Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 65N06; 65B99

1. Introduction

2. Conventional IGA Procedures

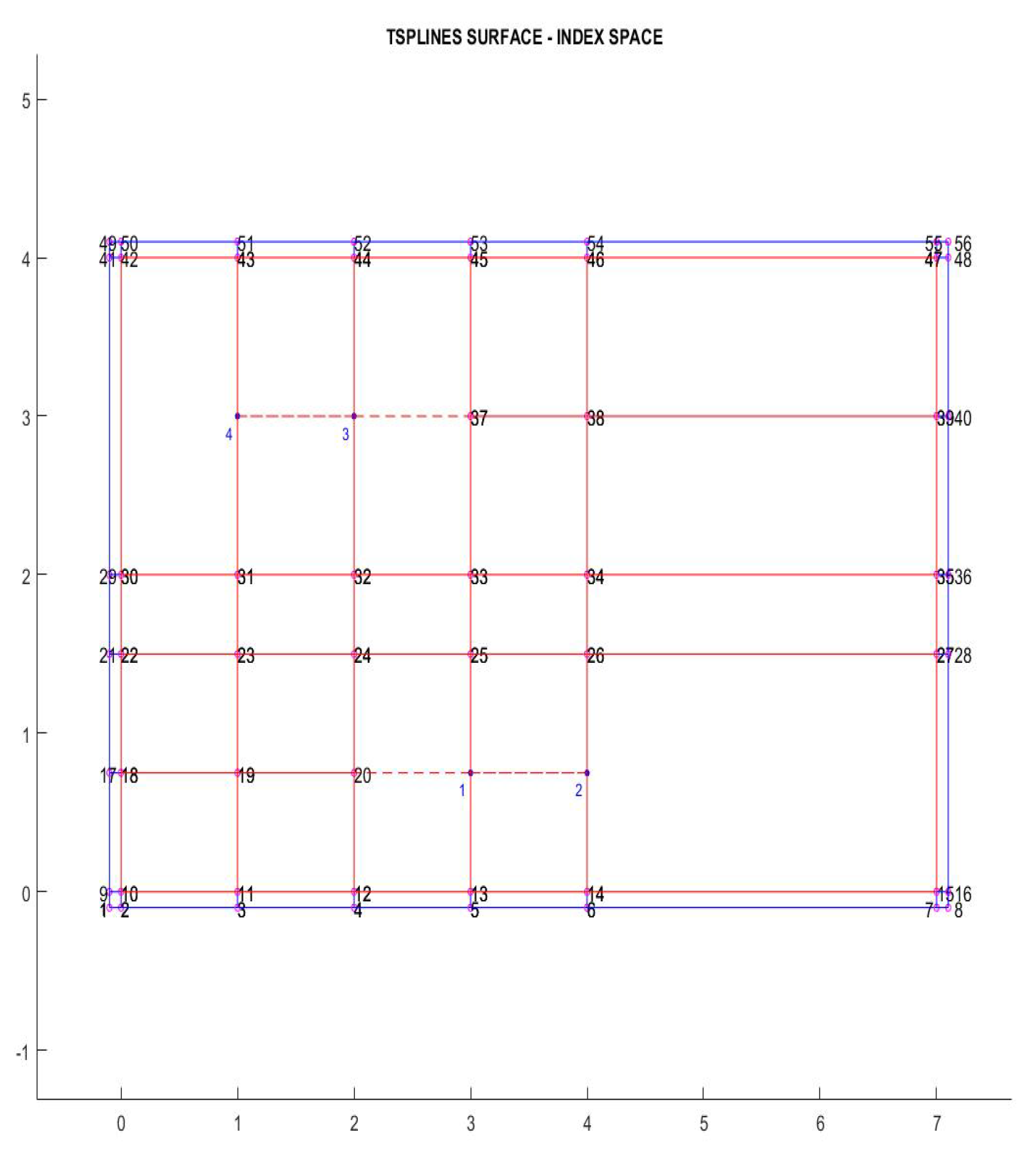

2.1. Tensor-Product of Local Knot Vectors (MODEL-1)

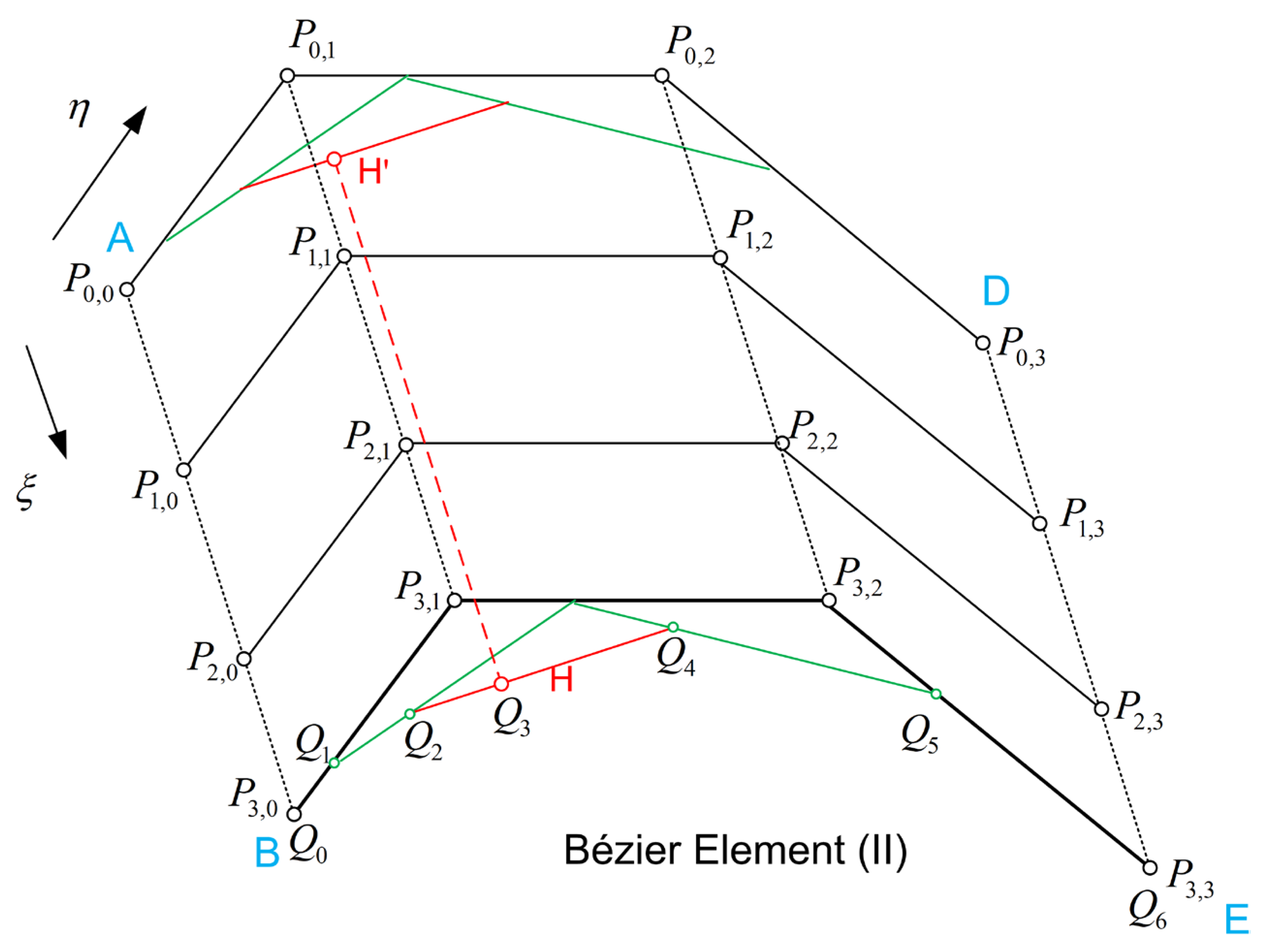

2.2. The Standard Utilization of the Bézier Extraction Operator (MODEL-2)

3. The Proposed Computational Procedure (MODEL-3 and MODEL-4)

