Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

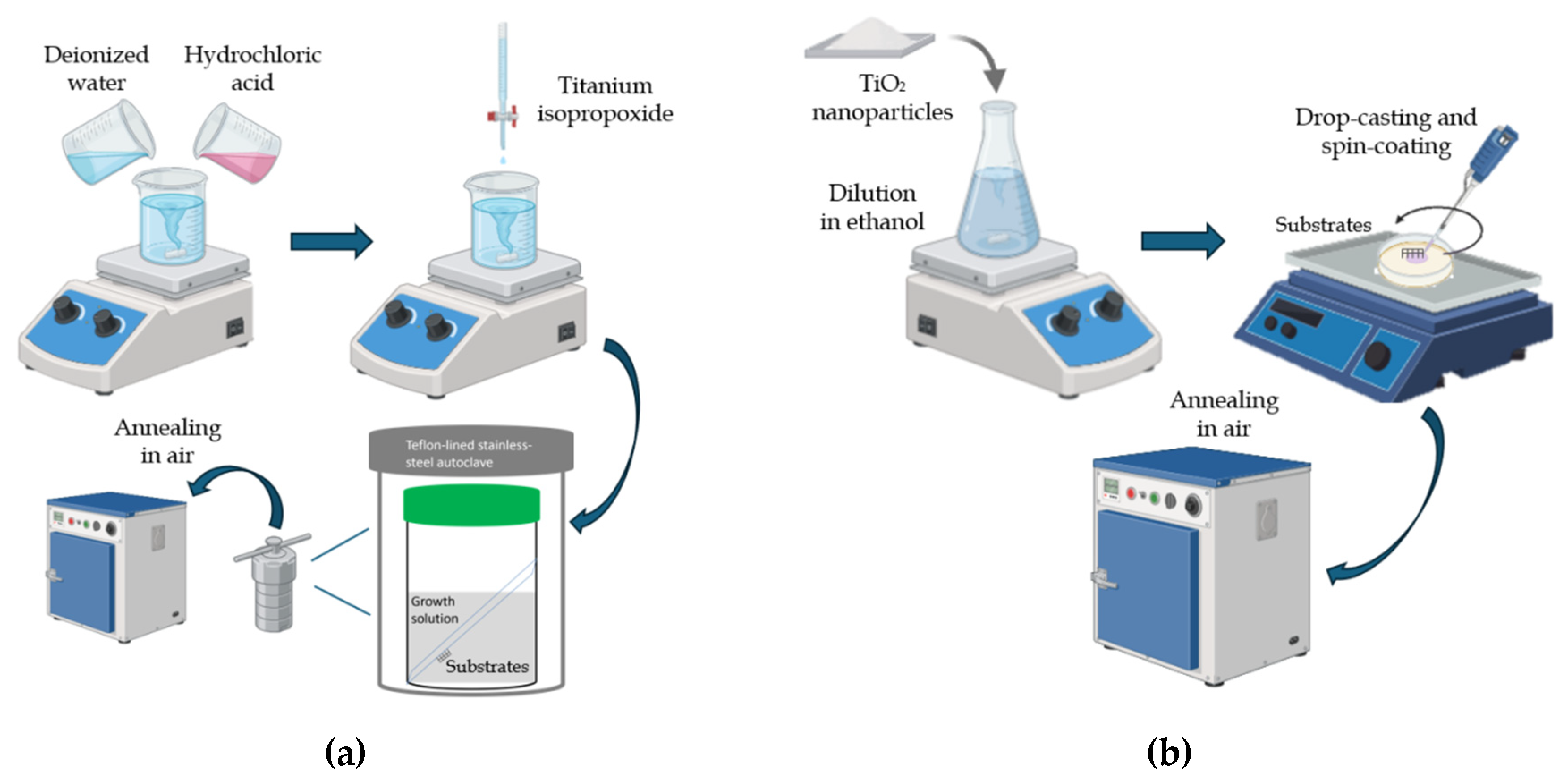

2.1. Oxides Synthesis and Characterization

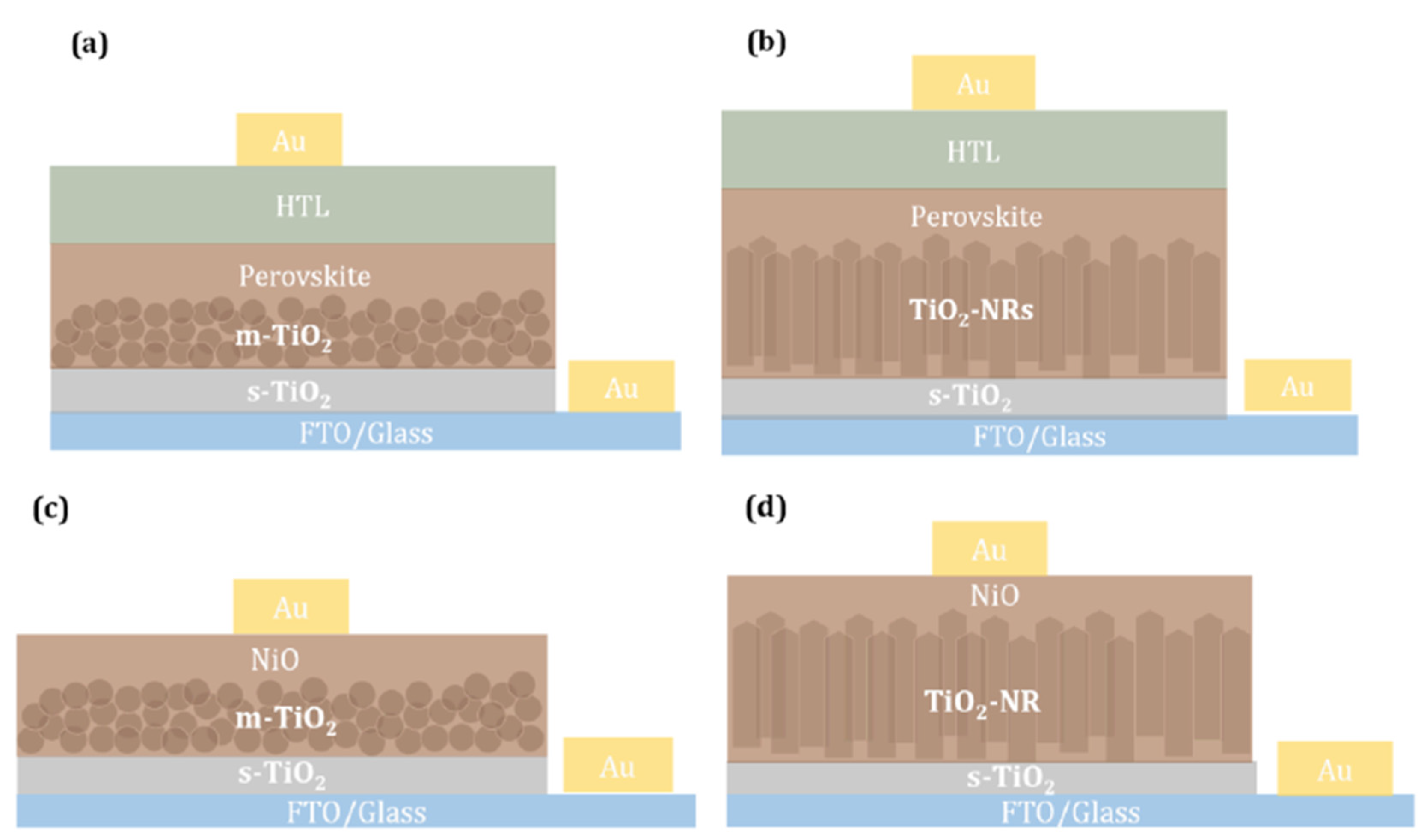

2.2. Fabrication and Characterization of Devices

3. Results and Discussion

