1. Introduction

The Mediterranean deep sea has long been considered stable in terms of its physical-chemical and hydrographical conditions [

1,

2]. However, the basin has experienced environmental changes over time and across different areas, affecting the demographic structure and biology of marine species [

2,

3,

4]. Understanding biotic aspects at depths of 200 to 2000 m requires awareness of the factors regulating this environment, and describing general patterns is not straightforward. Consequently, an increasing number of scientists have focused their research on deep-sea ecosystems in the last decade, mainly concerning fishery resources [

5,

6,

7]

The Levantine basin has traditionally been regarded as an area with low diversity of deep-water fauna [

8], although this hypothesis has always been considered weak due to the inaccessibility of the habitat, which limited sampling efforts [

1]. Recent data have expanded previous knowledge by focusing on different taxa and extending vertical sampling to greater depths [

9].

A specific survey targeting the deep-sea amphipod fauna, which remains poorly understood [

10,

11], was conducted in the Mediterranean Israeli waters to enhance knowledge of this habitat and taxon.

Deep-sea amphipod biodiversity data are sporadic, especially in the Mediterranean Sea [

11], where the deep habitats are less interconnected than in the open oceans, owing to geomorphological features shaped by sills that separate the main deep zones, such as the western and eastern basins. This separation could lead to biogeographical differences among sectors.

Deep-sea amphipods are not rare; they occupy all depths along the water column and even reach the hadal environment, with some Lysianassoideans collected at around 10,000 m [

12].

Food availability is a crucial factor in shaping deep-sea benthic community structures [

7], and amphipods play a central role within these trophic networks. In hadal environments, they serve as primary prey for larger deep-sea organisms, including decapods, other predatory amphipods, and fishes [

13]. Amphipods are also effective scavengers, feeding on marine carrion that originates from both surface waters and co-occurring deep-sea species [

13]. They consume a mixture of marine detritus, indicative of a complex and cyclical organic matter transfer at these depths, demonstrating remarkable trophic plasticity [

13,

14].

This ecological flexibility highlights their importance. Notably, their capacity to ingest a wide range of materials, including anthropogenic pollutants, was demonstrated by one of the deepest recorded instances of microplastic ingestion in marine environments [

12], emphasising their potential as bioindicators of deep-sea pollution.

A previous study (1993-1996) identified twenty-two species of amphipods from samples collected at depths of 734-1558 m along the Israeli coast. This paper presents data collected twenty years later, with samples gathered in 2013 at depths of 198-1812 m. The bathymetric distribution of amphipods was analysed to improve understanding of this taxon’s distribution and its temporal changes.

2. Materials and Methods

The area investigated is located off the northern coast of Israel. The samples were collected in 2013 at depths between 198 and 1812 m, from 20 sites (

Table 1). They were collected using a 0.5 mm plankton net secured atop a Marinovichtype deep water trawl, and by a 0.062 m2 box-corer with an effective penetration of 40 cm (Ocean Instruments model 700 AL). Each sample was preserved in 10% buffered formalin aboard the ship. In the laboratory, samples were washed and sieved through a 500 ¹mm mesh, preserved in 70% alcohol, and stained in Rose Bengal. The samples were collected using a 0.062 m and 0.025 m boxcorer with an effective penetration of 40 cm (Ocean Instruments model 700 AL) [

15] (pp. 2-3). Each sample was preserved in 10% buffered formalin aboard the ship. In the laboratory, samples were washed and sieved through a 500 ¹m mesh, preserved in 70% alcohol, and stained in Rose Bengal. The dataset integrated a previous investigation, carried out in the period between 1993 and 1996 [

16], twenty years before the presented data. The prior survey collected twenty-two amphipod species at depths ranging from 734 to 1558 m.

3. Results

A total of 127 specimens belonging to 12 amphipod species and 8 families were collected from 16 sites, at depths between 198 and 1812 m, along the Israeli coast (

Table 1).

