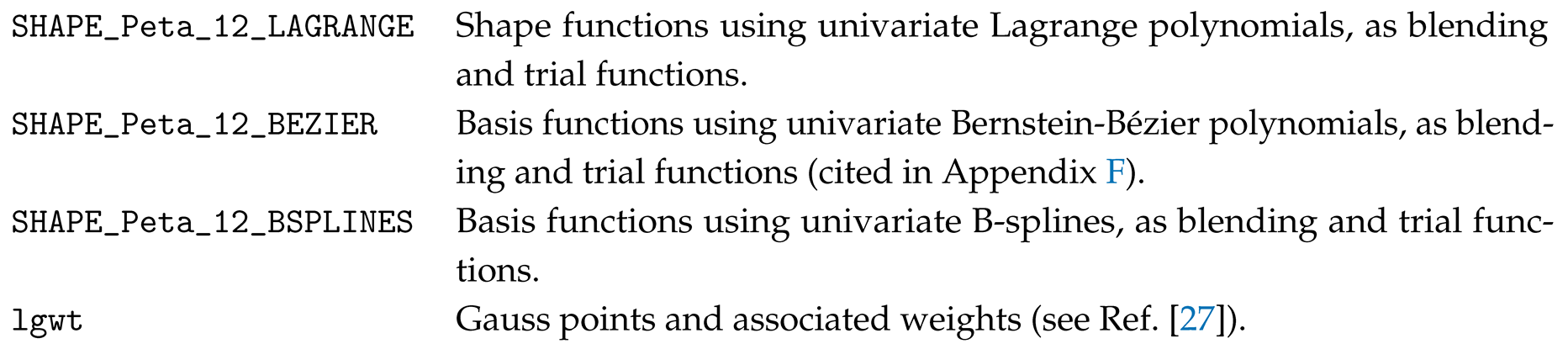

8.2.1. Coons-Patch Element

In this subsection, we investigate the convergence behavior of several models constructed using a single Coons-patch element, assuming the standard linear blending functions: , , where s denotes either of the parametric coordinates or .

As reviewed in Ref. [

9], previous studies have employed various cardinal trial functions, including:

(i) piecewise-linear functions,

(ii) cardinal natural cubic B-splines,

(iii) Lagrange polynomials.

In the present work, we extend this framework by also implementing non-uniform Lagrange polynomials and Cox–de Boor B-splines [

29,

30,

31].

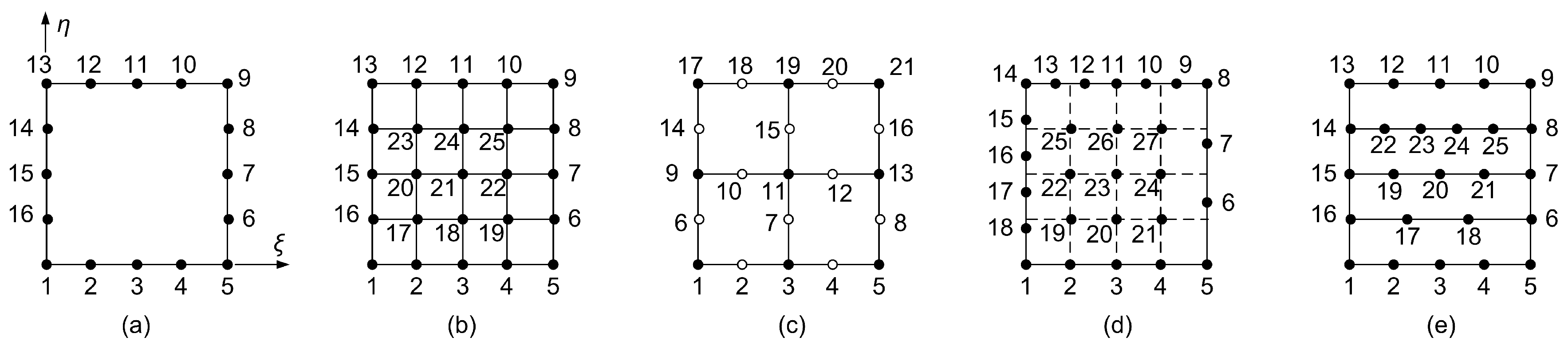

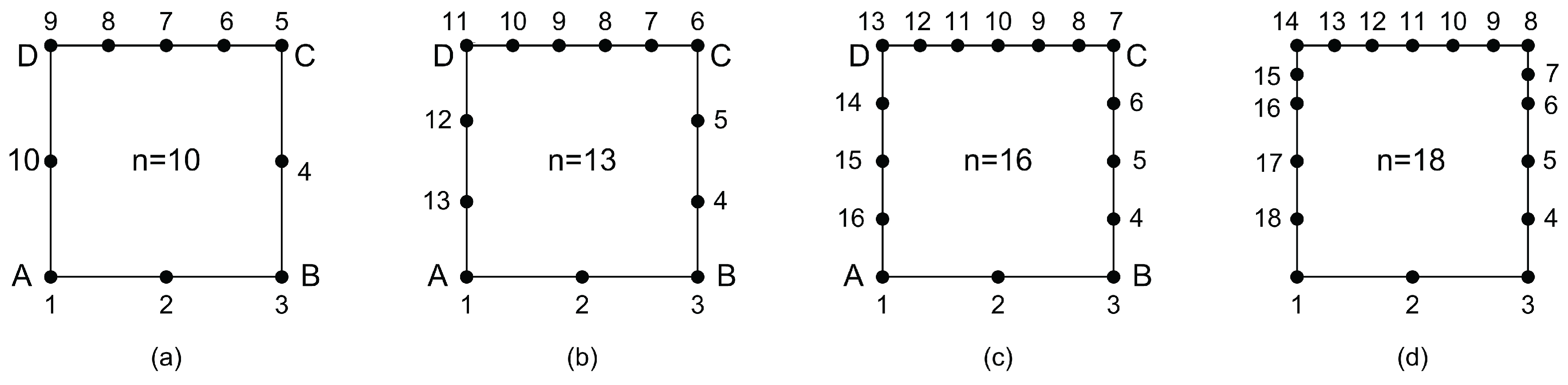

Although each edge of the Coons patch may consist of an arbitrary number of nodal or control points (each associated with degrees of freedom), for brevity of the presentation we assume equal number of points on opposite edges, as follows:

– The number of spans along the parallel edges is denoted .

– The number of spans along the edges is denoted .

For global Lagrange and Bernstein polynomials, the polynomial degrees in each parametric direction are

and

, respectively. Interpolation using piecewise-linear or Lagrange polynomials requires

and

nodal points per side in the

and

directions, respectively. These nodal points correspond to the breakpoints used in the Cox–de Boor formulation. For cubic Cox–de Boor B-splines, the number of control points per edge exceeds the number of breakpoints by two (e.g.,

) [

26].

