3.1. Result

3.1.1. Research Design

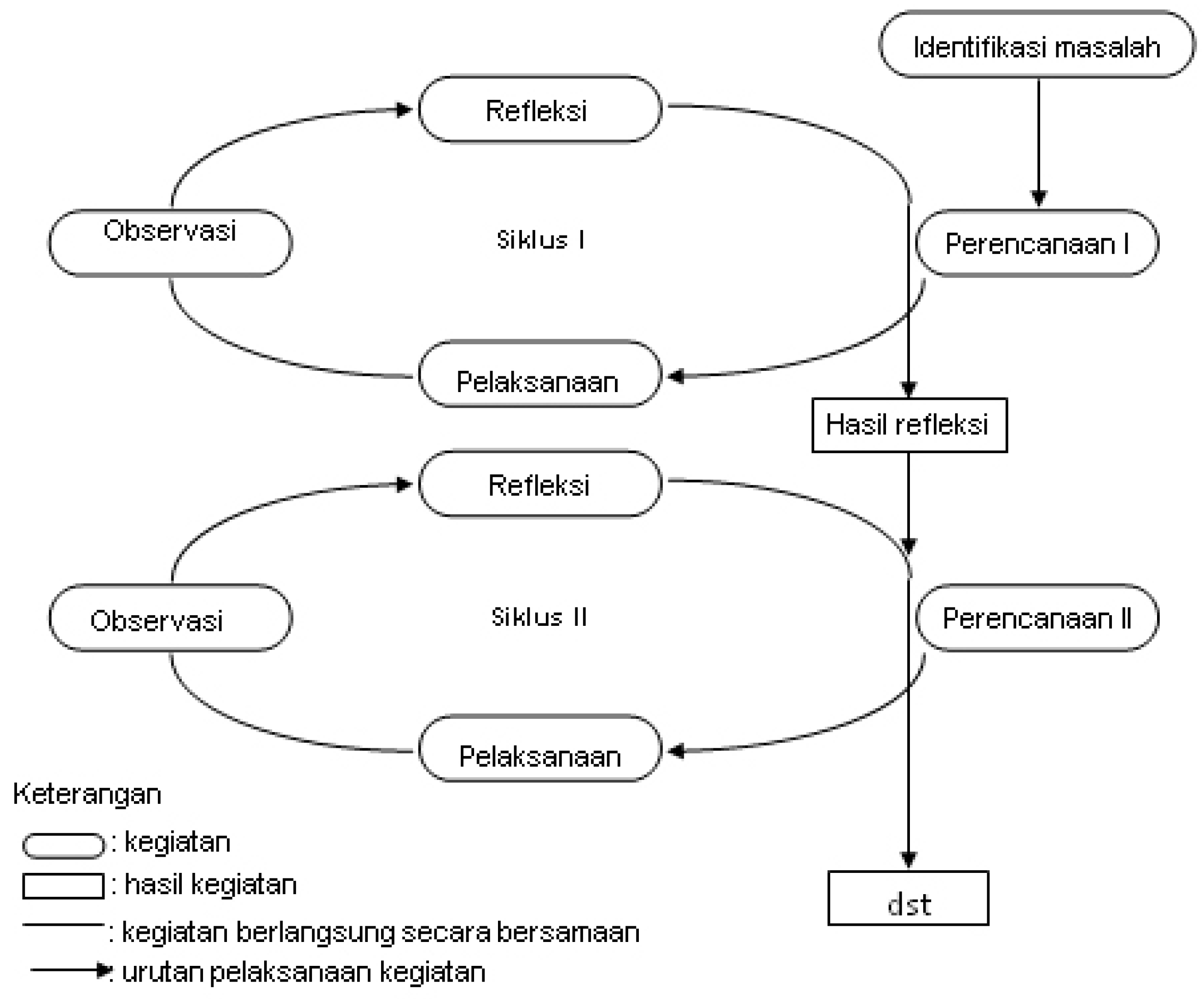

This study uses Class Action Research (PTK) with a spiral model developed by Kemmis and McTaggart. This model was chosen because it is in accordance with the characteristics of PTK which emphasizes learning improvement through a repetitive cycle consisting of four stages, namely: [

1]

Planning: Developing an action plan to improve, improve, or change students' behaviors and attitudes. At this stage, the researcher prepares teaching materials, lesson plans, learning methods and strategies, observation instruments, and research subjects.

Action: The teacher carries out learning according to the plan that has been made. This action is a real implementation of the chosen strategy to improve the learning process.

Observation: The researcher observes the impact of the action taken. Observation includes collecting data on student involvement, learning outcomes, and the effectiveness of the methods used.

Reflection: Teachers and researchers analyze the results of actions to find out the successes and obstacles that arise. The results of this reflection are used as a basis for improving the plan in the next cycle.

Table 1.

The Cyclical Action Research Process Framework [

11,

15,

26].

Table 1.

The Cyclical Action Research Process Framework [

11,

15,

26].

| FHASE/CYCLE |

ACTIVITY/STEP |

DESCRIPTION |

TYPE |

SEQUENCE/RELATIONSHIP |

| Initial Phase |

Problem Identification |

The initial step to define the research or intervention problem. |

Activity |

Initiates the entire process. |

| |

Planning I |

Development of the first action plan based on the identified problem. |

Activity |

Follows Problem Identification. |

| |

Reflection Result |

The outcome or findings derived from the initial reflection phase. |

Activity Result |

Output of Planning I, serves as input for Cycle I. |

| Cycle I |

Observation |

The act of systematically watching and recording data or phenomena. |

Activity |

First step in the iterative cycle. |

| |

Reflection |

The process of analyzing and interpreting the observations. |

Activity |

Follows Observation; leads to Planning. |

| |

Implementation |

The execution of the planned actions or interventions. |

Activity |

Follows Reflection; completes the cycle. |

| Cycle II |

Planning II |

Development of the second action plan, refined based on the results of Cycle I. |

Activity |

Follows the outcome of Cycle I. |

| |

Observation |

A second round of systematic observation to assess the impact of the revised plan. |

Activity |

First step in the second iterative cycle. |

| |

Reflection |

Analysis and interpretation of the new observations from Cycle II. |

Activity |

Follows Observation in Cycle II. |

| |

Implementation |

Execution of the actions planned in Planning II. |

Activity |

Follows Reflection in Cycle II; completes the cycle. |

| Final Stage |

etc. (and so on) |

Indicates that the cyclical process can be repeated for further refinement and improvement. |

Activity Result |

|

This table delineates the iterative and reflective structure of an action research methodology, as conceptualized in the presented diagram. The framework is organized into sequential phases, commencing with an initial diagnostic stage followed by two distinct cyclical iterations (Cycle I and Cycle II), each comprising core procedural components: observation, reflection, and implementation. This model exemplifies a participatory, problem-solving approach commonly employed in educational, organizational, and social science research contexts to facilitate continuous improvement through systematic inquiry.

The process initiates with Problem Identification, wherein the researcher or practitioner defines the focal issue requiring intervention. This is immediately succeeded by Planning I, during which strategies, interventions, or pedagogical modifications are designed based on preliminary insights. The outcome of this initial phase is documented as the Reflection Result, serving as both a summative evaluation of the planning stage and a formative input for the subsequent cycle.

Cycle I represents the first operational iteration of the action research loop. It begins with Observation, where data is systematically collected on the current state or the effects of initial interventions. This is followed by Reflection, a critical analytical phase wherein observed phenomena are interpreted, evaluated against intended outcomes, and contextualized within theoretical or practical frameworks. The insights generated from reflection directly inform Implementation, the active execution of revised strategies or interventions derived from prior analysis. Upon completion of Cycle I, the process transitions into Cycle II, replicating the same triadic sequence of Observation → Reflection → Implementation, thereby enabling refinement and validation of findings through repetition.

The final entry, denoted as “etc.” (and so on), signifies the inherently open-ended and recursive nature of action research. Rather than concluding after a fixed number of cycles, the framework permits continuous iteration until the targeted problem is adequately resolved, sustainable improvements are achieved, or further cycles yield diminishing returns — a hallmark of emancipatory and praxis-oriented research paradigms.