Carangoliopsis spinulosa,

Harpinia crenulata and

Harpinia antennaria were the most abundant species, respectively 55%, 17% and 13% of total abundance. Of the twelve species recorded, seven were new records for the Israeli coast that represented the 94% of the total abundance of this survey (

Ampelisca jaffaensis, Carangoliopsis spinulosa, Westwoodilla caecula, Harpinia antennaria, Harpinia crenulata, Harpinia pectinata, Paraphoxus oculatus) (

Table 1). Of these,

W. caecula,

H. antennaria and P. oculatus were new records for the Levantine basin.

Herein, the first record of two families in the deep-sea layers of the Israeli coast is highlighted, Ampeliscidae Krøyer, 1842 and Carangoliopsidae Bousfield, 1977.

About the new records, these were collected in twelve sites at depths between 198 and 1122 m. Ampelisca jaffaensis was found in two sites respectively at depth of 214 and 1122 m with eight specimens; C. spinulosa in nine sites in a depth range between 198 and 1122 m with seventy specimens; W. caecula was found in only one site at the depth of 994 m with one specimen; H. antennaria was fond in six sites a depth range of 198 to 1122 m with seventeen specimens; H. crenulate was found in only one site at a depth of 1122 m with twenty-two specimens; H. pectinata was found in only one site at a depth of 682 m with one specimen; and P. oculatus was found in only one site at a depth of 1122 m with one specimen.

The most relevant result was the discrepancy with the assemblage detected by Sorbe and Galil (2002). Some families, previously found, were absent – Lepechinellidae Schellenberg, 1926; Liljeborgiidae Stebbing, 1899; Stegocephalidae Dana, 1852; Tryphosidae Lowry & Stoddart, 1997; Uristidae Hurley, 1963 – whereas the presence of some families was confirmed – Eusiridae Stebbing, 1888; Leucothoidae Dana, 1852; Oedicerotidae Lilljeborg, 1865; Pardaliscidae Boeck, 1871; Phoxocephalidae G.O. Sars, 1891; Synopiidae Dana, 1853.