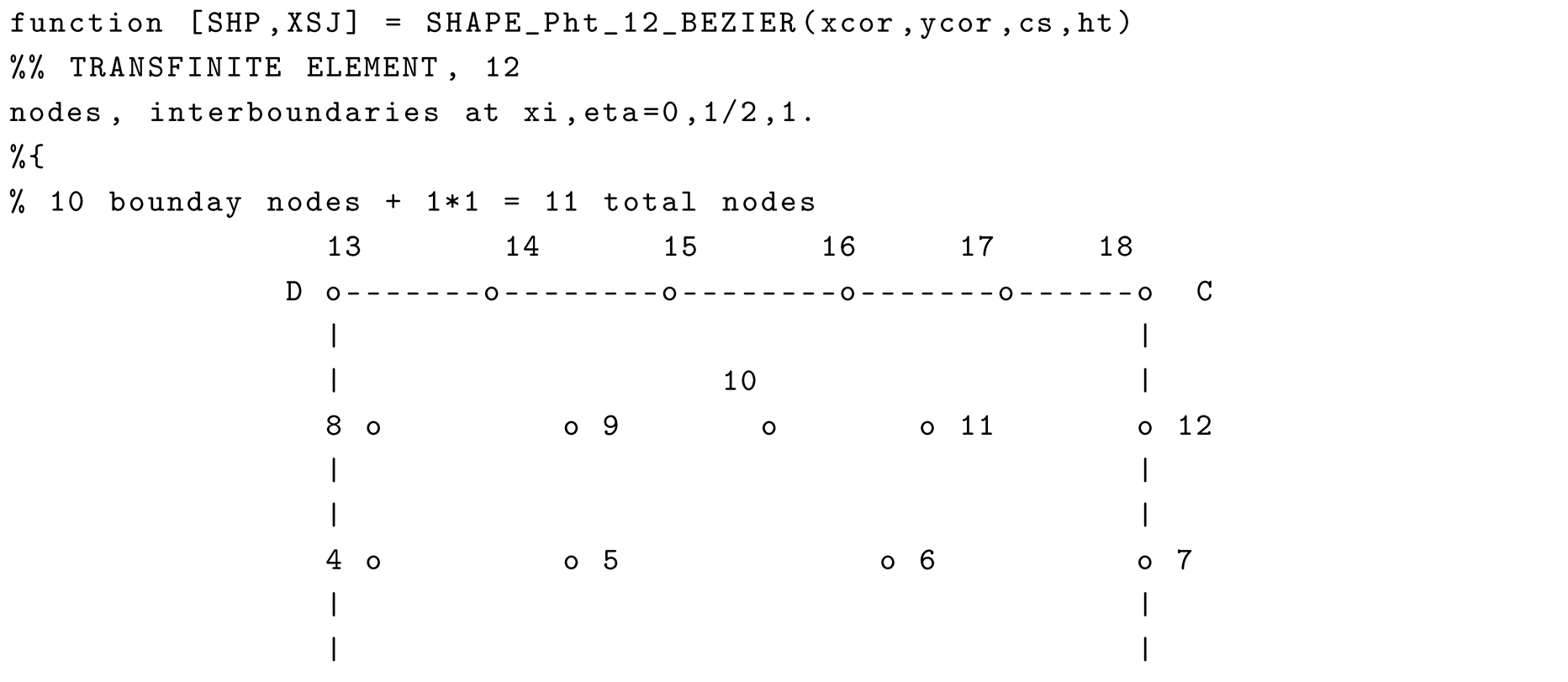

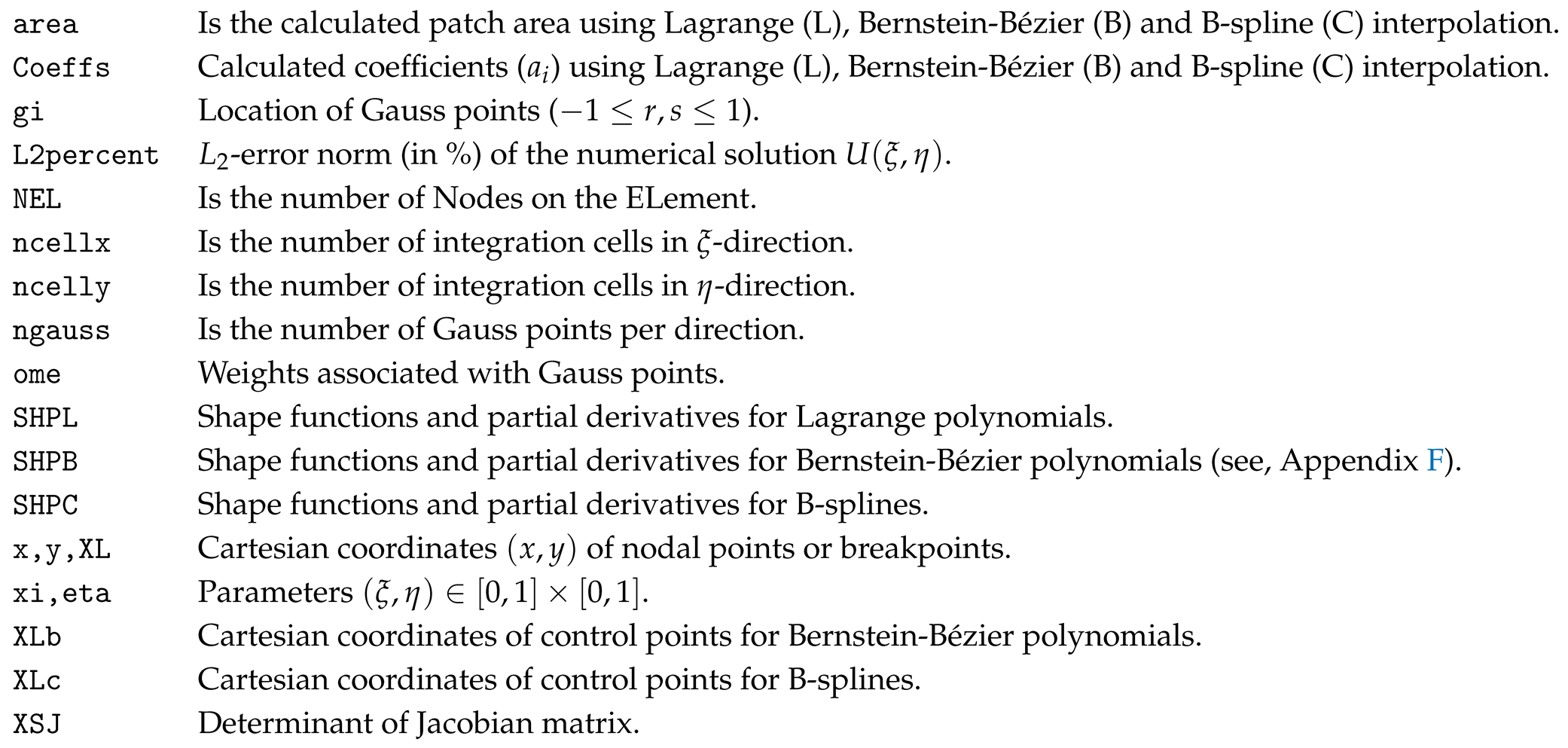

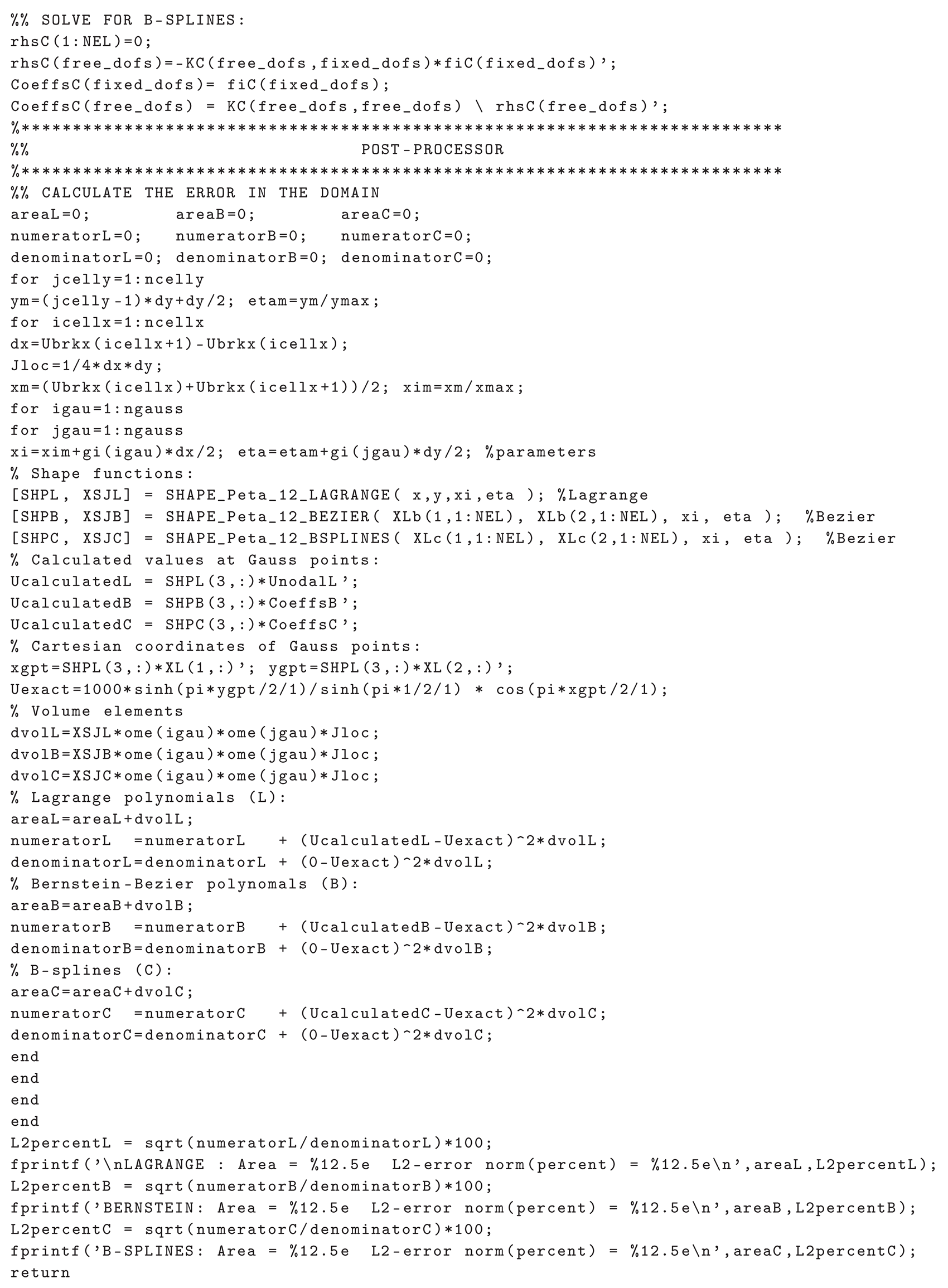

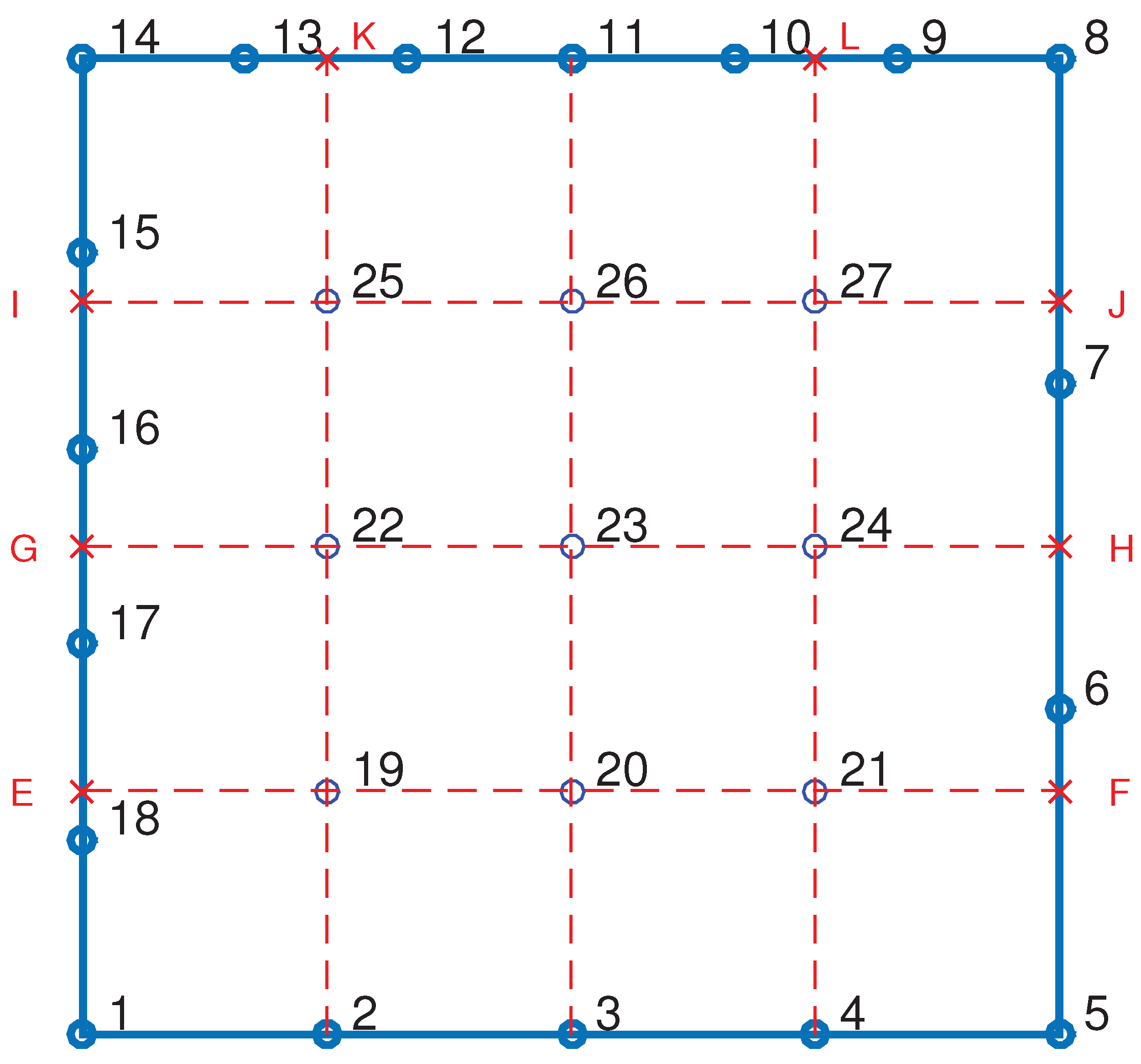

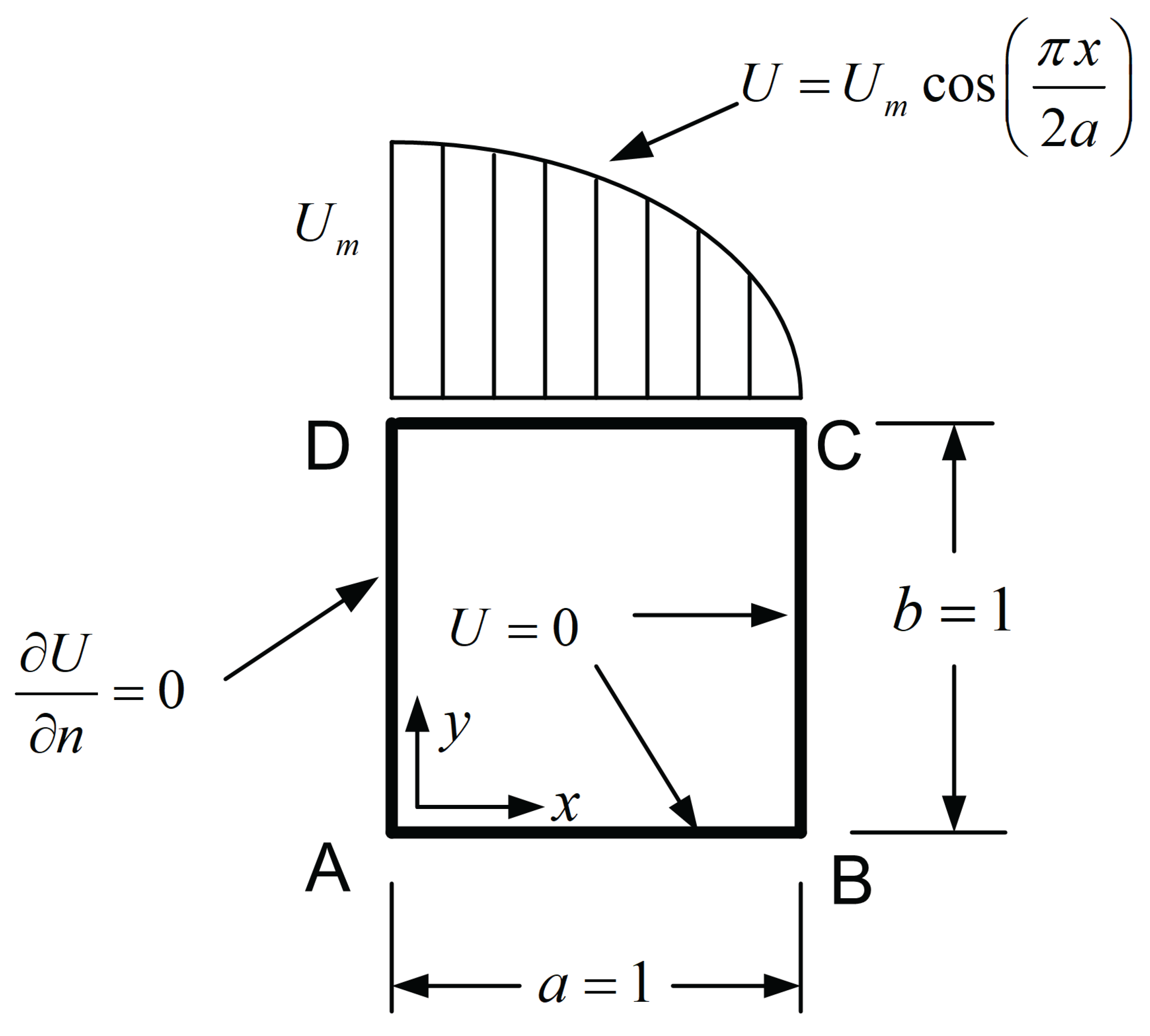

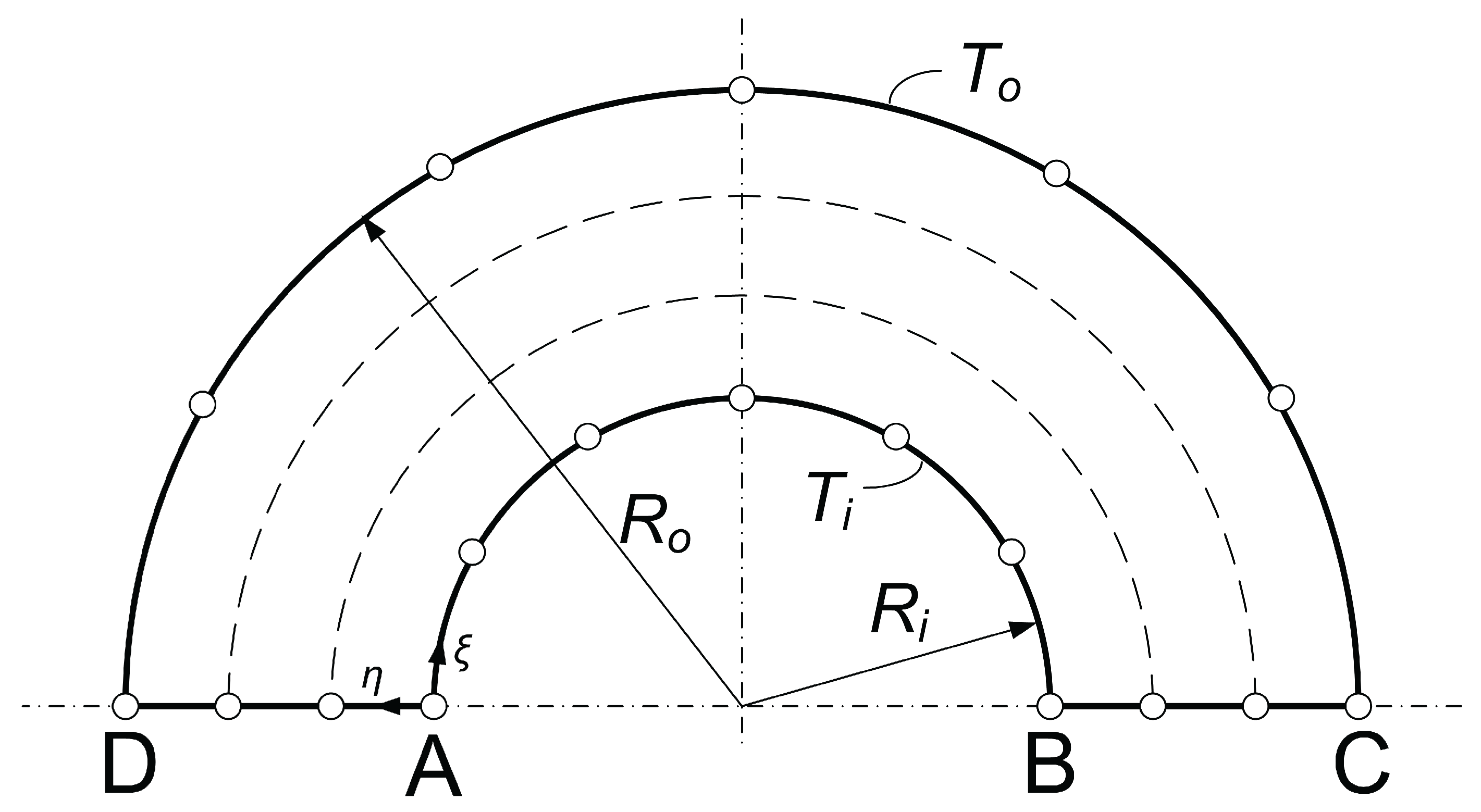

The parameterization of the patch is illustrated in

Figure 19:

- Point A is the origin of the axis

- Arc defines the -axis

- Segment defines the -axis

- Edges and are subjected to Dirichlet boundary conditions

- Edges and are subjected to Neumann boundary conditions (), due to symmetry.