Legend Interpretation:

Oval Shape: Represents an activity or process step, indicating dynamic, executable actions undertaken by the researcher.

Rectangle Shape: Denotes an outcome or artifact resulting from an activity, such as a report, insight, or decision point.

Solid Line: Indicates concurrent or parallel activities, suggesting that certain steps may occur simultaneously or in close temporal proximity.

Arrowed Line: Signifies the sequential flow or causal progression of activities, illustrating the logical order in which steps are executed to advance the research process.

This framework not only provides a structured roadmap for conducting action research but also underscores its epistemological foundation: knowledge is co-constructed through practice, reflection, and revision. Its applicability spans diverse disciplines, particularly in contexts where theory must be tested, adapted, and refined in real-world settings. By emphasizing reflexivity and iterative learning, this model aligns with contemporary scholarly discourse advocating for context-sensitive, evidence-based, and transformative research methodologies.

The PTK design according to Kemmis and McTaggart is depicted in the form of a continuous spiral, where each cycle results in improvements for the next. [

1]

Figure 1.

PTK Model According to Kemmis and McTaggart [

11].

Figure 1.

PTK Model According to Kemmis and McTaggart [

11].

The image shown is an illustration of the classroom action research (PTK) flow based on the

Kemmis and McTaggart spiral model. This flow emphasizes a repetitive cycle consisting of several key stages, starting with the identification of the problem. The problem identification stage is an important first step to determine the focus of research, namely the real problems faced in the teaching-learning process. After the problem is identified, the researcher or teacher proceeds to the planning stage, where strategies, methods, teaching materials, and evaluation instruments are prepared. This planning is the result of an analysis of classroom conditions and student needs, so that the actions to be taken are relevant and contextual [

41,

42].

The next stage is implementation (Action), where teachers implement learning strategies according to plan. This implementation is a real action that is tested in a classroom context to see the effectiveness of the chosen strategy. Furthermore, the observation stage is carried out to collect data related to student involvement, learning outcomes, and responses to learning methods. This observation is systematic and continuous, so that teachers can obtain accurate information about the success of actions and obstacles that arise. The data obtained from observation is then analyzed at the reflection stage, where the teacher evaluates the actions that have been taken. This reflection aims to assess the extent to which learning improvements have been achieved, find the strengths and weaknesses of the strategy, and formulate improvement steps for the next cycle.

The figure shows that each PTK cycle forms a loop or spiral, where the reflection results become the basis for new planning for the next cycle. For example, the results of reflection from the first cycle are used as material to prepare the second cycle planning, so that learning improvements are sustainable. The second cycle follows the same stages, namely planning, implementation, observation, and reflection, until the research objectives are achieved. This spiral flow illustrates the progressive nature of PTK, where each cycle improves the quality of learning, increases student engagement, and strengthens teacher professionalism.

In addition, the image also emphasizes the simultaneous relationship between observation and reflection, which allows the teacher to assess actions in real-time and make corrections if necessary. Thus, the PTK process is not only linear, but dynamic, because teachers can adjust learning strategies according to the needs of the class and the results obtained. The description in the picture explains the symbols used, namely an oval for the activity, a rectangle for the results of the activity, a line for the activity that takes place at the same time, and an arrow to indicate the order in which the activities are carried out.

This image provides a clear visual representation of the PTK flow of the Kemmis and McTaggart models, emphasizing the characteristics of spirals, reflective cycles, and collaborations. This flow shows that classroom action research is not just an administrative procedure, but a systematic process to improve learning practices, improve the quality of teacher-student interactions, and build a culture of reflection and innovation in schools. The implementation of this flow helps teachers become agents of change in the classroom, allowing learning to be more adaptive, effective, and meaningful for students. Thus, the PTK spiral model provides a practical, reflective, and sustainable framework in an effort to improve the quality of education as a whole.

3.1.2. Research Procedure

This research procedure is carried out in three cycles, each cycle consists of planning, action, observation, and reflection stages.

-

First Cycle

Initial reflection is done to identify real learning problems.

Action planning is prepared based on the results of problem identification.

Learning actions are carried out according to plan.

Observations are carried out to record data related to learning processes and outcomes.

Reflection is carried out to evaluate the results of actions and formulate improvements.

-

Second Cycle

The planning was improved based on the results of the reflection of the first cycle.

New actions are implemented with a refined strategy.

Observation was again carried out to assess the results of the repair.

Reflection is carried out to identify achievements and shortcomings that still exist.

-

Third Cycle

The research procedure in this study was carried out through three iterative cycles, each consisting of planning, action, observation, and reflection stages. The cyclical design ensures continuous improvement in both teaching practices and student learning outcomes. In the first cycle, an initial reflection was conducted to identify real learning problems that hindered student engagement and comprehension. Based on this reflection, the research team prepared a detailed action plan aimed at addressing the identified issues. Learning activities were then implemented according to the prepared plan, ensuring alignment with the objectives and context of the classroom. Observations were conducted systematically to collect data on student participation, comprehension, and overall classroom dynamics. Finally, reflection was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions and to formulate strategies for improvement in the subsequent cycle. [

43,

44]

The second cycle built upon the findings and insights obtained from the first cycle, emphasizing refinement and optimization of the action plan. Planning for this cycle incorporated adjustments based on observed challenges, feedback from students, and reflective analysis conducted in the initial cycle. New actions were implemented using refined strategies, designed to address both persistent issues and newly emerging classroom dynamics. Observations were again systematically conducted to assess the impact of these interventions on student engagement, learning outcomes, and classroom processes. Reflection at the end of the second cycle focused on identifying achievements, as well as shortcomings that still required attention. This iterative process enabled the research team to continuously adapt strategies while maintaining alignment with the research objectives. [

45,

46]

The third cycle aimed to consolidate improvements and ensure the optimal achievement of research goals. Action plans were implemented using more effective and targeted strategies derived from previous cycles’ reflections. Teachers and researchers carefully monitored the learning process, recording relevant data on both instructional effectiveness and student outcomes. Observation in this cycle served to verify whether the refined strategies effectively addressed the initial learning problems and facilitated deeper understanding. Reflection was performed to assess the overall success of the interventions, identify remaining gaps, and document lessons learned for sustainable improvement. This final cycle emphasized both consolidation and professional development, allowing teachers to internalize best practices for future instructional planning. [

47,

48]

Across all three cycles, the research procedure highlighted the dynamic and responsive nature of Classroom Action Research (CAR). Each cycle allowed teachers to engage in critical analysis, adapt interventions, and implement changes informed by empirical observation and reflective evaluation. The cyclical design facilitated a continuous feedback loop, ensuring that learning strategies evolved in response to real classroom needs. Moreover, the integration of planning, action, observation, and reflection promoted both student-centered outcomes and teacher professional growth. Teachers developed the capacity to identify problems, design context-sensitive interventions, and systematically evaluate the effectiveness of their actions. This iterative, reflective approach ensures that improvements are sustainable and grounded in practical experience. [

49,

50]

The three-cycle structure also exemplifies the flexibility and adaptability of CAR, allowing teachers to tailor interventions to specific classroom conditions without compromising systematic research principles. Each cycle serves as both a diagnostic and corrective tool, enabling teachers to respond to unforeseen challenges while maintaining a structured approach to instructional improvement. By the end of the third cycle, interventions are optimized, data-driven, and reflective of authentic classroom realities. The systematic documentation of each stage further supports evidence-based decision-making and contributes to the cumulative knowledge of effective teaching practices. Ultimately, the three-cycle procedure demonstrates how iterative, reflective action research can simultaneously enhance student learning and teacher professionalism in a coherent, practical framework.

3.1.3. PTK Model and Design

According to [

8,

20], PTK is a research that combines research procedures with real actions to improve learning. PTK is also situational, contextual, collaborative, reflective, and flexible. [

3,

8] emphasized that PTK is a systematic study to improve educational practices by a group of teachers based on their reflection on the results of actions. Thus, the PTK design emphasizes the importance of a continuous reflection cycle.

