspection. It is possible to find more than one tax document per inspection, and all are linked to the inspection. This process is called "Tax Document Linking."

An important technical point to be highlighted is that the work was initially carried out in the DW (Data Warehouse) environment. However, due to critical issues and the need for timely information, all transit systems were modified to access Big Data (a database updated in real time and with "raw" data, meaning the data is stored in its original format. Since these are electronic documents, they are in "xml" format). This change also allowed searches for the license plate field to be performed in the descriptive (text) fields of the tax document, improving the efficiency of tax document identification.

3.2.4. Application and Developed Tools

After capturing ticket data, obtaining high-quality license plate information, and associating it with the relevant tax documents, it was possible to transform the simple data into useful information for the tax auditor. With this accurate information, it was now possible to provide practical features in the mobile app. Two features were developed: Online Alert and License Plate Query, as well as a tool for checking accreditation terms, built outside the app platform using only a browser to reduce development time and bring immediate agility to the auditor's work.

3.2.4.1. Online Alerts

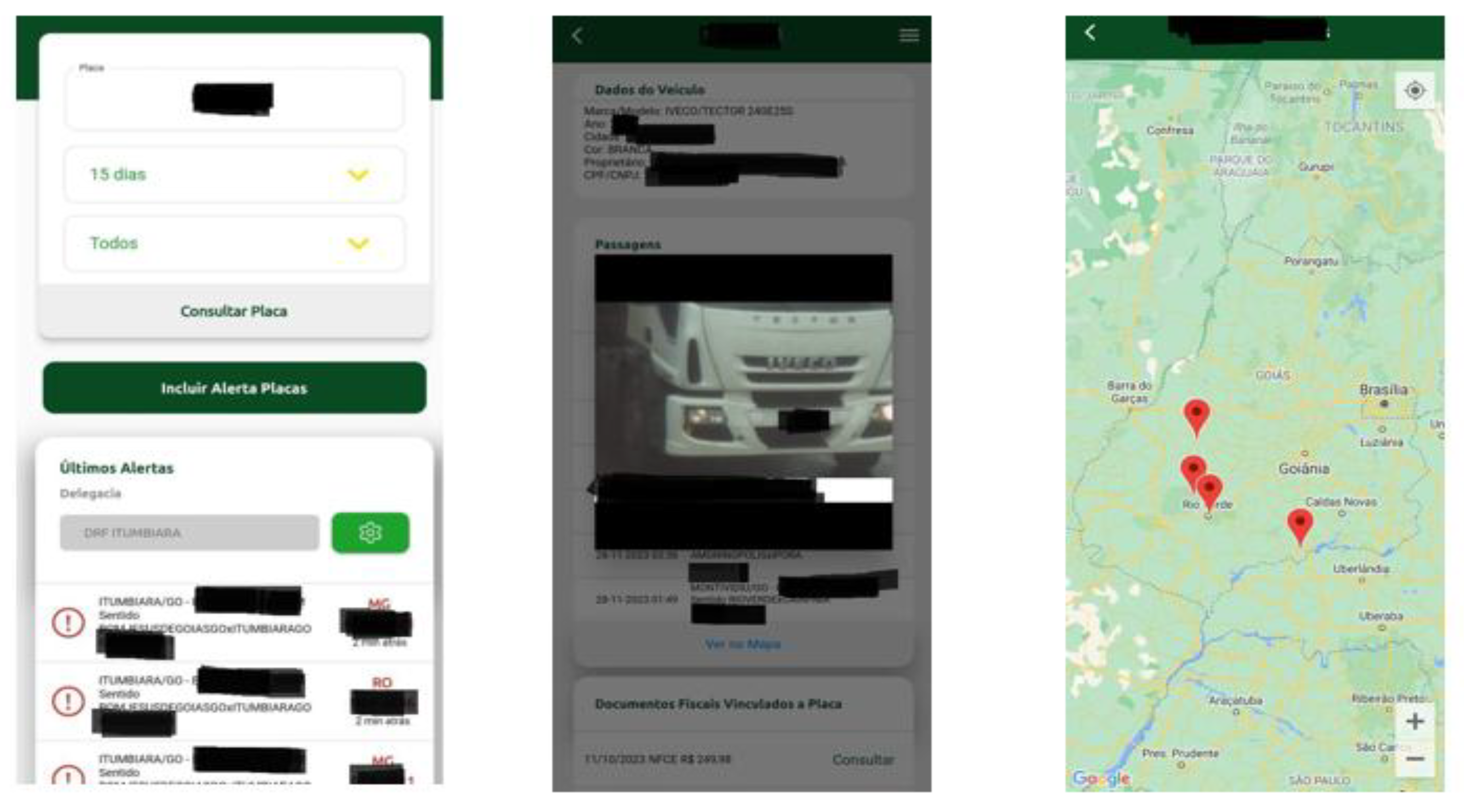

Now that the tickets are correctly associated with the tax documents, it's possible to generate some types of automatic alerts ("Online Alerts by Ticket"). This began with the registration of license plate reports, where the experienced auditor registers suspicious license plates. When the ticket is passed and cross-referenced with this list, the system alerts the auditors in the app, indicating where the vehicle passed so they can conduct a stoppage. Another alert process was developed in the SAS tool to identify vehicles traveling with a weight lower than their historical capacity (Underweight), specifically for products such as corn and soybeans. The last process implemented to date was the tax documentation validation process. If the process fails to find any tax documents (MDF-e, CT-e, NF-e, NFC-e), an alert is generated (

Figure 5) to notify the auditor of vehicles traveling in this situation, and in this case, the auditor will determine the best location for stop and inspection.

However, the use of this service depends greatly on the way each auditor works, as they can choose to respond to alerts or continue in the traditional way, carrying out operations in certain locations in Goiás. This is why the most used service in the application was the license plate consultation service.

Figure 5.

SEFAZ/GO application - Alerts and Consultation of Truck Plate number.

Figure 5.

SEFAZ/GO application - Alerts and Consultation of Truck Plate number.

3.2.4.2. Consultation of Truck Plate

The auditor needs to obtain information about vehicles traveling on the highways, and to do so, they need to know them. Therefore, the application that performs license plate lookup was improved to provide the auditor with information for their analysis.

After adjusting the entire process, from capturing tickets, interpreting them, filtering important tickets, identifying tax documents, and generating alerts, the application became useful for traffic control auditors. Now, in less than a minute, from the moment the vehicle passes through an OCR device until the entire process is completed, the result is displayed in the application, enabling simplified decision-making, as shown in

Figure 5.

This result covers the entire route taken over the last 15 days, detailing the locations travelled, the exact time, and all tax documents related to the Truck. With this information, the auditor has sufficient history to investigate and identify possible cases of incompatibility between the tax document and the actual route taken.

