1. Introduction

The molecule of life, DNA is a fascinating material in colloidal science[

1], due to the possibility of programming and reproducing with high accuracy and reliability specific sequences of nucleotides. Since the exact alternation of bases modifies its interaction properties, DNA is currently investigated as a possible building block to control, in a planned way, self-assembly of supramolecular structures [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The phase diagrams of systems made of short fragments of double-strand DNA (duplexes) have been investigated with experimental and theoretical [

6,

7,

8,

12] methods, providing evidence that even short duplexes may display rich and non-trivial phase diagrams. In particular, liquid crystal phases (LC) have been shown to be present even with duplexes as short as six base pairs[

7] (6bp). Moreover, a complete understanding of the interplay between chirality of the duplexes and the presence of chiral mesophases of left and right-handedness oligonucleotides remains a challenge[

6].

Understanding the physical interactions between such duplexes also yields crucial insight into diverse physiological processes—particularly those involving higher-order DNA organization and genome maintenance [

8,

9,

10].

In biological contexts, transient duplex–duplex contacts—mediated by base stacking, electrostatic interactions, and sequence-dependent flexibility—can influence chromatin folding [

8], homologous recombination [

9], and DNA repair mechanisms [

10]. For instance, non-contiguous DNA segments within chromatin often engage in stacking-like interactions that contribute to fiber compaction, nucleosome positioning, and phase separation phenomena linked to the organization of chromatin domains [

8]. During homologous recombination, strand invasion and D-loop formation require transient pairing between homologous sequences, likely stabilized by stacking forces and ionic conditions [

9]. Similarly, accurate recognition and alignment of homologous regions during double-strand break repair rely on short-range DNA–DNA interactions that ensure fidelity [

10].

These interactions—though fleeting and challenging to capture experimentally—are critical for maintaining genome stability and orchestrating the cellular response to DNA damage. Beyond recombination, DNA fragment interactions are involved in a wide array of repair processes, including non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), base excision repair (BER), and nucleotide excision repair (NER), where the recognition, alignment, or bridging of DNA ends or damaged regions are essential.

The possibility of a theoretical understanding of such rich and complex behavior through numerical methods requires realistic modeling of the interactions between fragments of double-strand (ds) DNA. Fully atomistic calculations in the presence of an explicit description of the aqueous solution medium, repeated for many concentrations and thermodynamic states, are still too demanding for the present computational capabilities. However, we note that some investigation on the interactions, based on all-atoms models, has been reported for short (4-bp) dsDNA[

13] and dsRNA[

14] oligomers.

Coarse-grained (CG) interaction models with explicit solvent, somewhat alleviate the computational cost, but not enough for extensive samplings of the thermodynamic phase space, due to the very slow counterion dynamics. Instead, implicit solvent versions of coarse-grained models, can be efficient tools for developing force fields beyond the most primitive models containing only a cylindric excluded volume effect, and an isotropic attraction at short distances.

Although CG models for interactions between biological molecules have been developed over many years, specific CG interactions for DNA have appeared only in the last decades [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] (see a recent review for a comprehensive list[

22]). Most of the existing tests and applications have been restricted to intramolecular interactions, necessary to study phenomena like pairing between complementary single strands or intra-molecular defects. Much less is known about the capabilities of such force-fields to describe the inter-duplex interactions. Still, they are key ingredients for modeling recently proposed DNA-designed colloidal systems. On the one hand, LC phases strongly depend on the effective interactions between duplexes; on the other hand, the analysis of recent experiments [

23,

24] has shown the need for more accurate force-fields, beyond the simplest models, like hard rods decorated with attractive sites[

12].

A first successful and accurate CG model for DNA was proposed in recent years by Pantano and coworkers[

19], who named it SIRAH (South-American Initiative for a Rapid and Accurate Hamiltonian) force field. More recently, other CG models have been presented [

16,

17,

18]. In some cases, they differ for the level of coarse-graining; in other cases, the choice between comparable levels of coarse graining may be driven by differences in the accuracy of reproducing some physical properties or by practical considerations related to the level of integration in various molecular dynamics packages or with other force fields.

In the present paper, we have studied the energy landscape and the resulting forces between two short duplexes of DNA described by SIRAH force field. We have calculated energy and force on the two double-strands of size 8bp and 20bp for a representative set of configurations in the implicit solvent approach (i.e., in an approach such that the effect of the ionic solution is fully absorbed into modifications of the bare DNA-DNA interactions). For a small subset of configurations, we have also performed a few calculations with the explicit solvent model where water and salt ions are treated at the same coarse-grained level of the DNA. These calculations were only intended to provide a first assessment about the spatial extension of the modulation of the solvent density around the duplexes. The present results will help to develop new rigid duplex-duplex interaction models, suitable for extensive numerical simulations of phase diagrams.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we briefly describe the force field model and how we have used it in our calculations. In

Section 3, we present our detailed analysis of the energy landscape and forces. In the final section, we have collected a short summary and a few comments on our results.

2. Methods

Numerical simulation of DNA is a complex challenge. Space scales go from interatomic distances within their constituent molecules to macroscopic lengths (of the order of one meter) for the unswelled double helix of human DNA[

19]. Similarly, time-scales of all the possible dynamical processes span more than twenty decades. Thus, rather than a unique modeling strategy, it has been recognized useful to develop several methods, each adapted to a particular level of resolution, going from quantum chemistry accuracy (molecular level) to elastic mesoscopic models, passing through mixed Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics, atomistic and coarse-grained levels of description.

Particle-based coarse-grained (CG) models are based on replacing groups of multiple atoms by effective beads interacting in such a way to maintain the geometry of the original groups (see ref. [

25] for a comprehensive review). Models differ in the number of atoms represented by a single bead. If combined with a similar CG modeling of the solvent, particle CG models can be quite useful in strongly reducing the number of independent degrees of freedom, while keeping good accuracy in the description of geometries and energy. DNA is clearly a molecule suitable for CG modeling and different research groups have developed CG models for numerical simulations [

26]. Among different CG models, the SIRAH force field[

19] looks an interesting model, flexible enough to be used in combination with explicit or implicit solvent description and accurate enough to be considered a possible benchmark for more approximate model Hamiltonian.