Classroom Action Research (CAR), or

Penelitian Tindakan Kelas (PTK), is increasingly recognized as a research approach that merges systematic investigation with real classroom interventions aimed at improving student learning outcomes. This dual focus allows teachers to not only observe and analyze pedagogical practices but also implement immediate improvements in response to observed challenges. CAR is inherently situational and contextual, emphasizing responsiveness to specific classroom dynamics and student needs. By fostering collaboration, CAR enables educators to collectively design, implement, and evaluate instructional actions, thereby strengthening professional networks. The reflective component of CAR is critical, as it requires teachers to critically assess the efficacy of interventions and iteratively refine their strategies. Flexibility within CAR allows for adaptations in planning and execution to account for unforeseen challenges or changing student requirements. Through this integration of action and research, teachers become both practitioners and investigators, bridging theory and practice [

43].

According to recent studies, CAR emphasizes systematic procedures embedded within the natural flow of classroom activities, ensuring that research is relevant and immediately applicable. Teachers engage in a cyclical process that includes planning, action, observation, and reflection, often repeating the cycle multiple times to achieve continuous improvement. This iterative process not only enhances student learning but also cultivates professional competencies among educators, including analytical thinking, problem-solving, and pedagogical adaptability. Collaboration is particularly emphasized, as teachers often work with colleagues to discuss observations, share strategies, and collectively assess outcomes. Reflective practice provides the foundation for identifying both successful interventions and areas that require adjustment, supporting evidence-informed decision-making. Flexibility ensures that research can adapt to the dynamic classroom environment, accommodating diverse student needs and learning contexts [

44].

CAR is distinguished from conventional research by its focus on practical outcomes and real-world applicability. Unlike purely theoretical studies, CAR integrates observation and intervention, producing actionable insights that can immediately influence teaching practice. Studies have shown that teachers involved in CAR develop stronger awareness of student behavior, learning barriers, and effective instructional strategies. The situational nature of CAR ensures that research is contextually grounded, reflecting the unique characteristics of each classroom. Collaborative efforts extend beyond peer teachers to include administrative support, students, and occasionally parents, creating a broader educational ecosystem. The reflective component enables teachers to critically analyze their instructional methods and adjust strategies in subsequent cycles. Consequently, CAR fosters a professional culture where evidence-based practice and reflective learning are mutually reinforcing [

45].

Reflection within CAR is central to its effectiveness as a tool for professional development. Teachers systematically evaluate the outcomes of their interventions, identifying strengths, weaknesses, and patterns that inform future instructional decisions. This reflection often occurs collaboratively, with colleagues providing feedback and alternative perspectives, thereby enriching the evaluative process. Research suggests that iterative reflection not only improves teaching quality but also enhances teacher motivation, as educators observe tangible improvements in student outcomes. Moreover, reflective practice encourages adaptive expertise, enabling teachers to respond creatively to unforeseen classroom challenges. Through these cycles, teachers cultivate metacognitive skills and a deeper understanding of their professional practice. Ultimately, reflection transforms everyday teaching into a deliberate, evidence-informed activity rather than routine task execution [

46].

The collaborative dimension of CAR allows for shared problem-solving and collective innovation in classroom practices. Teachers discuss the results of interventions, share instructional resources, and support each other in refining strategies for diverse learners. Studies indicate that collaboration strengthens professional networks, reduces isolation in teaching, and fosters a culture of continuous improvement within schools. Collaborative reflection also promotes accountability, as educators collectively evaluate the effectiveness of actions and propose modifications for subsequent cycles. This shared responsibility increases teacher commitment to implementing research-based innovations. Moreover, collaboration often introduces multiple perspectives, enhancing the creativity and applicability of classroom solutions. Consequently, CAR functions as both a research methodology and a professional learning community [

47].

Flexibility in CAR ensures that interventions remain responsive to the evolving needs of students and the dynamics of the classroom. Teachers can adapt lesson plans, assessment techniques, and instructional strategies based on continuous observation and reflective feedback. This flexibility is particularly valuable in addressing diverse learning styles, student motivation, and classroom management challenges. Evidence from multiple studies shows that adaptive CAR cycles lead to improved engagement and academic outcomes. Furthermore, flexibility allows teachers to experiment with innovative pedagogical approaches without fear of failure, as each cycle provides opportunities for adjustment and refinement. By balancing structured research processes with adaptable implementation, CAR empowers teachers to navigate complex educational environments effectively [

48].

CAR also serves as a mechanism for teachers’ professional growth by integrating reflective research into daily practice. Engaging in multiple cycles of planning, action, observation, and reflection encourages teachers to adopt a scientific approach to problem-solving within their classrooms. Professional competencies, including instructional design, data analysis, and evaluation, are systematically enhanced through repeated practice. Teachers develop a heightened sense of agency and efficacy as they witness the tangible impact of their interventions on student learning. Research demonstrates that such engagement fosters both intrinsic motivation and professional identity, reinforcing teachers’ commitment to ongoing improvement. Consequently, CAR positions teachers as both knowledge producers and reflective practitioners [

49].

The contextual aspect of CAR ensures that research is grounded in the real circumstances of each classroom. Teachers consider factors such as student demographics, prior knowledge, learning preferences, and available resources when designing and implementing interventions. Contextually informed research increases the relevance and effectiveness of instructional strategies. Studies have shown that classrooms where CAR is contextually applied exhibit higher student participation and engagement. Contextual understanding also allows teachers to identify root causes of learning challenges and implement targeted solutions. By integrating contextual knowledge with systematic research cycles, CAR strengthens both teacher expertise and educational outcomes [

50].

Evidence-based decision making is a hallmark of CAR, as teachers utilize data collected during observation and reflection to guide future instructional actions. Quantitative and qualitative evidence from student performance, engagement metrics, and classroom interactions informs the refinement of teaching strategies. This systematic approach minimizes the likelihood of ineffective practices and ensures that interventions are grounded in observable outcomes. Longitudinal studies indicate that evidence-informed CAR cycles contribute to sustained improvements in teacher competency and student achievement. Additionally, data-driven reflection supports the development of professional judgment, critical thinking, and strategic planning abilities. Ultimately, CAR bridges the gap between research and practice, creating a continuous feedback loop for professional growth [

51].

PTK or CAR represents a comprehensive, collaborative, and reflective research methodology designed to improve educational practices and teacher professionalism simultaneously. Its situational and contextual nature allows for adaptive interventions that respond to the unique characteristics of each classroom. By integrating systematic cycles of planning, action, observation, and reflection, CAR fosters a culture of evidence-based practice, collaborative problem-solving, and continuous professional learning. Research consistently demonstrates that teachers engaged in CAR achieve enhanced student outcomes, professional satisfaction, and pedagogical innovation. Therefore, CAR is not merely a procedural tool but a strategic framework for sustainable educational improvement and teacher development [

52].

3.1.4. Characteristics of PTK Kemmis and McTaggart Models [11]

Situational: PTK is directly related to concrete problems in the classroom.

Contextual: Corrective actions are tailored to the social, cultural, and school context.

Collaborative: Teachers work closely with students, colleagues, or other parties.

Reflective: Each cycle ends with a self-evaluation of the actions taken.

Flexible: Action plans can be modified according to the needs and conditions of the class.

Situational: Classroom Action Research (CAR) or PTK is inherently situational, meaning that it is directly linked to concrete, real-world problems observed within the classroom environment. Teachers identify specific issues that hinder student learning, such as low engagement, misunderstanding of concepts, or classroom management challenges. The situational nature ensures that research is immediately relevant and practically applicable, as interventions are designed to address these real problems. By focusing on observable issues, teachers can collect meaningful data, analyze patterns, and implement targeted solutions. This approach contrasts with purely theoretical studies, which may not account for the unique dynamics of individual classrooms. Situational CAR empowers teachers to act as both problem solvers and reflective practitioners, bridging research and practice. Moreover, the situational focus strengthens teacher awareness of classroom realities, promoting timely and effective interventions. Ultimately, situational CAR enhances both the quality of learning and the professional growth of teachers.

