Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate the prevalence, hospitalization rates, and mortality among patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and comorbidities one year after the lifting of pandemic measures in Mexico. Methods. Clinical data from an open national public health database were divided into two timeframes: pandemic (2020–2022) and post-pandemic (May 2023–May 2024), following the removal of COVID-19 countermeasures. Entries were categorized by age group and the presence of specific comorbidities, including hypertension (HT), diabetes (DIAB), obesity (OBES), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), asthma (AA), smoking (SMOKE), and COVID-19, as well as recorded deaths. Binary regression analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of these comorbidities on the type of care provided (hospitalization or ambulatory care) and their role as potential mortality predictors. Results. Approximately seven out of ten CVD patients were aged 50 years or older. In the year following the pandemic, the rates of cases and hospitalizations increased, while death rates decreased. Additionally, the prevalence of comorbidities rose among all CVD patients. Although, obesity was not a significant predictor of hospitalization in either period. Hypertension, diabetes, obesity, asthma, and COVID-19 were not associated with mortality in the post-pandemic period. Conclusion One year after the lifting of COVID-19 measures, cases, hospitalizations, and comorbidities among CVD patients increased, while mortality declined. Obesity was no longer a key determinant of care type, and HT, DIAB, OBES, AA, and COVID-19 ceased to predict mortality. The post-pandemic rise in HT and DIAB cases likely results from both the physiological effects of infection and indirect factors like lifestyle changes and healthcare disruptions. Notably, while hospitalizations have increased, mortality has noticeably decreased, likely due to vaccination efforts, reduced viral virulence, and diminished fear of COVID-19.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Description of Data Collection Methods

