1. Introduction

Poultry production is one of the primary sources of animal protein and a sector of significant socioeconomic importance worldwide. According to the

FAO Food Outlook, global poultry meat production reached approximately 146 million tons in 2024, consolidating its position as the most produced meat worldwide [

1]. Projections from the

OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2024–2033 estimate that global poultry meat consumption may exceed 160 million tons by 2033, reflecting a sustained upward trend in demand [

2]. This scenario underscores the need to optimize production systems through strategies that enhance efficiency, sustainability, and animal welfare.

In small- and medium-scale rural farms, as well as in semi-free-range systems, daily tasks—such as opening and closing enclosures, manually dispensing feed, and monitoring bird health—impose a substantial operational burden and are susceptible to human error. Furthermore, feed access by non-target species (e.g., pigeons or other wild animals) results in economic and sanitary losses, compromising profitability and zoosanitary control. Existing automatic feeding systems have been developed primarily for confined or industrial environments, limiting their applicability in open rural settings with limited technological infrastructure [

3].

Computer vision and deep learning techniques have revolutionized precision agriculture, enabling the automation of real-time monitoring and management processes. In particular, object detectors from the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family—especially YOLOv8—have demonstrated an exceptional balance between accuracy and inference speed, making them well suited for field applications with limited computational resources. Recent studies have optimized this model to enhance detection performance in high-density and occluded environments, demonstrating its potential for complex poultry counting and tracking tasks [

4,

5].

Additionally, the availability of low-cost platforms such as Raspberry Pi, combined with the development of edge computing strategies, has enabled local inference execution without constant connectivity, thereby reducing latency and enhancing responsiveness in rural environments [

6]. These implementations have been validated in intelligent poultry systems integrating computer vision, deep learning, and low-power embedded hardware [

7].

Despite these advances, significant technological gaps remain in the automation of poultry processes within free-range systems. Most studies on computer vision in poultry farming focus on counting or health monitoring in controlled environments, whereas few integrate selective hen detection with a physical actuation mechanism—such as automatic feed dispensing—under limited energy availability and low-cost constraints. This methodological gap limits the adoption of intelligent solutions in rural communities and small-scale farms.

In response to this need, AVITRÓN is presented as a modular intelligent station for free-range poultry management, integrating computer vision, artificial intelligence, and mechatronic automation. The system incorporates a vision camera, a YOLOv8 model trained on local images, and a control mechanism for selective feed dispensing, enabling real-time hen identification and exclusion of non-target species.

The primary objective of this research is to develop and validate an autonomous intelligent station based on computer vision, capable of selectively detecting hens and controlling feed dispensing in free-range rural systems. From a scientific perspective, this study aims to demonstrate the feasibility of applying real-time detection models in open rural environments by integrating computer vision and mechatronic control within a single system. In parallel, the practical objective is to design a functional and accessible prototype that optimizes feed management through automated detection and selective control, thereby reducing input losses and enhancing animal welfare. At this stage, AVITRÓN constitutes a solution with the potential to contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), and SDG 12 (Responsible Production and Consumption), by fostering more efficient and sustainable agricultural practices in rural environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Description of the System

The AVITRÓN system was designed as an autonomous, modular solution intended to optimize feed management in free-range production systems. Its purpose is to automate selective dispensing through intelligent bird detection, ensuring that only authorized hens access the feed while minimizing the need for manual supervision.

The architecture comprises three main components: (i) a computer vision module for real-time detection, (ii) an embedded processing unit responsible for inference and control, and (iii) a mechatronic dispensing system. These subsystems operate in a coordinated manner while maintaining functional independence and fault tolerance, ensuring reliable performance in rural environments with limited resources [

8].