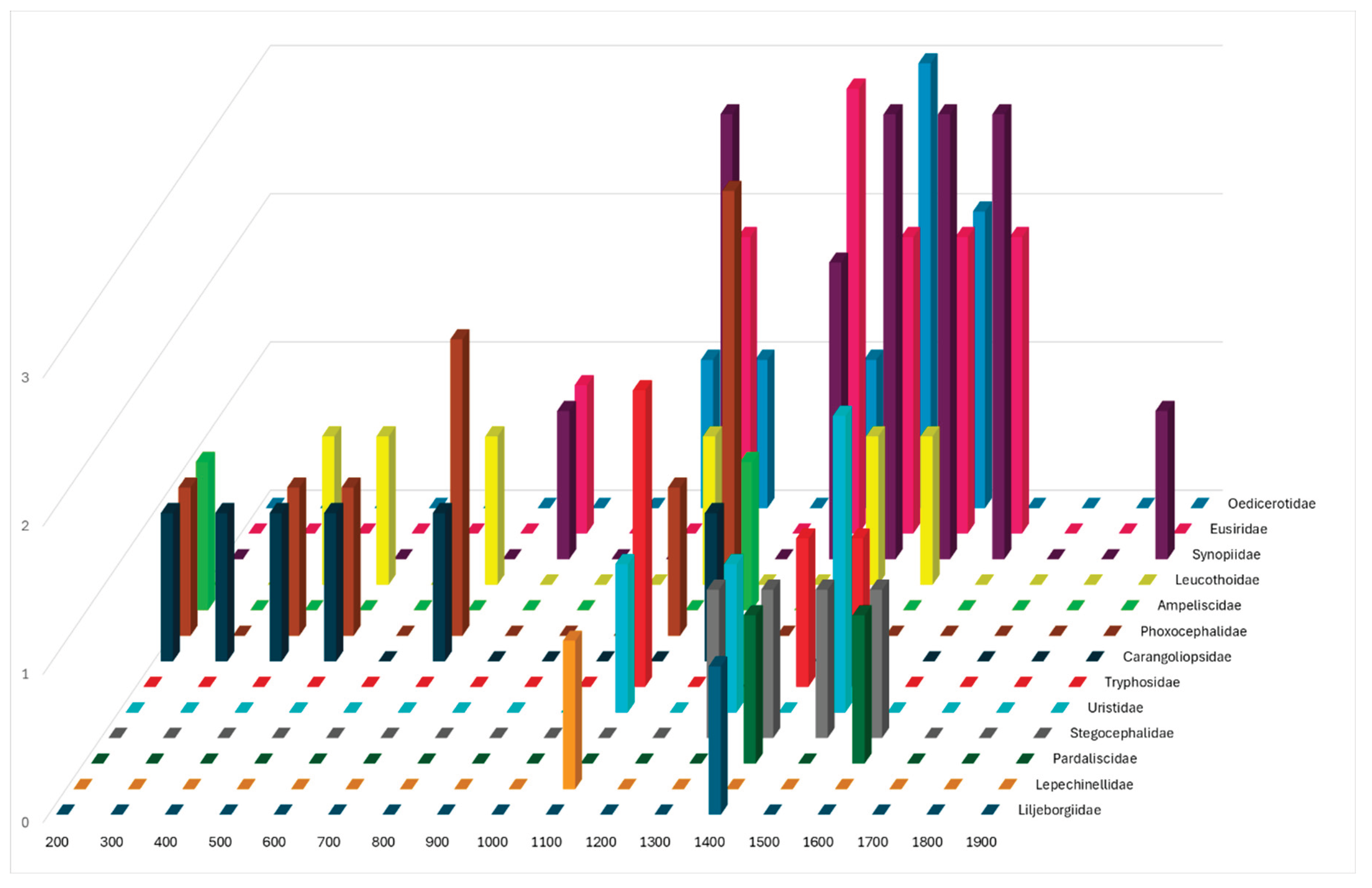

Figure 1 shows the number of species per family collected at various depth ranges in both surveys. Some families, such as Pardaliscidae (1400-1600 m) and Uristidae (1100-1500 m), occurred in a restricted depth range.

The sites with major species richness and abundance were at depth between 1000 and 1400 m respectively: 1000 m with thirteen species and 8,5% of total abundance; 1110 m with five species and 5,9% of total abundance; 1350 m with twelve species and 14,7% of total abundance; 1400 m with fourteen species and 26,3% of total abundance; 1450 m with ten species and 18,8% of total abundance; and 1500 m with six species and 6,7% of total abundance, 1550 m with six species and 2,2% of total abundance,

In this last survey, the sites with major species richness and abundance were at 1122 m with five species and 48% of total abundance; and in sites at 400 m and 200 m respectively with two species both and 20% and 28% of the total abundance.

It emerges that some genera, already reported [

16], were maintained with a different species composition. The genus

Rhachotropis, previously reported with three species [

16], was maintained with

Rhachotropis caeca, missing

R. grimaldii and

R. rostrata . The genus

Harpinia, previously reported with a single species, was found as

Harpinia antennaria, Harpinia crenulata, and

Harpinia pectinata (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

The Levantine basin was regarded as an area with low diversity and low-density deep water fauna [

18]. A unique previous investigation of Israeli amphipod fauna for this peculiar and inaccessible ecosystem was published in 2002, based on material collected from 1993 to 1996 at depths between 734 and 1558 m [

16]. The survey documented twenty-two deep-sea amphipod species, of which twenty-one, at that time, were new records for the area [

16].

The present paper enhances knowledge of deep-sea amphipods' bathymetric distribution and includes new records. Eight species were new for the Israeli coast (

Ampelisca jaffaensis, Carangoliopsis spinulosa, Westwoodilla caecula, Harpinia antennaria, Harpinia crenulate, Harpinia dellavallei, Harpinia pectinata, Paraphoxus oculatus) (

Table 2).

