Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. History and Development of FFF 3D Printing

3. Basic Characteristics of Thermoplastics Used in FFF

| Material | Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Young’s Modulus (MPa) |

Elongation at Break (%) |

Flexural Strength (MPa) |

Extrusion Temperature (°C) |

Printing Speed (mm/s) |

Layer height (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle of the print fibers to the test direction: 0° | |||||||

| PLA | 53 – 72.3 | 2451 – 3769 | 4.1 – 5.8 | – | 200 – 220 | 50 – 70 | 0.15 – 0.25 |

| ABS | 25 – 39 | 1140 – 1885 | 3.6 – 9.5 | 47 | 250 – 255 | 80 – 300 | 0.15 – 0.20 |

| PETG | 33 – 54 | 1110 – 2280 | 3.2 – 10.5 | – | 195 – 240 | 50 – 80 | 0.20 – 0.25 |

| Angle of the print fibers to the test direction: ± 45° | |||||||

| PLA | 48 – 60 | 1102– 1346 | 5.2 – 8.1 | 97 | 190 – 230 | 40 – 300 | 0.20 |

| ABS | 31 – 44 | 1030 – 1610 | 2.8 – 8.4 | – | 220 – 260 | 65 – 300 | 0.15 – 0.20 |

| PETG | 30 – 51 | 906 – 1800 | 7.4 – 8.1 | 35– 70 | 190 – 270 | 30 – 300 | 0.20 |

3.1. Polylactic Acid (PLA)

3.1.1. Mechanical Characteristics of Pure PLA for FFF Applications

3.1.2. FFF Processing Behavior of Pure PLA

3.1.3. Thermal Aging and Degradation Pathways of PLA

3.1.4. UV Radiation Effects (Photodegradation)

3.2. Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS)

3.2.1. Mechanical Characteristics of Pure ABS for FFF Applications

3.2.2. FFF Processing Behavior of Pure ABS

3.2.3. Thermal Aging and Degradation Pathways of ABS

3.2.4. UV Radiation Effects (Photodegradation) ABS

3.3. Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG)

