Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Neurogenesis and Neuroinflammation in the Aging Brain: An Overview

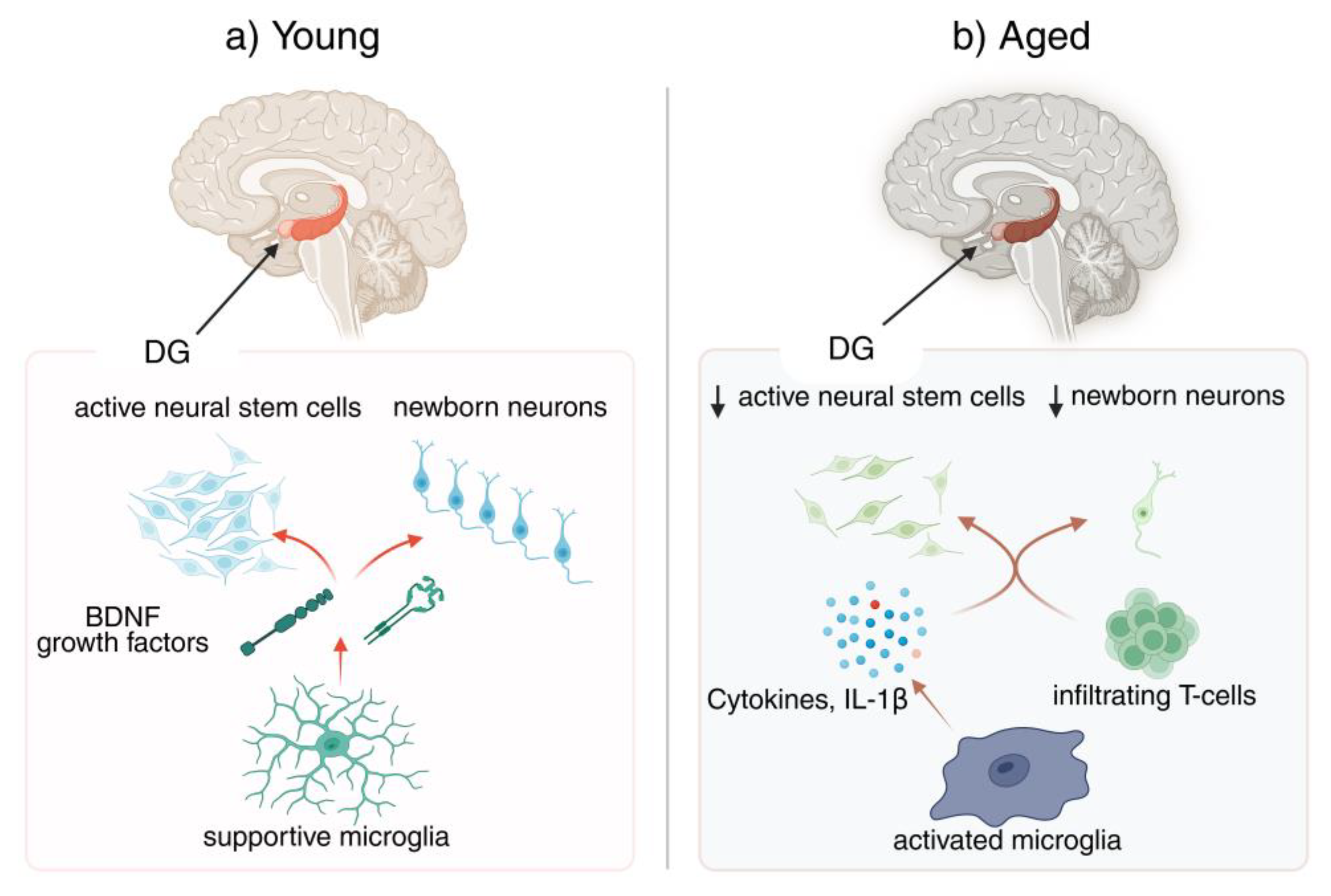

2.1. Adult Neurogenesis: Mechanisms and Age-Related Decline (~400 words)

2.2. Neuroinflammation in Aging: Microglia and Beyond

2.3. Microglia–Neural Stem Cell Crosstalk

3. Critical Gaps in Current Knowledge

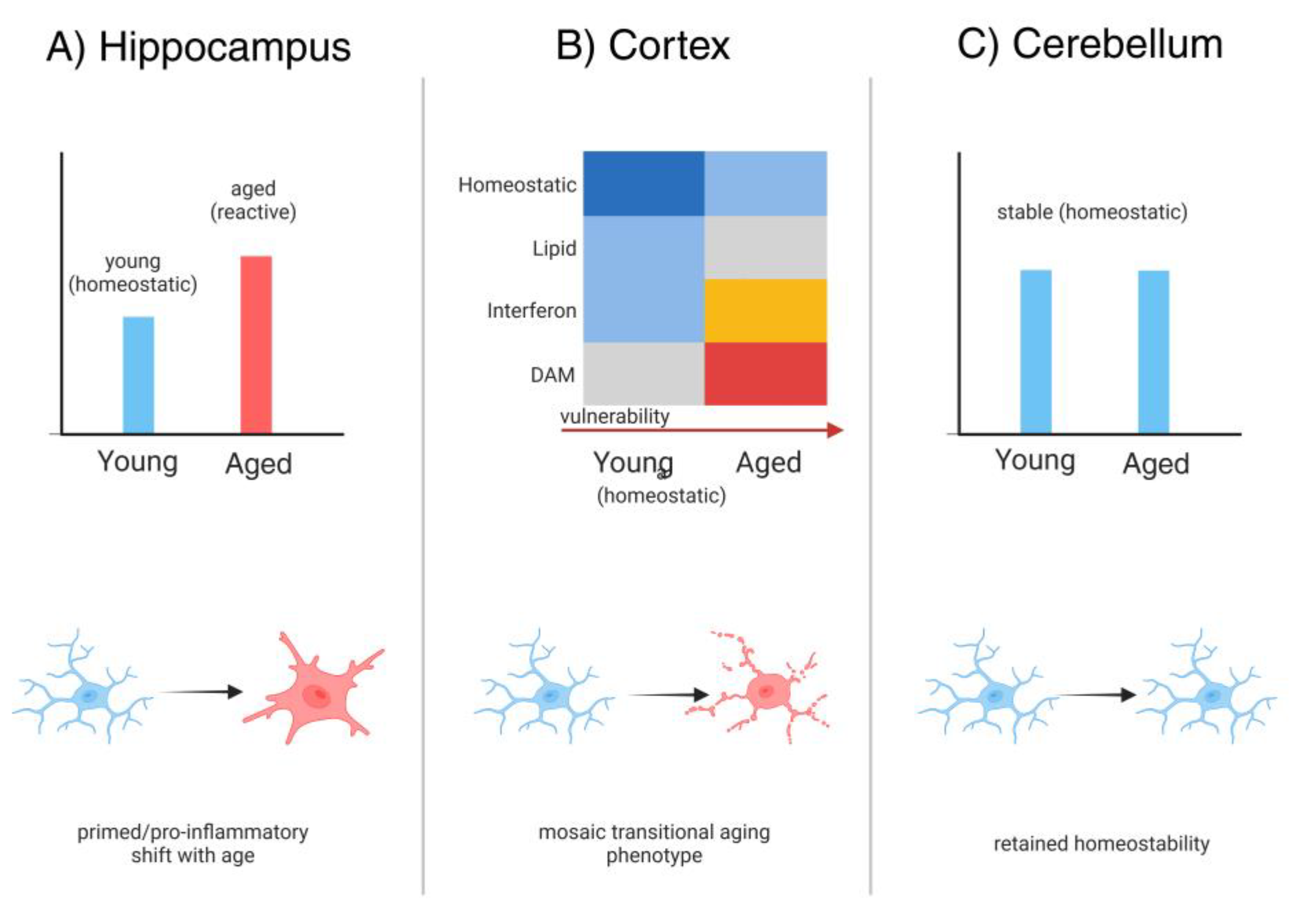

3.1. Gap 1 – Region-Specific Microglial Diversity in Aging

3.2. Gap 2 – Inflammasome-Driven Epigenetic Alterations

3.3. Gap 3 – Longitudinal Dynamics of Neuroimmune Interactions

3.4. Gap 4 – Niche-Specific Immune Mechanisms

3.5. Gap 5 – Translational and Cross-Species Disconnects

| Gap | Description of Unknown | Why it Matters / Consequences | Suggested Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Regional Microglial Diversity | Limited understanding of how microglial phenotypes differ across brain regions and influence neurogenesis | Regional vulnerabilities exist (hippocampus vs. olfactory bulb); lack of clarity hampers targeted interventions | Single-cell RNA-seq, region-specific lineage tracing, conditional microglial manipulation |

| 2. Inflammasome Dynamics in Aging | Unresolved timeline of NLRP3/other inflammasome activation in aged niches | Unclear when inflammasome priming becomes irreversible; timing critical for therapeutic window | Longitudinal transcriptomics, in vivo biosensors, inducible knockout models |

| 3. Crosstalk Between Peripheral and CNS Immunity | Mechanisms of how peripheral T cells and cytokines reshape neurogenic niches remain obscure | Infiltrating T cells alter NSC fate; missing mechanistic detail limits translation to systemic therapies | Fate-mapping of immune infiltration, parabiosis, targeted blockade of adhesion molecules |

| 4. Beneficial vs. Detrimental Microglial States | Poorly defined markers distinguishing pro-neurogenic vs. antineurogenic microglial states | Current therapies risk indiscriminate immunosuppression; need precision immunomodulation | Multi-omics integration (proteome, epigenome), machine-learning-based state classification, microglia-specific drug screens |

| 5. Non-coding RNA & Extracellular Vesicle Signaling | Roles of EV cargo (miRNAs, lncRNAs) in regulating neurogenesis under inflammation are underexplored | Missed therapeutic opportunities; EVs may carry both detrimental and reparative signals | High-resolution EV profiling, CRISPR-based RNA manipulation, engineered EV delivery systems |

