1. Introduction

Vanadium- and chromium-bearing hot metal is a product generated from the reduction and smelting of vanadium-extracted chromium-containing residues. Typically, its vanadium (V) content ranges from 2% to 5%, while its chromium (Cr) content ranges from 1% to 5% [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Due to the high content of V and Cr, there is still no effective way of resource utilization. The traditional separation process of V and Cr is oxidation enrichment-roasting pretreatment-wet separation. Although this process is highly industrialized, they are only applicable to low-vanadium and low-chromium hot metal (V: 0.15–0.35%, Cr: 0.2–0.6%) [

4,

5,

6]. However, the availability of relevant research and experimental data remains severely limited for high-vanadium and high-chromium hot metal (V > 2%, Cr > 1%), and the applicability of traditional processes in this context has yet to be fully validated. Furthermore, traditional processes are characterized long flowsheets, with a progressive decrease in metal recovery rates at each stage. Consequently, the overall recovery rate of vanadium and chromium from hot metal to final products typically reaches only 60–80% [

6,

7]. During converter oxidation, the high oxygen potential leads to excessive chromium oxidation (Cr

2O

3 accounts for 5–10% of the slag phase) [

8,

9,

10], significantly reducing the efficiency of chromium recovery. In roasting step, sodium roasting produces high-salt wastewater containing Na⁺ (5–10 g/L) and NH₄⁺ (2–3 g/L) [

8,

11,

12], as well as toxic wastewater containing Cr(VI) (0.5–1.2 kg/t) [

13,

14]. Calcium roasting generates by-product of CaSO

4 slag containing 12–15% sulfur [

15,

16,

17], which is difficult to utilize as a resource. Moreover, the roasting process consumes 10–15% of the slag weight in Na

2CO

3 or CaCO

3 [

18], with energy consumption reaching 200–300 kWh/t of slag [

11,

19], significantly increasing costs. Additionally, the subsequent hydrometallurgical leaching-precipitation process is time-consuming (12–16 hours), with vanadium leaching rates of only 33–85%, leaving a portion of vanadium in the slag [

16,

20]. Therefore, traditional processes exhibit significant shortcomings in terms of economic efficiency and environmental sustainability.

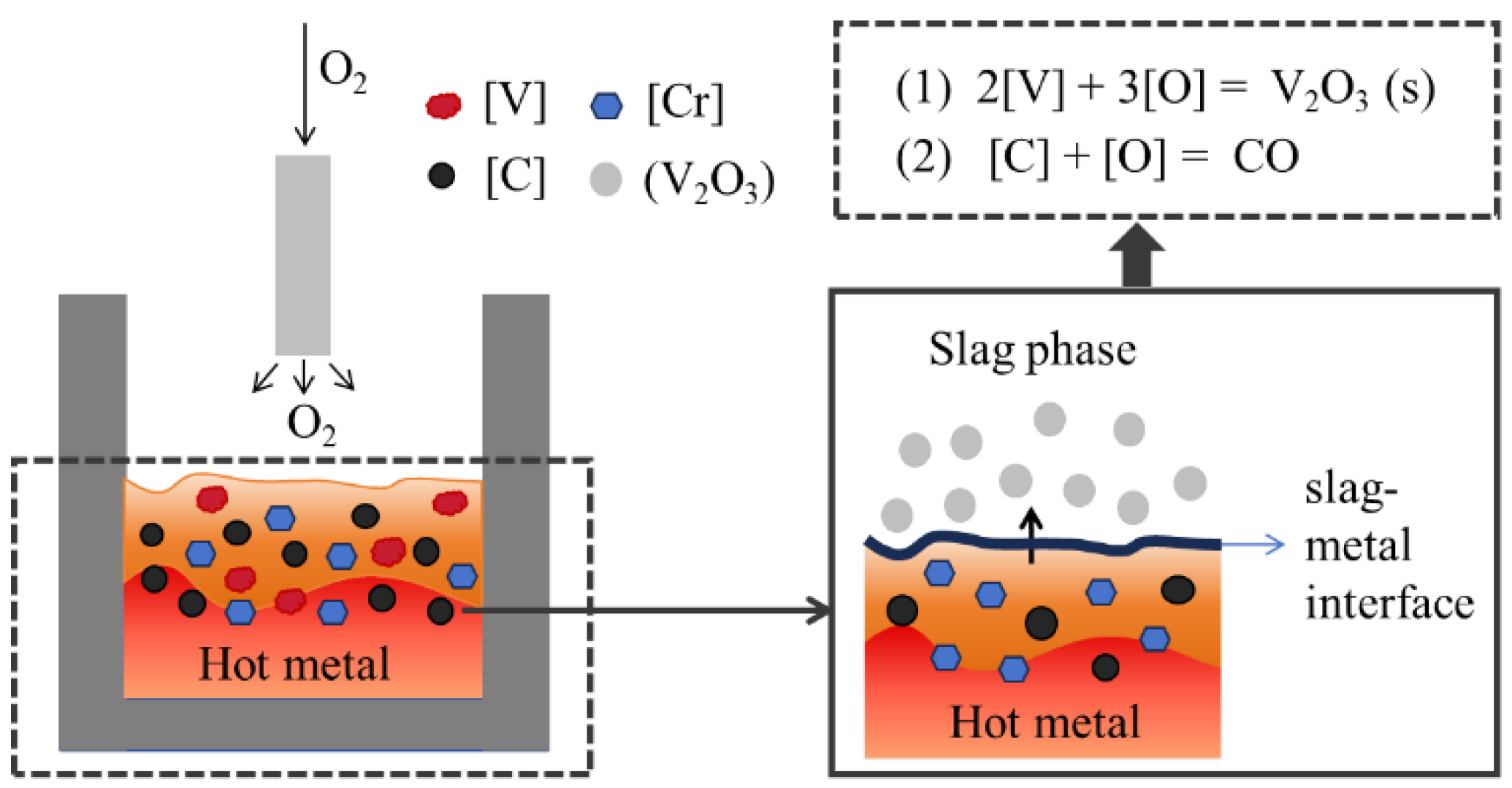

To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel and efficient method for separating vanadium and chromium based on pyrometallurgical selective oxidation. This method targets high-vanadium and high-chromium hot metal (V: 2%–5%, Cr: 1%–5%), achieving vanadium-chromium separation during the converter oxidation stage by selectively oxidizing vanadium into the slag while retaining chromium in the hot metal (as shown in

Figure 1). Thus, the subsequent roasting and wet processing processes are completely eliminated. The aim of this method is to provide a new technical path for the resource utilization of high vanadium and high chromium hot metal, and reduce the production cost, reduce the environmental pollution. To achieve these objectives, this study combines thermodynamic calculations with experimental verification. Through thermodynamic analysis, the oxidation behavior of carbon, vanadium, and chromium under different temperatures and oxygen potentials was elucidated, and the thermodynamic conditions for vanadium extraction and chromium retention were proposed. Based on these findings, high-temperature smelting experiments were designed to investigate the effects of temperature and oxygen potential on vanadium-chromium separation efficiency. The results demonstrate that this method maximizes vanadium oxidation while significantly reducing chromium oxidation. This study not only overcomes the technical bottleneck of selective oxidation in pyrometallurgical separation but also provides theoretical and practical guidance for the development of efficient and environmentally friendly metallurgical processes.

2. Thermodynamic Analysis for Oxidative Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention in Hot Metal

2.1. Optimal Temperature Control Strategy

Under standard conditions, the oxidation reactions of vanadium, chromium, and carbon in vanadium- and chromium-bearing hot metal can be described by the following reaction Equations, and their corresponding Gibbs free energy changes (

) [

21] are also list:

where

represents the standard Gibbs free energy change for reaction (i) (kJ/mol); i denotes the index of the chemical reaction, and

T is the reaction temperature (K).