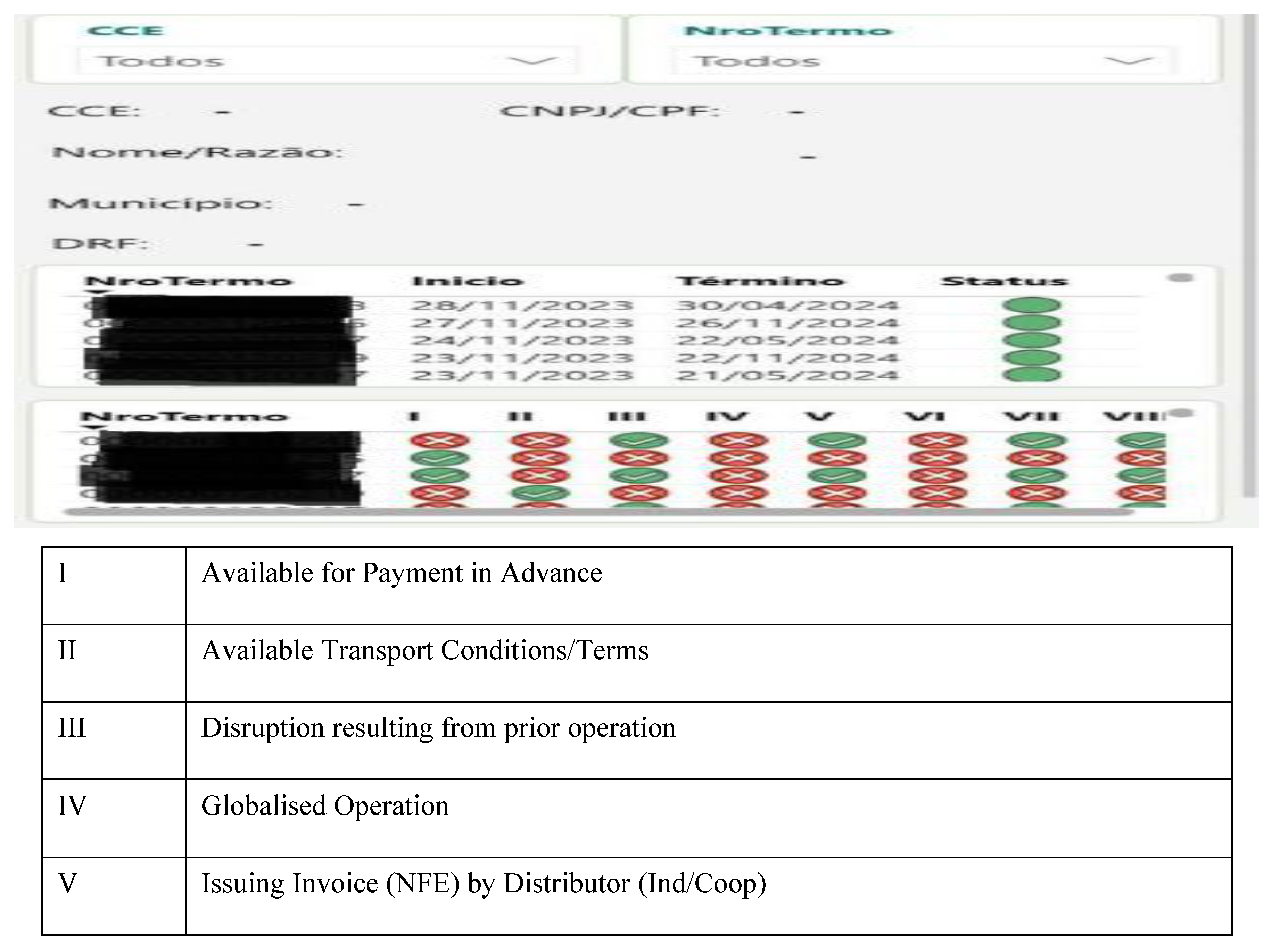

3.2.4.3. Consult Term of Credentials

The latest implementation made available to the auditor was the creation of Power BI dashboards to display the Accreditation Terms data directly from the cell phone using a custom browser to display the data in the device's field of view (

Figure 6). Previously, this information could only be obtained using the auditor's desktop in a physical structure or somewhere where it was possible to open the laptop, access the secretariat's network, and access the mainframe system. In other words, by implementing this tool also on the auditor's cell phone, it was possible to make the process agile, practical, and less costly in terms of time spent on this procedure. The decision to include it directly in the existing application was not made possible because the time required to implement this functionality was analysed versus the immediate need for it. However, this does not mean that this function will not be incorporated into the application within a few months.