3.3.1. Mechanical Characteristics of Pure PETG for FFF Applications

3.3.2. FFF Processing Behavior of Pure PETG

3.3.3. Thermal Aging and Degradation Pathways of PETG

3.3.4. UV Radiation Effects (Photodegradation) PETG

4. The Effect of Fiber Reinforcement on the Performance of FFF Composites

4.1. FFF Composites with Synthetic Fibers (Carbon, Glass, Aramid)

4.1.1. Governing Principles of Synthetic Fiber Reinforcement in FFF

4.1.2. Carbon Fiber (CF) Reinforced Composites

4.1.3. Glass Fiber (GF) Reinforced Composites

4.1.4. Aramid Fiber Reinforced Composites

4.1.5. Comparative Analysis and Overarching Challenges

4.2. FFF Composites with Natural Fibers (Wood, Flax, Hemp, Jute)

4.2.1. Wood-Plastic Composites (WPCs)

4.2.2. Flax-Reinforced Composites

4.2.3. Hemp-Reinforced Composites

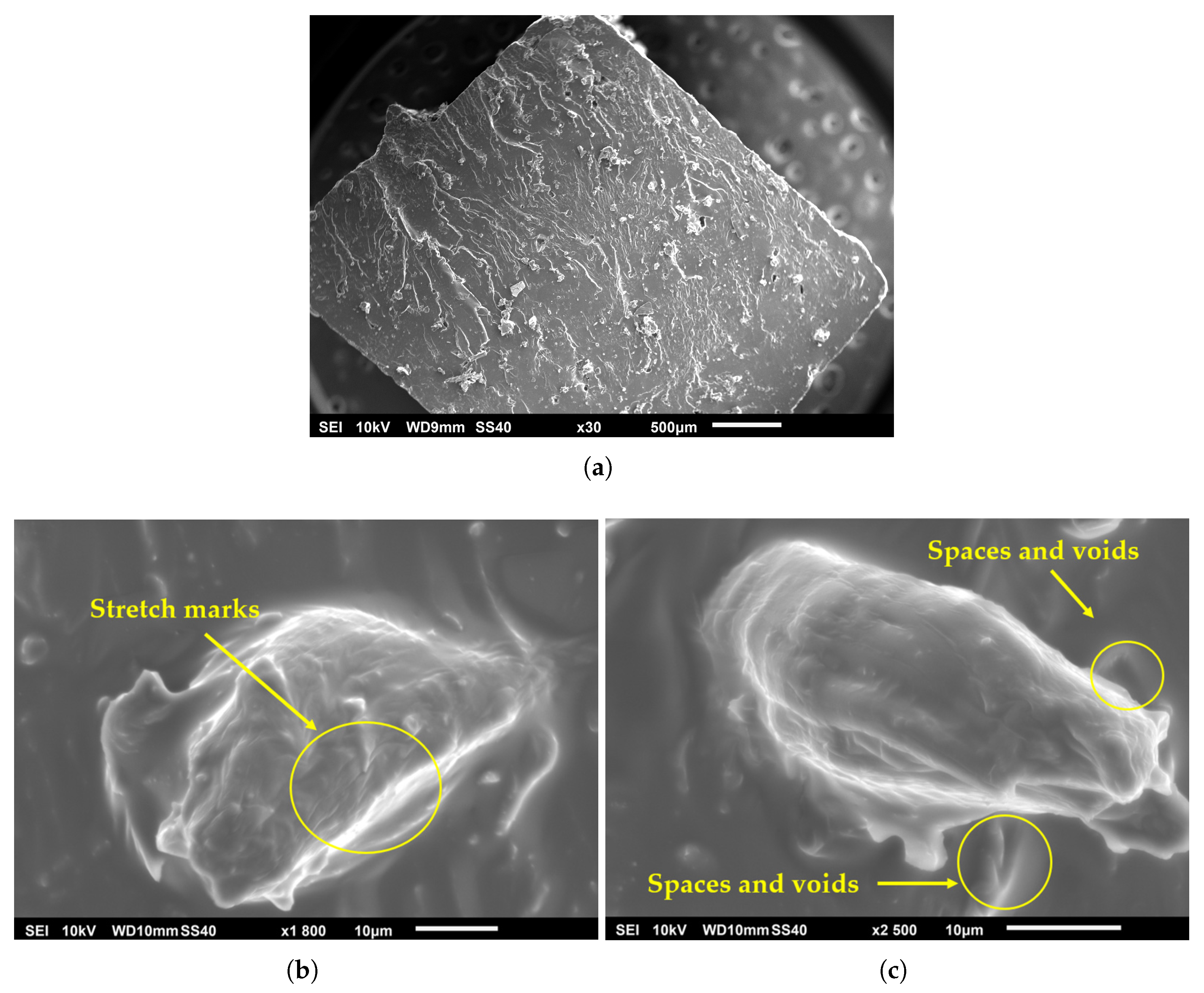

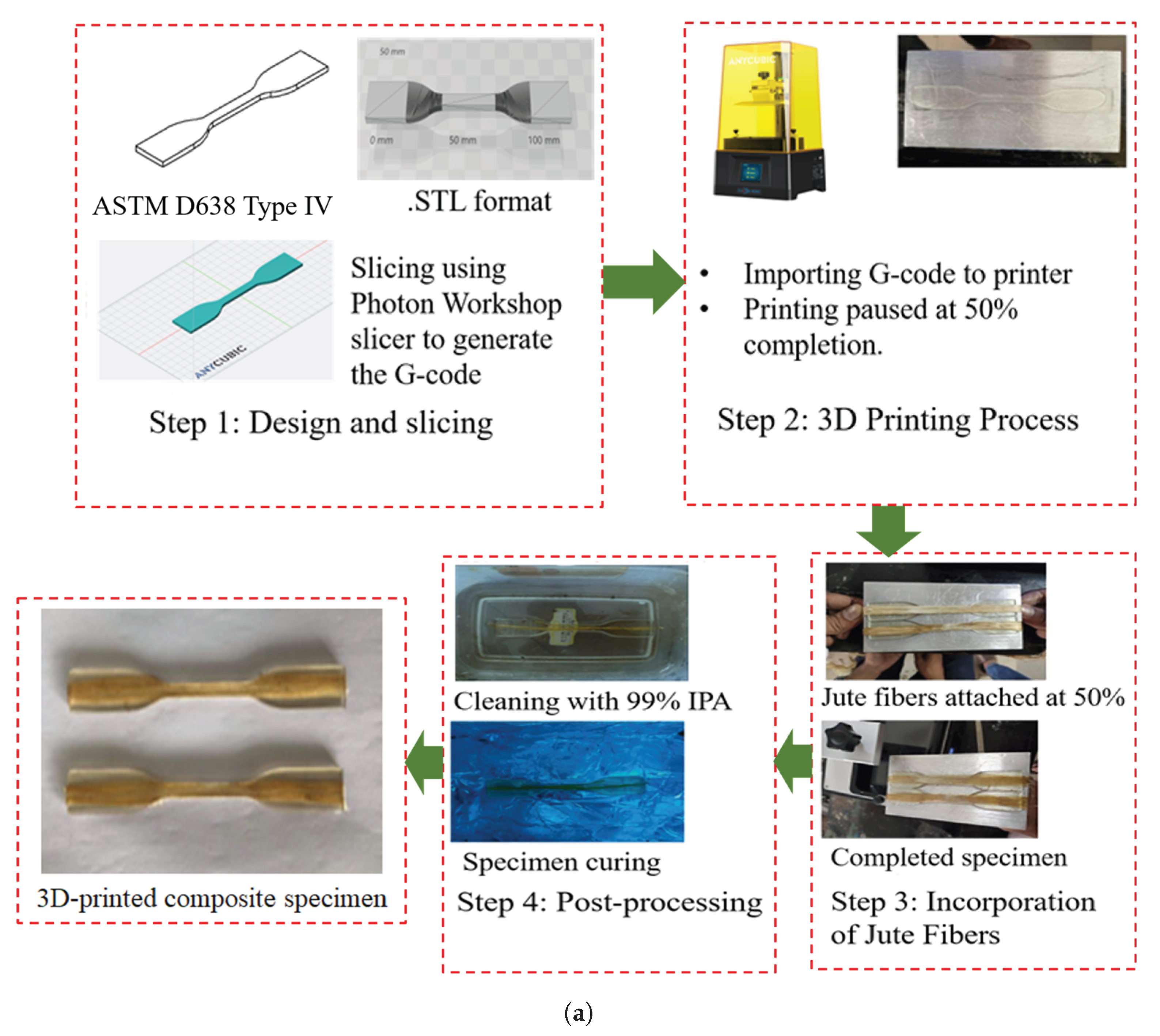

4.2.4. Jute-Reinforced Composites

4.2.5. Overarching Challenges and Mitigation Strategies in FFF of NFCs

5. Summary

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C.; Sapuan, S.; Ilyas, R.; Lee, S.; Khalina, A. Development and Processing of PLA, PHA, and Other Biopolymers. In Advanced Processing, Properties, and Applications of Starch and Other Bio-Based Polymers; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, M.S.; Chércoles, R.; Navarro, E.; de la Roja, J.M.; Gorostiza, J.; Higueras, M.; Blanch, E. Use of 3D Printing PLA and ABS Materials for Fine Art. Analysis of Composition and Long-Term Behaviour of Raw Filament and Printed Parts. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2023, 59, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.N.; Abourayana, H.M.; Dowling, D.P. 3D Printing of Fibre-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites Using Fused Filament Fabrication—A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantaros, A.; Drosos, C.; Papoutsidakis, M.; Pallis, E.; Ganetsos, T. The Role of 3D Printing in Advancing Automated Manufacturing Systems: Opportunities and Challenges. Automation 2025, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuan-Urquizo, E.; Barocio, E.; Tejada-Ortigoza, V.; Pipes, R.B.; Rodriguez, C.A.; Roman-Flores, A. Characterization of the Mechanical Properties of FFF Structures and Materials: A Review on the Experimental, Computational and Theoretical Approaches. Materials 2019, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djokikj, J.; Doncheva, E.; Tuteski, O.; Hadjieva, B. Mechanical Properties of Parts Fabricated with Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Mechanical Properties of Fused Filament Fabrication Parts. International scientific journal "Machines. technologies materials" 2022, 16, 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- 3D Printing: Saving Weight and Space at Launch - NASA, 2025. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/ missions/station/iss-research/3d-printing-saving-weight-and-space-at-launch/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- NTRS - NASA Technical Reports Server. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20210023437: (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Tahir, M.; Seyam, A.F. Greening Fused Deposition Modeling: A Critical Review of Plant Fiber-Reinforced PLA-Based 3D-Printed Biocomposites. Fibers 2025, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, S.; Do, T.; Tran, P. FDM-Based 3D Printing of Polymer and Associated Composite: A Review on Mechanical Properties, Defects and Treatments. Polymers 2020, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, D.; Rizzo, D.; Casciaro, R.; Esposito Corcione, C. A Review of Polymer-Based Materials for Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF): Focus on Sustainability and Recycled Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofangchi, A.; Han, P.; Izquierdo, J.; Iyengar, A.; Hsu, K. Effect of Ultrasonic Vibration on Interlayer Adhesion in Fused Filament Fabrication 3D Printed ABS. Polymers 2019, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairabayeva, D.; Auyeskhan, U.; Talamona, D. Mechanical Properties and Economic Analysis of Fused Filament Fabrication Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Long, H.; Baghani, M.; Rao, Y.; Peng, Y. Hygrothermal Aging Effects on the Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Composites with Different Stacking Sequence of Continuous Glass Fiber Layers. Polymer Testing 2021, 100, 107242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabezi, P.; Flanagan, T.; Walls, M.; Harrison, N.M. Degradation Characteristics of 3D Printed Continuous Fibre-Reinforced PA6/Chopped Fibre Composites in Simulated Saltwater. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2025, 10, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evon, P. Special Issue “Natural Fiber Based Composites II”. Coatings 2023, 13, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Bourmaud, A.; Davies, P.; Baley, C.; Davies, P.; Baley, C. Long Term Immersion in Natural Seawater of Flax/PLA Biocomposite. Ocean Engineering 2014, 90, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.H.; Sun, M.y.; Lim, J.K. Moisture Absorption, Tensile Strength and Microstructure Evolution of Short Jute Fiber/Polylactide Composite in Hygrothermal Environment. Materials & Design 2010, 31, 3167–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, A.; Sozen, A.; Neser, G.; Seydibeyoglu, M.O. Effects of Aging and Infill Pattern on Mechanical Properties of Hemp Reinforced PLA Composite Produced by Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). Applied Science and Engineering Progress 2025, 14, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Minshall, T. Invited Review Article: Where and How 3D Printing Is Used in Teaching and Education. Additive Manufacturing 2019, 25, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, D.; Patti, A. Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) of Thermoplastic-Based Filaments: Process and Rheological Properties—An Overview. Materials 2023, 16, 7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Kong, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yin, Q.; Xing, D.; Li, P. A Review on Voids of 3D Printed Parts by Fused Filament Fabrication. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 15, 4860–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Fused Deposition Modelling: Advances in Engineering and Medicine. In AAPS Advances in the Pharmaceutical Sciences Series; Springer Nature, 2018; pp. 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Haufe, P.; Sells, E.; Iravani, P.; Olliver, V.; Palmer, C.; Bowyer, A. RepRap – the Replicating Rapid Prototyper. Robotica 2011, 29, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, S.S. Apparatus and Method for Creating Three-Dimensional Objects. US US5121329A, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.; Deshpande, Y.; Parle, D. Extracting Slicer Parameters from STL File in 3D Printing. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering 2024, 12, 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiawan, R.B.; Imaduddin, F.; Ariawan, D.; Ubaidillah. ; Arifin, Z. A Review on the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D Printing: Filament Processing, Materials, and Printing Parameters. Open Engineering 2021, 11, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, B. 3-D Printing: The New Industrial Revolution. Business Horizons 2012, 55, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exclusive Interview: Retiring Stratasys Founder Scott Crump on His 3D Printing Legacy. Available online: https://www.tctmagazine.com/additive-manufacturing-3d-printing-news/exclusive-stratasys-scott-crump-3d-printing-legacy/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Stratasys, Inc. 08 October. Available online: https://www.stratasys.com/en/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. From Rapid Prototyping to Home Fabrication: How 3D Printing Is Changing Business Model Innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2016, 102, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, E.; Rao, B. 3D Printing: On Its Historical Evolution and the Implications for Business. In Proceedings of the 2015 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Portland, OR, USA; 2015; pp. 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, E.; Craft, D.; Rong, Y. 3D Printing Technology Will Eventually Eliminate the Need of Purchasing Commercial Phantoms for Clinical Medical Physics QA Procedures. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics 2018, 19, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://hackaday.com/2016/03/02/getting-it-right-by-getting-it-wrong-reprap-and-the-evolution-of-3d-printing/repraponedarwin-darwin/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Romero, L.; Guerrero, A.; Espinosa, M.M.; Jiménez, M.; Domínguez, I.A.; Domínguez, M. Additive Manufacturing with RepRap Methodology: Current Situation and Future Prospects. In Additive Manufacturing with RepRap Methodology: Current Situation and Future Prospects. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, Texas, USA, 2014., 4-6 August.