In the numerical setup, each circular arc is uniformly subdivided into six breakpoint spans (). The number of uniform breakpoint spans along the radial direction (e.g., edge ) is varied incrementally:

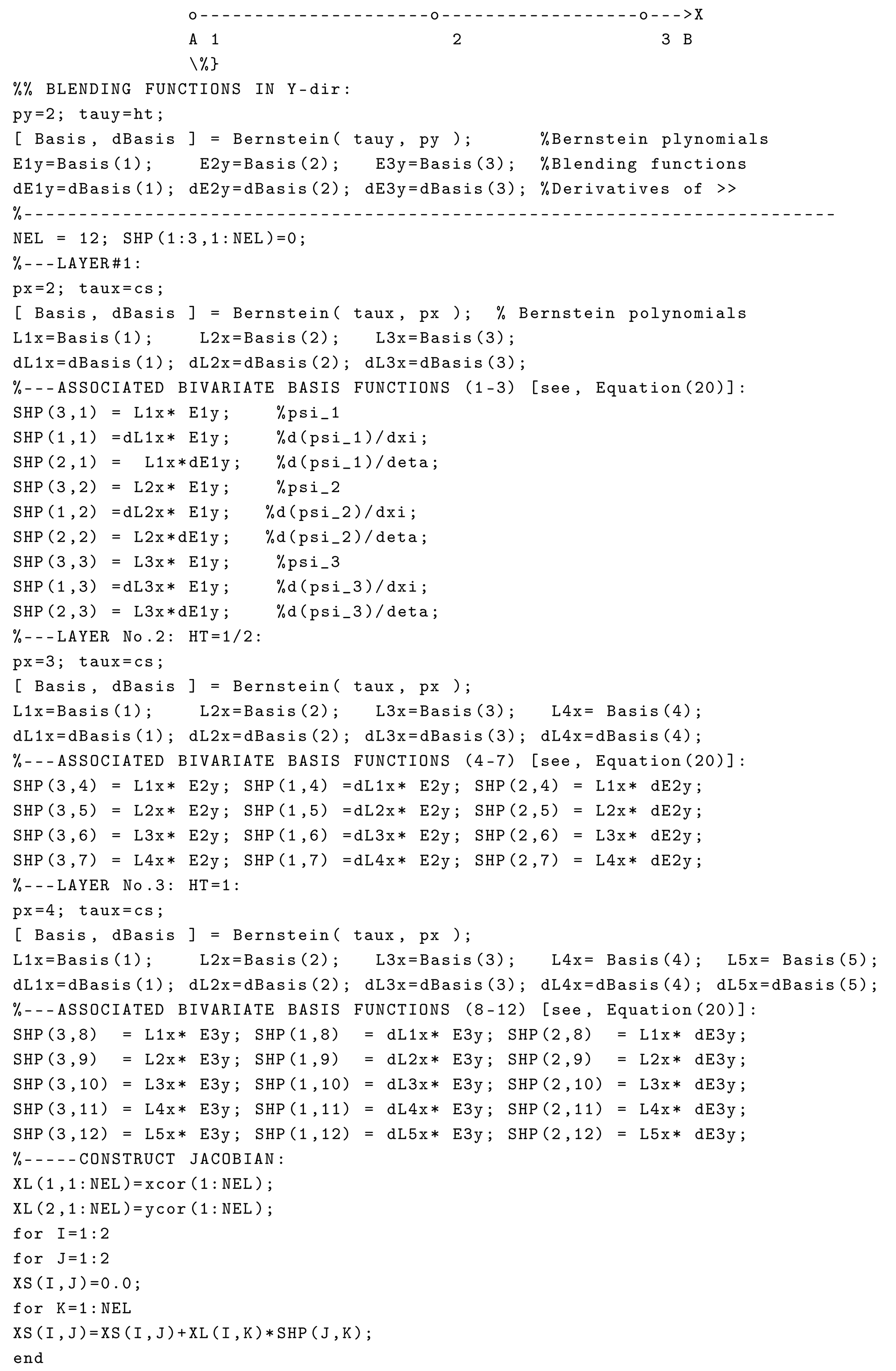

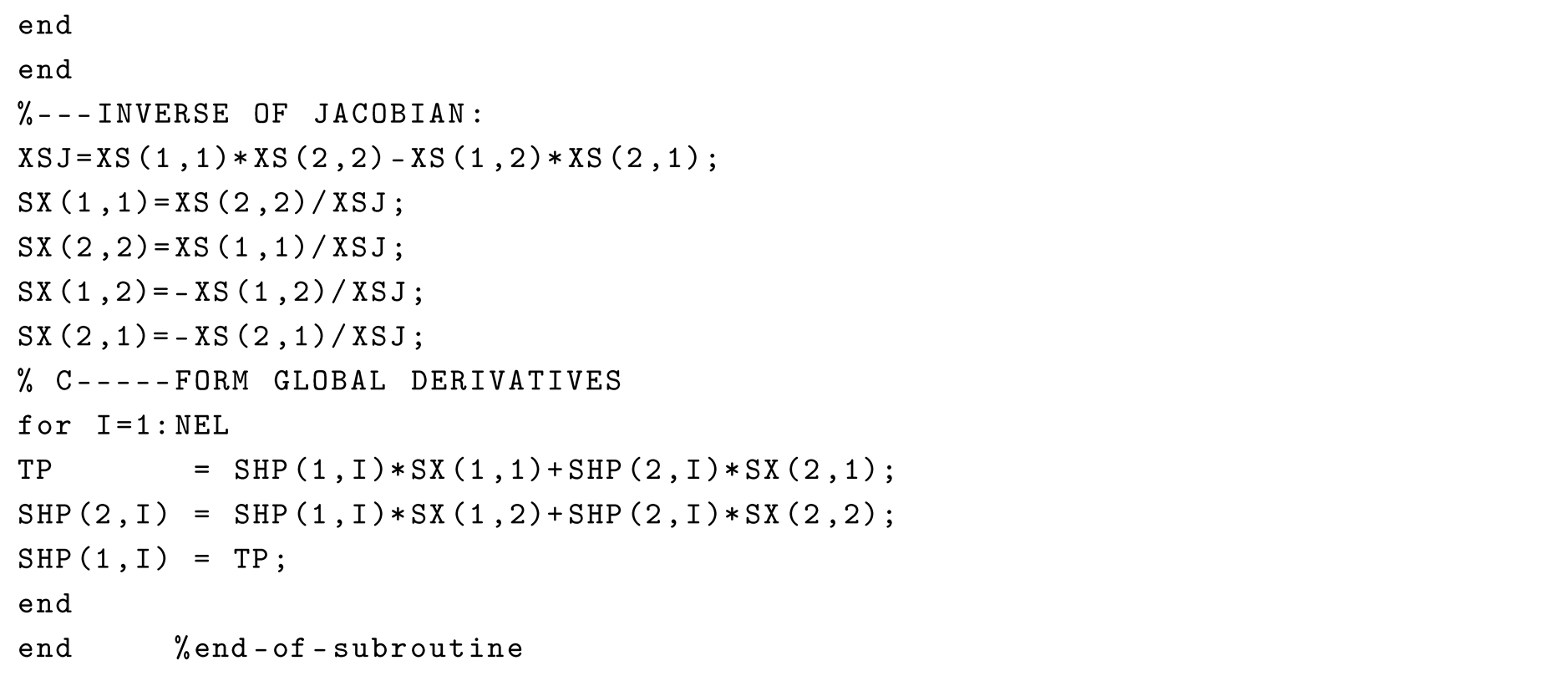

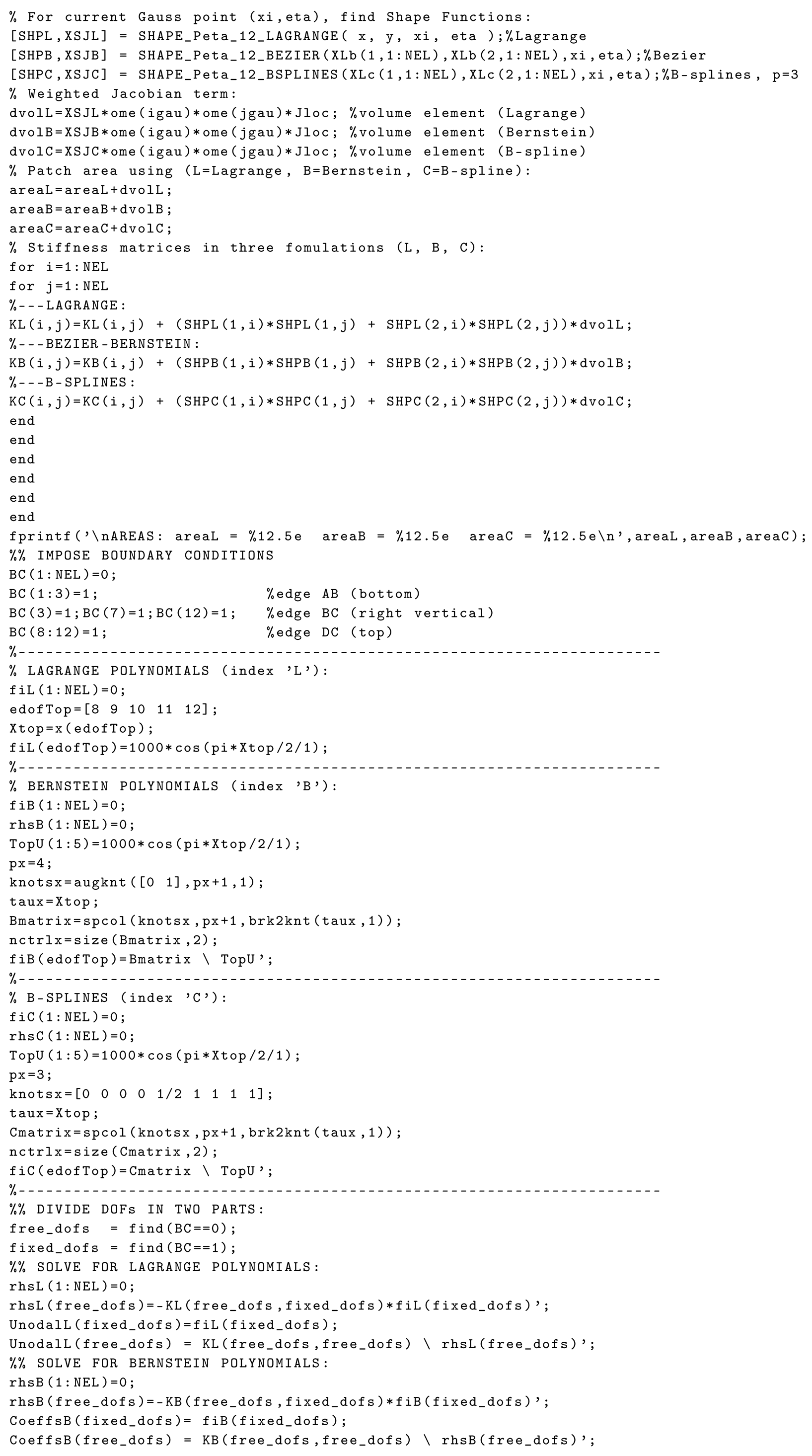

Model C1: Piecewise-Linear. The easiest case for implementing a Coons-patch macroelement is the adoption of

piecewise-linear trial functions. This implies minimal cost in the estimation of these functions and also ensures local support. The vector of unknowns includes

nodal values,

, all of them located on the boundary of the patch. Although this model is generally

not equivalent to a set of

bilinear finite elements, the quality of the numerical solution is sometimes

similar. In the particular case of Example 2, in which the solution does not depend on the polar angle

(axisymmetric problem with no angular dependence), the numerical solution of the Coons-patch element with piecewise-linear trial functions

coincides with that of the FEM solution using bilinear 4-node elements—provided the same mesh density is used. The result is shown in