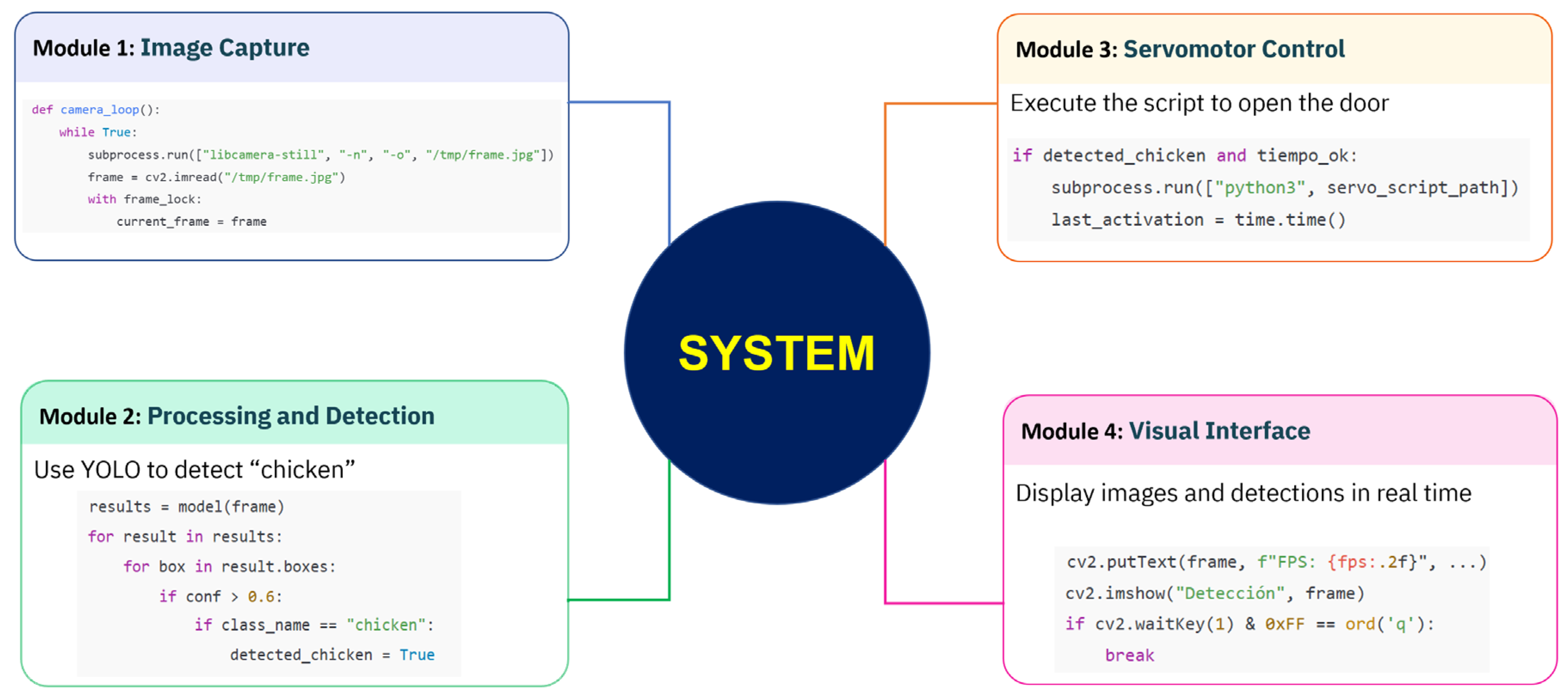

Figure 1 illustrates the modular structure of the AVITRÓN system, consisting of four modules: (i) image capture, (ii) processing and detection using YOLOv8, (iii) servomotor control, and (iv) real-time visualization.

2.2. Hardware Architecture

The system’s embedded processing unit is built around a Raspberry Pi 5, selected for its balance between processing capability and compatibility with deep learning models [

9]. Visual data acquisition is carried out using a Raspberry Pi AI Camera Module 3 connected via the Camera Serial Interface (CSI), which captures RGB images of the dispensing area.

The actuation module employs an MG996R servomotor responsible for operating the feed hopper gate. The system operates on two independent 5 V DC power sources: one dedicated to the Raspberry Pi and the other to the servomotor, preventing voltage drops and excessive load on the main system caused by the actuator’s high current demand during mechanical activation. The prototype was constructed using transparent acrylic, a lightweight and durable material that protects components from dust and moisture while allowing direct visual inspection. This architecture ensures operational stability, scalability, and low maintenance, making it well suited for rural conditions with limited infrastructure.

2.3. Computer Vision Model

The selective hen detection system was developed using a computer vision model trained with a dataset composed of 402 original images, expanded to 966 effective samples through data augmentation techniques. This strategy has proven effective for detecting small objects in visually complex environments [

10]. The images were collected from public sources (Roboflow, Kaggle Poultry Dataset) and selected to represent heterogeneous conditions of lighting, distance, angle, and background, in order to emulate real rural scenarios.

