Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

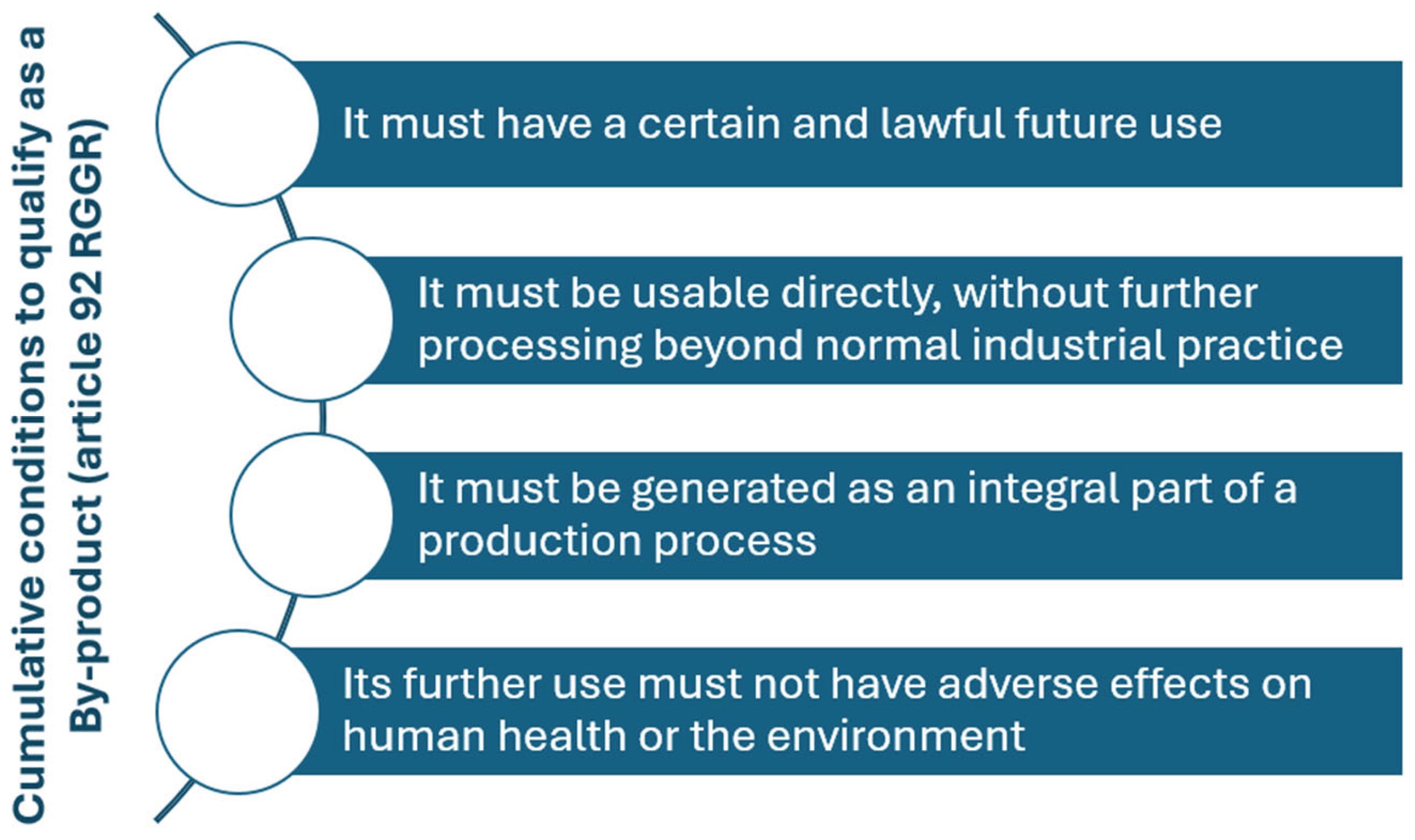

1.1. Ceramic Sector Contextualization - Waste Declassification Directive

1.2. Considerations on the Proposed Approach

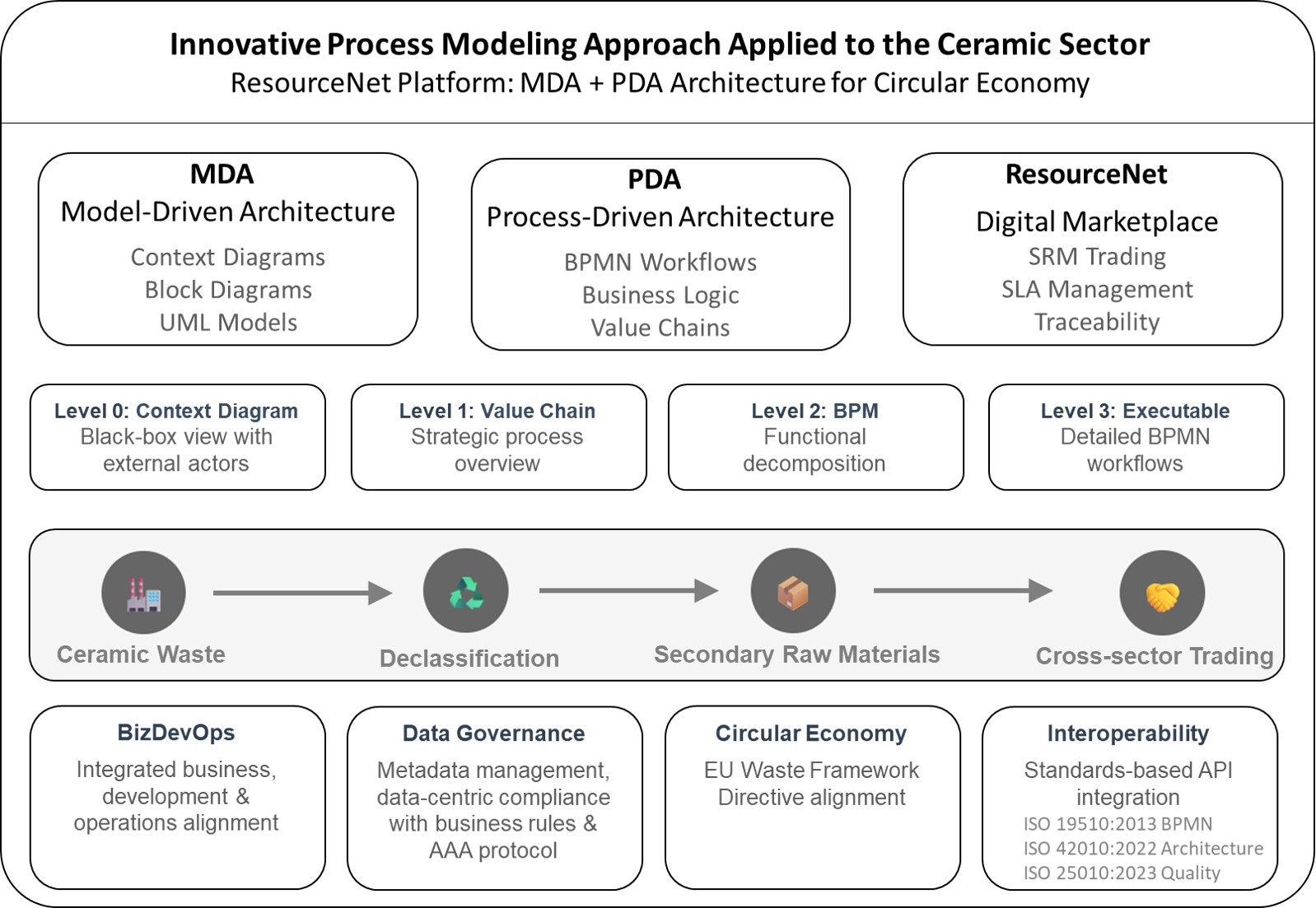

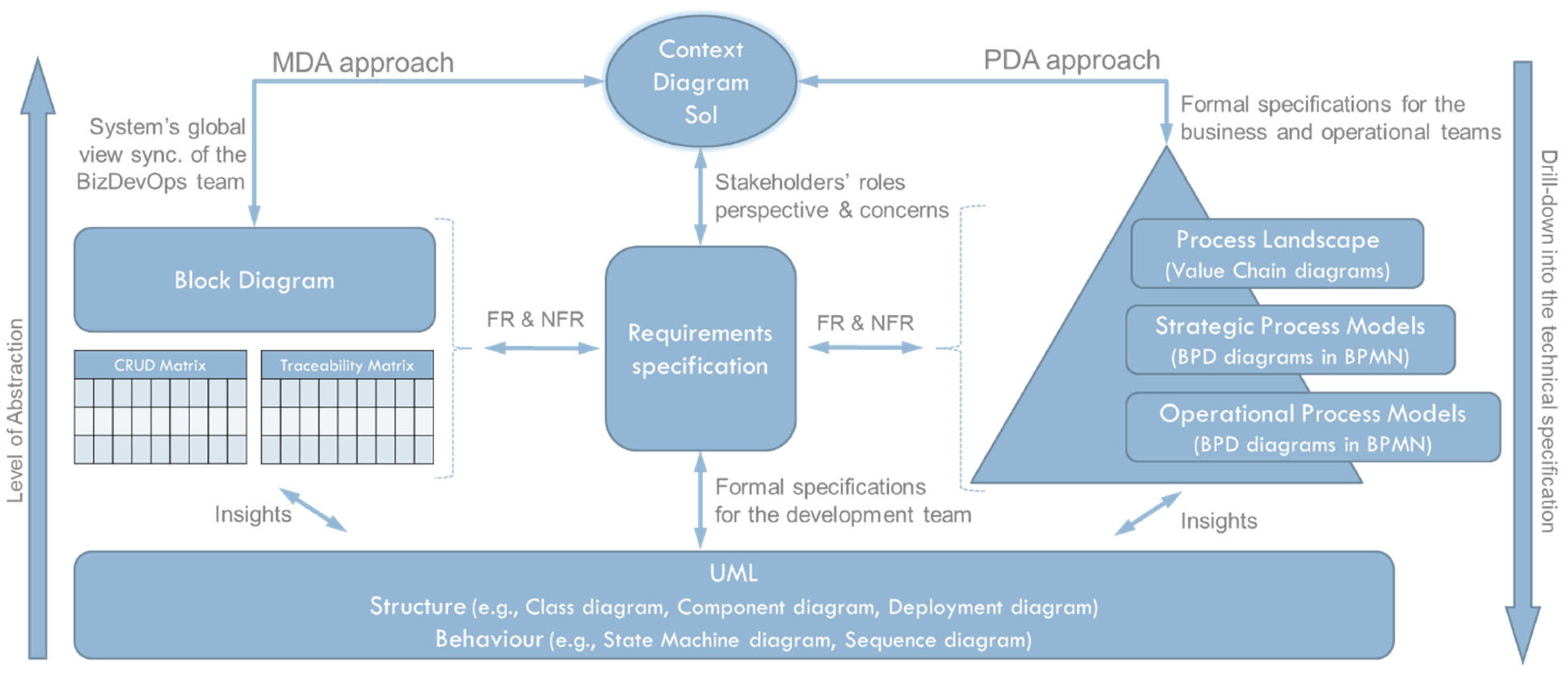

2. The Modeling Approach within the ResourceNet Case Study

2.1. Model Driven Architecture

2.2. Process-Driven Architecture Lifecycle – Technical Overview

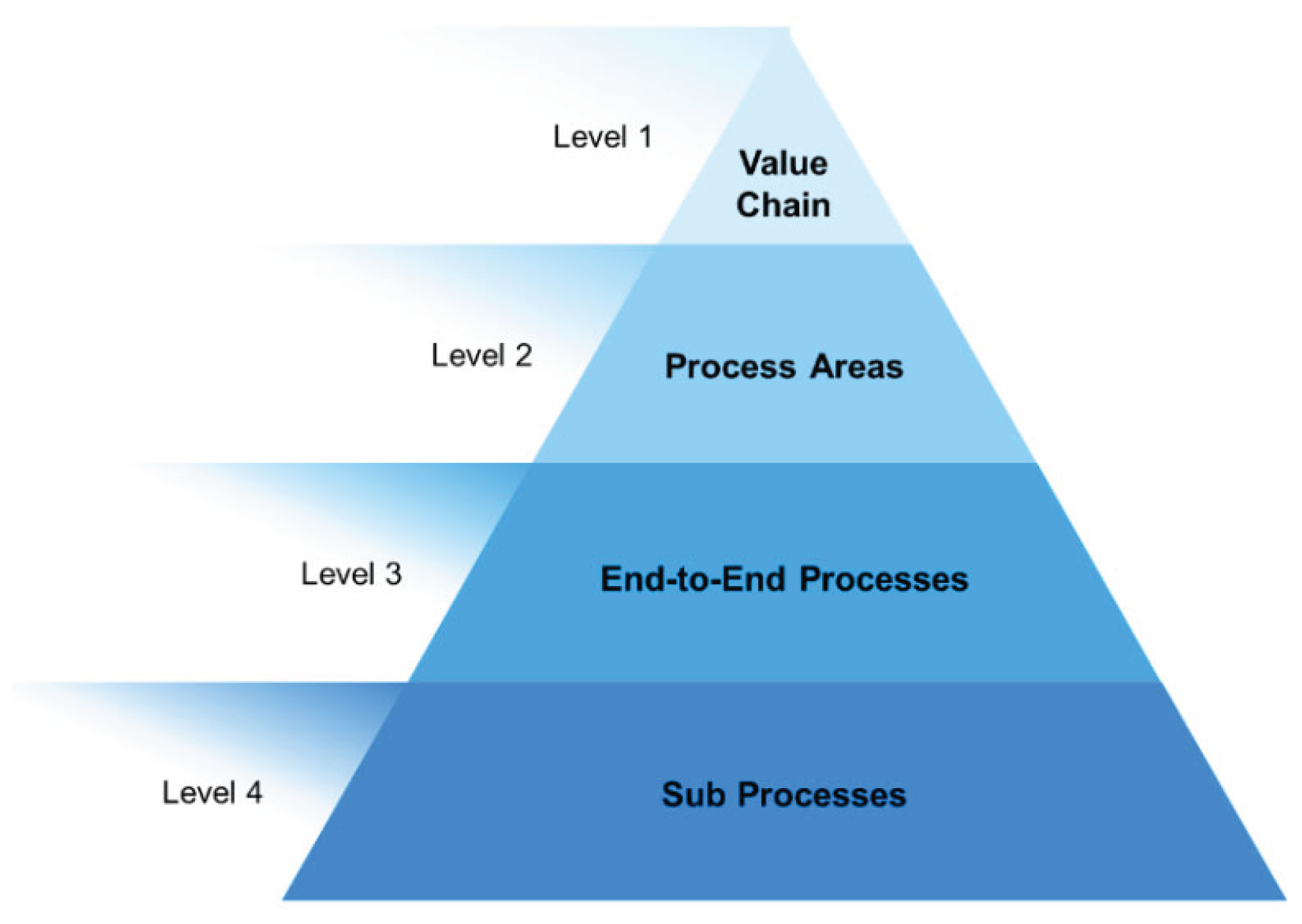

- Level 0 – Context Diagram (Black-Box View): This level defines the SoI as a Black Box, focusing on its external interactions with stakeholders, systems, and roles. It outlines environmental boundaries, dependencies, and high-level responsibilities. Two interface types are distinguished: carbon processors (GUIs for human interaction) and silica processors (APIs for system integration). GUIs introduce complexity due to human unpredictability, usability, and security issues, while APIs are more deterministic and easier to validate. This diagram helps scope the architecture and define key communication channels, serving as a foundation for requirements engineering by clarifying the roles of actors and the expected interactions between the system and its users.

