Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- to assess how climate change is impacting welfare indicators such as heat stress, water availability, and welfare-related pathologies;

- to examine the quality of the nutritional contribution of pasture modified by climate change, both in production timing and in the composition of herbaceous plants;

- to compare the vulnerability and adaptive capacities of different livestock species (cattle, sheep, and goats) and breeds;

- to identify adaptation strategies and policy recommendations that could enhance the resilience of Alpine livestock systems.

2. The Alpine Bioregion: Livestock Sector in the Context of Climate Change

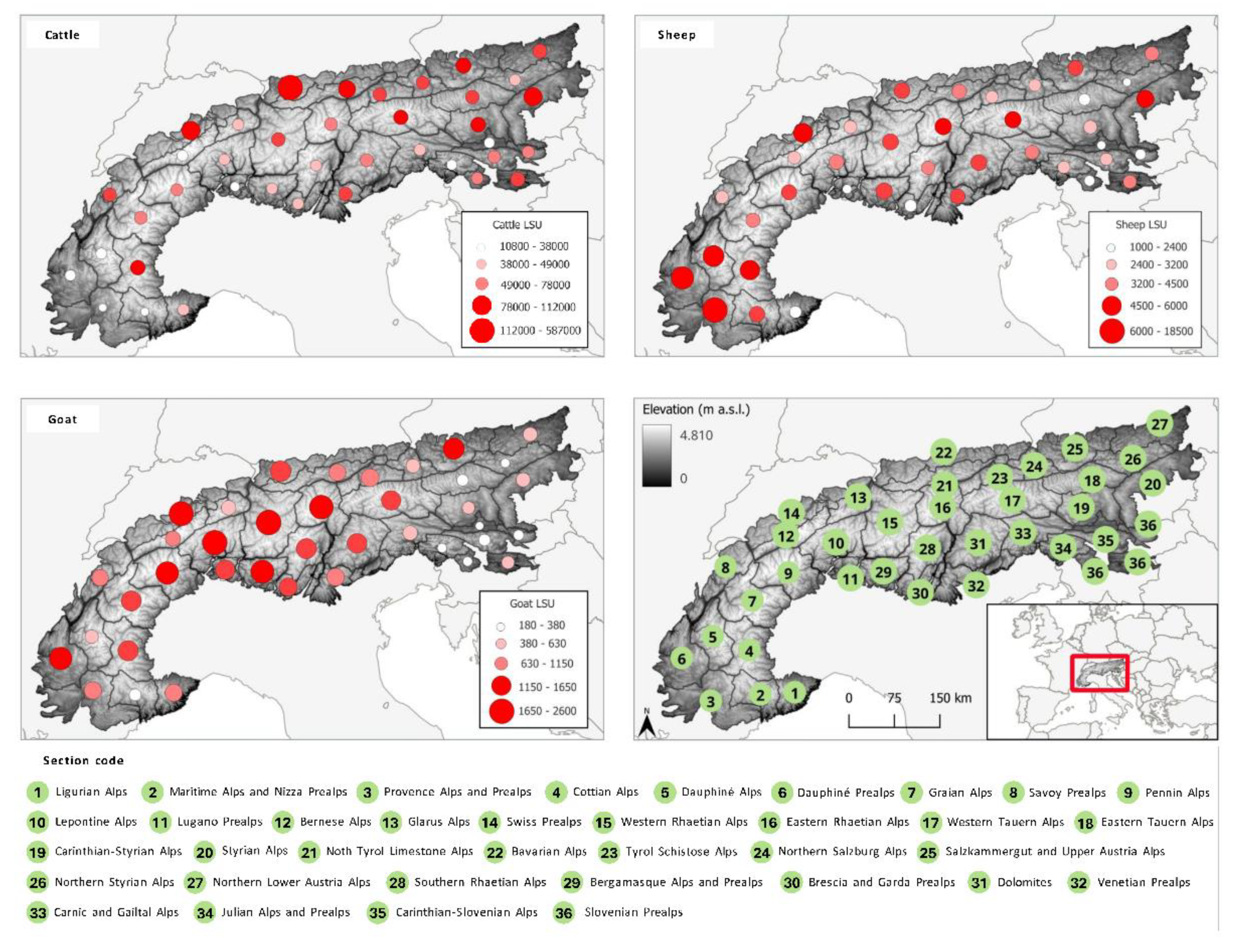

2.1. Livestock Activities in the Alps

2.2. Socio-Economic Relevance of the Agri-Food Chain in the Alps

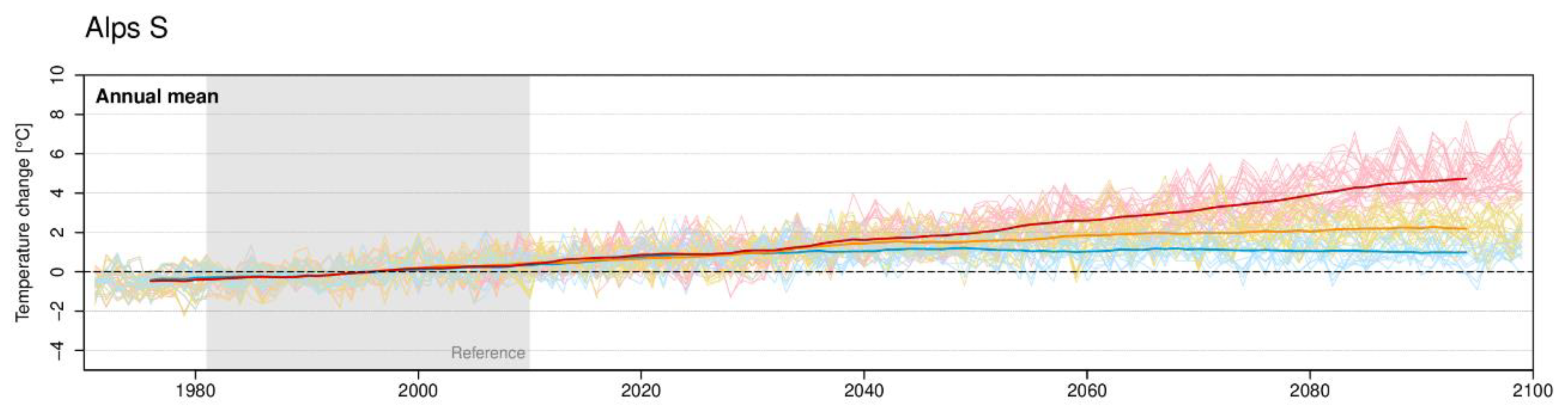

2.3. Climate Change in the Alps

2.4. Legislation Supporting Livestock Activities in the Alps

3. Impacts of Climate Change on Livestock Welfare

3.1. Measuring Animal Welfare in Extensive Systems

3.2. Impacts on Pasture Composition and Nutritional Quality

3.3. Consequences on Agroecosystems’ Diversity

3.3.1. Interdependence of Animal Welfare and Biodiversity

- i)