- Available online: https://reprap.org/wiki/Mendel (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Laumann, D.; Spiehl, D.; Dörsam, E. Device for Measuring Part Adhesion in FFF Process. HardwareX 2022, 11, e00258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.A.; Koç, M. Fused Filament Fabrication Process: A Review of Numerical Simulation Techniques. Polymers 2021, 13, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaros, A.; Katsantoni, M.; Ganetsos, T.; Petrescu, N. The Evolution of Thermoplastic Raw Materials in High-Speed FFF/FDM 3D Printing Era: Challenges and Opportunities. Materials 2025, 18, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creality - Official Website. Available online: https://www.creality.com/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Bambu Lab - Official Website. 08 October. Available online: https://bambulab.com/en/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Ahn, S.H.; Montero, M.; Odell, D.; Roundy, S.; Wright, P.K. Anisotropic Material Properties of Fused Deposition Modeling ABS. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2002, 8, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, J.M.; Caminero, M.A.; García-Plaza, E.; Núñez, P.J. Additive Manufacturing of PLA Structures Using Fused Deposition Modelling: Effect of Process Parameters on Mechanical Properties and Their Optimal Selection. Materials & Design 2017, 124, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodžić, D.; Pandžić, A.; Hajro, I.; Tasić, P. Strength Comparison of FDM 3D Printed PLA Made by Different Manufacturers. TEM Journal 2020, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.F.; Branco, R.; Martins, M.; Macek, W.; Marciniak, Z.; Silva, R.; Trindade, D.; Moura, C.; Franco, M.; Malça, C. Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Polymeric Materials—PLA and PETG—For Biomechanical Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Cui, T.; Yue, Y.; Li, C.; Guo, X.; Jia, X.; Wang, B. Preparation and Characterization for the Thermal Stability and Mechanical Property of PLA and PLA/CF Samples Built by FFF Approach. Materials 2023, 16, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias Gonçalves, V.P.; Vieira, C.M.F.; Simonassi, N.T.; Perissé Duarte Lopes, F.; Youssef, G.; Colorado, H.A. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of ABS-like Resin for Stereolithography Versus ABS for Fused Deposition Modeling in Three-Dimensional Printing Applications for Odontology. Polymers 2024, 16, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozdić, E. Characterization and Comparative Analysis of Mechanical Parameters of FDM- and SLA-Printed ABS Materials. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelak, K.; aszcz, J.; Polkowski, J.; Mastalski, P.; Kluczyński, J.; uszczek, J.; Torzewski, J.; Szachogłuchowicz, I.; Szymaniuk, R. Additive Manufacturing of Plastics Used for Protection against COVID19—The Influence of Chemical Disinfection by Alcohol on the Properties of ABS and PETG Polymers. Materials 2021, 14, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsavina, L.; Dohan, V.; Galatanu, S.V. Mechanical Evaluation of Recycled PETG Filament for 3D Printing. Frattura ed Integrità Strutturale 2024, 18, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekrem, M.; Yılmaz, M. Mechanical Properties of PLA, PETG, and ABS Samples Printed on a High-Speed 3D Printer. Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Fen ve Mühendislik Bilimleri Dergisi 2025, 7, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.; Duygun, İ.K.; Bedeloğlu, A. The Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid/Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol Multi-Material Structures Manufactured by Material Extrusion. 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing 2024, 11, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, Y.P.; Naidu, N.K.; Yadavalli, V.R.; Muthyala, M.R. The Comparison of the Mechanical Characteristics of ABS Using Three Different Plastic Production Techniques. Open Access Library Journal 2023, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankin, A.; Alipov, Y.; Temirgali, A.; Serik, G.; Danenova, S.; Talamona, D.; Perveen, A. Optimization of Printing Parameters to Enhance Tensile Properties of ABS and Nylon Produced by Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers 2023, 15, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhosale, K.K. Mechanical Properties Evaluation of 3D Printed PETG and PCTG Polymers. Mechanical Properties Evaluation of 3D Printed PETG and PCTG Polymers. Master of Science, South Dakota State University, South Dakota, 2023.

