1. Introduction

In the heart of quantum mechanics (QM) lies a series of “paradoxes”, which are fully described mathematically and surveyed experimentally, but nonetheless contradict common sense. These include (amongst others) the particle/field duality, which allows point-like entities to have field-like characteristics, as well as the notion that the spin of elementary particles is a type of angular momentum, even though the idea of the rotation of a point-like entity is nonsensical (i.e., it requires an infinite velocity).

This is not to say that elementary particles do not have both particle and wave characteristics, but rather to stress that these effects contradict common sense

in the context of the current formalism of QM. Many interpretations of QM exist, such as the Copenhagen [

1], De Broglie–Bohm [

2] and the Many Worlds [

3], but a comprehensive, intuitive picture of these phenomena is to some extend still absent. It is thus possible that to understand the aforementioned paradoxes in an intuitively comprehensive manner, one might have to move away from conventional pictures such as “particles” or “fields”

whatsoever and find another mental frame that is better suited for the task at hand.

Indeed, during the past few decades several theories tried to do just that, such as String/M-theory [

4] and Loop Quantum Gravity [

5]. Another theoretical approach that closely aligns with the perspective developed in this study is rooted in Quantum Information. This branch of theories suggests that spacetime may not be fundamental but rather an emergent phenomenon arising from more basic quantum informational principles—such as the quantum bit (qubit) or the act of quantum measurement [

6,

7,

8].

Here we will argue that the quantum properties such as spin should also be treated as emerging and that another mental frame, namely the

local area network (LAN), might allow us to visualize a particle/field entity and its spin,

without violating common sense [

9]. In more detail, here we will utilize the notion of the LAN (from the field of computer networks) to draw images that have the

seemingly paradoxical characteristics of the particle/field entity, while they relate to our everyday experience with these networks (

Section 2.1-

Section 2.2).

Further, we will follow this analogy and demand that

all particles are networks of communication nodes, called “átmita”. Each átmiton would have its individual “address” (similar to the notion of the IP address of computers in a LAN) and in this context each particle would exchange information with its counterparts through empty space via a single communication node, termed the “router”, utilizing a single communication protocol that defines the signal exchange method. What we perceive as

space would be the equivalent of the Internet (see

Figure 1a and

Section 2.1) and what we perceive as

time would be the multiples of the elementary step with which the network topology changes.

The advantage of this construct is that it requires only one species of “nodes” and one communication protocol, from which one would, in principle, derive the fundamental properties of empty space, as well as the characteristics of the elementary particles and their interactions (e.g., charges, masses, symmetries, etc).

In this work, we will first outline the basic properties of átmita and their interaction protocol, noting, when appropriate, possible alternative versions of them (

Section 3). Based on this model, a number of important results, notions and suggestions will be extracted, all stemming from answering the most fundamental question:

How can we place a LAN of átmita in Space? This question has two parts: 1) How is the LAN connected to Space? and 2) What addresses will the átmita of a particle/LAN occupy? In a sense, question (1) asks us to draw a picture like

Figure 1(a), while question (2) seeks to describe a picture like

Figure 1(b).

Turning to the first part of the question, note that it is not straightforward, as Space will be axiomatically assumed to have the topology of a perfect simple-cubic crystal (i.e., with no intrinsic holes and defects, see

Section 3) and only integer addresses (i.e., lattice points) are valid, so we can seemingly place the LAN’s router neither at a substitutional nor at an interstitial position.

By overcoming this impasse, it will be shown that placing a particle/LAN entity in Space creates an

effective curvature, as each particle acts as a “defect” on the lattice of Space (

Section 4.1), much like a crystalline defect in a condensed matter system. Following this notion, it will be argued that massive objects generate great amounts of such space-defects, due to all their internal interactions. These defects then diffuse in all directions by means of a random walk, with their net flow driven by a concentration gradient.

This mechanism will be suggested to be equivalent to the mass-generated curvature of general relativity (GR) [

10]. Indeed, the equivalency of the defect-diffusion effect and GR’s curvature notion will be demonstrated for the specific case of a spherical mass, as the Schwarzschild metric [

11] will be shown to be valid in the mass’ vicinity. Note, however, that GR is not linear and thus the general (in)compatibility of the two theories needs to be rigorously proven in another publication.

This result could be rather important, as – to the author’s best knowledge – this is the first time the Schwarzschild metric is reproduced in the context of discrete space and time. Moreover, this approach can be thought as complementary to other recent works, which indicate that topological defects (singularities) placed in empty space would give rise to a 1/r attractive force [

12,

13].

Turning now to the second part of the aforementioned question: To fully understand the implications of placing a LAN in Space, the addresses occupied by the LAN’s átmita also need to be defined. Resolving this issue requires an additional concept – that átmita have a finite internal memory – which has important consequences:

First, if each átmiton has a finite internal memory of size

M, then it can be argued that LANs of átmita exhibit the quantum mechanical wave-like characteristics. Indeed, in

Section 3.3 we will suggest that De Broglie’s formula is valid in this context, by demanding that

M is Plank’s constant

h translated to the natural units of Átmiton theory.

Second, in

Section 4.2 it will be detailed that, due to the átmita’s finite memory, the act of placing a LAN in Space results in

three fully symmetric and non-interacting versions of each particle type – termed

X-

Y- and

Z-bases. It will be argued that two of these bases correspond to

Dark Energy (DE) and the third (arbitrarily chosen to be the

Z-basis) to

matter (both regular and dark varieties). In other words, according to this work there are two fully symmetric and mutually non-interacting versions of the electron,

and

, in addition to the regular electrons (i.e.,

). The same also holds for all other particle types.

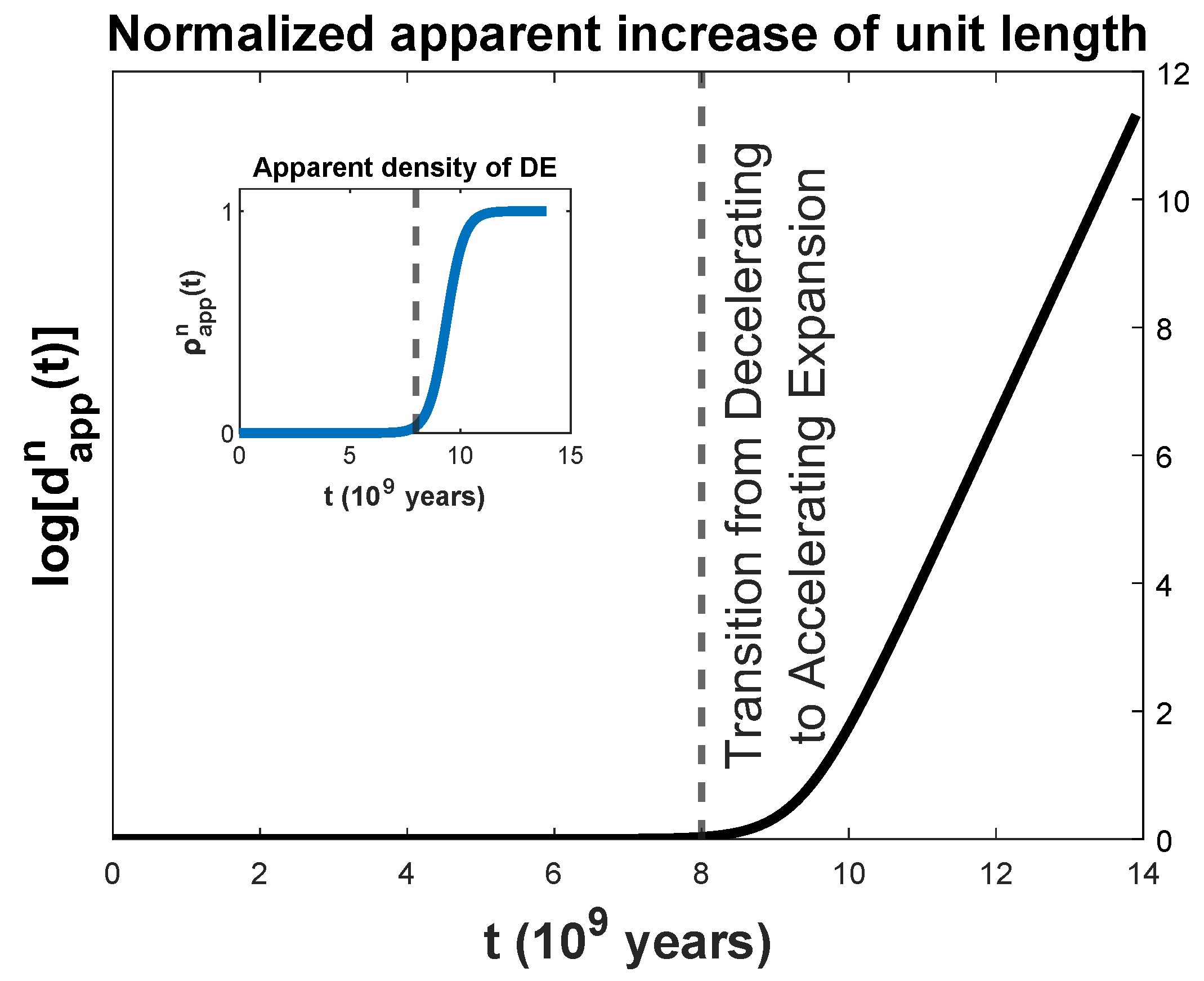

This model can be used to calculate the percentage of DE (at the limit of low redshifts) to be

, in excellent agreement with recent observations (see

Table 1). Note that this is a Quintessence-like model for Dark Energy [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], not a cosmological constant. Recent findings [

19], that suggest a non-zero cosmic birefringence angle

in the Plank 2018 [

20] data (albeit not yet with a 5

significance), as well as a coupling between supermassive black holes and DE [

21], further support this view.

Furthermore, the above model for DE offers another interesting possibility: Since the three bases (

X-

Y- and

Z) are fully symmetrical, it is conceivable for the router átmiton of a

Z-based particle to be able to temporarily rotate by 90° its local (internal) coordinate frame and turn the particle (for a short period) to one of its

X- or

Y-based counterparts (

Section 4.3). This way it can bypass a

Z-based obstacle, with which it will

not be interacting for the duration of its transformation to DE. The particle could now propagate

through the Z-based barrier and resurface as a regular matter particle on the other side. This proposed mechanism sounds very familiar: It has the qualitative characteristics of QM

tunneling.

However, if this is the case, then by symmetry DE particles should be able to tunnel by turning to their counterparts of the other two bases, i.e., by turning to regular matter with a 50% probability. Such tunneling DE particles would be (for the duration of the process) completely indistinguishable from their regular-matter counterparts, but from the point of view of a regular-matter observer they would appear out-of-nowhere and disappear as suddenly. Again, this possibility sounds very much like a known phenomenon, that of vacuum fluctuations.

This dual mechanism for tunneling and vacuum fluctuations could potentially explain the Vacuum Catastrophe and also provide a prediction for the vacuum particle density, as it should be equal to the flux of regular and Dark Matter particles tunneling at a given moment. Additionally, based on this model for DE, it seems that no distinct Dark Energy particle types are to be found, but rather we have already encountered (tunneling) DE particles as components of the vacuum fluctuations.

Third, in

Section 2.2 it will be suggested that placing a LAN inside another LAN might allow for an intuitive picture for the particle’s spin (see

Figure 2). Following this idea, we will construct all possible second order systems (i.e. systems of LANs with embedded LANs in them) and we will survey their characteristics. In

Section 4.4 it will be shown that placing the internal LAN inside a

Z-based substrate results in three different types of systems, noted as

,

and

(utilizing the exact same mechanism used to define Dark Energy,

vide supra).

and

will be collectively suggested to be

Dark Matter (DM) and

Regular Matter (RM).

Due to the finite memory of átmita, these flavors of matter do not interact with each other, except through their common

Z-substrates, i.e., only gravitationally. Because of the symmetry break between

and the (fully symmetric)

and

types, it is shown that the percentage of

should be 20% of

Z-based matter. This leads to the percentage of DM to be

, in good agreement with observations (see

Table 1).

Fourth, in

Section 5 we will survey the properties of all possible second-order

structures. There are sixteen distinct

systems, each of which will be corresponded with a (first-generation) particle of the Standard Model. Based on the structure of each system, some fundamental properties of each particle type will be discussed, such as how spin, mass, stability, charge conjugate symmetry and EM charge arise in each case. The systems that correspond to the graviton, the photon, the electron and the

boson will be surveyed in more detail and their specific properties will be extracted, albeit qualitatively. In this context,

spin will be argued to arise from a periodic motion of the internal LAN(s) inside the substrate (similarly to

Figure 2) and

mass from the motion of the internal LAN parallel to the momentum of the particle (i.e., from a longitudinal component of spin).

Although in this publication the neutrinos are not studied in detail, it will be evident by their structure that they are Dirac, not Majorana particles [

32]. Also, the fractional charges and colors of quarks, as well as the charge of the W-bosons, will be argued that it might be related to internal tunneling, i.e., of a periodic transformation of one of the internal LANs of the particle to one of the two Dark Matter counterparts. Such a mechanism should be absent in other particles (e.g., the

boson), which might provide an explanation for the anomalous mass measurement of the W-bosons [

33,

34,

35,

36], as it would allow these charged bosons to interact with Dark Matter particles.

