1. Introduction

Food systems are major contributors to environmental degradation and public-health burdens (EAT Lancet, 2025; IPCC, 2023). Recent estimates attribute roughly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions to the food system, alongside substantial land-use change, biodiversity loss, and water stress (Dunne, 2020; IPCC, 2022; Crippa et al., 2021; Poore & Nemecek, 2018). In response, alternative proteins—including plant-based, fermented, cultivated, and insect-based options—are advanced as lower-impact substitutes for conventional meat (Fischer et al., 2023; GFI Europe, 2024; Malila et al., 2024; Springmann et al., 2018; Willett et al., 2019). Yet, despite rapid supply-side innovation and growing availability, consumer adoption in Western markets such as Germany remains limited (Amoneit et al., 2025; GFI Europe, 2024; Malila et al., 2024; Weinrich et al., 2020). Prior work suggests that hesitancy often reflects how such products are positioned and communicated, rather than their intrinsic properties (Tso et al., 2021; Michel et al., 2021).

A sizeable literature shows that disgust, unfamiliarity and scepticism are salient affective barriers, especially for insect-based and other novel proteins (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2016; Malila et al., 2024; Onwezen et al., 2021; Rozin & Fallon, 1987; Verbeke, 2015). Messaging that relies predominantly on rational appeals (e.g., environmental impact, nutrition) often fails to engage the emotional and cultural dimensions of everyday food choice (Drulytė et al., 2022; Michel et al., 2021; Siddiqui et al., 2022). In the German context, this may reflect a misalignment between innovation-centred frames and consumers’ value orientations.

Guided by Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values (2012), we focus on Tradition and Security, which prior research identifies as salient in German food behaviour, emphasising familiarity, routine, predictability, and reassurance (Hempel & Roosen, 2024; Koch et al., 2021). To assess how values-centric messages may operate across the persuasion process, we adopt McGuire’s communication–persuasion model (Attention, Comprehension, Acceptance, Retention, Action) as an analytic scaffold (Arnold et al., 2022; McGuire, 1985). Integrating these frameworks enables a theoretically grounded account of what messages must achieve (values activation) and when in the communication sequence they matter.

This study makes three contributions. First, based on a desk-based synthesis of recent literature, we articulate five communication requirements that translate Tradition and Security into designable goals: Cultural familiarity, Emotional safety, Simplicity and clarity, Trust and credibility, and Routine integration. Second, we operationalise these requirements into actionable values-centric communication guidelines and short on-pack claims, bridging theory and execution. Third, we provide exploratory evidence from a focus group with German students comparing reactions to an original versus a refined, values-centric packaging prototype for an insect-based snack—a stringent test case given cultural unfamiliarity and high aversion potential (Naranjo-Guevara et al., 2023; Onwezen et al., 2021).

The study is guided by the following research question: How can values-centric communication guidelines for companies offering protein alternatives in Germany better align messaging with consumer values? We implement a sequential design: (i) identify dominant values and derive communication requirements via desk synthesis; (ii) translate requirements into guidelines and claims; and (iii) examine consumer responses using McGuire’s stages in an exploratory focus group. Our focus on Germany responds to evidence that Tradition and Security frequently shape situational and identity-related food decisions (Hempel & Roosen, 2024; Koch et al., 2021), suggesting that values-centric communication may be pivotal for acceptance.

By combining values theory with a stage-based persuasion framework, the paper offers a coherent, testable approach to designing values-centric communication for alternative proteins. The proposed requirements and guidelines are intended as hypotheses for validation in larger, controlled studies, while also providing immediate structure for practitioners seeking to align packaging and messaging with culturally embedded consumer values in the German market.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed an exploratory qualitative design to examine how values-centric communication can shape consumer perceptions of alternative proteins in Germany. A qualitative approach was selected because values, emotions, and cultural associations related to food are complex, subjective phenomena that cannot be adequately captured through quantitative measures alone. The overarching research question guiding this study was:

How can values-centric communication guidelines for companies offering protein alternatives in Germany better align messaging with consumer values?

A sequential design was implemented in four phases. First, consumer values relevant to eating behaviour in Germany were identified through a structured desk review. Second, these values were translated into communication guidelines. Third, guidelines were operationalised into concrete packaging claims. Finally, consumer responses to these claims were explored in a focus group.

2.1. Secondary Data Analysis

2.1.1. Identification of Consumer Values

To establish the value foundations, we conducted a structured search in PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar using Boolean operators: “consumer values” AND “eating behaviour” AND “Germany” AND (“alternative proteins” OR “novel foods”). The search yielded 185 records. After title/abstract screening, 73 full texts were reviewed. We included sources published 2021–2025 (peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, industry reports) that (i) investigated food-related consumer behaviour, (ii) reported German samples or German-specific results within broader European studies, and (iii) explicitly analysed personal values (e.g., Tradition, Security, reassurance). We excluded work prior to 2021, studies centred solely on technological development without consumer data, and papers that discussed attitudes or beliefs without a values construct. Applying these criteria, 4 studies were retained for the synthesis.

