Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Preparation

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

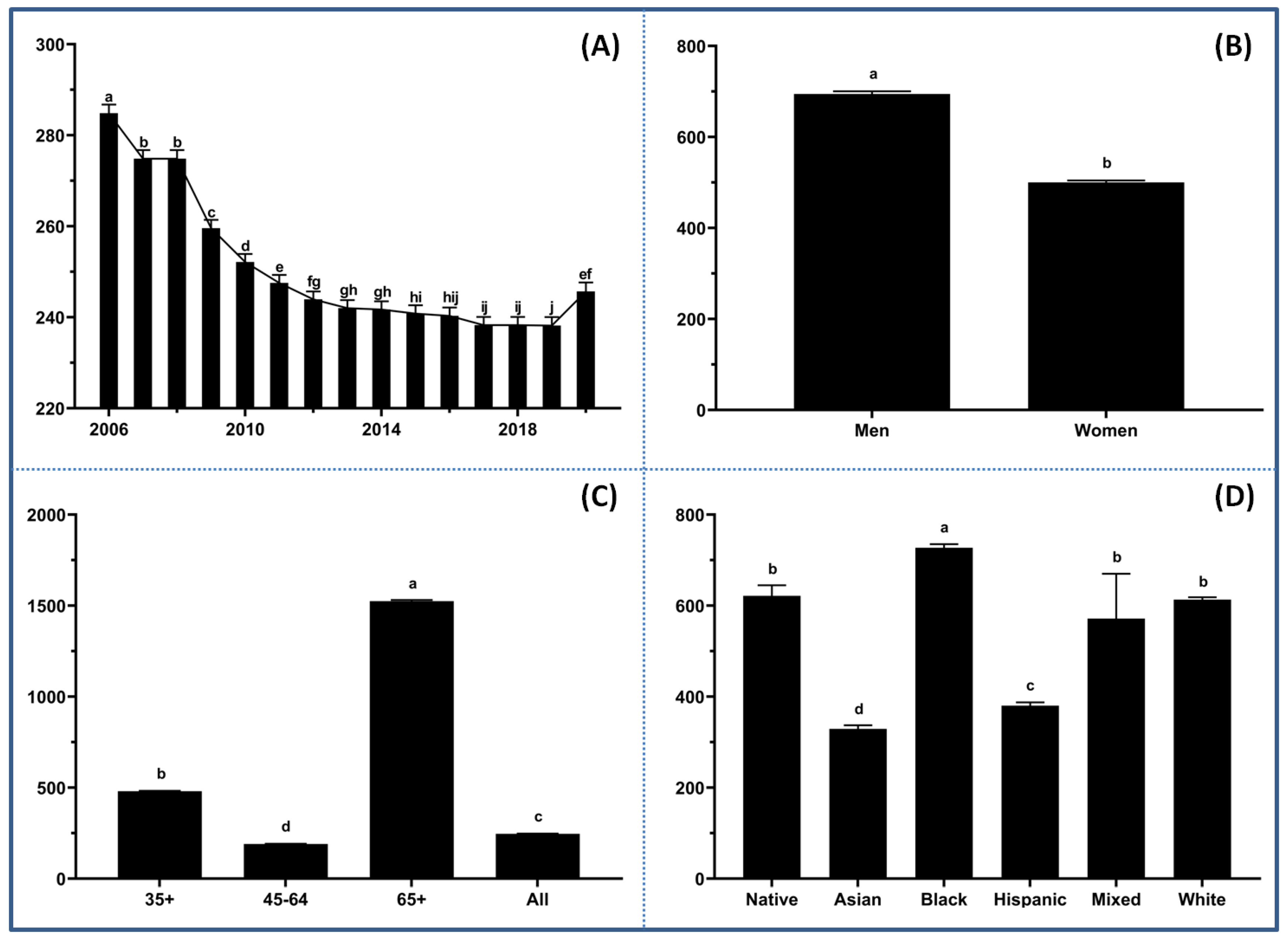

3.1. Demographic Disparities

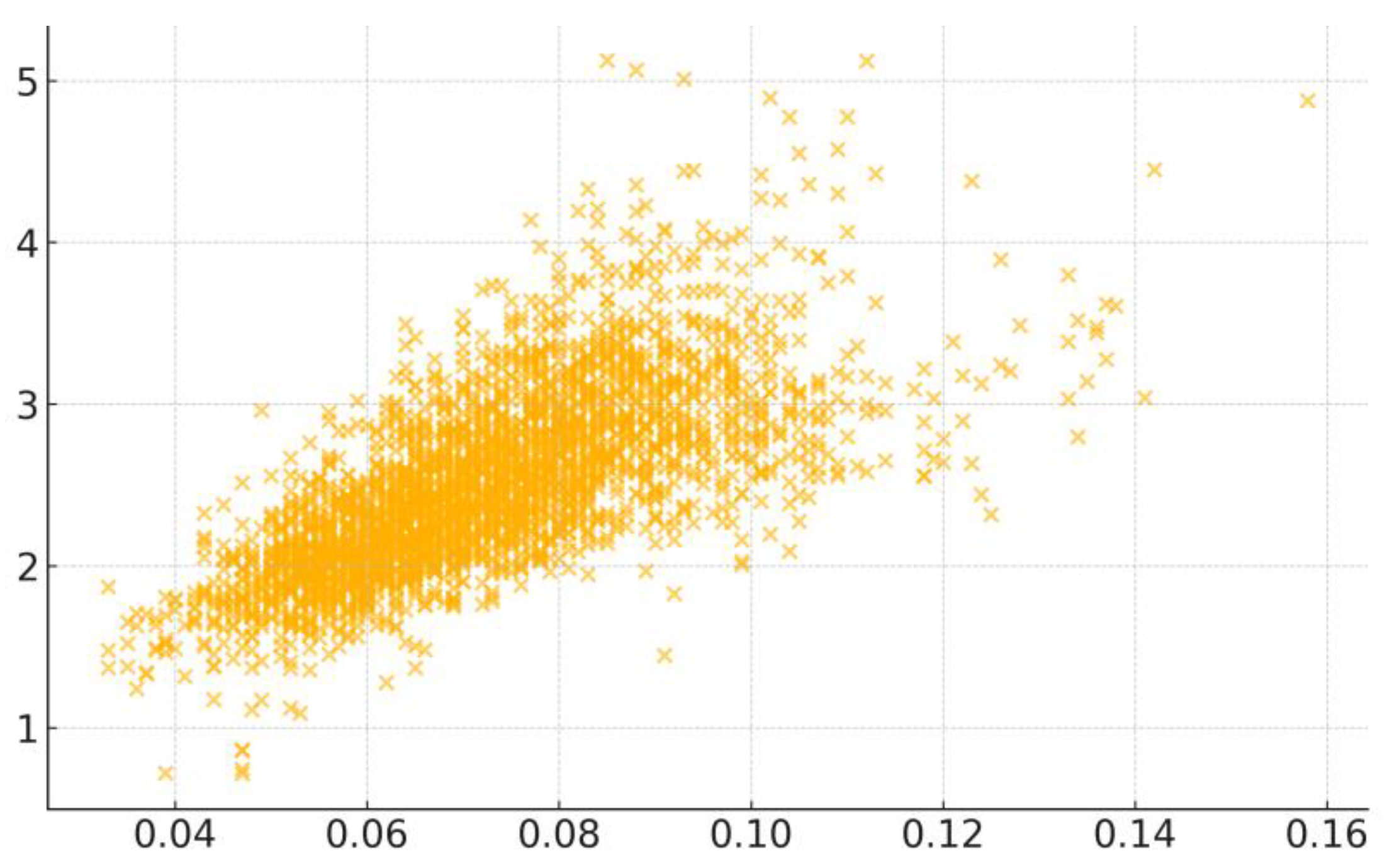

3.2. Key Correlation Factors

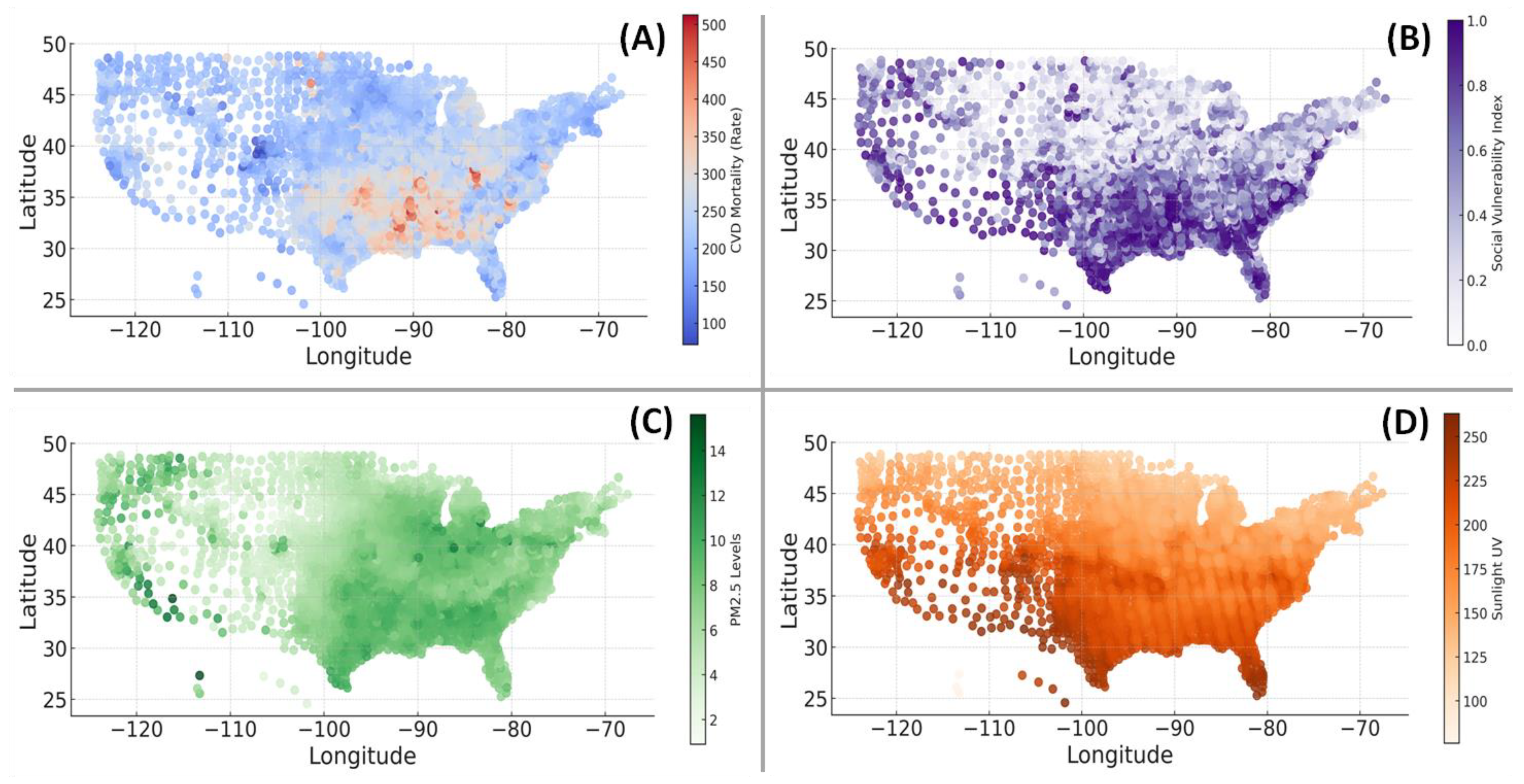

3.3. Geospatial Associations

3.4. Multiple Regression Modeling

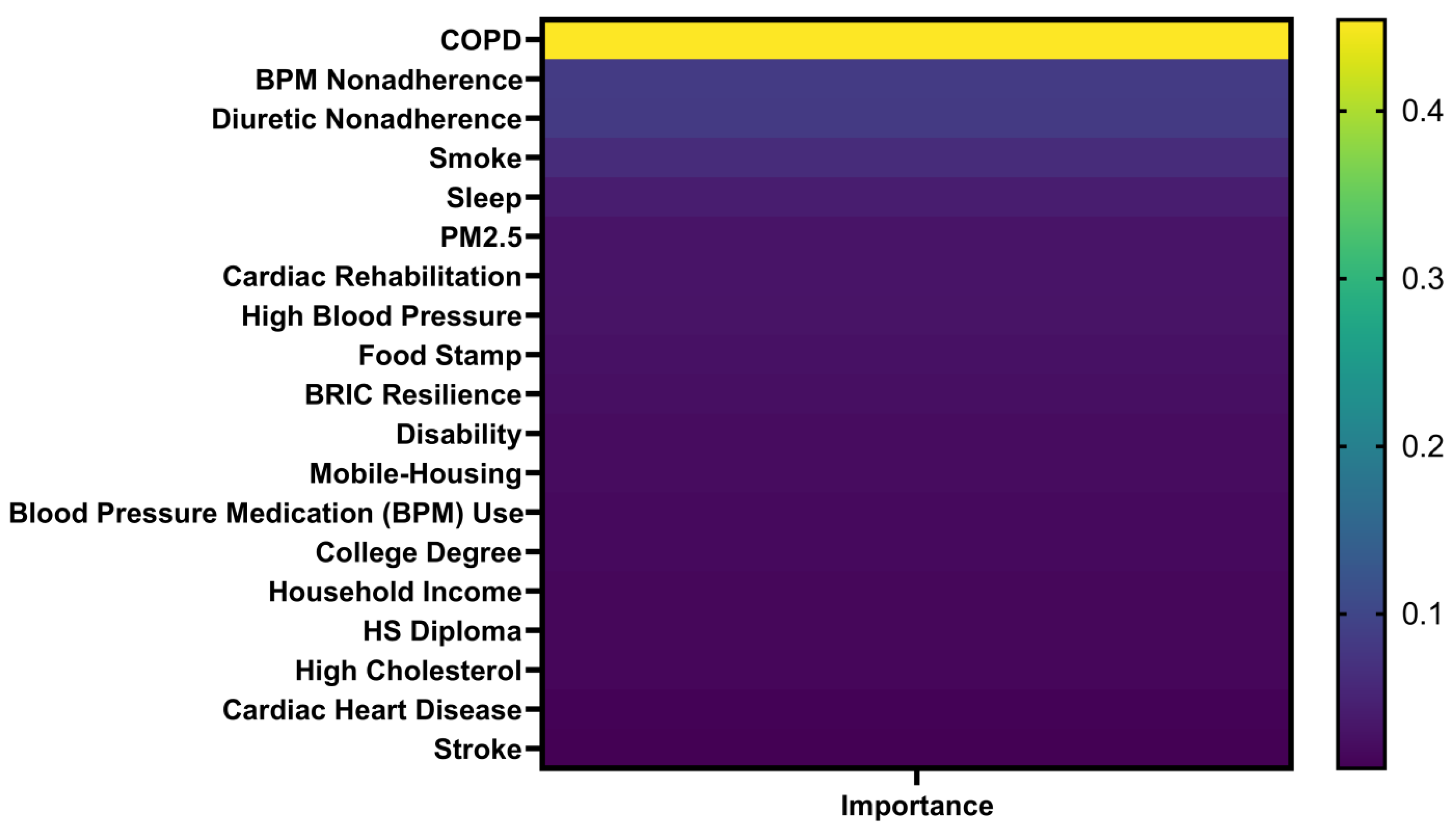

3.5. Machine Learning Prediction

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Addo, P.N.O., Mundagowa, P.T., Zhao, L., Kanyangarara, M., Brown, M.J., and Liu, J. (2024). Associations between sleep duration, sleep disturbance and cardiovascular disease biomarkers among adults in the United States. BMC Public Health 24, 947. [CrossRef]