Finally, in the Supplementary Information recipes for how to get Electromagnetism, the Weak force and Gravity out of the single communication protocol of átmita will be discussed, by correlating each Force with a signal coming from a surface of one of the particle’s LANs. Based on these (qualitative) recipes, several of these Forces’ known properties will be derived and the hierarchy of their relative strengths will be discussed in terms of how far away these surfaces lie from the particle’s router.

From the above outline of Átmiton theory, it is evident that this study will be introducing a plethora of new concepts, which need to be properly defined and explained. This is done primarily in the Supplementary Information via figures and examples, but also in the later sections of the main document (

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6). In those sections, all these novel concepts will be anchored to known attributes and phenomena of

CDM and the Standard Model, which will hopefully aid with their comprehension.

As this is the first publication on Átmiton theory, several results will be shown in detail, but there will also be a lot of suggestions and notions that should be further surveyed with subsequent studies. These should be considered as hits for further avenues of development, rather than claims to extraordinary results set in stone.

2. Using the LAN Structure to Visualize Quantum Paradoxes

2.1. Visualizing a Particle/Field Entity

In computer networks, the local area network (LAN) refers to a communication network of nodes (typically computers, smartphones, etc) that are interconnected through a network topology (meaning the map of the nodes’ connections) and are able to exchange information. Information exchange between two nodes in the same LAN makes use of a single identification number for each node, called the private IP address (IP stands for “Internet Protocol”), assigned to them by a special node, called the router. The private IP address is locally unique, in the sense that no two nodes in the same LAN can have the same private IP, but nothing prohibits nodes belonging to different LANs to share a private IP.

If a node in a LAN wants to connect with a node outside the local network (e.g., with a computer in another LAN), it can do so through a router that is connected with the Internet, which is a network of networks. To communicate through the Internet, all nodes in the same LAN share the same, single identification number, called the public IP address, and send messages to the outside world with the router acting as the sole gateway. The public IP address of each LAN is thus globally unique and in an abstract way defines the position of the LAN’s router on the global network.

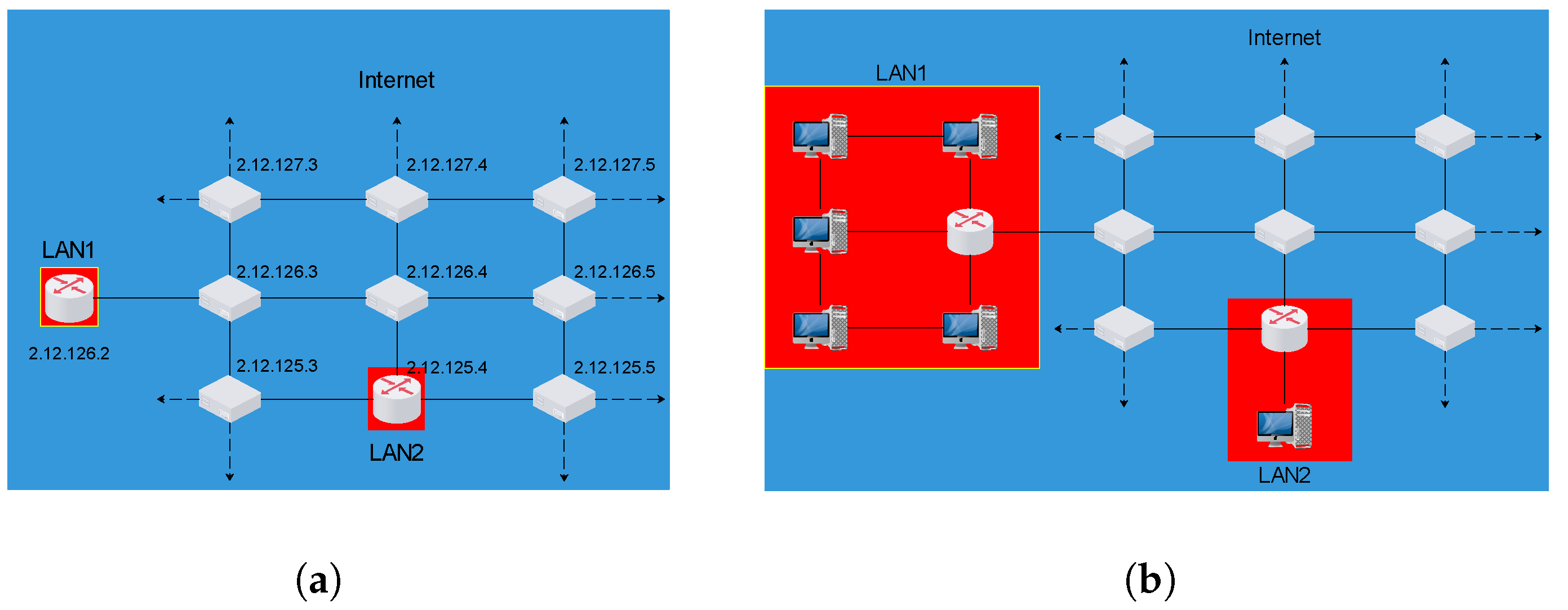

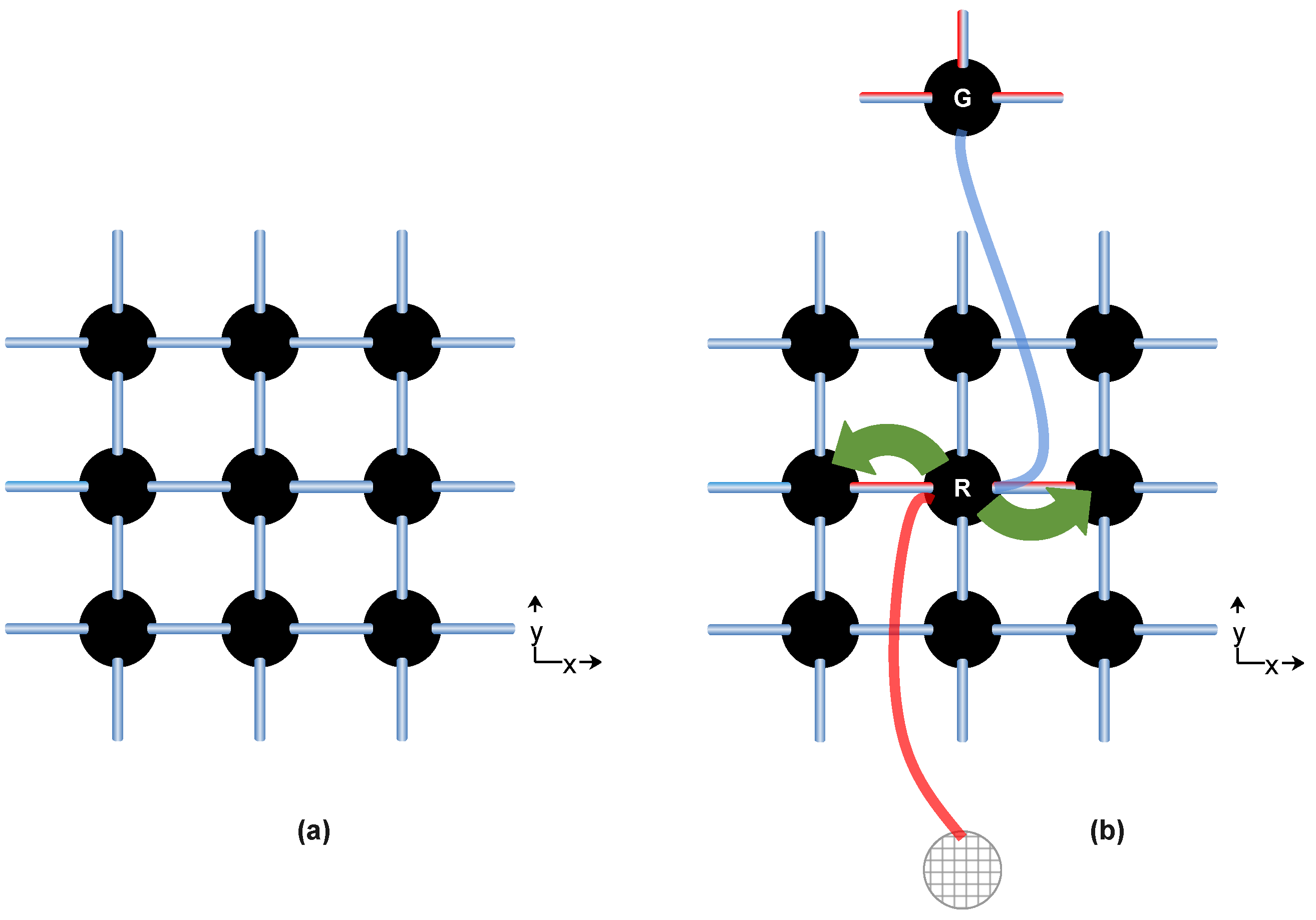

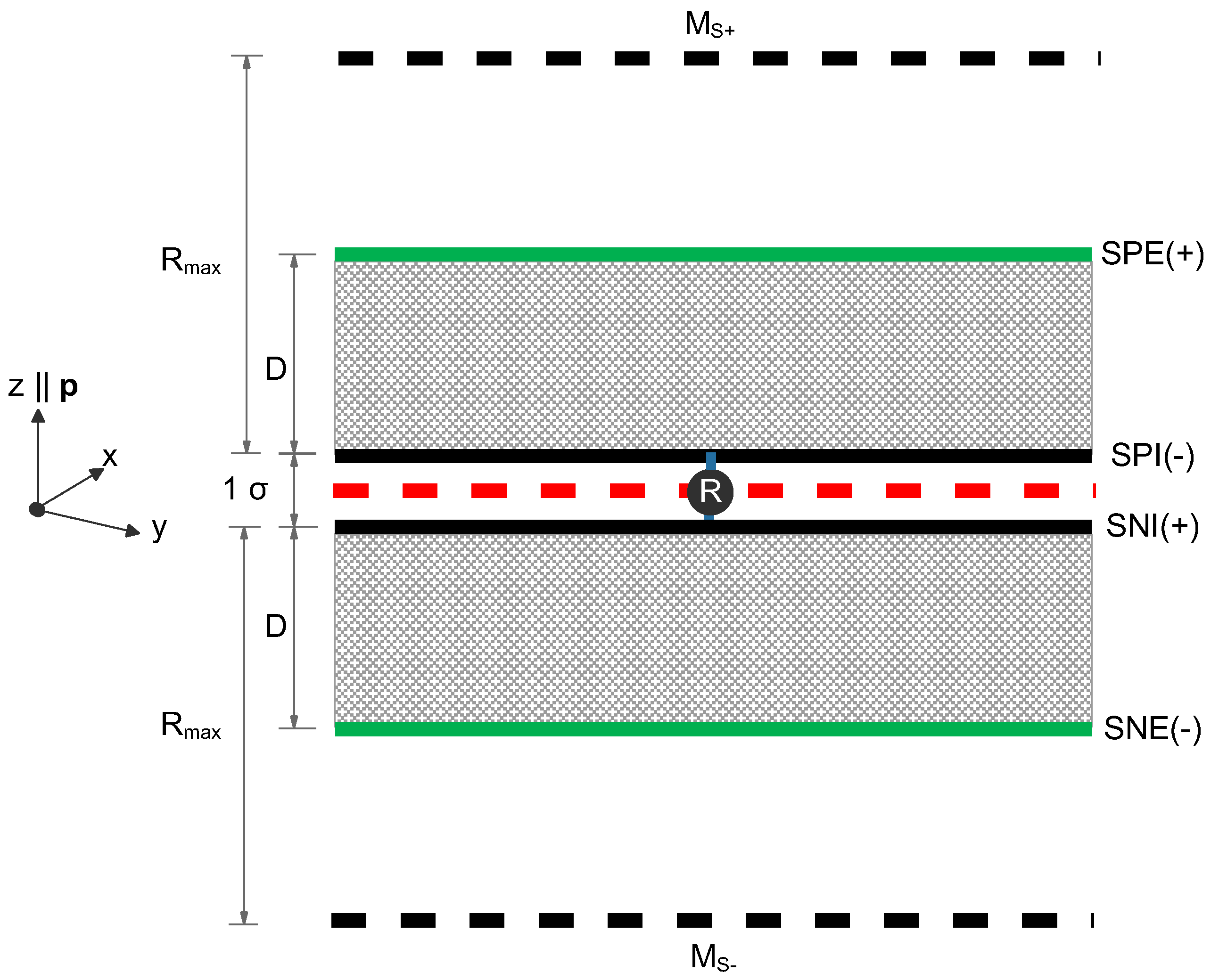

Based on the above, if one depicts the topology of the interconnections of all nodes on the Internet based on their (public) IP addresses, each LAN would look point-like, in the sense that all of its nodes have the same public IP address and the LAN has a single point of contact with the Internet (see Figure ??). On the other hand, the fact that the LAN has actually some internal structure makes a large difference in regard to the way it interacts with the rest of the world, as a LAN consisting of a single node would create, process and demand data in a completely different way than a LAN consisting of hundreds of telecommunication nodes interconnected with a certain network topology (compare LAN1 and LAN2 in Figure ??).