Frequencies by Comorbidity Per Sampled Period

Binary Logistic Regression Analysis

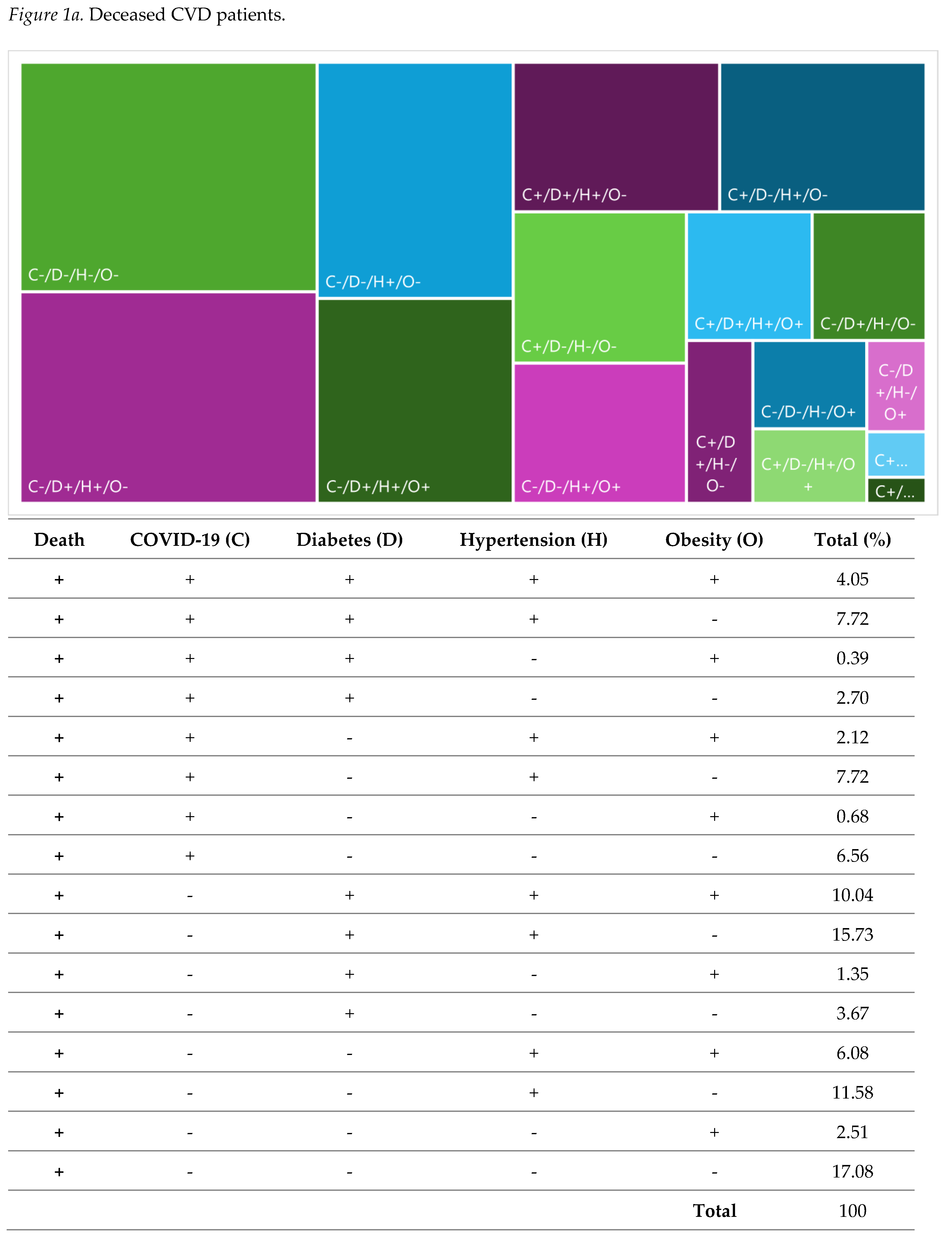

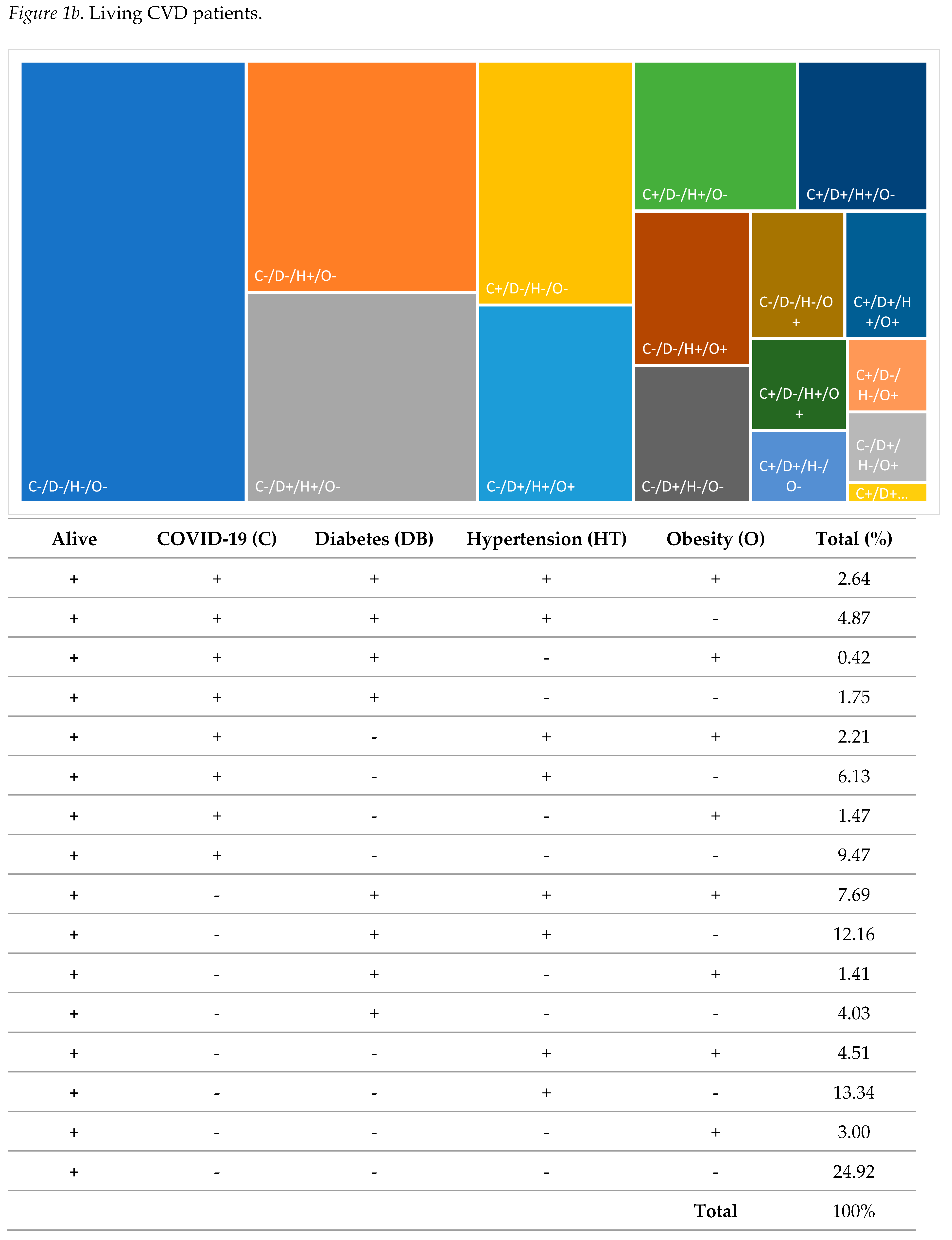

Results

Discussions

Aging

Hypertension and Diabetes

Obesity

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

COPD, Smoking and Asthma

COVID-19

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical approval Statement

References

- INEGI ESTADÍSTICAS DE DEFUNCIONES REGISTRADAS (EDR) 2020; 2021.

- INEGI ESTADÍSTICAS DE DEFUNCIONES REGISTRADAS (EDR) 2021; 2022.

- INEGI ESTADÍSTICAS DE DEFUNCIONES REGISTRADAS (EDR) 2022; 2023.

- INEGI ESTADÍSTICAS DE DEFUNCIONES REGISTRADAS (EDR) 2023 (PRELIMINAR); 2024.

- Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Delgado-Gallegos, J.L.; Garza-Treviño, G.; Galan-Huerta, K.A.; G-Buentello, Z.; Roacho-Pérez, J.A.; Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Franco-Villareal, H.; Leyva-Lopez, A.; Estrada-Rodriguez, A.E.; et al. Association between Mortality and Cardiovascular Diseases in the Vulnerable Mexican Population: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Erener, S. Diabetes, Infection Risk and COVID-19. Mol Metab 2020, 39, 101044. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; She, Z.-G.; Cheng, X.; Qin, J.-J.; Zhang, X.-J.; Cai, J.; Lei, F.; Wang, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Association of Blood Glucose Control and Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19 and Pre-Existing Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab 2020, 31, 1068-1077.e3. [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A.; Santos García-Gallego, C.; Bertomeu-González, V.; Fácila, L.; Rodríguez-Mañero, M.; Escribano, D.; Castellano, J.M.; Zuazola, P.; Núñez, J.; Badimón, J.J.; et