Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Tensor product elements.

- Traditional transfinite elements (fully structured).

- Distorted tensor products.

- Elements with different degrees on opposite edges (partially unstructured).

- Coons elements.

2. Basic Theory

2.1. Bernstein Polynomials

2.2. Relationship Between Bernstein and Lagrange Polynomials

2.2.1. Univariate Approximation

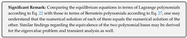

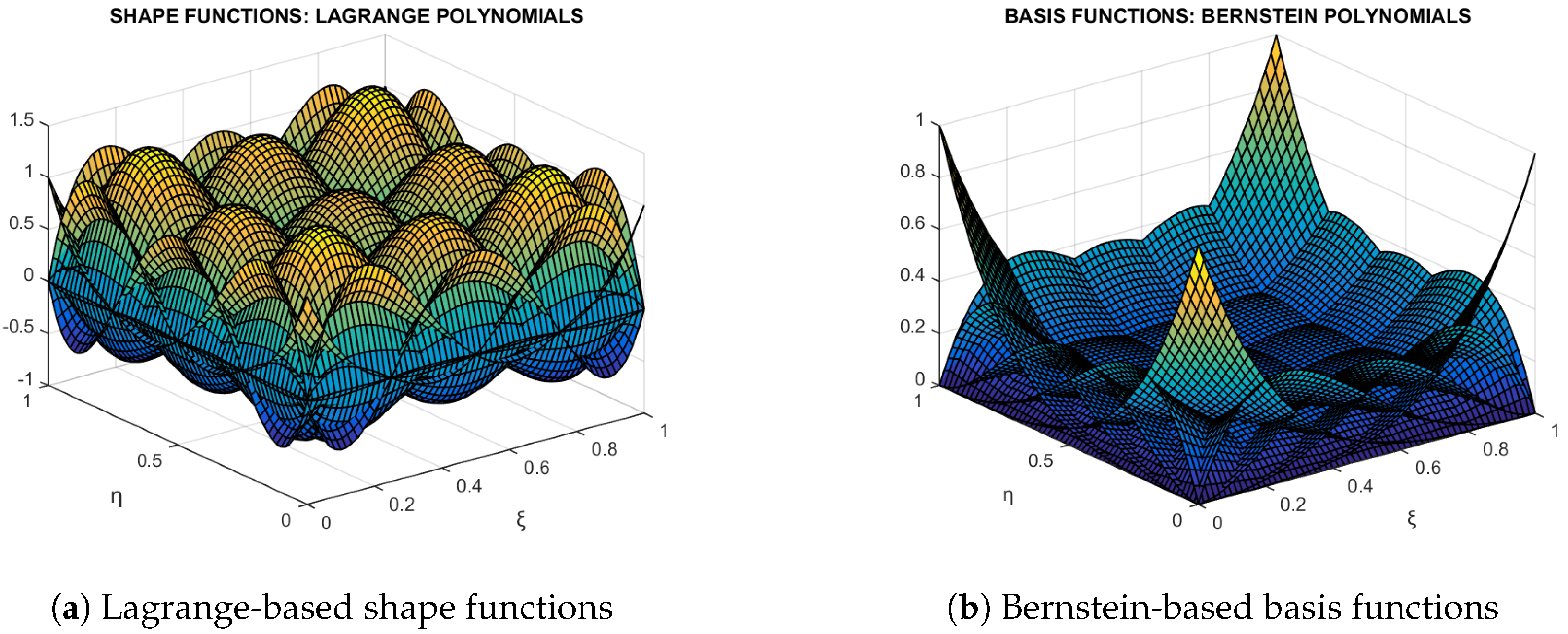

2.2.2. Tensor Products

2.3. Non-Uniform Lagrange Polynomials

3. Transformation Matrices Between Tensor Product Bernstein and Lagrange Functional Sets

3.1. Quadratic Interpolation