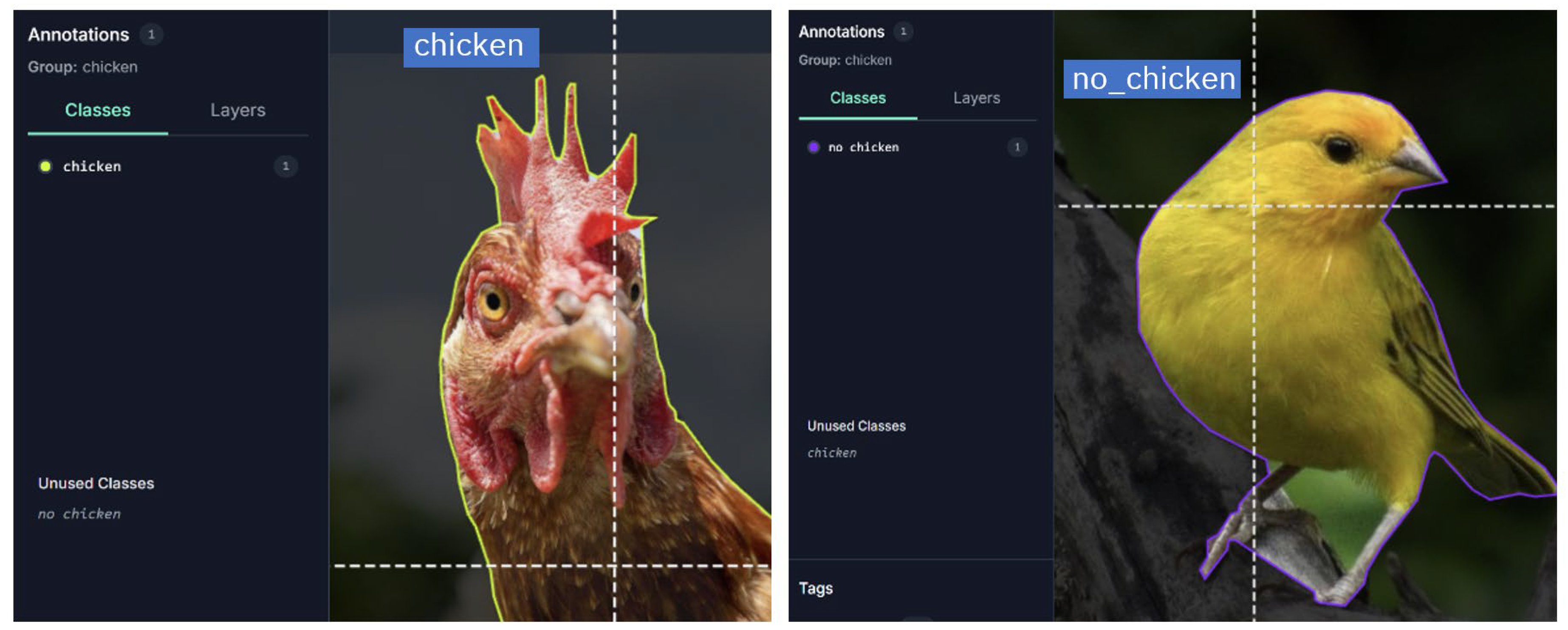

The dataset was managed and preprocessed using the Roboflow platform, where the images were manually annotated with instance segmentation, precisely defining pixel-level contours for two classes: chicken (hens) and no_chicken (non-target birds such as pigeons or doves). Although the original annotations were generated as masks, training was conducted strictly in YOLOv8 detection mode (task = detect). For this purpose, the segmentations were automatically converted into bounding boxes, and all reported metrics (mAP, precision, recall, and F1-score) correspond to the model’s performance in object detection, not segmentation.

Figure 2 shows representative examples of annotations for both classes. The annotations were verified to ensure internal consistency and class balance before training, discarding inconsistencies or incorrect labels.

The base model selected was YOLOv8-nano, an ultralight variant of the YOLO family optimized for real-time detection on devices with limited computational resources [

11]. Training was performed in Google Colab with GPU acceleration (Tesla T4) for 50 epochs using Ultralytics YOLOv8 (version 8.3.213) and PyTorch 2.8.0. The following parameters were used: batch size of 16, learning rate of 1.67 × 10⁻³, and input images of 640 × 640 px. The algorithm automatically partitioned the augmented dataset into 846 images for training, 81 for internal validation, and 39 for internal testing.

During training, the metrics mAP@0.5 (bounding box), precision, recall, and F1-score [

12] were monitored, all calculated on the internal validation set automatically generated by YOLOv8 (81 images). The selected model (best.pt) corresponded to the checkpoint with the highest mAP@0.5 and the best precision–recall balance. Subsequently, it was exported using TorchScript to ensure compatibility with ARM architectures and stable execution on the Raspberry Pi 5. The feasibility of this platform for running deep learning models at the edge has been demonstrated in recent research [

13,

14].

This process enabled the model to run directly on the embedded device without reliance on Python environments, reducing latency and resource consumption during inference.

