1. Introduction

Bioceramics play a fundamental role in modern medicine due to their excellent biocompatibility, durability, and ability to interact positively with biological tissues. They are widely used in applications such as bone grafts, dental implants, and joint replacements, where their similarity to natural bone structure promotes healing and tissue integration [

1]. Unlike traditional materials, bioceramics can be engineered to be bioinert, bioactive, or even biodegradable, depending on the medical need, resulting in highly versatile. Their resistance to wear and corrosion also ensures long-term performance in the body, improving patients’ quality of life and reducing the need for repeated surgeries [

2]. Therefore, bioceramics are becoming increasingly important in regenerative medicine and drug delivery systems due to their potential applications in healthcare.

Both wollastonite (W) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) are two important types of bioceramics that have gained significant attention in biomedical therapies because of their excellent bioactivity and ability to support bone regeneration [

3]. Tricalcium phosphate promotes strong bonding with natural bone by forming a hydroxyapatite layer on its surface when in contact with body fluids, enhancing osteoconductivity. Wollastonite, on the other hand, is highly biocompatible and biodegradable, gradually dissolving in the body while stimulating new bone growth, making it ideal for bone grafts and scaffolds [

3,

4,

5]. When used individually or in composites, these bioceramics not only provide structural support but also actively participate in the healing process, accelerating bone repair and reducing recovery time. Their combined properties are essential in the development of advanced biomaterials for orthopedic and dental implants [

6].

Adding rare-earth ions to bioceramics like wollastonite and tricalcium phosphate can significantly enhance their biological and functional properties, making them more effective for medical purposes [

7,

8,

9]. Rare-earth ions such as cerium, europium, or gadolinium can improve bioactivity by stimulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and bone tissue formation [

10,

11,

12]. Some of these ions also introduce antibacterial properties, helping to reduce the risk of post-surgical infections [

13,

14]. Additionally, certain rare-earth ions provide luminescent or magnetic characteristics. The study of luminescence in bioceramics allows combining structural and therapeutic functions with advanced diagnostic capabilities. By incorporating luminescent elements into bioceramics enables, under specific light excitation, real-time tracking of implants and monitoring of their integration with bone tissue without invasive procedures, which is especially valuable for bioimaging [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Luminescence can also provide insights into the material’s microstructural properties, which directly affect its biological performance. In particular, the assessment of the optical polarization of luminescence in bioceramics provides information of the symmetry, orientation, and local environment of luminescent ions within the ceramic matrix [

19,

20]. By analyzing polarization, it is possible to determine how crystal structures, defects, and ion substitutions influence light emission, which in turn affects the efficiency and stability of luminescent properties. This knowledge is particularly valuable for designing bioceramics with controlled optical responses.

In this work, Neodymium doped wollastonite–tricalcium phosphate (W–TCP:Nd) coatings were fabricated on the surface of calcium zirconate-calcium stabilized zirconia (CZO–CSZ) eutectic substrates by combining dip coating and laser floating zone (LFZ) techniques. The study aims to investigate the relationship between the microstructural anisotropy induced by directional solidification and the polarization dependence of the optical emission of Nd³⁺ ions. Microstructural and compositional analyses were performed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), while micro-Raman spectroscopy was employed to assess the degree of crystallinity and possible orientation effects. Optical emission spectroscopy under controlled excitation and detection polarization was used to examine the behavior of the 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition and 4F3/2→4I11/2 transitions of Nd³⁺ ions. The correlation between vibrational and optical features allowed determining the origin of the observed anisotropy, demonstrating that the LFZ technique enables control over the optical polarization response of bioceramic coatings for potential use in photonic and biomedical therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

Both dip coating and laser floating zone (LFZ) techniques were combined to manufacture the Neodymium doped W-TCP coating. In the first place, a ceramic solution was prepared with Ethanol (44.49 wt%), Beycostat C213 (0.42 wt%), Polyvinyl Butyral, PVB, (12.72 wt%), and 42.37 wt% of a powder mixture including Wollastonite (Aldrich, 99%) and Tricalcium Phosphate (Carlo Erba Reagenti, Italy, Analytical Grade) in the eutectic composition, 80-20 mol% respectively, and 1wt% N2O3 (Aldrich, 99%).

Rods of CZO-CSZ eutectic composite used as the core and previously prepared by the LFZ technique were dipped and withdrawn at a constant rate in the ceramic solution allowing the control of the layer thickness, and subsequently sintered at 1200 °C. Finally, directional solidification was carried out by means of the LFZ technique. The fundamentals of this technique can be consulted elsewhere [

21,

22]. Laser power and growth rate were suitably adjusted to induce surface cladding avoiding the alloying with the core [

23]. Specifically, the growth rate was set at 100 mm/h which assured the fabrication of a glass-ceramic coating [

24]. Samples were cut and polished to be prepared for microstructural and optical characterization. After polishing, samples were annealed at 750°C for 12 h to relieve the stress which may be induced during the preparation process.

Morphology and semiquantitative composition characterization in the samples were performed both in transversal and longitudinal sections by means of Field Emission Electron Microscopy (FESEM, model Carl Zeiss MERLIN) with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) detector.

Luminescence characterization was carried out at room temperature by using a home-made microscope pumping the sample at 800 nm by a single mode fibre coupled diode. The backscattered light was delivered to a Spectrometer (SR303i-B, Andor, Belfast, Northern Ireland) equipped with a thermoelectric-cooled CCD detector (Newton 920, Andor, Belfast, Northern Ireland). Two polarizers were placed in the optical setup to determine the optical properties as a function of the polarization. The first polarizer, Pex, was placed to set the laser excitation source as parallel () or perpendicular () to the growth direction for which the samples were manufactured. The second polarizer, Pem, was placed to analyse the luminescence as a function of the rotation angle with respect the excitation laser source from 00 to 90 degrees, clockwise, so that the stablished convention in this work was to denote parallel to the excitation source as Pem 00 and perpendicular as Pem 90.