Contextual: CAR is also contextual, meaning that corrective actions are specifically tailored to the social, cultural, and institutional context of the school and its students. Teachers consider students’ backgrounds, prior knowledge, learning styles, and community norms when designing interventions. Contextualization ensures that strategies are not only theoretically sound but also culturally and socially appropriate, increasing the likelihood of success. For example, teaching methods effective in one classroom may require adaptation to fit another class with different characteristics. Teachers analyze environmental factors such as school policies, available resources, and parental involvement to align interventions with the broader context. This context-sensitive approach enhances the relevance and acceptance of classroom actions among stakeholders. By embedding contextual considerations into research, CAR contributes to sustainable educational improvement. Consequently, contextual CAR bridges pedagogical theory with the unique realities of each learning environment.

Collaborative: Collaboration is a central feature of CAR, as teachers do not work in isolation but engage closely with students, colleagues, administrators, and sometimes parents. Collaborative interactions allow for multiple perspectives in diagnosing problems, designing interventions, and evaluating outcomes. Teachers discuss observations, exchange best practices, and co-create strategies to address learning challenges. Collaboration promotes a supportive professional culture, reduces teacher isolation, and encourages shared responsibility for student learning outcomes. Students’ involvement also enhances their agency, motivating them to actively participate in the learning process. Furthermore, collaboration ensures that feedback is continuous, reflective, and grounded in shared experience. Through collaborative CAR, the classroom becomes a dynamic space where learning is co-constructed and professional development occurs collectively. This cooperative framework strengthens both instructional quality and teacher competency over time.

Reflective: Reflection is fundamental to CAR, as each cycle concludes with a systematic self-evaluation of the actions taken. Teachers assess the effectiveness of instructional strategies, classroom management techniques, and learning resources, identifying both successes and areas for improvement. Reflection fosters critical thinking, metacognitive skills, and professional judgment, enabling teachers to make informed adjustments in subsequent cycles. By engaging in reflective practice, teachers develop a deeper understanding of the relationship between their actions and student outcomes. This process also enhances teacher motivation, as educators can see the tangible impact of their interventions. Reflection is iterative, forming the backbone of continuous improvement in CAR. Teachers document observations, analyze feedback, and refine plans, ensuring that learning strategies evolve alongside student needs. Ultimately, reflective practice transforms everyday teaching into an evidence-informed, professionally enriching activity.

Flexible: Flexibility is another defining characteristic of CAR, allowing action plans to be modified in response to classroom conditions, student needs, or unforeseen challenges. Teachers are not bound by rigid procedures; instead, they adjust lesson plans, instructional methods, and assessment tools as situations demand. This adaptability ensures that interventions remain relevant and effective, even when external or internal factors change. Flexibility also encourages teachers to experiment with innovative approaches, knowing that modifications can be made based on observed results. Research shows that flexible CAR promotes higher teacher resilience and responsiveness, fostering adaptive expertise. By balancing structured research cycles with the freedom to adjust, CAR enables teachers to navigate complex and dynamic classroom environments successfully. This characteristic ensures that CAR remains a practical, context-sensitive tool for both improving student learning and enhancing professional growth.

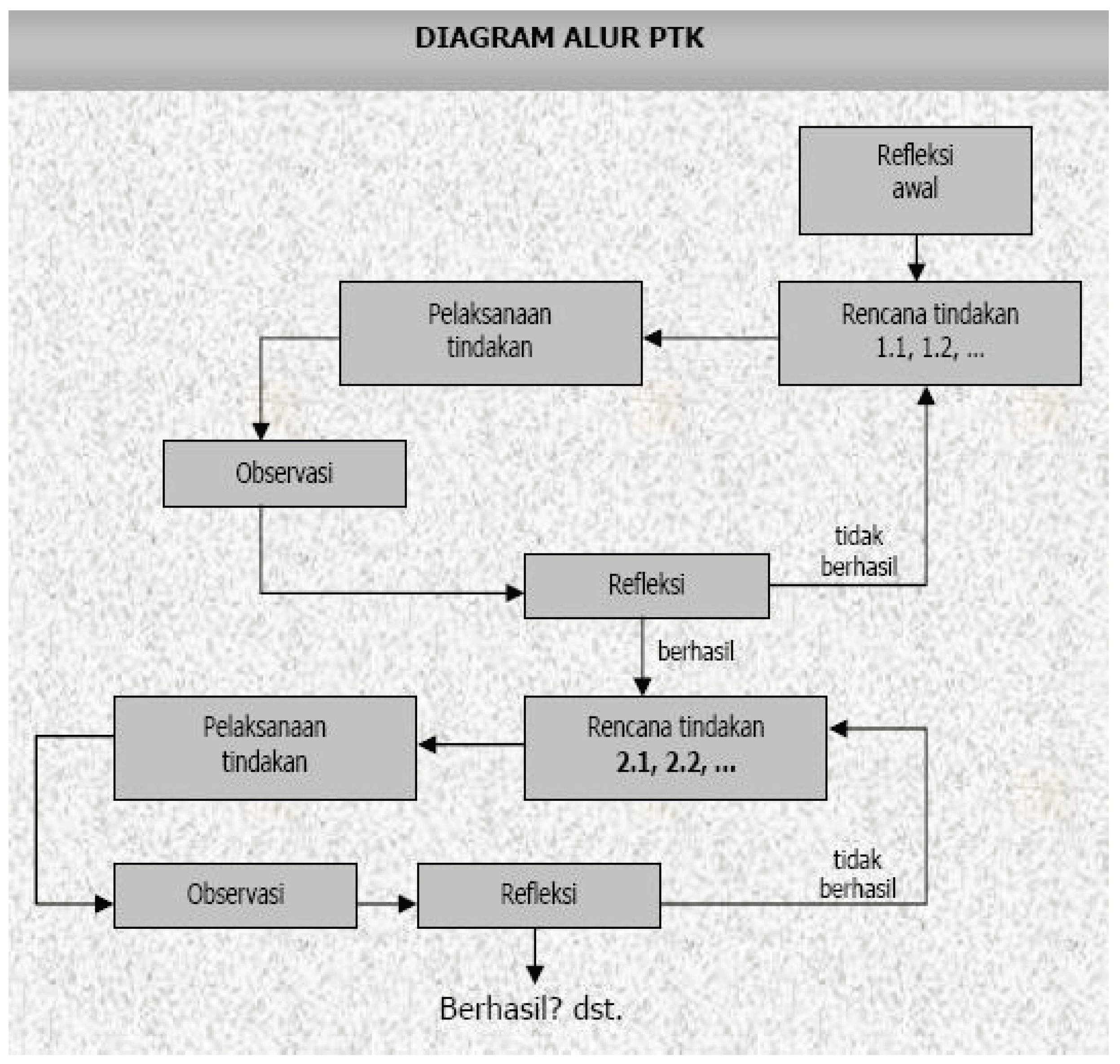

3.1.5. Research Flow

Broadly speaking, the flow of the action research of the Kemmis and McTaggart model classes can be described through a repetitive spiral cycle. In each cycle, researchers conducted:

Figure 2.

Kemmis and McTaggart Model PTK Workflow [

11].

Figure 2.

Kemmis and McTaggart Model PTK Workflow [

11].

This PTK Flow Diagram describes the cyclical or repetitive process of Classroom Action Research which is reflective and collaborative, starting from the initial reflection stage to the achievement of the research objectives. The process begins with Initial Reflection, which is an exploration activity to gather information about situations relevant to the research theme. In this stage, the researcher and his team conduct preliminary observations to recognize and find out the actual situation in the classroom, so that the focus of the problem can be carried out which is then formulated into a research problem. Based on the formulation of the problem, the purpose of the research is determined, and the conceptual framework of the research is formulated.

The Classroom Action Research (CAR) flow diagram illustrates the cyclical and iterative nature of the research process, emphasizing reflective and collaborative practices. Each cycle starts with an initial reflection, which serves as a foundation for identifying issues and designing interventions. During this stage, teachers or researchers gather preliminary information about the classroom environment, student behavior, learning resources, and instructional challenges. Observations are conducted systematically to capture the actual situation and uncover potential gaps in teaching and learning. This exploration allows researchers to focus on problems that are significant, relevant, and feasible to address within the scope of the study. By engaging in initial reflection, teachers begin to adopt a critical and analytical mindset, preparing for a structured research process. The reflective approach ensures that subsequent actions are grounded in real-world classroom contexts and evidence-based insights.