2.4. Software–Hardware Integration and Dispenser Control

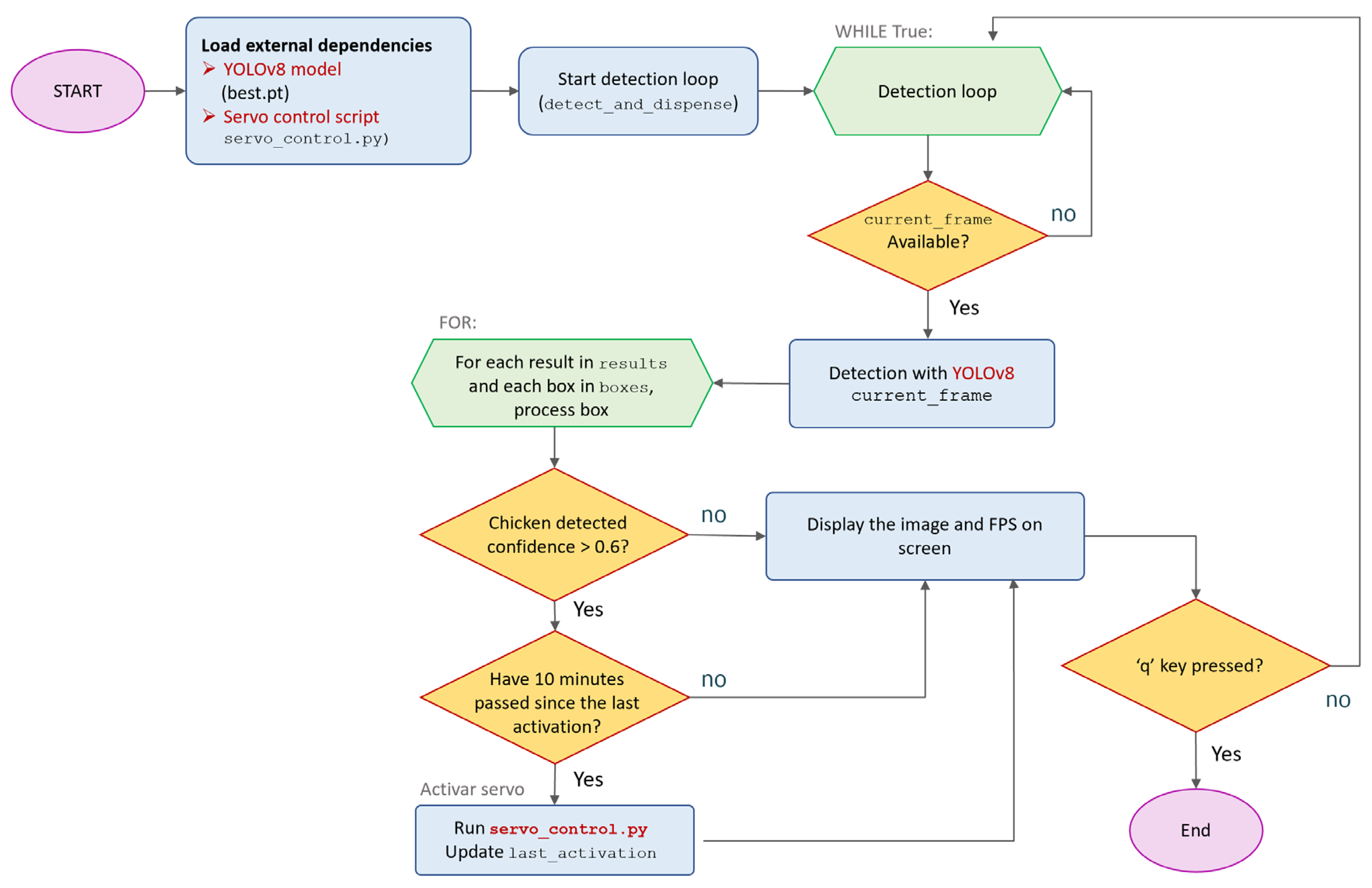

Figure 3 shows the logical sequence of the detection and control process, including the execution flow of the main code. The system initiates image capture, processes each frame with YOLOv8, and activates dispensing only when the detection conditions and the minimum time interval between activations are met.

The system integration was developed in Python, structuring parallel processes for image capture, inference, and actuator control. The operational flow is based on continuous image acquisition from the AI camera, real-time processing using the YOLOv8 model, and decision-making based on confidence thresholds and temporal persistence criteria.

When the system detects a hen with a confidence level above 0.6 and maintains this detection across several consecutive frames, a PWM signal is generated to activate the servomotor, producing a 90° rotation for 60 s (adjustable as required), which opens the gate for feed dispensing before a delay is applied to prevent successive activations. Subsequently, a temporal delay is triggered to avoid repeated activations and ensure controlled feed dosing.

Safety routines were implemented to close the gate in the event of camera failure, execution errors, or power interruptions, preserving system integrity. This integrated architecture enables autonomous, stable, and reproducible operation under field conditions, ensuring fault tolerance and safe recovery of the operational state.

2.5. Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

The prototype was validated using an independent set of 144 images (≈15% of the total), different from those used in training. This set included both chickens (chicken) and non-target species (no_chicken), captured under heterogeneous lighting and background conditions.

Performance was evaluated using a confusion matrix, from which precision, recall, F1-score, and overall accuracy metrics were calculated based on the model’s classified predictions. Validation was conducted directly on the Raspberry Pi 5 using the final optimized model (best.pt), exported to TorchScript format, without additional weight adjustments or retraining. Performance metrics were recorded from real-time local inferences, replicating the operating conditions of the embedded system. These results confirmed the real-time functionality of the device (Camera–Raspberry Pi–Servomotor–Gate) and its consistency in selectively detecting chickens versus non-target species.

The quantitative results are presented in

Section 3, where performance metrics and system effectiveness under varying lighting and environmental conditions are analyzed.

Taken together, the findings confirm that the integration of intelligent detection and embedded control can be effectively implemented on low-cost platforms, validating the potential of AVITRÓN as a precision agriculture tool.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Functional Prototype and Component Integration

The AVITRÓN prototype was assembled by integrating the capture, processing, and actuation modules into a single unit (

Figure 4). The device includes a 4 mm acrylic chassis, an MG996R servomotor for the gate, and a vision module based on a Raspberry Pi 5 (8 GB RAM) with a 12 MP AI camera.

