Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

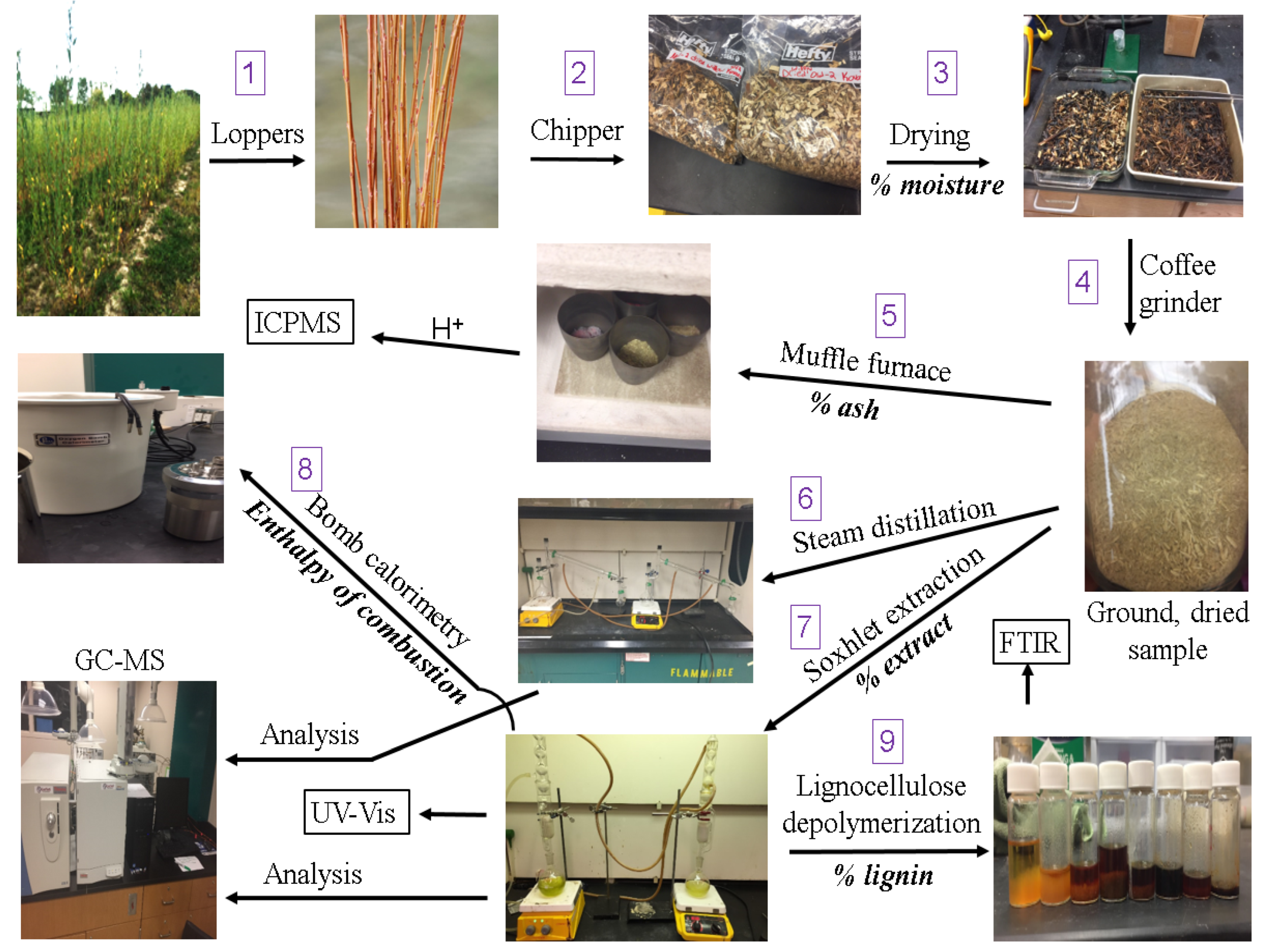

Materials and Methods

Harvesting and Drying

Ash Determination

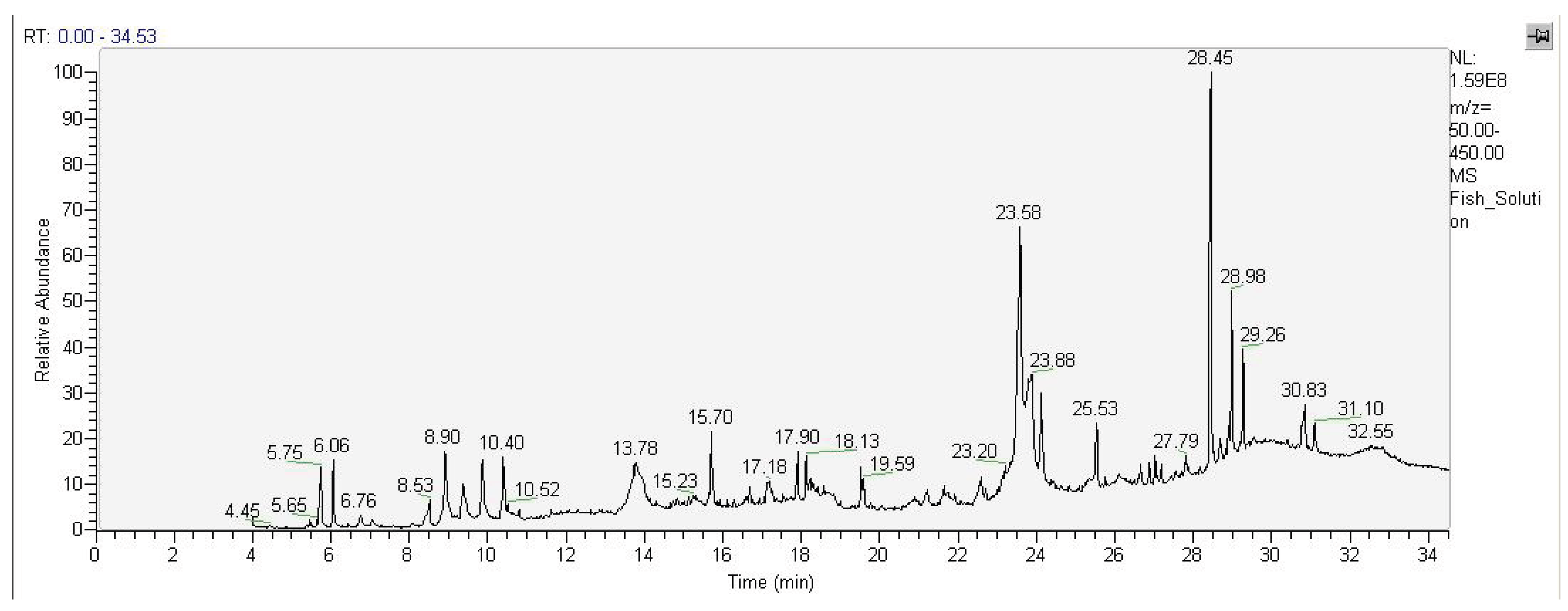

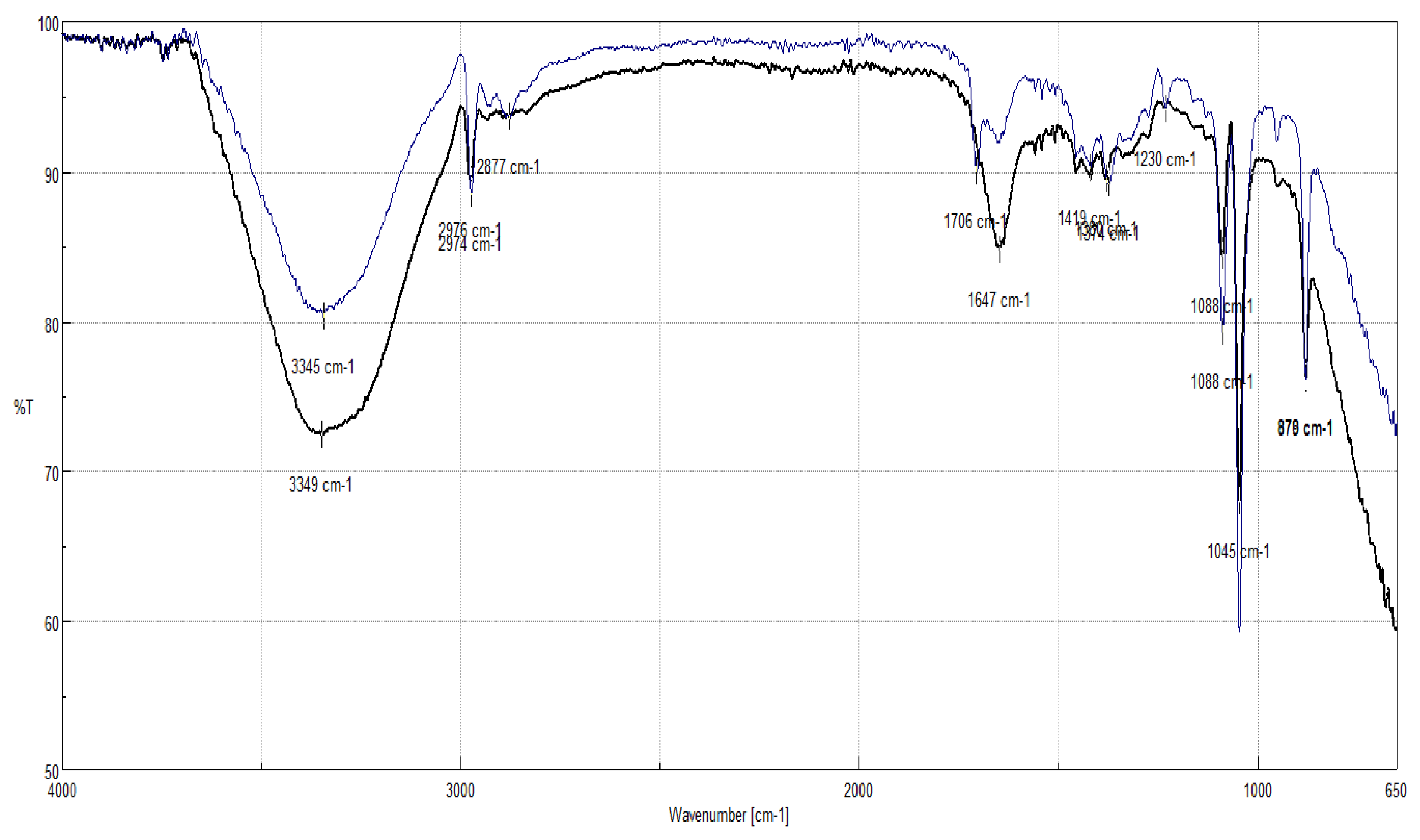

Organic Extractions

Bomb Calorimetry

Delignification

Results

Moisture Determination

Ash Determination

Extraction

Enthalpy of Combustion

Delignification

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Associated Content

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy: 67th Edition; 2018.

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy: 68th Edition; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea. PLoS One 2014, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Flórez, J.M.; Bassi, A.; Thompson, M.R. Microbial Degradation and Deterioration of Polyethylene - A Review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, H.; Hollman, P.C.H.; Peters, R.J.B. Potential