1. Introduction

The global surge in electronic waste (e-waste) highlights both environmental risk and an opportunity for sustainable innovation. Replay Engineering is introduced as an interdisciplinary framework that redefines waste as a strategic resource through the integration of AI, IoT, blockchain, and predictive analytics. It targets circularity, cli-mate resilience, and equitable redistribution, particularly for under-resourced com-munities such as those in parts of Africa. This study analyzes diverse global case studies from e-waste management and construction reuse to second-hand vehicle re-manufacturing and evaluates environmental and economic benefits through lifecycle assessment (LCA) and AI-based performance modeling [

1,

2].

Recent studies point to inefficiencies in conventional recycling models, including high energy use and low recovery rates [

1]. Replay Engineering addresses these gaps by incorporating AI-driven waste sorting and decentralized blockchain-based traceability [

3]. Predictive analytics are used to optimize material flows, while smart logistics en-hance operational efficiency [

2,

4].

Moreover, the global economy remains predominantly linear, contributing to excessive waste generation and ecological degradation. Replay Engineering proposes a paradigm shift by utilizing smart technology for accurate classification, targeted re-manufacturing, and strategic resource redistribution. It goes beyond waste reduction, creating regenerative, closed-loop systems aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Conventional recycling models often suffer from inefficiencies such as high energy consumption, fragmented processing, and limited material recovery [

1]. Replay Engineering addresses these challenges by leveraging artificial intelligence (AI), block-chain, and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies to create adaptive, circular resource systems [

3]. AI enables precision sorting and classification, while blockchain ensures transparency and accountability throughout the material lifecycle [

4].

Replay Engineering redefines waste as a resource, fostering a paradigm shift to-ward decentralized, tech-enabled sustainability. This study establishes a theoretical and practical foundation for Replay Engineering, demonstrating its capacity to drive environmental, social, and economic transformation across multiple sectors.

This theoretical foundation is reinforced through a cross-national review of e-waste management systems. In China, a large portion of e-waste flows through in-formal sectors, creating significant environmental and public health risks, despite the existence of national EPR systems [

5]. In contrast, Switzerland operates a fully formalized EPR-based model with high recovery rates and low environmental impact, while India still relies heavily on informal processing with limited regulation or worker protection [

6]. African nations like Ghana receive large volumes of second-hand electronics, with economic benefits for local workers but at the cost of pollution, health hazards, and social exploitation [

7]. The U.S. represents a fragmented policy landscape, where consumer convenience, social norms, and logistics infrastructure critically influence recycling participation [

8]. These global examples illustrate the diverse challenges Replay Engineering aims to resolve by merging formal oversight, grassroots in-novation, and emerging technologies.

