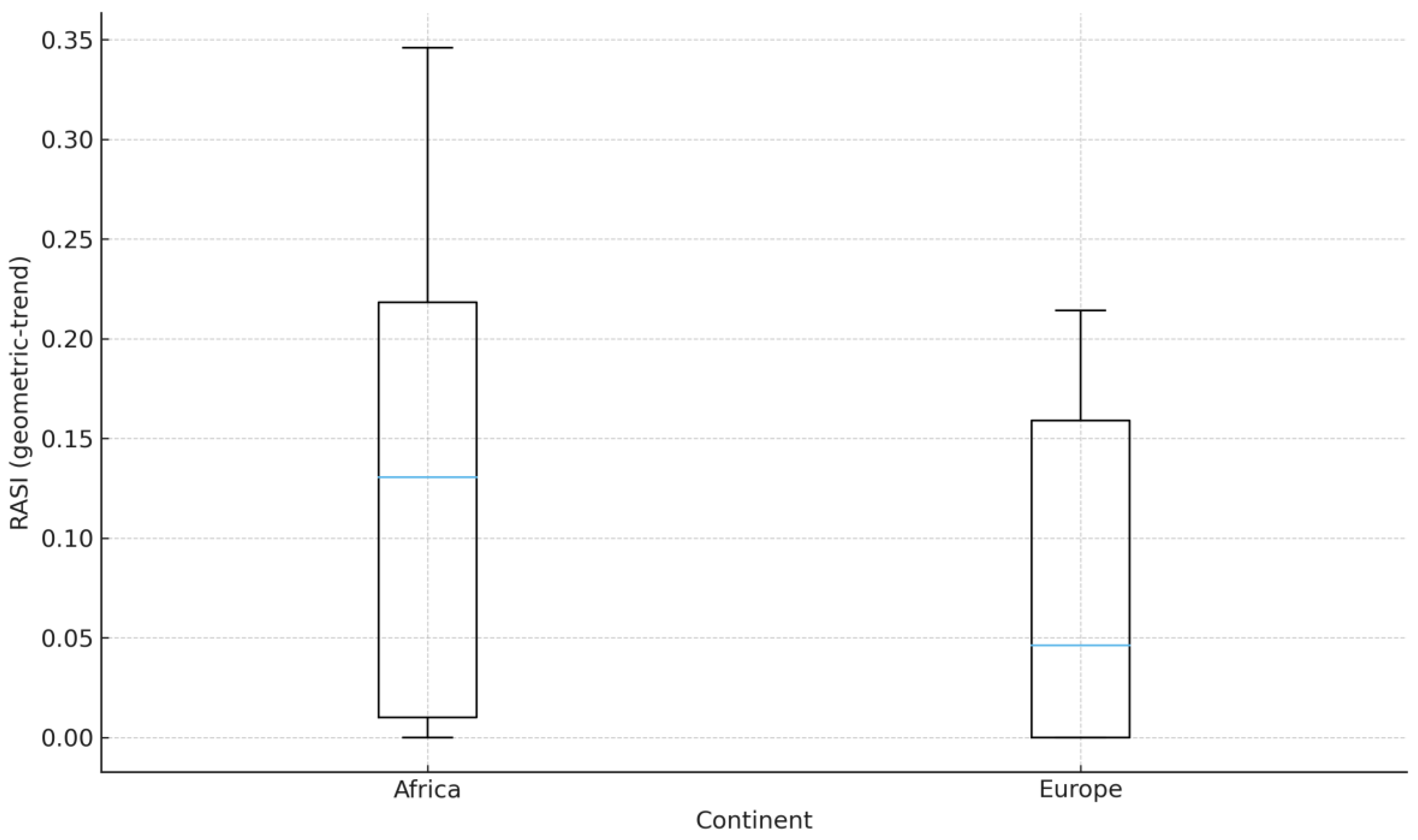

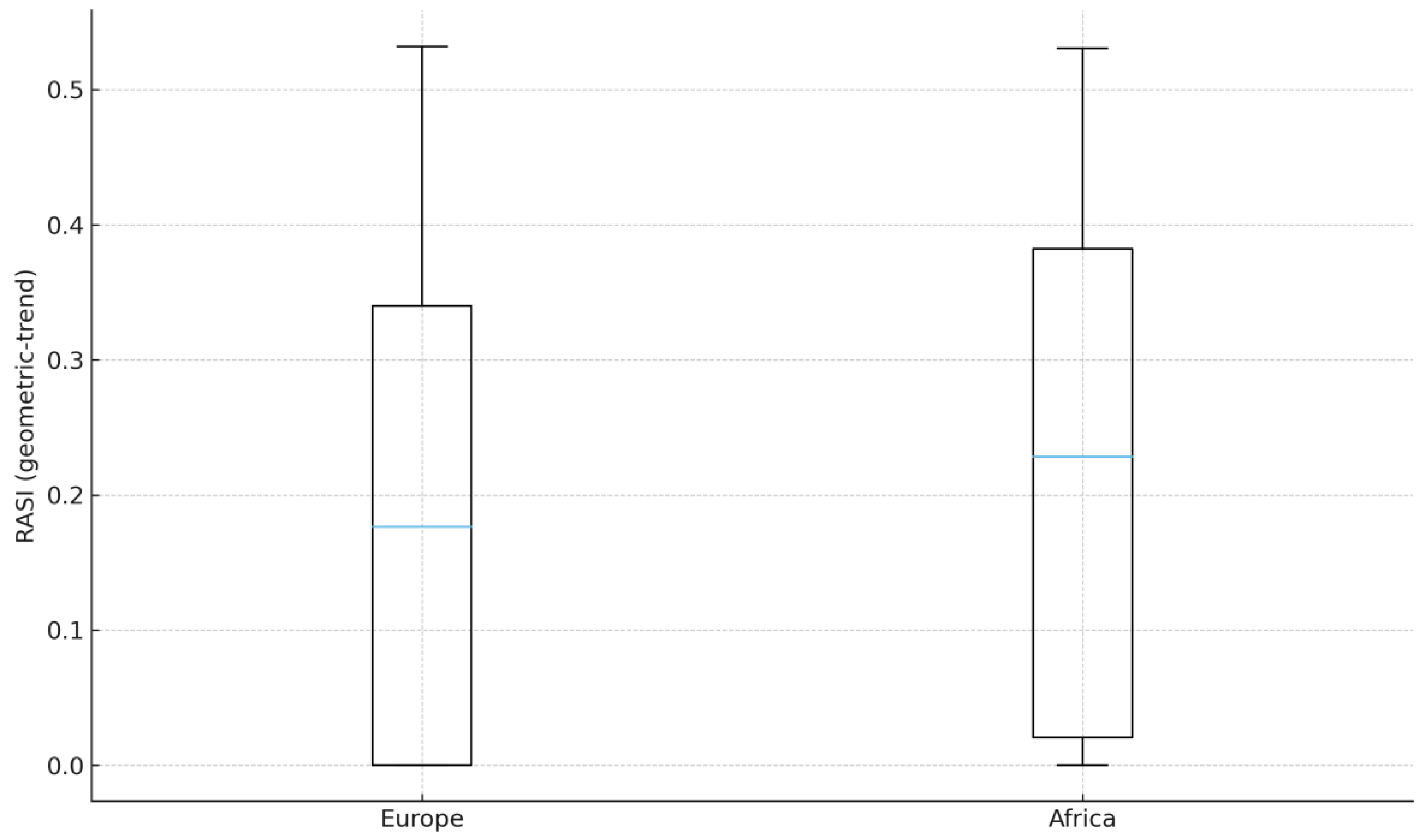

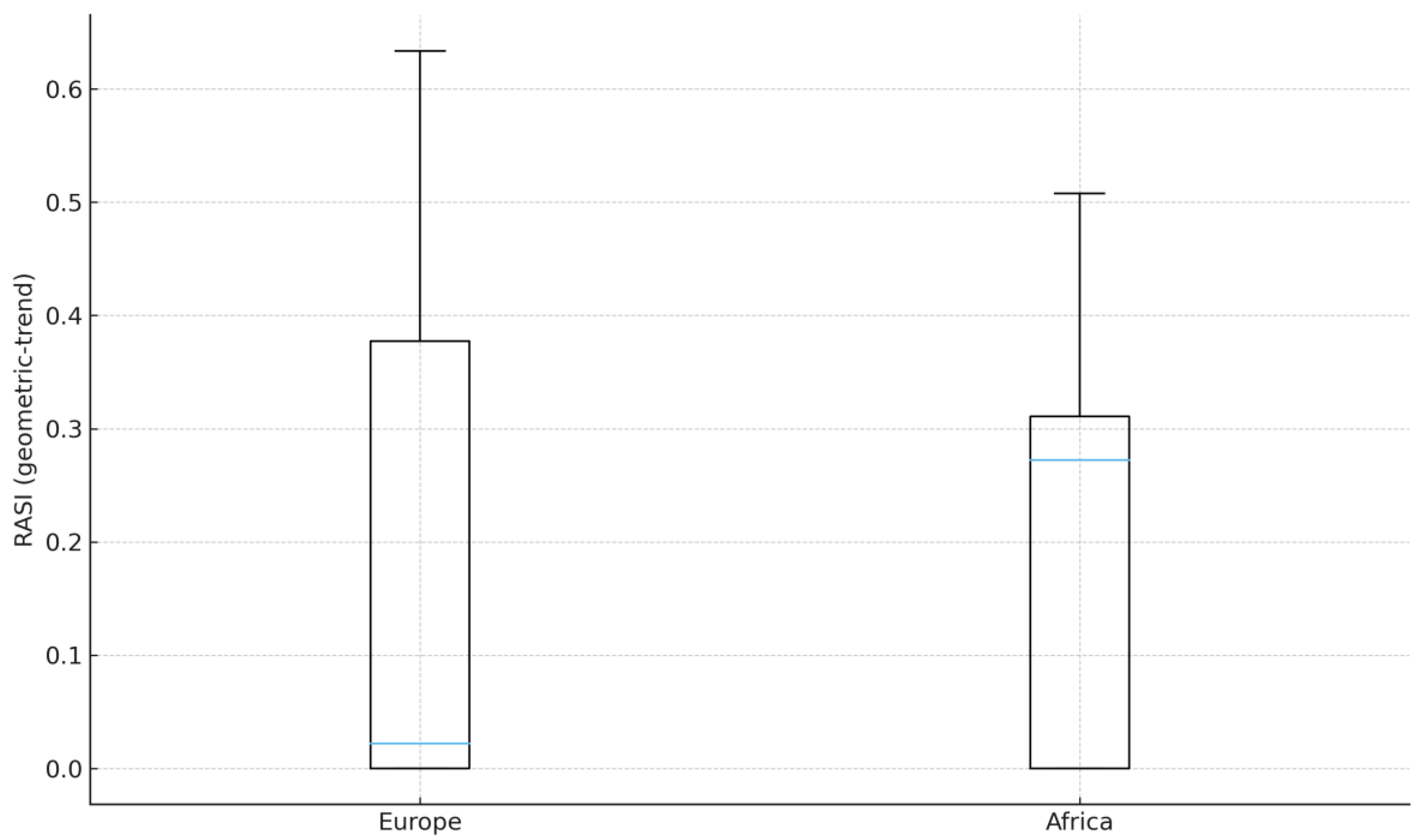

Figure 1.

Distribution of country RASI by continent, 2007-2021. Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Note: Ns: Africa 21, Europe 