4. Strategies and Emerging Approaches to Bridge the Gaps

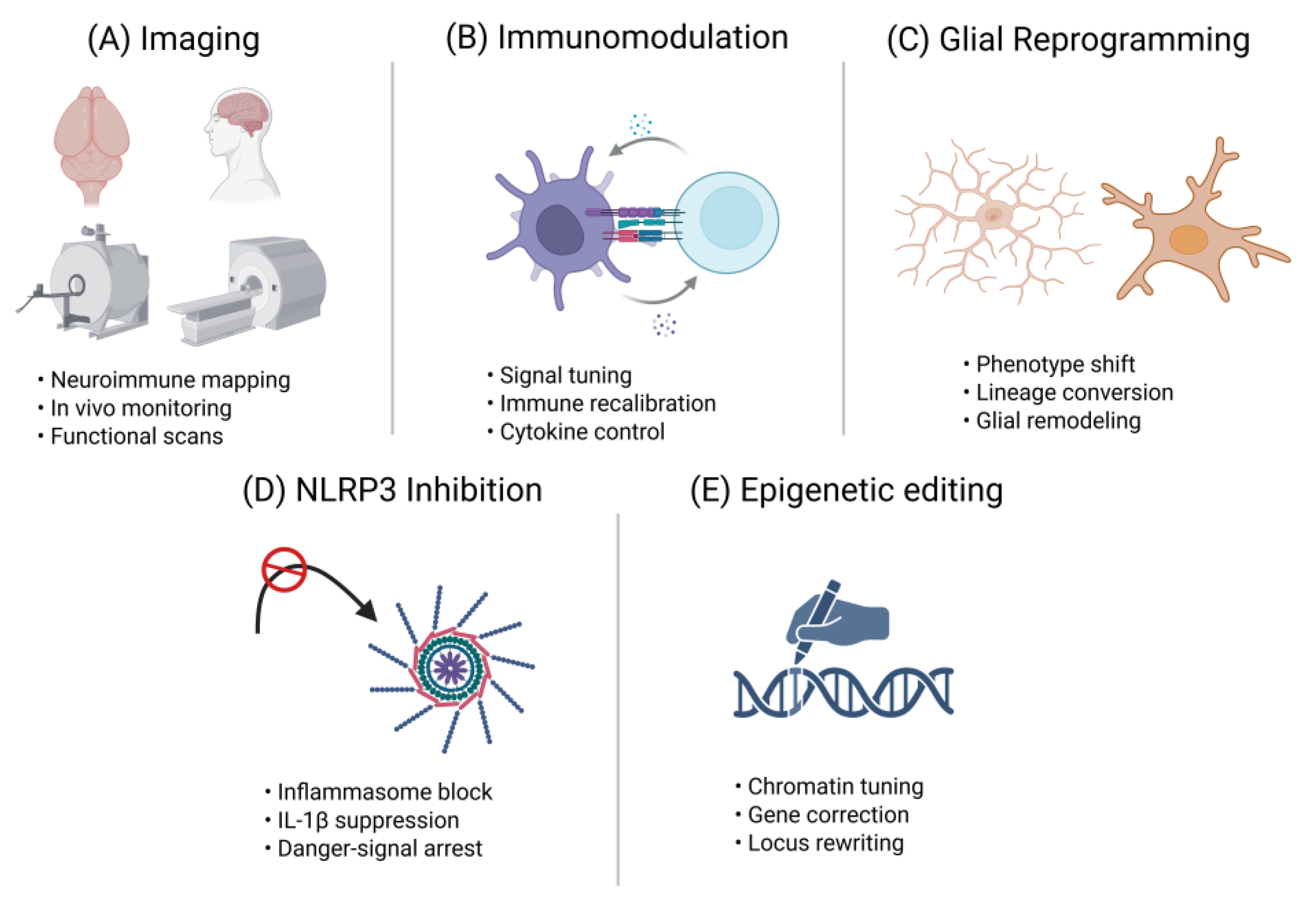

4.1. Longitudinal Neuroimmune Imaging

4.2. Niche-Focused Immunomodulation

4.3. Glial Subtype Reprogramming

4.4. Brain-Penetrant NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors

4.5. CRISPR-Based Epigenetic Editing

| Strategy | Examples / Tools | Goal / Effect | Stage of Development |

| Longitudinal Imaging | [^18F]FLT-PET for neurogenesis, TSPO-PET for microglial activation | Enables in vivo monitoring of neurogenesis and neuroinflammation across lifespan | Preclinical for neurogenesis tracers; TSPO-PET in human use |

| Brain-Penetrant NLRP3 Inhibitors | MCC950, NT-0796, BGE-102 | Reduce chronic IL-1β release, restore neurogenic potential | Preclinical to Phase 1 clinical trials |

| Glial Reprogramming | AAV-NeuroD1, SOX2-based astrocyte-to-neuron conversion | Replace lost neurons; rejuvenate circuits | Proof-of-concept in rodents |

| CRISPR Epigenetic Editing | CRISPR-dCas9 targeting IL-1β/NLRP3 loci; enhancer repression | Long-term silencing of pro-inflammatory genes without DNA cleavage | Lab-stage; in vitro and early in vivo |

| Niche Immunomodulation | Anti-IL-1β, anti-TNF, IL-6R antibodies; microglia-specific modulators | Dampens chronic inflammation in neurogenic niches | Several agents in AD, MCI, depression trials |

| Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Therapeutics | Engineered EVs carrying miRNAs, BDNF, or IGF-1 cargo | Deliver pro-neurogenic and anti-inflammatory signals | Preclinical; first-in-human safety studies emerging |

| Lifestyle & Activity-Based Interventions | Exercise, enriched environment, caloric modulation | Boost endogenous IGF-1/BDNF, reduce inflammatory priming | Multiple human cohort studies and ongoing clinical trials |

| Small-Molecule Neurotrophic Enhancers | TrkB agonists, phosphodiesterase inhibitors | Enhance BDNF signaling, promote synaptic/neurogenic resilience | Early-stage clinical testing, mixed outcomes |

| Microglial State Modulation | CSF1R inhibitors, TREM2 agonists | Shift microglia from pro-inflammatory to reparative states | Preclinical; TREM2 antibodies in Phase 2 AD trials |

| Combinatorial Approaches | NLRP3 inhibitor + exercise; anti-TNF + BDNF mimetics | Target multiple axes (inflammatory and trophic) simultaneously | Conceptual and early preclinical testing |

5. Comparative Perspectives: Human vs. Animal Models

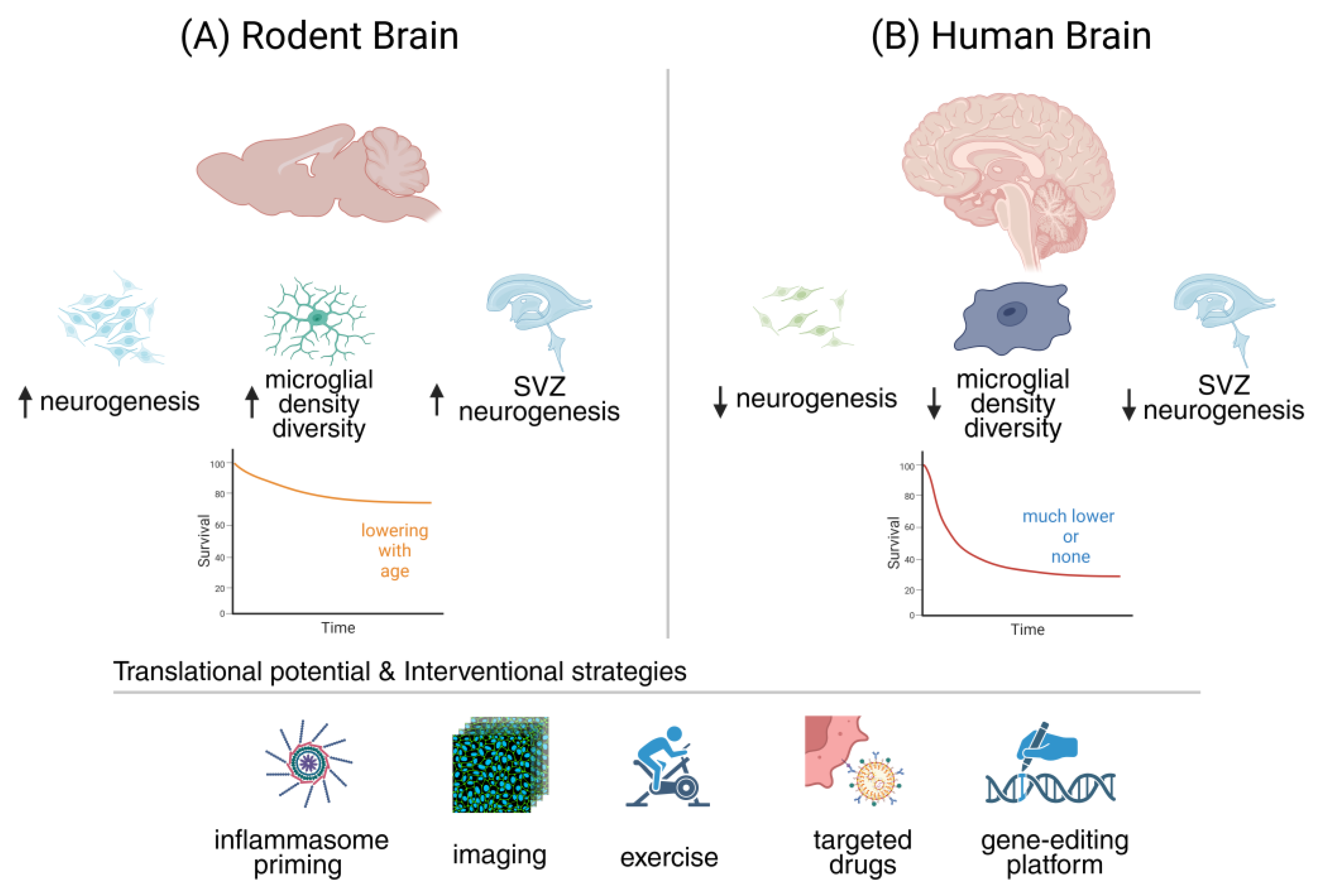

5.1. Adult Neurogenesis: Rodents vs. Humans

5.2. Microglial States Across Species

5.3. Inflammatory Pathways and Neuroimmune Crosstalk

5.4. Intervention Efficacy and Translational Readiness

5.5. Bridging the Gap: Models, Ethics, and Future Outlook (≈150–180 Words)

| Aspect | Rodents (Murine) | Humans |

| Adult hippocampal neurogenesis (baseline) | Thousands of new neurons per day in young adult hippocampus; robust measurable pools | Far fewer (hundreds/day in young adults by some estimates); highly variable depending on methodology |

| Age of significant decline in neurogenesis |

Detectable decline starting mid-life (12–18 months); still measurable in aged animals | Steep decline reported from middle age; ongoing debate whether residual neurogenesis persists in elderly |

| Microglial density and activation state in aging | Well-characterized shift to 'primed' phenotype with pro-inflammatory gene expression and reduced phagocytic resolution | Less comprehensive; aged human microglia show pro-inflammatory signatures, distinct subsets identified via single-cell transcriptomics |

| Peripheral immune cell involvement in CNS with age | Increased infiltration of T cells (especially CD8⁺) into hippocampus and SVZ with aging; enhances IFN-γ tone | Limited but growing evidence; T-cell presence in human hippocampus in aging and neurodegeneration; mechanisms less defined |

| Evidence for exercise or enrichment effects | Exercise and enriched environments robustly increase neurogenesis and improve cognition in mice | Human studies show hippocampal volume increases and cognitive benefits; direct evidence for neurogenesis boost is indirect (MRI, blood biomarkers) |

| Inflammasome/NLRP3 activation with age | Strong evidence for NLRP3-driven IL-1β increase in aged rodent hippocampus, reducing neurogenesis | Human post-mortem and transcriptomic studies support NLRP3 upregulation in aging brain; functional causality harder to confirm |

| Translational caveats | High plasticity, short lifespan, and controlled environments amplify experimental effects | Human variability, long lifespan, and heterogeneous exposures complicate translation; methodological debates on detecting neurogenesis |

6. Integrating Mechanisms with Therapeutics: Toward Rewiring the Aging Brain

6.1. Mechanistic Gaps as Opportunities (~400 words)

6.2. Translational Roadmap

6.3. Ethical and Clinical Considerations (~400 Words)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AAV | adeno-associated virus |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CRISPR | clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CX3CL1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

| CX3CR1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 |

| DAM | disease-associated microglia |

| DCX | doublecortin |

| DG | dentate gyrus |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| IFN-γ | interferon-gamma |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-18 | interleukin-18 |

| iPSC | induced pluripotent stem cell |

| JAK/STAT1 | janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 |

| MCC950 | nlrp3 inflammasome inhibitor mcc950 |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NLRP3 | nod-like receptor protein 3 |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| PSA-NCAM | polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| SVZ | subventricular zone |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TSPO | translocator protein 18 kDa |

| Wnt | wingless-related integration site signaling pathway |

References

- Boldrini, M.; Fulmore, C.A.; Tartt, A.N.; Simeon, L.R.; Pavlova, I.; Poposka, V.; Rosoklija, G.B.; Stankov, A.; Arango, V.; Dwork, A.J.; et al. Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 589-599.e585. [CrossRef]