3.2. Generalization

3.3. Transformation of Structural Engineering Matrices (K, M)

3.4. Numerical Verification

3.5. Cross-Check

4. Traditional Transfinite Elements

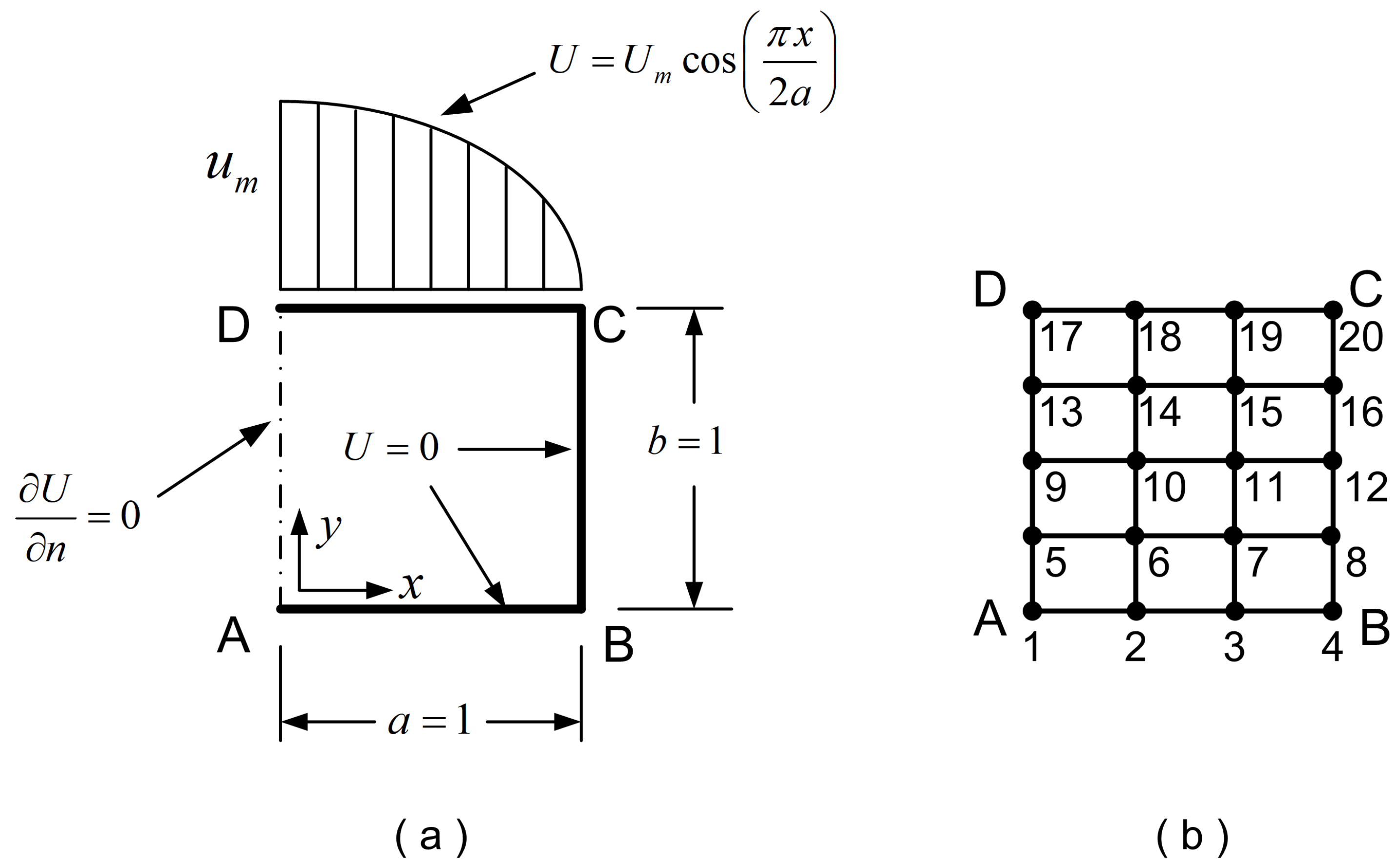

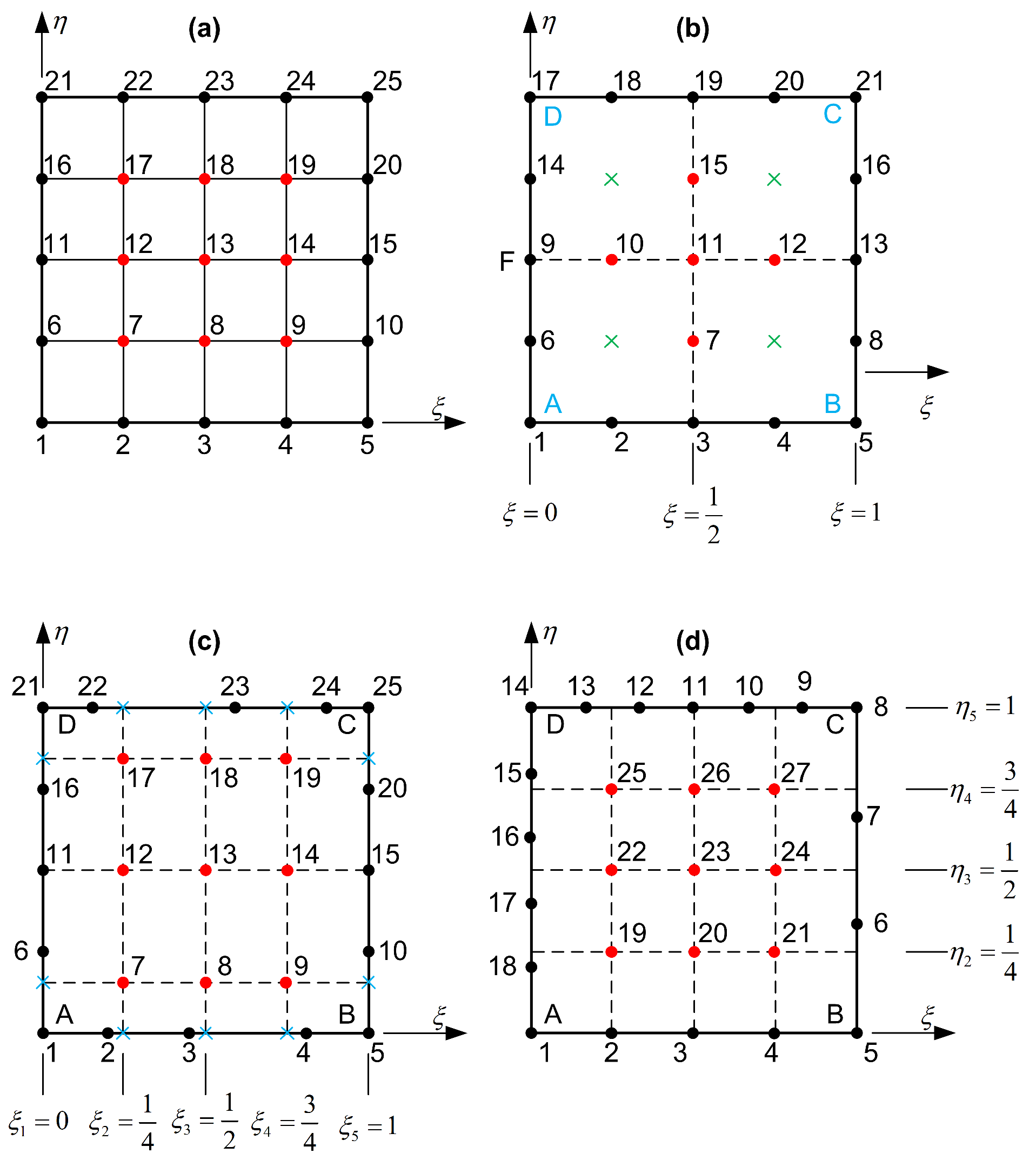

- Blending functions. For each direction ( or ), the number of blending functions equals to the number of corresponding sections, and thus their polynomial degree ( or , accordingly) equals to . For example, in the 21-node element shown in Figure 3, there are three stations per direction and thus . Perpendicularly to the -direction (toward -axis), the first vertical station is the edge AD (with nodes 1-6-9-14-17), the second vertical station consists of the nodes (3-7-11-15-19) and the third one includes the nodes along edge BC (with nodes 5-8-13-16-21). Similarly, perpendicularly to -direction (toward -axis), there are also three horizontal stations, i.e., the edge AB (with nodes 1-to-5), the isoline made of nodes (9-10-11-12-13), and eventually the edge DC (with nodes 17-to-21).

- Trial functions. These refer to the interpolation along the stations. In this example, each station consists of 5 nodes (4 node spans), and thus the polynomial degree will be (e.g. along the horizontal edge ), and similarly (e.g. along the vertical edge ). In general (for other discretizations), we may have .