- Riat, A. Tensile Testing and Mechanical Property Prediction of 3D Printed PLA Using FEA and Machine Learning. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2025, 13, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronca, A.; Abbate, V.; Redaelli, D.F.; Storm, F.A.; Cesaro, G.; De Capitani, C.; Sorrentino, A.; Colombo, G.; Fraschini, P.; Ambrosio, L. A Comparative Study for Material Selection in 3D Printing of Scoliosis Back Brace. Materials 2022, 15, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaka, S.; Jagannati, V.; Pappula, B.; Makgato, S. Impact of Infill Density on Morphology and Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed ABS/CF-ABS Composites Using Design of Experiments. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikło, M.; Byczuk, B.H.; Skrzek, K. Mechanical Characterization of FDM 3D-Printed Components Using Advanced Measurement and Modeling Techniques. Materials 2025, 18, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolzyk, G.; Jung, S. Tensile and Fatigue Analysis of 3D-Printed Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol. Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention 2019, 19, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- , A. M.N.; Bandyopadhyay, B.; Yadav, S.S.; T, G.; Swamy, G.K.; Gouli, G. Development and Mechanical Evaluation of PETG-Chitosan Biodegradable Composites for Fused Filament Fabrication. Revista Electronica de Veterinaria 2024, 25, 1850–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisopol, D.G.; Minescu, M.; Iacob, D.V. A Study on the Influence of FDM Parameters on the Tensile Behavior of Samples Made of PET-G. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 2024, 14, 13487–13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilji, I.A.; Chilakamarry, C.R.; Surendran, A.N.; Kate, K.; Satyavolu, J. Natural Fiber Composite Filaments for Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Davies, I.J.; Pramanik, A.; John, M.; Biswas, W.K. Potential of Recycled PLA in 3D Printing: A Review. Sustainable Manufacturing and Service Economics 2024, 3, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, A.; Huether, J.; Liebig, W.V.; Elsner, P. Fused Filament Fabrication: Comparison of Methods for Determining the Interfacial Strength of Single Welded Tracks. Manufacturing Review 2021, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Printer 3D Creality K1 Speedy. Available online: https://center3dprint.com/pl/drukarka-3d-creality-k1-speedy (accessed on 8 October 2025). (In Polish).

