Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

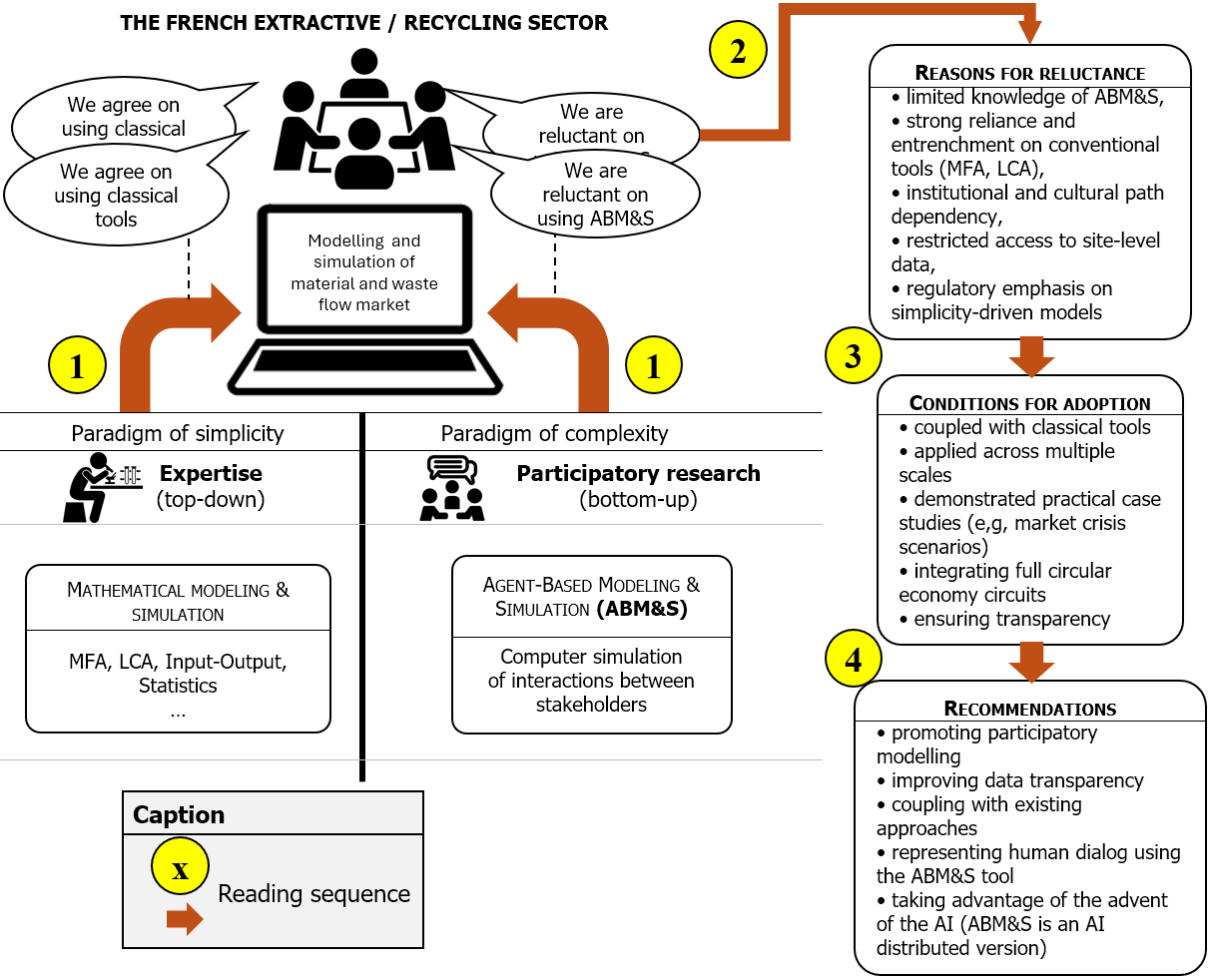

1. Introduction

- q1.

- what are the possible reasons for this reluctance?

- q2.

- under which minimum conditions the ABM&S could be accepted by the sector?

- q3.

- how could the above findings be interpreted from a sociological perspective?

- q4.

- what recommendations could be provided for supporting a potential paradigm shift towards complexity each time it proves necessary?