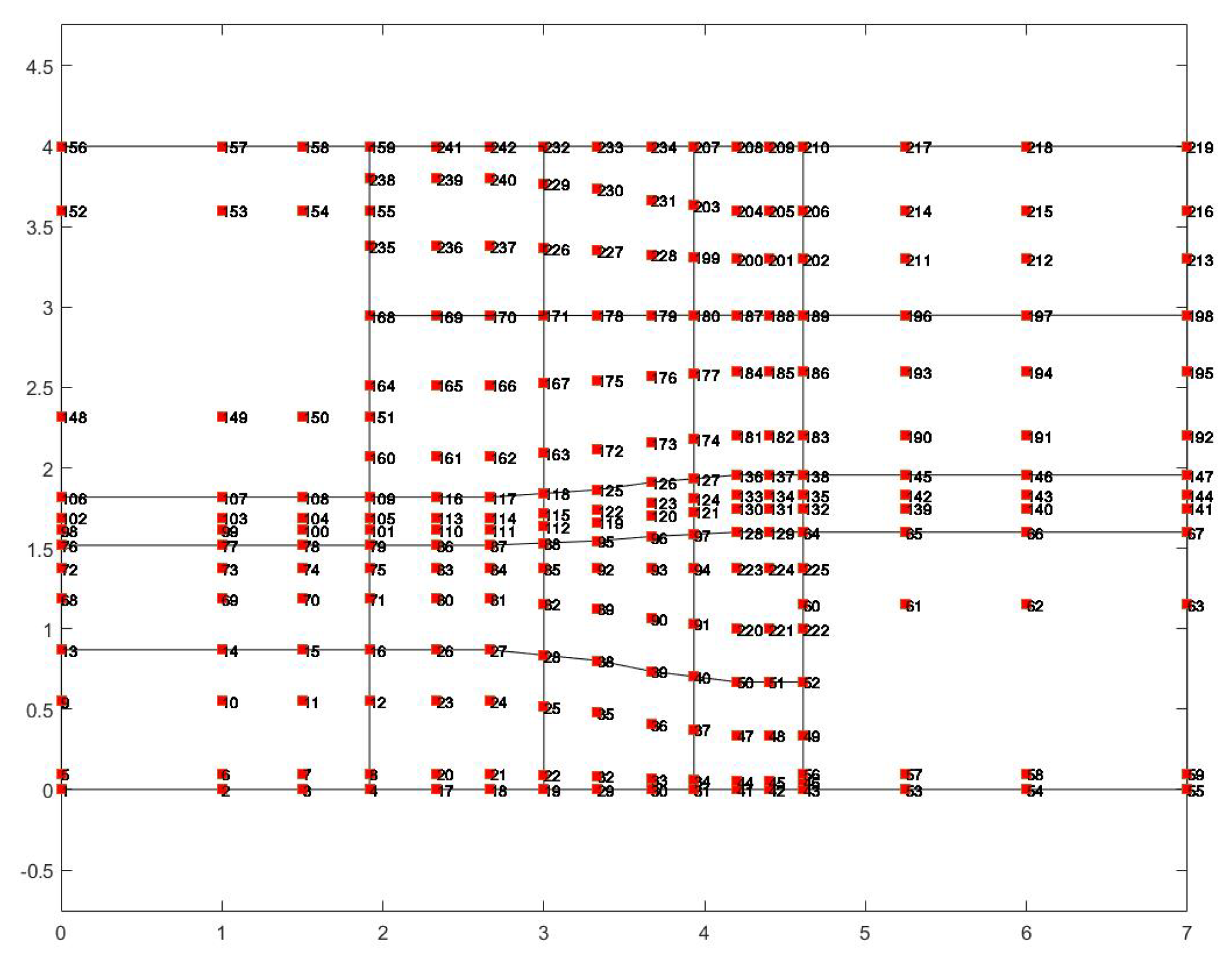

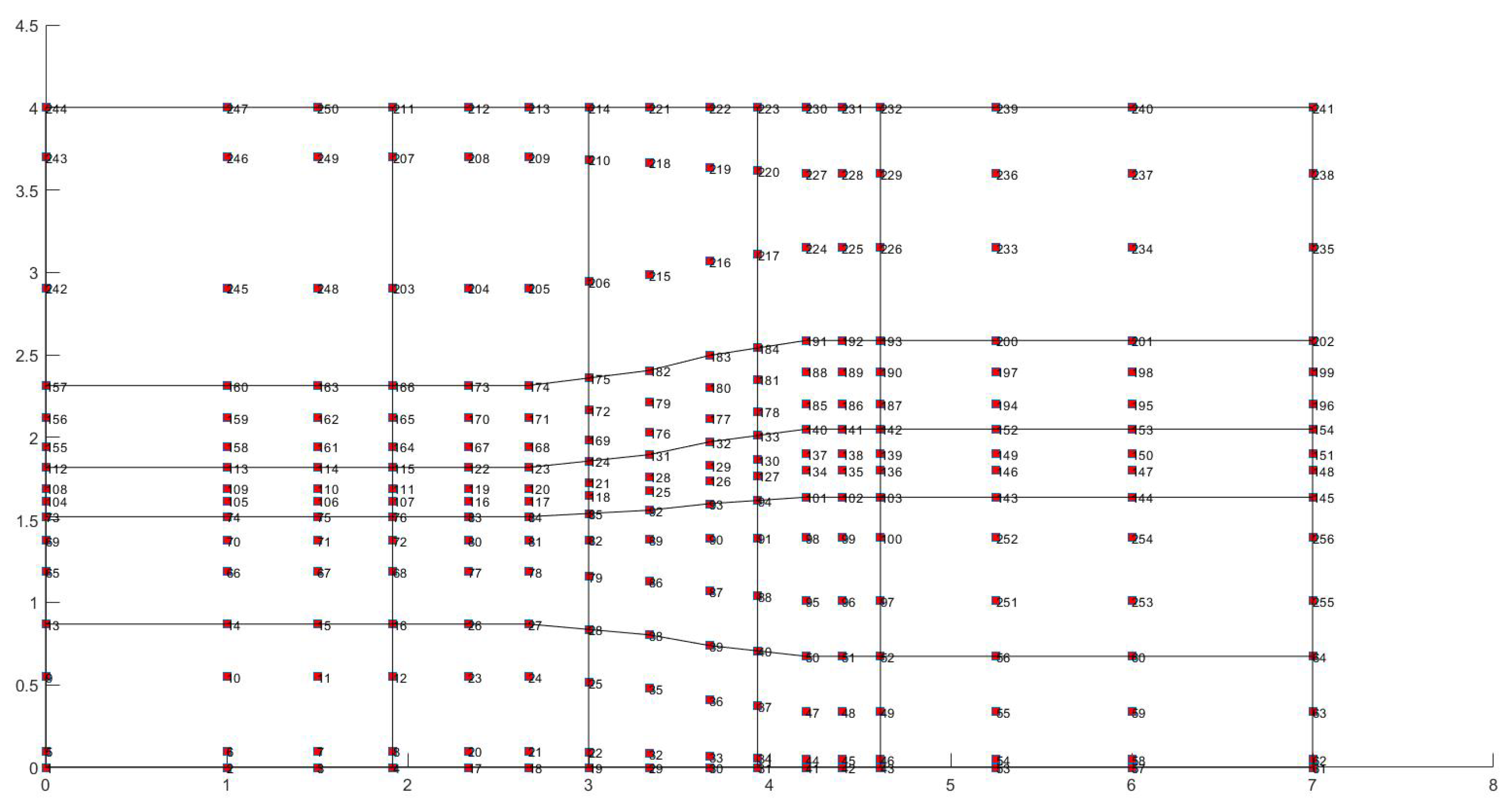

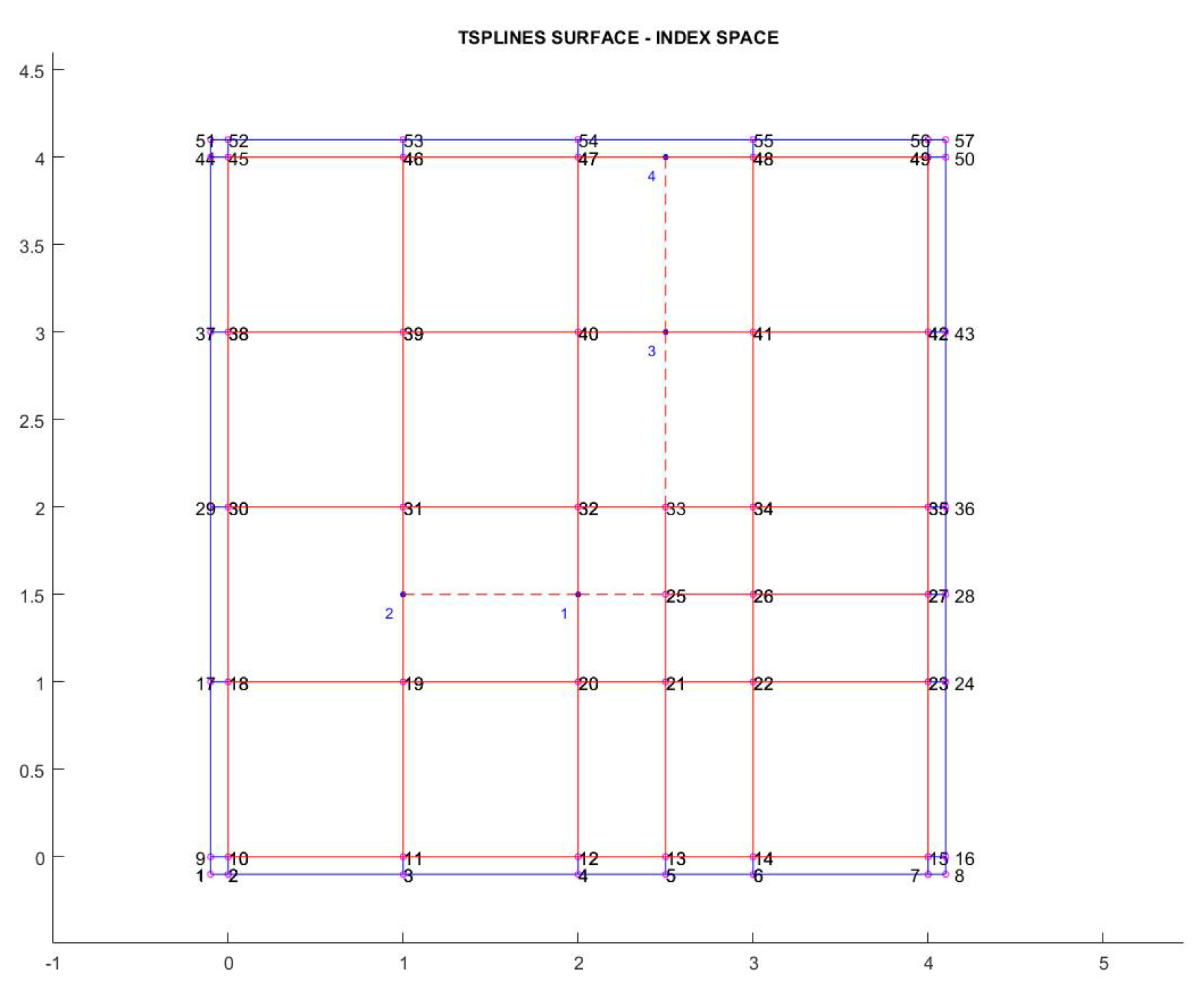

3.1. General Theory (MODEL-3)

- Based on the initial nP control points P and the given index space, create nele analysis-suitable T-spline elements.

- Apply the BEXT matrix Ce in each of the above nele T-spline elements, and thus determine:

