1. Introduction

Data sharing is the cornerstone of the digital economy, serving as a catalyst for innovation, efficiency, and collaboration across various sectors. Within the context of the European Data Economy, the seamless availability and accessibility of high-quality data are fundamental for driving technological progress, reinforcing Europe’s digital sovereignty, and fostering the development of trustworthy, human-centric AI systems that embody European values and ethical standards [

1]. In addition, with data volumes projected to grow by 120 zettabytes annually [

2], data is rapidly becoming a critical asset for generating new knowledge and driving value for individuals, businesses, and society. The economic potential of data is underscored by estimates placing its business value at 1.75 trillion dollars by 2030, highlighting the central role that data sharing and utilization will continue to play across all sectors in the years to come [

3].

As digital transformation accelerates across industrial sectors in the context of Industry 4.0, the demand for trusted platforms that enable secure and efficient data sharing has become increasingly critical. Data Spaces have emerged as a key response to this need, offering structured environments that support collaborative ecosystems and enable the seamless exchange of data among stakeholders. By fostering data sovereignty, interoperability, and trust, Data Spaces unlock new revenue streams and facilitate innovation [

4]. Positioned at the core of this evolving landscape, they provide the foundational infrastructure for a data-driven industrial economy that is both competitive and resilient [

5]. Moreover, The European regulatory landscape, comprising the Data Governance Act (DGA), and the Data Act (DA), is shaping the foundation for compliant and sovereign data exchange that aligns with European values and principles [

6].

Ensuring trust and sovereignty in data sharing is paramount, particularly in industrial domains where stakeholders rely on the integrity, security, and reliability of exchanged data. Data Spaces are designed to support transparent governance models, enabling organizations to define and enforce data usage policies, while adhering to regulatory and ethical requirements. The International Data Spaces (IDS) Reference Architecture Model (RAM)3 [

7], Gaia-X [

8], and iSHARE [

9] serve as established frameworks that provide technical, legal, and organizational mechanisms to uphold trust. These frameworks integrate certified IDS connectors, identity management solutions, auditability measures, and smart contracts, ensuring that data remains controlled, traceable, and compliant across the entire data-sharing lifecycle. At the core of this evolving niche lies the question of viable BMs: how can stakeholders create, deliver, and capture value in ecosystems designed to prioritize data sovereignty over centralization.

As Data Spaces gain prominence as enablers of secure, sovereign, and interoperable data sharing across organizational and sectoral boundaries, understanding the BMs that underpin their development and sustainability becomes increasingly critical. These BMs define how value is created, delivered, and captured across various use case, facilitating trusted data sharing and ensuring long term sustainability. Creating a sustainable BM for a data space presents unique challenges due to its multi-stakeholder nature and the need to balance value creation, participation, and economic viability. Unlike traditional BMs, a data space requires collaboration between multiple organizations—including data providers, data users, and infrastructure service providers—to ensure mutual benefits and long-term sustainability. Therefore, a data space BM is collaborative and aligned with the different BMs of the different involved participants [

9]. Finally, the BM of the data space should be monitored, reviewed, and adapted regularly to maximise its potential for growth and sustainable expansion. It is important to leverage the strengths and synergies of the existing and potential data space participants to identify growth opportunities while addressing potential challenges.

Traditional BMs often fail to encompass the complex requirements of decentralized governance, data sovereignty, and legal compliance inherent to the structure and operation of Data Spaces. To address this gap, this paper provides a structured framework for designing BMs that align with the unique characteristics of Data Spaces, emphasizing collaborative value creation, trust-based data sharing, and sustainability. Additionally, this work provides an in-depth investigation of the current landscape of BM development for Data Spaces, identifying existing approaches, underlying challenges, and emerging design patterns that support sustainable and trustworthy data sharing. Drawing insights from the manufacturing sector, we develop a taxonomy of monetization and value creation approaches that are aligned with core principles of transparency, interoperability, and regulatory alignment. Building on this foundation, we propose a BM specifically designed for the unique requirements of a manufacturing Data Space, showcasing how theoretical principles can be translated into practical, sector-specific applications. The proposed framework is validated through real-world use cases, which confirm its practical applicability and effectiveness in fostering value creation and supporting transparent value-sharing mechanisms within Data Space ecosystems. The findings further reveal that the framework promotes the development of sustainable, interoperable, and resilient Data Space environments capable of driving innovation and supporting long-term economic growth.

This rest of work is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the state of the art in BMs for Data Spaces, outlining trends in data-driven ecosystems and industrial digital platforms. In

Section 3 we outline the foundational concepts for building sustainable and viable BMs for Data Spaces.

Section 4 presents a BM development approach tailored for delivering effective BMs within a manufacturing Data Space.

Section 5 presents the validation of the proposed BMs through use cases grounded in real-world industrial challenges that enable building trusted and sustainable data ecosystems. Finally,

Section 6 provides a summary of the key findings and concludes with overarching reflections and final remarks.

2. Related Work

Nowadays, advancements in the global economy have altered the traditional balance between customer and supplier relationships. The proliferation of new communications and computing technology, coupled with the establishment of reasonably open global trading regimes, have opened the way for new opportunities in the business landscape. Businesses can now leverage digital platforms and software tools, data analytics, and global supply chains to create new products, streamline processes, and enhance customer experiences, ultimately reshaping industries and fostering greater competition on a global scale [

10]. In such a context, current businesses are required to explore more customer-centric modes of operation, especially since technology has evolved to allow the lower cost provision of information and customer solutions. In addition, these developments have amplified the need to consider not only how to address customer needs more accurately, but also how to capture value from providing new products and services [

11].

This evolving environment has leveraged the necessity to address customer needs in a less fragmented manner providing more transparent alternative solutions. Consequently, without a well-developed BM, innovators will fail to either deliver – or to capture – value from their innovations. Originally, the term BM stands for a conceptual tool that contains a set of elements and their relationships and allows to express the business logic of a specific firm [

12]. A BM reflects the strategic framework used to create and deliver the value that a company creates through its products, along with its operations and customer engagements. It articulates the logic and provides data and other evidence that demonstrates how a business creates and delivers value to customers. It also outlines the architecture of revenues, costs, and profits associated with the business enterprise delivering that value. In that sense, a viable BM leverages on balancing profitability with customer satisfaction, ensuring that the price charged reflects the perceived value of the product or service while meeting quality expectations of the customer. Thus, by effectively aligning their offerings with market demands, businesses can sustain operations and foster long-term growth [

13].