29 (inclusion ≥ 8 years). Geometric-trend baseline; risk = population SD of levels. Keep the interpretation in the text (do not include an “upper-tail” claim in the caption).

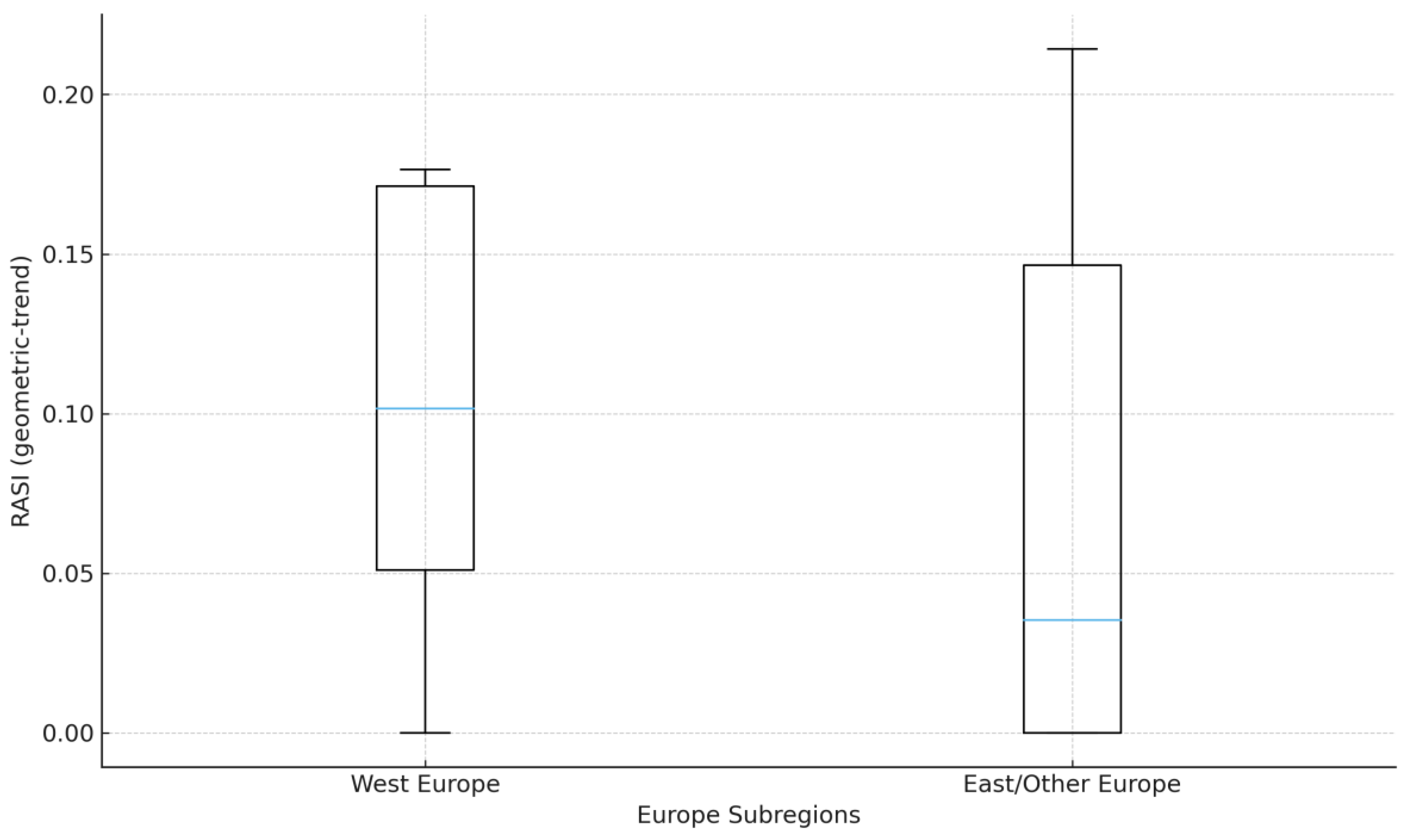

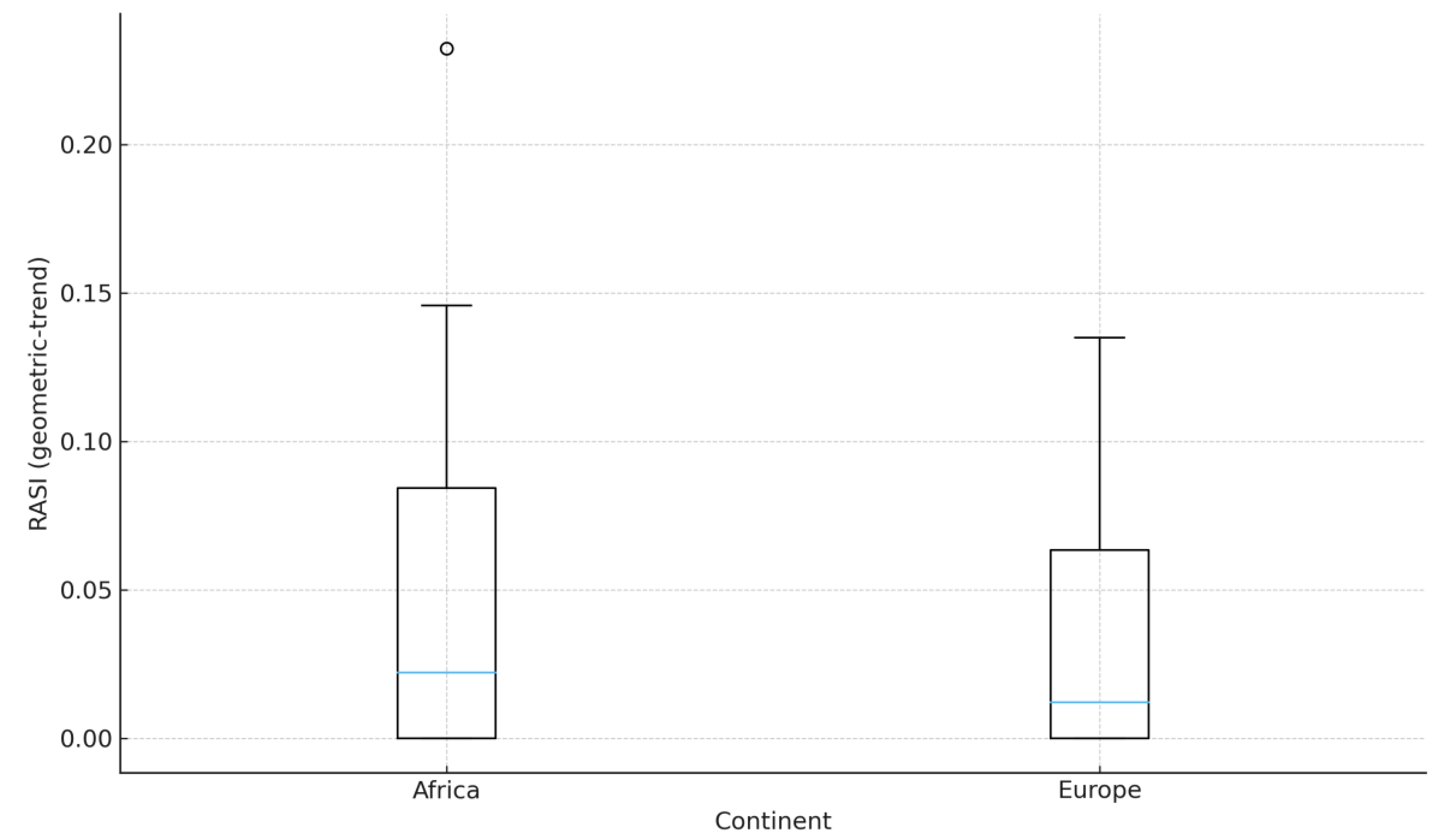

Figure 2.