al. Mortality Associated with Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with COVID-19. REC: CardioClinics 2021, 56, 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.M.; Vikse, J.; Benoit, S.; Favaloro, E.J.; Lippi, G. Hyperinflammation and Derangement of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in COVID-19: A Novel Hypothesis for Clinically Suspected Hypercoagulopathy and Microvascular Immunothrombosis. Clinica Chimica Acta 2020, 507, 167–173. [CrossRef]

- Pouvreau, C.; Dayre, A.; Butkowski, E.G.; De Jong, B.; Jelinek, H.F. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Markers in Diabetes and Hypertension. J Inflamm Res 2018, 11, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México México Pone Fin a La Emergencia Sanitaria Por COVID-19: Secretaría de Salud Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/mexico-pone-fin-a-la-emergencia-sanitaria-por-covid-19-secretaria-de-salud (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Poy, L.; Martinez, F. Vacunarán a 3 Millones de Maestros Del 20 de Abril al 28 de Mayo: AMLO. La Jornada 2021.

- Secretaría de Salud 24.ENE.2023 CONTINÚA SEDESA CON VACUNACIÓN CONTRA COVID-19 A MENORES DE 5 A 11 AÑOS Available online: https://www.salud.cdmx.gob.mx/boletines/24ene2023-continua-sedesa-con-vacunacion-contra-covid-19-menores-de-5-11-anos (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Dirección General de Epidemiología Datos Abiertos Bases Históricas Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/datos-abiertos-bases-historicas-direccion-general-de-epidemiologia (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Congreso de la Unión Ley General de Protección de Datos Personales En Posesión de Sujetos Obligados; Cámara de Diputados: Mexico City, 2017; pp. 1–52;

- Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Benitez-Chao, D.F.; Galan-Huerta, K.; Villareal, H.F.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Islas, J.F. A Panoramic View of Hospitalized Young Children in the Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico during COVID-19. IJID Regions 2023, 9, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Luis Delgado-Gallegos, J.; Garza-Treviño, G.; Galan-Huerta, K.A.; G-Buentello, Z.; Roacho-Pérez, J.A.; Giovana Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Franco-Villareal, H.; Leyva-Lopez, A.; Estrada-Rodriguez, A.E.; et al. Association between Mortality and Cardiovascular Diseases in the Vulnerable Mexican Population: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health, 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Chao, D.F.; García-Hernández, M.; Cuellar, J.M.; García, G.; Islas, J.F.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Padilla-Rivas, G.R. Impact of Comorbidities on COVID-19 Mortality in Hospitalized Women: Insights from the Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico from 2020 to 2022. IJID Regions 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Delgado-Gallegos, J.L.; Garza-Treviño, G.; Galan-Huerta, K.A.; G-Buentello, Z.; Roacho-Pérez, J.A.; Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Franco-Villareal, H.; Leyva-Lopez, A.; Estrada-Rodriguez, A.E.; et al. Association between Mortality and Cardiovascular Diseases in the Vulnerable Mexican Population: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- INEGI ENCUESTA NACIONAL SOBRE SALUD Y ENVEJECIMIENTO EN MÉXICO (ENASEM) Y ENCUESTA DE EVALUACIÓN COGNITIVA 2021; 2021.

- Rodgers, J.L.; Jones, J.; Bolleddu, S.I.; Vanthenapalli, S.; Rodgers, L.E.; Shah, K.; Karia, K.; Panguluri, S.K. Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Gender and Aging. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, D.J.; Goldstein, D.R. Ageing and Atherosclerosis: Vascular Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors and Potential Role of IL-6. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021, 18, 58–68. [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.B.; Siegart, N.M.; De Leon, J. Interleukin-6 in Atherosclerosis: Atherogenic or Atheroprotective? Clin Lipidol 2017, 12, 14–23.

- Rolski, F.; Błyszczuk, P. Complexity of TNF-α Signaling in Heart Disease. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 3267. [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammation in Atherosclerosis—No Longer a Theory. Clin Chem 2021, 67, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.O.; Mahoney, S.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Seals, D.R.; Clayton, Z.S. Aging, Aerobic Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health: Barriers, Alternative Strategies and Future Directions. Exp Gerontol 2023, 173. [CrossRef]

- Angeli, F.; Zappa, M.; Verdecchia, P. Global Burden of New-Onset Hypertension Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. Eur J Intern Med 2024, 119, 31–33. [CrossRef]

- Six, I.; Guillaume, N.; Jacob, V.; Mentaverri, R.; Kamel, S.; Boullier, A.; Slama, M. The Endothelium and COVID-19: An Increasingly Clear Link Brief Title: Endotheliopathy in COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Trimarco, V.; Izzo, R.; Pacella, D.; Trama, U.; Manzi, M.V.; Lombardi, A.; Piccinocchi, R.; Gallo, P.; Esposito, G.; Piccinocchi, G.; et al. Incidence of New-Onset Hypertension before, during, and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A 7-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study in a Large Population. BMC Med 2024, 22. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, C.; Peng, J.; Li, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Hu, A.; Peng, M.; Huang, K.; Fan, D. COVID-19 Induces New-Onset Insulin Resistance and Lipid Metabolic Dysregulation via Regulation of Secreted Metabolic Factors. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 427. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-T.; Lidsky, P.V.; Xiao, Y.; Lee, I.T.; Cheng, R.; Nakayama, T.; Jiang, S.; Demeter, J.; Bevacqua, R.J.; Chang, C.A. SARS-CoV-2 Infects Human Pancreatic β Cells and Elicits β Cell Impairment. Cell Metab 2021, 33, 1565–1576. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. Who 2021, 1–5.

- Our World in Data Residential Areas: How Did the Time Spent at Home Change since the Beginning of the Pandemic? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/changes-residential-duration-covid?tab=table (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Colín-Avilés, M.; Delgado-Jacobo, D.P. El Peso Corporal Durante El Confinamiento Por COVID-19. Psic-Obesidad 2024, Vol. 13 Núm. 52.