- Level 1 – Process Landscape Diagram (Strategic Overview): This level provides a strategic view of the organization's value chain, mapping primary and supporting business areas through high-level process groups, often aligned with or related to the project scope. These are abstracted from implementation details but establish ownership, information flow, and potential integration points. It helps correlate business domains to software modules (e.g., GUIs in the presentation layer and business rules at the application layer) and distinguishes between human and machine interaction needs. The diagram complements the block diagram by positioning business processes within the architecture, promoting a shared understanding of the system's high-level logic and strategic business alignment.

- Level 2 – Business Process Modeling (Functional Decomposition): This level describes internal workflows for selected processes, documenting the sequences of activities, decisions, and inputs and outputs. The outcome is a functional decomposition of the selected processes, showing dependencies, responsibilities, and interactions between roles, organizational units, or systems. This level provides the functional scope and behavioural context for defining technical requirements and refining user stories. Artefacts such as business process diagrams or event-driven process chains may be used to complement the characterization of the SoI at this stage. It bridges abstract process overviews with tangible behavioral patterns, enabling precise analysis and stakeholder validation.

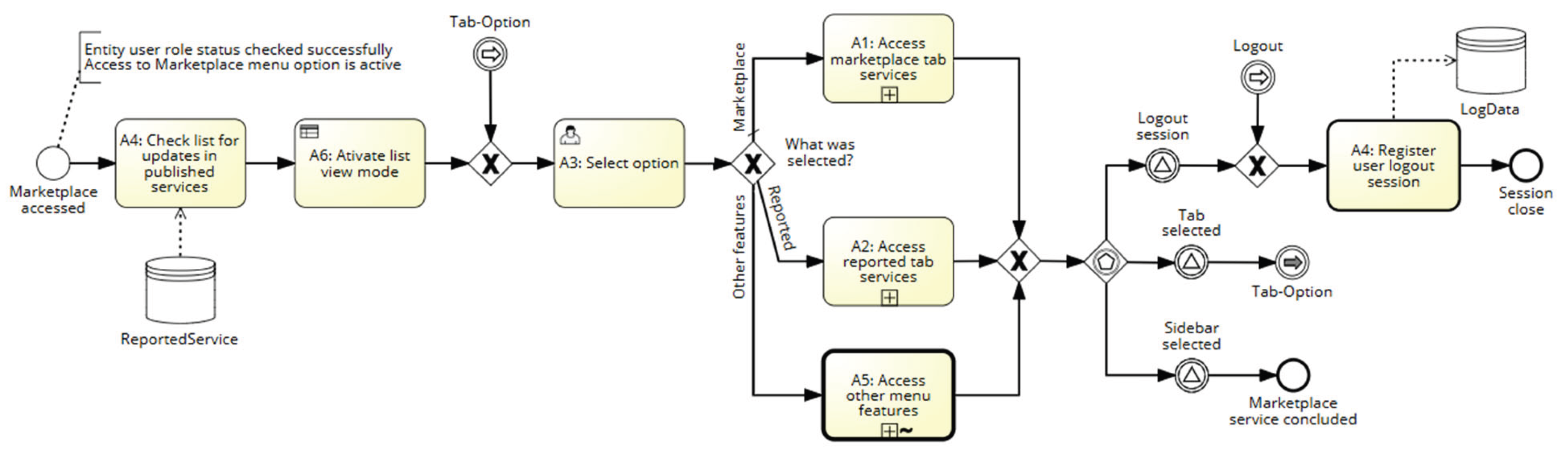

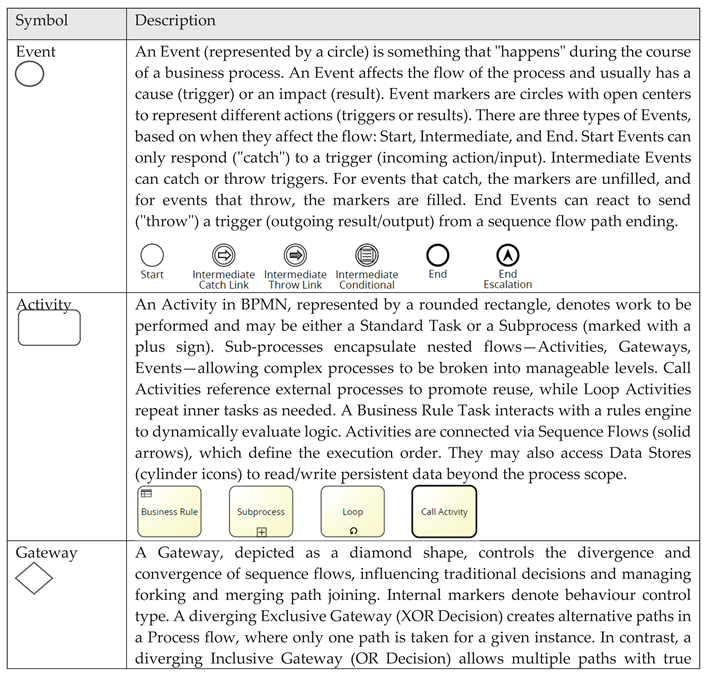

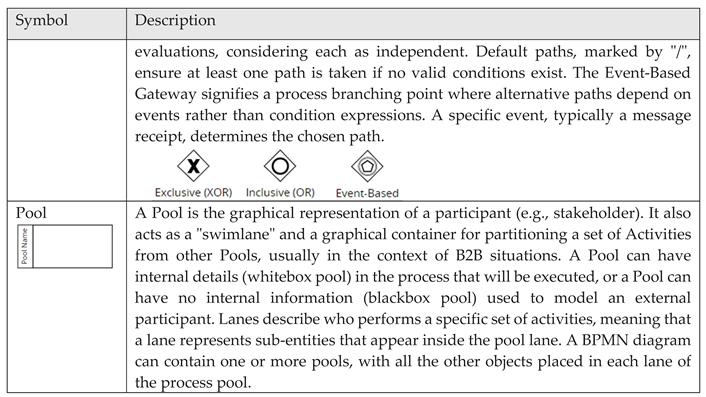

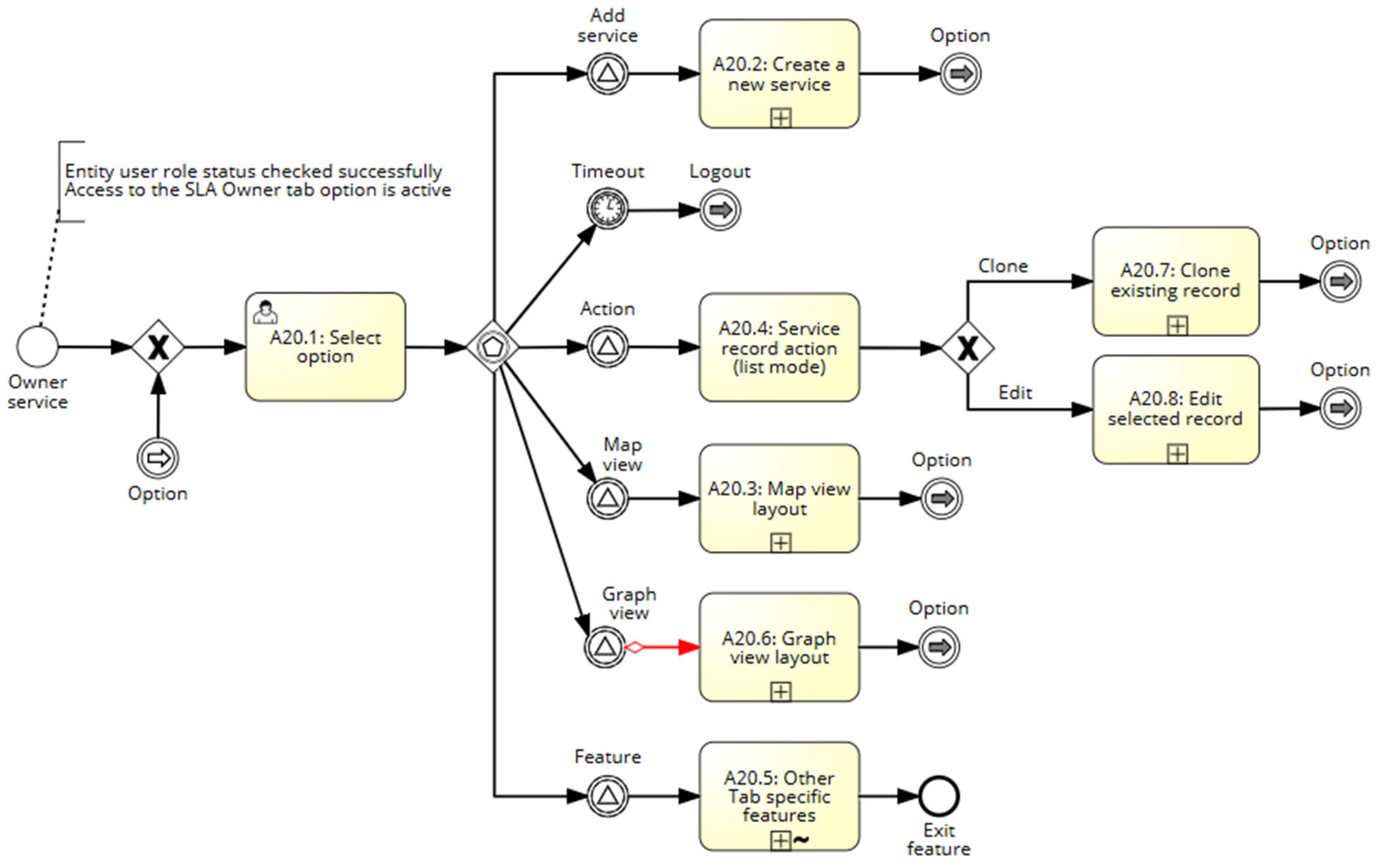

- Level 3 – Executable Process Models (Detailed Specification): This level formalizes business logic into executable workflows using BPMN constructs (tasks, gateways, events, pools/lanes). It specifies how processes are orchestrated across manual and automated actions, aligning system behavior with business intent. Data objects are mapped to technical elements (e.g., UML class diagrams, state machines), and interfaces are detailed through wireframes (for GUIs) or schemas (for APIs). Business rules are externalized using Decision Model and Notation (DMN) or expressed in Decision Management Languages (DML) to promote clarity and modularity. Separating rules from process logic improves traceability, supports regulatory compliance, and simplifies updates. This level provides a detailed, executable model of workflows, roles, and interactions, serving as both a technical blueprint for developers and a collaborative reference for analysts and operations teams. It ensures that the implemented system remains aligned with business logic, operational goals, and evolving policy or compliance requirements.

- Level 4 – Sub-Processes (Modular Detail): This level introduces sub-processes, offering a deeper level of granularity for tasks that are too complex to be modelled inline at Level 3. This modularity enables the isolation of complex or reusable logic into modular sub-processes using BPMN's call activities or embedded constructs. These units handle domain-specific, repetitive, or cross-cutting concerns (e.g., authentication, data validation) and support reusability and maintainability. They align with backend architecture, often mapping to microservices or bounded contexts. This level refines the system's internal behavior by integrating sub-process logic into the broader workflow, facilitating consistent enforcement of rules and policies. When linked to block diagrams, Level 4 provides backend behavioral depth and supports modular evolution of large-scale, compliant, and maintainable systems.