- Babcock, K.R.; Page, J.S.; Fallon, J.R.; Webb, A.E. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Aging and Alzheimer's Disease. Stem Cell Reports 2021, 16, 681-693. [CrossRef]

- Anacker, C.; Hen, R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive flexibility - linking memory and mood. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 335-346. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Direito, R.; Tanaka, M.; Jasmin Santos German, I.; Lamas, C.B.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; et al. Polyphenols, Alkaloids, and Terpenoids Against Neurodegeneration: Evaluating the Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocompounds Through a Comprehensive Review of the Current Evidence. Metabolites 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Culig, L.; Chu, X.; Bohr, V.A. Neurogenesis in aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 78, 101636. [CrossRef]

- Toda, T.; Parylak, S.L.; Linker, S.B.; Gage, F.H. The role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in brain health and disease. Mol Psychiatry 2019, 24, 67-87. [CrossRef]

- Valero, J.; Bernardino, L.; Cardoso, F.L.; Silva, A.P.; Fontes-Ribeiro, C.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Malva, J.O. Impact of Neuroinflammation on Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Relevance to Aging and Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 60, S161-s168. [CrossRef]

- Amanollahi, M.; Jameie, M.; Heidari, A.; Rezaei, N. The Dialogue Between Neuroinflammation and Adult Neurogenesis: Mechanisms Involved and Alterations in Neurological Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 923-959. [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, Á.; Molnár, K.; Nógrádi, B.; Hernádi, Z.; Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Wilhelm, I.; Krizbai, I.A. Neurovascular Inflammaging in Health and Disease. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, M.C.; Jurcau, A.; Cristian, A.; Hogea, V.O.; Diaconu, R.G.; Nunkoo, V.S. Inflammaging and Brain Aging. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Marschallinger, J.; Iram, T.; Zardeneta, M.; Lee, S.E.; Lehallier, B.; Haney, M.S.; Pluvinage, J.V.; Mathur, V.; Hahn, O.; Morgens, D.W.; et al. Lipid-droplet-accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23, 194-208. [CrossRef]

- Wendimu, M.Y.; Hooks, S.B. Microglia Phenotypes in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.M.; Schardien, K.; Wigdahl, B.; Nonnemacher, M.R. Roles of neuropathology-associated reactive astrocytes: a systematic review. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2023, 11, 42. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.E.; Liddelow, S.A.; Chakraborty, C.; Münch, A.E.; Heiman, M.; Barres, B.A. Normal aging induces A1-like astrocyte reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E1896-e1905. [CrossRef]

- Propson, N.E.; Roy, E.R.; Litvinchuk, A.; Köhl, J.; Zheng, H. Endothelial C3a receptor mediates vascular inflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability during aging. J Clin Invest 2021, 131. [CrossRef]

- Elahy, M.; Jackaman, C.; Mamo, J.C.; Lam, V.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Giles, C.; Nelson, D.; Takechi, R. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction developed during normal aging is associated with inflammation and loss of tight junctions but not with leukocyte recruitment. Immun Ageing 2015, 12, 2. [CrossRef]

- von Bernhardi, R.; Eugenín-von Bernhardi, L.; Eugenín, J. Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci 2015, 7, 124. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Tanaka, M.; Lamas, C.B.; Quesada, K.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Junior, E.B.; et al. Vascular Impairment, Muscle Atrophy, and Cognitive Decline: Critical Age-Related Conditions. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Y.C.; Mendes, N.M.; Pereira de Lima, E.; Chehadi, A.C.; Lamas, C.B.; Haber, J.F.S.; Dos Santos Bueno, M.; Araújo, A.C.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. Curcumin: A Golden Approach to Healthy Aging: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ramnauth, A.D.; Tippani, M.; Divecha, H.R.; Papariello, A.R.; Miller, R.A.; Nelson, E.D.; Thompson, J.R.; Pattie, E.A.; Kleinman, J.E.; Maynard, K.R.; et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of gene expression in the human dentate gyrus reveals age-associated changes in cellular maturation and neuroinflammation. Cell Rep 2025, 44, 115300. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Korobeynyk, V.I.; Zamboni, M.; Waern, F.; Cole, J.D.; Mundt, S.; Greter, M.; Frisén, J.; Llorens-Bobadilla, E.; Jessberger, S. Multimodal transcriptomics reveal neurogenic aging trajectories and age-related regional inflammation in the dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci 2025, 28, 415-430. [CrossRef]

- Mathews, K.J.; Allen, K.M.; Boerrigter, D.; Ball, H.; Shannon Weickert, C.; Double, K.L. Evidence for reduced neurogenesis in the aging human hippocampus despite stable stem cell markers. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 1195-1199. [CrossRef]

- Bedrosian, T.A.; Houtman, J.; Eguiguren, J.S.; Ghassemzadeh, S.; Rund, N.; Novaresi, N.M.; Hu, L.; Parylak, S.L.; Denli, A.M.; Randolph-Moore, L.; et al. Lamin B1 decline underlies age-related loss of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Embo j 2021, 40, e105819. [CrossRef]

- Ishijima, T.; Nakajima, K. Inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 are induced in endotoxin- stimulated microglia through different signaling cascades. Sci Prog 2021, 104, 368504211054985. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S. From Biomarkers to Behavior: Mapping the Neuroimmune Web of Pain, Mood, and Memory. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Araki, T.; Ikegaya, Y.; Koyama, R. The effects of microglia- and astrocyte-derived factors on neurogenesis in health and disease. Eur J Neurosci 2021, 54, 5880-5901. [CrossRef]

- Ekdahl, C.T. Microglial activation - tuning and pruning adult neurogenesis. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3, 41. [CrossRef]

- Früholz, I.; Meyer-Luehmann, M. The intricate interplay between microglia and adult neurogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18, 1456253. [CrossRef]

- Al-Onaizi, M.; Al-Khalifah, A.; Qasem, D.; ElAli, A. Role of Microglia in Modulating Adult Neurogenesis in Health and Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 359. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Molina, P.; Almolda, B.; Giménez-Llort, L.; González, B.; Castellano, B. Chronic IL-10 overproduction disrupts microglia-neuron dialogue similar to aging, resulting in impaired hippocampal neurogenesis and spatial memory. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 101, 231-245. [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, C.; Rinchon, A.; Olmos-Alonso, A.; Riecken, K.; Fehse, B.; Boche, D.; Perry, V.H.; Gomez-Nicola, D. Microglia regulate hippocampal neurogenesis during chronic neurodegeneration. Brain Behav Immun 2016, 55, 179-190. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rivas, E.; Ávila-Muñoz, E.; Schwarzacher, S.W.; Zepeda, A. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the context of lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation: A molecular, cellular and behavioral review. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 97, 286-302. [CrossRef]

- Chesnokova, V.; Pechnick, R.N.; Wawrowsky, K. Chronic peripheral inflammation, hippocampal neurogenesis, and behavior. Brain Behav Immun 2016, 58, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Rusznák, K.; Horváth Á, I.; Pohli-Tóth, K.; Futácsi, A.; Kemény, Á.; Kiss, G.; Helyes, Z.; Czéh, B. Experimental Arthritis Inhibits Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Mice. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zonis, S.; Pechnick, R.N.; Ljubimov, V.A.; Mahgerefteh, M.; Wawrowsky, K.; Michelsen, K.S.; Chesnokova, V. Chronic intestinal inflammation alters hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 65. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, C.; Su, D.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, W.; You, Z.; Zhou, T. Akebia saponin D protects hippocampal neurogenesis from microglia-mediated inflammation and ameliorates depressive-like behaviors and cognitive impairment in mice through the PI3K-Akt pathway. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 927419. [CrossRef]

- Ekdahl, C.T.; Claasen, J.H.; Bonde, S.; Kokaia, Z.; Lindvall, O. Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 13632-13637. [CrossRef]

- Golia, M.T.; Poggini, S.; Alboni, S.; Garofalo, S.; Ciano Albanese, N.; Viglione, A.; Ajmone-Cat, M.A.; St-Pierre, A.; Brunello, N.; Limatola, C.; et al. Interplay between inflammation and neural plasticity: Both immune activation and suppression impair LTP and BDNF expression. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 81, 484-494. [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Hidalgo, J.J.; Pang, Y. Role of neuroinflammation in the establishment of the neurogenic microenvironment in brain diseases. Current Tissue Microenvironment Reports 2021, 2, 17-28.

- Grabert, K.; Michoel, T.; Karavolos, M.H.; Clohisey, S.; Baillie, J.K.; Stevens, M.P.; Freeman, T.C.; Summers, K.M.; McColl, B.W. Microglial brain region-dependent diversity and selective regional sensitivities to aging. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, 504-516. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.L.; Yuan, Y.; Tian, L. Microglial regional heterogeneity and its role in the brain. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 351-367. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chang, Q.; Sun, T.; He, X.; Wen, L.; An, J.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Y. Metabolic reprogramming and polarization of microglia in Parkinson's disease: Role of inflammasome and iron. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 90, 102032. [CrossRef]

- Petralla, S.; De Chirico, F.; Miti, A.; Tartagni, O.; Massenzio, F.; Poeta, E.; Virgili, M.; Zuccheri, G.; Monti, B. Epigenetics and Communication Mechanisms in Microglia Activation with a View on Technological Approaches. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cai, L.; Gao, S.; Liu, T.; et al. Transcriptional and epigenetic decoding of the microglial aging process. Nat Aging 2023, 3, 1288-1311. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Yang, M.; Zeng, B.; Qiu, W.; Ma, Q.; Jing, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, B.; Yin, C.; et al. Transcriptome dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in macaques across the lifespan and aged humans. Cell Res 2022, 32, 729-743. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Jin, C.; Jin, Z.; Lu, J.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, L. Aged microglia promote peripheral T cell infiltration by reprogramming the microenvironment of neurogenic niches. Immun Ageing 2022, 19, 34. [CrossRef]

- Bisht, K.; Okojie, K.A.; Sharma, K.; Lentferink, D.H.; Sun, Y.Y.; Chen, H.R.; Uweru, J.O.; Amancherla, S.; Calcuttawala, Z.; Campos-Salazar, A.B.; et al. Capillary-associated microglia regulate vascular structure and function through PANX1-P2RY12 coupling in mice. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5289. [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, D.K.; Lauffenburger, D.A. Translating preclinical models to humans. Science 2020, 367, 742-743. [CrossRef]

- Gault, N.; Szele, F.G. Immunohistochemical evidence for adult human neurogenesis in health and disease. WIREs Mech Dis 2021, 13, e1526. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, R.R.; Kokovay, E. Rejuvenating subventricular zone neurogenesis in the aging brain. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2020, 50, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Xiong, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Hong, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Sun, X. Cellular rejuvenation: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 116. [CrossRef]

- Gillotin, S.; Sahni, V.; Lepko, T.; Hanspal, M.A.; Swartz, J.E.; Alexopoulou, Z.; Marshall, F.H. Targeting impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis in ageing by leveraging intrinsic mechanisms regulating Neural Stem Cell activity. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 71, 101447. [CrossRef]