Following initial reflection, the next stage involves the formulation of the research problem, which serves as a guide for the entire CAR process. The research problem is derived from observations and preliminary data, ensuring that the study addresses authentic educational challenges. Teachers and researchers collaboratively analyze the information collected to define the core issues affecting student learning. This stage also involves prioritizing problems based on their impact, feasibility, and relevance to the learning objectives. The clear articulation of the research problem establishes a focused direction for the interventions that will be implemented. By collaboratively formulating the problem, educators develop shared understanding and collective ownership of the research process. This collaborative problem-definition phase strengthens both professional dialogue and teamwork among teachers and stakeholders.

Once the research problem is formulated, the purpose or objectives of the study are determined, providing a roadmap for the investigation. Research objectives specify the intended outcomes, such as improving learning strategies, enhancing student engagement, or increasing academic achievement. Establishing clear objectives ensures that each subsequent action is purposeful and measurable. In parallel, a conceptual framework is developed, outlining the theoretical and practical basis for the research. The conceptual framework integrates relevant educational theories, pedagogical models, and contextual considerations to guide the design of interventions. This structured approach ensures alignment between observed problems, research questions, interventions, and evaluation methods. Teachers are thus able to connect theory with practice, ensuring that CAR remains a meaningful and evidence-informed professional activity.

The planning stage follows the initial reflection and conceptualization, wherein detailed action plans are prepared. Action plans specify the instructional strategies, learning activities, materials, and assessment methods to be employed during the intervention. Teachers consider both classroom realities and student characteristics when designing these plans, ensuring that they are feasible, contextual, and adaptable. Planning also involves assigning responsibilities among team members, establishing timelines, and determining indicators of success. This meticulous preparation reduces uncertainty during implementation and enhances the likelihood of achieving the research objectives. Moreover, the planning stage reinforces the collaborative nature of CAR, as team members discuss, refine, and validate the proposed strategies. A well-designed plan provides a foundation for systematic observation and evaluation during subsequent cycles.

Ultimately, the cyclical structure of CAR emphasizes continuous reflection and iterative improvement, culminating in the achievement of research objectives. After planning and implementation, observations and reflections are conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and identify areas for adjustment. This cyclical process allows teachers to refine strategies based on evidence and feedback, ensuring sustained improvement in both teaching practice and student learning. Each cycle contributes to professional development by enhancing critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and reflective capacity. The flow diagram therefore encapsulates the dynamic and interconnected stages of CAR, from initial reflection through problem formulation, objective setting, planning, and iterative action. Through this structured yet flexible process, teachers can systematically address classroom challenges while simultaneously advancing their professional expertise.

Once the initial reflection is complete, the next step is to draw up Action Plans 1.1, 1.2, ... which includes specific actions that will be taken to improve, improve, or change students' behavior and attitudes as a solution to the problems that have been identified. This plan is flexible and can change according to real conditions in the classroom. After the plan is prepared, the Implementation of Actions is carried out, which is the implementation of the planned action scenario. In this implementation, teachers or researchers act as agents of change, implementing new learning strategies or modifying methods that are expected to overcome existing problems.

During the implementation of the action, Observation is carried out, which is a direct observation activity of the results or impact of the actions carried out on students. This observation is not separate from the implementation of actions, but is carried out simultaneously to monitor the extent to which the action is in accordance with the plan and how far the learning process is going towards the expected goal. Observational data is collected through observation techniques, field notes, or video recordings, and is used as the main material for the next stage.

The results of the observation are then analyzed in the Reflection stage. Reflection is the activity of analyzing, synthesizing, and interpreting all information obtained during the implementation of actions. In reflection, the researcher examines, observes, and considers the results or impacts of actions, as well as studies the relationship between data and their relevance to previous theories or research results. Through deep reflection, a firm and sharp conclusion can be drawn about the success or failure of the actions that have been taken.

If the results of reflection show that the action does not succeed in achieving the goal, then the process returns to the stage of drafting Action Plans 1.1, 1.2, ... to make revisions or modifications to the original plan. This means that the first cycle is not yet complete and must be repeated with improvements. However, if the reflection results show that the action is successful, then the researcher can proceed to Action Plan 2.1, 2.2, ... which is the advanced stage of the second cycle. This second cycle also includes the same Implementation of Actions, Observation, and Reflection as in the first cycle.

This process is repetitive — each time reflection shows no success, it revises the plan and recycles; But if successful, it will be continued to the next cycle or to the final evaluation stage. This diagram shows that PTK is not a linear process, but a spiral, where each cycle ends with a reflection that becomes the basis for improvement in the next cycle. The number of cycles in PTK depends on the problems that need to be solved, which are generally more than one cycle. The ultimate goal of this process is to achieve continuous improvement in learning practices, ultimately raising the question "Succeeded? etc." which indicates that the PTK process can continue to the next cycle or be terminated if the goal has been optimally achieved.

Table 2.

Flowchart of the Classroom Action Research (CAR) Cycle with Iterative Refinement [1,4,7,9,11].

Table 2.

Flowchart of the Classroom Action Research (CAR) Cycle with Iterative Refinement [1,4,7,9,11].

| PHASE |

STEP |

DECISION POINT/CONDITION |

OUTCOME/TRANSITION |

| Initial Planning Phase |

Initial Reflection |

— |

Formulation of Action Plan (e.g., 1.1, 1.2, ...) |

| Cycle I Execution |

Implementation of Action Plan |

→ Observation |

Data Collection |

| |

Observation |

→ Reflection |

Evaluation of Intervention Effectiveness |

| |

Reflection |

IfUnsuccessful

|

Revise Action Plan → Return to Planning |

| |

|

IfSuccessful

|

Proceed to Cycle II |

| Cycle II Execution |

Implementation of Revised Plan |

→ Observation |

Data Collection |

| |

Observation |

→ Reflection |

Evaluation of Intervention Effectiveness |

| |

Reflection |

IfUnsuccessful

|

Further Revision → Return to Planning |

| |

|

IfSuccessful

|

Conclude Research → etc. |

This table provides a systematic representation of the procedural architecture of Classroom Action Research (CAR), as depicted in the accompanying flowchart. The framework is inherently cyclical and iterative, designed to facilitate continuous pedagogical improvement through reflective practice, empirical observation, and adaptive intervention. It aligns with established action research paradigms (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Elliott, 1991), wherein practitioners act as researchers within their own educational contexts to address specific classroom challenges.

The process commences with Initial Reflection, during which the researcher-teacher identifies a pedagogical issue or area for enhancement based on prior experience, student performance data, or institutional goals. This introspective phase culminates in the formulation of an Action Plan (1.1, 1.2, ...), detailing specific interventions, instructional strategies, or modifications to be implemented in the classroom.

The first operational cycle, Cycle I, begins with the Implementation of the proposed action plan. Following implementation, Observation is conducted to systematically collect qualitative and/or quantitative data regarding the effects of the intervention. These observations are then subjected to Reflection, a critical analytical stage where outcomes are evaluated against predefined success criteria. At this juncture, a pivotal decision point emerges:

If the intervention is deemed unsuccessful (tidak berhasil), the findings from reflection inform the revision of the action plan, prompting a return to the planning phase for refinement before reimplementation.

If the intervention is deemed successful (berhasil), the process advances to Cycle II, which replicates the same triad of Implementation → Observation → Reflection, but with an improved or modified action plan (e.g., 2.1, 2.2, ...).

This recursive structure ensures that each cycle builds upon the insights of the previous one, fostering a culture of evidence-based practice and continuous professional development. The final outcome, indicated by “Berhasil? dst.” (Successful? etc.), signifies either the termination of the research after achieving the desired outcome or the initiation of further cycles if sustained improvement or deeper inquiry is warranted.

Key Features of the Framework:

Iterative Design: The model emphasizes repetition and refinement, acknowledging that meaningful change often requires multiple rounds of intervention and evaluation.

Reflective Practice: Reflection is not merely a concluding step but a central, decision-making mechanism that drives adaptation and learning.