4.1. General Relationships Between Initial and Transformed Bases

4.2. Structured Transfinite Elements

4.3. Numerical Verification of 21-Node Traditional Transfinite Element

5. Distorted Tensor Products of Partially Unstructured Transfinite Elements

- Tensor product Lagrange and tensor product non-rational Bernstein polynomials lead to the same error norm, although the condition number of equationes system is generally different [6].

5.1. Simple Distortion

5.1.1. Closed-Form Expressions

5.1.2. Numerical Verification

5.2. Distortion Combined with Node Refinement or Removal on Edges

- Shape functions associated with corner nodes, consist of three terms (influenced by all the three projectors ).

- Shape functions associated with intermediate nodes on the edges, consist of one term, which is related to the projector having as subscript the axis perpendicular to the current edge. For example, the shape functions of nodes along edge are influenced by only the projector .

- Shape functions associated with internal nodes equal to the tensor product of the blending functions only.

5.2.1. Justification

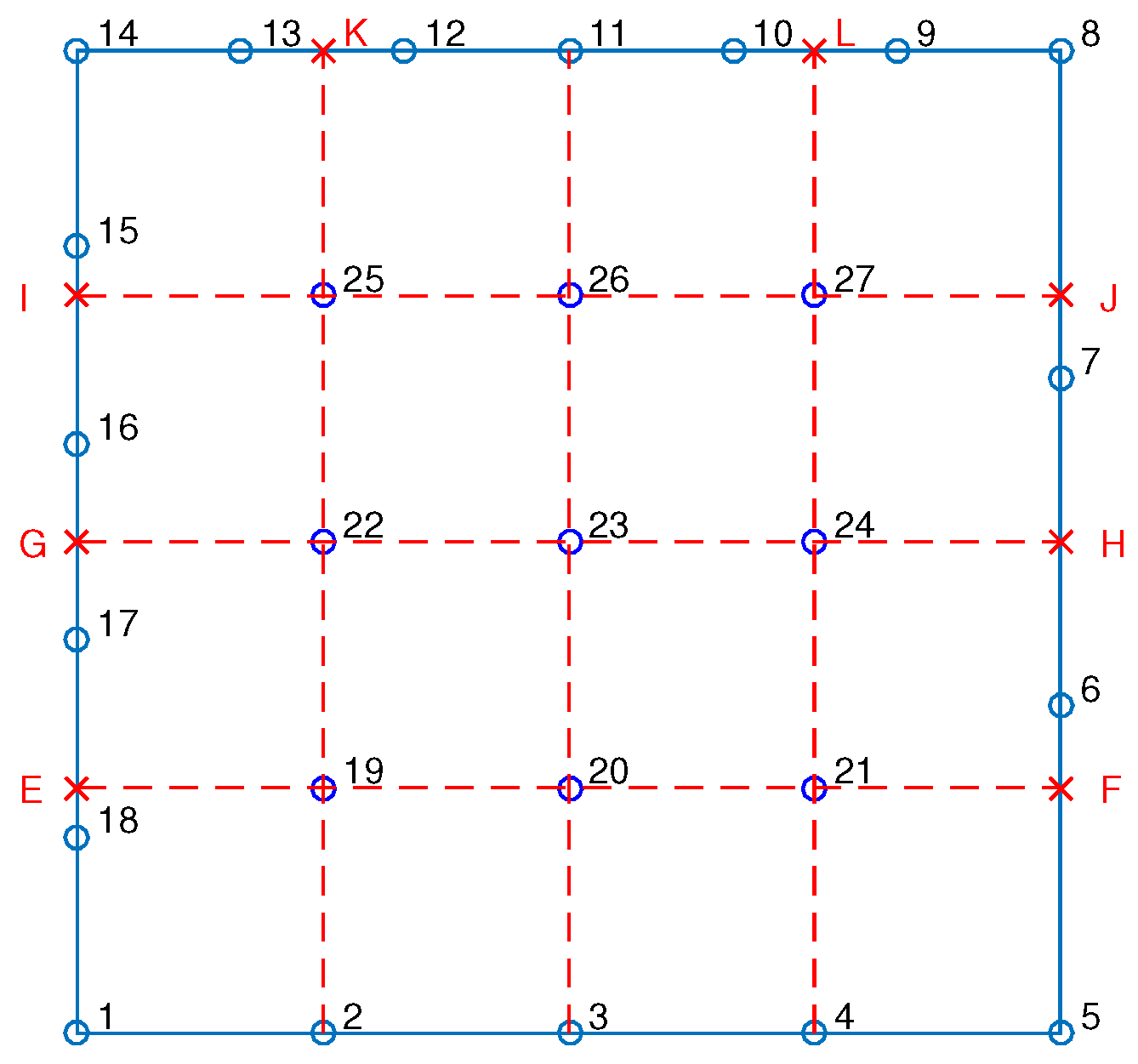

- The function consists of six nodal values , which define 5 node spans and fully define a polynomial of degree 5. Note that the artificial nodes are not included because they are not needed.

- The function consists of 5 nodal values (4 node spans), and thus fully define a polynomial of degree 4. Note that the artificial node K, on the boundary, is required to determine the missing end of nodal sequence.

- The function consists of 5 nodal values (4 node spans), and thus fully define a polynomial of degree 4. All entries of nodal sequance are primary nodes which belong to the 27-node element.

- The function consists of 5 nodal values (4 node spans), and thus fully define a polynomial of degree 4. Note that the artificial node L is required to determine the missing end of nodal sequence.

- The function consists of four nodal values , which define 3 node spans and fully define a polynomial of degree 3. Note that the artificial nodes , on the boundary, are not included because they are not needed.

- The projector includes 2 out of the 8 artificial nodal values.

- The projector includes the rest 6 out of the 8 artificial nodal values.

- The subtractive corrective projector includes all the 8 artificial nodes.

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

- We notice the terms: , coming from and .