- Gianotti, L.; Belcastro, S.; D’Agnano, S.; Tassone, F. The Stress Axis in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus: An Update. Endocrines 2021, 2, 334–347. [CrossRef]

- Nour, T.Y.; Altintaş, K.H. Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Obesity and It Is Risk Factors: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Sánchez, F.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Torres-Álvarez, R.; Carnalla-Cortés, M.; Reyes-García, A.; Swinburn, B.; Meza, R.; Rivera, J.A.; Popkin, B.; Barientos-Gutiérrez, T. Caloric Reductions Needed to Achieve Obesity Goals in Mexico for 2030 and 2040: A Modeling Study. PLoS Med 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, D.; Brotons, C.; Moral, I.; Bulc, M.; Afonso, M.; Akan, H.; Pinto, S.; Vucak, J.; Da Silva Martins, C.M. Lifestyle Behaviours in Patients with Established Cardiovascular Diseases: A European Observational Study. BMC Fam Pract 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Canada, J.M.; Billingsley, H.E.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Elagizi, A.; Lavie, C.J. Obesity Paradox in Cardiovascular Disease: Where Do We Stand? Vasc Health Risk Manag 2019, 15, 89–100. [CrossRef]

- Tutor, A.W.; Lavie, C.J.; Kachur, S.; Milani, R.V.; Ventura, H.O. Updates on Obesity and the Obesity Paradox in Cardiovascular Diseases. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2023, 78, 2–10. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.P.; Selter, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Rathore, S.S.; Sokol, S.I.; Bader, F.; Krumholz, H.M. The Obesity Paradox Body Mass Index and Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure.

- Ortega, F.B.; Sui, X.; Lavie, C.J.; Blair, S.N. Body Mass Index, the Most Widely Used but Also Widely Criticized Index Would a Criterion Standard Measure of Total Body Fat Be a Better Predictor of Cardiovascular Disease Mortality? Mayo Clin Proc 2016, 91, 443–455. [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, E984–E1010. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.R.; Aeddula, N.R. Chronic Kidney Disease; StatPearls Publishing: Florida, 2024.

- Schiffl, H.; Lang, S.M. Long-Term Interplay between COVID-19 and Chronic Kidney Disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2023, 55, 1977–1984. [CrossRef]

- Atiquzzaman, M.; Thompson, J.R.; Shao, S.; Djurdjev, O.; Bevilacqua, M.; Wong, M.M.Y.; Levin, A.; Birks, P.C. Long-Term Effect of COVID-19 Infection on Kidney Function among COVID-19 Patients Followed in Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinics in British Columbia, Canada. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023, 38, 2816–2825. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S. Reanalyzing the Impact of COVID-19 on the Kidneys Available online: https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-kidneys/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Schmidt-Lauber, C.; Hänzelmann, S.; Schunk, S.; Petersen, E.L.; Alabdo, A.; Lindenmeyer, M.; Hausmann, F.; Kuta, P.; Renné, T.; Twerenbold, R.; et al. Kidney Outcome after Mild to Moderate COVID-19. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2023, 38, 2031–2040. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-García, J.; Granados-García, V.; Hernández-Rivera, J.C.H.; Lagunes-Cisneros, M.; Alvarado-Gutiérrez, T.; Paniagua-Sierra, J.R. Evolution of the Stage of Chronic Kidney Disease from the Diagnosis of Hypertension in Primary Care. Aten Primaria 2022, 54. [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, L.; Balafa, O.; Dounousi, E.; Ekart, R.; Fernandez Fernandez, B.; Mark, P.B.; Sarafidis, P.; Valdivielso, J.M.; Ferro, C.J.; Mallamaci, F. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2024, 39, 177–189. [CrossRef]

- UCSF Institute for Global Health Sciences Mexico’s Response to COVID-19: A Case Study; 2021.