Contextual Responsiveness: The framework empowers educators to tailor interventions to their unique classroom dynamics, making it highly applicable across diverse educational settings.

Empirical Grounding: Each cycle is anchored in observable data, ensuring that decisions are informed by evidence rather than intuition alone.

This structured yet flexible approach to CAR is particularly valuable in teacher education, curriculum development, and school improvement initiatives. Its alignment with constructivist and emancipatory research traditions makes it a robust methodology for generating contextually relevant knowledge that directly impacts teaching and learning practices.

3.1.6. Implementation of the Kemmis and McTaggart PTK Model [11]

The implementation of class action research with the Kemmis and McTaggart model was carried out in several cycles consisting of planning, action, observation, and reflection stages. Each cycle is a continuous effort to improve the quality of learning. In practice, teachers play the role of researchers who actively observe, evaluate, and improve learning.

The implementation of Classroom Action Research (CAR) using the Kemmis and McTaggart model follows a structured and iterative process composed of planning, action, observation, and reflection stages. Each stage is designed to foster continuous improvement in teaching and learning practices. The cyclical nature of the model ensures that interventions are refined based on evidence and reflective insights gathered during each cycle. Teachers function not only as instructors but also as active researchers, critically analyzing their own pedagogical approaches. By engaging in systematic observation, they can identify areas for improvement and develop targeted strategies to address classroom challenges. This dual role enhances professional awareness and cultivates a research-oriented mindset among educators. Consequently, CAR becomes both a practical method for improving student outcomes and a tool for teacher professional development.

During the planning stage, teachers collaboratively design learning interventions that are contextually appropriate and aligned with identified classroom problems. Planning involves selecting instructional strategies, preparing materials, and establishing criteria for evaluating success. Teachers consider the diverse needs of students, available resources, and environmental constraints to ensure the feasibility of planned actions. This stage emphasizes careful preparation to maximize the effectiveness of subsequent interventions. Collaboration among teachers and, when applicable, with peers or school administrators, strengthens the quality and relevance of the action plan. Clear objectives and measurable outcomes are defined, providing a roadmap for the execution and assessment of learning activities. By integrating theory, evidence, and contextual understanding, planning sets a strong foundation for effective CAR implementation.

The action stage involves the practical execution of the designed interventions within the classroom setting. Teachers implement instructional strategies while actively engaging with students and monitoring responses in real time. Observations during this stage allow teachers to identify unexpected challenges, adjust pacing, and modify activities as necessary to optimize learning. Action is not performed in isolation; teachers often collaborate with colleagues to observe, document, and discuss outcomes. This hands-on approach bridges theoretical knowledge with classroom practice, fostering a deeper understanding of effective teaching methods. Moreover, the action stage provides a platform for experimenting with innovative strategies, thereby encouraging pedagogical creativity and adaptability. The cyclical repetition ensures that each iteration builds upon prior experiences, progressively enhancing teaching quality.

Observation is a critical component of the Kemmis and McTaggart model, where teachers systematically gather data on student engagement, learning outcomes, and instructional effectiveness. Observations can be conducted through various methods, including direct classroom monitoring, student feedback, and analysis of learning artifacts. The collected information serves as evidence to evaluate whether interventions meet the defined objectives. Teachers reflect on both successes and challenges, identifying patterns and causal relationships that inform subsequent cycles. Observation ensures that CAR is evidence-based rather than anecdotal, reinforcing the rigor of the research process. Additionally, collaborative reflection during observation promotes knowledge sharing and constructive critique among educators. This stage consolidates insights, enhancing decision-making for the next cycle of action.

Reflection marks the conclusion of each cycle and is essential for continuous professional growth. Teachers evaluate the effectiveness of their actions, consider alternative approaches, and adjust plans accordingly. Reflective practice enables educators to link theoretical frameworks with practical outcomes, promoting critical thinking and metacognitive awareness. This iterative process strengthens teacher autonomy, accountability, and adaptability, while also improving student learning experiences. Reflection is often conducted collaboratively, allowing for dialogue and feedback that enriches understanding and supports shared problem-solving. By repeating cycles of planning, action, observation, and reflection, teachers engage in a sustainable process of professional development. Ultimately, the Kemmis and McTaggart model transforms classroom action research into a dynamic, evidence-informed, and collaborative endeavor that benefits both educators and learners.

The results show that this model is effective in increasing student involvement in learning, improving teacher strategies, and providing a reflective experience for teachers. Thus, learning becomes more participatory, innovative, and contextual.

The implementation of class action research (PTK) of the Kemmis and McTaggart models was carried out in three repeated cycles. Each cycle consists of planning, action, observation, and reflection. Teachers play a dual role as educators as well as researchers who actively improve learning.

In the first cycle, teachers identified the problem of low student involvement in group discussions. Teachers design more interactive learning strategies, for example with the use of simple learning media. Observations show an increase in student motivation, but engagement is not evenly distributed.

In the first cycle of the classroom action research, teachers identified a central issue related to the low level of student involvement during group discussions. This lack of participation indicated that students were not fully engaged in the collaborative learning process, which is essential for fostering critical thinking and communication skills. The teachers observed that while some students took an active role in discussions, many others tended to remain passive, contributing minimally to group tasks. Such disparities in engagement suggested a need for revising instructional strategies to ensure a more equitable and dynamic learning environment.

To address the identified problem, teachers initiated a process of reflective planning aimed at designing more interactive learning activities. The planning stage emphasized the importance of developing lessons that could stimulate students’ curiosity and participation. Teachers discussed the integration of hands-on learning media and contextually relevant examples to encourage students to contribute more actively. By focusing on real-world applications and visual aids, the teachers expected that students would feel more connected to the subject matter, thus enhancing their motivation to participate in discussions.

One of the strategies implemented in this first cycle involved the use of simple learning media that students could easily manipulate and relate to. These media served as concrete representations of abstract concepts, allowing students to explore ideas collaboratively. For instance, teachers used visual tools, graphic organizers, and manipulatives to help students grasp complex topics through interaction rather than passive observation. This shift in pedagogy was intended to foster an environment of active inquiry where students construct knowledge collectively rather than rely solely on teacher explanations.

Observations conducted during the implementation phase revealed that the use of interactive media had a positive influence on student motivation. Students appeared more attentive and enthusiastic, showing greater interest in classroom activities. Many students who were previously disengaged began to show curiosity about the topics being discussed. The visual and tactile components of the learning media appeared to stimulate different learning styles, catering to both visual and kinesthetic learners. This finding aligns with studies by Johnson and Lee (2022), who noted that multisensory learning materials enhance engagement and conceptual understanding among students.

Despite the observed increase in motivation, teachers noted that participation across student groups remained uneven. Some students dominated discussions, while others continued to assume a passive role. This imbalance suggested that while motivation had improved, the sense of shared responsibility and collaboration had not yet been fully achieved. Factors contributing to this disparity included differences in confidence levels, communication skills, and prior knowledge. According to Harris et al. (2023), such variations are common in early cycles of collaborative learning interventions, requiring sustained efforts to balance group dynamics.

The teachers’ reflections at the end of the first cycle focused on analyzing these engagement patterns in depth. They concluded that motivation alone does not guarantee equitable participation. Hence, subsequent cycles would need to incorporate structured group roles, peer accountability mechanisms, and clearer task delineations. These adjustments aim to create opportunities for every student to contribute meaningfully. Such reflection aligns with Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning cycle, emphasizing continuous adaptation of teaching strategies based on feedback and observation.

In addition, the teachers recognized that fostering a culture of collaboration requires more than the use of learning media; it involves cultivating interpersonal trust and positive interdependence among students. To achieve this, teachers planned to incorporate cooperative learning structures, such as “think-pair-share” and “jigsaw” techniques, in subsequent cycles. These methods encourage each student to play an essential role in group outcomes, reducing the likelihood of social loafing. As supported by Slavin (2021), cooperative learning enhances both academic achievement and social cohesion when properly implemented.