Micro-Raman characterization was performed by using a confocal microscope coupled to a WITec Alpha 300 system. A cw laser with emission at 488 nm was used to excite the sample.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructural Characterization

A detailed study of the microstructural characterization of the coating fabrication can be found in a previous publication [

23]. As a summary, the CZO-CSZ eutectic composite was firstly produced in cylindrical shape by the LFZ technique at a growth rate of 200 mm/h. This eutectic composite was made up of two cubic phases, solidified in lamellar distribution. Next, the W-TCP:Nd coating was manufactured in two stages. The first one was the use of the dip coating technique to adhere the ceramic solution to the core. For this purpose, the CZO-CSZ rod was dipped and withdrawn 10 times at a constant rate of 3 mm/s and then it was sintered at 1200 °C for 12 h to densify and improve the adherence. Next, a CO

2 laser was focused onto the coating and pulled down to induce both the melt and directional solidification. In this bioceramic eutectic composite the growth rate can be adjusted to produce crystals, glass-ceramic or glasses [

24]. For this study, the growth rate was set at 100 mm/h which induces the formation of a glass-ceramic sample.

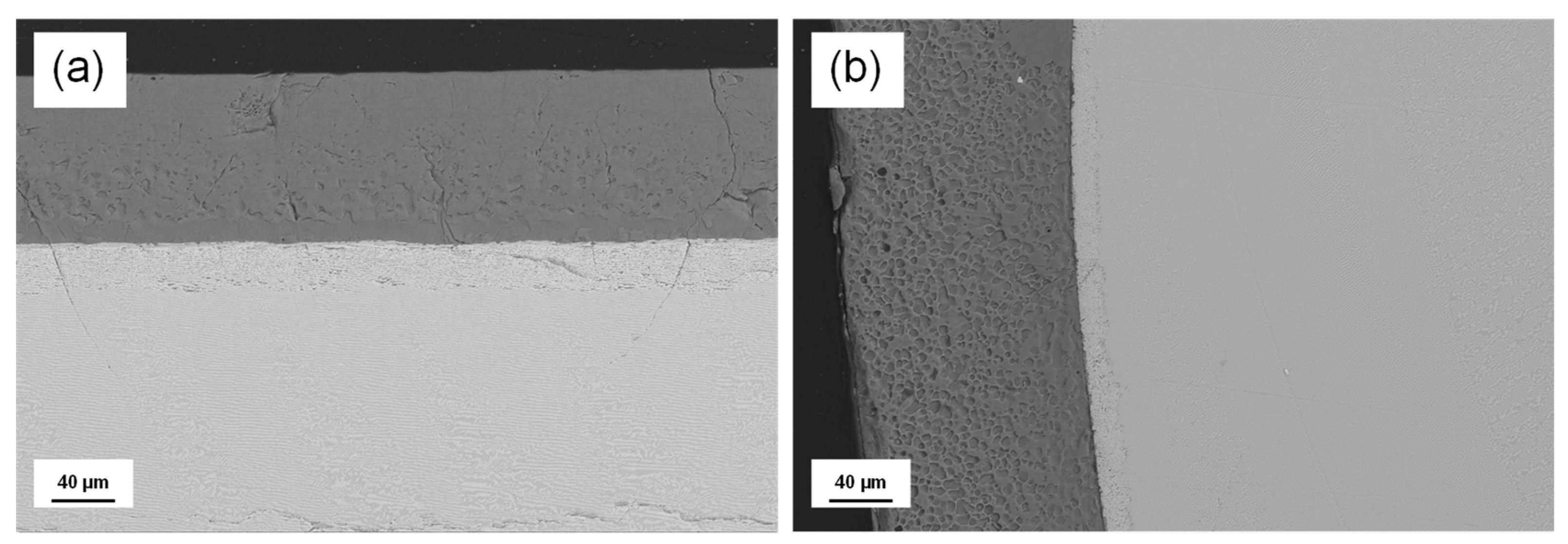

Figure 1 shows SEM micrographs of the longitudinal (a) and cross-section views (b) of the W-TCP:Nd coating cladded to the CZO-CSZ core. The clear contrast represents the CZO-CSZ core whereas the W-TCP:Nd coating is represented by the dark contrast. Both micrographs showed a clean interface confirming that the low laser power used to melt the coating minimized the dilution of the bioceramic to the eutectic core.

Table 1 shows the semiquantitative compositional analysis performed on the layer confirming a composition close to the theoretical, also included in the table.

3.2. Optical Characterization

The most important emission bands for the Nd

3+ ions are those obtained by exciting the sample in resonance with the

4I

9/2→

4F

5/2,2H

9/2 absorption band. The laser transition corresponding to the

4F

3/2→

4I

11/2 transition is commonly studied because of its potential applications in the field of infrared optical amplification [

25,

26]. In addition, the features of the fluorescence spectra for this laser transition have also been studied for the evaluation of the local structure surrounding the Nd

3+ ions and the covalency of the Nd-O bond in glass matrixes [

27]. Nevertheless, the 4f electrons of Nd³⁺ are strongly shielded by the outer 5s,5p orbitals, so the energies of the

4F

3/2 and

4I

11/2 levels are barely perturbed by the crystal field, resulting that the emission wavelength placed at around 1060 nm is considered as host-insensitive emission line [