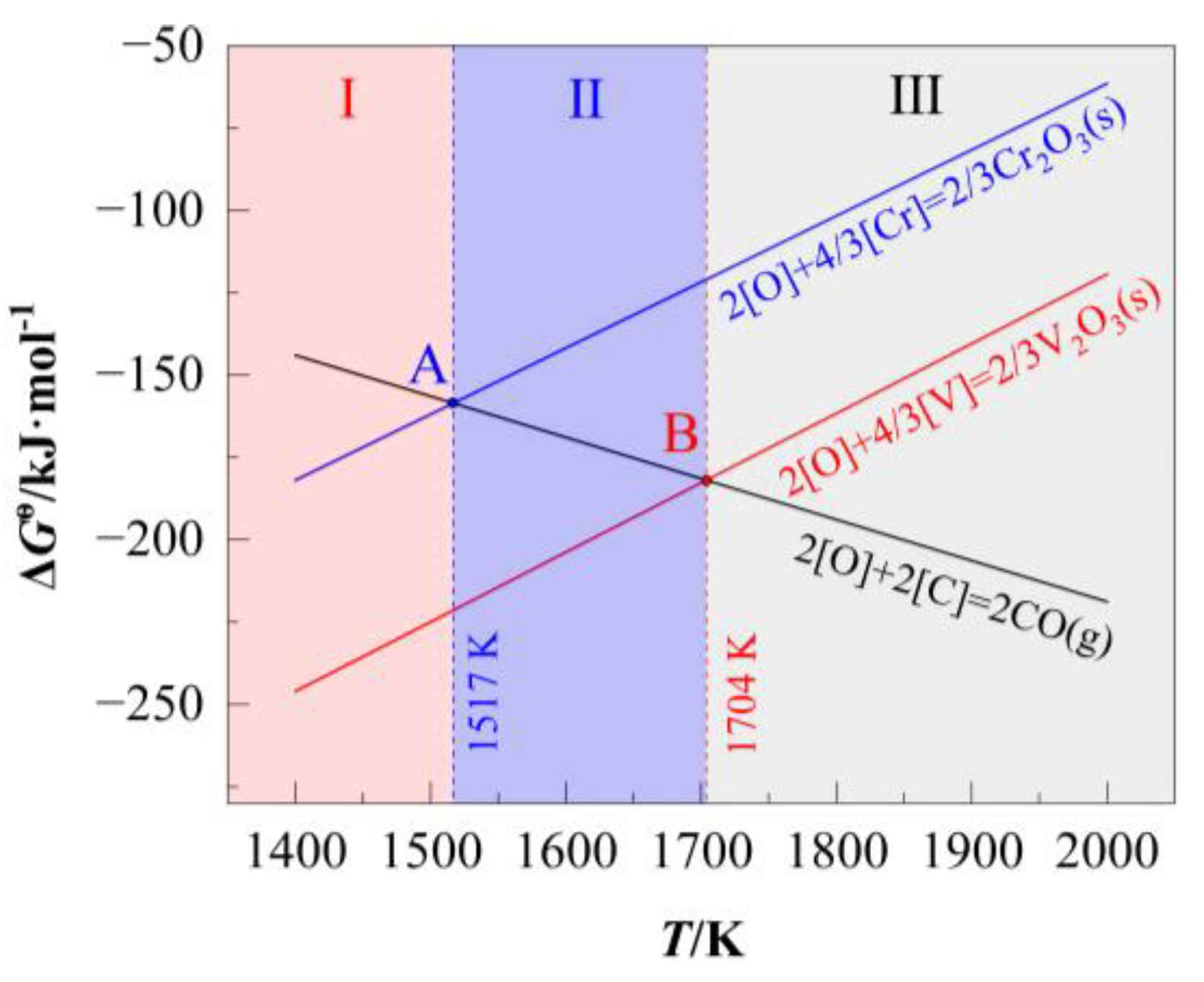

The temperature-dependent

of these reactions are plotted in

Figure 2, the oxidation curve of carbon intersects with those of chromium and vanadium at points A (1517 K) and B (1704 K), respectively. By drawing vertical lines at these intersection points parallel to the Y-axis, the temperature domain is divided into three distinct regions: I (

T < 1517 K), II (1517 K <

T < 1704 K), and III (

T > 1704 K).

Oxidation priority follows [V] > [Cr] > [C]. However, the minimal separation between vanadium and chromium oxidation curves (= 57.9–64.1 kJ/mol) leads to simultaneous oxidation of chromium during vanadium extraction, resulting in suboptimal chromium retention.

The oxidation propensity of carbon is intermediate between those of vanadium and Chromium, thereby allowing it to function as a redox mediator that promotes vanadium extraction while preserving chromium in the metallic phase. The carbon-mediated reactions involved in this process are given by Equations (4) and (5). For the system to achieve concurrent vanadium extraction and chromium retention, both reactions must proceed spontaneously in the forward direction. This dual role is essential for the selective extraction of vanadium while maintaining chromium in the metallic state.

Oxidation priority reverses to [C] > [V] > [Cr], where premature carbon oxidation depletes oxygen availability, severely limiting vanadium extraction efficiency.

While all three regimes satisfy the basic requirement of [V] > [Cr] oxidation priority, Regime II (1517–1704 K) uniquely balances vanadium extraction efficiency and chromium retention. The intermediate temperature range ensures: (1) Maximized vanadium oxidation: Dominance of over maintains thermodynamic favorability for vanadium extraction; (2) Effective chromium protection: Carbon acts as a sacrificial agent, oxidizing before chromium and reducing oxygen activity in the melt.

2.2. Oxygen Partial Pressure Control

The typical chemical composition of vanadium-chromium-containing hot metal obtained through the reduction of vanadium-extracted residues is shown in

Table 1. Specifically, the Cr, V and C content are 3.8%, 3.6%, and 4.0%, respectively, along with trace amounts of Si and Mn.

The oxygen partial pressure required to achieve the equilibrium for vanadium extraction while preserving chromium in the hot metal of this composition is calculated as follows. The reaction for oxygen dissolution in hot metal and its corresponding Gibbs free energy change is expressed as:

By linearly combining Equations (1) and (2) with Equation (6), the following equilibrium reactions and their Gibbs free energy changes are obtained:

Considering only the interaction of C, V and Cr, the interaction coefficients of C-Cr, Cr-Cr, C-V and V-V are as shown in

Table 2.

Based on the isothermal Equations (7) and (8), the oxygen partial pressure in equilibrium with the mass fractions

ω[V] and

ω[Cr] in the hot metal can be obtained:

In Equations (9) and (10),

and

represent the activities of V

2O

3 and Cr

2O

3 in the slag, respectively. lg

denotes the equilibrium oxygen partial pressure, while

ω[C],

ω[V], and

ω[Cr] correspond to the mass fractions of [C], [V], and [Cr], respectively.

Assuming

= 1 and

= 1, the following equations are obtained when

:

By taking

as the vertical axis and

ω[Cr] and

ω[V] as the horizontal axes, Equations (11) and (12) are plotted in

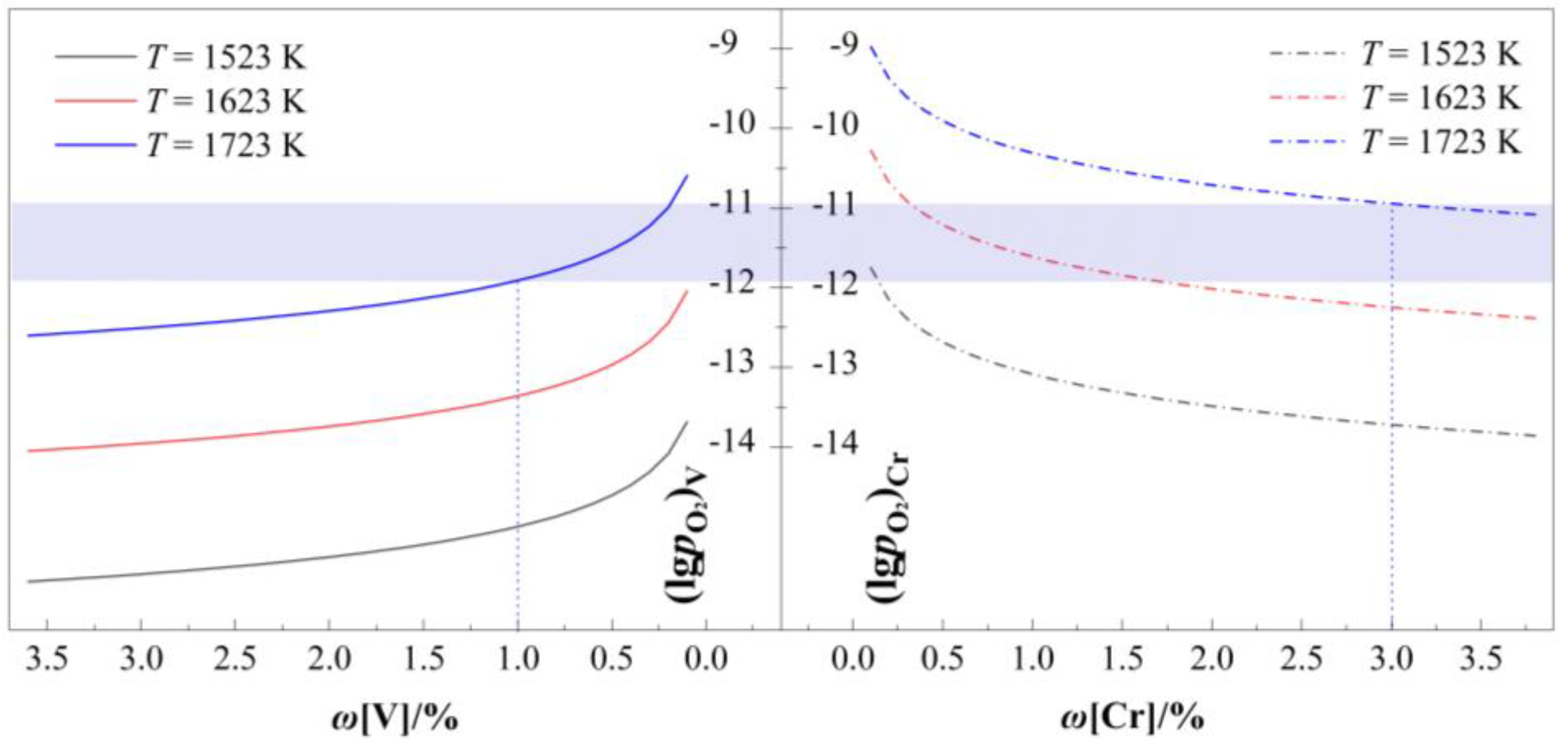

Figure 3.

As demonstrated in

Figure 3, the equilibrium oxygen partial pressures for vanadium oxidation(

V) and chromium oxidation (

Cr) exhibit distinct dependencies on their respective solute concentrations (

ω[V] and

ω[Cr]) in the melt. Both

V and

Cr increase monotonically with decreasing

ω[V] and

ω[Cr], respectively. Notably, the rate of increase diverges significantly across concentration regimes: (1) At high solute concentrations (

ω[V] > 1.0% and

ω[Cr] > 1.0%), the oxygen partial pressures show gradual variations with composition; (2) Below the critical threshold of ω[V] < 1.0% or ω[Cr] < 1.0%, both

V and

Cr escalate rapidly, indicating enhanced thermodynamic driving forces for oxidation at dilute concentrations.