4. Results and Discussion

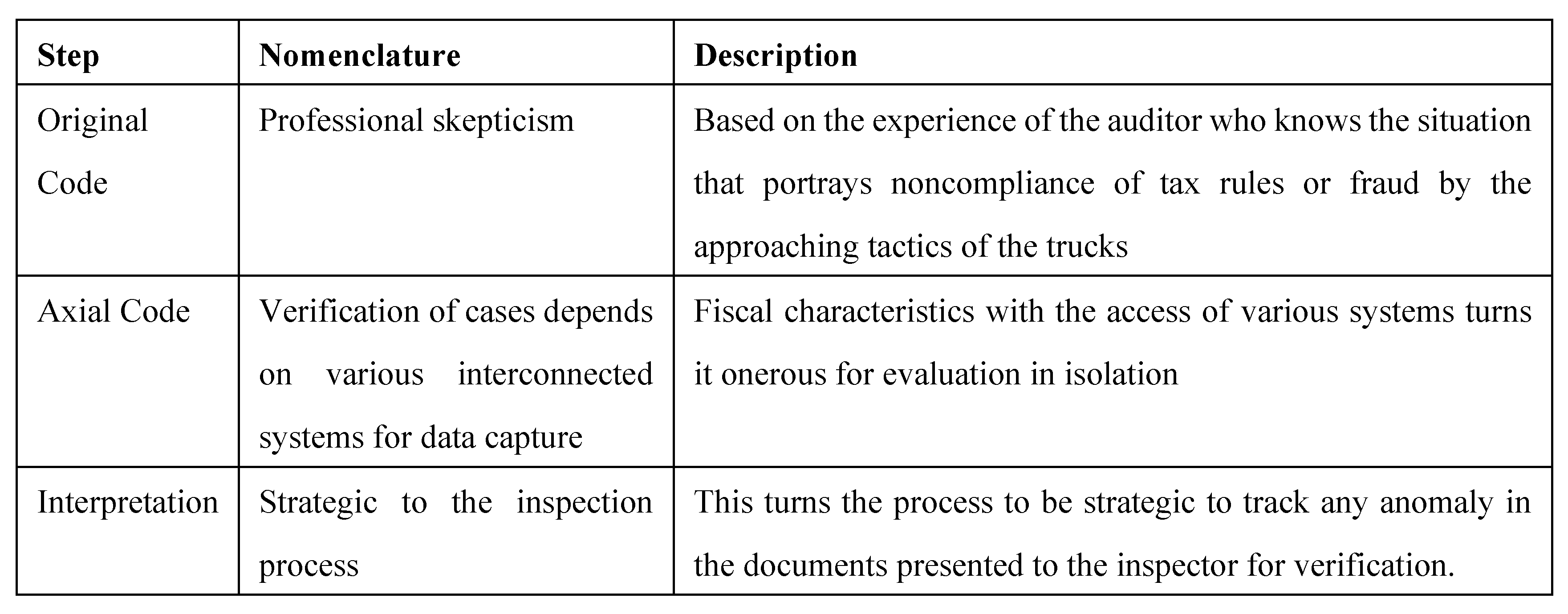

The tax inspection process carried out by the traffic auditor in the state of Goiás until April 2023 presented several control risks. Due to the lack of systemic and technological tools, it depended solely on the experience of each auditor. As observed in

Figure 7, one notes the process of evidencing the mitigation of risks.

Experienced auditors, with years of experience on the road, already possessed the scepticism to suspect situations that lead to tax fraud. Thus, when approaching vehicles, analysing their physical characteristics and documents, they already knew how to use the available desktop systems for research and analysis. Even so, it was often necessary to obtain additional information, which made the process more costly and inefficient, as it depended on other personnel. Due to strategic confidentiality, it will not be possible to present all the details in this study, but we will describe some examples to highlight how the available applications aided the inspection work by introducing new controls that helped mitigate the risks of these controls and tax fraud.

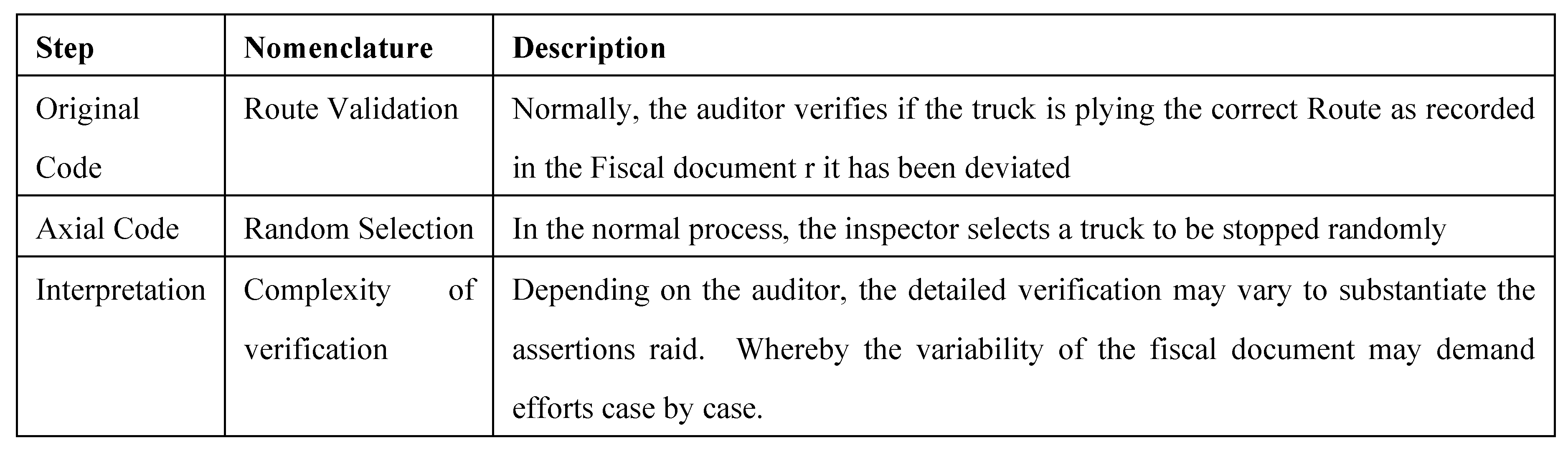

Initially, traffic inspectors chose locations to conduct their operations, and at that location, they would stop vehicles. At that point, they would request tax documents and begin validation. They would ask drivers where they loaded the goods, which route they plied, and if the inspector found anything unusual, they would conduct a more in-depth investigation using the department's systems. However, if they "found" everything to be in order, they would release the vehicle; in other words, the number of validations depended heavily on each inspector. Noteworthy, to consider several points in this process: first, the selection of the vehicle to be inspected was as per

Figure 8.

The degree of complexity of the tax document validation process varied from case to case; evidence regarding the locations the truck actually travelled depended heavily on PRF equipment and systems or on events recorded in the ONE system.

