Submitted:

03 May 2024

Posted:

07 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

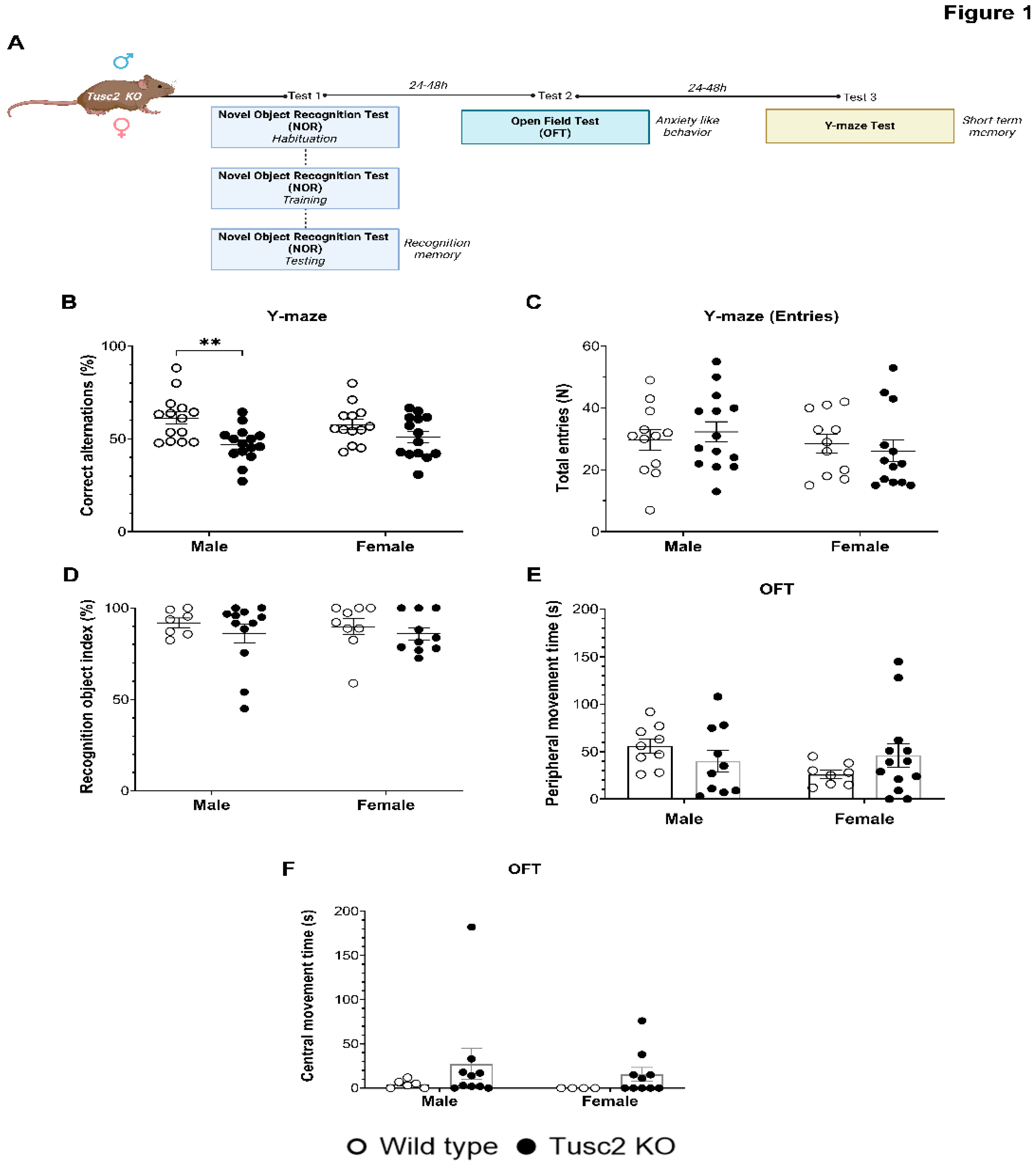

2.1. Loss of Tusc2 Caused Deficits in Hippocampal-Dependent Short-Term Spatial Memory