The SIRAH force field for DNA uses six beads for each nucleic base. Each bead is at the same position as an atom in the atomistic reference structure, thus allowing to reconstruct quite easily the atomic positions if required. A partial electrostatic charge is added to the beads so that each nucleotide carries a unitary negative charge to ensure Watson-Crick electrostatic recognition. Moreover, the resulting electric dipole distribution is compatible with all-atoms models [

19]. The model also retains the identity of minor and major grooves, as well as the 5

′ to 3

′ directionality of DNA helices. In addition to the electrostatic term, bead-bead interactions include[

19]: i) a harmonic bond-stretching term, ii) a harmonic angle-stretching term, iii) a dihedral torsional barrier, and iv) an effective 12−6 Lennard-Jones interaction, which is mainly responsible, through its repulsive part, for bead-bead (and in turn nucleotide-nucleotide and finally DNA-DNA) excluded volume effects. Parameters for bead-bead interactions are listed in the original paper[

19].

Within the SIRAH model, the solvent can be treated at two different levels. The implicit solvent level [

16] takes care of hydration and ionic presence effects through the Generalized Born model[

27], while the explicit solvent model restores the presence of solvent and ionic degrees of freedom through a coarse grained description of water molecules (WAT FOUR)[

28] and hydrated ions. In WAT FOUR, groups of 11 water molecules are represented by a group of four tetrahedrally interconnected beads, hence the name WAT FOUR (WT4). Since each bead carries an explicit partial charge, WT4 liquid generates its own dielectric permittivity without the need to impose a uniform dielectric medium. The model reproduces several common properties of liquid water and simple electrolyte solutions[

28]. Similarly, each group made by a cation (Na

+,K

+,Ca

++) plus its hydration sphere is modeled by a CG molecule. A complete list of all parameters can be found in the original paper[

28]. The CG model for the solvent was extensively tested by its authors. Taking into account the intrinsic limitations of a CG model where each bead represents 11 water molecules, it provides a satisfactory overall description of the properties of water as compared with results obtained by using well established atomic models (TIP4P, SPC)[

28].

The solvated ions are represented by CG particles corresponding to a central ion surrounded by six water molecules always attached to them (i.e., roughly considering an implicit first solvation shell). Therefore, their masses are the sum of the ionic mass plus that of six water molecules. Partial charges are set to unitary values. The van der Waals radii are adapted to match the first minima of the radial distribution function (RDF, also known as g(r)) of hydrated ions as obtained from neutron diffraction experiments. The well depths have the same values as in the WT4 beads. This ensures that, when a WT4 molecule touches a CG ion, it interacts implicitly with its first solvation shell.

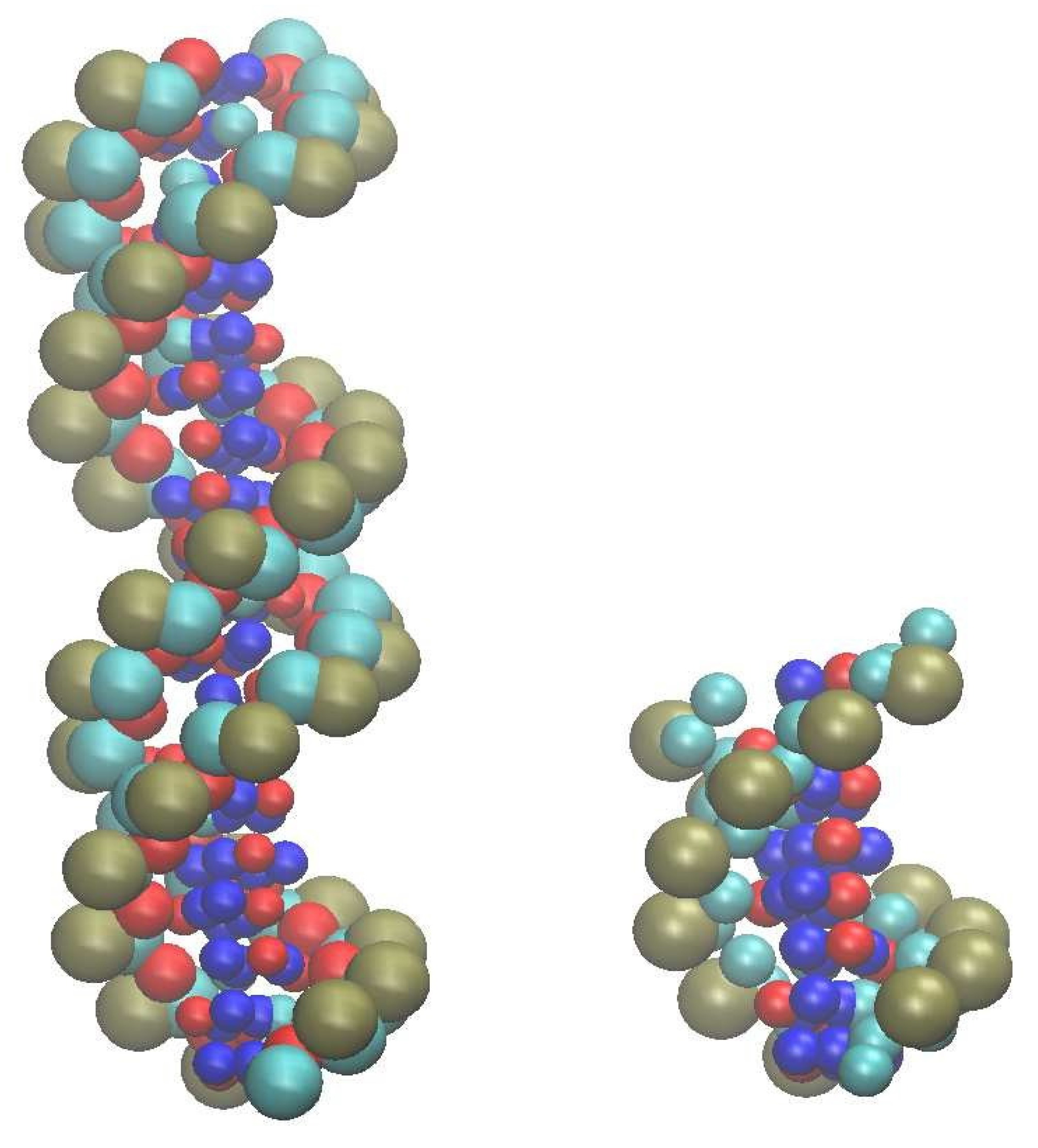

All our calculations have been performed for an isolated pair of each of the two short duplexes (20 base pairs (bp) and 8 bp-long double stranded (ds) DNA). Their SIRAH coarse-grained representation is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The 20-mer duplex is based on the sequence 5′ -(C1A2T3G4C5A6T7G8C9A10T11G12C13A14-

T

15G

16C

17A

18T

19G

20 )-3

′ , indicated as S

AA2 by Machado et al.[

20]. The shorter 8 bp duplex corresponds to the first 8 nucleotides of the 20-mer. Its choice was motivated by the possibility of having the same terminal bases at both ends of the double strand. In all cases the model building procedure starts from the Cartesian coordinates of structures containing all the atoms, built in the canonical B-form of DNA33 using the NAB utility of AMBER[

29,

30], and then the SIRAH scheme is used for mapping from atomic level to CG level nucleobases by simply removing and renaming the corresponding atoms. All the bonding parameters used in the model are contained in Table 1 and Table 2 of the original description of the force field[

19].