Importantly, a consistent hierarchy of oxygen partial pressure is observed across all temperatures: V <Cr. This thermodynamic hierarchy establishes an optimal oxygen partial pressure window (V < lg<Cr) for selective oxidation processes. Within this window, vanadium extraction can be prioritized while suppressing chromium loss, as exemplified by the 1723 K system: (1) The lower upper bound (lg > −11.91) ensures sufficient vanadium oxidation when ω[V] < 1.0%; (2) The upper bound ( < −10.94) prevents chromium oxidation for ω[Cr] > 3.0%. Selecting 3.0% as the lower limit ensures that the oxygen partial pressure window remains sufficiently wide for experimental control; (3) The resultant operational window of −11.91< < −10.94 demonstrates the feasibility of achieving concurrent vanadium extraction and chromium preservation through precise oxygen potential control.

In practical experiments, the oxygen partial pressure could be controlled by adjusting the CO-CO2 gas ratio in the furnace atmosphere, or FeO content in slag.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Raw Materials

The initial melt was prepared using blast furnace (BF) powder, Ferrovanadium-50 (FeV50) and high carbon Ferrochrome (HC FeCr), all supplied by Shanxi Taisteel Stainless Steel co., LTD.

Table 3 summarizes the chemical compositions of these materials. The initial slag consisted of reagent-grade FeO, CaO, and SiO

2 powders (purity > 99%).

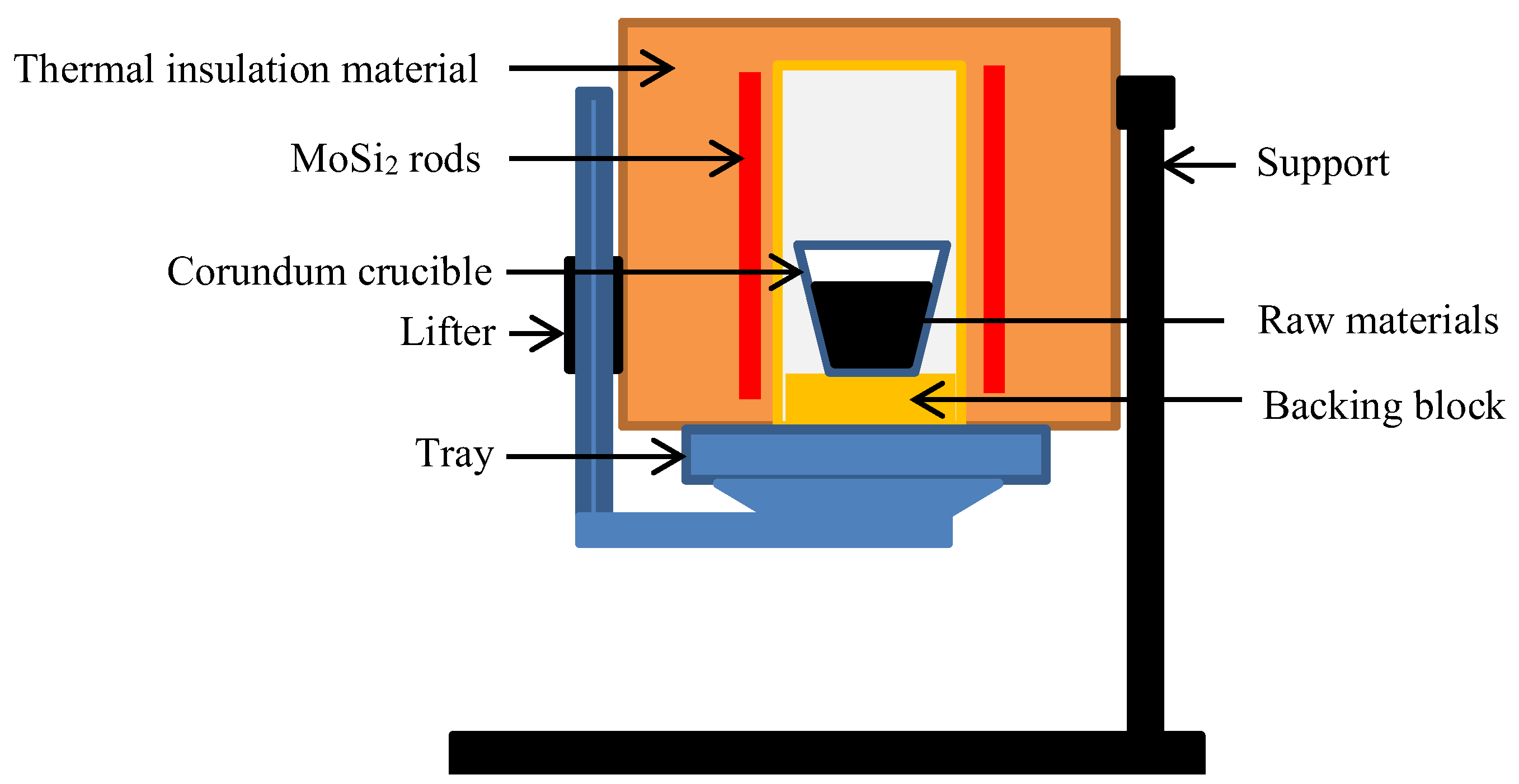

3.2. Experimental Apparatus

Experiments were conducted in a molybdenum-lined muffle resistance furnace (Model BFS-16, Beijing Fiame Temperature Technology Co., Ltd.) equipped with MoSi

2 heating elements. The furnace operates up to 1873 K with a temperature control accuracy of ±5 K (

Figure 4).

3.3. Experimental Design

As discussed in

Section 2.1, the optimal temperature range for vanadium extraction while preserving chromium under standard conditions is 1517–1704 K. However, the temperatures corresponding to points A and B in

Figure 1 are typically higher than those under standard conditions due to the influence of the hot metal composition. In order to ensure effective slag-metal separation during the experiments, the temperature range was set with a lower limit of 1633 K, an upper limit of 1753 K, and an interval of 30 K.

In this paper, FeO was selected as the oxidizing agent. The required amount of FeO consists of two components: one for oxidizing Si, Mn, and V, and the other is additional component for maintaining the oxygen potential equilibrium necessary to balance residual V and Cr. Based on calculations, for 100 g of hot metal, the theoretical FeO consumption for oxidizing Si, Mn, and V is 10.9 g. The FeO required to maintain the equilibrium for residual V and Cr is determined through the following calculations.

The relationship between the solubility of oxygen in hot metal and temperature is expressed as:

where

α(FeO) is the activitie of FeO in the slag.

ω[O] can be derived from the equilibrium constant for the dissolution of O

2 in hot metal as shown in Equation (6). The equilibrium constant

K6 is expressed as:

Since the dissolved oxygen in hot metal can be considered a dilute solution of [O],

α[O] =

ω[O]. Substituting Equations (6) and (14) into Equation (13) yields:

Substituting Equation (15) into Equation (13):

At a temperature of 1723 K and an oxygen partial pressure lg

ranging from −11.91 atm to −10.94 atm (calculated in

Section 2.2),

α(FeO) is determined to between 0.048 and 0.147 according to Equation (16). For simplicity, the final slag was assumed to behave as an ideal solution, where

α(FeO) is equal to its mole fraction. The final slag consists of CaO, SiO

2, FeO, V

2O

3, and MnO with their molar quantities denoted as

n(CaO),

n(SiO

2),

n(FeO),

n(V

2O

3), and

n(MnO) respectively. Thus,

α(FeO) can be expressed as:

Considering 100 g sample of vanadium-chromium-containing hot metal and 40 g of initial slag with a fixed basicity of (R2: ω(CaO)/ω(SiO2)) 1.8, n(FeO) is calculated via Equation (17) to span from 0.026 mol and 0.086 mol, corresponding to an FeO mass of approximately 2.23 g to 8.95 g, corresponding to ω(FeO) in final slag is 5.6−17.0%. Incorporating the FeO consumed during oxidation reactions, the total FeO requirement is estimated to be between 13.13 g and 19.85 g.

In this paper, a two-stage single-factor experimental design was adopted to systematically analyze the effects of temperature and FeO content on vanadium-chromium separation: (1) Temperature gradient experiment (Heat No. 1–5): Fitting ω(FeO) in final slag is 10.0%. Systematically varied temperature from 1633 K to 1753 K in 30 K intervals. This design isolates temperature as the sole variable to determine the thermal window for optimal vanadium oxidation and chromium retention; (2) FeO content gradient experiment (Heat No. 6–9): Fixed temperature at the optimal value identified in stage 1 (1723 K) and systematically varied ω(FeO) in final slag is 3.0-20.0%。This stage focuses on optimizing FeO dosage to achieve the desired oxygen potential for selective oxidation. Each group of experiments was conducted three times.

The experimental plan was designed as shown in

Table 4. CaO and SiO

2 were added to improve fluidity of the resultant slag. To reduce interactions with the corundum crucible, the slag’s basicity was set at 1.8. This promotes a protective layer of 2CaO·SiO

2 at the interface, minimizing Al

2O

3 dissolution [

23,

24]. The hot metal mass was fixed at 100 g, with its composition detailed in

Table 1.

3.4. Experimental Procedure

All raw materials were thoroughly mixed and loaded into a corundum crucible. Once the furnace reached the predetermined experimental temperature, the crucible containing the sample was placed into the furnace, and the timing was started. After holding at the target temperature for 1 hour, the crucible was removed and cooled to room temperature. Then the crucible walls were visually inspected after the experiment and showed no significant signs of corrosion or slag penetration. The crucible was then carefully broken using a chisel. A clear interface between the metal phase (bottom) and slag phase (top) was observed in all samples, confirming effective phase separation. Representative samples were collected separately from the metal and slag phases for subsequent chemical and microstructural analysis.

3.5. Calculation Methods

The oxidation rate

ηM, representing the percentage of vanadium, chromium, and carbon oxidized, was calculated using the following formula:

where

ω[M]

0 is the initial mass fraction of the element in the hot metal (%), and

ω[M] is the mass fraction in the hot metal after oxidation (%), with

ω[V] set below 1%, that is,

ηV > 72.22%.