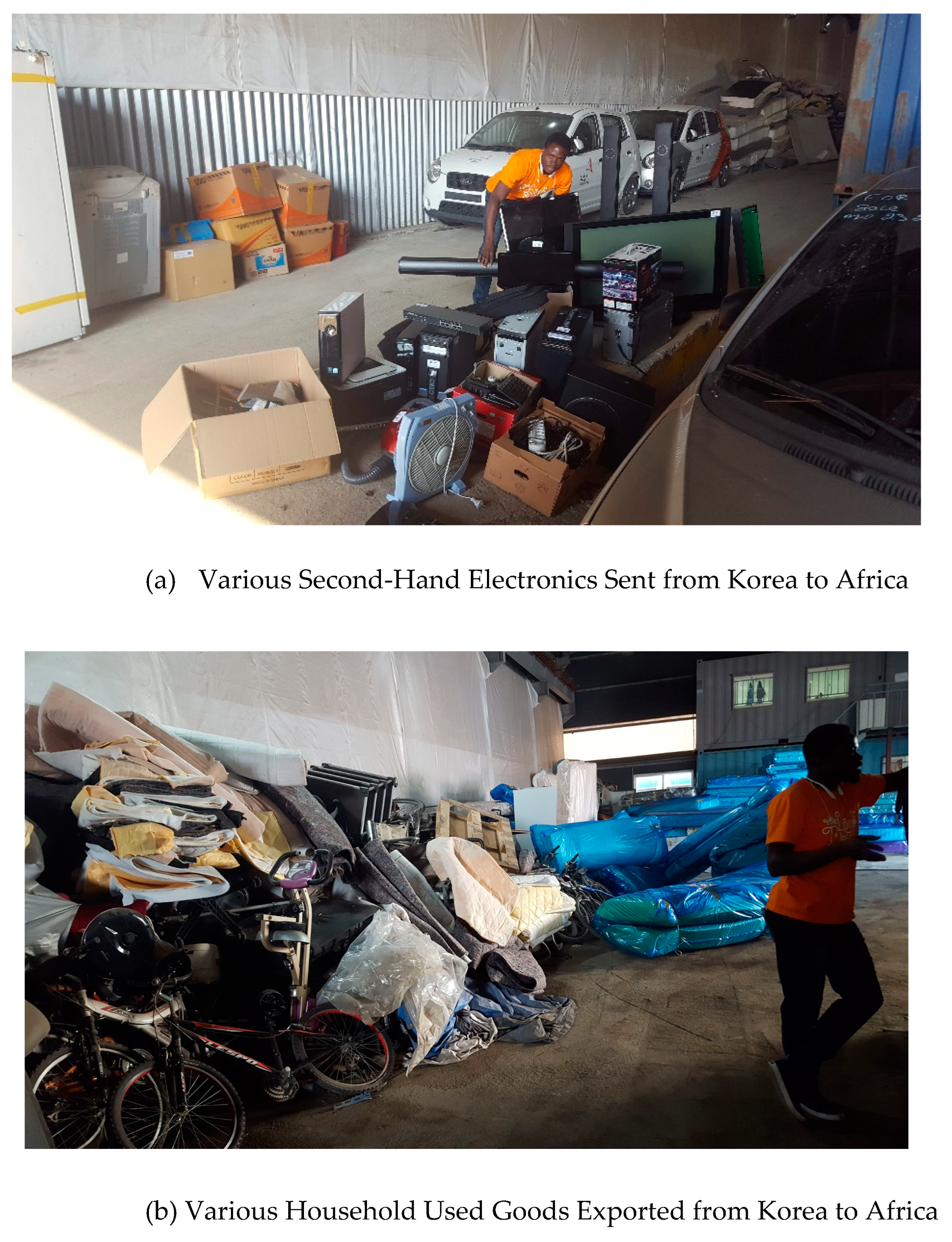

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of second-hand electronic goods exported from South Korea to Africa, demonstrating the practical execution of Replay Engineering’s redistribution strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