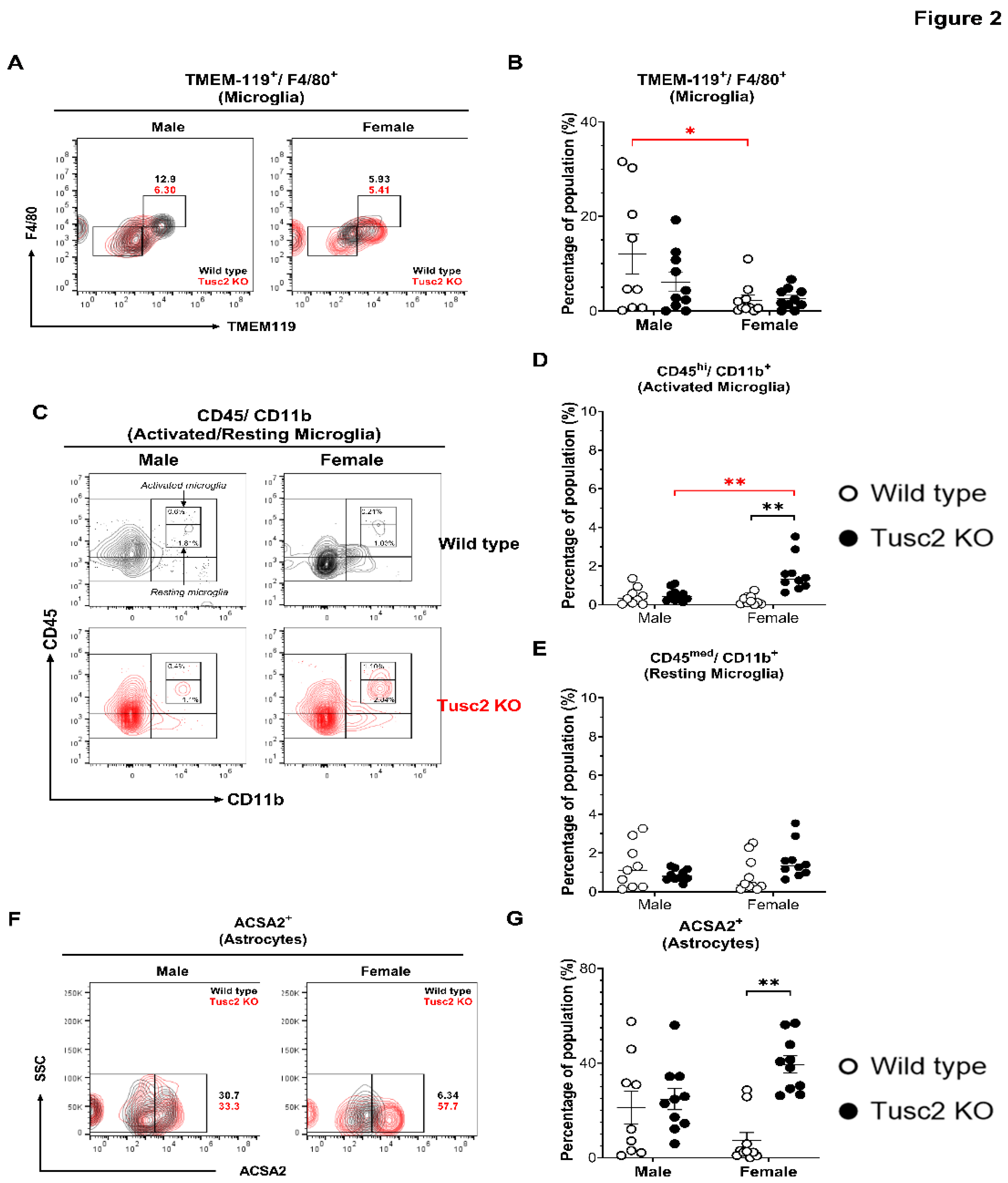

2.2. Tusc2- and Sex-Dependent Changes in Brain Immune Populations

2.2.1. Tusc2 Deficiency Causes Astrogliosis and Increased Proinflammatory Immune Subtypes