- Schrauben, S.J.; Chen, H.Y.; Lin, E.; Jepson, C.; Yang, W.; Scialla, J.J.; Fischer, M.J.; Lash, J.P.; Fink, J.C.; Hamm, L.L.; et al. Hospitalizations among Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States: A Cohort Study. PLoS Med 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas, A.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N. SARS-CoV-2 Intermittent Virulence as a Result of Natural Selection. COVID 2022, 2, 1089–1101. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Gebo, K.A.; Abraham, A.G.; Habtehyimer, F.; Patel, E.U.; Laeyendecker, O.; Gniadek, T.J.; Fernandez, R.E.; Baker, O.R.; Ram, M.; et al. Dynamics of Inflammatory Responses after SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Vaccination Status in the USA: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e692–e703. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Liu, J.; Geng, L.; Zhong, Z.; Tan, J.; Wen, D.; Zhou, L.; Tang, Y.; Qin, W. The Influences of COVID-19 on Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D.; Zakeri, R.; Quint, J.K. Defining the Relationship between COPD and CVD: What Are the Implications for Clinical Practice? Ther Adv Respir Dis 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Madouros, N.; Jarvis, S.; Saleem, A.; Koumadoraki, E.; Sharif, S.; Khan, S. Is There an Association Between Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Chronic Renal Failure? Cureus 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Hanania, N.A.; Rogliani, P.; Matera, M.G. Cardiovascular Disease in Asthma Patients: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Kardiol Pol 2023, 81, 232–241. [CrossRef]

- Pollevick, M.E.; Xu, K.Y.; Mhango, G.; Federmann, E.G.; Vedanthan, R.; Busse, P.; Holguin, F.; Federman, A.D.; Wisnivesky, J.P. The Relationship Between Asthma and Cardiovascular Disease: An Examination of the Framingham Offspring Study. Chest 2021, 159, 1338–1345. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.G.; Kwon, M.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Hwang, Y. Il; Jang, S.H. Association between Asthma and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Longitudinal Follow-up Study Using a National Health Screening Cohort. World Allergy Organization Journal 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Assaf, S.; Stenberg, H.; Jesenak, M.; Tarasevych, S.P.; Hanania, N.A.; Diamant, Z. Asthma in the Era of COVID-19. Respir Med 2023, 218. [CrossRef]

- SSA 034. En México, 83.3 Millones de Personas Vacunadas Contra COVID-19 Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/034-en-mexico-83-3-millones-de-personas-vacunadas-contra-covid-19?idiom=es (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Jarquin, C.; Quezada, L.F.; Gobern, L.; Balsells, E.; Rondy, M. Early Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Older Populations in Four Countries of the Americas, 2021. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica/Pan American Journal of Public Health 2023, 47. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A. 86% de Los Mexicanos Sí Cree En La Utilidad de Los Cubrebocas Para Prevenir El COVID-19 Available online: 86% de los mexicanos sí cree en la utilidad de los cubrebocas para prevenir el COVID-19 (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Kitroeff, N.; Villegas, P. ‘I’d Rather Stay Home and Die’ Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/10/world/americas/mexico-coronavirus-hospitals.html?auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Doubova, S.V.; Leslie, H.H.; Kruk, M.E.; Pérez-Cuevas, R.; Arsenault, C. Disruption in Essential Health Services in Mexico during COVID-19: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Health Information System Data. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.S.; Moscone, A.; McElrath, E.E.; Varshney, A.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Bhatt, D.L.; Januzzi, J.L.; Butler, J.; Adler, D.S.; Solomon, S.D.; et al. Fewer Hospitalizations for Acute Cardiovascular Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 280–288. [CrossRef]

- SEGOB Acuerdo Por El Que Se Establecen Las Medidas Preventivas Que Se Deberán Implementar Para La Mitigación y Control de Los Riesgos Para La Salud Que Implica La Enfermedad Por El Virus SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19). Diario Oficial de la Federación 2020.

- Mendoza, J. Number of Hospital Beds in Mexico from 2012 to 2021 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/287092/number-of-hospital-beds-in-mexico/ (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Muñoz Martínez, R. Risk, Covid-19 and Hospital Care in Mexico City: Are We Moving toward a New Medical Practice? Nóesis. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 2022, 31, 26–46. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.I.; Flores-Ceron, K.I.; Muñoz-Pérez, V.M. Self-Medication Practice in Mexico. Sr Care Pharm 2022, 37, 266–283. [CrossRef]

- Torres Soto, N.Y.; López Franco, G.; Torres Soto, N.A.; Aray Roa, A.; Monzalvo Curiel, A.; Peña Torres, E.F.; Rojas Armadillo, M. de L. Risk Perception about the Covid-19 Pandemic and Its Effect on Self-Medication Practices in Population of Northwestern Mexico. Acta Univ 2022, 32, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- PBS News Hour Culture of Avoiding the Doctor Intensifies Health Concerns in Mexico Available online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/health-jan-june09-mexicoselfmed_05-05 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Mendez-Luck, C.A.; Amorim, C.; Anthony, K.P.; Neal, M.B. Beliefs and Expectations of Family and Nursing Home Care among Mexican-Origin Caregivers. J Women Aging 2017, 29, 460–472. [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; De Neve, J.-E.; Aknin, L.B.; Wang, S. World Happiness Report 2022; 2022.