- The ecological role of livestock, such as the properly managed grazing that maintains open habitats and prevents shrub encroachment, supports diverse plant and invertebrate communities [94]. Instead of overgrazing or undergrazing that may disrupt this balance, reducing both habitat quality and animal welfare through degraded forage and exposure to harsher conditions;

- ii)

- Biodiversity also acts as a buffer, as high biodiversity can help stabilize ecosystems against climate variability. For example, diverse swards can provide more stable and nutritious forage across seasons, enhancing the resilience of livestock systems [105]. Rich pollinator communities also contribute to forage seed production and grassland regeneration [106];

- iii)

- Lately, welfare-driven biodiversity outcomes have been observed, where animals in poor welfare conditions often exhibit altered behaviors (e.g., excessive foraging, avoidance of thermal stress areas), which may change grazing pressure and spatial patterns. This can lead to heterogeneity loss and unintended ecological consequences, such as reduced insect or bird diversity [107].

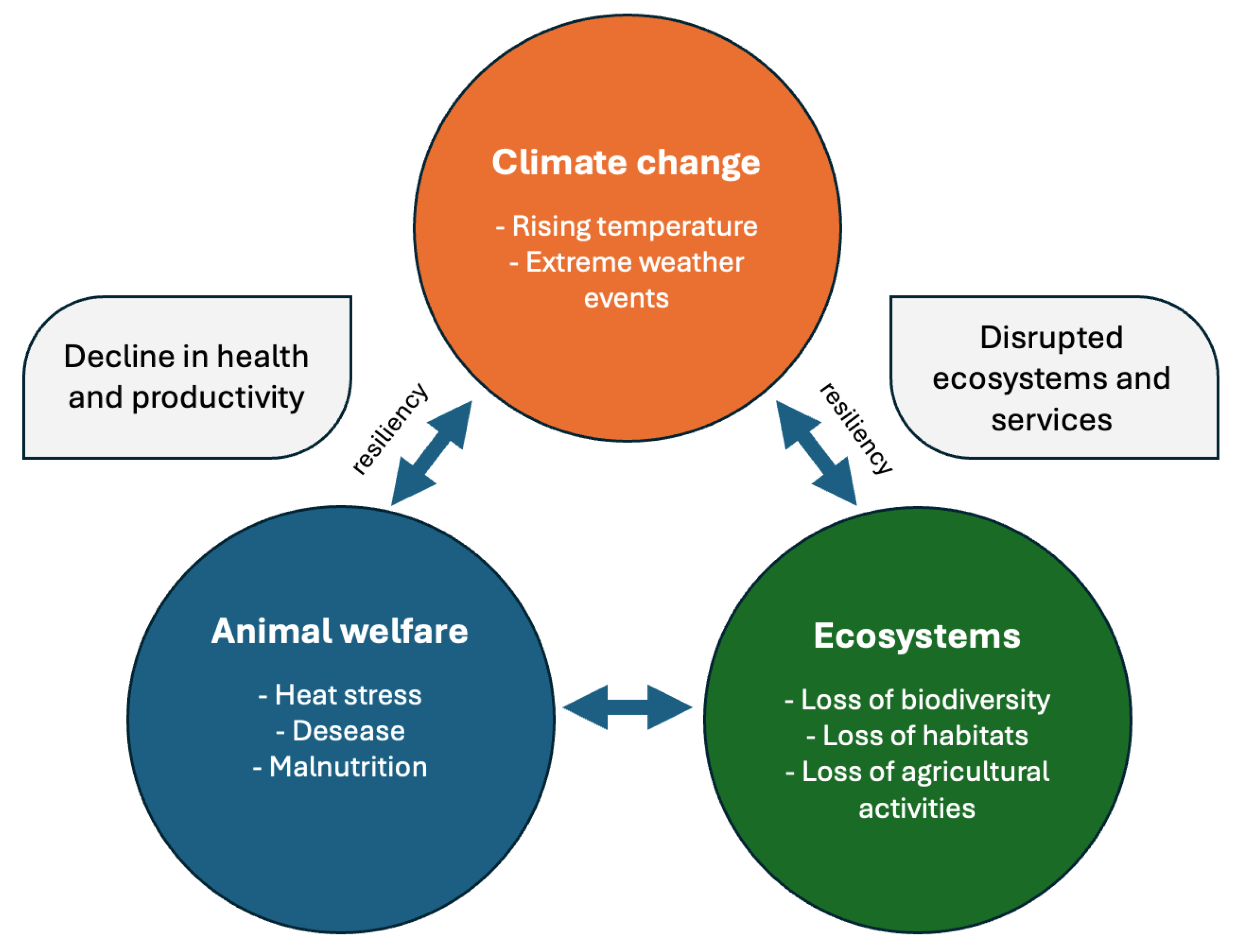

3.3.2. The Climate–Welfare–Biodiversity Feedback Loop

3.3.3. Impacts of Grazing Intensity on Arthropod and Plant Biodiversity in European Pasturelands

3.4. Adaptive Capacities of Livestock Species and Breeds

| Dimension | Cattle | Sheep | Goats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat tolerance |

