1. Introduction

Food contaminants such as aflatoxins (AFs) are one of the main public health problems due to their cancerogenic activity. Aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) is the 4-hydroxylated metabolite of aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), a mycotoxin produced mainly by two ubiquitous fungal species of Aspergillus, i.e.

Aspergillus parasiticus and

Aspergillus flavus, frequently co-occurring with aflatoxin B2, G1 and G2 in a large number of commodities intended for human and animal consumption. In addition, the fungal species producing AFs are able to grow on different cereals (i.e. corn, wheat, rice) and nuts (i.e. pistachios, peanuts, hazelnuts, almonds) dried fruits (i.e. dried figs) and this spread their presence in the food chain [

1]. AFM1 is secreted in milk of mammalian species ingesting food or feed contaminated with aflatoxin B1 and has been shown to be resistant to thermal treatments and to pasteurization. For these reasons AFM1 is commonly found in breast milk, as well as in animal milk and dairy products [

2,

3].

Toxic effects of aflatoxins have been extensively studied since many years and it has been shown that aflatoxins are genotoxic and cause liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) in humans and other animal species. Aflatoxins at high doses are also associated with other adverse health effects such as child growth impairment and immune dysfunction [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The carcinogenicity of AFM1 has been documented only in experimental animals. Since AFM1 is a metabolite of AFB1, it is presumed to have a toxicity similar to that of AFB1 and to induce liver cancer in rats by a mechanism similar to AFB1. The International Agency on Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified aflatoxins as Group 1 carcinogens, i.e. carcinogenic to humans and stated that “there is sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity of naturally occurring mixtures of aflatoxins, and of aflatoxin B1, G1 and M1”[

5].

In order to protect human health, several countries have set regulatory limits for maximum permitted levels of AFM1 in milk [

8,

9,

10,

11], ranging from 0.05 μg/kg in the European Union (EU) [

9] to 0.5 μg/kg in the United States [

10]. In addition, the EU has set lower limits (i.e. 0,025 μg/kg) in infant formulae, follow-on formulae and young-child formulae and in food for special medical purposes intended for infants and young children. At the present, no maximum permitted levels have been set in the EU in dairy products, although EU regulation (article 3) states that where no specific EU maximum levels are set out for food which is dried, diluted or processed changes of the concentration of the contaminant caused by drying or dilution or processing shall be taken into account when applying the maximum levels set out to such food. Consequently, AFM1 limits in cheese (or dairy products) should be established according to the processing factor provided by producers. Accordingly, the Italian Ministry of Health has recently proposed four different enrichment factors, ranging from 3 to 6, to set a limit for AFM1 in soft, semi-soft, semi-hard, hard and very hard cheeses [

12].

Several surveys have been carried out worldwide to estimate AFM1 occurrence in milk and relevant human exposure mainly through milk consumption, although additional exposure to AFM1 should be considered due to consumption of dairy products such as cheese and yogurt [

2,

3,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. These studies have highlighted that several nations, mainly in developing countries such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, have AFM1 levels in milk higher than EU and US regulatory limits for AFM1, indicating potential risk to humans.

The presence of AFM1 in milk and dairy products is a real risk for human health, therefore, rapid and reliable methods for the determination of this contaminant in milk and dairy products are necessary both to comply with regulations and to prevent any risk for consumers.

Several liquid chromatographic methods and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) have been developed for the determination of AFM1 in milk, with the latter used mainly for screening purposes [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In particular, a liquid chromatographic method using immunoaffinity column clean-up and fluorescence detection has been validated and adopted as a standard method by the AOAC International for the determination of AFM1 in liquid milk [

4]. More recently, Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) are routinely used for the determination of AFM1 in milk and derivative products, such as cheeses and fermented milk products, due to their high sensitivity, selectivity and the ability to identify and quantify analytes in complex matrices, allowing also the simultaneous detection of multiple analytes [

26,

27]. However, these instruments demand specialized expertise, are expensive and time-consuming. Biosensors and immunoassays are becoming increasingly useful tools for rapid detection of food contaminants, including AFM1, because they offer several advantages compared to conventional methods, including high specificity and sensitivity, portability (allowing on site detection) and are user-friendly. Antibodies and aptamers are the most used biological recognition elements, although other recognition elements such as enzymes, peptides, nanobodies and molecularly imprinted polymers have been explored. In the case of biosensors, these recognition elements are coupled with a transducer that converts the binding event between the recognition elements and the target analyte into a quantifiable signal (optical, electrochemical, thermal, gravimetric). Concerning immunoassays and aptamer-based assays, such as ELISA and Lateral Flow Assays (LFA), the binding event results in a colorimetric or fluorescence signal that can be measured by a spectrophotometer or fluorimeter or visually, in case of qualitative analysis [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Many commercially available anti-AFM1 antibodies (poli- and monoclonal) with good selectivity and affinity are available promoting the use of immunoassays and biosensors for AFM1 detection [

33,

34]. On the contrary, only few AFM1 aptamers, have been reported in literature showing high affinity toward AFM1, although they showed a good selectivity towards other mycotoxins [

35,

36,

37].

At our knowledge, few reviews have been published in the past years concerning immunoassays [

33], electrochemical immunosensors and aptasensors [

38,

39,

40], aptasensors [

41] and novel biosensors [

34] for AFM1 detection. The present review aims to provide information on recent advances in biosensors and assays based on the use of antibodies and aptamers as molecular recognition element for AFM1 in milk and dairy products. Advantages and limitations of these tools, as well as future research perspectives, are discussed.

2. Antibody-Based Assays/Biosensors for AFM1 Determination

Antibodies (Abs) are proteins belonging to the family of immunoglobulins. Their biological function is to support the immune system by identifying and neutralizing non-self-molecules present in pathogens (e.g. bacteria, viruses, etc.) that penetrate in the body. Each individual antibody molecule is able to specifically recognize one or more molecules [

42,

43] which may possess different size and chemical composition [

44].

It is precisely this characteristic that makes the antibodies as specific molecular recognition elements (MREs) in the design of analytical tools of medical, agrifood and environmental interest. In fact, a biosensor must be extremely specific and selective with regard to the target molecule and this characteristic is ensured by the use of a specific Ab as MRE [

45].

In addition to the characteristics of specificity and selectivity, nowadays it is required that a biosensor should be stable, fast and above all be user-friendly. In fact, it is essential that a biosensor can be used on-site even by non-highly qualified personnel and can provide a rapid analytical response (even at a level of early warning) [

46].

In the agrifood area, user-friendly biosensors represent a valid device for on-the-spot determination of contaminants however, to date biosensors based on the use of antibodies are not available on the market. In fact, the large majority of the commercial analytical assays based on the use of antibody for AFM1 quantification are ELISA or LFIA.

2.1. Optical Immunosensor for AFM1 Detection

A competitive phosphorescent immunosensor for the quantification of AFM1 in milk using quantum dots (QDs) as photoluminescent markers was proposed. Two different analysis strategies were compared, based on the use of QDs as secondary antibody markers (direct analysis) or a derivative of the AFM1-bovine serum albumin antigen (indirect analysis), with the former yielding the best results [

47].