- Niklison-Chirou, M.V.; Agostini, M.; Amelio, I.; Melino, G. Regulation of Adult Neurogenesis in Mammalian Brain. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.C.; Nigussie, F. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian dentate gyrus. Anat Histol Embryol 2020, 49, 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Apple, D.M.; Solano-Fonseca, R.; Kokovay, E. Neurogenesis in the aging brain. Biochem Pharmacol 2017, 141, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Nicaise, A.M.; Willis, C.M.; Crocker, S.J.; Pluchino, S. Stem Cells of the Aging Brain. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12, 247. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Whitney, N.; Wu, Y.; Tian, C.; Dou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J. HIV-1-infected and/or immune-activated macrophage-secreted TNF-alpha affects human fetal cortical neural progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Glia 2008, 56, 903-916. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, P.M.; Lemmens, E.; Dooley, D.; Hendrix, S. The role of "anti-inflammatory" cytokines in axon regeneration. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2013, 24, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Jin, N.; Guo, W. Neural stem cell heterogeneity in adult hippocampus. Cell Regen 2025, 14, 6. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Santoro, A.; Monti, D.; Crupi, R.; Di Paola, R.; Latteri, S.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Zappia, M.; Giordano, J.; Calabrese, E.J.; et al. Aging and Parkinson's Disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med 2018, 115, 80-91. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. From Microbial Switches to Metabolic Sensors: Rewiring the Gut-Brain Kynurenine Circuit. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Leme Boaro, B.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Patočka, J.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Tanaka, M.; Laurindo, L.F. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neuroinflammation Intervention with Medicinal Plants: A Critical and Narrative Review of the Current Literature. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Kang, E.; Liu, C.Y.; Ming, G.L.; Song, H. Development of neural stem cell in the adult brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008, 18, 108-115. [CrossRef]

- Obernier, K.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Neural stem cells: origin, heterogeneity and regulation in the adult mammalian brain. Development 2019, 146. [CrossRef]

- Kempermann, G.; Song, H.; Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the Adult Hippocampus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015, 7, a018812. [CrossRef]

- Cope, E.C.; Gould, E. Adult Neurogenesis, Glia, and the Extracellular Matrix. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 690-705. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Kageyama, R.; Imayoshi, I. The functional significance of newly born neurons integrated into olfactory bulb circuits. Front Neurosci 2014, 8, 121. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Bergami, M.; Ghanem, A.; Conzelmann, K.K.; Lepier, A.; Götz, M.; Berninger, B. Retrograde monosynaptic tracing reveals the temporal evolution of inputs onto new neurons in the adult dentate gyrus and olfactory bulb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E1152-1161. [CrossRef]

- Faigle, R.; Song, H. Signaling mechanisms regulating adult neural stem cells and neurogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1830, 2435-2448. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Shao, G.; Li, X. Epigenetic regulation in adult neural stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1331074. [CrossRef]

- Horgusluoglu, E.; Nudelman, K.; Nho, K.; Saykin, A.J. Adult neurogenesis and neurodegenerative diseases: A systems biology perspective. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2017, 174, 93-112. [CrossRef]

- Bátiz, L.F.; Castro, M.A.; Burgos, P.V.; Velásquez, Z.D.; Muñoz, R.I.; Lafourcade, C.A.; Troncoso-Escudero, P.; Wyneken, U. Exosomes as Novel Regulators of Adult Neurogenic Niches. Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9, 501. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, W. Neural Stem Cell Niche and Adult Neurogenesis. Neuroscientist 2021, 27, 235-245. [CrossRef]

- Quaresima, S.; Istiaq, A.; Jono, H.; Cacci, E.; Ohta, K.; Lupo, G. Assessing the Role of Ependymal and Vascular Cells as Sources of Extracellular Cues Regulating the Mouse Ventricular-Subventricular Zone Neurogenic Niche. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 845567. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.G.; Dickinson-Anson, H.; Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci 1996, 16, 2027-2033. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Clemenson, G.D.; Gage, F.H. New neurons in an aged brain. Behav Brain Res 2012, 227, 497-507. [CrossRef]

- Bin Imtiaz, M.K.; Jaeger, B.N.; Bottes, S.; Machado, R.A.C.; Vidmar, M.; Moore, D.L.; Jessberger, S. Declining lamin B1 expression mediates age-dependent decreases of hippocampal stem cell activity. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 967-977.e968. [CrossRef]

- Bast, L.; Calzolari, F.; Strasser, M.K.; Hasenauer, J.; Theis, F.J.; Ninkovic, J.; Marr, C. Increasing Neural Stem Cell Division Asymmetry and Quiescence Are Predicted to Contribute to the Age-Related Decline in Neurogenesis. Cell Rep 2018, 25, 3231-3240.e3238. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, J.R.; Daynac, M.; Chicheportiche, A.; Cebrian-Silla, A.; Sii Felice, K.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Boussin, F.D.; Mouthon, M.A. Vascular-derived TGF-β increases in the stem cell niche and perturbs neurogenesis during aging and following irradiation in the adult mouse brain. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5, 548-562. [CrossRef]

- Buckwalter, M.S.; Yamane, M.; Coleman, B.S.; Ormerod, B.K.; Chin, J.T.; Palmer, T.; Wyss-Coray, T. Chronically increased transforming growth factor-beta1 strongly inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. Am J Pathol 2006, 169, 154-164. [CrossRef]

- DeCarolis, N.A.; Kirby, E.D.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Palmer, T.D. The Role of the Microenvironmental Niche in Declining Stem-Cell Functions Associated with Biological Aging. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. A Decade of Dedication: Pioneering Perspectives on Neurological Diseases and Mental Illnesses. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Peinado, P.; Urbach, A. From Youthful Vigor to Aging Decline: Unravelling the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Determinants of Hippocampal Neural Stem Cell Aging. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, E.P.; Flor-García, M.; Terreros-Roncal, J.; Rábano, A.; Cafini, F.; Pallas-Bazarra, N.; Ávila, J.; Llorens-Martín, M. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med 2019, 25, 554-560. [CrossRef]

- Knoth, R.; Singec, I.; Ditter, M.; Pantazis, G.; Capetian, P.; Meyer, R.P.; Horvat, V.; Volk, B.; Kempermann, G. Murine features of neurogenesis in the human hippocampus across the lifespan from 0 to 100 years. PLoS One 2010, 5, e8809. [CrossRef]

- Flor-García, M.; Terreros-Roncal, J.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.P.; Ávila, J.; Rábano, A.; Llorens-Martín, M. Unraveling human adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nat Protoc 2020, 15, 668-693. [CrossRef]

- Terreros-Roncal, J.; Flor-García, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.P.; Rodríguez-Moreno, C.B.; Márquez-Valadez, B.; Gallardo-Caballero, M.; Rábano, A.; Llorens-Martín, M. Methods to study adult hippocampal neurogenesis in humans and across the phylogeny. Hippocampus 2023, 33, 271-306. [CrossRef]

- Seki, T. Understanding the Real State of Human Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis From Studies of Rodents and Non-human Primates. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 839. [CrossRef]

- Gulen, M.F.; Samson, N.; Keller, A.; Schwabenland, M.; Liu, C.; Glück, S.; Thacker, V.V.; Favre, L.; Mangeat, B.; Kroese, L.J.; et al. cGAS-STING drives ageing-related inflammation and neurodegeneration. Nature 2023, 620, 374-380. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Martins, S.; Ferreira, P.A.; Cardoso, A.M.S.; Guedes, J.R.; Peça, J.; Cardoso, A.L. The old guard: Age-related changes in microglia and their consequences. Mech Ageing Dev 2021, 197, 111512. [CrossRef]

- Koellhoffer, E.C.; McCullough, L.D.; Ritzel, R.M. Old Maids: Aging and Its Impact on Microglia Function. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- Ana, B. Aged-Related Changes in Microglia and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Exploring the Connection. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Škandík, M.; Friess, L.; Vázquez-Cabrera, G.; Keane, L.; Grabert, K.; Cruz De Los Santos, M.; Posada-Pérez, M.; Baleviciute, A.; Cheray, M.; Joseph, B. Age-associated microglial transcriptome leads to diminished immunogenicity and dysregulation of MCT4 and P2RY12/P2RY13 related functions. Cell Death Discov 2025, 11, 16. [CrossRef]

- Edler, M.K.; Mhatre-Winters, I.; Richardson, J.R. Microglia in Aging and Alzheimer's Disease: A Comparative Species Review. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- O'Neil, S.M.; Hans, E.E.; Jiang, S.; Wangler, L.M.; Godbout, J.P. Astrocyte immunosenescence and deficits in interleukin 10 signaling in the aged brain disrupt the regulation of microglia following innate immune activation. Glia 2022, 70, 913-934. [CrossRef]

- Tamatta, R.; Pai, V.; Jaiswal, C.; Singh, I.; Singh, A.K. Neuroinflammaging and the Immune Landscape: The Role of Autophagy and Senescence in Aging Brain. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 52. [CrossRef]

- Lutshumba, J.; Nikolajczyk, B.S.; Bachstetter, A.D. Dysregulation of Systemic Immunity in Aging and Dementia. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 652111. [CrossRef]

- Norden, D.M.; Godbout, J.P. Review: microglia of the aged brain: primed to be activated and resistant to regulation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2013, 39, 19-34. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, M.R.P.; Hohsfield, L.A.; Kramár, E.A.; Soreq, L.; Lee, R.J.; Pham, S.T.; Najafi, A.R.; Spangenberg, E.E.; Wood, M.A.; West, B.L.; et al. Replacement of microglia in the aged brain reverses cognitive, synaptic, and neuronal deficits in mice. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12832. [CrossRef]

- Niraula, A.; Sheridan, J.F.; Godbout, J.P. Microglia Priming with Aging and Stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 318-333. [CrossRef]

- Norden, D.M.; Muccigrosso, M.M.; Godbout, J.P. Microglial priming and enhanced reactivity to secondary insult in aging, and traumatic CNS injury, and neurodegenerative disease. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 29-41. [CrossRef]

- Neher, J.J.; Cunningham, C. Priming Microglia for Innate Immune Memory in the Brain. Trends Immunol 2019, 40, 358-374. [CrossRef]

- Hoeijmakers, L.; Heinen, Y.; van Dam, A.M.; Lucassen, P.J.; Korosi, A. Microglial Priming and Alzheimer's Disease: A Possible Role for (Early) Immune Challenges and Epigenetics? Front Hum Neurosci 2016, 10, 398. [CrossRef]

- O'Neil, S.M.; Witcher, K.G.; McKim, D.B.; Godbout, J.P. Forced turnover of aged microglia induces an intermediate phenotype but does not rebalance CNS environmental cues driving priming to immune challenge. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2018, 6, 129. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, D.; Risen, S.J.; Osburn, S.C.; Emge, T.; Sharma, S.; Gilberto, V.S.; Chatterjee, A.; Nagpal, P.; Moreno, J.A.; LaRocca, T.J. Nanoligomers targeting NF-κB and NLRP3 reduce neuroinflammation and improve cognitive function with aging and tauopathy. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 182. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Yin, S.; Wan, F.; Hu, J.; Kou, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, J.; et al. Targeting Microglial α-Synuclein/TLRs/NF-kappaB/NLRP3 Inflammasome Axis in Parkinson's Disease. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 719807. [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.Y.; Wang, R.C.; Pan, Y.L.; Yue, Z.G.; Zhou, R.; Xie, P.; Tang, Z.S. Mangiferin inhibited neuroinflammation through regulating microglial polarization and suppressing NF-κB, NLRP3 pathway. Chin J Nat Med 2021, 19, 112-119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chi, L. NTN-1 attenuates amyloid-β-mediated microglial neuroinflammation and memory impairment via the NF-κB pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2025, 17, 1516399. [CrossRef]

- Fornari Laurindo, L.; Aparecido Dias, J.; Cressoni Araújo, A.; Torres Pomini, K.; Machado Galhardi, C.; Rucco Penteado Detregiachi, C.; Santos de Argollo Haber, L.; Donizeti Roque, D.; Dib Bechara, M.; Vialogo Marques de Castro, M.; et al. Immunological dimensions of neuroinflammation and microglial activation: exploring innovative immunomodulatory approaches to mitigate neuroinflammatory progression. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1305933. [CrossRef]