During calibration, the camera angle was set to 35° relative to the feeder plane, and the servomotor activation delay was set to 1.5 s. A confidence threshold of 0.60 was selected for dispenser activation in the tests described below (see

Section 3.3 for the justification based on PR curves).

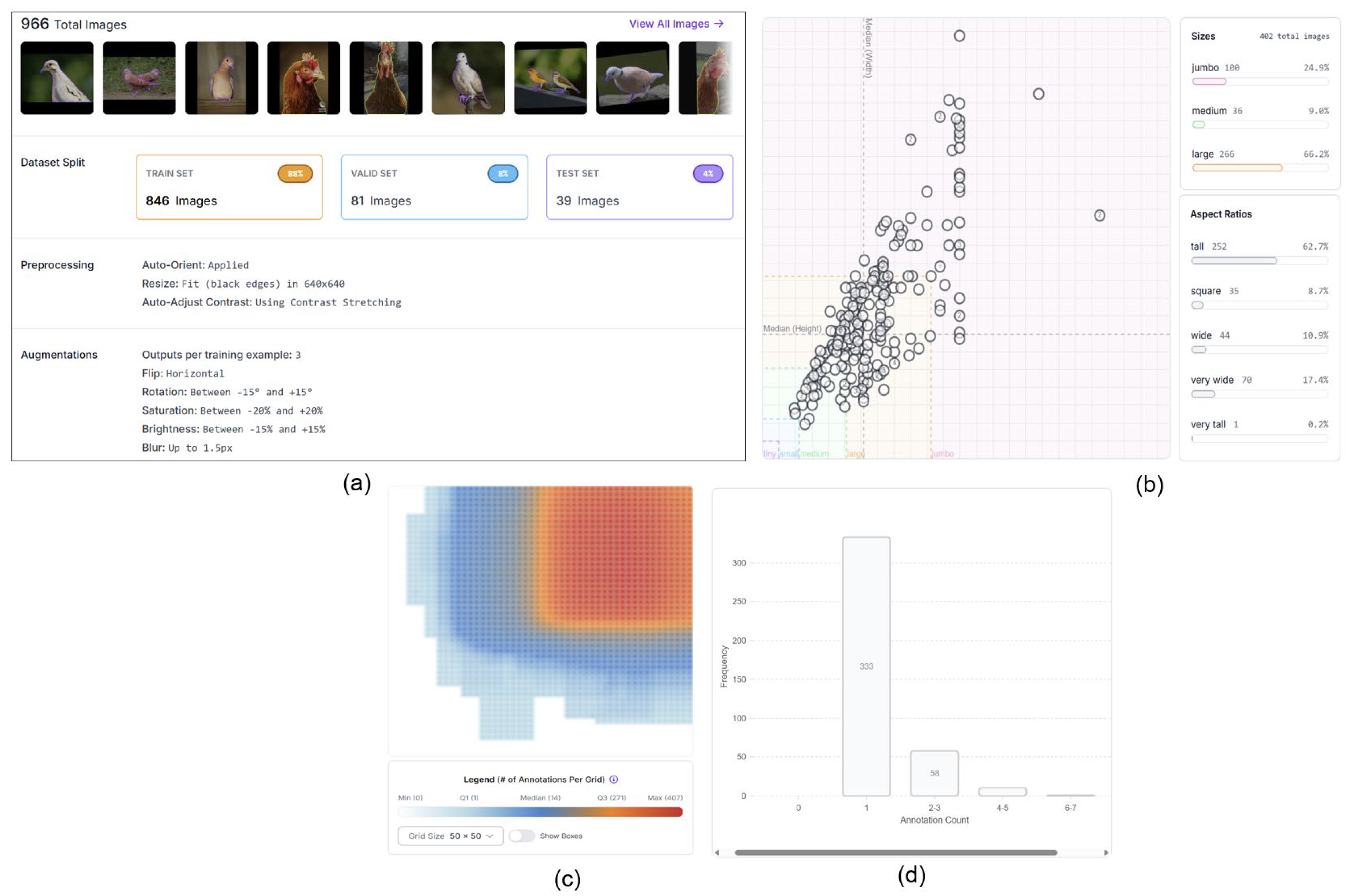

3.1.1. Dataset Characterization

The structural analysis of the dataset was performed using the Dataset Analytics function available in Roboflow to assess class balance, label consistency, and suitability for training the YOLOv8 model (

Figure 5a).

The final set comprised 966 images with 513 annotations distributed between the classes chicken (58.7%) and no_chicken (41.3%). The average resolution was 0.41 MP, ranging from 0.05 to 3.44 MP, with an average dimension of 612 × 700 px. A vertical format predominated (62.7%), consistent with the natural posture of the birds in front of the dispenser.

The dimensional analysis (

Figure 5b) showed that 66.2% of the images were classified as large and 24.9% as jumbo, ensuring sufficient resolution for learning fine morphological features.

The annotation histogram (

Figure 5d) showed that 85.2% of the images contain a single instance, reflecting simple and well-defined scenes.

