Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Biomarkers of ICIs and Their Limitations

| Biomarker | Methods | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) [5] | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | widely available; quick turnaround; validated in several cancer types | Multiple FDA-approved companion assays (22C3, 28-8, SP142, SP263) with different score cut-off for ICIs and cancer types; subject to tumor heterogeneity and sampling bias |

| Mismatch repair (MMR) [6,7,8] |

PCR or next generation sequencies (NGS) for MSI status; IHC for MMR proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6) |

FDA approved MSI-high (MSI-H) or dMMR status as a tissue-agnostic biomarker; strong predictive value | Rare in solid tumors (~3-16%); limited availability of validated MSI assays in some centers |

| Tumor mutational burden (TMB) [9,10] | NGS | FDA approved TMB ≥10 mut/Mb by FoundationOne CDx as a tissue-agnostic biomarker for pembrolizumab; reflects overall neo-antigen landscape | Expensive and longer turnaround time; optimal cut-off may vary across cancer types; lack of standardized assessment methods |

| POLE/POLD1 Mutations [11,12] |

NGS | Associated with an ultra-hypermutated phenotype and exceptionally high TMB | Not FDA approved; rare in solid tumors (~4%) |

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [13] | H&E pathology slide evaluation | Reflects actual immune response within tumor; assessable on routine pathology slides |

Not FDA-approved; lack standardized scoring; subject to spatial and temporal heterogeneity |

