1. Introduction

Nigella sativa (

N. Sativa), commonly known as black cumin, originates from the Middle East and is mentioned in the Bible (Isaiah 38). Known since Roman antiquity, it has been appreciated in India for both cooking and medicine. It is also part of traditional Koranic medicine and was used in Europe until the seventeenth century before being gradually abandoned.

N. sativa is frequently used in traditional medicine in the Middle East and some Asian countries for its medicinal properties, particularly in treating several diseases. Additionally, it is used as a flavoring additive for traditional bread and biscuits. The traditional use of

N. sativa has inspired many researchers to isolate its active components and conduct in vivo and in vitro studies on laboratory animals and humans to understand its pharmacological effects. Among the observed effects are antioxidant [

1,

2] and hypoglycemic [

3] properties, among others.

Regarding the olive tree, its use is ingrained in human culture. Archaeologists believe the domestication of the olive tree occurred around 3800 to 3200 BC, approximately six millennia ago. Archaeo-biological studies, and genetic studies of olive tree populations and varieties [

4] suggest that domestication occurred independently in several regions of the Mediterranean basin over a long period. Archaeological research indicates that oil extraction was already taking place as early as the fourth millennium BC in Syria and Cyprus, and in Crete around 3500 BC. Around 1700 years ago, the technique improved, and the first simple "tree presses" appeared in Ugarit (Syria).

The olive tree is one of the most mentioned plants in the Bible. After the flood, the dove released by Noah returned holding an olive branch in its beak (Genesis 8:11). Jacob smeared olive oil on the stone of Beth El after his vision of the heavenly ladder (Genesis 35:14). In Judaism and Christianity, olive oil is used for sacramental anointings, symbolizing peace, reconciliation, blessing, and sacrifice. The oil used during the rites of Judaism must be pressed by hand. In the Qur'an, the olive tree is described as a blessed tree, symbolizing universal man, with olive oil as a source of divine light due to its purity (Qur'an 23:20, 24:35). According to some ahadith narrated by Sayyid Al-Ansari, Abdullah bin Umar, and Abu Huraira in the compilations of At-Tirmidhi 2000 and Ibn Majah, Muhammad said, "Consume (olive) oil and rub it on your face, for it comes from a blessed tree."

The olive tree (

Olea europaea L.) is widely recognized for its medicinal applications, particularly its leaves, which possess diuretic [

5], hypotensive [

6], vasodilatory, cholesterol-lowering, hypoglycemic, and weight-loss properties [

7]. These attributes have been harnessed in the formulation of proprietary pharmaceuticals. Additionally,

Olea europaea has demonstrated antihyperglycemic effects in animal studies [

6].

Together with

Nigella sativa L., another plant known for its traditional use in managing diabetes,

Olea europaea plays a pivotal role in addressing a critical global health challenge. Diabetes currently affects an estimated 463 million people worldwide, as reported by the World Health Organization [

8].

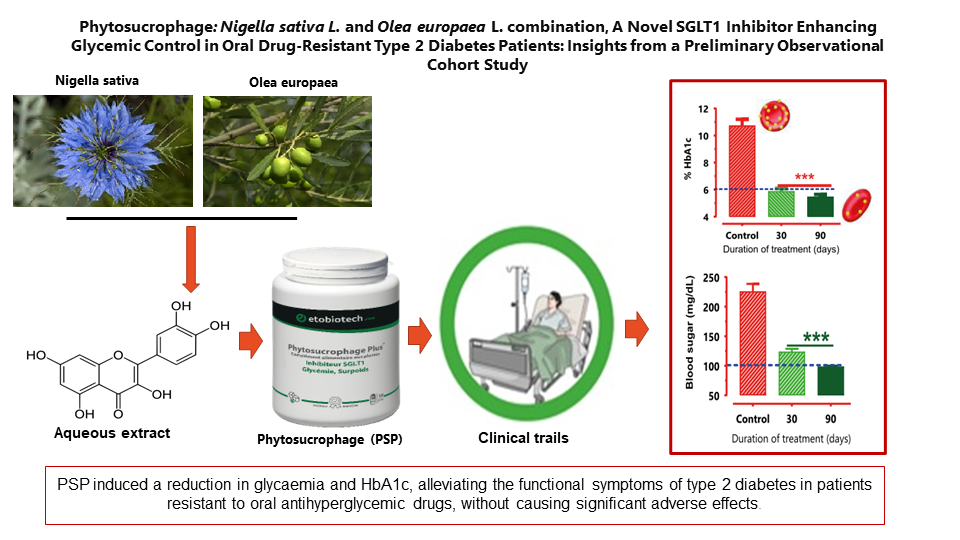

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of Phytosucrophage (PSP), a combination of Nigella sativa and Olea europaea extracts, in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients resistant to oral antihyperglycemic drugs.