As anticipated in the introduction, the main aim of the present study has been to obtain information about the SIRAH energy landscape of duplex-duplex interaction in the case of two isolated duplexes at fixed structure of the duplex. Such constraint is quite artificial, since the real interaction between helices certainly implies some atomic relaxations. However, we are mainly interested in the asymmetric deviations from a rigid model with cylindric symmetry due to the three-dimensional structure of the double helix. For such an aim, a rigid model of the double helix should be sufficient.

To understand the extent the solvent is perturbed by the presence of the duplexes, we also performed some calculations with the explicit solvent model. In this case, water CG molecules and hydrated CG ions were chosen to simulate a 1M aqueous solution of NaCl. The simulation cell was a truncated octahedron to optimize the number of solvent particles[

31]. The volume was 426.1 nm

3. In the case of explicit solvent calculations, the simulation box for the two 20-mer case contained 6036 coarse-grained particles. In addition to the two DNA duplexes, there were 1431 coarse-grained water molecules groups, 76 hydrated sodium ions and 48 hydrated chloride ions. Coarse-grained water molecules were described by the so-called WAT FOUR model[

28]. Molecular dynamics calculations were performed with GROMACS package[

32].

In the case of implicit solvent calculations, an extensive sampling of configurations of the system has been performed, varying distance, mutual orientations and salt concentration. Hydration and ionic strength effects are implicitly taken into account, through their effect on electrostatic interactions using the generalized Born (GB) model[

27] for implicit solvation as implemented in AMBER[

29,

30]. The Born effective radii were fixed to 0.15 nm for all superatoms. The maximum distance between atom pairs considered in the pair-wise summation involved in calculating the effective Born radii is set to 1 nm. Non-bonded interactions are calculated up to a cutoff of 8.6 nm within the GB approximation and the salt concentration varies from 0.15 M to 2.0 M.

Tests on the dependence of results on the choice of the cutoff show that calculations with a cutoff at 4.8 nm can be considered already close to numerical convergence and this is the value used in all the calculations. We also checked that this cutoff ensures a smooth behavior of forces for all the configurations of the present study.

3. Results

3.1. Duplex-Duplex Interaction

Calculations with the implicit solvent model are straightforward. Among the many different configurations we have studied, here we discuss a representative set to illustrate the main features of the inter-duplex interactions.