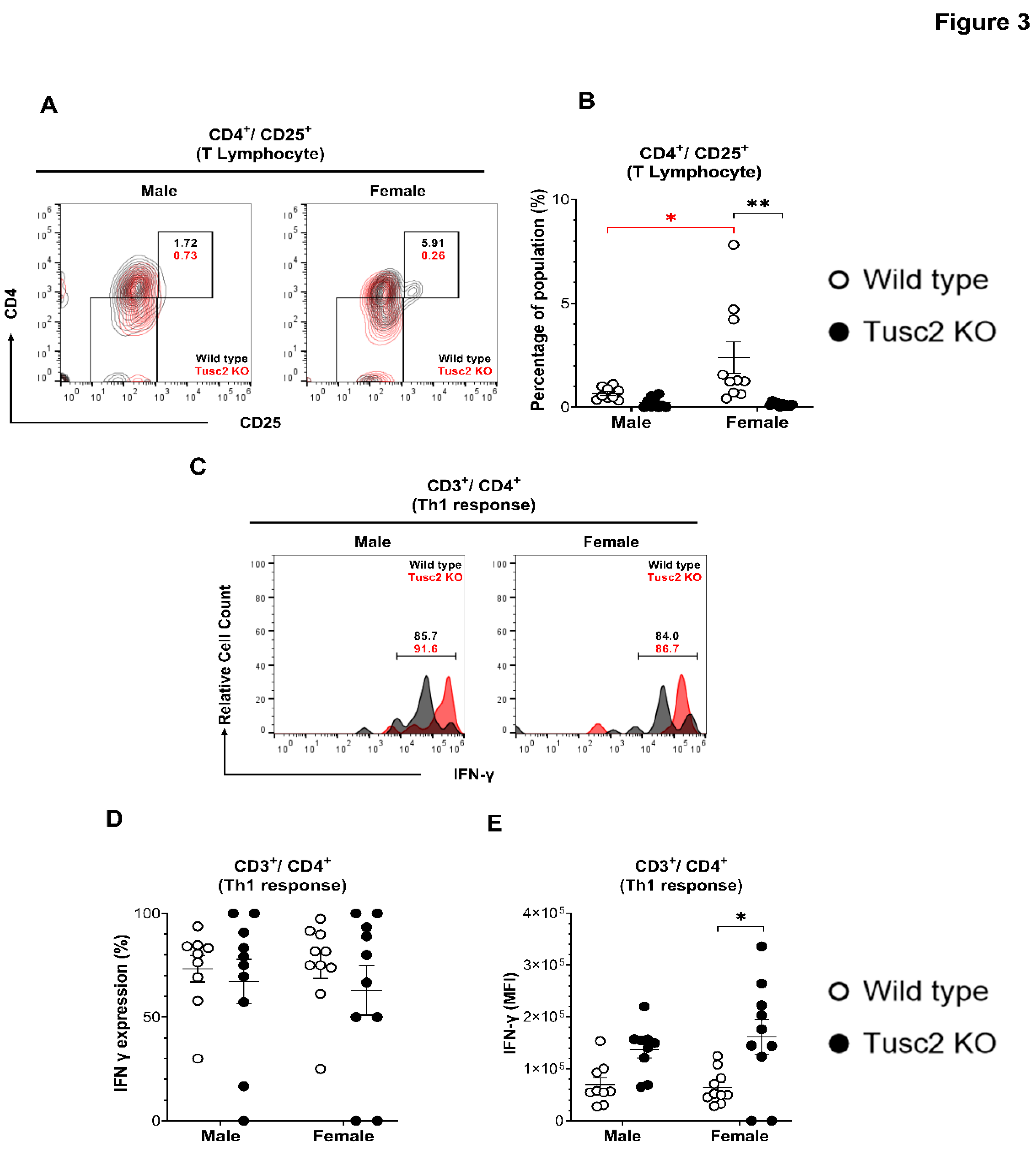

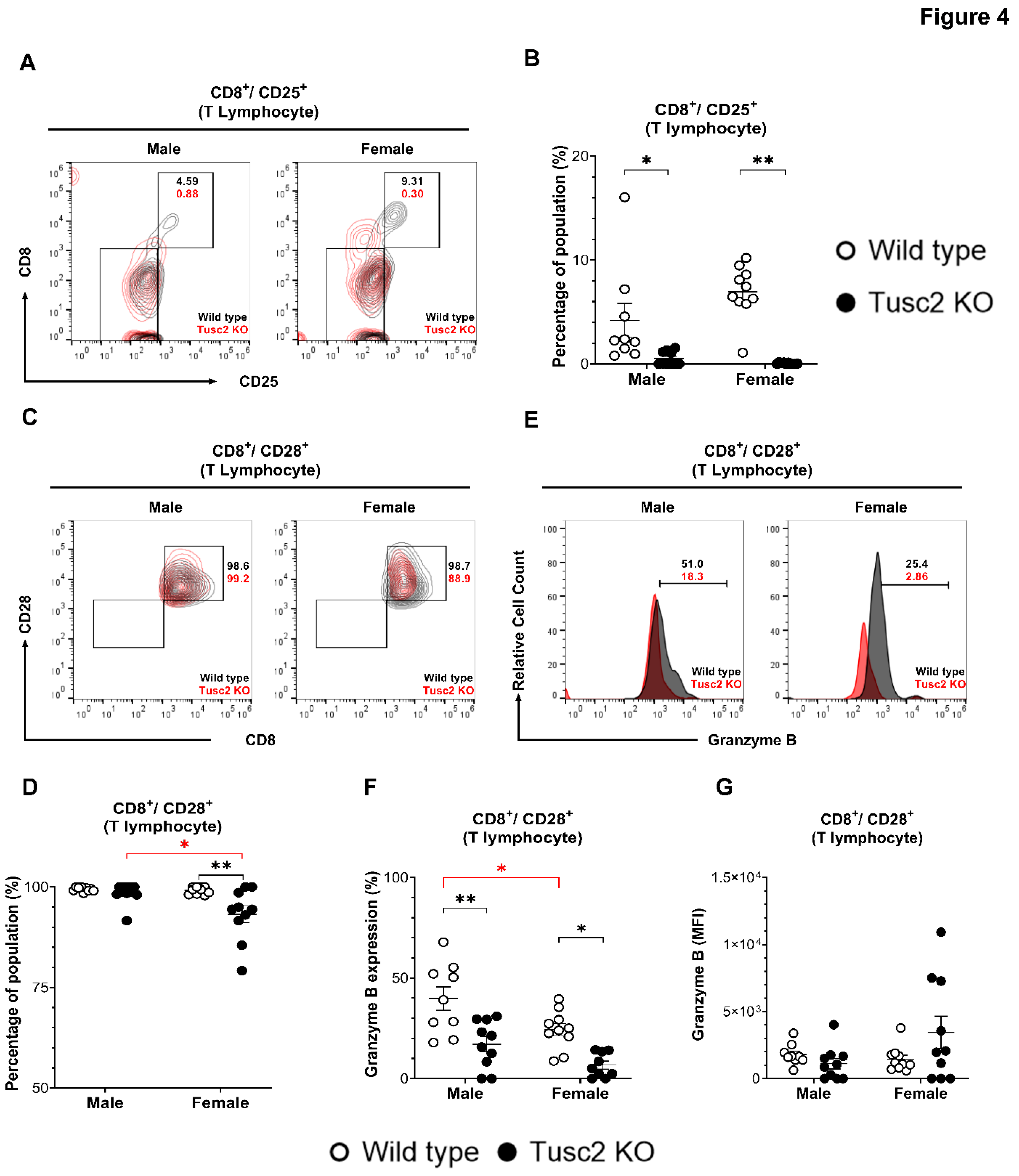

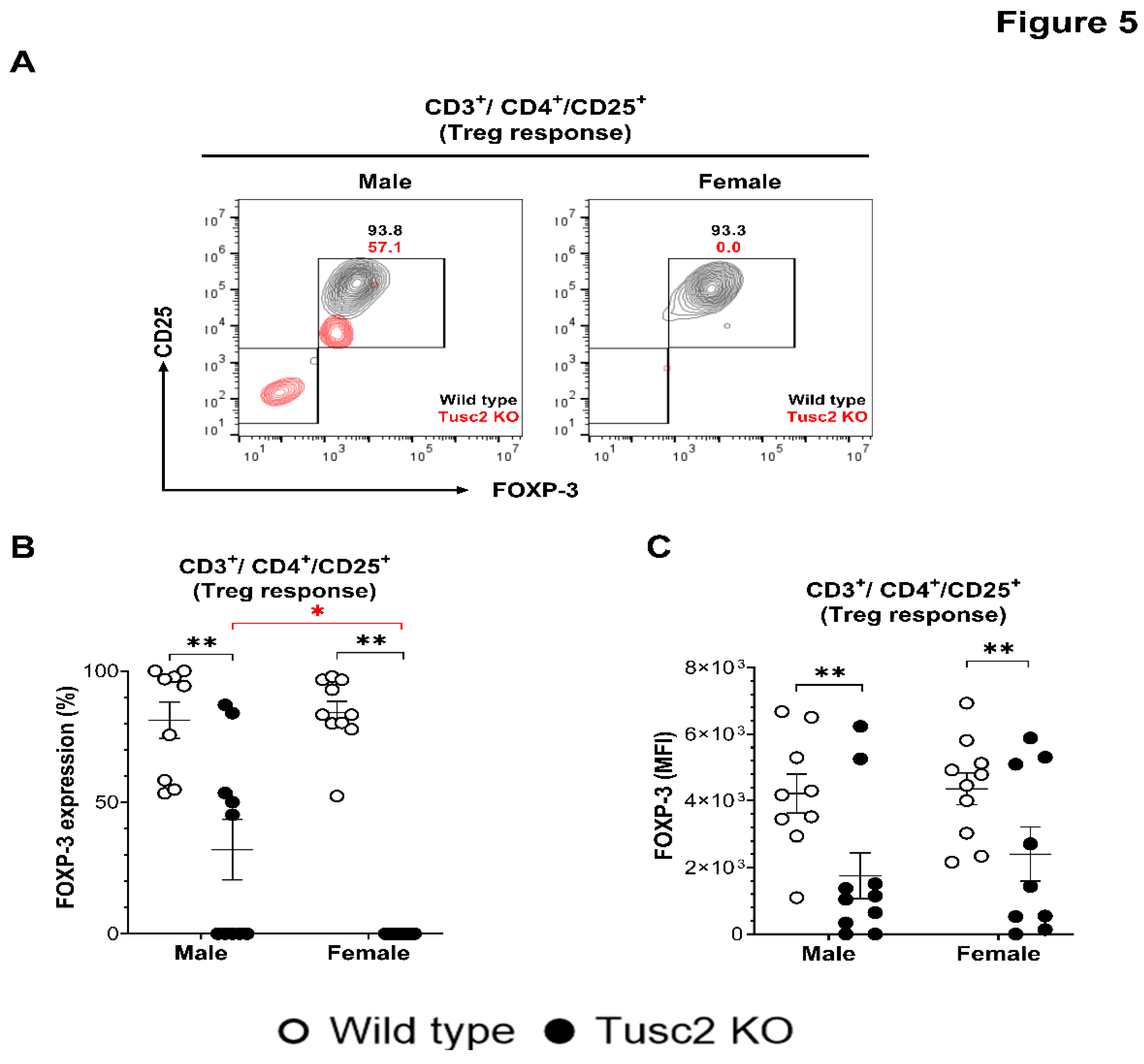

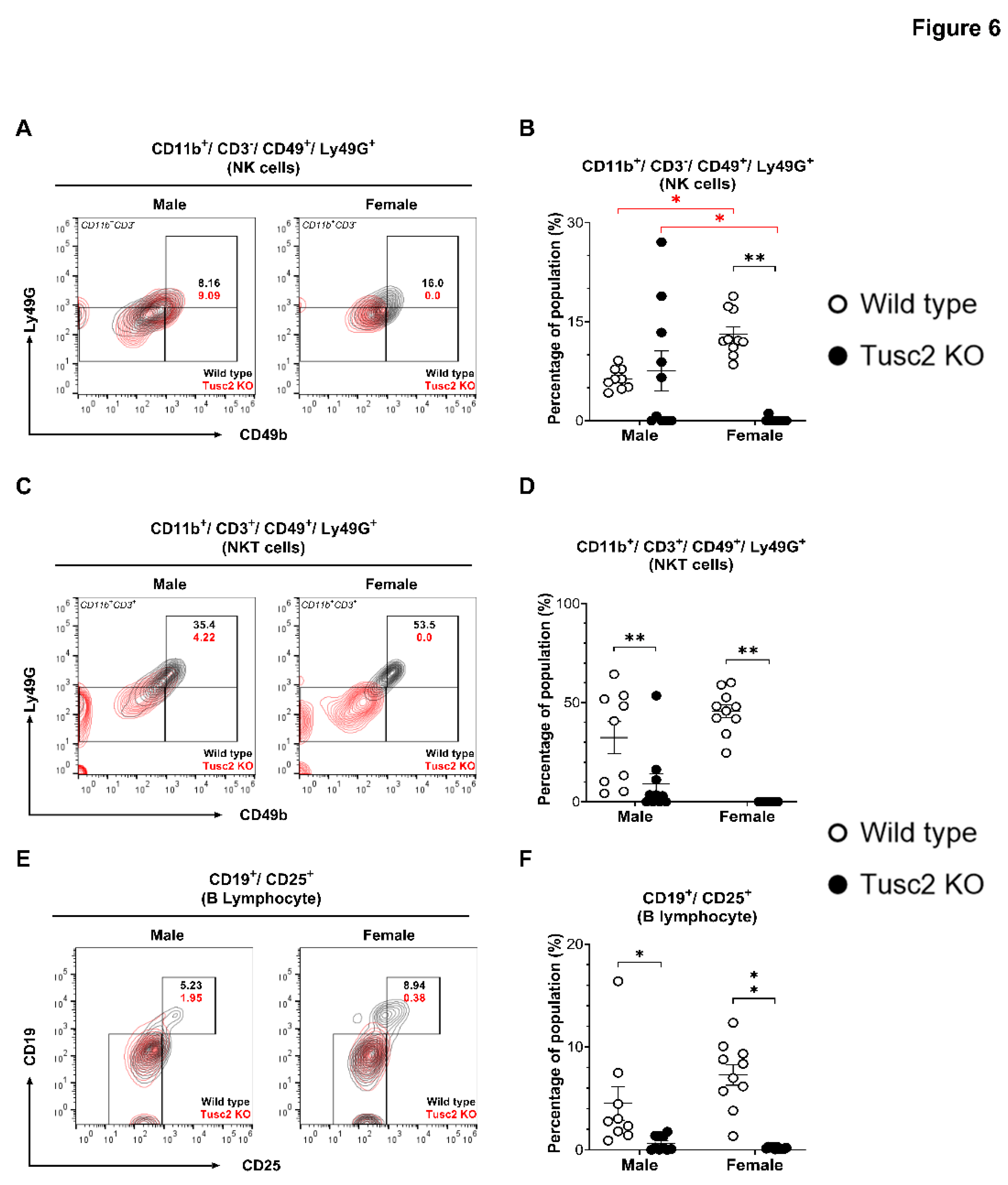

2.2.2. Tusc2 Deficiency Impairs Anti-Inflammatory Immune Populations.