As mentioned already, Data Spaces are digital, federated infrastructures that enable participants to share and access data based on a common governance framework linked to principles such as sovereignty and trust. Data Spaces are operating without a dominant intermediary, enabling decentralized value creation. Hence, the BMs in this context should account its unique characteristics namely, data sovereignty, federated governance and trust. Over the past few years, data space initiatives have moved from theoretical constructs to operational pilots and, in some cases, early market deployments [

5]. While their architectures are still evolving, the BMs underpinning these initiatives reveal several trends that reflect the shift toward a more federated and trust-centric data economy. Frameworks like Gaia-x and IDSA propose a federated model that introduce some neutral intermediaries -such as brokers- to ensure compliance, proper usage policy and identity verification. Initiatives like Catena-X (in the automotive sector) and the Mobility Data Space are integrating with energy, health, and manufacturing Data Spaces to create interconnected ecosystems [

14]. This cross-sectoral trend is also being supported by Horizon Europe calls and EU digital strategy document. Moreover some data space operators do not directly monetize data but they prioritize enabling services such as traceability, benchmarking, or compliance tools that drive indirect value creation [

15]. This includes cost savings in supply chains or reduced regulatory burden, as seen in Catena-X or the European Health Data Space [

16].

However, transforming Data Spaces into economically sustainable ecosystems involves a complex set of challenges that span governance, economic, and technological domains. On the governance front, the absence of standardized frameworks creates uncertainty, making it difficult to establish clear rules, responsibilities, and accountability mechanisms. This is further complicated by the need to balance public-interest goals -like openness and societal benefit- with the commercial interests of private companies, leading to misaligned incentives and reluctance to share data openly [

17]. From an economic perspective, sustainability is hard to achieve due to the substantial upfront investments required to build and maintain the necessary infrastructure, including secure data platforms, interoperability layers, and coordination mechanisms [

17]. These investments are often made without immediate or clearly defined value propositions for participants, especially smaller organizations or public entities that may lack the resources to absorb initial costs. Moreover, monetization models for data sharing remain underdeveloped, creating concerns about value concentration among major actors and the distribution of benefits across the ecosystem [

18]. Technical and interoperability challenges in Data Spaces are both complex and foundational. One of the key issues is ensuring consistent data quality and standardization across different sources. Without common formats and reliable metadata, data integration becomes inefficient [

19]. It is also important the need for infrastructures that can scale securely to accommodate a wide range of participants, from small organizations and SMEs, to large enterprises, without compromising performance or data protection. However, the most challenging issue is the integration of heterogeneous systems. Data Spaces often involve legacy systems, proprietary platforms, and varying data models, making seamless interoperability difficult to achieve.

A plethora of BMing approaches has been proposed in recent literature addressing the specific needs of secure and sovereign data sharing for value creation. Among these models, Osterwalder’s process of BM innovation is based on the participation of a range of stakeholders, and his BM canvas has become immensely popular in the business world [

12]. Building on such foundational frameworks, more recent research has focused on data-centric and platform-oriented BMs that support data sovereignty, interoperability, and trust frameworks, particularly within the context of European Data Spaces. For example, the International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) and the GAIA-X initiative have introduced reference architectures and governance models to support sovereign data exchange while enabling sustainable value creation among ecosystem participants [

20,

21]. Similarly, other recent studies have proposed extensions to incorporate data governance mechanisms, sharing incentives, and regulatory compliance, reflecting the increasing complexity of data-driven value networks [

22]. Collectively, these developments underscore a shift from traditional BM frameworks toward dynamic, data-driven approaches that integrate technological, regulatory, and collaborative dimensions to enable secure and sovereign value creation in modern data ecosystems.

3. BMs in Data Spaces

The conceptualization and design of BMs for Data Spaces presents distinctive challenges that differ fundamentally from those observed in traditional or even hybrid digital business environments. Traditional BMs are typically organization-centric, focusing on how a single entity creates, delivers, and captures value through a well-defined value proposition and direct relationships with customers. In such models, data and resources are controlled internally, and value generation occurs largely within the boundaries of one firm. Hybrid BMs, which are increasingly prevalent in digital ecosystems and platform-based economies, extend this perspective by involving multiple stakeholders who contribute complementary resources or services. Despite their collaborative nature, these models usually maintain a clear hierarchical structure, with a central orchestrator or platform owner governing the value creation and distribution mechanisms [

11].

In contrast, BMs for Data Spaces embody a decentralized and federated paradigm. They are inherently multi-stakeholder and collaborative, encompassing data providers, consumers, intermediaries, and governance entities—each with unique objectives, requirements, and revenue expectations. These must be aligned within a digitally enabled, trust-based collaboration framework that ensures data sovereignty, interoperability, and regulatory compliance. Such configurations create a complex environment where individual value capture is often less direct and more diffuse, potentially discouraging participation without clear incentive alignment. Consequently, Data Space BMs emphasize the co-creation of value through the design and implementation of use case–driven collaborations, ensuring that benefits are distributed equitably across all participants. This section examines these distinctions in depth, providing a conceptual foundation for the subsequent development of a structured framework for Data Space BM design [

23].

BMs of Data Spaces are inherently dynamic and tend to evolve over time as the ecosystem matures. Often, hybrid models emerge that combine elements of various revenue and value-capture strategies to better meet the diverse needs of participants and to balance economic sustainability with collaborative governance. Real-world initiatives demonstrate such evolution as Data Spaces move from pilot stages to operational ecosystems [

21].