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; De Neve, J.-E.; Aknin, L.B.; Wang, S. World Happiness Report 2024; 2024.

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 8,363 | 52.0 |

| Male | 7,726 | 48.0 |

| Age groups | ||

| 0 – 17 | 1,382 | 8.6 |

| 18 – 30 | 796 | 4.9 |

| 31 – 40 | 927 | 5.8 |

| 41 – 50 | 1,523 | 9.5 |

| 51 – 60 | 2,508 | 15.6 |

| 61 – 70 | 3,169 | 19.7 |

| 71 – 80 | 3,164 | 19.7 |

| >80 | 2,602 | 16.2 |

| Type of medical attention | ||

| Ambulatory | 8,763 | 54.5 |

| Hospitalized | 7,326 | 45.5 |

| COVID-19 | ||

| Positive | 4,690 | 29.2 |

| Negative | 11,399 | 70.8 |

| Hypertension | ||

| Yes | 8,735 | 54.3 |

| No | 7,354 | 45.7 |

| Diabetic | ||

| Yes | 5,735 | 35.6 |

| No | 10,354 | 64.4 |

| Obesity | ||

| Yes | 3,796 | 23.6 |

| No | 12,293 | 76.4 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | ||

| Yes | 1,958 | 12.2 |

| No | 14,131 | 87.8 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | ||

| Yes | 1,950 | 12.1 |

| No | 14,139 | 87.9 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 1,801 | 11.2 |

| No | 14,288 | 88.8 |

| Asthma | ||

| Yes | 758 | 4.7 |

| No | 15,331 | 95.3 |

| Death | ||

| Yes | 1,036 | 6.4 |

| No | 15,053 | 93.6 |

| Comorbidity | Period | %Yes | %No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 2020-2022 | 19,404 (46.3%) | 22,477 (53.7%) |

| 2023-2024 | 8,735 (54.3%) | 7,354 (45.7%) | |

| Diabetes | 2020-2022 | 11,878 (28.4%) | 30,003 (71.6%) |

| 2023-2024 | 5,735 (35.6%) | 10,354 (64.4%) | |

| Obesity | 2020-2022 | 9,611 (22.9%) | 32,270 (77.1%) |

| 2023-2024 | 3,796 (23.6%) | 12,293 (76.4%) | |

| CKD | 2020-2022 | 3,411 (8.1%) | 38,471 (91.9%) |

| 2023-2024 | 1,950 (12.1%) | 14,139 (87.9%) | |

| COPD | 2020-2022 | 2,808 (6.7%) | 39,074 (93.3%) |

| 2023-2024 | 1,958 (12.2%) | 14,131 (87.8%) | |

| Smoking | 2020-2022 | 5,806 (13.9%) | 36,076 (86.1%) |

| 2023-2024 | 1,801 (11.2%) | 14,288 (88.8%) | |

| Asthma | 2020-2022 | 1,961 (4.7%) | 39,921 (95.3%) |

| 2023-2024 | 758 (4.7%) | 15,331 (95.3%) | |

| COVID-19 | 2020-2022 | 15,363 (36.7%) | 26,518 (63.3%) |

| 2023-2024 | 4,690 (29.2%) | 11,399 (70.8%) | |

| Deaths | 2020-2022 | 3,637 (8.7%) | 38,244 (91.3%) |

| 2023-2024 | 1,036 (6.4%) | 15,053 (93.6%) |

| Comorbidity | Period | Care Type | %Yes | %No | Chi-Squared P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 5,784 (59.2%) | 3,990 (40.8%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 13,621 (42.4%) | 18,487 (57.6%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 4,257 (58.1%) | 3,069 (41.9%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 4,478 (51.1%) | 4,285 (48.9%) | |||

| Diabetes | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 3,933 (40.2%) | 5,841 (59.8%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 7,946 (24.7%) | 24,162 (75.3%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 2,897 (39.5%) | 4,429 (60.5%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 2,838 (32.4%) | 5,925 (67.6%) | |||