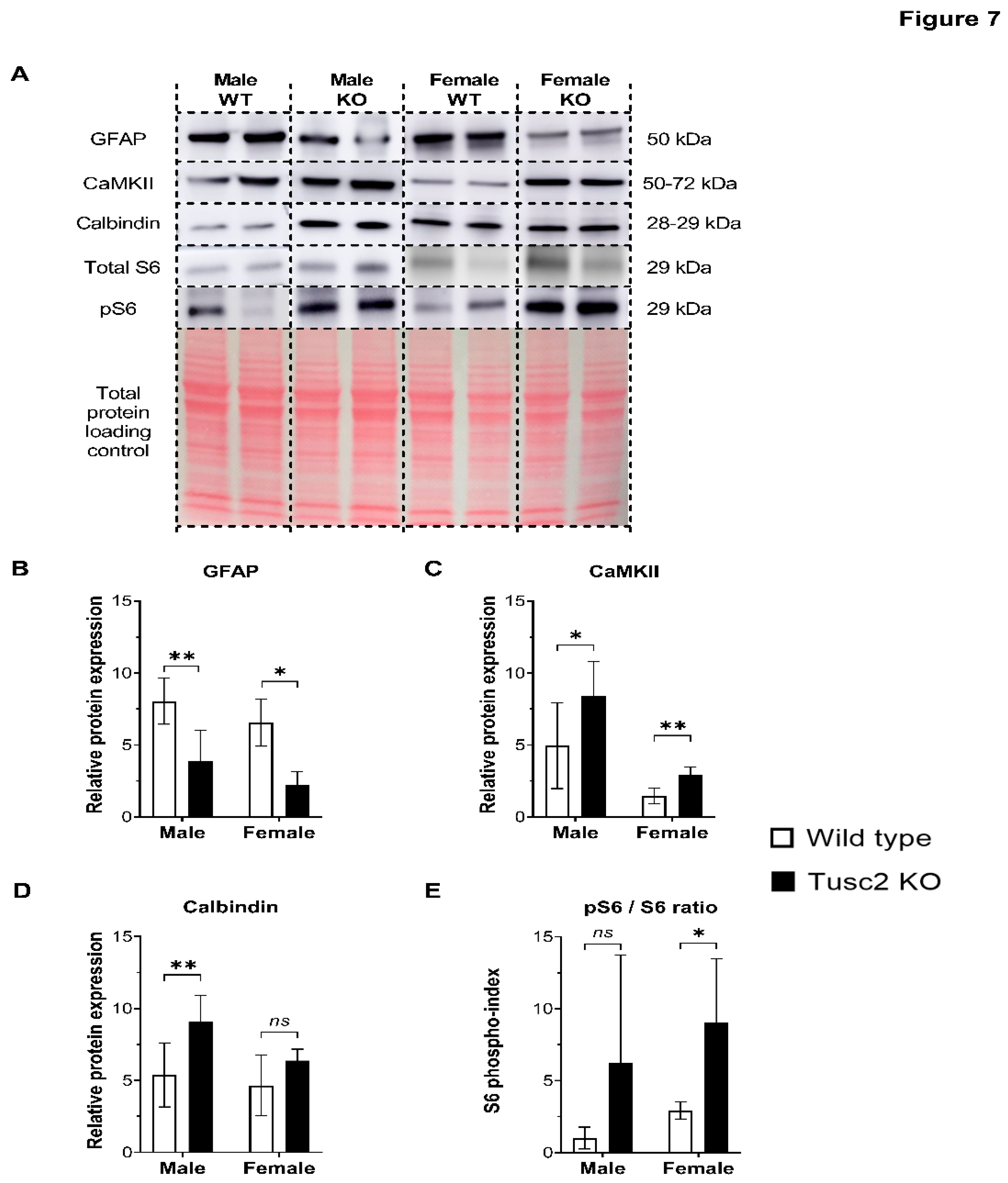

2.3. Tusc2 Is Essential for the Homeostasis of Some Important CNS Proteins Regulating Intracellular Ca2+ Dynamics and Synaptic Plasticity.

