Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

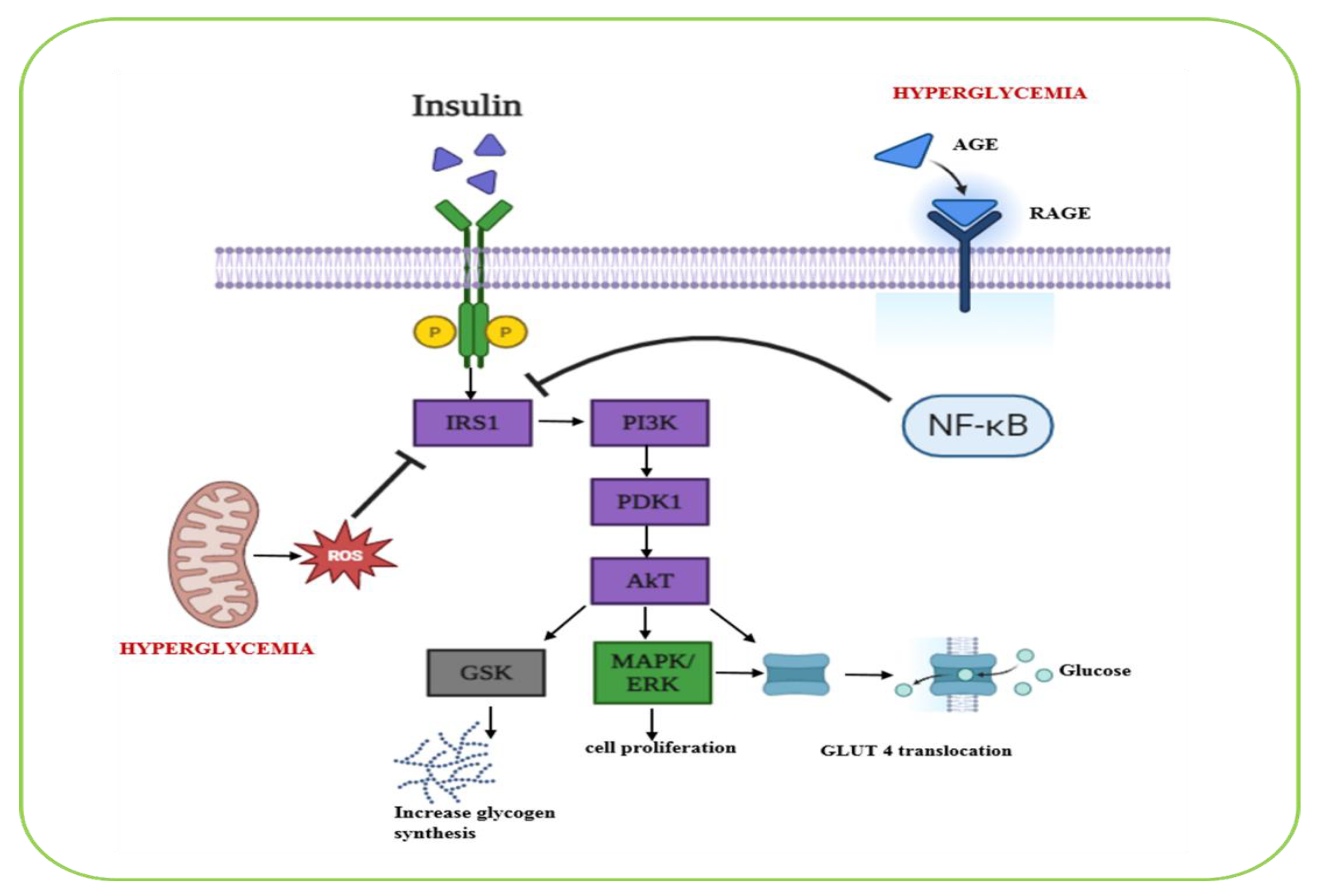

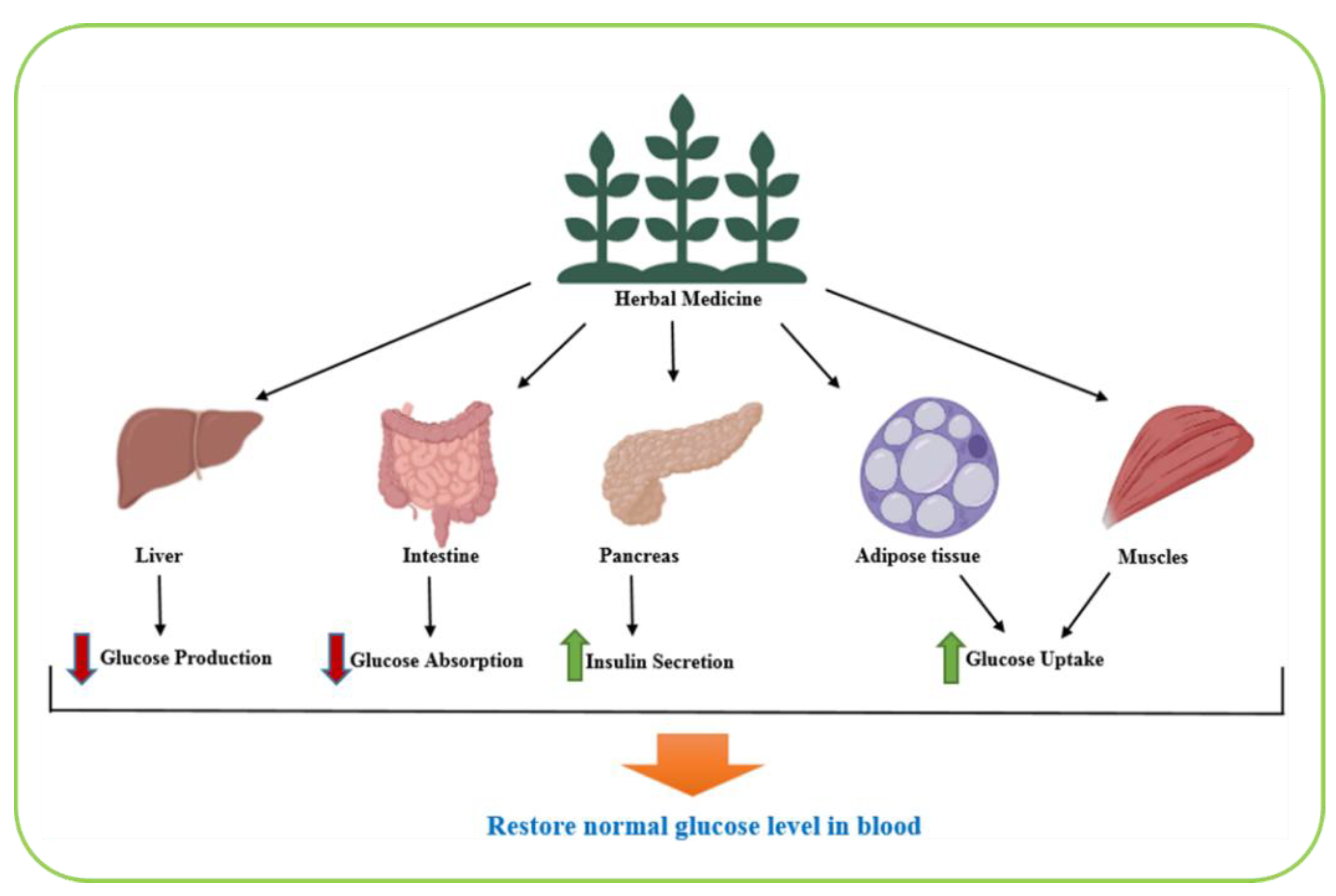

2. Biological Pathways Involved in Diabetes Management

3. Methodological Considerations and Quality Assessment

4. Medicinal Herbs: Past and Present Insights

5. Safety Considerations and Drug Interactions