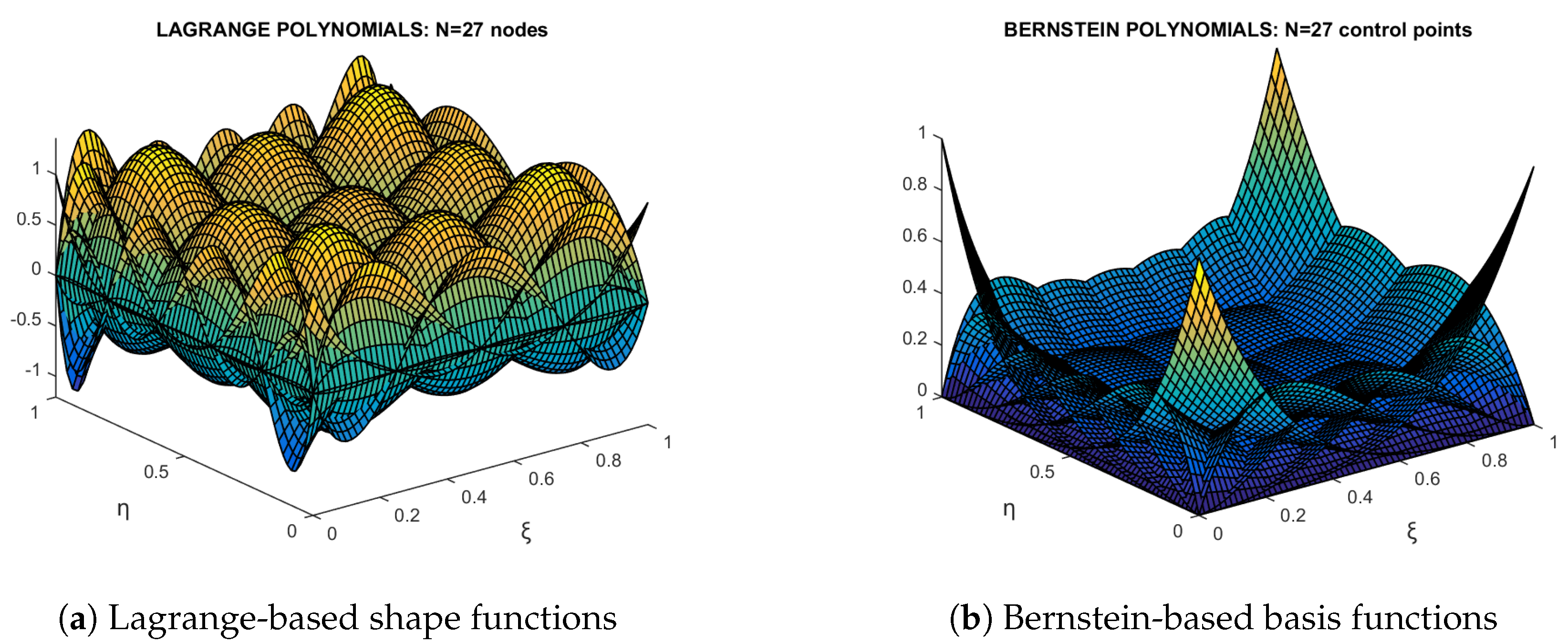

- It the transformation matrix which fulfils the relationship is determined by applying it to all the 27 nodal points of the element, we receive that det.

- The recalculation of the Lagrange based bivariate shape functions in terms of the Bernstein based ones , using the relation , shows a large error (about ) in the interior of the element, whereas on the boundary and at the nodal points it vanishes.

- A similar discrepancy was obseved when the relationship was applied to more points, and this least-squares scheme led again to a similar deviation between the initial and the recalculted ’s.

5.2.2. Numerical Verification

- The requirement to use the parameters defined by the nodal points of the Lagrange model, and then map the control points to the nodal points , leads to coincidence between them.

- In both systems the determinant of the Jacobian all over the rectangular domain equals to unity.

- The error norm was found to be slightly different in each system: for the Lagrange polynomials and for the Bernstein ones.