To triangulate and assess transferability to our context, we also drew on unpublished, practice-based evidence from exploratory focus groups conducted by the Fontys Research Group (Floto-Stammen, 2023–2025; N≈200 participants across students, educators, and company representatives). These internal data were analysed qualitatively and used as supporting, non-review evidence; they did not enter the formal study count.

The analysis was guided by Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values (2012), which provided the conceptual framework for coding and interpretation. A thematic synthesis identified recurring value drivers and mapped them onto Schwartz’s categories. To enhance validity, both academic and industry sources were included, and the findings were triangulated with insights from the Fontys focus groups (Floto-Stammen, 2023–2025), which had similarly revealed Tradition and Security as dominant influences in food choices.

2.2.2. Development of Communication Guidelines

Insights from this review were complemented by Schmeltz’s (2014) conceptual work on value-based communication. While not a formal methodology, Schmeltz provides a theoretical foundation for understanding how consumer values can be reflected in messaging. Based on this perspective and the thematic synthesis of the reviewed literature, five provisional communication requirements were derived: cultural familiarity, emotional safety, simplicity and clarity, trust and credibility, and routine integration. These categories served as the conceptual basis for the communication guidelines.

2.2.3. Formulation of Packaging Claims

The guidelines were then operationalised into concrete packaging claims by synthesising findings from peer-reviewed studies on consumer behaviour, packaging communication, and responses to food innovations published between 2020 and 2025. Five operational rules were established to ensure consistency: culturally familiar language, emotionally reassuring tone, emphasis on simplicity, inclusion of trust-building cues, and alignment with consumer identity.

Insect-based protein was chosen as the test case due to its cultural unfamiliarity and high resistance in Western contexts (Onwezen et al., 2021). Claims were applied to the neutral baseline packaging of Catch Your Bug (2025), a minimally designed snack brand.

Packaging stimuli were generated using AI tools. ChatGPT was employed for text refinement, and DALL·E for visual editing. Prompts specified that the refined packaging should replicate the baseline in layout, colour palette, and typography, with the only changes being the textual claims and imagery substitution (insects replaced with “crispy bites”). Drafts were iteratively refined until both versions matched in visual balance and quality (see

Figure 1).

2.2. Exploratory Focus Group

Primary data were collected through a single exploratory focus group with seven participants. Focus groups are well suited to exploring emotional and cognitive responses to novel stimuli (Krueger & Casey, 2015). Purposive sampling was used to recruit German residents aged 19–21 who consumed animal-based products but had no prior experience with insect-based foods. This age group was targeted because young consumers are often more open to food innovations (Barska, 2014). Fluency in English was required to eliminate potential translation effects.

Participants were recruited via a university mailing list and screened through an online questionnaire to confirm eligibility. The final sample comprised four female and three male undergraduate students. Each participant received a €15 voucher as compensation. A single focus group was deemed appropriate given the exploratory aim of the study, which prioritised depth of insight over representativeness.

2.2.1. Stimulus Preparation, Procedure, and Analysis

Two packaging versions were presented: a neutral baseline and a refined version featuring values-based claims and culturally familiar imagery (see Fig. 1). Both were digitally designed to minimise confounding variables, ensuring that verbal communication constituted the primary manipulated element.

The 60-minute session took place in a neutral classroom setting and followed a semi-structured topic guide based on McGuire’s Communication–Persuasion Matrix (Attention, Comprehension, Acceptance, Retention, Action), which structured questions about both packaging versions. Participants first viewed the original packaging, followed by the refined version after a short break.

Discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using qualitative content analysis. Coding followed McGuire’s stages deductively and was further categorised by emotional tone. The initial coding was conducted in Excel by the lead researcher. To enhance reliability, a 20% subset of the transcript was independently coded by a second researcher, yielding an inter-coder agreement of 87%. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and an audit trail of coding decisions was maintained to ensure transparency.

2.2.2. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Confidentiality was assured, and participants were anonymised in transcripts.

This study is exploratory and subject to several constraints. Reliance on secondary data in earlier phases limits originality and may import biases from prior research. The focus group was small and demographically narrow, providing rich but non-generalisable insights. Stimulus materials created with AI may contain stylistic artefacts beyond the intended manipulations. Despite inter-coder checks, coding was conducted primarily by one researcher, which may have introduced subjectivity. Nevertheless, the sequential design offers a coherent framework for linking consumer values to communication strategies and provides preliminary insights into how value-based messaging may influence perceptions of alternative proteins.