3.1. Data Spaces Business Objectives

Typically, the key purpose of establishing a Data Space is to enable a trustworthy environment for secure and controlled, in terms of sovereignty, data exchange between participants for value creation, abiding to a certain set of rules. However, Data Spaces can be enabled among ecosystem members with the purpose of achieving customer innovation (Joint Innovation), fulfilling common objectives such as operational efficiency, regulatory compliance etc. (Cost Sharing), preventing the emergence of limited dominant players in the market (Combined Forces Ecosystem), providing quality-assured, easy access to data of a domain of common interest such as open data, business partner data, etc. (Shared Marketplace) and finally delivering societal impact through a public and private sector collaboration (Greater Common Good) [

24]. The evolution and hybridization of BMs are evident as traditional frameworks increasingly integrate with data-centric, platform-oriented, and governance-driven approaches, complementing the growing recognition of non-monetary value forms—such as data-driven innovation, regulatory compliance facilitation, and sustainability objectives—alongside traditional economic incentives in manufacturing ecosystems [

21]. Additionally, BMs in Data Spaces increasingly recognize non-monetary value forms such as data-driven innovation, regulatory compliance facilitation, and sustainability objectives, which complement traditional economic incentives in manufacturing ecosystems [

25].

In essence, these patterns can be summarized in three key strategic motivations for Data Space establishment:

Commercially driven, where participants are usually charged for using the Data Space, which remains well-maintained and valuable, professional services are offered.

Cooperative Initiatives, where participants take part in decision-making, have equal stakes and share in the benefits.

(Non) Governmental or NGO-Driven, usually initiated by public bodies or NGOs and prioritize societal impact, while still remaining sustainable in the long-term.

Therefore, newly established Data Spaces are typically driven by either of the three key strategic motivations, adopting one of the presented business patterns among the participants.

3.2. Data Spaces Main Actors and Roles

As collaborative ecosystems, Data Spaces enable value creation among participants. To fully capture this value, it is essential to identify the role each participant plays within a data space or a specific co-creation use case. While slightly different or expanded terms appear in the literature, they generally converge on the following core roles, which are described in

Table 1.

These roles collaborate to enable a framework for the execution of Data Space Use Cases to deliver value to all involved participants. Note that not all roles appear in every data space, and the specific governance and trust provider arrangements vary depending on the domain, size, and maturity of the ecosystem.

3.3. Data Spaces Revenue Models

To capture this value delivery in economic perspective, we must recognize the different data monetization pathways that are pertinent to Data Spaces. These pathways refer to the process of transforming data into financial value, allowing organizations to leverage their or other parties’ data assets for revenue, value creation or innovation stimulation. As such, the monetisation strategies for Data Spaces focus on leveraging data as a strategic asset that drives value across various touch points within the ecosystem.

Table 2 outlines distinct monetization models uniquely identified for Data Spaces, highlighting the different strategies that can be employed to generate revenue from shared data assets.

These monetization models and participant roles reflect those observed in leading data space deployments such as Catena-X [

16] in automotive manufacturing and the Smart Connected Suppliers Network (SCSN) [

26] in high-tech equipment supply chains. These initiatives demonstrate how adaptable BM configurations, combined with collaborative governance, enable trusted and economically sustainable industrial data ecosystems.

Data Spaces adopt either of these monetization pathways or even a combination of those, depending on the needs, to drive economic benefits. The appropriate revenue model for a Data Space must be determined considering both the strategic drivers and business objectives of the data space, the type of participating actors, and -most importantly- the domain (or cross-sector domains) in which it operates.

4. Business Model Innovation for Manufacturing and Industrial Assets

In industrial settings, data-sharing ecosystems must support interoperability and sector-specific requirements, ensuring that participants derive both economic and strategic value. This section presents the BM development approach and offers a structured overview of the key strategic components necessary for designing and delivering effective BMs focusing on Data Spaces for the Manufacturing Sector and Assets (DS-MSA). Emphasizing long-term viability, the BMs of a DS-MSA are designed to adapt to evolving market dynamics and regulatory environments. Importantly, the BM for a manufacturing data space is not static; it consists of multiple models for different actors and often evolves over time to meet the changing needs and opportunities within the ecosystem. A key objective is to demonstrate how a trusted data exchange can unlock greater revenue opportunities for participants, particularly when operating with digital assets in highly regulated or rapidly shifting sectors where traditional scaling approaches may fall short. Effective BMs facilitate collaborative innovation, cost-sharing structures, and new market opportunities, making Data Spaces a foundational element for the future of data-driven manufacturing.

4.1. Mapping User Needs to Business Capabilities

In most Data Spaces customers require a secure, transparent, and compliant infrastructure for exchanging data across organizations and borders. This infrastructure should enable trustworthy collaboration through strong mechanisms for identity management, access control, and data protection in line with relevant regulatory frameworks. They also need a modular and scalable environment that allows seamless integration of diverse tools and services, including user management, secure data connectors, and automated rule enforcement. Data usage policies must be clearly defined and automatically verified before any exchange occurs, ensuring that only authorized participants can access or share information for approved purposes. Moreover, to maintain data sovereignty and operational control, customers expect a decentralized, peer-to-peer data exchange model where data remains under the ownership and jurisdiction of its providers. Transparency and accountability are also essential—requiring detailed activity records, auditable transactions, and rule-based governance to guarantee compliance and traceability.

To address the complex requirements of secure, sovereign, and interoperable data exchange in DS-MSA, the appropriate infrastructure provides a modular architecture that aligns with both user needs and regulatory expectations.

Table 3 summarizes how key functional capabilities of the Data Space map to core user requirements and the corresponding value they deliver. The focus is on enabling trusted data transactions, enforcing granular control policies, and ensuring legal compliance within a federated, decentralized ecosystem—particularly relevant for manufacturing and other data-intensive sectors.

4.2. Value Proposition

The value proposition of the DS-MSA defines the distinct benefits, conditions, and costs for all participants, ensuring mutual value creation. Operating an evolving Data Space platform offers a compelling value proposition marked by both strategic advantage and prestige. As the orchestrator of a trusted digital ecosystem, the operator gains monetization opportunities through platform fees, and value-added services such as analytics and AI tools. The operator acts as a neutral facilitator, providing the technical infrastructure and ensuring compliance with collectively agreed rules. This role does not undermine the federated nature of the data space; rather, it enables practical operation and scalability The Operator delivers a modular, scalable, and regulation-compliant infrastructure that enables industrial and other relevant stakeholders to share data securely, transparently, and on their own terms.