2.3. Data Governance Framework Within the Process-Driven Architecture Lifecycle

3. Data Governance Framework – Case Study Example

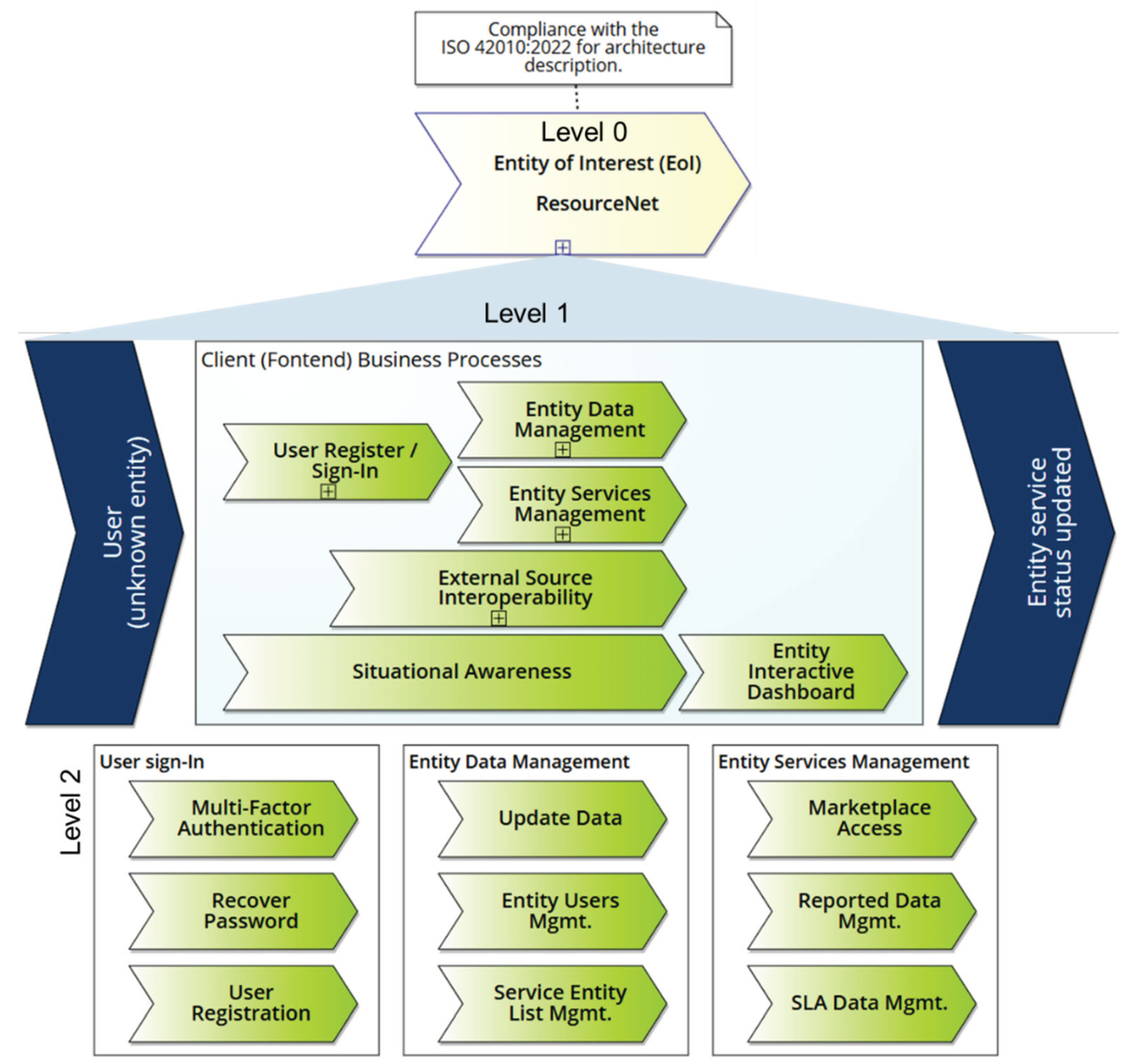

3.1. System of Interest – Context Diagram

3.2. Operational Process – Data Governance

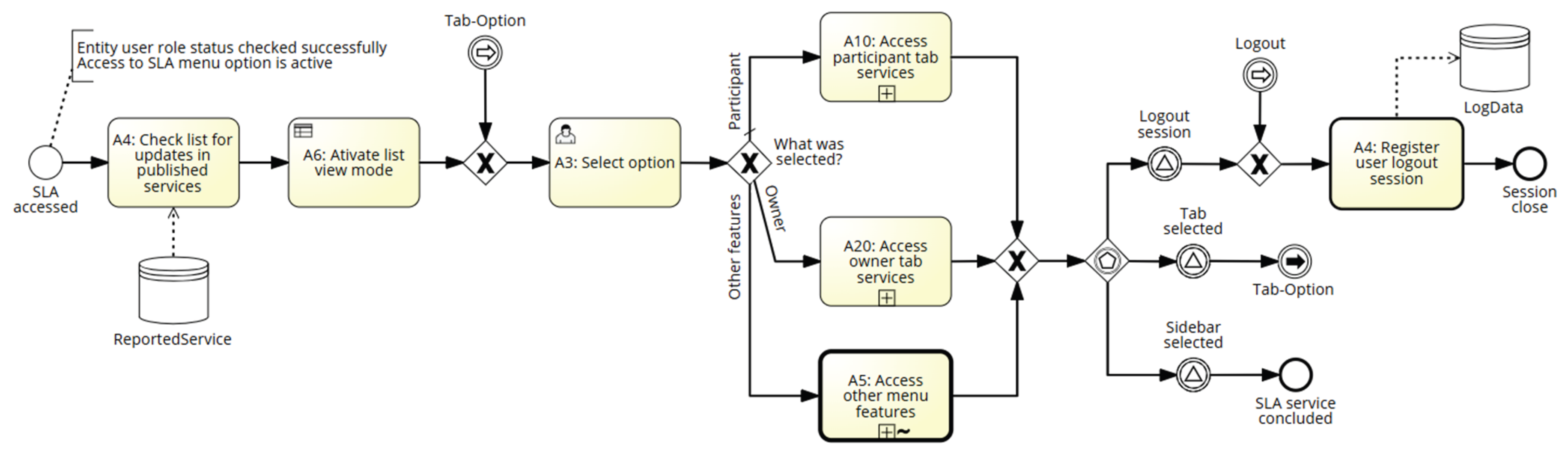

- Administrator User (A-User): By default, the user who registers an entity is assigned the A-User profile, acting as the administrator of that entity's record. Once the registration request is approved, the entity record becomes active, granting the A-User full CRUD rights and access to permission management services. A-Users can assign additional users to their entity with A-User, M-User, or S-User profiles. An A-User may be associated with multiple entities.

- Master User (M-User): The M-User has permissions similar to the A-User, including CRUD access and user management within the entity (or across grouped entities) to which they belong. However, M-Users cannot modify A-User accounts or access platform-wide settings. M-Users may also be associated with multiple entities and are responsible for managing users with M-User and S-User profiles.

- Standard User (S-User): This profile grants read access to entity-level data and allows CRUD operations over data elements specific to the entity to which they are linked. S-Users can add or update services and manage notifications triggered by workflows, especially in cases where the user is designated as a point of contact for SLA participation. The role is essential for operational data entry and service maintenance.

- Owner User (O-User): This is a supervisory role assigned to the governing body responsible for the overall integrity and validation of data within the ResourceNet platform, such as APICER. The O-User has read-only access to platform data but can approve or reject entity registration requests and change the status of entity records. The O-User monitors data quality, oversees behavioral compliance, and can suspend user or entity access upon detecting irregularities or suspicious activity.

- Regulator User (R-User): Typically representing regulatory authorities in the ceramics sector, the R-User profile allows read-only access to all platform data, supporting compliance and regulatory oversight.