3. The Microbiome: A Key Environmental Factor in Immunity

3.1. Acquisition and Distribution

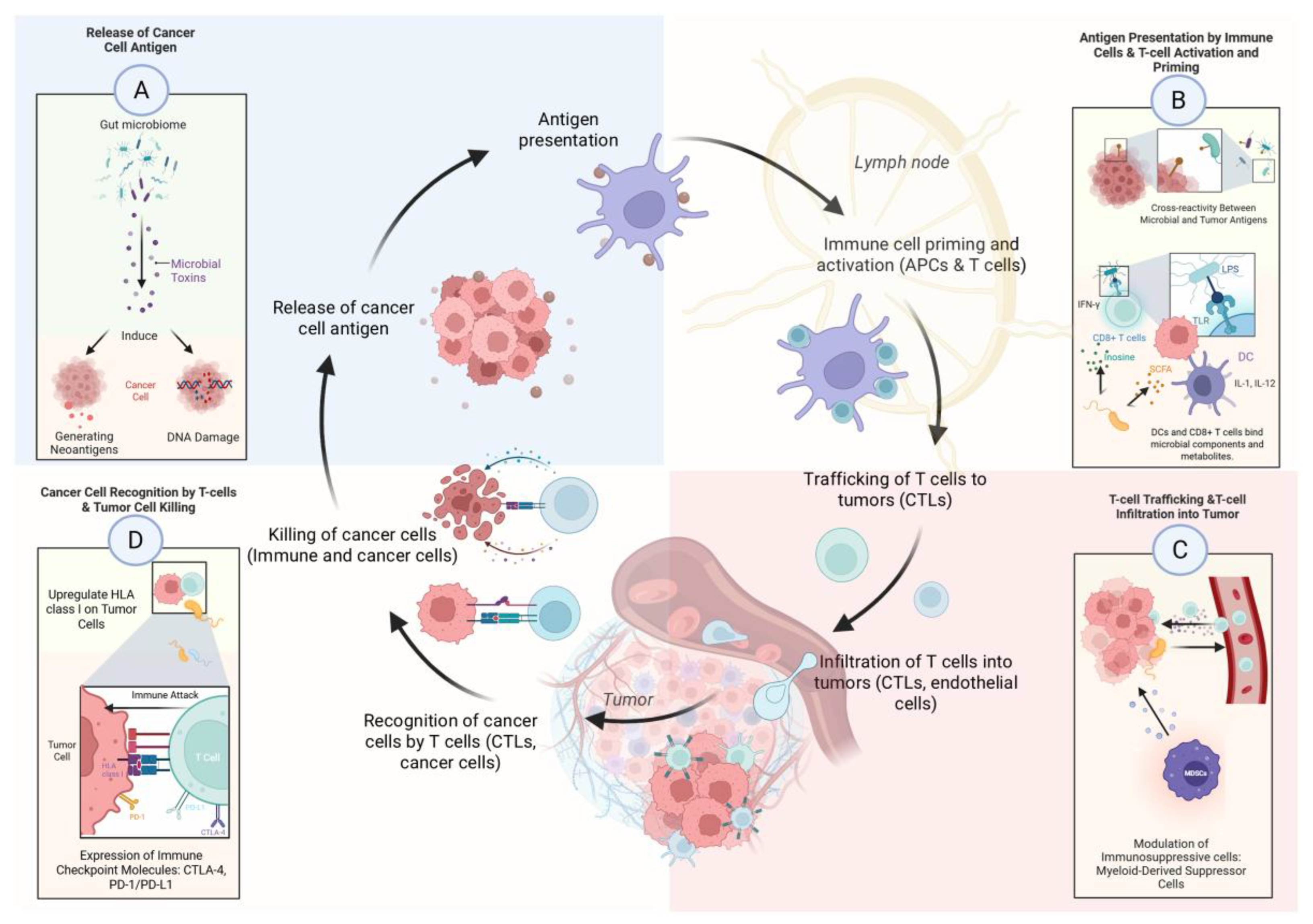

3.2. How the Gut Microbiome Modulates Anti-Tumor Immunity

| Innate immunity | |

| |

| Examples of microbiome interactions across the cancer-immunity cycle | |

| Release of cancer cell antigens | |

| Antigen Presentation by Immune Cells & T-cell Activation and Priming | |

| T-cell Trafficking & T-cell Infiltration into the Tumor |

|

| Cancer Cell Recognition by T-cells & Tumor Cell Killing |

|

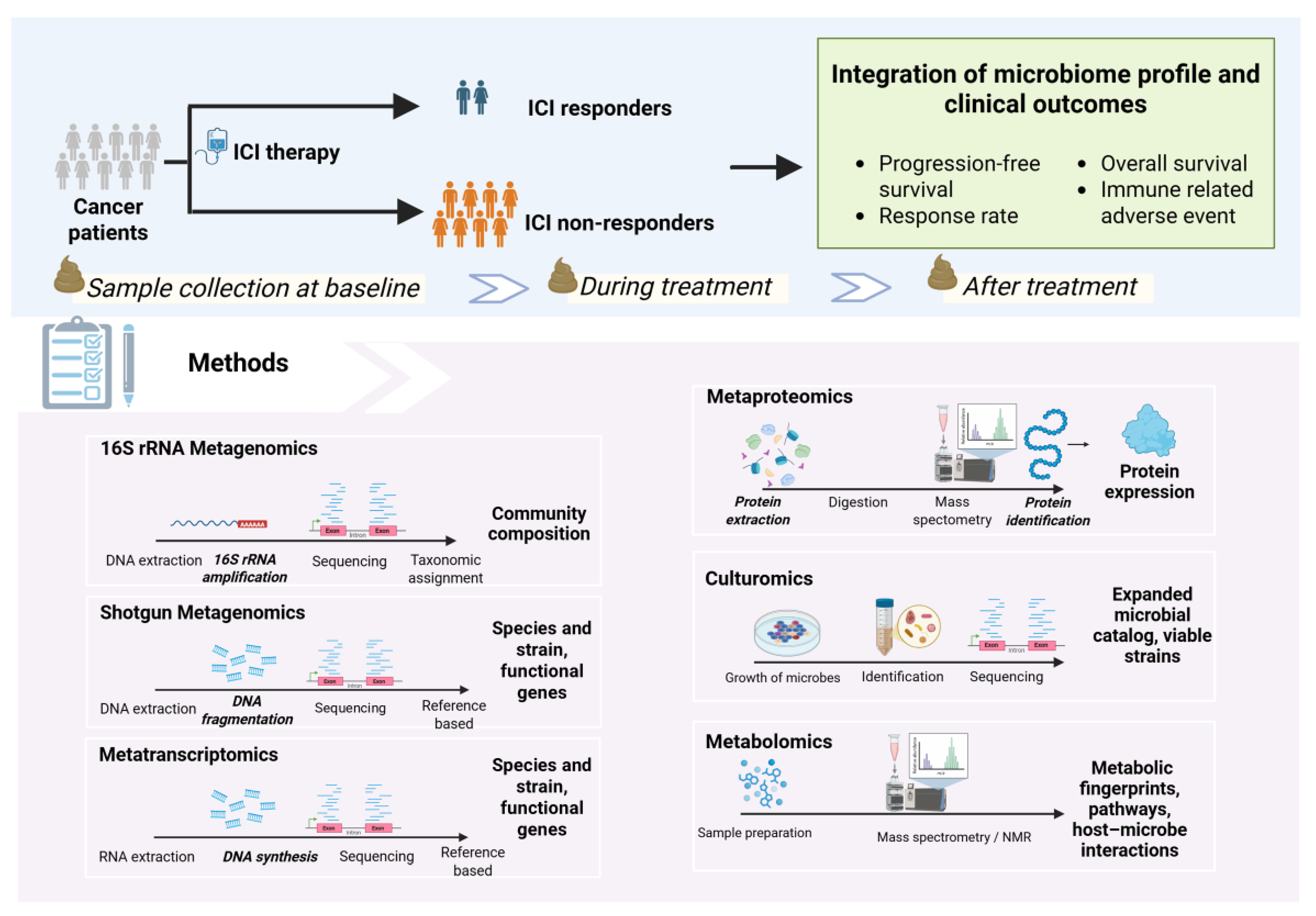

4. Analysis of Gut Microbiome and Response to ICIs

4.1. Analysis Pipeline Overview

4.2. Sample Types for Microbiome Profiling

4.2.1. Fecal Samples

4.2.2. Oral Samples

4.2.3. Direct Gut Sampling (Swab, Biopsy and Swallowable Capsules)

4.2.4. Tumor Samples

4.3. Relative vs. Absolute Quantification of Microbiome

- Relative abundance: This is the default output of standard sequencing that measures the proportion of each microbe within a sample (e.g., Bacteroides make up 20% of the community). While widely used, this approach is prone to compositionality bias–an increase in one taxon will automatically appear as a decrease in others, even if their absolute numbers remain unchanged [65,66].

- Absolute abundance: This measures the actual number or concentration of microbes (e.g., 109 CFU/g of Lactobacillus). This method avoids compositional bias by integrating sequencing data with other techniques, such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), flow cytometry, or the addition of synthetic spike-in standards (reference DNA or microbes added in known quantities for calibration). This provides a true measure of microbial load, which is critical for accurate biological interpretation [67,68].

4.4. Methods for Microbiome Analysis

4.4.1. Sequencing-Based Methods

- 16S rRNA gene sequencing: This cost-effective method targets the 16s rRNA gene, a universal “barcode” present in all bacteria. The 16S rRNA gene contains conserved regions that serve as universal primer binding sites, as well as hypervariable regions that are species-specific and allow for taxonomic classification [71]. It provides a broad overview of community composition, typically at the genus level. While excellent for assessing overall diversity, its lower resolution makes species- or strain-level identification challenging [72,73]. Recent advances in full-length 16S rRNA sequencing have improved the taxonomic resolution of this technique [74,75].

- Shotgun metagenomics: This technique sequences all genomic DNA in a sample, providing a high-resolution view of the community at the species and strain level. It can also identify fungal, viral, archaeal, and protozoan communities [76]. Additionally, this approach enables the inference of the functional and metabolic potential of microbial communities at the gene level. However, precise identification of novel functional genes may be limited by the availability and comprehensiveness of reference databases [77,78].