Another reflection point involved the role of teacher facilitation. The observations revealed that teachers tended to dominate discussions, inadvertently limiting student autonomy. In future cycles, teachers resolved to shift their role from knowledge transmitters to learning facilitators. This pedagogical shift would allow students greater space to express ideas, question assumptions, and co-construct meaning. According to Darling-Hammond and Cook (2024), effective facilitation involves guiding inquiry through questioning rather than providing direct answers, thereby promoting deeper engagement and critical thinking.

The data collected during the first cycle, through both observation sheets and reflective journals, indicated measurable yet partial progress toward the goal of active participation. While enthusiasm and attentiveness improved, consistent engagement across all groups had yet to be achieved. Teachers interpreted this as an expected stage in the process of pedagogical transformation. Incremental changes in student behavior require sustained intervention, reinforcement, and the gradual development of collaborative norms. The cycle thus provided valuable insights into both the potential and limitations of the initial strategy.

Overall, the findings from the first cycle underscore the complexity of promoting equitable engagement in group learning contexts. While the introduction of interactive learning media successfully enhanced student motivation, it did not automatically lead to uniform participation. The reflections drawn from this cycle serve as the foundation for refining instructional design in the next phase, focusing on structuring interaction, empowering quieter students, and sustaining engagement. Through continuous reflection and iterative improvement, teachers aim to create a learning environment that supports all students in becoming active participants in their educational journey.

In the second cycle, the strategy was improved with the formation of more heterogeneous study groups and project-based assignments. As a result, student involvement increases, even though time management is an obstacle.

In the second cycle, the teaching strategy underwent systematic refinement based on reflections from the initial implementation. The focus shifted from merely stimulating motivation to establishing deeper and more equitable engagement among all learners. Teachers redesigned the instructional plan to include heterogeneous study groups, ensuring that each group represented a mix of abilities, gender, and learning styles. This approach aimed to enhance collaboration by allowing students to learn from peers with diverse strengths, thus promoting cognitive and social development simultaneously.

The decision to form heterogeneous groups was grounded in the understanding that diversity within learning teams fosters richer dialogue and more innovative problem-solving outcomes. Research by Vygotsky (1978) emphasized that cognitive growth occurs through social interaction, particularly when learners with varying levels of competence collaborate. By combining students of different proficiency levels, teachers encouraged peer tutoring and mutual support, creating a more inclusive learning atmosphere. The expectation was that this structure would minimize passive participation and stimulate a balanced exchange of ideas during group discussions.

In addition to group restructuring, the second cycle integrated project-based assignments to extend learning beyond routine classroom exercises. Project-based learning (PBL) provided students with authentic tasks that required sustained inquiry, critical thinking, and creativity. Each group was assigned a project aligned with real-world mathematical applications, compelling students to plan, collaborate, and present outcomes collectively. According to Thomas et al. (2021), PBL not only improves engagement but also cultivates essential 21st-century competencies such as problem-solving, communication, and teamwork.

During implementation, teachers observed a noticeable transformation in classroom dynamics. Students became more active and cooperative, with most groups demonstrating improved collaboration and initiative. Learners appeared more responsible for their tasks, showing enthusiasm in sharing progress and discussing emerging challenges. The atmosphere shifted from teacher-centered instruction to a learner-centered environment characterized by interaction, negotiation, and mutual support. This transition reflects constructivist principles where students construct meaning through collaboration and reflection rather than through passive reception of knowledge.

Data collected through classroom observation and reflective journals indicated a significant increase in student participation. Unlike the first cycle, where engagement was uneven, participation became more evenly distributed across groups. Students who were previously reluctant to speak began contributing to discussions and decision-making processes. Teachers attributed this improvement to the heterogeneous grouping, which allowed less confident students to learn from their peers in a supportive, non-threatening context. This outcome aligns with findings by Kaur and Ibrahim (2023), who reported that group diversity enhances participation and social learning outcomes.

Despite these positive developments, the implementation of project-based assignments presented new challenges, particularly regarding time management. Teachers and students struggled to balance the depth of inquiry required for the projects with the constraints of the instructional schedule. Some groups found it difficult to complete tasks within the allocated time, leading to incomplete outputs or rushed presentations. This issue resonates with observations by Mills and Nguyen (2022), who noted that time constraints are a common obstacle in applying PBL approaches effectively in traditional classroom settings.

Teachers recognized that managing time effectively in project-based learning requires careful scaffolding and phased task distribution. In subsequent lessons, they began to allocate milestones and mini-deadlines to help students organize their work systematically. Teachers also introduced short reflective checkpoints, allowing students to evaluate progress and adjust strategies collaboratively. These adaptive measures sought to sustain engagement while ensuring task completion within the academic timeframe. Such iterative adjustments demonstrate the core principle of action research, where each cycle informs practical improvement.

Another reflection emerging from the second cycle concerned the need for clearer role distribution within groups. Although participation had increased, overlapping responsibilities sometimes caused confusion and inefficiency. To address this, teachers planned to establish structured roles—such as coordinator, recorder, presenter, and evaluator—in the next cycle. This measure aimed to improve accountability and ensure that each member contributed meaningfully. Studies by Gillies (2020) highlight that explicit role designation enhances cooperative learning by preventing dominance and promoting balanced participation.

From a pedagogical perspective, the second cycle demonstrated the potential of integrating social constructivist and experiential learning principles in improving classroom engagement. The combination of heterogeneous grouping and project-based learning allowed students to experience mathematics as a living, applicable discipline rather than a set of abstract procedures. Moreover, it fostered interpersonal communication, adaptability, and reflective habits—skills essential for lifelong learning. Teachers noted that while logistical challenges persisted, the overall classroom climate became more collaborative and student-driven.

In conclusion, the second cycle produced substantial improvements in both student engagement and learning behavior compared to the first phase. The introduction of heterogeneous groups and project-based assignments successfully increased interaction and participation, though it also revealed practical constraints in time management and task coordination. These insights will inform the design of the third cycle, where teachers plan to refine group role allocation, provide clearer timelines, and strengthen monitoring mechanisms. The ongoing reflective process underscores the iterative nature of professional learning and continuous pedagogical enhancement.

In the third cycle, teachers prepare a more structured schedule, prepare evaluation instruments, and emphasize the active participation of each group member. Observations show that students are more disciplined, participatory, and learning outcomes have increased significantly. Final reflections prove that the Kemmis and McTaggart models are effective as a tool for continuous improvement.

In the third cycle, teachers implemented a more refined instructional framework informed by the reflections and outcomes of the previous cycles. The primary focus of this stage was to strengthen structure, accountability, and continuous evaluation. Teachers prepared a detailed lesson schedule that clearly outlined learning objectives, time allocations, and specific milestones for each group task. This structured approach was designed to ensure that project activities remained aligned with curricular goals while maintaining a balanced pace of implementation.

In response to the time management challenges identified in the second cycle, the new schedule introduced segmented timelines and intermediate checkpoints. Each group was required to submit progress updates at defined intervals, allowing teachers to provide formative feedback and redirect efforts where necessary. Such planning reflects the principles of instructional scaffolding, ensuring that students receive adequate support throughout their learning process while still maintaining independence. According to Anderson and Kim (2024), structured pacing in collaborative learning improves task completion and minimizes off-task behavior.

Another critical improvement during the third cycle was the preparation and implementation of comprehensive evaluation instruments. These instruments included rubrics assessing cognitive, affective, and social dimensions of learning. Teachers employed both formative and summative evaluations to measure progress not only in content mastery but also in teamwork and communication skills. This holistic approach to assessment is consistent with Biggs and Tang’s (2022) concept of constructive alignment, where assessment criteria are explicitly linked to intended learning outcomes and teaching activities.

The teachers also emphasized the importance of active participation from every group member. Building upon insights from earlier cycles, group roles were now more explicitly defined, and peer assessment was introduced to ensure mutual accountability. Each member’s contribution was evaluated both individually and collectively, thereby reducing social loafing and encouraging equitable engagement. As highlighted by Le et al. (2023), incorporating peer evaluation mechanisms enhances fairness and motivates all students to contribute effectively within collaborative settings.

