Submitted:

18 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location

2.2. Herbaceous Layer Plants Recording

2.3. Measurement of Soil and Microclimatic Properties

2.4. Canopy Structure and Gap Light Transmission Indices

2.5. Plant Functional Traits

2.6. Species and Functional Diversity Indices

2.7. Tree Community Ordination

2.8. Structural Equation Modelling

3. Results

3.1. The Parameters of the Urban Park Tree Stand

3.2. Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling of Urban Park Tree Communities

3.3. The Properties of the Environment and Herbaceous Cover

3.4. Influence of Tree Stands on Environmental Properties and Herbaceous Cover

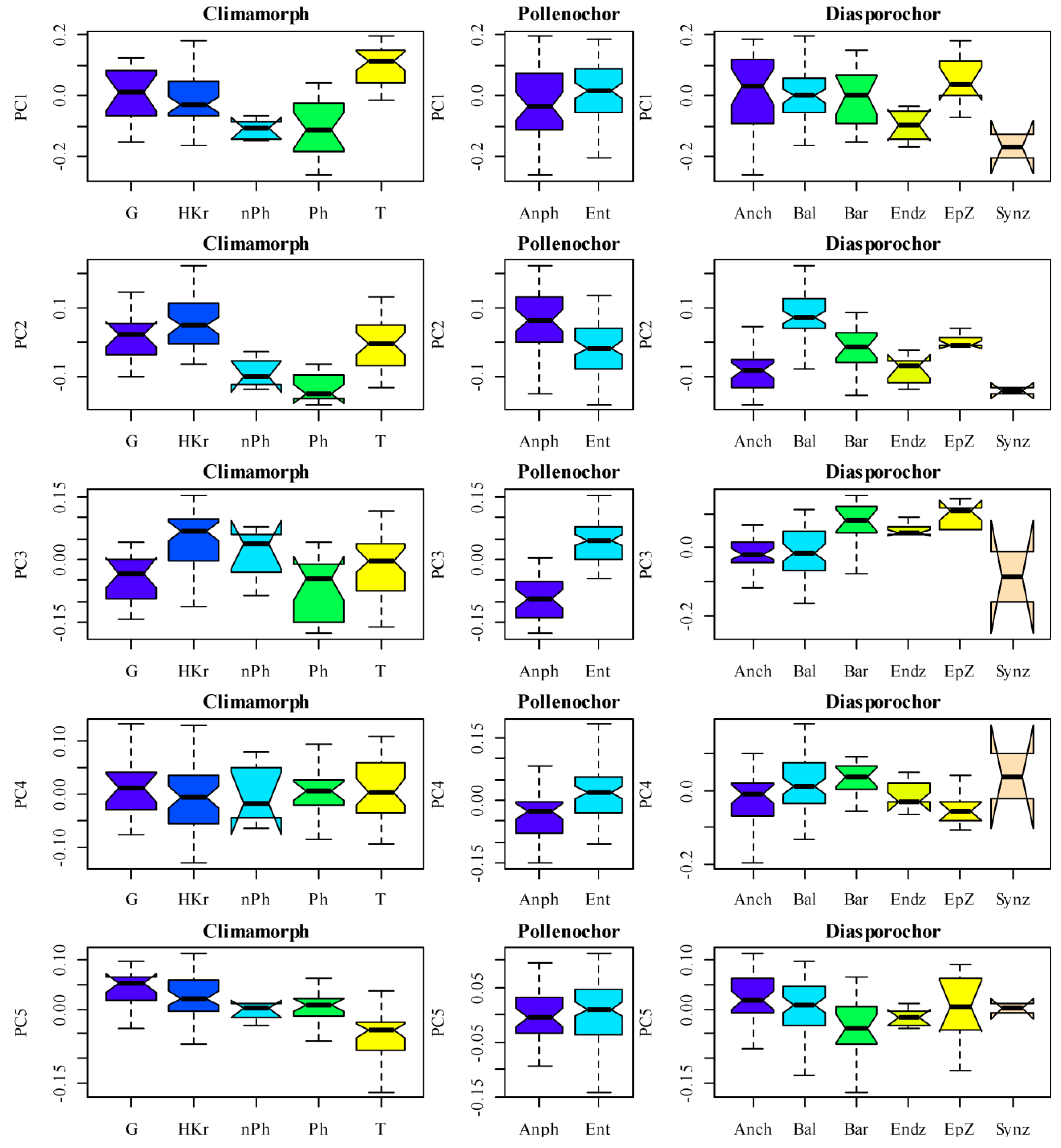

3.5. Functional Axes of Herbaceous Plants