4.4.2. Culture- and Metabolic-Based Methods

- Culturomics: While sequencing identifies microbes by their genetic code, culturomics aims to grow them in the laboratory. By using diverse culture conditions, this technique allows for the isolation of live strains, including rare or novel bacteria that may be missed by traditional methods [81]. Culturing microbes enables functional experiments and developing next-generation probiotics [82,83]. However, microbial culturing is labor-intensive, costly, requires advanced infrastructure, and carries a risk of contamination [84].

- Metabolomics: This approach identifies and quantifies the small-molecule metabolites produced by the host and microbiome using mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [85]. Linking metagenomic data (the community’s genetic potential) with metabolomic data (its actual chemical output) can provide deep mechanistic insights [86]. However, untargeted metabolomics has some limitations, including difficulty in accurately identifying many metabolites and interference from matrix effects such as ion suppression, which can affect measurement accuracy and make comparisons between studies challenging [87,88].

4.4.3. Multi-Omics Integration: A Holistic view

5. Microbial Features Associated with ICI Response

5.1. Microbial Diversity

- Alpha diversity: The richness (number of different organisms present) and evenness (their relative abundance) within a single sample.

- Beta diversity: The degree of compositional difference between samples.

5.2. Beneficial Bacterial Taxa

5.2.1. Akkermansia muciniphila

5.2.2. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

5.2.3. Bifidobacterium Species

5.2.4. Ruminococcaceae Family

5.3. Key Microbial Metabolites

5.3.1. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

5.3.2. Inosine

5.3.3. Tryptophan Metabolites

5.3.4. Secondary Bile Acids

5.4. The Importance of Temporal Dynamics

5.5. Tools Incorporating Microbial Signature to Predict Prognosis and ICI Response

- TOPOSCORE: Developed from metagenomic data of 245 NSCLC patient feces combined with Akkermansia quantification, TOPOSCORE is a qPCR-based assay targeting 21 bacteria to evaluate personal intestinal dysbiosis. Validated in NSCLC, colorectal cancer, genitourinary cancer and melanoma patients, TOPOSCORE was able to stratify patients with improved ICI outcomes. The test can be performed within 48 hours, making it potentially suitable for routine clinical practice [137].

- miCRoScore: miCRoScore is a composite muti-omics biomarker developed from microbiome and immune gene signature of 348 colon cancer patients. It outperforms conventional prognostic biomarkers in colon cancer, including Consensus Molecular Subtypes (CMS) and microsatellite instability, in predicting survival probability. Patients classified with high mICRoScore showed an excellent 97% 5-year overall survival in the training cohort, with no colon cancer-related deaths observed in the external validation cohort. [138]