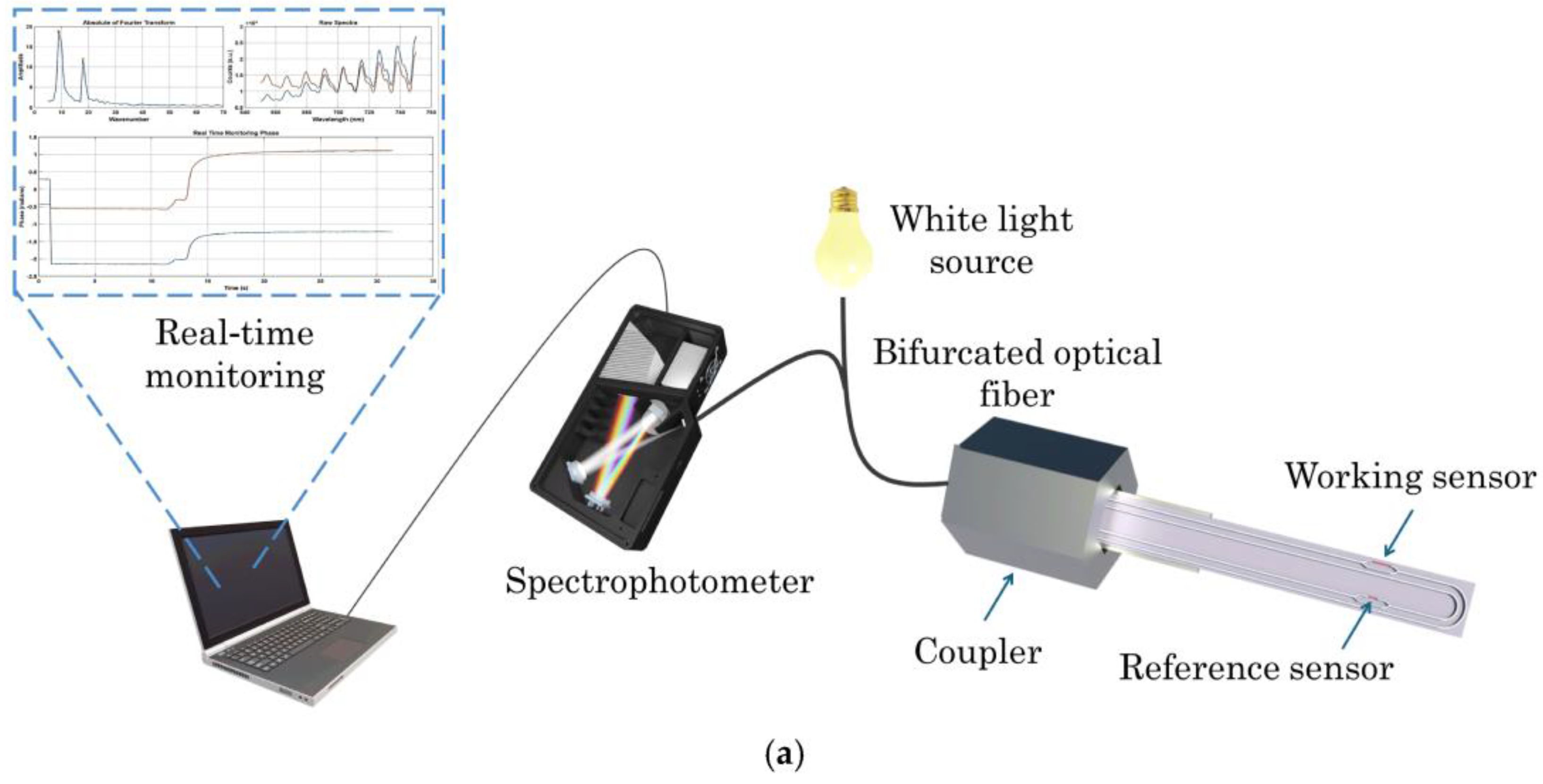

It is worth to report the work of Kourti et al. [

48] that have recently reported a rapid and sensitive method for detecting AFM1 in milk based on an immersible silicon photonic chip (

Figure 1). The chip is composed of two U-shaped silicon nitride waveguides formed as Mach-Zehnder interferometers. One interferometer is functionalized with AFM1-bovine serum albumin conjugate and the other with bovine serum albumin alone to serve as a blank. The chip is connected to a broad-band white LED and a spectrophotometer by a bifurcated optical fiber and an assay is performed by immersing the chip in a mixture of milk with the anti-AFM1 antibody. Then, the chip is sequentially immersed in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody and streptavidin solutions for signal enhancement. The assay is completed in 20 min and the detection limit for AFM1 in undiluted milk is 20 pg/mL.

Angelopoulou and coworkers proposed a silicon-based optoelectronic immunosensor that uses a three-step competitive immunoassay for AFM1 detection, comprising the primary reaction with a polyclonal anti-AFM1 antibody, followed by a biotinylated polyclonal anti-IgG antibody and finally streptavidin to regenerate the chip [

49]. The sensor was tested in milk, chocolate milk and yogurt with calculated LODs of for the former matrices 0.005 ng/mL, and 0.01 ng/mL for the latter. Interestingly, no pretreatment procedures were necessary on milk.

2.2. Strip-Based Immunosensor for AFM1 Detection

Wu and coworkers developed an immunochromatographic test based on the concept of antigen competition for the simultaneous detection of AFM1 and chloramphenicol (CAP) in milk. Specifically, ovalbumin conjugates of the two compounds and goat anti-rabbit IgG were adsorbed onto a membrane as two test lines (T1 and T2) and a control line (C), respectively. For analysis, the strip is immersed in a well containing the sample, the AFM1-gold conjugates and the CAP-gold conjugates. Focusing on the detection of AFM1, its presence is correlated with the absence of a red line in the T1 zone of the immunological strip. In fact, if its level in the sample exceeds a certain value, the AFM1 toxins occupy the AFM1 antibody binding sites on all the gold nanoparticles, and the nanoparticles, responsible for the red colour, do not bind to the AFM1-ovoalbumin conjugate in the T1 line on the immunostrip [

50].