- Adepu, S., Berman, A.E., and Thompson, M.A. (2020). Socioeconomic determinants of health and county-level variation in cardiovascular disease mortality: an exploratory analysis of Georgia during 2014-2016. Preventive Medicine Reports 19, 101160. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R., Yeh, R.W., Maddox, K.E.J., and Wadhera, R.K. (2023). Cardiovascular risk factor prevalence, treatment, and control in US adults aged 20 to 44 years, 2009 to March 2020. JAMA 329, 899-909. [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H. (2018). User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine 18, 91-93. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi, S.G., Brook, R.D., Biswal, S., and Rajagopalan, S. (2020). Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution. Nature Reviews Cardiology 17, 656-672. [CrossRef]

- Bakhit, M., Fien, S., Abukmail, E., Jones, M., Clark, J., Scott, A.M., Glasziou, P., and Cardona, M. (2024). Cardiovascular disease risk communication and prevention: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 45, 998-1013. [CrossRef]

- Baptista, E.A., and Queiroz, B.L. (2022). Spatial analysis of cardiovascular mortality and associated factors around the world. BMC Public Health 22, 1556. [CrossRef]

- Baran, C., Belgacem, S., Paillet, M., de Abreu, R.M., de Araujo, F.X., Meroni, R., and Corbellini, C. (2024). Active commuting as a factor of cardiovascular disease prevention: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 9, 125. [CrossRef]

- Barbera, M., Lehtisalo, J., Perera, D., Aspö, M., Cross, M., De Jager Loots, C.A., Falaschetti, E., Friel, N., Luchsinger, J.A., Gavelin, H.M., et al. (2024). A multimodal precision-prevention approach combining lifestyle intervention with metformin repurposing to prevent cognitive impairment and disability: the MET-FINGER randomised controlled trial protocol. Alzheimers Res Ther 16, 23. [CrossRef]

