1. Introduction

Speech synthesis has become integral to modern digital life, from virtual assistants to audiobooks and navigation systems. Human speech is inherently colorful, with different prosodic patterns carrying distinct pragmatic meanings that profoundly influence listener impressions [

1,

2]. Klüber et al. [

3] recently proposed that prosodic elements can significantly enhance the attribution of humanlike experience to artificial agents, raising questions about whether established prosodic mechanisms operate equivalently in AI-generated voices. For example, when stating “The economic outlook appears stable,” human speakers could use confident prosody (firm tone, steady pace) to elicit greater listener trust than those using doubtful prosody (hesitant tone, variable pace) [

4,

5]. However, when AI delivers this statement with varying prosody, it remains unclear whether listeners respond similarly or if perceived artificiality reduces the impact of prosodic cues. The current study examines the cognitive mechanisms listeners employ when processing prosodic information from artificial vs. human sources, investigating whether AI-generated prosody achieves functional equivalence to human vocal expression.

1.1. AI Voice Disadvantage Stems from Prosodic Limitations and Categorical Expectations of Reduced Social Competence

Available evidence suggests that differential perceptions between AI and human voices reflect both the prosodic advantages of human speech and listeners’ categorical expectations regarding artificial vs. human sources. On the one hand, the disadvantage of AI voices may stem from the superior prosodic elements of human voices. For example, in a narrative advertising listening task where participants heard the same story read by either a human or a synthetic voice, human voices led to higher perceived communicative effectiveness (clarity, persuasiveness), greater self-reported attention, and better recall performance [

6]. So unsurprisingly, Kühne et al. [

7] demonstrated that human voices received were rated more favorably across nine dimensions, including trustworthiness, naturalness, and likability, a finding that echoes across human-computer interaction contexts [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]

On the other hand, listener expectations and categorical knowledge also influence such preconceptions: when listeners know the source is artificial, the preference gap between human and synthetic voices becomes less pronounced [

11]. Further examining these preconceptions, if AI speakers are perceived as parallel yet socially less competent entities, this categorization provides a core explanation for two patterns: a) listeners predominantly prefer human voices as documented above, yet b) AI voices are favored in specific scenarios such as functional tasks [

14], technical contexts requiring consistency [

15], and long-form content [

16]. These patterns suggest that AI-human voice perception operates through in-group/out-group categorization mechanisms similar to accent-based social perception, where listeners distinguish between their in-group (one’s own social category, such as native accents or human speakers) and out-group (external categories, such as foreign accents [

17] or AI voices [

18,

19]), with in-group members generally preferred (pattern a). However, AI-human categorization uniquely involves functional role expectations (pattern b): despite out-group status, AI voices are deemed appropriate for specific utilitarian contexts (e.g., voice-guided navigation) where human voices would seem incongruous.

Current neuroimaging evidence suggests that this in-group/out-group distinction is rooted in the reduced humanness of AI voices compared to human voices. Roswandowitz et al. [

20] found that the nucleus accumbens shows evolved sensitivity to authentic human voices while AI voices trigger compensatory auditory cortex activation; Di Cesare et al. [

21] found that the dorso-central insula selectively activates for human emotional speech with communicative intent but not for robotic or non-social human voices; and Tamura et al. [

22] found that the left posterior insula responds more strongly to human than artificial voices despite similar acoustic properties. The fact that different brain regions/networks are activated by human versus AI voices collectively suggests that human-AI voice distinctions are rooted in differences in social-emotional processing rather than basic acoustic perception.

1.2. Listeners Apply Human Voice Perception Mechanisms when Processing AI Voices

Despite the above perceptual differences and categorical processing patterns, available evidence also suggests that AI and human speech perception share substantial latent dimensional structures underlying social-cognitive and perceptual processing. Y. Li et al. [

23], based on a study of 2,187 participants, suggest that warmth and competence are the two most prominent factors affecting trust in AI, which corresponds with the general social impression formation framework of warmth (intentional benevolence) and competence (capability to enact intentions) [

24]. Likewise, just as valence and dominance have been identified as the two core dimensions guiding human voice perception [

25], these same two dimensions emerge when rating synthetic voices on 17 social traits, suggesting a similar perceptual pattern [

26].

Even with early speech synthesis technology (e.g., 2003), male voices were perceived as more powerful than female voices, with this power perception pattern occurring similarly across both human and synthetic speech [

27]. Similar to accent-based in-group preferences in human speech perception, people rate healthcare robots with local-accented synthetic speech more positively than those with foreign-accented speech [

28]. Similarly, just as older human voices are typically associated with wisdom, students rated older-sounding AI-synthesized instructor voices as more credible [

29]. These convergent patterns of similar social impression formation across human and AI voices support the Computers Are Social Actors framework, which suggests that people unconsciously apply social rules meant for humans to technology [

30].

1.3. The Present Study

The above evidence presents two contrasting perspectives. Rather than a simple binary distinction, it appears that listeners categorize AI voices as an out-group while simultaneously building their perceptions on cognitive frameworks developed for human speech processing. This leads to a question about the relative influence of prosodic mechanisms vs. categorical group distinctions in voice perception. To better understand this question, we draw insights from research on listener expectations in accent-based perception. Research shows that speaker accent modulates the processing of social-emotional speech. For instance, listeners attend more deeply to prosodic politeness cues from native speakers [

31], perceive criticisms as less hurtful when delivered in a foreign accent [

32], and engage different neural mechanisms when processing complaints and fact/intention statements from in-group versus out-group speakers [

33,

34].

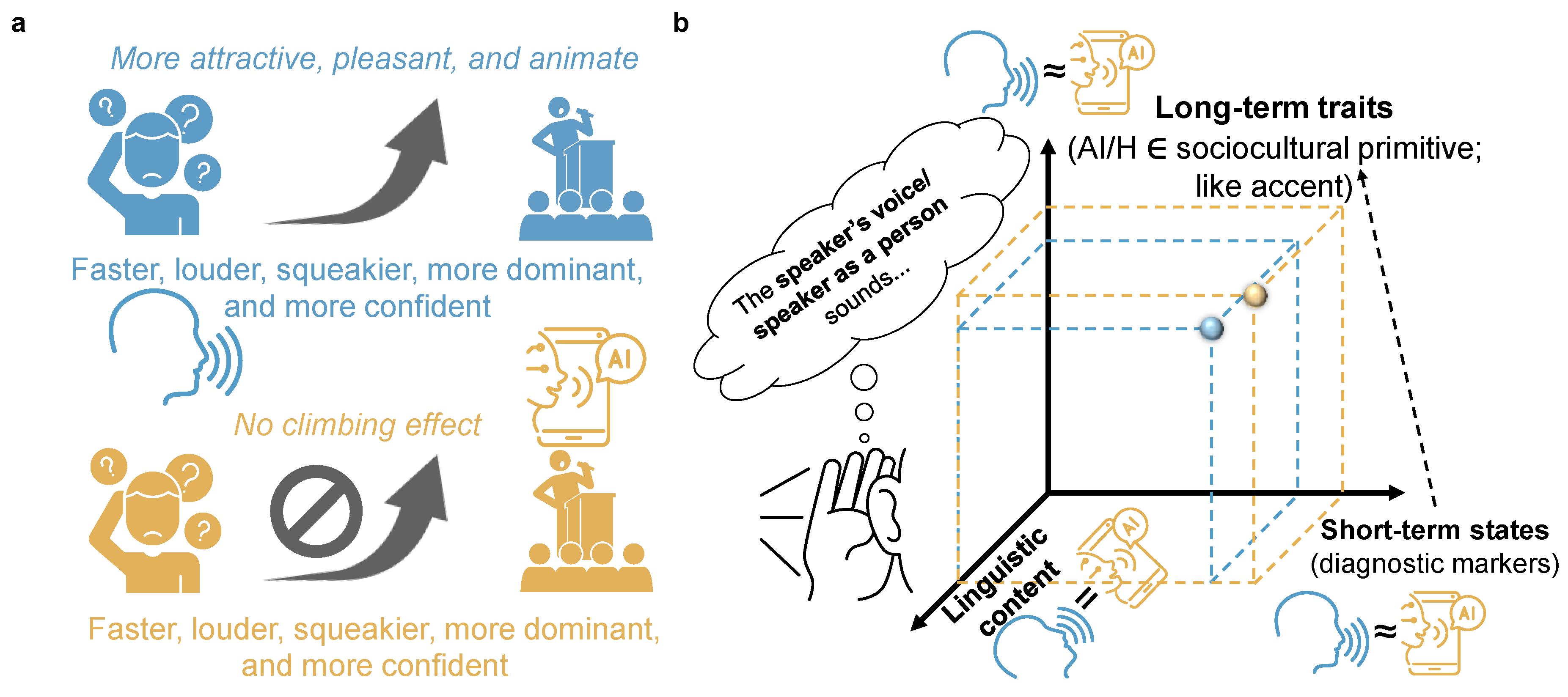

Similarly, we propose that categorical expectations drive listeners’ perception of AI versus human voices. Specifically, listeners may expect AI to lack social-emotional competence. If this expectation-driven processing holds, listeners’ social perception of AI-generated utterances would be fundamentally constrained by their categorical recognition of the voice source. Consequently, even when AI voices exhibit prosodic expressiveness comparable to human speech (e.g., producing statements with equally “colorful” prosodic variations), these cues may fail to achieve equivalent social-emotional impact. The present study aims to test this hypothesis. If supported, these findings would position AI-human voice distinctions alongside accent-based distinctions as sociocultural cues representing long-term traits (stable characteristics), within the theoretical framework of paralinguistic processing [

35]. Meanwhile, a notable background is that AI voices can now produce prosodic patterns comparable to human speech [

36,

37,

38], meaning that short-term states comprising prosodic features (dynamic characteristics) are present in both AI and human voices.