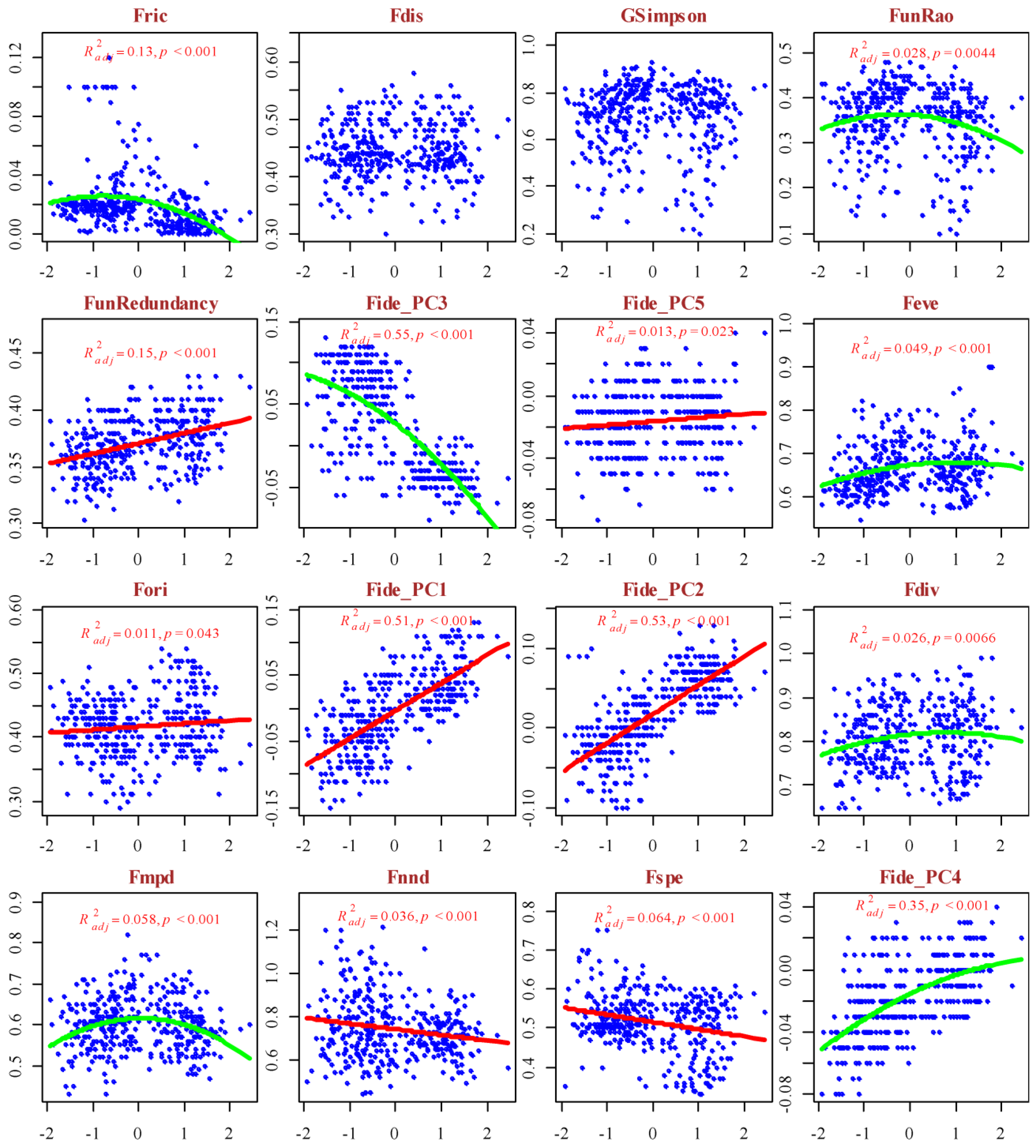

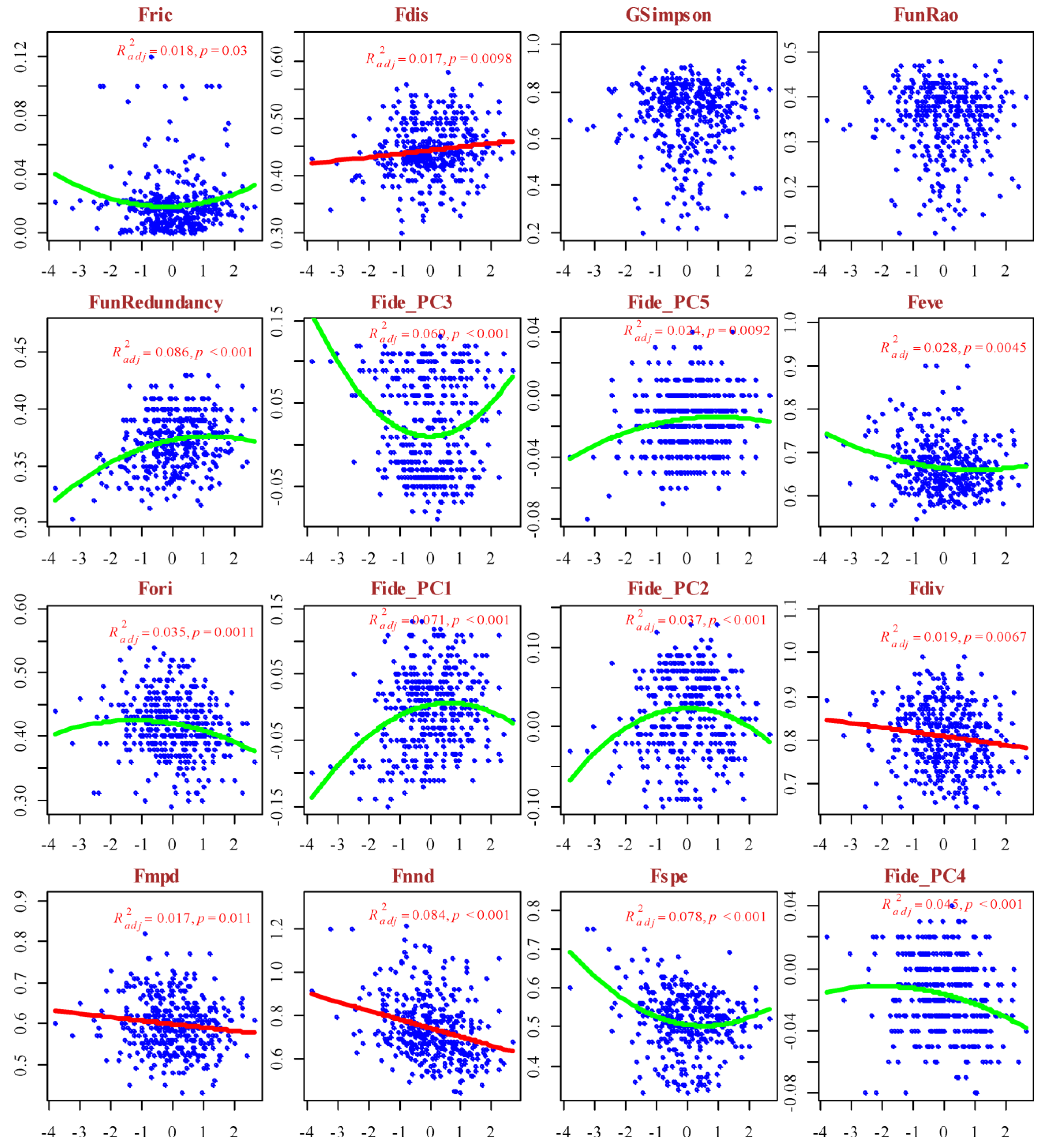

3.6. The Functional Diversity Indices of Herbaceous Plant Communities Along the Gradient of Hemeroby and Naturalness

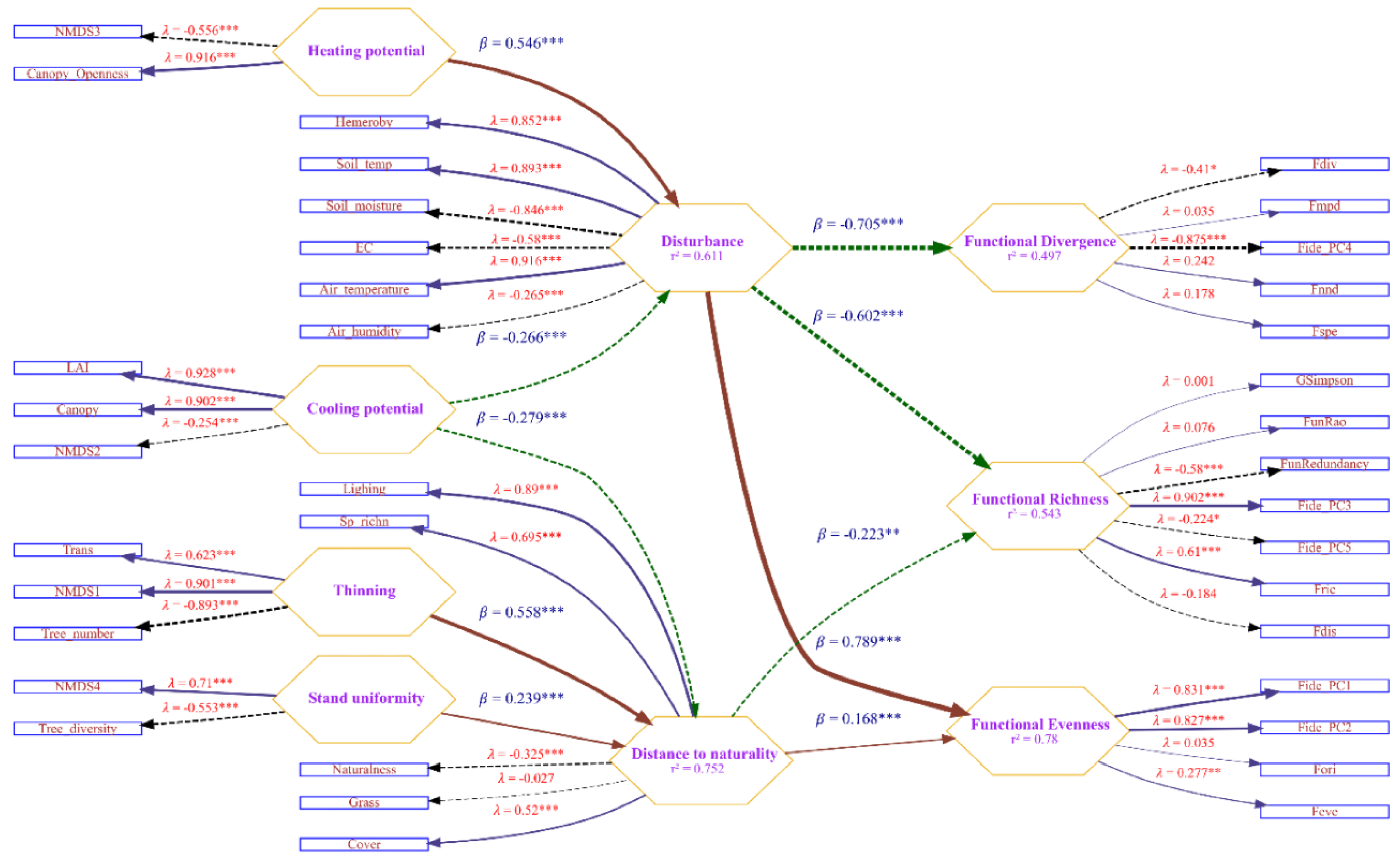

3.7. Structural Equation Modelling of the Influence of Tree Stands on the Environmental Properties and Functional Diversity of Herbaceous Cover