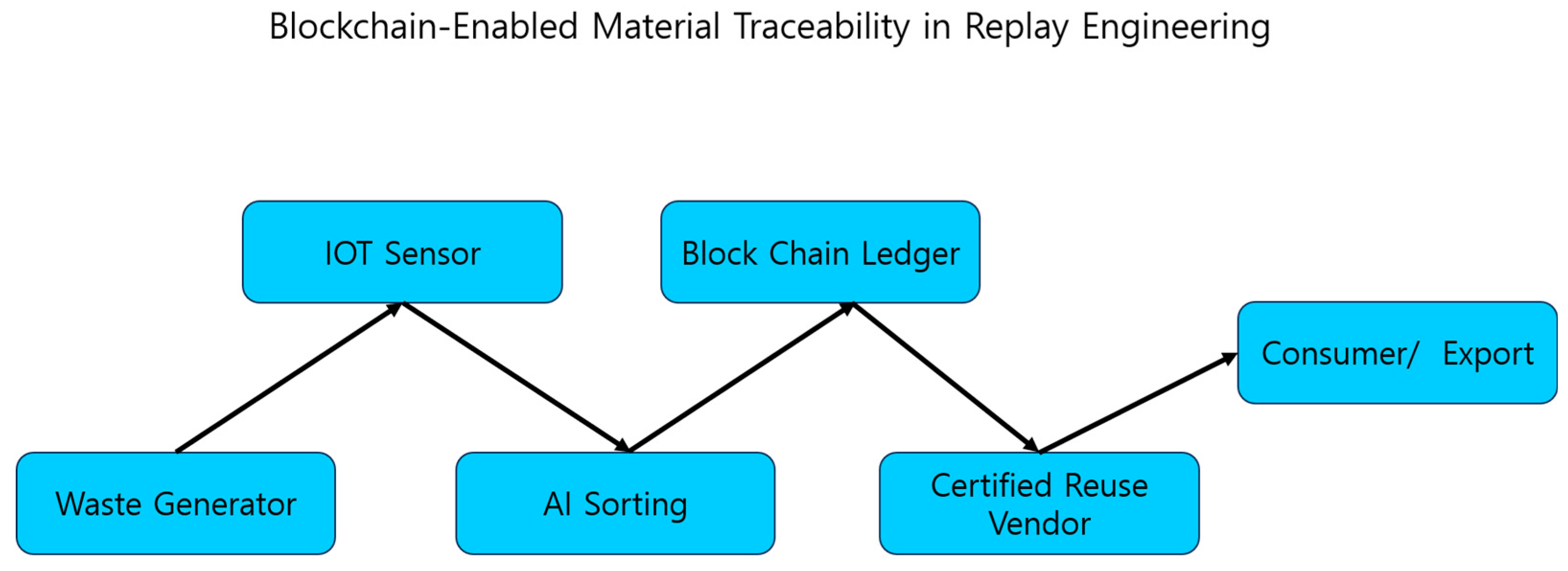

Unlike conventional recycling models, Replay Engineering integrates artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. Machine learning algorithms such as ResNet and SVM are used to enhance classification accuracy, while blockchain provides transparent resource tracking and prevents fraud in secondary resource markets [

5].

This research adopts a mixed-method approach, combining case study analysis and data-driven simulation. Lifecycle assessment (LCA) was conducted using OpenLCA software developed by GreenDelta GmbH (Berlin, Germany) to quantify the environmental impact across all stages of a product's life—ranging from raw material extraction, production, and use to disposal or recycling [

6].

Waste material image datasets were used to train ResNet, CNN, and SVM models to evaluate applicability in urban waste sorting facilities. According to DeepWaste [

9], these deep learning-based classification models significantly enhance material identification accuracy and resource recovery potential. ROI analysis and market growth projections were developed using cost-benefit data from industrial reports and real-world circular economy pilot programs, validated using insights from McKinsey Global Institute [

10].

Policy alignment was assessed by mapping Replay Engineering strategies against the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goals 12 and 13. The environmental impact of logistics optimization is supported by literature on green logistics practices [

11].

2.1. Expanded Case Studies

2.1.1. Automotive Refurbishment Industry

Japan and South Korea export over 3 million used cars annually to developing nations [

12]. Replay Engineering applies AI-based defect detection and predictive maintenance to extend vehicle lifecycles, reducing waste and increasing energy efficiency. Studies indicate that remanufacturing engines saves 60% of energy and 70% of raw materials compared to new production [

13]. The export of used vehicles from developed to developing countries raises environmental concerns [

14]. Replay Engineering enhances material efficiency in remanufacturing through AI-driven failure detection and defect prevention [

15]. Lifecycle analysis (LCA) shows that AI-based sorting reduces waste by 30%, making remanufactured vehicles a sustainable alternative [

16].

The global used car market, particularly in developing countries such as Pakistan and African nations, depends heavily on vehicle refurbishment. Japan and South Korea export millions of used cars annually, which are disassembled, refurbished, and rebuilt with new and used components. Replay Engineering enhances this process through AI-based defect detection and predictive maintenance systems, reducing waste and maximizing vehicle lifecycles.

Figure 2 shows disassembled vehicles being prepared for export to Africa, supporting the remanufacturing model central to Replay Engineering.

The export of disassembled vehicles supports Replay Engineering’s automotive remanufacturing strategy, which enhances lifecycle extension and circularity in developing regions.

2.1.2. Disaster Relief and Resource Redistribution

Replay Engineering can be applied to disaster-stricken areas to optimize the redistribution of emergency resources. In Ukraine, Gaza, and Turkey (earthquake zones), AI-driven logistics systems help repurpose surplus construction materials, medical equipment, and food supplies. Blockchain-based tracking ensures transparency and equitable distribution.