Europe: West vs East/Other country RASI, 2007-2021. Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Ns: West 7, East/Other 22 (inclusion ≥ 8 years). Geometric-trend baseline; risk = population SD of levels.

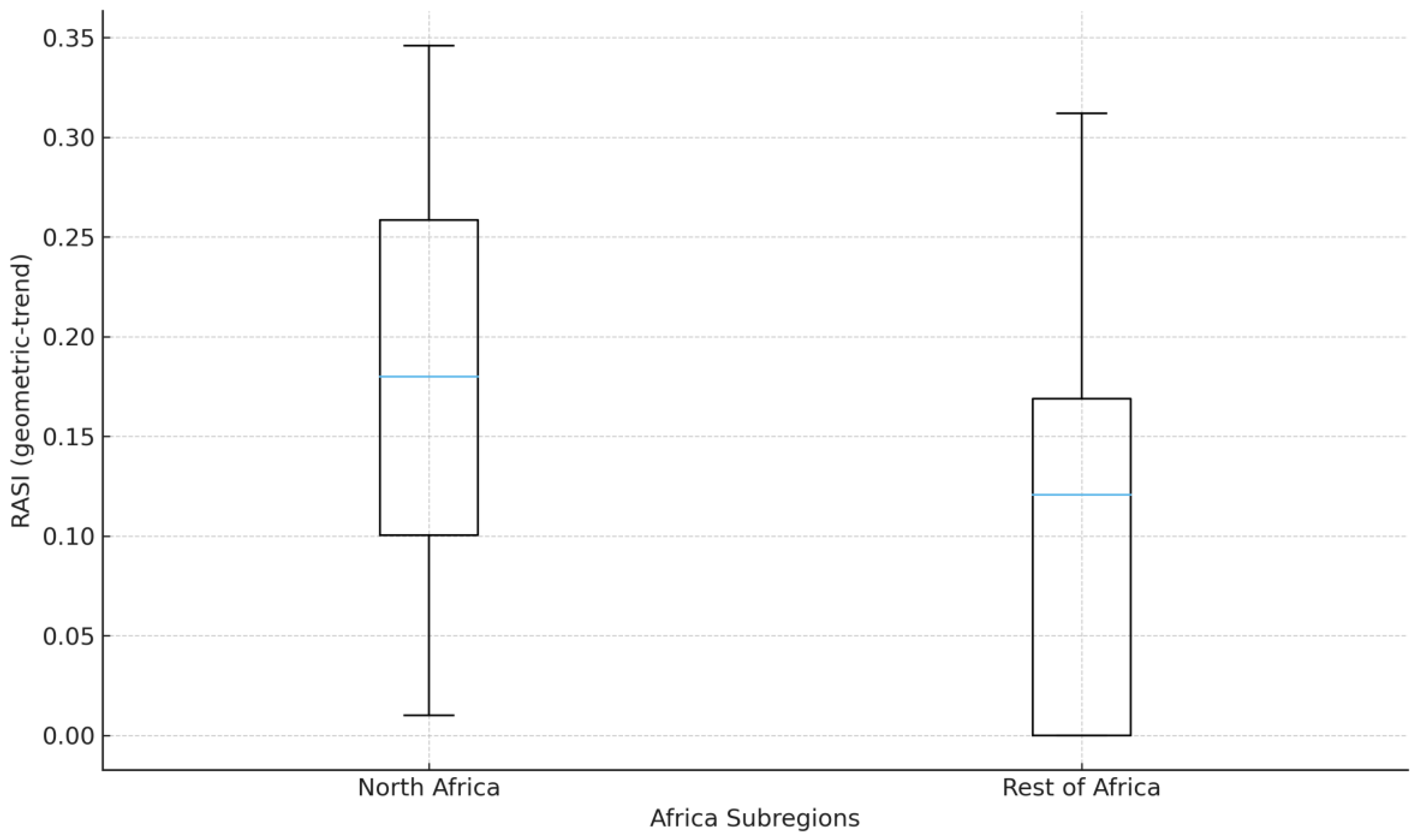

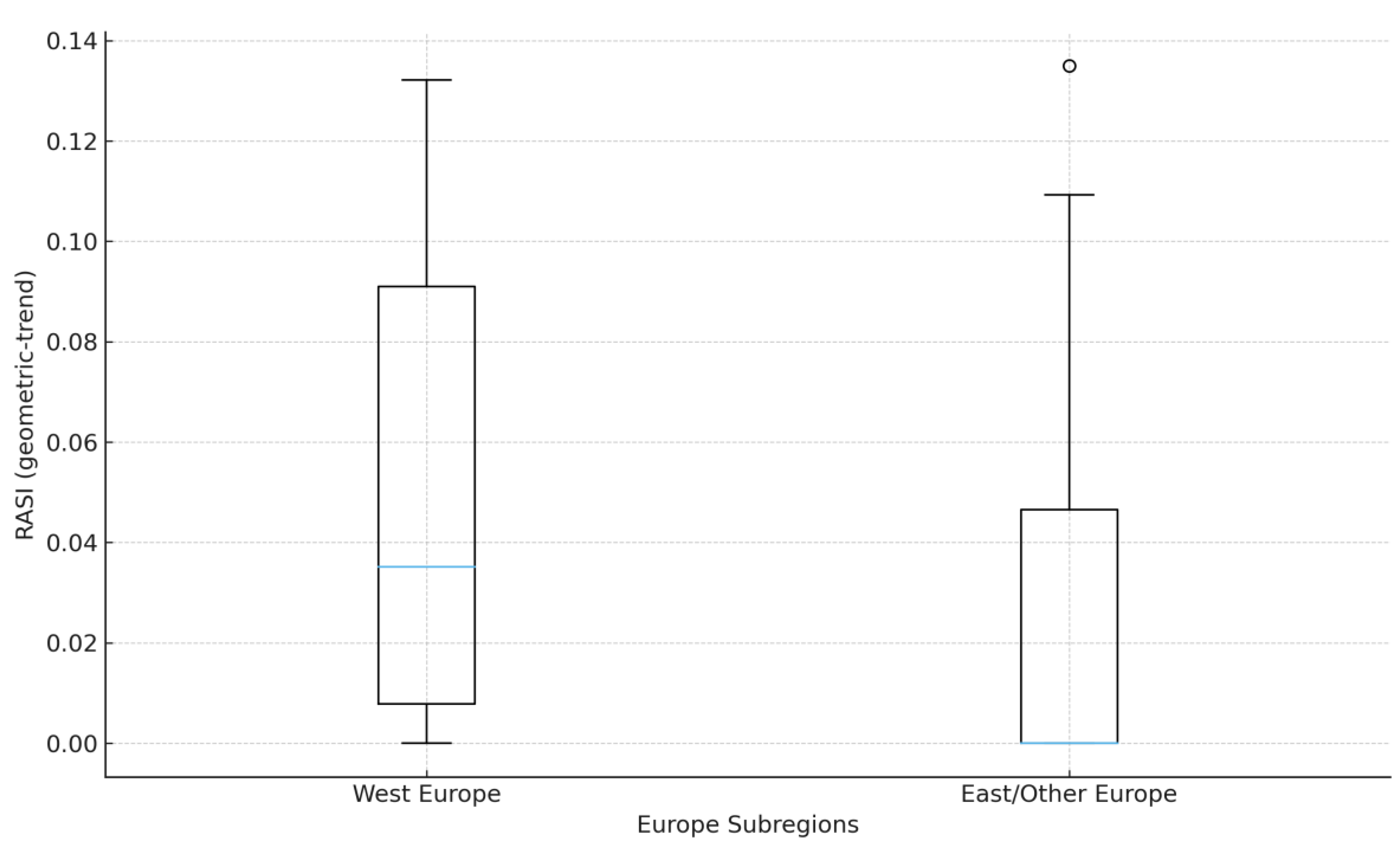

Figure 3.

Africa: North vs Rest country RASI, 2007-2021. Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Ns: North 4, Rest 17 (inclusion ≥ 8 years). Geometric-trend baseline; risk = population SD of levels.