To test whether categorical expectations constrain prosodic influences on AI voice perception, we require a design that 1) collects listeners’ acoustic and social perceptions of AI versus human voices across dimensions [

27], 2) directly measures how prosody differentially influences these perceptions across voice sources [

39], and 3) examines whether perceptions organize along latent dimensional structures similar to those identified in previous PCA-based voice rating studies [

25].

We hence assessed listeners’ responses to 2 (voice sources: AI/human sharing speaker identity) × 2 (prosodic states: confident/doubtful) audio stimuli across 16 perceptual dimensions. These dimensions encompass those already showing documented human advantages [

7], those established with early synthesis technology two decades ago [

27], and those suggested as relevant but not directly tested in human-AI contexts (e.g., attractiveness [

13], friendliness [

14], dominance[

26]). These dimensions include speech quality-related cues, such as loudness, pitch, speaking rate, nasality, monotony [

27], accent [

28], and naturalness [

40,

41]. Explicit social inferences that require holistic evaluation of the voice were collected, including emotion richness, animateness [

40], confidence level [

4,

42], attractiveness [

43], pleasantness [

44], humanlikeness [

40], dominance [

45], trustworthiness [

45], and friendliness [

44]. See

Table S1 for the original Chinese text and English translation.

Our rating experiment aimed to address two research questions. RQ1 examined whether AI-human perceptual differences replicate the human advantage observed in existing literature, particularly across social dimensions, and how AI and human voices differ in terms of perceived acoustic characteristics. RQ2 addressed the core theoretical advancement: whether prosodic influences on social perception observed in human voices operate with equivalent effectiveness in AI voices.

Theoretically, for RQ2, we tested two competing hypotheses: H1 (Short-term override long-term) posited that prosodic effects would dominate categorical voice source effects, with AI voices exhibiting prosodic sensitivity patterns similar to those of human voices. H2 (Long-term priority; i.e., categorical expectations constrain prosodic influences) predicted that AI vs. human voice source categories would constrain prosodic influence, resulting in weaker or absent prosodic effects on social judgments for AI voices compared to human voices.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A priori power analysis was conducted using G-Power 3.1 [

46] (paired-samples t-test, two-tailed, effect size

d = 0.5, α = 0.05, target power = 0.80), indicating that 34 participants would be required. In our study, forty-five native Chinese speakers participated in the rating study, among whom data from five participants were excluded due to incomplete participation, resulting in 40 valid participant data sets (20 males:

M = 24.6,

SD = 2.09 years; 20 females:

M = 22.3,

SD = 2.54 years). The mean years of education were

M = 18.6 (

SD = 1.79) for males and

M = 18.2 (

SD = 2.59) for females. None of the participants reported having a speech or hearing impairment or a psychiatric history. Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participants were compensated with 50 RMB/hour for their participation.

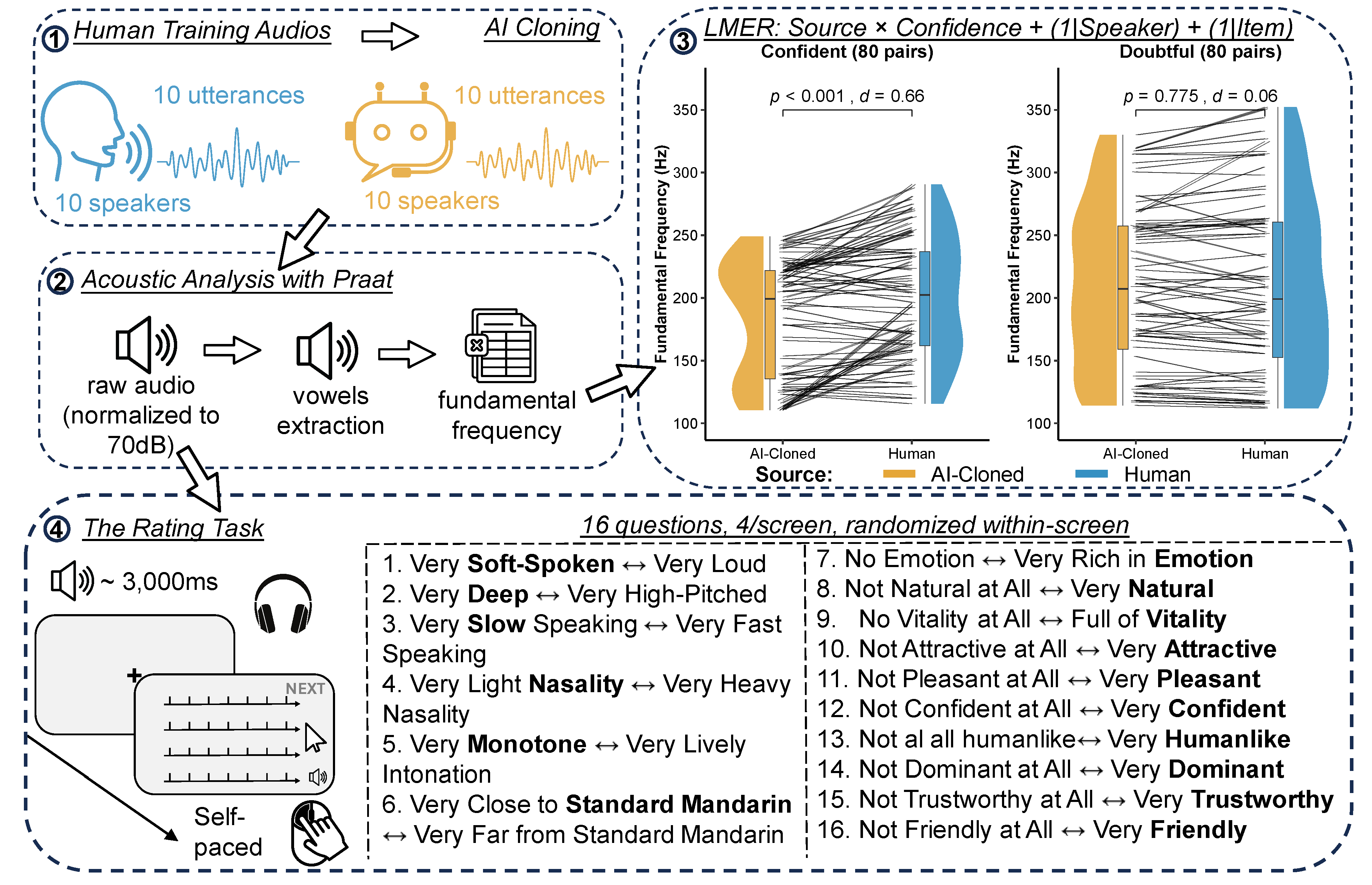

2.2. Voice Cloning and Stimulus Validation

Voice stimuli were created following procedures detailed in [

36], comprising both human speech and their corresponding AI-cloned counterparts generated using Huawei’s

Xiaoyi voice assistant. A total of 320 sentences were used: 2 confidence levels (confident vs. doubtful) × 2 speaker types (human vs. AI-cloned) × 8 speakers × 10 texts. The 10 texts included five geographical statements (

M = 12.2 ± 0.84 characters) and five trivia statements (

M = 11 ± 1 characters; see

Table S2). As shown in the third panel of

Figure 1, we compared the fundamental frequency (F0) extracted from sentences under confident vs. doubtful conditions. F0 extraction was performed using

Praat Vocal Toolkit [

47], using openly available batch processing code [

37]. The connecting lines illustrate paired comparisons between human and AI versions of F0 for the same speaker producing the same sentence. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between AI-cloned and human-produced sentences under doubtful conditions (

t = -0.286,

df = 300.0,

p = .775,

d = 0.06). However, significant differences emerged under confident conditions (

t = -5.492,

df = 300.0,

p < .001,

d = 0.66), with human voices exhibiting higher F0 than their AI-cloned counterparts.