Beyond this, the operator plays an important role in identifying, attracting, and onboarding high-impact use cases, while also supporting their continuous development and evolution, providing significant value to various users. For data providers such as refineries and wind farms, the primary motivation for collecting and analysing operational data is to optimize their own performance by anticipating failures, minimizing downtime, and extending asset life. By leveraging data internally, providers gain immediate, tangible benefits in efficiency, safety, and cost reduction. For data consumers, the value proposition includes the availability of high-quality, curated data and AI-driven insights to help them make informed decisions. In addition to financial incentives, successful DS-MSA deployments deliver critical non-monetary value, including compliance with environmental and data regulations, increased transparency, and the ability to innovate rapidly in response to emergent supply chain or sustainability challenges.

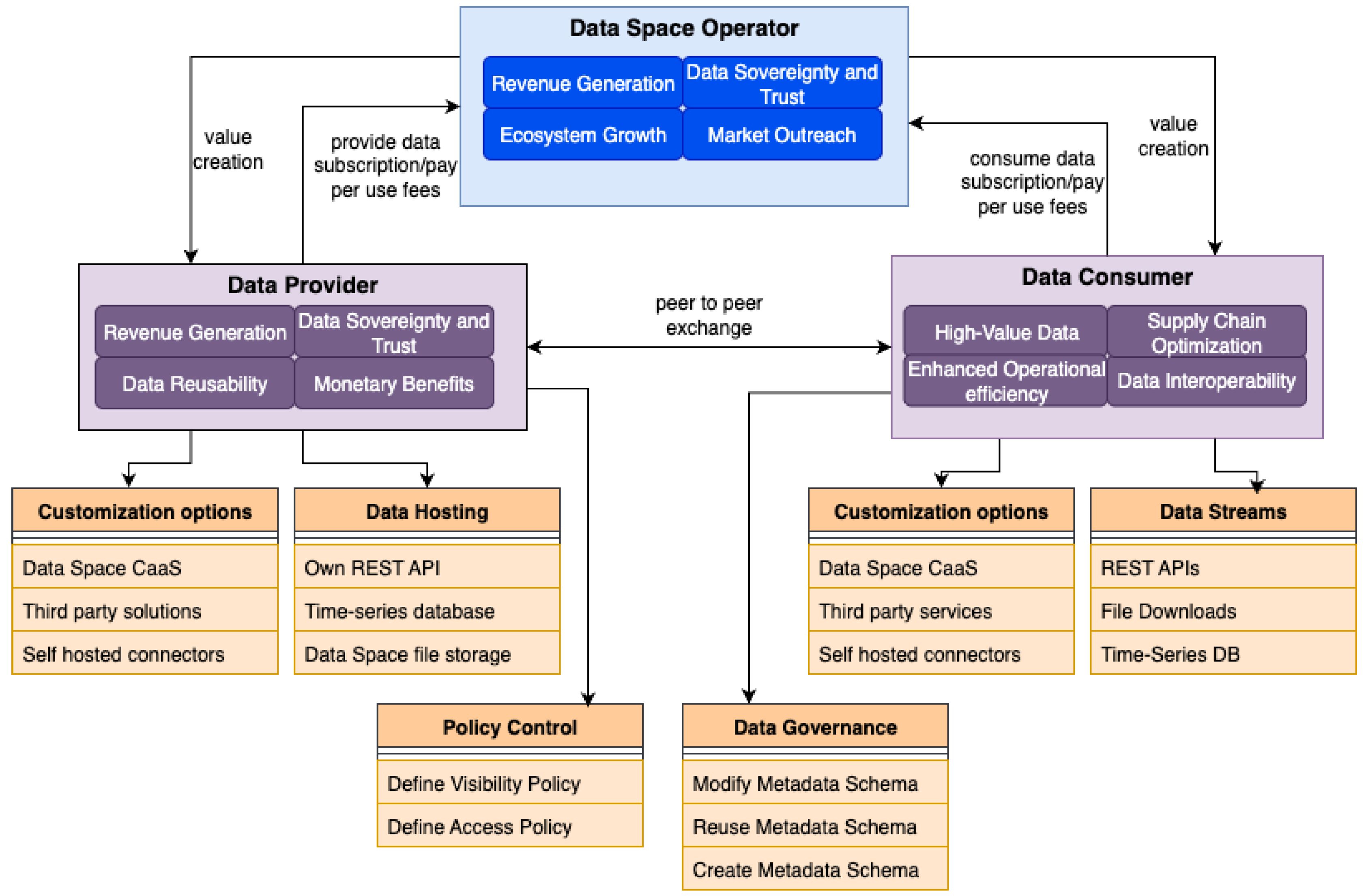

4.2.0.1. Value proposition for DS-MSA Operator:

Revenue Generation: The Operator can generate recurring revenue from participants through subscription fees for access to the platform, premium features, and data hosting options.

Ecosystem Growth and Network Effects: As more participants (data providers, consumers, and service providers) join the data space, the Operator benefits from network effects. Each new participant adds value to the ecosystem, increasing the utility and attractiveness of the platform for others.

Scalability and Market Outreach: The flexibility and customizability of DS-MSA enables the Operator to cater to diverse industries and sectors, further expanding their reach and customer base.

Data Sovereignty & Trust: The Operator can create additional value through data sovereignty guarantees, offering assurance to participants that their data is securely hosted and only shared under strict access policies.

4.2.0.2. Value proposition for Data Providers:

Ease of Use: A user-friendly platform that simplifies the complexities of data discovery and exchange. It offers secure, diverse data hosting services that reduce integration costs and support platform adoption.

Broader Market Reach: Data providers can gain greater visibility to a wider pool of potential buyers, opening new revenue opportunities and lowering acquisition costs. Data assets are described and searchable on a granular level.

Trust, Security and Data Sovereignty: Ensures trust in the data exchange mechanism, giving control over how data is accessed and used.

Usage of analytics services: Seamless integration of third-party analytics services; e.g. for predictive maintenance.

Monetary Benefits: Opportunity to monetize data and unlock financial value.

Data Reusability: Discovery of new purposes and use cases for data assets.