Furthermore, given that the private IP addresses of the nodes in each LAN are only locally unique, there could be nodes in other LANs with the same IP addresses. As a result, if we imagine an abstract “address-space” of IP addresses, in which each node of every LAN is placed according to its local address, then each LAN would cover a portion in this space (i.e., a field), with several LANs potentially overlapping each other, just like fundamental physical fields overlap at each position of space in quantum field theory.

The above considerations allow us to draw an interesting parallel to Particle Physics, by noting the Internet as analogous to space, the router connecting each LAN to the Internet as analogous to an elementary particle’s position and each particle’s field analogous to a LAN, sharing with other LAN/particles potentially overlapping portions of an abstract address-space hovering over space. In other words, it seems that a LAN can be thought as having both point-like and field characteristics, in analogy to an elementary particle in quantum (field) theory.

2.2. Visualizing the Spin of a Point-like Entity

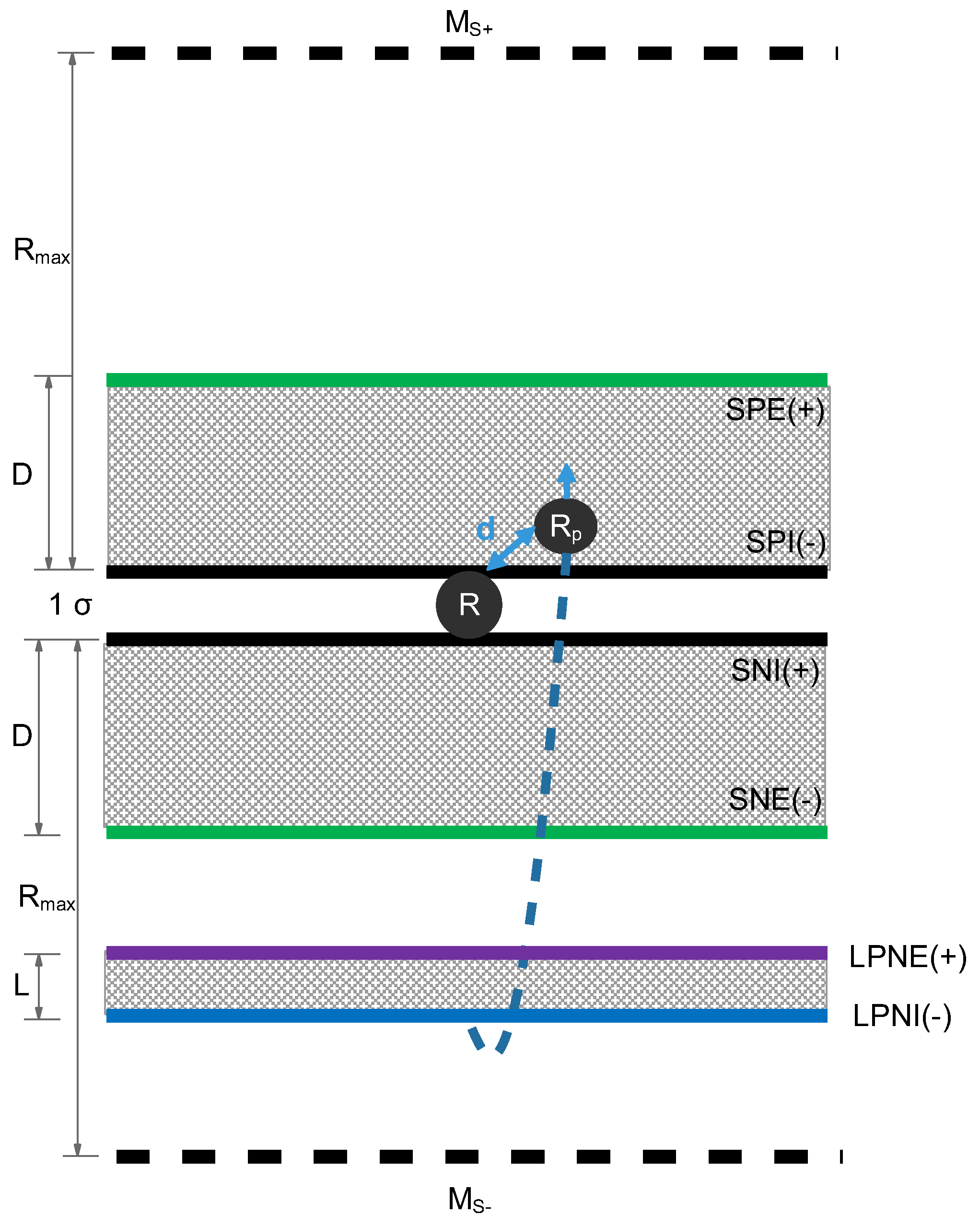

Let us now embed a new LAN

inside the initial LAN. The initial LAN (acting as a substrate for the new LAN) would then be

external, in the sense that has a direct connection with the Internet, whereas the new LAN would be

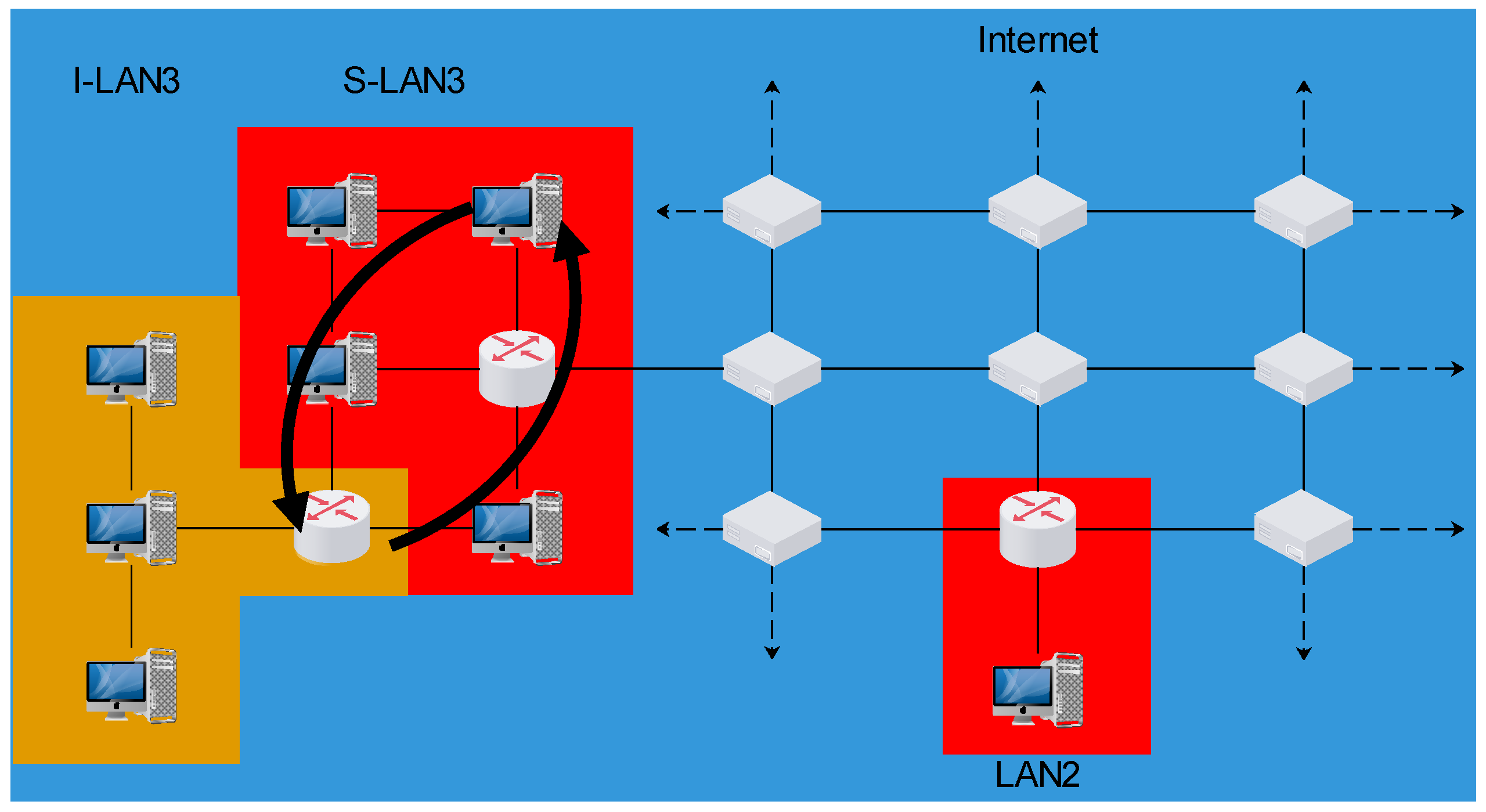

internal, as it has no direct connections with the Internet (

Figure 2). The internal LAN would seem point-like to an observer being at some node of the external LAN, while an observer outside both LANs (i.e., on the Internet) would deem the

whole structure as being point-like.

Indeed, LAN3 in

Figure 2 consists of an internal and an external LAN (termed I-LAN3 and S-LAN3, accordingly), but for an outside observer the collective LAN3 would still look point-like and identical to LAN1 of

Figure 1(a). Nonetheless, LAN1 and LAN3 have different internal structures, which could cause them to exhibit very different characteristics.

For instance, if we now allow I-LAN3 to be hopping around S-LAN3 by gradually shifting its router’s connection from one node of the substrate to the next in a circular manner with a characteristic period (see

Figure 2), then this motion can be considered (after appropriate definitions) to be carrying

spin (i.e., intrinsic angular momentum). Note that the rotation of I-LAN3 is (the analogous of) a motion on a

field (i.e., the substrate S-LAN3) and not in space (i.e., the Internet).

For an observer on the Internet, this spin would have no physical meaning, as they would perceive the whole structure of the two nested LANs as a single point, incapable of having internal motions/rotations, but at the same time, this spin would manifest itself through the interactions of the nested system with other LANs, as the time it takes for a signal coming from outside LAN3 to arrive to a specific node of I-LAN3 would depend on the distance between the routers of the internal and the substrate LANs, which would be fluctuating due to this periodic motion.

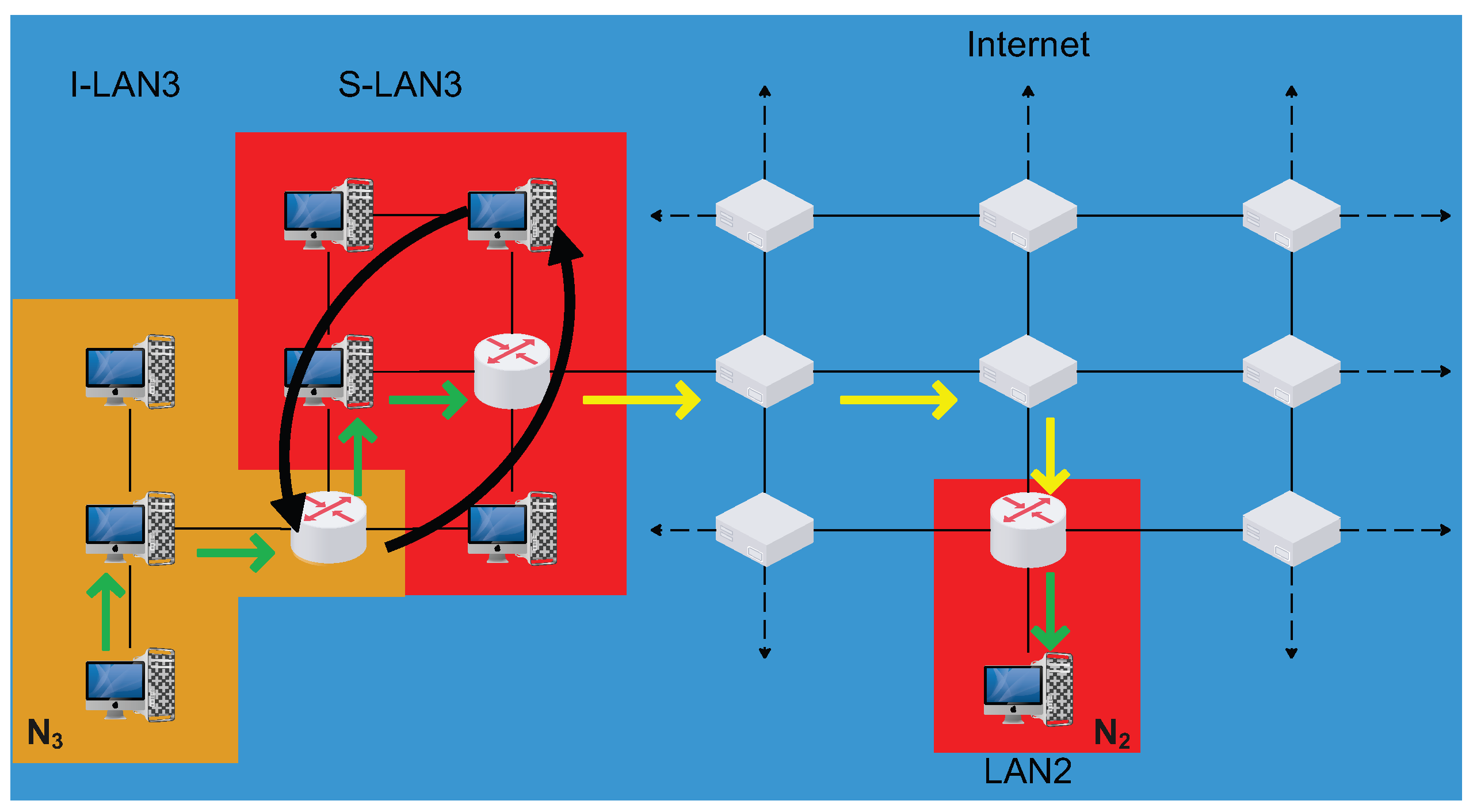

As an example, in the situation depicted in

Figure 3 the signal going from node

of I-LAN3 to node

of LAN2 would have to cross the static number of nodes on the Internet separating the routers of LAN3 and LAN2, plus a fluctuating number of internal nodes, namely:

, where

is the total number of intermediate nodes that this signal has to cross in its route from

to

,

is the number of nodes on the Internet separating the routers of LAN3 and LAN2,

is the number of internal nodes separating the router of I-LAN3 and S-LAN3 and similarly for

.