2.3. Electrochemical-Based Immunosensor for AFM1 Detection

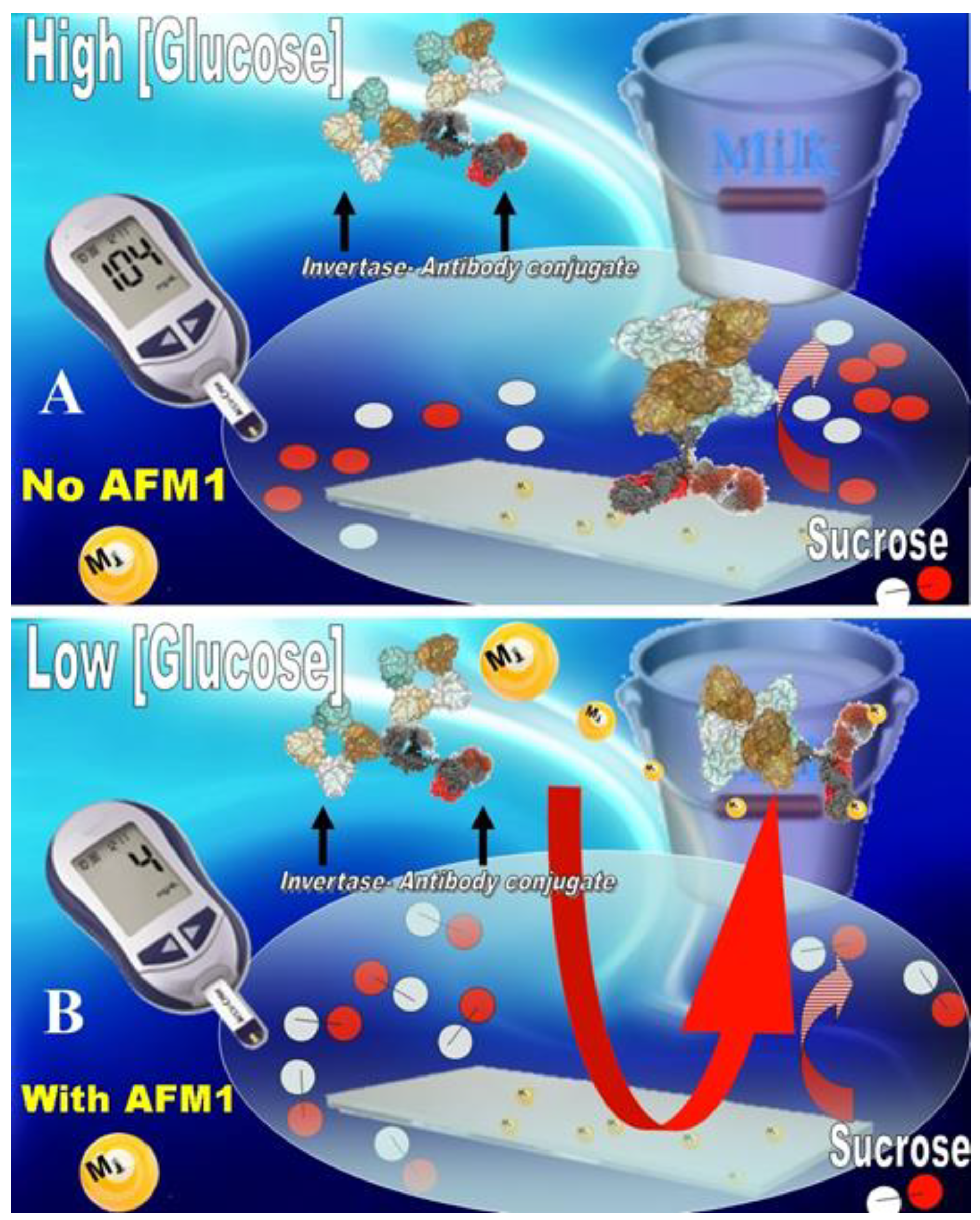

Recently, it has been reported the design of a different method for a rapid detection of the AFM1 in milk-collected daily by farmers [

51]. This method is based on the use of an ad-hoc engineered glucometer device. In particular, an immune-detection strip containing invertase-conjugated to antibody anti-AFM1 was produced, and a competitive assay was developed. This assay was able to detect the presence of twenty-seven parts per trillion (ppt) of AFM1 in whole milk (below the EU maximum permitted level) by measuring the glucose produced by the invertase-conjugated antibody anti-AFM1 strip after one hour of incubation time (

Figure 2).

The novelty of this method is that it only requires to produce glucose by an invertase-linked immune-sorbent assay (InLISA) and to monitor it by a simple glucose detection through a commercial glucometer.

Erdil and collaborators proposed a paper-based biosensor device based on a competitive test as an alternative method for the detection of AFM1 which uses magnetic nanoparticles to increase the signal [

52]. Moreover, an electrochemical immunosensor based on screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCE) functionalized with anti-idiotypic nanobodies for the detection of AFM1 was designed [

53], showing a linearity range between 0.25 and 5.0 ng/mL, and a detection limit of 0.09 ng/mL. In spiked milk samples, recovery rates were from 82.0% to 108.0% and RSD values from 10.1% to 13.0%.

3. Aptamer-Based Assays/Biosensors for AFM1 Determination

Aptamers are short synthetic single-stranded nucleotide sequences selected from a randomized library of oligonucleotides through a process known as SELEX (Sequential Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment). Aptamers have been used as a bio-recognition element in a variety of sensors (

Table 1) due to their remarkable characteristics such as low immunogenicity and toxicity, low production cost, high affinity for their targets, ease of modification [

54]. Compared to antibodies, aptamers have lower costs, greater ease of production, higher affinity, greater chemical and thermal stability [

55,

56].

3.1. Colorimetric-Based Aptasensor for AFM1 Detection

Several technologies in this field exploited the different tendency of AuNPs to aggregate in the presence or absence of the toxin which leads to a colour change, to an extent proportional to the amount of target content. Among these, Kasoju and coworkers developed a paper microfluidic device for AFM1 detection as convenient alternative for on-site detection technologies [

55]. The proposed technology is based on an aptamer/AuNPs complex arising from the physisorption of specific aptamers onto the surface of AuNPs. In the presence of AFM1, the aptamer dissociated from AuNPs that resulting in aggregation and solution colour change from wine red to blue. The ratio between the absorbance values at 630 and 520 nm was used to determine the aggregation. In addition to spectroscopic method, the presence of the toxin was detected with the naked eye. The concentration range was from 1 μM to 1 pM, with a LOD of 3 pM and 10 nM in spiked water and milk samples, respectively. Moreover, the device was stable at room temperature for up to 3 months. Another aptasensor based on the principle that AuNPs in NaCl solution do not aggregate when the toxin is present and aggregate in its absence has been proposed. In detail, AuNPs are added to a suspension containing aptamer-modified streptavidin-coated silica nanoparticles, complementary filament of the aptamer and the sample to be analysed. in the presence of the toxin, the complementary filament detaches from the silica NPs and stabilises the AuNPs in the presence of NaCl [

54]. The quantification was carried out by monitoring the absorbance ratio at 650 and 520 nm. The obtained linear dynamic range was between 300 and 75,000 ng/L, with a LOD of 30 ng/L. In AFM1 spiked milk samples, the low detection limit was 45 ng/L and the recovery between 92 and 109.5%. Tests performed incubating the sensor with other toxins, such as OTA, ZEN, DON and AFB1, showed great specificity toward AFM1 toxin.

Wei et al prepared a sensor based on the interaction between aptamer-modified AuNPs@CuO and cDNA-Modified Fe3O4 [

57]. They screened the better aptamer by using a combination of a five-segment library and GO-SELEX. With the selected sequence, the assay displayed linearity in the range 0.5−500.0 ng/mL and a detection limit of 0.50 ng/mL. In milk powder the detection recovery was around 92.8−105.2%. For comparison, the recoveries obtained with the ELISA test were investigated, which ranged between 89.20 and 93.10%.

A test strip allowing a visual detection of the AFM1 in the samples was obtained by developing an aptamer-based lateral flow assay (LFA) based on AuNPs [

56]. The concentration of AFM1 was inversely proportional to the signal and was given by relative colorimetric signal intensity of AuNPs at the control and test line after 10 minutes of incubation. For the quantitative analysis, photographs of the test strips were taken and analysed with ImageJ. The linear range was from 0 to 500 ng/mL, and the detection limit of 0.21 ng/mL. The sensor demonstrated to be specific for AFM1 detection with recoveries in milk samples ranging from 92% to 104.3%.