- Bevan, G., Pandey, A., Griggs, S., Dalton, J.E., Zidar, D., Patel, S., Khang, S.U., Nasir, K., Rajagopalan, S., and Al-Kindi, S. (2023). Neighborhood-level social vulnerability and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and coronary heart disease. Curr Probl Cardiol 48, 101182. [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, P., Borkowska, N., Mangeshkar, S., Adal, B.H., and Singh, N. (2024). Racial and socioeconomic determinants of cardiovascular health: a comprehensive review. Cureus Journal of Medical Science 16, e59497. [CrossRef]

- Cotton, A., Salerno, P., Deo, S., Virani, S., Nasir, K., Neeland, I., Rajagopalan, S., Sattar, N., Al-Kindi, S., and Elgudin, Y.E. (2024). The association between county-level premature cardiovascular mortality related to cardio-kidney-metabolic disease and the social determinants of health in the US. Sci Rep 14, 24984. [CrossRef]

- DuPont, J.J., Kenney, R.M., Patel, A.R., and Jaffe, I.Z. (2019). Sex differences in mechanisms of arterial stiffness. Br J Pharmacol 176, 4208-4225. [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, L.M., Celli, B.R., Agustí, A., Criner, G.J., Dransfield, M.T., Divo, M., Krishnan, J.K., Lahousse, L., de Oca, M.M., Salvi, S.S., et al. (2023). COPD and multimorbidity: recognising and addressing a syndemic occurrence. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 11, 1020-1034. [CrossRef]

- Henning, R.J. (2024). Particulate matter air pollution is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol 49, 102094. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.J., Yang, T., and Yang, Y.J. (2024). Causal associations of education level with cardiovascular diseases, cardiovascular biomarkers, and socioeconomic factors. Am J Cardiol 213, 76-85. [CrossRef]

- Kang, E., Cho, D., Lee, S., Im, J., Lee, D., and Yoo, C. (2024). An explainable AI framework for spatiotemporal risk factor analysis in public health: a case study of cardiovascular mortality in South Korea. GIScience & Remote Sensing 61, 2436997. [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C., Qadeer, Y.K., Hayes, R.B., Wang, Z., Virani, S., Thurston, G.D., and Lavie, C.J. (2023). PM2.5 and cardiovascular health risks. Curr Probl Cardiol 48, 101670. [CrossRef]

- Kundrick, J., Rollins, H., Mullachery, P., Sharaf, A., Schnake-Mahl, A., Roux, A.V.D., and Bilal, U. (2024). Heterogeneity in disparities by income in cardiovascular risk factors across 209 US metropolitan areas. Preventive Medicine Reports 47, 102908. [CrossRef]

- Lamas, G.A., Bhatnagar, A., Jones, M.R., Mann, K.K., Nasir, K., Tellez-Plaza, M., Ujueta, F., Navas-Acien, A., Group Author(s): American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, et al. (2023). Contaminant metals as cardiovascular risk factors: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association 12, e029852. [CrossRef]

- Maddox, K.E.J., Elkind, M.S., Aparicio, H.J., Commodore-Mensah, Y., de Ferranti, S.D., Dowd, W.N., Hernandez, A.F., Khavjou, O., Michos, E.D., Palaniappan, L., et al. (2024). Forecasting the burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke in the United States through 2050 - prevalence of risk factors and disease: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 150, e65-e88. [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, C., Ojeda, F.M., Leong, D.P., Alegre-Diaz, J., Amouyel, P., Aviles-Santa, L., De Bacquer, D., Ballantyne, C.M., Bernabé-Ortiz, A., Bobak, M., et al. (2023). Global effect of modifiable risk factors on cardiovascular disease and mortality. New England Journal of Medicine 389, 1273-1285. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S., Aday, A.W., Almarzooq, Z.I., Anderson, C.A., Arora, P., Avery, C.L., Baker-Smith, C.M., Barone Gibbs, B., Beaton, A.Z., Boehme, A.K., et al. (2024). 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 149, e347-e913. [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.M.K., Jain, V., Li, M., Ariss, R.W., Fudim, M., Michos, E.D., Virani, S.S., Sperling, L., and Mehta, A. (2023). Family income and cardiovascular disease risk in American adults. Sci Rep 13, 279. [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T., Molitor, M., Kuntic, M., Hahad, O., Röösli, M., Engelmann, N., Basner, M., Daiber, A., and Sørensen, M. (2024). Transportation noise pollution and cardiovascular health. Circulation Research 134, 1113-1135. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J., Pagidipati, N.J., and Bosworth, H.B. (2024). Improving medication adherence in cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 21, 396-416. [CrossRef]