| Obesity | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 2,306 (23.6%) | 7,468 (76.4%) | 0.086 |

| Ambulatory | 7,306 (22.8%) | 24,802 (77.2%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 1,716 (23.4%) | 5,610 (76.6%) | 0.654 | |

| Ambulatory | 2,080 (23.7%) | 6,683 (76.3%) | |||

| CKD | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 1,491 (15.3%) | 8,283 (84.7%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 1,920 (6.0%) | 30,188 (94.0%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 1,168 (16.4%) | 6,128 (83.6%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 752 (8.6%) | 8011 (91.4%) | |||

| COPD | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 992 (10.1%) | 8,782 (89.9%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 1,816 (5.7%) | 30,292 (94.3%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 1,210 (16.5%) | 6,116 (83.5%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 748 (8.5%) | 8,015 (91.5%) | |||

| Smoking | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 1,520 (15.6%) | 8,254 (84.4%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 4,286 (13.3%) | 27,822 (86.7%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 953 (13.0%) | 6,373 (87.0%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 848 (9.7%) | 7,915 (90.3%) | |||

| Asthma | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 231 (2.4%) | 9,543 (97.6%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 1,730 (5.4%) | 30,378 (94.6%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 260 (3.5%) | 7,066 (96.5%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 498 (5.7%) | 8,265 (94.3%) | |||

| COVID-19 | 2020-2022 | Hospitalized | 4,777 (48.9%) | 4,997 (51.5%) | 0.000 |

| Ambulatory | 10,586 (33.0%) | 21,522 (67.0%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | Hospitalized | 1,451 (19.8%) | 5,875 (80.2%) | 0.000 | |

| Ambulatory | 3,239 (37.0%) | 5,524 (63.0%) |

| Comorbidity | Period | Condition | %Death (No) | %Death (Yes) | Chi-Squared P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 2020-2022 | No | 21,339 (55.8%) | 16,906 (44.2%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 1,138 (31.3%) | 2,499 (68.7%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 6,916 (45.9%) | 8,137 (54.1%) | 0.022 | |

| Yes | 438 (42.3%) | 598 (57.7%) | |||

| Diabetes | 2020-2022 | No | 28,063 (73.4%) | 10,182 (26.6%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 1,940 (53.3%) | 1,697 (46.7%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 9,705 (64.5%) | 5,348 (35.5%) | 0.240 | |

| Yes | 649 (62.6%) | 387 (37.4%) | |||

| Obesity | 2020-2022 | No | 29,620 (77.4%) | 8,625 (22.6%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 2,650 (72.9%) | 987 (27.1%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 11,519 (76.5%) | 3,534 (23.0%) | 0.185 | |

| Yes | 774 (74.7%) | 262 (25.3%) | |||

| CKD | 2020-2022 | No | 35,473 (92.2%) | 2,998 (7.8%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 2,772 (81.3%) | 639 (18.7%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 13,304 (94.1%) | 835 (5.9%) | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 1,749 (89.7%) | 201 (10.3%) | |||

| COPD | 2020-2022 | No | 35,907 (91.9%) | 3,167 (8.1%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 2338 (83.3%) | 470 (16.7%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 13,324 (94.3%) | 807 (5.7%) | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 1,729 (88.3%) | 229 (11.7%) | |||

| Smoking | 2020-2022 | No | 33,087 (91.7%) | 2,989 (8.3%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 5,158 (88.8%) | 648 (11.2%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 13,409 (93.8%) | 879 (6.2%) | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 1,644 (91.3%) | 157 (8.7%) | |||

| Asthma | 2020-2022 | No | 36,373 (91.1%) | 3,548 (8.9%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 1,872 (95.5%) | 89 (4.5%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 14,331 (93.5%) | 1,000 (6.5%) | 0.061 | |

| Yes | 722 (95.3%) | 36 (4.7%) | |||

| COVID-19 | 2020-2022 | No | 25,423 (95.9%) | 1,096 (4.1%) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 12,822 (83.5%) | 2,541 (16.5%) | |||

| 2023-2024 | No | 10,694 (93.8%) | 705 (6.2%) | 0.043 | |

| Yes | 4,359 (92.9%) | 331 (7.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).