2. Material and Methods

This observational cohort study was conducted at the Chad-China Friendship Hospital in N'Djamena. A total of 320 patients participated in this preliminary study, conducted between October 2013 and December 2021. The study received approval from the National Ethics Committee (Approval No. 679/PR/PM/MSP/SE/SG/DHATC/SGH/SRH/13). Phytosucrophage (Biodiabétine), approved under N°2018-2-140, was kindly donated by Laboratoires TBC France.

2.1. Study Design

Patients were eligible if they met the following criteria:

1. Diagnosed with T2DM before the date of signing the consent form.

2. Treated with oral medication and/or insulin without significant improvement in glycaemia or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) for more than 3 months.

3. Naive patients on a diet regimen alone.

4. Diagnosed with HbA1c > 7% and ≤ 16% at the first medical visit or with fasting blood glucose concentration ≥ 150 mg/dL.

5. Patients included in the study were over 18 years old and provided signed informed consent at Visit 1, in compliance with good clinical practices.

Exclusion criteria included patients with heart conditions, liver dysfunction, or kidney dysfunction.

The clinical benefits of oral PSP administration were evaluated. All patients received 550 mg of PSP three times daily, administered 10–15 minutes before meals for 90 days. Blood glucose levels and biochemical parameters were analyzed on days -7, 0, 30, 60, and 90.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± standard error (S.E.) of n patients. ANOVA was performed, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-test using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 for Windows (San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Benefit of Oral Administration of Phytosucrophage (PSP).

The effect of PSP treatment was evaluated by measuring fasting blood vein glucose concentration on days 0, 30, 60, and 90. The concomitant administration of PSP with oral antidiabetic medications (metformin, Glibenclamide, or glimepiride) induced a significant reduction (p<0.001) in fasting blood vein glucose concentration. This reduction was not directly dependent on the basal value before treatment. We observed that when the basal fasting blood glucose concentration was more than 235 mg/dL, PSP could reduce glycaemia to 133 mg/dL within a month, whereas this reduction was close to 100 mg/dL after two months.

We studied the effect of PSP on glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in naive patients and in patients receiving oral medication (baseline glucose-lowering therapies - BGLT) before oral administration of PSP. All combinations with PSP showed a significant reduction in HbA1c blood concentration, suggesting the clinical benefit of using PSP in combination with oral antidiabetic drugs. The use of PSP in combination with insulin plus Glimepiride or insulin plus Glibenclamide also showed a significant reduction in HbA1c blood concentration.

3.2. Effect of PSP on Serum Aminotransferase Activities and Creatinine

During the clinical trial period, aminotransferase and creatinine levels were monitored to assess whether the combination of PSP and oral antihyperglycemic drugs might impact liver function. The results indicated that the combination of PSP and oral antihyperglycemic drugs had no effect on hepatic aminotransferase levels or creatinine function (see Table 2).

3.3. Effect of PSP on Functional Adverse Effects and Symptoms of T2DM

During medical visits, adverse effects and different symptoms of T2DM were evaluated and noted, including thirst, vomiting, dry mouth, abdominal pain, impotence, headache, paresthesia, dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, pollakiuria, and urinary frequency (see Table 3). At the first endpoint, we noted a significant remission of major side effects of diabetes in patients.

4. Discussion

The global situation regarding type 2 diabetes is becoming increasingly concerning. Approximately 422 million people worldwide have diabetes, with the majority residing in low- and middle-income countries. Diabetes is directly responsible for 1.5 million deaths annually. Both the number of cases and the prevalence of diabetes have been steadily rising over the past few decades. For individuals living with diabetes, access to affordable treatment, including insulin, is essential for survival. The World Health Organization has set a globally agreed target to halt the rise in diabetes and obesity by 2025 [

9].