The annotation heatmap (

Figure 5c) revealed a high central density (up to 407 annotations per cell), consistent with the frontal region of the dispenser, and low density in the periphery, which minimizes contextual noise. This controlled spatial concentration supports the internal coherence of the dataset and its correspondence with the operational environment of the AVITRÓN system.Overall, the results confirm that the dataset is structurally consistent, balanced, and representative of real operating conditions, providing a solid basis for model training and validation.

3.2. Model Training Results

The YOLOv8-nano model was trained for 50 epochs using the augmented dataset of 966 samples. The automatic partitioning produced 846 images for training, 81 for internal validation, and 39 for internal testing. The total training time was approximately 13 minutes.

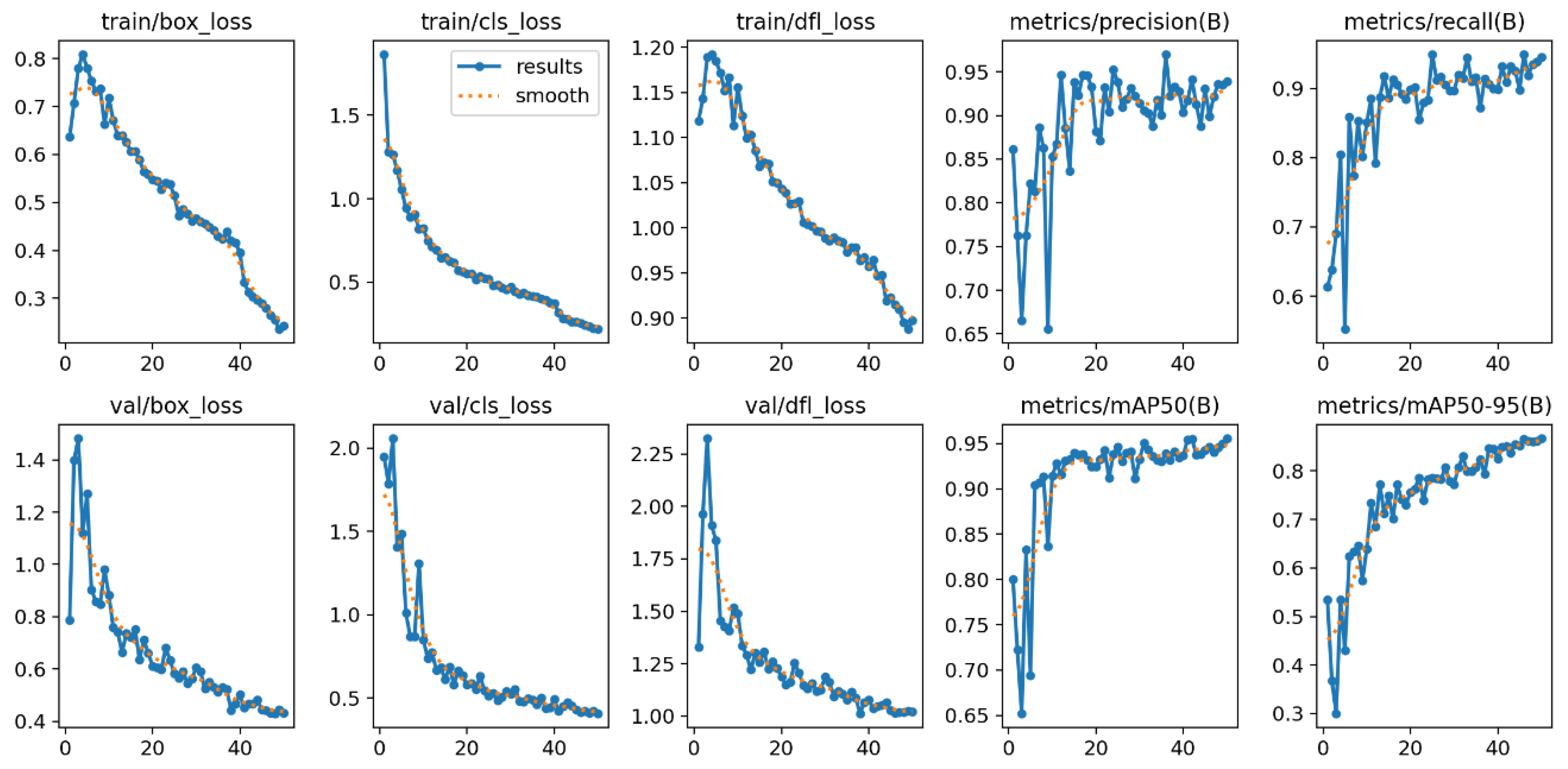

The loss curves (

Figure 6) show a progressive and stable convergence for both training and validation, with no evidence of overfitting. The validation loss stabilized around 0.05 from epoch 38 onward, indicating an appropriate balance between learning and generalization.