Observations conducted during classroom sessions revealed a significant transformation in students’ behavior and interaction patterns. Students appeared more disciplined in managing time, adhering to deadlines, and following group protocols. The sense of responsibility among students increased markedly, as they realized that their individual contributions directly affected their group’s overall evaluation. Teachers noted that classroom discussions became more focused, and peer communication demonstrated greater depth and coherence. These findings align with Bandura’s (1997) theory of self-efficacy, suggesting that clear structure and feedback enhance students’ confidence in performing academic tasks.

The implementation of structured scheduling and evaluation tools also contributed to an observable improvement in learning outcomes. Assessment data showed a measurable increase in students’ achievement scores compared to previous cycles. Students demonstrated higher levels of conceptual understanding, problem-solving ability, and reflective thinking. Teachers attributed these gains to the increased consistency in learning activities and the continuous monitoring process embedded in the third cycle. These outcomes support Garrison and Vaughan’s (2021) assertion that well-structured, feedback-oriented learning environments foster deeper cognitive engagement.

Additionally, classroom climate showed notable progress toward a more collaborative and positive culture. Students displayed higher levels of enthusiasm, confidence, and mutual respect. They engaged in constructive dialogue, provided peer feedback, and took ownership of their learning process. Teachers observed that the balance between teacher guidance and student autonomy was now effectively achieved. This development illustrates the transition from teacher-centered to learner-centered pedagogy, a hallmark of sustainable instructional improvement under the Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) model of action research.

The reflective phase of the third cycle emphasized evaluating not only the students’ progress but also the teachers’ professional growth. Teachers reported enhanced understanding of classroom dynamics, assessment design, and facilitation techniques. The iterative process of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting enabled them to refine their pedagogical practices continuously. As Burns (2020) argues, the cyclical model of action research empowers educators to become researchers of their own classrooms, bridging the gap between theory and practice.

The cumulative findings from all three cycles demonstrate that systematic reflection and structured intervention can lead to substantial improvements in both teaching quality and learning outcomes. The integration of structured planning, collaborative learning, and reflective assessment resulted in more participatory, disciplined, and self-regulated students. Furthermore, teachers gained practical insights into managing time, designing effective evaluations, and nurturing collaborative engagement. These findings reinforce the central premise that effective teaching evolves through continuous inquiry and adaptation.

The final reflections of this study confirm that the Kemmis and McTaggart action research model serves as a powerful tool for continuous pedagogical improvement. By providing a flexible yet systematic framework for reflection and innovation, the model enabled teachers to identify problems, implement contextually relevant solutions, and evaluate their impact. The iterative nature of the model facilitated meaningful transformation in classroom culture and learning performance. Consequently, the research concludes that applying this model supports sustainable professional development and promotes active, student-centered learning environments.

3.1.7. Comparison with Other PTK Models

The results of the study show that the Kemmis and McTaggart models are more practical than the Kurt Lewin model which is too simple, or the

John Elliot model which tends to be complicated. Compared to the

Dave Ebbutt and Hopkins model, the

Kemmis and McTaggart model is more flexible because teachers can adapt actions according to the needs of the class without losing the systematics of the cycle. [

11,

13]

Various models of Classroom Action Research (CAR) have been developed to guide teachers in systematically improving educational practices, each with its unique characteristics. The Kurt Lewin model, often considered the origin of action research, is recognized for its simplicity and focus on a linear cycle of planning, action, and evaluation. While its straightforward approach makes it easy to implement, some scholars argue that its simplicity limits adaptability to complex classroom dynamics. Conversely, the John Elliot model offers a more elaborate framework with multiple interconnected stages, making it comprehensive but potentially complicated for teachers to apply in real-time classroom settings. The complexity of Elliot’s model can pose challenges, particularly for educators without extensive research experience or support systems.

The Dave Ebbutt and Hopkins models attempt to balance structure and flexibility, offering detailed cycles that emphasize reflection and evaluation. These models provide teachers with systematic guidance while still allowing some adaptation to classroom contexts. However, despite their structured nature, teachers may find certain stages rigid, limiting the ability to respond spontaneously to evolving student needs. Implementation often requires extensive documentation, formal reporting, or procedural adherence, which may reduce the immediacy of interventions. Therefore, while these models offer methodological rigor, they may not always align with the dynamic and fluid realities of classroom practice.

In contrast, the Kemmis and McTaggart model offers a flexible yet systematic framework that integrates the advantages of previous models while mitigating their limitations. Teachers following this model engage in spiral cycles of planning, action, observation, and reflection, which are iterative and adaptable to specific classroom contexts. Flexibility allows educators to modify action plans, instructional strategies, or assessment methods based on observed student needs without disrupting the overall systematics of the cycle. This adaptability ensures that interventions remain relevant, responsive, and evidence-based, even when unexpected challenges arise. Research indicates that teachers value the Kemmis and McTaggart model for its balance of structure and freedom, which supports both professional autonomy and accountability.

Another advantage of the Kemmis and McTaggart model is its emphasis on collaboration and reflective practice throughout the cycle. Teachers can involve colleagues, students, or administrators in planning, observing, and evaluating actions, fostering a shared sense of responsibility for learning outcomes. Reflection at the end of each cycle ensures that insights from each intervention inform subsequent actions, promoting continuous improvement. Unlike rigid models, the Kemmis and McTaggart framework encourages teachers to experiment, adapt, and refine strategies iteratively. This combination of flexibility and systematics makes it particularly suitable for diverse classrooms with varying student characteristics, resources, and institutional constraints.

Overall, while simpler models like Lewin’s provide ease of use and more complex models like Elliot’s ensure comprehensive coverage, the Kemmis and McTaggart model strikes a practical balance between flexibility, collaboration, and systematic inquiry. Its spiral cycle design allows teachers to remain responsive to real-time classroom needs while maintaining methodological rigor. Teachers can implement context-specific interventions, observe outcomes, and reflect on results, adapting their approaches without losing the coherence of the research process. Consequently, the model not only improves instructional quality but also fosters professional growth, research literacy, and adaptive expertise among educators. Its design exemplifies how CAR can be both structured and flexible, providing practical utility across varied educational contexts.

This model also emphasizes collaboration between teachers, students, and the school. Collaboration is the key to success, because teachers not only take actions on their own, but also discuss with peers to design more appropriate learning strategies.

In addition to the Kemmis and McTaggart models, there are several other PTK models that are also widely used, including: [

11,

13]

-

Model Kurt Lewin

It is an initial model of PTK which consists of four steps: planning, action, observation, and reflection.

This model is simple, but it is the basis for the development of other models.

-

Model John Elliot

More detailed than the Lewin model.

Each cycle consists of three to five actions (actions), which allows improvements to be made in more detail.

-

Model Dave Ebbutt

Improved the Kemmis and Elliot models.

Emphasizing that the action-reflection spiral should be described more flexibly, so that teachers can adjust learning strategies according to the classroom situation.

-

Model Hopkins

Emphasizing the importance of construction planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation.

The process is carried out in a more systematic manner, starting from initial analysis to reporting.

In addition to the Kemmis and McTaggart model, several other models of Classroom Action Research (CAR) or PTK are widely implemented in educational settings, each offering distinct approaches to improving teaching and learning. The Kurt Lewin model is considered the foundational framework of PTK, consisting of four sequential stages: planning, action, observation, and reflection. Its simplicity makes it accessible for teachers, particularly those new to action research, and provides a clear structure for systematic improvement. Despite its straightforward design, the Lewin model has served as the basis for the development of more sophisticated models, influencing subsequent approaches to reflective and collaborative classroom research. Its linear structure allows educators to focus on immediate classroom problems and implement straightforward interventions.

The John Elliot model offers a more detailed alternative to Lewin’s framework, breaking the research cycle into three to five discrete actions within each phase. This expanded structure allows for finer adjustments and more nuanced improvements in instructional strategies. Teachers can address multiple facets of learning challenges in a single cycle, systematically analyzing both process and outcome variables. Although this level of detail provides a comprehensive approach, it can also increase the complexity of implementation, particularly for teachers with limited experience in structured research methodologies. Nonetheless, Elliot’s model emphasizes iterative refinement, ensuring that each cycle of planning, action, observation, and reflection contributes to progressive improvement. The model underscores the importance of deliberate, evidence-based interventions for enhancing student learning outcomes.