Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Transforming Curved Path into Geodesic for Dust

2.2. Rotational Energy

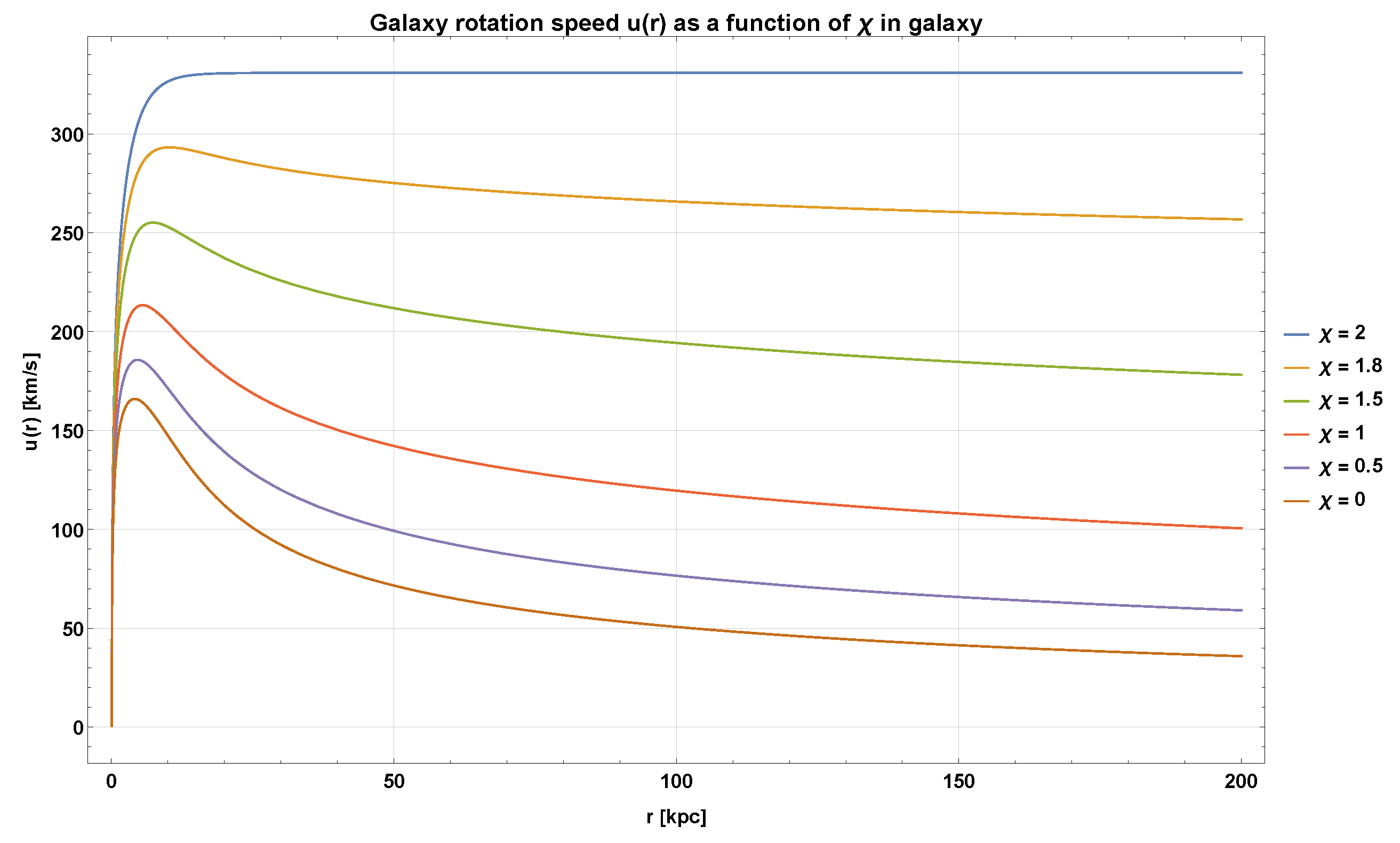

2.3. The Halo Effect

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

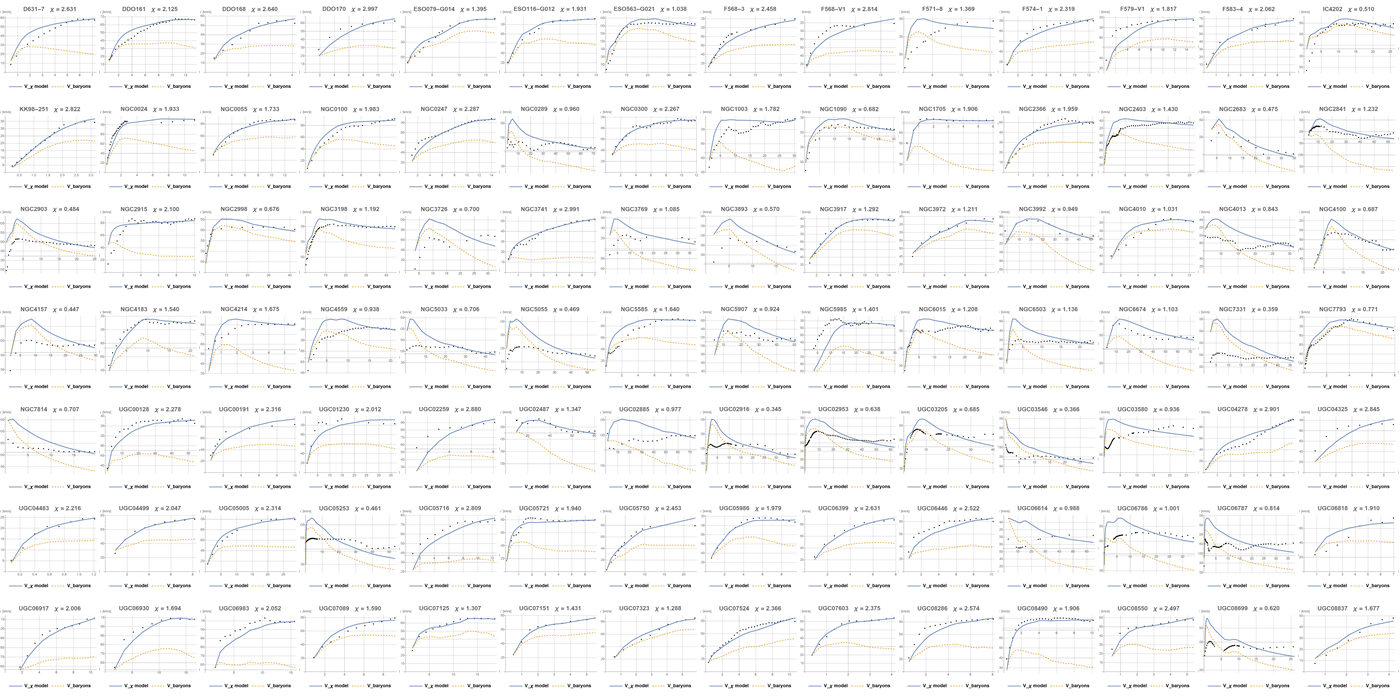

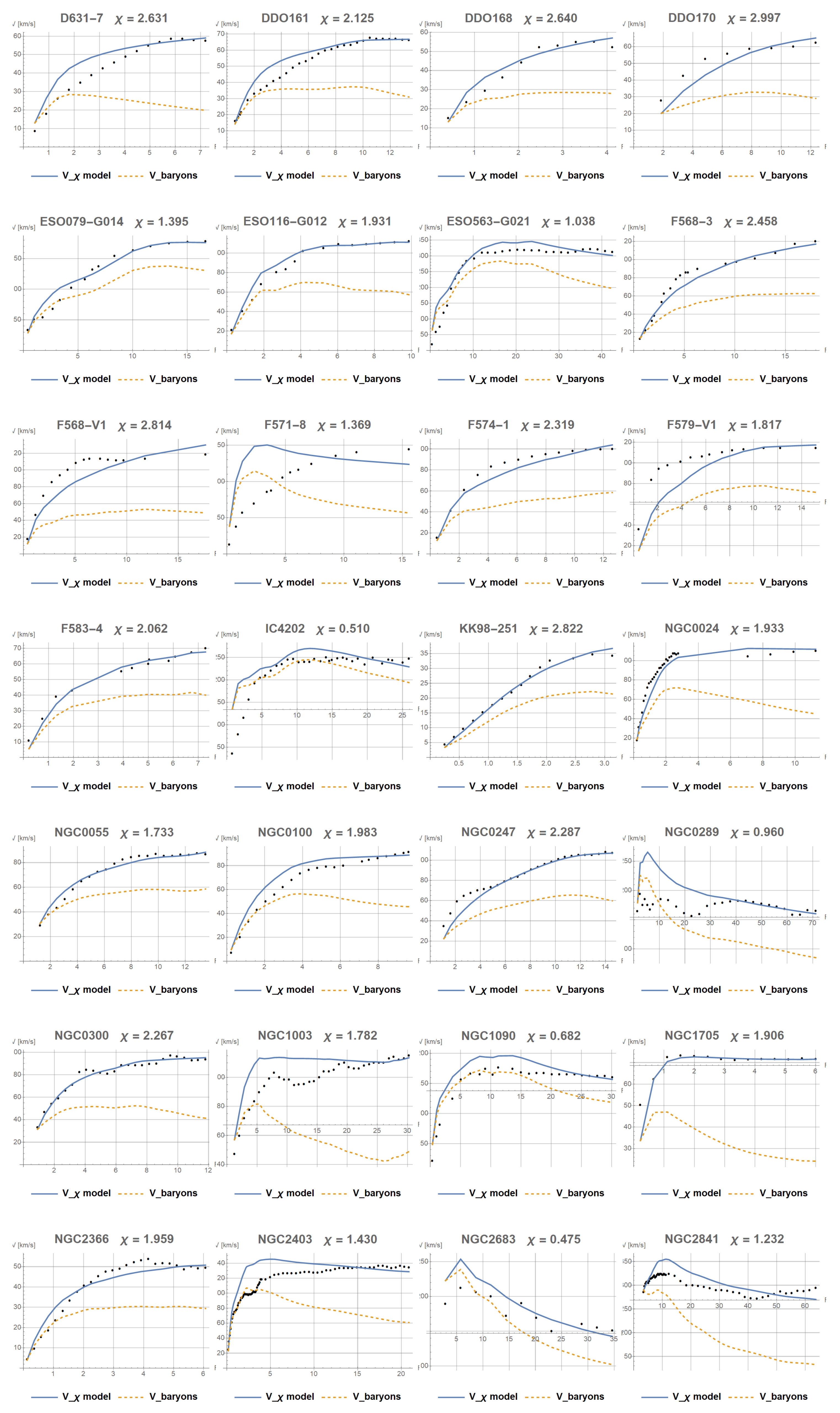

Appendix A. Results of Fitting the Constant χ

References

- Abdalla, E.; Marins, A. The dark sector cosmology. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2020, 29, 2030014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, V.; Rosenfeld, R.; Sturani, R. Observing the dark sector. Universe 2019, 5, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, J.; et al. Direct detection of dark matter - APPEC committee report. Reports on Progress in Physics 2022, 85, 056201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerib, D.S.; et al. Projected WIMP sensitivity of the LUX-ZEPLIN dark matter experiment. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 052002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, T.; et al. Search for a Dark-Matter-Induced Cosmic Axion Background with ADMX. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, D.; et al. Constraints on dark matter self-interaction from the internal density profiles of X-COP galaxy clusters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2022, 666, A41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, A.; Pisacane, G.; Quaranta, A.; Romeo, F. Probing mirror neutrons and dark matter through cold neutron interferometry. Physics of the Dark Universe 2024, 46, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, E.; et al. First Search for Light Dark Matter in the Neutrino Fog with XENONnT. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 111802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, R.; et al. First Dark Matter Constraints from a SuperCDMS Single-Charge Sensitive Detector. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamionkowski, M.; Riess, A.G. The Hubble Tension and Early Dark Energy. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 2023, 73, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordis, C.; Złośnik, T. New Relativistic Theory for Modified Newtonian Dynamics. Physical Review Letters 2021, 127, 161302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, Y.; Collaboration), O.N. Search for Light Dark Matter with NA64 at CERN. Physical Review Letters 2023, 131, 161801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, M. Testing general relativity in cosmology. Living Reviews in Relativity 2019, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchordoqui, L.A.; Antoniadis, I.; Lüst, D.; Castillo, K.P. Through the looking glass into the dark dimension: Searching for bulk black hole dark matter with microlensing of X-ray pulsars. Physics of the Dark Universe 2024, 46, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, M.; et al. First test of Verlinde’s theory of emergent gravity using weak gravitational lensing measurements. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2017, 466, 2547–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, E.; et al. First Dark Matter Search Results from the XENON1T Experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 181301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, J. Dark Matter Superfluidity. SciPost Physics Lecture Notes 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddy, J.; et al. A comparison of the baryonic Tully-Fisher relation in MaNGA and SPARC. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2023, 520, 3895–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucca, M. Dark energy-dark matter interactions as a solution to the S8 tension. Physics of the Dark Universe 2021, 34, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brout, D.; Collaboration), O.P. The Pantheon+ Analysis: Cosmological Constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodha, K.; et al. DESI 2024: Constraints on physics-focused aspects of dark energy using DESI DR1 BAO data. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 023532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuillandre, J.C.; Collaboration), O.E. Euclid: Early Release Observations - Programme overview and data products. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2025, 686, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Proposed method of combining continuum mechanics with Einstein Field Equations. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2023, 2350010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Developed method: interactions and their quantum picture. Frontiers in Physics 2023, 11, 1264925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Gravitational waves and Higgs-like potential from Alena Tensor. Physica Scripta 2025, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P.; Skindzier, P. Alena Tensor in unification applications. Physica Scripta 2024, 100, 015018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, F.; McGaugh, S.S.; Schombert, J.M. SPARC: Mass Models for 175 Disk Galaxies with Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curves. The Astronomical Journal 2016, 152, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forger, M.; Römer, H. Currents and the energy-momentum tensor in classical field theory: a fresh look at an old problem. Annals of Physics 2004, 309, 306–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, D.N.; Gieres, F.; Reboud, M.; Schweda, M. The energy-momentum tensor(s) in classical gauge theories. Nuclear Physics B 2016, 912, 192–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelmann, M.; Schneider, P. Weak gravitational lensing. Reports on Progress in Physics 2001, 64, 691–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al., T.E.C. Strong Gravitational Lensing as a Probe of Dark Matter. Space Science Reviews 2024, 220, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoni, M.; Sanna, A.P.; Tuveri, M. Anisotropic fluid cosmology: an alternative to dark matter? Physical Review D 2020, 102, 023514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoni, M.; Casadio, R. Effective fluid description of the dark universe. Physics Letters B 2018, 776, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al., B.D. Anisotropic strong lensing as a probe of dark matter self-interaction. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2023, 526, 5455–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al., D.P. Dark matter fluid constraints from galaxy rotation curves. European Physical Journal C 2023, 83, 11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, C. A geometric alternative to dark matter. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.08920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, K.; Matsuyama, T.; Asano, Y.; Tanda, S. Flat rotation curves in Chern-Simons modified gravity. Physical Review D 2008, 78, 024037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasin, H.; Grumiller, D. Non-Newtonian behavior in weak field general relativity for extended rotating sources. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2008, 17, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, W.E.; Hashim, M.; Nashed, G.G.L. Revisiting flat rotation curves in Chern-Simons modified gravity. Physics Letters B 2024, 856, 138882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrand, S. A machian model as potential alternative to dark matter halo thesis in galactic rotational velocity prediction. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 2024, 11, 1429235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaviva, G.; et al. Simple-graduated dark energy and spatial curvature. Physical Review D 2021, 104, 023505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchert, T.; Räsänen, S. Backreaction in Late-Time Cosmology. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 2012, 62, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaver, M.; Assunção, A.K.T.; Moraes, P.H.R.S. Realistic anisotropic neutron stars: Pressure effects. Physical Review D 2024, 109, 043025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.L.; Das, H. Spherically symmetric anisotropic strange stars. The European Physical Journal C 2024, 84, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brax, P.; Fichet, S. Scalar-mediated quantum forces between macroscopic bodies and interferometry. Physics of the Dark Universe 2023, 42, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).