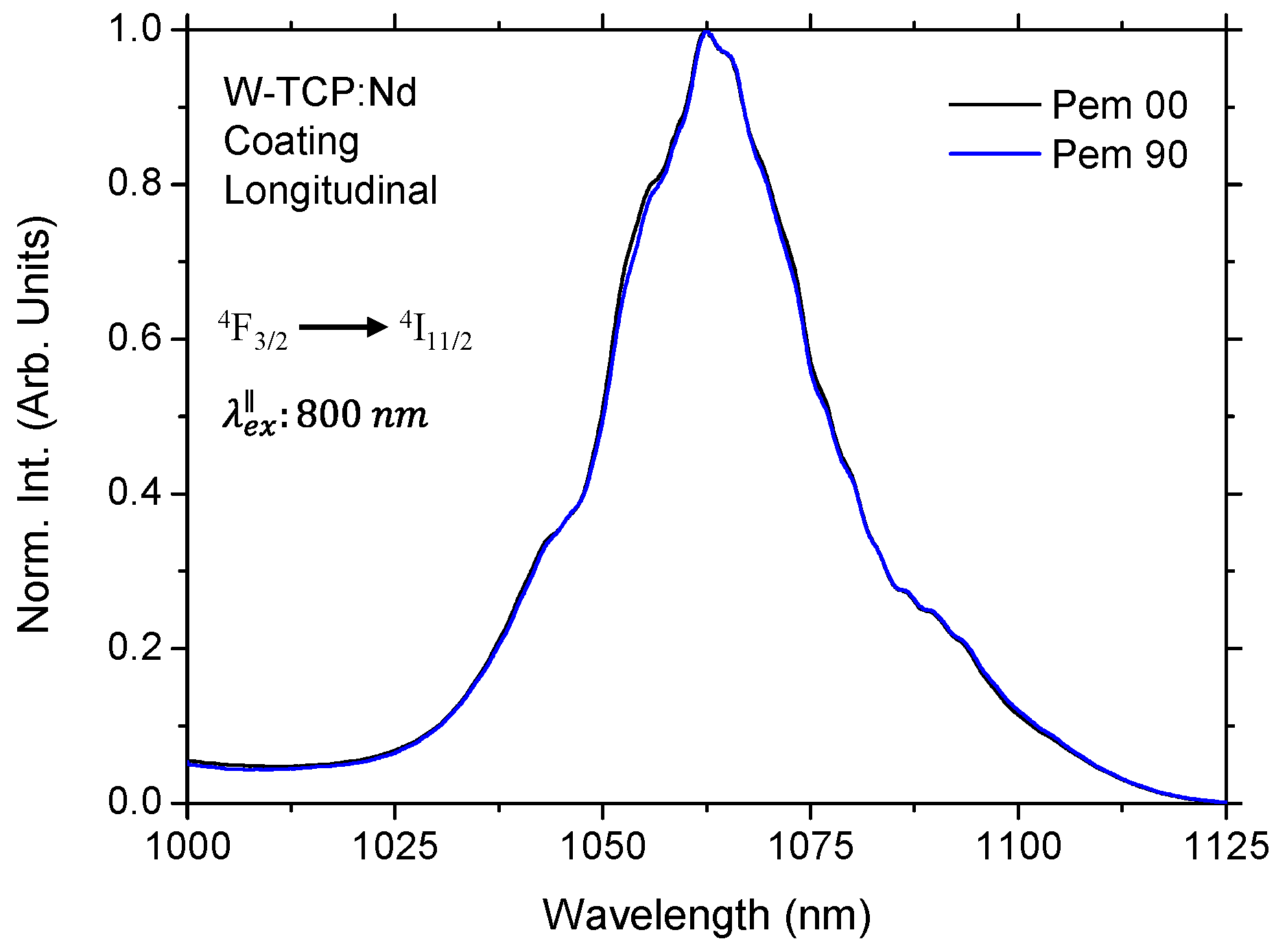

26]. Furthermore, this transition is relatively isotropic with little dependence on polarization, as shown in

Figure 2, in which the steady-state emission in the longitudinal section of the W-TCP:Nd coating for polarizations parallel (Pem00) and perpendicular (Pem90) to the excitation source showed similar characteristics. The same behavior was observed for the transversal section of the coating and for perpendicular excitation.