2.1.3. AI and Blockchain in Circular Supply Chains

Machine Learning models, including ResNet, CNN, and SVM, are used to classify recyclable materials with 90% accuracy [

17]. Predictive analytics forecast supply chain inefficiencies, optimizing logistics in circular economy systems. Blockchain technology is integrated to maintain immutable records of material transactions, improving accountability and reducing fraud in the secondary materials market [

2].

2.1.4. Quantitative Impact Assessment

Carbon Footprint Reduction: Lifecycle Assessment (LCA), a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life—from raw material extraction, production, and use, to disposal or recycling, analysis estimates that implementing Replay Engineering could reduce CO₂ emissions by 30–45% compared to traditional recycling [

5].

Economic Viability: ROI projections indicate that companies adopting Replay Engineering frameworks could lower operational costs by 20% through optimized material reuse and reduced disposal fees [

18].

Market Forecast: The global refurbished goods industry is expected to grow from

$110 billion in 2025 to

$180 billion by 2030, driven by sustainable consumption trends and AI-powered resource optimization [

19].

2.1.5. Policy Integration and ESG Considerations

Replay Engineering aligns with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and Goal 13 (Climate Action). The European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) provides policy incentives for companies adopting AI-driven waste management solutions, positioning Replay Engineering as a strategic fit for ESG-driven investments [

16].

Figure 3 captures the shipment of scrap bicycles from Korea to Africa, exemplifying Replay Engineering’s inclusive mobility and sustainability efforts.

3. Results

This section presents the findings based on the methodology above. A systematic literature review and case study analysis were conducted to evaluate CO₂ reduction, material recovery, and cost savings. Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) using OpenLCA quantified emissions across product lifecycles, consistent with approaches from Kaya [

19].

Machine learning models—ResNet, CNN, and SVM—trained on waste datasets, demonstrated classification accuracies exceeding 90% in municipal waste applications [

17].

A comparative ROI analysis used market data from South Korea and Africa. Growth projections were benchmarked against McKinsey’s global forecast [

10].

Policy alignment was confirmed through comparison with CEAP and SDGs. Green logistics practices support Replay Engineering’s potential to reduce emissions and improve system efficiency [

11].

To generate the results presented in this study, a multi-step methodological framework was applied. First, a systematic review of international literature and case studies was conducted to assess performance metrics such as CO₂ reduction, material recovery, and cost savings associated with Replay Engineering implementations. Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) Open LCA (GreenDelta GmbH, Berlin, Germany) a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life—from raw material extraction, production, and use, to disposal or recycling, tools were used to estimate environmental impacts, particularly carbon emissions, based on both primary case data and simulation models [

5].

Machine learning algorithms—specifically ResNet, CNN, and SVM—were trained using annotated datasets of waste material images to simulate classification accuracy in urban sorting centers. These models achieved an average classification accuracy exceeding 90% [

17], supporting claims in

Section 3.2 regarding material recovery efficiency.

To evaluate economic viability, a comparative ROI analysis was performed using cost and revenue data from industry reports and circular economy pilot programs in South Korea and Africa [

18,

19]. Forecast models were developed to project market growth in refurbished goods, validated against industry trend data and McKinsey Global Institute projections.

Replay Engineering's policy alignment was assessed through content analysis of the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), linking Replay Engineering contributions to Goals 12 and 13 [

16]. The methodology thus integrates environmental modeling, machine learning validation, economic forecasting, and policy alignment assessment to support the findings presented below.