3. Results

This study followed a sequential design, progressing from a synthesis of existing evidence to exploratory testing of values-centric claims in a focus group. The results reported here concern the desk-based synthesis, the derivation of communication requirements and guidelines, their application to packaging claims, and the exploratory consumer responses.

3.1. Core Consumer Values

A thematic synthesis of four studies (

Table 1) identified Tradition and Security as the two most consistent values shaping food-related behaviour in Germany. These values were observed across flexitarians, health-oriented consumers, and omnivores. While Sustainability and Health were frequently discussed, they tended to be secondary to the cultural and emotional anchors of Tradition and Security.

In Schwartz’s framework, Tradition denotes respect for inherited practices and social norms. In the German context, this value is apparent in eating routines established through family and cultural habitus. Nationally representative evidence indicates the continued centrality of meat to the notion of a “proper meal,” with a high share of regular meat consumption (Koch et al., 2021). Qualitative work similarly emphasises continuity—participants described their eating patterns as “how I grew up eating,” even among those motivated to reduce meat for sustainability reasons (Hajdari, 2023).

Security, defined as predictability and reassurance, also emerged as a decisive driver. During recent inflationary periods, consumers gravitated toward staple foods not only for affordability but also for their symbolic stability (Hempel & Roosen, 2024). Reluctance to try novel proteins—owing to uncertainty about preparation, taste, and nutrition—was frequently reported (Seffen & Dohle, 2023), and even ethically motivated consumers expressed a need for reassurance when confronting unfamiliar protein sources. Overall, reluctance toward protein alternatives appears less a rejection of sustainability or health per se, and more a reflection of cultural continuity and affective safety.

Complementary to the published evidence, a series of exploratory focus groups conducted by the Fontys Research Group (Floto-Stammen) between 2023 and 2025 with students, educators, and company representatives (N ≈ 200) repeatedly identified Tradition and Security as dominant personal values guiding food-related attitudes and choices. While these observations were not systematically analysed or published yet, they provide convergent, practice-based indications that align with the reviewed literature and support the treatment of these two values as “given” anchors in the subsequent communication design.

3.2. Communication Requirements

Findings from the synthesis were used to derive five communication requirements, identified through interpretive mapping of the two dominant values Tradition and Security onto food-related decision contexts. These requirements specify the emotional and behavioural conditions under which consumers may be more open to unfamiliar foods. Each requirement was grounded in thematic patterns observed across the reviewed studies that linked Tradition and Security to specific food-related attitudes and behaviours (see

Table 2 for key supporting literature).

If consumers’ food choices are anchored in cultural continuity and reassurance, communication needs to resonate with these underlying orientations. Cultural familiarity addresses Tradition by aligning new foods with recognisable formats, preparation practices, and sensory cues. Emotional safety reflects Security, focusing on reducing perceived risk and providing reassurance. Simplicity and clarity further support Security, ensuring that products appear easy to understand and integrate. Trust and credibility operationalise both values by relying on stable, reliable signals such as certifications and transparent labelling. Finally, routine integration corresponds to Tradition, emphasising everyday compatibility and continuity with established eating habits.

Recent packaging-communication research supports these requirements, showing that familiar and informative visual cues on packaging can reduce resistance such as disgust and enhance consumer trust toward insect-based and other alternative protein foods (Naranjo-Guevara et al., 2023). Earlier work on consumer acceptance among German and Dutch students likewise indicates that familiarity and clear information reducing uncertainty corresponding to the values of Tradition and Security are key predictors of openness toward insect-based foods (Naranjo-Guevara et al., 2020).

Together, these requirements define the emotional and behavioural conditions under which consumers may be more open to unfamiliar foods, providing the conceptual basis for designing values-centric communication.