However, oral antidiabetic medications may not be effective for some individuals with type 2 diabetes, particularly those with poor glycemic control or long-standing diabetes. In such cases, clinicians may prescribe a combination of oral antidiabetics with different mechanisms of action to achieve better glucose control. In some instances, oral antidiabetics may also be combined with insulin injections, which provide synthetic insulin directly to the body. The choice of medication and dosage is determined by several factors, including the individual's blood glucose levels, weight, kidney function, and potential side effects.

People with type 2 diabetes in low-income countries often do not have access to medicines. Some diabetic individuals cannot follow a healthy diet due to food shortages. For these people, the only solution left is to use traditional treatments.

Clinical studies in humans were initially prioritized for diabetic patients who were resistant to oral antidiabetics under Baseline Glucose-Lowering Therapies (BGLT). This decision was made for ethical reasons, as it was the first time clinical studies were conducted on diabetic patients. To minimize any risk to the health of the participants and provide them with the best opportunity to normalize their blood sugar levels, we chose to use PSP as a therapeutic supplement. Only after confirming the positive clinical benefits of PSP in these patients did, we extend the trials to treatment-naive patients with an HbA1c of 9.18 ± 2.37.

Patients were eligible if they were confirmed to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes before the date of signing the consent form and treated with oral medication and/or insulin without significant improvement in glycaemia or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) for more than 3 months. Naive patients, who were on a diet regimen alone, were also eligible.

The clinical studies demonstrated that PSP improved glycemic control in all patients with type 2 diabetes. A reduction in blood glucose was observed after just one week of treatment. Meanwhile, the decrease in HbA1c became measurable after 30 days of treatment and remained below 7% after 60 days.

Nigella sativa inhibits SGLT1 [

10]. Both SGLT1 and SGLT2 are sodium-glucose cotransporters that play crucial roles in glucose homeostasis and represent promising targets for diabetes treatment. SGLT1 facilitates glucose uptake in the small intestine [

10] and reabsorption in the kidney, while SGLT2 is responsible for reabsorbing most of the filtered glucose in the kidney. Inhibitors of these transporters can lower blood glucose levels by reducing intestinal absorption.

Clinical trials have shown the efficacy of SGLT inhibitors as monotherapy or add-on therapy for type 2 diabetes, with additional benefits such as weight loss and blood pressure reduction [

11]. However, excessive inhibition of SGLT1 may lead to gastrointestinal side effects. SGLT inhibitors regulate blood sugar without relying on insulin, offering sustained glucose control and a minimal risk of hypoglycemia for individuals with type 2 diabetes. These inhibitors may also play a role in combination with insulin for managing type 1 diabetes [

12].

Nigella sativa has been shown to decrease weight in animals [

10]. We hypothesize that reducing glucose absorption limits the conversion of excess glucose into fat storage. Furthermore, we suggest that inhibiting intestinal glucose absorption by blocking SGLT1 could also reduce the absorption of chylomicrons. Chylomicrons, which transport lipids, are absorbed in the intestinal villi. To enter the lymphatic vessels, they must pass through tight junctions between the endothelial cells that form the vessel walls, with this process facilitated by an increase in the hydrostatic pressure within the villi [

13]. We propose that increased hydrostatic pressure promotes the passage of chylomicrons by widening the tight junctions. Since glucose stimulates the absorption of sodium and, consequently, water, it may increase local hydrostatic pressure, thereby promoting lipid absorption.

In conclusion, our findings support the use of PSP to reduce glycemia and HbA1c in diabetic patients resistant to oral antihyperglycemic drugs, without significant adverse effects. These data suggest that SGLT1 inhibition mediated by PSP is a viable mechanism of action for treating T2DM. Further confirmation of these findings through controlled clinical trials is recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: BE, JMB, BG, JFD. Data Curation, Formal Analysis: BE, AO, RN, JMB, ZLA, MJ, ENT. Funding Acquisition, Investigation: AAD, BI, IR, CT, PP, KT, NM, CJ. Methodology: BE, JMB, RN, ASA. Project Administration: BE, AAD. Resources: BE, JFD. Software: BE, JMB, AO. Supervision: BE, JMB, BG, JFD. Validation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review & Editing: BE, JMB.