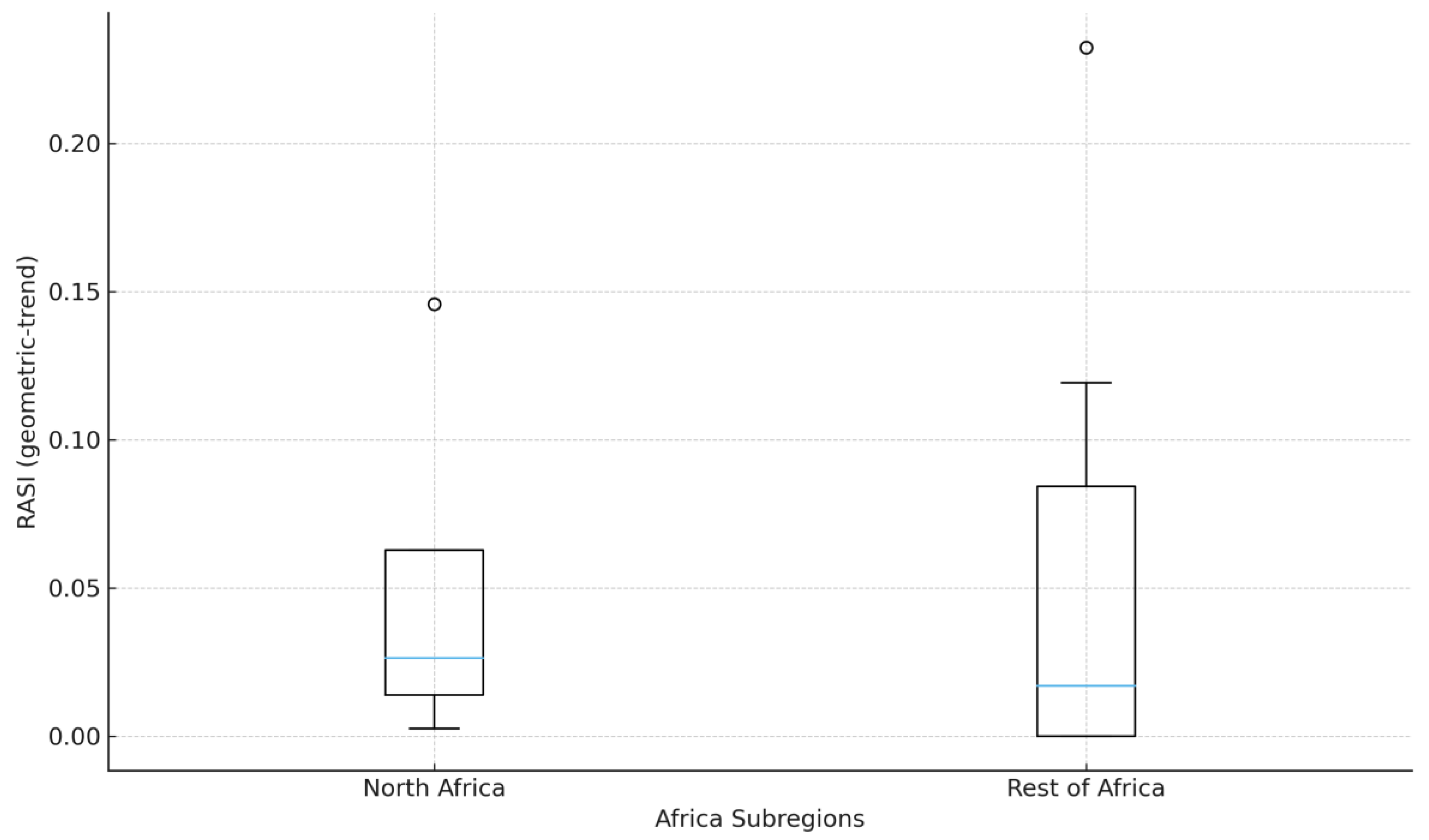

Within Africa, North Africa’s distribution is shifted upward relative to the Rest of Africa, with broadly similar dispersion; the median and IQR are 0.180 vs. 0.121 and 0.158 vs. 0.169, respectively (

Table 3), indicating a difference in central tendency rather than spread. This is visually consistent with

Figure 3, which confirms the sample sizes (North = 4; Rest = 17; inclusion ≥ 8) and baseline specification (geometric trend; risk = population SD). The ordering persists in the extended window (

Appendix Table A2 and

Figure A3), supporting external validity beyond the 2007-2021. Moreover, rank concordance is high under alternative risk normalizations (MAD-scaled, IQR-scaled, downside semi-deviation); therefore, the North vs Rest relation is not sensitive to the choice of dispersion metric (

Figure 6). For the uncertainty context, bootstrap rank intervals and Top-1 leadership probabilities (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) and jackknife stability (

Figure 11) corroborate clear separation at the top without outsized sensitivity to single-year deletions; subperiod splits (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) preserve ordering.

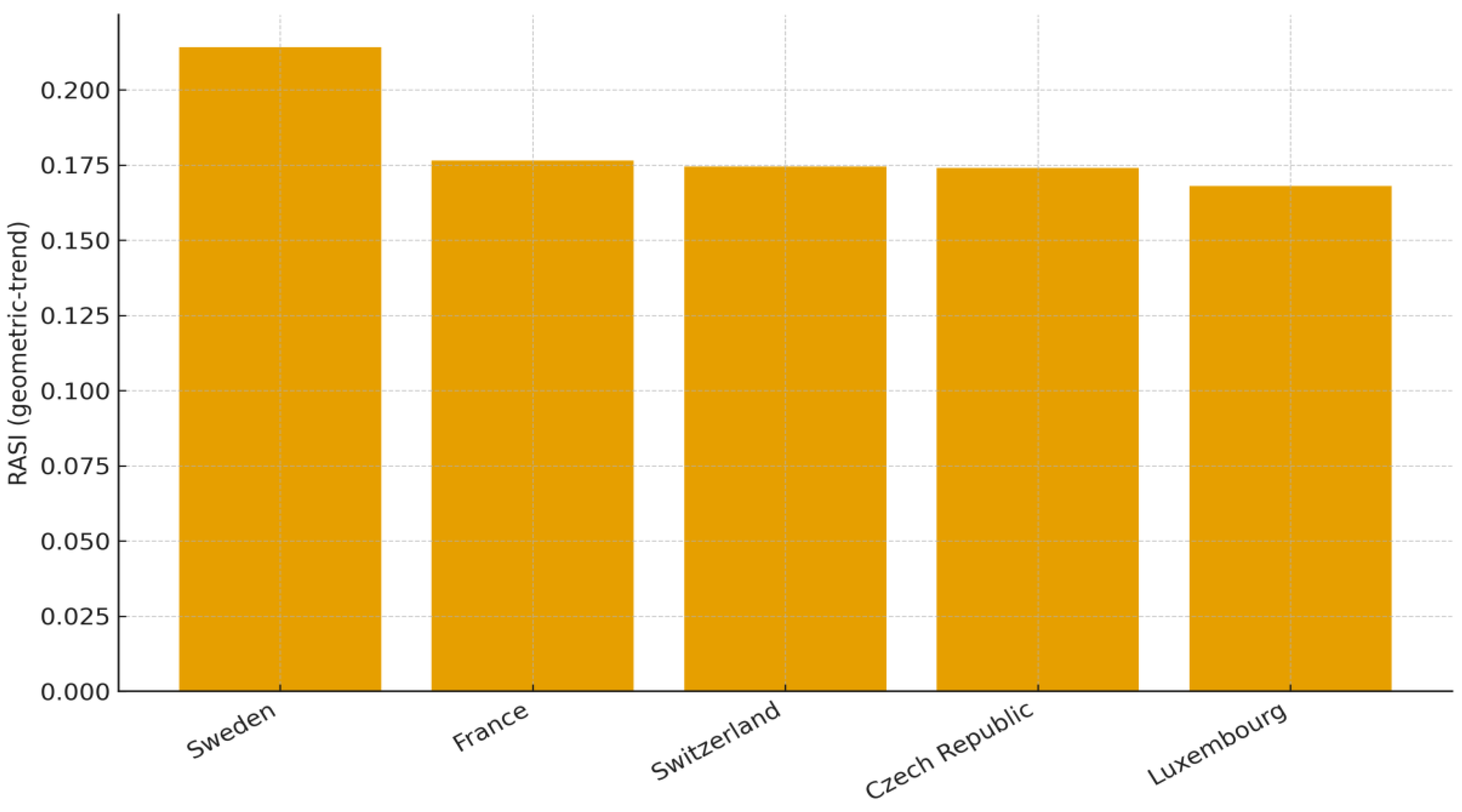

Figure 4.

Top 5 countries in Europe by RASI (geometric trend), 2007-2021. Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: See

Figure 7 for bootstrap rank intervals; Ns: Europe 29 (inclusion age ≥ 8 years).

Within Europe, the Top-5 under the geometric-trend baseline (2007-2021) are Sweden, France, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, and Luxembourg (

Figure 4). The common signature among these leaders is elevated average Z-score levels, credibly positive trend, and comparatively low volatility, consistent with the mechanics of RASI; the figure notes confirm Europe N = 29 with inclusion ≥ 8 years and direct readers to the uncertainty diagnostics. Precision and robustness: Bootstrap rank intervals are tight at the top (

Figure 7), and under the Theil-Sen(log) trend, the identity of leaders and the overall stratification remain unchanged (

Figure 8), indicating estimator-invariant leadership. Leadership probabilities concentrate on a small set of countries (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), corroborating clear separation at the top, while rank concordance across alternative risk normalizations is very high in Europe (Spearman ρ ≈ 0.97-0.98), so conclusions are not sensitive to the dispersion metric (

Figure 6). For stability to single-year deletions, jackknife CVs were low for the leaders (

Figure 11). Taken together, in light of the broader within-Europe distributional gap (

Table 2;

Figure 2), these diagnostics support a durable Top-5 rather than a sample-specific artifact.