2. Materials and Methods

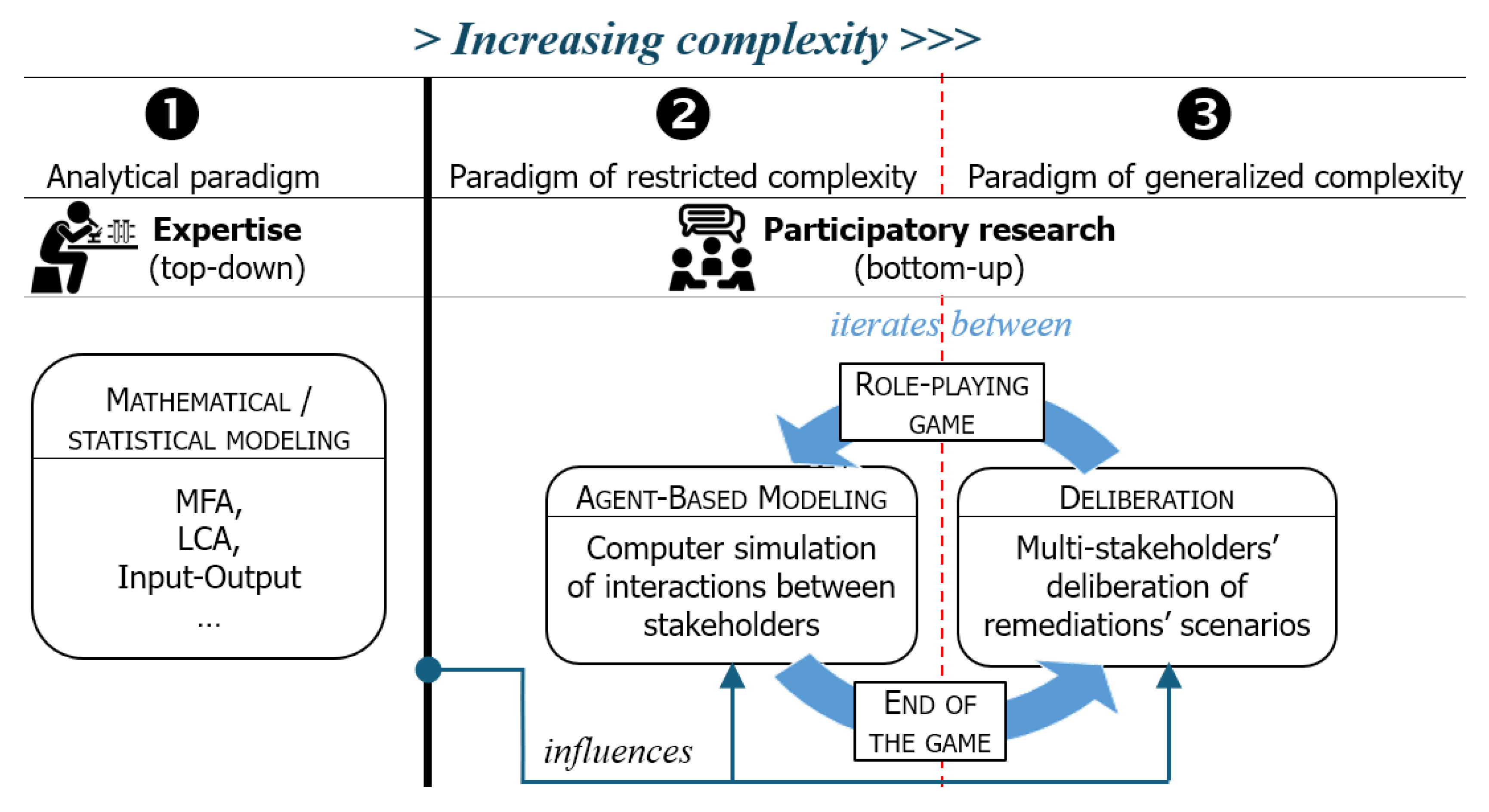

2.1. Theoretical Fields

2.2. Clarification of Some Theoretical Concepts

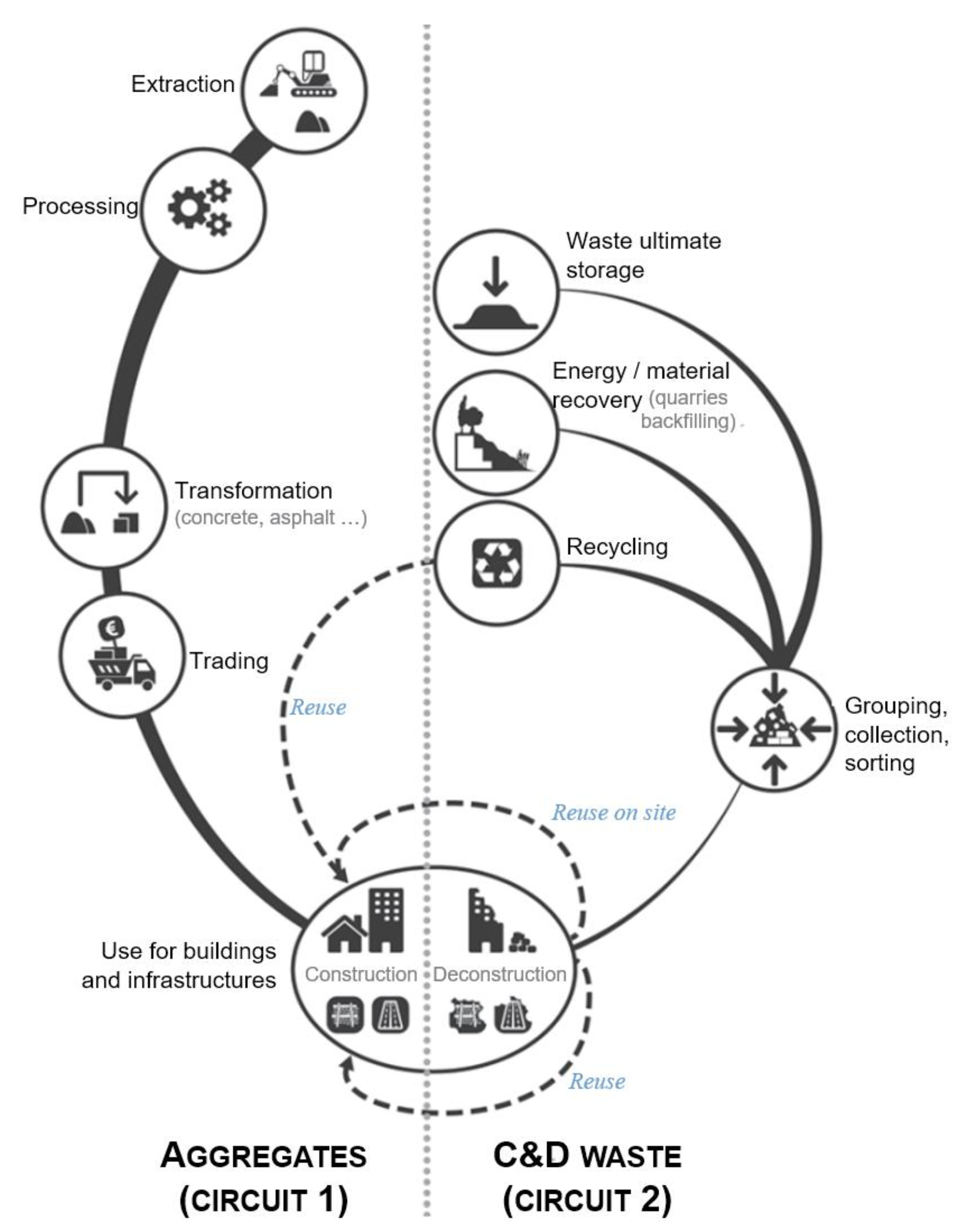

2.2.1. Circular Economy and Its Value Chain

- reduce the exploitation of alluvial deposits (to preserve the environment) in favor of massive rocks (having lower environmental stakes); also reduce waste disposal in landfills, in favor of recycling or recovery;

- reuse the excavated earth debris from deconstruction, for backfilling on the same site, or elsewhere;

- reuse inert concrete and asphalt waste from deconstruction, for road construction and/or for backfilling quarries at the end of their life;

- recycle waste to be incorporated into road construction.

2.2.2. Market

2.2.3. Agent, Agent-Based, and Emergence

2.2.4. Complexity Representation Paradigms

2.2.5. Habitus

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Preamble: Principle of Anonymization

- an alias will be assigned to each person;

- the terms ' he ', ' his ' and ' him ' shall be used to refer to a person or his/her actions, regardless of his/her actual gender;

- the names of the countries or regions of study will be anonymized, except for ‘France’ and the ‘BRGM’ where the main author of this article works;

- the reference of the models used to discuss with these stakeholders were withheld because we think this may open up possibilities of identifying some of them.

2.3.2. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

- questions/answers during project presentation meetings involving (at least) ABM&S;

- (what we call) discussions “in the corridor”, over coffee, with the stakeholders.