The performance metrics were calculated on the internal validation set (81 images), automatically generated by YOLOv8 from the augmented dataset. The results obtained using the COCO API integrated into Ultralytics reached mAP@0.5 = 0.96 and mAP@0.5:0.95 = 0.87, while overall precision and recall were approximately 0.94 and 0.95, respectively, with an average F1-score of 0.94. These metrics reflect the model’s behavior during the validation process prior to its final evaluation on the independent test set.

The Recall–Confidence, Precision–Confidence, and Precision–Recall curves indicate appropriate model calibration, with stable performance across detection thresholds. Overall, these results confirm the strong generalization capacity of the lightweight YOLOv8-nano model for real-time detection tasks in rural environments. This behavior is consistent with recent literature reporting similar performance for compact YOLOv8 variants applied to animal monitoring and smart agricultural systems [

6,

15].

3.3. Performance on Independent Validation

The final evaluation was conducted on an external set of 144 images that were not used during training. The validation scenes represented heterogeneous rural conditions, with variations in lighting, distance, and background composition. The confusion matrix obtained during validation (

Table 1) summarizes the model’s performance for the classes

chicken (target birds) and

no_chicken (non-target birds).

Based on this matrix, the following key performance metrics were obtained:

Accuracy: 0.986

Precision (chicken class): 1.000

Recall/Sensitivity (chicken class): 0.968

F1-score: 0.984

95 % CI (accuracy): [0.950, 0.998]

Kappa: 0.971

The model achieved an overall accuracy of 98.6%, with perfect precision (1.000) and a recall of 96.8%, demonstrating highly reliable detection performance and a minimal omission rate. The strong agreement (κ = 0.971) confirms the consistency between the model’s predictions and the ground truth.

In operational terms, 60 true positives (TP), 2 false negatives (FN), 0 false positives (FP), and 82 true negatives (TN) were recorded. This result indicates that the system did not trigger the gate erroneously in any case (FP = 0), demonstrating highly reliable servomotor control when exposed to visual stimuli from non-target birds.

These findings are consistent with previous studies on the deployment of lightweight YOLOv8 models in agricultural and animal monitoring contexts, where reported precision values range from 0.88 to 0.94 and latencies remain below 150 ms on embedded

platforms [

16,

17,

18].

The performance achieved (mAP@0.5 = 0.93; F1 = 0.984) is consistent with recent studies on lightweight YOLOv8 models deployed on Raspberry Pi, where reported precision values range from approximately 0.91 to 0.94 and inference times are suitable for edge applications [

19,

20].

Given the limited size of the validation set (n = 144), the results should be interpreted as an initial estimate of performance under the evaluated conditions. Future research aimed at expanding the validation set (≥300 samples), incorporating low-light scenarios, and conducting direct comparisons with reference models (YOLOv5-nano, MobileNet-SSD) will help consolidate and generalize the findings.

Overall, these advances position AVITRÓN as an accessible, scalable, and sustainable precision agriculture tool for the automated management of feed in rural free-range systems.

4. Conclusions

This study developed and validated AVITRÓN, an autonomous intelligent station for the selective dispensing of feed to free-range hens, integrating computer vision, deep learning, and embedded mechatronic control. The results confirm the system’s technical and functional feasibility in rural settings with limited infrastructure, establishing a solid foundation for the automation of poultry processes through edge-based artificial intelligence.

The YOLOv8-nano detection model achieved robust performance (mAP@0.5 = 0.93; F1 = 0.98), with an appropriate balance between precision and sensitivity, and stable real-time operation on a Raspberry Pi 5. The integration of the vision system with the mechatronic module enabled reliable automation of feed delivery, minimizing human intervention and reducing access by non-target species. These outcomes demonstrate that lightweight AI combined with embedded hardware offers a viable pathway toward the sustainable automation of rural poultry systems.

From a scientific perspective, this work provides a reproducible implementation of a complete embedded detection and control workflow, combining the export of the YOLOv8 model in TorchScript format with real-time PWM control. In practical terms, the proposed prototype validates a low-cost, accessible, and scalable alternative capable of improving feeding efficiency and promoting animal welfare in free-range systems.

However, the results should be considered preliminary due to the limited size of the validation set (n = 144). It is recommended to expand the image set (≥300 samples) and incorporate scenarios with variable lighting, partial occlusions, and the simultaneous presence of multiple birds to strengthen the model’s generalization capacity. Future versions of the system could integrate solar power modules, IoT connectivity, and adaptive control, advancing its evolution toward a fully autonomous and sustainable platform.