- Borsini, A.; Zunszain, P.A.; Thuret, S.; Pariante, C.M. The role of inflammatory cytokines as key modulators of neurogenesis. Trends Neurosci 2015, 38, 145-157. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Ou, Z.; Xu, B.; Huang, J.; Long, D.; He, X.; Lin, X.; et al. JAK2/STAT3 signaling mediates IL-6-inhibited neurogenesis of neural stem cells through DNA demethylation/methylation. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 79, 159-173. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Ojala, J.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress activate inflammasomes: impact on the aging process and age-related diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012, 69, 2999-3013. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Redefining Roles: A Paradigm Shift in Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism for Innovative Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Juhász, L.; Spisák, K.; Szolnoki, B.Z.; Nászai, A.; Szabó, Á.; Rutai, A.; Tallósy, S.P.; Szabó, A.; Toldi, J.; Tanaka, M.; et al. The Power Struggle: Kynurenine Pathway Enzyme Knockouts and Brain Mitochondrial Respiration. J Neurochem 2025, 169, e70075. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Malovic, E.; Harishchandra, D.S.; Ghaisas, S.; Panicker, N.; Charli, A.; Palanisamy, B.N.; Rokad, D.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V.; et al. Mitochondrial impairment in microglia amplifies NLRP3 inflammasome proinflammatory signaling in cell culture and animal models of Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2017, 3, 30. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.E.; Vacondio, D.; van der Molen, L.; Jüttner, A.A.; Fung, W.K.; Karsten, M.; van Het Hof, B.; Fontijn, R.D.; Kooij, G.; Witte, M.E.; et al. Endothelial-Ercc1 DNA repair deficiency provokes blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 2025, 16, 1. [CrossRef]

- Dulken, B.W.; Buckley, M.T.; Navarro Negredo, P.; Saligrama, N.; Cayrol, R.; Leeman, D.S.; George, B.M.; Boutet, S.C.; Hebestreit, K.; Pluvinage, J.V.; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals T cell infiltration in old neurogenic niches. Nature 2019, 571, 205-210. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Valladares, M.; Moreno-Cugnon, L.; Silva, T.M.; Garcés, J.P.; Saenz-Antoñanzas, A.; Álvarez-Satta, M.; Matheu, A. CD8(+) T cells are increased in the subventricular zone with physiological and pathological aging. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13198. [CrossRef]

- Solano Fonseca, R.; Mahesula, S.; Apple, D.M.; Raghunathan, R.; Dugan, A.; Cardona, A.; O'Connor, J.; Kokovay, E. Neurogenic Niche Microglia Undergo Positional Remodeling and Progressive Activation Contributing to Age-Associated Reductions in Neurogenesis. Stem Cells Dev 2016, 25, 542-555. [CrossRef]

- Fonken, L.K.; Gaudet, A.D. Neuroimmunology of healthy brain aging. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2022, 77, 102649. [CrossRef]

- Chintamen, S.; Imessadouene, F.; Kernie, S.G. Immune Regulation of Adult Neurogenic Niches in Health and Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 571071. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Aparicio, I.; Paris, I.; Sierra-Torre, V.; Plaza-Zabala, A.; Rodríguez-Iglesias, N.; Márquez-Ropero, M.; Beccari, S.; Huguet, P.; Abiega, O.; Alberdi, E.; et al. Microglia Actively Remodel Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis through the Phagocytosis Secretome. J Neurosci 2020, 40, 1453-1482. [CrossRef]

- Sierra, A.; Encinas, J.M.; Deudero, J.J.; Chancey, J.H.; Enikolopov, G.; Overstreet-Wadiche, L.S.; Tsirka, S.E.; Maletic-Savatic, M. Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 483-495. [CrossRef]

- Kurematsu, C.; Sawada, M.; Ohmuraya, M.; Tanaka, M.; Kuboyama, K.; Ogino, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Oishi, H.; Inada, H.; Ishido, Y.; et al. Synaptic pruning of murine adult-born neurons by microglia depends on phosphatidylserine. J Exp Med 2022, 219. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yi, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J. The secretome of microglia induced by IL-4 of IFN-γ differently regulate proliferation, differentiation and survival of adult neural stem/progenitor cell by targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway. Cytotechnology 2022, 74, 407-420. [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.K.; Mori, E. Microglia support neural stem cell maintenance and growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 503, 1880-1884. [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, A.; Holtman, I.R.; Krueger, M.; Yogev, N.; Bruttger, J.; Khorooshi, R.; Benmamar-Badel, A.; de Boer-Bergsma, J.J.; Martin, N.A.; Karram, K.; et al. A novel microglial subset plays a key role in myelinogenesis in developing brain. Embo j 2017, 36, 3292-3308. [CrossRef]

- Mallard, C.; Tremblay, M.E.; Vexler, Z.S. Microglia and Neonatal Brain Injury. Neuroscience 2019, 405, 68-76. [CrossRef]

- Harley, S.B.R.; Willis, E.F.; Shaikh, S.N.; Blackmore, D.G.; Sah, P.; Ruitenberg, M.J.; Bartlett, P.F.; Vukovic, J. Selective Ablation of BDNF from Microglia Reveals Novel Roles in Self-Renewal and Hippocampal Neurogenesis. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 4172-4186. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gelyana, E.; Rajsombath, M.; Yang, T.; Li, S.; Selkoe, D. Environmental Enrichment Potently Prevents Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation by Human Amyloid β-Protein Oligomers. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 9041-9056. [CrossRef]

- Mee-Inta, O.; Zhao, Z.W.; Kuo, Y.M. Physical Exercise Inhibits Inflammation and Microglial Activation. Cells 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, J.; Lee, W.T.; Lee, J.E. M2 Phenotype Microglia-derived Cytokine Stimulates Proliferation and Neuronal Differentiation of Endogenous Stem Cells in Ischemic Brain. Exp Neurobiol 2017, 26, 33-41. [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, R.; McPherson, C.A.; Harry, G.J. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br J Pharmacol 2016, 173, 649-665. [CrossRef]

- Vay, S.U.; Flitsch, L.J.; Rabenstein, M.; Rogall, R.; Blaschke, S.; Kleinhaus, J.; Reinert, N.; Bach, A.; Fink, G.R.; Schroeter, M.; et al. The plasticity of primary microglia and their multifaceted effects on endogenous neural stem cells in vitro and in vivo. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 226. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.H.; Peketi, P.; Lenz, K.M. Microglia Regulate Cell Genesis in a Sex-dependent Manner in the Neonatal Hippocampus. Neuroscience 2021, 453, 237-255. [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, H.A.; Johnson, R.W. Dysregulated neuronal-microglial cross-talk during aging, stress and inflammation. Exp Neurol 2012, 233, 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, H.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, T.; He, H.; Yi, S.; Zhang, L.; Mo, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; et al. Priming of microglia with IFN-γ impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis and leads to depression-like behaviors and cognitive defects. Glia 2020, 68, 2674-2692. [CrossRef]

- Carrier, M.; Šimončičová, E.; St-Pierre, M.K.; McKee, C.; Tremblay, M. Psychological Stress as a Risk Factor for Accelerated Cellular Aging and Cognitive Decline: The Involvement of Microglia-Neuron Crosstalk. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 749737. [CrossRef]

- Afridi, R.; Lee, W.H.; Suk, K. Microglia Gone Awry: Linking Immunometabolism to Neurodegeneration. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 246. [CrossRef]

- Mecca, C.; Giambanco, I.; Donato, R.; Arcuri, C. Microglia and Aging: The Role of the TREM2-DAP12 and CX3CL1-CX3CR1 Axes. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, P.; Ziemka-Nalecz, M.; Sypecka, J.; Zalewska, T. The Impact of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 Axis in Neurological Disorders. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, J.; Colditz, M.J.; Blackmore, D.G.; Ruitenberg, M.J.; Bartlett, P.F. Microglia modulate hippocampal neural precursor activity in response to exercise and aging. J Neurosci 2012, 32, 6435-6443. [CrossRef]

- Bolós, M.; Perea, J.R.; Terreros-Roncal, J.; Pallas-Bazarra, N.; Jurado-Arjona, J.; Ávila, J.; Llorens-Martín, M. Absence of microglial CX3CR1 impairs the synaptic integration of adult-born hippocampal granule neurons. Brain Behav Immun 2018, 68, 76-89. [CrossRef]

- Morton, M.C.; Neckles, V.N.; Seluzicki, C.M.; Holmberg, J.C.; Feliciano, D.M. Neonatal Subventricular Zone Neural Stem Cells Release Extracellular Vesicles that Act as a Microglial Morphogen. Cell Rep 2018, 23, 78-89. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, Z.; Chen, G. CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis attenuates early brain injury via promoting the delivery of exosomal microRNA-124 from neuron to microglia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 209. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.D.; Song, X.Y.; He, G.W.; Peng, X.N.; Chen, Y.; Huang, P.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhu, S.M.; et al. Müller Glial-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Mitigate RGC Degeneration by Suppressing Microglial Activation via Cx3cl1-Cx3cr1 Signaling. Adv Healthc Mater 2025, 14, e2404306. [CrossRef]

- Fritze, J.; Muralidharan, C.; Stamp, E.; Ahlenius, H. Microglia undergo disease-associated transcriptional activation and CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1 expression regulates neurogenesis in the aged brain. Dev Neurobiol 2024, 84, 128-141. [CrossRef]

- Gemma, C.; Bachstetter, A.D.; Bickford, P.C. Neuron-Microglia Dialogue and Hippocampal Neurogenesis in the Aged Brain. Aging Dis 2010, 1, 232-244.

- Barko, K.; Shelton, M.; Xue, X.; Afriyie-Agyemang, Y.; Puig, S.; Freyberg, Z.; Tseng, G.C.; Logan, R.W.; Seney, M.L. Brain region- and sex-specific transcriptional profiles of microglia. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 945548. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.J.; Basri, B.; Sominsky, L.; Soch, A.; Ayala, M.T.; Reineck, P.; Gibson, B.C.; Barrientos, R.M. High-fat diet worsens the impact of aging on microglial function and morphology in a region-specific manner. Neurobiol Aging 2019, 74, 121-134. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Xavier, A.L.; Kress, B.T.; Goldman, S.A.; Lacerda de Menezes, J.R.; Nedergaard, M. A Distinct Population of Microglia Supports Adult Neurogenesis in the Subventricular Zone. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 11848-11861. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.K.; White, C.W., 3rd; Villeda, S.A. The systemic environment: at the interface of aging and adult neurogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 2018, 371, 105-113. [CrossRef]

- Lana, D.; Magni, G.; Landucci, E.; Wenk, G.L.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E.; Giovannini, M.G. Phenomic Microglia Diversity as a Druggable Target in the Hippocampus in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. Effects of Microglia on Neurogenesis. Glia 2015, 63, 1394-1405. [CrossRef]

- Chintamen, S.; Gaur, P.; Vo, N.; Bradshaw, E.M.; Menon, V.; Kernie, S.G. Distinct microglial transcriptomic signatures within the hippocampus. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0296280. [CrossRef]

- McKee, C.G.; Hoffos, M.; Vecchiarelli, H.A.; Tremblay, M. Microglia: A pharmacological target for the treatment of age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1125982. [CrossRef]

- McGroarty, J.; Salinas, S.; Evans, H.; Jimenez, B.; Tran, V.; Kadavakollu, S.; Vashist, A.; Atluri, V. Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation: A Key Driver in Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis. Biomolecules 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 2025, 22, 341-355. [CrossRef]

- Khilazheva, E.D.; Mosiagina, A.I.; Panina, Y.A.; Belozor, O.S.; Komleva, Y.K. Impact of NLRP3 Depletion on Aging-Related Metaflammation, Cognitive Function, and Social Behavior in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kracht, L.; Lerario, A.M.; Dubbelaar, M.L.; Brouwer, N.; Wesseling, E.M.; Boddeke, E.; Eggen, B.J.L.; Kooistra, S.M. Epigenetic regulation of innate immune memory in microglia. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 111. [CrossRef]

- Kamei, N.; Day, K.; Guo, W.; Haus, D.L.; Nguyen, H.X.; Scarfone, V.M.; Booher, K.; Jia, X.Y.; Cummings, B.J.; Anderson, A.J. Injured inflammatory environment overrides the TET2 shaped epigenetic landscape of pluripotent stem cell derived human neural stem cells. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 25186. [CrossRef]

- Itokawa, N.; Oshima, M.; Koide, S.; Takayama, N.; Kuribayashi, W.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Aoyama, K.; Yamazaki, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Furukawa, Y.; et al. Epigenetic traits inscribed in chromatin accessibility in aged hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2691. [CrossRef]

- Zocher, S.; Toda, T. Epigenetic aging in adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus 2023, 33, 347-359. [CrossRef]

- Das, N.D.; Chai, Y.G. Neuroinflammation on the Epigenetics. Neural Stem Cells: New Perspectives 2013, 381.