2.3.3. Summary on the Stakeholders We Met and the Study Areas

3. Results

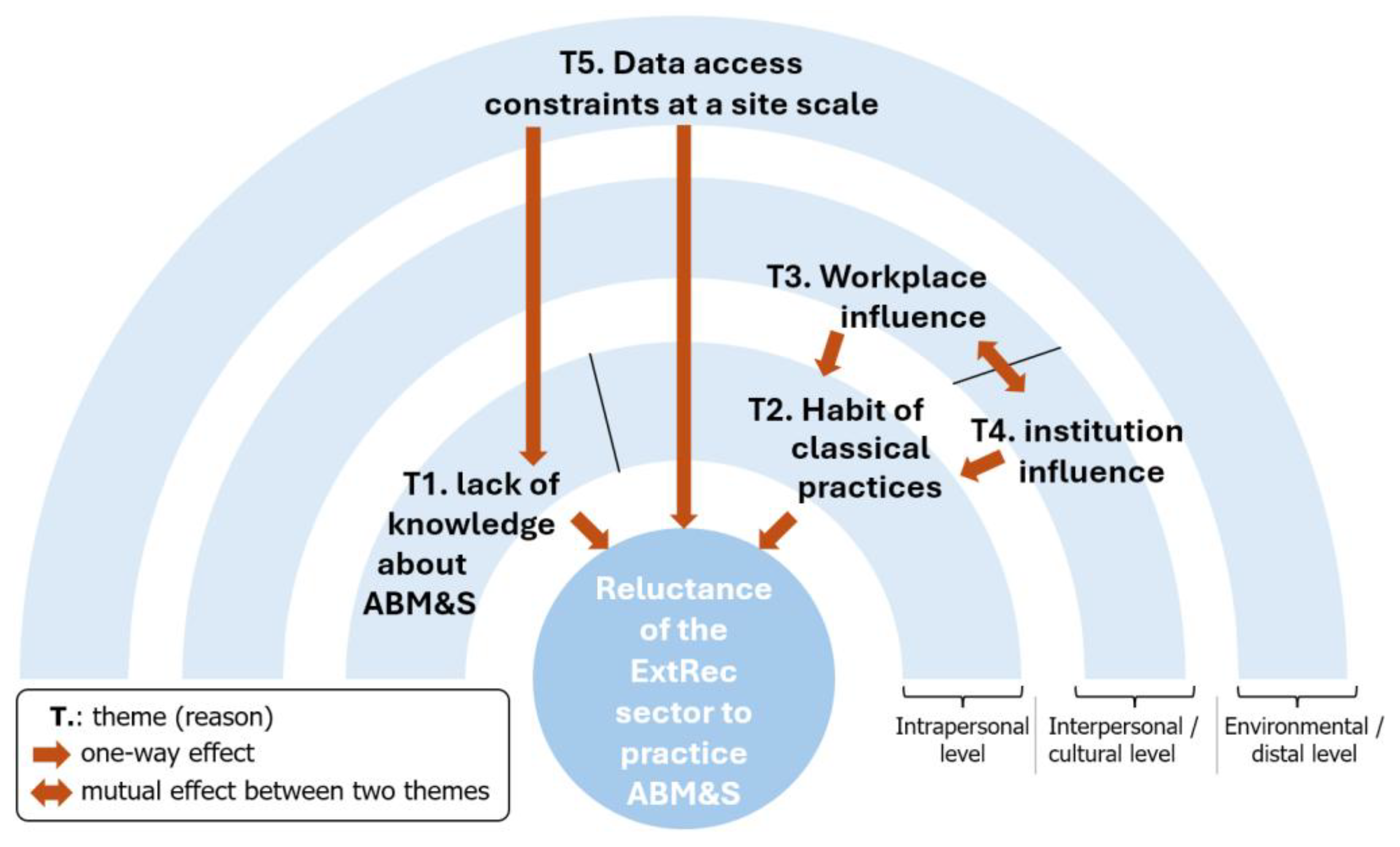

3.1. The Expressed Reasons for Reluctance

- the intrapersonal level, in which there are two themes: lack of knowledge about ABM&S and familiarity with classical market modelling and simulation practices;

- the interpersonal or cultural level, in which there are two themes: the influence of the workplace and the influence of institutions;

- the environmental or distal level, in which there is 1 theme: access to the data, often detailed, necessary for this type of modelling.

3.1.1. Reason 1: Lack of knowledge about ABM&S

3.1.2. Reason 2: Habit of Classical Practices

3.1.3. Reason 3: Influence of the Workplace

3.1.4. Reason 4: Influence of Institutions

3.1.5. Reason 5: Difficulty Accessing Data at the Micro Scale (Sites)

3.2. The Expressed Conditions for Appropriation

3.2.1. Condition 1: Coupling with Existing Approaches

3.2.2. Condition 2: Integrating Complete Circular Economy Circuits

3.2.3. Condition 3: Representing Multi-Scale Dynamics

3.2.4. Condition 4: Demonstrating Practical Value Through Case Studies

3.2.5. Condition 5: Ensuring Reliable Data at a Site Level

4. Discussions

4.1. Sociological Interpretation of the Results

4.2. Recommendations

4.3. Summary of Our Contributions

5. Concluding Remarks

5.1. Regarding Edgard Morin’s Culture of Complexity

5.2. Limits and Research Paths

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Abdelghaffar, E. , Hicham, E.K., Siham, B., Samira, E.F. & Youness, E.A. Perspectives of adolescents, parents, and teachers on barriers and facilitators of physical activity among school-age adolescents: a qualitative analysis. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrami, G. , Daré, W., Ducrot, R., Salliou, N. & Bommel, P. (2021). Participatory modelling. In R. Biggs, A. de Vos, R. Preiser, H. Clements, K. Maciejewski, M. Schlüter (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods for social-ecological systems. Abingdon: Routledge International Handbooks. ISBN 9781003021339. [CrossRef]

- ADEME (2012). Étude sur le prix d'élimination des déchets inertes du BTP. Etude. https://tinyurl.com/w-dech-adm.