Compliance with EU Regulations: Adherence to legal frameworks such as the Data Act and Data Governance Act.

4.2.0.3. Value proposition for Data Consumers:

Real-time Access to High-Value Data: Real-time access to data enables services such as optimization and predictive maintenance.

Access to High-Value Large Amounts of Data: Development of more advanced models due to large amounts of available training data.

Secure and Interoperable Ecosystem: Standards-based infrastructure ensuring data sovereignty and privacy.

Data interoperability: Supporting interoperability to support merging of datasets from different sources.

Enhanced Operational Efficiency: Real-time data exchange supports processes and services, such as predictive maintenance, that depend on real-time capabilities.

Compliance with EU Regulations: Adherence to legal frameworks such as the Data Act and Data Governance Act.

4.2.0.4. Value proposition for Service Providers and Other Stakeholders:

Secure Data Sharing: Access to high-quality data assets within a secure infrastructure.

Greater Visibility: Exposure to a broader audience of potential data providers.

Expanded Service Offerings: Access to diverse datasets enables development of new services and applications.

Faster Time to Market: Standardized formats and tools reduce onboarding time and speed up development.

Real-time Services: Real-time manufacturing data improves insight generation and optimization across use cases.

In

Figure 1, the business roles of the DS-MSA are illustrated, together with the relationships between these roles and the types of value they generate. The diagram highlights how the different actors interact within the ecosystem, the flows of data and services among them, and the resulting benefits that emerge from these exchanges.

4.3. Revenue and Pricing Models

To ensure that a Data Space remains both sustainable and scalable, it is crucial to establish revenue and pricing models that reflect the needs of different stakeholders. By adopting multiple monetization approaches, the DS-MSA can maintain a trusted, compliant, and service-oriented platform, while ensuring that revenue generation remains closely aligned with actual usage and the value created within the ecosystem. These strategies not only secure the long-term sustainability of the platform but also promote balanced growth across all participants.

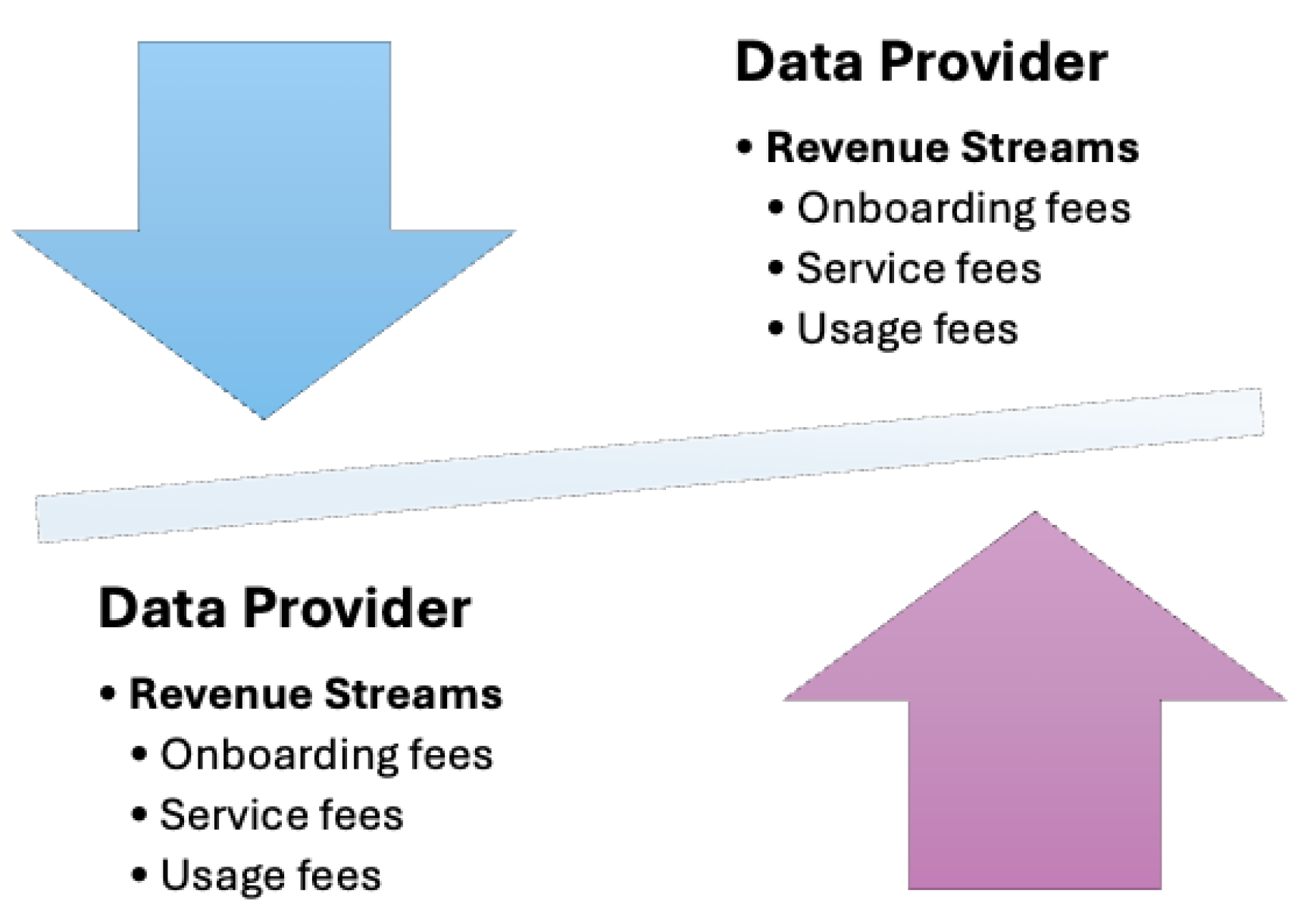

Figure 2 illustrates the main revenue streams within the DS-MSA, highlighting the complementary financial contributions made by data providers and data consumers. Providers primarily contribute through onboarding, service, and usage fees associated with data supply and platform integration, while consumers contribute via similar categories linked to access, value-added features, and consumption levels. Together, these revenue streams establish a balanced ecosystem in which both groups play an active role in sustaining and expanding the Data Space.