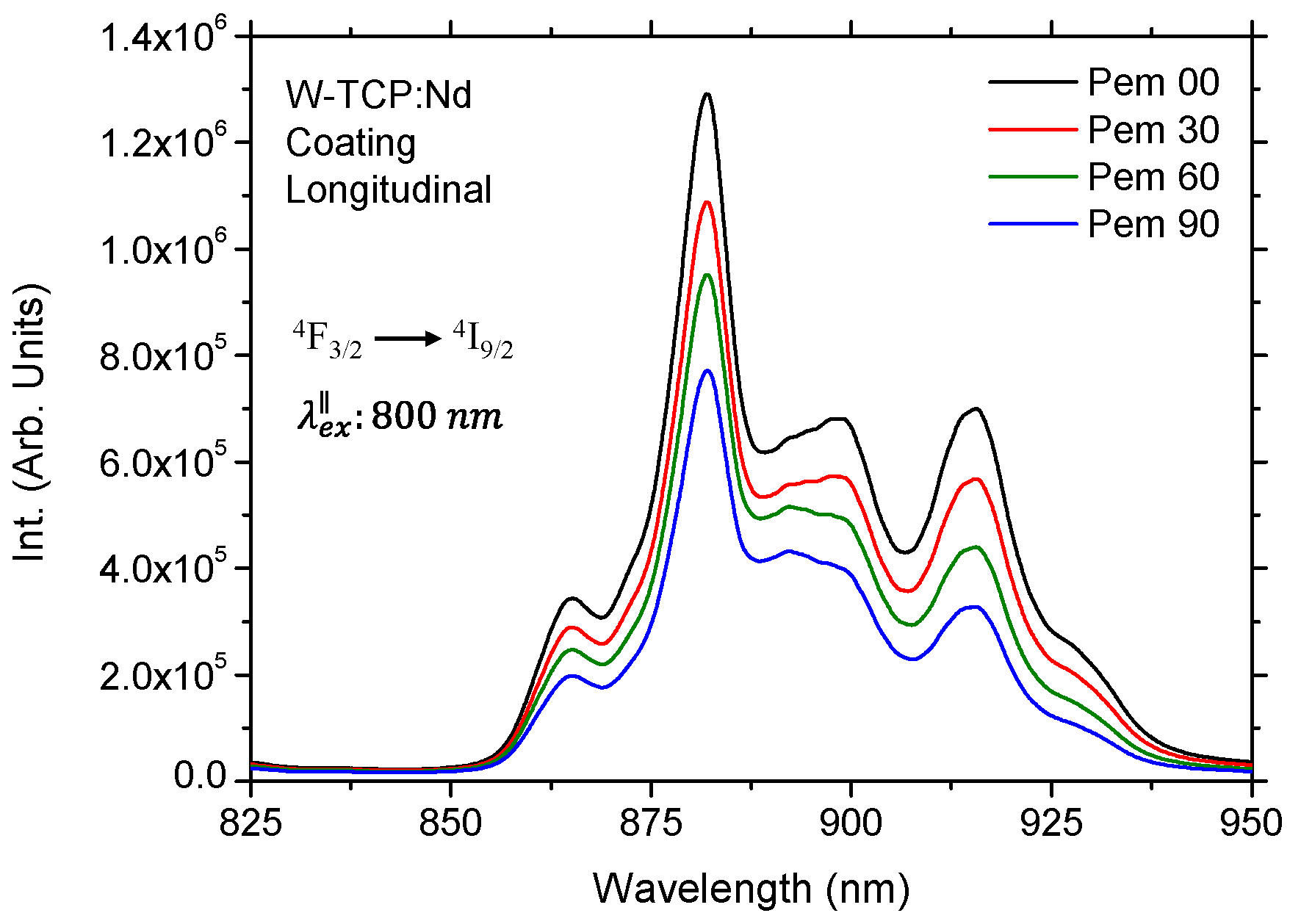

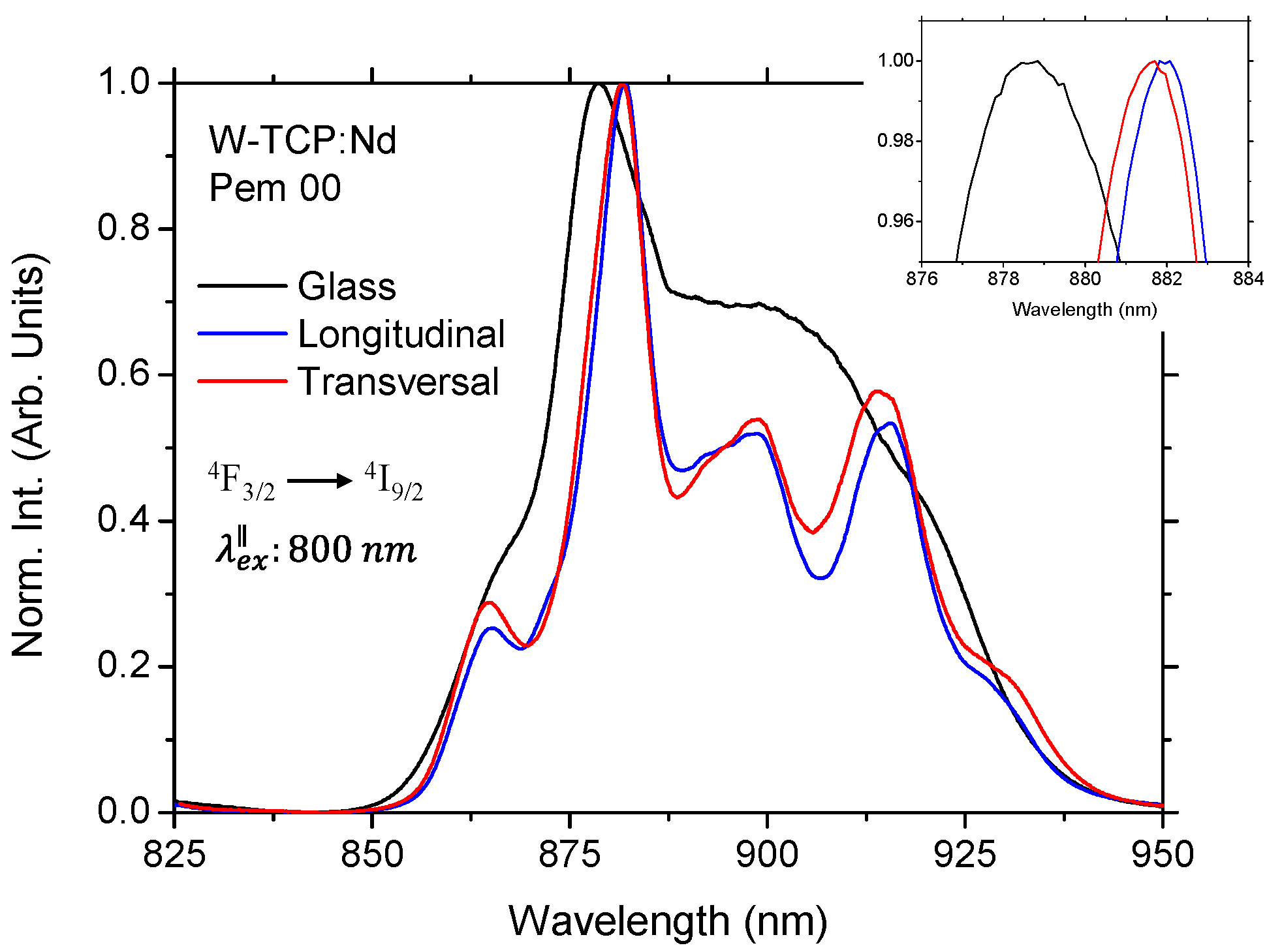

On the contrary, the emission band placed at 870 nm corresponding to the

4F

3/2→

4I

9/2 transition can suffer strong Stark splitting due to the crystal field and is strongly dependent on both the symmetry and the host matrix [