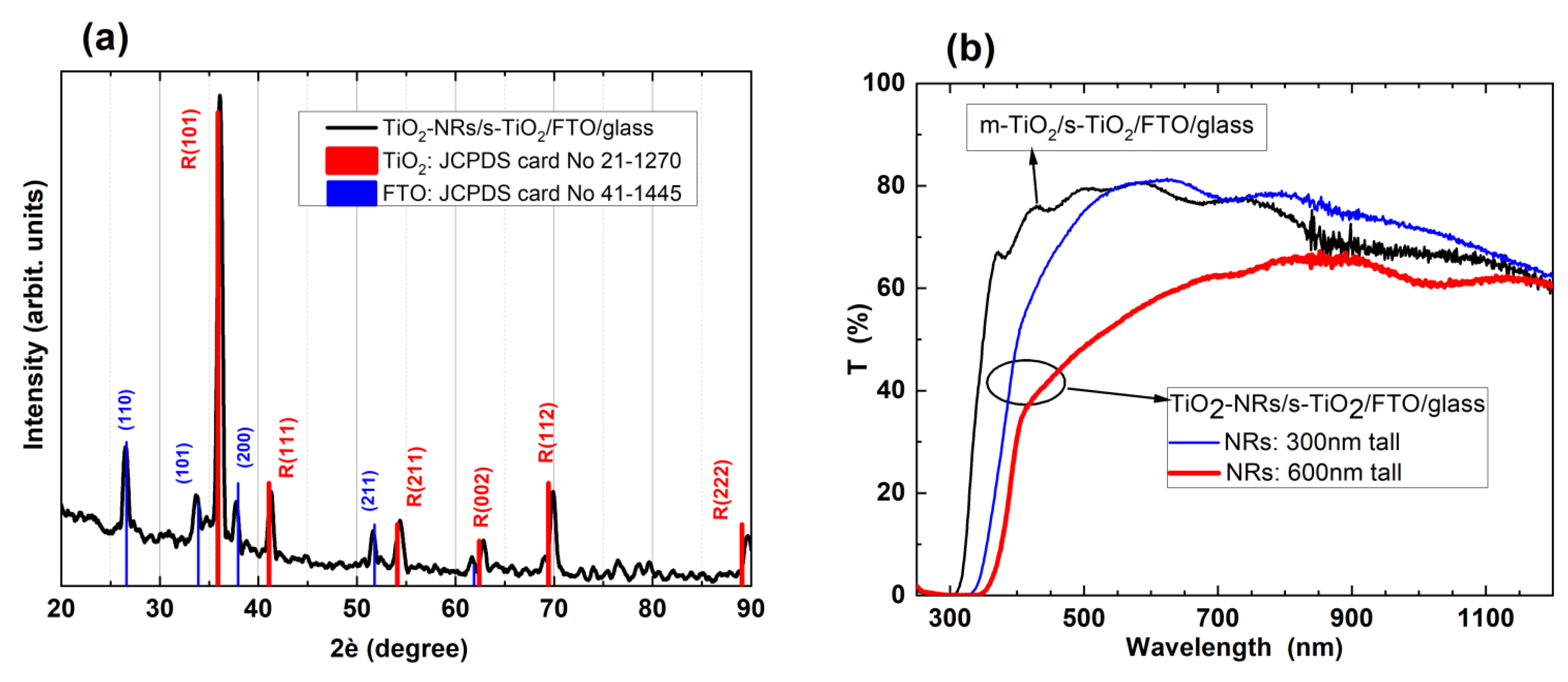

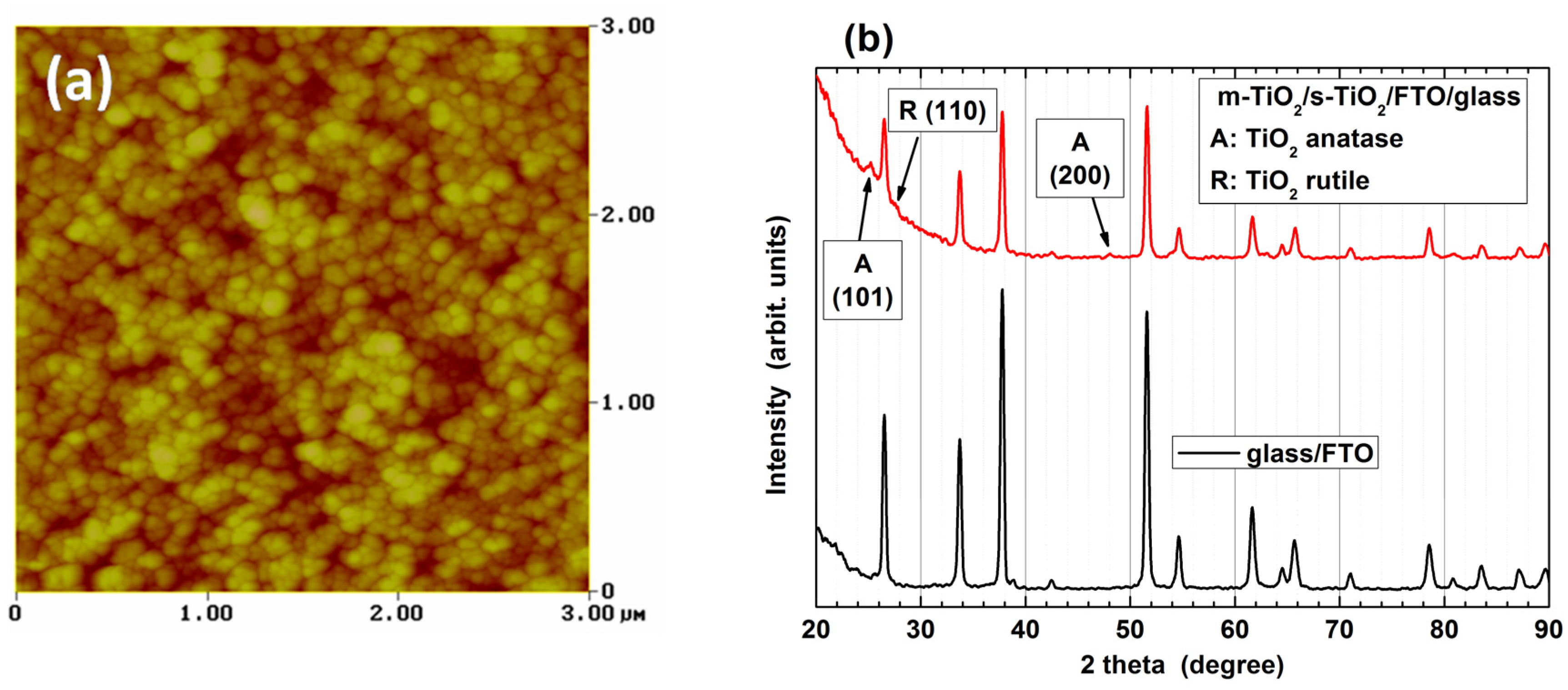

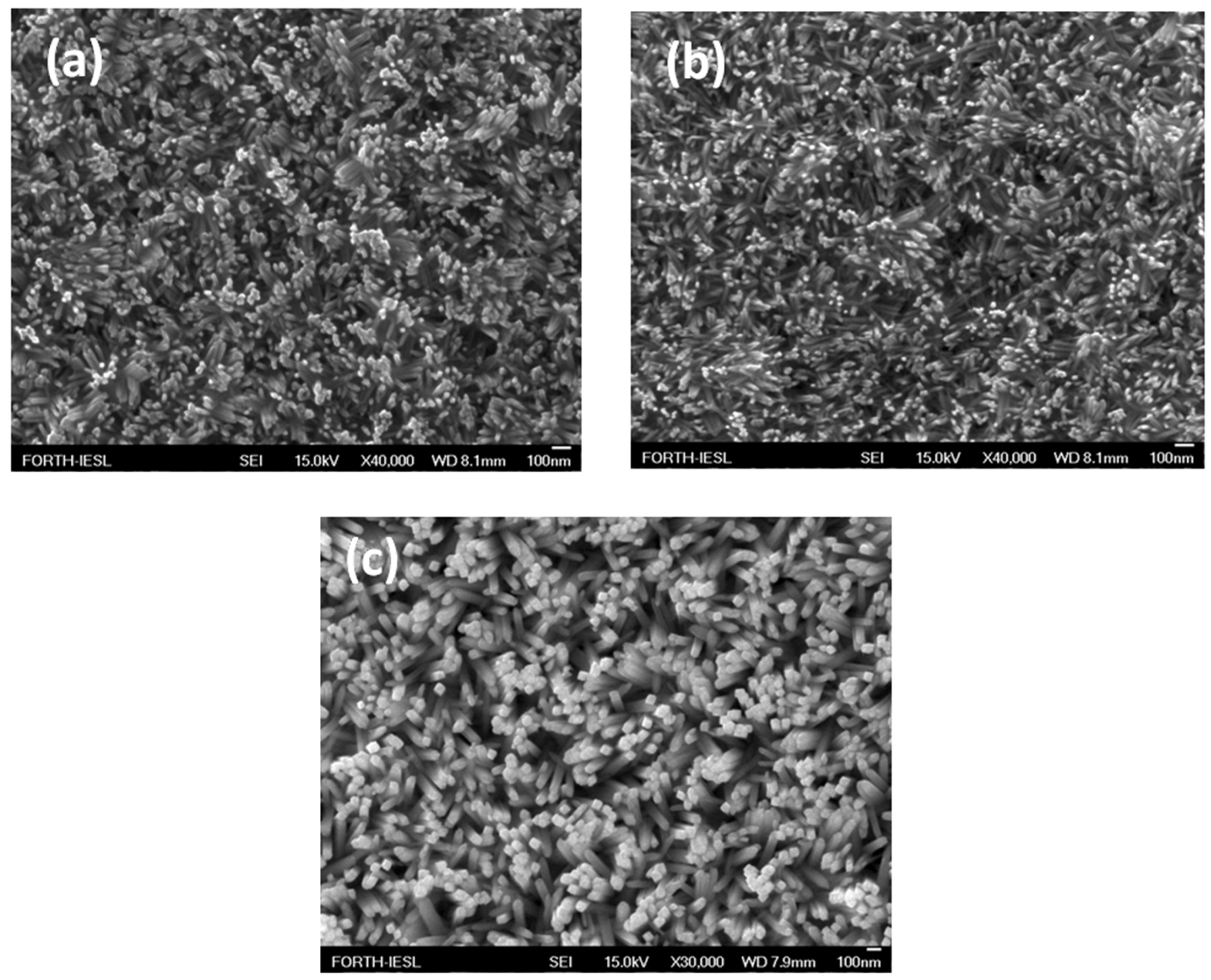

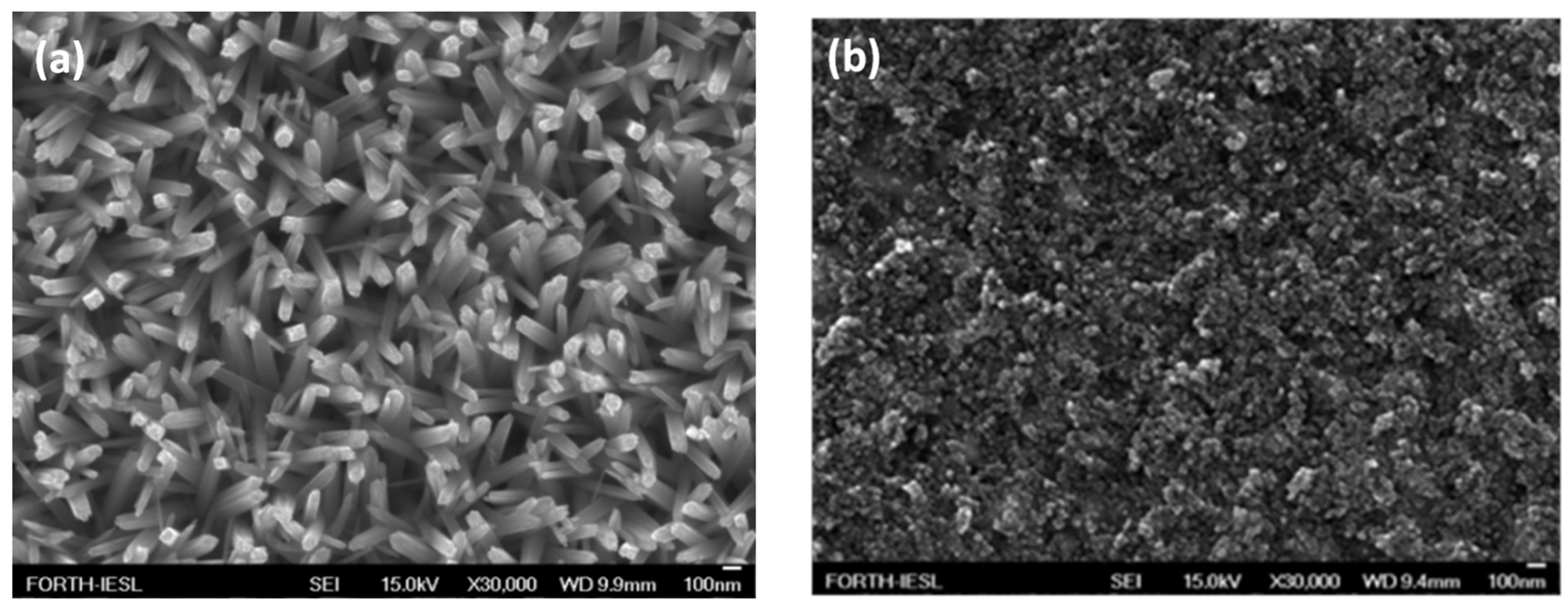

3.1. Properties of m-TiO2 and TiO2-NRs Materials

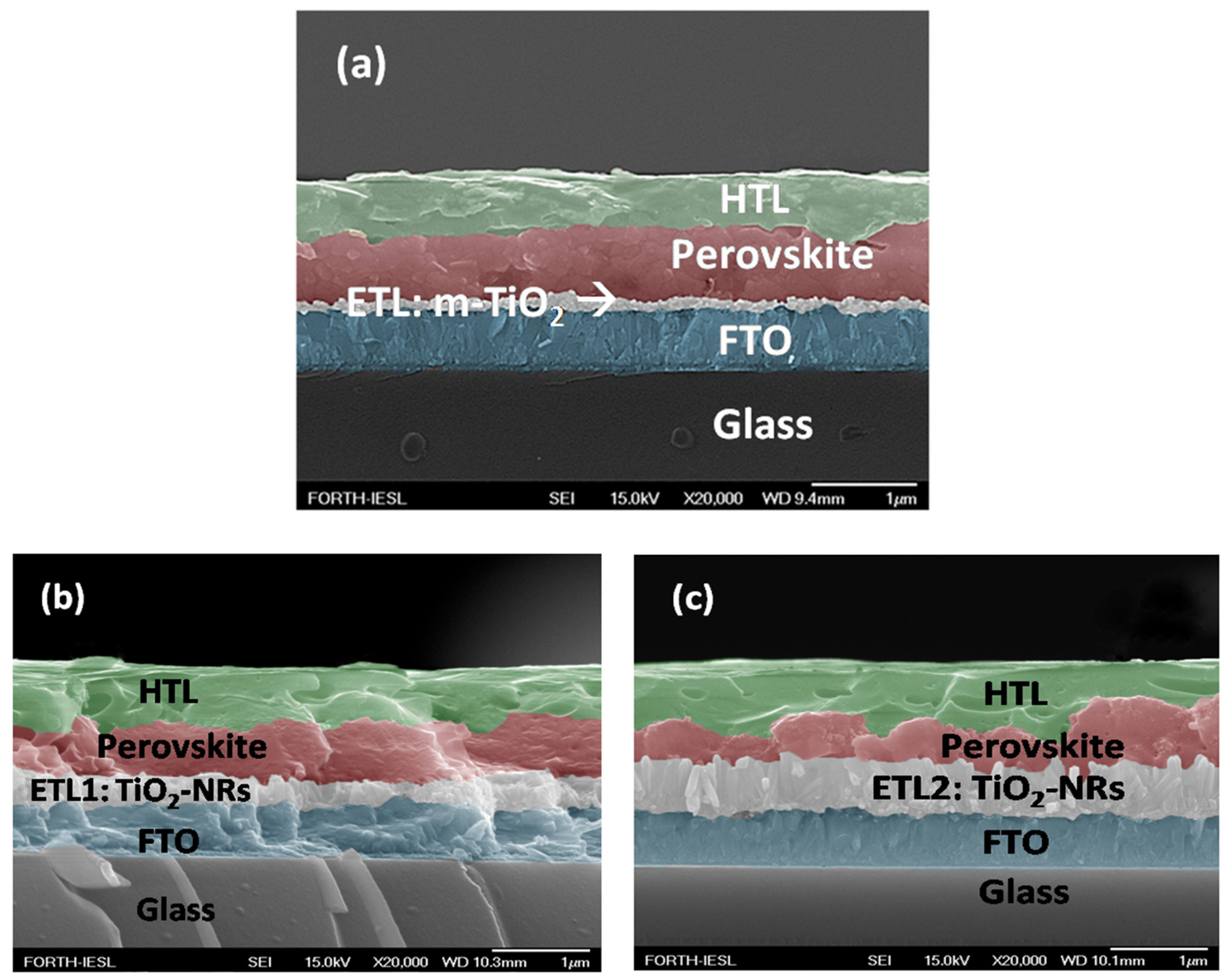