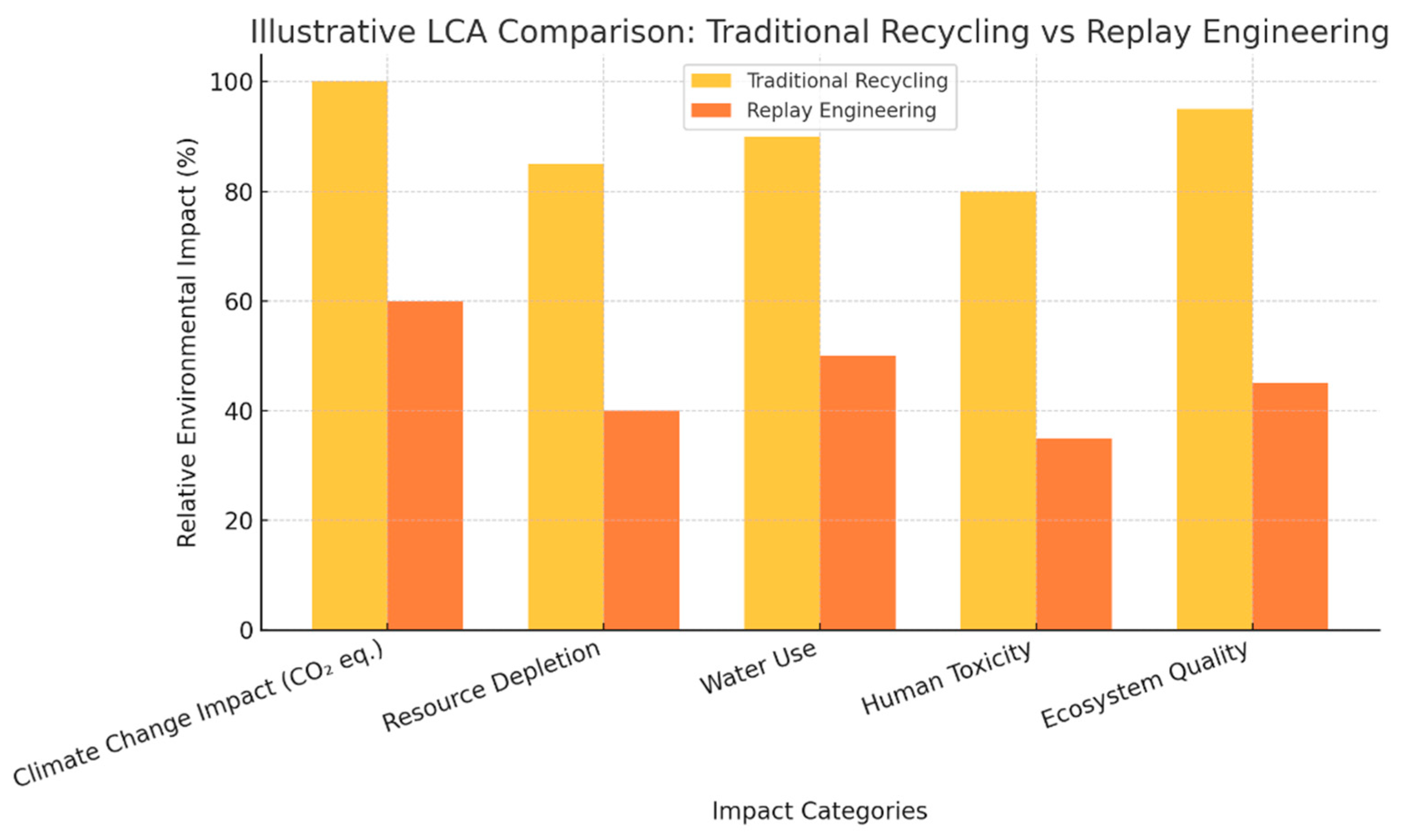

Figure 4.

Illustrative LCA Comparison: Traditional Recycling vs Replay Engineering.

Figure 4.

Illustrative LCA Comparison: Traditional Recycling vs Replay Engineering.

3.1. Carbon Footprint Reduction

Replay Engineering also improves the energy efficiency of remanufactured vehicles, which can save up to 60% in energy use compared to new vehicle production [

5] [

20].

Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) models estimate that AI-driven waste sorting and remanufacturing reduce CO₂ emissions by 30–45% compared to traditional recycling [

12,

20]. End-of-life (EOL) vehicle refurbishment can save up to 25% in emissions compared to new car manufacturing [

21,

22]. Replay Engineering also optimizes global trade flows, reducing emissions from unnecessary long-haul waste disposal and curbing illegal dumping [

11].

3.2. Resource Efficiency

Construction material reuse through blockchain-enhanced traceability contributes significantly to resource recovery strategies [

11,

23]. Replay Engineering also facilitates rare earth metal recovery from e-waste with up to 70% efficiency [

6,

23], and supports reductions in raw material dependency through intelligent remanufacturing systems [

23].