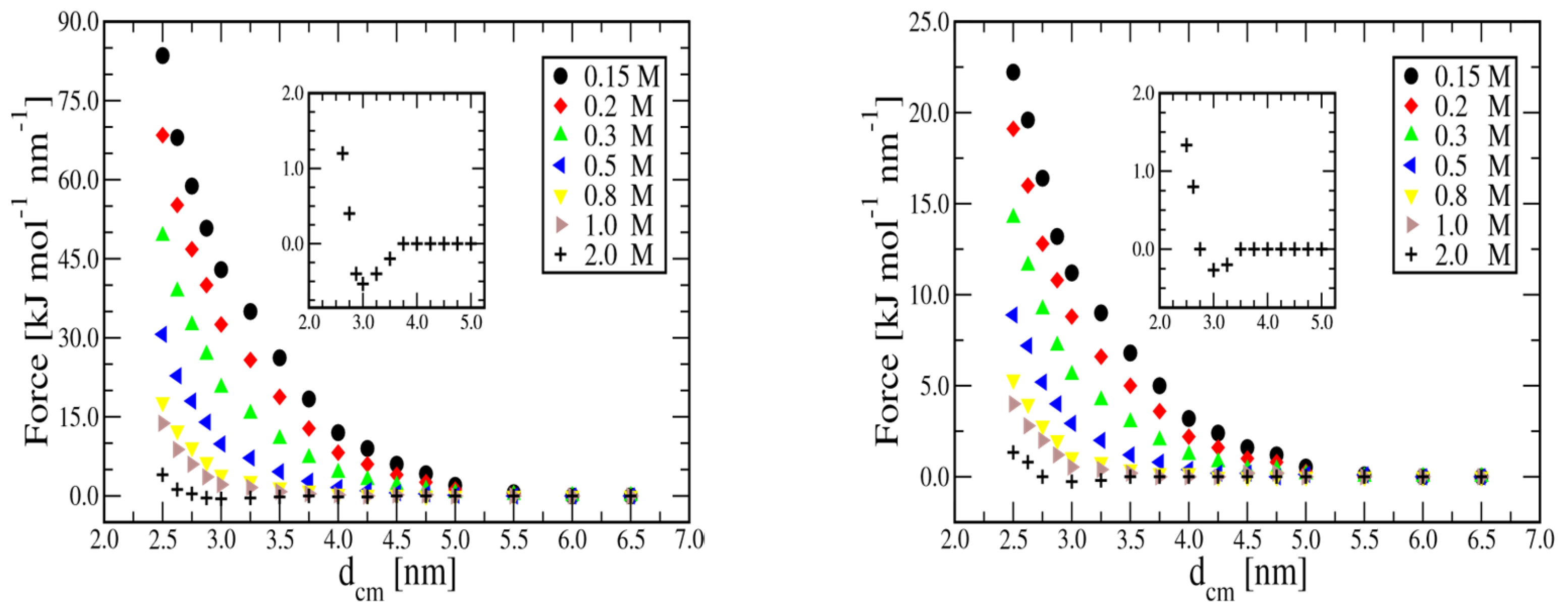

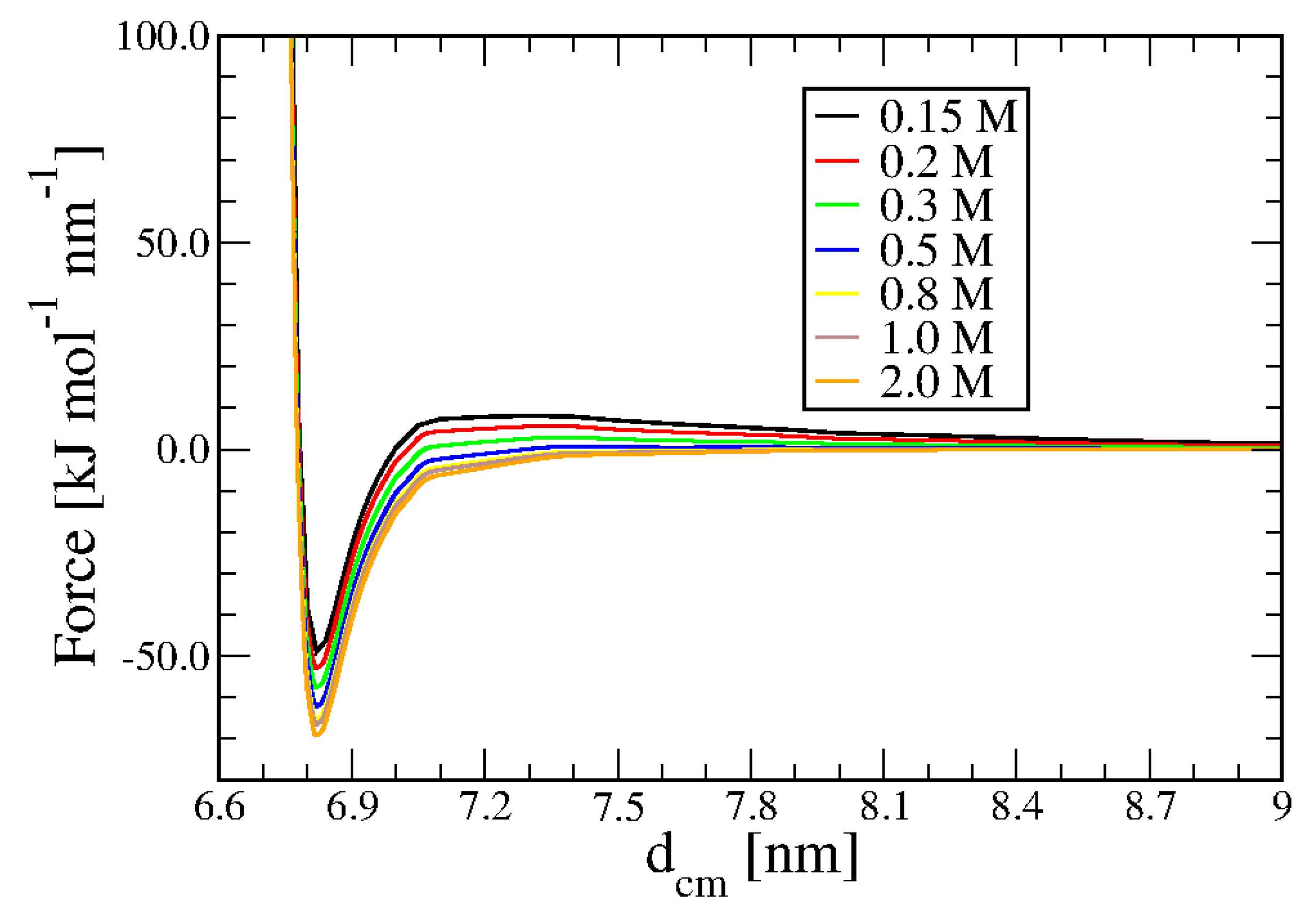

In

Figure 2 we see the variation of the inter-duplex total force between two 20bp (left panel) and two 8bp (right panel) dsDNA helices at salt concentration ranging from 0.15M to 2.0M.

As expected, by increasing the salt concentration, screening of the Coulomb interaction becomes increasingly effective, reducing the strength and range of the repulsion significantly. In all cases, repulsions are quite short-range, and even for the 0.15M case, they become negligible beyond 5.5 nm. More important, at 2M concentration, a small attraction appears with both the duplexes. In the insets of

Figure 2, the effect is shown on an enlarged scale.

In the presence of multivalent-ion in solution, the possibility of a range of attractive interactions is well established in experiments and computer simulation[

33,

34,

35]. Less is known for the case of mono-valent ions, although recent numerical simulations[

36] predict the effect even for NaCl at concentrations higher than 1M. Interestingly, the implicit solvent method reproduces such behavior. Experiments on the interaction at high NaCl concentration could provide a direct check for such a prediction.