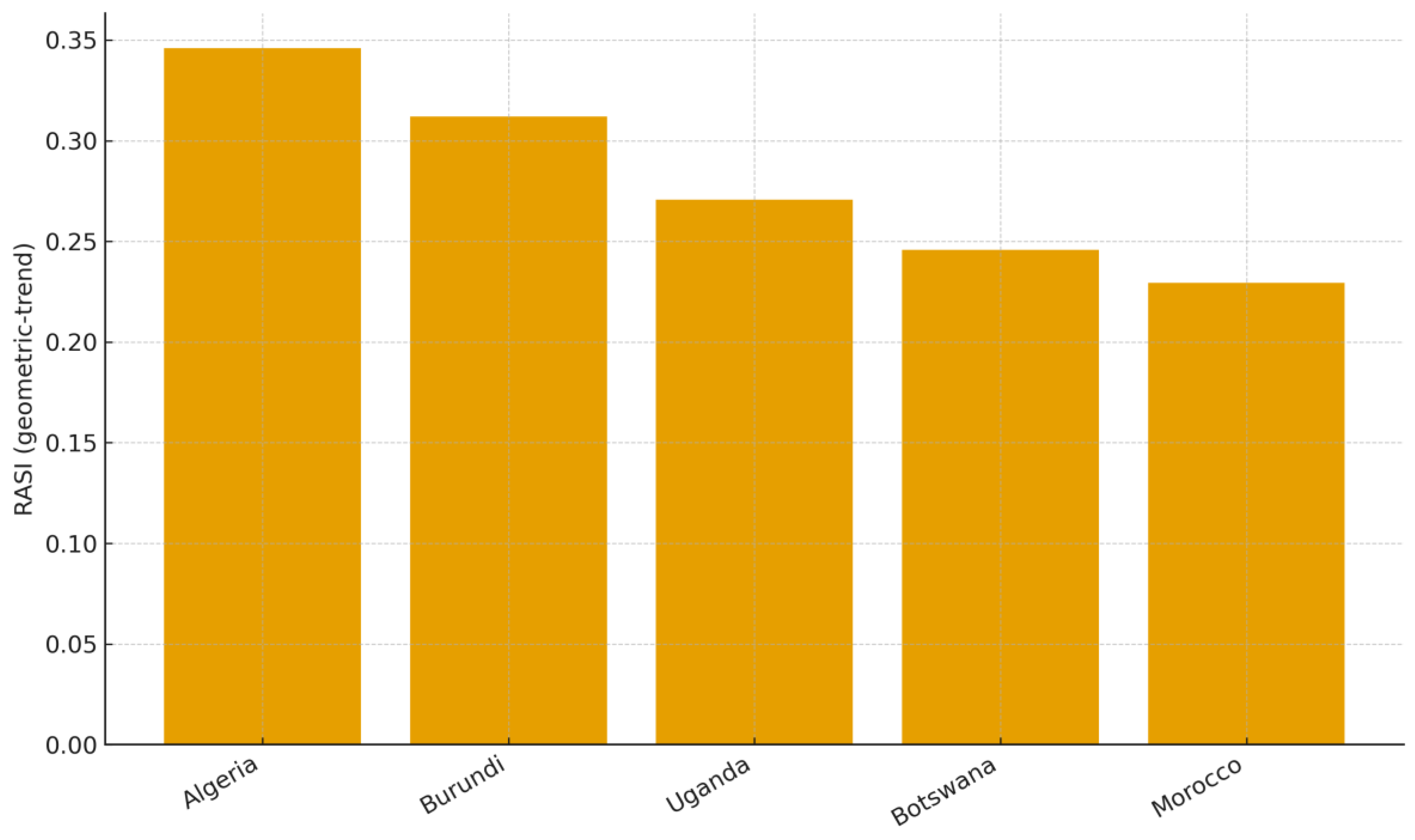

Figure 5.

Top-5 countries in Africa by RASI (geometric-trend), 2007-2021. Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: See

Figure 7 for bootstrap rank intervals. Ns: Africa 21 (inclusion ≥ 8 years).

Within Africa, the Top-5 under the geometric-trend baseline (2007-2021) are Algeria, Burundi, Uganda, Botswana, and Morocco (

Figure 5; Ns: Africa = 21; inclusion ≥ 8). The leadership pattern is consistent with RASI mechanics, elevated average Z-score levels, and non-negative (often positive) trends, scaled by contained dispersion, although the figure itself summarizes the composite rather than the components. Precision and robustness checks support these findings: bootstrap rank intervals are tight at the top (

Figure 7) and remain under the Theil-Sen(log) trend (

Figure 8), indicating estimator-invariant leadership. Top-1 leadership probabilities concentrate on a small set of countries (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), corroborating clear separation at the top, while rank concordance across alternative risk normalizations is high in Africa (ρ≈0.90-0.93), so conclusions are not sensitive to the dispersion metric (

Figure 6). For stability to single-year deletions, jackknife coefficients of variation were low for the leaders (

Figure 11). Subperiod splits (2007-2013 and 2014-2021) preserve continent-level ordering, reinforcing external validity across regimes (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

3.1. Ranking Robustness and Stability

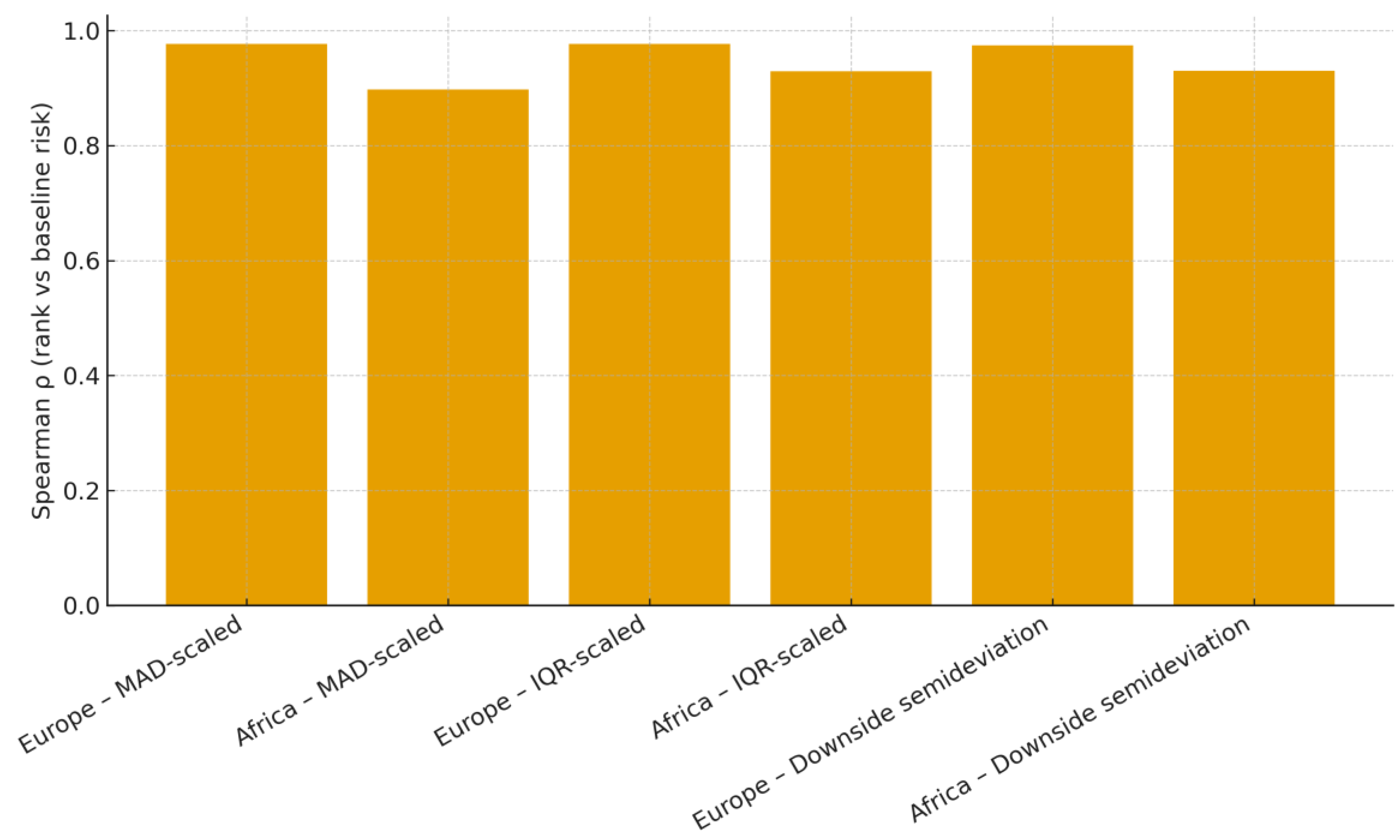

Figure 6.

Rank concordance across risk normalizations (Spearman ρ vs baseline, 2007-2021). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Spearman ρ computed within continent against baseline (population-SD) risk; alternatives: MAD-scaled, IQR-scaled, downside semi-deviation.

Figure 6.

Rank concordance across risk normalizations (Spearman ρ vs baseline, 2007-2021). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Spearman ρ computed within continent against baseline (population-SD) risk; alternatives: MAD-scaled, IQR-scaled, downside semi-deviation.

Rank concordance across alternative risk normalizations is high within continents, indicating that the ordering is largely invariant to the choice of the dispersion metric. In Europe, Spearman ρ versus the baseline (population-SD risk) is 0.98 (MAD-scaled), 0.98 (IQR-scaled), and 0.97 (downside semi-deviation); in Africa, it is 0.90, 0.93, and 0.93, respectively (

Figure 6; notes: ρ computed within continent against the baseline). This aligns with the study design in which rank concordance is the primary check for risk-metric sensitivity (Methods §2.8; Algorithmic Summary step 8) and supports the interpretation of the baseline results as representative of reasonable alternatives. For the precision and stability context, see the bootstrap rank intervals and leadership probabilities (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) and jackknife stability (

Figure 11), which complement

Figure 6 by quantifying uncertainty and year-deletion sensitivity.