2.3. Procedures

Participants wore Bose QuietComfort QS45 noise-cancelling headphones and sat comfortably in front of a computer screen. Before the experiment began, participants were asked to adjust the volume to a comfortable level. The experiment was programmed and conducted using

PsychoPy v2022.2.5 [

48]. The 16 rating scales were divided into four groups of four scales, with each group displayed on a separate screen. Participants heard an audio clip and saw four scales on a screen, with the option to replay the audio clip by pressing the play icon. Each audio clip was presented across four screens, with questions fully randomized in sequence within each screen across trials. The four screens maintained fixed content and sequence, with earlier screens focusing on speech quality dimensions and later screens targeting social impression measures. Participants registered their impressions using 7-point Likert scales via mouse clicks (see

Figure 1).

The experiment consisted of four blocks (78 trials each), totaling 320 sentence ratings. Participants completed two blocks per laboratory visit, with a recommended 10-minute break between blocks (though actual break duration varied based on participant needs). Each block lasted approximately 60-90 minutes, with variability due to individual pacing. Block sequence was counterbalanced using a Latin square design to control for order effects.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Pre-Processing

The collected rating data comprised 12,960 observations from 40 participants across 16 perceptual dimensions. Data quality assessment revealed that 32 of 40 participants had missing values in their responses, with missing data concentrated in four speech quality dimensions: loudness (145 missing values), squeakiness (143 missing values), speed (133 missing values), and nasality (160 missing values). Despite affecting the majority of participants, these missing values represented only 0.28% of total ratings. Given the minimal proportion of missing data, listwise deletion was applied to remove cases with incomplete ratings, resulting in a final dataset of 12,749 observations (a 98.4% retention rate).

2.4.2. t-Tests Comparing Human-AI Rating Differences

Independent samples t-tests compared AI and human voices across all 16 perceptual dimensions using R version 4.4.0 [

49]. Statistical analyses were conducted using base R’s t.test() function. For each dimension, t-tests followed the formula: t.test(rating ~ source). To control for multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction was applied with an adjusted significance threshold of

p < 0.003125 (0.05/16 dimensions). Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d with pooled standard deviation. Mean differences were calculated as the difference between Human and AI ratings, with positive values indicating human voice advantages. Results were visualized showing mean differences ordered by effect size magnitude, with statistical annotations (Bonferroni-corrected p-values and Cohen’s d) for each dimension. See

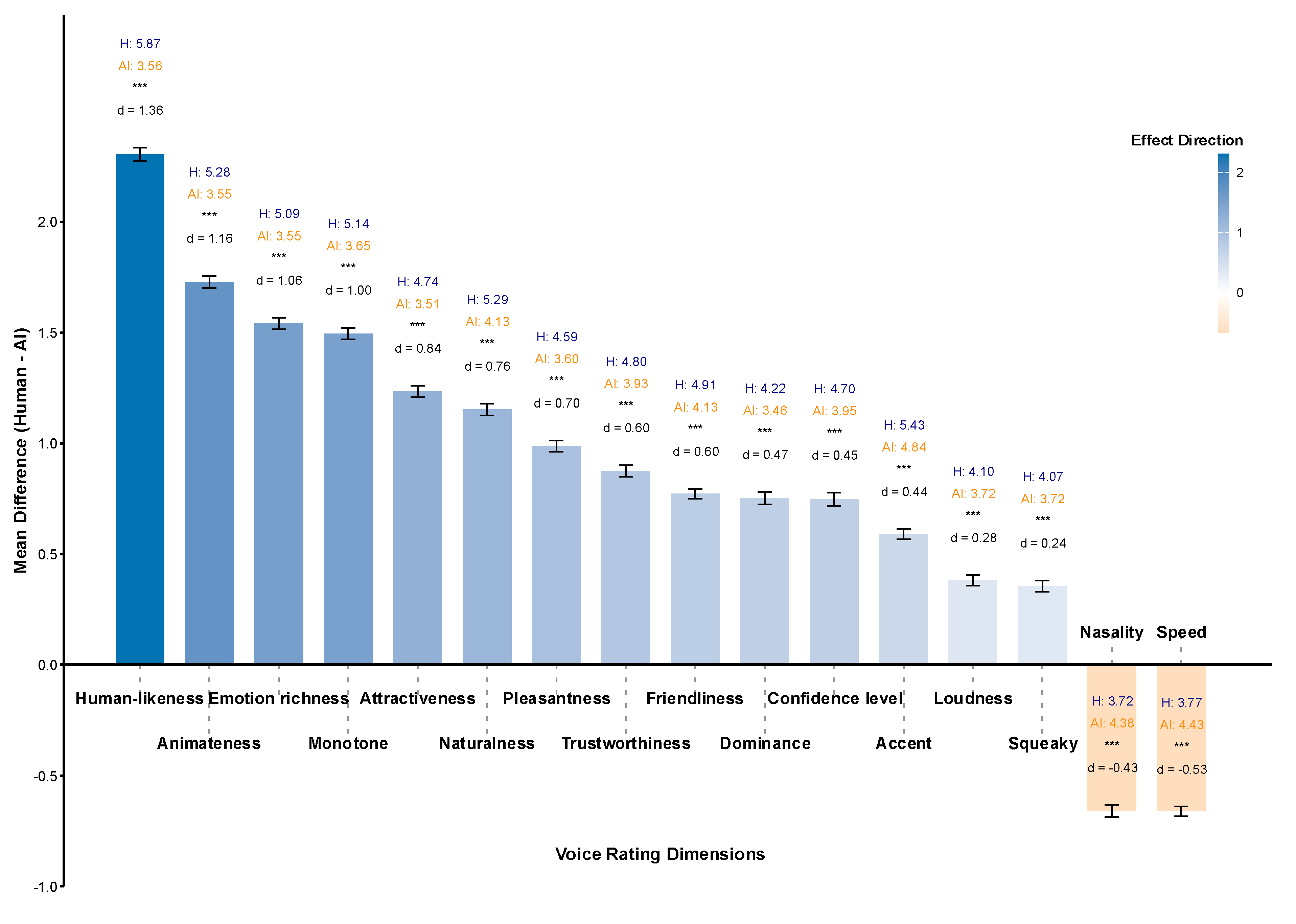

Figure 2.