After implementing the mobile app on the auditor's cell phone, the process began to change. As in

Figure 9

Each auditor was given the freedom to choose how they would use the app, but all were trained to understand the tool's full functionality, from the theoretical part to practical operation on the roads using the app. Auditors began using the license plate lookup service. During the operation, they simply entered the license plate number and immediately knew where the vehicle had been traveling. The app displayed which roads it had been on, including a visual map, and also indicated whether any valid tax documents were available at the time the vehicle was driven. Thus, before the driver stopped the vehicle, the inspector already had sufficient data to detect any irregularities or possible fraud. When questioning the driver about the information, they could immediately verify whether the driver was telling the truth, thus reducing the risk of fraud.

Noteworthy to explain that, for ICMS inspections, the actual route a vehicle travelled makes all the difference, as the tax isn't levied on domestic routes, only interstate or intercity routes. Another recurring issue is the reuse of valid tax documents. Drivers often make numerous trips using the same documentation. However, if they do this now, the app will have the entire trip history, as well as alerts in case of trips without a valid tax document. Furthermore, the auditor, with the information at their disposal, can easily detect inconsistencies. For example, a driver may present a tax document indicating that they departed from state X and are going to state Y, but when analysing the tickets in the app, it's possible to see that they never came from X and are traveling in a completely off-route direction solely to reduce the tax burden. Furthermore, it's also possible to consider the time factor, as the trip history allows us to calculate whether the distance travelled matches the estimated time and the route that should have been taken according to the tax document (MDF-e).

One feature that has been widely used is the lists of suspicious license plates that auditors themselves register. In this case, the system acts proactively, generating alerts and notifying auditors when registered vehicles pass through an antenna. This allows for immediate inspection and enforcement. Thus

Figure 10 describes the process.

Note that properly functioning OCR equipment located throughout the state serves as a control system to assist inspectors, functioning as virtual tax offices serving the tax authorities and helping to reduce cases of potential irregularities or tax fraud. Another feature that has expedited inspectors' work is the availability of the Accreditation Form on the mobile app, allowing them to perform the search themselves and verify whether the taxpayer could indeed be driving without paying ICMS in advance, right on the road without having to go to an office, open their laptop, log into the mainframe system, and finally verify this information.