An outside observer would still consider both LAN3 and LAN2 to be point-like (like

Figure 1(a)), thus they would consider

only as the distance of the two point-like particles, whereas they would be oblivious to the fluctuating

and

internal distances.

In the hypothetical scenario that there is a law connecting the strength of the interaction of I-LAN3 and LAN2 with the total distance separating nodes and , then this law would have two separate terms: One term that would only depend on the distance of the two LANs’ router on the Internet and another term that would depend on the phase difference of the two systems’ internal rotations.

This, of course, is qualitatively in line with the usual QM situation of breaking the wavefunctions into independent spatial and spin terms, the former depending only on the distance between the two particles in space and the latter on the two particles’ phase difference at a given point in time.

2.3. Roadmap for the Development of Átmiton Theory

The aforementioned analogy between LANs and quantum particles is arguably useful by itself, as it can enhance our intuition on these quantum paradoxes. But it also allows for the enticing possibility that the LAN/particle analogy might actually stem from a deeper connection between these two structures. We will thus argue for the need of surveying the possibility of a new formalism for quantum and particle physics, having the notion of the LAN at its heart.

This formalism, which we will term as “Átmiton theory”, would have all elementary particles being (systems of) LANs, each type of particle (e.g., , , etc) exhibiting its unique characteristics by having a discrete network topology. These LANs/particles would then interact with each other by exchanging signals that propagate through space (which would thus play a role analogous to the Internet). On the one hand, this analogy provides a mental picture of how an expansive entity – like a field or a wave – can appear point-like from outside. On the other hand, accepting the aforementioned premise immediately leads to several important notions:

1) The position of an elementary particle would correspond to where the LAN’s router is connected with the Internet/space.

2) Space would be discrete in this setting and space would be made of the same type of nodes as any particle. We will be calling these nodes

átmita. Note that if all particles are made of the same underlying “essence” as space, this could further demystify the known phenomenon of the Cosmic Background Radiation losing energy as the Universe expanses [

20,

37], given that the átmita that form the expanding space would have to come from an equal amount lost by particles.

3) Another important consideration for this model is the definition of time. If we allow all nodes to be switching positions with one of their nearest neighbors in every LAN once per unit time (like the router of I-LAN3 in

Figure 2), then this hop rate would define the highest possible speed (i.e., the

speed of light) and each such “turn” the quantum of time, but it would impose no upper speed boundary for information propagation. This instantaneous information exchange could allow for two LANs to share a virtual connection over large distances, possibly providing a mechanism for two far-away particles to form an Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) connection [

38,

39].

4) Since all nodes inside the LAN are not directly connected with the Internet/space, they would have to send their signals to the outside world through the router, which would translate them in a form that can propagate in space (i.e., through a process similar to translating the private IPs to a public IP address, organize how the signal will be transported on the web, etc). Systematic differences on how these signals are structured (due to different network topologies of different kinds of particles) might potentially explain how the different characteristics of the Physical Forces (Gravity, EM, etc) could arise from a single communication protocol.

5) Effectively, each LAN would correspond to a field, with each particle potentially consisting of a number of fields, either embedded in each other, or possibly placed on a common substrate LAN. Particles having distinctly different systems of LANs, would thus exhibit distinct attributes in terms of these fields (i.e., maybe the graviton would consist only of the “gravitational” LAN, whereas the photon would also have LANs relevant to EM and the Weak Forces).

6) In Particle Physics, the Fields that give rise to Gravity, EM and the Nuclear Forces are considered completely separate from each other (unless they are explicitly coupled via some interaction [

40]). This leads to the many independent parameters of the Standard Model, which can be fine-tuned in isolation. But the idea presented in

Section 2.2 that placing a field inside another field could generate the particle’s spin, might reveal a deeper connection of these fields (if, say, the substrate LAN was the Gravitational Field, the internal LAN the EM Field, etc). If such deeper connections indeed exist, then such a formalism might be able to reduce the number of free parameters of the (equivalent of the) Standard Model.

We conclude that a major advantage of such a formalism is that it would require only one species of “nodes” and one communication protocol, from which one would, in principle, derive the fundamental properties of elementary particles (e.g., charges, masses, symmetries, etc) and their interactions (all based on their network topology).

To realize these notions and survey some of their consequences we need, therefore, to formulate a model that can fully replace the particle/field entity with systems of LANs. Here, we will start this discussion by outlining the roadmap of the creation of such a model and the main questions that need to be answered during its development, which will then start addressing in

Section 3 and in the Supplementary Information.

First, one would need to define the basic attributes of the fundamental entity of this framework, namely the node-like entity that we will be calling “átmiton”. At the very least, the átmiton should be able to form connections with other átmita (in order to construct LANs) and exchange information via signals.

Already we can identify several issues that need to be addressed. Regarding the way átmita are interconnected, one needs to answer questions such as:

How many nearest neighbors can an átmiton have?

What is the dimensionality of their network (e.g., is the network 2D, 3D, etc)?

What is the “crystal structure” – the local topology – of the network (i.e., is the network’s symmetry in line with a simple-cubic lattice, or some more complicated structure)?

How do átmita move on the network? Is their move instantaneous, or does it happen in steps?

How big is an átmiton? Is its size on the order of the Plank length?

Also, regarding the way átmita exchange information, one needs to define their “Communication Protocol”, which would at least provide answers to questions such as:

What kind of information does each signal contain?

How can the receiver identify the sender of the signal? In other words, is there some sort of unique identifier, or “address”, for each átmiton?

If átmita have a well-defined address, then is this address globally unique (like the public IP address of communication nodes), or is it a locally defined property? If the latter, then how are addresses translated from one “frame” to the other?

How does each signal propagate on the network? E.g., is it broadcasted? How does it move from one node to the next?

What effect would a given signal have when it reaches a certain (receiving) átmiton?

With a set of axioms and protocol processes that cover (at least) the above considerations, we will then start forming LANs of átmita and place them either in space, or on substrate LANs. To do this, as mentioned in

Section 1, we need to understand: (1)

How is the LAN connected to space (or to its substrate LAN)? Is there a “router” átmiton connecting the LAN with space? If yes, what is its functionality? and (2)

What addresses will the átmita of a particle/LAN occupy (i.e., is there a process similar of the one translating a private IP address – which is only locally unique – into a – globally unique – public IP address)?

Clearly, the approach outlined above moves from the bottom up, i.e., from individual átmita →LANs→particles with unique topologies→ derivation of their symmetries and characteristics. In principle, therefore, the collection of axioms and protocols that cover the aforementioned basic characteristics of the átmiton and its interactions should be the only ad hoc ingredients of the theory, everything else (e.g., particle symmetries, charges, characteristics of all physical Forces, etc) should get derived from these fundamental statements. Note that even though these statements will naturally be carrying some degree of arbitrariness (as is true for the foundations of every theory), this will be of a discrete nature, since – for example – the number of an átmiton’s nearest neighbors cannot be fine-tuned in the same way as the coupling constants of the Standard Model; that number should at least be a (relatively small) positive integer, directly connected to the local topology of the network.

3. Basic Principles of Átmiton Theory

In the spirit of the ideas mentioned in the previous sections, we demand an entity with no internal structure, called

átmiton, that can form a network with other átmita by exchanging information that establish connections. Átmiton is the only ingredient of this theory, in the sense that everything else (i.e., empty space, particles/fields, etc) will be considered to be systems of interacting átmita, with their network topology being what gives rise to the different characteristics of these systems (see

Section 4-

Section 5).

In its essence, an átmiton resembles a telecommunication node, or a simple computer on a network. It interacts with the other átmita on the network by sending signals that propagate through the network in an instantaneous but causal manner, in the sense that the signals will have to pass through each intermediate átmiton to arrive to their destination, similarly to how in chess a bishop can move through multiple cells in a single move (instantaneous), but only if each one of the intermediate cells on his path is unoccupied (causal).

Here in the main manuscript we will give a relatively brief outline of the basic properties of átmita, but for a more thorough discussion see the Supplementary Information (Section ??). A summary of this discussion is condensed in Supplementary Section ??.

3.1. Átmiton’s Connections and Address

Fundamentally, each átmiton should be able to form connections with other átmita in order to create a LAN; similarly to how the nodes of

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 are connected. The number of possible direct connections an átmiton can have (i.e., the number of its so-called

ports, each port capable of connecting with a neighbor) is therefore the most basic attribute of these entities. It is defined axiomatically to be six:

Two neighbors at each dimension of a 3D network. In other words, the “crystal structure” of the network is that of the simple cubic crystal (see Axiom 1 in the Supplementary Information).

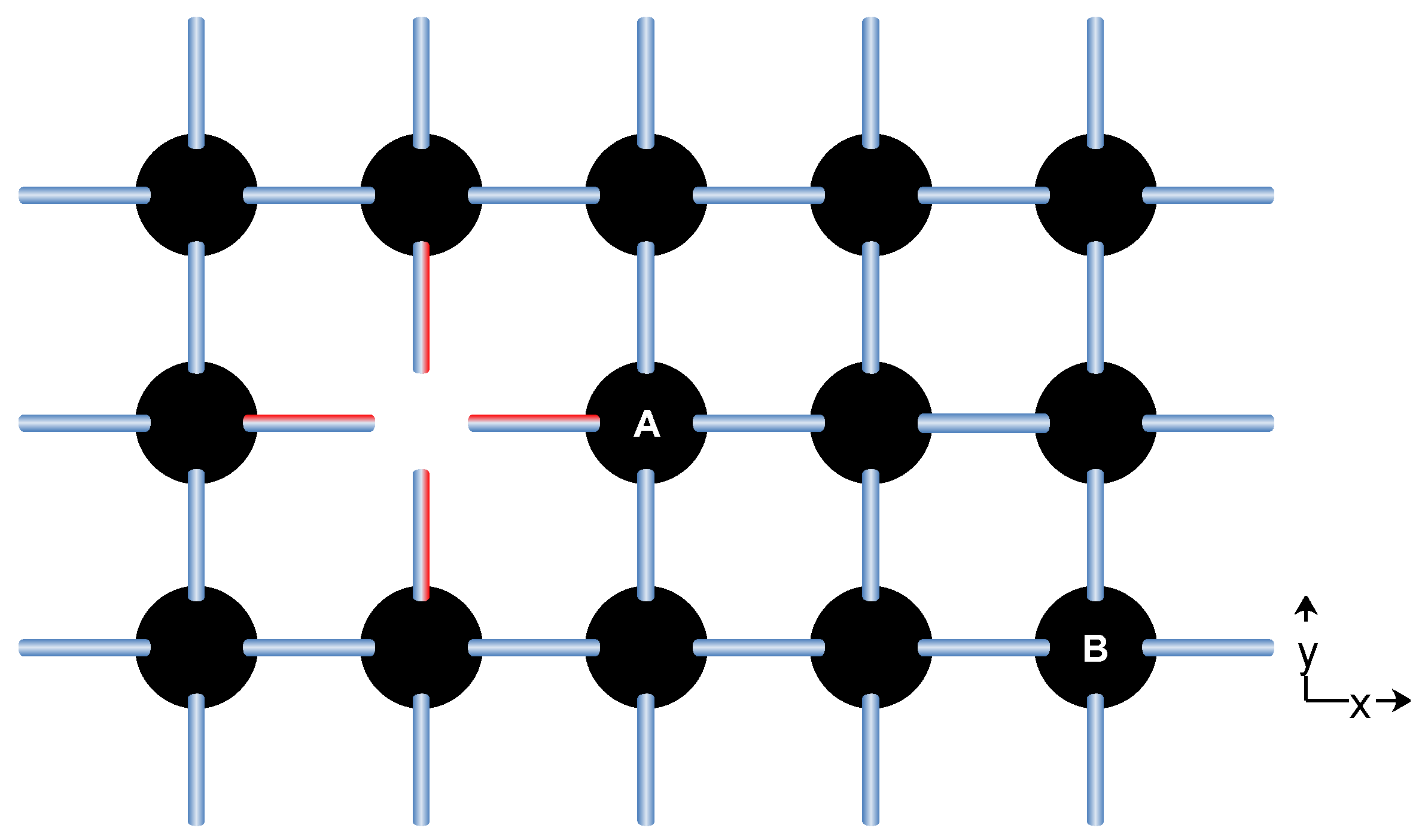

Of course, átmita should be able to interact with non-nearest neighbors, which is accomplished by passing the relevant signals from one direct connection to the next, similarly to how computers exchange information online. A very useful metric of that interaction is, therefore, the connection distance, , of those two átmita (denoted as A and B): It is defined to be the number of direct connections in the shortest continuous path that enables them to interact. Evidently, the connection distance of two nearest neighbors defines the quantum of distance in this theory, which we will be calling stathmós (plural: stathmoi) and we will be denoting as in natural units or (i.e., quantum of length) in the International System of Units (SI).