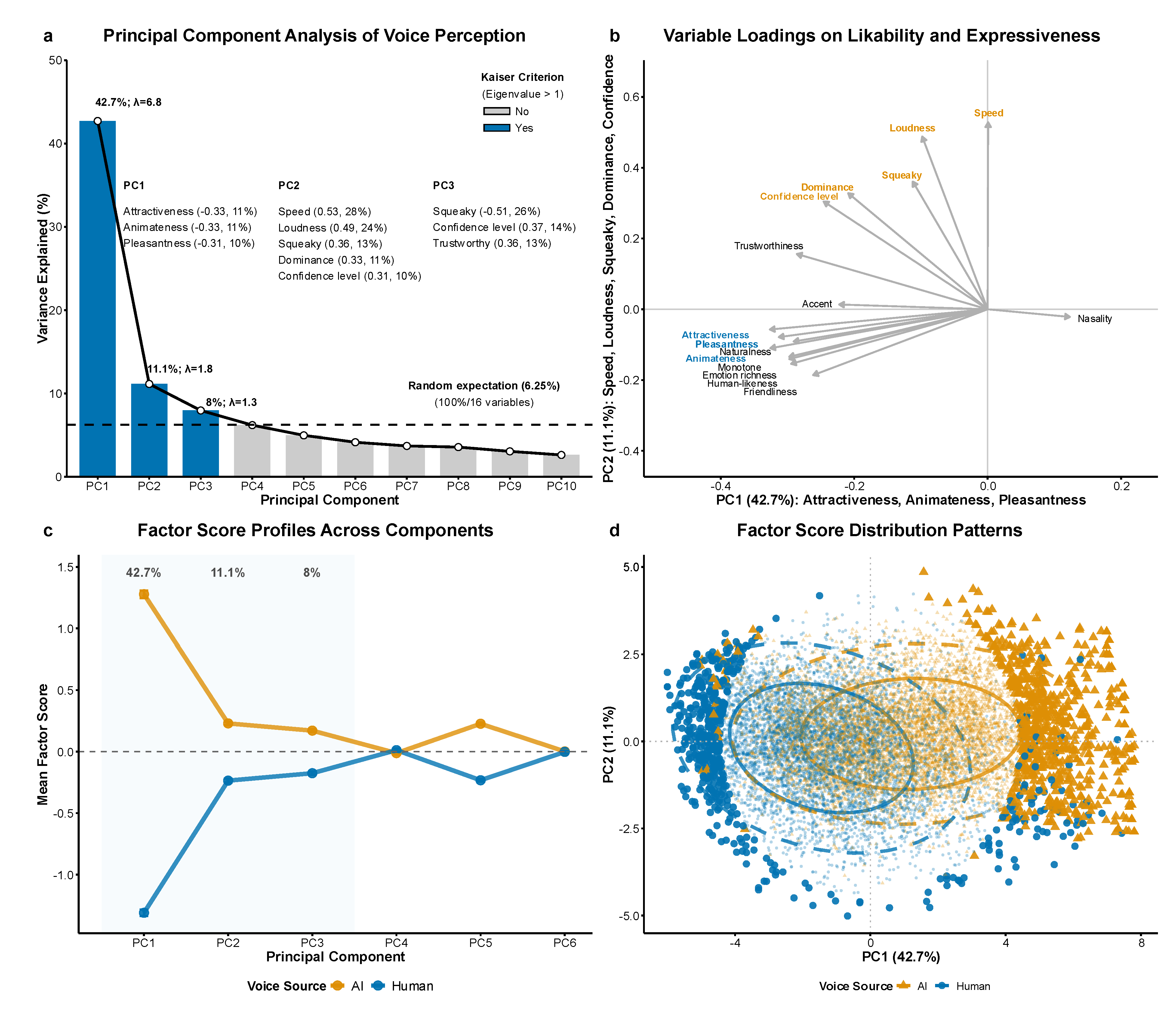

2.4.3. Principal Component Analysis of AI-Human Voice Perception Differences

To address the dimensional structure underlying voice perception and reduce the complexity of the 16 rating dimensions, we conducted principal component analysis (PCA) using R’s prcomp() function (R version 4.4.0) on standardized variables (scale = TRUE, center = TRUE). Component extraction employed Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue > 1.0) combined with scree plot examination (

Figure 3a) to determine the optimal number of components to retain. Variables with absolute loadings ≥ 0.30 were considered meaningful contributors to each component, with loading patterns visualized in biplot format (

Figure 3b). Component scores were compared between AI and human voices using independent samples t-tests with Bonferroni correction (

p < 0.017 for three components) and effect sizes calculated using Cohen’s

d with pooled standard deviation, following Cohen’s guidelines where |

d| = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 represent small, medium, and large effects [

50], respectively (

Figure 3c). Hotelling’s T

2 test assessed overall multivariate differences between voice source groups in the principal component space, with results displayed as confidence ellipses in the factor score distribution plot (

Figure 3d).

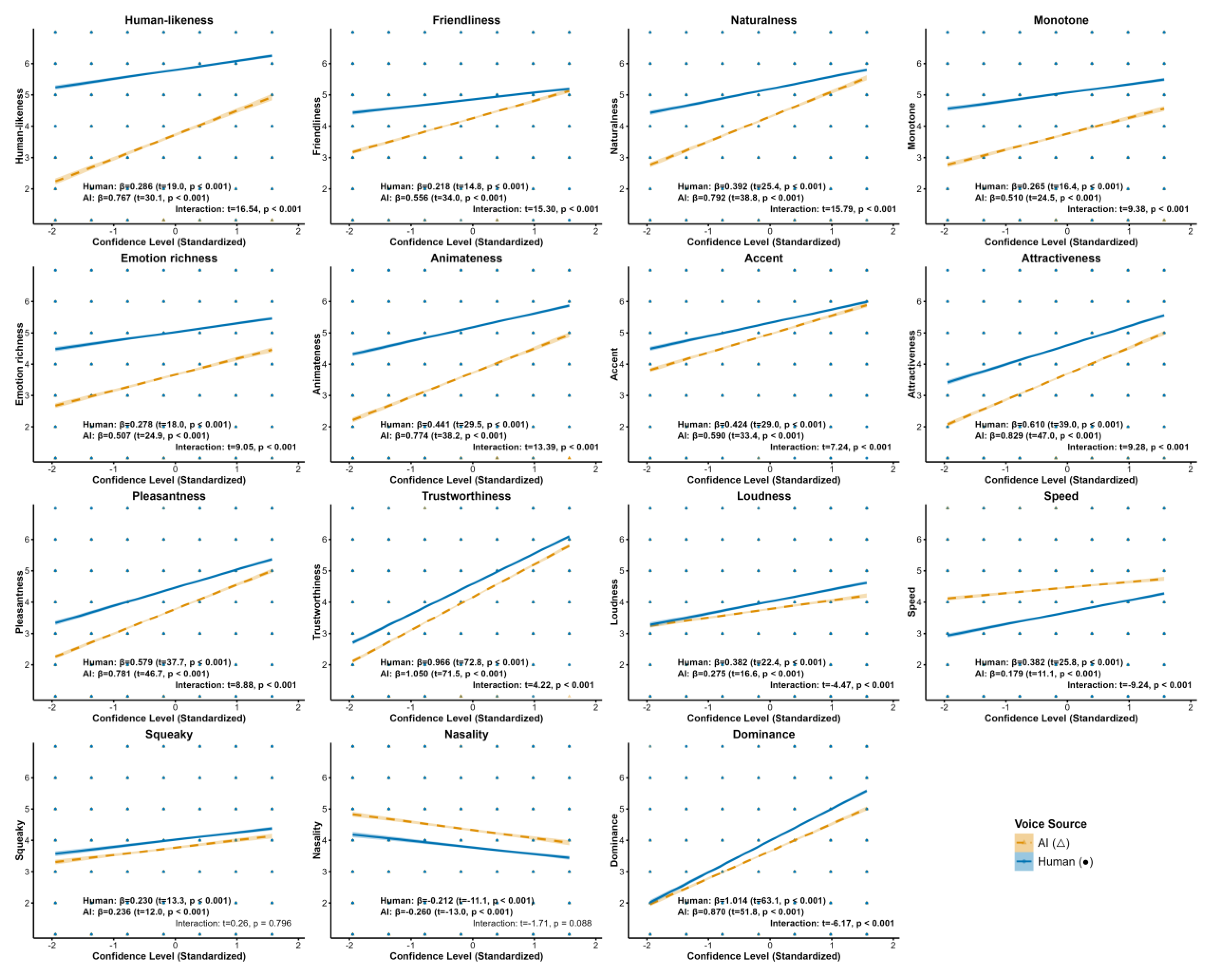

2.4.4. Moderation Analysis

To examine how confidence level affects voice perception and whether these effects differ between AI and human voices, we conducted regression-based moderation analysis using R version 4.4.2 [

49]. For each of the 15 perceptual dimensions (excluding confidence_level), we fitted three models: (1) simple linear regression within human voices: dimension ~ confidence_std, (2) simple linear regression within AI voices: dimension ~ confidence_std, and (3) full interaction model: dimension ~ source_binary × confidence_std, where source_binary (0 = Human, 1 = AI) and confidence_std represent standardized confidence ratings. This approach yielded 45 statistical tests (15 dimensions × 3 effects per dimension), requiring Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (α = 0.05/45 = 0.001111). Effect sizes were quantified using standardized regression coefficients (

β) and slope ratios (AI slope / Human slope) to examine whether the influence of prosodic confidence on perceptual ratings differs between AI and human voices. See

Figure 4.