6. Coons Interpolation

6.1. Numerical Verification

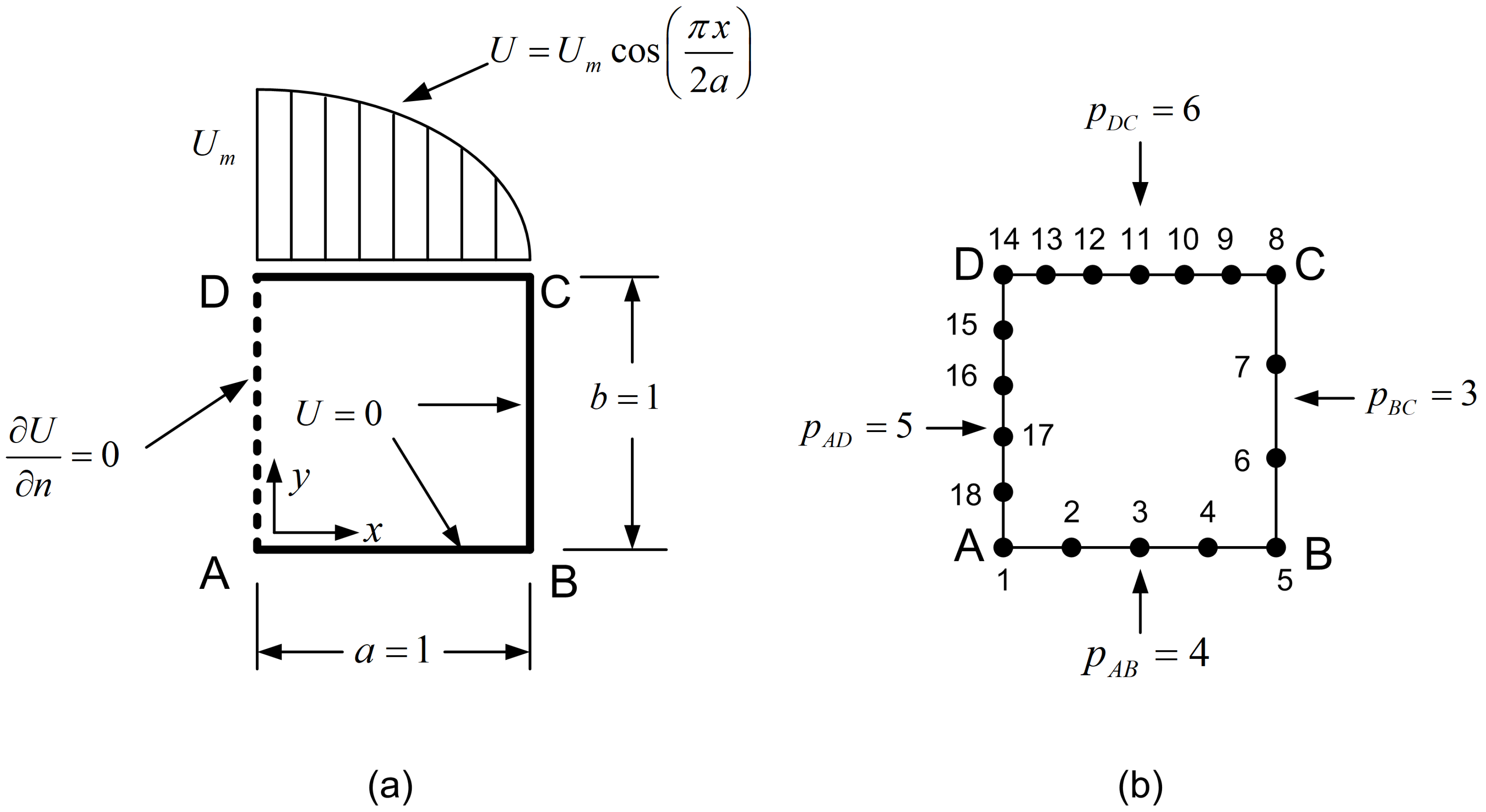

7. Numerical Solution of an Eigenvalue Problem

- Coons interpolation (18 DOFs).

- Tensor product uniform (25 DOFs).

- Tensor product distorted (25 DOFs).