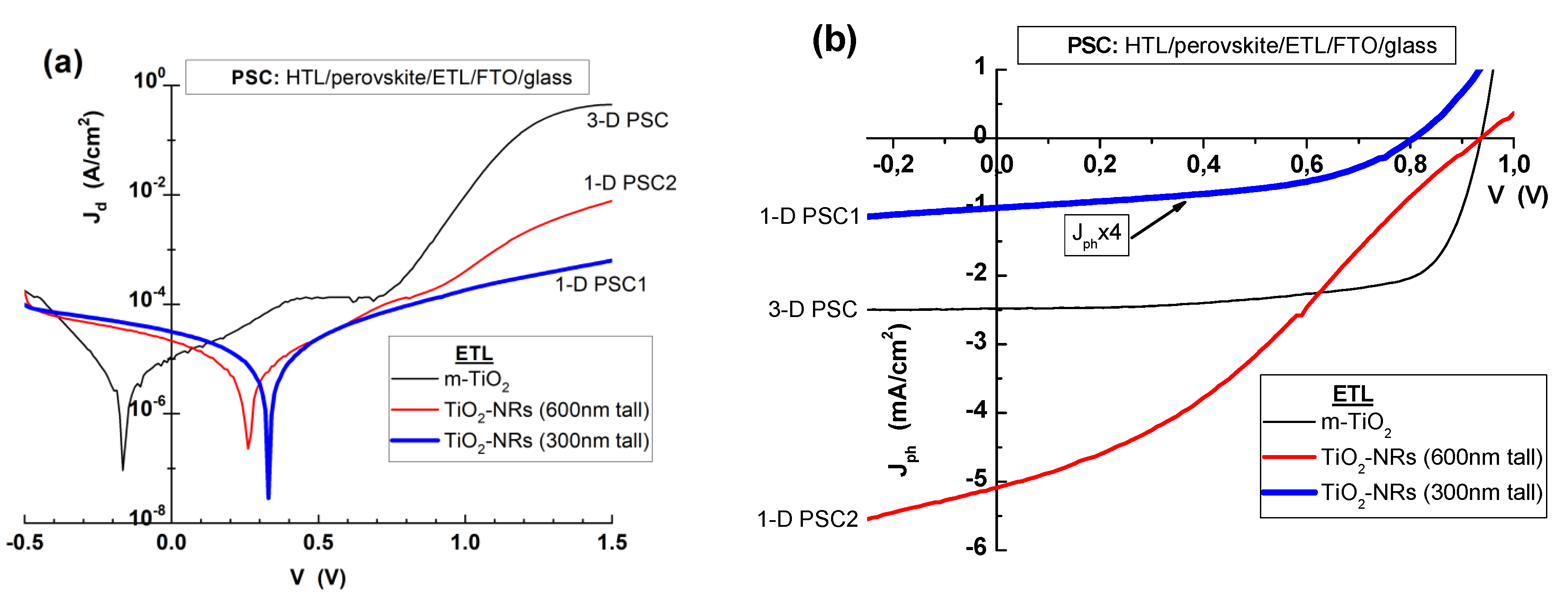

3.2. Perovskite Solar Cells with m-TiO2 and TiO2-NRs as ETL

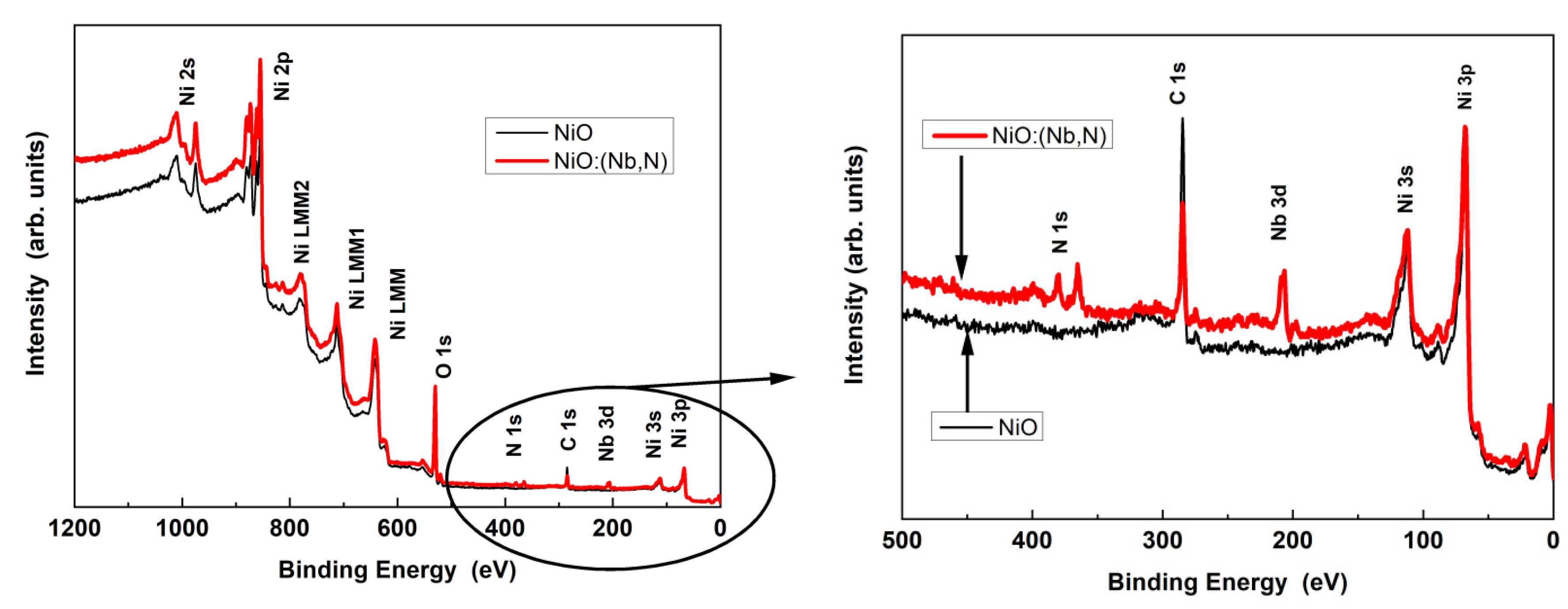

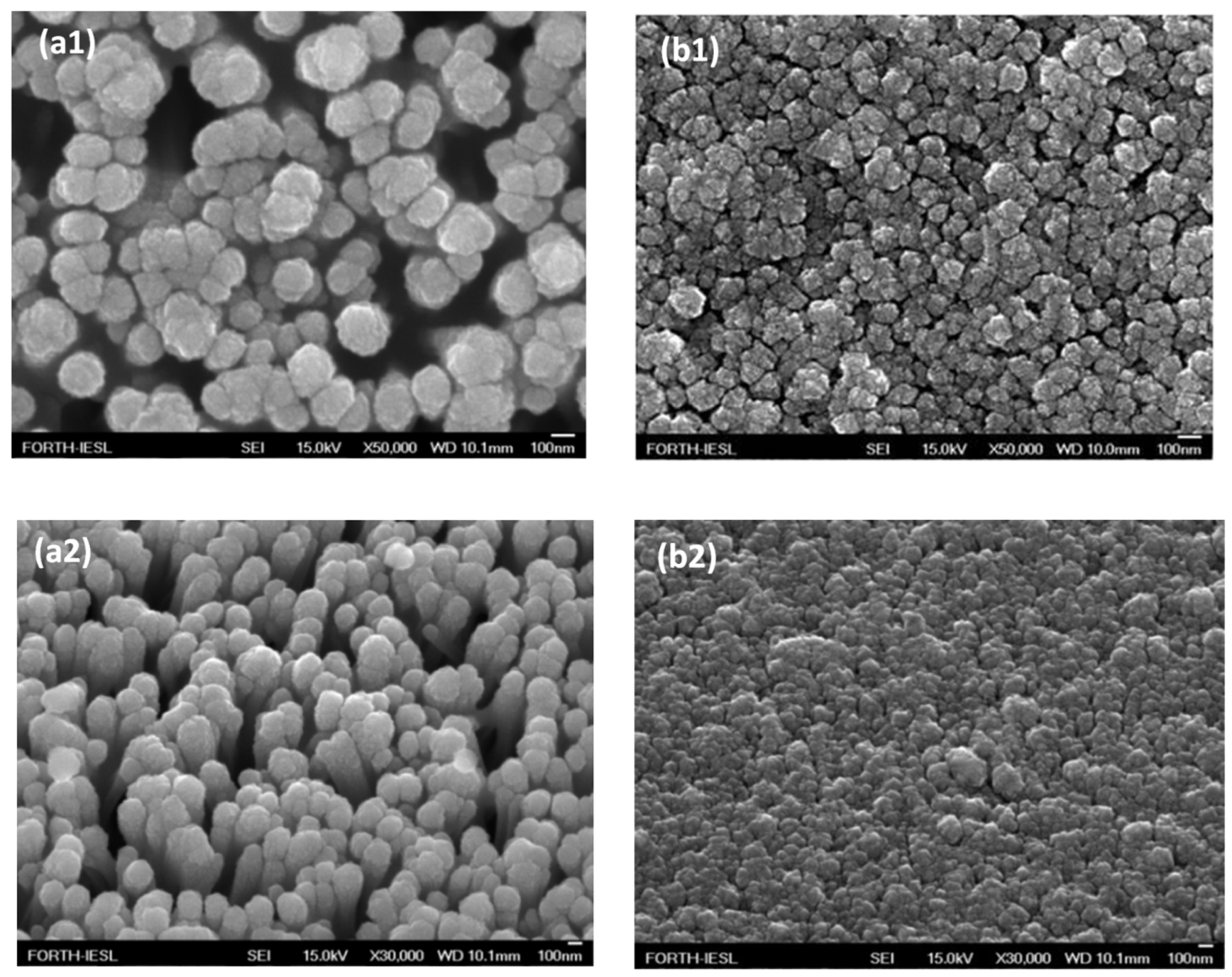

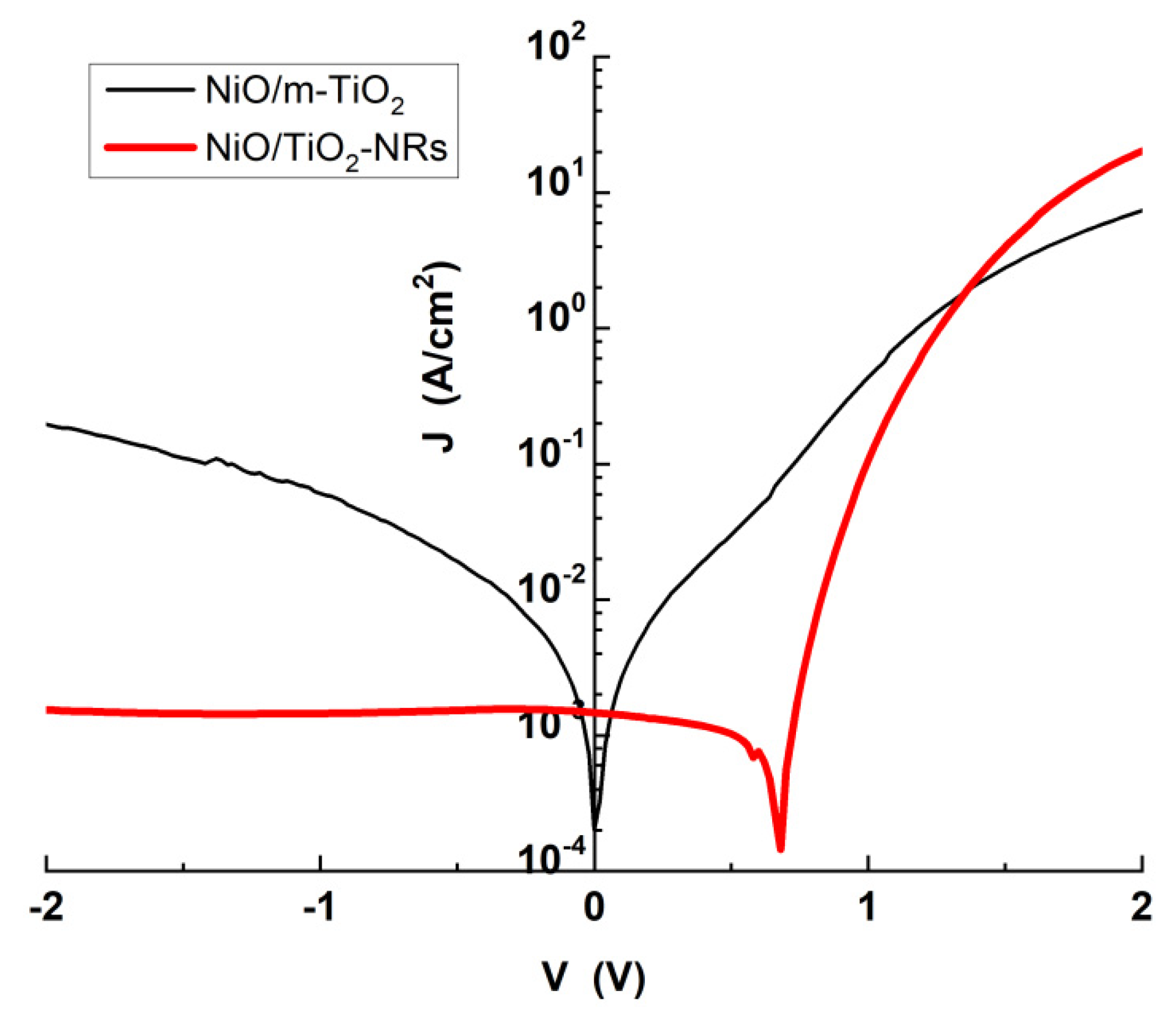

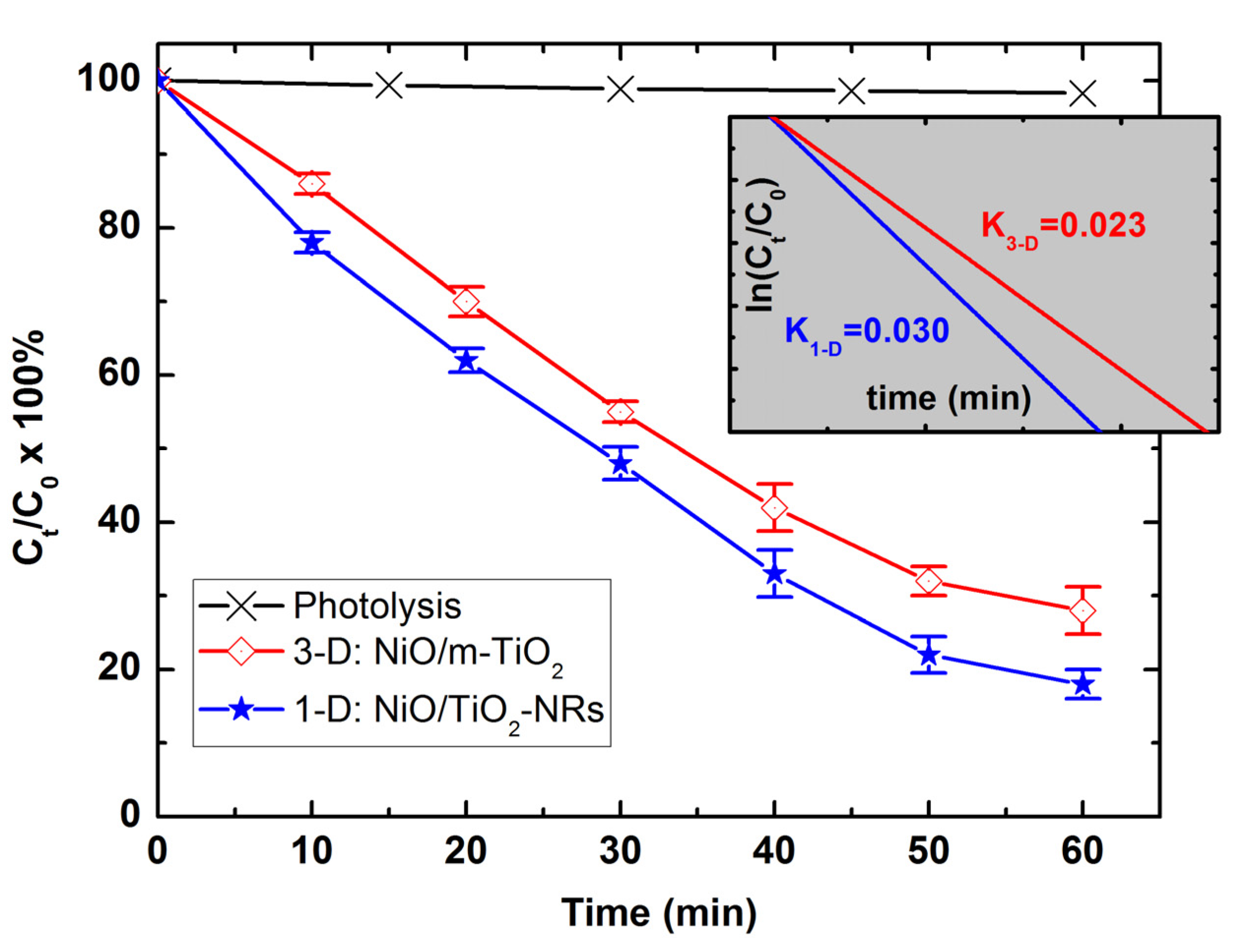

3.3. Photocatalytic NiO/TiO2 Heterostructures with m-TiO2 and TiO2-NRs as n-Type Layer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, W. Effect of the Fukushima nuclear disaster on global public acceptance of nuclear energy. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, B.; Opejin, A.; Pijawka, K.D. Risk Perceptions and Amplification Effects over Time: Evaluating Fukushima Longitudinal Surveys. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Bullard, R.; Buonocore, J.J.; Donley, N.; Farrelly, T.; Fleming, J.; González, D.J.X.; Oreskes, N.; Ripple, W.; Saha, R.; Willis, M.D. Scientists’ warning on fossil fuels. Oxford Open Climate Change 2025, 5, kgaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Earth 4, Elsevier Inc., 2021, p. 1515. [CrossRef]