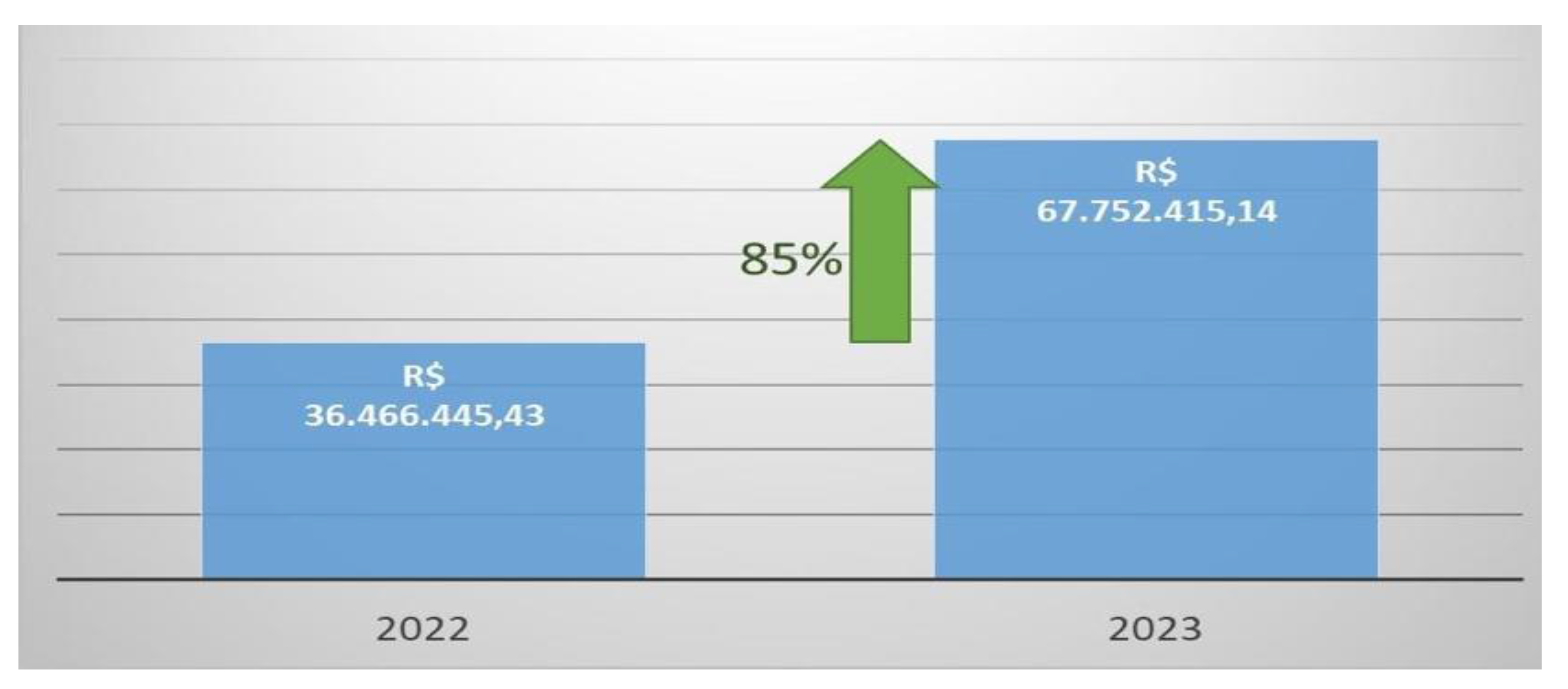

The features implemented in the mobile app were chosen based on development time, impact, and return on investment. Only high-impact, fast-return features were implemented initially. Therefore, within the week the app was released, it already demonstrated significant results for traffic enforcement, and since then, the effectiveness of the enforcement process and the consequent increase in revenue have been notable (

Figure 11).

An important question: is this increase solely due to the app's availability, or were there other factors contributing to this increase? An important point to consider is that there had not been a new public exam for new tax auditors in the state of Goiás for 18 years, and consequently, the number of traffic auditors was very small. In 2018, a new exam appointed approximately 10 new auditors by 2023, increasing the number of auditors specifically for traffic by 50%. These new auditors lacked experience in inspections, so without the tool that was made available, would they have been able, without prior experience, to account for the 85% increase in the number