- -* | High susceptibility to heat stress [115,123] | + | Better tolerance to temperature fluctuations [113,117] | + + | Well-adapted to heat and variable climates [113,119] |

| Water efficiency |

- | Higher water needs per unit biomass and lower dehydration tolerance [58,124] | ± | Intermediate water efficiency [113,125] | + + | Adapted to arid, water-scarce conditions [125,126] |

| Forage requirements |

- - | Bulk grazers needing higher-quality grasses; less able to utilize browse [58,127] | + | Utilizes diverse forage efficiently; some browsing flexibility [128,129] | + + | High flexibility; tolerant of low-quality, diverse and byproduct feeds, shrubs and woody plants [130,131] |

| Feeding behavior |

± | Primarily grazers (grass-focused); require managed pastures [127,132] | + | Intermediate grazers/foragers with moderate selectivity [128] | + + | Browsers, tolerate plant toxins, strong ability to switch diets [128,130] |

| Terrain Adaptability | - | Limited to gentler terrain [133,134] | + | Can graze in marginal areas [133,135] | + + | Thrive in steep, rocky terrain [133,134] |

| Climate Resilience |

- | Higher vulnerability to heat/drought extremes [124,136] | + | Moderate resilience under variability; still impacted by severe droughts [113,137] | + + | Greater resilience to combined stressors: heat, drought, low-quality feed [131,138] |

| Role in ecosystem |

± | Grass-dominant grazing; can maintain meadows but less shrub control [134,135] | + | Maintains pasture and supports biodiversity; moderate shrub/forb use [133,135] | + + | Controls shrubs, maintains open landscapes [119,130] |

| Management flexibility | - - | Needs intensive management (housing, water, feed) [58,139] | + | Suitable for extensive and marginal systems [113,137] | + + | Highly adaptable via transhumance and low-input systems [113,126] |

| Economic resilience |

- | High economic risk under climate stress [116,121] | + | Generally resilient economics with diversified products (meat, wool) [113,137] | + | Cost-effective in resource-limited systems; niche products [126,130] |

| Contribution to sustainability |

± | Needs integration with ecological services; potential grassland maintenance benefits with careful stocking [124,134] | ± | Supports productivity & ecological conservation; Lower input use and ability to use marginal land [113,135] | + | Use of shrubs reduces encroachment; efficient on marginal land; strong landscape services [130,135] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meyer, M.; Gazzarin, C.; Jan, P.; Benni, N.E. Understanding the Heterogeneity of Swiss Alpine Summer Farms for Tailored Agricultural Policies: A Typology. Mountain Research and Development 2024, 44. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, E.; Kramm, N. High Nature Value (HNV) Farming and the Management of Upland Diversity. A Review. European Countryside 2012, 4. [CrossRef]

- Price, M. High Nature Value Farming in Europe: 35 European Countries—Experiences and Perspectives. Mountain Research and Development 2013, 33, 480. [CrossRef]

- Tasser, E.; Leitinger, G.; Tappeiner, U.; Schirpke, U. Shaping the European Alps: Trends in Landscape Patterns, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. CATENA 2024, 235, 107607. [CrossRef]

- Tasser, E.; Walde, J.; Tappeiner, U.; Teutsch, A.; Noggler, W. Land-Use Changes and Natural Reforestation in the Eastern Central Alps. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2007, 118, 115–129. [CrossRef]

- IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the In-Tergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2021.

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of Climate Changes on Animal Production and Sustainability of Livestock Systems. Livestock Science 2010, 130, 57–69. [CrossRef]

- Tasser, E.; Tappeiner, U. Impact of Land Use Changes on Mountain Vegetation. Applied Vegetation Science 2002, 5, 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Sturaro, E.; Marchiori, E.; Cocca, G.; Penasa, M.; Ramanzin, M.; Bittante, G. Dairy Systems in Mountainous Areas: Farm Animal Biodiversity, Milk Production and Destination, and Land Use. Livestock Science 2013, 158, 157–168. [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, L.; Bovolenta, S.; Gusmeroli, F.; Salvador, S.; Sturaro, E. Environmental Sustainability of Alpine Livestock Farms. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2014, 13, 3155. [CrossRef]

- Flury, C.; Huber, R.; Tasser, E. Future of Mountain Agriculture in the Alps. In The Future of Mountain Agriculture; Mann, S., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 105–126 ISBN 978-3-642-33584-6.

- QGIS.org QGIS Geographic Information System 2024.

- Capleymar-Homoalpînus Subdivisions of the Alps According to SOIUSA 2020.

- Malek, Ž.; Romanchuk, Z.; Yashchun, O.; See, L. A Harmonized Data Set of Ruminant Livestock Presence and Grazing Data for the European Union and Neighbouring Countries. Sci Data 2024, 11, 1136. [CrossRef]

- Agreste Indicateurs: Cartes, Données et Graphiques 2020.

- Eurostat Glossary: Livestock Unit (LSU). European Statistical Office (Eurostat) Statistics Explained, Public Guide to European Statistics 2023.

- Eurostat Animal Production (Apro_anip) 2025.

- Alpine Convention The Alps in 25 Maps; Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention (Eds): Innsbruck, Austria, 2018;

- DRAAF/Agreste Recensement Agricole 2020 – Dossier de Presse Régional (Auvergne–Rhône-Alpes) 2021.