3.3. Guidelines for Values-Centric Messaging

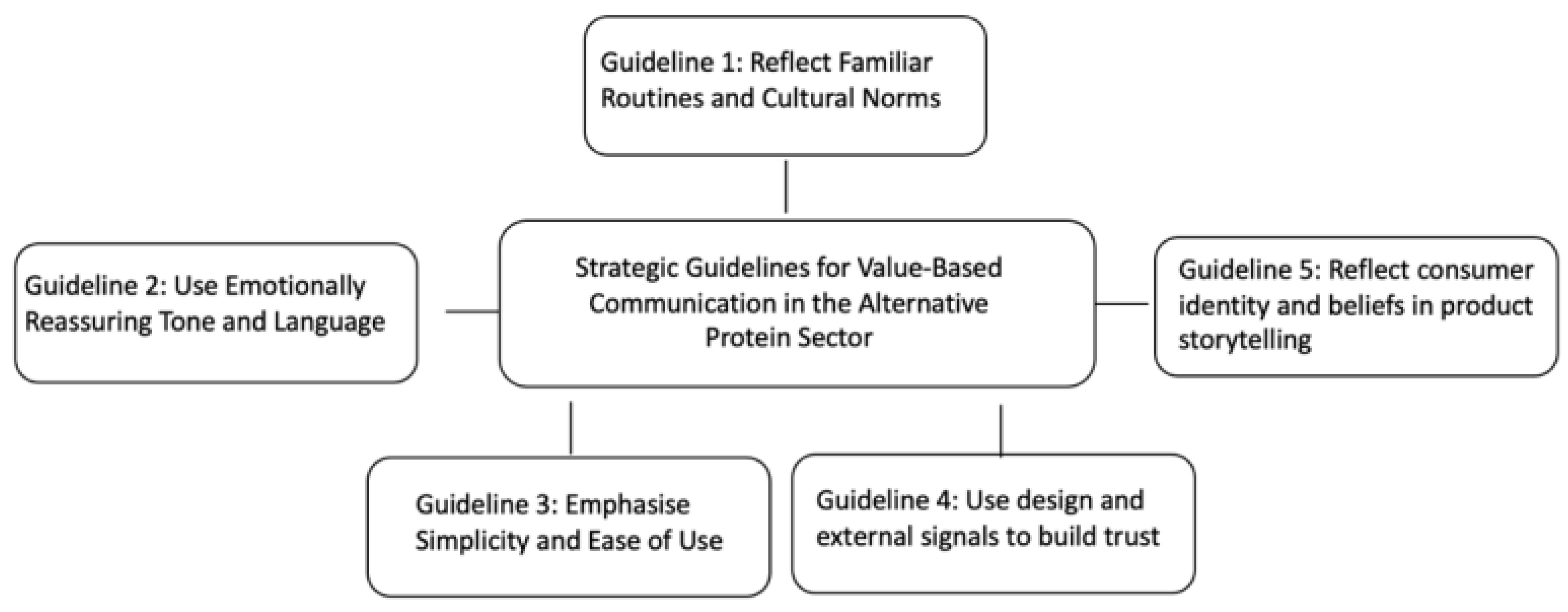

The five requirements were translated into values-centric communication guidelines, each grounded in the reviewed evidence and consistent with Schwartz’s value theory (See

Figure 2). First, reflect familiar routines and cultural norms by presenting products in formats recognisable within German food culture (e.g., sausages, burgers, meat balls); acceptance increased when novel proteins resembled traditional formats (Michel et al., 2021; Onwezen et al., 2021). Second, use an emotionally reassuring tone and language; wording associated with safety and predictability (e.g., “trusted,” “familiar”) tended to be better received, whereas technical or experimental phrasing elicited scepticism (Hempel & Roosen, 2024; Siddiqui et al., 2022). Third, emphasise simplicity and ease of use; consumers were more willing to adopt unfamiliar proteins when framed as “easy meal solutions” or accompanied by clear preparation cues (Brooker et al., 2022; Malek & Umberger, 2023). Fourth, employ design and external signals to build trust; certifications, origin and traceability labels, and transparent claims supported perceived credibility, particularly among Security-oriented consumers, while overly futuristic aesthetics could signal risk (Wu et al., 2021, Naranjo-Guevara et al., 2023). Fifth, connect products to consumer identity; storytelling that situates products within family, heritage, or lifestyle elicited stronger resonance than purely technical specifications (Brunk & De Boer, 2020; Weinrich, 2019). Collectively, these guidelines operationalise Tradition and Security into actionable principles.

3.4. Application to Packaging Claims

The guidelines were applied to front-of-pack communication to demonstrate operationalisation at the point of purchase (

Figure 2). Using a minimalistic reference pack (Catch Your Bug, 2025) as a neutral baseline, five short claims were drafted according to operational rules derived from repeated patterns in the literature (

Table 3). For instance, Cultural familiarity informed the claim “Your everyday crispy snack,” whereas Emotional safety informed “Trusted taste, made familiar.” This procedure ensured alignment of each claim with the values of Tradition and Security while maintaining a comparable visual balance across stimuli.

3.5. Consumer Responses

A single exploratory focus group (N = 7 German students) compared reactions to the original and refined packaging. Stimuli were presented in a fixed order (original then refined); order/contrast effects are acknowledged. Multiple elements were adjusted simultaneously in the refined version (imagery, headline, values-centric claims, trust icons), so responses reflect the combined stimulus. Analysis followed McGuire’s (1985) information-processing model, which conceptualises persuasion as a sequence of five stages—attention, comprehension, acceptance, retention, and action. Participant comments were thematically organised according to these stages to trace how packaging cues shaped initial perception, understanding, trust, recall, and self-reported behavioural intention.