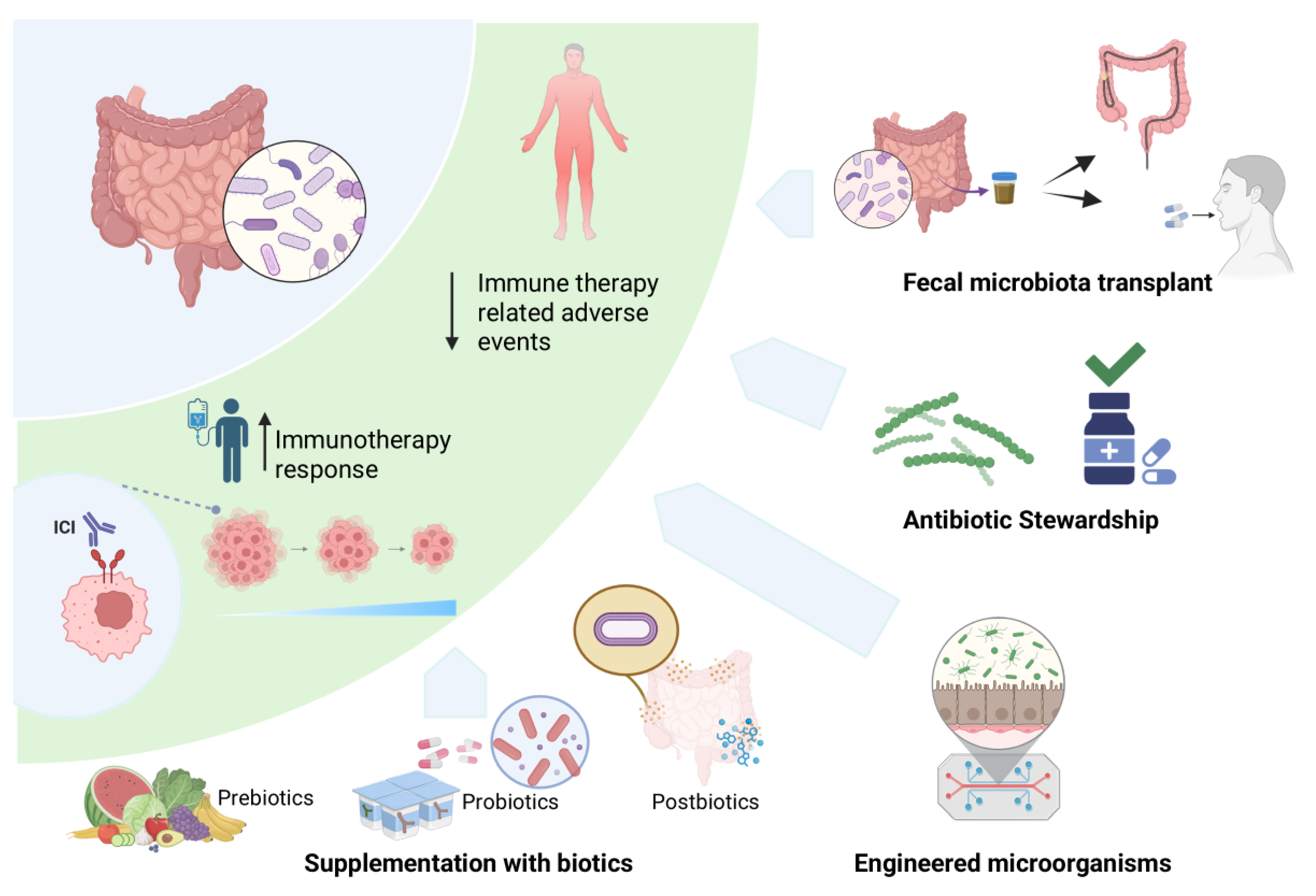

6. Therapeutic Applications of the Gut Microbiome

6.1. Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT)

6.1.1. FMT to Enhance ICI Efficacy

| Study | N | Phase | Population | Intervention | Key outcomes | Grade >3 irAEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baruch et al.(2021) [139] | 10 | I | ICI-refractory melanoma | Responder-derived FMT + Nivolumab | ORR 30%; all responders with >6 mo PFS | 0% |

| Davar et al. (2021) [140] |

15 | I | ICI-refractory melanoma | Responder-derived FMT + Pembrolizumab | ORR 20%; 3 patients with >12 mo stable disease | 0% |

| MiMic (2023) [141,142] |

20 | II | Untreated meta-static melanoma | Healthy Donor FMT + pembrolizumab or nivolumab | ORR 65%; median PFS 29.6 mo; median OS 52.8 mo | 25% |

| Kim et al. (2024) [143] |

13 | I | ICI-refractory solid cancer Gastric (n = 4), esophageal (n =5 ), HCC (n = 4) |

Responder-derived FMT + nivolumab | ORR 7.7% | 7.7% |

| RENMIN-215 (2023) [144,145] |

20 | II | Refractory meta-static MSS colo-rectal cacer, >3 lines of treatment | Responder-derived FMT + Tislelizumab + Fruquintinib | ORR 20%; median PFS 9.6 mo; median OS 13.7 mo | 10% |

| FMT- LUMINate (2024) NSCLC cohort [146] |

20 | II | Untreated meta-static cutaneous melanoma | Healthy Donor FMT + anti-PD1 | ORR 80% | 0% |

| FMT- LUMINate (2024) Melanoma Cohort [146] |

20 | II | Untreated meta-static cutaneous melanoma | Healthy Donor FMT + anti-PD1 + anti-CTLA4 | ORR 75% | 65% - Myocarditis 15% |

| TACITO (2024) [147] |

50 | II | Untreated meta-static renal cell carcinoma |

Intervention Responder-derived FMT + pembrolizumab + axitinib Control Placebo + pembrolizumab + axitinib |

ORR 54% vs. 28%Median PFS 14.2 vs. 9.2 mo;1-year PFS rate 66.7% vs. 35%;median OS NR vs. 25.3 mo | 10% |

6.1.2. FMT to Mitigate ICI-Induced Colitis

6.2. Supplementation with Biotics: A Targeted Approach

| Biotic | Definition | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebiotics | substrates that are selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit | nourish beneficial microbes, promoting their growth and metabolite production | Galactooligosaccharides (GOS), Fructooligosaccharides (FOS), Inulin, lactulose; naturally present in whole grains, onions, garlic, asparagus, bananas |

| Probiotics | live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit. | directly introduce beneficial microbes to shape the gut environment |

Fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, miso, natto, kimchi, and some cheeses containing specific live microbes (e.g., Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum) |

| Postbiotics | preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer a health benefit. | deliver beneficial effects without living organisms, using inactivated microbial cells, components, or metabolites |

Heat-inactivated Bifidobacterium or Lactobacillus, bacterial lysates |

| Study | N | Phase | Population | Primary endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dizman et al. (2022) [169] |

30 | I | Nivolumab + ipili-mumab ± CBM588 (Clostridium butyricum) | Change in Bifidobacterium spp. Abundance at 12 weeks | No difference in Bifidobacte-rium spp. abundance. CBM588 arm had significantly improved PFS (12.7 vs 2.5 mo) and ORR (58% vs 20%). No increase in toxicity. |

| Ebrahimi et al. (2024) [170] |

30 | I | Cabozantinib + nivolumab ± CBM588 | Change in Bifidobacterium spp. Abundance at 13 weeks | No difference in Bifidobacte-rium spp. abundance. CBM588 arm had significant higher ORR (74% vs 20%, P=0.01). 6-mo PFS: 84% vs 60%. No increase in toxicity. |

| Derosa et al. (2025) [171] |

9 | I | Nivolumab + ipili-mumab + Onco-bax®-AK (Akkermansia massiliensis strain p2261, SGB9228) in patients lacking stool Akkermansia | ORR, pharmacodynamics, safety |

ORR 50% with evidence of immune and metabolic modulation. No increase in toxicity. |

6.3. Engineered Microorganisms

| Mechanisms | Examples |

|---|---|

| Presentation of tumor antigens and cancer vaccine carriers |

|

| Cytokine and chemokine release to enhance immune function |

|

7. Conclusions and Outlook

- Methodological rigor: implementation of absolute quantification, multi-omics integration, and standardized protocols for sample collection, processing and analysis

- Innovative trial designs: prospective studies that incorporate dietary profile, antibiotic exposure, and dynamic microbial signatures, with interval stool sampling and predefined microbiome-specific endpoint

- Refined interventions: development of optimized microbial consortia, inclusion of next-generation biotics, standardized reporting of biotic composition and FMT protocols, and rational FMT donor selection within a robust safety framework to enable scalability

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| 3-HAA | 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid |

| A2A | Adenosine A2A receptor |

| AHR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| CFU | Colony-forming units (e.g., CFU/g) |

| CMS | Consensus Molecular Subtypes (colon cancer) |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 |

| CXCL9 / CXCL10 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 / 10 |

| DC / DCs | Dendritic cell(s) |

| dMMR | Deficient mismatch repair |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| GPCR | G-protein–coupled receptor |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin (stain) |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| ICI / ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitor(s) |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-1 / IL-12 | Interleukin-1 / Interleukin-12 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| I3A | Indole-3-aldehyde |

| irAE(s) | Immune-related adverse event(s) |

| Kyn/Trp | Kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MDSC(s) | Myeloid-derived suppressor cell(s) |

| MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6 | Mismatch repair proteins/genes |

| MMR | Mismatch repair |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| MSI | Microsatellite instability |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite instability–high |

| NGP(s) | Next-generation probiotic(s) |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NK (cells) | Natural killer (cells) |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| NR | Not reached (survival endpoint) |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| POLE / POLD1 | DNA polymerase epsilon / delta 1 (genes) |

| qPCR | Quantitative PCR |

| RCC | Renal cell carcinoma |

| RNA-Seq | RNA sequencing (metatranscriptomics) |

| SCFA(s) | Short-chain fatty acid(s) |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TIL(s) | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte(s) |

| TLR(s) | Toll-like receptor(s) |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 |