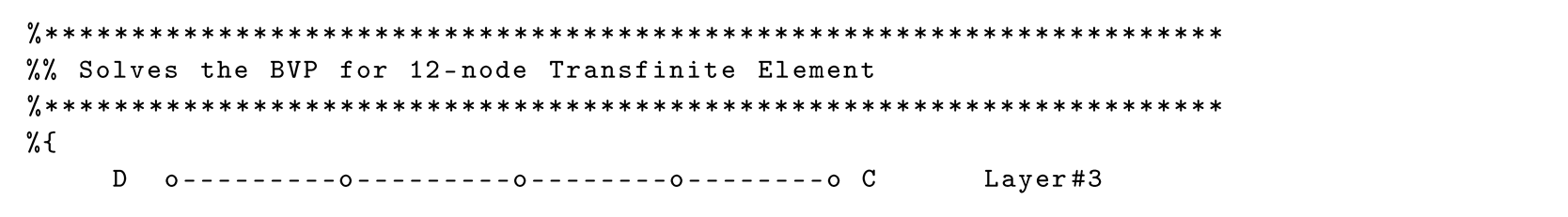

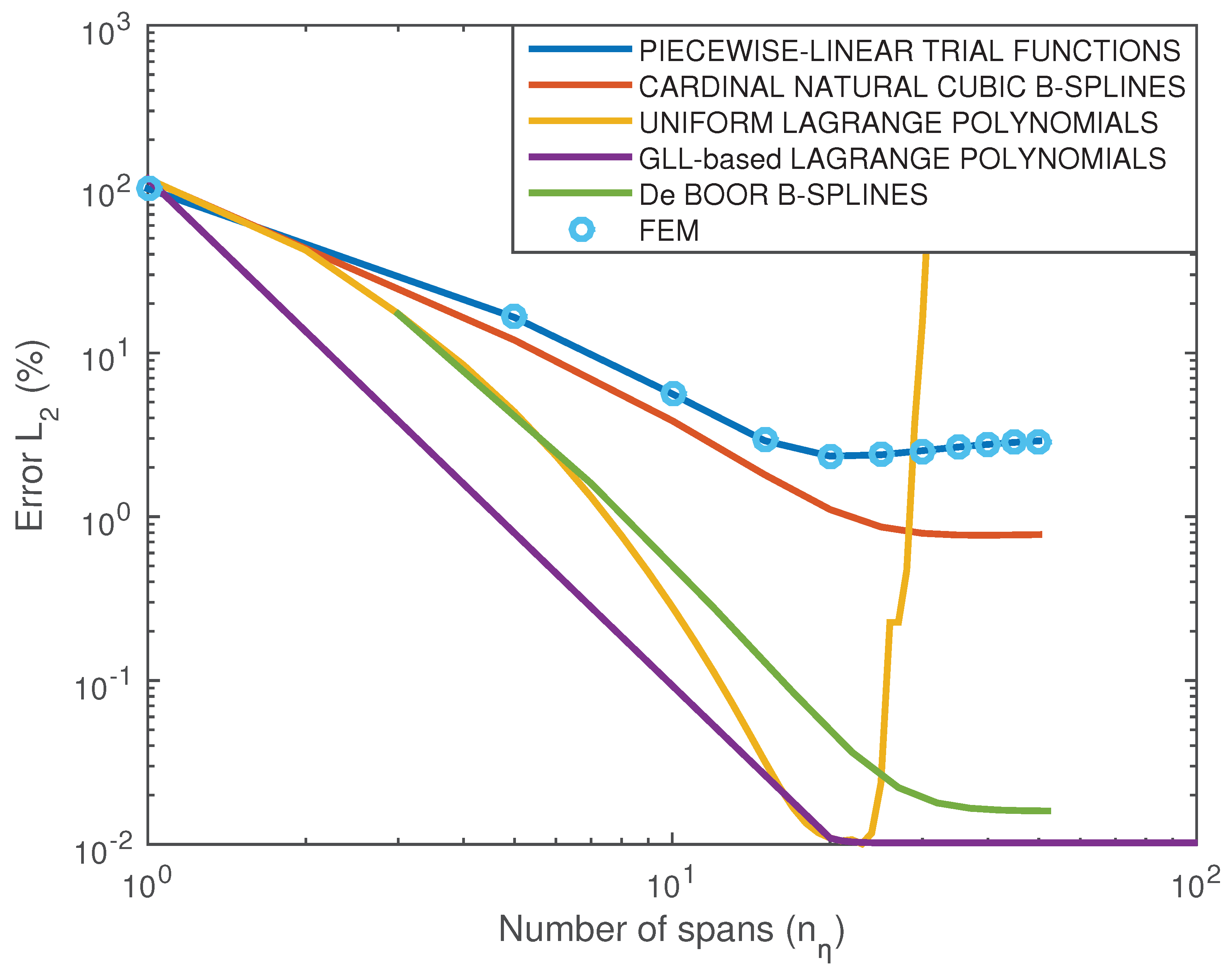

Figure 20 (blue line).

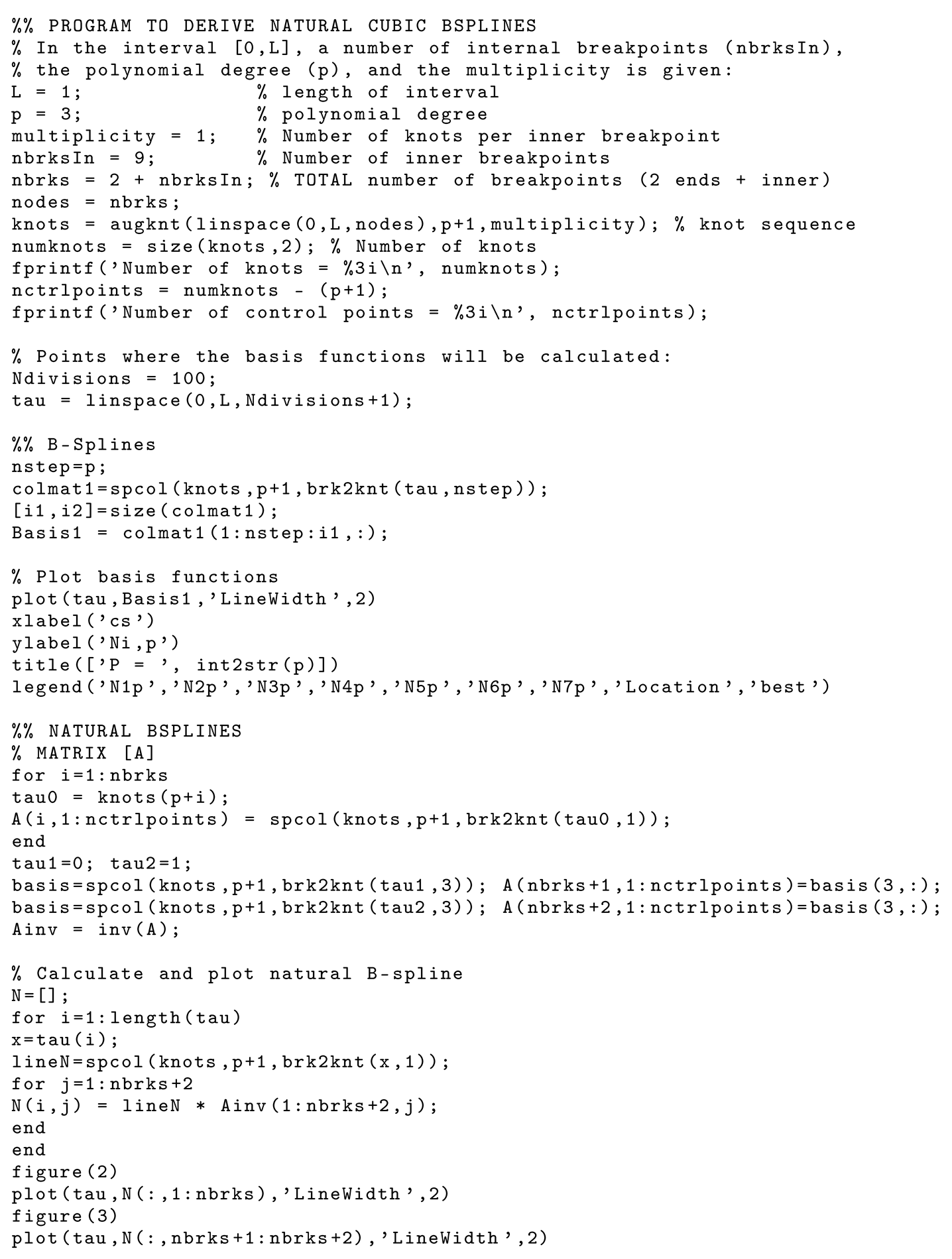

Model C2: Cardinal Natural Cubic B-Spline. This model briefly reproduces part of Ref. [

2], in which

cardinal natural cubic B-splines were previously used. Before the imposition of boundary conditions (BCs), the number of nodes is

. Since the

nodal points on edges

and

are restricted under Dirichlet-type BCs, the number of free degrees of freedom becomes

. The vector of unknowns includes only

nodal values,

, which was the primary reason for adopting this model in the mid-1980s. Numerical integration is performed within the

cells created by nodal breakpoints in both directions. Given the piecewise polynomial degrees

, the number of Gauss points per integration cell is

for curvilinear patches (and

for rectangular ones). The results, shown in

Figure 20 (red line), are identical whether the old-fashioned methodology of Ref. [

2] (based on truncated powers) or the procedure of

Appendix A is used—namely, the Curry-Schoenberg formulation [

29], computed via the Cox-de Boor algorithm [

30,

31], with vanishing second derivatives at the ends of each edge.

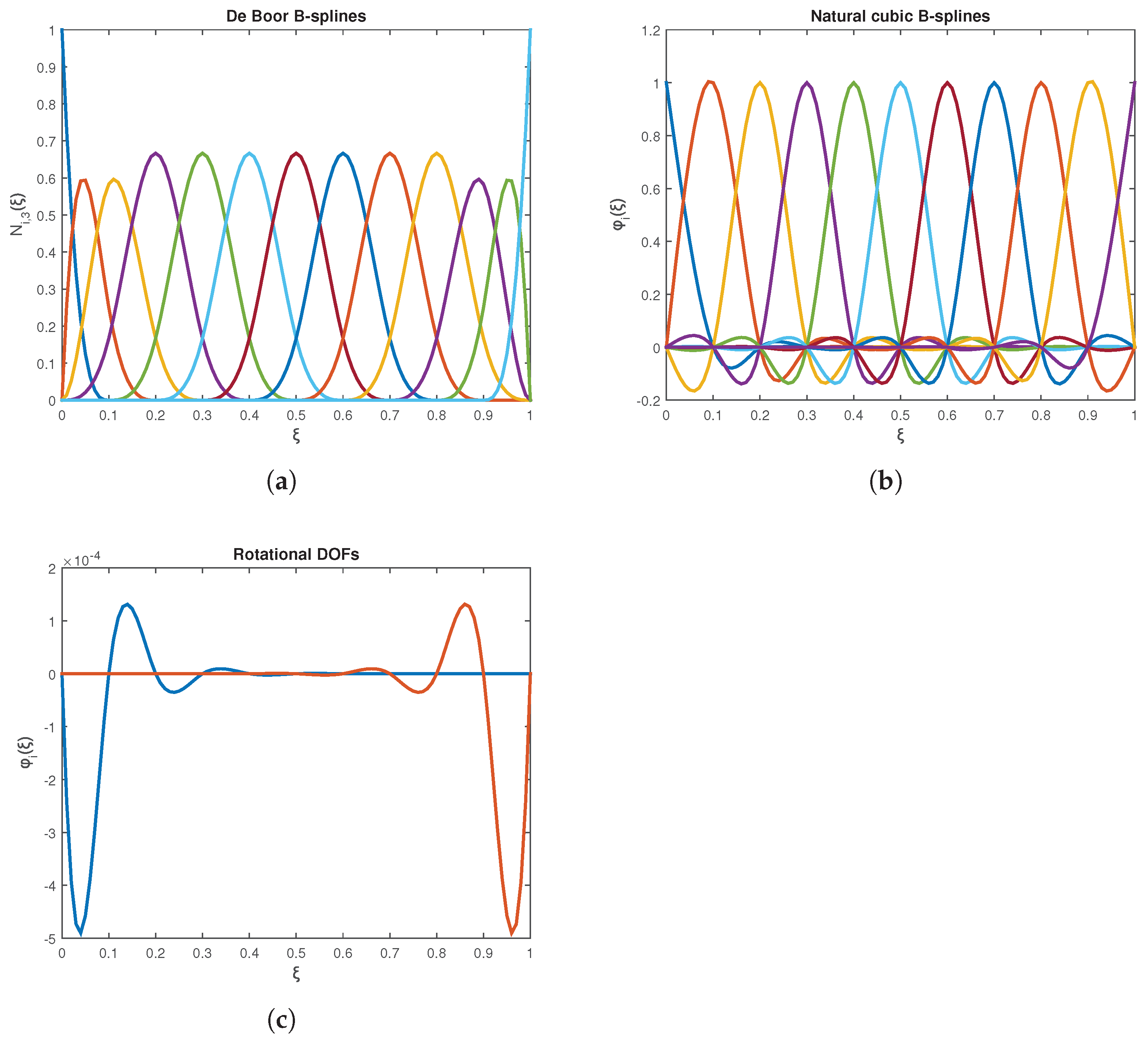

Model C3: Truncated Power Series. This model extends the previous Model C2 on the same single Coons-patch element, but now additionally incorporates rotational degrees of freedom (DOFs) associated with the second derivatives at the ends of each edge—as illustrated, for example, in

Figure A1c. In this case, although an edge such as

is discretized into

breakpoint spans (yielding

breakpoints), the number of associated control points along that edge becomes

. Consequently, after imposing Dirichlet boundary conditions, the final number of free DOFs becomes

. In this quantity, eight additional ’rotational’ DOFs are considered, though four of them—those along edges

and

under Dirichlet BCs—are eliminated. The vector of unknowns includes both nodal values,

, and the four curvatures

at the ends of edges

and

. The layout and number of integration cells remain the same as in Model C2, defined by the breakpoints. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 20 (green line).