Attention. With the original pack, first fixation typically fell on the insect image or the term “insects” and was frequently accompanied by aversive affect (e.g., “disgusting,” “confusing”). A minority first noticed “protein snack” but then shifted attention to the insects. With the refined pack, initial attention moved to the product image/headline (“Crispy Protein Bites”); two participants spontaneously described the bites as “tasty.” Several did not recognise the insect base until reading further (e.g., “I had to look again to realize it’s insect-based,” Speaker 4). Some uncertainty about taste/texture remained. Overall, greater Cultural familiarity reduced negative first reactions and enhanced Emotional safety at a glance.

Comprehension. For the original, participants understood that the product was insect-based and high-protein, but broader purpose or positioning was unclear and sometimes read as ironic/ambiguous (e.g., queries about whether it was intended as “comedy”). For the refined version, participants primarily interpreted it as a high-protein snack (fitness/health frame). Sustainability was inferred from claims (e.g., “eat for change,” “familiar taste”). A minority perceived ambiguity (e.g., bites seen as “raw”). In sum, Simplicity and clarity improved; partial masking of insect content increased neutrality but introduced some uncertainty.

Acceptance (credibility/trust). For the original, numeric claims (e.g., “52% protein”) and “Made in Germany” conveyed transparency/credibility, while affective unease about insects persisted (“trustworthy, but emotionally risky”). For the refined version, five participants reported higher trust due to a cleaner design, a certification icon, and origin labelling; two perceived information overload (“so much information… trying a little too hard”) and a claim–image mismatch (“doesn’t look crispy”), which reduced trust. Thus, credibility/trust improved via certification/origin, whereas Simplicity and clarity was undermined for some by dense text and visual–verbal incongruence.

Retention. For the original pack, the most frequently recalled elements were the insect image, the phrase “roasted cricket,” and the protein content; memorability of the image/headline skewed negative. A minority noted flavour descriptors (e.g., “lemon & pepper”), occasionally eliciting curiosity. For the refined pack, the certification icon “Certified”, “Crispy like home-cooked,” and “Eat for change without changing who you are” were commonly retained; the latter prompted self-reflection for one participant. The brand name “Catch Your Bug” continued to evoke aversive associations (e.g., “crawling insects”), counteracting otherwise reassuring cues. Identity-oriented phrasing supported Routine integration and Emotional safety when sufficiently salient; brand naming that primes insects undermined Emotional safety.

Action (self-reported intention). With the original pack, most participants stated they would not purchase; a few might try once in low-commitment contexts (e.g., social setting, discount) or if insects were non-visible (e.g., powdered). With the refined pack, more participants indicated they might consider purchase, citing familiar appearance, convenience framing (“on-the-go”), and reassuring tone. Some reported they would decline upon recognising the insect content; several noted that high information density reduced confidence. These shifts are consistent with improvements in Cultural familiarity and Emotional safety; persistent barriers centred on Simplicity and clarity surrounding insect disclosure.

Claim-level reactions. The headline “Crispy Protein Bites” (Guideline 1; Cultural familiarity) increased perceived familiarity (described as “snackable,” akin to common bite-sized snacks), though uncertainty about texture and flavour remained, indicating the need for stronger food-cue support. “Crispy like home-cooked. Familiar taste. Modern protein.” (Guideline 2; Emotional safety) was comforting for some; others questioned the specificity of “home-cooked” and noted incongruence between wording and imagery, attenuating reassurance. “Great snack. On the go. Anytime.” (Guideline 3; Simplicity and clarity) communicated ease of use effectively; however, overall front-of-pack text density limited perceived simplicity. Trust signals “Made in Germany,” a certification icon, and “Traceable ingredients” (Guideline 4; Trust and credibility) differed in salience: certification/origin cues were salient and generally increased credibility, whereas “traceable ingredients” was rarely mentioned; several participants indicated that dense layouts reduced visibility of these cues and that the product’s insect content was not always clear. Finally, “Eat for change without changing who you are.” (Guideline 5; Routine integration/identity) was memorable and resonant when noticed; reduced typographic prominence limited exposure.

Constraints specific to this test. The focus group was small and student-based (N = 7); stimulus order was fixed (original then refined), introducing potential contrast/priming; and multiple elements were adjusted concurrently in the refined pack (imagery, claims, icons), limiting attribution to any single component. Purchase intentions were self-reported and hypothetical. Within these constraints, the observed movement from immediate aversion toward consideration is consistent with the central roles of Tradition (format familiarity, routines, identity) and Security (reassurance, credible signals, cognitive ease) identified in the synthesis.