Some families, commonly inhabiting coastal waters, were confirmed to extend into deep waters. These families – Leucothoidae Dana, 1852, Oedicerotidae Lilljeborg, 1865 and Phoxocephalidae G.O. Sars, 1891 – were previously found in the abyssal zone [

16,

19] and occurred respectively up to 1433 m, 1456 m, and 1300 m.

The first records of the families Ampeliscidae Krøyer, 1842 and Carangoliopsidae Bousfield, 1977 in the Israeli deep-sea layers were collected at 1122 m.

Given the low mobility of benthic amphipods, it would be expected that the amphipod assemblage in the Levantine area remains relatively constant over time. However, the most notable result from this dataset is the discrepancy between the assemblage identified by Sorbe and Galil [

16] and the composition presented here; some families and several species previously recorded were absent, while others were observed for the first time (

Table 1).

It is noteworthy that the entire dataset provides an overview of amphipod fauna occurrence across depth ranges (

Figure 1). The species richness did not increase with depth, as the highest density of species was observed between 1000 and 1600 m. This observation warrants further investigation into future sampling plans.

Ruffo [

19] identified nearly 150 Mediterranean species with a bathymetric zone reaching into the deep-sea, of which 63 occur solely below 150 m. Such information has not been thoroughly revised and only approximately synthesized by subsequent studies.

The recent revision of the Mediterranean amphipod fauna includes almost 650 species [

20], i.e., about 6% of the worldwide marine amphipod fauna [

21]. The deep-sea Mediterranean amphipods should constitute 10% of the inhabitants of the basin.

Records of deep-sea species in the Mediterranean are based on old material resumed by recent checklists [

11,

22]. The first study [

11] further reported new records of eight species from three stations in the southern Mediterranean, at depths between 2415 and 2626 m:

Bathymedon acutrifrons Bonnier, 1896 and

B. banyulensis Ledoyer, 1982;

Harpinia dellavallei;

Monoculodes packardi Boeck, 1871;

Pardalisca mediterranea Bellan-Santini, 1985;

Rhachothrapis caeca;

Scopelocheirus polymedus Bellan-Santini, 1985 and

Syrrhoides cornuta Bellan-Santini, 1985.

Of the twenty-eight species herein documented along the coasts of Israel, twenty-two exhibit an Atlanto-Mediterranean distribution, two are cosmopolitan, and the remaining five are endemic to the Mediterranean Sea (

Table 3).

All species have been reported from both the Western Mediterranean and the Levantine Basin, although several displayed a discontinuous distribution along an imaginary west-east Mediterranean axis [

11,

16,

17,

22,

23]. Excluding the Adriatic Sea, a basin not exceeding 200 meters depth, species like

Ampelisca jaffaensis,

Bathymedon monoculodiformis,

Oediceropsis brevicornis,

Bruzelia typica,

Pseudotiron bouvieri,

Tryphosites alleni,

Caeconyx caeculus, and

Tmetonyx similis—species previously recorded by Sorbe & Galil [

16]—showed a disjointed distribution. (

Table 3).

No studies have reported temporal analyses of the Mediterranean deep-sea amphipods, nor along the Israeli coast.

The temporal variation in amphipod fauna is not easy to detect, as the physical features of the sediment play a crucial role in shaping amphipod assemblage structure [

24]. A prior study [

24] conducted a spatio-temporal analysis of amphipod crustaceans collected from soft-bottom habitats along the Israeli Mediterranean coast between 2010 and 2017. This was part of a long-term national monitoring program assessing changes in benthic macrofauna and the impact of environmental factors in this ecologically vulnerable region. Amphipod assemblages reflected sediment characteristics and human impacts, with no significant temporal shifts [

24].

Regarding the discrepancy between the assemblage reported by Sorbe and Galil [

16] and the community composition documented in the present study, limited information on sampling efforts prevents definitive conclusions, but it could be hypothesized that certain factors could have influenced such a change.