of traffic violation notices? Another important point is that the use of the mobile app depends heavily on the user's ability. Perhaps we can consider that both factors combined were responsible for this success. In other words, the tool, coupled with the user's ability and ease of use and adaptation to mobile applications, contributed to obtaining the maximum return from the tool.

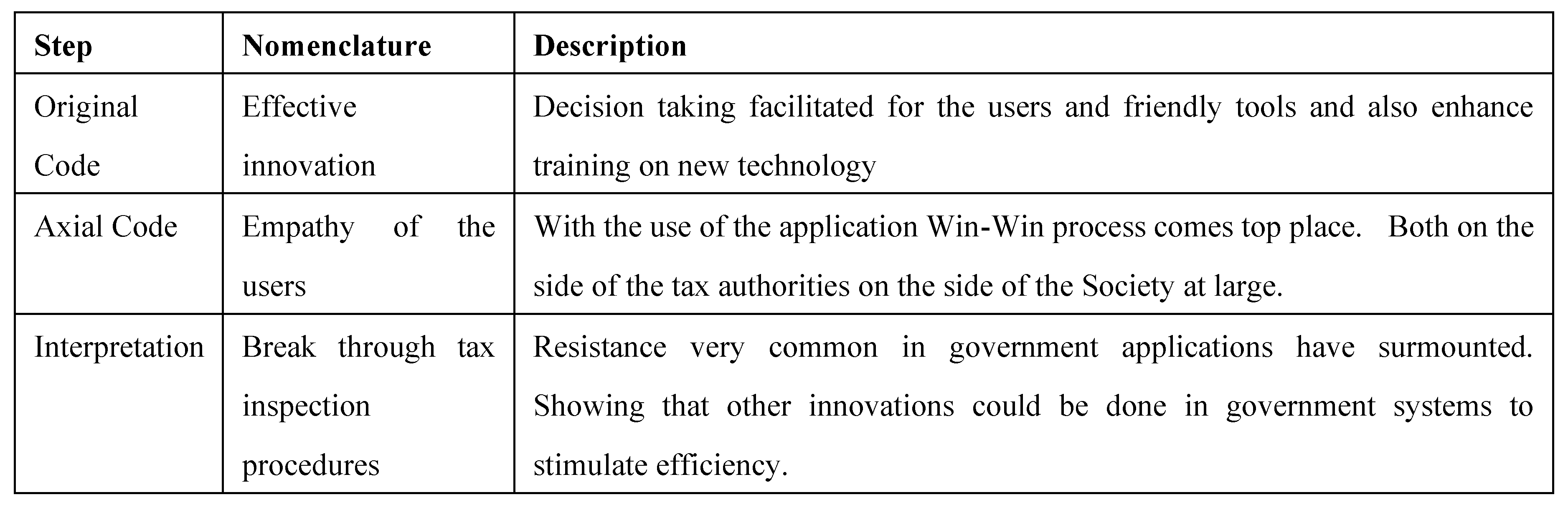

Therefore, the need for and importance of IT tools to help auditors perform their duties in an agile, timely, and effective manner is crucial. It's difficult to believe that in 2023 we'll still be using desktop and client/server tools to perform such a critical and important activity as tax auditing. Another important point that needs to be emphasized is the difficulty in improving an existing application, as the first impression of the application is the one that remains in the users' eyes. Convincing them that the application has changed and is now better much more difficult than creating a new application, even if similar, from scratch, as resistance and previous history are very difficult to overcome.