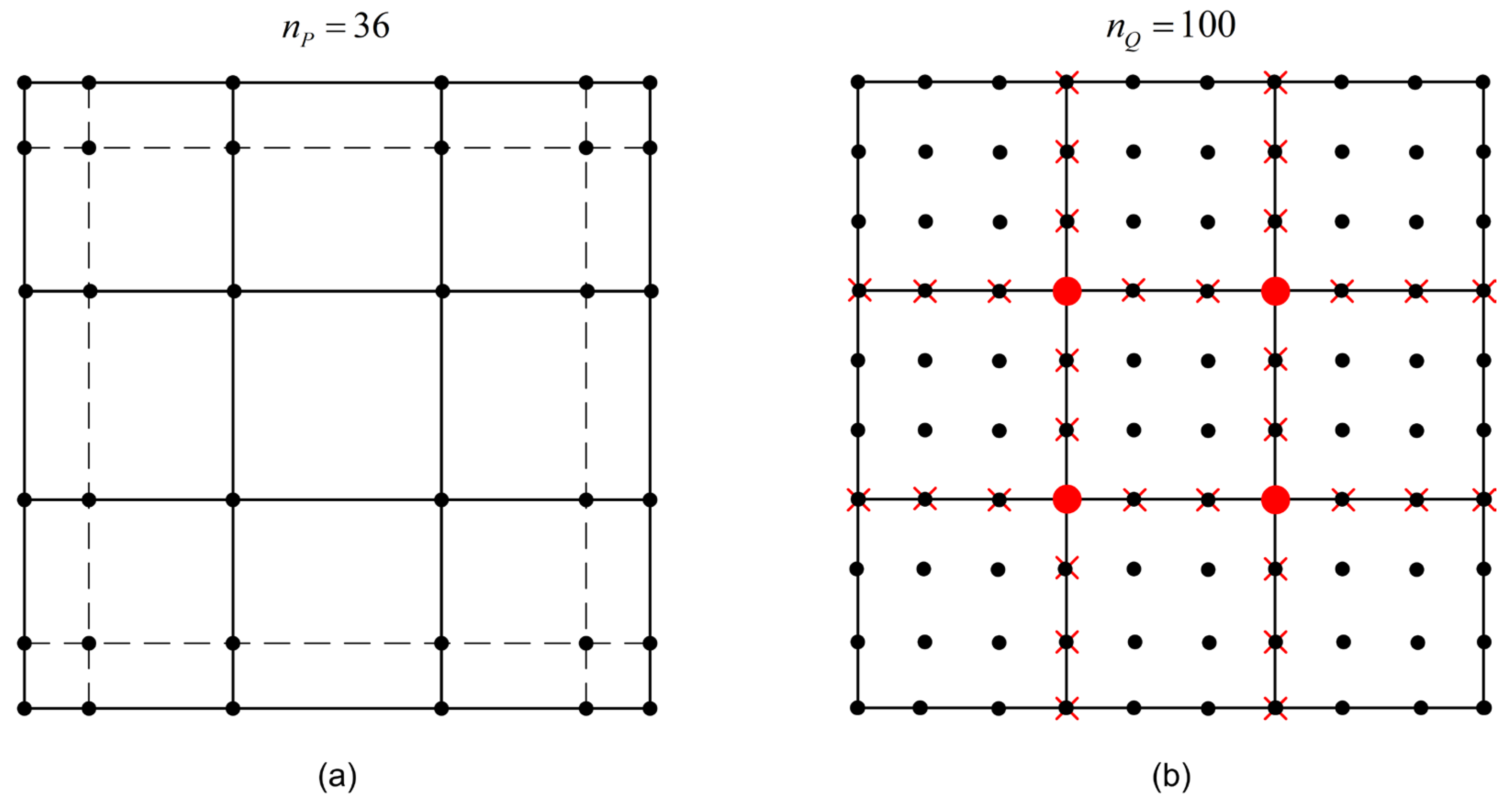

3.2. Estimation of Control Points nQ for C0-Continuity

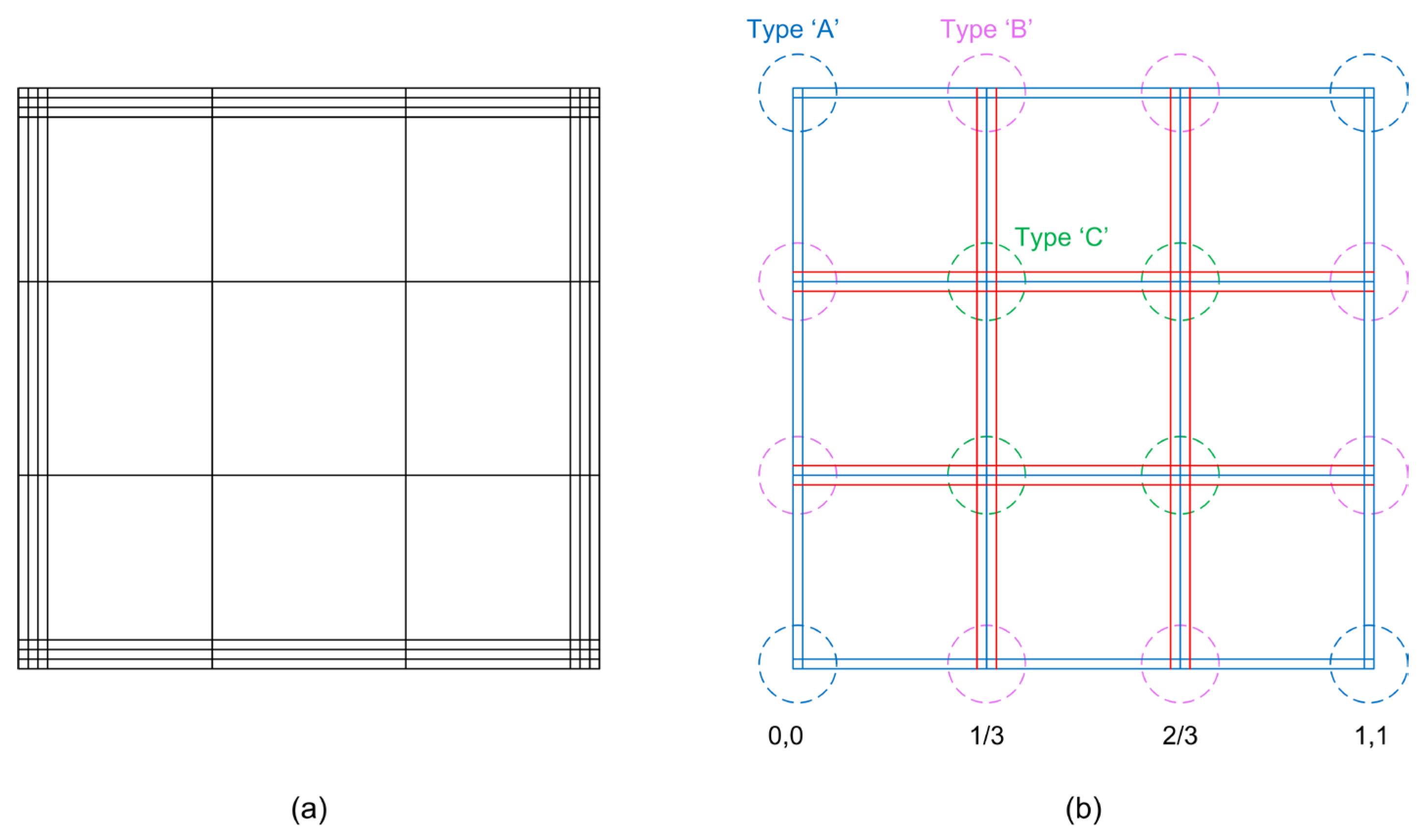

- Type A: Knots related to the corners of the patch (4 corners with 4 anchors per corner).

- Type B: Knots related to intermediate places along the four edges, not coinciding with the corners (6 anchors per initial knot).

- Type C: Knots related to initial knots in the interior of the patch (9 anchors per initial knot).

3.3. On the Uniqueness of Control Points

- Each of the four control points at the intersections between horizontal and vertical inter-element boundaries (illustrated in Figure 2b by red circle: 🔴), belongs to four elements, while must be countered only once. Therefore, instead of the blind number 4 × 4 = 16, we must consider only 4 of them, which means that we have 12 additional fictitious points to subtract from 144.

- Each of the thirty-two control points along the inter-element boundaries (illustrated in Figure 2b by red cross: x), belongs to two elements, and therefore a blind computation would results in 32 × 2 = 64 points. To obtain the exact number, half of them (i.e., 32) must be subtracted from 144.