In a DS-MSA, a variety of monetization strategies can be employed to balance sustainability with fairness across stakeholders. Common approaches include subscription-based access, where participants pay recurring fees for continued use of services and resources, and pay-per-use models, in which costs are tied directly to the actual consumption of data or platform services. In practice, many Data Spaces adopt a hybrid strategy, combining elements of both to accommodate diverse user needs while maintaining flexibility. These mechanisms not only provide a stable source of revenue for the Data Space Operator but also ensure that charges are proportionate to the value generated and exchanged within the ecosystem.

Building on these principles, two primary models are proposed to guide the monetization of the DS-MSA. The first emphasizes predictable, recurring revenue streams through subscription structures, while the second focuses on pay-per-use based pricing that directly links costs to usage intensity.

4.3.0.5. a. Subscription-Based Model

The subscription-based model offers predictable, recurring revenue by providing access to the data platform and its core services, such as connector deployment, maintenance, and integration. The Data Space Operator benefits from stable revenue streams through subscription models and value-added services such as Connector-as-a-Service (CaaS), enabling predictable financial planning and investment in platform growth. This model fosters long-term engagement from participants, which is crucial for encouraging consistent usage and user loyalty. Additionally, the Operator plays a key role in driving ecosystem growth by ensuring a trusted, secure, and compliant data-sharing environment. The following

Table 4 outlines the different types of charges applied to key stakeholders—Data Providers and Data Consumers—within the Data Space, along with examples and billing frequency.

4.3.0.6. b. Pay-Per-Use Model

The pay-per-use model charges data consumers based on their actual consumption of data and related services. Instead of a fixed subscription, each interaction with the Data Space incurs a transaction-based fee. This model introduces a dynamic revenue stream for the DS-MSA, where income grows in direct proportion to ecosystem engagement. The more actively participants consume and exchange data, the greater the revenues generated for both the Operator and the contributing providers.

In practice, pay-per-use fees can take different forms depending on the stakeholder role. Data providers may charge for onboarding support, integration costs, hosting, or per-request usage, while data consumers incur costs for platform access, advanced service features, or dataset transactions. These fee structures ensure that costs are fairly distributed across the ecosystem, linking payments to the actual value received by each participant.

Table 5 summarizes the revenue streams associated with the pay-per-use model, illustrating how both providers and consumers contribute to the sustainability of the DS-MSA through onboarding, service, and usage-related fees.

For the DS-MSA, ensuring long-term viability and sustainability depends on a transparent understanding of the underlying financial considerations and cost structure. Operating a Data Space requires the continuous management of several key expenses, including cloud infrastructure and hosting, platform updates and maintenance, user onboarding and customer support, regulatory compliance and legal monitoring, as well as marketing and community engagement. These cost components are not one-time outlays but recurring commitments that grow in line with platform activity and user adoption. Over time, such expenditures are expected to be balanced—and ultimately offset—by the revenue generated through the monetization models proposed in the overall business strategy. This alignment ensures that the platform remains operationally reliable, financially resilient, and attractive to stakeholders.

It is important to note that not all revenue or cost components are mandatory for every DS-MSA deployment. The modular nature of these models allows data space operators to adapt to sector-specific priorities, participant readiness, and evolving regulatory environments.

The following

Table 6 presents a structured overview of the financial requirements for setting up and running the Data Space. It distinguishes between mandatory costs, which are essential to guarantee basic operations, and optional costs, which add strategic value by supporting growth, visibility, and compliance. Each category is described with concrete examples, ensuring a clear link between the platform’s operational needs and the financial strategy required to sustain them.

5. BM Application Through the Use-Cases

Having developed appropriate BMs and identified the main actors, a subsequent step is to assess their value propositions and their viability in the context of an actually implemented data space. UNDERPIN is a pan-European project [

27] aimed at demonstrating scalable, trusted, and interoperable Data Spaces for dynamic asset management and predictive maintenance in manufacturing and renewable energy sectors. Its real-world use cases emphasize collaboration among SMEs and industry leaders, ensuring regulatory compliance and fostering innovation. For this, we use the manufacturing data space that has been developed in the UNDERPIN project, which focuses on manufacturing and asset management. The validation shall be proven by analyzing two distinct use cases pertaining to predictive maintenance in: a) refinery (manufacturing) and b) a wind farm (industrial assets). For both use-cases, data-driven models are developed for carrying out predictive maintenance. The previously derived value propositions (Sec.

Section 4) shall be discussed in each use-case, which allows an examination of real-world operational scenarios, which is crucial for a realistic validation of the BMs. The validation of the proposed BMs considers key aspects such as operational scalability, cost-effectiveness, value realization for diverse stakeholders, and alignment with European data governance standards. As the project is still in progress, the presentation of tangible results remains subject to ongoing development and refinement. A summary of relevant value propositions to the use-cases is presented in

Table 7.

5.1. Refinery Use-Case

The goal of the refinery use case is to the application of machine learning to anticipate equipment failures in manufacturing before they occur. Instead of relying on fixed maintenance schedules or reacting to unexpected breakdowns, a system continuously analyzes sensor data to detect early signs of wear, degradation, or abnormal behavior across the entire production chain. This enables the refinery to appropriately schedule maintenance works for impending failure, as well as to apply corrective actions without interrupting operations based on detected abnormal behaviour. As a result, the refinery can minimize operational disruption, enhance reliability, increase safety and reduce maintenance costs, while the system becomes smarter over time, enabling better decision making. In this case, the refinery shares data volumes exceeding 2 TB / year from a variety of sources, including thermometers, pressure sensors, axial displacement sensors and vibration sensors from five machine groups involved in the main refinery process. The available data for training span seven years of operation. Using time series prediction models that forecast values 24 hours in advance, we are able to identify the best fit for predictive maintenance in a refinery setting. The type of data is tied to the specific sensor positions along each production line, which vary between refineries. Therefore, data from different refineries cannot be merged, and data reusability is not supported. This predictive maintenance service can be offered to the refinery via the UNDERPIN data space by registered service providers. The data space allows a smooth integration between the two parties and ensures the transfer of data in real-time without direct access to each other’s premises using a data space connector, thereby promoting data sovereignty and interoperability. The data return to the refinery via the connector and the data space dashboard enables better visualization and interpretation of the results. Connecting these datasets with different data sources - such as maintenance records, production throughput, environmental conditions near the machinery - could increase the accuracy and interpretability of predictive maintenance outcomes. The data space setup enables integration with vendor data and on-site observations and supports further efforts for algorithm development by external parties.