26]. Consequently, the features of the Stark sublevels are host sensitive. In addition, the transition probabilities depend on the orientation of the light´s electric field vector, resulting that both the intensity and the spectral position of the Stark sublevels are polarization dependent. This behavior was observed in the emission properties of the coating in both longitudinal and transversal sections for both excitation configurations. As an example,

Figure 3 shows the emission spectra of the longitudinal section for emission polarization placed at 0, 30, 60 and 90 degrees to the excitation laser source, which in this case was parallel. It was observed that the emission intensity showed at least four main components, with the band located at 882 nm showing the maximum intensity. Furthermore, the rotation in the polarization gave rise to a decrease in the intensity of the emission spectra so that it was maximal for the parallel polarization whereas it decreased as the polarization was rotated, reaching the minimum for the perpendicular polarization. In addition, the features of the Stark components also changed with polarization, as can be observed in the normalized emission spectra shown in

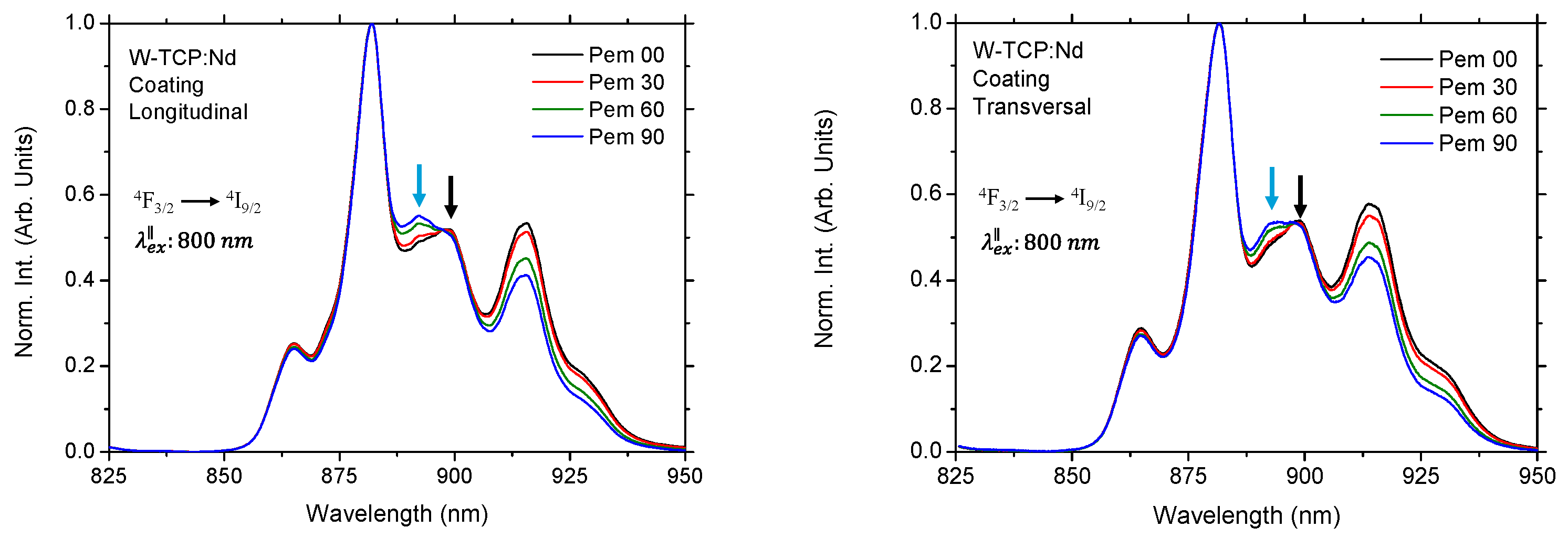

Figure 4 for both longitudinal (left) and transversal section (right) of the coating. For comparison purposes, normalization was performed accounting for the maximal intensity reached for the band placed at 882 nm. It was observed that as the emission polarization was rotated from parallel to perpendicular the intensity of the bands placed at around 865 nm and 915 nm decreased whereas the intensity of the band placed around 898 nm increased. Moreover, a shift to shorter wavelengths was observed in the peak position for the component placed at around 898 nm, changing from 898.24 nm to 892.33 nm for parallel and perpendicular, respectively. The position of these peaks was pointed out with an arrow in the Figures. This shift was also observed in the other two components at 915 nm and 865 nm but in these cases, it was lower than 1 nm. The same behavior was observed for perpendicular excitation.

Finally, a comparison of the emission spectra for both longitudinal and transversal sections of the W-TCP:Nd coating and a W-TCP:Nd glass sample was performed. As an example,

Figure 5 shows the normalized emission spectra for the parallel polarization for the 3 samples. It can be observed that the crystalline nature of the coating was clearly revealed, since the splitting of the Stark components resulted in a more complex emission spectrum. Furthermore, by comparing the glass and the coating a 3 nm shift in the peak position of the highest intensity component was observed. Moreover, there was also a spectral shift when compared the longitudinal and transversal sections for which the maximum intensity component was placed at 881.6 nm and 882.0 nm, respectively. The inset in

Figure 5 shows these spectral shifts in more detail. In addition, it was found significant spectral differences in the Stark components of both sections. The same characteristics were observed for the other polarization configurations as for the emission as for the excitation polarization.