3.2. Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Aptasensor for AFM1 Detection

A label-free colorimetric aptasensor was developed by Lerdsri et al by exploiting localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [

58]. The sensor exploited competitive interactions of the aptamer to the AFM1 or the AuNPs under a specific condition by using sodium chloride to aggregate AuNPs. In particular, the aptamer interacting selectively with AFM1 change its structure and is therefore no longer able to prevent NaCl-induced aggregation of AuNPs that causes a redshift of the LSPR absorption spectrum The linear response was found from 0.005 to 0.100 ng/mL and the detection limit was 0.002 ng/mL. The percentages of recovery obtained in milk samples were in the range of 80.5–89.7 %, with an RSD valued lesser than 10%.

3.3. Fluorescence-Based Aptasensor for AFM1 Detection

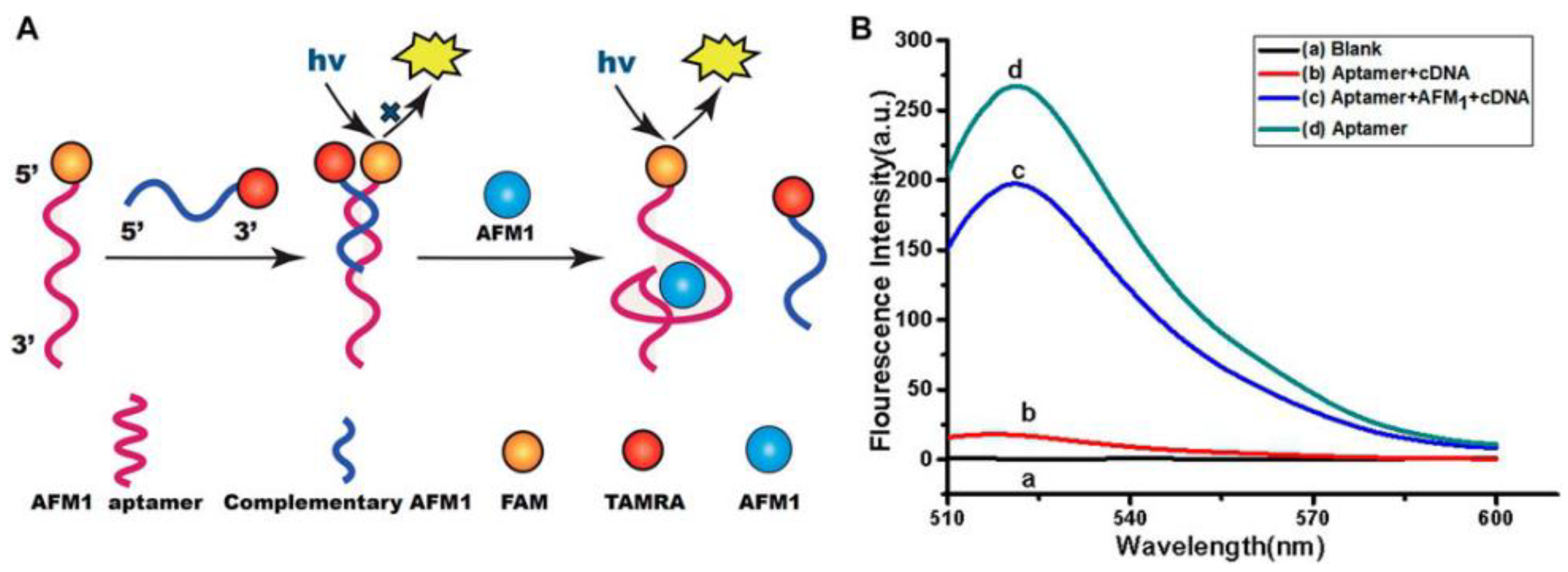

Technologies based on quenching or modification of the fluorescence signal due to changes in structural conformations have been proposed in several studies and are recognised as promising for the sensing of biomolecules due to their enhanced sensitivity and specificity [

59]. In this perspective, Qiao and collaborators designed an aptasensor based on the generation of fluorescence signals in presence of AFM1 toxin [

60]. In detail, the AFM1 aptamer was functionalized with carboxyfluorescein while complementary DNA sequences (cDNA) were implemented with a carboxytetramethylrhodamine group. When AFM1 was not present, the aptamers were hybridized with cDNA, causing a fluorescence quenching. In the presence of AFM1, an AFM1/aptamer complex formed, leading to the release of the cDNA and a consequent generation of a fluorescence signal (

Figure 3). Under optimized conditions, the sensor displayed linearity from 1 to 100 ng/mL AFM1 concentration and a LOD of 0.5 ng/mL. In milk samples, recoveries from 93.4 to 101.3% were obtained.

Aran et al developed a fluorescence-based aptasensor which allowed the simultaneous visual detection of AFM1 and chloramphenicol [

61]. To this end, a DNA hydrogel was obtained by using an acrydite-modified chloramphenicol aptamer sequence which underwent a gel-to-sol transition in the presence of chloramphenicol. The LOD and LOQ values for AFM1 were 1.7 and 5.2 nM, respectively. Recovery range obtained in milk samples steps was between 91.3 and110.2%.

A multiplexed detection of AFB1 and AFM1 in PBS 1X, milk and serum was obtained by preparing ternary transition metalsulfides-based PEGylated nanosheets and exploiting the fluorescence turn-on mechanism as a consequence of conformational changes due to the formation of aptamer/toxin complexes [

62]. For AFM1 toxin, a linear response was obtained between 10

−12 and 5 × 10

−7 M in PBS 1X, 2.5 × 10

−12 - 5 × 10

−7 M in milk and 10

−11− 5 × 10

−7 M in serum. The LOD values were about 1 pM, 9.87 pM, 9.59 pM in PBS 1X, milk and serum respectively. The recoveries in milk ranged from 96.67 to 101.65%.

Cai and collaborators proposed a sensor for the simultaneous detection of AFB1 and AFM1 toxins by integrating the properties of functionalized graphene oxide and aptamers [

63]. The fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) mechanism was exploited for the detection and a LOD of 8.7 pg/mL for AFB1 and 20.1 pg/mL for AFM1 was obtained. Also, a label-free fluorescent aptasensor for AFB1 and AFM1 detection was obtained by truncating and mutating stem region bases in a 28 nt aptamer resulting in a LOD of 0.0060 ng/mL and 0.010 ng/mL for the two toxins, respectively [

64]. Finally, Naz and collaborators proposed a dual-mode sensor for AFM1 detection by exploiting Covalent organic framework-based aptananozymes [

65]. The designed architecture allowed to detect the presence of the toxic by generating a colorimetric signal, detectable also with naked eyes, and a fluorescent signal, with LOD values of 7 and 5 pg/mL, respectively.

3.4. Electrochemical-Based Aptasensor for AFM1 Detection

Electrochemical-based aptasensors involve different techniques, such as cyclic voltammetry (CV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and analysis of capacitive signals

. Moreover, several technologies in this field relied on the use of NPs. In detail, an electrochemical aptamer-based sensor was developed using an amino-functionalized dendritic fibrous nanosilica (KCC-1-nPr-NH2) and gold nanoparticle supported by chitosan (AuNPs-CS) with a unique toluidine-labelled aflatoxin M1 oligonucleotide docked at the interface [

66]. The quantification of AFM1 was achieved by means of CV, SWV and DPV. Square Wave Voltammetry proved to be the most accurate technique for the determination of AFM1. The linear range was from 10 fM to 0.1 μM, with Lower Limit Of Quantification (LLOQ) of 10 fM. In pasteurized milk spiked with AFM1, the LLOQ for DPV and SWV measurements was 10 fM. The sensor was stable up to four days.