- Neubeck, L., Lowres, N., Benjamin, E.J., Ben Freedman, S., Coorey, G., and Redfern, J. (2015). The mobile revolution-using smartphone apps to prevent cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 12, 350-360. [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.S., Dooley, E.E., Master, H., Spartano, N.L., Brittain, E.L., and Pettee Gabriel, K. (2023). Physical activity over the lifecourse and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research 132, 1725-1740. [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M., Poirier, P., Burke, L.E., Després, J.P., Gordon-Larsen, P., Lavie, C.J., Lear, S.A., Ndumele, C.E., Neeland, I.J., Sanders, P., et al. (2021). Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, E984-E1010. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J., Briesacher, B.A., Wallace, R.B., Kawachi, I., Baum, C.F., and Kim, D. (2019). County-level housing affordability in relation to risk factors for cardiovascular disease among middle-aged adults: The National Longitudinal Survey of Youths 1979. Health Place 59, 102194. [CrossRef]

- Roush, G.C., Kaur, R., and Ernst, M.E. (2014). Diuretics: a review and update. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 19, 5-13. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.N., Yao, J., Du, S.C., Qian, F., Appleton, A.A., Tao, C., Xu, H., Liu, L., Dai, Q., Joyce, B.T., et al. (2023). Social determinants, cardiovascular disease, and health care cost: a nationwide study in the United States using machine learning. Journal of the American Heart Association 12, e027919. [CrossRef]

- Tainio, M., Andersen, Z.J., Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J., Hu, L., de Nazelle, A., An, R.P., Garcia, L.M.T., Goenka, S., Zapata-Diomedi, B., Bull, F., et al. (2021). Air pollution, physical activity and health: a mapping review of the evidence. Environ Int 147, 105954. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S., Dalal, H.M., and McDonagh, S.T. (2022). The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Nature Reviews Cardiology 19, 180-194. [CrossRef]

- Toma, A., Paré, G., and Leong, D.P. (2017). Alcohol and cardiovascular disease: how much is too much? Current Atherosclerosis Reports 19, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S., Li, Z.X., Wang, X.Y., Guo, S., Sun, Y.J., Li, G.H., Zhao, C.H., Yuan, W.H., Li, M., Li, X.L., et al. (2022). Associations between sleep duration and cardiovascular diseases: a meta-review and meta-analysis of observational and Mendelian randomization studies. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 9, 930000. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, A., Hammad, M., Piña, I.L., and Kulinski, J. (2024). Obesity and cardiovascular health. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 31, 1026-1035. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, N.S., Amit, U., Reibel, J.B., Berlin, E., Howell, K., and Ky, B. (2024). Cardiovascular disease and cancer: shared risk factors and mechanisms. Nature Reviews Cardiology 21, 617-631. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Q., Mondal, D., and Polya, D.A. (2020). Positive association of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with chronic exposure to drinking water arsenic (As) at concentrations below the WHO provisional guideline value: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 2536. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Z., Xu, J.L., and Yang, X.J. (2017). Asthma and risk of cardiovascular disease or all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Ann Saudi Med 37, 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Zuma, B.Z., Parizo, J.T., Valencia, A., Spencer-Bonilla, G., Blum, M.R., Scheinker, D., and Rodriguez, F. (2021). County-level factors associated with cardiovascular mortality by race/ethnicity. Journal of the American Heart Association 10, e018835. [CrossRef]

| Factor | R | P | N | Factor | R | P | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD Prevalence | 0.700 | < 0.0001 | 3054 | Vehicle Crashes Involving People | 0.081 | < 0.0001 | 3121 |

| Current Smoker Status | 0.650 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Atrazine in Water | 0.075 | 0.276 | 214 |

| High Blood Pressure | 0.644 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Population per Neurologist | 0.073 | 0.018 | 1059 |

| Less Sleeping < 7 Hour | 0.644 | < 0.0001 | 3121 | Population per CVD Physician | 0.034 | 0.232 | 1212 |

| Population Living in Poverty | 0.591 | < 0.0001 | 3128 | Percent Cholesterol Screening | 0.028 | 0.126 | 3070 |

| Food Stamp Percentage | 0.547 | < 0.0001 | 3136 | Housing with More People than Rooms | 0.025 | 0.168 | 3122 |

| Stroke Prevalence | 0.540 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | TCE in Water | 0.014 | 0.840 | 208 |

| Socioeconomic Vulnerability | 0.534 | < 0.0001 | 3121 | Air Domain Index | 0.011 | 0.554 | 2769 |

| Population with Disability | 0.526 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Water Domain Index | 0.009 | 0.653 | 2769 |

| Adults No College Degree | 0.513 | < 0.0001 | 3200 | Sociodemographic Vulnerability | 0.007 | 0.695 | 2769 |