4. Discussion

This study developed and preliminarily examined a values-centric communication approach for alternative proteins in Germany. A synthesis of four recent studies, combined with the authors’ own exploratory work with focus groups (N ≈ 200), identified

Tradition and

Security as the dominant value drivers of everyday food choice (see

Section 3.1). From these, five communication requirements were derived: Cultural familiarity, Emotional safety, Simplicity and clarity, Trust and credibility, and Routine integration (

Section 3.2). They were operationalised into guidelines (

Section 3.3) and packaging claims (

Section 3.4). Exploratory evidence from a single focus group (

Section 3.5) indicated movement from immediate rejection toward consideration when messages and visuals increased familiarity and reassurance, while also revealing execution sensitivities (information load, claim–image mismatch, brand-name effects, and delayed recognition of insect content).

4.1. Theoretical Implications

First, the pattern of responses is consistent with the primacy of Tradition and Security in German food practices and with affect-first accounts of novel food avoidance. Early reactions were strongly emotional (e.g., disgust or aversive affect), aligning with classic work on disgust and food neophobia (Rozin & Fallon, 1987) and with the affect heuristic in risk perception, which suggests that people rely on affective impressions rather than analytical reasoning when evaluating novel risks (Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, 2004). Strengthening Cultural familiarity (recognisable formats, non-threatening visuals) and Emotional safety (reassuring tone) coincided with improvements at early persuasion stages (Attention, Comprehension), which is consistent with low-elaboration processing models in which peripheral cues guide attitude formation (McGuire, 1985).

Second, the data underscore the importance of cue congruence and processing fluency. Perceived inconsistency between the “crispy” claim and visual texture, as well as high front-of-pack (FOP) text density, coincided with weaker Simplicity and clarity and Trust and credibility. This pattern is consistent with evidence from advertising research showing that congruent visual–verbal cues enhance memory and persuasiveness (Mitchell, 1986) and with the concept of processing fluency, whereby low complexity and clear visual hierarchy facilitate liking and perceived truth (Reber, Schwarz, & Winkielman, 2004).

Third, Routine integration maps onto habit theory: food choices are often guided by stable scripts and contexts rather than deliberate decision-making, as shown in habit-based models of consumer behaviour (Verplanken & Wood, 2006). Positioning novel proteins to fit existing routines therefore provides a mechanism by which Tradition and Security values can be activated and maintained over time. Finally, the observed salience of certifications and origin labels aligns with work on credence attributes and consumer trust in food (Wu et al., 2021; Naranjo-Guevara et al., 2023), while identity-linked phrasing reflects findings from research on narrative processing and self–brand connections, which demonstrate that messages consistent with the consumer’s self-concept enhance engagement and acceptance (Escalas & Bettman, 2005; Sirgy, 1982).Together, these findings support the integration of Schwartz’s values framework with stage-based persuasion theory, suggesting that value activation (Tradition/Security) can be mapped onto stage-specific communication tasks (e.g., clarity for Comprehension; credible signals for Acceptance; identity resonance and routine fit for Retention).

4.2. Managerial Implications

Drawing on the synthesis and the exploratory focus-group evidence, several implications for practice emerge. First, strengthening cultural familiarity by presenting novel proteins in recognisable formats and ensuring claim–image congruence (e.g., visual texture consistent with “crispy”) appears to reduce initial aversion and support early-stage processing, consistent with established fluency and congruence effects (Reber, Schwarz, & Winkielman, 2004; Mitchell, 1986). Second, emotional safety is fostered by a reassuring tone and by avoiding technical or experimental framings that may elevate perceived risk under low elaboration (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Slovic, 1987); conversely, brand names that foreground insects can prime disgust and counteract reassurance (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2016). Third, simplicity and clarity are enhanced when FOP information is limited to a primary message with a clear visual hierarchy, reserving detail for secondary panels; excessive textual density undermines fluency and perceived credibility (van Herpen & van Trijp, 2011). Beyond perceptual and cognitive fluency, trust and identity-based mechanisms further support acceptance. Fourth, trust and credibility benefit from salient, concrete cues (e.g., certification marks, origin labels), consistent with findings from Naranjo-Guevara et al. (2023), whereas abstract phrasing (e.g., “traceable ingredients”) showed low salience without specific verifiable anchors. Finally, routine integration and identity alignment are supported when identity-linked claims are typographically prominent and narratively coherent, aiding recall and normalising adoption without threatening self-concept, which is in line with the concept of self-congruity and identity-based persuasion (Sirgy, 1982; Escalas & Bettman, 2005). These implications remain exploratory and should be treated as hypotheses for validation in larger, controlled studies.