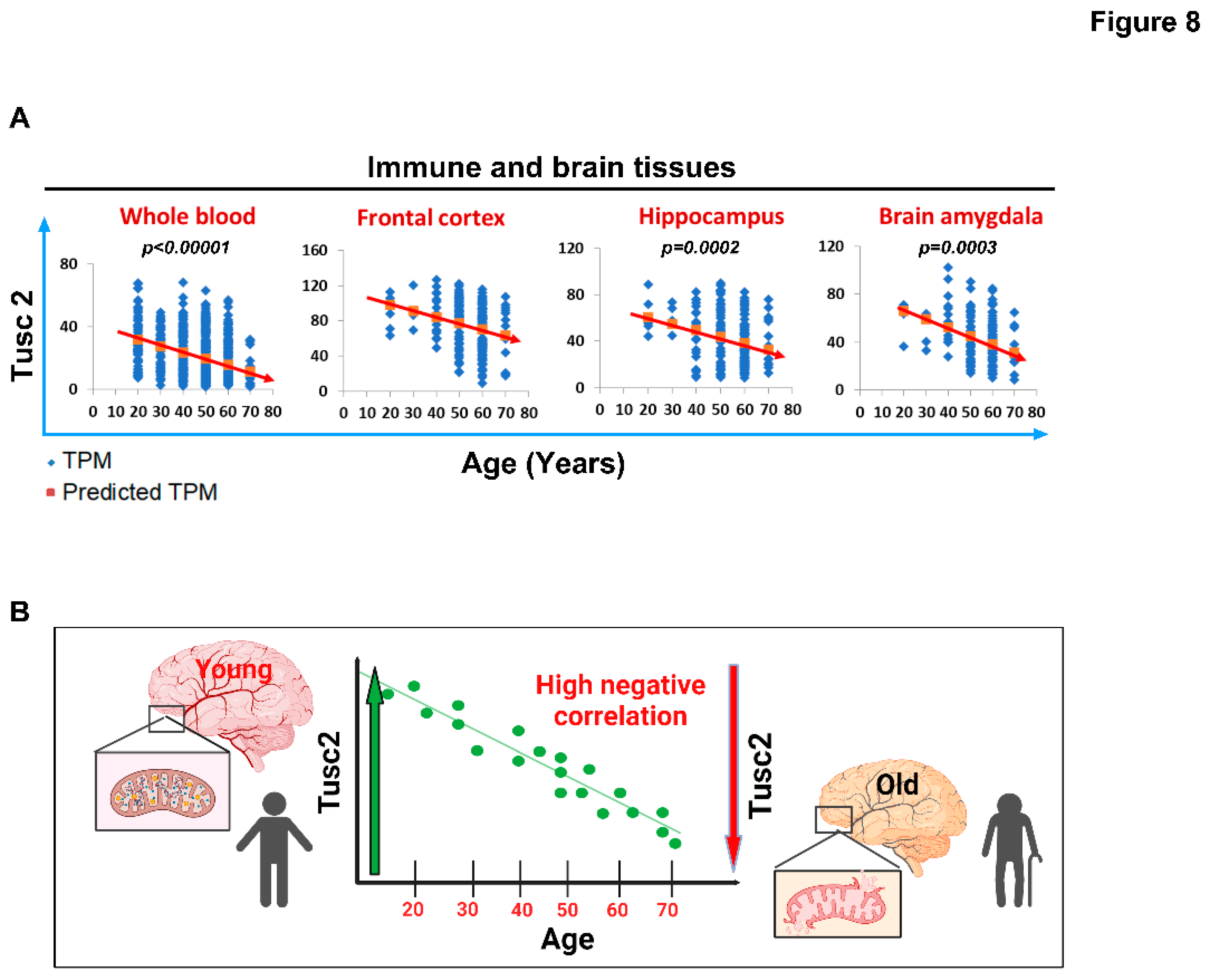

2.4. Human Tusc2 RNA Levels Progressively and Significantly Decrease with Age across Various Brain and Immune Tissues.

3. Discussion

3.1. Conclusion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. MICE

4.2. Behavioral Testing

4.3. Novel Object Recognition Test

4.4. Open Field/Locomotor Activity Test

4.5. Y-Maze Test

4.5. Western Blot Analysis

4.6. Isolation of Brain Immune Cells.

4.7. Cell Staining and Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yankner BA, Lu T, Loerch P. The aging brain. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2008;3:41-66.

- Vina J, Lloret A. Why women have more Alzheimer's disease than men: gender and mitochondrial toxicity of amyloid-β peptide. Journal of Alzheimer's disease. 2010;20(s2):S527-S33.

- Au B, Dale-McGrath S, Tierney MC. Sex differences in the prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Ageing research reviews. 2017;35:176-99. [CrossRef]

- Podcasy JL, Epperson CN. Considering sex and gender in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2016;18(4):437-46. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugan S, Epperson CN. Estrogen and the prefrontal cortex: towards a new understanding of estrogen's effects on executive functions in the menopause transition. Human brain mapping. 2014;35(3):847-65.

- Bailey M, Wang AC, Hao J, Janssen WG, Hara Y, Dumitriu D, et al. Interactive effects of age and estrogen on cortical neurons: implications for cognitive aging. Neuroscience. 2011;191:148-58. [CrossRef]

- Ward A, Tardiff S, Dye C, Arrighi HM. Rate of conversion from prodromal Alzheimer's disease to Alzheimer's dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2013;3(1):320-32.

- Uzhachenko R, Issaeva N, Boyd K, Ivanov SV, Carbone DP, Ivanova AV. Tumour suppressor Fus1 provides a molecular link between inflammatory response and mitochondrial homeostasis. J Pathol. 2012;227(4):456-69. [CrossRef]

- Uzhachenko R, Ivanov SV, Yarbrough WG, Shanker A, Medzhitov R, Ivanova AV. Fus1/Tusc2 is a novel regulator of mitochondrial calcium handling, Ca2+-coupled mitochondrial processes, and Ca2+-dependent NFAT and NF-kappaB pathways in CD4+ T cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(10):1533-47.

- Tan WJT, Song L, Graham M, Schettino A, Navaratnam D, Yarbrough WG, et al. Novel Role of the Mitochondrial Protein Fus1 in Protection from Premature Hearing Loss via Regulation of Oxidative Stress and Nutrient and Energy Sensing Pathways in the Inner Ear. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;27(8):489-509.

- Uzhachenko R, Boyd K, Olivares-Villagomez D, Zhu Y, Goodwin JS, Rana T, et al. Mitochondrial protein Fus1/Tusc2 in premature aging and age-related pathologies: critical roles of calcium and energy homeostasis. Aging. 2017;9(3):627-49.

- Hood MI, Uzhachenko R, Boyd K, Skaar EP, Ivanova AV. Loss of mitochondrial protein Fus1 augments host resistance to Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Infect Immun. 2013;81(12):4461-9. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova A, Ivanov S, Pascal V, Lumsden J, Ward J, Morris N, et al. Autoimmunity, spontaneous tumourigenesis, and IL-15 insufficiency in mice with a targeted disruption of the tumour suppressor gene Fus1. The Journal of Pathology. 2007;211(5):591-601.

- Wilson DM, 3rd, Cookson MR, Van Den Bosch L, Zetterberg H, Holtzman DM, Dewachter I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. 2023;186(4):693-714.

- Supnet C, Bezprozvanny I. Neuronal calcium signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease. 2010;20(s2):S487-S98.

- Passaro AP, Lebos AL, Yao Y, Stice SL. Immune Response in Neurological Pathology: Emerging Role of Central and Peripheral Immune Crosstalk. Front Immunol. 2021;12:676621. [CrossRef]

- Kolliker-Frers R, Udovin L, Otero-Losada M, Kobiec T, Herrera MI, Palacios J, et al. Neuroinflammation: An Integrating Overview of Reactive-Neuroimmune Cell Interactions in Health and Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2021;2021:9999146. [CrossRef]

- Coronas-Samano G, Baker KL, Tan WJ, Ivanova AV, Verhagen JV. Fus1 KO Mouse As a Model of Oxidative Stress-Mediated Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease: Circadian Disruption and Long-Term Spatial and Olfactory Memory Impairments. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:268.