References

- Pilard, C.; Ancion, M.; Delvenne, P.; Jerusalem, G.; Hubert, P.; Herfs, M. Cancer immunotherapy: it's time to better predict patients' response. Br J Cancer 2021, 125, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagni, F.; Guerini-Rocco, E.; Schultheis, A.M.; Grazia, G.; Rijavec, E.; Ghidini, M.; Lopez, G.; Venetis, K.; Croci, G.A.; Malapelle, U.; et al. Targeting Immune-Related Biological Processes in Solid Tumors: We do Need Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.C.; Shanahan, E.R.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V. Towards modulating the gut microbiota to enhance the efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023, 20, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, A.; Prasad, V. Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients With Cancer Who Are Eligible for and Respond to Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e192535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 2015, 14, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes-Ciriano, I.; Lee, S.; Park, W.Y.; Kim, T.M.; Park, P.J. A molecular portrait of microsatellite instability across multiple cancers. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; O'Haire, S.; Franchini, F.; M, I.J.; Zalcberg, J.; Macrae, F.; Canfell, K.; Steinberg, J. A scoping review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of pan-tumour biomarkers (dMMR, MSI, high TMB) in different solid tumours. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, M.; Amonkar, M.; Zhang, J.; Mehta, S.; Liaw, K.-L. Epidemiology of Microsatellite Instability High (MSI-H) and Deficient Mismatch Repair (dMMR) in Solid Tumors: A Structured Literature Review. Journal of Oncology 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.A.; Yarchoan, M.; Jaffee, E.; Swanton, C.; Quezada, S.A.; Stenzinger, A.; Peters, S. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: Utility for the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol 2019, 30, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandara, D.R.; Agarwal, N.; Gupta, S.; Klempner, S.J.; Andrews, M.C.; Mahipal, A.; Subbiah, V.; Eskander, R.N.; Carbone, D.P.; Riess, J.W.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and survival on immune checkpoint inhibition in >8000 patients across 24 cancer types. J Immunother Cancer 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.N.; Jin, Y.; He, M.M.; Liu, Z.X.; Xu, R.H. Evaluation of POLE and POLD1 Mutations as Biomarkers for Immunotherapy Outcomes Across Multiple Cancer Types. JAMA Oncol 2019, 5, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmezy, B.; Gheeya, J.; Lin, H.Y.; Huang, Y.; Kim, T.; Jiang, X.; Thein, K.Z.; Pilie, P.G.; Zeineddine, F.; Wang, W.; et al. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of POLE Mutations as Predictive Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Advanced Cancers. JCO Precis Oncol 2022, 6, e2100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presti, D.; Dall'Olio, F.G.; Besse, B.; Ribeiro, J.M.; Di Meglio, A.; Soldato, D. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) as a predictive biomarker of response to checkpoint blockers in solid tumors: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2022, 177, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheitasi, R.; Baumgart, S.; Roell, D.; Rose, N.; Watzl, C.; Dudziak, D.; Andreas, N.; Makarewicz, O.; Drube, S.; Schnizer, C.; et al. Age- and sex-associated differences in immune cell populations. iScience 2025, 28, 113092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagadala, M.; Sears, T.J.; Wu, V.H.; Perez-Guijarro, E.; Kim, H.; Castro, A.; Talwar, J.V.; Gonzalez-Colin, C.; Cao, S.; Schmiedel, B.J.; et al. Germline modifiers of the tumor immune microenvironment implicate drivers of cancer risk and immunotherapy response. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, B.; Duffy, D.; Urrutia, A.; Quach, H.; Patin, E.; Posseme, C.; Bergstedt, J.; Charbit, B.; Rouilly, V.; MacPherson, C.R.; et al. Distinctive roles of age, sex, and genetics in shaping transcriptional variation of human immune responses to microbial challenges. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E488–E497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangino, M.; Roederer, M.; Beddall, M.H.; Nestle, F.O.; Spector, T.D. Innate and adaptive immune traits are differentially affected by genetic and environmental factors. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 13850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, P.; Jojic, V.; Gao, T.; Bhattacharya, S.; Angel, C.J.; Furman, D.; Shen-Orr, S.; Dekker, C.L.; Swan, G.E.; Butte, A.J.; et al. Variation in the human immune system is largely driven by non-heritable influences. Cell 2015, 160, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzosa, E.A.; Huang, K.; Meadow, J.F.; Gevers, D.; Lemon, K.P.; Bohannan, B.J.; Huttenhower, C. Identifying personal microbiomes using metagenomic codes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, E2930–E2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Garmaeva, S.; Kurilshikov, A.; Vich Vila, A.; Gacesa, R.; Sinha, T.; Lifelines Cohort, S.; Segal, E.; Weersma, R.K.; et al. The long-term genetic stability and individual specificity of the human gut microbiome. Cell 2021, 184, 2302–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Skieceviciene, J.; Lehr, K.; Varkalaite, G.; Thon, C.; Urba, M.; Morkunas, E.; Kucinskas, L.; Bauraite, K.; Schanze, D.; et al. Gut microbial similarity in twins is driven by shared environment and aging. EBioMedicine 2022, 79, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Davenport, E.R.; Beaumont, M.; Jackson, M.A.; Knight, R.; Ober, C.; Spector, T.D.; Bell, J.T.; Clark, A.G.; Ley, R.E. Genetic Determinants of the Gut Microbiome in UK Twins. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, V.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Segata, N. Human microbiome acquisition and transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol 2025, 23, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.S.; Chang, E.B. The microbiome: Composition and locations. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2020, 176, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, W.; Schink, M.; Zopf, Y. Microbiota in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Med Sci (Basel) 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganusov, V.V.; De Boer, R.J. Do most lymphocytes in humans really reside in the gut? Trends Immunol 2007, 28, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhpazyan, N.K.; Mikhaleva, L.M.; Bedzhanyan, A.L.; Gioeva, Z.V.; Mikhalev, A.I.; Midiber, K.Y.; Pechnikova, V.V.; Biryukov, A.E. Exploring the Role of the Gut Microbiota in Modulating Colorectal Cancer Immunity. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Gazzaniga, F.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Sharpe, A.H. Microbiota-dependent regulation of costimulatory and coinhibitory pathways via innate immune sensors and implications for immunotherapy. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonio, C.M.; McHale, K.A.; Sherr, D.H.; Rubenstein, D.; Quintana, F.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: A rehabilitated target for therapeutic immune modulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziubanska-Kusibab, P.J.; Berger, H.; Battistini, F.; Bouwman, B.A.M.; Iftekhar, A.; Katainen, R.; Cajuso, T.; Crosetto, N.; Orozco, M.; Aaltonen, L.A.; et al. Colibactin DNA-damage signature indicates mutational impact in colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe-Herranz, M.; Rafail, S.; Beghi, S.; Gil-de-Gomez, L.; Verginadis, I.; Bittinger, K.; Pustylnikov, S.; Pierini, S.; Perales-Linares, R.; Blair, I.A.; et al. Gut microbiota modulate dendritic cell antigen presentation and radiotherapy-induced antitumor immune response. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Cross-reactivity between microbial and tumor antigens. Curr Opin Immunol 2022, 75, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluckiger, A.; Daillere, R.; Sassi, M.; Sixt, B.S.; Liu, P.; Loos, F.; Richard, C.; Rabu, C.; Alou, M.T.; Goubet, A.G.; et al. Cross-reactivity between tumor MHC class I-restricted antigens and an enterococcal bacteriophage. Science 2020, 369, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulos, C.M.; Wrzesinski, C.; Kaiser, A.; Hinrichs, C.S.; Chieppa, M.; Cassard, L.; Palmer, D.C.; Boni, A.; Muranski, P.; Yu, Z.; et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 2197–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, M.P.; Yonekura, S.; Duong, C.P.M.; Picard, M.; Ferrere, G.; Tidjani Alou, M.; Rauber, C.; Iebba, V.; Lehmann, C.H.K.; Amon, L.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced ileal crypt apoptosis and the ileal microbiome shape immunosurveillance and prognosis of proximal colon cancer. Nat Med 2020, 26, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, C.; Fredholm, S.; Willerslev-Olsen, A.; Hansen, M.; Bonefeld, C.M.; Geisler, C.; Andersen, M.H.; Odum, N.; Woetmann, A. Butyrate and propionate inhibit antigen-specific CD8(+) T cell activation by suppressing IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 14516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, M.; Riester, Z.; Baldrich, A.; Reichardt, N.; Yuille, S.; Busetti, A.; Klein, M.; Wempe, A.; Leister, H.; Raifer, H.; et al. Microbial short-chain fatty acids modulate CD8(+) T cell responses and improve adoptive immunotherapy for cancer. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.G.; Jannasch, A.H.; Cooper, B.; Patterson, J.; Kim, C.H. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol 2015, 8, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, L.F.; Burkhard, R.; Pett, N.; Cooke, N.C.A.; Brown, K.; Ramay, H.; Paik, S.; Stagg, J.; Groves, R.A.; Gallo, M.; et al. Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Science 2020, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.V.; Robeson, M.S., 2nd; Griffin, R.J.; Quick, C.M.; Siegel, E.R.; Cannon, M.J.; Vang, K.B.; Dings, R.P.M. Gastrointestinal Tract Dysbiosis Enhances Distal Tumor Progression through Suppression of Leukocyte Trafficking. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 5999–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremonesi, E.; Governa, V.; Garzon, J.F. G.; Mele, V.; Amicarella, F.; Muraro, M.G.; Trella, E.; Galati-Fournier, V.; Oertli, D.; Daster, S.R.; et al. Gut microbiota modulate T cell trafficking into human colorectal cancer. Gut 2018, 67, 1984–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, C.; Duan, Y.; Heinrich, B.; Rosato, U.; Diggs, L.P.; Ma, L.; Roy, S.; Fu, Q.; Brown, Z.J.; et al. Gut Microbiome Directs Hepatocytes to Recruit MDSCs and Promote Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 1248–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Gong, J.; Ge, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhao, J.; Saw, P.E.; et al. A high-fat diet promotes cancer progression by inducing gut microbiota-mediated leucine production and PMN-MDSC differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2306776121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bi, D.; Xie, R.; Li, M.; Guo, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Fang, J.; Ding, T.; Zhu, H.