- Statistics Austria Agricultural and Forestry Holdings Increased in Size 2022.

- Destatis Viehhaltung Im Letzten Jahrzehnt: Weniger, Aber Größere Betriebe – Zahl Der Betriebe Mit Tierhaltung Seit 2010 Um 25% Ge-Sunken 2021.

- SURS Agricultural Census, Slovenia, 2020: Average Size and LSU per Holding Increased 2021.

- SURS Agricultural Census, Slovenia, 2020: Holdings and Livestock Units 2010–2020 2021.

- BFS Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2023,.

- Eurostat Agri-Environmental Indicator—Livestock Patterns (Statistics Explained) 2024.

- Mattalia, G.; Volpato, G.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Interstitial but Resilient: Nomadic Shepherds in Piedmont (Northwest Italy) Amidst Spatial and Social Marginalization. Human Ecology 2018, 46, 747–757. [CrossRef]

- Transhumance and biodiversity in European mountains; Bunce, R.G., Ed.; IALE publication series; ALTERRA: Wageningen, 2004; ISBN 978-90-327-0337-0.

- Alpine Convention Pastures, Vulnerability, and Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change Impacts in the Alps 2019.

- Genovese, D.; Culasso, F.; Giacosa, E.; Battaglini, L.M. Can Livestock Farming and Tourism Coexist in Mountain Regions? A New Business Model for Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lora, I.; Zidi, A.; Magrin, L.; Prevedello, P.; Cozzi, G. An Insight into the Dairy Chain of a Protected Designation of Origin Cheese: The Case Study of Asiago Cheese. Journal of Dairy Science 2020, 103, 9116–9123. [CrossRef]

- Keenleyside, C.; Beaufoy, G.; Tucker, G.; Jones, G. High Nature Value Farming throughout EU-27 and Its Financial Support under the CAP; Institute for European Environmental Policy, 2014;

- Gobiet, A.; Kotlarski, S.; Beniston, M.; Heinrich, G.; Rajczak, J.; Stoffel, M. 21st Century Climate Change in the European Alps—A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 493, 1138–1151. [CrossRef]

- Pettenati, G.; Amo, E.; Woods, M. Assembling Mountains through Food. Typical Cheese and Politics of Mountainness in the Italian Alps. Geoforum 2025, 159, 104210. [CrossRef]

- Tognon, A.; Gretter, A.; Andreola, M.; Betta, A. Mountain Farming in the Making: Approaches to Alpine Rural Agro-Food Challenges in Trentino. rga 2022, 110–2. [CrossRef]

- Lomba, A.; McCracken, D.; Herzon, I. Editorial: High Nature Value Farming Systems in Europe. E&S 2023, 28, art20. [CrossRef]

- Kotlarski, S.; Gobiet, A.; Morin, S.; Olefs, M.; Rajczak, J.; Samacoïts, R. 21st Century Alpine Climate Change. Clim Dyn 2023, 60, 65–86. [CrossRef]

- Beniston, M.; Farinotti, D.; Stoffel, M.; Andreassen, L.M.; Coppola, E.; Eckert, N.; Fantini, A.; Giacona, F.; Hauck, C.; Huss, M.; et al. The European Mountain Cryosphere: A Review of Its Current State, Trends, and Future Challenges. The Cryosphere 2018, 12, 759–794. [CrossRef]

- Pörtner., H.O.; Scholes, R.J.; Agard, J.; Archer, E.; Arneth, A.; Bai, X.; Zommers, Z. Climate Change Impacts and Risks; 2022;

- Beniston, M. Mountain Weather and Climate: A General Overview and a Focus on Climatic Change in the Alps. Hydrobiologia 2006, 562, 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Frei, P.; Kotlarski, S.; Liniger, M.A.; Schär, C. Future Snowfall in the Alps: Projections Based on the EURO-CORDEX Regional Climate Models. The Cryosphere 2018, 12, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M.; Monteiro, D.; Filhol, S.; Gascoin, S.; Marty, C.; Hagenmuller, P.; Morin, S.; Choler, P.; Thuiller, W. The European Alps in a Changing Climate: Physical Trends and Impacts. Comptes Rendus. Géoscience 2025, 357, 25–42. [CrossRef]

- Gerberding, K.; Schirpke, U. Mapping the Probability of Forest Fire Hazard across the European Alps under Climate Change Scenarios. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 377, 124600. [CrossRef]

- Dubo, T.; Palomo, I.; Camacho, L.L.; Locatelli, B.; Cugniet, A.; Racinais, N.; Lavorel, S. Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Change Adaptation Are Not Located Where They Are Most Needed across the Alps. Reg Environ Change 2023, 23, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vitasse, Y.; Ursenbacher, S.; Klein, G.; Bohnenstengel, T.; Chittaro, Y.; Delestrade, A.; Monnerat, C.; Rebetez, M.; Rixen, C.; Strebel, N.; et al. Phenological and Elevational Shifts of Plants, Animals and Fungi under Climate Change in the E Uropean A Lps. Biological Reviews 2021, 96, 1816–1835. [CrossRef]

- Casale, F.; Bocchiola, D. Climate Change Effects upon Pasture in the Alps: The Case of Valtellina Valley, Italy. Climate 2022, 10, 173. [CrossRef]

- Compagno, L.; Eggs, S.; Huss, M.; Zekollari, H.; Farinotti, D. Brief Communication: Do 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0 °C Matter for the Future Evolution of Alpine Glaciers? The Cryosphere 2021, 15, 2593–2599. [CrossRef]

- Losapio, G.; Lee, J.R.; Fraser, C.I.; Gillespie, M.A.K.; Kerr, N.R.; Zawierucha, K.; Hamilton, T.L.; Hotaling, S.; Kaufmann, R.; Kim, O.-S.; et al. Impacts of Deglaciation on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Function. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. 2025, 1, 371–385. [CrossRef]

- European Union EUR-Lex - 22006A0930(01) 2006.