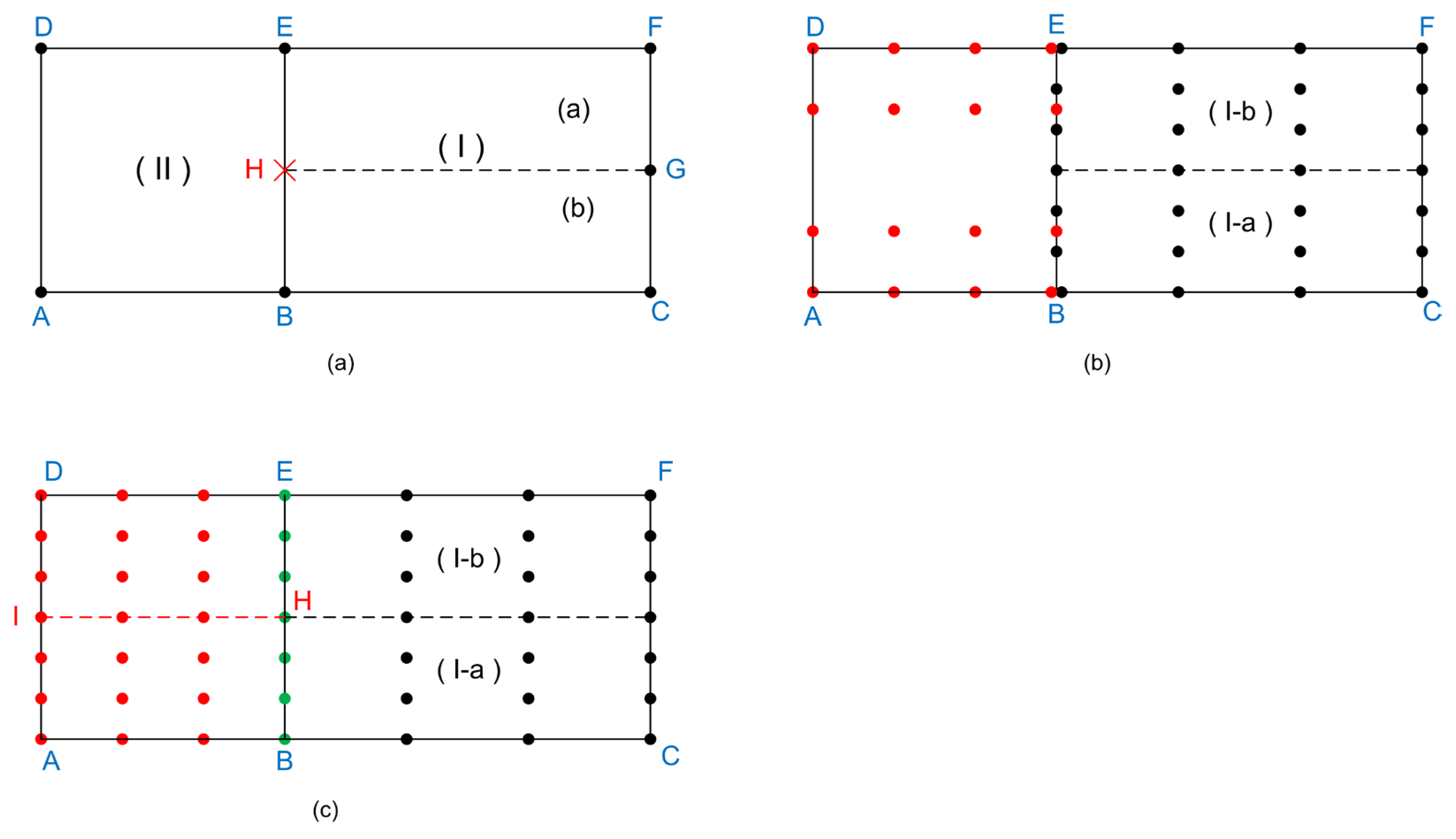

3.4. Fixing C0 and G0-Incompatibilities (MODEL-4)

4. Matrix Formulation

5. Results

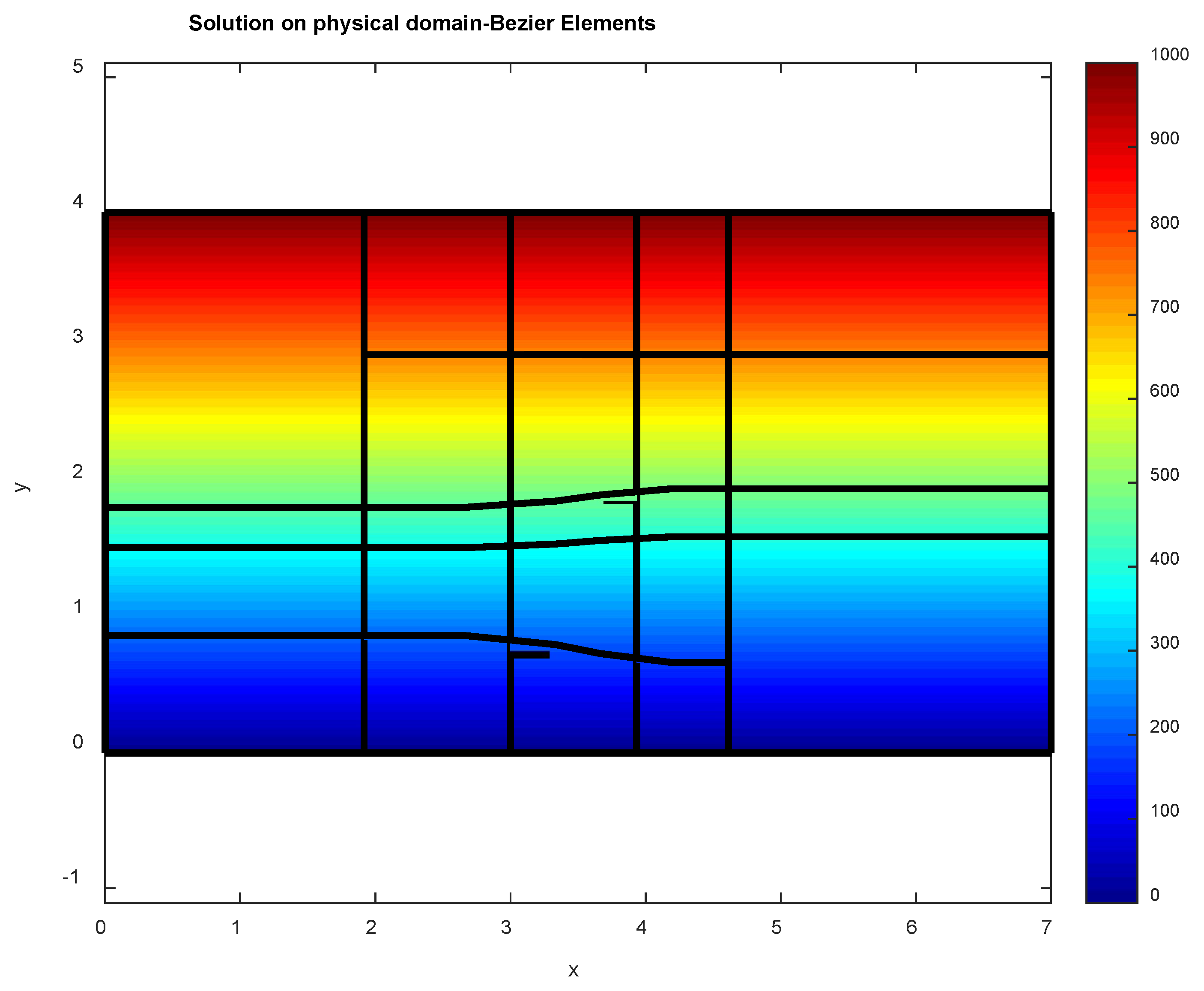

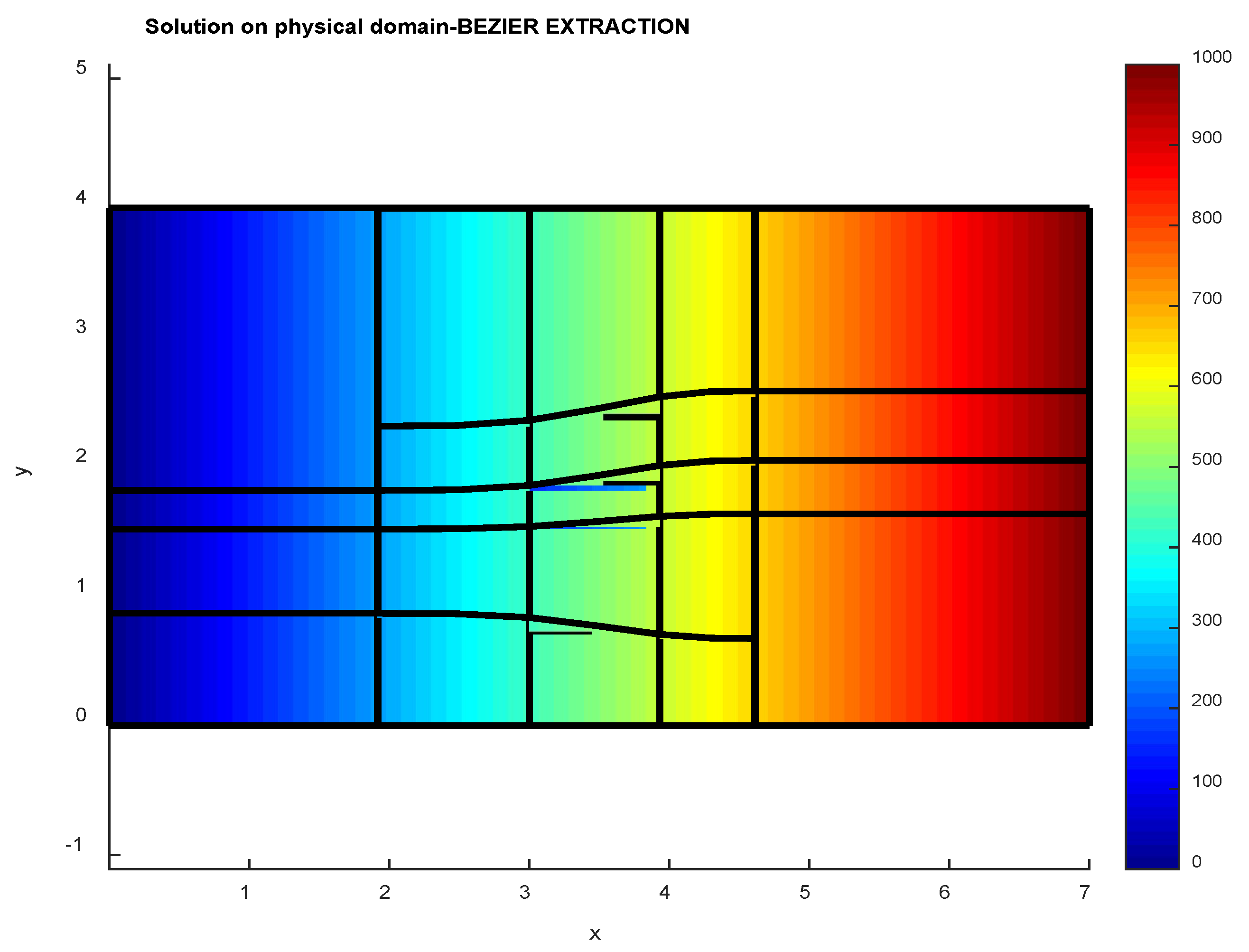

5.1. EXAMPLE 1: Vertical Heat Flow

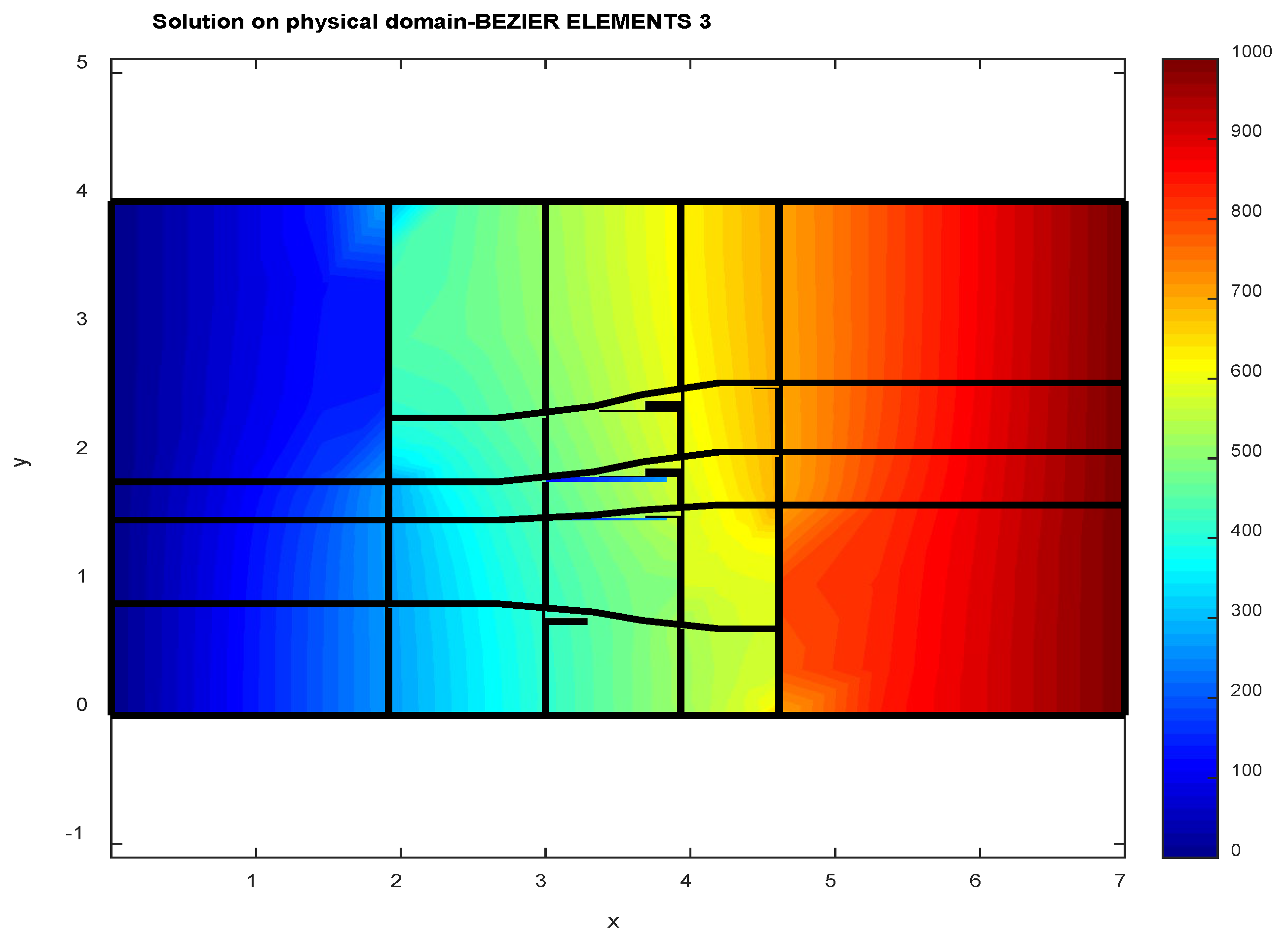

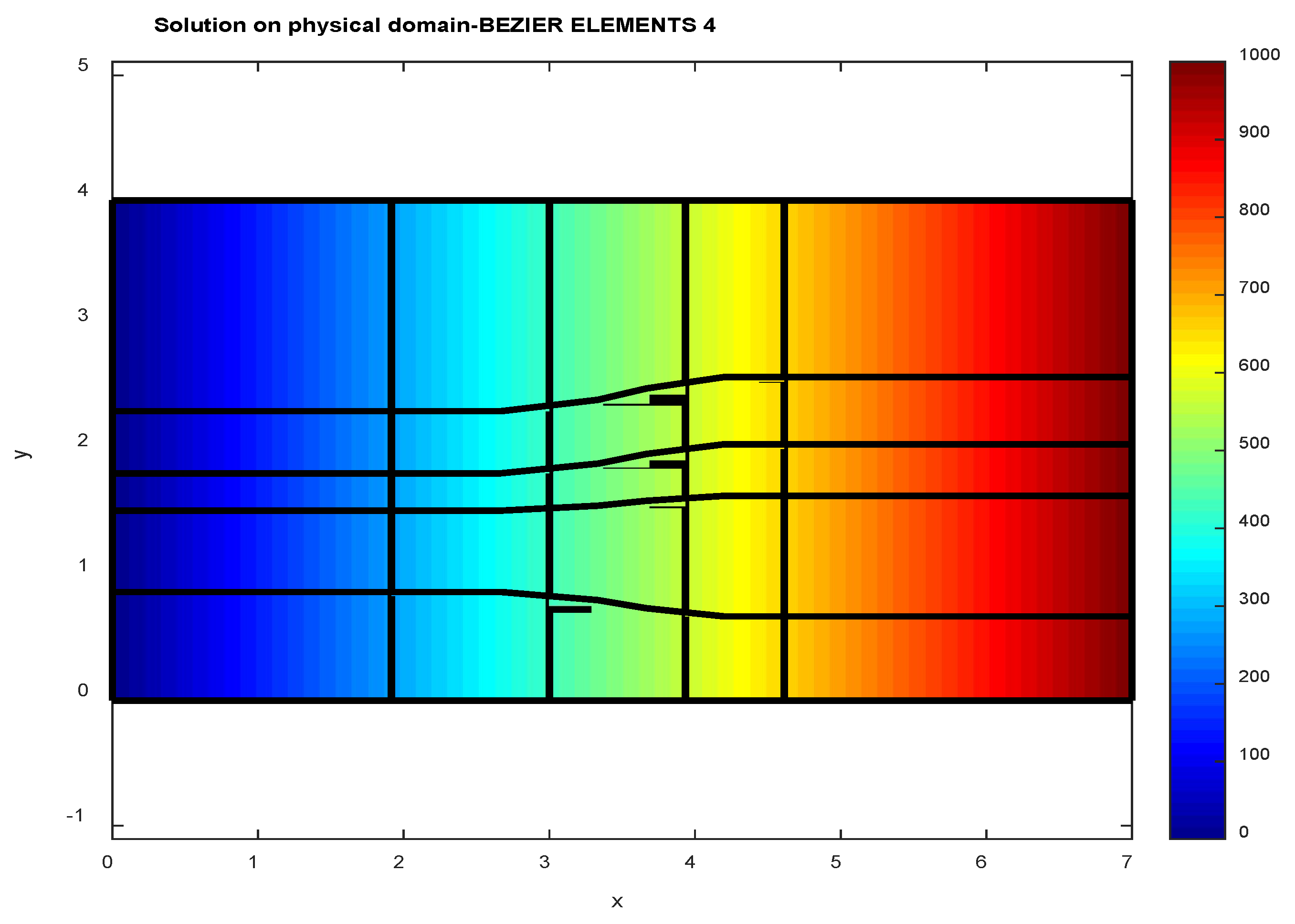

5.2. EXAMPLE 2: Horizontal Heat Flow

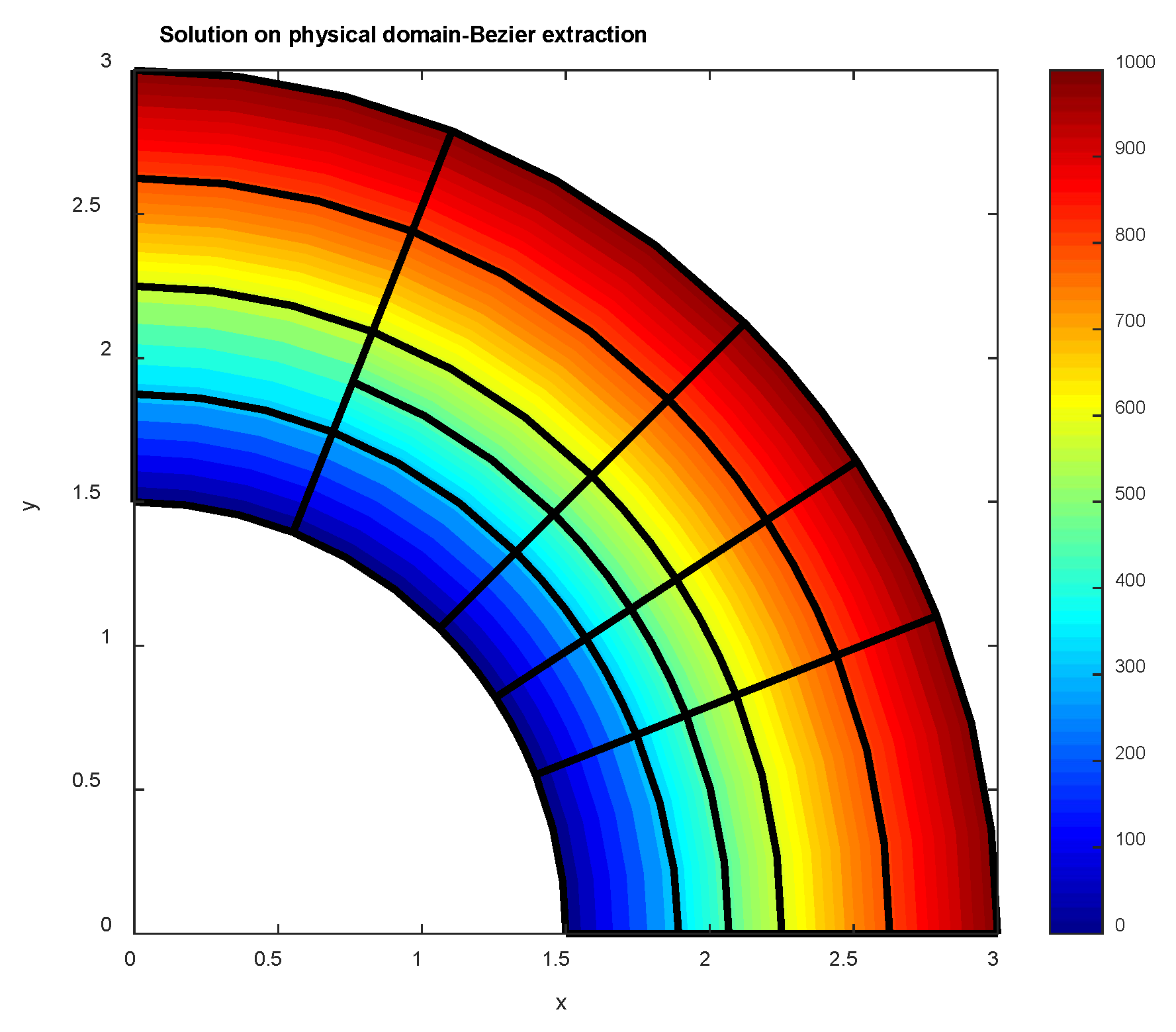

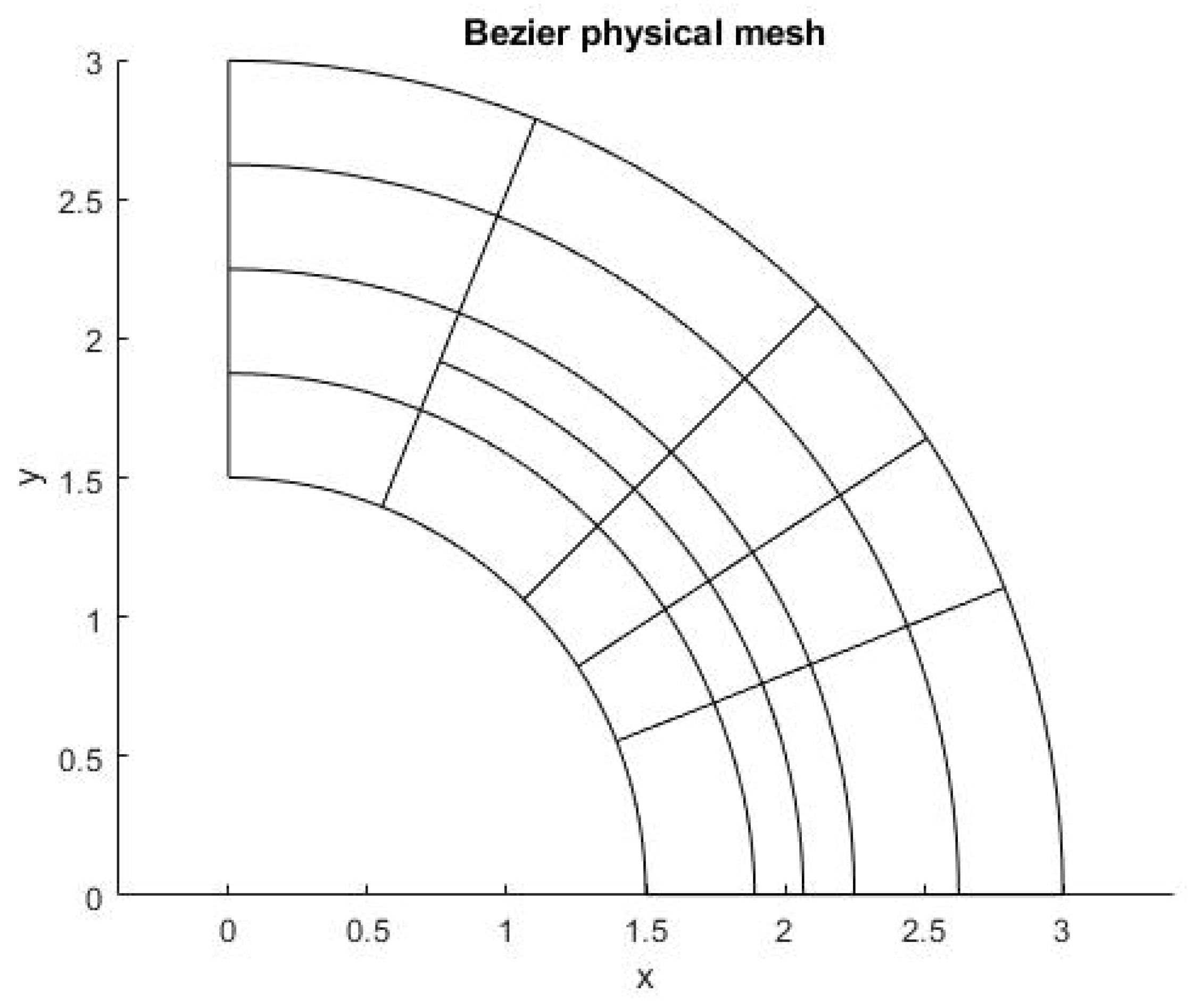

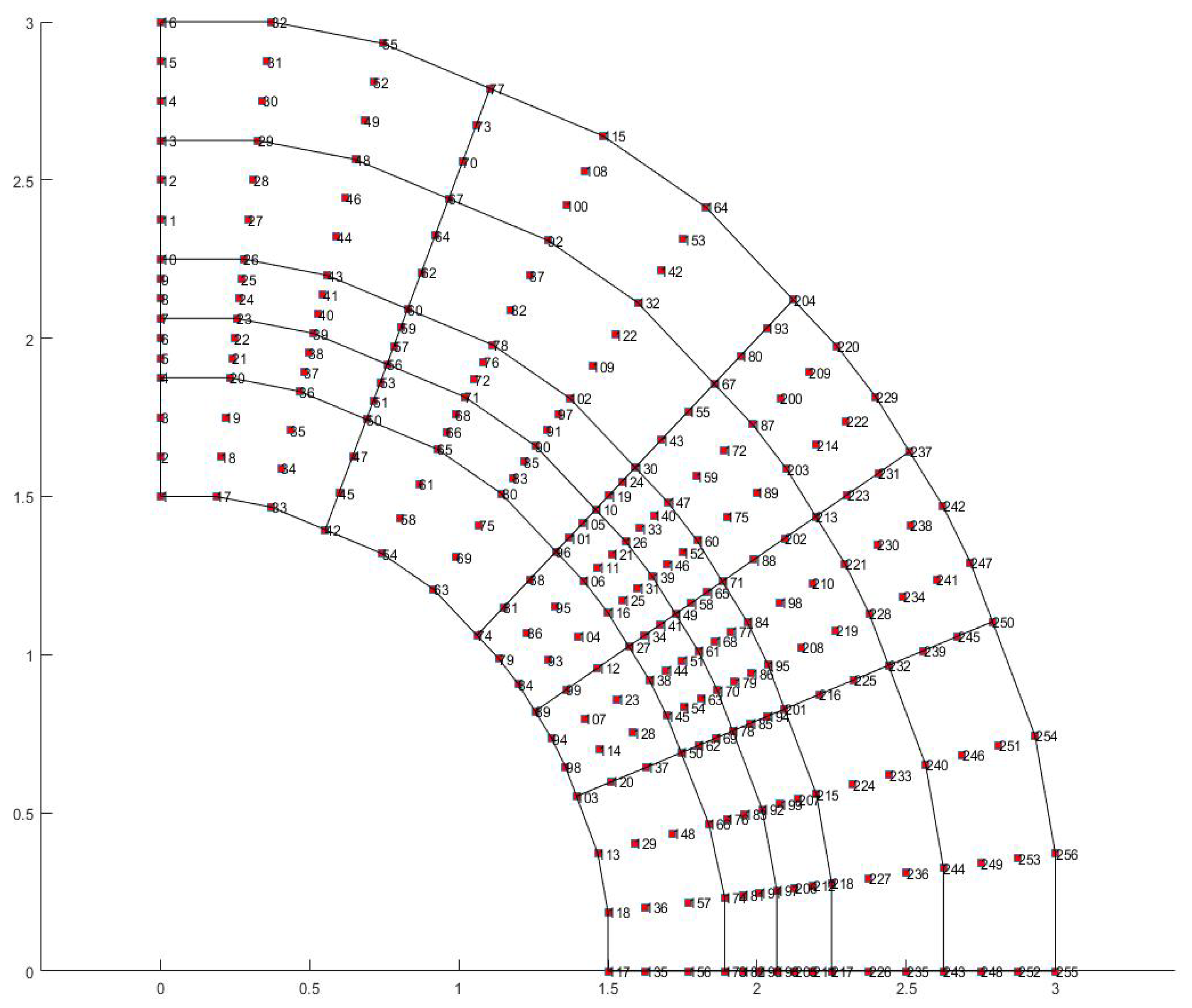

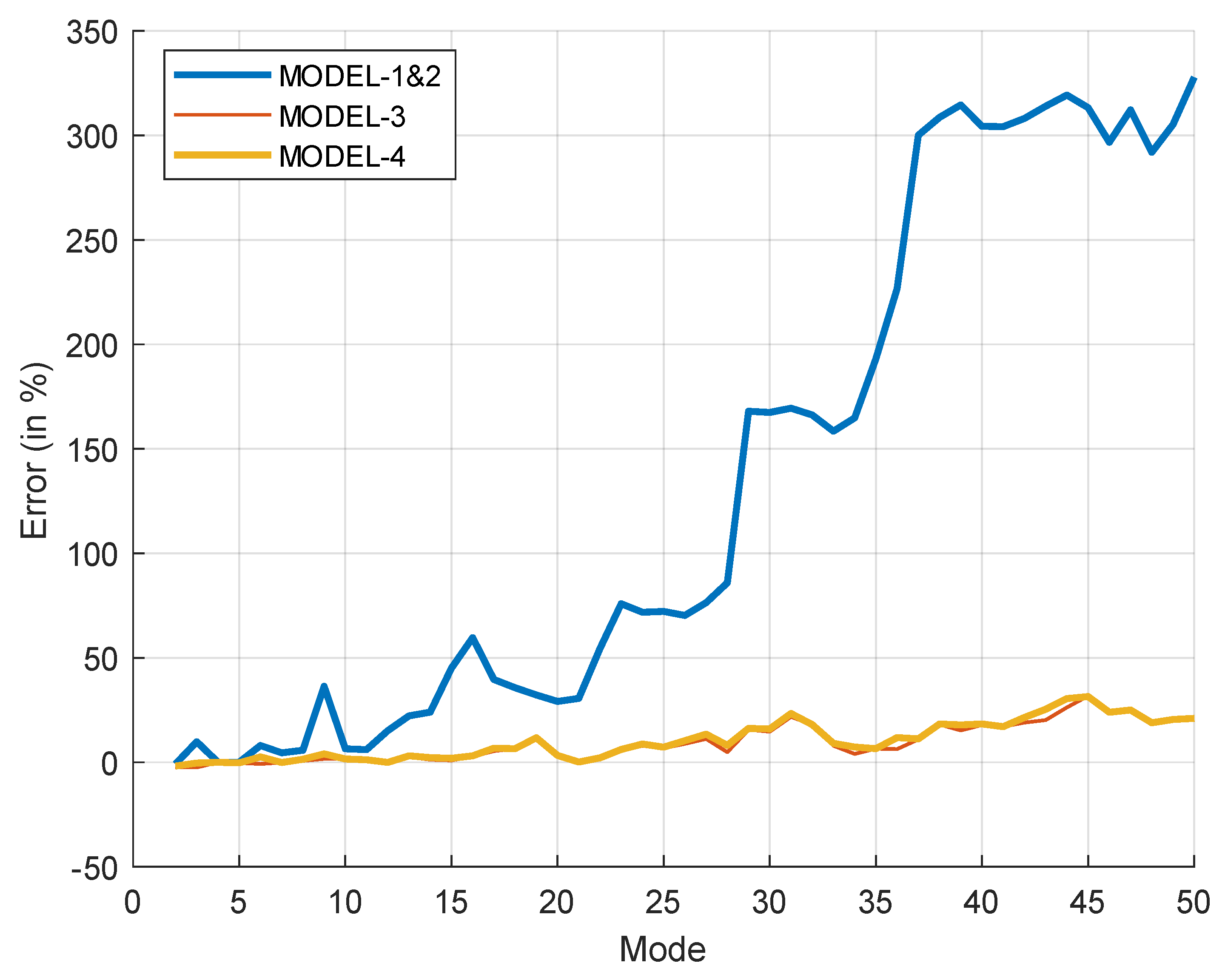

5.3. EXAMPLE 3: Annulus

5.3.1. T-Spline Model

5.3.2. Tensor-Product Model

5.4. EXAMPLE 4: Rectangular Acoustic Cavity

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Determination of Common Point in Neighbouring Patches

Appendix B: Control Points After the Subdivision

References