6. Antidiabetic Medicinal Plants

6.1. Achyranthes aspera

6.2. Allium sativum

6.3. Aloe vera

6.4. Amaranthus tricolor (Lal Chaulai / Joseph’s Coat)

6.5. Anacardium occidentale (Cashew Tree)

6.6. Annona squamosa (Custard Apple / Sugar Apple)

6.7. Berberis vulgaris (Barberry)

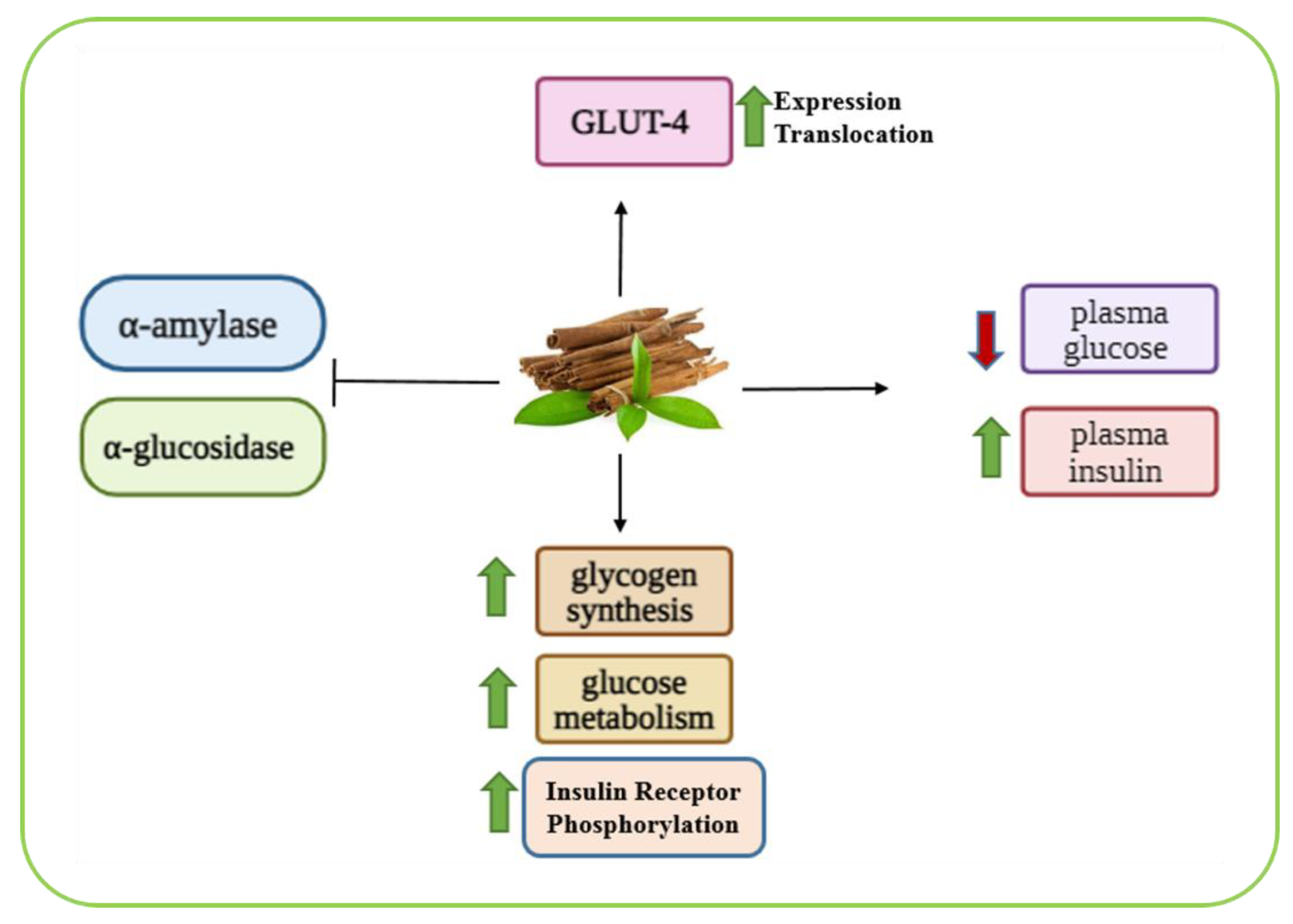

6.8. Cinnamomum zeylanicum

6.9. Curcuma longa (Turmeric)

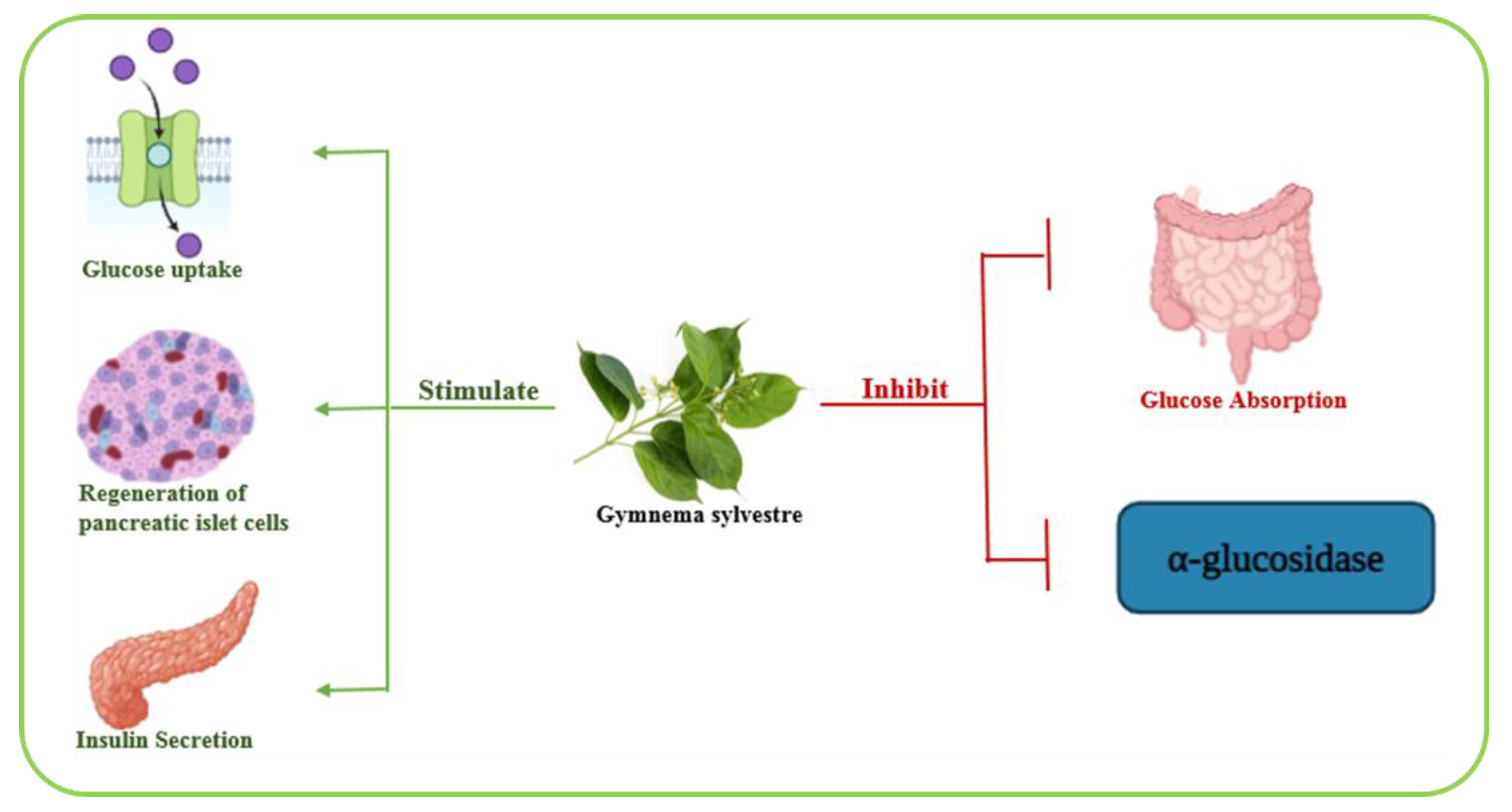

6.10. Gymnema sylvestre

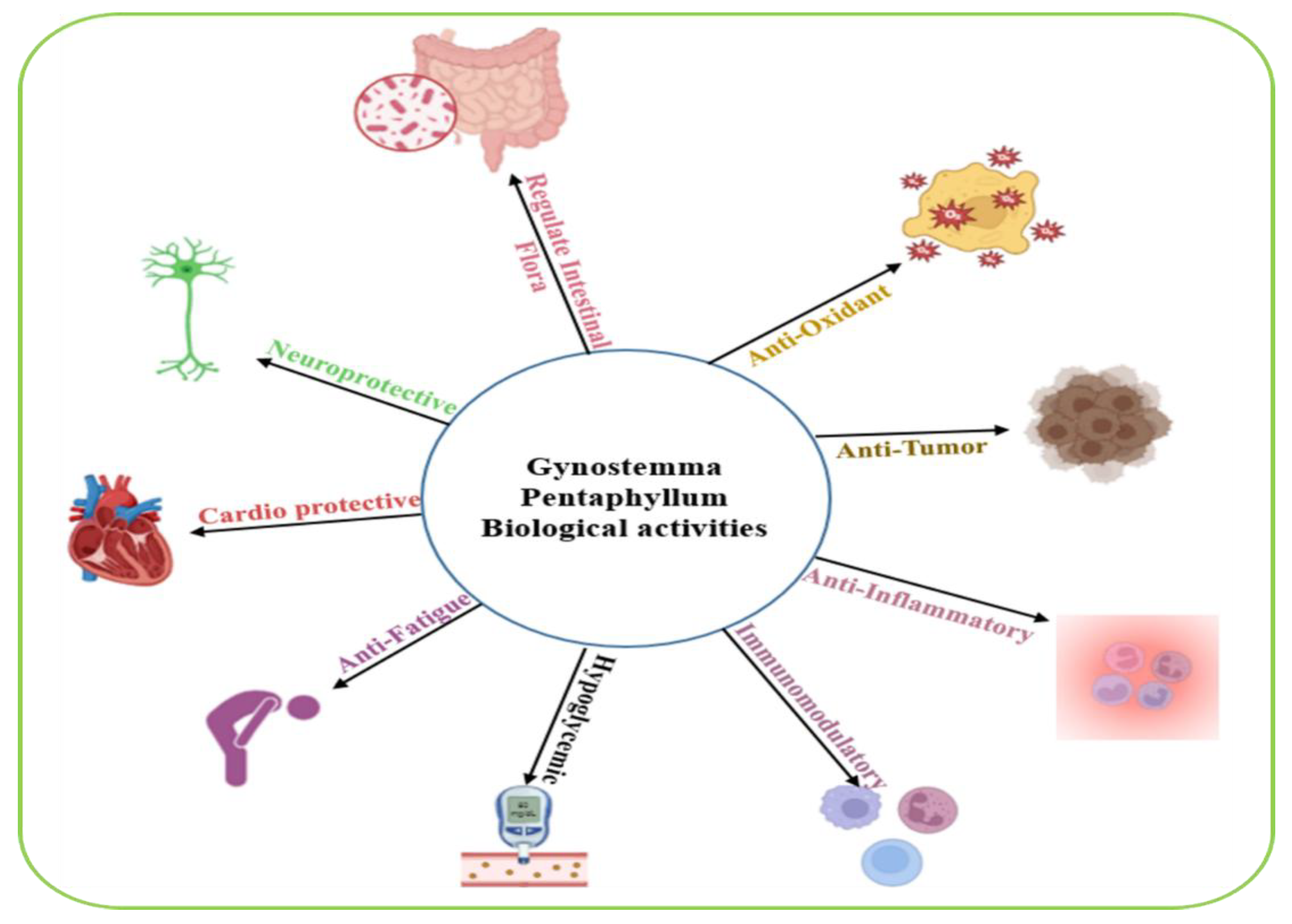

6.11. Gynostemma pentaphyllum

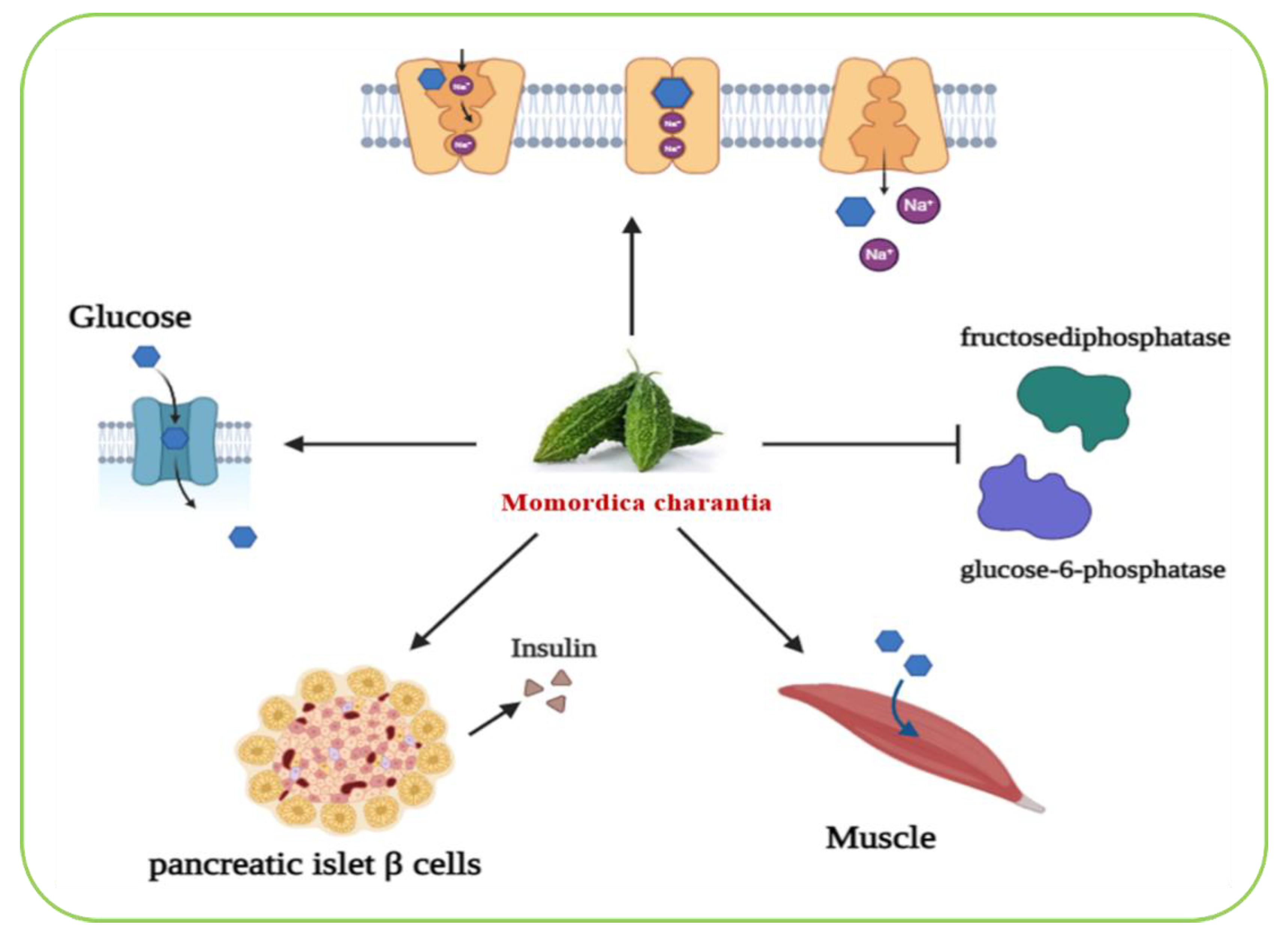

6.12. Momordica charantia

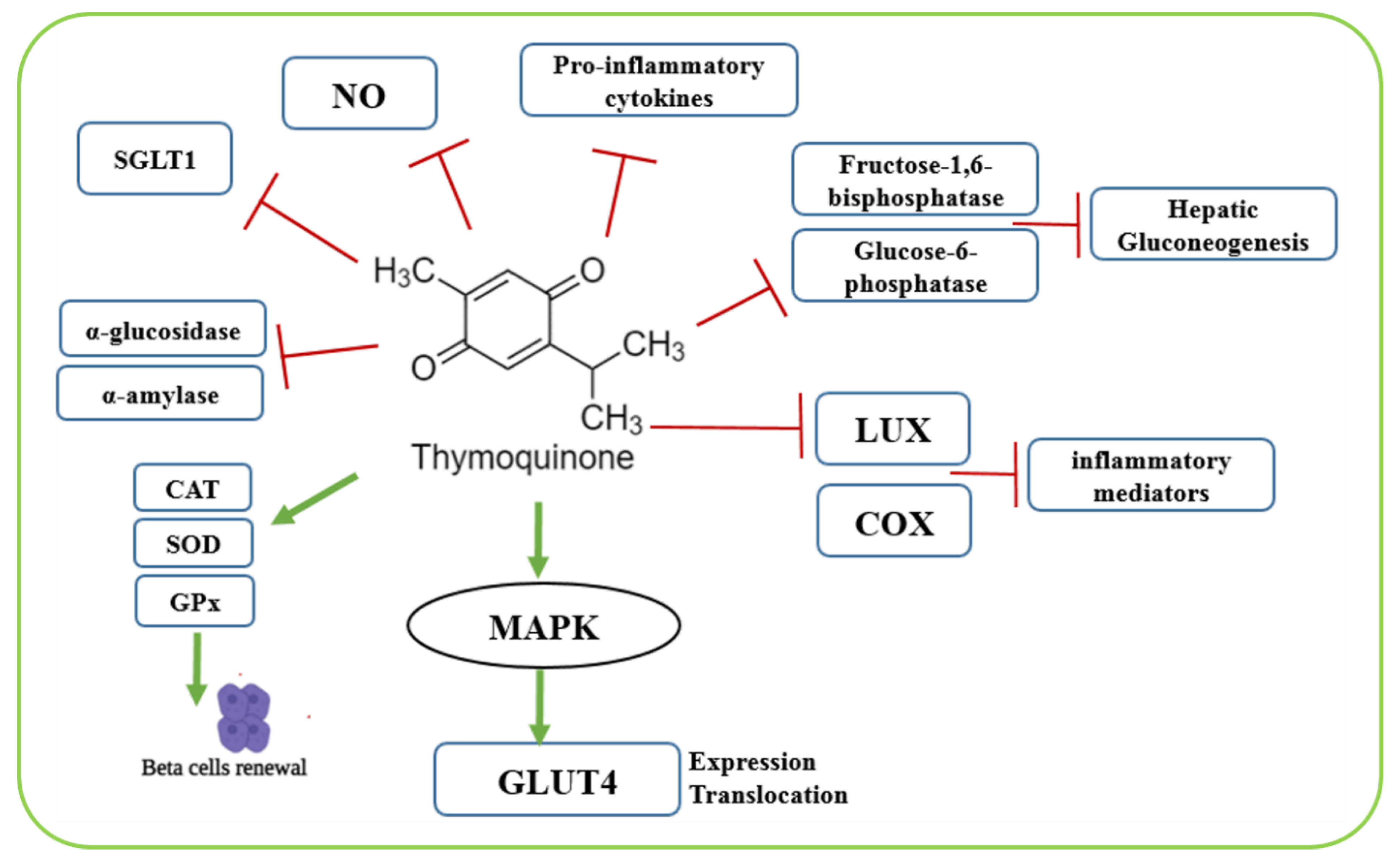