- European Union Convention on the Protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention). Official Journal of the European Communities 1996, No 61/32.

- Alpine Convention Climate Action Plan 2.0 2021.

- European Commission Common Agricultural Policy 2023-2027: Commission Adopts First CAP Strategic Plans 2022.

- European Commission Eco-Schemes 2024.

- Adams, N.; Sans, A.; Trier Kreutzfeldt, K.-E.; Arias Escobar, M.A.; Oudshoorn, F.W.; Bolduc, N.; Aubert, P.-M.; Smith, L.G. Assessing the Impacts of EU Agricultural Policies on the Sustainability of the Livestock Sector: A Review of the Recent Literature. Agric Hum Values 2025, 42, 193–212. [CrossRef]

- Nori Assessing the Policy Frame in Pastoral Areas of Europe; Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSC), 2022;

- Rouet-Leduc, J.; Pe’er, G.; Moreira, F.; Bonn, A.; Helmer, W.; Shahsavan Zadeh, S.A.A.; Zizka, A.; Van Der Plas, F. Effects of Large Herbivores on Fire Regimes and Wildfire Mitigation. Journal of Applied Ecology 2021, 58, 2690–2702. [CrossRef]

- Gervasi, V.; Linnell, J.D.C.; Berce, T.; Boitani, L.; Cerne, R.; Ciucci, P.; Cretois, B.; Derron-Hilfiker, D.; Duchamp, C.; Gastineau, A.; et al. Ecological Correlates of Large Carnivore Depredation on Sheep in Europe. Global Ecology and Conservation 2021, 30, e01798. [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, H.L.; Quinn, C.H.; Holmes, G.; Sait, S.M.; López-Bao, J.V. Welcoming Wolves? Governing the Return of Large Carnivores in Traditional Pastoral Landscapes. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 2, 710218. [CrossRef]

- Sejian, V.; Bhatta, R.; Gaughan, J.B.; Dunshea, F.R.; Lacetera, N. Review: Adaptation of Animals to Heat Stress. Animal 2018, 12, s431–s444. [CrossRef]

- Bernabucci, U.; Lacetera, N.; Baumgard, L.H.; Rhoads, R.P.; Ronchi, B.; Nardone, A. Metabolic and Hormonal Acclimation to Heat Stress in Domesticated Ruminants. Animal 2010, 4, 1167–1183. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Muir, J.P.; Riley, D.G.; Fox, D.G. The Role of Ruminant Animals in Sustainable Livestock Intensification Programs. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 2015, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Koluman (Darcan), N. Impact of Climate Change on the Dairy Industry in Temperate Zones: Predications on the Overall Negative Impact and on the Positive Role of Dairy Goats in Adaptation to Earth Warming. Small Ruminant Research 2015, 123, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Dibari, C.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; Argenti, G.; Bindi, M.; Carotenuto, F.; Moriondo, M.; Padovan, G.; Pardini, A.; Staglianò, N.; Vagnoli, C.; et al. Expected Changes to Alpine Pastures in Extent and Composition under Future Climate Conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 926. [CrossRef]

- Godde, C.M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Mayberry, D.E.; Thornton, P.K.; Herrero, M. Impacts of Climate Change on the Livestock Food Supply Chain; a Review of the Evidence. Global Food Security 2021, 28, 100488. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Downing, M.M.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Harrigan, T.; Woznicki, S.A. Climate Change and Livestock: Impacts, Adaptation, and Mitigation. Climate Risk Management 2017, 16, 145–163. [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, W.A.; Cao, L.C.; Nurjadi, D.; Velavan, T.P. Addressing the Rise of Autochthonous Vector-Borne Diseases in a Warming Europe. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, 149, 107275. [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.J.; White, P.C.L.; McClean, C.J.; Marion, G.; Evans, A.; Hutchings, M.R. Predicting Impacts of Climate Change on Fasciola Hepatica Risk. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16126. [CrossRef]

- Del Lesto, I.; Magliano, A.; Casini, R.; Ermenegildi, A.; Rombolà, P.; De Liberato, C.; Romiti, F. Ecological Niche Modelling of Culicoides Imicola and Future Range Shifts under Climate Change Scenarios in Italy. Medical Vet Entomology 2024, 38, 416–428. [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.M.; Schutz, M.M. An Interdisciplinary Review of Body Condition Scoring for Dairy Cattle. The Professional Animal Scientist 2008, 24, 507–529. [CrossRef]

- Radostits, O. M.; Blood, D. C., (second); Gay, C. C. (third) Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses (10th Ed.); 10th ed.; Saunders - Elsevier: Edinburgh, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7020-2777-2.

- Whay, H. The Journey to Animal Welfare Improvement. Anim. welf. 2007, 16, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code – Animal Welfare 2021.

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, G.; Jensen, M.B.; Moe, R.O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L.J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; Langbein, J.; et al. Assessment of Positive Emotions in Animals to Improve Their Welfare. Physiology & Behavior 2007, 92, 375–397. [CrossRef]

- Diskin, M.; Morris, D. Embryonic and Early Foetal Losses in Cattle and Other Ruminants. Reprod Domestic Animals 2008, 43, 260–267. [CrossRef]

- Wall, R.L.; Shearer, D.; Wall, R.L.; Wall, R.L. Veterinary Ectoparasites: Biology, Pathology, and Control; 2nd ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford Malden, MA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-470-69050-5.