The key to being assertive and gaining your user's empathy is to understand their needs intimately, as only then will it be possible to offer something truly effective. You need to put yourself in the other person's shoes to create a tool that is truly useful in decision-making. There is no better way.

To overcome user resistance and present the actual changes that were made, the only way was to present the technical side (the application's internal structure), explaining that, although the application appears to be the same, the internals have been completely redesigned. Presenting the internals and providing users with an understanding of the entire process allows them to understand the process and move from being just another critic to becoming a contributor to improving the application and, consequently, improving the auditors' own work. It's about bringing the user, in this case the auditor, into the role of partner, not merely a user of an application that wasn't designed for them and for their own benefit.

It is believed that promoting the app through training was crucial to breaking down the barrier experienced auditors faced with a new tool. Therefore, the training sessions were held in three different locations to facilitate the auditors' transition. This training was sponsored and supported by all the managers who became project partners. The training was divided into two main parts: the theoretical part, which explained everything that had been built and how it worked, as well as real-life cases presented by the traffic auditors themselves, the same ones who participated in the first project meeting; and the practical part, which involved using the app in real-world situations on the roads, demonstrating that it was working, timely, and effective enough for real-world use. The training session was the initial milestone, demonstrating that despite the app's name, it had been completely redesigned internally and was now functioning in real-time, as they needed.

Implementing this tool for tax auditors can even change the way they approach the conductor, demonstrating that the state is using technological solutions to make progress in identifying tax evasion fraud. The tool allows drivers to be approached with a personalized "Good morning." The former approaches used to both scare drivers and demonstrate a more alert inspection team to what's happening on the roads. This all aims to eliminate unfair competition, as a product that arrives in an untrustworthy manner ends up being sold at a lower price than an honest company that pays all its taxes.

Thus, the implementation and use of technological tools by traffic inspectors ensures, according to the legitimacy theory, that their actions are legitimized—that is, their actions are recognized by the public as effective in combating tax evasion. With assertive information, the inspector can demonstrate the legality and accuracy of their approach and, consequently, legitimize the work of tax authorities. The controls implemented by the tax authorities aim to catch recurring frauds that previously escaped more assertive oversight. However, it is important to emphasize that this is a daily struggle, as new ways to circumvent oversight emerge every day. However, with the use of technology, it is possible to quickly, efficiently, and assertively seek new ways to assist tax audits by providing information for an effective approach.

directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion of this study levies on the tax compliance technology in promoting innovation in the government institutions. The analysis focused on the participatory observation of the case of quasi-experiment of an application, inward or outward flow of trucks whose circulating documents ought to be certified for their correctness and completeness by the auditors in the road transportation.

All companies that transport goods on Brazilian roads and transport goods from one state to another on a routine or large scale must have tax documents (MDF-e, CT-e, NF-e) during the transportation of the goods, as well as have paid the ICMS (Tax on Goods and Services) related to the transportation, unless a specific situation exempts them from advance payment, such as an accreditation agreement. These cases must be proven to be considered reputable.

To assess the legitimacy of the information provided by the driver transporting the cargo, the existence of controls that mitigate risks is essential. This paper presents in detail a case study that took place at the Goiás State Department of Economy in 2023. It details how the data collection procedure was carried out, the design of the technical solution, the explanation of each group of main processes and, finally, how this technological solution, including the application and its functionalities, was used to detect possible cases of tax fraud, as well as its impact on the number of infraction notices.

The developed technology simplified the management of complex tax data through the utilisation of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) enabling the validation of documents to records and invariably to the Public Digital Bookkeeping System (SPED). This is an asset to the State of Goias in as much as the public at large getting to know of the use of this tool are refraining from noncompliance of tax rules on tansportation of goods and services.

Suffice it to note that the research question has been answered, as this work will help other states or institutions wishing to implement systemic and technological tools in a business area as specific as tax enforcement, as it involves information technology expertise connected to traffic enforcement practices.

This study also demonstrated the immediate benefits to the legitimacy of tax enforcement, from the change in the way trucks are approached to the prior knowledge that auditors now possess to support their decision-making. They now have information about the vehicle's route history and, through the tax documents associated with the license plate, can profile the type of cargo it typically transports. With this information, they can estimate the tax risk index, as certain goods are more susceptible to tax fraud depending on the region of origin and destination (loading/unloading), compared to other regions.