- Kodi, T.; Sankhe, R.; Gopinathan, A.; Nandakumar, K.; Kishore, A. New Insights on NLRP3 Inflammasome: Mechanisms of Activation, Inhibition, and Epigenetic Regulation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2024, 19, 7. [CrossRef]

- Holleman, J.; Daniilidou, M.; Kåreholt, I.; Aspö, M.; Hagman, G.; Udeh-Momoh, C.T.; Spulber, G.; Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; Matton, A.; et al. Diurnal cortisol, neuroinflammation, and neuroimaging visual rating scales in memory clinic patients. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 118, 499-509. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Quax, R.; Crielaard, L.; Badiali, L.; Sloot, P.M.A. Inferring temporal dynamics from cross-sectional data using Langevin dynamics. R Soc Open Sci 2021, 8, 211374. [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, M.; Desouky, A.; Sirry, W. Imaging Transcriptomics in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Neuroimaging 2021, 31, 244-250. [CrossRef]

- Argiris, G.; Stern, Y.; Habeck, C. Quantifying Age-Related Changes in Brain and Behavior: A Longitudinal versus Cross-Sectional Approach. eNeuro 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sochocka, M.; Diniz, B.S.; Leszek, J. Inflammatory Response in the CNS: Friend or Foe? Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54, 8071-8089. [CrossRef]

- Voloboueva, L.A.; Sun, X.; Xu, L.; Ouyang, Y.B.; Giffard, R.G. Distinct Effects of miR-210 Reduction on Neurogenesis: Increased Neuronal Survival of Inflammation But Reduced Proliferation Associated with Mitochondrial Enhancement. J Neurosci 2017, 37, 3072-3084. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Choi, J.Y.; Ryu, Y.H. The development status of PET radiotracers for evaluating neuroinflammation. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2024, 58, 160-176. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Chaney, A.M.; Carlson, M.L.; Jackson, I.M.; Rao, A.; James, M.L. Neuroinflammation PET Imaging: Current Opinion and Future Directions. J Nucl Med 2020, 61, 1107-1112. [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswami, V.; Dahl, K.; Bernard-Gauthier, V.; Josephson, L.; Cumming, P.; Vasdev, N. Emerging PET Radiotracers and Targets for Imaging of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Outlook Beyond TSPO. Mol Imaging 2018, 17, 1536012118792317. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Haider, A.; Chen, J.; Xiao, Z.; Gobbi, L.; Honer, M.; Grether, U.; Arnold, S.E.; Josephson, L.; Liang, S.H. The Repertoire of Small-Molecule PET Probes for Neuroinflammation Imaging: Challenges and Opportunities beyond TSPO. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 17656-17689. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, H.S.; Wang, X.; Dumont, A.S.; Liu, Q. Cellular senescence, DNA damage, and neuroinflammation in the aging brain. Trends Neurosci 2024, 47, 461-474. [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Chan, A.K.Y.; Wu, J.; Lee, T.M.C. Relationships between Inflammation and Age-Related Neurocognitive Changes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, O.; Gutierrez-Fernandez, F.; Lopez-Virgen, V.; Collas-Aguilar, J.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M. Immunological regulation of neurogenic niches in the adult brain. Neuroscience 2012, 226, 270-281. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Basu, A. Inflammation: a new candidate in modulating adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res 2008, 86, 1199-1208. [CrossRef]

- Galea, I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic infection and inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 2489-2501. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shen, Q.; Chang, H.; Li, J.; Xing, D. Promoted CD4(+) T cell-derived IFN-γ/IL-10 by photobiomodulation therapy modulates neurogenesis to ameliorate cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 and 3xTg-AD mice. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 253. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, A.; Goodell, M.A.; Rando, T.A. Ageing and rejuvenation of tissue stem cells and their niches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24, 45-62. [CrossRef]

- Parkitny, L.; Maletic-Savatic, M. Glial PAMPering and DAMPening of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Allen, W.E.; Blosser, T.R.; Sullivan, Z.A.; Dulac, C.; Zhuang, X. Molecular and spatial signatures of mouse brain aging at single-cell resolution. Cell 2023, 186, 194-208.e118. [CrossRef]

- Velikic, G.; Maric, D.M.; Maric, D.L.; Supic, G.; Puletic, M.; Dulic, O.; Vojvodic, D. Harnessing the Stem Cell Niche in Regenerative Medicine: Innovative Avenue to Combat Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.; Arellano, J.I.; Rakic, P. An assessment of the existence of adult neurogenesis in humans and value of its rodent models for neuropsychiatric diseases. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 377-382. [CrossRef]

- Geirsdottir, L.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Weiner, A.; Bohlen, S.C.; Neuber, J.; Balic, A.; Giladi, A.; Sheban, F.; Dutertre, C.A.; et al. Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis Reveals Divergence of the Primate Microglia Program. Cell 2019, 179, 1609-1622.e1616. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.A.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. The Adult Ventricular-Subventricular Zone (V-SVZ) and Olfactory Bulb (OB) Neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Denoth-Lippuner, A.; Jessberger, S. Formation and integration of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 223-236. [CrossRef]

- Tosoni, G.; Ayyildiz, D.; Bryois, J.; Macnair, W.; Fitzsimons, C.P.; Lucassen, P.J.; Salta, E. Mapping human adult hippocampal neurogenesis with single-cell transcriptomics: Reconciling controversy or fueling the debate? Neuron 2023, 111, 1714-1731.e1713. [CrossRef]

- Nutma, E.; Fancy, N.; Weinert, M.; Tsartsalis, S.; Marzin, M.C.; Muirhead, R.C.J.; Falk, I.; Breur, M.; de Bruin, J.; Hollaus, D.; et al. Translocator protein is a marker of activated microglia in rodent models but not human neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5247. [CrossRef]

- Pediaditakis, I.; Kodella, K.R.; Manatakis, D.V.; Le, C.Y.; Barthakur, S.; Sorets, A.; Gravanis, A.; Ewart, L.; Rubin, L.L.; Manolakos, E.S.; et al. A microengineered Brain-Chip to model neuroinflammation in humans. iScience 2022, 25, 104813. [CrossRef]

- Tian, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Muffat, J.; Li, Y. Expanding the neuroimmune research toolkit with in vivo brain organoid technologies. Dis Model Mech 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Balestri, W.; Sharma, R.; da Silva, V.A.; Bobotis, B.C.; Curle, A.J.; Kothakota, V.; Kalantarnia, F.; Hangad, M.V.; Hoorfar, M.; Jones, J.L.; et al. Modeling the neuroimmune system in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 32. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Parkinson's Disease: Bridging Gaps, Building Biomarkers, and Reimagining Clinical Translation. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S. Dualistic Dynamics in Neuropsychiatry: From Monoaminergic Modulators to Multiscale Biomarker Maps. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, S.; Crowley, G.; Hong, S. Understanding microglial diversity and implications for neuronal function in health and disease. Dev Neurobiol 2021, 81, 507-523. [CrossRef]

- Takkinen, J.S.; López-Picón, F.R.; Al Majidi, R.; Eskola, O.; Krzyczmonik, A.; Keller, T.; Löyttyniemi, E.; Solin, O.; Rinne, J.O.; Haaparanta-Solin, M. Brain energy metabolism and neuroinflammation in ageing APP/PS1-21 mice using longitudinal (18)F-FDG and (18)F-DPA-714 PET imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017, 37, 2870-2882. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Bottes, S.; Fisch, R.; Zehnder, C.; Cole, J.D.; Pilz, G.A.; Helmchen, F.; Simons, B.D.; Jessberger, S. Chronic in vivo imaging defines age-dependent alterations of neurogenesis in the mouse hippocampus. Nat Aging 2023, 3, 380-390. [CrossRef]

- Mathys, H.; Adaikkan, C.; Gao, F.; Young, J.Z.; Manet, E.; Hemberg, M.; De Jager, P.L.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Regev, A.; Tsai, L.H. Temporal Tracking of Microglia Activation in Neurodegeneration at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 366-380. [CrossRef]

- Kreisl, W.C.; Kim, M.J.; Coughlin, J.M.; Henter, I.D.; Owen, D.R.; Innis, R.B. PET imaging of neuroinflammation in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 940-950. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. From Serendipity to Precision: Integrating AI, Multi-Omics, and Human-Specific Models for Personalized Neuropsychiatric Care. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kamei, R.; Urata, S.; Maruoka, H.; Okabe, S. In vivo Chronic Two-Photon Imaging of Microglia in the Mouse Hippocampus. J Vis Exp 2022. [CrossRef]

- Padmashri, R.; Tyner, K.; Dunaevsky, A. Implantation of a Cranial Window for Repeated In Vivo Imaging in Awake Mice. J Vis Exp 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Tang, F.; Guo, Y.; Xu, R.; Lei, P. Neural circuit changes in neurological disorders: Evidence from in vivo two-photon imaging. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 87, 101933. [CrossRef]

- Ulivi, A.F.; Castello-Waldow, T.P.; Weston, G.; Yan, L.; Yasuda, R.; Chen, A.; Attardo, A. Longitudinal Two-Photon Imaging of Dorsal Hippocampal CA1 in Live Mice. J Vis Exp 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Ji, B.; Guan, Y.; Cao, L.; Ni, R. Recent Technical Advances in Accelerating the Clinical Translation of Small Animal Brain Imaging: Hybrid Imaging, Deep Learning, and Transcriptomics. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 771982. [CrossRef]

- Guglielmetti, C.; Levi, J.; Huynh, T.L.; Tiret, B.; Blecha, J.; Tang, R.; VanBrocklin, H.; Chaumeil, M.M. Longitudinal Imaging of T Cells and Inflammatory Demyelination in a Preclinical Model of Multiple Sclerosis Using (18)F-FAraG PET and MRI. J Nucl Med 2022, 63, 140-146. [CrossRef]

- Best, L.; Ghadery, C.; Pavese, N.; Tai, Y.F.; Strafella, A.P. New and Old TSPO PET Radioligands for Imaging Brain Microglial Activation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019, 19, 24. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Takata, K.; Eguchi, A.; Yamato, M.; Kume, S.; Nakano, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Kataoka, Y. Noninvasive Evaluation of Cellular Proliferative Activity in Brain Neurogenic Regions in Rats under Depression and Treatment by Enhanced [18F]FLT-PET Imaging. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 8123-8131. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.G. Uses of Human MR and PET Imaging in Research of Neurodegenerative Brain Diseases. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 661-672. [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, J.G.; Schmid, A.M.; Schwenck, J.; Katiyar, P.; Herfert, K.; Pichler, B.J.; Disselhorst, J.A. PET/MRI Hybrid Systems. Semin Nucl Med 2018, 48, 332-347. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; He, Z.; Han, S.; Battaglia, S. Editorial: Noninvasive brain stimulation: a promising approach to study and improve emotion regulation. Front Behav Neurosci 2025, 19, 1633936. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S.; Liloia, D. Navigating Neurodegeneration: Integrating Biomarkers, Neuroinflammation, and Imaging in Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Motor Neuron Disorders. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Valotto Neto, L.J.; Reverete de Araujo, M.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Mendes Machado, N.; Joshi, R.K.; Dos Santos Buglio, D.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Direito, R.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chauveau, F.; Winkeler, A.; Chalon, S.; Boutin, H.; Becker, G. PET imaging of neuroinflammation: any credible alternatives to TSPO yet? Mol Psychiatry 2025, 30, 213-228. [CrossRef]