| Overall Vulnerability Rank | 0.481 | < 0.0001 | 3121 | Population 65+ | 0.004 | 0.825 | 2769 |

| Social Vulnerability | 0.478 | < 0.0001 | 3113 | Environmental Quality Index | 0.004 | 0.818 | 2769 |

| Single-parent Households | 0.478 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Group Quarters | 0.001 | 0.965 | 2769 |

| Asthma Prevalence | 0.470 | < 0.0001 | 3054 | More Units Housing | -0.000 | 0.993 | 2769 |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 0.439 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Half Income on Housing | -0.001 | 0.975 | 3134 |

| Diuretic Non-adherence | 0.428 | < 0.0001 | 3108 | Land Domain Index | -0.001 | 0.977 | 2769 |

| Diagnosed Diabetes | 0.417 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Community Capital Resilience | -0.003 | 0.881 | 3123 |

| Mobile Housing Units | 0.414 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Built Domain Index | -0.005 | 0.797 | 2769 |

| Post-Acute Care Cost | 0.411 | < 0.0001 | 3199 | Physical Annual | -0.009 | 0.625 | 2769 |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation Eligibility | 0.401 | < 0.0001 | 3044 | Population 19- | -0.016 | 0.395 | 2769 |

| Blood Pressure Medication NA | 0.397 | < 0.0001 | 3161 | House Built 1980B | -0.013 | 0.452 | 3122 |

| DEHP in Water | 0.396 | < 0.0001 | 123 | Environmental Resilience Score | -0.029 | 0.103 | 3123 |

| Household Composition Disability | 0.395 | < 0.0001 | 3121 | Less English Speaker | -0.030 | 0.119 | 2769 |

| Renin Angiotensin Antagonist NA | 0.393 | < 0.0001 | 3147 | Land for Development - Open Space | -0.037 | 0.039 | 3095 |

| High Cholesterol Prevalence | 0.388 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Land Covered by Water | -0.048 | 0.008 | 3095 |

| Air Quality PM2.5 | 0.383 | < 0.0001 | 3118 | Uranium in Water | -0.056 | 0.335 | 301 |

| Leisure-time Physical Inactivity | 0.379 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Land for Development - L Intensity | -0.065 | 0.000 | 3095 |

| Incremental Post-Acute Care Cost | 0.374 | < 0.0001 | 3199 | Public Transportation to Work | -0.066 | 0.000 | 3113 |

| Population without HS Diploma | 0.345 | < 0.0001 | 3200 | Radium in Water | -0.069 | 0.067 | 700 |

| Family without Internet | 0.339 | < 0.0001 | 3205 | Land for Development - H Intensity | -0.079 | < 0.0001 | 3095 |

| Blood Pressure Medication Use | 0.307 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Cancer Prevalence | -0.082 | < 0.0001 | 3054 |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation Completion | 0.283 | < 0.0001 | 1322 | Land used for Agriculture - Crop | -0.085 | < 0.0001 | 3095 |

| Total Care Cost | 0.282 | < 0.0001 | 3199 | Population per Neurosurgeon | -0.089 | 0.021 | 669 |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation Completion | 0.283 | < 0.0001 | 1322 | Hospitals with Cardiac Intensive Care | -0.090 | < 0.0001 | 3209 |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation Sessions | 0.277 | < 0.0001 | 3100 | PCE in Water | -0.091 | 0.177 | 221 |

| Sunlight and UV | 0.277 | < 0.0001 | 3200 | Developed Imperviousness | -0.097 | < 0.0001 | 3095 |

| Family without Computer | 0.268 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Number of Hospitals | -0.104 | < 0.0001 | 3209 |

| House Built 1950A1980B | 0.260 | < 0.0001 | 3199 | Walking to Work | -0.105 | < 0.0001 | 3113 |

| Incremental Total Care Cost | 0.258 | < 0.0001 | 3121 | Economic Resilience Score | -0.108 | < 0.0001 | 3123 |

| Housing-Transportation Rank | 0.251 | < 0.0001 | 3136 | Land for Development - M Intensity | -0.113 | < 0.0001 | 3095 |

| Cholesterol Medication NA | 0.230 | < 0.0001 | 3120 | Hospitals with ER | -0.115 | < 0.0001 | 3209 |

| Population without Health Insurance | 0.228 | < 0.0001 | 2988 | Health Device Reliant Populations | -0.120 | < 0.0001 | 3122 |