Hamami et al proposed a screen-printed carbon electrode aptasensor implemented with AuNPs, ferrocene tetraethylene glycol ligand and an anti-AFM1 aptamer [

67]. Here, the ferrocene was bound to AuNPs and acted as a capacitance transducer, while PEG was effective in preventing non-specific adsorption of biomolecules or microbials. The sensor showed a dynamic range of 20 to 300 pg/mL, with a capacitance signal decreasing with increasing AFM1 concentrations. The LOD was from 7.14 pg/mL (S/N = 3). The platform exhibited high selectivity toward AFM1 even in the presence of 1000 folds of interferents toxins concentrations (ochratoxin B and picrotoxin) and the analysis carried out in AFM1 spiked pasteurized cow milk showed recovery percentage in the range 101.6 – 105.5%.

Also, an electrospun carbon nanofiber mat was developed for the detection of AFM1 toxin [

68]. Here, the electrode was implemented with AuNPs and thiol-modified single stranded DNA. Cyclic voltammetry was exploited to quantify the toxin. The sensor showed a detection limit of about 0.6 pg/mL and linearity in the range 1-100 pg/mL. Moreover, it displayed good selectivity against AFB1 and AFB2 toxins, good reproducibility and stability for at least 16 days. Recoveries in milk samples were in a range from 106–109%, comparable to HPLC results.

Another electrochemical aptasensor for AFM1 was designed by using Apts-Au@Ag, cDNA2-Au@Ag conjugates and methylene blue as electroactive substance [

69]. Differential pulse stripping voltammetry was used for the quantification of the toxin. The linear detection range was from 0.05 ng/mL to 200 ng/mL and the LOD of about 0.02 ng/mL. This sensor also showed good reproducibility, stability and selectivity. Recoveries in cow, goat, and sheep milk samples ranged from 89.00 % to 104.05% and the RSD from 4.3 to 7.9%.

A label-free electrochemical aptasensor was developed exploiting a reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and AuNPs-based pencil graphite electrode with the aptamer self-assembled on the surface [

70]. The detection was carried out by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The sensor displayed a linear concentration range of 0.5–800 ng/L and LOD of 0.3 ng/L. Stability tests showed that the platform kept 91% of its initial response after 14 days at 4 °C. Analysis performed in raw, low-fat pasteurized and full-fat pasteurized milk spiked with AFM1 (50 ng/L) showed average recoveries of 92.0%, 108.0%, and 90.0% and RSD ranging from 5.2%, 4.5%, and 5.7%, respectively.

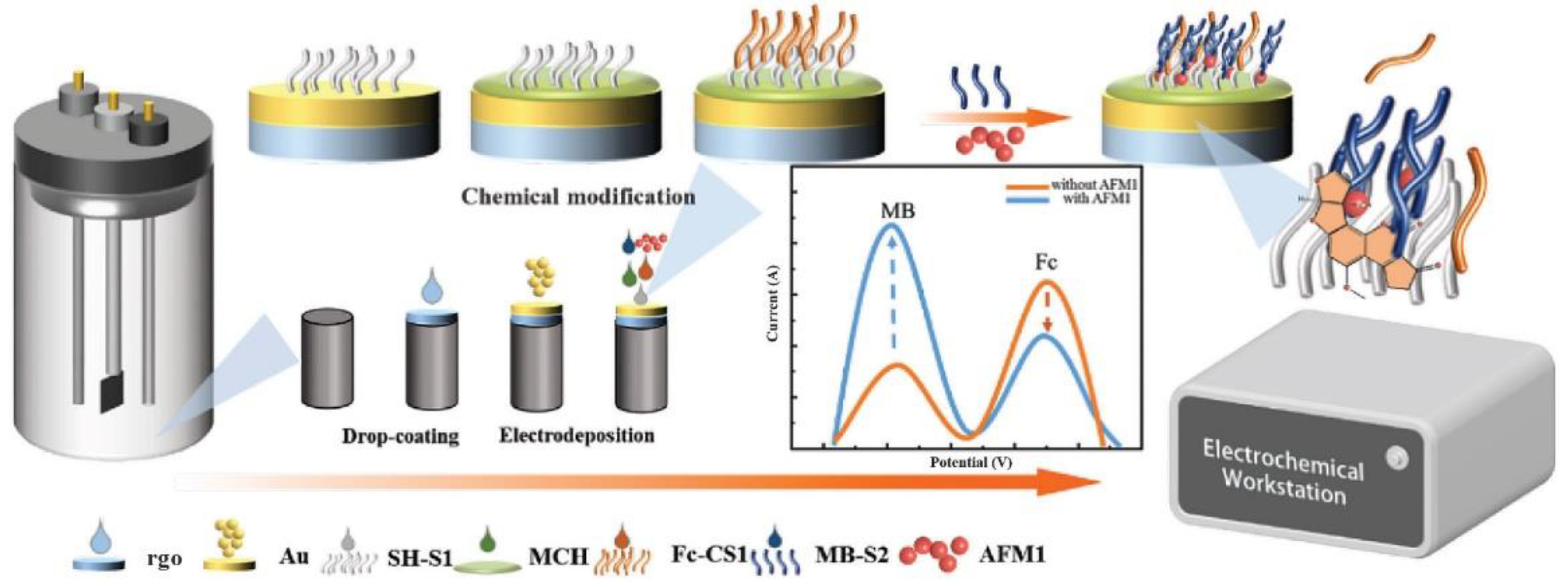

Au-rGO nanomaterials were also used by Li and collaborators [

71] to develop a ratiometric electrochemical aptasensor with the AFM1 aptamer split in two portions (S1 and S2), and square waver voltammetry peak current was monitored for the AFM1 quantification (

Figure 4). Specifically, S1 was anchored on the rGO-modified electrode and S2 was modified with methylene blue (S2). A complementary strand to S1 with ferrocene was added. In the presence of the toxin, the complementary strand was released from the electrode surface, leading to a decrease in ferrocene and an increase in the methylene blue signal. They obtained a linear range for the quantification of 0.03 μg/L - 2.00 μg/mL and a LOD of 0.015 μg/L. While in milk the linearity was from 0.2 μg/L - 1.00 μg/L and the detection limit of 0.05 μg/L.

The molecular imprinting technique (MIT) is useful for preparing molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) with cavities that precisely fit the target molecule [

72]. In particular, aptamers can be combined with MIPs to fabricate a selective sensor. Yang et al designed a molecularly imprinted polymer and aptamer based electrochemical sensor with two recognition elements,

i.e. aptamer and MIP, to detect AFM1 in milk [

73]. The DPV current was then analysed. The platform showed a linear range of 0.01–200 nM and a limit of detection of 0.07 nM (S/N = 3). The stability was about 88% after 21 days and the recoveries in goat, sheep, and cow milk were in the range 97.9%–105.0%, 95.4%–102.1%, and 96.0%–105.6%, respectively.