- Sofroniou, C.; Scacchi, A.; Le, H.; Espinosa Rodriguez, E.; D'Agosto, F.; Lansalot, M.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Ternan, N.G.; Martín-Fabiani, I. Tunable Assembly of Photocatalytic Colloidal Coatings for Antibacterial Applications. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2024, 6, 10298–10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, M.; Tulliani, J.M. Green Synthesis of Metal Oxides Semiconductors for Gas Sensing Applications. Sensors. 2022, 22, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Dawson, G.; Zhang, J.; Shao, C.; Dai, K. Organic-inorganic hybrid-based S-scheme heterostructure in solar-to-fuel conversion. J. Mat. Sci. & Technology 2025, 233, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.D.; Shannigrahi, S.; Ramakrishna, S. A review of conventional, advanced, and smart glazing technologies and materials for improving indoor environment. Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 2017, 159, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, L.; Zhen Cheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, R. Indoor photovoltaic materials and devices for self-powered internet of things applications. Materials Today Energy 2024, 44, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, R.M.; Magnozzi, M.; Sygletou, M.; Colace, S.; D’Addato, S.; Petrov, A.Y.; Canepa, M.; Torelli, P.; di Bona, A.; Benedetti, S.; Bisio, F. Active optical modulation in hybrid transparent-conductive oxide/electro-optic multilayers. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 6346–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Arrieta, I.G.; Echániz, T.; Rubin, E.B.; Chung, K.M.; Chen, R.; López, G.A. AZO-coated refractory nanoneedles as ultra-black wide-angle solar absorbers. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2025, 293, 113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lv, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Lin, L.; Li, Z. Advancements in heterojunction, cocatalyst, defect and morphology engineering of semiconductor oxide photocatalysts. J. Materiomics 2024, 10, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, M.; Klüpfel, F.; Karsthof, R.; Schlupp, P.; Schein, F.-L.; Splith, D.; Yang, C.; Bitter, S.; Wenckstern, H. Oxide bipolar electronics: materials, devices and circuits. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2016; 49, 213001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, V.C.; Banerjee, A.N.; Joo, S.W. Recent developments in TiO2 as n- and p-type transparent semiconductors: synthesis, modification, properties, and energy-related applications. J. Mat. Sci. 2015, 50, 7495–7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.S.; Rajendran, S.; Mathew, T.; Gopinath, C.S. A review on the recent advances in the design and structure–activity relationship of TiO2-based photocatalysts for solar hydrogen production. Energy Adv. 2024, 3, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Jeon, Y.I.; Yang, I.S.; Choo, H.; Suh, W.S.; Ju, S.-Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Pan, J.H.; Lee, W.I. Selective Control of Novel TiO2 Nanorods: Excellent Building Blocks for the Electron Transport Layer of Mesoscopic Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 9447–9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Yang, B.L. Effect of seed layers on TiO2 nanorod growth on FTO for solar hydrogen generation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 5807–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.M.; Mamat, M.H.; Malek, M.F.; Suriani, A.B.; Mohamed, A.; Ahmad, M.K.; Salman, A.H.; Alrokayan, Khan, H.A.; Rusop, M. Growth of titanium dioxide nanorod arrays through the aqueous chemical route under a novel and facile low-cost method. Materials Letters 2016, 164, 294–298. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zou, L.; Jia You, J.; Lin, S. Optimization of charge transfer in dipole layer-tailored TiO2-CdS heterojunction photoanodes for solar hydrogen evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 711, 163924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivalioti, C.; Papadakis, A.; Manidakis, E.; Kayambaki, M.; Androulidaki, M.; Tsagaraki, K.; Pelekanos, N.T.; Stoumpos, C.; Modreanu, M.; Craciun, G.; Romanitan, C.; Aperathitis, E. Transparent All-Oxide Hybrid NiO:N/TiO2 Heterostructure for Optoelectronic Applications. Electronics 2021, 10, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivalioti, C.; Androulidaki, M.; Tsagaraki, K.; Manidakis, E.G.; Koliakoudakis, C.; Pelekanos, N.T.; Modreanu, M.; Aperathitis, E. The Effect of Nitrogen as a Co-Dopant in p-Type NiO:Nb Films on the Photovoltaic Performance of NiO/TiO2 Transparent Solar Cells. Solids 2024, 5, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivalioti, C.; Manidakis, E.G.; Pelekanos, N.T.; Androulidaki, M.; Tsagaraki, K.; Aperathitis, E. Anion and Cation Co Doping of NiO for Transparent Photovoltaics and Smart Window Applications. Crystals 2024, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, D.; Singh, F.; Das, R. X-ray diffraction analysis by Williamson-Hall, Halder-Wagner and size-strain plot methods of CdSe nanoparticles- a comparative study. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivalioti, C.; Papadakis, A.; Manidakis, E.; Kayambaki, M.; Androulidaki, M.; Tsagaraki, K.; Pelekanos, N.T.; Stoumpos, C.; Modreanu, M.; Craciun, G.; Romanitan, C.; Aperathitis, E. An Assessment of Sputtered Nitrogen-Doped Nickel Oxide for all-Oxide Transparent Optoelectronic Applications: The Case of Hybrid NiO:N/TiO2 Heterostructure. Recent Trends Chem. Mater. Sci. 2022, 6, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, E.; Stranks, S.D.; Manidakis, E.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Katan, C. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2902−2904. 4. [CrossRef]