| Drug Poisoning Death Rate | 0.225 | < 0.0001 | 2974 | Hospitals with Neurological Services | -0.123 | < 0.0001 | 3209 |

| Population per Primary Care Physician | 0.225 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Nitrates in Water | -0.128 | < 0.0001 | 1440 |

| Household without Vehicle | 0.219 | < 0.0001 | 3137 | Driving to Work | -0.137 | < 0.0001 | 3113 |

| Urban-Rural Status | 0.187 | < 0.0001 | 3210 | Incremental Outpatient Care Cost | -0.140 | < 0.0001 | 3199 |

| Number of Pharmacies & Drug Store | 0.186 | < 0.0001 | 1446 | Hospitals with Cardiac Rehabilitation | -0.144 | < 0.0001 | 3209 |

| Disinfection H in Water | 0.175 | < 0.0001 | 3199 | Outpatient Care Cost | -0.156 | < 0.0001 | 3199 |

| Inpatient Care Cost | 0.174 | < 0.0001 | 3095 | Arsenic in Water | -0.168 | < 0.0001 | 770 |

| Land used for Agriculture - Pasture | 0.166 | < 0.0001 | 3112 | Working from Home | -0.180 | < 0.0001 | 3113 |

| Time Driving to Work | 0.166 | < 0.0001 | 3200 | House Built 1950B | -0.188 | < 0.0001 | 3122 |

| Income Inequality Gini Index | 0.156 | < 0.0001 | 1519 | Households with Smartphone | -0.298 | < 0.0001 | 3113 |

| Disinfection T in Water | 0.146 | < 0.0001 | 3199 | Radon Levels | -0.298 | < 0.0001 | 805 |

| Incremental Inpatient Care Cost | 0.141 | < 0.0001 | 3123 | BRIC Resilience | -0.331 | < 0.0001 | 3123 |

| Institutional Resilience Score | 0.132 | < 0.0001 | 3123 | Park Access Percent | -0.336 | < 0.0001 | 3137 |

| Minority Status Rank | 0.132 | < 0.0001 | 3121 | Housing-Infrastructural Resilience | -0.413 | < 0.0001 | 3123 |

| Unemployment Rate | 0.120 | < 0.0001 | 3207 | Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation | -0.413 | < 0.0001 | 2399 |

| Vehicle Crashes Involving No People | 0.102 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Median Home Value | -0.453 | <0.0001 | 3197 |

| Percent of Land Covered by Forest | 0.102 | < 0.0001 | 3095 | Alcohol Use | -0.509 | < 0.0001 | 3054 |

| Obesity | 0.090 | < 0.0001 | 3070 | Social Resilience | -0.533 | < 0.0001 | 3123 |

| Renter-occupied Housing Units | 0.088 | < 0.0001 | 3122 | Median Household Income | -0.590 | < 0.0001 | 3128 |

| Coefficient Term | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | P-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | -0.018 | 0.234 | -0.08 | 0.94 | |

| Single-parent Households | 0.593 | 0.219 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 3.03 |

| Disability | 0.434 | 0.210 | 2.07 | 0.039 | 2.73 |

| Mobile-home Housing | -0.512 | 0.0975 | -5.25 | 0 | 2.29 |

| Alcohol Use | -0.826 | 0.359 | -2.30 | 0.021 | 2.53 |

| Blood Pressure Medication Use | 1.23 | 0.256 | 4.79 | 0 | 1.93 |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation Eligibility | 1.07 | 0.129 | 8.31 | 0 | 1.31 |

| Diabetes | 1.01 | 0.496 | 2.03 | 0.042 | 1.65 |

| Food Stamp | 0.364 | 0.164 | 2.22 | 0.026 | 3.59 |

| Median Household Income | -0.458 | 0.0707 | -6.47 | 0 | 3.77 |

| No College Degree | 0.301 | 0.115 | 2.61 | 0.009 | 3.78 |

| No High School Diploma | -1.06 | 0.177 | -5.97 | 0 | 2.70 |

| Air Quality PM2.5 | 4.72 | 0.423 | 11.15 | 0 | 1.41 |

| Park Access | -0.0722 | 0.0289 | -2.50 | 0.012 | 1.65 |

| Less Sleeping < 7 H | 0.931 | 0.287 | 3.25 | 0.001 | 3.09 |

| Post-Acute Care Cost | 0.0186 | 0.00507 | 3.66 | 0 | 1.43 |

| Blood Pressure Medication Non-adherence | 0.0886 | 0.00642 | 13.79 | 0 | 3.28 |

| Smoking Status | 4.48 | 0.308 | 14.55 | 0 | 3.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).