A dual-functionalized electrochemical aptasensor was proposed by Huma and collaborators made of COOH-functionalized AFM1 aptamer and hydroxyazobenzene polymers at pencil graphite electrodes (PGE) [

74]. Hazo-POPs exhibit both electroactive potential and peroxidase activity, thus two methods have been tested. Method I involved CV measurements and worked in Phosphate-Buffer Saline (PBS) solution and the PGE was implemented with Hazo-POPs@COOH-Apt to optimize the electrochemical response. Method II employed DPV measurements in acetate buffer and exploited the peroxidase activity of Hazo-POPs. The biosensor showed a linear range from 0.005 to 500 nM, with LODs of 0.004 and 0.003 nM for method I and II, respectively. The recoveries in spiked milk samples were from 101.2 to 104.0 % with RSD values inferior to 3.

An electrochemiluminescence micro-reactor with increased intensity and stability was developed exploiting the assembly of tris(2,20-bipyridyl) ruthenium(II) onto covalent organic frameworks and used as aptasensor for the detection of AFM1 toxin [

75]. The sensor showed a linear response from 0.03 pg/mL to 0.3 mg/mL toxin concentration and a detection limit of 0.009 pg/mL in optimized conditions, while the recovery in defatted milk was about 93.3–104.0%.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

As shown in this review, continuous efforts are being made to develop rapid, low-cost and reliable immuno- or aptamer-based biosensors and assays for the determination of AFM1 in milk and dairy products.

Table 2 summarizes major advantages and limitations of antibody- and aptamer-based biosensors and assays. Compared to immunosensors, aptasensors have lower cost of production, lower batch-to-batch variability, higher affinity, customizable modification, and chemical and thermal stability. In addition, aptamers offer more flexibility without the ethical issues associated with the production of antibodies in animals.

One of the main challenges in aptasensor development is their limited sensitivity when detecting small molecules, as they typically possess only a single binding site. Additionally, the environmental conditions of real samples differ considerably from those of laboratory buffers, often resulting in non-specific binding and false-positive results. To address these issues, the development of split aptamers, a post-SELEX modification aimed to divide a parent aptamer into smaller functional fragments with high affinity and specificity, has emerged as a promising strategy. Split aptamers are particularly well-suited for detecting small molecules with limited binding sites, offering increased flexibility and precision in sensor applications. This innovative approach has recently been applied to successfully detect some mycotoxins, including AFM1 [

76,

77].

Despite the great number of advantages of aptamers compared to antibodies, currently, commercially available Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA) and lateral flow immunoassays (LFIA) or strip tests are commonly used for fast and quantitative detection of AFM1 in milk samples due to their high specificity, rapid responses and good sensitivity, and nowadays LFIA is one of the most promising technologies for the rapid and on-site detection of AFM1 in milk. This technology has several advantages that make it particularly useful in the food safety sectors, including of being cost-effective, user-friendly and sensitive. LFIA tests do not require sophisticated equipment or highly trained personnel, making them ideal for field monitoring. It is particularly advantageous for rapid testing and real-time screening. However, milk is a complex matrix containing a variety of components that could interfere with the recognition process and cause false positive results, so confirmatory methods (i.e. HPLC-FL or LC-MS/MS) are mandatory. In addition, milk of different origin varies consistently in their composition and the same sensor/assay developed for a type of milk could be not applied to other types of milk samples. Preliminary treatment of the sample is often necessary. In case of dairy products, such as cheese and yogurt, an extraction step with organic solvents is mandatory, as well as a clean-up step before quantification of AFM1.

Many biosensors have been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity, enabling rapid detection of a wide range of analytes in complex samples. However, their use for the determination of AFM1 in milk in quality control laboratories and directly on farms or milk collection centers is still limited due to their unreliability. To date, no official method based on biosensors has been recognized and adopted as reference method. However, biosensors have been shown to have potential application for on-site measurements, although at present only one biosensor has been developed, combined with a portable glucose-meter, for the determination of AFM1 in whole milk at levels lower than EU regulatory limits [

51]. More efforts should be made to adapt the current developed biosensors to portable devices.

In silico studies on binding mechanisms and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning with neural networks could further optimize antibody/aptamer selection and splitting strategies in order to design effective biosensors to be used for the detection of small molecules in complex matrices. The next generation of biosensors based on innovative nanostructures to increase sensitivity and stability could lead in the next future to realize reliable devices able to compete with other analytical methods currently available.

5. Patents

A Method for detecting Mycotoxins in milk, derivates and dairy products. Inventors: Di Giovanni, Stefano; Zambrini, Angelo Vittorio; D'Auria, Sabato. Publication Number WO/2015/063716. Publication Date 07.05.2015

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.M. and S.D.; methodology, A.M.M., S.D. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.M., M.P. and S.D.; writing—review and editing, A.M.M., L.C., M.P., S.D. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tola, M.; Kebede, B. Occurrence, importance and control of mycotoxins: A review. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, A.S.; Jokar, M.; Abdous, A.; Rabiee, M.H.; Biglo, F.H.B.; Rahmanian, V. Prevalence and concentration of aflatoxin M1 in milk and dairy products: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. International Health 2025, 17, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha Turna, N.; Wu, F. Aflatoxin M1 in milk: A global occurrence, intake, & exposure assessment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.; Pokharel, A.; Scott, C.K.; Wu, F. Aflatoxin M1 in milk and dairy products: The state of the evidence for child growth impairment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 193, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Aflatoxins. In: Chemical Agents and Related Occupations, I.M.o.t.E.o.C.R.t.H. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Aflatoxins. In: Chemical Agents and Related Occupations, I.M.o.t.E.o.C.R.t.H., Volume 100F, pages 225-248. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, 2012, ISBN 978-92-832-1323-9.

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), I.S.e.o.c.c.i.f. Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), I.S.e.o.c.c.i.f., WHO Food Additives Series: 74, FAO JECFA Monographs 19bis, pages 3-280. World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations, Geneva, 2018, ISBN 978-92-4-166074-7.

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Risk assessment of aflatoxins in food, E.J. EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Risk assessment of aflatoxins in food, E.J., 18(3), 6040. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO). Worldwide regulations for mycotoxins in food and feed in 2003. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 81. FAO 2004, I.

- of the European Union, 2023, L 119/103-157., E.C.C.R.E.o.A.o.m.l.f.c.c.i.f.a.r.R.E.N.O.J.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 2005. 527.400 Whole milk, L.f.m. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 2005. 527.400 Whole milk, L.f.m., skim milk–aflatoxin M1 (CPG 7106.10). FDA/ORA Compliance Policy Guides (available at https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cpg-sec-527400-whole-milk-lowfat-milk-skim-milk-aflatoxin-m1.

- Codex Alimentarius, C.-G.s.f.c.a.t.i.f.a.f.A.i.R.i. , 2006, 2008, 2009. Amended in 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024 (available at https://www. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Ministry of Health, D.-M.-P.n. , 23/12/2019. Conclusione dell’attività del gruppo di lavoro per la classificazione dei formaggi e definizione dei fattori di concentrazione (art. 2 del regolamento CE 1881/2006 e s.m.i.) di aflatossina M1 (available at https://www.alimenti-salute.it/doc/11Nota_ministeriale.pdf).