3.3. Micro-Raman Characterization

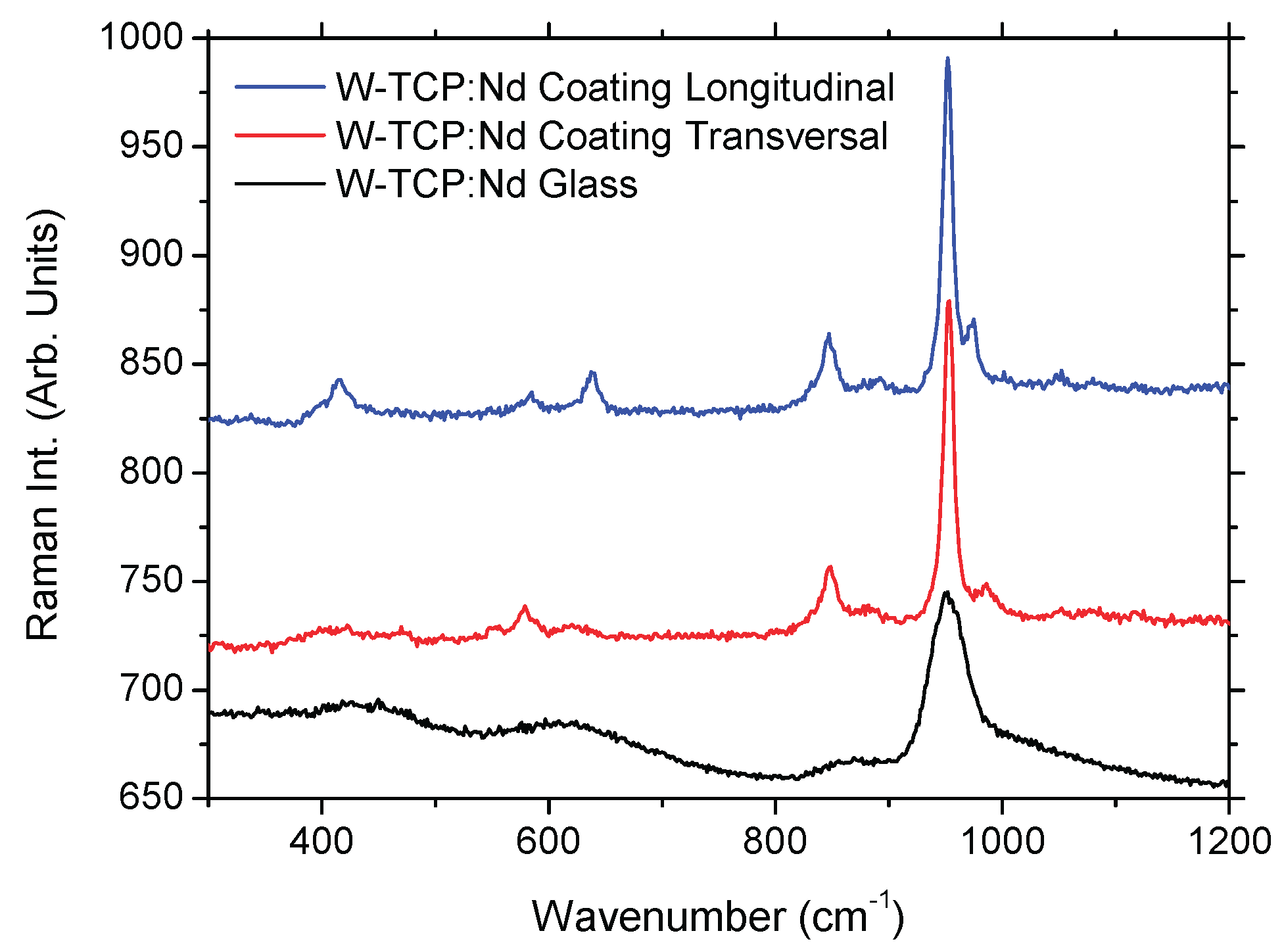

To study the crystalline nature of the coating µ-Raman characterization was carried out and compared to the W-TC:Nd glass. In addition, aiming at clarifying the findings previously described in the luminescence properties of the longitudinal and transversal sections of the coating, Raman characterization was also performed in these sections.

Figure 6 shows Raman spectra of the glass and both coating sections in the wavenumber region 300-1200 cm

-1. The position of peaks and bands is shown in

Table 2. Firstly, it can be observed that the glass sample showed a simple Raman spectra made up of few broad bands, characteristics of an amorphous silicate structure. The bands, centred at around 430 cm

-1, 623 cm

-1, 863 cm

-1, and 950 cm

-1, are broad and relatively low in intensity, consistent with disordered glassy materials lacking long-range order. Coating spectra showed narrow bands with higher relative intensity at similar positions to the glass but also some new sharp peaks and broad bands, suggesting higher degree of structural ordering or differences in bonding environments, possibly due to orientation effects and/or the presence of crystalline phases within the coating.