|

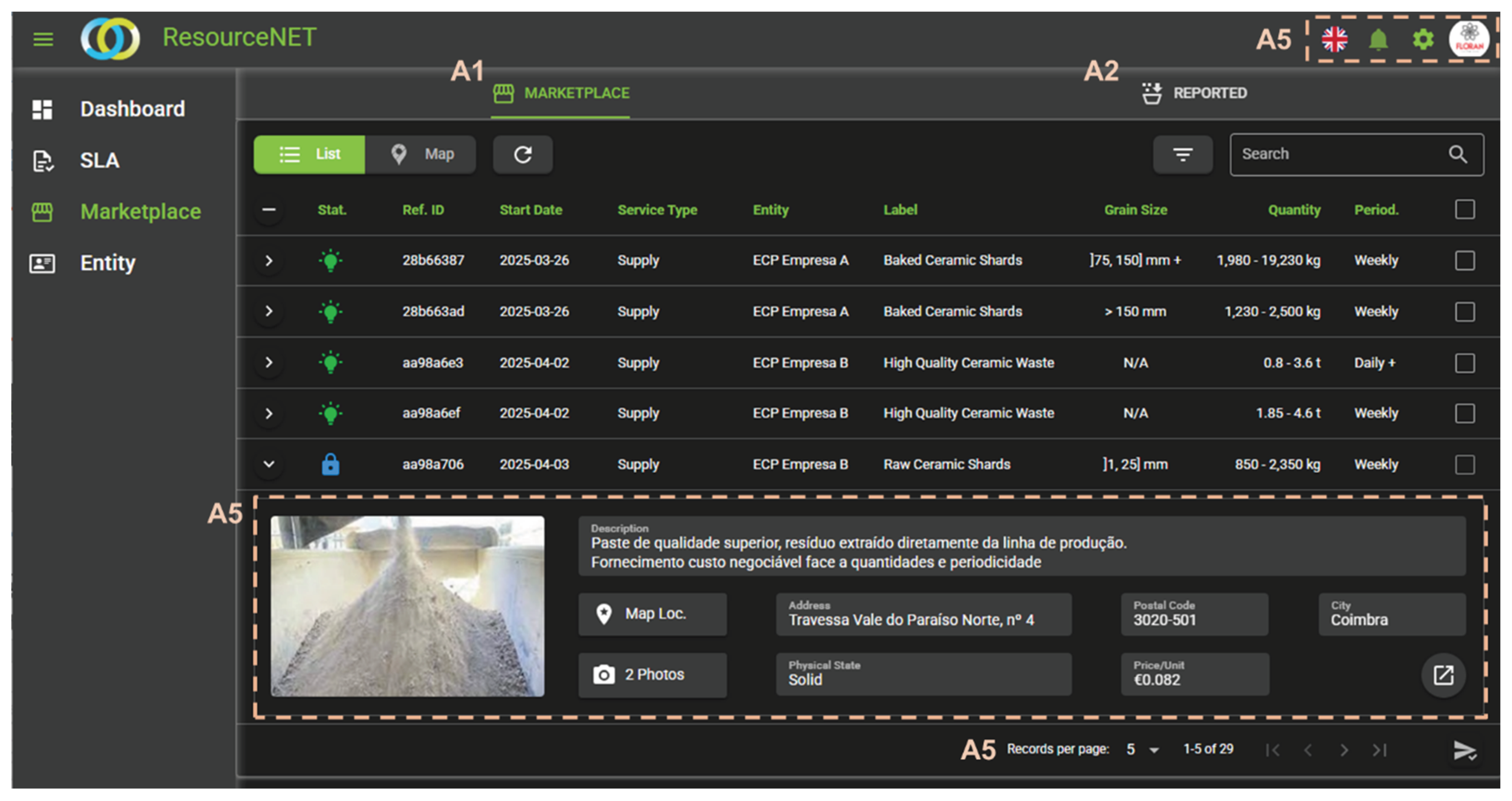

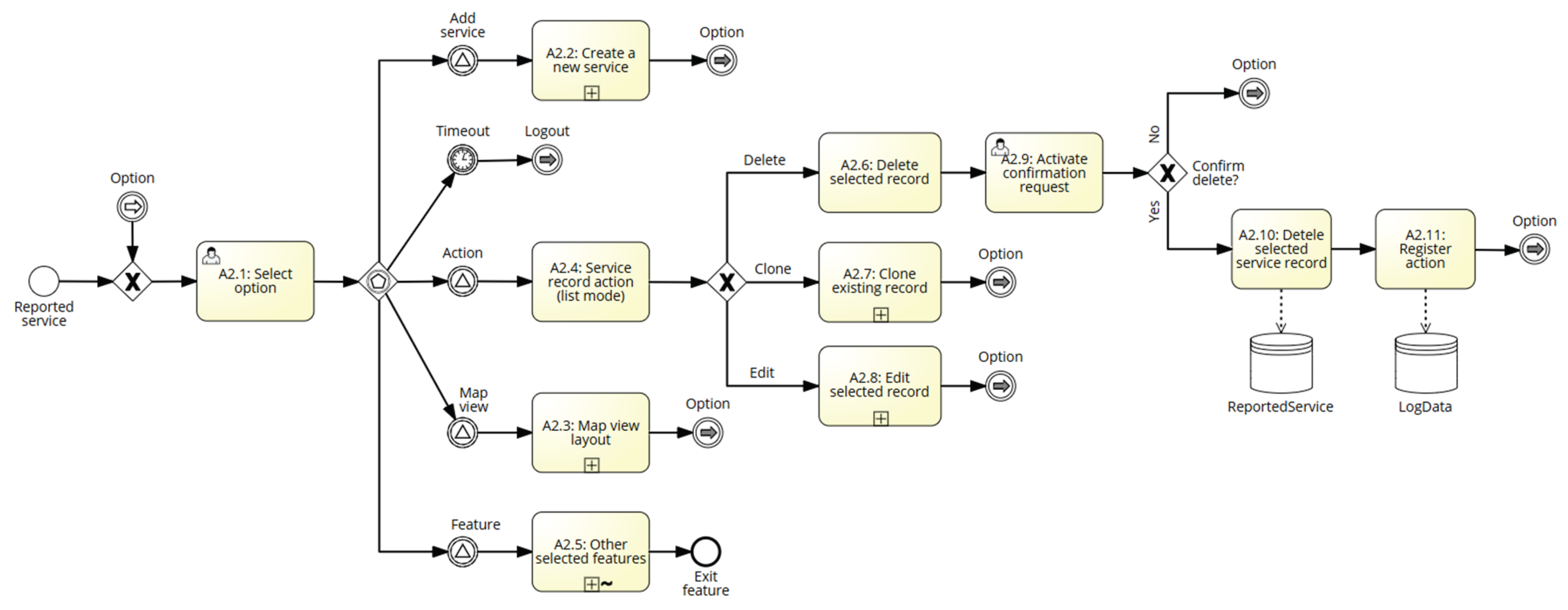

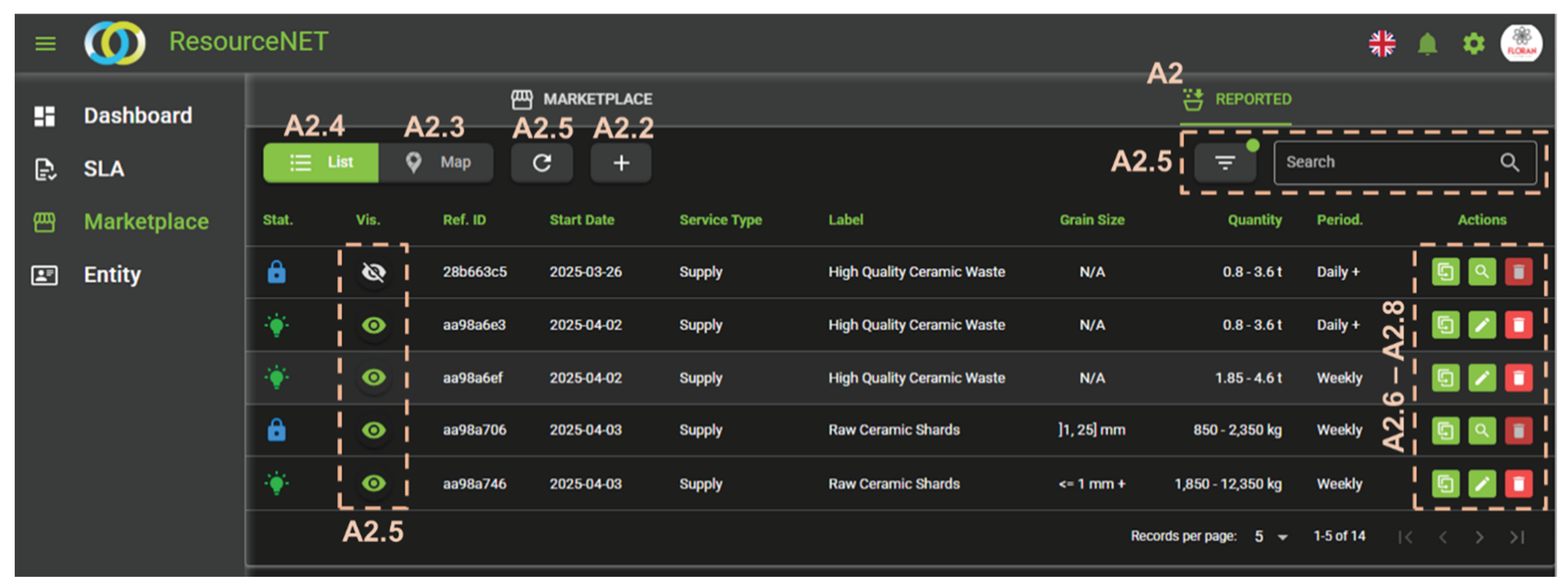