- Arghavan, B.; Kordkatuli, K.; Mardani, H.; Jafari, A. A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Prevalence of Aflatoxin M1 in Dairy Products in Selected Middle East Countries. Veterinary Medicine and Science 2025, 11, e70204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, Y.; Ranaei, V.; Pilevar, Z.; Sarkhosh, M.; Sarafraz, M.; Abdi-Moghadam, Z.; Javid, R. Prevalence and Concentration of Aflatoxin M1 in Mother Milk: A Meta-analysis, Meta-regression, and Infants’ Health Risk Assessment. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, J.Y.; Debella, A.; Eyeberu, A.; Mussa, I. Prevalence and concentration of aflatoxin M1 in breast milk in Africa: a meta-analysis and implication for the interface of agriculture and health. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malissiova, E.; Tsinopoulou, G.; Gerovasileiou, E.S.; Meleti, E.; Soultani, G.; Koureas, M.; Maisoglou, I.; Manouras, A. A 20-Year Data Review on the Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products in Mediterranean Countries—Current Situation and Exposure Risks. Dairy 2024, 5, 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summa, S.; Lo Magro, S.; Vita, V.; Franchino, C.; Scopece, V.; D’Antini, P.; Iammarino, M.; De Pace, R.; Muscarella, M. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw and Processed Milk: A Contribution to Human Exposure Assessment After 12 Years of Investigation. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, C.; Rodriguez, R.; Fernández-Baldo, M.A.; Durán, P. Mycotoxins in Cheese: Assessing Risks, Fungal Contaminants, and Control Strategies for Food Safety. Foods 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, A.; Cabral Silva, A.C.; Rodrigues, P.; Venâncio, A. Detection Methods for Aflatoxin M1 in Dairy Products. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, D.; Morsi, R.; Usman, M.; Meetani, M.A. Recent Advances in the Chromatographic Analysis of Emerging Pollutants in Dairy Milk: A Review (2018–2023). Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolarič, L.; Šimko, P. Development and validation of HPLC-FLD method for aflatoxin M1 determination in milk and dairy products. Acta Chim. Slovaca 2023, 16, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, R.; Bovo, D.; Noviello, S.; Contiero, L.; Barberio, A.; Angeletti, R.; Biancotto, G. Fate of aflatoxin M1 from milk to typical Italian cheeses: Validation of an HPLC method based on aqueous buffer extraction and immune-affinity clean up with limited use of organic solvents. Food Control 2024, 157, 110149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorelli, I.; Guarducci, N.; von Holst, C.; Bibi, R.; Pascale, M.; Ciasca, B.; Logrieco, A.F.; Lattanzio, V.M.T. Critical Comparison of Analytical Performances of Two Immunoassay Methods for Rapid Detection of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk. Toxins 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggira, M.; Ioannidou, M.; Sakaridis, I.; Samouris, G. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk Using an HPLC-FL Method in Comparison with Commercial ELISA Kits—Application in Raw Milk Samples from Various Regions of Greece. Veterinary Sciences 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, D.; Angelopoulou, M.; Petrou, P.; Kakabakos, S. Sensitive Aflatoxin M1 Detection in Milk by ELISA: Investigation of Different Assay Configurations. Toxins 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.N.; Massarolo, K.C.; Ardohain, E.N.G.; Lima, J.F.; Ferreira, F.D.; Drunkler, D.A. Method for Determination of Multi-mycotoxins in Milk: QuEChERS Extraction Modified Followed by HPLC-FL Analysis. Food Analytical Methods 2024, 17, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavicich, M.A.; Compagnoni, S.; Meerpoel, C.; Raes, K.; De Saeger, S. Ochratoxin A and AFM1 in Cheese and Cheese Substitutes: LC-MS/MS Method Validation, Natural Occurrence, and Risk Assessment. Toxins 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Sahu, P.P. Biosensors in food safety and quality: Fundamentals and applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC: 2022.

- Inês, A.; Cosme, F. Biosensors for Detecting Food Contaminants—An Overview. Processes 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Hu, S.; Lai, X.; Peng, J.; Lai, W. Developmental trend of immunoassays for monitoring hazards in food samples: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Saleh, R.O.; Kadhum, W.R.; Saleh, E.A.M.; Kassem, A.F.; Noori, S.D.; Alawady, A.h.; Kumar, A.; Ghildiyal, P.; Kadhim, A.J. Research progress on aptamer-based electrochemiluminescence sensors for detection of mycotoxins in food and environmental samples. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, M.A.; Karaosmanoglu, H.; Wu, Y.; Partridge, A. Biosensor Platforms for Detecting Target Species in Milk. In Food Biosensors, Ahmed, M.U.; Zourob, M., Tamiya, E., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry, Special Collection: 2016 ebook collection,, Series: Food Chemistry, Function and Analysis, 71-103: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matabaro, E.; Ishimwe, N.; Uwimbabazi, E.; Lee, B.H. Current Immunoassay Methods for the Rapid Detection of Aflatoxin in Milk and Dairy Products. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2017, 16, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Meng, M.; Li, W.; Xiong, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lin, Q. Emerging biosensors to detect aflatoxin M1 in milk and dairy products. Food Chemistry 2023, 398, 133848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, M.; Wen, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, T.; Lou, X.; Wang, M.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; Xie, K. Aptamers for aflatoxin M1: from aptasensing technology to commercialization. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.

- Malhotra, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Rajput, Y.S.; Sharma, R. Selection of aptamers for aflatoxin M1 and their characterization. Journal of Molecular Recognition 2014, 27, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.H.; Tran, L.D.; Do, Q.P.; Nguyen, H.L.; Tran, N.H.; Nguyen, P.X. Label-free detection of aflatoxin M1 with electrochemical Fe3O4/polyaniline-based aptasensor. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2013, 33, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurban, A.-M.; Epure, P.; Oancea, F.; Doni, M. Achievements and Prospects in Electrochemical-Based Biosensing Platforms for Aflatoxin M1 Detection in Milk and Dairy Products. Sensors 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitollahi, H.; Tajik, S.; Dourandish, Z.; Zhang, K.; Le, Q.V.; Jang, H.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Shokouhimehr, M. Recent Advances in the Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Biosensors for Detecting Aflatoxin B1 and Its Pertinent Metabolite Aflatoxin M1. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurner, F.; Alatraktchi, F.A.a. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensing of aflatoxin M1 in milk – A mini review. Microchemical Journal 2023, 190, 108594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, N.M.; Bostan, H.B.; Abnous, K.; Ramezani, M.; Youssefi, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Karimi, G. Ultrasensitive detection of aflatoxin B1 and its major metabolite aflatoxin M1 using aptasensors: A review. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 99, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeway, C.A.J.; Travers, P.; Walport, M. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease., 5th edition ed.; Garland Science, N.Y., Ed.; 2001.