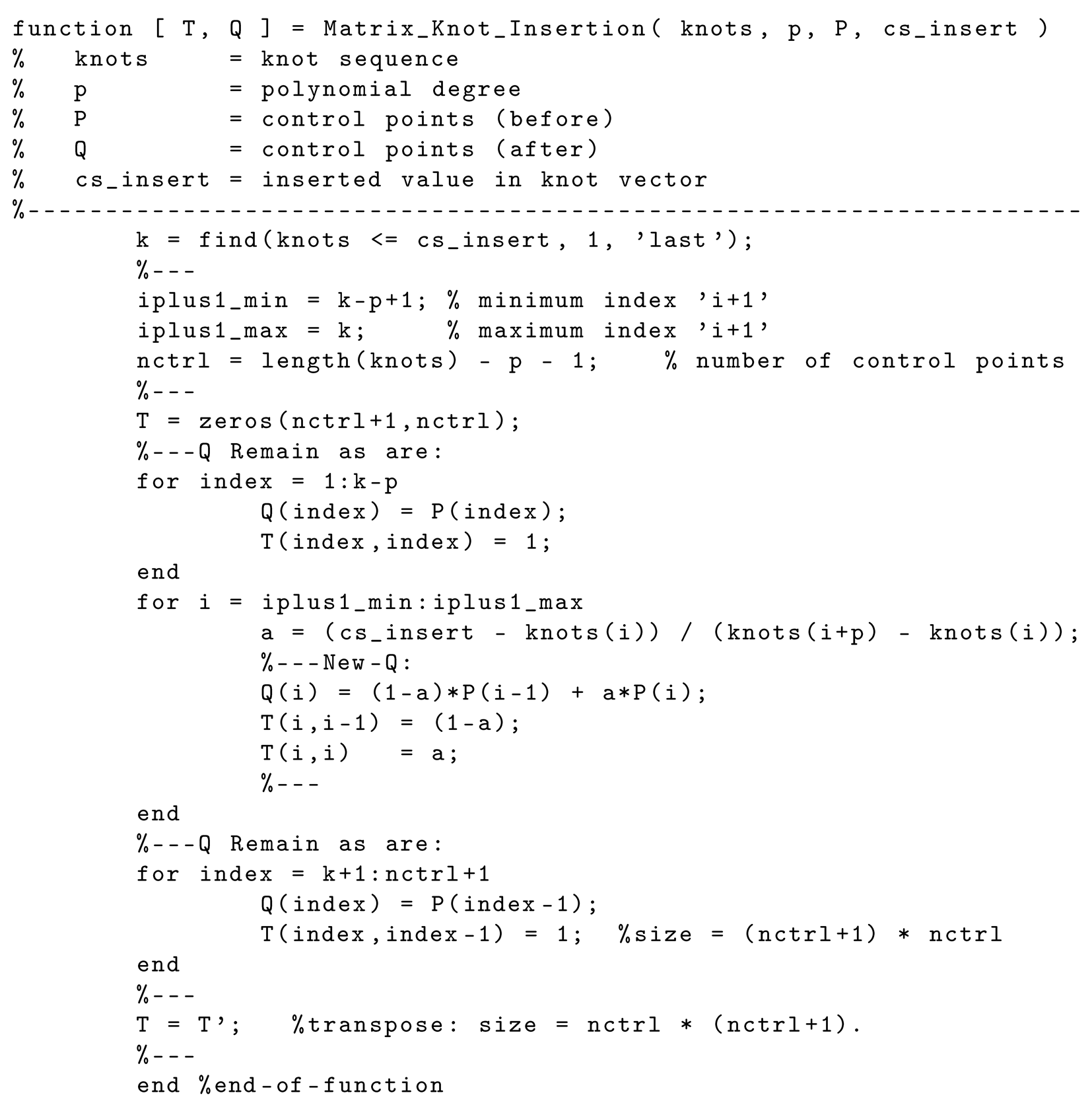

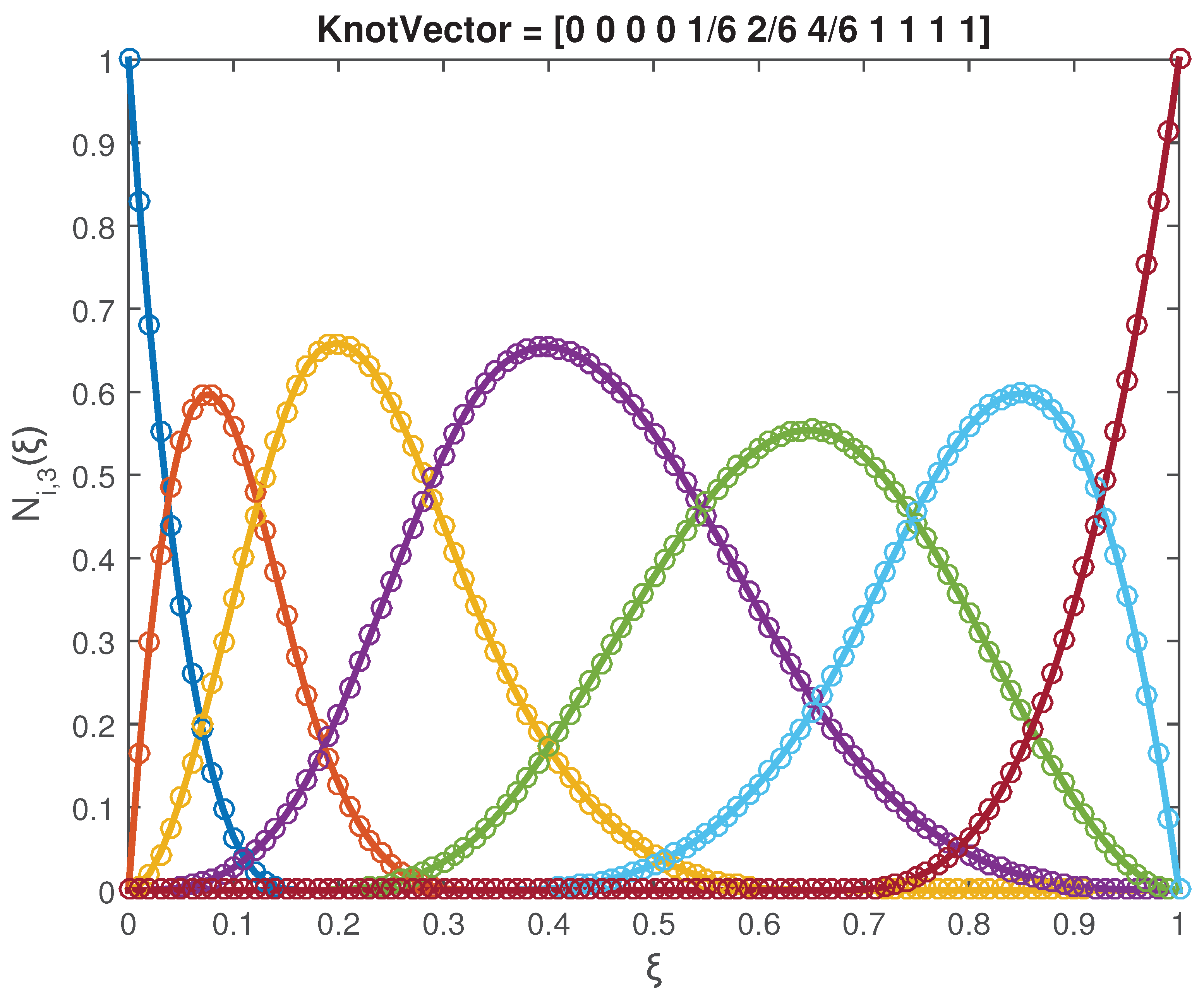

Model C4: Cox–de Boor B-spline. This model continues to use the same Coons-patch element. Let

be the parameters associated with the breakpoints along edge

. For a piecewise-cubic polynomial, we construct the well-known

knot vector, which defines

basis functions:

, where

is the number of breaks along the edge, following the notation of

Appendix A. The number of DOFs, both before and after applying boundary conditions, is the same as in Model C3, but here they consist of generalized coefficients

rather than nodal values. The integration cells are also the same, now with the additional property of

local support. Despite this difference, the results are

identical. In other words, although Model C3 lacks compact support (and deals with DOFs:

and

) while Model C4 possesses it (and deals with DOFs:

), the two functional sets are

equivalent, as confirmed by spline theory and also sustained by numerous test cases. It should be noted that most literature discussing Coons patches in conjunction with B-splines and NURBS refers to the present Model C4, as it is based on the modern spline formulation introduced by Curry and Schoenberg (1966) [

29] and implemented via the recursive Cox–de Boor algorithm (1972) [

30,

31]. Note that, since the

linear blending functions used in Coons interpolation are identical across all formulations (Lagrange, Bernstein, and B-splines), the B-spline version of the Coons element follows directly.

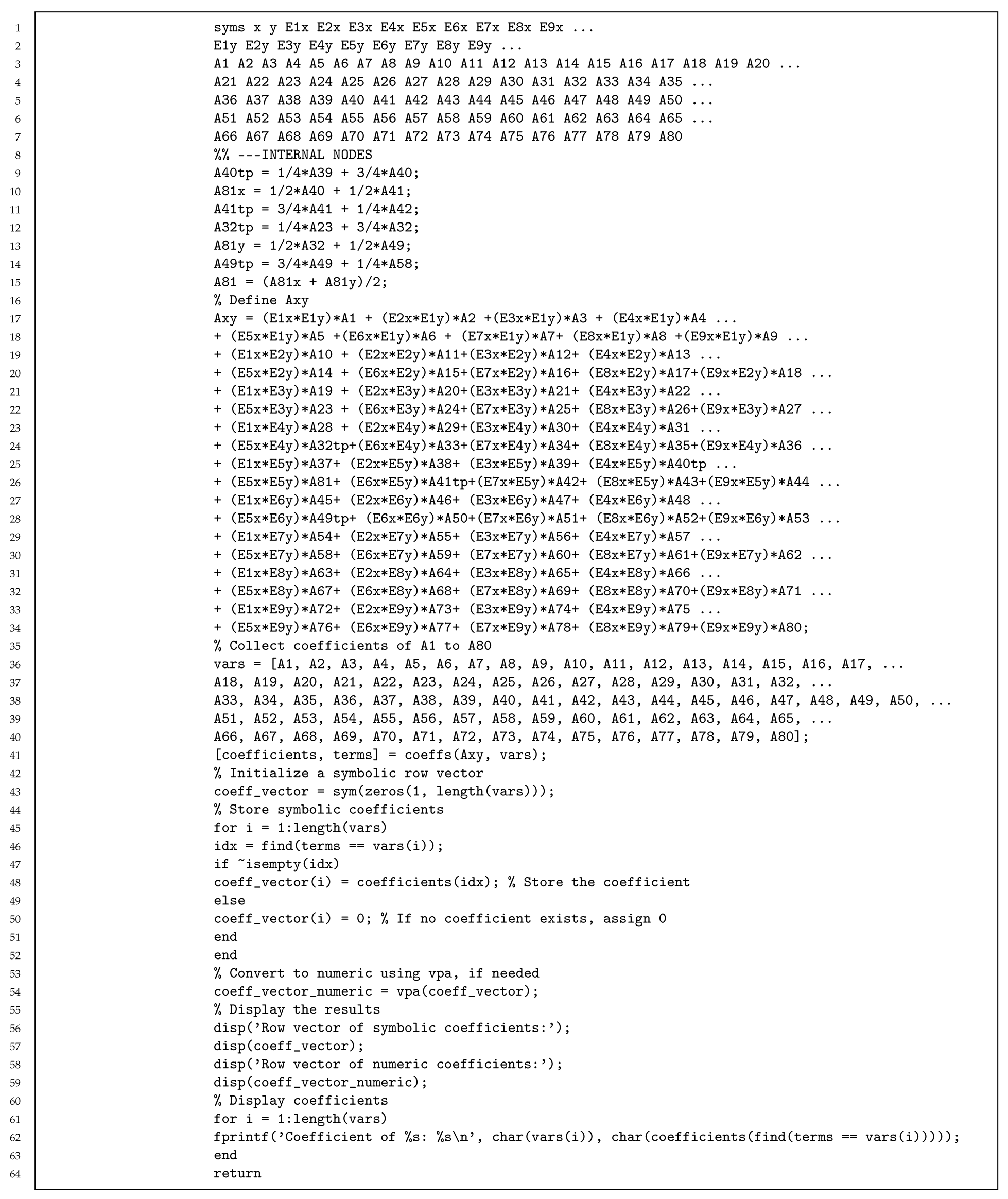

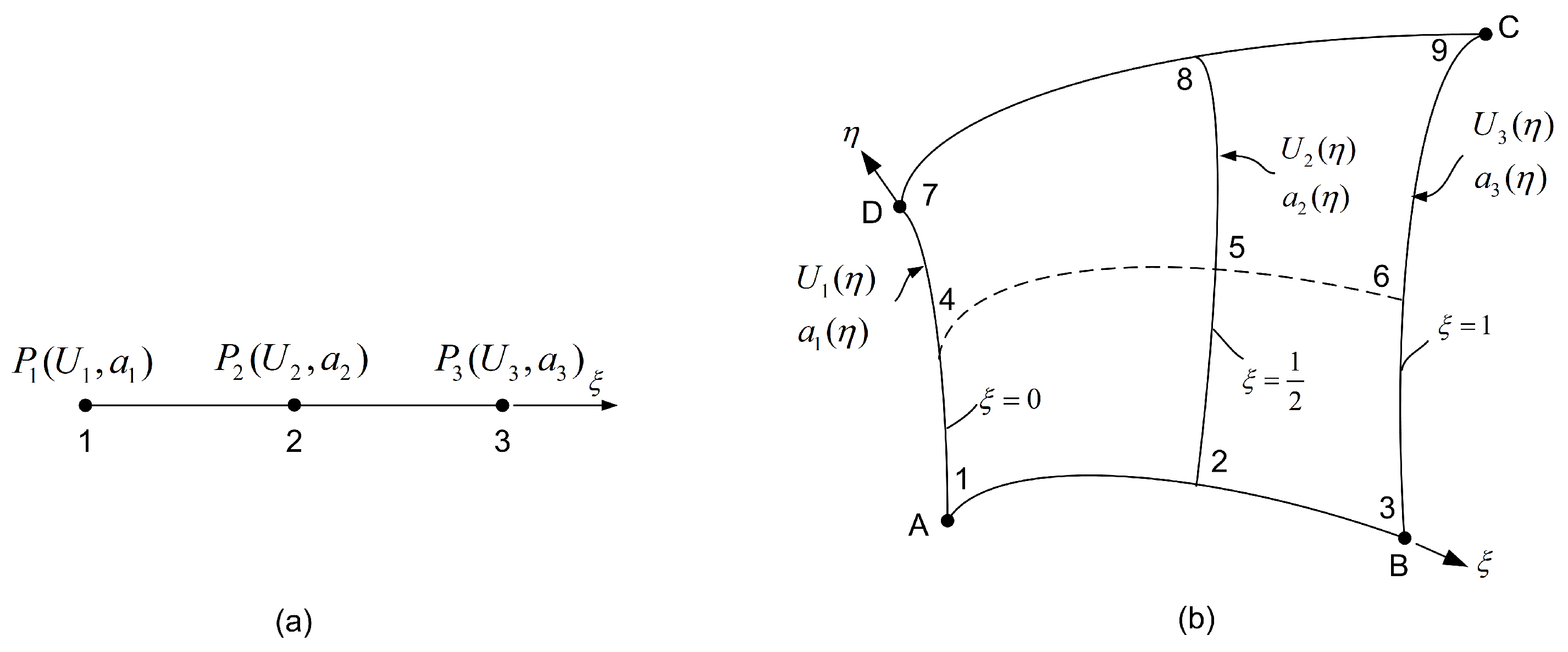

Model C5: Uniform Lagrange polynomials. This model continues with Coons elements, using

uniform global Lagrange polynomials as trial functions along each entire edge. Each bivariate function

is continuous, influences the entire quadrilateral patch, and is associated with the nodal value