From the above, it becomes immediately apparent that

Space in this context is fundamentally static, flat and discrete (being a simple-cubic crystal). This seems to be at odds with

both the curved spacetime continuum of general relativity

and with the active vacuum soup of quantum field theory (QFT) [

41,

42]. Nonetheless, in

Section 4.1 it will be demonstrated that particles introduce an

effective curvature at the point they are connected to the lattice of Space (i.e., at their router), which makes a given distance in their presence seemingly longer. Also, in

Section 4.3, we introduce the idea that vacuum energy comprises of Dark Energy particles tunneling by temporarily turning to their regular-matter counterparts and in Supplementary Section ?? we will show that DE creates an apparent expansion of a given distance (as seen by a regular-matter observer), in line with current astronomical observations. As a result of these effects,

both the spacetime curvature of GR and the vacuum fluctuations of QFT can be thought of being superimposed on the above static background of Space átmita.

Turning now to the interaction of individual átmita, it is important to understand what sort of signals do the átmita exchange and to what effect. These questions are addressed by Axiom 2 and Protocol Process 1 in the Supplementary Information: As stated in Axiom 1, each átmiton has six ports, one for each possible nearest neighbor. According to Axiom 2, if a given átmiton,

A, has fewer than six nearest neighbors (and thus has an open port), it will broadcast a signal to the network, containing the address of the hole (see átmiton

A of

Figure 4).

The effect of that signal is defined by Protocol 1: If another átmiton, B, receives the signal and has a relevant open port (e.g., A signals a [] hole and B haves a [] open port), then they will interact and potentially start moving on the lattice towards each other, until they annihilate their holes (see Supplementary Figure ??). Else, átmiton B will pass the signal sent by A along to the rest of its nearest neighbors. This is, in principle, the root of all interactions in this theory, whereby communicating átmita can converge and form a compound network (i.e., a unified LAN).

It is evident that the above signal exchange requires for each part of the interaction to have a unique identifier; like the “From/To” information needed to send an email. Thus, we demand (Axiom 3) that each átmiton should have a unique address that permits it to exchange information (in the form of signals) with other átmita.

An important point discussed in the Supplementary Information is that these addresses are unique when compared

in the same frame of reference. Each átmiton has its local frame of reference, to which it translates all other addresses. In simple scenarios (such as the ones depicted in Supplementary Figure and

Figure 4) this translation is trivial (i.e., neighboring átmita have “neighboring” addresses in all frames), but in more complicated instances this process can result in addresses of nearby átmita that are widely different from their position on the lattice (see

Section 3.4).

Based on the above, the notion of an átmiton’s address leads to a second measure of distance between two átmita, namely that of the

address distance,

of two átmita with addresses expressed as the vectors

p and

q. When the address translation between the frames of the two átmita is trivial (e.g.,

Figure 4), then these two measures of distance (

and

) are equivalent. Nonetheless, in most cases of practical significance this is very much

not the case, as will be discussed in

Section 3.4. Indeed, in the context of this theory, the non-interactive nature of Dark Energy and Dark Matter (excluding gravity for the latter) stems from

(see

Section 4 and Supplementary Sections ??-??).

Therefore, it seems natural to bundle into a single entity all átmita that translate their addresses trivially from one local frame to all others’. This will be called a

LAN, which is a collection of átmita that share an

effective frame of reference, meaning that for each pair of átmita

A and

B in the LAN, the translation of their addresses to each other’s frame is trivial. The átmiton of a substrate (or Space) on which a LAN is connected will then be called

router átmiton. The router can be thought of being a part of both the LAN and its substrate, as it has the role of translating the addresses from one effective frame of reference to the other (similarly to how the router translates the private IP addresses to public IP). Detailing this process will be the main focus of

Section 3.4. The collection of LANs which are connected to Space through the same, single, router átmiton will be what we will call a

particle. For example, the combination of the internal end external LANs (denoted collectively as LAN3) in

Figure 2, would be considered a particle.

As an example of the above discussion,

Figure 4 depicts a simple case with an átmiton,

A, that has an open port and to close it, it generates and broadcasts a signal. Note how the signal is translated from the local coordinate frame of átmiton

A: [

](

), to that of átmiton

B: [

](

).

Based on Protocol 1, such a signal exchange would ultimately lead to átmita moving on the lattice (see, e.g., Supplementary Figure ??). Axiom 4 and Protocol 2a define how this motion takes place on the lattice (Supplementary Section ??), by providing an answer to questions such as: How do interacting átmita move to converge? Is the move instantaneous (like the way their signals propagate on the lattice), or it happens gradually? With Axiom 4, we demand that the internal topology and the position of each LAN (relative to other LANs) evolves in turns, each of which is called a gyros (plural:gyroi) and is denoted as in natural units or in SI. Obviously, one gyros is the quantum of time in this context.

In turn, the specific way átmita move on the lattice is defined by Protocol Process 2a: During each gyros, each átmiton can hop to fill a vacant port of a nearby átmiton, by changing its address (in any given frame) by one unit (see Supplementary Figure ??). The allowed (by Protocol 2a) hop of one unit per gyros of an átmiton moving in its LAN, defines the maximum allowed speed in this theory and will be denoted as the speed of light.

A critical detail in Protocol 2a is that only movements to

vacant ports on the lattice are allowed. This is a direct consequence of Axiom 3, as a movement to a filled position would result in two átmita sharing an address. Thus, in the situation depicted in

Figure 4, átmiton

A can hop to the vacant position at its left during the next gyros, but cannot go towards any other direction, as all of its other nearest neighbors’ ports are filled. In addition, due to the same reason, átmiton

B of

Figure 4 would not be able to move towards the vacant position at the left of

A, even if

B had a relevant open port.

As a final point, note that if the interaction between two átmita is intra-LAN, then each átmiton can move independently from the rest of its LAN towards the hole, as is the case for átmiton

B in Supplementary Figure ??. But if the interaction is extra-LAN, then the whole LAN should move in address-space towards that hole. Therefore, this motion of the LAN in address-space requires an actual motion of the particle’s router in Space (or on its substrate more generally). This distinction will be utilized in

Section 5 and in Supplementary Sections ??-??, in order to understand which interactions generate the internal characteristics of a particle (e.g., its spin, stability and mass) and which interactions generate the physical Forces felt by the particle through Space.

3.2. Memory of the átmiton

If the interaction of an átmiton is with some distant átmiton, how does it know what path to follow on the lattice to reach that open port? Also, can an átmiton interact with a signal coming from an arbitrarily large distance? Axiom 5 addresses these issues (Supplementary Section ??), by stating that each átmiton has a finite internal memory of size M, where M is a very large natural number. In this memory, the átmiton stores the information needed to reach (generally after several gyroi) the open port with which it interacts.

In

Section 3.3, it will be argued that the finite memory of átmita might be at the root of the wave-like properties of particles. Indeed, in

Section 3.3 the De Broglie formula will be recovered, by demanding that

M is actually Plank’s constant

h, translated to the natural units of this theory. Also, in

Section 4.2-

Section 4.4 we will utilize Axiom 5, in order to understand the lack of interactions between particles or regular matter and their counterparts of Dark Energy and Dark Matter.

The general way that information is stored in the átmiton’s memory is defined by Protocol Process 3a (see Supplementary Section ??): Let an átmiton A interacting (in the sense of Protocol 1) with an átmiton B, which lies at a connection distance and an address distance . Then, the memory volume that átmiton A reserves (in order to define the map of how to reach the open-port of átmiton B), consists of blocks of memory units, each block defining one gyros of the process and the total number of blocks being proportional to . The memory volume of each such fundamental block is a monotonically increasing function of .

We can note the above form for the memory map as , where (i.e., the memory block’s volume) is a monotonically increasing function of (see Supplementary Figure c,d).

Note that the above form of Protocol 3a is somewhat vague in terms of how the memory requirements of an interaction are organized in the átmiton’s memory. To be able to use the axioms and protocol processes governing the behavior of individual átmita in order to simulate/calculate quantitative properties of each elementary particle would require an updated version of Protocol 3a, with an explicit form for

. Nonetheless, the above general model for

is enough for deriving a number of important results, such as calculating

ab initio the percentages of Dark Energy and Dark Matter, showing the cause of their (lack of) interactions with particles of regular matter (

Section 4.2-

Section 4.4) and demonstrate several important qualitative characteristics of the known Standard Model particles, such as their EM charges, spin and stability (

Section 5).

For instance, a crucial result that stems directly from Protocol 3a is that two átmita that have an address distance , such that , would not interact regardless of how small their connection distance is (i.e., regardless of how close they are in Space), as the information defining the interaction would not fit in the átmiton’s memory ( would be out-of-bounds).

In

Section 4.2 it will be suggested that this is why particles of regular matter do not interact with their Dark Energy counterparts, even if they are extremely close to each other in Space: Although their

distance can be arbitrarily small, their address-distance

is such that

is always larger than

M (this is explicitly shown in Supplementary Section ??).

From the above discussion is clear that for a given interaction between two átmita, there is a maximum connection distance

for which

. If the second átmiton is farther away than

, the first átmiton won’t interact with it. The value of

depends on the configuration of the two interacting átmita’s LANs. For instance, it can be vastly different if the two interacting átmita belong to the same LAN, or not, see

Section 3.4. Indeed, given that a LAN has a single effective coordinate frame, which trivially translates its átmita’s addresses from one to the other (i.e.,

), intra-LAN interactions should be the case with the maximum possible value of

from any conceivable configuration (see cases studied in Supplementary Section ??). This ultimate

will be denoted as

.

Protocol 3a (discussed above) outlines the way an átmiton stores in its memory the information of one signal. But what if that átmiton has more than one open port and thus receives several corresponding signals? How will these signals be stored in its memory and how will they affect its future path on the lattice?

We require with Protocol Process 3b (see Supplementary Section ??), that the átmiton in question fills its memory gradually, by adding each memory map as they arrive to it, step by step: It will first put the information of the nearest signal () to its memory and (if there is still space in its memory), that of the second closest signal (), etc, until either all signals are registered in its memory, or its memory runs out of space.

Protocol 3b allows us to study extra-LAN interactions (i.e., interactions between átmita belonging to different LANs). These would result in the router átmiton R of the LAN to move in Space, in order for the interacting átmita to converge (see, e.g., Supplementary Section ??). But a LAN generally contains multiple átmita with open ports, at least on all of its surfaces. Hence, these can generally participate at the same time in several individual interactions, each with its own memory map. All the memory mappings of every átmiton of the LAN interacting with other LANs should be weighed by the router átmiton, which should translate these interactions to an actual motion of the particle in Space, by a series of hops (Protocol 2a). According to Protocol 3b, the nearest átmiton to the router R that participates in an interaction will send its memory map of volume and this map will be stored in the router’s memory (provided of course that ). If there is remaining space in its memory, the router will add , , etc, until it fills its memory completely.

From the above, it is evident that

the closer an átmiton of the LAN is to the router, the better chance it has to affect the particle’s motion by having its interaction engraved in the router’s memory. Thus, if one can attribute specific átmita with open ports (e.g., one specific surface of the LAN) to a specific force (e.g., Gravity), then as a rule of thumb

the farther the átmiton generating the interaction lies from the router of the particle, the weaker the interaction. In

Section 5 and Supplementary Sections ??-??, we will argue that specific surfaces of each particle of the Standard Model act as the “charges” of EM, Gravity and the Weak Force and we will derive their strength hierarchy (albeit only qualitatively) based on these surfaces’ proximity to the particle’s router.

3.3. The Wave-like Properties of LANs

Let us now move from the level of the individual átmita to that of their LAN. At this higher level the router átmiton is of the greatest importance, as its memory matrix defines the actual path of the particle in Space, i.e., it translates all the individual átmita’s interactions to a motion in Space.