- Litman, G.W.; Rast, J.P.; Shamblott, M.J.; Haire, R.N.; Hulst, M.; Roess, W.; Litman, R.T.; Hinds-Frey, K.R.; Zilch, A.; Amemiya, C.T. Phylogenetic diversification of immunoglobulin genes and the antibody repertoire. Molecular biology and evolution 1993, 10, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, I.A.; Stanfield, R.L. 50 Years of structural immunology. The Journal of biological chemistry 2021, 296, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staiano, M.; Bazzicalupo, P.; Rossi, M.; D'Auria, S. Glucose biosensors as models for the development of advanced protein-based biosensors. Molecular bioSystems 2005, 1, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edite Bezerra da Rocha, M.; Freire, F.d.C.O.; Erlan Feitosa Maia, F.; Izabel Florindo Guedes, M.; Rondina, D. Mycotoxins and their effects on human and animal health. Food Control 2014, 36, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcada, S.; Sánchez-Visedo, A.; Melendreras, C.; Menéndez-Miranda, M.; Costa-Fernández, J.M.; Royo, L.J.; Soldado, A. Design and Evaluation of a Competitive Phosphorescent Immunosensor for Aflatoxin M1 Quantification in Milk Samples Using Mn:ZnS Quantum Dots as Antibody Tags. Chemosensors 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, D.; Angelopoulou, M.; Makarona, E.; Economou, A.; Petrou, P.; Misiakos, K.; Kakabakos, S. Aflatoxin M1 Determination in Whole Milk with Immersible Silicon Photonic Immunosensor. Toxins 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, M.; Kourti, D.; Misiakos, K.; Economou, A.; Petrou, P.; Kakabakos, S. Mach-Zehnder Interferometric Immunosensor for Detection of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk, Chocolate Milk, and Yogurt. Biosensors 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-W.; Ko, J.-L.; Liu, B.-H.; Yu, F.-Y. A Sensitive Two-Analyte Immunochromatographic Strip for Simultaneously Detecting Aflatoxin M1 and Chloramphenicol in Milk. Toxins 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovanni, S.; Zambrini, V.; Varriale, A.; D'Auria, S. Sweet Sensor for the Detection of Aflatoxin M1 in Whole Milk. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12803–12807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, K.; Akcan, Ö.G.; Gül, Ö.; Gökdel, Y.D. A disposable MEMS biosensor for aflatoxin M1 molecule detection. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2022, 338, 113438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Catanante, G.; Huang, X.; Marty, J.-L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P. Screen-printed electrochemical immunosensor based on a novel nanobody for analyzing aflatoxin M1 in milk. Food Chemistry 2022, 383, 132598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalalian, S.H.; Lavaee, P.; Ramezani, M.; Danesh, N.M.; Alibolandi, M.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M. An optical aptasensor for aflatoxin M1 detection based on target-induced protection of gold nanoparticles against salt-induced aggregation and silica nanoparticles. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2021, 246, 119062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasoju, A.; Shahdeo, D.; Khan, A.A.; Shrikrishna, N.S.; Mahari, S.; Alanazi, A.M.; Bhat, M.A.; Giri, J.; Gandhi, S. Author Correction: Fabrication of microfluidic device for Aflatoxin M1 detection in milk samples with specific aptamers. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Qin, M.; Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Lu, X.; Sun, A.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. A lateral flow assay based on aptamer for the detection of AFM1 in milk samples. Food Bioscience 2025, 66, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ma, P.; Imran Mahmood, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Screening of a High-Affinity Aptamer for Aflatoxin M1 and Development of Its Colorimetric Aptasensor. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 71, 7546–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerdsri, J.; Soongsong, J.; Laolue, P.; Jakmunee, J. Reliable colorimetric aptasensor exploiting 72-Mers ssDNA and gold nanoprobes for highly sensitive detection of aflatoxin M1 in milk. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2021, 102, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wen, F.; Li, M.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Zheng, N.; Wang, J. A simple aptamer-based fluorescent assay for the detection of Aflatoxin B1 in infant rice cereal. Food Chemistry 2017, 215, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Guo, X.; Wen, F.; Chen, L.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, N.; Cheng, J.; Xue, X.; Wang, J. Aptamer-Based Fluorescence Quenching Approach for Detection of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk. 2021, Volume 9 - 2021.

- Aran, G.C.; Bayraç, C. Simultaneous Dual-Sensing Platform Based on Aptamer-Functionalized DNA Hydrogels for Visual and Fluorescence Detection of Chloramphenicol and Aflatoxin M1. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2023, 34, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Moovendaran, K.; Dhenadhayalan, N.; Lee, S.-F.; Leung, M.-K.; Sankar, R. From food toxins to biomarkers: Multiplexed detection of aflatoxin B1 and aflatoxin M1 in milk and human serum using PEGylated ternary transition metal sulfides. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2023, 5, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Guo, G.; Fu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, T.; Li, T. A fluorescent aptasensor based on functional graphene oxide and FRET strategy simultaneously detects aflatoxins B1 and aflatoxins M1. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2024, 52, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, R.; Liu, L.; Hou, B.; Cui, H.; Yun, K.; Wei, Z.; et al. A label-free fluorescent aptasensor for AFB1 and AFM1 based on the aptamer tailoring strategy and synergistic signal amplification of HCR and MoS2 nanosheets. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2025, 434, 137591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, I.; Alanazi, S.J.F.; Hayat, A.; Jubeen, F. Covalent organic framework-based aptananozyme (COF@NH2 apt-AFM1): A novel platform for colorimetric and fluorescent aptasensing of AFM1 in milk. Food Chemistry 2025, 484, 144478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordasht, H.K.; Hasanzadeh, M. Specific monitoring of aflatoxin M1 in real samples using aptamer binding to DNFS based on turn-on method: A novel biosensor. Journal of Molecular Recognition 2020, 33, e2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamami, M.; Mars, A.; Raouafi, N. Biosensor based on antifouling PEG/Gold nanoparticles composite for sensitive detection of aflatoxin M1 in milk. Microchemical Journal 2021, 165, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, H.R.; Adabi, M.; Bagheri, K.P.; Karim, G. Development of electrochemical aptasensor based on gold nanoparticles and electrospun carbon nanofibers for the detection of aflatoxin M1 in milk. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2021, 15, 1826–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, L.; Yufang, L.; Zhao, A.; Jia, R.; Wang, B.; Song, Y. A novel electrochemical aptasensor based on layer-by-layer assembly of DNA-Au@Ag conjugates for rapid detection of aflatoxin M1 in milk samples. Journal of Dairy Science 2022, 105, 1966–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, S.F.; Hojjatoleslamy, M.; Kiani, H.; Molavi, H. Monitoring of Aflatoxin M1 in milk using a novel electrochemicalaptasensorbased on reduced graphene oxide and gold nanoparticles. Food Chemistry 2022, 373, 131321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Du, C.; Guo, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Ma, L. Ratiometric electrochemical aptasensor based on split aptamer and Au-rGO for detection of aflatoxin M1. Journal of Dairy Science 2024, 107, 2748–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, J. Molecular imprinting: perspectives and applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 2137–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Hui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; He, C.; Zhao, A.; Wei, L.; Wang, B. Novel dual-recognition electrochemical biosensor for the sensitive detection of AFM1 in milk. Food Chemistry 2024, 433, 137362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huma, Z.-E.; Nazli, Z.-I.H.; Gokce, G.; Ali, M.; Jubeen, F.; Hayat, A. A novel and universal dual-functionalized Hazo-POPs@COOH-apt/PGE-based electrochemical biosensor for detection of aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) in raw milk sample: A versatile peroxidase-mimicking aptananozyme approach. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2025, 341, 130887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.-J.; Wang, K.; Liang, W.-B.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. Covalent organic frameworks as micro-reactors: confinement-enhanced electrochemiluminescence. Chemical Science 2020, 11, 5410–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Asumadu, P.; Zhou, S.; Wang, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, J.; Guan, H.; Ye, H. Recognition mechanism of split T-2 toxin aptamer coupled with reliable dual-mode detection in peanut and beer. Food Bioscience 2024, 60, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Li, H.; Zareef, M.; Khan, I.M.; Iqbal, M.W.; Niazi, S.; Raza, H.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Q. Recent Advances in Food Safety Detection: Split Aptamer-Based Biosensors Development and Potential Applications. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2025, 73, 4397–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).