. Let

p and

q denote the polynomial degrees in the

- and

-directions, respectively. It can be readily verified that the integrand of each entry in the stiffness matrix,

, is of degree

per direction—specifically,

from

and

from

. Consequently, for a rectangular patch

, the stiffness matrix and error norm are estimated using a global scheme of

Gauss points, whereas curvilinear patches such as that in

Figure 19 require

Gauss points spanning the entire patch. Due to this, the terms “patch” and “Coons element” are used interchangeably. Closely related terminology such as “macroelement” or “Coons-patch element” has also appeared in previous literature [

9]. From the convergence diagram in

Figure 20 (orange color), it becomes evident that increasing the polynomial degree

p in the

-direction steadily improves numerical accuracy up to

, beyond which the solution becomes unstable.

Model C6: Non-uniform Lagrange polynomials. The sixth model studies Coons elements, using

non-uniform global Lagrange polynomials as trial functions along each entire edge. Following the practice of spectral methods by Karniadakis and Sherwin [

32], one of the best choices is the set of

Gauß–Lobatto–Legendre (GLL) points, which are defined as follows:

where

denotes the roots of the Lobatto polynomial

of order

, which is defined as the first derivative of the Legendre polynomial

of order

p:

Practically, for any given degree

p, the

GLL points

, defined in Equation (

49), can be numerically determined by setting

i = p - 1 in the following MATLAB command:

roots = vpasolve((legendreP(i,x) - legendreP(i+2,x)) == 0);

Based on the above nodal points (images of the GLL points), we can easily construct non-uniform Lagrange polynomials and use them as trial functions for each edge of the quadrilateral patch .

In our case, we kept the uniform subdivision of the circular arcs at

, and adopted GLL-based nodal points along the edges

and

. The polynomial degree varied from

to

. It was found that, up to degree

, the results are practically the same in both formulations—i.e., the uniform and non-uniform (GLL-based). By further increasing the polynomial degree up to

, the non-uniform formulation yielded a monotonically decreasing error norm, converging to the value

(

Figure 19). This remaining error is attributed to the discretization of the circular arcs, which are based on seven nodal points per arc (i.e., six uniform nodal spans:

).

Remark: Let us divide the interval

into

n segments (i.e.,

nodal points) in the

-direction. Regarding global interpolation, one possibility is to introduce

Lagrange polynomials

of degree

, which leads to integrands in the stiffness and mass matrix entries

of degree

; therefore, the required number of Gauss points for the whole interval is

.

On the other hand, cubic B-spline interpolation over the aforementioned n elements leads to matrix element integrands of degree six, and thus requires four Gauss points per element; this results in a total of Gauss points.

Of course, the stiffness and mass matrices in the Lagrange formulation will be of size , whereas in the B-spline formulation they will be of size (because breakpoints give control points). In any case, the B-spline formulation requires more Gauss points than the Lagrange formulation.

Model C7: Finite Element Method (FEM). Based on the pair , the FEM model using bilinear 4-node elements consists of nodal points. In the general case in which the solution does not follow the Coons interpolation (like Example-1), the model of piecewise-linear Coons-patch element—with nodes—differs from the FEM solution. In other cases such as in Example-2, the piecewise-linear based Coons element is equivalent to the FEM model, and thus both models have the same numerical error .

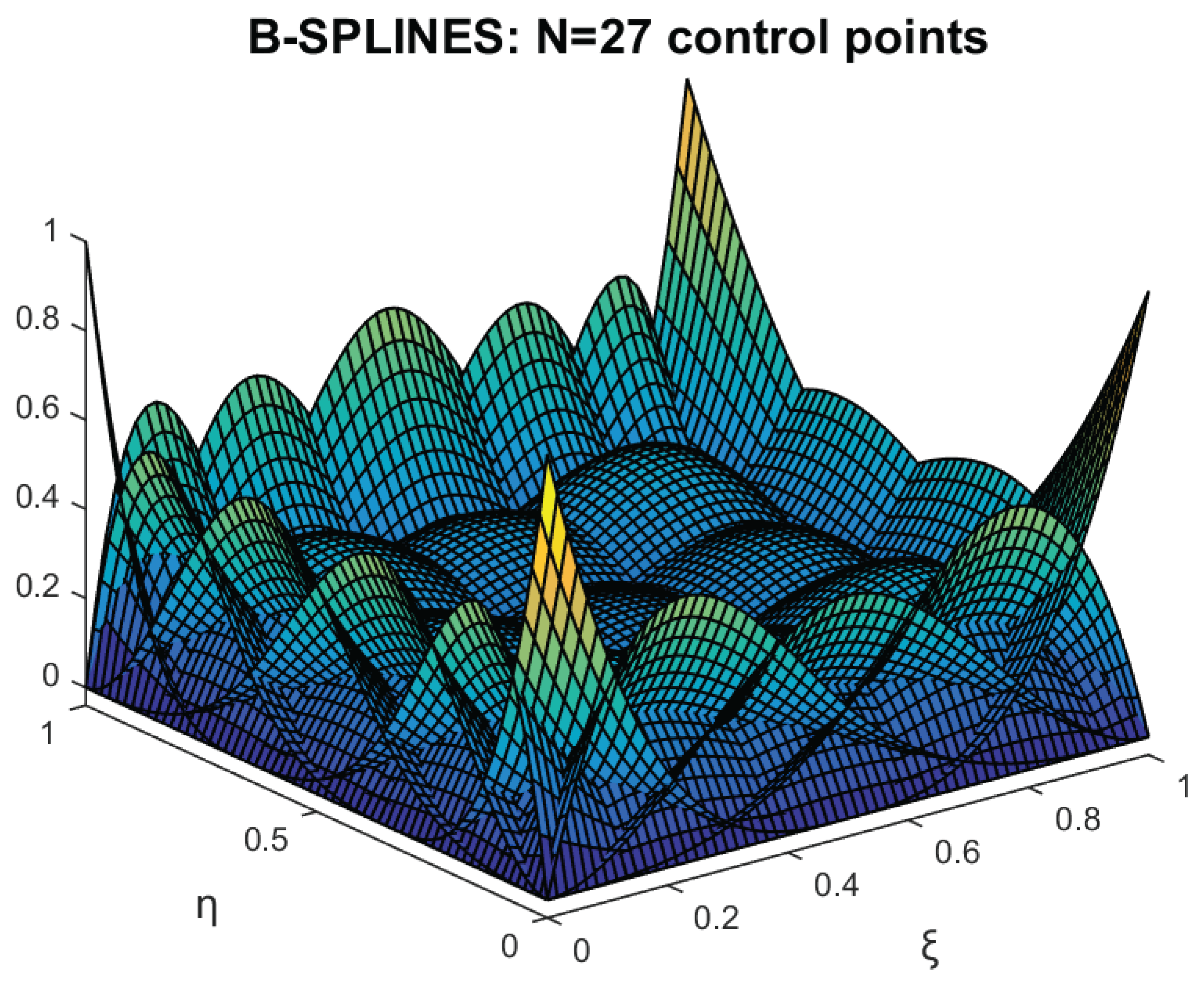

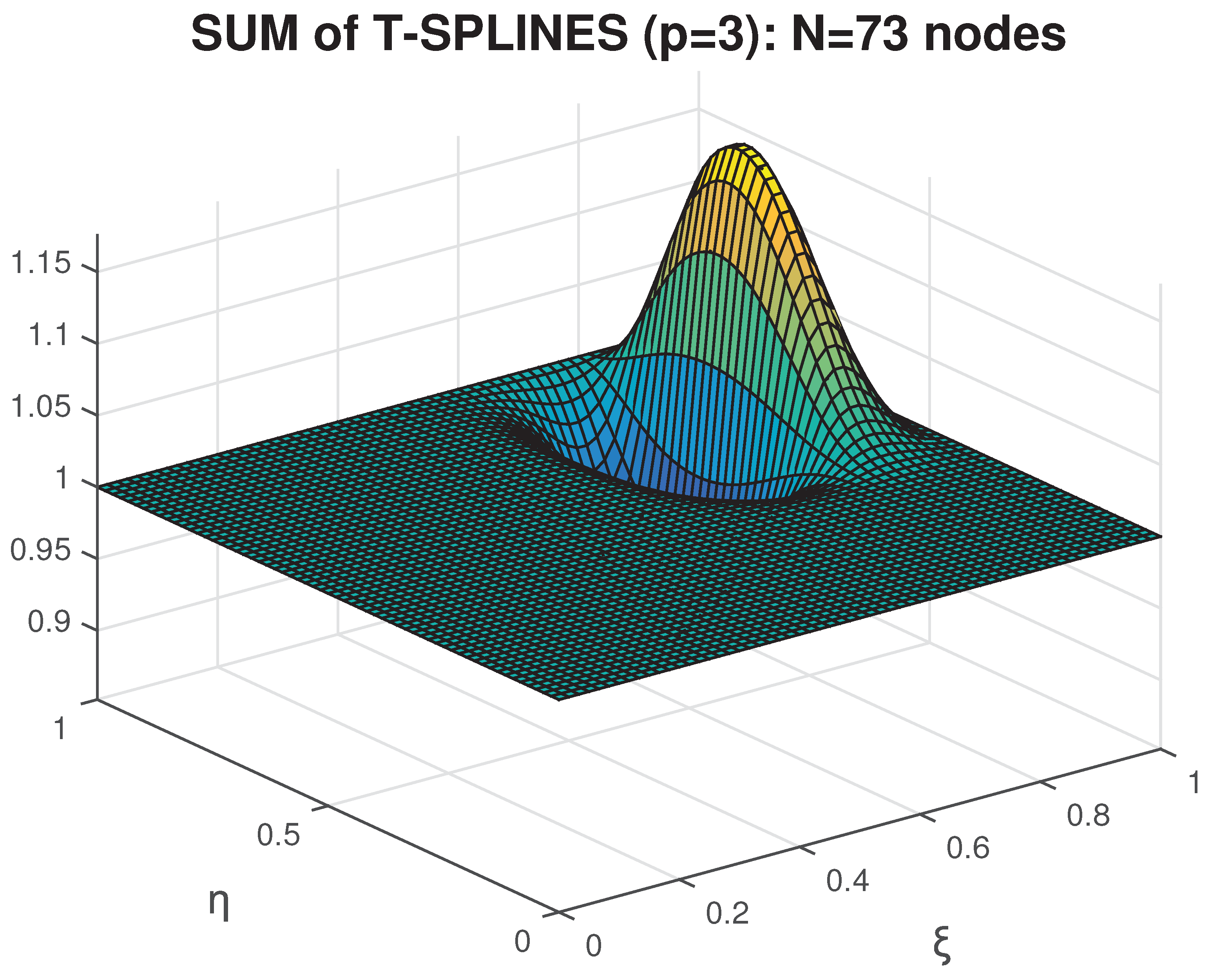

Overall, the results shown in

Figure 20 suggest:

- (1)

All models converge to different values. This fact is mainly due to the incapability of accurately representing the circular arc (for ). Below we start from the less accurate model and end with the most accurate.

- (2)

Piecewise-linear Coons interpolation coincides with the FEM solution. This is because Example-2 is an axisymmetric problem with no angular dependence.

- (3)

The cardinal natural cubic B-spline is characterized by a smaller error than the above piecewise-linear model and FEM.

- (4)

Uniform Lagrange polynomials lead to a smaller error but, after the value , diverge.

- (5)

De Boor cubic B-splines closely follow the accuracy of uniform Lagrange polynomials up to , then become less accurate until , and eventually converge to the value .

- (6)

The non-uniform Lagrange polynomials based on GLL points rapidly converge to the accurate solution. A small error () remains, due to the incapability of accurately representing the circular arc using spans.

In all the above models, it is anticipated that the error norm will be decreased when the circular arcs are represented through more nodal points or NURBS.