Based on Protocols 3a,b, the memory of a particle’s router will be organized in memory blocks of average size each defining the motion of the particle/LAN in Space for one gyros. is what we will call energy, E.

The minimum allowed energy of a LAN (denoted as in natural units and in SI) would then be due to a single átmiton interacting with an open port of one of its next-nearest neighbors. Based on Protocol 3a, .

According to Axiom 5, the átmiton stores in its memory the information of how to reach its destination after several gyroi. We will denote the number of gyroi that fit in the memory of the LAN’s router átmiton as the LAN’s period. By definition, the period T is equal to: , where the brackets indicate the integer quotient of the division.

From the definition of the LAN’s energy and period and their relationship to the router’s memory, we conclude that:

where

E is the energy and

T is the period of the LAN. Note that

, if

.

As a result of Eq.

1, the larger the energy of the particle, the smaller its period, or equivalently, the larger its frequency. This is De Broglie’s formula [

43]

, with the substitution:

. To extract

M in natural units (as a unitless natural number), we have to turn

h in units of

, or equivalently

M in units of

:

where

and

are the quanta of energy and time in the natural units of Átmiton theory,

and

are the corresponding quanta in SI units and

the Plank energy. Here it is assumed that the quantum of time in SI units,

, is equal to Plank time (

).

The final result, therefore, is that M as a unitless natural number is the Plank energy (reduced by ) written in units of energy quanta. This makes sense: The largest energy a particle can have (Plank’s energy) corresponds to the shortest possible period (Plank’s time). In Átmiton theory, when the energy is the maximum permitted, then and that leads to the shortest permitted period of one gyros, as there is enough memory-space to define the trajectory of the particle only for the next gyros.

Based on the above discussion, we can outline the model for how an átmiton interacting with an open port of an átmiton of another LAN can move towards it and fill the said hole: Its LAN’s router will hop on its substrate from neighbor to neighbor, provided they have open ports (Protocol 2a) with the path taken predetermined from the beginning, for as many gyroi as they fit in the router’s memory (Protocol 3a), i.e., for one period. Thus, it seems that either the LAN interacts with its environment only once per period, when the memory of the router is vacant (Supplementary Figure c), or alternatively that every time a memory block is executed, it gets removed from the router’s memory to make way for another interaction’s memory block to take its place at the end of the memory’s queue (first-in-first-out, like Supplementary Figure d).

The wave characteristics of particles might be understood in light of these possibilities. For instance, consider the double-slit experiment: The fringes appear when the wavelength of the light is on the same order of magnitude as the distance between the slits. According to this view, this is because a photon with a much shorter wavelength wouldn’t interact with the second slit (it would be out-of-bounds of its memory), whereas a photon with a much greater wavelength (and hence a large period) would have its path predetermined for a time-period much larger than the time it takes to transverse the distance of the slits, so the interaction with the other slit would be statistically insignificant, i.e, its phase will be changing too slowly to form an interference pattern. Thus, although individual photons pass through just one slit, there is an interference pattern because each one can “sense” the second slit through its (absence of) signals.

This memory-model could also be relevant to understanding how the virtual particles (of QFT) are able to get absorbed with 100% probability: They get emitted by the particle only if there is a pre-calculated path leading them to the absorbing particle with the duration of the path being less than a period. Else, they are not emitted. But due to its router’s finite memory, the higher the energy

carried by the virtual particle, the shorter its period

in which it can pre-calculate its path leading from the emitting to the absorbing particle. Using Eq.

1, this means that

(in natural units), or

(in SI units).

In summary, in this section the fundamental properties of individual átmita were outlined (for a more rigorous treatment, see Supplementary Section ??). Based on these fundamental statements, in

Section 3.4-

Section 4.4 we will study the properties of

LANs of átmita, but still without detailing their internal structure.

Indeed, treating each LAN as a black-box of unknown shape and internal structure is enough to derive several important results, such as recovering the Schwarzschild metric around a spherical mass, finding recipes for Dark Energy, Dark Matter, quantum tunneling and vacuum energy, as well as for calculating the universe’s percentages of Dark Energy and Dark Matter. The internal (i.e., field) structure of the particles of regular matter will be the focus of

Section 5, in which we identify each particle of the Standard Model to be a second-order system of átmita that obeys a certain symmetry.

3.4. Placement of a LAN in Space

Having defined some of the most fundamental characteristics of individual átmita, their LANs and their interactions, we now turn to the very important question of

how to place such an entity on the lattice of Space. Since Space is a vast 3D network of átmita with the simple cubic topology without holes and only integer addresses are valid (see

Section 3.1 and Supplementary Section ??), the LAN’s router can be placed at

neither an interstitial

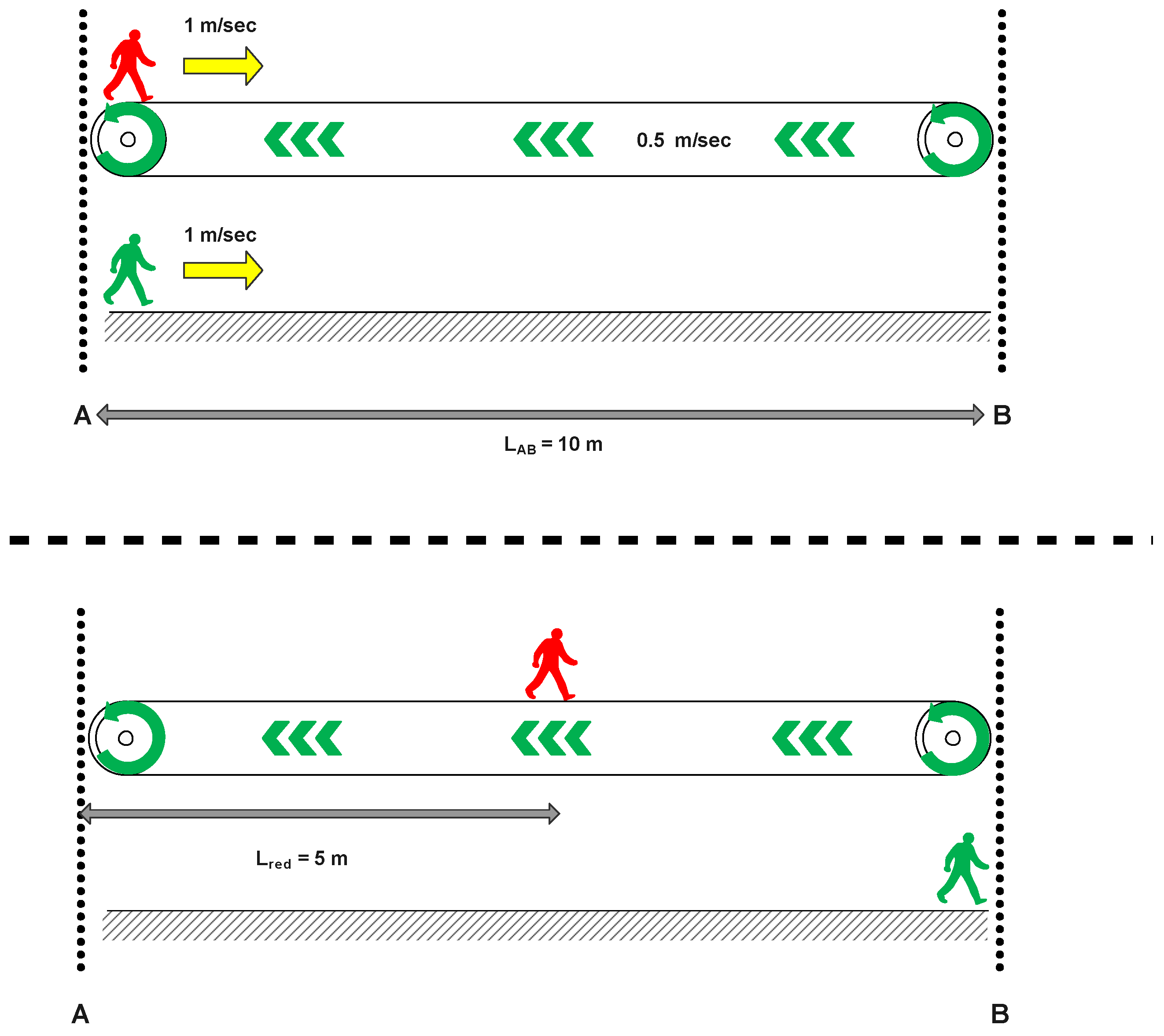

nor a substitutional position. Thus, placing a LAN in Space would require to either: (A) increase the dimensionality of Space by 1 (from 3D to 4D, hence increase according to Axiom 1 the number of possible direct connections for each átmiton by two), or (B) to (locally) re-define one of the three dimensions of the router átmiton’s coordinate system to point towards its connection with the LAN and not towards its nearest neighbors at one dimension of Space (see

Figure 5).

To keep Space 3D, we will demand with Protocol 4 (see

Section 3.5) that the router átmiton (denoted as

R in

Figure 5b) re-defines one of the

x-

y- or

z-dimensions of its

local coordinate system to coincide with the connection established with the LAN. Effectively, this coordinate-recalibration creates a

field, i.e., a (kind of) space overlapping our regular Space.

Which dimension does the router choose to repurpose, in order to connect with the LAN? According to Protocol 2a, the LAN connected to router

R can only hop to a neighboring átmiton of Space,

if it has an open port. For example, for átmiton

G of

Figure 5b to move in address-space, its router

R has to hop by swapping positions with one of its neighbors in the [

] or [

] directions, as all other nearest neighbors of

R do not have open ports. Thus,

the repurposed dimension defined by Protocol 4 is not fixed, rather is always parallel to the instantaneous motion of the particle in Space, as the introduction of the broken connections is what allows the motion of the router in Space in the first place.

This field-creation process is possibly the most critical aspect of the axiomatic formulation of this theory, as it governs everything, from the differences between DE, DM and regular matter particles, to several key characteristics of each particle type (

Section 4-

Section 5). In a sense, the rest of this publication from here on is just a discussion on the consequences of this process.

In more detail, therefore, a full comprehension of the situation depicted in

Figure 5 requires a three-pronged approach:

(A) We need to define what address átmiton

G of

Figure 5b will occupy, without address-collisions with átmita of Space. This will be accomplished with Protocol 4, which is detailed in Supplementary Section ?? (and its consequences will be surveyed in

Section 3.5).

(B) Since one dimension of

R’s coordinate system is repurposed for connecting with the LAN, the two former connections of

R with the neighboring Space átmita across some dimension will have to break (see the red connections of

Figure 5b), as Axiom 1 prohibits

R to have more than six direct connections. This changes the local geometry of Space and its consequences are discussed in

Section 4.1.

(C) The router átmiton,

R, has an open port at the opposite direction from the one it chose to connect with the LAN (i.e., direction [

] of its local frame in the example depicted in

Figure 5). This direction is fixed (see Protocol 4, Sect.

Section 3.5) and it does not affect the motion of the particle during the next gyroi. It can be the same, or different, from the repurposed dimension of Space which is parallel to its instantaneous motion and changes generally every gyros, as discussed above. The details of how the router chooses one particular direction for connecting with the LAN are defined through Protocol 4 and lead to the realization that Dark Energy and Dark Matter naturally arise in the context of this theory.

3.5. Addresses of the LAN’s átmita

We now turn to the fundamental question of

what addresses will the átmita of the LAN in Figure 5b occupy, without collisions with the addresses of the átmita of Space. As mentioned already, the answer requires the notion of the finite memory of the átmita, discussed in

Section 3.2. Interestingly, the response to the above question leads to the realization that for every possible LAN configuration (i.e., for every particle type), there are another two fully-symmetric and mutually non-interacting versions.

The Protocol Process that allows an átmiton to claim an unoccupied address will be called “pinging”, in analogy to the relevant process of computer networks. A detailed discussion on it can be found in Supplementary Section ??; here we will note only the process itself:

Protocol Process 4 – Pinging

When placing a LAN of átmita on a substrate (or in Space), its átmita’s local addresses are translated to the substrate’s frame (and vice versa) by getting reflected by a surface of the substrate, utilizing the following recursive protocol:

The LAN’s router chooses one of its six ports (which connect it with its nearest-neighbors on the substrate) at random (each with an equal probability).

It looks for the first unoccupied address in that direction by performing a series of “pings” with progressively farther addresses. At each step of this pinging process, it broadcasts the candidate address and waits for an “occupied” signal, similarly to how a new telecommunication node on a network chooses its IP address.

If no such signal arrives, the process finishes and the address of each LAN átmiton is reflected from the last occupied address. Else, the address length in the chosen direction is increased by one stathmós and the process restarts. The surface of reflection will be called the “mirror” surface.

A visualization of the above process for a simple example case is depicted in Supplementary Figure ??.

In any case, the detailed evaluation of this process in Supplementary Section ??, leads to the following conclusion: If the LAN is closer than

(see

Section 3.2) to its mirror surface, then there will be an attractive force between the substrate and the LAN, caused by the open ports in the direction of the reflection. This force will cause the router

R to move towards the mirror surface and when it reaches it, the LAN will be turned into substrate, increasing its size. In

Section 5 (and Supplementary Section ??), it will be shown that this LAN-substrate interaction is responsible for some particles being unstable and massive (e.g., the

and

bosons), while others are not.