- Ahmed, S.K. , Mohammed, R.A., Nashwan, A.J., Ibrahim, R.H., Abdalla, A.Q., M. Ameen, B.M. & Khdhir, R.M. (). Using thematic analysis in qualitative research. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2025, 6, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamasinoro, F. & Ahne, H. Prospective analysis of the world lithium market: contribution to the evaluation of supply shortage periods. International Business & Economics Research Journal 2013, 12, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamasinoro, F. & Monfort-Climent, D. Consideration of Complexity in the Management of Construction and Demolition Waste Flow in French Regions: An Agent-Based Computational Economics Approach. Modelling 2021, 2, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L. , Grimm, V., Sullivan, A., Turner II , B.L., Malleson, N., Heppenstall, A., Vincenot, C., Robinson, D., Ye, X., Liu, J., Lindkvist, É. & Tang, W. Challenges, tasks, and opportunities in modeling agent-based complex systems. Ecological Modelling 2021, 457, 109685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armatte, M. & Dahan, A. Models and modeling, 1950-2000: New practices, new implications. Revue d'histoire des sciences 2004, 57, 243–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimaki, A. & Koustourakis, G. Habitus: An attempt at a thorough analysis of a controversial concept in Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of practice. Social Sciences 2014, 3, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augiseau, V. & Barles, S. (). Studying construction materials flows and stock: A review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2017, 123, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreteau, O. , Abrami, G., Bonté, B., Bousquet, F. & Mathevet, R. (2021). Serious games. In R. Biggs, A. de Vos, R. Preiser, H. Clements, K. Maciejewski, M. Schlüter (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods for social-ecological systems (Ch. 15, pp. 176-88). Abingdon: Routledge International Handbooks. ISBN 9781003021339. [CrossRef]

- Barthe, Y. , De Blic, D., Heurtin, J.-P., Lagneau, É., Lemieux, C., Linhardt, D., Moreau de Bellaing, C., Rémy, C. & Trom, D. Pragmatic Sociology: A User’s Guide. Politix 2013, 103, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenfant, G. , Guezennec, A.-G., Bodénan, F., d’Hugues, P. & Cassard, D. (2013, September 18-20). Re-processing of mining waste: Combining environmental management and metal recovery? [Conference session]. 8th International Seminar on Mine Closure, Cornwall, England, pp. 571-82. [CrossRef]

- Beylot, A. , Hochar, A., Michel, P., Descat, M., Ménard, Y. & Villeneuve, J. Municipal Solid Waste Incineration in France: An Overview of Air Pollution Control Techniques, Emissions, and Energy Efficiency. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2018, 22, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonabeau, E. , Theraulaz, G. & Dorigo, M. (1999). Swarm Intelligence: From Natural to Artificial Systems. USA: OUP. 320 p. ISBN-13 : 978-0-19513-159-8.

- Bonneuil, C. & Joly, P.-B. (2013). Sciences, techniques et société. La Découverte. ISBN 9782707150974.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. 255 p. ISBN-13: 978-0521291644.

- Bradley, R. (2018). 16 Examples of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Your Everyday Life. https://tinyurl.com/w-16ex-AI.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawoy, M. On Desmond: The Limits of Spontaneous Sociology. Theory and Society 2017, 46, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, S. , Christensen, T.H. & Astrup, T.F. Life cycle assessment of construction and demolition waste management. Waste Management 2015, 44, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne, P. & Christin, O. (2012). « Habitus ». Pierre Bourdieu. Presses universitaires de Lyon, 57-91. [CrossRef]

- Charmillot, M. (2021). Définir une posture de recherche, entre constructivisme et positivisme. In F. Piron & É. Arsenault (Eds.), Guide décolonisé et pluriversel de formation à la recherche en sciences sociales et humaines. Esbc. https://tinyurl.com/w-post-char.

- Collins, A.J. , Koehler, M. & Lynch, C.J. Methods That Support the Validation of Agent-Based Models: An Overview and Discussion. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courdier, R. , Guerrin, F., Andriamasinoro, F. & Paillat, J.-M. Agent-based simulation of complex systems: application to collective management of animal wastes. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 2002, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, A. (2009). Épistémologie de la modélisation, le cas des modèles de climat. In D. Hervé & F. Laloë (Eds.), Modélisation de l'environnement : entre natures et sociétés (Ch. 10, pp. 193-208). Éditions Quæ. [CrossRef]

- Daré, W. , Venot, J., Le Page, C. & Aduna, A. Problemshed or Watershed? Participatory Modeling towards IWRM in North Ghana. Water 2018, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermine-Brullot, S. & Torre, A. (). Dossier « L’économie circulaire : modes de gouvernance et développement territorial ». Nature, Sciences et Société 2020, 28, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z. , Liu, R., Wang, Y., WY. Tam, V. & Ma, M. An agent-based model approach for urban demolition waste quantification and a management framework for stakeholders. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 285, 124897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionnet, M. , Imache, A., Leteurtre, E., Rougier, J.-E. & Dolinska, A. (2017). Guide de concertation territoriale et de facilitation. Lisode. 64 p. [CrossRef]