8.2.2. Transfinite Elements

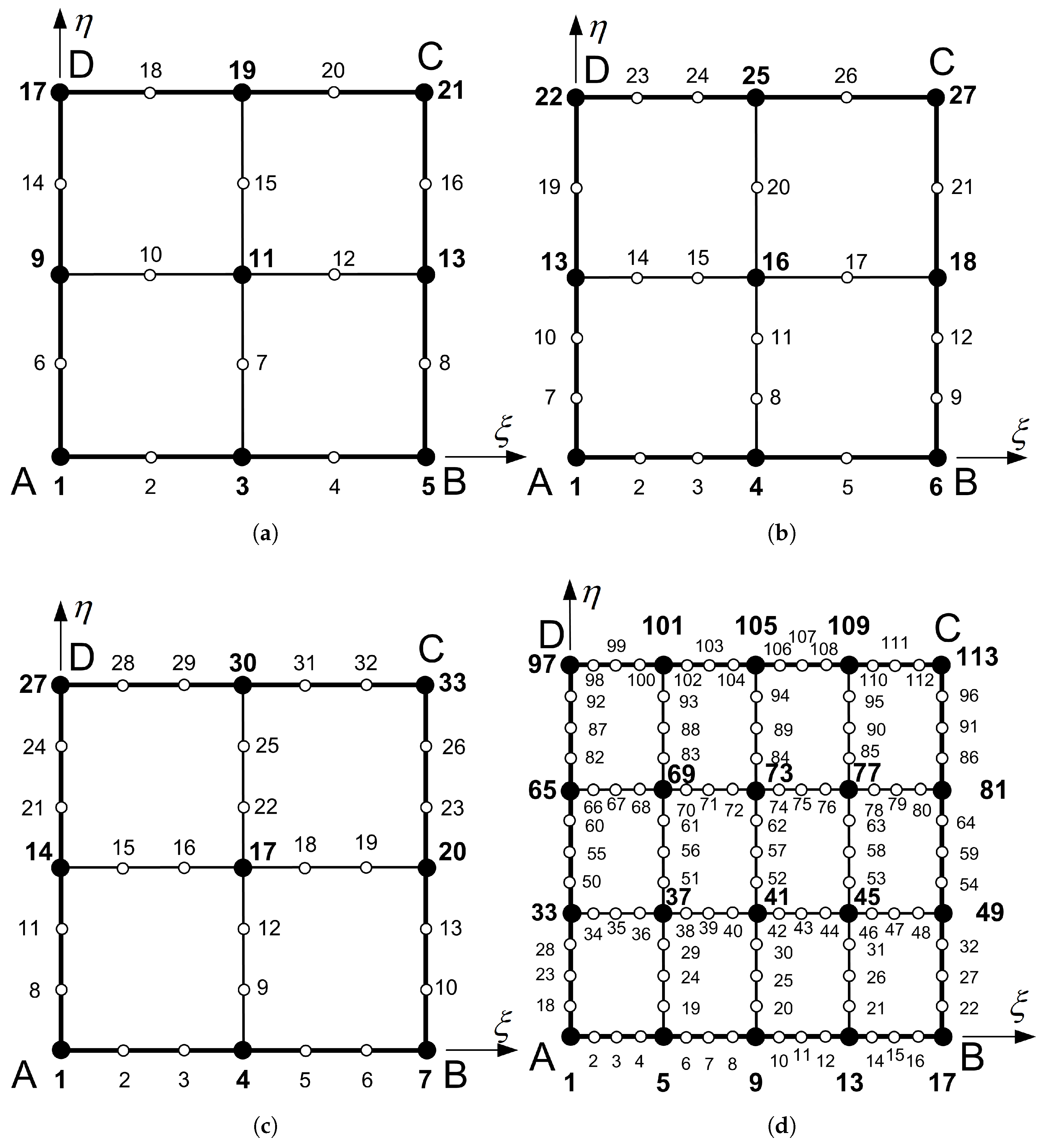

A. Classical Transfinite Elements

Each of the four classical transfinite elements shown in

Figure 3 is mapped onto the entire half-annulus depicted in

Figure 19. Given the parametric coordinates

and

of the nodal points, the corresponding polar coordinates

r and

in the physical domain are obtained as:

The numerical results are reported in

Table 7, where convergence behavior can be observed. As in Example 1, the same result was obtained when using Bernstein polynomials.

Moreover, it is instructive to compare the above results with those obtained for the previously mentioned Model C5 (uniform Lagrange or Bernstein polynomials for a single Coons element) under similar conditions, i.e., with subdivisions along the radial direction.

From

Figure 20 (orange curve), the corresponding errors are 8.5851%, 4.3559%, 2.3578%, and 0.1127%, respectively.

It is evident that, in Example 2, the aforementioned accuracy of the Coons model is very close to that of the classical transfinite elements (

Table 7), primarily due to the independence of the solution from the polar angle

.

To some extent, the small differences can be attributed to the different discretization of the semi-circular edges in the transfinite patch. It is likely that, if NURBS were employed, these differences would be further reduced.

The aforementioned similarity between classical transfinite elements and the Coons element is observed for all models discussed in

Section 8.2.1. For instance, both the 113-node transfinite element (with 56 DOFs on the boundary) and its counterpart Coons element (model C4, based on Cox–de Boor cubic B-splines with a total of 56 DOFs) yield the same error norm,

. This value is approximately 2.5 times larger than the error obtained when using Lagrange polynomials as trial functions (see

in

Table 7).

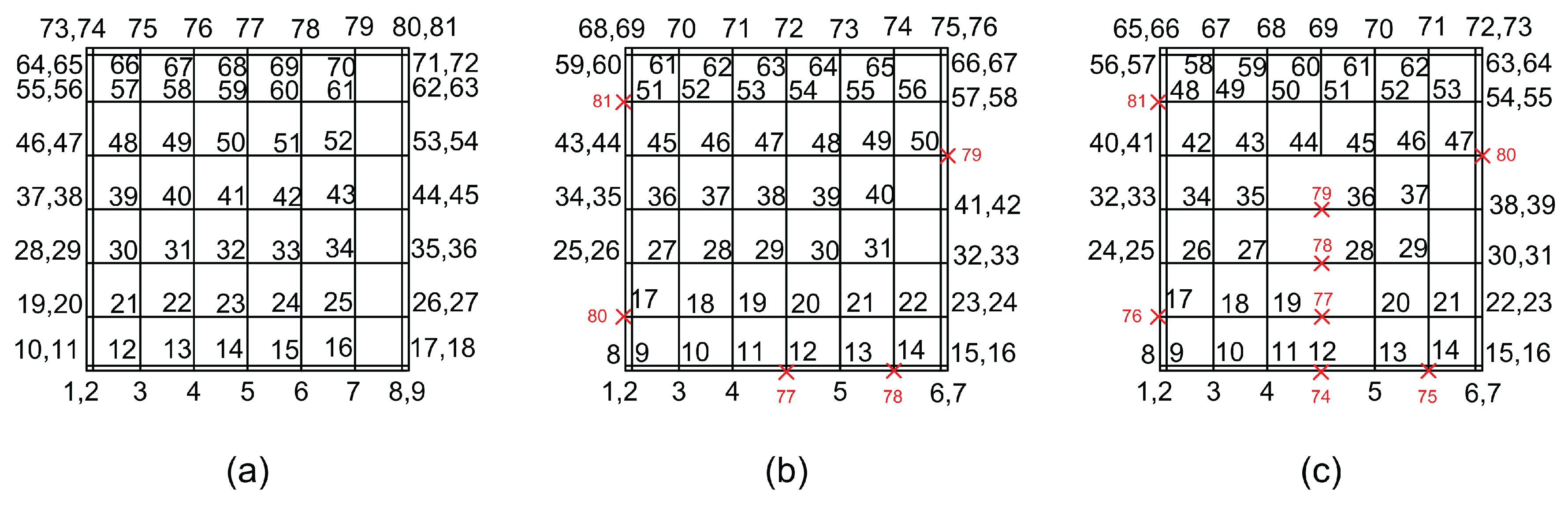

B. T-spline Elements

The half annulus shown in

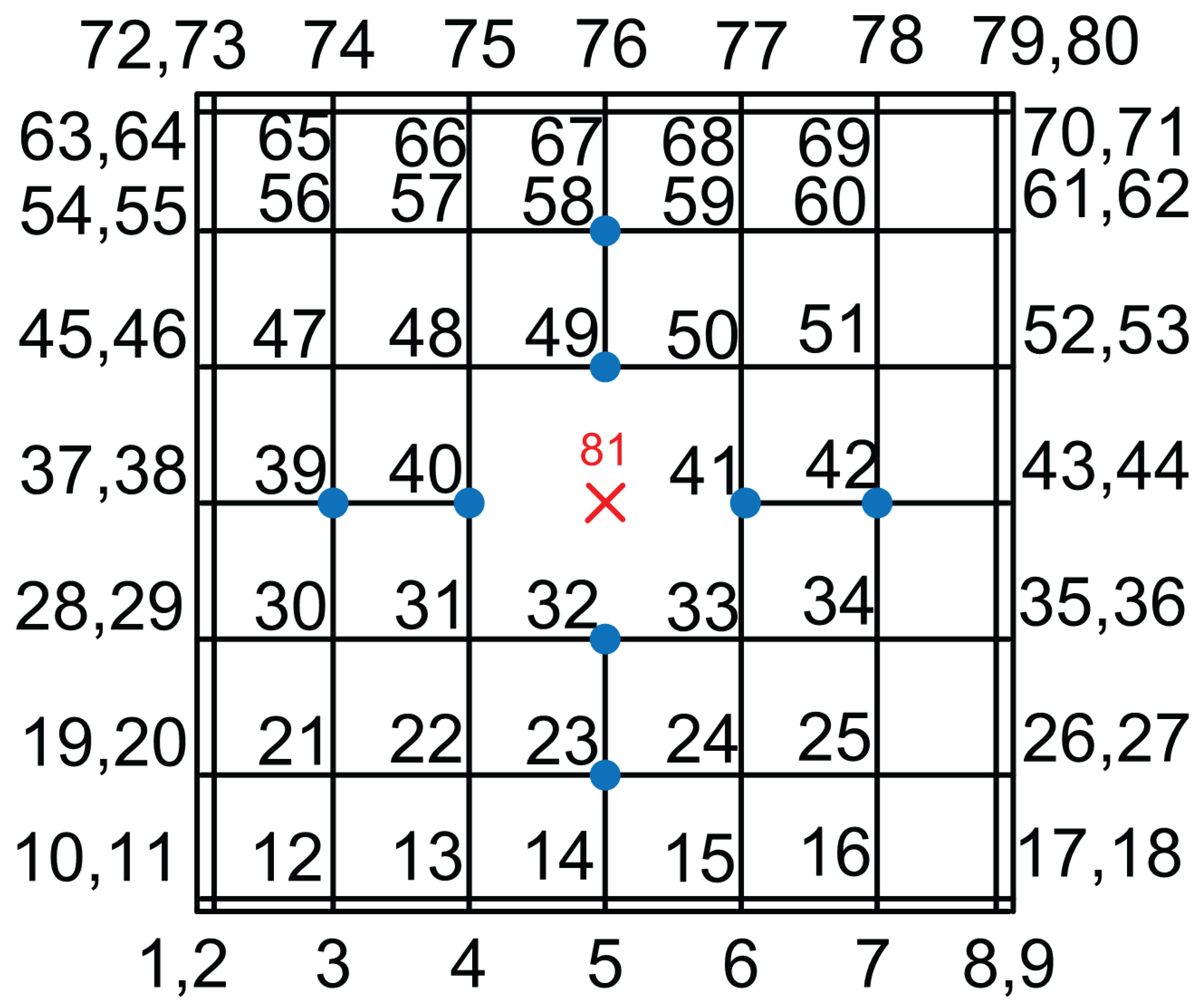

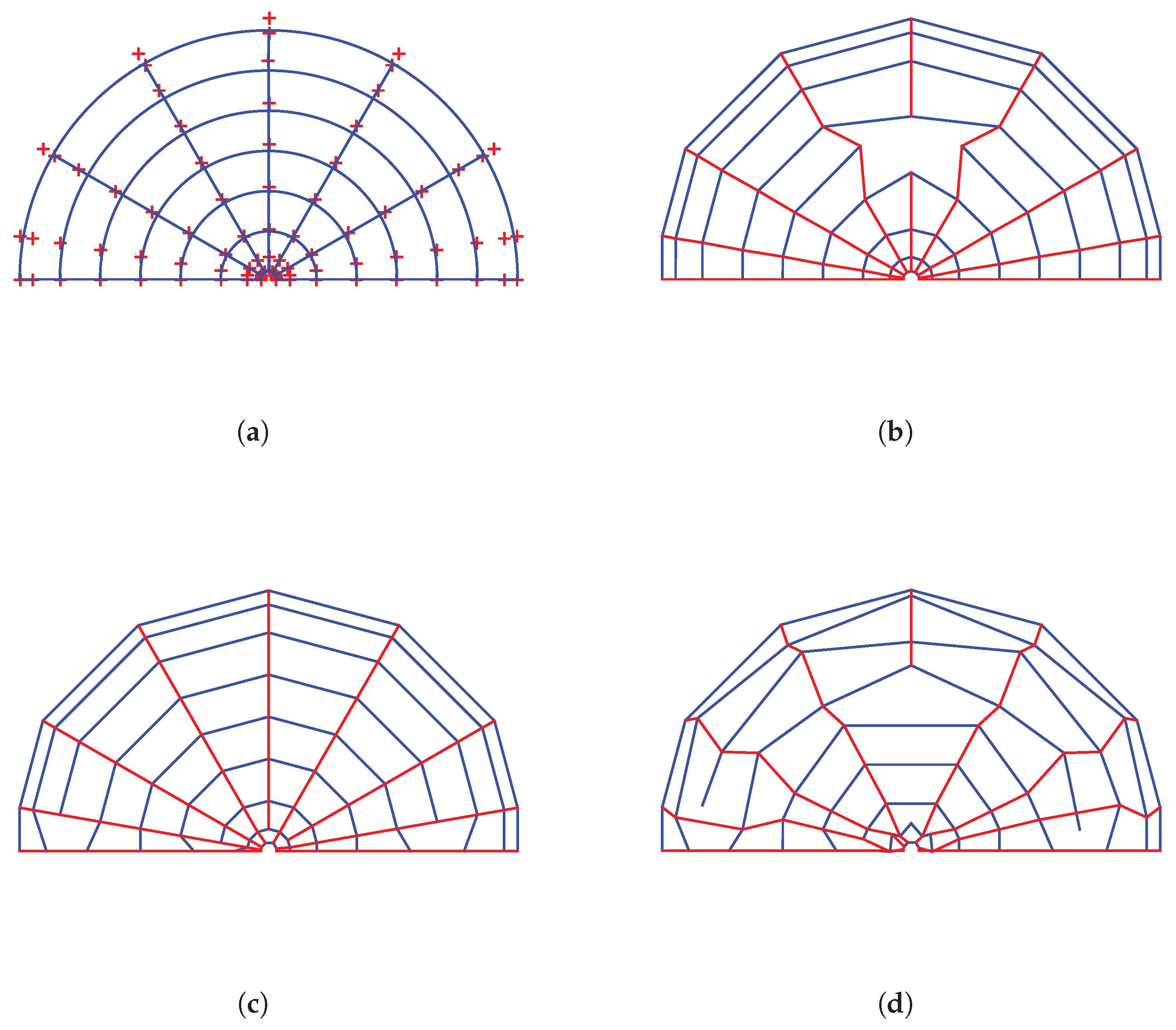

Figure 19 was discretized using a uniform tensor-product of

breakpoints, resulting in a grid of

control points (81 DOFs), as illustrated in

Figure 21a. More specifically, a tensor-product of Cox–de Boor cubic B-splines (

) was constructed using a uniform knot vector

The parametric space was uniformly divided into a grid of test points , for , and a corresponding uniform mesh of test points was generated in the physical domain.