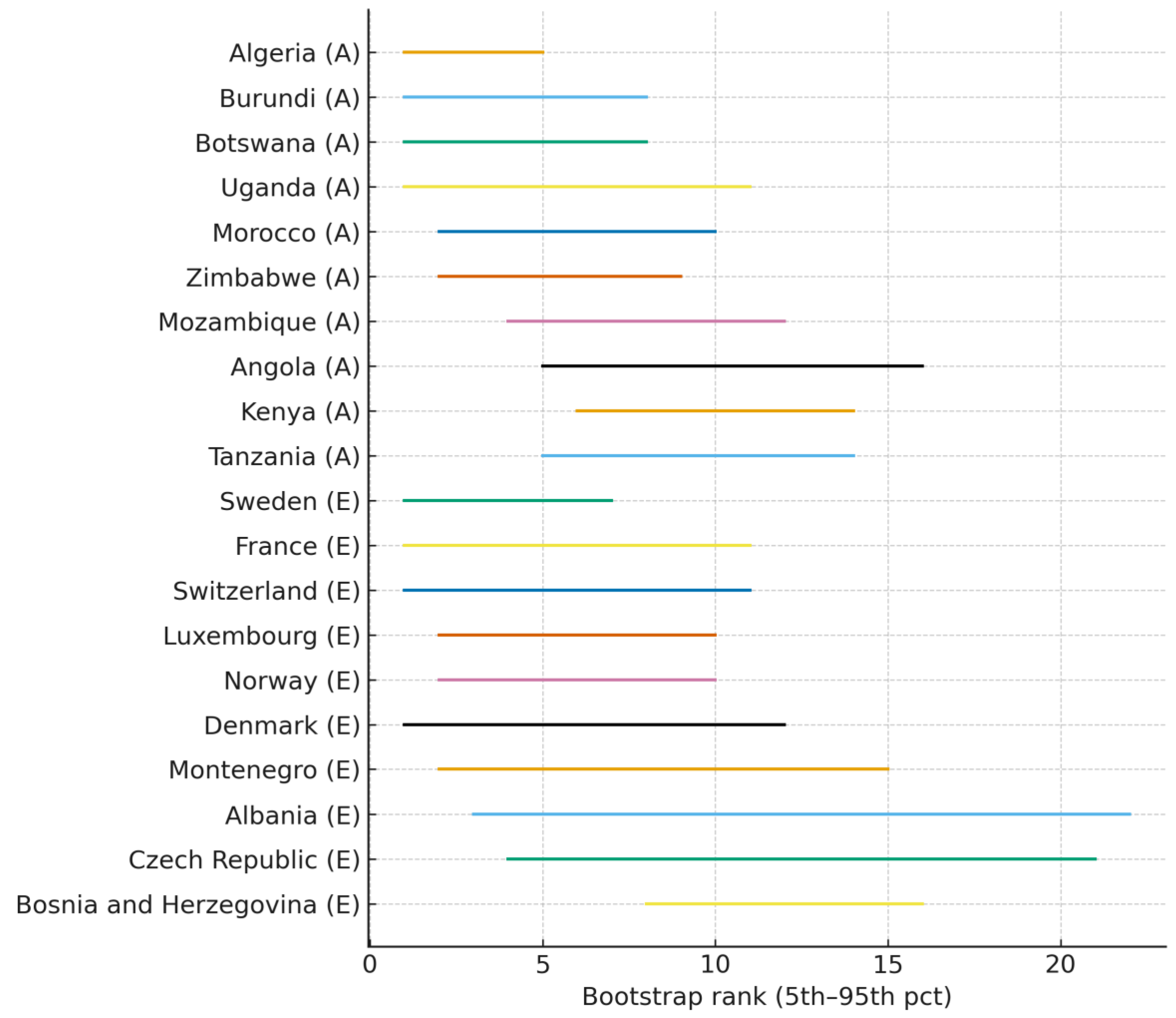

Figure 7.

Bootstrap rank intervals - Geometric growth (B=1000; top 10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; Ns-Africa 21, Europe 29 (inclusion of ≥ 8 years). The intervals are the 5th–95th percentiles of the rank distributions.

Figure 7.

Bootstrap rank intervals - Geometric growth (B=1000; top 10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; Ns-Africa 21, Europe 29 (inclusion of ≥ 8 years). The intervals are the 5th–95th percentiles of the rank distributions.

Bootstrap rank intervals (geometric trend) indicate a clear separation at the top and denser mid-ranking competition. Within a country, over-years clustered bootstrap with B = 1000 (seeded for reproducibility), 5

th-95

th percentile rank intervals for the Top-10 countries per continent are tight for leaders and widen lower in ranking, implying higher precision at the top and greater uncertainty among mid-ranked systems (

Figure 7; Ns: Africa = 21, Europe = 29; inclusion ≥ 8 years). This diagnostic directly complements the methods in §2.5, and the algorithmic summary (step 6), which defines the clustered bootstrap and interval construction. Robustness across estimators is evident in

Figure 8, where Theil-Sen(log) yields qualitatively similar intervals; leadership probabilities in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 concentrate mass on a small set of countries, reinforcing the separation signaled by narrow top-rank intervals, and jackknife CVs in

Figure 11 show that the top systems’ scores are not driven by single-year deletions.

Figure 8.

Bootstrap rank intervals Theil-Sen(log) growth (B=1000; top-10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; same sample as

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Bootstrap rank intervals Theil-Sen(log) growth (B=1000; top-10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; same sample as

Figure 7.

Bootstrap rank intervals under the Theil-Sen (log) trend confirm the geometric-baseline results. Using B=1000 within-country, over-years clustered resamples, the 5

th-95

th percentile rank intervals for the top 10 countries per continent closely matched those in

Figure 7, and the identity of leaders and overall stratification remained unchanged (

Figure 8; ns: Africa = 21, Europe = 29; inclusion ≥ 8 years). The Theil-Sen estimator’s endpoint robustness reduces sensitivity to idiosyncratic years, so the close agreement with the geometric version indicates estimator-invariant rankings rather than dependence on a particular trend metric. The resampling design follows methods §2.5, and the Algorithmic Summary (step 6), which defines the clustered bootstrap and rank-interval construction; Theil-Sen (log) is introduced in methods §2.2. In addition, leadership probabilities (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) concentrate on a small set of countries, and jackknife stability (

Figure 11) shows low CVs for leaders, both reinforcing the precision signaled by narrow top-rank intervals.

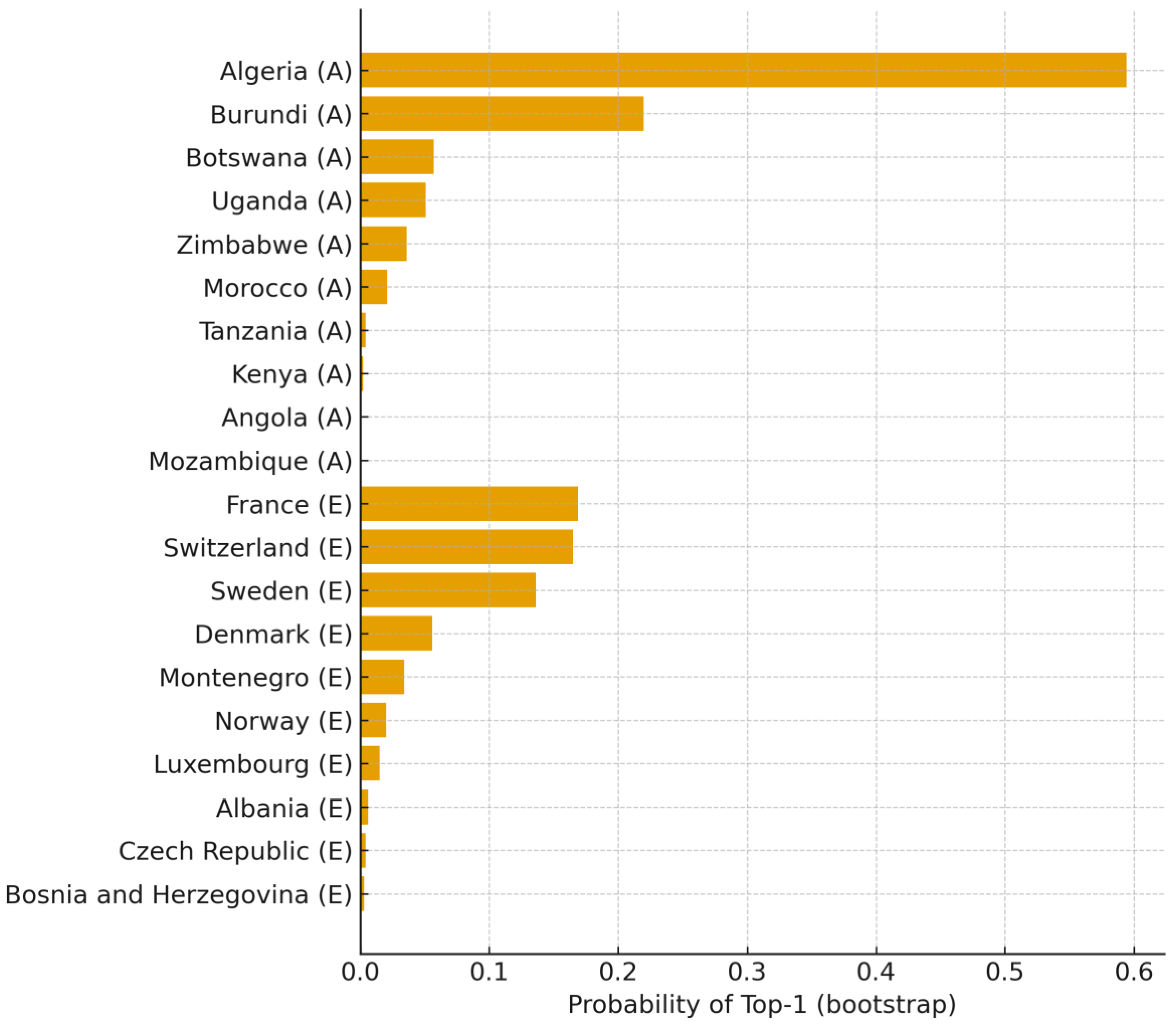

Figure 9.