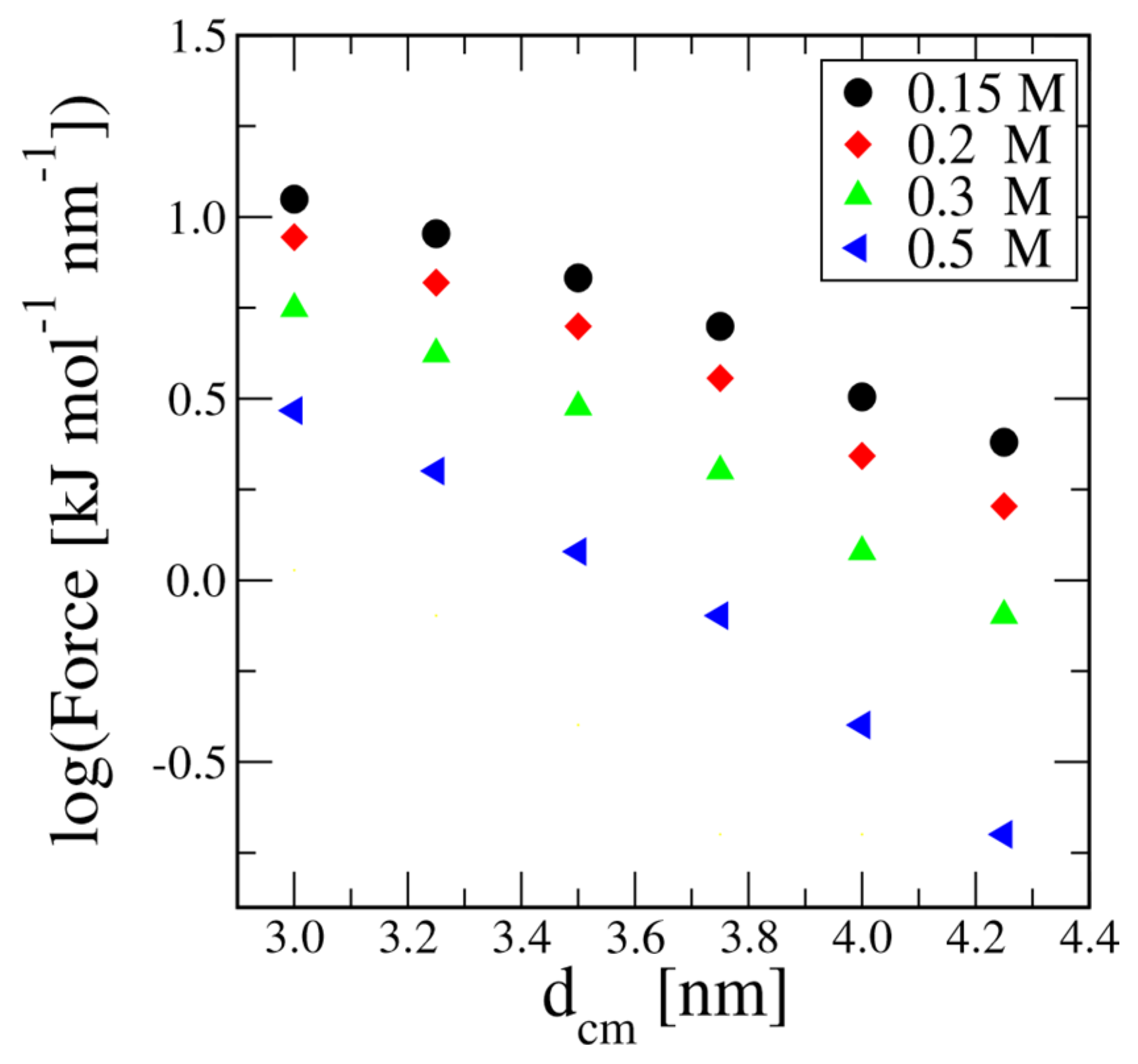

An analysis of the force in the logarithmic scale (see

Figure 3), allows comparison with the experimental data analyzed by Podgornik et al.[

37] in the same range of distances. Their main conclusion was that the interactions at distances below 3 nm are influenced by solvent layering effects, while for larger distances, at least up to 3.5 nm, the repulsion is almost exponential with a decaying length depending on salt concentration. In the implicit solvent model, there is no direct modeling of the solvent; therefore we observe a reasonably accurate exponential decay of the interactions starting from about 2.5 nm. Interestingly, the implicit solvent model parameters take care of the salt concentration effect, resulting in a concentration-dependent repulsion with screening length which reasonably compares with the values obtained by Podgornik et al.[

37] from the direct analysis of experimental data. Indeed, between 0.15 M and 0.5M we find decaying lengths ranging from 1.63 nm to 1.23 nm, while Podgornik et al.[

37] in their table 1, provide values going from 1.32 nm at 0.2M to 0.76 nm at 0.6 M.

We have evaluated the anisotropy of the side-by-side interaction between two parallel duplexes. In agreement with “primitive model” calculations [

38] and the theoretical predictions by Kornyshev and Leikin[

39,

40], we find a rapidly decaying dependence of the interaction energy on the mutual azimuthal angle. According to Kornyshev and Leikin[

39,

40], the dominant dependence of the interaction energy on the azimuthal angle should be of the form

E = E0(1+ α cos(φ − φ0)).

(1)

Already at an inter-duplex distance of 2.4 nm such a dependence is able to provide a very good description of the angular dependence with an azimuthal modulation amplitude α as small as 0.04, reducing to 0.01 at a distance of 4.0 nm and becoming negligible at 7.0 nm.