- Syngelakis, I.; Manousidaki, M.; Kabouraki, E.; Kyriakakis, A.; Kenanakis, G.; Klini, A.; Tzortzakis, S.; Farsari, M. Laser direct writing of efficient 3D TiO2 nano-photocatalysts. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 134, 234504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.M. Physics of Semiconductor Devices, 2nd ed.; JohnWiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 978-0471098379. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Lo, S.; Song, K.; Vijayan, B.K.; Li, W.; Gray, K.A.; Dravid, V.P. Growth of rutile TiO2 nanorods on anatase TiO2 thin films on Si based substrates. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 26, 1646–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, D.; Dunnill, C.; Buckeridge, J.; Shevlin, S.A.; Logsdail, A.J.; Woodley, S.M.; C.; Richard, A.; Catlow, R.A.; Powell, M.J.; Palgrave, R.G.; Parkin, I.P.; Watson, G.W.; Keal, T.W.; Sherwood, P.; Walsh, A.; Sokol, A.A. Band alignment of rutile and anatase TiO2. Nature Mater 2013, 12, 798–801. [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Wang, O.; Liu, K.; Du, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, H. 2D homologous organic-inorganic hybrids as light-absorbers for planer and nanorod-based perovskite solar cells. Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 2017, 162, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, S.-M.; Zhu, P.; Deng, L.-L.; Xie, S.-Y.; Cui, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, N.; Lin, H. Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells Depending on TiO2 Nanorod Arrays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 21358–21365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Agarwal, S.; Dhaka, M.S. Role of transport layers in efficiency enhancement of perovskite solar cells. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 222, 115795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Ji, J.; Song, D.; Li, M.; Cui, P.; Li, Y.; Mbengue, J.M.; Zhou, W.; Ning, Z.; Park, N.-G. A TiO2 embedded structure for perovskite solar cells with anomalous grain growth and effective electron extraction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A.Y.; Smirnov, N.B.; Shchemerov, I.V.; Vasilev, A.A.; Kochkova, A.I.; Chernykh, A.V.; Lagov, P.B.; Pavlov, Y.S.; Stolbunov, V.S.; Kulevoy, T.V.; Borzykh, I.V.; Lee, I.-H.; Ren, F.; Pearton, S.J. Crystal orientation dependence of deep level spectra in proton irradiated bulk β-Ga2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 035701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wu, J.; Tu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Dong, J.; Jia, J.; Wei, Y.; Lan. Z. TiO2 single crystalline nanorod compact layer for high-performance CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells with an efficiency exceeding 17%. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 332, 366e371. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Tao, H.; Qin, P.; Ke, W.; Fang, G. Recent progress in electron transport layers for efficient perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Mende, L.; Dyakonov, V.; Olthof, S.; et al. Roadmap on organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite semiconductors and devices. APL Mater. 2021, 9, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Pan, J.; Cai, K.; Cong, Y.; Lv, S.-W. The construction of p-n heterojunction for enhancing photocatalytic performance in environmental application: A review. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 315, 123708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivalioti, Ch.; Manidakis, E.G.; Pelekanos, N.T.; Androulidaki, M.; Tsagaraki, K.; Viskadourakis, Z.; Spanakis, E.; Aperathitis. E. Niobium-doped NiO as p-type nanostructured layer for transparent photovoltaics. Thin Solid Films 2023, 778, 139910. [CrossRef]

- Kondi, A.; Papia, E.-M.; Constantoudis, V.; Nioras, D.; Syngelakis, I.; Aivalioti, C.; Aperathitis, E.; Gogolides, E. Measurement of thickness of thin coatings on rough substrates via computational analysis of SEM images. MNE 2025, 28, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yao, C.; Ding, B.; Xu, N.; Sun, J.; Wu, J. Influence of metal covering with a Schottky or ohmic contact on the emission properties of ZnO nanorod arrays. J. Luminescence 2023, 257, 119729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.-H.; Ho, H.-C.; Liao, H.-T.; Tsai, F.-Y.; Tsao, C.-W.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Hsueh, C.-H. Plasmonic gold nanoplates-decorated ZnO branched nanorods@TiO2 nanorods heterostructure photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting J. Photochemistry & Photobiology. A: Chemistry 2023, 443, 114816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsthof, R.; von Wenckstern, H.; Zúniga-Pérez, J.; Deparis, C.; Grundmann, M. Nickel Oxide–Based Heterostructures with Large Band Offsets. Phys. Status Solidi B 2020, 257, 1900639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Patel, M.; Kim, J. All-inorganic metal oxide transparent solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 217, 110708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.D.; Jiang, C.I.; Hwang, S.B. P-NiO/n-ZnO heterojunction photodiodes with a MgZnO/ZnO quantum well insertion layer. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 105, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.B.; Zhou, Y.J.; Xiang, G.J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, J.M.; Huang, H.X.; Mei, M.Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y. Preparation of AlN thin film and the impacts of AlN buffer layer on the carrier transport properties of p-NiO/n-InN heterojunction by magnetron sputtering. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 141, 106417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawidowski, W.; Sciana, B.; Bielak, K.; Mikolášek, M.; Drobn, J.; Serafinczuk, J.; Lombardero, I.; Radziewicz, D.; Kijaszek, W.; Kósa, A.; et al. Analysis of Current Transport Mechanism in AP-MOVPE Grown GaAsN p-i-n Solar Cell. Energies 2021, 14, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Z.; Chen, T.-H.; Lai, L.-W.; Li, P.-Y.; Liu, H.-W.; Hong, Y.-Y.; Liu, D.-S. Preparation and Characterization of Surface Photocatalytic Activity with NiO/TiO2 Nanocomposite Structure. Materials 2015, 8, 4273–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-J.; Liao, C.-H.; Hsu, K.-C.; Wu, Y.-T.; Wu, J.C.S. P–N junction mechanism on improved NiO/TiO2 photocatalyst. Catalysis Communications 2011, 12, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, M.; Han, J.; Guo, R. TiO2 nanosheet/NiO nanorod hierarchical nanostructures: p–n heterojunctions towards efficient photocatalysis. J. Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 562, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamayor, A.; Pomone, T.; Perero, S.; Ferraris, M.; Barrio, V.L.; Berasategui, E.G.; Kelly, P. Development of photocatalytic nanostructured TiO2 and NiO/TiO2 coatings by DC magnetron sputtering for photocatalytic applications. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 19309–19317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

PSC (ETL) |

Jd-V analysis | Jph-V analysis | ||||

| RS (kΩ) |

n | JSC (mA/cm2) | VOC (mV) |

FF | η (%) |

|

| 3-D PSC (m-TiO2) | 0.16 | 2.31 | 2.47 | 936 | 70.5 | 1.63 |

| 1-D PSC1 (TiO2-NRs 300 nm) | 45.16 | 11.67 | 0.26 | 805 | 45.4 | 0.09 |

| 1-D PSC2 (TiO2-NRs 600 nm) | 3.25 | 4.84 | 5.10 | 936 | 33.1 | 1.58 |

| NiO Samples |

Treatment | roughness (nm) | 2θ (degree) | D (nm) | εL (x10-2) |

Direct Egap (eV) | ρ (Ωcm) |

| undoped NiO |

As-prepared | 2.87 | 42.56 | 5.33 | 1.77 | 3.28 | 1.4x10-1 |

| TT1 | - | 43.40 | 7.44 | 1.24 | 3.67 | 1.6x103 | |

| double-doped NiO:(Nb,N) |

As-prepared | 2.75 | 42.66 | 10.07 | 0.94 | 3.71 | 6.9x103 |

| TT1 | 43.04 | 9.13 | 1.02 | 3.74 | - |

| Heterostructure | JS (A/cm2) |

RS (Ω) |

n | φb (eV) |

| NiO/m-TiO2 | 2x10-3 | 8.20 | 6.96 | 0.58 |

| NiO/TiO2-NRs | 2x10-8 | 2.90 | 2.50 | 0.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).