4.3. Limitations

Interpretation is constrained by a small, student sample (N = 7), fixed order of exposure (original → refined), and bundled changes in the refined pack (imagery, multiple claims, icons), which limit attribution to any single element. Purchase intentions were hypothetical, and AI-generated stimuli may contain stylistic artefacts. The reference brand name itself introduced a persistent negative prime. These constraints are typical of exploratory qualitative tests and motivate the confirmatory designs outlined below.

4.4. Future Research

Future work should employ randomised, counterbalanced designs; factorial experiments to isolate the effects of imagery, tone, trust iconography, brand naming, and disclosure; larger and more diverse samples; and behavioural endpoints (e.g., choice tasks, field A/B). Research should also test values-based segmentation (weighting guidelines by audience) and evaluate transparent yet non-aversive disclosure of insect content (placement/wording) in light of known disgust/neophobia dynamics.

5. Conclusions

A values-centric approach foregrounding Tradition and Security, operationalised through Cultural familiarity, Emotional safety, Simplicity and clarity, Trust and credibility, and Routine integration, appears to reduce initial aversion and move German consumers toward consideration of alternative proteins. Exploratory focus-group evidence suggests that familiar formats, a reassuring tone, a clear visual hierarchy, and salient trust cues may improve early-stage responses, whereas information overload, claim–image incongruence, and value-incongruent naming impede acceptance. The study contributes an integrative analytic lens combining Schwartz’s value theory with McGuire’s communication–persuasion model, and a set of testable guidelines for values-aligned food communication. Given the exploratory design, findings should be regarded as preliminary; robust validation using counterbalanced, factorial, and behavioural designs with larger and more diverse samples remain a priority for future research.

References

- Amoneit, M. , Gellrich, L., & Weckowska, D. M. (2025). Consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Exploring determinants of the consumer willingness to buy in Germany. Foods, 14. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J. , Bailey, C. P., Evans, W. D., & Napolitano, M. A. (2022). Application of McGuire’s model to weight management messages: Measuring persuasion of Facebook posts in the Healthy Body, Healthy U trial for young adults attending university in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19. [CrossRef]

- Barska, A. (2014). Attitudes of young consumers towards innovations on the food market. Management, 18, 419–432.

- Brooker, P. G. , Hendrie, G. A., Anastasiou, K., Woodhouse, R., Pham, T., & Colgrave, M. L. (2022). Marketing strategies used for alternative protein products sold in Australian supermarkets in 2014, 2017, and 2021. Frontiers in Nutrition 9, 1087194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunk, K. H. , & De Boer, C. (2020). How do consumers reconcile positive and negative CSR-related information to form an ethical brand perception? A mixed-method inquiry. Journal of Business Ethics, 161. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C. J. (2022). Plant-based animal product alternatives are healthier and more environmentally sustainable than animal products. Future Foods, 6. [CrossRef]

- Catch Your Bug. (2025). Gewürzte Insektensnacks 3er-Pack (je 15 g). https://www.catch-your-bug.com/products/gewurzte-insekten-snacks.

- Crippa, M. , Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F. N., & Leip, A. (2021). Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food, 2. [CrossRef]

- Drulytė, R. , Daniusevičiūtė-Brazaitė, L., Mickevičius, V., & Tüür, A. (2022). Theoretical assumptions of values-based communication. Baltic Journal of Sport & Health Sciences, 2. [CrossRef]

- Dunne, D. (2020). Interactive: What is the climate impact of eating meat and dairy? Carbon Brief. https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/what-is-the-climate-impact-of-eating-meat-and-dairy/.

- EAT-Lancet Commission. (2025). Healthy diets from sustainable food systems: Progress, gaps, and pathways forward (EAT-Lancet 2.0 Report). The Lancet Commissions. https://eatforum.org/eat-lancet-commission/eat-lancet-commission-2-0/.

- Escalas, J. E. , & Bettman, J. R. (2005). Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. R. , Onwezen, M. C., & van der Meer, M. (2023). Consumer perceptions of different protein alternatives. In T. J. Troy & W. Chen (Eds.), Meat and meat replacements (pp. 333–362). Woodhead Publishing/Elsevier.

- Good Food Institute Europe. (2024, July 2). European consumer insights on the alternative protein sector. https://gfieurope.org/industry/european-consumer-insights-on-the-alternative-protein-sector/.

- Hartmann, C. , & Siegrist, M. (2016). Becoming an insectivore: Results of an experiment. Food Quality and Preference, 51. [CrossRef]

- Hajdari, M. (2023). Sustainable food consumption: A qualitative study of the factors and motivations influencing the switch in consumer behaviour towards sustainable food consumption in Germany (KCC Schriftenreihe der FOM, No. 4). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/268652/1/1833106423.pdf.