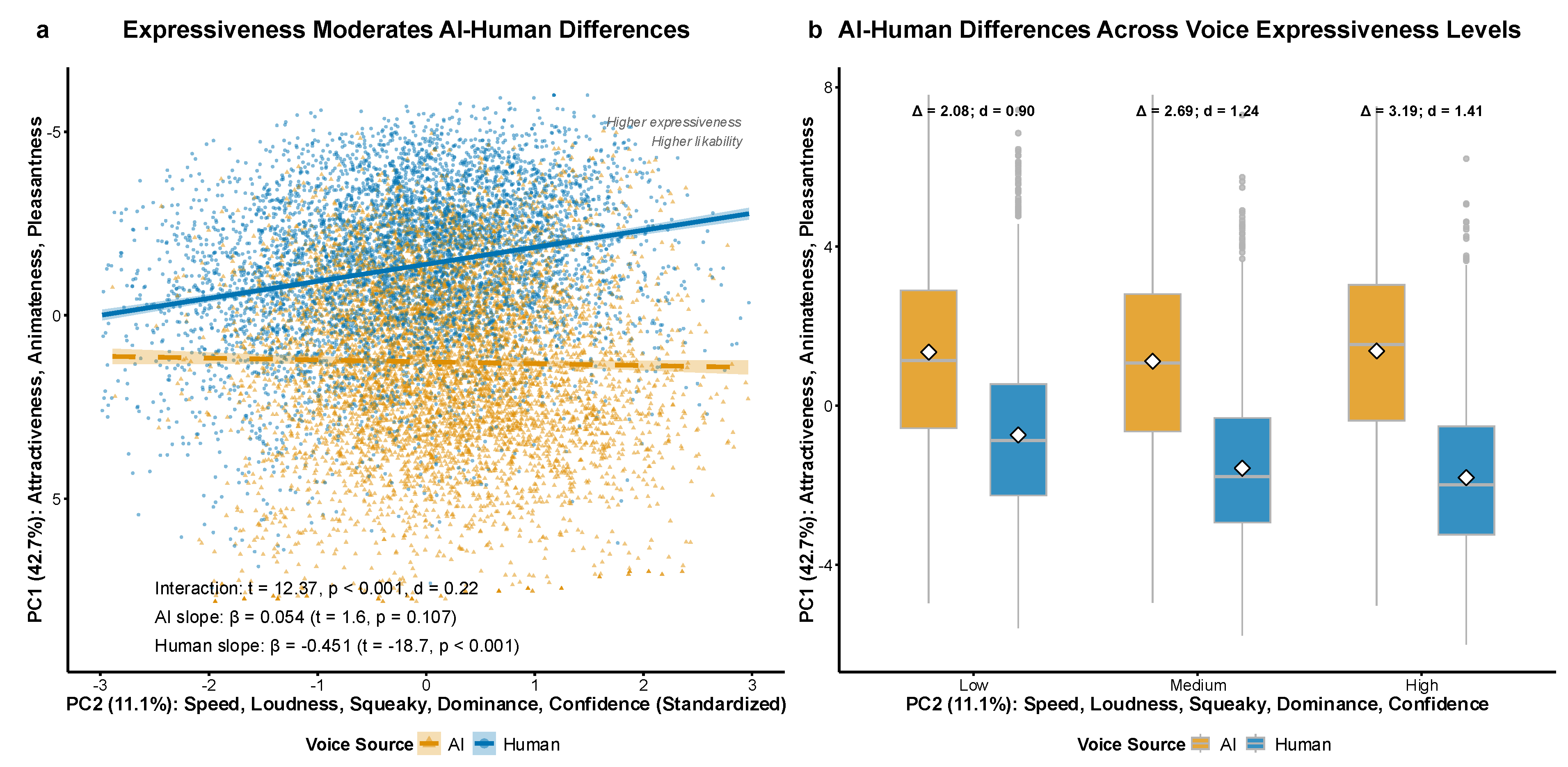

2.4.5. Moderation Analysis Between the Previously Identified Two Primary Principal Components

To examine whether PC2 moderates the relationship between voice source and PC1, we conducted a moderation analysis using multiple linear regression. PC2 scores were standardized (

M = 0,

SD = 1) and voice source was effect-coded (AI = 1, Human = 0). The moderation model followed the formula: PC1 ~ source × PC2_standardized, testing the interaction between voice source and PC2 (

Figure 5a). To probe significant interactions, we conducted conditional effects analysis by dividing PC2 into terciles (Low, Medium, High) and calculating AI-Human differences in PC1 within each level using independent samples t-tests with Cohen’s d effect sizes (

Figure 5b). Simple slopes analysis examined the relationship between PC2 and PC1 separately for AI and human voices to determine the direction and significance of PC2 effects within each voice source group.

3. Results

3.1. More Positive Ratings for Human Over AI Voices (t-Test Analysis)

The results of independent samples t-tests with Bonferroni correction are presented in

Figure 2 and

Table S3. The largest differences were observed for explicit social inferences that require holistic evaluation of the voice, including humanlikeness (

d = 1.36), animateness (

d = 1.16), emotion richness (

d = 1.06), attractiveness (

d = 0.84), pleasantness (

d = 0.70), friendliness and trustworthiness (both

d = 0.60), dominance (

d = 0.47), and confidence level (

d = 0.45). Human voices also received higher ratings on speech quality-related lower-level cues, including monotone (

d = 1.00), naturalness (

d = 0.76), accent (

d = 0.44), loudness (

d = 0.28), and squeakiness (

d = 0.24). Conversely, AI voices received significantly higher ratings than human voices on two speech quality-related dimensions: speed (

d = -0.53) and nasality (

d = -0.43), indicating that AI voices were perceived as speaking faster and sounding more nasal than human voices.

3.2. Underlying Dimensional Structure of Voice Perception (PCA Analysis)

The t-test results showed significant perceptual differences between AI and human voices across individual dimensions. PCA was conducted to understand the underlying structure organizing these differences. The analysis revealed that voice perception is organized along two primary orthogonal dimensions of social preference and prosodic expressiveness, with AI and human voices occupying distinct regions in this reduced perceptual space.

The scree plot (

Figure 3a) identified three principal components that met the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues> 1), collectively explaining 61.8% of the total variance. PC1 accounted for 42.7% of the variance, with strong negative loadings on attractiveness (-0.33), animateness (-0.33), and pleasantness (-0.31). This indicates that higher PC1 scores correspond to lower ratings on these positive attributes. PC2 explained 11.1% of variance, characterized by positive loadings on speed (0.53), loudness (0.49), squeakiness (0.36), dominance (0.33), and confidence level (0.31). PC3 explained an additional 8.0% of variance with mixed loadings that partially overlap the PC2 expressiveness dimension, indicating it likely captures residual prosodic variance not fully explained by the primary two-factor structure.

The variable loadings plot (

Figure 3b) revealed distinct clustering patterns: dimensions related to expressiveness (highlighted in orange) clustered in the first quadrant with positive loadings on PC2, representing short-term prosodic cues, including speed, loudness, squeakiness, and confidence level. Dominance also loaded positively on this component, likely because more confident-sounding voices elicited impressions of greater dominance [

51]. In contrast, social preference dimensions (highlighted in blue) clustered in the third quadrant, with negative loadings on both components, including attractiveness, pleasantness, animateness, naturalness, and other variables that reflect listeners’ social judgments of the voices. This pattern indicates that prosodic expressiveness and social preference represent orthogonal dimensions of voice perception.

Factor score profiles (

Figure 3c) showed significant group differences across three of the six components (PC1, PC2, and PC3; all

p < .001). The largest difference occurred in PC1, where AI voices scored significantly higher than human voices (Cohen’s

d = 1.14, large effect), indicating that AI voices were perceived as less attractive, animate, and pleasant. Medium to small effects were observed in PC2 (

d = 0.35) and PC3 (

d = 0.31). This pattern demonstrates that the primary distinction between AI and human voices lies in the social preference dimension (PC1), with secondary differences in prosodic expressiveness (PC2).

The bivariate distribution plot (

Figure 3d) demonstrated clear separation between AI and human voice clusters in the PC1-PC2 space, with AI voices centred at higher PC1 values (mean = 1.28) and human voices at lower PC1 values (mean = -1.31). The 68% and 95% confidence ellipses showed minimal overlap between groups, with AI voices distributed more variably in PC1 (S

D = 2.45) compared to human voices (S

D = 2.07). Extreme cases (90th percentile) comprised 11.7% of AI voices and 8.2% of human voices, indicating that AI voices showed greater perceptual variability. Multivariate analysis confirmed significant overall group differences (Hotelling’s T

2 = 2421.88,

p < .001), indicating that AI and human voices occupy distinct regions in this reduced perceptual space.

3.3. AI Voices Benefit More from Confident Prosody (Voice Source × Confidence Interaction)

To examine confidence effects across voice sources, we fitted three regression models for each dimension: human-only, AI-only, and interaction models (

Figure 4 and

Table S4). Results revealed universal prosodic benefits, with AI voices showing greater enhancement from confident prosody than human voices, particularly in social dimensions.

Regression analysis examining the effects of confidence level revealed that all 15 perceptual dimensions showed significant confident vs. doubtful prosody effects for human voices (15/15 surviving the Bonferroni correction). Specifically, confident compared to doubtful prosody significantly enhanced human voice ratings across social dimensions including humanlikeness (

β = 0.278), friendliness (

β = 0.213), naturalness (

β = 0.388), emotion richness (

β = 0.272), animateness (

β = 0.434), attractiveness (

β = 0.607), pleasantness (

β = 0.575), trustworthiness (

β = 0.966), and dominance (

β = 1.016), as well as speech quality dimensions including accent (

β = 0.423), loudness (

β = 0.380), speed (

β = 0.380), squeakiness (

β = 0.228), monotone (

β = 0.258), and nasality (

β = -0.211). These findings confirm that prosody as short-term state information effectively modulates human voice perception [

52,

53].

Similar robust prosodic effects were observed for AI voices, with confident vs. doubtful prosody significantly affecting all 15 perceptual dimensions (15/15 surviving Bonferroni correction). Confident prosody enhanced AI voice ratings across social dimensions including humanlikeness (β = 0.766), friendliness (β = 0.556), naturalness (β = 0.795), emotion richness (β = 0.506), animateness (β = 0.773), attractiveness (β = 0.832), pleasantness (β = 0.782), trustworthiness (β = 1.054), and dominance (β = 0.881), as well as speech quality dimensions including accent (β = 0.594), loudness (β = 0.276), speed (β = 0.176), squeakiness (β = 0.234), monotone (β = 0.509), and nasality (β = -0.259).