- Constantin, G.; Botez, C.; Botez, S.C. Trends in the Use of Plastic Materials in 3d Printing Applications. Proceedings in Manufacturing Systems 2024, 19, 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Adarsh, S.H.; Nagamadhu, M. Effect of Printing Parameters on Mechanical Properties and Warpage of 3D-Printed PEEK/CF-PEEK Composites Using Multi-Objective Optimization Technique. Journal of Composites Science 2025, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, M.H.; Lai, C.J.; Wang, S.H.; Zeng, Y.S.; Hsieh, C.H.; Pan, C.Y.; Huang, W.C. Effect of Printing Parameters on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PLA and PETG, Using Fused Deposition Modeling. Polymers 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkundalova, O.; Rimkus, A.; Gribniak, V. Structural Application of 3D Printing Technologies: Mechanical Properties of Printed Polymeric Materials. ResearchGate 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.; Minetola, P.; Khandpur, M.S.; Giubilini, A. Evaluating Self-Produced PLA Filament for Sustainable 3D Printing: Mechanical Properties and Energy Consumption Compared to Commercial Alternatives. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2025, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurohit, S.R.; Dave, H.K. Impact Strength of 3D Printed PLA Using Open Source FFF-based 3D Printer. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2021, 6, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domerg, M.; Ostre, B.; Belec, L.; Berlioz, S.; Joliff, Y.; Grunevald, Y.H. Aging Effects at Room Temperature and Process Parameters on 3D-printed Poly (Lactic Acid) (PLA) Tensile Properties. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2024, 9, 2427–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, MargaretH. ; Badzinski, T.D.; Pardoe, E.; Ehlebracht, M.; Maurer-Jones, M.A. UV Light Degradation of Polylactic Acid Kickstarts Enzymatic Hydrolysis. ACS Materials Au 2023, 4, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Silva, K.; Capezza, A.J.; Gil-Castell, O.; Badia-Valiente, J.D. UV-C and UV-C/H2O-Induced Abiotic Degradation of Films of Commercial PBAT/TPS Blends. Polymers 2025, 17, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamadiala, I.; Croitoru, C.; Pop, M.A.; Roata, I.C. Enhancing Polylactic Acid (PLA) Performance: A Review of Additives in Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Filaments. Polymers 2025, 17, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M. A Review on Degradation Mechanisms of Polylactic Acid: Hydrolytic, Photodegradative, Microbial, and Enzymatic Degradation. Polymer Engineering & Science 2020, 60, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Martín Del Campo, A.S.; Robledo-Ortíz, J.R.; Arellano, M.; Pérez-Fonseca, A.A. Accelerated Weathering of Poly(Lactic Acid) and Its Biocomposites: A Review. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2020, 179, 109290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec, A. The Effect of Dyes, Pigments and Ionic Liquids on the Properties of Elastomer Composites. Ph.D. Tesis, Technical University of Lodz And University Claude Bernard, Poland – France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amza, C.G.; Zapciu, A.; Baciu, F.; Vasile, M.I.; Popescu, D. Aging of 3D Printed Polymers under Sterilizing UV-C Radiation. Polymers 2021, 13, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulich, D.M.; Gaggar, S.K.; Lowry, V.; Stepien, R. Acrylonitrile–Butadiene–Styrene (ABS) Polymers. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziąbka, M.; Dziadek, M.; Pielichowska, K. Surface and Structural Properties of Medical Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene Modified with Silver Nanoparticles. Polymers 2020, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Potgieter, J.; Ray, S.; Archer, R.; Arif, K.M. Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene and Polypropylene Blend with Enhanced Thermal and Mechanical Properties for Fused Filament Fabrication. Materials 2019, 12, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, R.; Butt, J.; Shirvani, H. Investigating the Properties of ABS-Based Plastic Composites Manufactured by Composite Plastic Manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2022, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueca de Bruijn, A.; Gómez-Gras, G.; Pérez, M.A. A Comparative Analysis of Chemical, Thermal, and Mechanical Post-Process of Fused Filament Fabricated Polyetherimide Parts for Surface Quality Enhancement. Materials 2021, 14, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowski, W.; Marć, M.; Kalinowska, K.; Kosmela, P.; Zabiegała, B. Emission Profiles of Volatiles during 3D Printing with ABS, ASA, Nylon, and PETG Polymer Filaments. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 27, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Sun, C.; She, L.; Peng, Y. Emission Characteristics of Volatile Organic Compounds from Material Extrusion Printers Using Acrylonitrile–Butadiene–Styrene and Polylactic Acid Filaments in Printing Environments and Their Toxicological Concerns. Toxics 2025, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C.; Kyrtopoulos, I.V.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Bartzanas, T. The Aging of Polymers under Electromagnetic Radiation. Polymers 2024, 16, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P. The Effect of Photo-Oxidative Degradation on Fracture in ABS Pipe Resins. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2004, 84, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrol, A.; Góralski, B.; Wichniarek, R.; Kuczko, W. The Natural Moisture of ABS Filament and Its Influence on the Quality of FFF Products. Materials 2023, 16, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, C.; Devine, D.M.; Keane, G.; Gately, N.M. A Comparative Analysis of Mechanical Properties in Injection Moulding (IM), Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF), and Arburg Plastic Freeforming (APF) Processes. Polymers 2025, 17, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, W.; Firmansyah, H.I.; Adiwidodo, S.; Mustapa, M.S. Impact of Print Speed and Nozzle Temperature on Tensile Strength of 3D Printed ABS for Permanent Magnet Turbine Systems. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science and Technology (JMEST) 2025, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Ohdar, R.; Mahapatra, S. Parametric Appraisal of Mechanical Property of Fused Deposition Modelling Processed Parts. Materials & Design 2010, 31, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Turner, B.; Strong, R.; A. Gold, S. A Review of Melt Extrusion Additive Manufacturing Processes: I. Process Design and Modeling. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2014, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellehumeur, C.; Li, L.; Sun, Q.; Gu, P. Modeling of Bond Formation Between Polymer Filaments in the Fused Deposition Modeling Process. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2004, 6, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Rizvi, G.; Bellehumeur, C.; Gu, P. Effect of Processing Conditions on the Bonding Quality of FDM Polymer Filaments. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2008, 14, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlroy, C.; Olmsted, P. Disentanglement Effects on the Welding Behaviour of Polymer Melts during the Fused-Filament-Fabrication Method for Additive Manufacturing. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.09295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foppiano, M.; Saluja, A.; Fayazbakhsh, K. The Effect of Variable Nozzle Temperature and Cross-Sectional Pattern on Interlayer Tensile Strength Of 3D Printed ABS Specimens. Experimental Mechanics 2021, 61, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzyod, H.; Ficzere, P. Optimizing Fused Filament Fabrication Process Parameters for Quality Enhancement of PA12 Parts Using Numerical Modeling and Taguchi Method. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrlybayev, D.; Zharylkassyn, B.; Seisekulova, A.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Optimization of the Warpage of Fused Deposition Modeling Parts Using Finite Element Method. Polymers 2021, 13, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, L.; García-Molleja, J.; Fernández-Blázquez, J.P.; González, C. Unraveling the Print–Structure–Property Relationships in the FFF of PEEK: A Critical Assessment of Print Parameters. Polymers 2025, 17, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurgesang, F.A.; Dhewanto, S.A.; Ridlwan, M.; Paryanto, P. The Effect Of Printing Speed And Nozzle Temperature On Tensile Strength, Geometry, and Surface Roughness Of A Product Printed Using ABS Filament. Prosiding Simposium Nasional Rekayasa Aplikasi Perancangan dan Industri, 2022; 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Girish, S.; Jenny, P.S.W.; Aika, Y.D.; Marilyn, S.B.; Pratim, B.; Weber, R.J. Investigating Particle Emissions and Aerosol Dynamics from a Consumer Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printer with a Lognormal Moment Aerosol Model. Aerosol Science and Technology 2018, 52, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Lan, M.; Li, Z.; Lu, S.; Wu, G. GM-Improved Antiaging Effect of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene in Different Thermal Environments. Polymers 2019, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceretti, D.V.A.; Marien, Y.W.; Edeleva, M.; La Gala, A.; Cardon, L.; D’hooge, D.R. Thermal and Thermal-Oxidative Molecular Degradation of Polystyrene and Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene during 3D Printing Starting from Filaments and Pellets. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceretti, D.V.A.; Edeleva, M.; Cardon, L.; D’hooge, D.R. Molecular Pathways for Polymer Degradation during Conventional Processing, Additive Manufacturing, and Mechanical Recycling. Molecules 2023, 28, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E.; Haddad, R. Photodegradation and Photostabilization of Polymers, Especially Polystyrene: Review. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, Y.S.; Ho, T.C.; Chen, J.R.; Kao, C.S. Study on Exothermic Oxidation of Acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) Resin Powder with Application to ABS Processing Safety. Polymers 2010, 2, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorio, R.; Villanueva Díez, S.; Sánchez, A.; D’hooge, D.R.; Cardon, L. Influence of Different Stabilization Systems and Multiple Ultraviolet A (UVA) Aging/Recycling Steps on Physicochemical, Mechanical, Colorimetric, and Thermal-Oxidative Properties of ABS. Materials 2020, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Botelho, G.; Machado, A.V. Role of Ultraviolet Absorbers (UVA) and Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers (HALS) in ABS Stabilization. Materials Science Forum 2010, 636–637, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; You, H. Photodegradation Behavior and Mechanism of Poly(Ethylene Glycol-Co-1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanol Terephthalate) (PETG) Random Copolymers: Correlation with Copolymer Composition. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 102778–102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, A. Investigation of the Effect of Exposure to Liquid Chemicals on the Strength Performance of 3D-Printed Parts from Different Filament Types. Polymers 2025, 17, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozrt, J.; Votava, J.; Henzl, R.; Kumbár, V.; Dostál, P.; Čupera, J. Analysis of the Changes in the Mechanical Properties of the 3D Printed Polymer rPET-G with Different Types of Post-Processing Treatments. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.T.R.; Ramakrishna, D.G.; Devi, D.E.N. Mechanical Characterization of PETG-3D Printed Material for Enhancement and Scrutiny. YMER Digital 2025, 24, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waly, C.; Schulnig, S.; Arbeiter, F. Strain Rate-Dependent Failure Modes of Material Extrusion-Based Additively Manufactured PETG: A Study on Crack Deflection and Penetration. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2024, 136, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulridha, H.H.; Obaeed, N.H.; Jaber, A.S. Optimization of Fused Deposition Modeling Parameters for Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol Flexural Strength and Dimensional Accuracy. Advances in Science and Technology Research Journal 2025, 19, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.M.; Aized, T.; Farooq, M.; Anwar, S.; Ahmad, N.; Tauseef, A.; Riaz, F. Optimization of PETG 3D Printing Parameters for the Design and Development of Biocompatible Bone Implants. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2025, 13, 1549191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçel, O.; Kahya, Ç.; Tüfekci, K. Optimization of Flexural Performance of PETG Samples Produced by Fused Filament Fabrication with Response Surface Method. Polymers 2024, 16, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, G.; Caldona, E.B.; Cheng, X.; Advincula, R.C. On the Optimized 3D Printing and Post-Processing of PETG Materials. MRS Communications 2022, 12, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerk, M.; Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J.; Sapkota, J.; Schuschnigg, S.; Holzer, C. Effect of the Printing Bed Temperature on the Adhesion of Parts Produced by Fused Filament Fabrication. Plastics, Rubber and Composites 2018, 47, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Sood, S.; Bharadwaj, V.; Aggarwal, A.; Khanna, P. Parametric Modeling and Optimization of Dimensional Error and Surface Roughness of Fused Deposition Modeling Printed Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol Parts. Polymers 2023, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taresh, O.F.; Mezher, M.T.; Daway, E.G. Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PETG Samples: The Effect of Varying Infill Patterns. Revue des composites et des matériaux avancés 2023, 33, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Nieto, D.; Alonso-García, M.; Pardo-Vicente, M.A.; Rodríguez-Parada, L. Product Design by Additive Manufacturing for Water Environments: Study of Degradation and Absorption Behavior of PLA and PETG. Polymers 2021, 13, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Effect of Drying Treatment on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Material Extrusion-Based 3D-Printed PETG Models. BioResources 2025, 20, 7000–7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, C.; Ohnmacht, H.; Reyes Isaacura, P.; Van Steenberge, P.; Cardon, L.; D’hooge, D.; Edeleva, M. Quantifying Hydrolytic Degradation of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate Glycol) under Storage Conditions and for Fused Filament Fabrication Mechanical Properties. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2023, 217, 110511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatikova, S.; Dudacek, A.; Prichystalova, R.; Klecka, V.; Kocurkova, L. Characterization of Ultrafine Particles and VOCs Emitted from a 3D Printer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sava, S.D.; Lohan, N.M.; Pricop, B.; Popa, M.; Cimpoesu, N.; Comăneci, R.I.; Bujoreanu, L.G. On the Thermomechanical Behavior of 3D-Printed Specimens of Shape Memory R-PETG. Polymers 2023, 15, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeijn, T.; Behrens, M.; Paul, G.; Wei, D. Instantaneous and Long-Term Mechanical Properties of Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG) Additively Manufactured by Pellet-Based Material Extrusion. Additive Manufacturing 2022, 59, 103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantrao, J.; Motichand, J.; Narhari, B. A Review On: Glass Transition Temperature. International Journal of Advanced Research 2017, 5, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, S.F.; Smith, J.C.; Pester, C.W.; Vogt, B.D. Physical Aging and Evolution of Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol. RSC Applied Polymers 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, J.; Joska, Z.; Jansky, J.; Zouhar, J.; Kolomy, S.; Slany, M.; Svasta, A.; Jirousek, J. Analysis of the Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Plastic Samples Subjected to Selected Degradation Effects. Materials 2023, 16, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amza, C.G.; Zapciu, A.; Baciu, F.; Vasile, M.I.; Nicoara, A.I. Accelerated Aging Effect on Mechanical Properties of Common 3D-Printing Polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arangdad, K.; Detwiler, A.; Cleven, C.D.; Burk, C.; Shamey, R.; Pasquinelli, M.A.; Freeman, H.; El-Shafei, A. Photodegradation of Copolyester Films: A Mechanistic Study. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2019, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Sun, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, C. 3D Printing Continuous Fiber Reinforced Polymers: A Review of Material Selection, Process, and Mechanics-Function Integration for Targeted Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, B.A.; Alsuhybani, M.S.; Almushaikeh, A.M.; Alotaibi, B.M.; Alenad, A.M.; Alqahtani, N.B.; Alharbi, A.G. Comprehensive Review of the Properties and Modifications of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenken, B.; Barocio, E.; Favaloro, A.; Kunc, V.; Pipes, R.B. Fused Filament Fabrication of Fiber-Reinforced Polymers: A Review. Additive Manufacturing 2018, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Smith, D.E. Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of Oriented Carbon Fiber Filled Polymer Composites Produced with Fused Filament Fabrication. Additive Manufacturing 2017, 18, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanei, S.H.R.; Popescu, D. 3D-Printed Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Systematic Review. Journal of Composites Science 2020, 4, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayam, A.; Rahman, A.N.M.M.; Rahman, M.S.; Smriti, S.A.; Ahmed, F.; Rabbi, M.F.; Hossain, M.; Faruque, M.O. A Review on Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Hierarchical Composites: Mechanical Performance, Manufacturing Process, Structural Applications and Allied Challenges. Carbon Letters 2022, 32, 1173–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkamp, T.; Kuschmitz, S.; Girnth, S.; Marx, J.D.; Klawitter, G.; Waldt, N.; Vietor, T. Stress-Adapted Fiber Orientation along the Principal Stress Directions for Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Material Extrusion. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2023, 8, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, J.; Koirala, P.; Shen, Y.L.; Tehrani, M. Eliminating Voids and Reducing Mechanical Anisotropy in Fused Filament Fabrication Parts by Adjusting the Filament Extrusion Rate. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2022, 80, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, F.; Bardon, J.; Berthé, V.; Perrin, H.; Westermann, S.; Addiego, F. Fused Filament Fabrication of Polymers and Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: Advances in Structure Optimization and Health Monitoring. Polymers 2021, 13, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Mazur, M.; Cheng, C.T. A Review of Void Reduction Strategies in Material Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2023, 67, 103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Cong, W.; Qiu, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, S. Additive Manufacturing of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites Using Fused Deposition Modeling. Composites Part B: Engineering 2015, 80, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekinalp, H.L.; Kunc, V.; Velez-Garcia, G.M.; Duty, C.E.; Love, L.J.; Naskar, A.K.; Blue, C.A.; Ozcan, S. Highly Oriented Carbon Fiber–Polymer Composites via Additive Manufacturing. Composites Science and Technology 2014, 105, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Shan, Z.; Zhan, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, S. Warp Deformation Model of Polyetheretherketone Composites Reinforced with Carbon Fibers in Additive Manufacturing. Materials Research Express 2021, 8, 125305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Anwar, S.; AlFaify, A.Y.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; Abd Elgawad, A.E.E. Development of PLA/Recycled-Desized Carbon Fiber Composites for 3D Printing: Thermal, Mechanical, and Morphological Analyses. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 29, 2768–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, E.; Van Hemelrijck, D.; Pyl, L. Modeling of the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of 3D-printed Composites. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2024, 268, 108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, I.; Mancia, T.; Mignanelli, C.; Simoncini, M. Effect of Nozzle Wear on Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Parts by Material Extrusion. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 130, 4699–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumers, M.; Dickens, P.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. The Cost of Additive Manufacturing: Machine Productivity, Economies of Scale and Technology-Push. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2016, 102, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. A Review of Conductive Carbon Materials for 3D Printing: Materials, Technologies, Properties, and Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobov, E.; Vindokurov, I.; Tashkinov, M. Mechanical Properties and Performance of 3D-Printed Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene Reinforced with Carbon, Glass and Basalt Short Fibers. Polymers 2024, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. , M.K.H.; Benal, M.G.M.; G. S., P.K.; Tambrallimath, V.; H. R., G.; Khan, T.M.Y.; Rajhi, A.A.; Baig, M.A.A. Influence of Short Glass Fibre Reinforcement on Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed ABS-Based Polymer Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H R, M.; Benal, M.G.M.; G S, P.; Tambrallimath, V.; Ramaiah, K.; Khan, T.M.Y.; Bhutto, J.K.; Ali, M.A. Effect of Short Glass Fiber Addition on Flexural and Impact Behavior of 3D Printed Polymer Composites. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 9212–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicos, L.A.; Pop, M.A.; Zaharia, S.M.; Lancea, C.; Buican, G.R.; Pascariu, I.S.; Stamate, V.M. Fused Filament Fabrication of Short Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composites: Infill Density Influence on Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putro, A.J.N.; Bagaskara, G.; Prasetya, I.A.; Jamasri. ; Wiranata, A.; Wu, Y.C.; Muflikhun, M.A. Optimization of Innovative Hybrid Polylactic Acid+ and Glass Fiber Composites: Mechanical, Physical, and Thermal Evaluation of Woven Glass Fiber Reinforcement in Fused Filament Fabrication 3D Printing. Journal of Composites Science 2025, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; McCarthy, E.D. Fibre Flow and Void Formation in 3D Printing of Short-Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites: An Experimental Benchmark Exercise. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 37, 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalle, M.; Frascio, M. Mechanical Characterization and Modeling of Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide Built by Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2025, 18, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrocco, M.; Chamberlain, T.; Chow, C.; Weinreber, L.; Ellks, E.; Halford, C.; Cortes, P.; Conner, B.P. Impact Testing of 3D Printed Kevlar-Reinforced Onyx Material. Proceedings of 29th Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium – An Additive Manufacturing Conference, Austin, Texas, USA, December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmal Zia, A.; Tian, X.; Jawad Ahmad, M.; Tao, Z.; Meng, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Li, D. Impact Resistance of 3D-Printed Continuous Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Yang, N.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wu, W.; Ma, G. Experiment and Simulation Study on the Crashworthiness of Markforged 3D-Printed Carbon/Kevlar Hybrid Continuous Fiber Composite Honeycomb Structures. Materials 2025, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijckaert, S.; Daelemans, L.; Cardon, L.; Boone, M.; Van Paepegem, W.; De Clerck, K. Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Aramid/PETG 3D-Printed Composites with High Fiber Loading through Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers 2022, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brette, M.M.; Holm, A.H.; Drozdov, A.D.; Christiansen, J.d.C. Pure Hydrolysis of Polyamides: A Comparative Study. Chemistry (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany) 2024, 6, 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiralal Dhage, B.; Khedkar, N.K. Predictive Machine Learning and Printing Parameter Optimization for Enhanced Impact Performance of 3D-printed Onyx-Kevlar Composites. Discover Materials 2025, 5, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Núñez, B.A.; Abarca-Vidal, C.G.; Treviño-Quintanilla, C.D.; Sánchez-Santana, U.; Cuan-Urquizo, E.; Uribe-Lam, E. Experimental Analysis of Fiber Reinforcement Rings’ Effect on Tensile and Flexural Properties of Onyx™–Kevlar® Composites Manufactured by Continuous Fiber Reinforcement. Polymers 2023, 15, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, A.; Kartal, F. A Critical Review of Composite Filaments for Fused Deposition Modeling: Material Properties, Applications, and Future Directions. European Mechanical Science 2024, 8, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursache, S.; Cerbu, C.; Hadăr, A. Characteristics of Carbon and Kevlar Fibres, Their Composites and Structural Applications in Civil Engineering—A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadizadeh, M.; Fidan, I. Tensile Performance of 3D-Printed Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Nylon Composites. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2021, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincheira, G.; Canales, C.; Medina, C.; Fernández, E.; Flores, P. Influence of Aramid Fibers on the Mechanical Behavior of a Hybrid Carbon–Aramid–Reinforced Epoxy Composite. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications 2018, 232, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzat, A.K.; Murad, M.S.; Adediran, I.A.; Asmatulu, E.; Asmatulu, R. Fiber-Reinforced Composites for Aerospace, Energy, and Marine Applications: An Insight into Failure Mechanisms under Chemical, Thermal, Oxidative, and Mechanical Load Conditions. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2025, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagumalai, V.; Shanmugam, V.; Balasubramanian, N.K.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Ganesan, V.; Försth, M.; Sas, G.; Berto, F.; Chanda, A.; Das, O. Impact Response and Damage Tolerance of Hybrid Glass/Kevlar-Fibre Epoxy Structural Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Mechanical Performance/Cost Ratio Analysis of Carbon/Glass Interlayer and Intralayer Hybrid Composites. Coatings 2024, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagmare, R.; Harshe, R.; Pednekar, J.; Patro, T.U. Effect of Compaction Pressure on Void Content and Mechanical Properties of Unidirectional Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites Prepared by 3D Printing. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2024, 10, 5187–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.A.; Shah, O.R.; Ghafoor, U.; Qureshi, Y.; Bhutta, M.R. Additive Manufacturing of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites via Fused Deposition Modelling: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaros, A.; Soulis, E.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Ganetsos, T. Advanced Composite Materials Utilized in FDM/FFF 3D Printing Manufacturing Processes: The Case of Filled Filaments. Materials 2023, 16, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchuk, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, B.; Zhao, X.; Islam, N.M.; Bocharova, V.; Yang, G.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, Y.; Choi, W.; et al. Unravelling the Influence of Surface Modification on the Ultimate Performance of Carbon Fiber/Epoxy Composites. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2022, 14, 45775–45787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, M.S.; Sankara Subramanian, H.; B. , R.K.; Suyambulingam, I.; Senthamaraikannan, P.; Kumar, R. A Review on Fiber Properties, Manufacturing, and Crashworthiness of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composite Structures. Journal of Natural Fibers 2025, 22, 2520845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapež Tomec, D.; Kariž, M. Use of Wood in Additive Manufacturing: Review and Future Prospects. Polymers 2022, 14, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitaľová, Z.; Mitaľ, D.; Berladir, K. A Concise Review of the Components and Properties of Wood–Plastic Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parbin, S.; Waghmare, N.K.; Singh, S.K.; Khan, S. Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composites: A Review. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 152, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Yu, T.; Li, Y. Effect of Hydrothermal Aging on Injection Molded Short Jute Fiber Reinforced Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) Composites. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2018, 26, 3176–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaia, J.P.; Manaia, A.T.; Rodriges, L. Industrial Hemp Fibers: An Overview. Fibers 2019, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran Royan, N.R.; Leong, J.S.; Chan, W.N.; Tan, J.R.; Shamsuddin, Z.S.B. Current State and Challenges of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites as Feeder in FDM-Based 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Khalina, A.; Lee, S.H. Importance of Interfacial Adhesion Condition on Characterization of Plant-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, R.; Manley, A.J.; Wu, Z.; Feng, X. Digital 3D Wood Texture: UV-Curable Inkjet Printing on Board Surface. Coatings 2020, 10, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martikka, O.; Kärki, T.; Wu, Q. Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Wood-Plastic Composites. Key Engineering Materials 2018, 777, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.C.; Yang, T.C. Properties of Heat-Treated Wood Fiber–Polylactic Acid Composite Filaments and 3D-Printed Parts Using Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers 2024, 16, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ufodike, C.O.; Ahmed, M.F.; Dolzyk, G. Additively Manufactured Biomorphic Cellular Structures Inspired by Wood Microstructure. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2021, 123, 104729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, S.Y.; Yang, T.H.; Lo, S.F.; Yang, T.H. Optimized Material Composition to Improve the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Extruded Wood–Plastic Composites (WPCs). Construction and Building Materials 2012, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C.; Yeh, C.H. Morphology and Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Wood Fiber/Polylactic Acid Composite Parts Using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM): The Effects of Printing Speed. Polymers 2020, 12, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapež Tomec, D.; Schöflinger, M.; Leßlhumer, J.; Žigon, J.; Humar, M.; Kariž, M. Effect of Thermal Modification of Wood on the Rheology, Mechanical Properties and Dimensional Stability of Wood Composite Filaments and 3D-printed Parts. Wood Material Science & Engineering 2024, 19, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau-Devers, K.; Kortum, Z.; Miller, S.A. Hydrothermal Aging of Bio-Based Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) Wood Polymer Composites: Studies on Sorption Behavior, Morphology, and Heat Conductance. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 214, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Xie, G.; Qiu, Z. Effects of Ultraviolet Aging on Properties of Wood Flour–Poly(Lactic Acid) 3D Printing Filaments. BioResources 2019, 14, 8689–8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliotta, L.; Gigante, V.; Coltelli, M.B.; Cinelli, P.; Lazzeri, A.; Seggiani, M. Thermo-Mechanical Properties of PLA/Short Flax Fiber Biocomposites. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Barbé, A.; Guillou, E.; Castro, M. 3D Printing of Continuous Flax Fibre Reinforced Biocomposites for Structural Applications. Materials & Design 2019, 180, 107884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajbič, J.; Fajdiga, G.; Klemenc, J. Material Extrusion 3D Printing of Biodegradable Composites Reinforced with Continuous Flax Fibers. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 27, 3610–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.A.; Santiuste, C. Degradation of Mechanical Properties of Flax/PLA Composites in Hygrothermal Aging Conditions. Polymers 2024, 16, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Shi, X.; Wentao, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Flax Fiber Content on Polylactic Acid (PLA) Crystallization in PLA/Flax Fiber Composites. Iranian Polymer Journal 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Le Gall, M.; Niu, Z.; Catarino, A.; De Witte, Y.; Everaert, G.; Dhakal, H.; Park, C.; Demeyer, E. Recycling and Ecotoxicity of Flax/PLA Composites: Influence of Seawater Aging. Composites Part C: Open Access 2023, 12, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, N.; Wang, X.; Espejo, C.; Morina, A.; Emami, N. Impact of Processing Defects on Microstructure, Surface Quality, and Tribological Performance in 3D Printed Polymers. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 23, 1252–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Van Den Hurk, B.; Liu, T.; Blok, R.; Teuffel, P. Effect of UV-water Weathering on the Mechanical Properties of Flax-fiber -reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymer Composites 2024, 45, 4266–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, M.; Dashatan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Dhakal, H.N.; Khalfallah, M.; Gamer, N.; Ling, J. Inorganic Fillers and Their Effects on the Properties of Flax/PLA Composites after UV Degradation. Polymers 2023, 15, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valin Fernández, M.; Monsalves Rodríguez, M.A.; Medina Muñoz, C.A.; Palacio, D.A.; Soto, A.G.O.; Valin Rivera, J.L.; Valenzuela Diaz, F.R. Cationized Hemp Fiber to Improve the Interfacial Adhesion in PLA Composite. Polymers 2025, 17, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A.; Özkan, H.; Genceli Güner, F.E. Utilizing the Potential of Waste Hemp Reinforcement: Investigating Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Polypropylene and Polylactic Acid Biocomposites. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 8818–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Rasidi, M.; Mohammed, A.; Rahman, R.; Osman, A.; Adam, T.; Betar, B.; Dahham, O. Interfacial Bonding Mechanisms of Natural Fibre-Matrix Composites: An Overview. BioResources 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, M.S.; Islam, T.; Bhuiya, M.M.K. Jute Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites, A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development 2020, 10, 3053–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faidallah, R.F.; Hanon, M.M.; Salman, N.D.; Ibrahim, Y.; Babu, M.N.; Gaaz, T.S.; Szakál, Z.; Oldal, I. Development of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites for Additive Manufacturing and Multi-Material Structures in Sustainable Applications. Processes 2024, 12, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Mohiv, A.; Tauhiduzzaman, M.; Kharshiduzzaman, Md.; Khan, M.E.; Haque, M.R.; Bhuiyan, M.S. Tensile Properties of 3D-Printed Jute-Reinforced Composites via Stereolithography. Applied Mechanics 2024, 5, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, A.; Doğru, A.; Demi̇R, M.; Özdemi̇R, H.N.; Seki̇, Y. Production of Waste Jute Doped Pla (Polylactic Acid) Filament for FFF: Effect of Pulverization. International Journal of 3D Printing Technologies and Digital Industry 2023, 7, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, R.; Ueda, M.; Namiki, M.; Jeong, T.K.; Asahara, H.; Horiguchi, K.; Nakamura, T.; Todoroki, A.; Hirano, Y. Three-Dimensional Printing of Continuous-Fiber Composites by in-Nozzle Impregnation. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 23058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Song, G.; Liu, S. Recent Progress on Moisture Absorption Aging of Plant Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Jia, W.; Huang, K.; Ma, Y. Comparing the Aging Processes of PLA and PE: The Impact of UV Irradiation and Water. Processes 2024, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.; Dufresne, A.; Cherian, B.M.; Kaith, B.S.; Avérous, L.; Njuguna, J.; Nassiopoulos, E. Cellulose-Based Bio- and Nanocomposites: A Review. International Journal of Polymer Science 2011, 2011, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Shi, S.Q. Development and Application of Wood Flour-Filled Polylactic Acid Composite Filament for 3D Printing. Materials 2017, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Sreekala, M.S.; Thomas, S. A Review on Interface Modification and Characterization of Natural Fiber Reinforced Plastic Composites. Polymer Engineering & Science 2001, 41, 1471–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croom, B.P.; Abbott, A.; Kemp, J.W.; Rueschhoff, L.; Smieska, L.; Woll, A.; Stoupin, S.; Koerner, H. Mechanics of Nozzle Clogging during Direct Ink Writing of Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 37, 101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravoori, D.; Salvi, S.; Prajapati, H.; Qasaimeh, M.; Adnan, A.; Jain, A. Void Reduction in Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) through in Situ Nozzle-Integrated Compression Rolling of Deposited Filaments. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 2021, 16, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerk, M.; Holzer, C.; Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J. Material Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing of Polypropylene: A Review on How to Improve Dimensional Inaccuracy and Warpage. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2020, 137, 48545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Carbon Fiber (CF) [59,135,136,138,139,145,146,147] | Glass Fiber (GF) [135,153,154,155,156,157] | Aramid Fiber [160,161,162,163] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Young’s Modulus Improvement |