Health Impact of Environmentally Released Micro- and Nanoplastics in the Human Food Production Chain: Experiences from Nanotoxicology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 8932–8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P.N.; Palmer, M.R. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Concentrations over the Past 60 Million Years. Nature 2000, 406, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafts-Brandner, S.J.; Salvucci, M.E. Rubisco Activase Constrains the Photosynthetic Potential of Leaves at High Temperature and CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 13430–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, J.; Sato, M.; Ruedy, R.; Lo, K.; Lea, D.W.; Medina-Elizade, M. Global Temperature Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 14288–14293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vos, J.M.; Joppa, L.N.; Gittleman, J.L.; Stephens, P.R.; Pimm, S.L. Estimating the Normal Background Rate of Species Extinction. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 29, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.D.; Cameron, A.; Green, R.E.; Bakkenes, M.; Beaumont, L.J.; Collingham, Y.C.; Erasmus, B.F.N.; Ferreira De Siqueira, M.; Grainger, A.; Hannah, L.; Hughes, L.; Huntley, B.; Van Jaarsveld, A.S.; Midgley, G.F.; Miles, L.; Ortega-Huerta, M.A.; Peterson, A.T.; Phillips, O.L.; Williams, S.E. Extinction Risk from Climate Change. Nature 2004, 427, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Fahriye Enda, T.; Karaosmanoglu, F. Supply Chain Network Carbon Footprint of Forest Biomass to Biorefinery. J. Sustain. For. 2021, 40, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CELLULOSE – FUNDAMENTAL ASPECTS.; Godbout, L., Ven, T. van de, Eds.; InTech, 2013.