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum enhances the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesch, M.; Baty, F.; Albrich, W.C.; Flatz, L.; Rodriguez, R.; Rothschild, S.I.; Joerger, M.; Fruh, M.; Brutsche, M.H. Local tumor microbial signatures and response to checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1988403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano Nino, J.L.; Wu, H.; LaCourse, K.D.; Kempchinsky, A.G.; Baryiames, A.; Barber, B.; Futran, N.; Houlton, J.; Sather, C.; Sicinska, E.; et al. Effect of the intratumoral microbiota on spatial and cellular heterogeneity in cancer. Nature 2022, 611, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, V.; Lo Cascio, A.; Melacarne, A.; Tanaskovic, N.; Mozzarelli, A.M.; Tiraboschi, L.; Lizier, M.; Salvi, M.; Braga, D.; Algieri, F.; et al. Sensitizing cancer cells to immune checkpoint inhibitors by microbiota-mediated upregulation of HLA class I. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jin, H.; Xu, F.; Wang, X.; Xie, C.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolite Indole-3-Aldehyde Induces AhR and c-MYC Degradation to Promote Tumor Immunogenicity. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e09533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, R.; Vrbanac, A.; Taylor, B.C.; Aksenov, A.; Callewaert, C.; Debelius, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Kosciolek, T.; McCall, L.I.; McDonald, D.; et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Jin, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Current Sampling Methods for Gut Microbiota: A Call for More Precise Devices. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.; Reinke, S.N.; Ali, A.; Palmer, D.J.; Christophersen, C.T. Fecal sample collection methods and time of day impact microbiome composition and short chain fatty acid concentrations. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 13964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, M.R.; Jayawardana, T.; Koentgen, S.; Brooks, E.; Kennedy, N.; Berry, S.; Lees, C.; Hold, G.L. Optimised human stool sample collection for multi-omic microbiota analysis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 16816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, K.A.; Kazmi, N.; Barb, J.J.; Ames, N. The Oral and Gut Bacterial Microbiomes: Similarities, Differences, and Connections. Biol Res Nurs 2021, 23, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaan, A.M.; Brandt, B.W.; Buijs, M.J.; Crielaard, W.; Keijser, B.J.; Zaura, E. Comparability of microbiota of swabbed and spit saliva. Eur J Oral Sci 2022, 130, e12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Chen, F. The sampling strategy of oral microbiome. Imeta 2022, 1, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, W.B. The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas. With a report of ten original cases. 1893. 1991, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gye, W.E. The Ætiology of Malignant New Growths. The Lancet 1925, 206, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xia, H.; Tan, X.; Shi, C.; Ma, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhou, M.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; Jin, Y. Intratumoural microbiota: A new frontier in cancer development and therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Liang, H.; Han, Y. Intratumoral Microbiota Impacts the First-Line Treatment Efficacy and Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Free of Lung Infection. J Healthc Eng 2022, 2022, 5466853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Masuda, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Inoue, J.; Toyama, H.; Sakai, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Tsujimae, M.; Yamakawa, K.; et al. Impact of intratumoral microbiome on tumor immunity and prognosis in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2024, 59, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Su, H.; Johnson, C.H.; Khan, S.A.; Kluger, H.; Lu, L. Intratumour microbiome associated with the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and patient survival in cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2021, 151, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, S.; Huang, L.; Hu, Y.; He, X.; He, J.; Hu, B.; Xu, Y.; Rong, Y.; Yuan, C.; et al. Intratumoral microbiome: Implications for immune modulation and innovative therapeutic strategies in cancer. J Biomed Sci 2025, 32, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negron-Figueroa, D.; Colbert, L.E. Mechanisms by Which the Intratumoral Microbiome May Potentiate Immunotherapy Response. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 3350–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorens-Rico, V.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Goncalves, P.J.; Falony, G.; Raes, J. Benchmarking microbiome transformations favors experimental quantitative approaches to address compositionality and sampling depth biases. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloor, G.B.; Macklaim, J.M.; Pawlowsky-Glahn, V.; Egozcue, J.J. Microbiome Datasets Are Compositional: And This Is Not Optional. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contijoch, E.J.; Britton, G.J.; Yang, C.; Mogno, I.; Li, Z.; Ng, R.; Llewellyn, S.R.; Hira, S.; Johnson, C.; Rabinowitz, K.M.; et al. Gut microbiota density influences host physiology and is shaped by host and microbial factors. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, H.J.; Pouwels, S.D.; Funke, A.; Bos, N.A.; Dijkstra, G. Crohn's disease patients have more IgG-binding fecal bacteria than controls. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012, 19, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Weber, M.; Paul, L.S.; Grumpel-Schluter, A.; Kluess, J.; Neuhaus, K.; Fuchs, T.M. Absolute abundance calculation enhances the significance of microbiome data in antibiotic treatment studies. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1481197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Howe, S.; Deng, F.; Zhao, J. Current Applications of Absolute Bacterial Quantification in Microbiome Studies and Decision-Making Regarding Different Biological Questions. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.; Helb, D.; Burday, M.; Connell, N.; Alland, D. A detailed analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene segments for the diagnosis of pathogenic bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 2007, 69, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, J.M.; Abbott, S.L. 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: Pluses, perils, and pitfalls. J Clin Microbiol 2007, 45, 2761–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matchado, M.S.; Ruhlemann, M.; Reitmeier, S.; Kacprowski, T.; Frost, F.; Haller, D.; Baumbach, J.; List, M. On the limits of 16S rRNA gene-based metagenome prediction and functional profiling. Microb Genom 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buetas, E.; Jordan-Lopez, M.; Lopez-Roldan, A.; D'Auria, G.; Martinez-Priego, L.; De Marco, G.; Carda-Dieguez, M.; Mira, A. Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing by PacBio improves taxonomic resolution in human microbiome samples. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y.; Komiya, S.; Yasumizu, Y.; Yasuoka, Y.; Mizushima, K.; Takagi, T.; Kryukov, K.; Fukuda, A.; Morimoto, Y.; Naito, Y.; et al. Full-length 16S rRNA gene amplicon analysis of human gut microbiota using MinION nanopore sequencing confers species-level resolution. BMC Microbiol 2021, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, M.; Ward, D.V.; Pasolli, E.; Tolio, T.; Zolfo, M.; Asnicar, F.; Truong, D.T.; Tett, A.; Morrow, A.L.; Segata, N. Strain-level microbial epidemiology and population genomics from shotgun metagenomics. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubucker, S.; Segata, N.; Goll, J.; Schubert, A.M.; Izard, J.; Cantarel, B.L.; Rodriguez-Mueller, B.; Zucker, J.; Thiagarajan, M.; Henrissat, B.; et al. Metabolic reconstruction for metagenomic data and its application to the human microbiome. PLoS Comput Biol 2012, 8, e1002358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamames, J.; Cobo-Simon, M.; Puente-Sanchez, F. Assessing the performance of different approaches for functional and taxonomic annotation of metagenomes. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Kankuri, E.; Kankainen, M. Understanding human health through metatranscriptomics. Trends Mol Med 2023, 29, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Hakkinen, A.E.; Kankuri, E.; Kankainen, M. Current concepts, advances, and challenges in deciphering the human microbiota with metatranscriptomics. Trends Genet 2023, 39, 686–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, S.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, B.; Zhao, J. Culturomics: A critical approach in studying the roles of human and animal microbiota. Animal Nutriomics 2024, 1, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.S.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Roh, S.W.; Whon, T.W. Advances in Culturomics Research on the Human Gut Microbiome: Optimizing Medium Composition and Culture Techniques for Enhanced Microbial Discovery. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 34, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, K.; Mbaye, B.; Nili, S.; Filin, A.; Benlaifaoui, M.; Malo, J.; Renaud, A.S.; Belkaid, W.; Hunter, S.; Messaoudene, M.; et al. Coupling culturomics and metagenomics sequencing to characterize the gut microbiome of patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Gut Pathog 2025, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstokstraeten, R.; Mackens, S.; Callewaert, E.; Blotwijk, S.; Emmerechts, K.; Crombe, F.; Soetens, O.; Wybo, I.; Vandoorslaer, K.; Mostert, L.; et al. Culturomics to Investigate the Endometrial Microbiome: Proof-of-Concept. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Bao, Z.X.; Zhao, P.J.; Li, G.H. Advances in the Study of Metabolomics and Metabolites in Some Species Interactions. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Castellví, F.; Pacheco-Tapia, R.; Deslande, M.; Jia, M.; Andrikopoulos, P.; Chechi, K.; Bonnefond, A.; Froguel, P.; Dumas, M.-E. Advances in the integration of metabolomics and metagenomics for human gut microbiome and their clinical applications. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 167, 117248. [CrossRef]