- Mader, T.L.; Davis, M.S.; Brown-Brandl, T. Environmental Factors Influencing Heat Stress in Feedlot Cattle1,2. Journal of Animal Science 2006, 84, 712–719. [CrossRef]

- Steagall, P.V.; Bustamante, H.; Johnson, C.B.; Turner, P.V. Pain Management in Farm Animals: Focus on Cattle, Sheep and Pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 1483. [CrossRef]

- Schlink, A.C.; Nguyen, M.L.; Viljoen, G.J. Water Requirements for Livestock Production: A Global Perspective: -EN- -FR- L’utilisation de l’eau Dans Le Secteur de l’élevage: Une Perspective Mondiale -ES- Necesidades de Agua Para La Producción Pecuaria Desde Una Perspectiva Mundial. Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE 2010, 29, 603–619. [CrossRef]

- Argenti, G.; Staglianò, N.; Bellini, E.; Messeri, A.; Targetti, S. Environmental and Management Drivers of Alpine Grassland Vegetation Types. Italian Journal of Agronomy 2020, 15, 1600. [CrossRef]

- Baumgard, L.H.; Rhoads, R.P.; Rhoads, M.L.; Gabler, N.K.; Ross, J.W.; Keating, A.F.; Boddicker, R.L.; Lenka, S.; Sejian, V. Impact of Climate Change on Livestock Production. In Environmental Stress and Amelioration in Livestock Production; Sejian, V., Naqvi, S.M.K., Ezeji, T., Lakritz, J., Lal, R., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 413–468 ISBN 978-3-642-29204-0.

- Sharma, S.K.; Rathore, G.; Joshi, M. Impact of Climate Change on Animal Health and Mitigation Strategies: A Review. IJAR 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gelybó, G.; Tóth, E.; Farkas, C.; Horel, Á.; Kása, I.; Bakacsi, Z. Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Soil Properties. Agrokem 2018, 67, 121–141. [CrossRef]

- Lake, I.R.; Hooper, L.; Abdelhamid, A.; Bentham, G.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Draper, A.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Hulme, M.; Hunter, P.R.; Nichols, G.; et al. Climate Change and Food Security: Health Impacts in Developed Countries. Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120, 1520–1526. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.R.; Dean, M.R.U.; Alungo, B. Climate Change Impacts on Livestock Production and Possible Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies in Developing Countries: A Review. JAS 2022, 14, 240. [CrossRef]

- Birnie-Gauvin, K.; Peiman, K.S.; Raubenheimer, D.; Cooke, S.J. Nutritional Physiology and Ecology of Wildlife in a Changing World. Conservation Physiology 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Opinion on the Overall Effects of Farming Systems on Animal Welfare and the Impact of Animal Welfare on the Envi-Ronment. EFSA Journal 2009, 1143, 1–38.

- Butterworth, A.; Rooney, N.; Keeling, L. Animal Welfare Indicators Review 2011.

- Singh, S.V.; Singh, S. Resilience of Livestock Production under Varying Climates. J. Agrometeorol. 2023, 25, 183–184. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M.D.; Vallin, H.E.; Roberts, B.P. Animal Board Invited Review: Grassland-Based Livestock Farming and Biodiversity. animal 2022, 16, 100671. [CrossRef]

- Potts, S.G.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.; Ngo, H.T.; Aizen, M.A.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Breeze, T.D.; Dicks, L.V.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Hill, R.; Settele, J.; et al. Safeguarding Pollinators and Their Values to Human Well-Being. Nature 2016, 540, 220–229. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.K.; Homburger, H.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Luescher, A. Grazing Intensity and Ecosystem Services in the Alpine Region. Agrarforschung Schweiz 2013, 4, 222–229.

- Manning, P.; Slade, E.M.; Beynon, S.A.; Lewis, O.T. Functionally Rich Dung Beetle Assemblages Are Required to Provide Multiple Ecosystem Services. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2016, 218, 87–94. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, V.K.; Giri, A.; Vivek, P.; Kalia, S. Health and Productivity of Dairy Cattle in High Altitude Cold Desert Environment of Leh-Ladakh: A Review. Indian J of Anim Sci 2017, 87. [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, E.; Gakis, N.; Kapetanakis, D.; Voloudakis, D.; Markaki, M.; Sarafidis, Y.; Lalas, D.P.; Laliotis, G.P.; Akamati, K.; Bizelis, I.; et al. Climate Change Risks for the Mediterranean Agri-Food Sector: The Case of Greece 2024.

- Török, P.; Penksza, K.; Tóth, E.; Kelemen, A.; Sonkoly, J.; Tóthmérész, B. Vegetation Type and Grazing Intensity Jointly Shape Grazing Effects on Grassland Biodiversity. Ecology and Evolution 2018, 8, 10326–10335. [CrossRef]

- Kárpáti, T.; Náhlik, A. Is the Impact of the European Mouflon on Vegetation Influenced by the Allochthonous Nature of the Species? Diversity 2023, 15, 778. [CrossRef]

- Biswal, J.; Vijayalakshmy, K.; Rahman, H. Seasonal Variations and Its Impacts on Livestock Production Systems with a Special Reference to Dairy Animals: An Appraisal. vet. sci. res. 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Negi, G.C.S.; Mukherjee, S. Climate Change Impacts in the Himalayan Mountain Ecosystems. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 349–354 ISBN 978-0-12-816097-8.