In order to achieve the goal of maximizing vanadium oxidation (

ηV) while minimizing chromium oxidation (

ηCr) in hot metal, this paper introduces the vanadium-chromium separation index (

SIV-Cr) to quantify the degree of separation between vanadium and chromium. The calculation formula for

SIV-Cr is provided in Equation (19):

where

ηV represents the extent of vanadium oxidation, and (1

ηCr) reflects the degree of chromium retention. As a composite index,

SIV-Cr evaluates the separation performance of vanadium and chromium through a geometric mean approach, emphasizing the simultaneous optimization of vanadium extraction and chromium retention. Specifically, a high

SIV-Cr value indicates effective separation, characterized by high vanadium oxidation and low chromium oxidation. Conversely, a low

SIV-Cr value suggests poor separation, with either low vanadium oxidation or high chromium oxidation.

The slag-metal distribution ratios of vanadium (

LV) and chromium (

LCr) were calculated using the following equations:

where

ω(V

2O

3) and

ω(Cr

2O

3) are the mass fractions of V

2O

3 and Cr

2O

3 in the slag (%), respectively.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Effect of Temperature on Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention

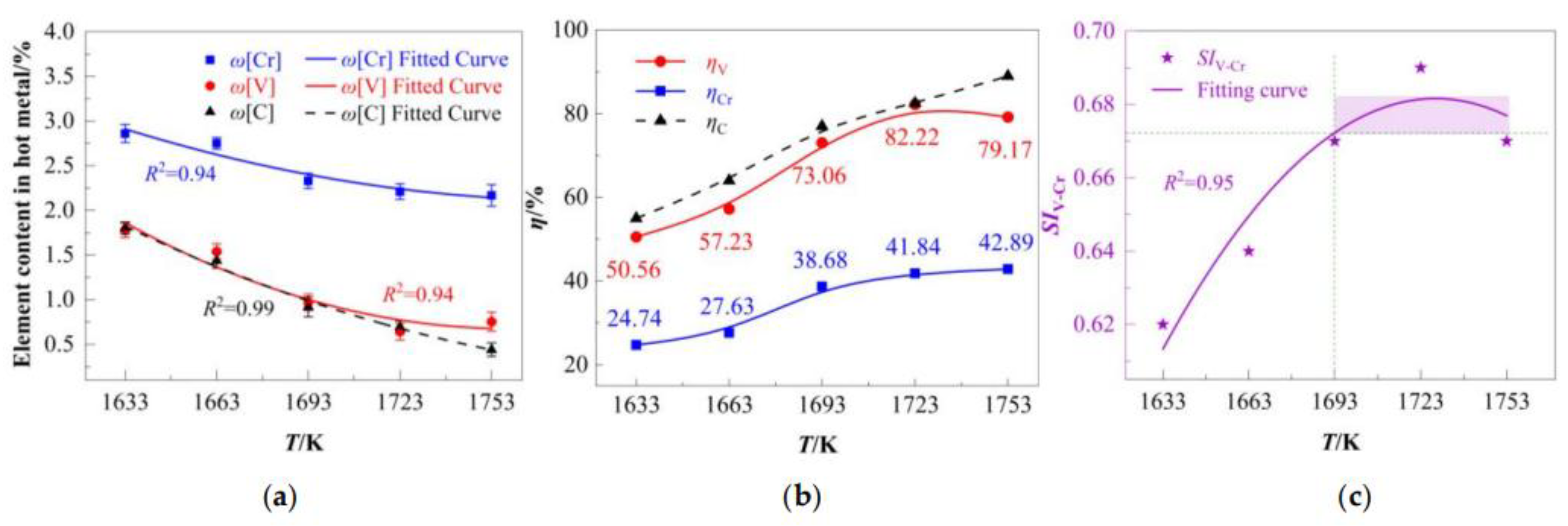

4.1.1. Temperature-Dependent Oxidation and Separation of [V] and [Cr] in Hot Metal

The oxidation behavior of [V], [Cr], and [C] in hot metal was systematically investigated under a fixed ω(FeO) (10%) in final slag. The individual contents of carbon, vanadium, and chromium were fitted with temperature, as shown in Equations (22)–(24) and

Figure 5a. While all three elements decrease in content as temperature rises, the behavior of vanadium diverges from that of chromium and carbon above 1693 K, where its rate of decline attenuates. This divergence may be attributed to carbon’s relatively higher susceptibility to oxidation compared to vanadium at high temperatures. The determined operational window for achieving ω[V] ≤ 1%, as derived from Equation (23) and the experimental data, is 1693 K to 1753 K. Beyond this range, the vanadium content increases, confirming that these extreme temperatures inhibit effective vanadium oxidation.

Figure 5b illustrates the temperature-dependent oxidation rates (

ηV,

ηCr and

ηC).

ηC demonstrates the steepest positive correlation, rising linearly from 55% to 89% across the temperature range.

ηV peaked at 82.2% at 1723 K (the optimal temperature for vanadium extraction), while

ηCr increases monotonically from 24.74% (1633 K) to 42.89% (1753 K), exhibiting near-linear progression above 1693 K. Across the entire temperature range,

ηV consistently exceeded

ηCr, with a steeper increase in

ηV (55.56% to 82.22%) compared to

ηCr (24.74% to 42.89%). This divergence stems from two factors: thermodynamic preference (

Section 2.1) and the mediating role of carbon (detailed in

Section 4.1.2).

Below 1723 K,

ηV and

ηC followed similar trends; however, above 1723 K,

ηC surpassed

ηV (

Figure 5b). This inversion reflects intensified competition between [C] and [V] for oxygen at elevated temperatures [

25,

26].

The separation efficiency of [V] and [Cr], quantified by

SIV-Cr, as shown in

Figure 5c. The fitting curve exhibits an upward convex characteristic and attains its peak at approximately 1723 K. The initial increase in

SIV-Cr was driven by the rapid rise in

ηV (50.56% to 82.22%), while

ηCr increased modestly (24.74% to 41.84%). Beyond 1723 K,

SIV-Cr declined slightly primarily due to the reduction in

ηV (82.22% to 79.17%) and marginal

ηCr increase (41.84% to 42.89%). According to the quadratic fitting relationship:

Within the temperature range of 1693 K ≤ T ≤ 1753 K,

SIV-Cr can be maintained within the range of 0.67 to 0.69. These results underscore the adverse effects of excessive temperatures on vanadium oxidation selectivity, thereby reducing the separation efficiency.

The optimal process window was determined as 1693–1753 K, where SIV-Cr exceeded 0.67, ηV remained above 73.06%, and ηCr was suppressed below 42.89%. At same time, ω[V] was reduced to <0.97%, while ω[Cr] remained >2.17%. These results indicate that effective separation of vanadium and chromium in hot metal has been achieved under the specified conditions.

It should be noted that the discussion on the influence of temperature in this section is based on the condition of a fixed ω(FeO) (10%). The boundaries of this optimal temperature window (1693–1753 K) are essentially the result of the competition between the thermodynamics of V and Cr oxidations in this specific oxygen potential. It can be predicted that when the initial oxygen potential (such as FeO content) changes, the oxidation behavior of carbon and the oxidation competition between V and Cr will also change accordingly, leading to a shift in the optimal temperature range. For example, at a higher FeO dosage, to avoid excessive oxidation of Cr, the upper limit of the optimal temperature may need to be appropriately reduced.