The system of 81 equations for

:

determines the positions of the 81 control points

, illustrated by red crosses in

Figure 21a. In this way, the B-spline curve (with unit weights), corresponding to each circular arc, passes through nine uniformly distributed points along the arc. Consequently, a small deviation from the exact representation of the arc occurs between these points. Extending this formulation to NURBS is a straightforward task, but it is left to the interested reader.

It was found that the above B-spline tensor product yields the same numerical result, i.e.,

, as that obtained using the corresponding Coons-patch element with the same number of breakpoint spans (see

Section 8.2.1, Model C4). As previously mentioned, this outcome arises because the problem is axisymmetric and exhibits no angular dependence.

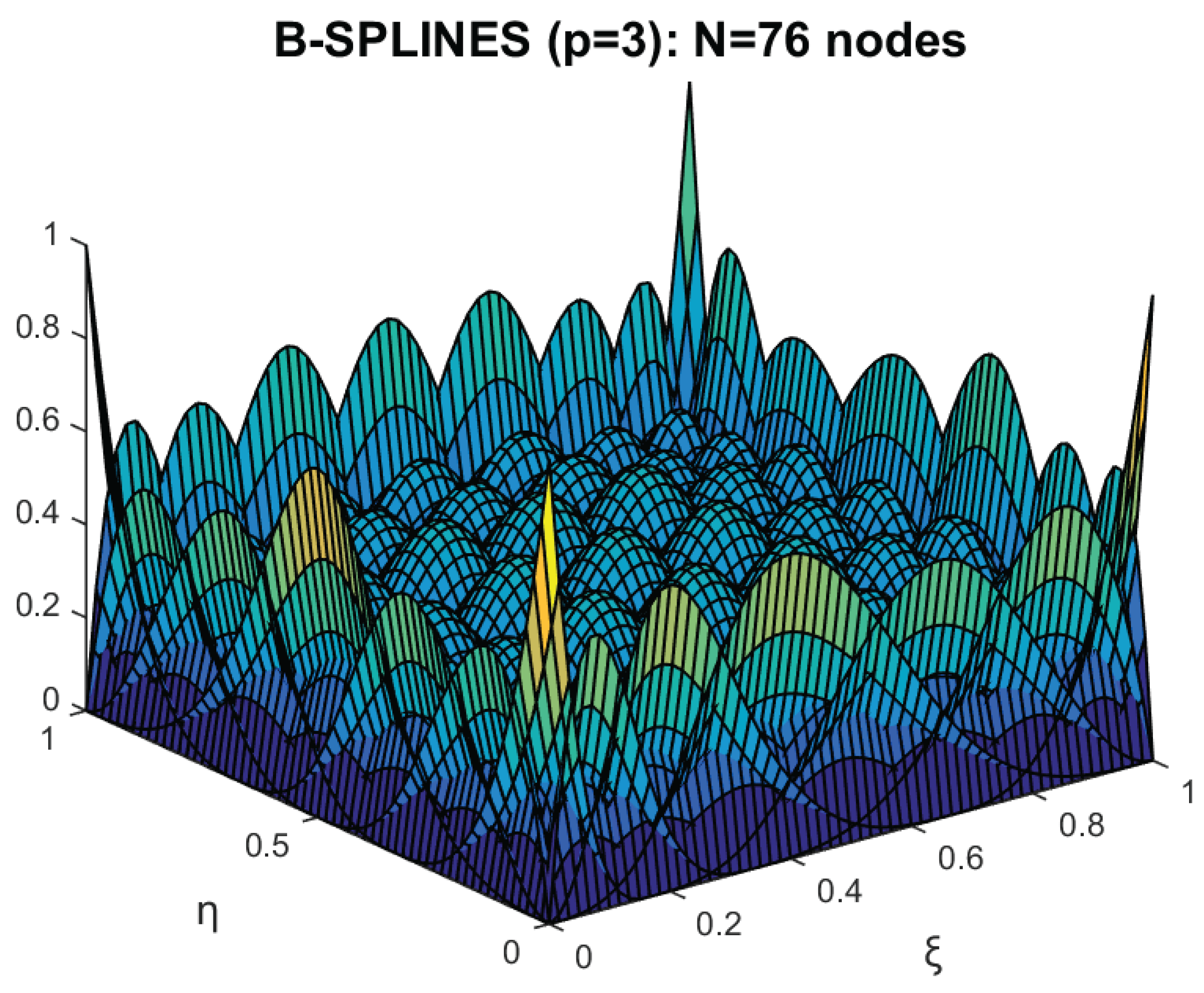

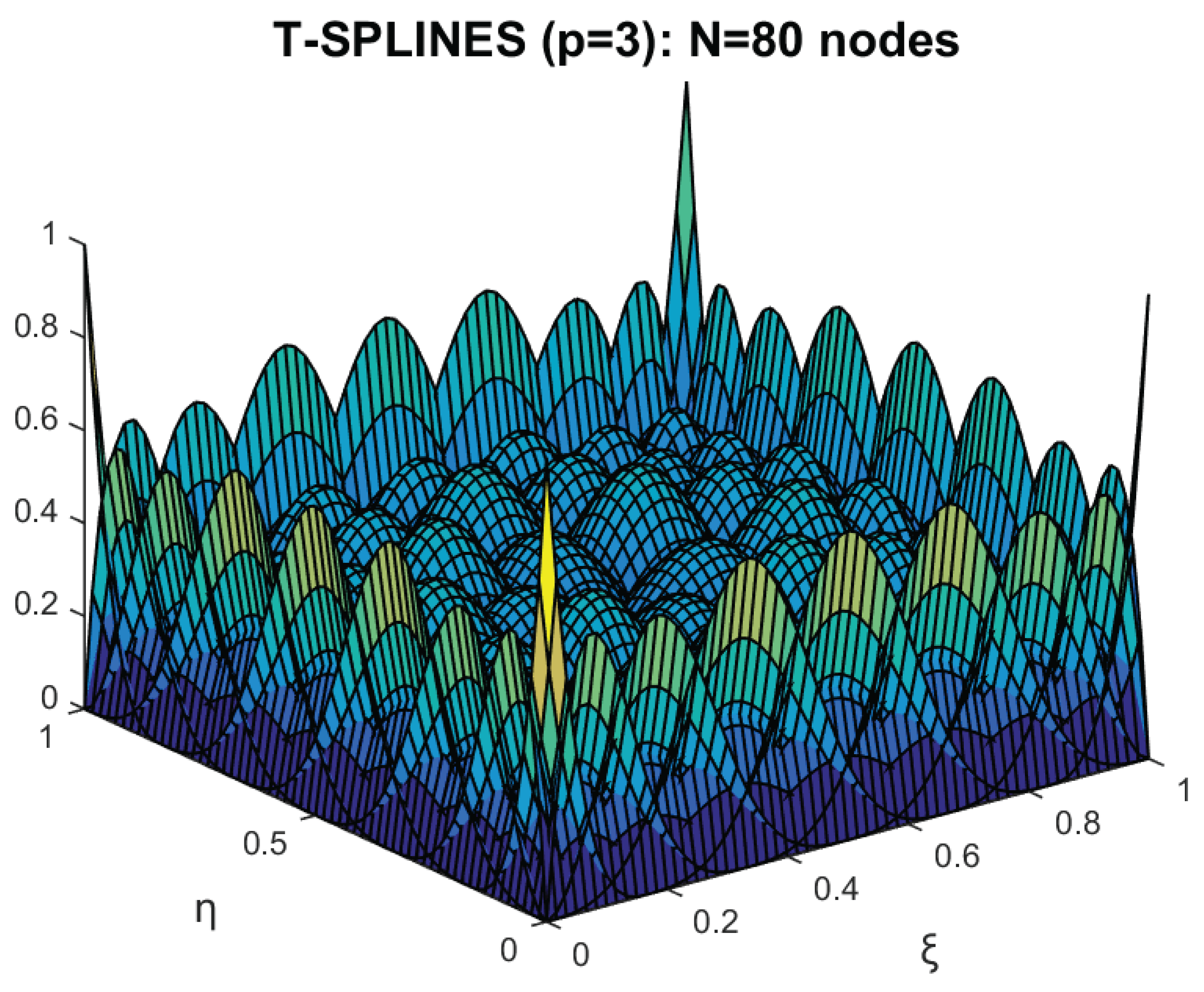

Starting from the abovementined B-spline tensor product with 81 control points, we proceed as follows. First, we remove the central node, resulting in a T-mesh with 80 nodes (see

Figure 14 in the parameter space, and

Figure 21b in the physical space). Second, we retain the central node but eliminate five boundary nodes, yielding a model with 76 nodes (see

Figure 10b in the reference square, and

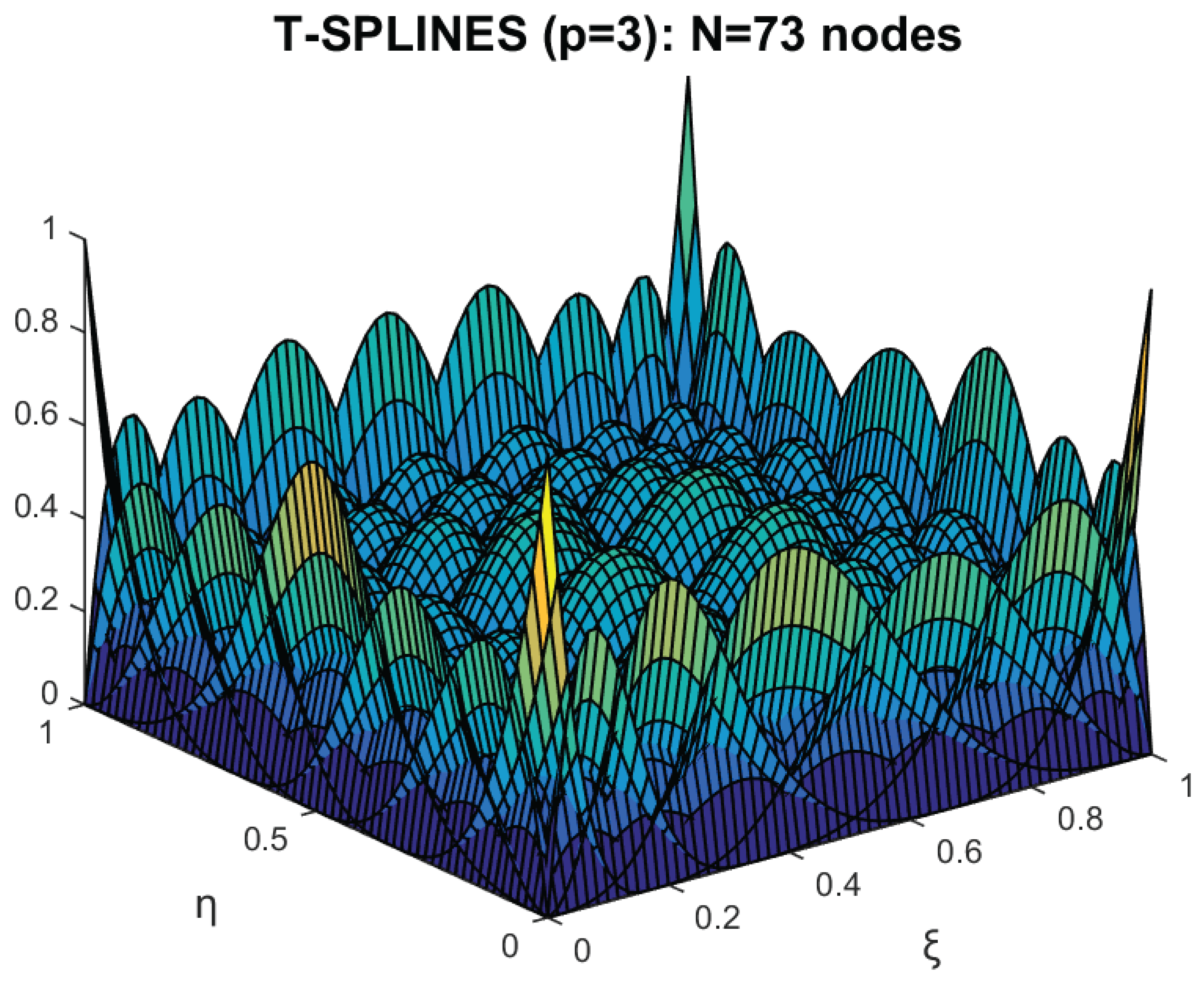

Figure 21c in the physical domain). Third, we further remove three internal nodes, ultimately producing a T-mesh with 73 nodes (see

Figure 10c in parametric space and

Figure 21d for the physical annular domain). For all these cases, the results are presented in

Table 8, where it can be observed that as the number of removed nodes increases, the error also increases.

For completeness,

Table 9 also presents the numerical solution based on the conventional normalized T-spline formulation [

18] (Equation (

47)). It can be observed that as the number of removed nodes increases, the error also increases.