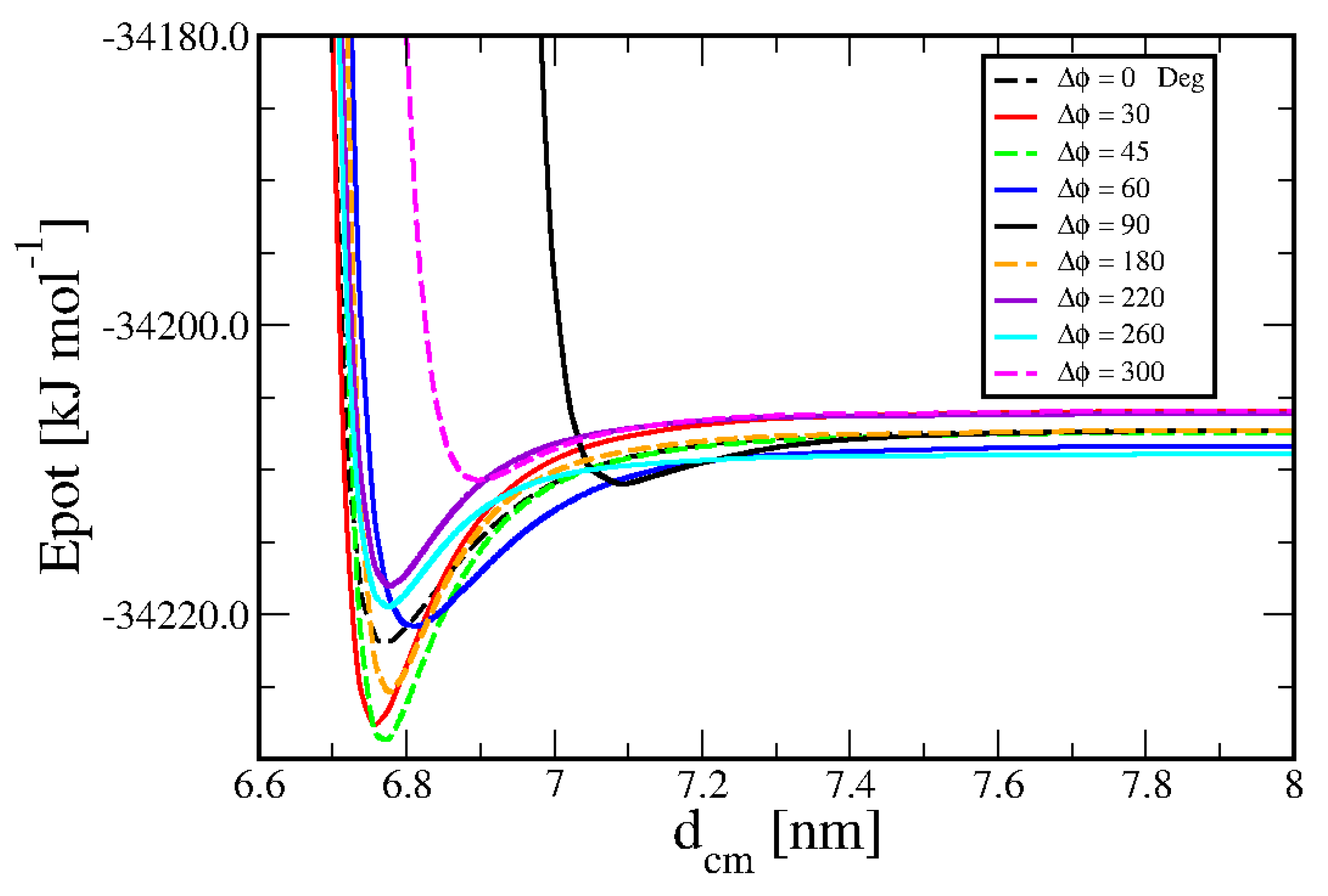

The head-tail interaction plays an important influence on the possible phase diagrams of short duplexes systems[

6]. Moreover, the possibility and the conditions for end-to-end DNA association have been less studied in the literature than side-by-side interactions. Depending on the presence or not of a head-tail attraction, it would be possible to favor liquid crystal phases or even reversible chaining between duplexes.

Figure 4 shows that there is an important angular dependence of such an attraction, which is strongly reduced at some angles. The main message from these calculations is again that the real three-dimensional interaction between duplexes could be approximated with cylindrically symmetric models only at a crude level.

Figure 5 is an example of the variation of the head-tail force between two aligned 20pb duplexes, as a function of concentration. The effect of adding salt in the range from 0.15

M to 2

M is a consistent increase in attractive force of approximately 40%.

Finally,

Figure 6 demonstrates the dependence of the interaction energy on the distance of the molecular axes, in a consecutive head-tail configuration of two 20bp duplexes. Displacement ∆

x = 0 means that the two duplexes are aligned. As it can be seen by the curves, even a slight deviation from axial alignment results in a strong reduction of the attractive force.

These interaction features can be interpreted in terms of known biochemical forces. In particular, the strong axial dependence of the head-to-tail association may reflect contributions from base stacking interactions between exposed termini.

Furthermore, the angular dependence observed in both lateral and axial geometries is consistent with the anisotropic electrostatic potential generated by the helical charge distribution, especially the alignment (or misalignment) of major and minor grooves.

This azimuthal sensitivity is in good agreement with theoretical models that describe electrostatic groove recognition and directional specificity in DNA–DNA interactions [

39,

40].

3.2. Effects of the Solvent Density

To check explicitly how much the solvent density is perturbed by the presence of the duplexes, we also performed some calculations with the explicit solvent model. We have averaged the system over times to exceed 300 ns, reaching up to 1 µs, in a few cases. Although simulation times were long enough to reach a good equilibration of the solvent, it turned out very difficult to obtain a reasonable equilibration of the counterions. As it is well known, sodium cations tend to stick in the major grooves of the double helix and the coarse grained hydrated sodium ions of the SIRAH model nicely reproduce such behavior. However, the strength of attraction results in very long residence times. During our simulations, the average residence time of the hydrated sodium atoms adsorbed on the duplex can be estimated to exceed 300 ns, which means that even the longest runs corresponding to 1 µs provide quite a poor statistics of the ionic configurations.

Nevertheless, even if such difficulty of a good statistical sampling prevented to obtain quantitative data on the interactions to be compared with the implicit solvent calculations, we notice that the quite noisy averages we obtained are compatible with the results for the implicit solvent model. Furthermore, reliable results for the average solvent density around the duplexes could be obtained.

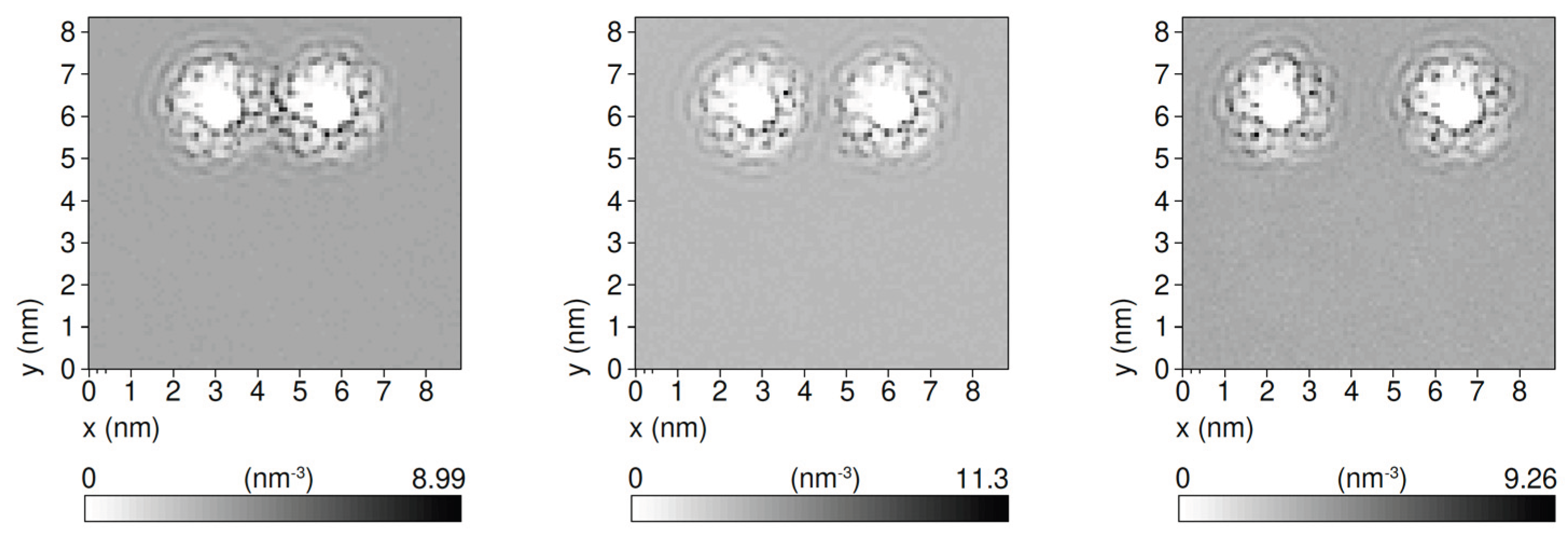

We present in

Figure 7 the average density of CG water molecules in a slab of 2 nm perpendicular to the axes of two parallel 8bp double strands. The density values are represented by using a grey-scale code (darker grey means higher density) for three distances between duplexes.