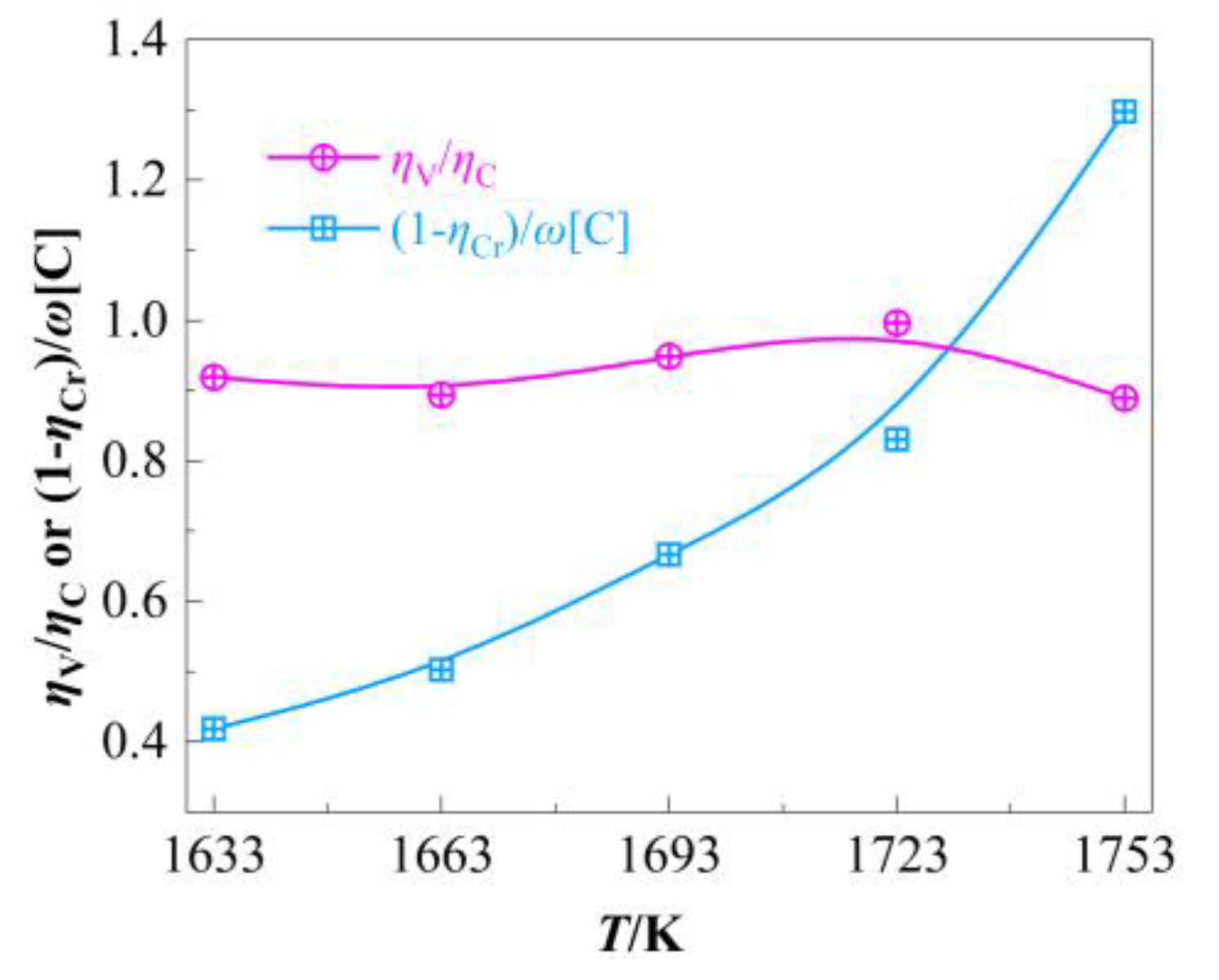

4.1.2. Carbon-Mediated Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention

To systematically assess the role of carbon as a medium for vanadium extraction and chromium protection, we introduced two empirical indices: the vanadium extraction efficiency per unit carbon oxidation rate (

ηV/

ηC) and the protected chromium per unit residual carbon content ((1–

ηCr)/

ω[C]), as illustrated in

Figure 6. The value of

ω[Cr]/

ω[C] exhibits a monotonic increase with rising temperature, climbing from 1.59 at 1633 K to 4.93 at 1753 K, which suggests an enhanced protective effect of carbon on chromium under higher temperatures. In contrast,

ηV/

ηC demonstrates less temperature sensitivity than (1–

ηCr)/

ω[C], following an initial increase followed by a decline. Beyond 1723 K, the efficacy of carbon in extracting vanadium diminishes. The net effect of carbon accounts for the markedly higher temperature sensitivity observed in the oxidation of vanadium compared to chromium.

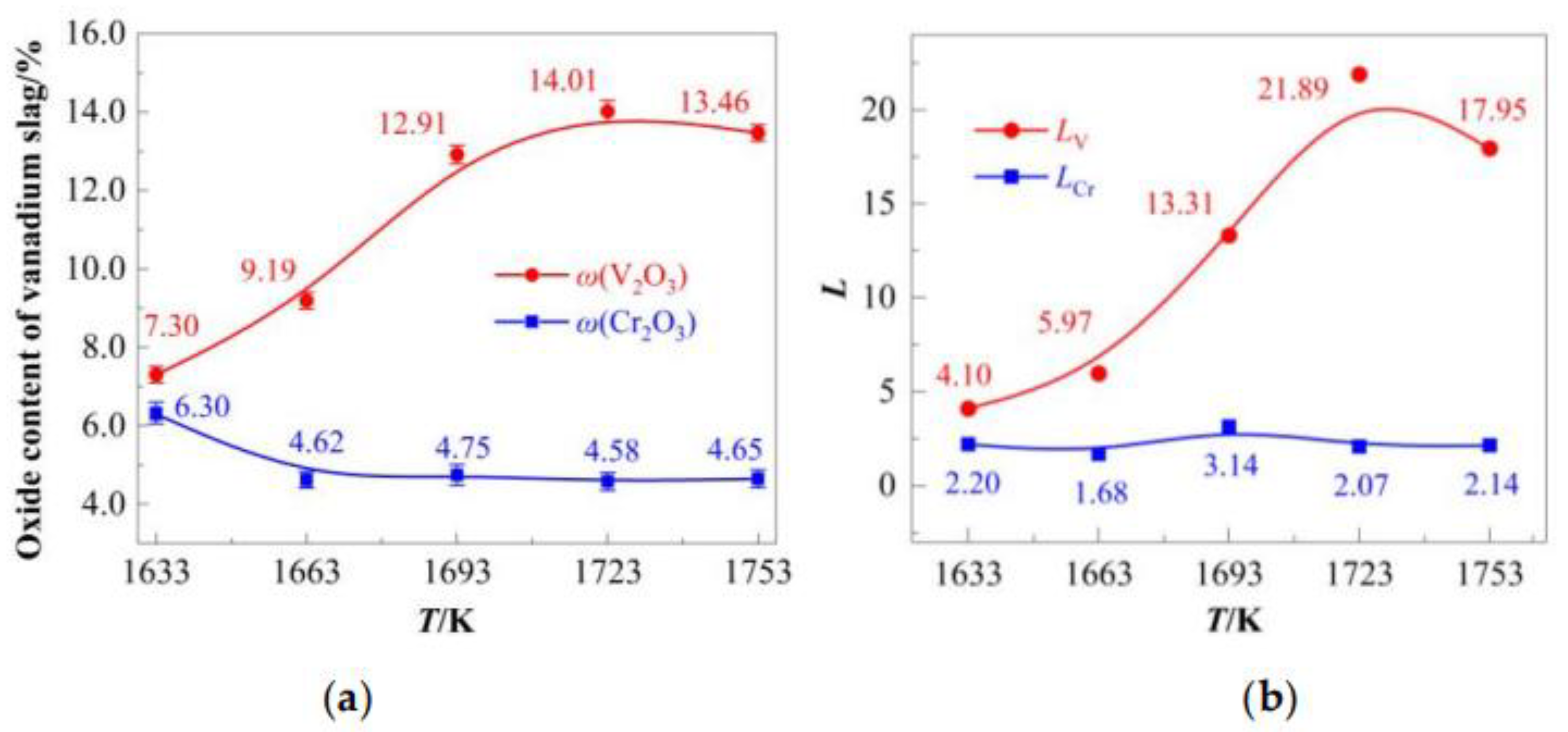

4.1.3. Temperature-Dependent Migration Behavior of Vanadium and Chromium

The migration behavior of vanadium and chromium oxides in the slag phase was critically influenced by temperature variations, as summarized in

Figure 7.

The V

2O

3 content in the slag initially increased with rising temperature, peaking at 14.01% (1723 K), followed by a slight decline to 13.46% at 1753 K (

Figure 7a). In contrast, Cr

2O

3 content exhibited a gradual reduction from 6.30% (1623 K) to 4.65% (1753 K). Correspondingly,

LV surged from 4.10 (1623 K) to 21.89 (1723 K), then decreased to 17.95 (1753 K), while

LCr remained relatively stable within a narrow range (1.68–3.14) across the tested temperatures (

Figure 7b). These results demonstrate that moderate temperature elevation (<1723 K) significantly enhances vanadium partitioning into the slag, whereas chromium migration is minimally affected.

Within the optimized temperature window (1693–1753 K), V

2O

3 content stabilized between 12.91% and 14.01%, while Cr

2O

3 content varied from 4.58% to 4.75%. Notably, despite the temperature-dependent increase in chromium oxidation rate (

Section 4.1.1), oxidized chromium exhibited incomplete migration to the slag phase.

4.2. Effect of FeO Content on Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention

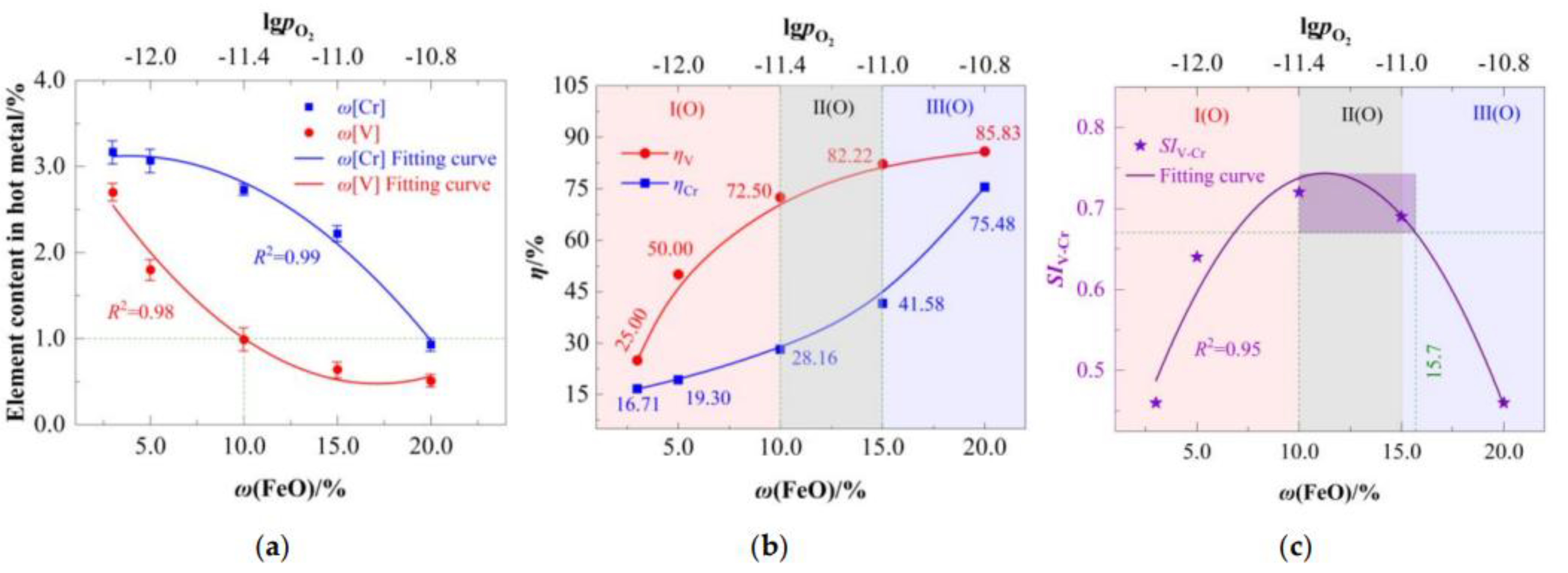

4.2.1. FeO-Dependent Oxidative Separation of [V] and [Cr]

The oxidative separation of [V] and [Cr] in hot metal was systematically investigated under varying

ω(FeO) at 1723 K, as summarized in

Figure 8.