5.2. Wind Farm Use-Case

The goal of the wind farm (WF) use-case is the timely prediction of failures of major components of wind turbine generators (WTG). This enables the WF operator to be able to monitor potential abnormalities in the operation of the WF. In this way, the operator has the opportunity to request real inspections by site engineers and maintenance work can be carried out, if needed. For implementing such a service, the WF operator can look for a predictive maintenance service as offered by by third parties registered with the UNDERPIN data space. The data space allows a seamless integration of services offered via the data space into the wind farm operator’s infrastructure. This approach ensures that such predictive maintenance services can be easily adopted to the specific requirements, and the same applies to the service provider. The WF operator collects large amounts of SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) data from its wind turbines, which includes key operational parameters like wind speed, rotor speed, wind direction, power output, and temperature. This data can be used to develop data-driven models to detect core component anomalies of WTG, which indicate early failures. WF operators are considered as critical infrastructure so that data sovereignty and security are of great importance, since large amounts of data need to be exchanged between the WF operator and predictive maintenance service provider. The data exchange can be technically easily realised between two entities by using the data space’s connectors. These connectors enable data exchange without any direct access to the WF operator’s premises, which is of great importance for critical infrastructure. Moreover, by using the connector a flexible integration of exchanging data is possible, not only the actual data exchange but also legal regulations. In this particular use-case there are very few examples of actual component failures. For instance, Weissenfeld et al. [

28] reported of ten major component failures of a wind farm with ten WTG over a six year period. Hence, for training a supervised model a large amount of data is necessary; considering additional data source. For this, the data space provides access to high-quality datasets and interoperability, so that data can be merged for training models. In addition, climate data (e.g. Copernicus data [

29]) can improve predictive maintenance for certain WTG components. If the data space provides this kind of data, SCADA and climate data can be easily merged. Afterwards the trained model can be used for predicting anomalies in the daily operation. In this particular use-case 24 hours periods of data are submitted to the service provider, which executes the model on this data and generates output data with the potential anomalies. This data is returned to the WF operator via the connector. Note, that the data space offers a dashboard to visualize the results, which helps the operators to interpret the results.

5.3. Discussion

The use cases implemented by UNDERPIN demonstrate both the advantages and practical challenges of deploying Data Spaces in real industrial settings. Key lessons learned include the importance of flexible governance structures, consistent data standards, and clear value-sharing mechanisms for stakeholders. Using a manufacturing data space to enable predictive maintenance in the previously introduced use-cases provides significant value despite the associated costs as outlined in

Table 6. Some functionalities (e.g. trustful and secure data exchange) offered by the data space are mandatory to realize the predictive maintenance service. Otherwise, a different proprietary solution would need to be used, which could be even more expensive. Data space costs are significantly reduced as the number of participants increases, since certain fixed costs can be shared among them. The main benefit of using a data space is the scalability of available datasets and services with more participants, which in turn lowers costs and creates new business opportunities.

The cases introduced also demonstrate that the same Data Space infrastructure is not only scalable across multiple participants, but also across different industrial sectors (refinery, wind farms), further bringing down the costs as more stakeholders of the broader ecosystem become relevant. Both use cases set the ground for a predictive maintenance service which can be enhanced with the combination of complementary data assets and the participation of external parties, contributing to analytics services and AI models’ provision. These parties can enjoy the trust environment of the Data Space, backed by the digital sovereignty principles adopted, as well as its compliance with relevant EU data policies and standards, while integrating seamlessly those services with their existing operations. Lifting the interoperability and ownership barriers for data exchange, the data space enables service provision and generates operational benefits such as reduced downtime or lower costs. In doing so, it acts as a sustainability driver for all participants.

While the benefits are clear, ongoing challenges remain—including managing data quality, interoperability across legacy systems, and coordinating participation among heterogeneous stakeholders. Addressing these hurdles is essential for maximizing the impact of future data space deployments under the Digital Europe Programme.

6. Conclusions

Data sharing stands as the fundamental pillar of the digital economy, driving innovation, efficiency, and collaboration across diverse sectors. As data volumes grow exponentially and its economic value continues to surge, effective data sharing mechanisms become essential for generating value across individuals, businesses, and society at large. Within this evolving landscape, Data Spaces represent a key enabler for establishing trust frameworks that provide transparency, accountability, and governance in data-sharing ecosystems, while the BMs that underpin their development and sustainability becomes increasingly critical. Yet, the sustainability of Data Spaces hinges on viable, collaborative BMs that balance the interests and contributions of multiple stakeholders, including data providers, users, and infrastructure operators.

Our work introduces a structured framework for BM development, emphasizing collaborative value creation, interoperability, trust, and long-term sustainability. Through a comprehensive analysis of existing approaches and emerging design patterns, particularly within the manufacturing sector, we define a taxonomy of monetization and value creation strategies aligned with principles of transparency and collaborative value creation. Building on this foundation, we validate the proposed BM framework through the UNDERPIN use cases, which demonstrate its practical applicability and effectiveness in real-world Data Space implementations. The findings confirm that the framework enables value creation through flexible governance structures, harmonized data standards, and transparent value-sharing mechanisms, supporting the sustainable growth of Data Space ecosystems. Future enhancements will focus on expanding and refining the validation of the proposed BM framework through the UNDERPIN use cases, This will generate broader empirical insights into the framework’s flexibility and robustness, demonstrating its capacity to adapt to diverse operational environments, regulatory landscapes, and market conditions across multiple sectors.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis and Victoria Katsarou; methodology, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis, Victoria Katsarou, George Fragiadakis, George Dimitrakopoulos, Christos Papaleonidas, Sotiris Tsakanikas and Panagiotis Papadopoulos; validation, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis and Victoria Katsarou; formal analysis, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis and Victoria Katsarou; investigation, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis and Victoria Katsarou; resources, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis, Victoria Katsarou, George Fragiadakis, George Dimitrakopoulos, Christos Papaleonidas, Sotiris Tsakanikas and Panagiotis Papadopoulos; data curation, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis, Victoria Katsarou and George Fragiadakis; writing—original draft preparation, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis, Victoria Katsarou and George Fragiadakis; writing—review and editing, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis, Victoria Katsarou, George Fragiadakis, George Dimitrakopoulos, Christos Papaleonidas, Sotiris Tsakanikas and Panagiotis Papadopoulos; supervision, George Dimitrakopoulos, Christos Papaleonidas, Sotiris Tsakanikas and Panagiotis Papadopoulos; funding acquisition, Elena Politi, Axel Weissenfeld, Aristotlelis Ntafalias, Giorgos Chrysokentis, Victoria Katsarou, George Fragiadakis, George Dimitrakopoulos, Christos Papaleonidas, Sotiris Tsakanikas and Panagiotis Papadopoulos. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”, please turn to the

CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the UNDERPIN project (Digital Europe Program, Grant Agreement no. 101123179).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Soininen, J.P.; Laatikainen, G. What is a Data Space–Logical Architecture Model. Data in Brief 2025, p. 111575.

- Edge Delta. 11 Insightful Statistics on Data Market Size and Forecast. https://edgedelta.com/company/blog/data-market-size-and-forecast, 2024. Accessed: YYYY-MM-DD.

- Edge Delta. 11 Insightful Statistics on Data Market Size and Forecast, 2023. Accessed: 2025-06-17.

- Curry, E.; Scerri, S.; Tuikka, T. Data spaces: design, deployment and future directions; Springer Nature, 2022.

- Bacco, M.; Kocian, A.; Chessa, S.; Crivello, A.; Barsocchi, P. What are data spaces? Systematic survey and future outlook. Data in Brief 2024, 57, 110969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outeda, C.C. The EU’s AI act: a framework for collaborative governance. Internet of Things 2024, p. 101291.

- International Data Spaces Association. International Data Spaces Reference Architecture Model Version 3.0. Technical report, International Data Spaces Association, Berlin, Germany, 2020. White Paper.

- Tardieu, H. Role of Gaia-X in the European data space ecosystem. In Designing Data Spaces: The Ecosystem Approach to Competitive Advantage; Springer International Publishing Cham, 2022; pp. 41–59.

- iSHARE Foundation. iSHARE Trust Framework. Technical report, iSHARE Foundation, The Hague, Netherlands, 2020. Version 1.3.

- Touati, K.; Aljazea, A. The Impact of Information and Communication Technologies on International Trade: The Case of MENA Countries. Economies 2023, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Rauter, R.; Pedersen, E.R.G.; Nielsen, C. Sustainable value creation through business models: The what, the who and the how. Journal of Business Models 2020, 8, 62–90. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers; Vol. 1, John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Westerveld, P.; Fielt, E.; Desouza, K.C.; Gable, G.G. The business model portfolio as a strategic tool for value creation and business performance. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2023, 32, 101758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobility Data Space Association. Mobility Data Space – Data Sharing Community for the Mobility Sector. Website, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-11.

- Deloitte Insights. Monetizing Data and Technology. Online article, Deloitte Insights, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-11.

- Catena-X Automotive Network, e.V. . Catena-X Welcomes EU Omnibus Proposal: The EU Omnibus Confirms Continued Relevance for Sustainability Reporting and Supply Chain Data Collection. Online news release, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-11.

- Marcucci, S.; Alarcón, N.G.; Verhulst, S.G.; Wüllhorst, E. Informing the Global Data Future: Benchmarking Data Governance Frameworks. Data &38; Policy 2023, 5, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatos, I.; Peliova, J.; Isaja, M.; Saja, K.; Gupta, S. Monetizing Data in International Data Spaces: Business Concepts and Technical Enablers. White paper, FAME Horizon Project (Horizon Europe), 2024. FAME Project No. 101092639; published September 2024; accessed 2025-06-11.

- Cai, L.; Zhu, Y. The Challenges of Data Quality and Data Quality Assessment in the Big Data Era. Data Science Journal 2015, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braud, A.; Fromentoux, G.; Radier, B.; Le Grand, O. The road to European digital sovereignty with Gaia-X and IDSA. IEEE network 2021, 35, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Data Spaces Association. Data Spaces Business Models, 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-10.

- Fruhwirth, M.; Pammer-Schindler, V.; Thalmann, S. Knowledge leaks in data-driven business models? Exploring different types of knowledge risks and protection measures. Schmalenbach Journal of Business Research 2024, 76, 357–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessler, J.; Cencic, M.R.; Metzner, C.; Wieker, H.; Lindow, K.; Schulz, W.H. Business models and organizational roles of data spaces: A framework for sustainable value creation. Data in Brief 2025, p. 111795.

- Kembügler, J. 4 – Business. Starter Kit for Data Space Designers, Data Spaces Support Centre, 2024. Last updated November 1, 2024; accessed June 11, 2025.

- VDMA. Cross-sectoral data space federation for the manufacturing industry. https://www.vdma.eu/en/viewer/-/v2article/render/88879018, 2025. Accessed: YYYY-MM-DD.

- Nicoletti, B. Supply Network 5.0 Sustainability. In Supply Network 5.0: How to Improve Human Automation in the Supply Chain; Springer, 2023; pp. 139–189.

- UNDERPIN Consortium. UNDERPIN: Pan-European Data Space for Holistic Asset Management in Critical Manufacturing Industries. https://underpinproject.eu/, 2023. Accessed: 2025-10-01.

- Weissenfeld, A.; Vanerio, J.; Wachsenegger, A.; Graser, A.; Garos, A.; Visvardi, S.; Ntafalias, A.; Casas, P. Proactive fault detection in wind turbine generators using SCADA measurements. In Proceedings of the 15th Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM 2025), 2025, Vol. 2025, pp. 128–133. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. CERRA sub-daily regional reanalysis data for Europe on single levels, 2024. Accessed: 2025-09-28.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).