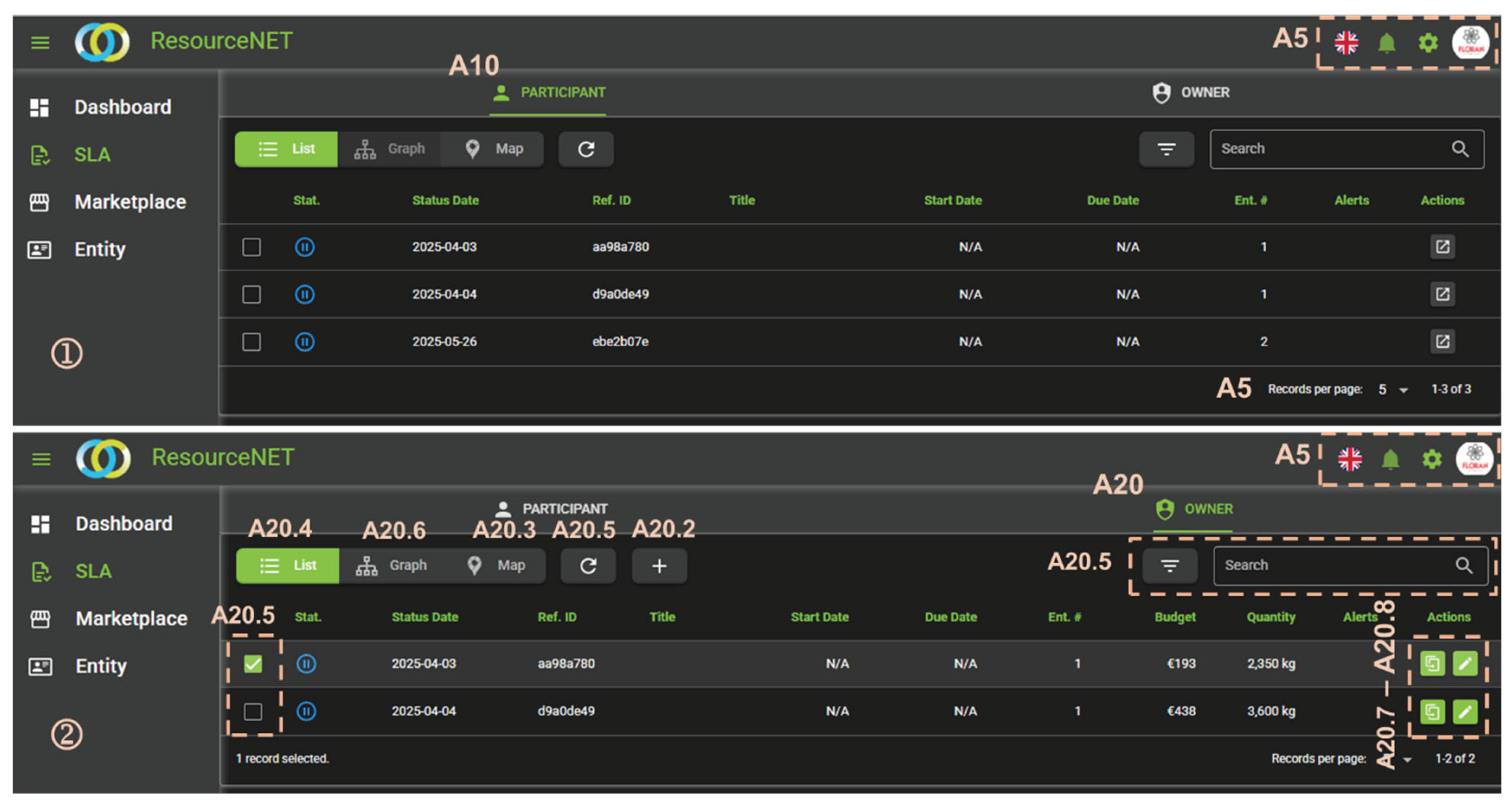

Reload Data: Synchronizes the client-side interface with the server to fetch and display the most up-to-date records. |