5. Átmiton Theory and the Microcosm

In this Section we will give a short outline of the properties of each of the Z-based second-order system with only Z-based internal LANs (i.e., systems). Each one will be suggested to be a particle of the Standard Model (SM).

In accordance with the approach we followed so far, the technical discussion and derivation of several results will be done primarily in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Sections ??-??); in the main manuscript we will focus on presenting these results, discussing their consequences and outline further avenues for future studies.

In particular, here we will try to understand qualitatively some important concepts of particle physics in the context of Átmiton theory, such as: What matter and antimatter is, what is EM charge, how spin is generated, what mass is and why some particles are stable and others not. Many of these will become apparent through a more thorough inspection (in the Supplementary Information) of the systems corresponding to the graviton, the photon, the boson and the electron (see Supplementary Sections ??-??).

Before we can study the properties of each

system, however, we should stop treating LANs as “black boxes” and try to understand how the internal LANs move on their substrate (

Section 5.1) and also what shape these LANs have (

Section 5.2). Both of these aspects are crucial to the discussion of the characteristics of each SM particle that will follow.

5.1. Relative Motion in Fields

When someone is walking on a moving train, the addition of their respective velocities (as seen by an outside inertial observer) is governed by Special Relativity. But both these motions happen ultimately in Space. What happens if an internal LAN is moving inside a substrate LAN, which moves in Space? Can both LANs move towards the same (address) direction during the next gyros? In that case, the address of a given átmiton in the internal LAN would change by 2 stathmoi at the same gyros.

Note that although the external LAN of such a system is indeed moving in Space (and its motion should obey Relativity), its internal LANs moves

on a field. Also, in

Section 3 the speed of light was defined as one hop (one stathmós) per gyros. It has not been clear so far how to generate speeds slower than that, since an átmiton obviously cannot move in a discrete lattice by a fraction of a stathmós during one gyros.

Here, this conundrum will be resolved (by adding an addendum to Protocol 2 – see Supplementary Section ??), by requiring that a nested LAN cannot move towards the same address-direction as its substrate LAN during the same gyros:

Protocol Process 2b – nested hops:

When LANs are nested inside other LANs, each layer cannot move during the same gyros at the same address-direction as one of the others. In other words, the address of any átmiton cannot change during one gyros by more than one unit per local coordinate.

As a consequence, an átmiton that is part of an internal LAN, embedded inside a substrate, having an address (in some coordinate frame) of (,,), in the next gyros should have (in the same system) an address (, , ), where , , = or 0.

This axiomatically-defined process is much less obvious than the rest (defined in

Section 3). However, in Supplementary Section ??, it is argued that if we don’t choose the

metric in order to calculate

, but use instead the integer quotient of metric

(i.e., the integer part of the Euclidean distance), then Protocol b can be understood in terms of Protocol 2a, given that an address-change of one unit per coordinate using this metric is still a distance of 1, but changing the same coordinate by 2 units results into a distance of 2 stathmoi.

In any case, there are strong arguments as to why such a statement is needed. In the Supplementary Information (Sections ?? and ??), it is shown that Protocol 2b makes the photon spin-1 (instead of spin-2) and more importantly, it acts as the source of mass and velocities lower than c: In the case of the photon (Supplementary Section ), the internal LANs rotate due to the photon’s specific topology only perpendicular to its substrate’s motion in Space (i.e., its spin is perpendicular to its momentum), so the photon’s router is free to move in Space with the speed of light and the particle has no mass. In contrast, in the case of the there is a LAN-substrate interaction that results in a motion of the internal LAN parallel to the substrate’s motion in Space (i.e., a longitudinal component of spin). Since Protocol 2b forbids the LAN and its substrate to move at the same gyros towards the same address-direction, the router of the has to stay still in Space during the gyroi that the internal LAN moves towards the direction of the particle’s momentum. Thus, this particle cannot move with the speed of light when averaged over many gyroi, even though on a gyros-by-gyros basis the boson moves in Space either with the speed of light (while its internal LAN moves perpendicularly to the particle’s momentum), or stands still (while the internal LAN moves parallel to its momentum).

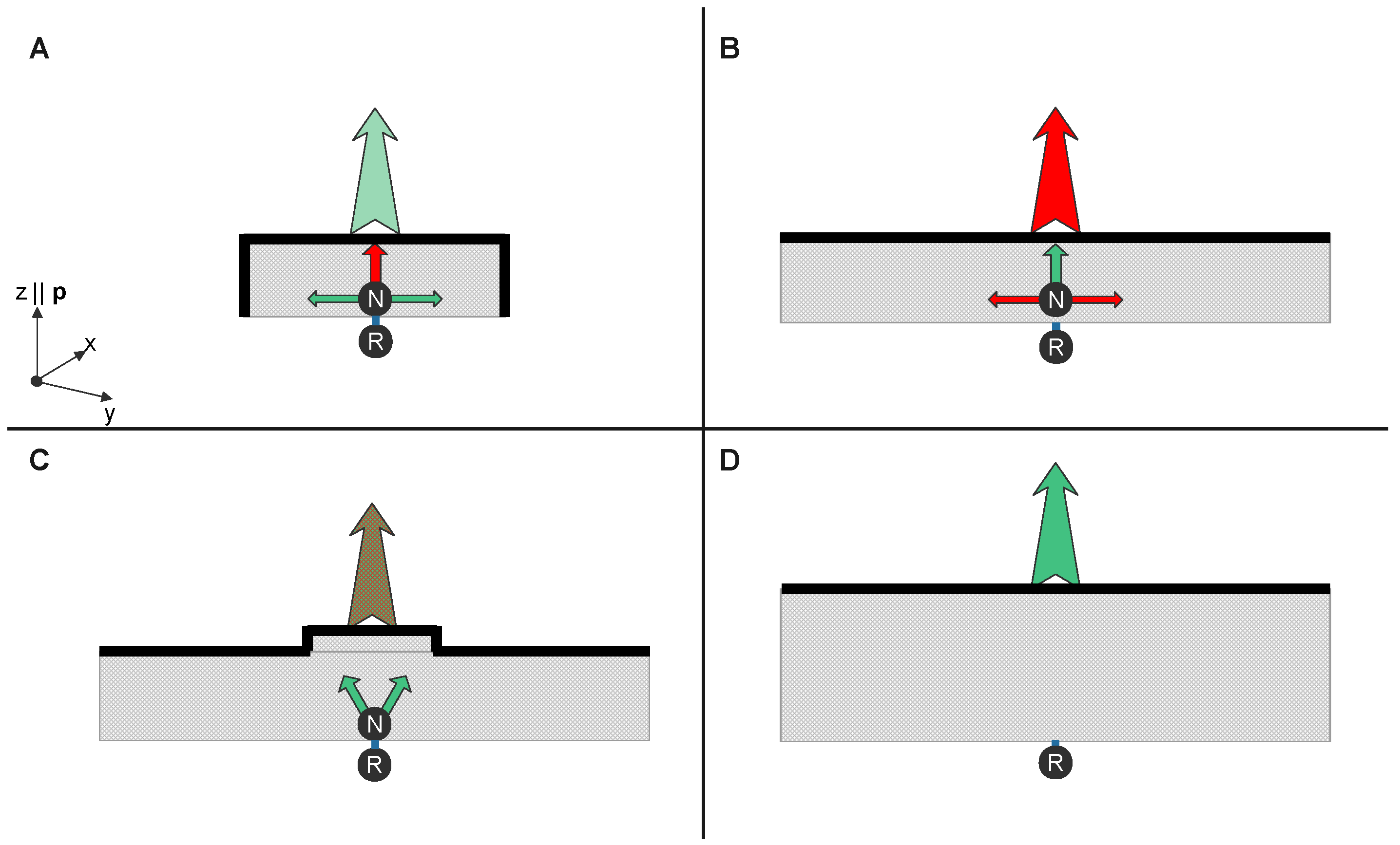

5.2. Shape of the LANs

Before we add LANs inside the substrates, we have to understand what shape a LAN can have. For instance, can we have a tower of átmita one on top of each other, parallel to the local z-axis? Can a LAN be shaped as a cube? Are its width, length and height arbitrary? The short answer is no.

To understand why, we note that in any Z-based particle, the addresses of the nearby átmita of Space are reflected by a faraway point on their z-axis. As an example, let’s consider a particle with its router being at point (,,) of Space, which will be moving towards either (,,) or (,,), with . From the point of view of an observer in Space, obviously in the first case the momentum of the particle is virtually parallel to the axis and in the second alternative parallel to . But when seeing from the point of view of an átmiton of the particle itself, the first point would be translated to its local frame as (,,) and in the second case as (,,). Both of them are effectively parallel to the local z-axis. (For a more thorough discussion on the reflection process when going between a LAN and its substrate see, e.g., Supplementary Section ??).

This means that when a Z-based particle is moving in (any direction of) Space, in its local frame it moves parallel to its z-axis, which therefore coincides effectively with the particle’s momentum direction in Space. In other words, the local z-axis of a Z-based particle can be considered effectively to be parallel to its momentum in Space.

Combining the above realization with Protocol 2b, means that if one tries to construct a LAN by adding átmita gradually, these will have the tendency to fill first the open ports of the LAN’s surface átmita on the nearest

-plane (see

Figure 8). This is so, because the substrate is moving though space according to the particle’s momentum, hence in its internal local frame it moves parallel to the

z-axis, once every gyros. Consequently, the átmita that try to fill holes on the surfaces of the substrate LANs cannot also move towards the local

z-axis (of the substrate) without stopping the particle’s motion in Space, but they can move on the local

-plane with no problem (

Figure 8a).

Therefore, when one adds átmita to a (Z-based) LAN, they will first fill the open ports on the nearest

-plane, until all open ports on the plane are more than

stathmoi away (see

Section 3.2), in which case the added átmita won’t “see” the holes on the

-plane any more, they will be out-of-bounts of their memory (

Figure 8b). Now, they can only interact with the holes at the local

z-direction and they will increase the height of the LAN by one stathmós, thus creating new

-signals closer than

(

Figure 8c).

Note that while the internal átmita move parallel to the local z-axis to fill the said holes, the particle cannot be moving in Space (Protocol 2b). In Supplementary Sections ?? and ??, where the structures of the photon versus the are showcased, it is made clear that due to the above mechanism, all unstable particles should have mass.

The result of the above process is that by construction, all LANs of átmita have a quasi-2D shape: Their surfaces with -holes are out-of-bounds in the Z-based particle’s router’s memory (thus they do not interact with anything), while their surfaces with z-holes are much closer to the particle’s router than (the limit of the LAN’s z-axis thickness is discussed in Supplementary Section ??). From this we conclude that the only important surfaces when we consider a Z-based particle are the ones which are normal to the local z-axis.

By symmetry, this means that for X-based matter the local x-axis is effectively parallel to the DE particle’s momentum in Space and similarly for the Y-based DE. Also, this explains the lack of interactions between RM and Dark Matter: Since the DM particles have their internal LANs reflected by a point on the local -plane of the substrates and the -plane width is on the order of , their signals become out-of-bounds when arriving in z-reflected internal LANs (i.e., when they arrive at any particle of regular matter, see Supplementary Section ??).