Patents

The patent resulting from the work reported in this manuscript is WO/2009/053652.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the TBC Laboratory (Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lille) for their assistance and helpful discussions. In addition, the authors express their gratitude to the TBC Laboratory for contributing to the funding of the clinical studies and research associated with this project.

Abbreviations

| ALT |

alanine aminotransferase |

| AST |

aspartate aminotransferase |

| BGLT |

Baseline glucose-lowering therapies |

| CDF |

commercial dosage form |

| CRT |

creatinine |

| CT |

control |

| Glib |

Glibenclamide, |

| Glim |

Glimepiride, |

| HbA1c |

glycosylated hemoglobin |

| IQR |

Inter quartile range, ou écart inter quartiles |

| LDL |

low density lipoprotein |

| MET |

metformin |

| NS |

Nigella sativa L. |

| OE |

Olea europaeaL.

|

| PSP |

Phytosucrophage |

| SGLT1 |

sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter-1 |

| SGLT2 |

sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter-2 |

| T2DM |

type 2 diabetes |

| TBC |

Laboratoires TBC. |

| VLDL |

very low-density lipoprotein |

References

- S.C. Nair, M.J. Salomi, B. Panikkae, K.R. Panikkar, Modulatory effects of Crocus sativus and Nigella sativa extracts on cisplatin-induced toxicity in mice, J. Ethnopharmacol. 31 (1991) 75–83. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Badary, A.B. Abdel-Naim, M.H. Abdel-Wahab, F.M. Hamada, The influence of thymoquinone on doxorubicin-induced hyperlipidemic nephropathy in rats, Toxicology 143 (2000) 219–226. [CrossRef]

- F.M. Al-Awadi, K.A. Gumaa, Studies on the activity of individual plants of an antidiabetic plant mixture, Acta Diabetol. Lat. 24 (1987) 37–41. [CrossRef]

- G. Besnard, P. Baradat, C. Breton, B. Khadari, A. Bervillé, Olive domestication from structure of oleasters and cultivars using nuclear RAPDs and mitochondrial RFLPs, Genet. Sel. Evol. 33 (2001) S251. [CrossRef]

- L. Melillo, Diuretic plants in the paintings of Pompeii, Am. J. Nephrol. 14 (1994) 423–425. [CrossRef]

- S. FK, On treatment of hypertension with folia oleae substances and a sali-diuretic, Med. Welt 42 (1960) 2226–2228.

- L.I. Somova, F.O. Shode, P. Ramnanan, A. Nadar, Antihypertensive, antiatherosclerotic and antioxidant activity of triterpenoids isolated from Olea europaea, subspecies africana leaves, J. Ethnopharmacol. 84 (2003) 299–305. [CrossRef]

- I.W. Suryasa, M. Rodríguez-Gámez, T. Koldoris, Health and treatment of diabetes mellitus, Int. J. Health Sci. 5 (2021). [CrossRef]

- E.W. Gregg, J. Buckley, M.K. Ali, J. Davies, D. Flood, R. Mehta, B. Griffiths, L.-L. Lim, J. Manne-Goehler, J. Pearson-Stuttard, improving health outcomes of people with diabetes: target setting for the WHO Global Diabetes Compact, The Lancet 401 (2023) 1302–1312.

- B. Meddah, R. Ducroc, M.E.A. Faouzi, B. Eto, L. Mahraoui, A. Benhaddou-Andaloussi, L.C. Martineau, Y. Cherrah, P.S. Haddad, Nigella sativa inhibits intestinal glucose absorption and improves glucose tolerance in rats, J. Ethnopharmacol. 121 (2009) 419–424. [CrossRef]

- H. Kakinuma, T. Oi, Y. Hashimoto-Tsuchiya, M. Arai, Y. Kawakita, Y. Fukasawa, I. Iida, N. Hagima, H. Takeuchi, Y. Chino, (1 S)-1, 5-anhydro-1-[5-(4-ethoxybenzyl)-2-methoxy-4-methylphenyl]-1-thio-d-glucitol (TS-071) is a potent, selective sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for type 2 diabetes treatment, J. Med. Chem. 53 (2010) 3247–3261. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Tahrani, A.H. Barnett, C.J. Bailey, SGLT inhibitors in management of diabetes, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 1 (2013) 140–151.

- D.M. McDonald: Tighter lymphatic junctions prevent obesity, Science 361 (2018) 551–552. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).