|

Advanced Search: Allows users to customize filters by selecting which metadata attributes to include or exclude, improving information targeting and reducing interface clutter. |

|

Visible/Hidden Toggle: Controls whether a service record is displayed on the Marketplace tab. This is key for records not in Active status (e.g., Locked), which are no longer available but may still attract interest for potential replication. |

|

Semantic Search: Filters services based on keyword matching, enhancing information retrieval through context-aware search capabilities. |

|

Audit Log Access: Grants authorized users the ability to view historical logs of changes to each record, supporting traceability and evidence-based analysis in case of disputes or system errors. |

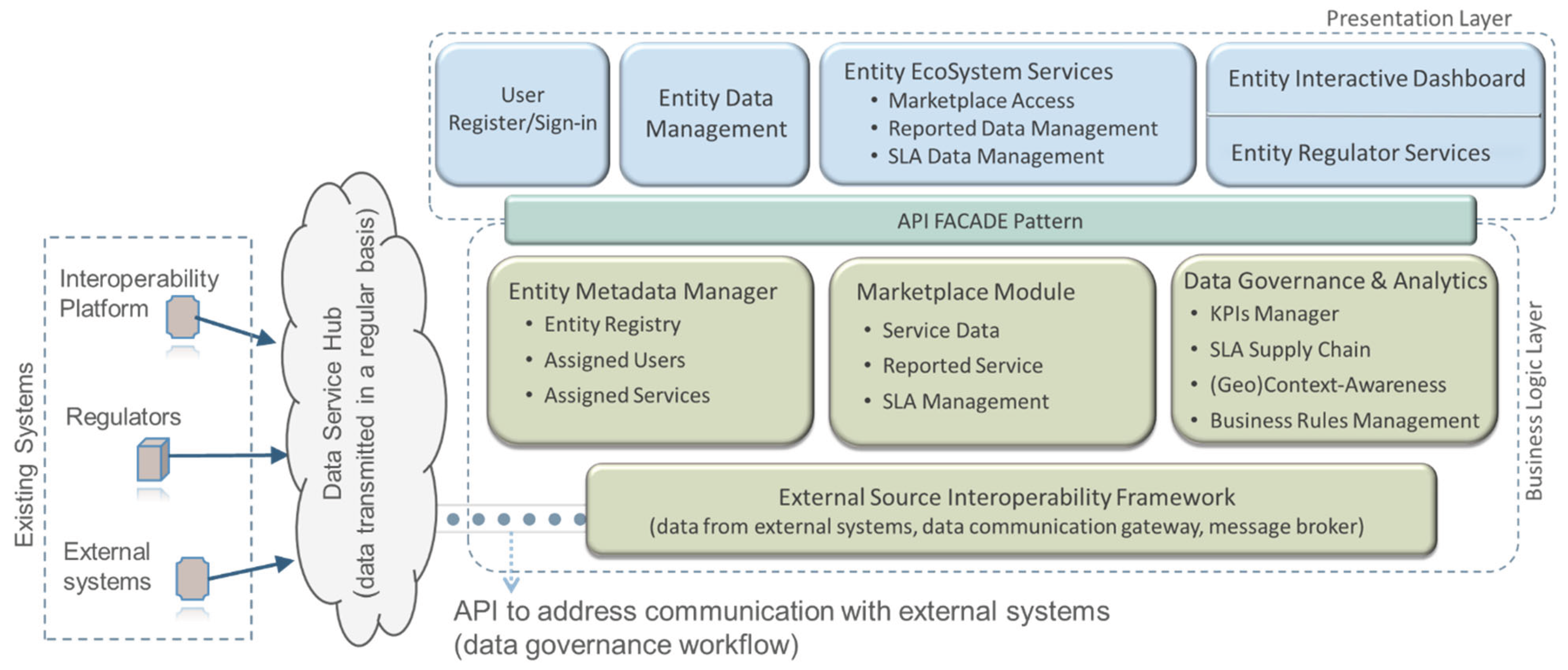

3.3. Block Diagram - Architecture Description

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. BPMN Core Elements and Symbols

|

|

References

- Z. Jwaida, A. Dulaimi, and L. F. A. Bernardo, “The Use of Waste Ceramic in Concrete: A Review,” CivilEng, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 482–500, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Magbool, “Utilisation of ceramic waste aggregate and its effect on Eco-friendly concrete: A review,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 47. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Kalaboukas, D. Kiritsis, and G. Arampatzis, “Governance framework for autonomous and cognitive digital twins in agile supply chains,” Comput. Ind., vol. 146, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Kirchherr, N. H. N. Yang, F. Schulze-Spüntrup, M. J. Heerink, and K. Hartley, “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy (Revisited): An Analysis of 221 Definitions,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 194, p. 107001, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Pestana, M. Almeida, and N. Martins, “Tracking Secondary Raw Material Operational Framework—DataOps Case Study,” Ceramics, vol. 8, no. 1, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Fugazzotto et al., “Industrial Ceramics: From Waste to New Resources for Eco-Sustainable Building Materials,” Minerals, vol. 13, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Panigrahi, R. I. Ganguly, and R. R. Dash, “Applications, challenges and opportunities of industrial waste resources ceramics,” in High Electrical Resistance Ceramics - Thermal Power Plant Waste Resources, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Oliveira et al., “Ceramic shell waste valorization: A new approach to increase the sustainability of the precision casting industry from a circular economy perspective,” Waste Manag., vol. 157, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Bueno, M. N. Pohlmann, H. A. dos Santos, and R. F. Gonçalves, “The Procurement 4.0 Contributions to Circular Economy,” Sustain., vol. 16, no. 14, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers, “Decree Law No. 102-D/2020 | DR,” Republic Diary No. 239/2020, Series 1 of 2020-12-10, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/en/detail/decree-law/102-d-2020-150908012. [Accessed: 18-Jul-2025].

- European Environment Agency, “The Waste Framework Directive 2008/98/EC in Portugal ,” 2022.

- J. dos S. Silva and M. S. A. Leite, “Analysis of a supply chain in the ceramic sector: a look at business processes,” Gestão & Produção, vol. 31, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kleopatra CHASIOTI and Chris MANADIS, “BizDevOps: A process model for the Alignment of DevOps with Business Goals,” 2019.

- Object Management Group (OMG), “Model Driven Architecture (MDA) | Object Management Group,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.omg.org/mda/. [Accessed: 18-Jul-2025].