6.13. Nigella sativa (Black Seed / Black Cumin)

6.14. Ocimum sanctum

6.15. Punica granatum (Pomegranate)

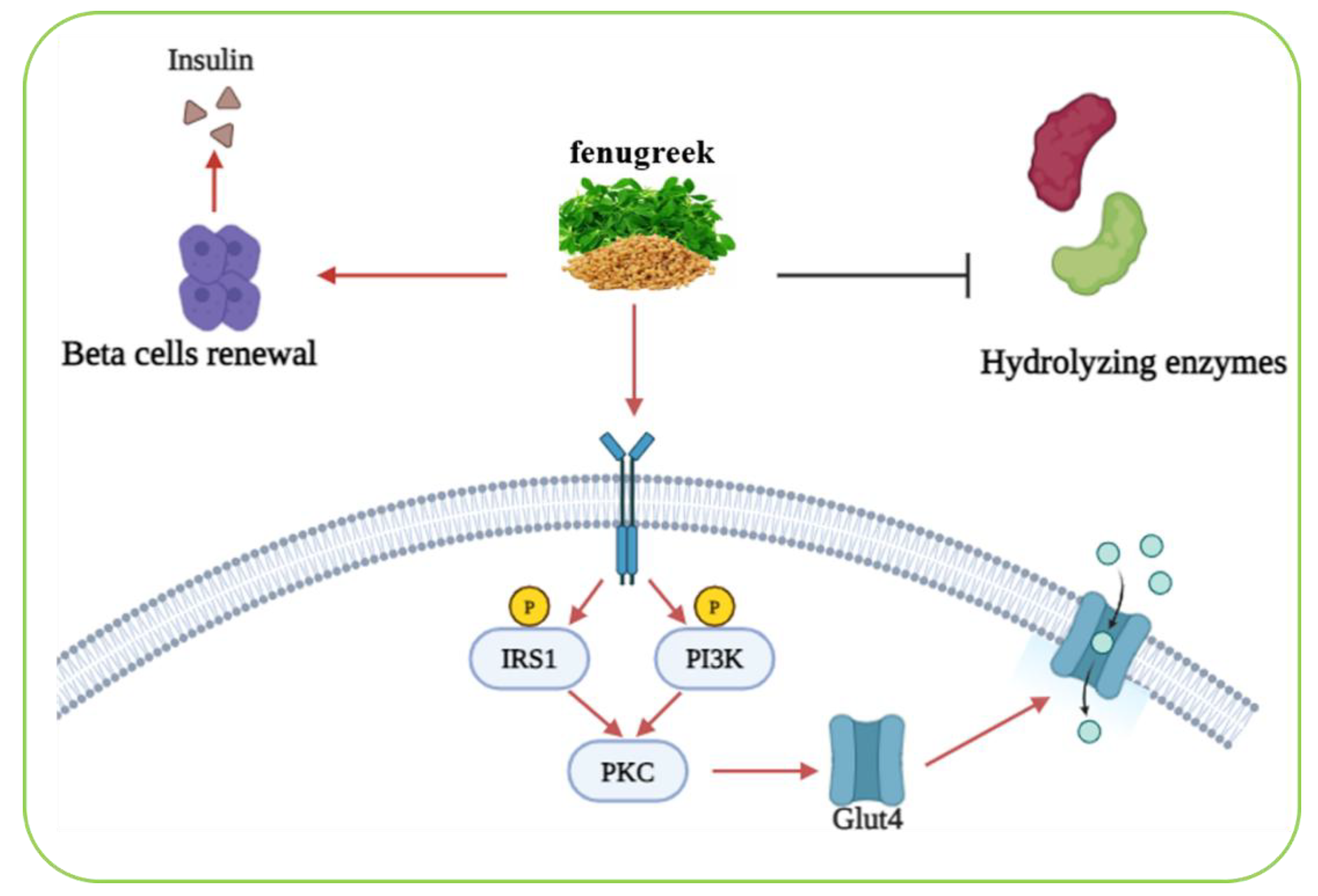

6.16. Trigonella foenum-graecum

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. WHO 2024, 14 November. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes.