Probability of Top-1 rank Geometric growth (B=1000; top-10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; Ns: Africa, 21; Europe, 29 (inclusion ≥ 8 years).

Figure 9.

Probability of Top-1 rank Geometric growth (B=1000; top-10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; Ns: Africa, 21; Europe, 29 (inclusion ≥ 8 years).

Top-1 leadership probabilities (geometric trend) are concentrated in a very small set of countries, with most others near zero. Using a within-country, over-years clustered bootstrap (B = 1000; Ns: Africa = 21, Europe = 29; inclusion ≥ 8 years),

Figure 9 shows that only a handful of systems capture meaningful probability masses of P (rank= 1), implying a clear separation at the top. This pattern is consistent with the narrow top-rank intervals in

Figure 7 and remains estimator-invariant under the Theil-Sen(log) trend (

Figure 10). In the stability context, jackknife CVs are low for leading countries (

Figure 11), and the sub-period splits (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) preserve leadership ordering, reinforcing that these probabilities are not artifacts of a single period. The alignment with the Top-5 line-ups in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 further corroborates that the countries with the highest Top-1 probabilities are the same ones that consistently lead the rankings.

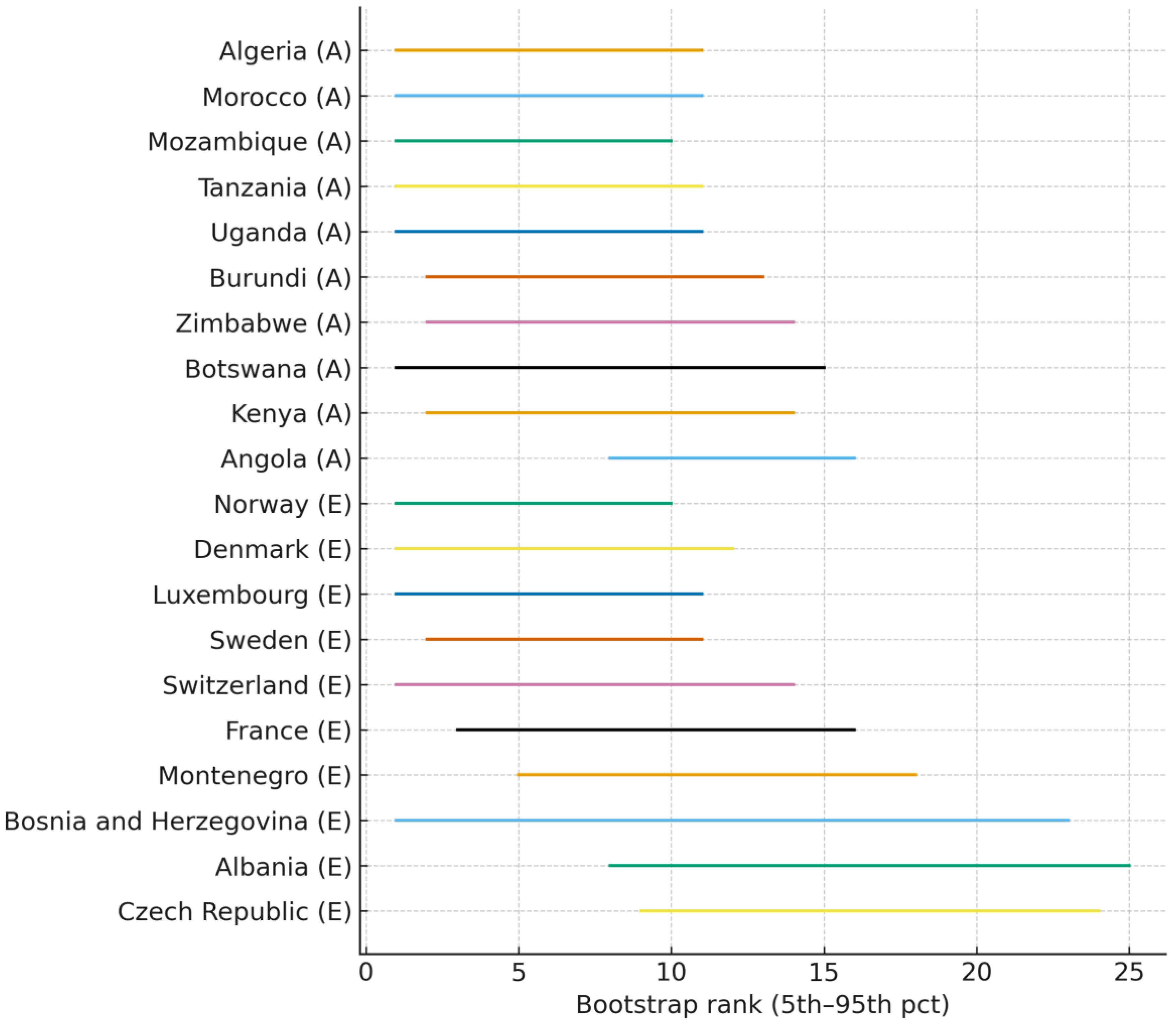

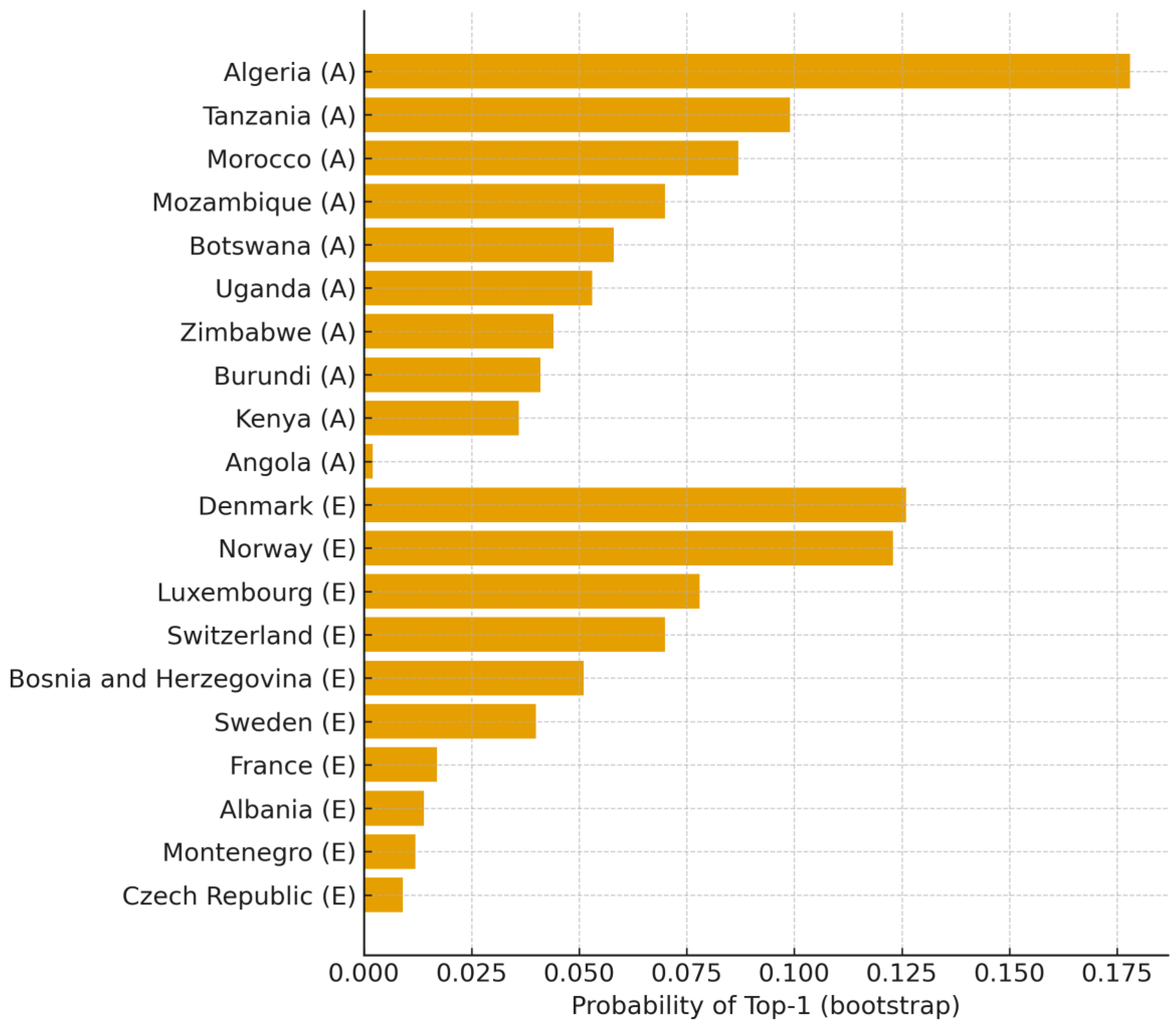

Figure 10.