- Hempel, C. , & Roosen, J. (2024). Growing importance of price: Investigating food values before and during high inflation in Germany. Agricultural Economics. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2022). Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (P. R. Shukla, J. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2022). Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (P. R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, & J. Malley, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2023). Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (H. Lee & J. Romero, Eds.). Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC. [CrossRef]

- Koch, F. , Heuer, T., Krems, C., & Claupein, E. (2019). Meat consumers and non-meat consumers in Germany: A characterisation based on results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. Journal of Nutritional Science, 8. [CrossRef]

- Koch, F. , Krems, C., Heuer, T., & Claupein, E. (2021). Attitudes, perceptions and behaviours regarding meat consumption in Germany: Results of the NEMONIT study. Journal of Nutritional Science, 10. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2015). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Malek, L. , & Umberger, W. J. (2023). Protein source matters: Understanding consumer segments with distinct preferences for alternative proteins. Future Foods, 7. [CrossRef]

- Malila, Y. , Owolabi, I. O., Chotanaphuti, T., Sakdibhornssup, N., Elliott, C. T., Visessanguan, W., Karoonuthaisiri, N., & Petchkongkaew, A. (2024). Current challenges of alternative proteins as future foods. npj Science of Food, 8. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W. J. (1985). Attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 233–346). Random House.

- Michel, F. , Hartmann, C., & Siegrist, M. (2021). Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Quality and Preference, 87. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. A. (1986). The effect of verbal and visual components of advertisements on brand attitudes and attitude toward the ad. Journal of Consumer Research, 13. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Guevara, N. , Fanter, M., Conconi, A. M., & Floto-Stammen, S. (2020). Consumer acceptance among Dutch and German students of insects in feed and food. Food Science & Nutrition, 9. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Guevara, N. , Stroh, B., & Floto-Stammen, S. (2023). Packaging communication as a tool to reduce disgust with insect-based foods: Effect of informative and visual elements. Foods, 12. [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M. C. , Bouwman, E. P., Reinders, M. J., & Dagevos, H. (2021). A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite, 159. [CrossRef]

- Petty, R. E. , & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. [CrossRef]

- Poore, J. , & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360. [CrossRef]

- Reber, R. , Schwarz, N., & Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8. [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. , & Fallon, A. E. (1987). A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review 94(1), 23–41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeltz, L. (2014). Introducing value-based framing as a strategy for communicating CSR. Social Responsibility Journal, 10, 184–206.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2. [CrossRef]

- Seffen, A. E., & Dohle, S. (2023). What motivates German consumers to reduce their meat consumption? Identifying relevant beliefs. Appetite. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666323001460.

- Siddiqui, S. A. , Alvi, T., Sameen, A., Khan, S., Blinov, A. V., Nagdalian, A. A., Mehdizadeh, M., Adli, D. N., & Onwezen, M. (2022). Consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: A systematic review of current alternative protein sources and interventions adapted to increase their acceptability. Sustainability, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9. [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236. [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. , Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis, 24. [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M. , Clark, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Wiebe, K., Bodirsky, B. L., Lassaletta, L., de Vries, W., Vermeulen, S. J., Herrero, M., Carlson, K. M., Jonell, M., Troell, M., DeClerck, F., Gordon, L. J., Zurayk, R., Scarborough, P., Rayner, M., Loken, B., Fanzo, J., … Willett, W. (2018). Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 562(7728), 519–525. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tso, R. , Lim, A. J., & Forde, C. G. (2021). A critical appraisal of the evidence supporting consumer motivations for alternative proteins. Foods 10(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- van Herpen, E. , & van Trijp, H. C. M. (2011). Front-of-pack nutrition labels: Their effect on attention and choices when consumers have varying goals and time constraints. Appetite, 57. [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. (2015). Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Quality and Preference, 39. [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. , & Wood, W. (2006). Interventions to break and create consumer habits. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25. [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R. (2019). Opportunities for the adoption of health-based sustainable dietary patterns: A review on consumer research of meat substitutes. Sustainability, 11. [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R. , Strack, M., & Neugebauer, F. (2020). Consumer acceptance of cultured meat in Germany. Meat Science 162, 107924. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W. , Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., Jonell, M., Clark, M., Gordon, L. J., Fanzo, J., Hawkes, C., Zurayk, R., Rivera, J. A., De Vries, W., Majele Sibanda, L., … Murray, C. J. L. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. , Wang, S., Zhu, D., & Hu, W. (2021). Consumer trust in the food system: A critical review. Foods, 10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).