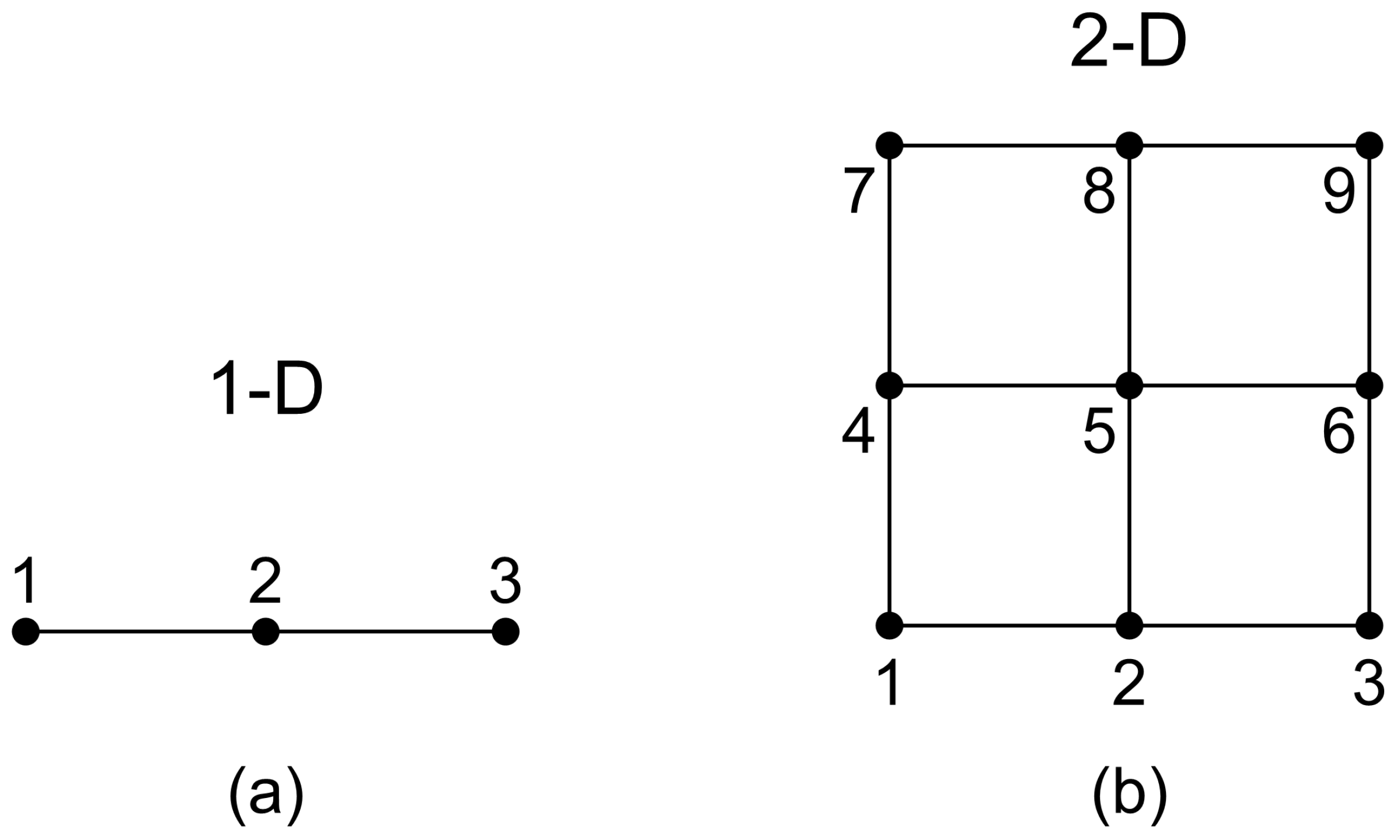

- Transfinite non-uniform (27 DOFs, as shown in Figure 2a).

8. Discussion

- (1)

- For four broad classes—namely, (i) Coons elements, (ii) tensor-product elements, (iii) traditional transfinite elements with a structured pattern of internal nodes, and (iv) distorted tensor-product elements—Bernstein polynomials can serve as a direct replacement for Lagrange polynomials of the same degree, with identical accuracy.

- (2)

- In a fifth class, involving transfinite elements with arbitrary boundary nodes combined with a tensor-product distribution of internal nodes, Bernstein polynomials may also replace Lagrange polynomials of the same degree. However, this substitution does not guarantee identical results. While the overall performance of such arbitrarily-noded transfinite elements remains sufficient for practical use, further investigation is warranted, particularly in cases involving non-uniform polynomial degrees.

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. MATLAB Script for Matrix Comparison

|

References

- Zienkiewicz, O.C. The Finite Element Method, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1977; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bathe, K.J. Finite Element Procedures, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: New Jersey, USA, 1996; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, J.A.; Hughes, T.J.R.; Bazilevs, Y. Isogeometric analysis: towards integration of CAD and FEA, 1st ed.; Wiley: Chichester, USA, 2009; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Provatidis, C.G. Non-rational and rational transfinite interpolation using Bernstein polynomials. International Journal of Computational Geometry and Applications 2022, 32, 55–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provatidis, C. Transfinite patches for isogeometric analysis. Mathematics 2025, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provatidis, C. Bézier