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molozhon, K.O.; Lisovets, O.I.; Kunakh, O.M.; Zhukov, O.V. The Structure of Beta-Diversity Explains Why the Relevance of Phytoindication Increases under the Influence of Park Reconstruction. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2023, 14, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myalkovsky, R.; Plahtiy, D.; Bezvikonnyi, P.; Horodyska, O.; Nebaba, K. Urban Parks as an Important Component of Environmental Infrastructure: Biodiversity Conservation and Recreational Opportunities. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2023, 14, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Urban Trees in the USA. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemanowicz, J.; Haddad, S.A.; Bartkowiak, A.; Lamparski, R.; Wojewódzki, P. The Role of an Urban Park’s Tree Stand in Shaping the Enzymatic Activity, Glomalin Content and Physicochemical Properties of Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komlyk, Y.; Ponomarenko, O.; Zhukov, O. A Hemeroby Gradient Reveals the Structure of Bird Communities in Urban Parks. Biosyst. Divers. 2024, 32, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexia, T.; Vieira, J.; Príncipe, A.; Anjos, A.; Silva, P.; Lopes, N.; Freitas, C.; Santos-Reis, M.; Correia, O.; Branquinho, C.; et al. Ecosystem Services: Urban Parks under a Magnifying Glass. Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnaruk, E.W.; Kroll, C.N.; Yang, Y.; Hirabayashi, S.; Nowak, D.J.; Endreny, T.A. Where to Plant Urban Trees? A Spatially Explicit Methodology to Explore Ecosystem Service Tradeoffs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenk, A.; Richter, R.; Kretz, L.; Wirth, C. Effects of Canopy Gaps on Microclimate, Soil Biological Activity and Their Relationship in a European Mixed Floodplain Forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 941, 173572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Hautier, Y.; Bao, D.; Xu, M.; Yang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yan, E. Functionally Diverse Tree Stands Reduce Herbaceous Diversity and Productivity via Canopy Packing. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunakh, O.M.; Lisovets, O.I.; Yorkina, N.V.; Zhukova, Y.O. Phytoindication Assessment of the Effect of Reconstruction on the Light Regime of an Urban Park. Biosyst. Divers. 2021, 29, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Ağırtaş, L. Canopy Parameters for Tree and Shrub Species Compositions in Differently Intervened Land Uses of an Urban Park Landscape. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Lugilde, D.; Lenoir, J.; Abdulhak, S.; Aeschimann, D.; Dullinger, S.; Gégout, J.; Guisan, A.; Pauli, H.; Renaud, J.; Theurillat, J.; et al. Tree Cover at Fine and Coarse Spatial Grains Interacts with Shade Tolerance to Shape Plant Species Distributions across the Alps. Ecography (Cop.). 2015, 38, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Guo, M.; Yin, F.; Zhang, M.-J.; Wei, J. Tree Cover Improved the Species Diversity of Understory Spontaneous Herbs in a Small City. Forests 2022, 13, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunakh, O.M.; Volkova, A.M.; Tutova, G.F.; Zhukov, O.V. Diversity of Diversity Indices: Which Diversity Measure Is Better? Biosyst. Divers. 2023, 31, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlik, M.; Kasprowicz, M.; Jagodziński, A.M.; Kaźmierowski, C.; Łukowiak, R.; Grzebisz, W. Canopy Tree Species Determine Herb Layer Biomass and Species Composition on a Reclaimed Mine Spoil Heap. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, I.; Sixto, H.; Rodríguez-Soalleiro, R.; Cañellas, I.; Fuertes, A.; Oliveira, N. How Can Leaf-Litter from Different Species Growing in Short Rotation Coppice Contribute to the Soil Nutrient Pool? For. Ecol. Manage. 2022, 520, 120405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ni, X.; Heděnec, P.; Yue, K.; Wei, X.; Yang, J.; Wu, F. Litter Facilitates Plant Development but Restricts Seedling Establishment during Vegetation Regeneration. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 3134–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, E.K.S.; Sands, R. Competition for Water and Nutrients in Forests. Can. J. For. Res. 1993, 23, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczyńska, K.; Orczewska, A.; Yurchenko, V.; Wójcicka-Rosińska, A.; Świerkosz, K. Changes in Species and Functional Diversity of the Herb Layer of Riparian Forest despite Six Decades of Strict Protection. Forests 2022, 13, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meili, N.; Manoli, G.; Burlando, P.; Carmeliet, J.; Chow, W.T.L.; Coutts, A.M.; Roth, M.; Velasco, E.; Vivoni, E.R.; Fatichi, S. Tree Effects on Urban Microclimate: Diurnal, Seasonal, and Climatic Temperature Differences Explained by Separating Radiation, Evapotranspiration, and Roughness Effects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyen, K.; Gillerot, L.; Blondeel, H.; De Frenne, P.; De Pauw, K.; Depauw, L.; Lorer, E.; Sanczuk, P.; Schreel, J.; Vanneste, T.; et al. Forest Canopies as Nature-based Solutions to Mitigate Global Change Effects on People and Nature. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylewski, Ł.; Banaszak-Cibicka, W.; Maćkowiak, Ł.; Dyderski, M.K. How Do Urbanization and Alien Species Affect the Plant Taxonomic, Functional, and Phylogenetic Diversity in Different Types of Urban Green Areas? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 92390–92403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Ding, L.; Kong, C.-H. Allelopathy and Allelochemicals in Grasslands and Forests. Forests 2023, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrenbach, H.; Grahl, B.; Giegrich, J.; Busch, M. Hemeroby as an Impact Category Indicator for the Integration of Land Use into Life Cycle (Impact) Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, R.; Nykytiuk, Y.; Komorna, О.; Kravchenko, O.; Zymaroieva, A. Ecological Groups of Birds of Zhytomyr Region (Ukraine) in Relation to Thermal Regime and Their Future Prospects in the Context of Global Climate Change. Biosyst. Divers. 2024, 32, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; States, S.L. Urban Green Spaces and Sustainability: Exploring the Ecosystem Services and Disservices of Grassy Lawns versus Floral Meadows. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Hedblom, M. An Alternative Urban Green Carpet. Science (80-. ). 2018, 362, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Bending, G.D.; Clark, R.; Corstanje, R.; Dunnett, N.; Evans, K.L.; Grafius, D.R.; Gravestock, E.; Grice, S.M.; Harris, J.A.; et al. Urban Meadows as an Alternative to Short Mown Grassland: Effects of Composition and Height on Biodiversity. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Flies, E.J.; Weinstein, P.; Woodward, A. The Impact of Green Space and Biodiversity on Health. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Chong, S.; Jalaudin, B.; Wardle, K.; Merom, D. Green Grass in Urban Parks Are a Necessary Ingredient for Sedentary Recreation. J. Park Recreat. Admi. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboufazeli, S.; Jahani, A.; Farahpour, M. Aesthetic Quality Modeling of the Form of Natural Elements in the Environment of Urban Parks. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, P. The Effect of Light Availability on Leaf Area Index, Biomass Production and Plant Species Composition of Park Grasslands in Warsaw. Plant Soil Environ. 2013, 59, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayón, Á.; Godoy, O.; Maurel, N.; van Kleunen, M.; Vilà, M. Proportion of Non-Native Plants in Urban Parks Correlates with Climate, Socioeconomic Factors and Plant Traits. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-P.; Fan, S.-X.; Hao, P.-Y.; Dong, L. Temporal Variations of Spontaneous Plants Colonizing in Different Type of Planted Vegetation-a Case of Beijing Olympic Forest Park. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, R.; Nykytiuk, Y.; Komorna, О.; Zymaroieva, A. Global Climate Change Promotes the Expansion of Rural and Synanthropic Bird Species: The Case of Zhytomyr Region (Ukraine). Biosyst. Divers. 2024, 32, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Lundholm, J.T. Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Spontaneous Vegetation. Urban Ecosyst. 2012, 15, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, D.; Cosmulescu, S. Spontaneous Plant Diversity in Urban Contexts: A Review of Its Impact and Importance. Diversity 2023, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredici, P. Del Spontaneous Urban Vegetation: Reflections of Change in a Globalized World. Nat. Cult. 2010, 5, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Al Sayed, N.; Barré, K.; Halwani, J.; Machon, N. Drivers of the Distribution of Spontaneous Plant Communities and Species within Urban Tree Bases. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 35, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czortek, P.; Pielech, R. Surrounding Landscape Influences Functional Diversity of Plant Species in Urban Parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 47, 126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violle, C.; Navas, M.-L.; Vile, D.; Kazakou, E.; Fortunel, C.; Hummel, I.; Garnier, E. Let the Concept of Trait Be Functional! Oikos 2007, 116, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanok, L.; Marod, D.; Duengkae, P.; Pranmongkol, U.; Kurokawa, H.; Aiba, M.; Katabuchi, M.; Nakashizuka, T. Relationships between Functional Traits and the Ability of Forest Tree Species to Reestablish in Secondary Forest and Enrichment Plantations in the Uplands of Northern Thailand. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 296, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleuter, D.; Daufresne, M.; Massol, F.; Argillier, C. A User’s Guide to Functional Diversity Indices. Ecol. Monogr. 2010, 80, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetti, M.; Guevara, R.; Côrtes, M.C.; Fadini, R.; Von Matter, S.; Leite, A.B.; Labecca, F.; Ribeiro, T.; Carvalho, C.S.; Collevatti, R.G.; et al. Functional Extinction of Dirds Drives Rapid Evolutionary Changes in Seed Size. Science (80-. ). 2013, 340, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.E.; Kasel, S.; Tausz, M.; Bennett, L.T. Leaf Traits of Eucalyptus Arenacea (Myrtaceae) as Indicators of Edge Effects in Temperate Woodlands of South-Eastern Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 2013, 61, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zang, R.; Letcher, S.G.; Liu, S.; He, F. Disturbance Regime Changes the Trait Distribution, Phylogenetic Structure and Community Assembly of Tropical Rain Forests. Oikos 2012, 121, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Richardson, D.M. Traits Associated with Invasiveness in Alien Plants: Where Do We Stand. In Biological Invasions. Ecological Studies, vol 193; Nentwig, W., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008; pp. 97–125. [Google Scholar]