- Newcombe EA, Camats-Perna J, Silva ML, Valmas N, Huat TJ, Medeiros R. Inflammation: the link between comorbidities, genetics, and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):1-26. [CrossRef]

- Chen H-R, Chen C-W, Kuo Y-M, Chen B, Kuan IS, Huang H, et al. Monocytes promote acute neuroinflammation and become pathological microglia in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Theranostics. 2022;12(2):512. [CrossRef]

- Sharma K, Schmitt S, Bergner CG, Tyanova S, Kannaiyan N, Manrique-Hoyos N, et al. Cell type–and brain region–resolved mouse brain proteome. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18(12):1819-31.

- Podd BS, Thoits J, Whitley N, Cheng H-Y, Kudla KL, Taniguchi H, et al. T cells in cryptopatch aggregates share TCR γ variable region junctional sequences with γδ T cells in the small intestinal epithelium of mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(11):6532-42. [CrossRef]

- Gern BH, Adams KN, Plumlee CR, Stoltzfus CR, Shehata L, Moguche AO, et al. TGFβ restricts expansion, survival, and function of T cells within the tuberculous granuloma. Cell host & microbe. 2021;29(4):594-606. e6. [CrossRef]

- Willingham S, Ho P, Hotson A, Hill C, Piccione E, Hsieh J, et al. A2AR antagonism with CPI-444 induces antitumor responses and augments efficacy to anti-PD-(L) 1 and anti-CTLA-4 in preclinical models. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018; 6: 1136–1149. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066. A preclinical study of CPI-444, an inhibitor of adenosine pathway that places it as an attractive immunotherapy target Article CAS. [CrossRef]

- Salei N, Rambichler S, Salvermoser J, Papaioannou NE, Schuchert R, Pakalniškytė D, et al. The kidney contains ontogenetically distinct dendritic cell and macrophage subtypes throughout development that differ in their inflammatory properties. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2020;31(2):257-78. [CrossRef]

- Jia B. Commentary: Gut microbiome–mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Frontiers in immunology. 2019;10:440898. [CrossRef]

- Leclerc M, Voilin E, Gros G, Corgnac S, de Montpréville V, Validire P, et al. Regulation of antitumour CD8 T-cell immunity and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy by Neuropilin-1. Nature Communications. 2019;10(1):3345. [CrossRef]

- Komuczki J, Tuzlak S, Friebel E, Hartwig T, Spath S, Rosenstiel P, et al. Fate-mapping of GM-CSF expression identifies a discrete subset of inflammation-driving T helper cells regulated by cytokines IL-23 and IL-1β. Immunity. 2019;50(5):1289-304. e6. [CrossRef]

- Kao C, Daniels MA, Jameson SC. Loss of CD8 and TCR binding to Class I MHC ligands following T cell activation. International immunology. 2005;17(12):1607-17. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Weng D, Chen Y, Song L, Li C, Dong L, et al. Depletion of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells with anti-CD25 antibody may exacerbate the 1, 3-β-glucan-induced lung inflammatory response in mice. Archives of toxicology. 2011;85:1383-94.

- Perlot T, Penninger JM. Development and function of murine B cells lacking RANK. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(3):1201-5. [CrossRef]

- Schädlich IS, Vienhues JH, Jander A, Piepke M, Magnus T, Lambertsen KL, et al. Interleukin-1 mediates ischemic brain injury via induction of IL-17A in γδ T cells and CXCL1 in astrocytes. NeuroMolecular Medicine. 2022;24(4):437-51. [CrossRef]

- Glaubitz J, Wilden A, Frost F, Ameling S, Homuth G, Mazloum H, et al. Activated regulatory T-cells promote duodenal bacterial translocation into necrotic areas in severe acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2023;72(7):1355-69. [CrossRef]

- Altendorfer B, Unger MS, Poupardin R, Hoog A, Asslaber D, Gratz IK, et al. Transcriptomic profiling identifies CD8+ T cells in the brain of aged and alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice as tissue-resident memory T cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2022;209(7):1272-85. [CrossRef]

- Steinbach K, Vincenti I, Kreutzfeldt M, Page N, Muschaweckh A, Wagner I, et al. Brain-resident memory T cells represent an autonomous cytotoxic barrier to viral infection. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2016;213(8):1571-87. [CrossRef]

- Smolders J, Heutinck KM, Fransen NL, Remmerswaal EB, Hombrink P, Ten Berge IJ, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells populate the human brain. Nature communications. 2018;9(1):4593. [CrossRef]

- Young KG, MacLean S, Dudani R, Krishnan L, Sad S. CD8+ T cells primed in the periphery provide time-bound immune-surveillance to the central nervous system. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;187(3):1192-200. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Zas I, Lemarié J, Zlatanova I, Cachanado M, Seghezzi J-C, Benamer H, et al. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells promote granzyme B-dependent adverse post-ischemic cardiac remodeling. Nature communications. 2021;12(1):1483.

- Krämer TJ, Hack N, Brühl TJ, Menzel L, Hummel R, Griemert E-V, et al. Depletion of regulatory T cells increases T cell brain infiltration, reactive astrogliosis, and interferon-γ gene expression in acute experimental traumatic brain injury. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2019;16:1-14.

- Pasciuto E, Burton OT, Roca CP, Lagou V, Rajan WD, Theys T, et al. Microglia require CD4 T cells to complete the fetal-to-adult transition. Cell. 2020;182(3):625-40. e24. [CrossRef]

- Fritzsching B, Haas J, König F, Kunz P, Fritzsching E, Pöschl J, et al. Intracerebral human regulatory T cells: analysis of CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ T cells in brain lesions and cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients. PloS one. 2011;6(3):e17988. [CrossRef]

- Ma C, Li S, Hu Y, Ma Y, Wu Y, Wu C, et al. AIM2 controls microglial inflammation to prevent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2021;218(5). [CrossRef]

- Grubman A, Chew G, Ouyang JF, Sun G, Choo XY, McLean C, et al. A single-cell atlas of entorhinal cortex from individuals with Alzheimer’s disease reveals cell-type-specific gene expression regulation. Nature neuroscience. 2019;22(12):2087-97. [CrossRef]

- Clancy-Thompson E, Chen GZ, LaMarche NM, Ali LR, Jeong HJ, Crowley SJ, et al. Transnuclear mice reveal Peyer's patch iNKT cells that regulate B-cell class switching to IgG1. The EMBO Journal. 2019;38(14):e101260.

- Klezovich-Bénard M, Corre J-P, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Fiole D, Burjek N, Tournier J-N, et al. Mechanisms of NK cell-macrophage Bacillus anthracis crosstalk: a balance between stimulation by spores and differential disruption by toxins. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8(1):e1002481. [CrossRef]

- Li Z-Y, Song Z-H, Meng C-Y, Yang D-D, Yang Y, Peng J-P. IFN-γ modulates Ly-49 receptors on NK cells in IFN-γ-induced pregnancy failure. Scientific reports. 2015;5(1):18159.