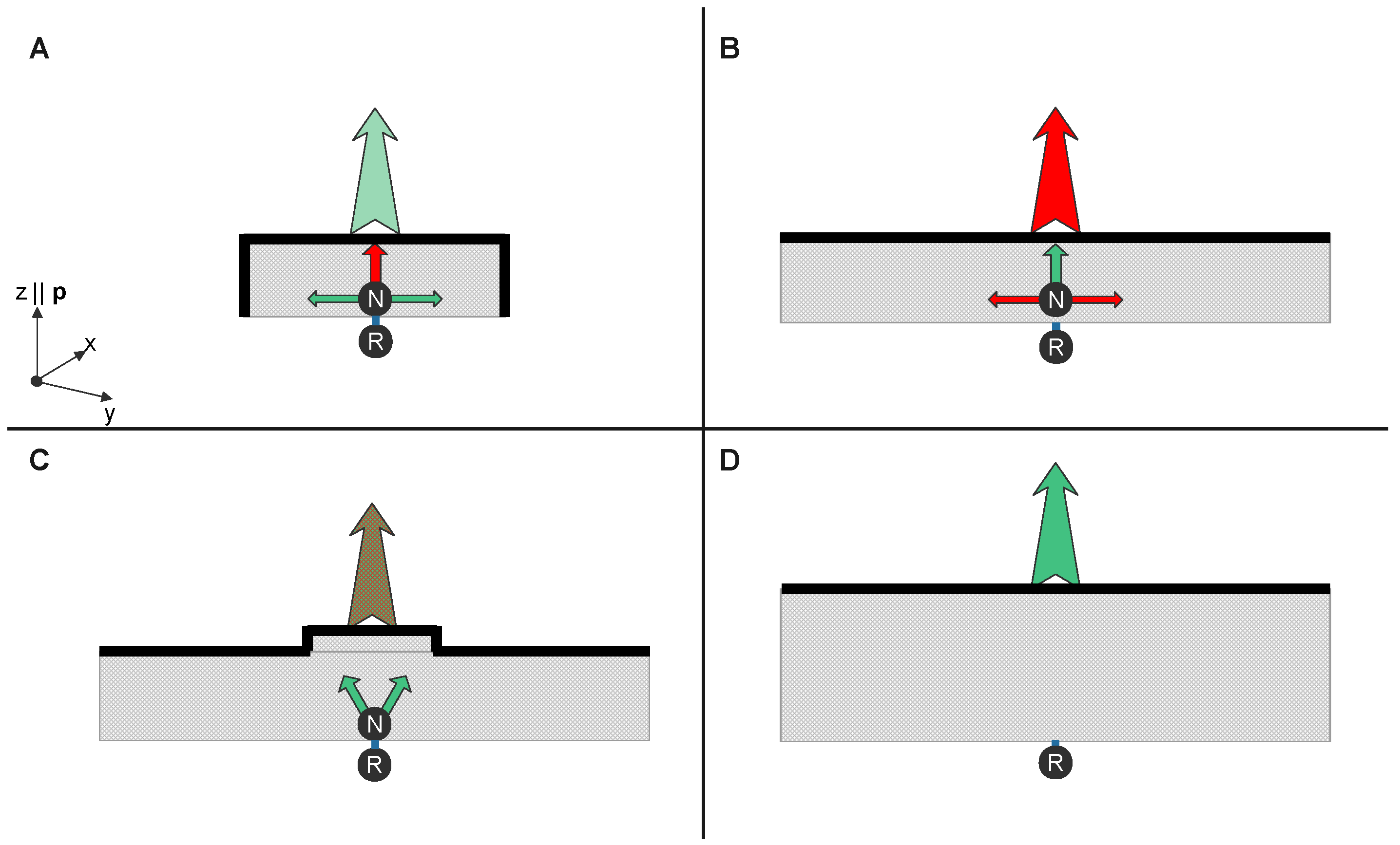

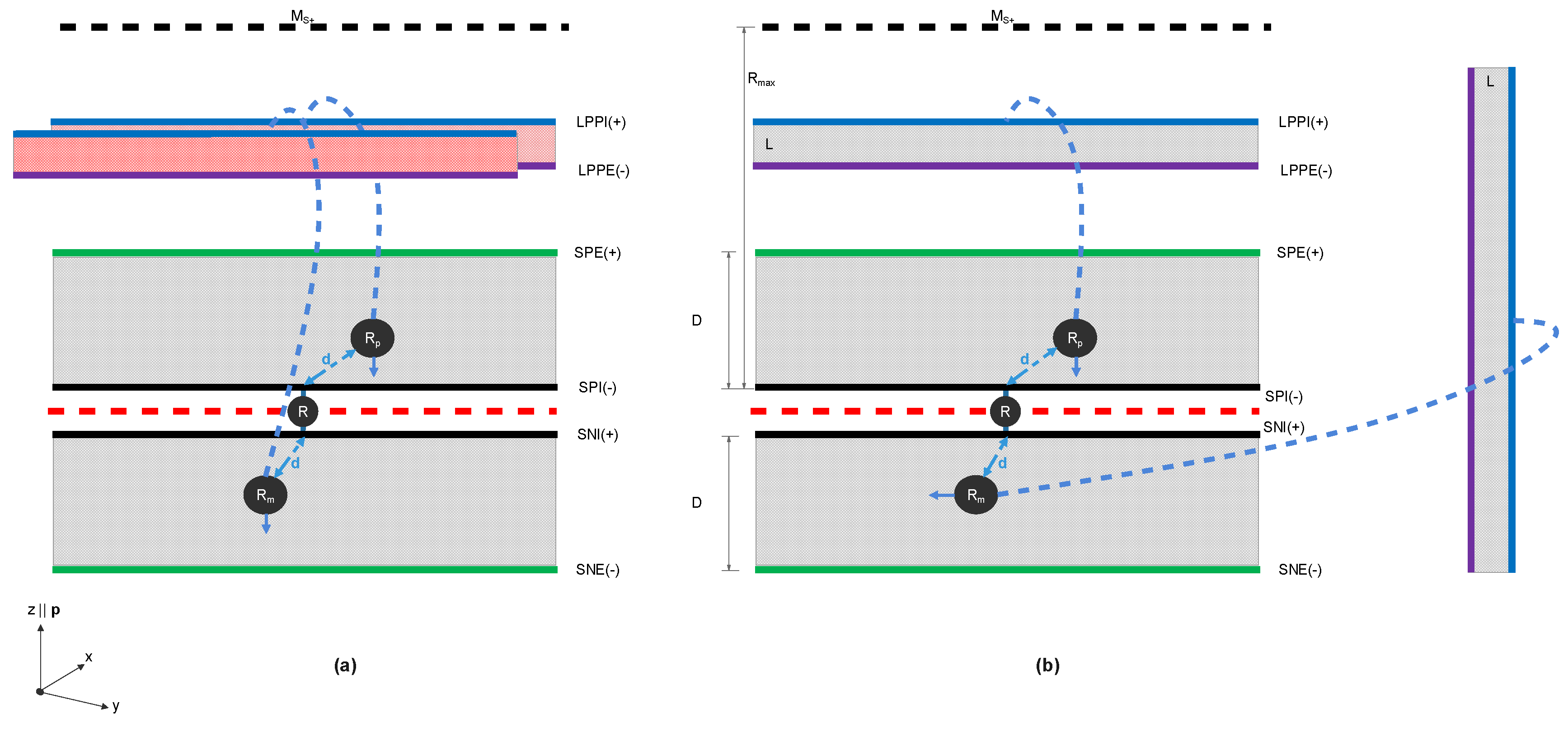

Based on the above considerations, the

system can be presented

at its router’s local frame as shown in

Figure 9. The two LANs are connected through the router and each LAN has two relevant surfaces, normal to the local

z-axis (green and black thick lines). The surfaces normal to the local

x- and

y-axes are omitted as irrelevant, since they are (on the order of)

stathmoi away from router

R and thus out-of-bounds.

In the Supplementary Information (Section ??)

is identified to be the graviton and it is shown that the internal surfaces (denoted as SPI(-) and SNI(+) in

Figure 9) generate its spin, while the external ones (surfaces SPE(+) and SNE(-) of

Figure 9) create a Force with most characteristics one would expect from Gravity. The nomenclature of the LANs’ surfaces is discussed in Supplementary Section ??, while Supplementary Section defines the limits of the thickness of each LAN of a

Z-based particle.

5.3. Corresponding Each Second-Order System with a Standard Model Particle

As discussed in

Section 4.4, to form particles of regular matter one should place inside either (or both) substrate(s) of a

system one of the three possible first-order systems, namely:

,

or

.

As a result, all possible RM systems (i.e., second-order systems with the symmetry) can be denoted as , where k, . The index signifies a LAN, an embedded and the addition of a system in one of the particle’s substrates. The raised index defines the structure of the positive substrate and the lowered index that of the negative substrate.

Here, we will pair each such system to one particle of the Standard Model (see

Table 2). The justification of the choices presented in

Table 2 (third column) is based on the discussion of

Section 5.4-

Section 5.10 (and on the detailed study of some of them in the Supplementary Sections ??-??), in which several characteristics of each particle are identified.

An important thing to note is that we cannot place a second embedded first-order z-based system on the same substrate: Adding, e.g., two

LANs in the same substrate (i.e., making the fictitious

) would result in them occupying the same address volume, which is prohibited by Axiom 3. Also, adding a

and a

LAN on the same substrate would result to them forming a

system, as explained in

Section 4.2.1. This means that the list presented in

Table 2 is exhausting, at least regarding second-order systems with only

z-type components.

Nonetheless, the above argument does not prohibit the addition of x- or y-based LAN(s) on a substrate already containing a z-based component. Indeed, in

Section 5.8 such combined systems will be noted as a possible way of forming the higher-generation fermions (a possibility that might also result in them interacting with Dark Matter particles in other ways except for Gravity).

5.4. Matter/Antimatter

In

Table 2 it is evident that the suggested particle/antiparticle pairs have symmetric structures. If we place a particle’s router in Space at point (

,

,

), then that particle’s antimatter counterpart would have the mirrored structure, with all internal LANs reflected by the surface

(see Supplementary Figure ??). For example, in

Table 2 it is noted that

corresponds to

and

to

.

But why matter cannot change into antimatter and vice versa? In the coordinate system of Space, the addresses of the upper LAN are reflected by the surface normal to

and the other LAN’s by

(where

is the direction of the particle’s momentum in Space, see

Section 5.2 and Supplementary Sections ??-??), so their address distance is

. But from the point of view of each substrate, the other substrate is just two stathmoi away on the local

z-direction (see

Figure 9), with an impassable wall between them (the

surface). They cannot cross it, because the addresses of this surface are already fully occupied by Space átmita, with no open ports (see Protocol 2a). This means that

the positive and negative substrates can only communicate through the router and they cannot change sides.

Thus, a LAN embedded in the positive substrate cannot cross to the negative one (and vice versa). The impassable wall at the (local) surface is why there isn’t any matter-antimatter mixing between such systems.

This leads also to an experimentally verifiable prediction of Átmiton theory:

Neutrinos are Dirac, not Majorana [32], particles, as

/

is distinct from

/

and due to the impassable wall of the

surface, they cannot convert from one to the other. This, of course, is in line with the absence of any neutrino-less double

-decay observations hitherto [

69].

5.5. Charge Conjugate

From

Table 2, it is evident that bosons have an even number of internal LANs and a symmetric internal structure, whereas fermions have an odd number of LANs and an anti-symmetric structure. In other words, the

reflection of the positive and negative substrates by the

surface does not change anything for the

/G and the

/H particles, whereas it would only change the sign of the W-bosons (

). Interestingly, this transformation turns the

/

to the

/

and vice versa, making the

boson effectively the antiparticle of the photon. The reason of their very different masses and half-lives is discussed in detail in the following sections and in the Supplementary Sections ?? and ??.

On the contrary, fermions have distinct antiparticles, in the sense that the reflection of their structure from the surface would turn them into distinctly different particles, e.g., the / to /.

5.6. Spin

The substrate structure depicted in

Figure 9 is shared by all

particles. Therefore, the study of the properties of its four

-surfaces (see Supplementary Sections ??-??) offers important results that are applicable across all particles of regular matter.

Turning first to surfaces SPI(-) and SNI(+), in the Supplementary Section ?? is detailed how their interaction generates the particle’s spin. In a nutshell, the way spin arises from the interaction of these two surfaces is as follows (see Supplementary Figure ??):

This pair of surfaces are as close to each other as any such surface could ever be, thus they can only interact with one another. Nonetheless, when we say that two surfaces interact, this really means that individual átmita belonging in the said surfaces form connections. But an individual átmiton of the SNI(+) surface can come closer to a specific átmiton of SPI(-), with which it interacts: The two surfaces communicate only through the router, meaning that the closer an átmiton of one of the two internal surfaces is to the router, the closer (in the sense of connection distance ) is to its interacting counterpart of the other surface. But the specific átmita of the positive and the negative substrates that connect to the router (i.e., the gateway átmita and ), can change if the whole substrate moves horizontally (on the -plane) in respect to the router. In other words, the two substrates of every RM particle are free to move horizontally in respect to each other, in a grinding-like motion.

This causes a fluctuation of all forces felt by other particles, as the distance of particular átmita from their particle’s router fluctuates with time. Using an ansatz claiming that this fluctuation repeats every period (which needs to be proven in a dedicated publication), in the Supplementary Sections ?? and ??, it is shown that due to this grinding motion and their specific topologies, the graviton has spin-2, while the photon spin-1. Also, in Supplementary Sections ?? and ??, it is established that the electron should have fractional spin and that the boson should have spin twice that of the electron. Although this is a weaker conclusion, as it is not proven yet that the electron has spin-1/2, further advances on the specific form of the átmita’s communication protocol and a dedicated publication might establish the exact value of the electron’s spin.

5.7. Stability

Another easily identifiable pattern that emerges from

Table 2 relates to the structures that result in stable or unstable particles. As a rule of thumb, an internal LAN that is reflected by the external surface of the substrate on which it lies (i.e., reflected by the SPE(+) surface for the positive and SNE(-) for the negative substrate (see, e.g., Supplementary Figure ??) results in an unstable particle. This is because the internal LAN can interact with its mirror surface and propagate towards it to close its open ports, effectively turning itself into substrate, exactly like the situation studied in Supplementary Section ??. In

Section 4.4, this effect was used to calculate the percentage of DM.

On the other hand, cross-reflected internal LANs, such as an internal LAN lying at the positive substrate that is reflected by the SNE(-) surface (and vice versa), lead to stable structures, as these internal LANs cannot cross from their substrate to the opposite one (

Section 5.4), in order to reach their mirror surface (see

Figure 10). In the Supplementary Information, this is rigorously demonstrated for the (stable) photon and the electron versus the (unstable)

boson (Sections ??-??).