Overall, AVITRÓN represents a significant contribution to the advancement of smart agricultural automation, demonstrating that the convergence of computer vision and embedded hardware can transform poultry management in rural environments. Its implementation aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 2, 9, and 12) by promoting more efficient, innovative, and responsible production practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.-S. and J.F.V.-E.; methodology, S.G.-S. and J.F.V.-E.; software, J.J.R.-B.; validation, S.G.-S. and J.P.C.-S.; resources, S.G.-S. and J.P.C.-S.; data curation, S.G.-S. and J.P.C.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.-S. and J.P.C.-S.; writing—review and editing, S.G.-S. and J.P.C.-S.; visualization, J.J.R.-B.; supervision, J.F.V.-E.; project administration, S.G.-S. and J.P.C.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the World Robot Olympiad (WRO) for inspiring the initial conception of the AVITRÓN project. They also express their gratitude to the rural community of Quindío for their valuable collaboration, and to GI School, especially Mr. Andrew Roberts and his team, for the institutional support provided during the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| COCO |

Common Objects in Context (dataset and evaluation metric) |

| FPS |

Frames Per Second |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| IoU |

Intersection over Union |

| mAP |

mean Average Precision |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| PWM |

Pulse Width Modulation |

| RGB |

Red, Green, Blue (color model) |

| YOLO |

You Only Look Once |

| RP |

Raspberry Pi |

| PR |

Precision–Recall |

References

- FAO. Meat and Meat Products Outlook: Global Market Analysis – July 2024. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/3/cd1158en/CD1158EN_meat.pdf (accessed on Oct 7, 2025).

- OECD-FAO. Agriculture and fisheries. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/oecd-fao-agricultural-outlook-2024-2033_9e58b4f0-en (accessed on Oct 7, 2025).

- Cakic, S.; Popovic, T.; Krco, S.; Nedic, D.; Babic, D.; Jovovic, I. Developing Edge AI Computer Vision for Smart Poultry Farms Using Deep Learning and HPC. Sensors 2023, 23, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Fang, C. Enhanced Methodology and Experimental Research for Caged Chicken Counting Based on YOLOv8. Animals 2025, 15, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Bist, R.B.; Paneru, B.; Chai, L. Deep Learning Methods for Tracking the Locomotion of Individual Chickens. Animals 2024, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, E.; Hidalgo-Rodriguez, M.; Acosta-Reyes, A.M.; Rangel, J.C.; Boniche, K. AI-Based Monitoring for Enhanced Poultry Flock Management. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmessery, W.M.; Gutiérrez, J.; Abd El-Wahhab, G.G.; Elkhaiat, I.A.; El-Soaly, I.S.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Akela, M.A.; Moghanm, F.S.; Abdelshafie, M.F. YOLO-Based Model for Automatic Detection of Broiler Pathological Phenomena through Visual and Thermal Images in Intensive Poultry Houses. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joice, A.; Tufaique, T.; Tazeen, H.; Igathinathane, C.; Zhang, Z.; Whippo, C.; Hendrickson, J.; Archer, D. Applications of Raspberry Pi for Precision Agriculture—A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovesan, D.; Maciel, J.N.; Zalewski, W.; Javier, J.; Ledesma, G.; Cavallari, M.R.; Hideo, O.; Junior, A. Edge Computing : Performance Assessment in the Hybrid Prediction Method on a Low-Cost Raspberry Pi Platform. eng 2025, 6, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suto, J. Using Data Augmentation to Improve the Generalization Capability of an Object Detector on Remote-Sensed Insect Trap Images. Sensors 2024, 24, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, O.G.; Ibrahim, P.O.; Adegboyega, O.S. Effect of Hyperparameter Tuning on the Performance of YOLOv8 for Multi Crop Classification on UAV Images. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Zhong, F.; Wang, L. Efficient Optimized YOLOv8 Model with Extended Vision. Sensors 2024, 24, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Ban, S.; Hu, D.; Xu, M.; Yuan, T.; Zheng, X.; Sun, H.; Zhou, S.; Tian, M.; Li, L. A Lightweight YOLO Model for Rice Panicle Detection in Fields Based on UAV Aerial Images. Drones 2025, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.; Ong, L.Y.; Leow, M.C. Exploring Distributed Deep Learning Inference Using Raspberry Pi Spark Cluster. Futur. Internet 2022, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y. Lightweight YOLOv8-Based Model for Weed Detection in Dryland Spring Wheat Fields. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Li, C.; Yang, P.; Kong, S.; Han, Y.; Huang, X.; Niu, J. Enhancing Livestock Detection: An Efficient Model Based on YOLOv8. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cao, S.; Wei, P.; Sun, W.; Kong, F. Dynamic Object Detection and Non-Contact Localization in Lightweight Cattle Farms Based on Binocular Vision and Improved YOLOv8s. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Diao, H.; Zhu, J.; Ji, D.; Liao, X.; Zhao, Z. YOLOv8 Model for Weed Detection in Wheat Fields Based on a Visual Converter and Multi-Scale Feature Fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, M.T.; Lopes, W.A.C.; Ruggero, S.M.; Vendrametto, O.; Fernandes, J.C.L. Edge AI for Industrial Visual Inspection: YOLOv8-Based Visual Conformity Detection Using Raspberry Pi. Algorithms 2025, 18, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, B.; Azhar, N.F.; Pratama, B.M.; Rusdianto, A.; Syakbani, A. Implementation of Sparrow Pest Detection Using YOLOv8 Method on Raspberry Pi and Google Coral USB Accelerator Implementasi Deteksi Hama Burung Pipit dengan Metode YOLOv8 pada Raspberry Pi dan Google Coral USB Accelerator. Sebatik 2025, 29, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).