- Hemonnot A-L, Hua J, Ulmann L, Hirbec H. Microglia in Alzheimer disease: well-known targets and new opportunities. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2019;11:233. [CrossRef]

- González-Reyes RE, Nava-Mesa MO, Vargas-Sánchez K, Ariza-Salamanca D, Mora-Muñoz L. Involvement of astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease from a neuroinflammatory and oxidative stress perspective. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2017;10:427. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti M, Merlini M, Späni C, Gericke C, Schweizer N, Enzmann G, et al. T-cell brain infiltration and immature antigen-presenting cells in transgenic models of Alzheimer’s disease-like cerebral amyloidosis. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2016;54:211-25. [CrossRef]

- Lugli A, Iezzi G, Hostettler I, Muraro M, Mele V, Tornillo L, et al. Prognostic impact of the expression of putative cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD166, CD44s, EpCAM, and ALDH1 in colorectal cancer. British journal of cancer. 2010;103(3):382-90. [CrossRef]

- Bernier L-P, York EM, Kamyabi A, Choi HB, Weilinger NL, MacVicar BA. Microglial metabolic flexibility supports immune surveillance of the brain parenchyma. Nature communications. 2020;11(1):1559. [CrossRef]

- Calvo B, Rubio F, Fernández M, Tranque P. Dissociation of neonatal and adult mice brain for simultaneous analysis of microglia, astrocytes and infiltrating lymphocytes by flow cytometry. IBRO reports. 2020;8:36-47. [CrossRef]

- Srakočić S, Josić P, Trifunović S, Gajović S, Grčević D, Glasnović A. Proposed practical protocol for flow cytometry analysis of microglia from the healthy adult mouse brain: Systematic review and isolation methods’ evaluation. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2022;16:1017976. [CrossRef]

- Brochard V, Combadière B, Prigent A, Laouar Y, Perrin A, Beray-Berthat V, et al. Infiltration of CD4+ lymphocytes into the brain contributes to neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;119(1). [CrossRef]

- Williams GP, Schonhoff AM, Jurkuvenaite A, Gallups NJ, Standaert DG, Harms AS. CD4 T cells mediate brain inflammation and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2021;144(7):2047-59.

- Hu D, Xia W, Weiner HL. CD8+ T cells in neurodegeneration: friend or foe? Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2022;17(1):1-4.

- Jadidi-Niaragh F, Shegarfi H, Naddafi F, Mirshafiey A. The role of natural killer cells in Alzheimer’s disease. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2012;76(5):451-6. [CrossRef]

- Van Kaer L, Parekh VV, Wu L. Invariant natural killer T cells: bridging innate and adaptive immunity. Cell and tissue research. 2011;343(1):43-55.

- Feng W, Zhang Y, Ding S, Chen S, Wang T, Wang Z, et al. B lymphocytes ameliorate Alzheimer’s disease-like neuropathology via interleukin-35. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2023;108:16-31. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Wang KK. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: from intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends in neurosciences. 2015;38(6):364-74. [CrossRef]

- Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3(3):175-90. [CrossRef]

- Junho CVC, Caio-Silva W, Trentin-Sonoda M, Carneiro-Ramos MS. An overview of the role of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in cardiorenal syndrome. Frontiers in physiology. 2020:735. [CrossRef]

- Lee S-JR, Escobedo-Lozoya Y, Szatmari EM, Yasuda R. Activation of CaMKII in single dendritic spines during long-term potentiation. Nature. 2009;458(7236):299-304. [CrossRef]

- Fairless R, Williams SK, Diem R. Calcium-Binding Proteins as Determinants of Central Nervous System Neuronal Vulnerability to Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9). [CrossRef]

- Kubo A, Misonou H, Matsuyama M, Nomori A, Wada-Kakuda S, Takashima A, et al. Distribution of endogenous normal tau in the mouse brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2019;527(5):985-98. [CrossRef]

- Yates SC, Zafar A, Hubbard P, Nagy S, Durant S, Bicknell R, et al. Dysfunction of the mTOR pathway is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica communications. 2013;1(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Coronas-Samano G, Baker KL, Tan WJ, Ivanova AV, Verhagen JV. Fus1 KO mouse as a model of oxidative stress-mediated sporadic Alzheimer's disease: circadian disruption and long-term spatial and olfactory memory impairments. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2016;8:268.

- Maurice T, Lockhart BP, Privat A. Amnesia induced in mice by centrally administered β-amyloid peptides involves cholinergic dysfunction. Brain research. 1996;706(2):181-93. [CrossRef]

- Deacon RM, Rawlins JNP. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nature protocols. 2006;1(1):7-12. [CrossRef]

- Prieur EA, Jadavji NM. Assessing spatial working memory using the spontaneous alternation Y-maze test in aged male mice. Bio-protocol. 2019;9(3):e3162-e. [CrossRef]

- Kankaanpaa A, Tolvanen A, Saikkonen P, Heikkinen A, Laakkonen EK, Kaprio J, et al. Do Epigenetic Clocks Provide Explanations for Sex Differences in Life Span? A Cross-Sectional Twin Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(9):1898-906. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad MA, Kareem O, Khushtar M, Akbar M, Haque MR, Iqubal A, et al. Neuroinflammation: A Potential Risk for Dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2). [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Holtzman DM. Emerging roles of innate and adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Immunity. 2022;55(12):2236-54. [CrossRef]

- Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJ. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 2):288-95. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Barres BA. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2018;18(4):225-42. [CrossRef]

- Gao C, Jiang J, Tan Y, Chen S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2023;8(1):359. [CrossRef]

- Gao M-L, Zhang X, Han F, Xu J, Yu S-J, Jin K, et al. Functional microglia derived from human pluripotent stem cells empower retinal organs. Science China Life Sciences. 2022;65(6):1057-71. [CrossRef]

- Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nature genetics. 2019;51(3):404-13. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Park J, Choi YK. The Role of Astrocytes in the Central Nervous System Focused on BK Channel and Heme Oxygenase Metabolites: A Review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019;8(5). [CrossRef]

- Colombo E, Farina C. Astrocytes: Key Regulators of Neuroinflammation. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(9):608-20. [CrossRef]

- Mira RG, Lira M, Cerpa W. Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanisms of Glial Response. Front Physiol. 2021;12:740939. [CrossRef]

- Uzhachenko R, Shanker A, Yarbrough WG, Ivanova AV. Mitochondria, calcium, and tumor suppressor Fus1: At the crossroad of cancer, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Oncotarget. 2015;6(25):20754-72. [CrossRef]

- Uzhachenko R, Shimamoto A, Chirwa SS, Ivanov SV, Ivanova AV, Shanker A. Mitochondrial Fus1/Tusc2 and cellular Ca2(+) homeostasis: tumor suppressor, anti-inflammatory and anti-aging implications. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022.