Another important point was the benefits of a mobile application on the auditor's cell phone. Information was literally placed in the auditor's hands, and a previously unheard-of standardized procedure was created, such as the use of the License Plate Lookup feature for any inspection to identify the vehicle being stopped. This tool helped the inexperienced auditor and also streamlined the work of the experienced auditor. For both, the use of all the technological equipment brought greater agility and assertiveness to traffic inspection work.

As an implication in the public unit, this process is not over; it was only the beginning of this partnership between tax auditors and technology. The fundamental milestone was demonstrating that it is indeed possible to achieve significant results with the use of technological controls, but only if they are handled by someone with technical knowledge and, most importantly, with the partnership and support of experienced professionals, adopting quasi-experiment among the traffic auditors.

This study is the beginning of many more to come as an experiment in the public units. Therefore, as a suggestion for future research, it would be worthy to investigate how artificial intelligence is still needed to validate tuck routes and identify recurring cases of fraud. Additionally, the premise may involve routes versus time; route deviations that should not occur; analyze the use of tax documents; and, finally, projects focusing awareness of tools such as RFID, concurrent, or a posteriori traffic audits.

References

- Brasil. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm Acesso em: 15 junho 2023.

- Brasil. Decreto nº 6.022 de 22 janeiro de 2007. Institui o Sistema Público de Escrituração Digital – Sped. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2007/decreto/d6022.htm. Acesso em: 15 junho 2023.

- Brasil. Lei Complementar nº 116, de 31 de junho de 2003. Dispõe sobre o Imposto Sobre Serviços de Qualquer Natureza, de competência dos Municípios e do Distrito Federal, e dá outras providências. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lcp/lcp116.htm Acesso em: 21 junho 2023.

- Brasil. Lei Complementar nº 87, de 13 de setembro de 1996. Dispões sobre o imposto dos Estados e do Distrito Federal sobre operações relativas à circulação de mercadorias e sobre prestações de serviços de transporte interestadual e intermunicipal e de comunicação, e dá outras providências (Lei Kandir). Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lcp/lcp87.htm Acesso em: 15 junho 2023.

- Brasil. Lei nº 5.172, de 25 de outubro de 1966. Dispõe sobre o Sistema Tributário Nacional e institui normas gerais de direito tributário aplicáveis à União, Estados e Municípios. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l5172compilado.htm Acesso em: 15 junho 2023.

- Brasil. ONE – Operador Nacional dos Estados - Portal do Operador Nacional dos Estados – SVRS. Disponível em: https://dfe-portal.svrs.rs.gov.br/one Acesso em: 05 Julho 2023.

- Casa Nova, Silvia Pereira de Castro et al. TCC trabalho de conclusão de curso: uma abordagem leve, divertida e prática. 2020.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: London: Sage.

- Dias Filho, J. M.; Políticas de evidenciação contábil: Um estudo do poder preditivo e explicativo da teoria da legitimidade. In: EnANPAD, 31, 2007. Rio de Janeiro. Anais... Rio de Janeiro: ANPAD, 2007. CD-ROM.

- Dowling, J. & Pfeffer, J., (1975). "Organizational legitimacy: Societal values and organisational behaviour". Pacific Sociological Review, Vol.18, No. 1, pp.122-136.

- Faria, A. C. D., Finatelli, J. R., Geron, C. M. S., & Romeiro, M. D. C. (2010). SPED–Sistema Público de Escrituração Digital: Percepção dos contribuintes em relação os impactos da adoção do SPED. Recuperado em, 10. Disponível em: https://congressousp.fipecafi.org/anais/artigos102010/248.pdf Acesso em 21 junho 2023.

- Franca, C. S., Imoniana, J. O. Reginato, L. & Cornachionne, E. (2024). Implementation of Data Lake: Narratives of Quasi-outsourcing. Procedia Computer Science 238, 550-557. [CrossRef]

- Harada, K, (2022). ICMS, Doutrina e prática. 3ª. Edição, Editora Dialética: São Paulo.

- Imoniana, J. O., Brunstein, J. & Nova, S. P. C. (2022). The account of teaching qualitative research method in accounting program in Brazil. Educational Research and Reviews 17 (11), 264-272. [CrossRef]

- Silva, D., Carvalho, S. T., & Silva, N. (2022, July). Comparative Analysis of Classification Algorithms Applied to Circular Trading Prediction Scenarios. In Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective: 11th International Conference, EGOVIS 2022, Vienna, Austria, August 22–24, 2022, Proceedings (pp. 95-109). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. London: Sage.

- Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: design and methods, Newbury Park, California: Sage.

- Yin, Robert. Case Study Research: design and methods. 5 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).