Figure 8a illustrates the equilibrium between slag oxygen potential and residual element content of hot metal. Both

ω[V] and

ω[Cr] exhibit pronounced decreasing trends with increasing

ω(FeO). Empirical relationship between

ω[V] and

ω(FeO) was established using Equation (26):

Based on Equation (26) and the experimental data, it is determined that ω[V] dropped below the critical threshold of 1.0% only when ω(FeO) exceeded 10%, the corresponding oxygen partial pressure = –11.42. This value exceeds the theoretical prediction (–11.91) due to idealized assumptions in the model and competitive FeO consumption by carbon oxidation. Thus, efficient vanadium extraction requires higher oxygen potential than theoretically projected.

Figure 8b plots

ηV and

ηCr against

ω(FeO). Although both efficiencies increase with

ω(FeO), their response curves differ significantly —

ηV exhibits a convex upward trend, in contrast to the concave downward trend of

ηCr. These distinct behaviors form the basis for defining the three characteristic regions listed in

Table 7.

Region I(O) (V-Dominant Zone,

ω(FeO) = 3–10%):

ηV rises sharply due to preferential vanadium oxidation (thermodynamically favored;

Section 2.2), while

ηCr increases marginally.

Region II(O) (Cr-Activation Zone, ω(FeO) = 10–15%): ηCr oxidation accelerates.

Region III(O) (Cr-Runaway Zone, ω(FeO) > 15%): ηCr undergoes rapid escalation, indicating exceedance of chromium’s oxidation threshold.

This divergence underscores the core mechanism of selective oxidation: Vanadium oxidizes readily at low oxygen potentials, whereas chromium requires significantly higher potentials for massive oxidation. Precise oxygen potential control thus enables targeted vanadium extraction with chromium retention.

Figure 8c reveals a non-monotonic trend in

SIV-Cr, which peaks then declines with increasing

ω(FeO). The relationship is fitted by:

Maximizing dSIV-Cr/dω(FeO) = 0 yields a distinct selectivity peak (SIV-Cr = 0.74) at ω(FeO) = 10.5%. Suboptimal oxidation occurs at ω(FeO) < 10.5%, while ω(FeO) > 15.7% promotes excessive Cr oxidation, degrading selectivity.

Thus, effective V/Cr separation (SIV-Cr ≥ 0.67) requires an operational window of ω(FeO) = 10.0–15.7%, corresponding to = –11.4 to –10.9. This range spans “Region II(O)” and early “Region III(O)”. Although chromium begins to oxidize at an FeO concentration of 15%, the practically feasible range is extended to 15.7%. This indicates that FeO can vary by ±0.35% without compromising process stability. Such a tolerance not only enhances the operational flexibility but also guarantees the efficient extraction of vanadium, highlighting its critical role in process control.

Within this window: (1)

ηV > 72.22%,

ηCr < 41.58%; (2)

ω[V] < 1.0%,

ω[Cr] > 2.3%, The requisite oxygen supply (33.1–38.2 kg/tFe) is 27.7–81.1% lower than conventional converter-based vanadium extraction (43.0–195.0 kg/tFe, accounting for 70–90% utilization efficiency [

27]). This demonstrates the feasibility of low-oxygen-potential vanadium extraction with minimal chromium loss—a significant advance toward sustainable refining of high-chromium hot metal.

The optimal operating window of FeO (10–15.7%) determined in this study was obtained at a fixed temperature of 1723 K. Temperature plays a crucial role as it directly affects the equilibrium constant and kinetic rate of the reaction. At higher temperatures, the reducing power of carbon increases, which may enable the same V oxidation efficiency with a lower FeO dosage while better suppressing the oxidation of Cr. Conversely, at lower temperatures, a higher FeO content may be required to compensate for the insufficient reaction kinetics, but this significantly increases the risk of Cr oxidation. Therefore, the control range of FeO is not constant but is closely coupled with temperature.

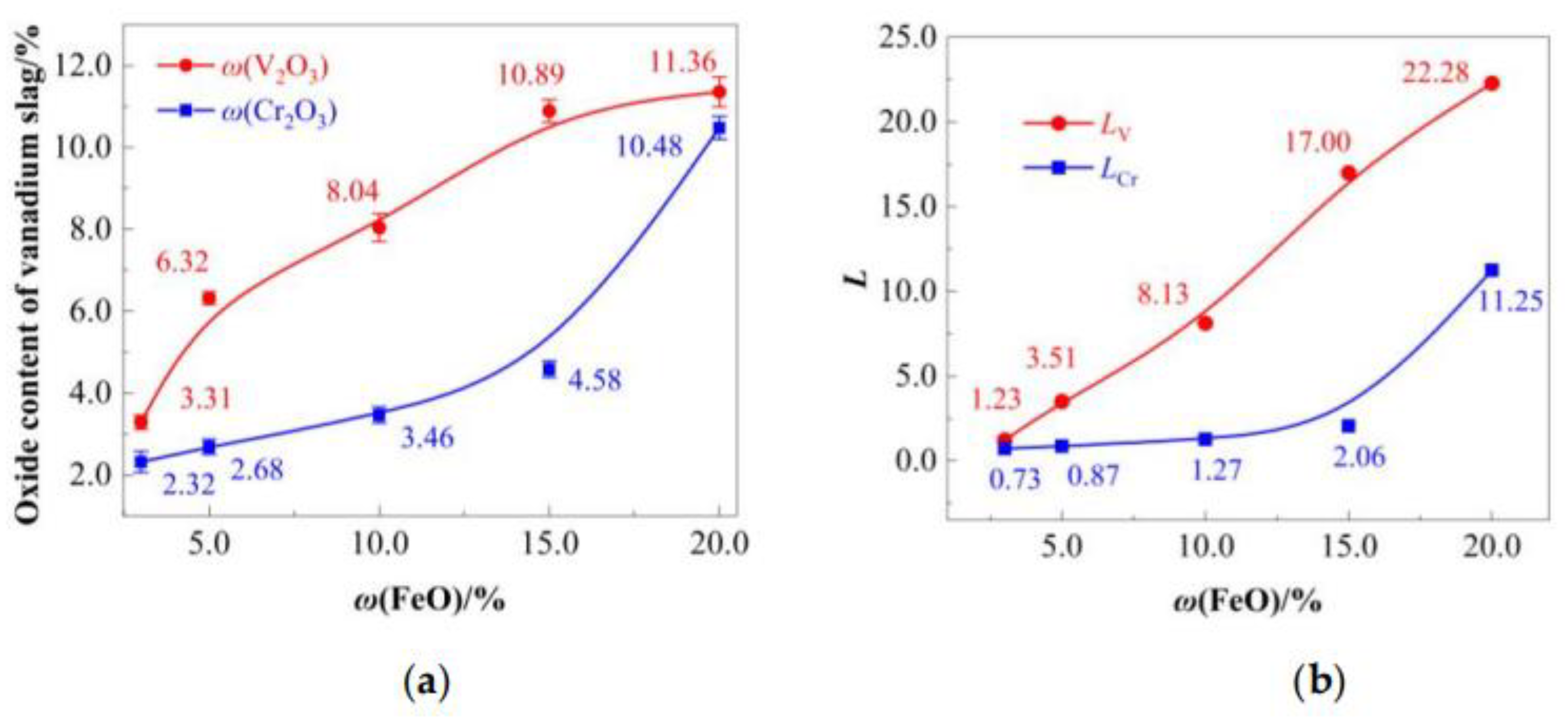

4.2.2. FeO-Dependent Migration of Vanadium and Chromium

The migration behavior of vanadium and chromium oxides into the slag phase under varying

ω(FeO) is illustrated in

Figure 9. As

ω(FeO) increased, both V

2O

3 and Cr

2O

3 contents in the slag rose (

Figure 9a), driven by enhanced oxidative capacity of the slag.

LV surged from 1.22 (3.0% FeO) to 22.28 (15% FeO), with no obvious bending point (

Figure 8b). While chromium migration

LCr exhibited a milder increase (1.68–4.58), with a distinct inflection at 15%

ω(FeO) (

Figure 9b). This indicates that FeO promotes vanadium migration to slag, but low dose

ω(FeO) (15%) has no significant effect on chromium migration.

Within the optimized

ω(FeO) range of 10–15.7% identified in

Section 4.2.1, the vanadium-chromium slag achieves

ω(V

2O

3) values of 8.04–10.88% and

ω(Cr

2O

3) values of 3.46–4.58%.

4.3. Comprehensive Discussion on the Synergistic Control of Temperature and Oxygen Potential

The experimental design of this study adopted the single-factor variable method, which separately revealed the independent influence laws of temperature and FeO dosage on the separation of V-Cr. However, the success of industrial applications relies on the coordinated control of these two key parameters.