In the Levantine basin, the continental shelf is predominantly narrow, bringing slopes and deep-sea habitats close to the coast, thus making them highly vulnerable to terrestrial influences [

8,

25]. As a result, factors shaping deep-sea benthic communities in the area must consider riverine inputs, sedimentation, water column mixing, and various anthropogenic pressures such as pollution from urbanization, agriculture, maritime transport, industrial and municipal discharges, and tourism [

2,

8]. Furthermore, natural processes like flash flooding, cascading of dense shelf waters, and submarine landslides also play crucial roles in structuring these ecosystems, rendering the deep-sea habitat sensitive to climate change [

3].

In light of such consideration, deep sea amphipods could play a pivotal role in elucidating ecological mechanisms or unpredictable phenomena in the marine environment. The ecological role of amphipods is fundamental within marine ecosystems, owing to their high taxonomic and functional diversity. As an umbrella taxon, amphipods provide valuable insights into the structure and functioning of benthic communities, making their study essential for understanding ecosystem balance and resilience [

26,

27]. Furthermore, their wide ecological distribution and sensitivity to environmental variation render amphipods an ideal model group for assessing changes in deep-water habitats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and D.I.; formal analysis, S.L., D.I., H.L.; resources, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.I.; writing—review and editing, supervision, S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project partially funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4 - NextGenerationEU. Award Number: Project code CN_00000033, adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP B73C22000790001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center - NBFC”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Danovaro, R.; Company, J.B.; Corinaldesi, C.; D'Onghia, G.; Galil, B.; Gambi, C.; ...; Tselepides, A. Deep-sea biodiversity in the Mediterranean Sea: the known, the unknown, and the unknowable. PloS One 2010, 5(8), e11832.

- Lejeusne, C.; Chevaldonné, P.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Boudouresque, C. F.; Pérez, T. Climate change effects on a miniature ocean: the highly diverse, highly impacted Mediterranean Sea. Trends Ecol Evol 2010, 25(4), 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danovaro, R.; Dell'Anno, A.; Fabiano, M.; Pusceddu, A.; Tselepides, A. Deep-sea ecosystem response to climate changes: the eastern Mediterranean case study. Trends Ecol Evol 2001, 16(9), 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, J. B.; Puig, P.; Sarda, F.; Palanques, A.; Latasa, M.; Scharek, R. Climate influence on deep sea populations. PLoS One 2008, 3(1), e1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danovaro, R.; Dell'Anno, A.; Pusceddu, A. Biodiversity response to climate change in a warm deep sea. Ecol Lett. 2004, 7(9), 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, T.; Lo Brutto, S.; Cannas, R.; Deiana, A. M.; Arculeo, M. Environmental features of deep-sea habitats linked to the genetic population structure of a crustacean species in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. 2009, 30(3), 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselepides, A.; Sevastou, K.; Lampadariou, N. Environmental factors influencing the benthic ecology of the deep Eastern Mediterranean Sea–A review. Deep-Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2023, 202, 104177.

- Kröncke, I.; Turkay, M.; Fiege, D. Macrofauna communities in the Eastern Mediterranean deep sea. P.S.Z.N. Mar. Ecol. 2003, 24 (3): 193–216.

- Albano, P.G.; Azzarone, M.; Amati, B.; Bogi, C.; Sabelli, B.; Rilov, G. Low diversity or poorly explored? Mesophotic molluscs highlight undersampling in the Eastern Mediterranean. Biodivers Conserv 2020, 29(14), 4059–4072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Barranco, C.; Ros, M.; de Figueroa, J.M.T.; Guerra-García, J.M. Marine crustaceans as bioindicators: Amphipods as case study. Fish. Aquac. 2020, 9, 435–463. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalem, A.; Dauvin, J.C.; Menioui, M. Diversity of marine Amphipods (Crustacea, Peracarida) from the North African shelf of the Mediterranean Sea (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt). An updated checklist for 2023. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2024, 25(2), 311–373. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, A.J.; Brooks, L.S.R.; Reid W.D.K.; Piertney, S.B.; Narayanaswamy, B.E.; Linley, T.D. Microplastics and synthetic particles ingested by deep-sea amphipods in six of the deepest marine ecosystems on Earth. R. Soc. Open sci. 2019, 6: 180667. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, A.J.; Lörz, A.N.; Fujii, T.; Priede, I.G. In situ observations of trophic behaviour and locomotion of Princaxelia amphipods (Crustacea: Pardaliscidae) at hadal depths in four West Pacific Trenches. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U.K. 2012, 92, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, L.E.; Levin, L.A. Extreme food webs: foraging strategies and diets of scavenging amphipods from the ocean’s deepest 5 kilometers. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2007, 52.