- T. Ahmad and A. Van Looy, “Business Process Management and Digital Innovations: A Systematic Literature Review,” Sustain. 2020, Vol. 12, Page 6827, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 6827, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bucaioni, A. Di Salle, L. Iovino, and P. Liang, “Model-driven engineering for Software Architecture,” J. Syst. Softw., vol. 223, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Strnadl, “Aligning Business and It: The Process-Driven Architecture Model,” Inf. Syst. Manag., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 67–77, Sep. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Korongo, S. T. Mbugua, and S. M. Mbuguah, “A Review Paper on Application of Model-Driven Architecture in Use-Case Driven Pervasive Software Development,” Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol., vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 19–26, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Drave, J. Michael, E. Müller, B. Rumpe, and S. Varga, “Model-Driven Engineering of Process-Aware Information Systems,” SN Comput. Sci., vol. 3, no. 6, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Ahmad, T. Rana, and A. Maqbool, “A Model-Driven Framework for the Development of MVC-Based (Web) Application,” Arab. J. Sci. Eng., vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 1733–1747, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Polančič and K. Kous, “High-Level Process Modeling—An Experimental Investigation of the Cognitive Effectiveness of Process Landscape Diagrams,” Math. 2024, Vol. 12, Page 1376, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1376, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Nadal, P. Jovanovic, B. Bilalli, and O. Romero, “Operationalizing and automating Data Governance,” J. Big Data, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 117, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Paolini, D. Scardaci, N. Liampotis, V. Spinoso, B. Grenier, and Y. Chen, “Authentication, authorization, and accounting,” Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics), vol. 12003, pp. 247–271, 2020.

- N. Martin, “Overview of the Revised Standard on Architecture Description – ISO/IEC 42010,” INCOSE Int. Symp., vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 1363–1376, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Kulkarni and S. Bansal, “Utilizing the Facade Design Pattern in Practical Phone Application Scenario,” J. Artif. Intell. Cloud Comput., pp. 1–5, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Torre-Bastida, G. Gil, R. Miñón, and J. Díaz-de-Arcaya, “Technological Perspective of Data Governance in Data Space Ecosystems,” in Data Spaces, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 65–87. [CrossRef]

- G. Pestana and S. Sofou, “Data Governance to Counter Hybrid Threats against Critical Infrastructures,” Smart Cities, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 1857–1877, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fritzsch, J. Bogner, M. Haug, S. Wagner, and A. Zimmermann, “Towards an Architecture-Centric Methodology for Migrating to Microservices,” Lect. Notes Bus. Inf. Process., vol. 489 LNBIP, pp. 39–47, 2024. [CrossRef]

- EOSC, “European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) - European Commission,” European Commission, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-research-and-innovation/our-digital-future/open-science/european-open-science-cloud-eosc_en. [Accessed: 21-Jul-2025].

- INSPIRE, “INSPIRE Knowledge Base,” European Commission, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://knowledge-base.inspire.ec.europa.eu/overview_en. [Accessed: 21-Jul-2025].

| Stakeholder | Entity Role and Type of Interest in the System |

|---|---|

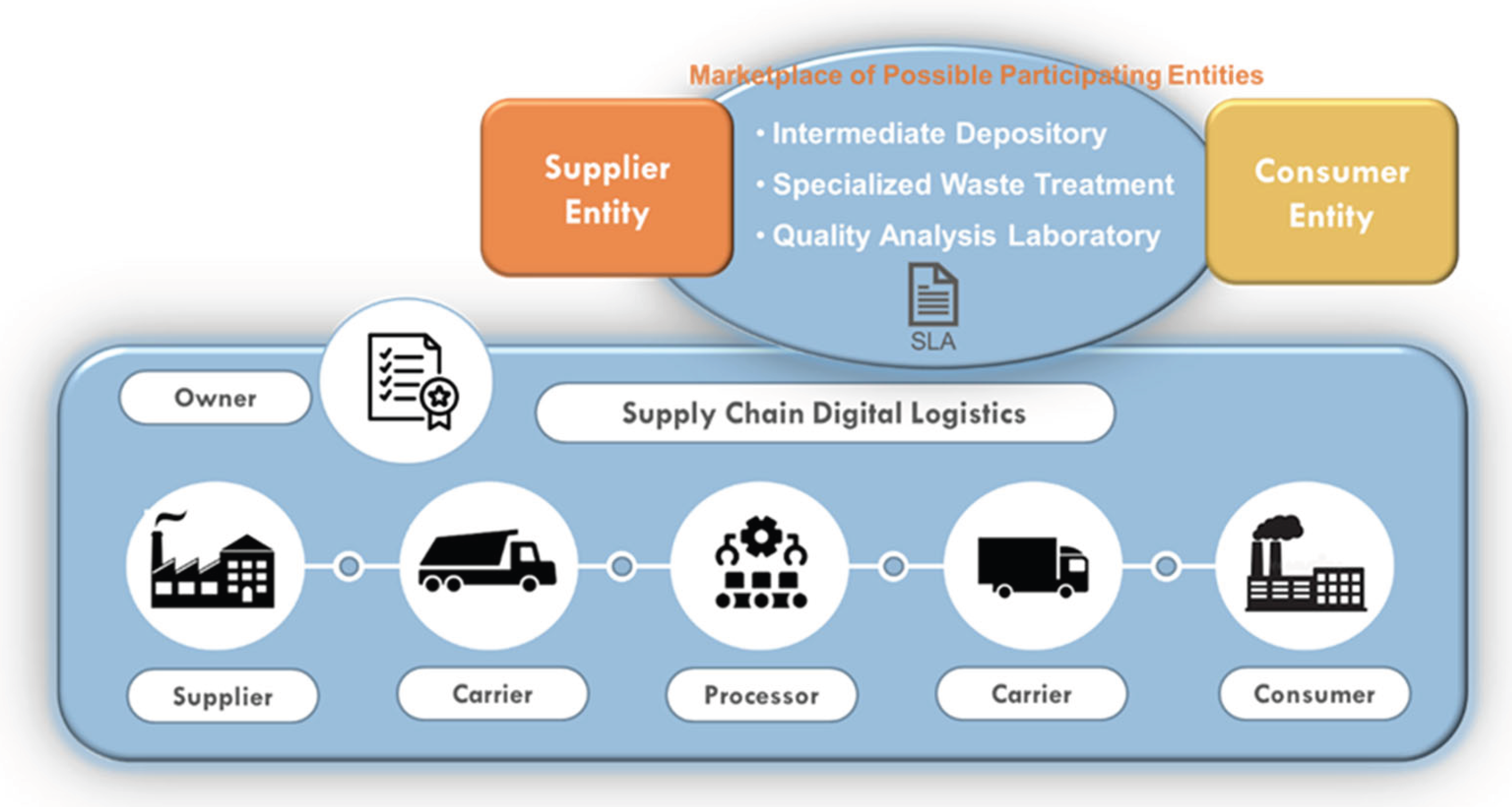

| Industry | Role: When reporting an SRM service, an entity can either report a specific need (C—consumption) or provide an availability (S—supply). It can be involved in establishing an SLA. Type of interest: Direct interest and possible promoter of actions to establish a commercial partnership. |

| Carrier | Role: An entity that operates at the level of SRM transport and may simultaneously be an industrial partner. It can be involved in establishing an SLA. Type of interest: Indirect interest |

| Processor | Role: An entity that processes SRM materials by grinding them to the necessary/specified granulometry requested by the consumer entity. It can be involved in establishing an SLA. Type of interest: Indirect interest |

| Intermediate Depositor | Role: An entity that operates solely as a temporary storage for SRM (without processing capacity). It can be involved in establishing an SLA. In some cases (e.g., when the SRM is classified as waste requiring specific treatment), the entity may need to be a specialized waste treatment and eco-recycling center. Type of interest: Indirect interest |

| Quality Analysis Laboratory | Role: An entity that performs analyses on the composition of SRM, identifying potential risk substances that may compromise the quality of the by-product or its intended use. Typically, this is a service contracted by an industry entity. Type of interest: Indirect interest |

| Owner | Role: An entity that manages the ResourceNet platform, ensuring the integrity of membership applications. Responsible for ensuring that community members use the platform as intended, avoiding situations that could compromise transparency or business requirements relevant to the sector. Has the authority to change the registration status of an entity if non-compliance is detected. Type of interest: Indirect interest, but a regulator of ethical behavior compliance within the community |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).