Further analysis revealed that voice source × confidence interactions were significant for 13 of 15 dimensions, demonstrating that prosodic confidence affects AI and human voices differently. AI voices showed greater prosodic sensitivity, with slope ratios (AI coefficient/Human coefficient) exceeding 1.0 for 12 dimensions. The strongest AI advantages emerged in social perception domains, including humanlikeness (2.75×), friendliness (2.62×), naturalness (2.05×), monotony (1.97×), emotion richness (1.86×), and animateness (1.78×). Moderate AI advantages were observed for accent (1.41×), attractiveness (1.37×), pleasantness (1.36×), and nasality (1.23×), while trustworthiness (1.09×) and squeakiness (1.03×) showed minimal differences. Conversely, human voices demonstrated stronger prosodic sensitivity for speed (0.46×), loudness (0.73×), and dominance (0.87×), indicating that AI voices showed smaller perceptual differences between confident and doubtful prosody on these dimensions compared to human voices. These findings demonstrate that confident prosody provides greater perceptual enhancement for AI voices compared to human voices, especially across social dimensions.

3.4. Principal Component Moderation Further Reveals Categorical AI-Human Impression Formation

To examine whether prosodic effects (i.e., the influence of confident vs. doubtful prosody on perceptual ratings) also manifest in principal component space, we tested PC2 (vocal expressiveness) as a moderator of voice source effects on PC1 (social preference).

Figure 5a shows a significant voice source × PC2 interaction (

β = 0.505, t = 12.37,

p < 0.001). Human voices demonstrated a negative expressiveness-preference relationship (

β = -0.451, t = -18.72,

p < 0.001), while AI voices showed no significant relationship (

β = 0.054, t = 1.61,

p = 0.107).

Figure 5b reveals that AI-human differences increase with expressiveness levels: low (

d = 0.90), medium (

d = 1.24), and high expressiveness (

d = 1.41). This pattern suggests that while prosodic cues can modulate AI voice perception at individual dimensional levels, categorical voice source distinctions constrain processing at more fundamental perceptual levels. The absence of expressiveness effects for AI voices in principal component space indicates that listeners employ fundamentally different cognitive pathways for processing AI vs. human speech, with categorical boundaries remaining resilient even when prosodic features vary.

4. Discussion

Our study provides a direct comparison of human and AI voices across 16 perceptual dimensions, utilizing identical talker identities through voice cloning technology. For RQ1, we found systematic human voice advantages across social dimensions (humanlikeness, trustworthiness, attractiveness), replicating previous literature while revealing some contradictory findings in acoustic dimensions. For RQ2, our findings support H2 (long-term priority): while prosodic confidence enhanced individual dimensions for both voice sources, only human voices showed expressiveness-to-appeal mappings in overall social impressions, indicating that categorical voice source processing constrains prosodic benefits for AI voices. These results inform social robotics research by demonstrating that AI voice design must consider not only acoustic fidelity but also the fundamental categorical barriers that prevent prosodic expressiveness from translating into social appeal.

4.1. Human vs. AI Voices: Consistent Preferences, Small Contradictions, and Social Role Implications

We observed that human voices have advantages over AI voices across multiple dimensions. Findings that align with existing literature include: human voices were rated as more humanlike, trustworthy, confident, and pleasant [

7,

54]; more animate and emotionally rich [

40]; and less monotone [

27]. Meanwhile, previous research on AI voice perception has hinted at potential differences across several perceptual dimensions but did not provide direct human–AI comparisons. For example, listeners were shown to prefer more natural and attractive synthetic voices [

13]. Human advantages in friendliness were only indirectly suggested, since friendliness was embedded within broader warmth constructs without being measured as an independent trait [

14]. Dominance was identified as an important perceptual cue, strongly linked to pitch, but only within synthetic voices [

26]. Our rating experiment provides direct evidence that human voices receive significantly more favourable evaluations than AI voices across dimensions of naturalness, friendliness, dominance, and attractiveness. These findings replicate and extend previous literature, demonstrating that systematic preferences for human voices over AI voices persist across multiple perceptual dimensions. This suggests that HCI settings such as healthcare consultations [

55,

56] and educational applications [

57,

58] may need to take these considerations into account when designing AI avatars.

We also report findings that contradict previous literature: human voices were perceived as louder and squeakier than AI voices, contrary to Mullennix et al. [

27], who found no significant loudness differences and reported synthetic voices as squeakier. Several factors may explain these differences. Our study used Chinese Mandarin rather than English stimuli and employed modern voice cloning technology rather than traditional synthesis methods from two decades ago. Despite 70dB normalization in our study, human voices were still perceived as louder, suggesting categorical biases in human-AI voice perception rather than acoustic differences. The unexpected finding that human voices sounded squeakier may reflect the fact that naturally produced Mandarin contains more tonal variations and prosodic colour, while AI-generated sentences sound smoother and more stable, although this remains speculative. However, it should be noted that differences in these two dimensions were of a small effect size, warranting caution when accepting the existence of these differences.

Additionally, we replicated the established AI features in speed and nasality, with AI voices perceived as faster and more nasal than human voices, consistent with Mullennix et al. [

27]. This suggests that the perceived higher nasality and faster speech rate of AI voices represent consistent perceptual characteristics that persist across languages and over two decades of technological advancement, indicating that these dimensions may require specific attention in future AI speech development.

Contrary to Mullennix et al. [

27], who found human voices were rated as less accented than synthetic voices, our study showed that human voices were perceived as sounding less standard (carrying stronger regional accents diverging from standard Mandarin) than AI voices. This highlights the different social roles of human and AI speech: human voices convey social identity and cultural belonging through natural regional variation, whereas AI voices, with their standardized and accent-neutral qualities, are advantageous for education and broadcasting. Hence, AI voices can also be engineered to adopt specific dialects, which may foster intimacy and engagement in contexts such as livestream shopping or short-video platforms (e.g., the popularity of Shaanxi-accented voiceovers imitating actress Yan Ni’s voice from

My Own Swordsman on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok).

Beyond updating the understanding of the direct perceptual differences between AI and human voices, we also provide insights into the relative effectiveness of humanlikeness [

40], naturalness [

41], and animateness [

40]. Humanlikeness was the most effective discriminator between voice sources. This superior discriminative power likely reflects its conceptual directness: the scale contrasts “very machine-like” vs. “very humanlike,” directly targeting the fundamental AI-human distinction. In contrast, naturalness and animateness involve more abstract judgments that may be influenced by technological advances in speech synthesis. Future research examining categorical voice source perception may benefit from prioritizing humanlikeness as the primary measure, with naturalness and animateness serving as supplementary dimensions.

4.2. Categorical Processing Constrains Prosodic Benefits: AI Voices Lack Expressiveness-to-Appeal Mappings

Previous research found that both human [

25] and synthetic [

26] voice evaluations independently organize along valence and dominance dimensions, suggesting parallel perceptual structures across voice types. In the current study, we manipulated both group identity (AI vs. human) and prosodic states (confident vs. doubtful) to examine how these factors jointly structure voice perception. Our PCA revealed two key dimensions: social preference (PC1, capturing attractiveness, animateness, and pleasantness) and vocal expressiveness (PC2, capturing speed, loudness, squeakiness, confidence level, and dominance). The inclusion of dominance in the expressiveness dimension likely reflects that more confident-sounding voices inherently elicit greater dominance impressions [

51], as confident prosody involves acoustic features such as increased intensity and pitch variation that signal assertiveness and control. This two-component structure reveals the core perceptual dimensions listeners use when evaluating AI vs. human voices. We quantitatively demonstrate that social preference and vocal expressiveness operate as orthogonal dimensions, where expressiveness functions as diagnostic markers [

7,

12] for voice source detection while social preference [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] reflects distinct attitudes toward AI vs. human speakers.

Meanwhile, our findings regarding whether confident prosody leads to more positive ratings compared to doubtful prosody revealed an instance of Simpson’s Paradox between individual dimension and principal component analyses. Simpson’s paradox occurs when a trend that appears in several groups of data disappears or reverses when the groups are combined, often due to confounding variables or differences in group composition [

59,

60]. At the individual dimension level, our results showed that all 15 dimensions demonstrated significantly more positive ratings for confident vs. doubtful prosody, applying to both human and AI voices. Moreover, the human-AI interaction revealed that AI voices showed greater prosodic sensitivity than human voices across 13 of 15 dimensions, with particularly strong effects in social perception domains.

However, the principal component results revealed a different pattern. Only human voices demonstrated expressiveness-to-appeal mappings, where faster, louder, squeakier, more dominant, and more confident audio received more attractive, pleasant, and animate evaluations. These mappings were completely absent for AI voices, as shown in

Figure 6a. This paradox suggests that while prosodic confidence enhances individual perceptual dimensions for AI voices, these improvements do not translate into overall social preference gains in the integrated perceptual space. This pattern (the absence of expressiveness-to-appeal mappings in AI voice perception) provides strong evidence that, although individual dimension effects exist, consistent with the Computers Are Social Actors framework [

30], AI and human voices represent different social groups as per the Stereotype Content Model [

24]. The strong group-based influence (humans show expressiveness-to-appeal mappings while AI voices do not) may reflect that humanlikeness detection (naturalness being one form of humanlikeness assessment) occurs at early stages of voice object analysis, preceding the processing of social content carried by prosodic cues [

41], with this detection mechanism specifically distinguishing between AI and human voice sources.