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Sharaky, M.; Khattab, M.; Ashour, N.A.; Zaid, R.T.; Roh, E.J.; Elkamhawy, A.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Diabetes mellitus: Classification, mediators, and complications; A gate to identify potential targets for the development of new effective treatments. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115734. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Kolhatkar, M.K.; Sopane, D.K.; Thorve, A.N. Review on: Diabetes mellitus is a disease. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 13, 102–109. [CrossRef]

- Bastaki, S. A review diabetes mellitus and its treatment. Int. J. Diabetes Metab. 2005, 13, 111–134. [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.K. Diabetes Mellitus: A comprehensive review of pathophysiology, management, and emerging therapeutic approaches. Diabetes Mellitus 2023.

- Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Tong, N. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 262–286. [CrossRef]

- Savan, C.; Viroja, D.; Kyada, A. An updated review on diabetes mellitus: Exploring its etiology, pathophysiology, complications and treatment approach. IJCAAP 2024, 9, 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, B.A.; Adugna, A.; Yenet, A.; Yihunie Belay, W.; Yibeltal, Y.; Dagne, A.; Hibstu Teffera, Z.; Amare, G.A.; Abebaw, D.; Tewabe, H.; Abebe, R.B.; Zeleke, T.K. A critical review on diabetes mellitus type 1 and type 2 management approaches: From lifestyle modification to current and novel targets and therapeutic agents. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1440456–1440475. [CrossRef]

- Yameny, A.A. Diabetes mellitus overview. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 2024, 10, 641–645. [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Gadpayle, D.; Kumari, A.; Kaur, G.; Seen, K.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kumar, A. Antidiabetic potential of underutilized crops: Nutritional, phytochemical insights, and prospects for diabetes management. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101127. [CrossRef]

- Albahri, G.; Badran, A.; Hijazi, A.; Daou, A.; Baydoun, E.; Nasser, M.; Merah, O. The therapeutic wound healing bioactivities of various medicinal plants. Life 2023, 13, 317. [CrossRef]

- Enioutina, E.Y.; Salis, E.R.; Job, K.M.; Gubarev, M.I.; Krepkova, L.V.; Sherwin, C.M.T. Herbal Medicines: challenges in the modern world. Part 5. Status and current directions of complementary and alternative herbal medicine worldwide. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Ramachandra, T.V. A review on some therapeutic aspects of phytochemicals present in medicinal plants. Int. J. Pharm. Life Sci. 2019, 10, 6052–6058.

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial resistance: A one health perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Huemer, M.; Mairpady Shambat, S.; Brugger, S.D.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Antibiotic resistance and persistence—Implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, 51034–51057. [CrossRef]

- Forni, C.; Facchiano, F.; Bartoli, M.; Pieretti, S.; Facchiano, A.; D’Arcangelo, D.; Norelli, S.; Valle, G.; Nisini, R.; Beninati, S.; Tabolacci, T.; Jadeja, R.N. Beneficial Role of Phytochemicals on Oxidative Stress and Age-Related Diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Overy, A.J.; Büsselberg, D. Phytochemicals and Gastrointestinal Cancer: Cellular Mechanisms and Effects to Change Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 105. [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, M.K.; Khan, M.A.; Alalami, U.; Somvanshi, P.; Bhardwaj, T.; Pramodh, S.; Raina, R.; Shekfeh, Z.; Haque, S.; Hussain, A. Phytochemicals induce apoptosis by modulation of nitric oxide signaling pathway in cervical cancer cells. 2020, 24, 11827–11844. https://doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202011_23840.

- Lin, R.; Hu, X.; Chen, S.; Shi, Q.; Chen, H. Naringin induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis, inhibits β-catenin pathway and arrests cell cycle in cervical cancer cells. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2020, 67, 181-186. [CrossRef]

- Kooti, W.; Farokhipour, M.; Asadzadeh, Z.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Asadi-Samani, M. The role of medicinal plants in the treatment of diabetes: a systematic review. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 1832–1842. [CrossRef]

- Salleh, N.H.; Zulkipli, I.N.; Mohd Yasin, H.; Ja’afar, F.; Ahmad, N.; Wan Ahmad, W.A.N.; Ahmad, S.R. Systematic Review of Medicinal Plants Used for Treatment of Diabetes in Human Clinical Trials: An ASEAN Perspective. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hui, H.; Tang, G.; Go, V. Hypoglycemic herbs and their action mechanisms. Chin. Med. 2009, 4, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, V.L.; Shayesteh, R.; Foong Yun Loh, T.K.; Chan, S.W.; Sethi, G.; Burgess, K.; Lee, S.H.; Wong, W.F.; Looi, C.Y. Comprehensive review of opportunities and challenges of ethnomedicinal plants for managing type 2 diabetes. Heliyon 2024, 10, 39699–39714. [CrossRef]

- Zanzabil, K.Z.; Hossain, M.S.; Hasan, M.K. Diabetes mellitus management: An extensive review of 37 medicinal plants. Diabetology 2023, 4, 186–234. [CrossRef]

- Asiago, O.H.; Reddy, K.S. Protective effect of achyranthes aspera against high fat diet and streptozotocin induced diabetes in rats [Adventure]. Journal of Chemical Health Risks, 13(6), 3124–3131. https://www.jchr.org.

- Vijayaraj, R.; Naresh Kumar, K.; Mani, P.; Senthil, J.; Jayaseelan, T.; Dinesh Kumar, G. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant activity of Achyranthes aspera seed extract and its effect on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Res. 2016, 7, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Priyamvada, P.M; Mishra, P.; Sha, A.; Mohapatra, A.K. Evaluation of antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of Achyranthes aspera leaf extracts: An in vitro study. Int. J. Pharm. Life Sci. 2021, 10, 103–110. Priyamvada, Mishra, P., Sha, A., & Mohapatra, A. K. (2021). Evaluation of antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of Achyranthes aspera leaf extracts: An in vitro study. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 10(4), 103–110. https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2021/vol10issue4/PartB/10-5-12-481.pdf.

- Njideka, B.E.; Theophilus, A.E.N.; Ugochukwu, N.T. Use of Achyranthes aspera Linn Tea as antidiabetic and hypolipidemic herbal tea. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2019, 9, 32–38. Njideka, B. E., Theophilus, A. E. N., & Ugochukwu, N. T. (2019). Use of Achyranthes aspera Linn Tea as Antidiabetic and Hypolipidemic Herbal Tea. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 9(2), 32–38. https://www.ijhsr.org/IJHSR_Vol.9_Issue.2_Feb2019/6.pdf.