- Creek, D.; Dunn, W.; Griffin, J.; Hall, R.; Lei, Z.; Mistrik, R.; Neumann, S.; Schymanski, E.; Sumner, L.; Trengove, R.; et al. Metabolite identification: Are you sure? And how do your peers gauge your confidence? Metabolomics 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, I.; Wei, B.; Veillon, L.; Tan, L.; Martinez, S.; Tran, B.; Raskind, A.; de Jong, F.; Liu, Y.; Ding, J.; et al. Ion suppression correction and normalization for non-targeted metabolomics. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakozaki, T.; Richard, C.; Elkrief, A.; Hosomi, Y.; Benlaifaoui, M.; Mimpen, I.; Terrisse, S.; Derosa, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Routy, B.; et al. The Gut Microbiome Associates with Immune Checkpoint Inhibition Outcomes in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2020, 8, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xie, M.; Lau, H.C.; Zeng, R.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Jiang, L.; et al. Effects of gut microbiota on immune checkpoint inhibitors in multi-cancer and as microbial biomarkers for predicting therapeutic response. Med 2025, 6, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgia, N.J.; Bergerot, P.G.; Maia, M.C.; Dizman, N.; Hsu, J.; Gillece, J.D.; Folkerts, M.; Reining, L.; Trent, J.; Highlander, S.K.; et al. Stool Microbiome Profiling of Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Anti-PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Eur Urol 2020, 78, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullern, A.; Holm, K.; Rossevold, A.H.; Andresen, N.K.; Bang, C.; Lingjaerde, O.C.; Naume, B.; Hov, J.R.; Kyte, J.A. Gut microbiota diversity is prognostic and associated with benefit from chemo-immunotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Oncol 2025, 19, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.G.; Koh, J.Y.; Shin, S.J.; Shin, J.H.; Hong, M.; Chung, H.C.; Rha, S.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Prior antibiotic administration disrupts anti-PD-1 responses in advanced gastric cancer by altering the gut microbiome and systemic immune response. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Collado, M.C.; Ben-Amor, K.; Salminen, S.; de Vos, W.M. The Mucin degrader Akkermansia muciniphila is an abundant resident of the human intestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 1646–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, W.; Chen, F.; Mo, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z. Landscape of tumoral ecosystem for enhanced anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by gut Akkermansia muciniphila. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 114306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P. M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillere, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluomini, L.; Bonato, A.; Almonte, A.; Gattazzo, F.; Lebhar, I.; Birebent, R.; Flament, C.; Xiberras, M.; Marques, M.; Ly, P.; et al. 1172O Akkermansia muciniphila-based multi-omic profiling in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35, S762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenda, A.; Iwan, E.; Kuznar-Kaminska, B.; Bomba, A.; Bielinska, K.; Krawczyk, P.; Chmielewska, I.; Frak, M.; Szczyrek, M.; Rolska-Kopinska, A.; et al. Gut microbial predictors of first-line immunotherapy efficacy in advanced NSCLC patients. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; Mazieres, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Goldwasser, F.; et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med 2022, 28, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, S.; Martin, R.; Rossi, O.; Bermudez-Humaran, L.G.; Chatel, J.M.; Sokol, H.; Thomas, M.; Wells, J.M.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and human intestinal health. Curr Opin Microbiol 2013, 16, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Halder, C.V.; Faria, A.V.S.; Andrade, S.S. Action and function of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2017, 31, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Ren, H.; Shen, Y.; Bi, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Alter between gut bacteria and blood metabolites and the anti-tumor effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in breast cancer. BMC Microbiol 2020, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de, M.u.i.n.c.k. E. J.; Trosvik, P.; Nguyen, N.; Fashing, P.J.; Stigum, V.M.; Robinson, N.; Hermansen, J.U.; Munthe-Kaas, M.C.; Baumbusch, L.O. Reduced abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the gut microbiota of children diagnosed with cancer, a pilot study. Frontiers in Microbiomes 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredon, M.; Danne, C.; Pham, H.P.; Ruffie, P.; Bessede, A.; Rolhion, N.; Creusot, L.; Brot, L.; Alonso, I.; Langella, P.; et al. Faecalibaterium prausnitzii strain EXL01 boosts efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13, 2374954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olekhnovich, E.I.; Ivanov, A.B.; Babkina, A.A.; Sokolov, A.A.; Ulyantsev, V.I.; Fedorov, D.E.; Ilina, E.N. Consistent Stool Metagenomic Biomarkers Associated with the Response To Melanoma Immunotherapy. mSystems 2023, 8, e0102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredon, M.; le Malicot, K.; Louvet, C.; Evesque, L.; Gonzalez, D.; Tougeron, D.; Sokol, H. Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii Is Associated With Clinical Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Patients With Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma: Results of Microbiota Analysis of PRODIGE 59-FFCD 1707-DURIGAST Trial. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W.; Li, M. Population-level variation in gut bifidobacterial composition and association with geography, age, ethnicity, and staple food. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillere, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funayama, E.; Hosonuma, M.; Tajima, K.; Isobe, J.; Baba, Y.; Murayama, M.; Narikawa, Y.; Toyoda, H.; Tsurui, T.; Maruyama, Y.; et al. Oral administration of Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium infantis ameliorates cefcapene pivoxil-induced attenuation of anti-programmed cell death protein-1 antibody action in mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 182, 117749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microbial Inosine Promotes Immune-Checkpoint Blockade Response in Mice. Cancer Discovery 2020, 10, 1439. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Han, J.; Wang, L.; Fan, Z.; Feng, L.; Zuo, J.; Wang, Y. Bifidobacterium breve predicts the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in Chinese NSCLC patients. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 6325–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, V.; De Filippis, F.; Marotta, R.; Pasolli, E.; Ercolini, D. Genomic features and prevalence of Ruminococcus species in humans are associated with age, lifestyle, and disease. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 115018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Luccia, B.; Molgora, M.; Khantakova, D.; Jaeger, N.; Chang, H.W.; Czepielewski, R.S.; Helmink, B.A.; Onufer, E.J.; Fachi, J.L.; Bhattarai, B.; et al. TREM2 deficiency reprograms intestinal macrophages and microbiota to enhance anti-PD-1 tumor immunotherapy. Sci Immunol 2024, 9, eadi5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H. Control of lymphocyte functions by gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, M.; Nagatomo, R.; Doi, K.; Shimizu, J.; Baba, K.; Saito, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Inoue, K.; Muto, M. Association of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut Microbiome With Clinical Response to Treatment With Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab in Patients With Solid Cancer Tumors. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e202895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botticelli, A.; Vernocchi, P.; Marini, F.; Quagliariello, A.; Cerbelli, B.; Reddel, S.; Del Chierico, F.; Di Pietro, F.; Giusti, R.; Tomassini, A.; et al. Gut metabolomics profiling of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients under immunotherapy treatment. J Transl Med 2020, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, R.; Meng, M.; Roviello, G.; Oh, B.; Feng, L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Gut microbiota and metabolites associated with immunotherapy efficacy in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A pilot study. J Thorac Dis 2024, 16, 6936–6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, A.M.; García, M.Z.; Gomez, A.G.; Martí-Pi, M.; Ruiz, M.G.; Goñi, A.S.; RomeroMonleon, A.; Osorio, K.A.; Velasco, M.A.; Per, S.E.; et al. 352P: Biomarkers of immunotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer: Microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2025, 20, S210–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratiel-Pellitero, A.; Zapata-Garcia, M.; Gascon-Ruiz, M.; Sesma, A.; Quilez, E.; Ramirez-Labrada, A.; Martinez-Lostao, L.; Domingo, M.P.; Esteban, P.; Yubero, A.; et al. Biomarkers of Immunotherapy Response in Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Microbiota Composition, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, and Intestinal Permeability. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutzac, C.; Jouniaux, J.M.; Paci, A.; Schmidt, J.; Mallardo, D.; Seck, A.; Asvatourian, V.; Cassard, L.; Saulnier, P.; Lacroix, L.; et al. Systemic short chain fatty acids limit antitumor effect of CTLA-4 blockade in hosts with cancer. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, S.; Torres, A.G.; Ribas de Pouplana, L. Inosine in Biology and Disease. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, L.; Yu, L.; Li, Q.; Tian, X.; He, J.; Zeng, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y.; et al. Inhibition of UBA6 by inosine augments tumour immunogenicity and responses. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.K.; Kwon, B. Immune regulation through tryptophan metabolism. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.J.; McPherson, A.C.; Phelps, C.M.; Pandey, S.P.; Laughlin, C.R.; Shapira, J.H.; Medina Sanchez, L.; Rana, M.; Richie, T.G.; Mims, T.S.; et al. Dietary tryptophan metabolite released by intratumoral Lactobacillus reuteri facilitates immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. Cell 2023, 186, 1846–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticelli, A.; Mezi, S.; Pomati, G.; Cerbelli, B.; Cerbelli, E.; Roberto, M.; Giusti, R.; Cortellini, A.; Lionetto, L.; Scagnoli, S.; et al. Tryptophan Catabolism as Immune Mechanism of Primary Resistance to Anti-PD-1. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayama, M.; Masuda, J.; Mori, K.; Yasui, H.; Hozumi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Furuhashi, K.; Fujisawa, T.; Enomoto, N.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. Comprehensive assessment of multiple tryptophan metabolites as potential biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 2021, 23, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Stine, J.G.; Bisanz, J.E.; Okafor, C.D.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: Metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Bajaj, J.S. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014, 30, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanasi, S.K.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Johnson, M.A.; Miller, C.M.; Ganguly, S.; Lande, K.; LaPorta, M.A.; Hoffmann, F.A.; Mann, T.H.; et al. Bile acid synthesis impedes tumor-specific T cell responses during liver cancer. Science 2025, 387, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.C.; Wu, C.J.; Hung, Y.W.; Lee, C.J.; Chi, C.T.; Lee, I.C.; Yu-Lun, K.; Chou, S.H.; Luo, J.C.; Hou, M.C.; et al. Gut microbiota and metabolites associate with outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macandog, A.D. G.; Catozzi, C.; Capone, M.; Nabinejad, A.; Nanaware, P.P.; Liu, S.; Vinjamuri, S.; Stunnenberg, J.A.; Galie, S.; Jodice, M.G.; et al. Longitudinal analysis of the gut microbiota during anti-PD-1 therapy reveals stable microbial features of response in melanoma patients. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 2004–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, M.; Shaikh, F.; White, J.; Morais, E.; Forde, P.; Brahmer, J.R.; Tangney, M.; Sears, C.; Naidoo, J. 1255 Longitudinal assessment of the gut microbiome and its association with treatment response in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2024, 12, A1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Shi, Q.; Liu, X.; Tang, H.; Lu, B.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Dynamic gut microbiota changes in patients with advanced malignancies experiencing secondary resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune-related adverse events. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1144534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjork, J.R.; Bolte, L.A.; Maltez Thomas, A.; Lee, K.A.; Rossi, N.; Wind, T.T.; Smit, L.M.; Armanini, F.; Asnicar, F.; Blanco-Miguez, A.; et al. Longitudinal gut microbiome changes in immune checkpoint blockade-treated advanced melanoma. Nat Med 2024, 30, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Iebba, V.; Silva, C.A. C.; Piccinno, G.; Wu, G.; Lordello, L.; Routy, B.; Zhao, N.; Thelemaque, C.; Birebent, R.; et al. Custom scoring based on ecological topology of gut microbiota associated with cancer immunotherapy outcome. Cell 2024, 187, 3373–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelands, J.; Kuppen, P.J. K.; Ahmed, E.I.; Mall, R.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, P.; Monaco, G.; Raynaud, C.; de Miranda, N.; Ferraro, L.; et al. An integrated tumor, immune and microbiome atlas of colon cancer. Nat Med 2023, 29, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A.K.; McCulloch, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Chauvin, J.M.; Morrison, R.M.; Deblasio, R.N.; Menna, C.; Ding, Q.; Pagliano, O.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Lenehan, J.G.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Jamal, R.; Messaoudene, M.; Daisley, B.A.; Hes, C.; Al, K.F.; Martinez-Gili, L.; Puncochar, M.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: A phase I trial. Nat Med 2023, 29, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, D.K.; Baines, K.J.; Jabbarizadeh, B.; Miller, W.H.; Jamal, R.; Ernst, S.; Logan, D.; Belanger, K.; Esfahani, K.; Elkrief, A.; et al. Improved survival in advanced melanoma patients treated with fecal microbiota transplantation using healthy donor stool in combination with anti-PD1: Final results of the MIMic phase 1 trial. J Immunother Cancer 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Cho, B.; Kim, S.Y.; Do, E.J.; Bae, D.J.; Kim, S.; Kweon, M.N.; Song, J.S.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves anti-PD-1 inhibitor efficacy in unresectable or metastatic solid cancers refractory to anti-PD-1 inhibitor. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1380–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y.; Chen, Y. Updated outcomes and exploratory analysis of RENMIN-215: Tislelizumab plus fruquintinib and fecal microbiota transplantation in refractory microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2024, 14, 5351–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lei, J.; Ke, S.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y.; Alnaggar, M.; Qiu, H.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus tislelizumab and fruquintinib in refractory microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal cancer: An open-label, single-arm, phase II trial (RENMIN-215). EClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttagupta, S.; Messaoudene, M.; Jamal, R.; Mihalcioiu, C.; Marcoux, N.; Hunter, S.; Piccinno, G.; Puncochár, M.; Bélanger, K.; Tehfe, M.; et al. Abstract 2210: Microbiome profiling reveals that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) modulates response and toxicity when combined with immunotherapy in patients with lung cancer and melanoma (FMT-LUMINate NCT04951583). Cancer Research 2025, 85, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, C.; Porcari, S.; Buti, S.; Fornarini, G.; Primi, F.; Giudice, G.C.; Damassi, A.; Giron Berrios, J.R.; Stumbo, L.; Arduini, D.; et al. LBA77 Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) versus placebo in patients receiving pembrolizumab plus axitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Preliminary results of the randomized phase II TACITO trial. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35, S1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlesny, D.; Durdevic, M.; Paramsothy, S.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Hogenauer, C.; Gorkiewicz, G.; Walter, J.; Fricke, W.F. Identification of clinical and ecological determinants of strain engraftment after fecal microbiota transplantation using metagenomics. Cell Rep Med 2022, 3, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianiro, G.; Puncochar, M.; Karcher, N.; Porcari, S.; Armanini, F.; Asnicar, F.; Beghini, F.; Blanco-Miguez, A.; Cumbo, F.; Manghi, P.; et al. Variability of strain engraftment and predictability of microbiome composition after fecal microbiota transplantation across different diseases. Nat Med 2022, 28, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarriz, S.; Szamosi, J.C.; Whelan, F.J.; Lau, J.T.; Libertucci, J.; Rossi, L.; Fontes, M.E.; Wolfe, M.; Lee, C.H.; Moayyedi, P.; et al. Detecting microbial engraftment after FMT using placebo sequencing and culture enriched metagenomics to sort signals from noise. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xiong, Q.; Li, L.; Hu, Y. Intestinal microbiota predicts lung cancer patients at risk of immune-related diarrhea. Immunotherapy 2019, 11, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Wang, D.; Long, J.; Yang, X.; Lin, J.; Song, Y.; Xie, F.; Xun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Gut microbiome is associated with the clinical response to anti-PD-1 based immunotherapy in hepatobiliary cancers. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiuddin, J.J.; Chu, B.; Facciabene, A.; Poirier, K.; Wang, X.; Doucette, A.; Zheng, C.; Xu, W.; Anstadt, E.J.; Amaravadi, R.K.; et al. Association of Antibiotic Exposure With Survival and Toxicity in Patients With Melanoma Receiving Immunotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021, 113, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Sbeih, H.; Herrera, L.N.; Tang, T.; Altan, M.; Chaftari, A.M.; Okhuysen, P.C.; Jenq, R.R.; Wang, Y. Correction to: Impact of antibiotic therapy on the development and response to treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor-mediated diarrhea and colitis. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, N.; Lepage, P.; Coutzac, C.; Soularue, E.; Le Roux, K.; Monot, C.; Boselli, L.; Routier, E.; Cassard, L.; Collins, M.; et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol 2019, 30, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usyk, M.; Pandey, A.; Hayes, R.B.; Moran, U.; Pavlick, A.; Osman, I.; Weber, J.S.; Ahn, J. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei predict immune-related adverse events in immune checkpoint blockade treatment of metastatic melanoma. Genome Med 2021, 13, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Lin, X.; Sun, T.; Shao, X.; Huang, X.; Du, W.; Guo, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, T.; et al. Gut microbiome for predicting immune checkpoint blockade-associated adverse events. Genome Med 2024, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijden, R.J.; van Eijs, M.J.M.; Paganelli, F.L.; Viveen, M.C.; Rogers, M.R.C.; Top, J.; May, A.M.; van de Wijgert, J.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; consortium, U. Gut microbiome and immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicity. Eur J Cancer 2025, 216, 115221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, P.; Sun, D.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, X.L.; Han, T.; Yu, J.; Sheng, C.; Chen, H.; Hong, J.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Abrogates Intestinal Toxicity and Promotes Tumor Immunity to Increase the Efficacy of Dual CTLA4 and PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Res 2023, 83, 3710–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Luo, L.; Liang, W.; Yin, Q.; Guo, J.; Rush, A.M.; Lv, Z.; Liang, Q.; Fischbach, M.A.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; et al. Bifidobacterium alters the gut microbiota and modulates the functional metabolism of T regulatory cells in the context of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 27509–27515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Waters, N.R.; Smith, N.; Dai, A.; Slingerland, J.; Aleynick, N.; Febles, B.; Gogia, P.; Socci, N.D.; Lumish, M.; et al. Immune-Related Colitis Is Associated with Fecal Microbial Dysbiosis and Can Be Mitigated by Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Cancer Immunol Res 2024, 12, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wiesnoski, D.H.; Helmink, B.A.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Choi, K.; DuPont, H.L.; Jiang, Z.D.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Sanchez, C.A.; Chang, C.C.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1804–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Varatharajalu, K.; Shatila, M.; Cruz, C.C.; Thomas, A.; DuPont, H. S300 First-Line Treatment of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Immune-Mediated Colitis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG 2024, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fakhrany, O.M.; Elekhnawy, E. Next-generation probiotics: The upcoming biotherapeutics. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 51, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelela, M.E.; Helmy, Y.A. Next-Generation Probiotics as Novel Therapeutics for Improving Human Health: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizman, N.; Meza, L.; Bergerot, P.; Alcantara, M.; Dorff, T.; Lyou, Y.; Frankel, P.; Cui, Y.; Mira, V.; Llamas, M.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomized phase 1 trial. Nat Med 2022, 28, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Dizman, N.; Meza, L.; Malhotra, J.; Li, X.; Dorff, T.; Frankel, P.; Llamas-Quitiquit, M.; Hsu, J.; Zengin, Z.B.; et al. Cabozantinib and nivolumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomized phase 1 trial. Nat Med 2024, 30, 2576–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Barthelemy, P.; Laguerre, B.; Barlesi, F.; Escudier, B.; Zitvogel, L.; Albiges, L. Phase 1 results of Oncobax-AK in combination with ipilimumab/nivolumab in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC.; NCT05865730). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2025, 43, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Zhou, K.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Gut microbiota shapes cancer immunotherapy responses. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, G.J.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Lisberg, A.E.; Farber, C.M.; Morganstein, N.; Sanborn, R.E.; Halmos, B.; Spira, A.I.; Pathak, R.; Huang, C.H.; et al. A phase 2 study of an off-the-shelf, multi-neoantigen vector (ADXS-503) in patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer either progressing on prior pembrolizumab or in the first-line setting. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40, 9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, W.; Wick, A.; Chinot, O.; Sahm, F.; von Deimling, A.; Jungk, C.; Mansour, M.; Podola, L.; Lubenau, H.; Platten, M. KS05.6.A Oral DNA vaccination targeting VEGFR2 combined with the anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab in patients with progressive glioblastoma - final results. NCT03750071. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 24, ii6–ii6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, J.J.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Medina, T.; Verschraegen, C.F.; Varterasian, M.; Brennan, A.M.; Riese, R.J.; Sokolovska, A.; Strauss, J.; Hava, D.L.; et al. Phase I Study of SYNB1891, an Engineered E. coli Nissle Strain Expressing STING Agonist, with and without Atezolizumab in Advanced Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Chong, A.; Hong, Y.; Min, J.J. Bioengineering of bacteria for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hu, L.; Yang, K. Engineered bacteria in tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Lett 2024, 589, 216817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).