A more scientific process control strategy should be regarded as a dynamic optimization process: higher operating temperatures create favorable thermodynamic and kinetic conditions for achieving “low oxygen potential extraction of V”, allowing for the use of lower FeO dosages, thereby achieving efficient extraction of V while maximizing the utilization of carbon’s protective effect on Cr; while operating at lower temperatures, the system is forced into the “high oxygen potential extraction of V” mode, at which the risk of Cr loss significantly increases.

Therefore, the temperature window (1693–1753 K) and FeO window (10–15.7%) determined in this study should be understood as a guiding parameter space. Its core value lies in revealing that the combination of “high temperature - medium-low FeO” is a more optimal path for selective oxidation. Future research can further precisely quantify this coupling relationship through experimental designs such as response surface methodology (RSM) and construct a more accurate mathematical model to guide industrial production.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Vanadium Extraction and Chromium Retention (VECR) Process with Conventional Methods

A systematic comparison between the proposed VECR process and traditional vanadium extraction methods is summarized in

Table 8. The primary differences between these two processes lie in the control of temperature and oxygen potential, and the difference of oxidation rate and composition of vanadium chromium slag caused by these factors.

The VECR process is about 65 K higher than the traditional process. In traditional processes, the temperature is typically maintained below the C-V oxidation transition temperature. In contrast, the VECR process requires the temperature to be controlled nearly C-V oxidation temperature, to ensure maximum SIV-Cr.

Traditional processes involve a relatively high oxygen supply (43.0–195.0 kg/tFe) (as described section in 4.2.1) to create a high-oxygen-potential environment, which promotes vanadium oxidation. However, such conditions also significantly increase the chromium oxidation rate (50–70%), leading to a higher chromium content in the vanadium-slag (5–14%). This not only reduces the recovery value of the vanadium slag but also complicates subsequent chromium recovery. Furthermore, the high oxygen potential and elevated temperatures accelerate equipment wear and increase maintenance costs. In comparison, the VECR process reduces the oxygen supply to 33.1–38.2 kg/tFe, achieving effective vanadium oxidation (ηV: 72.5–82.2%) under low-oxygen-potential conditions while significantly lowering ηCr (< 42.9%).

The VECR process significantly reduces oxygen consumption and chromium oxidation losses. Compared to conventional processes, the oxygen consumption of the VECR process is reduced by more than 80 kg/tFe,

ηCr is reduced by over 40%. This results in improved purity of the vanadium slag. In the vanadium slag formed by VECR process,

ω(V

2O

3) is 10.88–14.01%,

ω(Cr

2O

3) is 3.5–7.3%. These values satisfy the requirements for the recycling and utilization of low-chromium vanadium-chromium slag. Specifically, vanadium slag is considered to have industrial extraction value only when the V

2O

5 content exceeds 10% [

32,

33] (equivalent to V

2O

3 content 8.2%). Additionally, the Cr

2O

3 content in low-chromium vanadium-chromium slag is typically required to be less than 8% [

34].

However, the VECR process also has certain limitations. For instance, under low-oxygen-potential conditions, the reaction rate is relatively slow, potentially requiring a longer reaction time and thereby impacting production efficiency.

Overall, the VECR process demonstrates significant advantages in terms of chromium retention and cost-effective production. By reducing the chromium oxidation rate, this process not only minimizes chromium resource waste, but also achieves efficient resource utilization. Moreover, the lower oxygen supply significantly reduces energy consumption and carbon emissions, aligning with the principles of green metallurgy. From an industrial application perspective, the VECR process is particularly suitable for production scenarios with high demands for vanadium and chromium resource utilization efficiency, especially in regions where chromium resources are scarce or environmental regulations are stringent. In the future, the promotion of this process is expected to achieve broader applications in the steel and metallurgical industries and provide valuable insights for the development of green metallurgical technologies.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and validated a novel pyrometallurgical strategy for the synchronous extraction of vanadium and retention of chromium from high V-Cr hot metal through precise control of selective oxidation. The combined thermodynamic and experimental investigation led to the following key findings:

The thermodynamic analysis established that the temperature window of 1517–1704 K is critical, as it enables boron to function as an effective redox mediator. Within this regime, the oxidation priority of [V] > [C] > [Cr] creates a thermodynamic pathway for selective V extraction. Furthermore, there is a hierarchy of oxygen partial pressure required for the oxidation of vanadium and chromium. An optimal oxygen partial pressure window of -11.91 to -10.94 (logarithmic scale) at 1723 K was identified to achieve high V oxidation while suppressing Cr loss. This theoretical prediction provides a key parameter window for the optimization of experimental conditions, and its core conclusion is directly verified in subsequent experiments.

Temperature-dependent experiments demonstrate differential responses of ηV and ηCr: vanadium oxidation exhibits higher temperature sensitivity than chromium, a phenomenon attributed to the stronger protective effect of carbon on chromium, rather than its promoting effect on vanadium extraction. The optimal temperature range is 1693–1753 K (SIV-Cr > 0.67). In the low-temperature region (<1693 K), vanadium oxidation is incomplete, whereas in the high-temperature region (> 1753 K), the separation efficiency deteriorates.

Both ηV and ηCr increase with the addition of FeO, with ηV consistently exceeding ηCr. [V] oxidation occurring preferentially at lower FeO dosages. The optimal FeO dosage range is determined to be 10.0–15.7%. FeO contents exceeding this range lead to over-oxidation of [Cr], while insufficient FeO additions result in incomplete [V] oxidation.

Under optimized process conditions, ηV exceeds 72.5%, while ηCr remains below 42.9%. These conditions result in a reduction of ω[V] to be less than 1%, while ω[Cr] remains above 2.17%. Additionally, ω(V2O3) and ω(Cr2O3) are 10.88–14.01%, and 3.46–7.31%, respectively, meeting the criteria for recycling low-chromium vanadium slag. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the process in selectively oxidizing vanadium while minimizing chromium oxidation losses.

Compared to traditional processes, the proposed VECR method demonstrates significant advantages. It reduces oxygen consumption by over 80 kg/tFe and cuts Cr oxidation losses by more than 40%, directly translating to lower operational costs and enhanced resource utilization. The resulting V-Cr slag, with 10.88–14.01% V2O3 and 3.5–7.3% Cr2O3, meets the industrial standard for low-Cr feedstock. Most importantly, this process completely eliminates the need for the energy-intensive roasting and complex hydrometallurgical steps, offering a shorter, cleaner, and more economical flowsheet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z., D.Y. and Y.Q.; methodology, H.Z.; investigation, H.Z., Q.L. and F.W.; data curation, H.Z., X.W., L.W. and Q.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. and H.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.W., L.W. and Y.Q.; visualization, L.W. and H.Z.; supervision, Y.Q. and F.W.; project administration, Y.Q.; funding acquisition, D.Y. and Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFB0603805)

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, G.; Diao, J.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Xie, B. Highly efficient utilization of hazardous vanadium extraction tailings containing high chromium concentrations by carbothermic reduction. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 237, 117832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Huang, Q.; Lv, W.; Pei, G.; Lv, X.; Bai, C. Recovery of tailings from the vanadium extraction process by carbothermic reduction method: Thermodynamic, experimental and hazardous potential assessment. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2018, 357, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Huang, Q.; Lv, W.; Pei, G.; Lv, X.; Liu, S. Co-recovery of iron, chromium, and vanadium from vanadium tailings by semi-molten reduction–magnetic separation process. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly 2018, 57, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, R.; Liu, C.; Jiang, M. Self-digestion of Cr-bearing vanadium slag processing residue via hot metal pre-treatment in steelmaking process. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B 2022, 53, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, C. Chromium and iron recovery from hazardous extracted vanadium tailings via direct reduction magnetic separation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 110047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, X.W.W.; B, M.E.Y.A.; A, Y.Q.M.; A, D.X.G.; A, M.Y.W.; C, Z.B.F. Cyclic metallurgical process for extracting V and Cr from vanadium slag: Part I. Separation and recovery of V from chromium-containing vanadate solution. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2021, 31, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kauppinen, T.; Tynjälä, P.; Hu, T.; Lassi, U. Water leaching of roasted vanadium slag: Desiliconization and precipitation of ammonium vanadate from vanadium solution. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 215, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Ma, B.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Gao, M.; Feng, G. Extraction of vanadium from vanadium slag by sodium roasting-ammonium sulfate leaching and removal of impurities from weakly alkaline leach solution. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, K.; Luo, D. Optimization and kinetic analysis of co-extraction of vanadium (IV) and chromium (III) from high chromium vanadium slag with titanium dioxide waste acid. Minerals Engineering 2025, 233, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, T. A sustainable chromium and vanadium extraction and separation process from high-chromium vanadium slag via synchronous roasting and asynchronous leaching. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 368, 133020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, T.; Wen, J.; Yu, T.; Li, F. Review of leaching, separation and recovery of vanadium from roasted products of vanadium slag. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Meng, F.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhen, Y.; Qi, T.; Zheng, S.; Wang, M. A novel process to prepare high-purity vanadyl sulfate electrolyte from leach liquor of sodium-roasted vanadium slag. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 208, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Li, H.-Y.; Chen, X.-M.; Hai, D.; Diao, J.; Xie, B. Eco-friendly chromium recovery from hazardous chromium-containing vanadium extraction tailings via low-dosage roasting. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 164, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Du, G.-C.; Wang, J.-P.; Wu, Z.-X.; Li, H.-Y. Eco-friendly efficient separation of Cr (VI) from industrial sodium vanadate leaching liquor for resource valorization. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 361, 131673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, G. Comparison and evaluation of vanadium extraction from the calcification roasted vanadium slag with carbonation leaching and sulfuric acid leaching. Separation and Purification Technology 2022, 297, 121466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ren, Q.; Tian, J.; Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Shang, Y.; Liu, J.; Fu, L. Efficient recovery of vanadium from calcification roasted-acid leaching tailings enhanced by ultrasound in H2SO4-H2O2 system. Minerals Engineering 2024, 205, 108492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Ye, L.; Du, J. Research progress of vanadium extraction processes from vanadium slag: A review. Separation and Purification Technology 2024, 342, 127035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Y. Removal of sodium from vanadium tailings by calcification roasting in reducing atmosphere. Materials 2023, 16, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Ma, B.; Wang, C. Non-salt roasting mechanism of V–Cr slag toward efficient selective extraction of vanadium. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2023, 126, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Du, H.; Gao, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Direct Leaching of Vanadium from Vanadium-bearing Steel Slag Using NaOH Solutions: A Case Study. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunikata, Y.; Morita, K.; Tsukihashi, F.; Sano, N. Equilibrium Distribution Ratios of Phosphorus and Chromium between BaO-MnO Melts and Carbon Saturated Fe-Cr-Mn Alloys at 1 573 K. ISIJ International 2007, 34, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, W. Physical Chemistry An Advanced Treatise; Elsevier: 2012.