versus Lagrange polynomials-based finite element analysis of 2-D potential problems. Advances in Engineering Software 2014, 73, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provatidis, C.; Eisenträger, S. Macroelement analysis in T-patches using Lagrange polynomials. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Provatidis, C.G. Precursors of Isogeometric Analysis: Finite Elements, Boundary Elements, and Collocation Methods. Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, W.J.; Hall, C.A. Transfinite element methods: Blending-function interpolation over arbitrary curved element domains. Numerische Mathematik 1973, 21, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenträger S, Eisenträger J, Gravenkamp H, Provatidis CG. High order transition elements: The xNy-element concept, Part II: Dynamics. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2021, 387, 114145. [CrossRef]

- Coons, S.A. Surfaces for computer-aided design of space forms. MIT 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Farin, G. Curves and Surfaces for CAGD; Morgan Kaufmann-Elsevier: USA. [CrossRef]

- Courant, R.; Hilbert, D. Methods of mathematical physics (1st English ed., Vol. I).; InterScience: New York, USA, 1966; (translated and revised from the German original). [Google Scholar]

| Mode | Coons (18 DOFs) | Tensor Product Uniform (25 DOFs) | Tensor Product Distorted (25 DOFs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 0.0175 | 0.0557 | 0.0557 |

| 3 | 0.2229 | 0.7256 | 0.7256 |

| 4 | 0.0141 | 0.0557 | 0.0557 |

| 5 | 0.3117 | 0.0557 | 0.0557 |

| 6 | 13.9526 | 2.1910 | 2.1910 |

| Mode | Lagrange-Based (27 DOFs) | Bézier-Based (27 DOFs) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – |

| 2 | 0.0534 | 0.0420 |

| 3 | 0.6940 | 0.5404 |

| 4 | 0.0498 | 0.0361 |

| 5 | 0.0422 | 0.0309 |

| 6 | 2.1458 | 2.0581 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).