- Milanović, M.; Knapp, S.; Pyšek, P.; Kühn, I. Linking Traits of Invasive Plants with Ecosystem Services and Disservices. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakeman, R.J. Functional Diversity Indices Reveal the Impacts of Land Use Intensification on Plant Community Assembly. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, O.; Kunakh, O.; Yorkina, N.; Tutova, A. Response of Soil Macrofauna to Urban Park Reconstruction. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 220156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisovets, O.; Khrystov, O.; Kunakh, O.; Zhukov, O. Application of Hemeroby and Naturalness Indicators for Monitoring the Aquatic Macrophyte Communities in Protected Areas. Biosyst. Divers. 2024, 32, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, B.V.; van Iersel, M. 3 Ways to Measure Medium EC. GMPro 2002, 22, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkina, N.V.; Teluk, P.; Umerova, A.; Budakova, V.S.; Zhaley, O.A.; Ivanchenko, K.O.; Zhukov, O. V Assessment of the Recreational Transformation of the Grass Cover of Public Green Spaces. Agrology 2021, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.; Cahalan, C.; Hale, S.; Gibbons, J.M. Rapid Assessment of Forest Canopy and Light Regime Using Smartphone Hemispherical Photography. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 10556–10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, P.; Linder, S.; Smolander, H.; Flower-Ellis, J. Performance of the LAI-2000 Plant Canopy Analyzer in Estimating Leaf Area Index of Some Scots Pine Stands. Tree Physiol. 1994, 14, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattge, J.; Diaz, S.; Lavorel, S.; Prentice, I.; Leadley, P.; Bönisch, G.; Garnier, E.; Westoby, M.; Reich, P.; Wright, I.; et al. TRY - a Global Database of Plant Traits. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 2905–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lososová, Z.; Axmanová, I.; Chytrý, M.; Midolo, G.; Abdulhak, S.; Karger, D.N.; Renaud, J.; Van Es, J.; Vittoz, P.; Thuiller, W. Seed Dispersal Distance Classes and Dispersal Modes for the European Flora. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2023, 32, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengler, J.; Jansen, F.; Chusova, O.; Hüllbusch, E.; Nobis, M.P.; Van Meerbeek, K.; Axmanová, I.; Bruun, H.H.; Chytrý, M.; Guarino, R.; et al. Ecological Indicator Values for Europe (EIVE) 1.0. Veg. Classif. Surv. 2023, 4, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdős, L.; Bede-Fazekas, Á.; Bátori, Z.; Berg, C.; Kröel-Dulay, G.; Magnes, M.; Sengl, P.; Tölgyesi, C.; Török, P.; Zinnen, J. Species-Based Indicators to Assess Habitat Degradation: Comparing the Conceptual, Methodological, and Ecological Relationships between Hemeroby and Naturalness Values. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.; Klotz, S. Biologisch-Ökologische Daten Zur Flora Der DDR; M.artin-Luther- Universität: Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Goncharenko, I.V. Fitoindykaciya Antropogennogo Navantazhennya [Phytoindication of Anthropogenic Factor]; Serednyak T.K.: Dnipro (in Ukranian), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Borhidi, A. Social Behaviour Types, the Naturalness and Relative Ecological Indicator Values of the Higher Plants in the Hungarian Flora. Acta Bot. Hung. 1995, 39, 97–181. [Google Scholar]