- Sanie-Jahromi, F.; Zia, Z.; Afarid, M. A review on the effect of garlic on diabetes, BDNF, and VEGF as a potential treatment for diabetic retinopathy. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 18–31. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Gao, W.; Li, X.; Luo, S.; Wu, D.; Chye, F.Y. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) polysaccharide ameliorates type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) via the regulation of hepatic glycogen metabolism. NFS J. 2023, 31, 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, N.; Masoumi, S.J. The Effect of garlic (allium sativum) supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Int. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 3, 7–11.

- Abdullah, H.; Miladiyah, I. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Efficacy as an adjuvant therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A scoping review. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Cardiovascular Diseases (ICCvD 2021); Nurdiyanto, H.; Miladiyah, I.; Jamil, N.A., Eds.; Atlantis Press International BV: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 419–434. [CrossRef]

- Choo, T.-M. Nigella sativa tea mitigates type-2 diabetes and edema: A case report. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2023, 23, 1249–1254. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, D.; Zhao, T.; Tian, H. Efficacy of Aloe Vera supplementation on prediabetes and early non-treated diabetic patients: A Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2016, 8, 388–397. [CrossRef]

- Harshali, Thakur, P.; Mukherjee, G. Aloe Vera as an Antidiabetic and Wound Healing Agent for Diabetic Patients. JPRI 2021, 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Budiastutik, I.; Subagio, H.W.; Kartasurya, M.I.; Widjanarko, B.; Kartini, A.; Soegiyanto, S.; Suhartono, S.S. The effect of aloe vera on fasting blood glucose levels in pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2022, 10, 737–747. [CrossRef]

- Abo-Youssef, A.M.H.; Messiha, B.A.S. Beneficial effects of aloe vera in treatment of diabetes: comparative in vivo and in vitro studies. Bull. Fac. Pharm. Cairo Univ. 2013, 51, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Pathomwichaiwat, T.; Jinatongthai, P.; Prommasut, N.; Ampornwong, K.; Rattanavipanon, W.; Nathisuwan, S.; Thakkinstian, A. Effects of turmeric (curcuma longa) supplementation on glucose metabolism in diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: An umbrella review and updated meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, 288997–289017. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Mahbubur Rahman, A.; Iffat Ara Gulshana, M. Taxonomy and medicinal uses on amaranthaceae family of rajshahi, Bangladesh. AEES 2014, 2, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Aneja, S.; Vats, M.; Aggarwal, S.; Sardana, S. Phytochemistry and hepatoprotective activity of aqueous extract of Amaranthus tricolor Linn. Roots. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2013, 4, 211–217. [CrossRef]

- Rahmatullah, M.; Hosain, M.; Rahman, S.; Rahman, S.; Akter, M.; Rahman, F.; Rehana, F.; Munmun, M.; Kalpana, M. antihyperglycemic and antinociceptive activity evaluation of methanolic extract of whole plant of Amaranthus Tricolor L. (Amaranthaceae). Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 10, 408–411. [CrossRef]

- Rahma, K.; Nurcahyanti, O. Therapeutic effect of red spinach (Amaranthus tricolor L.) extract on pancreatic MDA levels rats (Rattus norvegicus) exposed to MLD-STZ. J. Biomed. Transl. Res. 2021, 7, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, M.; Asif M.Bano, B. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activity of Annona squamosa extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Singapore Med. J., 2006, 47, 670–675. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16865205/.

- Ajao, F.O.; Iyedupe, M.O.; Akanmu, O.; Kalejaiye N.O.; Adegoke A.L.; Adeniji, L.A. Anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic efficacy of Anacardium occidentale leaf extract in diabetic rats. Int J Diabetes Clin Res., 2023, 10, 177–188. https://doi: 10.23937/2377-3634/1410177.

- Jaiswal, Y.S.; Tatke, P.A.; Gabhe, S.Y.; Vaidya, A.B. Antidiabetic activity of extracts of Anacardium occidentale Linn. leaves on n-streptozotocin diabetic rats. J. Tradi. Complement. Med., 2017, 7, 421–427. [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Mora, A.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Lavandera, J.L.; Giebelhaus, R.T.; Domenech-Bendaña, A.; Locascio, A.; Gutierrez-Rojas, I.; Sauro, S.; De La Mata, P.; Nam, S.L.; Méril-Mamert, V.; Sylvestre, M.; Harynuk, J.J.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G.; Bejarano, E. Systematic characterization of antioxidant shielding capacity against oxidative stress of aerial part extracts of Anacardium occidentale. Antioxidants, 2025, 14, 935–961. [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, S. and Olatunji, G.A. Antidiabetic activity of Anacardium occidentale in alloxan – diabetic rats. Jnl Sci Tech., 2010, 30, 35–41. [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, L.A.; Okwusidi, J.I.; and Soladoye, A.O. Antidiabetic effect of Anacardium occidentale.Stem-bark in fructose-diabetic rats. Pharm. Biol., 2005, 43, 589–593. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-C.; Mong, M.-C.; Wu, W.-T.; Wang, Z.-H.; Yin, M.-C. Phytochemical profiles and anti-diabetic benefits of two edible amaranthus species. CyTA J. Food 2020, 18, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Almalki, G.; Alothman, N.; Mohamed, G.; Akeel, M.; El-Beltagy, A.E.-F.B.; Mahmoud, A.M. Amaranthus tricolor L. leaf extracts improve glucose homeostasis and lipid profile in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113372–113381. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.P.; Singh, A.; Prasad, R.K.; Mishra, D.K.; Singh, A.K.; Yadav, S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activity of Annona squamosa bark using successive solvent extraction method. J. Complement. Herb. Res., 2024, 14, 2004–2013.

- Sharma, A.; Chand, T.; Khardiya, M.; Yadav, K.C.; Mangal, R.; Sharma, A.K. Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activity of Annona squamosa fruit peel in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res., 2013, 4, 200–208.

- Gupta, R.K.; Kesari, A.N.; Watal, G.; Murthy, P.S.; Chandra, R.; Maithal, K.; Tandon, V. Hypoglycaemic and antidiabetic effect of aqueous extract of leaves of Annona squamosa (L.) in experimental animals. Curr. Sci., 2005, 88, 1192–1196. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24110293.

- Muszalska, A.; Wiecanowska, J. Berberis vulgaris: A natural source of berberine for addressing contemporary health concerns. Herba Pol. 2024, 70, 13–38. [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Zhao, L.-H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, T.-Y.; Wang, H.; Gu, C.-J.; Tong, X.-L. Application of berberine on treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Meliani, N.; Dib, M.E.A.; Allali, H.; Tabti, B. Hypoglycaemic effect of Berberis vulgaris L. in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2011, 1, 468–471. [CrossRef]

- Shidfar, F.; Ebrahimi, S.S.; Hosseini, S.; Heydari, I.; Shidfar, S.; Hajhassani, G. The effects of Berberis vulgaris fruit extract on serum lipoproteins, apoB, apoA-I, homocysteine, glycemic control and total antioxidant capacity in type 2 diabetic patients. Iran J. Pharm.Res. 2012, 11, 643–652.