A clear modulation of the CG water profile is visible, extending around each duplex on a radial length scale of about 1 nm. The absence of density fluctuations far from the two duplexes is a measure of the good equilibration of the pure solvent. Although the previously mentioned ergodicity problems, related to the counterions, make it difficult to get a direct, reliable quantitative estimation of the effect on duplex-duplex interaction, it is reasonable to expect that such solvent modulation could have qualitative effects on the DNA-DNA interaction which are not presently included in the implicit interaction models. We believe this is an interesting area for future investigations.

The density modulations observed in the explicit solvent simulations are qualitatively compatible with hydration structuring effects previously reported in atomistic simulations and scattering studies [

41]. In particular, water layers confined in the minor and major grooves of DNA show slow relaxation dynamics, which may influence duplex-duplex interactions at short range.Our model also captures strong binding of Na⁺ ions within the major groove, with residence times exceeding 300 ns. This behavior is consistent with experimental and computational evidence for long-lived cation localization near phosphate and groove regions [

42]. These features suggest that the implicit solvent model indirectly includes part of these effects through effective screening parameters.

4. Discussion

We have presented a numerical study of the SIRAH CG model energy landscape for the interaction of two short duplexes of DNA with implicit solvation. The main aim of the present study was to use a quite refined CG model to go beyond the simplest decorated hard-cylinder models to study condensed phases of DNA double strands and simulate properties of DNA-based colloids. We hope that our study, based on an accurate CG model, could help to build intuition about some features missing in the crudest approximations. Our results are in agreement with the theoretical understanding of the DNA-DNA interaction[

37]. The presence of modulations in the solvent density between two duplexes is expected to have some effect on the short-range interaction.

The implicit solvent calculations of the present study have provided thorough information about the characteristics of duplex-duplex interactions, required to improve on the simplest, rigid cylindrically symmetric models of short DNA duplexes. In particular, we have found an important dependence on salt concentration, with indication of a possible lateral attraction above 2M. Dependence on azimuthal rotation of parallel configurations is coherent with theoretical predictions, and its repulsive nature implies that averaging interactions over the angle should result in a larger effective size of double strands. Head-tail interactions, critical ingredients for the possibility of LC phases, are quite sharply concentrated along the molecular axis and strongly depend on the relative azimuthal angle. This last fact implies that once a chain of duplexes is formed, relative rotations of individual duplexes are strongly suppressed. On the other hand, such angular dependence may act as an additional kinetic constraint for chain formation. Salt concentration plays an important role, with the possible development of a weak lateral attraction at the highest concentrations.

From our calculations, we can also draw some conclusions about the SIRAH force-field. The observed screening lengths in the implicit model align with experimental osmotic stress data on DNA–DNA repulsion [

43], and the anisotropic interaction profiles agree with theoretical predictions [

39,

40]. Furthermore, hydration-shell structuring and slow water dynamics—characterized in atomistic simulations [

41]—are qualitatively consistent with the solvent density modulations we observe in explicit simulations.Also, the long-lived localization of Na⁺ ions in the grooves, seen in our coarse-grained runs, matches with NMR and crystallographic studies showing strong electrostatic stabilization effects [

42].These parallels suggest that SIRAH-based calculations capture not only structural geometry but also essential physicochemical mechanisms governing DNA–DNA association.

The picture obtained from our analysis aims to be a solid starting point for future progress in developing simplified yet physically meaningful interaction models to study condensed phases and phase diagrams of small duplexes and DNA-coated colloids. We anticipate that these findings will guide the design of new coarse-grained potentials and inspire experimental validation in high-salt regimes, potentially informing biological studies impacting DNA compaction and molecular recognition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R., E.S. and G.P.; methodology, R.R.; software, R.R.; validation, R.R., E.S. and G.P.; formal analysis, R.R.; investigation, R.R.; resources, G.P.; data curation, R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, R.R., E.S. and G.P.; project administration, G.P.; funding acquisition, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MIUR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

R.R. thanks S. Pantano for useful discussions. The authors dedicate this paper to the memory of Rudi Podgornik. Without his interest, encouragement, and useful discussions, this research would not have reached its conclusion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LC |

Liquid crystal |

| bp |

Base pairs |

| ds |

Double strand |

| CG |

Coarse-grained |

| SIRAH |

South-American Initiative for a Rapid and Accurate Hamiltonian |

References

- Pedersen, R. et al., Properties of DNA, In Handbook of nanomaterials properties. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1125-1157. [CrossRef]

- 2. Hendrikse, S. I., Gras, S. L., Ellis, A. V. Opportunities and challenges in dna-hybrid nanomaterials, ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8512-8516.

- Linko, V., Dietz, H. The enabled state of dna nanotechnology, Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2013, 24, 555-561.

- Bath, J., Turberfield, A. J. Dna nanomachines, Nature Nanotechnology 2007, 2, 275-284.

- Liedl, T., Sobey, T. L., & Simmel, F. C. DNA-based nanodevices, Nano Today 2007, 2, 36-41.

- Bellini, T., Cerbino, R., Zanchetta, G. DNA-based soft phases, in Liquid Crystals. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 225–279.

- De Michele, C., Bellini, T., Sciortino, F., Self-assembly of bifunctional patchy particles with anisotropic shape into polymers chains: theory, simulations, and experiments, Macromolecules 2012, 45, 1090-1106.

- Woodcock, C.L., Ghosh, R.P., Chromatin higher-order structure and dynamics. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2010, 2, a000596.

- San Filippo, J., Sung, P., Klein, H., Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 2008, 77, 229–257.

- Jackson, S. P., & Bartek, J.. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature, 2009, 461, 1071–1078.

- Nguyen, K. T., Sciortino, F., De Michele, C. Self-assembly-driven nematization, Langmuir 2014, 30, 4814-4819.

- De Michele, C., Rovigatti, L., Bellini, T., Sciortino, F. Self-assembly of short dna duplexes: from a coarse-grained model to experiments through a theoretical link, Soft Matter 2012, 8, 8388-8398.