- Chimenos, J.M.; Cuspoca, F.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Mañosa, J.; Rosell, J.R.; Andrés, A.; Faneca, G.; Cabeza, L.F. MSW incineration bottom ash-based alkali-activated binders as an eco-efficient alternative for urban furniture and paving: closing the loop towards sustainable construction solutions. Buildings 2025, 15, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.K.; Rady, M.; Tawfik, N.M.; Kassem, M.; Mahfouz, S.Y. Enhancing strength and sustainability of concrete with steel slag aggregate. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 17068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monfort, O.; Petrisková, P. Binary and ternary vanadium oxides: general overview, physical properties, and photochemical processes for environmental applications. Processes 2021, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-Y.; Tang, P. Optimization on temperature strategy of BOF vanadium extraction to enhance vanadium yield with minimum carbon loss. Metals 2021, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-y.; Tang, P.; Hou, Z.-b.; Wen, G.-h. Investigation of the end-point temperature control based on the critical temperature of vanadium oxidation during the vanadium extraction process in BOF. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 2018, 71, 1957–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, B.; Li, X.; Xiao, F. Influence of Vanadium Extraction Converter Process Optimization on Vanadium Extraction Effect. Metals 2022, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, H.; Brungs, M. Oxidation-reduction equilibria of vanadium in CaO-SiO 2, CaO-Al 2 O 3-SiO 2 and CaO-MgO-SiO 2 melts. Journal of materials science 2003, 38, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lin, M.-M.; Diao, J.; Li, H.-Y.; Xie, B.; Li, G. Novel strategy for green comprehensive utilization of vanadium slag with high-content chromium. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 7, 18133–18141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Sun, Y.; Ning, P.; Xu, G.; Sun, S.; Sun, Z.; Cao, H. Deep understanding of sustainable vanadium recovery from chrome vanadium slag: Promotive action of competitive chromium species for vanadium solvent extraction. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 422, 126791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-c.; Kim, E.-y.; Chung, K.W.; Kim, R.; Jeon, H.-S. A review on the metallurgical recycling of vanadium from slags: towards a sustainable vanadium production. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 12, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivayam, C.; Prathap, K. Recycling Fe (III)/Cr (III) hydroxide, an industrial solid waste for the removal of phosphate from water. Journal of hazardous materials 2005, 123, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Cao, W.; Liang, Y.; Rohani, S.; Xin, Y.; Hua, J.; Ding, C.; Lv, X. Green and efficient separation of vanadium and chromium from high-chromium vanadium slag: a review of recent developments. Green Chemistry 2024, 26, 10006–10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram.

Figure 2.

Relationship between of oxidation reactions of [C], [V], and [Cr] and temperature under standard conditions.

Figure 2.

Relationship between of oxidation reactions of [C], [V], and [Cr] and temperature under standard conditions.

Figure 3.

Oxygen partial pressure in equilibrium with [V] and [Cr] when ω[C] = 4%.

Figure 3.

Oxygen partial pressure in equilibrium with [V] and [Cr] when ω[C] = 4%.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of molybdenum muffle resistance furnace.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of molybdenum muffle resistance furnace.

Figure 5.

Effects of temperature on the oxidation separation of [V] and [Cr]: (a) Influence of temperature on ω[V], ω[Cr] and ω[C]; (b) Effect of temperature on ηV, ηCr and ηC; (c) Impact of temperature on SIV-Cr.

Figure 5.

Effects of temperature on the oxidation separation of [V] and [Cr]: (a) Influence of temperature on ω[V], ω[Cr] and ω[C]; (b) Effect of temperature on ηV, ηCr and ηC; (c) Impact of temperature on SIV-Cr.

Figure 6.

Effect of carbon on vanadium extraction and chromium retention.

Figure 6.

Effect of carbon on vanadium extraction and chromium retention.

Figure 7.

Effect of temperature on vanadium chromium migration: (a) Effect of temperature on the content of V2O3 and Cr2O3 in the final slag, (b) Effect of temperature on the slag-gold partition ratio.

Figure 7.

Effect of temperature on vanadium chromium migration: (a) Effect of temperature on the content of V2O3 and Cr2O3 in the final slag, (b) Effect of temperature on the slag-gold partition ratio.

Figure 8.

Influence of ω(FeO) on the oxidative separation of [V] and [Cr]: (a) Residual ω[V] and ω[Cr] in hot metal, (b) ηV and ηCr, (c) SIV-Cr index.

Figure 8.

Influence of ω(FeO) on the oxidative separation of [V] and [Cr]: (a) Residual ω[V] and ω[Cr] in hot metal, (b) ηV and ηCr, (c) SIV-Cr index.

Figure 9.

Influence of ω(FeO) dosage on vanadium and chromium migration: (a) V2O3 and Cr2O3 content in final slag, (b) Distribution ratios (LV and LCr).

Figure 9.

Influence of ω(FeO) dosage on vanadium and chromium migration: (a) V2O3 and Cr2O3 content in final slag, (b) Distribution ratios (LV and LCr).

Table 1.

Typical composition of vanadium-chromium-containing hot metal/wt.%.

Table 1.

Typical composition of vanadium-chromium-containing hot metal/wt.%.

| Element |

C |

Si |

Mn |

Cr |

V |

| Content |

4.0 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

Table 2.

Interaction coefficients of C-Cr, Cr-Cr, C-V and V-V.

Table 2.

Interaction coefficients of C-Cr, Cr-Cr, C-V and V-V.

|

|

|

|

| −0.12 |

−0.0003 |

−0.16 |

0.015 |

Table 3.

Chemical composition of raw materials for initial melt preparation/wt.%.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of raw materials for initial melt preparation/wt.%.

| Materials |

Fe |

V |

Cr |

C |

Si |

Mn |

S |

P |

|

BF ironpowder

|

88.50 |

|

|

4.00 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.005 |

0.005 |

| FeV50 powder |

47.10 |

50.00 |

|

0.65 |

1.45 |

0.48 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

| HC FeCr powder |

42.50 |

|

49.53 |

7.45 |

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Experimental scheme.

Table 4.

Experimental scheme.

| Heat no. |

Design Stage |

Temperature/K |

ω(FeO)in final slag (set value), %

|

Initialslag, g

|

|

| FeO |

CaO |

SiO2 |

R2 |

| 1 |

1 (Temp) |

1633 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

19.8 |

9. 9 |

1.8 |

| 2 |

1 (Temp) |

1663 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

19.8 |

9. 9 |

| 3 |

1 (Temp) |

1693 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

19.8 |

9. 9 |

| 4 |

1 (Temp) |

1723 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

19.8 |

9. 9 |

| 5 |

1 (Temp) |

1753 |

10.0 |

14.9 |

19.8 |

9. 9 |

| 6 |

2 (FeO) |

1723 |

3.0 |

12.1 |

21.6 |

10.9 |

| 7 |

2 (FeO) |

1723 |

5.0 |

12.9 |

21.0 |

10.6 |

| 8 |

2 (FeO) |

1723 |

15.0 |

17.1 |

18.3 |

9.1 |

| 9 |

2 (FeO) |

1723 |

20.0 |

19.1 |

17.1 |

8.4 |

Table 7.

Characteristic regions defined by ηV and ηCr oxidation behavior versus ω(FeO).

Table 7.

Characteristic regions defined by ηV and ηCr oxidation behavior versus ω(FeO).

| Region |

Name |

ω(FeO) Range |

Dominant Process |

ηV/ηCr

|

| Ⅰ(O) |

V-Dominant Zone |

3–10% |

Vanadium Preferential Oxidation |

2.5–3.1 |

| Ⅱ(O) |

Cr-Activation Zone |

10–15% |

Chromium Oxidation Activation |

1.8–2.4 |

| Ⅲ(O) |

Cr-Runaway Zone |

>15% |

Chromium Massive Oxidation |

<1.1 |

Table 8.

Comparison of process parameters and results of VECR process with traditional process.

Table 8.

Comparison of process parameters and results of VECR process with traditional process.

| Parameter |

Traditional Process |

VECR Process |

Improvement |

| Temperature/K |

1623–1693 [27,28] |

1693–1753 |

+65 K (optimized oxidation) |

| Oxygen supply/kg·(tFe)-1

|

43.0–195.0 |

33.1–38.2 |

>80 kg/tFe reduction |

|

ηV/% |

75.0–90.0 [27] |

72.5–82.2 |

Comparable efficiency |

|

ηCr/% |

50.0–70.0 [29] |

28.2–42.9 |

>40% reduction |

|

ω(V2O3)/% |

8.2–16.5 [30,31] |

10.9–14.0 |

Higher purity |

|

ω(Cr2O3)/% |

5.0–10.0 |

3.5–7.3 |

Meets low-Cr standards |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).