- Zakzeski, J.; Bruijnincx, P. C. A.; Jongerius, A. L.; Weckhuysen, B. M. The Catalytic Valorization of Lignin for the Production of Renewable Chemicals. Chemical Reviews. 2010, pp 3552–3599. [CrossRef]

- Werpy, T.; Petersen, G. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass Volume I – Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas; 2004. [CrossRef]

- Bechthold, I.; Bretz, K.; Kabasci, S.; Kopitzky, R.; Springer, A. Succinic Acid: A New Platform Chemical for Biobased Polymers from Renewable Resources. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2008, 31, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascal, M.; Nikitin, E.B. Direct, High-Yield Conversion of Cellulose into Biofuel. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 7924–7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragauskas, A.J.; Nagy, M.; Kim, D.H.; Eckert, C.A.; Hallett, J.P.; Liotta, C.L. From Wood to Fuels. Ind. Biotechnol. 2006, 2, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Cao, H.; Song, A.; Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, X. A High-Performance and Environment-Friendly Gel Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium Ion Battery Based on Composited Lignin Membrane. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2018, 22, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoine, N.; Desloges, I.; Dufresne, A.; Bras, J. Microfibrillated Cellulose - Its Barrier Properties and Applications in Cellulosic Materials: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, S.; Prado, R.; Kuzmina, O.; Potter, K.; Bhardwaj, J.; Wanasekara, N.D.; Harniman, R.L.; Koutsomitopoulou, A.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Welton, T.; Rahatekar, S.S. Regenerated Cellulose and Willow Lignin Blends as Potential Renewable Precursors for Carbon Fibers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5903–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, B.; Babcock, M. Ash Related Issues in Biomass Combustion. In ThermalNet workshop; 2006; p 169.

- Liska, A.J.; Yang, H.S.; Bremer, V.R.; Klopfenstein, T.J.; Walters, D.T.; Erickson, G.E.; Cassman, K.G. Improvements in Life Cycle Energy Efficiency and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Corn-Ethanol. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger Notes. 2018 world hunger and poverty facts and statistics https://www.worldhunger.org/world-hunger-and-poverty-facts-and-statistics/ (accessed Sep 7, 2020).

- Hytönen, J. Effect of Fertilizer Treatment on the Biomass Production and Nutrient Uptake of Short-Rotation Willow on Cut-Away Peatlands. Silva Fennica. 1995, pp 21–40. [CrossRef]

- 2016 Agricultural Chemical Use Survey: Corn; 2017.

- Yang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Land and Water Requirements of Biofuel and Implications for Food Supply and the Environment in China. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.C.; Keoleian, G.A.; Volk, T.A. Life Cycle Assessment of a Willow Bioenergy Cropping System. Biomass and Bioenergy 2003, 25, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer-Benlliure, V.; Moya, R.; Gaitán-Alvarez, J. Physical and Energy Characteristics, Compression Strength, and Chemical Modification of Charcoal Produced from Sixteen Tropical Woods in Costa Rica. J. Sustain. For. 2021, 00, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford-Robertson, J.B.; Mitchell, C.P.; Watters, M.P. Short Rotation Coppice Energy Plantations: Technology and Economics. J. Sustain. For. 1994, 1, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perttu, K.L. Biomass Production and Nutrient Removal from Municipal Wastes Using Willow Vegetation Filters. J. Sustain. For. 1994, 1, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennerby-Forsse, L.; Melin, J.; Rosen, K.; Siren, G. Uptake and Distribution of Radiocesium in Fast-Growing Salix Viminalis L. J. Sustain. For. 1994, 1, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirck, J.; Isebrands, J.G.; Verwijst, T.; Ledin, S. Development of Short-Rotation Willow Coppice Systems for Environmental Purposes in Sweden. Biomass and Bioenergy 2005, 28, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola-Yudego, B.; Aronsson, P. Yield Models for Commercial Willow Biomass Plantations in Sweden. Biomass and Bioenergy 2008, 32, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, T.A.; Abrahamson, L.P.; Nowak, C.A.; Smart, L.B.; Tharakan, P.J.; White, E.H. The Development of Short-Rotation Willow in the Northeastern United States for Bioenergy and Bioproducts, Agroforestry and Phytoremediation. Biomass and Bioenergy 2006, 30, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willow plant cuttings for sale https://doubleavineyards.com/willow-cuttings-for-sale.