- Lubinevsky, H.; Hyams-Kaphzan, O.; Almogi-Labin, A.; Silverman, J.; Harlavan, Y.; Crouvi, O.; ...; Tom, M. Deep-sea soft bottom infaunal communities of the Levantine Basin (SE Mediterranean) and their shaping factors. Mar. Biol. 2017, 164, 1-12.

- Sorbe, J.C.; Galil, B.S. The bathyal amphipoda off the Levantine coast, eastern Mediterranean. Crustaceana 2002, 75(8), 957-968.

- Iaciofano, D.; Lubinevsky, H.; Lo Brutto, S. First record of Carangoliopsis spinulosa Ledoyer, 1970 (Amphipoda: Carangoliopsidae) in the bathyal Israeli Mediterranean waters. Ecol. Montenegrina 2024, 78, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.S. The limit of the sea: the bathyal fauna of the Levantine Sea. Sci. Mar. 2004, 68(S3), 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, S. (Ed.) The Amphipoda of the Mediterranean. Part 4. Localities and Map. Addenda to Parts –4. Key to Families. Ecology. Faunistics and Zoogeography. Bibliography. Index. Mem. Inst. Oceanogr. (Monaco) 1998, 13, 815–959. [Google Scholar]

- Badalucco, A., Auriemma, R., Bonifazi, A., Cimmaruta, R., Esposito, V., Iaciofano, D., ... & Lo Brutto, S.. Checklist of amphipods of Italian seas: baseline for monitoring biodiversity. In MONITORING OF MEDITERRANEAN COASTAL AREAS, 2024, 2, 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Horton, T., De Broyer, C., Bellan-Santini, D., Coleman, C. O., Copilaș-Ciocianu, D., Corbari, L., ... & Zeidler, W. (2023). The World Amphipoda Database: history and progress. Records of the Australian Museum 2023, 75, issue no. 4, pp. 329–342.

- Christodoulou, M., Paraskevopoulou, S., Syranidou, E., & Koukouras, A.The amphipod (Crustacea: Peracarida) fauna of the Aegean Sea, and comparison with those of the neighbouring seas. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2013, 93(5), 1303-1327.

- Bakir, A. K., & Katağan, T. Distribution of littoral benthic amphipods off the Levantine coast of Turkey with new records. Turkish Journal of Zoology, 2014, 38(1), 23-34.

- Iaciofano, D.; Mancini, E.; Lubinevsky, H.; Lo Brutto, S. The amphipod fauna assemblage along the Mediterranean Israeli coast, a spatiotemporal overview. Ecol. Montenegrina 2024, 80: 244-272.

- Segal, Y.; Lubinevsky, H. Spatiotemporal distribution of seabed litter in the SE Levantine Basin during 2012–2021. Mar. Pollution Bull. 2023, 188, 114714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momtazi, F.; Saeedi, H. Exploring latitudinal gradients and environmental drivers of amphipod biodiversity patterns regarding depth and habitat variations. Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), 30547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, D. M.; DeJong, D.; Anteau, M. J.; Fitzpatrick, M. J.; Keith, B.; Schilling, E. G.; Thoele, B. High abundance of a single taxon (amphipods) predicts aquatic macrophyte biodiversity in prairie wetlands. Biodiversity and Conservation 2022, 31(3), 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).