- Douguet, J.M. , Morlat, C., Lanceleur, P. & Andriamasinoro, F. Subjective evaluation of aggregate supply scenarios in the Ile-de-France region with a view to a circular economy: the ANR AGREGA research project. International Journal of Sustainable Development 2019, 22, 123–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drogoul, A. & Ferber, J. (1994). Multi-agent simulation as a tool for modeling societies: Application to social differentiation in ant colonies. In C. Castelfranchi & E. Werner (Eds.), Artificial Social Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 830. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Etienne, M. , Du Toit, D.R. & Pollard, S. ARDI: a Co-construction Method for Participatory Modeling in Natural Resources Management. Ecology and Society 2011, 16, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, J.D. & Foley, D. The economy needs agent-based modelling. Nature 2009, 460, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, J. The simplicity principle in perception and cognition. Cognitive Science 2016, 7, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, J. (1999). Multi-Agent Systems: An Introduction to Distributed Artificial Intelligence. Addison Wesley. 528 p. ISBN-10 0201360489.

- Fermet-Quinet, N. (2024). Intégrer les activités minières et leurs impacts dans un outil d’aide à la discussion pour la planification territoriale – cas de l’or en Guyane. PhD Thesis in Geosciences. University of Lorraine (France) - GeoResources Laboratory. https://theses.fr/s365356.

- Frame, B. & O’Connor, M. Integrating valuation and deliberation: the purposes of sustainability assessment. Environmental Science & Policy 2011, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, J. (2004). The Emergence of Complexity. Kassel: Kassel university press. 200 p. ISBN 978-3-89958-069-3.

- Halpin, B. Simulation in Sociology. American Behavioral Scientist 1999, 42, 1488–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, L. Agent-based modelling: the next 15 years. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 2010, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatik, C. , Medmoun, M., Courdier, R. & Soulié, J.-C. (2020, October 7-9). PoVaBiA: A multi-agent decision-making support tool for organic waste management [Conference session]. 18th International Conference on Practical Applications of Agents and Multi-Agent Systems (PAAMS), L'Aquila, Italie, pp. 421-25. ISBN 978-3-030-49777-4. [CrossRef]

- Knorr-Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Harvard University Press. 352 p. ISBN-13: 978-0674258945.

- Latour, B. When things strike back: a possible contribution of ‘science studies’ to the social sciences. The British Journal of Sociology 2000, 51, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Page, C. , Abrami, G., Barreteau, O., Bécu, N., Bommel, P., Botta, A., Dray, A., Monteil, C. & Souchère, V. (2014). Models for sharing representations. In M. Etienne, (Ed.) Companion Modelling: A Participatory Approach Supporting Sustainable (Ch. 3, pp. 69-101). Springer, Dordrecht. Online ISBN 978-94-017-8557-0. [CrossRef]

- Lebot, B. & Andriamasinoro, F. (2025). Evaluating the Role of Knowledge Co-Production in Addressing Post-Mining Risks. In D. Maddaloni & O. Gkounta (Eds.), Abstract Book - 19th Annual International Conference on Sociology (Ch. 25, pp. 52-53). Athens Greece. ISBN 978-960-598-673-5. https://www.atiner.gr/abstracts/2025ABST-SOC.pdf.

- Li Vigni, F. (2022). Histoire et sociologie des sciences de la complexité. Éditions Matériologiques ed. 194 p. https://tinyurl.com/w-vign-pf.

- Martin, G. , Rentsch, L., Höck, M. & Bertau, M. Lithium market research – global supply, future demand and price development. Energy Storage Materials 2017, 6, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvasti, A.B. (2004). Qualitative Research in Sociology. SAGE Publications. 160 p. ISBN 0 7619 4860 0.

- Merlin, J. , Gunzburger, Y. & Laurent, B. (2018, August 18). "Mining renewal" in metropolitan France? The controversial definition of a "responsible mine" model [Conference session]. 4S Conference, Sydney.

- Moriguchi, Y. & Hashimoto, S. (2016). Material Flow Analysis and Waste Management. In R. Clift & A. Druckman (Eds.), Taking Stock of Industrial Ecology. Springer International Publishing, Cham. ISBN 978-3-319-20571-7. [CrossRef]

- Morin, É. (2008). On Complexity. Hampton Press. 127 p. ISBN-13: 978-1572738010.