- Wang, Z.; MacFarlane, D.W. Evaluating the Biomass Production of Coppiced Willow and Poplar Clones in Michigan, USA, over Multiple Rotations and Different Growing Conditions. Biomass and Bioenergy 2012, 46, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerper, G.J.; Richardson, C.J. Biomass and Net Annual Primary Production Regressions for Populus Grandidentata on Three Sites in Northern Lower Michigan. Can J. FOR. RES. 1980, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.A.; Nordman, E. Analyzing Survival, Growth, and Environmental Effects of Willow Biomass Energy Crops at GVSU. ScholarWorks@GVSU.

- Dou, J.; Xu, W.; Koivisto, J.J.; Mobley, J.K.; Padmakshan, D.; Kögler, M.; Xu, C.; Willför, S.; Ralph, J.; Vuorinen, T. Characteristics of Hot Water Extracts from the Bark of Cultivated Willow (Salix Sp.). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5566–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Galvis, L.; Holopainen-Mantila, U.; Reza, M.; Tamminen, T.; Vuorinen, T. Morphology and Overall Chemical Characterization of Willow (Salix Sp.) Inner Bark and Wood: Toward Controlled Deconstruction of Willow Biomass. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering. 2016, pp 3871–3876. [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Kim, H.; Li, Y.; Padmakshan, D.; Yue, F.; Ralph, J.; Vuorinen, T. Structural Characterization of Lignins from Willow Bark and Wood. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7294–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.R.; Hopke, P.K.; Rector, L.; Allen, G.; Lin, L. Chemical Composition of Wood Chips and Wood Pellets. Energy and Fuels. 2012, pp 4932–4937. [CrossRef]

- Brauns, F.E. The Isolation and Methylation of Native Lignin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1939, 61, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.B.; Jensen, A.; Schandel, C.B.; Felby, C.; Jensen, A.D. Solvent Consumption in Non-Catalytic Alcohol Solvolysis of Biorefinery Lignin. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxted, A.P.; Black, C.R.; West, H.M.; Crout, N.M.J.; Mcgrath, S.P.; Young, S.D. Phytoextraction of Cadmium and Zinc by Salix from Soil Historically Amended with Sewage Sludge. Plant Soil 2007, 290, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, J.; Vervaeke, P.; Meers, E.; Tack, F.M.G. Seasonal Changes of Metals in Willow (Salix Sp.) Stands for Phytoremediation on Dredged Sediment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 1962–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69: Water https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7732185&Type=IR-SPEC&Index=1 (accessed Jun 2, 2020).

- Jerković, I.; Marijanović, Z.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Bubalo, D.; Kezić, N. Molecular Diversity of Volatile Compounds in Rare Willow (Salix Spp.) Honeydew Honey: Identification of Chemical Biomarkers. Mol. Divers. 2010, 14, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capello, C.; Fischer, U.; Hungerbühler, K. What Is a Green Solvent? A Comprehensive Framework for the Environmental Assessment of Solvents. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 927–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarska-Bialokoz, M.; Kaczor, A.A. Computational Analysis of Chlorophyll Structure and UV-Vis Spectra: A Student Research Project on the Spectroscopy of Natural Complexes. Spectrosc. Lett. 2014, 47, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jr., M.J.; Fleming, S.A. Organic Chemistry; Fifth, Ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, New York, 2014.