- Grime, J.P. Vegetation Classification by Reference to Strategies. Nature 1974, 250, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raunkiaer, C. Plant Life Forms; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Zhukov, O.; Lisovets, O.; Molozhon, K. Differential Ecomorphic Analysis of Urban Park Vegetation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1254, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.V. Flora of Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia Regions; Travleev, A.P., Ed.; Dnipropetrovsk: Lira (in Ukranian), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Magneville, C.; Loiseau, N.; Albouy, C.; Casajus, N.; Claverie, T.; Escalas, A.; Leprieur, F.; Maire, E.; Mouillot, D.; Villéger, S. MFD: An R Package to Compute and Illustrate the Multiple Facets of Functional Diversity. Ecography (Cop.). 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R1174–R1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debastiani, V.J.; Pillar, V.D. SYNCSA—R Tool for Analysis of Metacommunities Based on Functional Traits and Phylogeny of the Community Components. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2067–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.; Patil, I.; Waggoner, P.; Makowski, D. Performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-2. 2018.

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; C.lassroom Companion: Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80518-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S.; Danks, N.; Calero Valdez, A. SEMinR: Domain-Specific Language for Building, Estimating, and Visualizing Structural Equation Models in R. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Tree Composition and Diversity in Relation to Urban Park History in Hong Kong, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molozhon, K.O.; Lisovets, O.I.; Kunakh, O.M.; Zhukov, O.V. Increased Soil Penetration Resistance Drives Degrees of Hemeroby in Vegetation of Urban Parks. Biosyst. Divers. 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Lin, B.B.; Gaston, K.J.; Bush, R.; Fuller, R.A. What Is the Role of Trees and Remnant Vegetation in Attracting People to Urban Parks? Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; van den Bosch, M.; Maruthaveeran, S.; van den Bosch, C.K. Species Richness in Urban Parks and Its Drivers: A Review of Empirical Evidence. Urban Ecosyst. 2014, 17, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayachee, A.L.; Irlich, U.M.; Faulkner, K.T.; Gaertner, M.; Procheş, Ş.; Wilson, J.R.U.; Rouget, M. How Do Invasive Species Travel to and through Urban Environments? Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3557–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchuelo, G.; Kowarik, I.; von der Lippe, M. Endangered Plants in Novel Urban Ecosystems Are Filtered by Strategy Type and Dispersal Syndrome, Not by Spatial Dependence on Natural Remnants. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, H.E. Comparison of Maximum Size–Density Relationships Based on Alternate Stand Attributes for Predicting Tree Numbers and Stand Growth. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 289, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, G.; Cubera, E. Impact of Stand Density on Water Status and Leaf Gas Exchange in Quercus Ilex. For. Ecol. Manage. 2008, 254, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Benito, D.; Del Río, M.; Heinrich, I.; Helle, G.; Cañellas, I. Response of Climate-Growth Relationships and Water Use Efficiency to Thinning in a Pinus Nigra Afforestation. For. Ecol. Manage. 2010, 259, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talal, M.L.; Santelmann, M.V.; Tilt, J.H. Urban Park Visitor Preferences for Vegetation – An On-site Qualitative Research Study. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET 2021, 3, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, D.I.; Collopy, J.J.; Beadle, C.L.; Baker, T.G. Effect of Thinning, Pruning and Nitrogen Fertiliser Application on Light Interception and Light-Use Efficiency in a Young Eucalyptus Nitens Plantation. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 288, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Di, X.; Chang, S.X.; Jin, G. Stand Density and Species Richness Affect Carbon Storage and Net Primary Productivity in Early and Late Successional Temperate Forests Differently. Ecol. Res. 2016, 31, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Jin, G. Impacts of Stand Density on Tree Crown Structure and Biomass: A Global Meta-Analysis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 326, 109181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, T.H.; Shakoor, A.; Rashid, M.H.U.; Zhang, S.; Wu, P.; Yan, W. Annual Growth Progression, Nutrient Transformation, and Carbon Storage in Tissues of Cunninghamia Lanceolata Monoculture in Relation to Soil Quality Indicators Influenced by Intraspecific Competition Intensity. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 3146–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochhead, K.D.; Comeau, P.G. Relationships between Forest Structure, Understorey Light and Regeneration in Complex Douglas-Fir Dominated Stands in South-Eastern British Columbia. For. Ecol. Manage. 2012, 284, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, H.; Hein, S. Effect of Wide Spacing on Increment and Branch Properties of Young Norway Spruce. Eur. J. For. Res. 2006, 125, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, Q.; Gao, D.; Zhang, B.; Zuo, H.; Jiang, J. Effects of Thinning and Understory Removal on the Soil Water-Holding Capacity in Pinus Massoniana Plantations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razafindrabe, B.H.N.; He, B.; Inoue, S.; Ezaki, T.; Shaw, R. The Role of Forest Stand Density in Controlling Soil Erosion: Implications to Sediment-Related Disasters in Japan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 160, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, Z. Photosynthetic Carbon Fixation Capacity of Black Locust in Rapid Response to Plantation Thinning on the Semiarid Loess Plateau in China. Pakistan J. Bot. 2019, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaglia, E.S.; Aronson, M.F.J. Plant Native: Comparing Biodiversity Benefits, Ecosystem Services Provisioning, and Plant Performance of Native and Non-Native Plants in Urban Horticulture. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 2587–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, J.; Bartholomeus, H.; Janssen, S.; Calders, K.; Wuyts, K.; Van Wittenberghe, S.; Samson, R. Influence of Tree Crown Characteristics on the Local PM 10 Distribution inside an Urban Street Canyon in Antwerp (Belgium): A Model and Experimental Approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, D.; Stape, J.L.; Ryan, M.G. Thinking about Efficiency of Resource Use in Forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2004, 193, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.; Gillner, S.; Hofmann, M.; Tharang, A.; Dettmann, S.; Gerstenberg, T.; Schmidt, C.; Gebauer, H.; Van de Riet, K.; Berger, U.; et al. Citree: A Database Supporting Tree Selection for Urban Areas in Temperate Climate. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, Y.; Kim, D.; Son, S.; Kim, E.J. Carbon Storage and Sequestration Analysis by Urban Park Grid Using I-Tree Eco and Drone-Based Modeling. Forests 2024, 15, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, O.; Komlyk, Y.; Tutova, H.; Zhukov, O. Landscape Diversity Mapping Allows Assessment of the Hemeroby of Bird Species in a Modern Industrial Metropolis. Biosyst. Divers. 2024, 32, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwel, M.C.; Lopez, E.L.; Sprott, A.H.; Khayyatkhoshnevis, P.; Shovon, T.A. Using Aerial Canopy Data from UAVs to Measure the Effects of Neighbourhood Competition on Individual Tree Growth. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 461, 117949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, E.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Rahman, M.; Pauleit, S.; Pretzsch, H.; Rötzer, T. Crown Shapes of Urban Trees-Their Dependences on Tree Species, Tree Age and Local Environment, and Effects on Ecosystem Services. Forests 2022, 13, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yu, K.; Zeng, X.; Lin, Y.; Ye, B.; Shen, X.; Liu, J. How Can Urban Parks Be Planned to Mitigate Urban Heat Island Effect in “Furnace Cities” ? An Accumulation Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jin, S.; Du, P. Roles of Horizontal and Vertical Tree Canopy Structure in Mitigating Daytime and Nighttime Urban Heat Island Effects. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 89, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lv, Y.; Pan, H. Cooling and Humidifying Effect of Plant Communities in Subtropical Urban Parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykytiuk, Y.; Kravchenko, O.; Komorna, O.; Bambura, V.; Seredniak, D. Spatial and Temporal Variation of the Rainfall Erosivity Factor in Polissya and Forest-Steppe of Ukraine. Biosyst. Divers. 2024, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.G. Tamm Review: Leaf Area Index (LAI) Is Both a Determinant and a Consequence of Important Processes in Vegetation Canopies. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 477, 118496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, R.; Luo, Q.; Yang, Y. Estimating the Leaf Area Index of Urban Individual Trees Based on Actual Path Length. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutova, H.; Lisovets, О.; Kunakh, O.; Zhukov, O. The Future of the Kakhovka Reservoir after Ecocide: Afforestation and Ecosystem Service Recovery through Emergent Willow-Popular Communities. Stud. Biol. 2025, 19, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Rötzer, T.; Pauleit, S.; Pretzsch, H. Structure and Ecosystem Services of Small-Leaved Lime (Tilia Cordata Mill.) and Black Locust (Robinia Pseudoacacia L.) in Urban Environments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoszko, K.; Ruiz Gómez, F.J.; Lazzaro, L.; Lora González, Á.; González-Moreno, P. Diversity Patterns of Herbaceous Community in Environmental Gradients of Dehesa Ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 54, e03162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunakh, O.M.; Ivanko, I.A.; Holoborodko, K.K.; Lisovets, O.I.; Volkova, A.M.; Zhukov, O.V. Urban Park Layers: Spatial Variation in Plant Community Structure. Biosyst. Divers. 2022, 30, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, E.; Cortez, J.; Billès, G.; Navas, M.-L.; Roumet, C.; Debussche, M.; Laurent, G.; Blanchard, A.; Aubry, D.; Bellmann, A.; et al. Plant Functional Markers Capture Ecosystem Properties during Secondary Succession. Ecology 2004, 85, 2630–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-M.; Zerbe, S.; Kowarik, I. Human Impact on Flora and Habitats in Korean Rural Settlements | Vliv Lidské Činnosti Na Stanoviště Korejských Vesnic a Jejich Flóru. Preslia 2002, 74, 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kunakh, O.; Lisovets, O.; Podpriatova, N.; Zhukov, O. Plant Community Hemeroby Is a Reliable Indicator of the Dynamics of Reclamation of Lands Disturbed by Mining. Ekológia (Bratislava) 2024, 43, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, N.W.H.; Mouillot, D.; Lee, W.G.; Wilson, J.B. Functional Richness, Functional Evenness and Functional Divergence: The Primary Components of Functional Diversity. Oikos 2005, 111, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villéger, S.; Mason, N.W.H.; Mouillot, D. New Multidimensional Functional Diversity Indices for a Multifaceted Framework in Functional Ecology. Ecology 2008, 89, 2290–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O.; Roy, D.B.; Thompson, K. Hemeroby, Urbanity and Ruderality: Bioindicators of Disturbance and Human Impact. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002, 39, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, A.; De Nicola, C.; Dowgiallo, G.; Fanelli, G. Correspondences between Plants and Soil/Environmental Factors in Beech Forests of Central Apennines: From Homogeneity to Complexity. Rend. LINCEI 2010, 21, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-C.; Liu, X.-Y. Plant Nitrogen-Use Strategies and Their Responses to the Urban Elevation of Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition in Southwestern China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 311, 119969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, X.; Vries, W. Ecological Effects of Nitrogen Deposition on Urban Forests: An Overview. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliere, J.M.; Bucciarelli, G.M.; Bytnerowicz, A.; Fenn, M.E.; Irvine, I.C.; Johnson, R.F.; Allen, E.B. Declines in Native Forb Richness of an Imperiled Plant Community across an Anthropogenic Nitrogen Deposition Gradient. Ecosphere 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tree stand parameter | Park | Total (N = 380) |