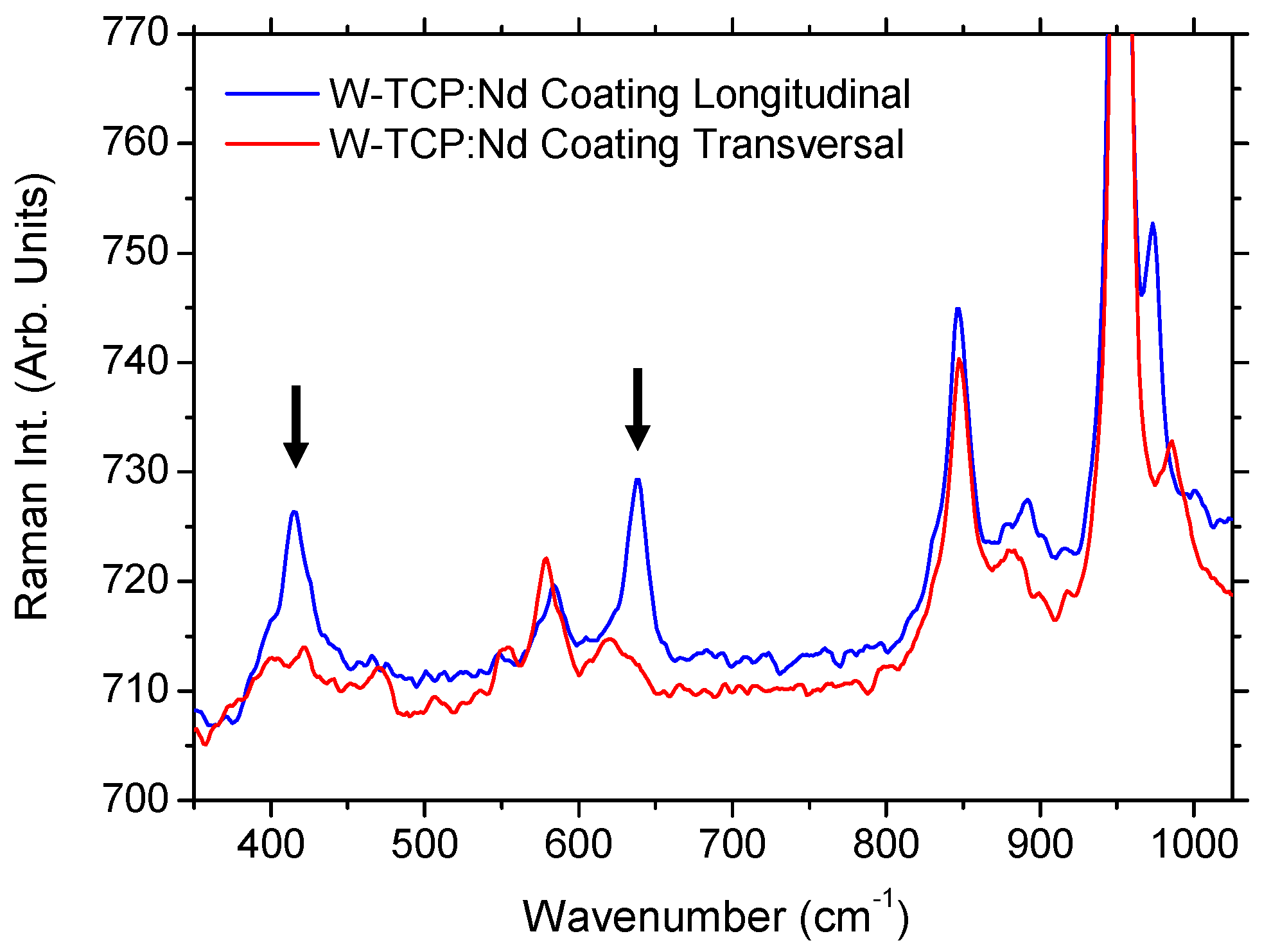

A more detailed comparison of the main bands of both coating sections, depicted in

Figure 7, showed clear spectral differences. The longitudinal section showed peaks with strong intensity at 415.2 cm

-1 and 639.5 cm

-1, pointed out by an arrow in

Figure 7. The first one was not present in the transversal section, and the second one suffered a decrease in intensity and a red shift to lower wavenumber in the transversal section. This decrease was accompanied by an increase in the intensity of the peak placed at 578.8 cm

-1, resulting in higher relative intensity and red shift when compared to the longitudinal section, together with the appearance of a small broad band centered at around 552.2 cm

-1. A red shift was also produced in the position of the band placed at 891.4 cm

-1. On the contrary, the peak position of the band placed at 972.7 cm

-1 in the longitudinal spectrum showed a slight blue shift to higher wavenumber when compared to the transversal one. The new or enhanced bands appeared and the opposing shifts in the peak positions suggest different crystallographic orientations and anisotropic stress along the growth direction induced during the directional solidification process.

5. Conclusions

- Neodymium doped bioactive W-TCP coatings were successfully produced by the combined use of dip coating and LFZ techniques, resulting in homogeneous and well-adhered glass-ceramic layers on the CZO–CSZ eutectic core.

- Raman spectra revealed new vibrational modes and distinct peak shifts between longitudinal and transversal sections. The longitudinal section exhibited sharper and more intense peaks, while the transversal section showed broader features and red-shifted bands, indicating anisotropic stress and crystallographic orientation along the growth direction.

- The 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition presented Stark splitting and strong polarization dependence in both emission intensity and spectral position, whereas the 4F3/2→4I11/2 transition remained nearly isotropic.

- The optical anisotropy observed in the luminescence is directly correlated with the microstructural anisotropy induced by the directional solidification process, confirming the role of the LFZ technique in controlling orientation and optical response.

- The Nd-doped W-TCP coating combines bioactive ceramic behavior with controlled optical anisotropy, making it a promising candidate for multifunctional biophotonic devices, including optical tracking, sensing, and diagnostic platforms.

Author Contributions

Methodology, all authors; validation, all authors; investigation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, J.I.P. and D.S.; writing—review, all authors; funding acquisition, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by Gobierno de Aragón, Research Group T02_23R, Procesado y Caracterización de Cerámicas Estructurales y Funcionales, PROCACEF, and COST Action CA21159, Understanding interaction light – biological surfaces: possibility for new electronic materials and devices.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the use of Servicio de Microscopia Electrónica (Servicios de Apoyo a la Investigación), Universidad de Zaragoza.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hench L.L.; Wilson J. An introduction to bioceramics, 2nd ed.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2013.