- Belwal, T.; Bisht, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Ullah, H.; Khan, H.; Pandey, A.; Bhatt, I.D.; Echeverría, J. Phytopharmacology and Clinical Updates of Berberis Species Against Diabetes and Other Metabolic Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 41–67. [CrossRef]

- Munguia-Nolan, J.E.; García-Puga, J.A.; Robles-Zepeda, R.E.; Quintana-Zavala, M.O.; Díaz-Zavala, R.G.; Rendón-Domínguez, I.P. Efectos de Cinnamomum zeylanicum en Niveles Glucémicos en Pacientes con Diabetes Tipo 2: Ensayo Clínico Aleatorizado. Enf. Global 2024, 23, 59–82. [CrossRef]

- Senevirathne, B.S.; Jayasinghe, M.A.; Pavalakumar, D.; Siriwardhana, C.G. Ceylon cinnamon: A versatile ingredient for futuristic diabetes management. J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 125–142. [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Jayawardana, R.; Galappaththy, P.; Constantine, G.R.; De Vas Gunawardana, N.; Katulanda, P. Efficacy and safety of ‘true’ cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) as a pharmaceutical agent in diabetes: A Systemic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, 1480–1492. [CrossRef]

- Shihabudeen, H.M.S.; Priscilla, D.H.; Thirumurugan, K. Cinnamon extract inhibits α-glucosidase activity and dampens postprandial glucose excursion in diabetic rats. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Medagama, A.B. The glycaemic outcomes of Cinnamon, a review of the experimental evidence and clinical trials. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 108–119. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Ito, Y.; Muraki, E.; Hosono, T.; Seki, T.; Ariga, T. Verification of the antidiabetic effects of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) using insulin-uncontrolled type 1 diabetic rats and cultured adipocytes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 2418–2425. [CrossRef]

- Yaghmoor, S.S.; Khoja, S.M. Effect of Cinnamon on plasma glucose concentration and the regulation of phosphofructo-1-kinase activity from the liver and small intestine of streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 10, 761–766. [CrossRef]

- Taher, M.; Abdul Majid, F.A.; Sarmidi, M.R. A proanthocyanidin from Cinnamomum zeylanicum stimulates phosphorylation of insulin receptor in 3T3–L1 adipocytes. J. Teknol. 2006, 74, 53–68. [CrossRef]

- Fallah Huseini, H.; Kianbakht, S.; Hajiaghaee, R.; Afkhami-Ardekani, M.; Bonakdaran, A.; Dabaghian, F. Aloe Vera leaf gel in treatment of advanced type 2 diabetes mellitus needing insulin therapy: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Med. Plants 2012, 11, 23–28.

- Rivera-Mancía, S.; Trujillo, J.; Chaverri, J.P. Utility of curcumin for the treatment of diabetes mellitus: evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. J. Nutr. Intermediary Metab. 2018, 14, 29–41. [CrossRef]

- Marton, L.T.; Pescinini-e-Salzedas, L.M.; Camargo, M.E.C.; Barbalho, S.M.; Haber, J.F.D.S.; Sinatora, R.V.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Girio, R.J.S.; Buchaim, D.V.; Cincotto Dos Santos Bueno, P. The effects of curcumin on diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 669448–669459. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, W.; Khan, R.A.; Baig, M.T.; Shaikh, S.A.; Kumar, A. Role of Curcuma Longa in Type 2 Diabetes and Its Associated Complications. JPRI 2021, 33, 369–376. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Shahidi, F.K.; Khorsandi, K.; Hossienzadeh, R.; Asma, G.; Balick, V. An update on molecular mechanisms of curcumin effect on diabetes. J. Food Biomech. 2022, 46, 653–669. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Fu, M.; Gao, S-H.; Liu, J-L. Curcumin and diabetes: A systematic review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 1, 636053–636068. [CrossRef]

- Chuengsamarn, S.; Rattanamongkolgul, S.; Luechapudiporn, R.; Phisalaphong, C.; Jirawatnotai, S. Curcumin extract for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2121–2127. [CrossRef]

- Kanetkar, P.; Singhal, R.; Kamat, M. Gymnema sylvestre: A memoir. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2007, 41, 77–81. [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, H.; Qamar, I.; Bashir, M.; Jabeen, F.; Irfan, S.; Anwar, H. Gymnema sylvestre Supplementation Restores Normoglycemia, Corrects Dyslipidemia, and Transcriptionally Modulates Pancreatic and Hepatic Gene Expression in Alloxan-Induced Hyperglycemic Rats. Metabolites 2023, 13, 516–531. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Kwak, M.; Jin, J.-O. Clinical applications of Gymnema sylvestre against type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated abnormalities. Prog. Nutr. 2019, 21, 258–269. [CrossRef]

- Gaonkar, V.P.; Hullatti, K. Indian Traditional medicinal plants as a source of potent Anti-diabetic agents: A Review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 1895–1908. [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Nasir, A.; Gulzaman; Rafique, M.K.; Abbas, M.; Ur Rehman, A.; Riaz, M.; Rasool, G.; Mtewa, A.G. Unlocking the anti-diabetic potential of Gymnema syvestre, Trigonella foenum-graecum, and their combination thereof: An in vivo evaluation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7664–7672. [CrossRef]

- Huyen, V.T.T.; Phan, D.V.; Thang, P.; Ky, P.T.; Hoa, N.K.; Ostenson, C.G. Antidiabetic effects of add-on Gynostemma pentaphyllum extract therapy with sulfonylureas in type 2 diabetic patients. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Wei, S. Gynostemma pentaphyllum: A review on its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 124, 106651–106674. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Tan, D.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L. Gypenoside ameliorates insulin resistance and hyperglycemia via the AMPK-mediated signaling pathways in the liver of type 2 diabetes mellitus mice. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1347–1354. [CrossRef]

- Huyen, V.T.T.; Phan, D.V.; Thang, P.; Hoa, N.K.; Östenson, C.G. Gynostemma pentaphyllum tea improves insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.-B.; Xie, P.; Guo, M.; Li, F.-F.; Xiao, M.-Y.; Qi, Y.-S.; Pei, W.-J.; Luo, H.-T.; Gu, Y.-L.; Piao, X.-L. Protective effect of heat-processed Gynostemma pentaphyllum on high fat diet-induced glucose metabolic disorders mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1215150–1215164. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.; Jini, D. Antidiabetic effects of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) and its medicinal potency. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013, 3, 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Birtwhistle, R.; Kotecha, J.; Hannah, S.; Cuthbertson, S. Anti-diabetic and hypoglycaemic effects of Momordica charantia (Bitter Melon): A mini review. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 1703–1708. [CrossRef]

- Richter, E.; Geetha, T.; Burnett, D.; Broderick, T.L.; Babu, J.R. The effects of Momordica charantia on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4643. [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Cummings, E.; Phoenix, D.A.; Singh, J. Beneficial effect and mechanism of action of Momordica charantia in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: A mini review. Int. J. Diabetes Metab. 2003, 11, 46–55. [CrossRef]

- Oyelere, S.F.; Ajayi, O.H.; Ayoade, T.E.; Santana Pereira, G.B.; Dayo Owoyemi, B.C.; Ilesanmi, A.O.; Akinyemi, O.A. A detailed review on the phytochemical profiles and anti-Diabetic mechanisms of Momordica charantia. Heliyon 2022, 8, 9253–9263 . [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi-Sardoo, H.; Sepahi, S.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Askari, V.R. Application of Nigella sativa as a functional food in diabetes and related complications: Insights on molecular, cellular, and metabolic effects. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 122, 106518–106550. [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Zaidi, A.; Anwar, H.; Kizilbash, N. Mechanism of the antidiabetic action of Nigella sativa and Thymoquinone: a review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1126272–1126299. [CrossRef]

- Maideen, N.M.P. Antidiabetic activity of nigella sativa (black seeds) and its active constituent (thymoquinone): A review of human and experimental animal studies. Chonnam Med. J. 2021, 57, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.; Haji Idrus, R.; Mokhtar, M.H. Effects of nigella sativa on type-2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4911–4922. [CrossRef]

- El-Aarag, B.; Hussein, W.; Ibrahim, W.; Zahran, M. Thymoquinone improves anti-diabetic activity of metformin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats. J. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 8, 1000780-1000787. [CrossRef]

- Afaf Jamal Ali Hmza, E.; Omar, A.; Adnan, A.; Osman, M.T. Nigella sativa oil has significant repairing ability of damaged pancreatic tissue occurs in induced type 1 diabetes mellitus. Glob. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 7, 14–19.