Test | P-value | |

| Ivan Starov Square (N = 150) | Students’ Park (N = 230) |

||||

| Tree number per sample plot | 2.0±1.2 | 2.7±1.6 | 2.4±1.5 | Mann-Whitney | < 0.001 |

| Tree stand Shannon diversity | 0.9±0.6 | 0.9±0.6 | 0.9±0.6 | Student’s t-test | 0.68 |

| Cover, % | 51.7±19.9 | 51.5±26.0 | 51.6±23.7 | Student’s t-test | 0.93 |

| Canopy openness, % | 57.0±17.4 | 27.5±13.4 | 39.1±20.9 | Student’s t-test | < 0.001 |

| Leaf area index (LAI) | 0.9±0.6 | 2.1±0.8 | 1.6±0.9 | Student’s t-test | < 0.001 |

| Transparency (direct) | 5.1±3.9 | 4.4±2.9 | 4.7±3.3 | Student’s t-test | 0.044 |

| Transparency (diffuse) | 5.4±3.7 | 4.1±2.4 | 4.6±3.0 | Student’s t-test | < 0.001 |

| Transparency (total) | 10.5±7.3 | 8.5±4.9 | 9.3±6.1 | Student’s t-test | 0.002 |

| Variable | Factor loadings | Dimensions, derived from the results of nonmetric multidimensional scaling | ||||

| PC1, λ = 4.9 |

PC2, λ = 1.8 |

NMDS 1 | NMDS 2 | NMDS 3 | NMDS 4 | |

| Soil temperature (log-transformed) | 0.88 | – | 0.35 | 0.24 | –0.27 | – |

| Soil moisture (log-transformed) | –0.82 | – | –0.20 | –0.12 | 0.29 | – |

| Soil electric conductivity | –0.56 | – | – | – | 0.15 | – |

| Lighing (log-transformed) | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.25 | –0.19 | 0.10 |

| Air temperature | 0.91 | – | 0.31 | 0.26 | –0.34 | – |

| Air humidity | –0.90 | – | –0.34 | –0.26 | 0.33 | – |

| Grass height | –0.46 | 0.66 | – | – | 0.23 | – |

| Herbaceous cover | – | 0.80 | 0.24 | – | – | 0.16 |

| Hemeroby | 0.84 | – | 0.27 | 0.21 | –0.38 | – |

| Naturalness | – | –0.40 | –0.15 | – | 0.11 | – |

| Herb species richness | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.36 | – | – | 0.27 |

| PC1 | – | – | 0.36 | 0.22 | –0.35 | – |

| PC2 | – | – | 0.49 | – | – | 0.46 |

| Trait | Test | Functional axes | ||||

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | ||

| Leaf area | Linear Model | –0.32 | –0.58 | – | – | – |

| Leaf area per leaf dry mass | Linear Model | – | – | 0.49 | –0.29 | –0.40 |

| Leaf dry mass per leaf fresh mass | Linear Model | –0.58 | – | –0.34 | – | – |

| Leaf nitrogen (N) content per leaf dry mass | Linear Model | 0.47 | –0.21 | 0.28 | –0.49 | – |

| Plant height | Linear Model | – | – | – | –0.65 | 0.44 |

| Beginning of flowering period | Linear Model | 0.35 | – | – | – | 0.65 |

| End of flowering | Linear Model | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.30 | – | – |

| Time of seed dispersal | Linear Model | 0.25 | – | – | – | 0.28 |

| Seed mass | Linear Model | –0.31 | –0.51 | – | – | – |

| Dispersal distance class | Linear Model | 0.58 | –0.57 | –0.18 | – | – |

| Seedbank duration | Linear Model | 0.76 | 0.23 | – | – | – |

| Light regime | Linear Model | 0.65 | 0.44 | – | – | 0.20 |

| Temperatures | Linear Model | – | –0.41 | –0.39 | 0.34 | – |

| Continentality of climate | Linear Model | 0.30 | 0.36 | – | 0.22 | – |

| Humidity | Linear Model | –0.41 | –0.23 | – | –0.63 | – |

| Acidity | Linear Model | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nutrients availability | Linear Model | – | –0.21 | 0.28 | –0.73 | – |

| Naturalness | Linear Model | –0.76 | –0.19 | 0.20 | – | – |

| Hemeroby | Linear Model | 0.84 | 0.21 | –0.24 | – | – |

| Climamorph | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.29 | – | 0.41 |

| Pollenochor | Kruskal-Wallis | – | 0.15 | 0.57 | 0.12 | – |

| Diasporochor | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.06 | 0.63 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).