- Moyaux, T. , Chaib-Draa, B. & D’Amours, S. (2006). Supply Chain Management and Multiagent Systems: An Overview. In B. Chaib-draa & J.P. Müller (Eds.), Supply Chain Management and Multiagent Systems. Springer-Verlag. ISBN-10: 3-540-33875-6. [CrossRef]

- Müller, B. , Bohn, F., Dreßler, G., Groeneveld, J., Klassert, C., Martin, R., Schlüter, M., Schulze, J., Weise, H. & Schwarz, N. Describing human decisions in agent-based models – ODD + D, an extension of the ODD protocol. Environmental Modelling & Software 2013, 48, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCERT (2007). The market as a social institution. In Indian Society: Textbook in Sociology for Class XII. ISBN 81-7450-652-7. https://tinyurl.com/w-indi-mark.

- O’Connor, M.P. & Douguet, J.-M. Working deliberat(iv)ely with(in) wicked problems: The existential, epistemological and ethical nexus of imperfect knowledge. Futures 2024, 163, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottolini, L. (2020). Travailler avec le tiers secteur : études de cas des politiques d’ouverture à la société dans les instituts d’expertise et de leurs effets en France de 1990 à 2020. Thèse de Doctorat en Sociologie. Université Gustave Eiffel - Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Sciences Innovations Sociétés. https://theses.fr/2020PESC2020.

- PanoramaIdF (2017). Granulats en Île-de-France : Panorama régional. Collectif DRIEE - IAU - UNICEM., ISBN 978 27371 2018 3 https://tinyurl.com/w-idf-pano.

- Peng, Z. , Lu, W. & Webster, C. Understanding the effects of a construction waste cap-and-trade scheme: An agent-based modeling study in Hong Kong. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 375, 134135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotton, A. , de Garine-Wichatitsky, M., Valls-Fox, H. & Le Page, C. My cattle and your park: Codesigning a role-playing game with rural communities to promote multistakeholder dialogue at the edge of protected areas. Ecology and Society 2017, 22, art35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, S. & Sturgeon, T. Explaining governance in global value chains: A modular theory-building effort. Review of International Political Economy 2014, 21, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. , Siau, K.L. & Nah, F.F. Societal impacts of artificial intelligence: Ethical, legal, and governance issues. Societal Impacts 2024, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualited(2024). Modèle FR : 20243036-001 - Planche de jeu. inpi. https://tinyurl.com/w-qtd-24.

- Rand, W. & Rust, R.T. Agent-Based Modeling in Marketing: Guidelines for Rigor. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2011, 28, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémy, J. (2020). Introduction. Transactions sociales et complexité. In J. Rémy, (Ed.) La transaction sociale : Un outil pour dénouer la complexité de la vie en société. [CrossRef]

- Riddle, M. , Macal, C.M., Conzelmann, G., Combs, T.E., Bauer, D. & Fields, F. Global critical materials markets: An agent-based modeling approach. Resources Policy 2015, 45, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, M.E. , Tatara, E., Olson, C., Smith, B.J., Irion, A.B., Harker, B., Pineault, D., Alonso, E. & Graziano, D.J. (). Agent-based modeling of supply disruptions in the global rare earths market. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2021, 164, 105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Chavez, M.-L. (2010). Anticipation of the access to the aggregate resource by breaking present schemes in the long term. Thesis (PhD). Paris: MINES ParisTech, HAL Id: pastel-00563707 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/pastel-00563707.

- Rossignol, J.-Y. (2018). Complexité : Fondamentaux à l'usage des étudiants et des professionnels. 1st ed. EDP Sciences - Collection : PROfil. 262 p. EAN13: 9782759821945.

- Ryter, J. , Bhuwalka, K., O'Rourke, M., Montanelli, L., Cohen-Tanugi, D., Roth, R. & Olivetti, E. Understanding key mineral supply chain dynamics using economics-informed material flow analysis and Bayesian optimization. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2024, 28, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, J. , Tessier, B., Thenevin, I., Deneuve, C., Mallens, C. & Goethals, L. (). Le projet AGREGA : vers un outil pédagogique et ludique pour simuler le marché des granulats en région Île-de-France. Annales des Mines - Responsabilité et environnement, Eska 2019, 96, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J. , Ditta, A., Haney, B., Haarsma, L. & Carbajales-Dale, M. Resource Criticality in Modern Economies: Agent-Based Model Demonstrates Vulnerabilities from Technological Interdependence. Biophysical economics and resource quality 2017, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOeS (2022). Waste Generation and Recycling: Extract from France's 2021 Environmental Performance Review. Fact sheet. French Environment Ministerial Statistical Department, French service of observation and statistics. https://tinyurl.com/w-cgdd-waste.

- Soto-Vázquez, R. Life-cycle assessment in mining and mineral processing: A bibliometric overview. Green and Smart Mining Engineering 2025, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulié, J.-C. & Wassenaar, T. (2017, December 3-8). Modelling the integrated management of organic waste at a territory scale [Conference session]. 22nd International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM), Tasmania, Australia, p. 75. ISBN 978-0-9872143-6-2. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/588064/.