- Blois, J.L.; Zarnetske, P.L.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Finnegan, S. Climate Change and the Past, Present, and Future of Biotic Interactions. Science 2013, 341, 499–504. [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, P.; Zheng, Z.; Bhatta, K.P.; Adhikari, Y.P.; Zhang, Y. Climate-Driven Plant Response and Resilience on the Tibetan Plateau in Space and Time: A Review. Plants 2021, 10, 480. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, V.; Sirohi, S.; Chand, P. Effect of Drought on Livestock Enterprise: Evidence from Rajasthan. Indian J of Anim Sci 2020, 90, 94–98. [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M.J. A Typology for the Classification, Description and Valuation of Ecosystem Functions, Goods and Services. Ecological Economics 2002, 41, 393–408. [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact on Humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Chapin, F.S.; Ewel, J.J.; Hector, A.; Inchausti, P.; Lavorel, S.; Lawton, J.H.; Lodge, D.M.; Loreau, M.; Naeem, S.; et al. EFFECTS OF BIODIVERSITY ON ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONING: A CONSENSUS OF CURRENT KNOWLEDGE. Ecological Monographs 2005, 75, 3–35. [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.; Gossner, M.M.; Bossdorf, O.; Allan, E.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Prati, D.; Blüthgen, N.; Boch, S.; Böhm, S.; Börschig, C.; et al. Grassland Management Intensification Weakens the Associations among the Diversities of Multiple Plant and Animal Taxa. Ecology 2015, 96, 1492–1501. [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, A.; Hines, J.; Hertzog, L.R.; Lange, M.; Meyer, S.T.; Simons, N.K.; Weisser, W.W. Plant Diversity Effects on Arthropods and Arthropod-Dependent Ecosystem Functions in a Biodiversity Experiment. Basic and Applied Ecology 2018, 26, 50–63. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Schmid, B.; Hautier, Y.; Müller, C.B. Diverse Pollinator Communities Enhance Plant Reproductive Success. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2012, 279, 4845–4852. [CrossRef]

- Barzan, F.R.; Bellis, L.M.; Dardanelli, S. Livestock Grazing Constrains Bird Abundance and Species Richness: A Global Meta-Analysis. Basic and Applied Ecology 2021, 56, 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Wallis De Vries, M.F.; Parkinson, A.E.; Dulphy, J.P.; Sayer, M.; Diana, E. Effects of Livestock Breed and Grazing Intensity on Biodiversity and Production in Grazing Systems. 4. Effects on Animal Diversity. Grass and Forage Science 2007, 62, 185–197. [CrossRef]

- García, R.R.; Peric, T.; Cadavez, V.; Geß, A.; Lima Cerqueira, J.O.; Gonzales-Barrón, Ú.; Baratta, M. Arthropod Biodiversity Associated to European Sheep Production Systems. Small Ruminant Research 2021, 205, 106536. [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Klein, A.M.; Kruess, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Thies, C. Landscape Perspectives on Agricultural Intensification and Biodiversity – Ecosystem Service Management. Ecology Letters 2005, 8, 857–874. [CrossRef]

- Essl, F.; Milasowszky, N.; Dirnböck, T. Plant Invasions in Temperate Forests: Resistance or Ephemeral Phenomenon? Basic and Applied Ecology 2011, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Willem Erisman, J.; Van Eekeren, N.; De Wit, J.; Koopmans, C.; Cuijpers, W.; Oerlemans, N.; J. Koks, B.; 1 Louis Bolk Institute, Hoofdstraat24, 3972 LA Driebergen, The Netherlands Agriculture and Biodiversity: A Better Balance Benefits Both. AIMS Agriculture and Food 2016, 1, 157–174. [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; Clarke, I.J.; DiGiacomo, K.; Chauhan, S.S. Resilience of Small Ruminants to Climate Change and Increased Environmental Temperature: A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 867. [CrossRef]

- Kabubo-Mariara, J. Climate Change Adaptation and Livestock Activity Choices in Kenya: An Economic Analysis. Natural Resources Forum 2008, 32, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Njisane, Y.Z.; Mukumbo, F.E.; Muchenje, V. An Outlook on Livestock Welfare Conditions in African Communities — A Review. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2020, 33, 867–878. [CrossRef]

- Musati, M.; Menci, R.; Luciano, G.; Frutos, P.; Priolo, A.; Natalello, A. Temperate Nuts By-Products as Animal Feed: A Review. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2023, 305, 115787. [CrossRef]

- Chedid, M.; Jaber, L.S.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Duvaux-Ponter, C.; Hamadeh, S.K. Review: Water Stress in Sheep Raised under Arid Conditions. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 94, 243–257. [CrossRef]

- Ragkos, A.; Koutsou, S.; Karatassiou, M.; Parissi, Z.M. Scenarios of Optimal Organization of Sheep and Goat Transhumance. Reg Environ Change 2020, 20, 13. [CrossRef]

- Goetsch, A.L. Recent Research of Feeding Practices and the Nutrition of Lactating Dairy Goats. Journal of Applied Animal Research 2019, 47, 103–114. [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, E.; Roncoroni, C.; Gusmeroli, F.; Della Marianna, G.; Giacometti, G.; Heroldová, M.; Barbieri, S.; Mattiello, S. Feeding Ecology of Alpine Chamois Living in Sympatry with Other Ruminant Species. Wildlife Biology 2016, 22, 78–85. [CrossRef]

- Baronti, S.; Ungaro, F.; Maienza, A.; Ugolini, F.; Lagomarsino, A.; Agnelli, A.E.; Calzolari, C.; Pisseri, F.; Robbiati, G.; Vaccari, F.P. Rotational Pasture Management to Increase the Sustainability of Mountain Livestock Farms in the Alpine Region. Reg Environ Change 2022, 22, 50. [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, J.B.; Sejian, V.; Mader, T.L.; Dunshea, F.R. Adaptation Strategies: Ruminants. Animal Frontiers 2019, 9, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Berihulay, H.; Abied, A.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Adaptation Mechanisms of Small Ruminants to Environmental Heat Stress. Animals 2019, 9, 75. [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.; Nelson, G.; Mayberry, D.; Herrero, M. Increases in Extreme Heat Stress in Domesticated Livestock Species during the Twenty-first Century. Global Change Biology 2021, 27, 5762–5772. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Calvo, J.H.; Calvete, C.; Joy, M.; Lobón, S. Mitigation and Animal Response to Water Stress in Small Ruminants. Animal Frontiers 2023, 13, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.R.R.; Sejian, V.; Silpa, M.V.; Fonsêca, V.F.C.; De Melo Costa, C.C.; Devaraj, C.; Krishnan, G.; Bagath, M.; Nameer, P.O.; Bhatta, R. Goat as the Ideal Climate-Resilient Animal Model in Tropical Environment: Revisiting Advantages over Other Livestock Species. Int J Biometeorol 2021, 65, 2229–2240. [CrossRef]