- Choo, T.-M. Nigella sativa tea mitigates type-2 diabetes and edema: A case report. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2023, 23, 1249–1254. [CrossRef]

- Hannan, J.M.A.; Marenah, L.; Ali, L.; Rokeya, B.; Flatt, P.R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Ocimum sanctum leaf extracts stimulate insulin secretion from perfused pancreas, isolated islets and clonal pancreatic β-Cells. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 189, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Abhilash Rao, S.; Vijay, Y.; Deepthi, T.; Sri Lakshmi, C.; Vibha Rani, S.; Swetha Rani, B.; Bhuvaneswara Reddy, Y.; Ram Swaroop, P.; Sai Laxmi, V.; Nikhil Chakravarthy, K.; Arun, P. Anti-diabetic effect of ethanolic extract of leaves of ocimum sanctum in alloxan induced diabetes in rats. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 2, 613. S, A., Y, V., T, D., Ch, S., Rani, V., Rani, S., Y, B., P, R., V, S., K, N., & P, A. (2013). Anti diabetic effect of ethanolic extract of leaves of Ocimum sanctum in alloxan induced diabetes in rats. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 2(5), 613. [CrossRef]

- Suanarunsawat, T.; Anantasomboon, G.; Piewbang, C. Anti-diabetic and anti-oxidative activity of fixed oil extracted from Ocimum sanctum L. leaves in diabetic rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 11, 832–840. [CrossRef]

- Cheurfa, M.; Achouche, M.; Azouzi, A.; Abdalbasit, M.A. Antioxidant and anti-diabetic activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) leaves extracts. Foods Raw Maters, 2020, 8, 329–336. [CrossRef]

- Gharib, E. Kouhsari, S.M. Study of the antidiabetic activity of Punica granatum L. fruits aqueous extract on the alloxan-diabetic wistar rats. Iran. J. Pharm. Res., 2019, 18, 358–368. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6487419/.

- Tang, D.; Liu, L.; Ajiakber, D.; Ye, J.; Xu, J.; Xin, X.; Aisa, H.A. Anti-diabetic Effect of Punica granatum Flower Polyphenols Extract in Type 2 Diabetic Rats: Activation of Akt/GSK-3β and Inhibition of IRE1α-XBP1 Pathways. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 586–596. [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk Gabr, N. Effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fresh juice and peel extract on diabetic male albino rats. AMJ., 2017, 46, 965–980. [CrossRef]

- Haxhiraj, M.; White, K.; Terry, C. The role of fenugreek in the management of type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6987–6997. [CrossRef]

- Laila, O.; Murtaza, I.; Muzamil, S.; Imtiyaz Ali, S.; Abid Ali, S.; Ahamad Paray, B.; Gulnaz, A.; Vladulescu, C.; Mansoor, S. Enhancement of nutraceutical and anti-diabetic potential of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum). Sprouts with natural elicitors. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Baset, M.E.; Ali, T.I.; Elshamy, H.; El Sadek, A.M.; Sami, D.; Badawy, M.; Abou-Zekry, S.; Heiba, H.; Saadeldin, M.; Abdellatif, A. Anti-Diabetic Effects of Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum): A Comparison between Oral and Intraperitoneal Administration—An Animal Study. Int. J. Funct. Nutr. 2020, 1, 2–10. [CrossRef]

- Ota, A.; Ulrih, N.P. An overview of herbal products and secondary metabolites used for management of type two diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 436–449. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Aswal, S.; Chauhan, A.; Semwal, R.B.; Kumar, A.; Semwal, D.K. Ethnomedicinal investigation of medicinal plants of Chakrata region (Uttarakhand) used in the traditional medicine for diabetes by Jaunsari tribe. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2019, 9, 175–200. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, D.K.; Ray, P.; Dutta, A.K.; Rouf, R.; Uddin, S.J. Antidiabetic potential of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum): A magic herb for diabetes mellitus. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 7108–7136. [CrossRef]

| Plant name | Family | Used plant parts | Mode of action | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achyranthes aspera | Amaranthaceae | Seed, Leaf | ● Inhibits the activities of glucosidase enzymes Reduces oxidative damage and increases the expression of the pancreatic insulin protein |

[26,28] |

| Allium sativum |

Amaryllidaceae | Whole plant | ● Inhibits the enzyme alpha glucosidase Increases insulin sensitivity |

[32,33] |

| Aloe vera | Liliaceal | Whole plant | ● Inhibits glycation pathway Affects insulin secretion rate |

[35,37] |

| Amaranthus tricolor | Amaranthaceae | Leaf and stem | Prevents oxidative stress in cells Stimulates anti-α-amylase, anti-α-glucosidase properties |

[42,43] |

| Anacardium occidentale | Anacardiaceous | Leave and stem | ● Improves hepatic and renal functions Enhances β-cell functions |

[49] |

| Annona squamosa | Annonaceae | Roots, seeds, leaves and fruits | ● Stimulates glucose uptake and the release of the insulin hormone | [53] |

| Berberis vulgaris | Berberidaceae | Fruit | ● Inhibits fructose-induced insulin resistance Downregulates the expression of aldose reductase Improves the sensitivity and the secretion of insulin Inhibits the release of glucagon Stimulates the proliferation of pancreatic β-cells and that of the GLP-1 hormone secretion which plays a role in insulin secretion Upregulates the expression of insulin receptor proteins Inhibits key enzymes contribution to glucose regulation |

[55,56,58,59] |

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Lauraceae | Whole plant | ● Inhibits pancreatic α-amylase and α-glucosidase by stimulating the synthesis of glycogen and the metabolism of glucose Enhances GLUT-4 production and translocation |

[62,63,65] |

| Curcuma longa |

Zingiberaceae | Root | ● Improves the overall functions of b-cells Reduces the levels of metabolic parameters |

[73,74] |

| Gymnema sylvestre | Asclepiadaceae | leaves | ● Modulates several gene expressions, contributing to diabetes control | [76] |

| Gynostemma pentaphylium |

Cucurbitaceae | ● | ● Improves insulin sensitivity Increases the expression of GLUT4 Decreases the histological liver damage |

[83,84] |

| Momordica charantia |

Cucurbitaceae | Fruit | ● Controls glucose transportation Reduces gluconeogenic enzymes (such as glucose-6-phosphatase and fructosebiphosphatase) Increase the levels of intestinal Na+/glucose co-transporters, protectors of pancreatic islet β cells |

[87,88,89] |

| Nigella sativa |

Ranunculaceae | Whole plant | ● Blocks α-glucosidase and α-amylase digestive enzymes Reduces gluconeogenesis in the liver Inhibits the intestinal glucose transporters Increases the secretion of antioxidant enzymes Stimulates pancreatic-cell proliferation |

[90,91,92,93] |

| Ocimum sanctum | Lamiaceae | Leaves | ● Increases the intra cellular calcium concentration of beta islet cells | [98] |

| Punica granatum |

Lythraceae | Leave and flower | ● Increases the secretion of pancreatic β-cells Stimulates the mRNAs expression of IRS-1 and Akt genes Increases the activity of CAT enzymes and improves the health of pancreatic islets of Langerhans |

[101,103] |

| Trigonella foenum-graecum | Fabaceae | Seeds and leaves | Overexpresses of GLUT2 mRNA Renews β-cell and promotes insulin secretion stimulation Inhibits lipid-and carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes Stimulates translocation of GLUT4 to cell membrane |

[106,107,108,109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).