- Rahaman, M.N.; Yao, A.; Bal, B.S.; Garino, J.P.; Ries, M.D. Ceramic biomaterials: Properties, state of the art, and future prospectives. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47(20), 28229–28251. [CrossRef]

- De Aza P.N.; Guitian F.; de Aza S. Bioeutectic: a new ceramic material for human bone replacement. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 1285-1291. [CrossRef]

- De Aza P.N.; Guitian F.; de Aza S. A new bioactive material which transforms in situ into hydroxyapatite. Acta Materialia 1998, 46, 2541-2549. [CrossRef]

- De Aza P.N.; Luklinska Z.B.; Anseau M.R.; Hector M.; Guitian F.; De Aza S. Reactivity of a wollastonite-tricalcium phosphate Bioeutectic® ceramic in human parotid saliva. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 1735-1741. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Roohani-Esfahani, S.I.; Zhang, W.; Lv, K.; Yang, G.; Ding, D.; Zou, D.; Cui, H.; Zreiqat, H.; Jiang, X. Wollastonite/TCP composites for bone regeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerâmica 2022, 69, 1-14.

- Zheng B, Fan J, Chen B, Qin X, Wang J, Wang F, Deng R, Liu X. Rare-Earth Doping in Nanostructured Inorganic Materials. Chem Rev. 2022,122, 5519-5603. [CrossRef]

- Neacsu, I.A.; Stoica, A.E.; Vasile, B.S.; Andronescu, E. Luminescent Hydroxyapatite Doped with Rare Earth Elements for Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 239. [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, N.; Moradi, A.; Sharifianjazi , F.; Tavamaishvili , K.; Bakhtiari , A.; Mohammadi , A. A Review of Samarium-Containing Bioactive Glasses: Biomedical Applications. J. compos. compd. 2025, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zambon, A.; Malavasi, G.; Pallini, A., Fraulini, F.; Lusvardi, G. Cerium Containing Bioactive Glasses: A Review. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4388–4401.

- Gao J.; Feng, L.; Chen B.; Fu B.; Zhu, M. The role of rare earth elements in bone tissue engineering scaffolds - A review. Composites Part B: Engineering 2022, 235,109758. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yang, F.; Xue, Y.; Gu, R.; Liu, H.; Xia, D.; Liu, Y. The biological functions of europium-containing biomaterials: A systematic review. Materials Today Bio 2023, 19, 100595. [CrossRef]

- Li, Cheng.; Wei, H.; Li, Zulai; Wang, X. The influence of rare earth (La, Ce, and Y) doping on the antibacterial properties of silver ions. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2024, 675, 415648. [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Ymamoto, A.; Kazaana, A.; Nakano, Y.; Nojiri, Y.; Kashiwazaki, M.. Antibacterial, Antifungal and Nematicidal Activities of Rare Earth Ions. Biol Trace Elem Res 2016, 174, 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Lu, S.; Xing, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H. Rare-earth based materials: an effective toolbox for brain imaging, therapy, monitoring and neuromodulation. Light Sci Appl. 2022,11, 175. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B., Singh, S., Kumar, P. et al. Bifunctional Luminomagnetic Rare-Earth Nanorods for High-Contrast Bioimaging Nanoprobes. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32401.

- Yuan, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Liang, G. Inspired by nature: Bioluminescent systems for bioimaging applications. Talanta 2025, 281, 126821. [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.H.; Ben-Nissan, B. Calcium Phosphate Nanocoatings and Nanocomposites, Part I: Recent Developments and Advancements in Tissue Engineering and Bioimaging. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2249–2261. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, H., Zhou, C.; Yang, L.; Xu, J. Enhancement of the up-conversion luminescence performance of Ho3+-doped 0.825K0.5Na0.5NbO3-0.175Sr(Yb0.5Nb0.5)O3 transparent ceramics by polarization. Bull Mater Sci 2021, 44, 139. [CrossRef]

- Chaudan, E.; Kim, J.; Tusseau-Nenez, S.; Goldner, P.; Malta, O.L.; Peretti, J.; Gacoin, T. Polarized Luminescence of Anisotropic LaPO4:Eu Nanocrystal Polymorphs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9512–9517. [CrossRef]

- Llorca, F.J.; Orera, V.M. Directionally solidified eutectic ceramic oxides. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2006, 51(6), 711-809. [CrossRef]

- Ester F.J.; Sola D.; Peña J.I. Thermal stresses in the Al2O3-ZrO2(Y2O3) eutectic composite during the growth by the laser floating zone technique. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. 2008, 47, 352-357. [CrossRef]

- Sola, D.; Chueca, E.; Wang, S.; Peña, J.I. Surface Activation of Calcium Zirconate-Calcium Stabilized Zirconia Eutectic Ceramics with Bioactive Wollastonite-Tricalcium Phosphate Coatings. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 510. [CrossRef]

- Sola D.; Balda R.; Al-Saleh M.; Peña J.I.; Fernandez J. Time-resolved fluorescence line-narrowing of Eu3+ in biocompatible eutectic glass-ceramics. Optics Express 2013, 21, 6561–6571. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Imbusch, G.F. Optical Spectroscopy of Inorganic Solids; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023.

- Di Bartolo, B. Optical Interactions in Solids. 2nd ed; World Scientific, Singapore, 2010.

- Sola D.; Conejos D.; Martinez de Mendivil J.; Ortega SanMartin L.; Lifante G.; Peña J.I. Directional solidification, thermo-mechanical and optical properties of (MgxCa1-x)3Al2Si3O12 glasses doped with Nd3+ ions. Optics Express 2015, 23, 26356-26368. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).