- Beaino, W.; Janssen, B.; Kooij, G.; van der Pol, S.M.A.; van Het Hof, B.; van Horssen, J.; Windhorst, A.D.; de Vries, H.E. Purinergic receptors P2Y12R and P2X7R: potential targets for PET imaging of microglia phenotypes in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 259. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Ji, B.; Kong, Y.; Qin, L.; Ren, W.; Guan, Y.; Ni, R. PET Imaging of Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 739130. [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.A.; Nutt, D.J.; Tyacke, R.J. Imidazoline-I2 PET Tracers in Neuroimaging. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Zaharchuk, G. Next generation research applications for hybrid PET/MR and PET/CT imaging using deep learning. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019, 46, 2700-2707. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, M.; Cavaliere, C.; Fiorenza, D.; Duggento, A.; Passamonti, L.; Toschi, N. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Multi-modal Imaging Studies and Future Opportunities for Hybrid PET/MRI. Neuroscience 2019, 403, 125-135. [CrossRef]

- Beaino, W.; Janssen, B.; Vugts, D.J.; de Vries, H.E.; Windhorst, A.D. Towards PET imaging of the dynamic phenotypes of microglia. Clin Exp Immunol 2021, 206, 282-300. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, F.Y.; Yen, Y. Imaging biomarkers for clinical applications in neuro-oncology: current status and future perspectives. Biomark Res 2023, 11, 35. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Special Issue "Translating Molecular Psychiatry: From Biomarkers to Personalized Therapies". Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, V.; Brummer, T.; Muthuraman, M.; Steffen, F.; Heldt, M.; Protopapa, M.; Schraad, M.; Gonzalez-Escamilla, G.; Groppa, S.; Bittner, S.; et al. Biomarker combinations from different modalities predict early disability accumulation in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1532660. [CrossRef]

- Vassal, M.; Martins, F.; Monteiro, B.; Tambaro, S.; Martinez-Murillo, R.; Rebelo, S. Emerging Pro-neurogenic Therapeutic Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review of Pre-clinical and Clinical Research. Mol Neurobiol 2025, 62, 46-76. [CrossRef]

- Praça, C.; Rai, A.; Santos, T.; Cristovão, A.C.; Pinho, S.L.; Cecchelli, R.; Dehouck, M.P.; Bernardino, L.; Ferreira, L.S. A nanoformulation for the preferential accumulation in adult neurogenic niches. J Control Release 2018, 284, 57-72. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Tuka, B.; Vécsei, L. Navigating the Neurobiology of Migraine: From Pathways to Potential Therapies. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, G. Inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis induced by postoperative CD8 + T-cell infiltration is associated with cognitive decline later following surgery in adult mice. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 227. [CrossRef]

- Brocke, S.; Piercy, C.; Steinman, L.; Weissman, I.L.; Veromaa, T. Antibodies to CD44 and integrin alpha4, but not L-selectin, prevent central nervous system inflammation and experimental encephalomyelitis by blocking secondary leukocyte recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 6896-6901. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tang, X.; Deng, P.; Hui, H.; Chen, B.; An, J.; Zhang, G.; Shi, K.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; et al. Interleukin-4 from curcumin-activated OECs emerges as a central modulator for increasing M2 polarization of microglia/macrophage in OEC anti-inflammatory activity for functional repair of spinal cord injury. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 162. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, B.; Tirolo, C.; L'Episcopo, F.; Caniglia, S.; Testa, N.; Smith, J.A.; Pluchino, S.; Serapide, M.F. Parkinson's disease, aging and adult neurogenesis: Wnt/β-catenin signalling as the key to unlock the mystery of endogenous brain repair. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13101. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Wu, Z.; Xue, L.; Fan, W.; Huang, R.; Xu, Z.; et al. Immunomodulatory Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles Enable Neurogenesis by Targeting Transforming Growth Factor-β Receptor 2. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 2812-2830. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Heinen, S.; Krantic, S.; McLaurin, J.; Branch, D.R.; Hynynen, K.; Aubert, I. Clinically approved IVIg delivered to the hippocampus with focused ultrasound promotes neurogenesis in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 32691-32700. [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, V.; Grilli, M. Neural stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: mini players with key roles in neurogenesis, immunomodulation, neuroprotection and aging. Front Mol Biosci 2023, 10, 1187263. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, G. In Vivo Reprogramming for CNS Repair: Regenerating Neurons from Endogenous Glial Cells. Neuron 2016, 91, 728-738. [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, Y.; Shibata, K.; Yoshida, K.; Shigetomi, E.; Gachet, C.; Ikenaka, K.; Tanaka, K.F.; Koizumi, S. Transformation of Astrocytes to a Neuroprotective Phenotype by Microglia via P2Y(1) Receptor Downregulation. Cell Rep 2017, 19, 1151-1164. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, G. In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer's disease model. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 188-202. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ramirez-Matias, J.; Hauptschein, M.; Sun, E.D.; Lunger, J.C.; Buckley, M.T.; Brunet, A. Restoration of neuronal progenitors by partial reprogramming in the aged neurogenic niche. Nat Aging 2024, 4, 546-567. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Rong, P.; Zhang, L.; He, H.; Zhou, T.; Fan, Y.; Mo, L.; Zhao, Q.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; et al. IL4-driven microglia modulate stress resilience through BDNF-dependent neurogenesis. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Seong, K.J.; Bae, S.W.; Kook, M.S.; Chun, C.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, W.S.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, W.J. Water-Soluble Arginyl-Diosgenin Analog Attenuates Hippocampal Neurogenesis Impairment Through Blocking Microglial Activation Underlying NF-κB and JNK MAPK Signaling in Adult Mice Challenged by LPS. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 6218-6238. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Kong, C.; Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Bai, W.; He, X. MiR-124 Enriched Exosomes Promoted the M2 Polarization of Microglia and Enhanced Hippocampus Neurogenesis After Traumatic Brain Injury by Inhibiting TLR4 Pathway. Neurochem Res 2019, 44, 811-828. [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.; Lai, X.; Xu, W.; Qin, Q.; Liang, X.; Xie, M.; Chen, L. The Mechanisms and Application Prospects of Astrocyte Reprogramming into Neurons in Central Nervous System Diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yin, J.C.; Yeh, H.; Ma, N.X.; Lee, G.; Chen, X.A.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, L.; Jin, P.; et al. Small Molecules Efficiently Reprogram Human Astroglial Cells into Functional Neurons. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 735-747. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, H.; Du, X.; Wang, L.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; et al. In vivo chemical reprogramming of astrocytes into neurons. Cell Discov 2021, 7, 12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lai, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, W.; Qin, Q.; Qin, R.; Huang, X.; Xie, M.; et al. A promise for neuronal repair: reprogramming astrocytes into neurons in vivo. Biosci Rep 2024, 44. [CrossRef]

- Revuelta, M.; Urrutia, J.; Villarroel, A.; Casis, O. Microglia-Mediated Inflammation and Neural Stem Cell Differentiation in Alzheimer's Disease: Possible Therapeutic Role of K(V)1.3 Channel Blockade. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 16, 868842. [CrossRef]

- Greșiță, A.; Hermann, D.M.; Boboc, I.K.S.; Doeppner, T.R.; Petcu, E.; Semida, G.F.; Popa-Wagner, A. Glial Cell Reprogramming in Ischemic Stroke: A Review of Recent Advancements and Translational Challenges. Transl Stroke Res 2025, 16, 1811-1835. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for advancements in cancer immunotherapy: from uncovering regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Exp Hematol Oncol 2024, 13, 102. [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; Xu, X.M.; Zhang, C.L. Regeneration Through in vivo Cell Fate Reprogramming for Neural Repair. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 107. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, N.; Wang, Y.; Moriarty, N.; Ahmed, N.Y.; Dehorter, N.; Lisowski, L.; Harvey, A.R.; Parish, C.L.; Williams, R.J.; Nisbet, D.R. Neuronal Replenishment via Hydrogel-Rationed Delivery of Reprogramming Factors. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 3597-3613. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tu, D.; Wilson, B.; Song, S.; Feng, J.; Hong, J.S.; et al. A novel role of NLRP3-generated IL-1β in the acute-chronic transition of peripheral lipopolysaccharide-elicited neuroinflammation: implications for sepsis-associated neurodegeneration. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 64. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.; Billinton, A.; Bock, M.G.; Doedens, J.R.; Gabel, C.A.; Holloway, M.K.; Porter, R.A.; Reader, V.; Scanlon, J.; Schooley, K.; et al. Discovery of Clinical Candidate NT-0796, a Brain-Penetrant and Highly Potent NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor for Neuroinflammatory Disorders. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 14897-14911. [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.; Li, W.; Abdul, Y.; Jackson, L.; Dong, G.; Jamil, S.; Filosa, J.; Fagan, S.C.; Ergul, A. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition with MCC950 improves diabetes-mediated cognitive impairment and vasoneuronal remodeling after ischemia. Pharmacol Res 2019, 142, 237-250. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.; Albornoz, E.A.; Christie, D.C.; Langley, M.R.; Kumar, V.; Mantovani, S.; Robertson, A.A.B.; Butler, M.S.; Rowe, D.B.; O'Neill, L.A.; et al. Inflammasome inhibition prevents α-synuclein pathology and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in mice. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, C.; Rubio Araiz, A.; Bryson, K.J.; Finucane, O.; Larkin, C.; Mills, E.L.; Robertson, A.A.B.; Cooper, M.A.; O'Neill, L.A.J.; Lynch, M.A. Inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome with MCC950 promotes non-phlogistic clearance of amyloid-β and cognitive function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Behav Immun 2017, 61, 306-316. [CrossRef]

- Mackay, A.; Velcicky, J.; Gommermann, N.; Mattes, H.; Janser, P.; Wright, M.; Dubois, C.; Brenneisen, S.; Ilic, S.; Vangrevelinghe, E.; et al. Discovery of NP3-253, a Potent Brain Penetrant Inhibitor of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. J Med Chem 2024, 67, 20780-20798. [CrossRef]

- Kuwar, R.; Rolfe, A.; Di, L.; Blevins, H.; Xu, Y.; Sun, X.; Bloom, G.S.; Zhang, S.; Sun, D. A Novel Inhibitor Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome Reduces Neuropathology and Improves Cognitive Function in Alzheimer's Disease Transgenic Mice. J Alzheimers Dis 2021, 82, 1769-1783. [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; da Silva, R.M.S.; Gallerani Caglioni, L.; Nunes Junqueira de Moraes, V.B.F.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Beluce, M.E.; et al. AdipoRon's Impact on Alzheimer's Disease-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, F.; Guo, Y.; Hu, B.; Xu, G.; Peng, S.; Wu, L.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome in cognitive impairment and pharmacological properties of its inhibitors. Transl Neurodegener 2023, 12, 49. [CrossRef]

- McManus, R.M.; Latz, E. NLRP3 inflammasome signalling in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology 2024, 252, 109941. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, M.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Yao, H.; Chen, M.; Sun, Y.; Ding, J.; et al. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activates neurotoxic astrocytes in depression-like mice. Cell Rep 2022, 41, 111532. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Tian, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, B. Aerobic Exercise Restores Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Cognitive Function by Decreasing Microglia Inflammasome Formation Through Irisin/NLRP3 Pathway. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70061. [CrossRef]