- Hughes, T.J.R.; Cottrell, J.A.; Bazilevs, Y. Isogeometric analysis: CAD, finite elements, NURBS, exact geometry and mesh refinement. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194, 4135–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazilevs, Y.; Calo, V.; Cottrell, J.; Evans, J.; Hughes, T.J.R.; Lipton, S.; Scott, M.; Sederberg, T.W. Isogeometric analysis using T-splines. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2010, 199, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, M.J.; Scott, M.A.; Evans, J.A.; Hughes, T.J.R. Isogeometric finite element data structures based on Bézier extraction of NURBS. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2011, 87, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.A.; Borden, M.J.; Verhoosel, C.V.; Sederberg, T.W; Hughes, T.J.R. Isogeometric finite element data structures based on Bézier extraction of T-splines. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2011, 88, 126–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G. The numerical evaluation of B-splines. J Inst Math Its Appl 1972, 10, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boor, C. On calculating with B-splines. J Approx Theory 1972, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegl, L.; Tiller, W. The NURBS Book. Springer, Berlin, Germany, 1997.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Control point removal algorithm for T-spline surfaces, In: M.-S. Kim and K. Shimada (Eds.): GMP 2006, LNCS 4077, Springer, pp. 385-396, 2006.

- Wang, A.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Du, X.; Xiao, F.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, G. Linear Independence of T-Spline Blending Functions of Degree One for Isogeometric Analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyche, T.; Mørken, K. Making the Oslo Algorithm More Efficient. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 1986, 23, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.A. T-splines as a Design-Through-Analysis Technology, Dissertation (PhD thesis), The University of Texas at Austin, August 2011.

- Courant, R.; Hilbert, D. (1966). Methods of mathematical physics, (1st English ed., Vol. I). InterScience: New York, USA (translated and revised from the German original), 1966, pp. 300–304.

- Eisenträger, S.; Eisenträger, J.; Gravenkamp, H.; Provatidis, C.G. High order transition elements: The xNy-element concept, Part II: Dynamics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 387, 114145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provatidis, C.G. Non-rational and rational transfinite interpolation using Bernstein polynomials. International Journal of Computational Geometry and Applications, 2022; 32, 55–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Wang, W.; Zhao, G.; Du, X.; Zang, R.; Yang, J. T-Splines for Isogeometric Analysis of the Large Deformation of Elastoplastic Kirchhoff–Love Shells. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control points in MODEL-3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Type B | Type C | TOTAL (nQ) |

| 4 × 4 | 14 × 6 | 16 × 9 | 244 |

| L2-norm in percent (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

MODEL-1 (57 DOF) |

MODEL-2 (57 DOF) |

MODEL-3 (247 DOF) |

MODEL-4 (256 DOF) |

| 0.0058 | 0.0058 | 0.0098 | 0.0016 |

| L2-norm in percent (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

MODEL 1 (49 DOF) |

MODEL 2 (49 DOF) |

MODEL 3 (169 DOF) |

MODEL 4 (169 DOF) |

| 1.0785935e-03 | 1.0785935e-03 | 5.2938191e-04 | 5.2938191e-04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).