Increases from +160% (PLA-CF) up to +700% (ABS-CF) compared to neat polymers have been reported. | Increases up to +68% increase in tensile modulus reported for SGF-reinforced ABS. | Over 15-fold (∼+1400%) increase for PETG composites with continuous fibers (45 vol%). |

|

Tensile Strength Improvement |

Increases range from +14–47% (PLA-CF) to +22.5–33% (ABS-CF). | Increases of +31% to +57% reported for SGF-reinforced ABS composites. | Increases over 10-fold (∼+900%) increase for PETG composites with continuous fibers. |

|

Impact Resistance |

Generally exhibits brittle fracture. | Increases up to +54% increase in Izod impact strength (SGF). Up to +460% increase in Charpy impact energy for woven fabric in PLA+. | Characterized by high energy absorption and a ductile, non-catastrophic failure mode. Hybrids with aramid can increase energy absorption by 5.5–11.6%. |

|

Primary Challenge |

High cost, extreme nozzle abrasion, and brittle failure mode. | Lower absolute stiffness and higher density compared to carbon fiber. | Pronounced hygroscopicity. Challenges in achieving strong fiber-matrix adhesion. |

| Property | Wood-Plastic (WPC) [11,180,185,187,188] | Flax Fiber [195,196,197] | Hemp Fiber [185,204,205] | Jute Fiber [207,208,209,210,211] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tensile Strength |

Decrease: 4.8–7.3 MPa (vs. 26.8 MPa for neat PLA with 30–40% wood content). | Increase (Continuous): Up to 253.7 MPa (∼4x increase). No change (Short): Peak at 66 MPa (vs. 65 MPa for PLA). | Decrease (Untreated): 35–45 MPa (vs. 60–70 MPa for PLA). Performance can be improved with chemical treatment. | Increase (Continuous): To 57.1 MPa (+134%). |

|

Young’s Modulus |

Load Dependent: Can increase to 2600–3100 MPa at 20 wt% content. | Increase: 6500–7300 MPa (+88–121%) for short fibers; up to 23300 MPa (∼7x increase) for continuous fibers. | Increase: To over 4100 MPa (+120% vs. ∼3400 MPa for PLA). | Increase (Continuous): To 5110 MPa (+157%). |

|

Impact Resistance |

Decrease: 2.9–3.3 kJ/m2 (vs. 5.4 kJ/m2 for neat PLA). | - | - | - |

|

Primary Challenge |

Acts more as a filler than a reinforcement, significantly decreasing strength. | High susceptibility to degradation from moisture and UV radiation (e.g., up to 60% strength loss in seawater). | Very poor interfacial adhesion without chemical treatment, leading to high variability in results. | Large performance gap between short fibers (property decrease) and continuous fibers (property increase). Susceptible to hygrothermal aging. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).