Figure 6b illustrates the theoretical framework underlying these findings. While AI and human voices deliver identical linguistic content (what is said), they differ in how prosodic short-term states (how things are said) [

61] reveal categorical information about voice source (who is saying it) [

62]. Although we controlled talker identity through voice cloning technology, sociocultural dimensions within long-term traits inevitably differ between AI and human voices. Specifically, AI-human differences manifest in sociocultural primitives [

35], such as accent-like categorical distinctions, which affect the perception of who is saying it. AI voices exhibit distinctive prosodic patterns, such as a faster speech rate and varying emotional richness, that function as diagnostic markers in short-term states, allowing listeners to detect the fundamental AI vs. human distinction in the “who” dimension. This categorical voice source information is then processed as a long-term trait, similar to accent-based social categorization. Despite controlling individual talker identity, listeners still perceived AI-human source differences as fixed sociocultural attributes, demonstrating accent-like categorical processing where voice source becomes an invariant social category [

63,

64] that constrains how prosodic variations are interpreted and integrated into overall social impressions [

34,

39].

This reasoning regarding in-group vs. out-group social impressions, where AI-human differences create accent-like influences on listeners’ audio evaluations, also echoes identity discrimination results. Recent research shows that even with identical sentence content and controlled voice cloning, within-group identity matching (human-human, AI-AI) achieved ~99% accuracy while human-AI pairs showed only ~54% accuracy when prosody matched [

37]. This indicates that AI and human voices are not perceived as producing truly identical sentences (as represented by the dots in

Figure 6b). It is such an out-group perception of AI that enables listeners to categorically suppress prosody-impression mappings to a greater extent, which was not observed in our study for AI voices.

4.3. Limitations and Implications for Social Robotics

Our study employed Chinese Mandarin stimuli with university students, which limited the generalizability of our findings across languages and cultures. We used a single voice cloning technology (Huawei Cecelia), and results may vary with different synthesis approaches. Our stimuli were limited to factual statements with confident/doubtful prosody, and the controlled laboratory setting may not capture real-world human-robot interactions where contextual factors and extended exposure could influence voice perception. Additionally, perceptual ratings may not directly predict behavioural outcomes in actual human-robot collaboration.

Our experiment results suggest that technology users would maintain distinct expectations for AI systems, particularly regarding their lack of social-emotional authenticity. These insights have critical implications for voice assistant design and anthropomorphic embodied AI applications that incorporate facial expressions and humanoid forms. First, expectation alignment is crucial: designers should explicitly communicate the AI’s nature rather than attempting deception, while establishing appropriate boundaries for social-emotional interaction [

65,

66]. Second, multimodal consistency must be maintained: voice, facial expressions, and bodily movements should maintain coherent levels of artificiality to avoid uncanny valley effects [

67,

68]. Third, beyond serving informational roles [

14], AI voices must also convey interpersonal roles through prosodic features such as empathy [

69,

70,

71]. Our principal component results reveal that expressiveness-to-appeal mappings are absent for AI voices, suggesting listeners remain skeptical of AI emotional authenticity. Finally, interpersonal AI voices may benefit elderly users [

72,

73] but inadequately serve individuals with autism spectrum disorder who cannot perceive AI’s lack of humanlikeness [

40], risking over-reliance that impairs social skill development.

5. Conclusions

In human-to-human communication, the social-communicative goals achieved through expressive prosody are influenced by accent-based in-group versus out-group preferences [

34,

39]. Our findings suggest that AI-human distinctions function similarly to accent-based categorization, creating comparable in-group/out-group dynamics. Human voices benefit from expressive prosody, where faster, louder, squeakier, more dominant, and more confident voices are perceived as more attractive, pleasant, and animate. However, this expressiveness-to-appeal mapping is absent for AI voices, consistent with human voices receiving higher ratings across perceptual dimensions. These findings inform our understanding that listeners do not expect social-emotional authenticity from AI.

While some human-computer interaction scenarios involve purely informational roles where this expectation is appropriate, others require interpersonal engagement [

14,

69,

70,

71]. Our study adds that when AI systems are designed for interpersonal contexts requiring social capability, prosodic features can enhance individual dimension perceptions, yet categorical boundaries persist that prevent these enhancements from translating into overall social appeal unless AI becomes completely undetectable as non-human.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics committee. The ethical committee of the Institute of Language Sciences, Shanghai International Studies University, approved the experiment.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32471109), awarded to X. Jiang. The PhD studentship of W. Chen was supported by a McGill-CSC (China Scholarship Council) Joint Scholarship, part of which is sourced from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2022-04363) awarded to M. D. Pell.

Data Availability Statement

The code and data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework repository at

https://osf.io/qgrva/.

References

- Larrouy-Maestri P, Poeppel D, Pell MD (2025) The Sound of Emotional Prosody: Nearly 3 Decades of Research and Future Directions. Perspect Psychol Sci 20:623-638. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Pell MD (2024) Tracking dynamic social impressions from multidimensional voice representation. [CrossRef]

- Klüber K, Schwaiger K, Onnasch L (2025) Affect-Enhancing Speech Characteristics for Robotic Communication. Int J Soc Robot 17:315-333. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Pell MD (2017) The sound of confidence and doubt. Speech Commun 88:106-126. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Pell MD (2015) On how the brain decodes vocal cues about speaker confidence. Cortex 66:9-34. [CrossRef]

- Rodero E (2017) Effectiveness, attention, and recall of human and artificial voices in an advertising story. Prosody influence and functions of voices. Comput Hum Behav 77:336-346. [CrossRef]

- Kühne K, Fischer MH, Zhou Y (2020) The human takes it all: Humanlike synthesized voices are perceived as less eerie and more likable. evidence from a subjective ratings study. Front Neurorobot 14:593732. [CrossRef]

- Cuciniello M, Amorese T, Cordasco G, Marrone S, Marulli F, Cavallo F, et al. (2022) Identifying Synthetic Voices’ Qualities for Conversational Agents. Applied Intelligence and Informatics, Reggio Calabria, Italy, pp 333-346. [CrossRef]

- Noah B, Sethumadhavan A, Lovejoy J, Mondello D (2021) Public Perceptions Towards Synthetic Voice Technology. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet 65:1448-1452. [CrossRef]

- Seaborn K, Miyake NP, Pennefather P, Otake-Matsuura M (2021) Voice in human–agent interaction: A survey. ACM Comput Surv 54:1-43. [CrossRef]

- Stern SE, Mullennix JW, Yaroslavsky I (2006) Persuasion and social perception of human vs. synthetic voice across person as source and computer as source conditions. Int J Hum Comput Stud 64:43-52. [CrossRef]

- Rodero E, Lucas I (2023) Synthetic versus human voices in audiobooks: The human emotional intimacy effect. New Media Soc 25:1746-1764. [CrossRef]

- Romportl J (2014) Speech Synthesis and Uncanny Valley. Text, Speech and Dialogue, Brno, Czech Republic, pp 595-602. [CrossRef]

- Im H, Sung B, Lee G, Xian Kok KQ (2023) Let voice assistants sound like a machine: Voice and task type effects on perceived fluency, competence, and consumer attitude. Comput Hum Behav 145:107791. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman A, Richards D (2022) Is Natural Necessary? Human Voice versus Synthetic Voice for Intelligent Virtual Agents. Multimodal Technol Interact 6:51. [CrossRef]

- Cambre J, Colnago J, Maddock J, Tsai J, Kaye J (2020) Choice of Voices: A Large-Scale Evaluation of Text-to-Speech Voice Quality for Long-Form Content. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, pp 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Paladino MP, Mazzurega M (2020) One of Us: On the Role of Accent and Race in Real-Time In-Group Categorization. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 39:22-39. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Zhou X, Yang Q (2021) Designing medical artificial intelligence for in- and out-groups. Comput Hum Behav 124:106929. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Jiang X, Ge J, Shan S, Zou S, Ding Y (2024) Inconsistent prosodies more severely impair speaker discrimination of Artificial-Intelligence-cloned than human talkers. Proc. Speech Prosody 2024, Leiden, The Netherlands, pp 846-850. [CrossRef]

- Roswandowitz C, Kathiresan T, Pellegrino E, Dellwo V, Frühholz S (2024) Cortical-striatal brain network distinguishes deepfake from real speaker identity. Commun Biol 7:711. [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare G, Cuccio V, Marchi M, Sciutti A, Rizzolatti G (2022) Communicative and affective components in processing auditory vitality forms: An fMRI study. Cereb Cortex 32:909-918. [CrossRef]