- Vande Walle, L.; Lamkanfi, M. Drugging the NLRP3 inflammasome: from signalling mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2024, 23, 43-66. [CrossRef]

- Mammoliti, O.; Carbajo, R.; Perez-Benito, L.; Yu, X.; Prieri, M.L.C.; Bontempi, L.; Embrechts, S.; Paesmans, I.; Bassi, M.; Bhattacharya, A.; et al. Discovery of Potent and Brain-Penetrant Bicyclic NLRP3 Inhibitors with Peripheral and Central In Vivo Activity. J Med Chem 2025, 68, 4848-4887. [CrossRef]

- Barczuk, J.; Siwecka, N.; Lusa, W.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Targeting NLRP3-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Lv, R.; Shi, X.; Yang, G.; Jin, J. CRISPR/dCas9 Tools: Epigenetic Mechanism and Application in Gene Transcriptional Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.S.; Wu, H.; Ji, X.; Stelzer, Y.; Wu, X.; Czauderna, S.; Shu, J.; Dadon, D.; Young, R.A.; Jaenisch, R. Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 2016, 167, 233-247.e217. [CrossRef]

- O'Geen, H.; Ren, C.; Nicolet, C.M.; Perez, A.A.; Halmai, J.; Le, V.M.; Mackay, J.P.; Farnham, P.J.; Segal, D.J. dCas9-based epigenome editing suggests acquisition of histone methylation is not sufficient for target gene repression. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, 9901-9916. [CrossRef]

- Vojta, A.; Dobrinić, P.; Tadić, V.; Bočkor, L.; Korać, P.; Julg, B.; Klasić, M.; Zoldoš, V. Repurposing the CRISPR-Cas9 system for targeted DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 5615-5628. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Brommer, B.; Tian, X.; Krishnan, A.; Meer, M.; Wang, C.; Vera, D.L.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, D.; Bonkowski, M.S.; et al. Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision. Nature 2020, 588, 124-129. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, J.K.; Chen, J.; Pommier, G.C.; Cogan, J.Z.; Replogle, J.M.; Adriaens, C.; Ramadoss, G.N.; Shi, Q.; Hung, K.L.; Samelson, A.J.; et al. Genome-wide programmable transcriptional memory by CRISPR-based epigenome editing. Cell 2021, 184, 2503-2519.e2517. [CrossRef]

- Pattali, R.K.; Ornelas, I.J.; Nguyen, C.D.; Xu, D.; Divekar, N.S.; Nuñez, J.K. CRISPRoff epigenetic editing for programmable gene silencing in human cells without DNA breaks. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yim, Y.Y.; Teague, C.D.; Nestler, E.J. In vivo locus-specific editing of the neuroepigenome. Nat Rev Neurosci 2020, 21, 471-484. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wang, X.; Feng, C.; Zhang, K.; Chen, D.; Yang, S. Vectors in CRISPR Gene Editing for Neurological Disorders: Challenges and Opportunities. Adv Biol (Weinh) 2025, 9, e2400374. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Rho, W.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Chang, H.; Jun, B.H. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Therapy: Non-Viral Delivery and Stimuli-Responsive Nanoformulations. Molecules 2025, 30. [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, D.; Yang, S. Application of novel CRISPR tools in brain therapy. Life Sci 2024, 352, 122855. [CrossRef]

- NodThera’s NLRP3 Inhibitor NT-0796 Reverses Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease Phase Ib/IIa Trial. Available online: https://www.nodthera.com/news/nodtheras-nlrp3-inhibitor-nt-0796-reverses-neuroinflammation-in-parkinsons-disease-phase-ib-iia-trial/#:~:text=NodThera%27s%20NLRP3%20Inhibitor%20NT,biomarkers%20in%20Parkinson%27s%20disease%20patients (accessed on 11.18).

- Moreno-Jiménez, E.P.; Terreros-Roncal, J.; Flor-García, M.; Rábano, A.; Llorens-Martín, M. Evidences for Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Humans. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 2541-2553. [CrossRef]

- Arellano, J.I.; Rakic, P. Modelling adult neurogenesis in the aging rodent hippocampus: a midlife crisis. Front Neurosci 2024, 18, 1416460. [CrossRef]

- Darsalia, V.; Heldmann, U.; Lindvall, O.; Kokaia, Z. Stroke-induced neurogenesis in aged brain. Stroke 2005, 36, 1790-1795. [CrossRef]

- Simard, S.; Matosin, N.; Mechawar, N. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in the Human Brain: Updates, Challenges, and Perspectives. Neuroscientist 2025, 31, 141-158. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.G.; Toda, T.; Gage, F.H. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: A Coming-of-Age Story. J Neurosci 2018, 38, 10401-10410. [CrossRef]

- Kempermann, G.; Gage, F.H.; Aigner, L.; Song, H.; Curtis, M.A.; Thuret, S.; Kuhn, H.G.; Jessberger, S.; Frankland, P.W.; Cameron, H.A.; et al. Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Holtman, I.R.; Raj, D.D.; Miller, J.A.; Schaafsma, W.; Yin, Z.; Brouwer, N.; Wes, P.D.; Möller, T.; Orre, M.; Kamphuis, W.; et al. Induction of a common microglia gene expression signature by aging and neurodegenerative conditions: a co-expression meta-analysis. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2015, 3, 31. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, T.R.; Dufort, C.; Dissing-Olesen, L.; Giera, S.; Young, A.; Wysoker, A.; Walker, A.J.; Gergits, F.; Segel, M.; Nemesh, J.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Microglia throughout the Mouse Lifespan and in the Injured Brain Reveals Complex Cell-State Changes. Immunity 2019, 50, 253-271.e256. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, A.; Bell-Temin, H.; Jalloh, A.; Stevens, S.M., Jr.; Bickford, P.C. Proteomic anaysis of aged microglia: shifts in transcription, bioenergetics, and nutrient response. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 96. [CrossRef]

- Galatro, T.F.; Holtman, I.R.; Lerario, A.M.; Vainchtein, I.D.; Brouwer, N.; Sola, P.R.; Veras, M.M.; Pereira, T.F.; Leite, R.E.P.; Möller, T.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of purified human cortical microglia reveals age-associated changes. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 1162-1171. [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, J.; You, D.; Cheng, J.; Cao, X. Exploring the feasibility of using mice as a substitute model for investigating microglia in aging and Alzheimer's disease though single cell analysis. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0311374. [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Yan, Y.; Cao, Q.; Zou, L.; Li, S.; Yang, Q.; Deng, Q.; Wu, B.; Song, B. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying astrocyte-microglia crosstalk in hippocampal neuroinflammation induced by acute diquat exposure. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2024, 31, 15746-15758. [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, P.; He, Y.; Peng, B.; Liu, W.; Han, S.; Yin, J.; He, X. Inhibition of the NLRP3-inflammasome prevents cognitive deficits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice via the alteration of astrocyte phenotype. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 377. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.L.; Biggs, K.E.; Rankin, B.E.; Havrda, M.C. NLRP3 inflammasome in neurodegenerative disease. Transl Res 2023, 252, 21-33. [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, S.; Dale, G.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; Bullock, M.R.; Dietrich, W.D.; Keane, R.W. Inflammasome proteins in cerebrospinal fluid of brain-injured patients as biomarkers of functional outcome: clinical article. J Neurosurg 2012, 117, 1119-1125. [CrossRef]

- Chou, V.; Pearse, R.V., 2nd; Aylward, A.J.; Ashour, N.; Taga, M.; Terzioglu, G.; Fujita, M.; Fancher, S.B.; Sigalov, A.; Benoit, C.R.; et al. INPP5D regulates inflammasome activation in human microglia. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7552. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.L.; Ma, X.T.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.F.; Yang, Y. Physical exercise induces hippocampal neurogenesis and prevents cognitive decline. Behav Brain Res 2017, 317, 332-339. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Godoy, A.C.; Frota, F.F.; Araújo, L.P.; Valenti, V.E.; Pereira, E.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Galhardi, C.M.; Caracio, F.C.; Haber, R.S.A.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Natural Antidepressants: Balancing Fire with Flora. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sahini, S.N.; Mohd Nor Hazalin, N.A.; Srikumar, B.N.; Jayasingh Chellammal, H.S.; Surindar Singh, G.K. Environmental enrichment improves cognitive function, learning, memory and anxiety-related behaviours in rodent models of dementia: Implications for future study. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2024, 208, 107880. [CrossRef]

- Methi, A.; Islam, M.R.; Kaurani, L.; Sakib, M.S.; Krüger, D.M.; Pena, T.; Burkhardt, S.; Liebetanz, D.; Fischer, A. A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of the Mouse Hippocampus After Voluntary Exercise. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, 5628-5645. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Bylykbashi, E.; Chatila, Z.K.; Lee, S.W.; Pulli, B.; Clemenson, G.D.; Kim, E.; Rompala, A.; Oram, M.K.; Asselin, C.; et al. Combined adult neurogenesis and BDNF mimic exercise effects on cognition in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Science 2018, 361. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C. Lifestyle Modulators of Neuroplasticity: How Physical Activity, Mental Engagement, and Diet Promote Cognitive Health during Aging. Neural Plast 2017, 2017, 3589271. [CrossRef]

- Asthana, A.; Tripathi, S.; Agarwal, R. Role of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as a Protective Factor in Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurol India 2024, 72, 1144-1151. [CrossRef]

- Rivers-Auty, J.; Mather, A.E.; Peters, R.; Lawrence, C.B.; Brough, D. Anti-inflammatories in Alzheimer's disease-potential therapy or spurious correlate? Brain Commun 2020, 2, fcaa109. [CrossRef]

- Cetin, A.; Komai, S.; Eliava, M.; Seeburg, P.H.; Osten, P. Stereotaxic gene delivery in the rodent brain. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 3166-3173. [CrossRef]

- Kalincik, T.; Roos, I.; Sharmin, S. Observational studies of treatment effectiveness in neurology. Brain 2023, 146, 4799-4808. [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, A.J.; Dierickx, K. A Tale of Two Chimeras: Applying the Six Principles to Human Brain Organoid Xenotransplantation. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2023, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Erler, A. Human brain organoid transplantation: testing the foundations of animal research ethics. Neuroethics 2024, 17, 20.

- Neziri, S.; Köseoğlu, A.E.; Deniz Köseoğlu, G.; Özgültekin, B.; Özgentürk, N. Animal models in neuroscience with alternative approaches: Evolutionary, biomedical, and ethical perspectives. Animal Model Exp Med 2024, 7, 868-880. [CrossRef]

- Mrza, M.A.; He, J.; Wang, Y. Integration of iPSC-Derived Microglia into Brain Organoids for Neurological Research. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, S.T.; Mansour, A.A.; Schlachetzki, J.C.M.; Pena, M.; Ghassemzadeh, S.; Mitchell, L.; Mar, A.; Quang, D.; Stumpf, S.; Ortiz, I.S.; et al. An in vivo neuroimmune organoid model to study human microglia phenotypes. Cell 2023, 186, 2111-2126.e2120. [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z.; Cai, H.; Wu, Z.; Song, S.; Karahan, H.; Kim, B.; Lu, H.C.; Kim, J.; Mackie, K.; Guo, F. Tubular human brain organoids to model microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 2751-2762. [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, G.L.O.; Santos, L.; Osman, N.; Lamas, C.B.; Laurindo, L.F.; Pomini, K.T.; Guissoni, L.M.; Lima, E.P.; Goulart, R.A.; Catharin, V.; et al. Ginkgo biloba: A Leaf of Hope in the Fight against Alzheimer's Dementia: Clinical Trial Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]