- Chelotti, J.O.; Martinez-Rau, L.S.; Ferrero, M.; Vignolo, L.D.; Galli, J.R.; Planisich, A.M.; Rufiner, H.L.; Giovanini, L.L. Livestock Feeding Behaviour: A Review on Automated Systems for Ruminant Monitoring. Biosystems Engineering 2024, 246, 150–177. [CrossRef]

- Dias E Silva, T.P.; Abdalla Filho, A.L. Sheep and Goat Feeding Behavior Profile in Grazing Systems. Acta Sci. Anim. Sci. 2020, 43, e51265. [CrossRef]

- Larraz, V.; Barrantes, O.; Reiné, R. Habitat Selection by Free-Grazing Sheep in a Mountain Pasture. Animals 2024, 14, 1871. [CrossRef]

- Kerven, C. Contribution of Goats to Climate Change: How and Where? Pastor. res. policy pract. 2024, 14, 13988. [CrossRef]

- Parsad, R.; Ahlawat, S.; Bagiyal, M.; Arora, R.; Gera, R.; Chhabra, P.; Sharma, U.; Singh, A. Climate Resilience in Goats: A Comprehensive Review of the Genetic Basis for Adaptation to Varied Climatic Conditions. Mamm Genome 2025, 36, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Oltjen, J.W.; Gunter, S.A. Managing the Herbage Utilisation and Intake by Cattle Grazing Rangelands. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2015, 55, 397. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Han, C. Climate Change Is Likely to Alter Sheep and Goat Distributions in Mainland China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 748734. [CrossRef]

- Wehn, S.; Pedersen, B.; Hanssen, S.K. A Comparison of Influences of Cattle, Goat, Sheep and Reindeer on Vegetation Changes in Mountain Cultural Landscapes in Norway. Landscape and Urban Planning 2011, 102, 177–187. [CrossRef]

- Minea, G.; Mititelu-Ionuș, O.; Gyasi-Agyei, Y.; Ciobotaru, N.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Impacts of Grazing by Small Ruminants on Hillslope Hydrological Processes: A Review of European Current Understanding. Water Resources Research 2022, 58, e2021WR030716. [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Lussiana, C.; Malfatto, V.; Mimosi, A.; Battaglini, L.M. Effect of Exposure to Heat Stress Conditions on Milk Yield and Quality of Dairy Cows Grazing on Alpine Pasture. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 9th European IFSA Symposium; 2010; Vol. 4(7), pp. 1338–1348.

- Deléglise, C.; François, H.; Loucougaray, G.; Crouzat, E. Facing Drought: Exposure, Vulnerability and Adaptation Options of Extensive Livestock Systems in the French Pre-Alps. Climate Risk Management 2023, 42, 100568. [CrossRef]

- Koluman Darcan, N.; Silanikove, N. The Advantages of Goats for Future Adaptation to Climate Change: A Conceptual Overview. Small Ruminant Research 2018, 163, 34–38. [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, F.; Provolo, G.; Riva, E.; Caria, M.; Todde, G.; Sara, G.; Cesarini, F.; Grossi, G.; Vitali, A.; Lacetera, N.; et al. Smart Technologies to Improve the Management and Resilience to Climate Change of Livestock Housing: A Systematic and Critical Review. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2025, 24, 376–392. [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Lussiana, C.; Malfatto, V.; Gerbelle, M.; Turille, G.; Medana, C.; Ghirardello, D.; Mimosi, A.; Cornale, P. Evaluating the Suitability of Hazelnut Skin as a Feed Ingredient in the Diet of Dairy Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 1653. [CrossRef]

| Climate change impact |

Description | Effect on animal performance & welfare | Animal species affected |

Reference(s) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | Health | |||||||||||||

| Poor Body Condition Score | Lameness & injuries | High disease prevalence | High mortality & morbidity | Behavioral abnormalities | Reproductive inefficiencies | Coat and skin conditions | Thermal stress (heat/cold) | Painful procedures without | Poor water access/quality | |||||

| Altered plant phenology and forage quality | Decreased nutritional value of pasture affecting health, reproduction, and growth | × | × | × | × | × | × | Grazing livestock (sheep, cattle) |

[78,79,80] | |||||

| Drought and altered precipitation patterns | Reduced forage availability and quality; increased stress and disease vulnerability | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | Grazing livestock | [81,82,83] | ||

| Increased temperatures and CO2 | Reduced protein content in plants; diminished food quality | × | × | × | × | × | × | Wild herbivores and livestock |

[84] | |||||

| Heat stress | Impaired thermoregulation, reduced feed intake, lower productivity, compromised immune function | × | × | × | × | × | × | Cattle, sheep | [85,86,87] | |||||

| Increased parasite burden due to warmer climates | Greater exposure to novel or more persistent parasitic infections | × | × | × | × | × | Grazing livestock | [88] | ||||||

| Declining biodiversity and arthropod populations | Reduced pollination, forage regeneration, and ecological resilience | × | × | Pollinator dung beetles, livestock indirectly | [89,90,91] | |||||||||

| Fodder scarcity and nutritional deficits | Reduced growth, lower milk production, increased disease susceptibility | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | Cattle, sheep | [92,93] | ||||

| Habitat degradation from poor grazing management | Loss of plant diversity and forage quality; higher welfare risks | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | Cattle, sheep | [86,94] | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).