- Boeriu, C.G.; Bravo, D.; Gosselink, R.J.A.; Van Dam, J.E.G. Characterisation of Structure-Dependent Functional Properties of Lignin with Infrared Spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 20, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.H. Phenol Tautomerism. Q. Rev. Chem. Soc. 1956, 10, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2016 Agricultural Chemical Use Survey - Corn; 2017.

- USDA. Feedgrains sector at a glance https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/corn-and-other-feedgrains/feedgrains-sector-at-a-glance/ (accessed May 31, 2020).

- Musick, J.T.; Dusek, D.A. Irrigated Corn Yield Response To Water. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1980, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.A.; Yazar, A.; Schneider, A.D.; Dusek, D.A.; Copeland, K.S. Yield and Water Use Efficiency of Corn in Response to LEPA Irrigation. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1995, 38, 1737–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubako, S.; Lant, C. Water Resource Requirements of Corn-Based Ethanol. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, G.E.; Liener, I.E.; Evans, S.D.; Frazier, R.D.; Nelson, W.W. Yield and Composition of Soybean Seed as Affected by N and S Fertilization. Agron. J. 1975, 67, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frédette, C.; Grebenshchykova, Z.; Comeau, Y.; Brisson, J. Evapotranspiration of a Willow Cultivar (Salix Miyabeana SX67) Grown in a Full-Scale Treatment Wetland. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 127, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirck, J.; Volk, T.A. Seasonal Sap Flow of Four Salix Varieties Growing on the Solvay Wastebeds in Syracuse, NY, USA. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2009, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.; Ludwig, C.; Davoli, F.; Wochele, J. Thermal Treatment of Metal-Enriched Biomass Produced from Heavy Metal Phytoextraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 3359–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telmo, C.; Lousada, J. Heating Values of Wood Pellets from Different Species. Biomass and Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2634–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant feedstock | Water requirements () | Fertilizer requirements( | Dry crop yield ( |

| Corn | 3433,5-8804 | 3381 | ~29003,2 – 11,8004 |

| Soybeans | 7335 | 59-3217 | 17201-85006 |

| Willow (lignocellulosic) | 4949–39548 | 1007 | 77007 |

| Wood sample | % moisture (from total biomass) | % Ash (from dehydrated samples) |

|---|---|---|

| W |

50.06 ± 0.71 |

2.862 ± 0.037 |

| M | 19.76 ± 0.26 | 2.44 ± 0.27 |

| Fishcreek | 43.6 ± 1.6 42.31 | 1.51 ± 0.24 |

| Fabius | 52.2 ± 2.0 53.61 | 2.39 ± 0.37 |

| SX-64 | 50. ± 2.2 50.41 | 2.53 ± 0.67 |

| Millbrook | 51.6 ± 1.2 51.11 | 2.72 ± 0.53 |

| Data source | Copper (ppm) | Lead (ppm) | Cadmium (ppm) | Zinc (ppm) |

| Keller et al.[64] (ox. conditions) | 171 | - | 2 | 7293 |

| Fiskcreek | 2300 | 18 | 2.3 | 7500 |

| Willow variety | Proportion of extractable mass (%) |

|---|---|

| Fishcreek (Salix purpurea) | 9.8 ± 1.1 |

| Fabius (Salix viminalis x Salix miyabeana) | 11.22 ± 0.90 |

| SX-64 (Salix miyabeana) | 12.42 ± 0.40 |

| Millbrook (Salix purpurea x Salix miyabeana) | 10.72 ± 0.70 |

| Sample | Enthalpy of combustion (kilojoules/gram) | Standard deviation (kilojoules/gram) |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetable oil | 43.4 | 0.3 |

| Fabius (Salix viminalis x Salix miyabeana) | 13.0 | 0.5 |

| SX64 (Salix miyabeana) | 15.3 | 0.5 |

| Millbrook (Salix purpurea x Salix miyabeana) | 17.6 | 0.3 |

| Fishcreek (Salix purpurea) | 15.5 | 0.2 |

| Salix babilonica[65] | 18.279 | 0.348 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).