Probability of Top-1 rank Theil-Sen(log) (B=1000; top-10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; Ns: Africa, 21; Europe, 29 (inclusion ≥ 8 years).

Figure 10.

Probability of Top-1 rank Theil-Sen(log) (B=1000; top-10 per continent). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Within-country, clustered bootstrap; Ns: Africa, 21; Europe, 29 (inclusion ≥ 8 years).

Top-1 leadership probabilities under the Theil-Sen(log) trend concentrate on a very small set of countries and closely mirror the geometric-trend benchmark, indicating that the identification of leading systems is estimator-invariant.

Figure 10 was computed via a within-country, over-years clustered bootstrap (B = 1000; Ns: Africa = 21, Europe = 29; inclusion ≥ 8 years), the same design used for the geometric version in

Figure 9. This aligns with the resampling protocol in the methods (clustered bootstrap and top-k probabilities; Algorithmic Summary step 6) and the role of Theil-Sen(log) as an endpoint-robust trend estimator. Consistency with the rank-interval diagnostics is evident:

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show narrow top-rank intervals under both trend estimators, and the concentration of the Top-1 mass in

Figure 10 reinforces this separation. For stability to single-year deletions,

Figure 11 reports low jackknife CVs among leaders, supporting the durability of leadership probabilities.

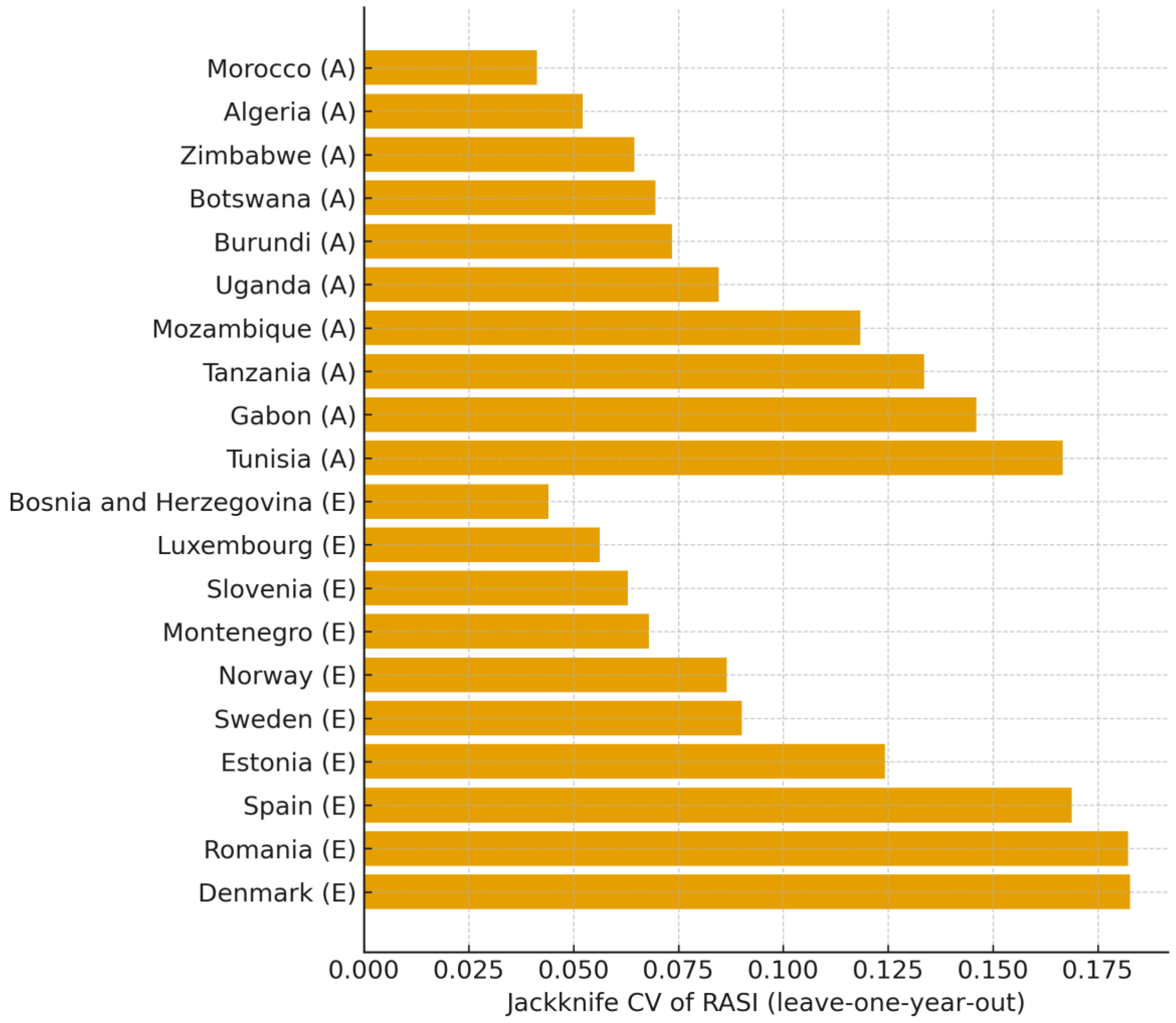

Figure 11.

Jackknife Stability—Coefficient of Variation of Leave-One-Year-Out RASI (Geometric Baseline). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: CV = sd(RASI_{−τ}) / mean(RASI_{−τ}); geometric-trend baseline.

Figure 11.

Jackknife Stability—Coefficient of Variation of Leave-One-Year-Out RASI (Geometric Baseline). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: CV = sd(RASI_{−τ}) / mean(RASI_{−τ}); geometric-trend baseline.

Jackknife stability indicates that top-ranked countries are not driven by single-year idiosyncrasies. Under the geometric-trend baseline,

Figure 11 shows the coefficient of variation from a leave-one-year-out jackknife, CV = sd_τ(RASI_{−τ}) / mean_τ(RASI_{−τ}). Leaders show low CVs, while middle-rank countries exhibit higher CVs, implying greater sensitivity to episodic shocks. This diagnostic implements the protocol in Methods §2.6 and the Algorithmic Summary (step 7), and should be read alongside the bootstrap evidence on precision and leadership.

Cross-validation with other diagnostics. Narrow bootstrap rank intervals at the top (

Figure 7) and their close match under Theil-Sen(log) (

Figure 8) corroborate high precision for leaders; Top-1 leadership probabilities (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) concentrate mass on a small set of countries, consistent with low jackknife CVs among those leaders. Subperiod splits (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) preserve continent-level ordering, supporting external validity across regimes, and rank concordance under alternative risk normalizations (

Figure 6) shows that conclusions are not sensitive to the dispersion metric.

Figure 12.

Subperiod RASI 2007-2013 (Geometric baseline; continent distributions). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Subperiod inclusion rule: ≥5 valid years.

Figure 12.

Subperiod RASI 2007-2013 (Geometric baseline; continent distributions). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Subperiod inclusion rule: ≥5 valid years.

Subperiod 2007-2013 preserves the full-sample continent ordering: Africa’s distribution remains above Europe’s, with wider dispersion consistent with crisis-period volatility, not a reversal of the hierarchy (

Figure 12). The sub-period analysis applies the ≥ 5 valid-years inclusion rule (Methods §2.7), ensuring coverage while testing for invariance across regimes. This result is consistent with the 2007-2021 baseline (

Table 1;

Figure 1) and is corroborated by the 2014-2021 split (

Figure 13), supporting external validity across distinct macro-financial environments; the same ordering also holds in the extended 2000-2021 window (Appendix

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3 and

Figure A1,

Figure A2 and

Figure A3).

Figure 13.

Subperiod RASI 2014-2021 (Geometric baseline; continent distributions). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Subperiod inclusion rule: ≥5 valid years.

Figure 13.

Subperiod RASI 2014-2021 (Geometric baseline; continent distributions). Source: Author’s calculation (based on World Bank DataBank data), 2025. Notes: Subperiod inclusion rule: ≥5 valid years.

Subperiod 2014-2021 preserves the full-sample continent ordering, with Africa’s distribution remaining above Europe’s and only modest shifts in medians and IQRs relative to the baseline window (

Figure 13). The sub-period analysis applies the ≥ 5 valid-years inclusion rule (Methods §2.7), ensuring coverage while testing for invariance across regimes. This result mirrors the 2007-2013 split (

Figure 12) and is consistent with the 2007-2021 baseline (

Table 1;

Figure 1), supporting external validity beyond crisis-era conditions. The replication of the extended 2000-2021 window (Appendix

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3 and

Figure A1,

Figure A2 and

Figure A3) corroborates the persistence of the cross-continental hierarchy. Complementary diagnostics, high within-continent rank concordance across risk normalizations (

Figure 6), and bootstrap/jackknife evidence (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11), reinforce that these conclusions are insensitive to the dispersion metric and robust to sample variation.