- Saurabh, S., Lansac, Y., Jang, Y. H., Glaser, M. A., Clark, N. A., Maiti, P. K. Understanding the origin of liquid crystal ordering of ultrashort double-stranded dna, Physical Review E 2017, 95, 032702.

- Naskar, S., Saurabh, S., Jang, Y. H., Lansac, Y., Maiti, P. K. Liquid crystal ordering of nucleic acids, Soft Matter 2020, 16, 634-641.

- Savelyev, A., Papoian, G. A. Chemically accurate coarse graining of double-stranded dna, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 20340-20345.

- Uusitalo, J. J., Ingólfsson, H. I., Akhshi, P., Tieleman, D. P., & Marrink, S. J. Martini coarse-grained force field: extension to dna, Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2015, 11, 3932-3945.

- Ouldridge, T. E., Louis, A. A., Doye, J. P. Structural, mechanical, and thermodynamic properties of a coarse-grained dna model, The Journal of chemical physics 2011, 134, 025101.

- Doye, J. P., Ouldridge, T. E., Louis, A. A., Romano, F., Šulc, P., Matek, C., Snodin, B. E., Rovigatti, L., Schreck, J.S., Harrison, R. M., Smith, W. P. Coarse-graining dna for simulations of dna nanotechnology, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15, 20395-20414.

- Dans, P. D., Zeida, A., Machado, M. R., Pantano, S. A coarse grained model for atomic detailed dna simulations with explicit electrostatics, Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2010, 6, 1711-1725.

- Machado, M. R., Dans, P. D., & Pantano, S. A hybrid all-atom/coarse grain model for multiscale simulations of dna, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2011, 13, 18134-18144.

- Dans, P. D., Darré, L., Machado, M. R., Zeida, A., Brandner, A. F., & Pantano, S. (2013, November). Assessing the accuracy of the SIRAH force field to model DNA at coarse grain level. In Brazilian Symposium on Bioinformatics Lecture Notes in Computer Science Advances in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology). Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland; 2013; pp. 71–81. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02624-4_7.

- Noid, W. G. Perspective: Coarse-grained models for biomolecular systems, The Journal of Chemical Physics 2013, 139, 090901.

- Zanchetta, G., Giavazzi, F., Nakata, M., Buscaglia, M., Cerbino, R., Clark, N. A., Bellini, T. Right-handed double-helix ultrashort dna yields chiral nematic phases with both right-and lefthanded director twist, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 17497-17502.

- Frezza, E., Tombolato, F., Ferrarini, A. Right-and left-handed liquid crystal assemblies of oligonucleotides: phase chirality as a reporter of a change in non-chiral interactions?, Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9291-9296.

- Zhou, J., Thorpe, I. F., Izvekov, S., Voth, G. A. Coarse-grained peptide modeling using a systematic multiscale approach, Biophysical Journal 2007, 92, 4289-4303.

- Potoyan, D. A., Savelyev, A., Papoian, G. A., Recent successes in coarse-grained modeling of dna, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2013, 3, 69-83.

- Hawkins, G. D.; Cramer, C. J.; Truhlar, D. G. Parametrized models of aqueous free energies of solvation based on pairwise descreening of solute atomic charges from a dielectric medium, The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1996, 100, 19824-19839.

- Darré, L., Machado, M. R., Dans, P. D., Herrera, F. E., Pantano, S. Another coarse grain model for aqueous solvation: WAT FOUR?, Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2010, 6, 3793-3803.

- Pearlman, D. A., Case, D. A., Caldwell, J. W., Ross, W. S., Cheatham III, T. E., DeBolt, S., Ferguson, D., Seibel, G., Kollman, P. Amber, a package of computer programs for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics and free energy calculations to simulate the structural and energetic properties of molecules, Computer Physics Communications 1995, 91, 1-41.

- Case, D. A., Cheatham III, T. E., Darden, T., Gohlke, H., Luo, R., Merz Jr, K. M., Onufriev, A., Simmerling, C. , B. Wang, B. , Woods, R. J. The amber biomolecular simulation programs, Journal of Computational Chemistry 2005, 26, 1668-1688.

- M. P. Allen and D. J. Tildesley, Computer Simulation of Liquids, 2nd ed.; Oxford university press: Oxford, UK; 2017.

- Berendsen, H. J., van der Spoel, D., van Drunen, R., Gromacs: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation, Computer Physics Communications 1995, 91, 43-56.

- Dai, L., Mu, Y., Nordenskiöld, L., van der Maarel, J. R. Molecular dynamics simulation of multivalent-ion mediated attraction between dna molecules, Physical Review Letters 2008, 100, 118301.

- Kanduč, M., Dobnikar, J., Podgornik, R. Counterion-mediated electrostatic interactions between helical molecules, Soft Matter 2009, 5, 868-877.

- Andresen, K., Qiu, X., Pabit, S. A., Lamb, J. S., Park, H. Y., Kwok, L. W., Pollack, L. Mono and trivalent ions around dna: a small-angle scattering study of competition and interactions, Biophysical Journal 2008, 95, 287-295.

- Maffeo, C., Luan, B., Aksimentiev, A. End-to-end attraction of duplex dna, Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40, 3812-3821.

- Podgornik, R., Rau, D. C., Parsegian, V. A. Parametrization of direct and soft steric undulatory forces between dna double helical polyelectrolytes in solutions of several different anions and cations, Biophysical Journal 1994, 66, 962-971.

- Allahyarov, E., Löwen, H. Effective interaction between helical biomolecules, Physical Review E 2000, 62, 5542.

- Kornyshev , A. A., Leikin, S. Theory of interaction between helical molecules, The Journal of Chemical Physics 1997, 107, 3656- 3674.

- Kornyshev, A. A., Leikin, S. Electrostatic interaction between long, rigid helical macromolecules at all interaxial angles, Physical Review E 2000, 62, 2576.

- Duboué-Dijon, E., Fogarty, A. C., Hynes, J. T., Laage, D. Dynamical Disorder in the DNA Hydration Shell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7610–7620. [CrossRef]

- Hud, N. V., Polak, M. DNA-Cation Interactions: The Major and Minor Grooves Are Flexible Ionophores. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 293–301. [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, R., Rau, D. C., Parsegian, V. A. Direct Measurements of DNA-DNA Interactions. Biophys. J. 1994, 66, 962–971. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).