- Tamura Y, Kuriki S, Nakano T (2015) Involvement of the left insula in the ecological validity of the human voice. Sci Rep 5:8799. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Baizhou W, Yuqi H, Jun L, Junhui W, and Luan S (2025) Warmth, Competence, and the Determinants of Trust in Artificial Intelligence: A Cross-Sectional Survey from China. Int J Hum Comput Interact 41:5024-5038. [CrossRef]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P (2008) Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 40:61-149. [CrossRef]

- McAleer P, Todorov A, Belin P (2014) How do you say ‘Hello’? Personality impressions from brief novel voices. PLoS One 9:e90779. [CrossRef]

- Shiramizu VKM, Lee AJ, Altenburg D, Feinberg DR, Jones BC (2022) The role of valence, dominance, and pitch in perceptions of artificial intelligence (AI) conversational agents’ voices. Sci Rep 12:22479. [CrossRef]

- Mullennix JW, Stern SE, Wilson SJ, Dyson C-l (2003) Social perception of male and female computer synthesized speech. Comput Hum Behav 19:407-424. [CrossRef]

- Tamagawa R, Watson CI, Kuo IH, MacDonald BA, Broadbent E (2011) The effects of synthesized voice accents on user perceptions of robots. Int J Soc Robot 3:253-262. [CrossRef]

- Edwards C, Edwards A, Stoll B, Lin X, Massey N (2019) Evaluations of an artificial intelligence instructor’s voice: Social Identity Theory in human-robot interactions. Comput Hum Behav 90:357-362. [CrossRef]

- Reeves B, Nass C (1996) The media equation: How people treat computers, television, and new media like real people. Cambridge, UK 10:19-36.

- Lam PCH, Cui H, Pell MD (2025) The influence of speaker accent on the neurocognitive processing of politeness. Brain Res 1865:149897. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Arriola ME, Bazzi L, Mauchand M, Foucart A, Pell MD (2025) Does criticism in a foreign accent hurt less? Lang Cogn Neurosci 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Mauchand M, Pell MD (2022) Listen to my feelings! How prosody and accent drive the empathic relevance of complaining speech. Neuropsychologia 175:108356. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Sanford R, Pell MD (2018) Neural architecture underlying person perception from in-group and out-group voices. NeuroImage 181:582-597. [CrossRef]

- Schuller B, Batliner A (2013) Computational paralinguistics: emotion, affect and personality in speech and language processing. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK.

- Chen W, Jiang X (2023) Voice-Cloning Artificial-Intelligence Speakers Can Also Mimic Human-Specific Vocal Expression. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Pell MD, Jiang X (2025) Prosodic cues strengthen human-AI voice boundaries: Listeners do not easily perceive human speakers and AI clones as the same person. [CrossRef]

- Cohn M, Predeck K, Sarian M, Zellou G (2021) Prosodic alignment toward emotionally expressive speech: Comparing human and Alexa model talkers. Speech Commun 135:66-75. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Gossack-Keenan K, Pell MD (2020) To believe or not to believe? How voice and accent information in speech alter listener impressions of trust. Q J Exp Psychol 73:55-79. [CrossRef]

- Kuriki S, Tamura Y, Igarashi M, Kato N, Nakano T (2016) Similar impressions of humanness for human and artificial singing voices in autism spectrum disorders. Cognition 153:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum C, Frühholz S, Schweinberger SR (2025) Understanding voice naturalness. Trends Cogn Sci 29:467-480. [CrossRef]

- Eyssel F, Hegel F (2012) (S)he’s got the look: Gender stereotyping of robots. J Appl Soc Psychol 42:2213-2230. [CrossRef]

- Sundar SS, Jung EH, Waddell TF, Kim KJ (2017) Cheery companions or serious assistants? Role and demeanor congruity as predictors of robot attraction and use intentions among senior citizens. Int J Hum Comput Stud 97:88-97. [CrossRef]

- Dou X, Wu C-F, Lin K-C, Gan S, Tseng T-M (2021) Effects of Different Types of Social Robot Voices on Affective Evaluations in Different Application Fields. Int J Soc Robot 13:615-628. [CrossRef]

- Law T, Chita-Tegmark M, Scheutz M (2021) The Interplay Between Emotional Intelligence, Trust, and Gender in Human–Robot Interaction. Int J Soc Robot 13:297-309. [CrossRef]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41:1149-1160. [CrossRef]

- Corretgé R (2024). Praat Vocal Toolkit.

- Peirce J, Gray JR, Simpson S, MacAskill M, Höchenberger R, Sogo H, et al. (2019) PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behav Res Methods 51:195-203. [CrossRef]

- R-Core-Team (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.3.3 ed.): R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Hodges-Simeon CR, Gaulin SJC, Puts DA (2010) Different Vocal Parameters Predict Perceptions of Dominance and Attractiveness. Human Nature 21:406-427. [CrossRef]

- Goupil L, Ponsot E, Richardson D, Reyes G, Aucouturier J-J (2021) Listeners’ perceptions of the certainty and honesty of a speaker are associated with a common prosodic signature. Nat Commun 12:861. [CrossRef]

- Ponsot E, Burred JJ, Belin P, Aucouturier J-J (2018) Cracking the social code of speech prosody using reverse correlation. PNAS 115:3972-3977. [CrossRef]

- Schreibelmayr S, Mara M (2022) Robot voices in daily life: Vocal human-likeness and application context as determinants of user acceptance. Front Psychol 13:787499. [CrossRef]

- Alboksmaty A, Hayhoe B, Majeed A, Neves A-L (2025) Reclaiming the primary care consultation for patients and clinicians: is AI-enabled ambient voice technology the answer? J R Soc Med 0:01410768251360853. [CrossRef]

- Loh BCS, Fong AYY, Ong TK, Then PHH (2024) Revolutionising patient care: the role of AI-generated avatars in healthcare consultations. [CrossRef]

- Katsarou E, Wild F, Sougari A-M, Chatzipanagiotou P (2023) A systematic review of voice-based intelligent virtual agents in EFL education. Int J Emerg Technol Learn 18:65-85. [CrossRef]

- Terzopoulos G, Satratzemi M (2020) Voice assistants and smart speakers in everyday life and in education. Inform Educ 19:473-490. [CrossRef]

- Simpson EH (1951) The Interpretation of Interaction in Contingency Tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B 13:238-241. [CrossRef]

- Kievit RA, Frankenhuis WE, Waldorp LJ, Borsboom D (2013) Simpson’s paradox in psychological science: a practical guide. Front Psychol 4:513. [CrossRef]

- Hellbernd N, Sammler D (2016) Prosody conveys speaker’s intentions: Acoustic cues for speech act perception. J Mem Lang 88:70-86. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl PK (2011) Who’s talking? Science 333:529-530. [CrossRef]

- Bestelmeyer PEG, Belin P, Ladd DR (2014) A Neural Marker for Social Bias Toward In-group Accents. Cereb Cortex 25:3953-3961. [CrossRef]

- Baus C, McAleer P, Marcoux K, Belin P, Costa A (2019) Forming social impressions from voices in native and foreign languages. Sci Rep 9:414. [CrossRef]

- Afroogh S, Akbari A, Malone E, Kargar M, Alambeigi H (2024) Trust in AI: progress, challenges, and future directions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1568. [CrossRef]

- Rosero A, Dula E, Kelly H, Malle BF, Phillips EK (2024) Human perceptions of social robot deception behaviors: an exploratory analysis. “Front Robot AI 11:1409712. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Chen B, Lin J, Wang Y, Wang Y, Mehlman C, et al. (2024) Human-robot facial coexpression. Sci Robot 9:eadi4724. [CrossRef]

- Cihodaru-Ștefanache Ș, Podina IR (2025) Exploring the Uncanny Valley Effect: A Critical Systematic Review of Attractiveness, Anthropomorphism, and Uncanniness inUser-Embodied Conversational Agent Interaction. Front Psychol 16:1625984. [CrossRef]

- Mari A, Mandelli A, Algesheimer R (2024) Empathic voice assistants: Enhancing consumer responses in voice commerce. J Bus Res 175:114566. [CrossRef]

- Liu-Thompkins Y, Okazaki S, Li H (2022) Artificial empathy in marketing interactions: Bridging the human-AI gap in affective and social customer experience. J Acad Mark Sci 50:1198-1218. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu A, van Dijk B, Nijholt A, Li H, See SL (2013) Making Social Robots More Attractive: The Effects of Voice Pitch, Humor and Empathy. Int J Soc Robot 5:171-191. [CrossRef]

- Montag C, Spapé M, Becker B (2025) Can AI really help solve the loneliness epidemic? [CrossRef]

- Jones VK, Hanus M, Yan C, Shade MY, Blaskewicz Boron J, Maschieri Bicudo R (2021) Reducing loneliness among aging adults: the roles of personal voice assistants and anthropomorphic interactions. Front Public Health 9:750736. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).