- Matejuk A, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Cross-Talk of the CNS With Immune Cells and Functions in Health and Disease. Front Neurol. 2021;12:672455. [CrossRef]

- Sankowski R, Mader S, Valdes-Ferrer SI. Systemic inflammation and the brain: novel roles of genetic, molecular, and environmental cues as drivers of neurodegeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:28. [CrossRef]

- Radpour M, Khoshkroodian B, Asgari T, Pourbadie HG, Sayyah M. Interleukin 4 Reduces Brain Hyperexcitability after Traumatic Injury by Downregulating TNF-alpha, Upregulating IL-10/TGF-beta, and Potential Directing Macrophage/Microglia to the M2 Anti-inflammatory Phenotype. Inflammation. 2023;46(5):1810-31.

- Chen X, Zhang J, Song Y, Yang P, Yang Y, Huang Z, et al. Deficiency of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 leads to neural hyperexcitability and aggravates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10(9):1634-45. [CrossRef]

- Song L, Chen J, Lo CZ, Guo Q, Consortium ZIB, Feng J, et al. Impaired type I interferon signaling activity implicated in the peripheral blood transcriptome of preclinical Alzheimer's disease. EBioMedicine. 2022;82:104175.

- Vellecco V, Saviano A, Raucci F, Casillo GM, Mansour AA, Panza E, et al. Interleukin-17 (IL-17) triggers systemic inflammation, peripheral vascular dysfunction, and related prothrombotic state in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol Res. 2023;187:106595.

- DeMaio A, Mehrotra S, Sambamurti K, Husain S. The role of the adaptive immune system and T cell dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):251. [CrossRef]

- Faridar A, Vasquez M, Thome AD, Yin Z, Xuan H, Wang JH, et al. Ex vivo expanded human regulatory T cells modify neuroinflammation in a preclinical model of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022;10(1):144. [CrossRef]

- Kann O, Almouhanna F, Chausse B. Interferon γ: a master cytokine in microglia-mediated neural network dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Trends in Neurosciences. 2022;45(12):913-27. [CrossRef]

- Ta T-T, Dikmen HO, Schilling S, Chausse B, Lewen A, Hollnagel J-O, et al. Priming of microglia with IFN-γ slows neuronal gamma oscillations in situ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116(10):4637-42. [CrossRef]

- Baruch K, Deczkowska A, David E, Castellano JM, Miller O, Kertser A, et al. Aging-induced type I interferon response at the choroid plexus negatively affects brain function. Science. 2014;346(6205):89-93. [CrossRef]

- Browne TC, McQuillan K, McManus RM, O’Reilly J-A, Mills KH, Lynch MA. IFN-γ production by amyloid β–specific Th1 cells promotes microglial activation and increases plaque burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;190(5):2241-51.

- DeMaio A, Mehrotra S, Sambamurti K, Husain S. The role of the adaptive immune system and T cell dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):251. [CrossRef]

- Jorfi M, Park J, Hall CK, Lin C-CJ, Chen M, von Maydell D, et al. Infiltrating CD8+ T cells exacerbate Alzheimer’s disease pathology in a 3D human neuroimmune axis model. Nature neuroscience. 2023;26(9):1489-504. [CrossRef]

- Solana C, Tarazona R, Solana R. Immunosenescence of natural killer cells, inflammation, and Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2018;2018.

- Maghazachi AA. On the role of natural killer cells in neurodegenerative diseases. Toxins. 2013;5(2):363-75. [CrossRef]

- Qi C, Liu Q. Natural killer cells in aging and age-related diseases. Neurobiology of Disease. 2023;183:106156. [CrossRef]

- Lee H-N, Manangeeswaran M, Lewkowicz AP, Engel K, Chowdhury M, Garige M, et al. NK cells require immune checkpoint receptor LILRB4/gp49B to control neurotropic Zika virus infections in mice. JCI insight. 2022;7(3).

- Solerte S, Cravello L, Ferrari E, Fioravanti M. Overproduction of IFN-γ and TNF-α from natural killer (NK) cells is associated with abnormal NK reactivity and cognitive derangement in Alzheimer's disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;917(1):331-40.

- Zhang Y, Fung ITH, Sankar P, Chen X, Robison LS, Ye L, et al. Depletion of NK cells improves cognitive function in the Alzheimer disease mouse model. The Journal of Immunology. 2020;205(2):502-10. [CrossRef]

- Watte C, Nakamura T, Lau C, Ortaldo J, Stein-Streilein J. Ly49 C/I-dependent NKT cell-derived IL-10 is required for corneal graft survival and peripheral tolerance. Journal of Leucocyte Biology. 2008;83(4):928-35. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Wang KK. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: from intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38(6):364-74. [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Wilson NL, Sims CD, Hofmann JP, Anderson L, Shore AD, Torrey EF, et al. Disease-specific alterations in frontal cortex brain proteins in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. The Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5(2):142-9. [CrossRef]

- Kommers T, Vinade L, Pereira C, Goncalves CA, Wofchuk S, Rodnight R. Regulation of the phosphorylation of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) by glutamate and calcium ions in slices of immature rat spinal cord: comparison with immature hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1998;248(2):141-3. [CrossRef]

- Szpakowski P, Ksiazek-Winiarek D, Turniak-Kusy M, Pacan I, Glabinski A. Human Primary Astrocytes Differently Respond to Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Stimuli. Biomedicines. 2022;10(8). [CrossRef]

- Selmaj K, Shafit-Zagardo B, Aquino DA, Farooq M, Raine CS, Norton WT, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-induced proliferation of astrocytes from mature brain is associated with down-regulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein mRNA. J Neurochem. 1991;57(3):823-30. [CrossRef]

- Birck C, Ginolhac A, Pavlou MAS, Michelucci A, Heuschling P, Grandbarbe L. NF-kappaB and TNF Affect the Astrocytic Differentiation from Neural Stem Cells. Cells. 2021;10(4).

- Alzheimer's Association Calcium Hypothesis W. Calcium Hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease and brain aging: A framework for integrating new evidence into a comprehensive theory of pathogenesis. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(2):178-82 e17.

- Chrienova Z, Nepovimova E, Kuca K. The role of mTOR in age-related diseases. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2021;36(1):1678-92.

- Smith W, Rybczynski R. Prothoracicotropic hormone. Insect endocrinology. 2012:1-62.

- Ivanova A, Ivanov S, Pascal V, Lumsden J, Ward J, Morris N, et al. Autoimmunity, spontaneous tumourigenesis, and IL-15 insufficiency in mice with a targeted disruption of the tumour suppressor gene Fus1. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2007;211(5):591-601.

- Canas PM, Duarte JM, Rodrigues RJ, Köfalvi A, Cunha RA. Modification upon aging of the density of presynaptic modulation systems in the hippocampus. Neurobiology of aging. 2009;30(11):1877-84. [CrossRef]

- Leger M, Quiedeville A, Bouet V, Haelewyn B, Boulouard M, Schumann-Bard P, et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nature protocols. 2013;8(12):2531-7. [CrossRef]

- Lueptow LM. Novel object recognition test for the investigation of learning and memory in mice. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments). 2017(126):e55718.

- Sakamoto T, Sugimoto S, Uekita T. Effects of intraperitoneal and intracerebroventricular injections of oxytocin on social and emotional behaviors in pubertal male mice. Physiology & behavior. 2019;212:112701. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).