- Squazzoni, F. The impact of agent-based models in the social sciences after 15 years of incursions. History of Economic Ideas 2010, 18, 197–233. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, J. & King, B. Using Informal Conversations in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2022, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillandier, P. , Grignard, A., Marilleau, N., Philippon, D., Huynh, Q.-N., Gaudou, B. & Drogoul, A. Participatory Modeling and Simulation with the GAMA Platform. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazi, N. , Idir, R. & Ben Fraj, A. Sustainable reverse logistic of construction and demolition wastes in French regions: Towards sustainable practices. Procedia CIRP 2020, 90, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X. , Peng, F., Wei, G., Xiao, C., Ma, Q., Hu, Z. & Yaobin, L. Agent-based modeling in solid waste management: Advantages, progress, challenges and prospects. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2025, 110, 107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, D.S. , Onggo, B.S. & Eldridge, S. Applications of agent-based modelling and simulation in the agri-food supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research 2018, 269, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Asselt Marjolein, B.A. & Rijkens-Klomp, N. A look in the mirror: reflection on participation in Integrated Assessment from a methodological perspective. Global Environmental Change 2002, 12, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A.M. (1987). Science and Its Limits. In C. Whipple, (Ed.) De Minimis Risk. Springer, Boston. ISBN 978-1-4684-5295-2. [CrossRef]

- Wynne, B. Misunderstood misunderstanding: social identities and public uptake of science. Public Understanding of Science 1992, 1, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. , Yellishetty, M., Muñoz, M.A. & Northey, S.A. Toward a dynamic evaluation of mineral criticality: Introducing the framework of criticality systems. Industrial Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, P. Ideal Types in Max Weber's Sociology of Religion: Some Theoretical Inspirations for a Study of the Religious Field. Polish Sociological Review 2010, 171, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

| Alias | Description | Intervention in market simulation models | Method of data collection by the researchers | Model scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FrGS_Ec1 | Metals Market Economist | Users | Meeting to present an ABM&S model for simulating the lithium market | International |

| FrGS_Ec2 | Researcher and modeler of the metals market using econometric practices | Producers/Users | Meeting to present an ABM&S model for simulating the lithium market | International |

| FrGS_Innov | Member of the BRGM Innovation Team | n / a | Corridor discussion on the introduction of new participatory approach tools at the French National Geological Survey (BRGM) | n/a |

| Min_Mod | Aggregates market modeler using mathematical practices | Producers / users | Observation over time (over different projects) of modelling and simulation practices in the aggregates market in France | National (France) |

| C1GS_Flw | Member of the team of flow analysts (MFA approach, etc.) of mineral resources of the geological service of the foreign country C1 | Users | Corridor discussion on the idea of applying ABM&S to the geological survey of country C1 (non-France) | National (country C1) |

| Fr_Synp | Union representing material producers (France) | Users | Meeting to present an aggregates market model based on mathematical practices (dynamic system) | National (France) |

| Reg1_Synm | Union representing construction in region 1 (France) | Users, data providers | Meeting to present an aggregates market model based on mathematical practices (optimization) | Region 1 (France) |

| Reg1_GOrd | Data manager of the regional waste observatory in region 1 (France) | Data provider | Corridor discussion on providing data to develop an ABM&S of demolition waste streams on the secondary aggregate circuit in Region 1 | Region 1 (France) |

| Reg2_Synm | Union representing construction in region 2 (France) | Users, data providers | Observation of use of aggregates market model based on mathematical practices (optimization) | Region 2 (France) |

| Reg2_GOrd | Data manager of the regional waste observatory in region 2 (France) | Data provider | Corridor discussion on providing data to develop an ABM&S of demolition waste streams on the secondary aggregate circuit in Region 2 | Region 2 (France) |

| Reg2_Actr | Stakeholders involved in the management of deconstruction waste in region 2: the Center for Urban Planning Studies, regional authorities, and the regional construction unit | Users | Meeting to present an ABM&S model of demolition waste flows on the secondary aggregate circuit in region 2 | Region 2 (France) |

| Ideal type of social reluctance towards ABM&S | Reasons for action | Example of actors adopting this attitude (see Table 1) |

|---|---|---|

| Reluctance to ABM&S by traditional action | Tradition, entrenching of classical modelling habits (MFA, LCA, etc.) | C1GS_Flw |

| Reluctance to ABM&S through affective or affective action | Influence (pressure?) from institutions or the workplace for the priority implementation of specific projects with specific methods and which do not leave time to think about / to test new modelling practices | FrGS_Ec1, C1GS_Flw |

| Reluctance to ABM&S through value rationality | The value of defending certain modelling practices at all costs throughout projects, leaving no room for new practices | FrGS_Ec2, Min_Mod |

| Reluctance to ABM&S by rationality in purpose | It is based on the classical paradigm (paradigm ➊) but does not exclude an opening to paradigm ➋ depending on the purpose it seeks to achieve. | Fr_Synp, Reg2_Actr |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).