AI-based sorting systems increase material recovery rates by 40%[

7], reducing dependency on virgin resources [

18,

24]. E-waste refurbishment allows for 60–70% recovery of valuable rare-earth metals, decreasing reliance on environmentally harmful mining operations. In the automotive sector, remanufacturing components such as engines and transmissions saves 60% of energy and 70% of raw materials, as verified through LCA modeling [

25].

3.3. Economic Viability

Companies adopting Replay Engineering frameworks report a 20% reduction in operational costs due to optimized material reuse and lower disposal fees [

24]. Reverse logistics in automotive recycling has become increasingly profitable, particularly in Asia and Europe, where a

$200 billion circular vehicle parts market is projected by 2035 [

24]. Additionally, blockchain-based tracking reduces fraud in secondary markets and builds investor confidence in remanufactured goods.

3.4. Industry Applications

3.4.1. Electronic Waste (E-Waste) Management

AI-based automated sorting repurposes end-of-life electronics, maximizing component reuse and resale value. Blockchain integration prevents illegal e-waste dumping and supports compliance with ethical recycling standards.

3.4.2. Construction Material Reuse

Blockchain-powered traceability of demolition materials enables sustainable reuse in urban development. Smart contracts ensure accountability, thereby reducing emissions from construction waste.[

11]

3.4.3. Fashion and Textile Industry

Closed-loop fiber recycling systems prolong textile lifecycles by integrating IoT-enabled digital tracking. AI-powered quality assessment improves textile reuse efficiency.

3.4.4. Smart Circular Cities

Real-time AI-based waste management reduces landfill dependency by up to 40%. IoT and blockchain technologies enable decentralized waste-to-energy conversion programs in urban areas.

3.5. Comparison of Traditional Recycling and Replay Engineering

Table 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of conventional recycling systems and the Replay Engineering framework across key dimensions. It highlights how Replay Engineering advances beyond traditional waste reduction by integrating advanced technologies and circular economy principles to achieve greater efficiency, transparency, and sustainability.

Figure 5. this diagram presents the flow of Replay Engineering’s blockchain-enabled circular resource system. It starts from waste generation, followed by real-time data collection through IoT sensors, and material classification using AI sorting algorithms. Verified data is logged into a blockchain ledger to ensure traceability, security, and accountability. Materials then move to certified reuse vendors, who repurpose components or goods before final redistribution to consumers or export markets. This system prevents fraud, ensures compliance, and supports global sustainability goals.

4. Discussion

Replay Engineering has demonstrated promising environmental, economic, and technological impacts through its integration of AI, IoT, and blockchain into recycling and resource circulation systems. Its alignment with global climate objectives—such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement—positions it as a viable contributor to long-term climate change mitigation strategies. By reimagining waste as a resource and optimizing supply chains, Replay Engineering has the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and material extraction at scale.

To ensure widespread adoption, a strong policy framework is necessary. Governments should provide regulatory incentives, such as tax credits for circular technologies, and establish standards for AI-based recycling systems and blockchain material traceability. Collaborative initiatives between industry, academia, and municipalities will also accelerate implementation and increase trust in Replay-based systems.

Looking forward, future research should refine AI-driven waste prediction models and extend Replay Engineering applications to diverse sectors, including food waste, construction, and textiles. Blockchain can further enhance transparency in global circular supply chains, reducing fraud in secondary markets and improving investor confidence. Moreover, understanding consumer behavior will be key to encouraging mass participation in Replay Engineering ecosystems. This area can be further supported by behavioral economics research focused on circular economy adoption patterns [

16]. Behavioral economics approaches can inform incentive models to increase public engagement and drive systemic change.

Overall, the Replay Engineering framework offers a scalable, adaptable, and impactful pathway toward sustainable development and climate resilience.

5. Conclusions

This study has established Replay Engineering as a robust, interdisciplinary solution for addressing the environmental, social, and economic inefficiencies of conventional recycling systems. By integrating advanced technologies such as AI, machine learning, IoT, and blockchain, Replay Engineering redefines waste as a strategic re-source and offers a scalable framework for circularity and climate resilience.

Key findings demonstrate that Replay Engineering can reduce CO₂ emissions by up to 45%, increase material recovery by 40%, and deliver up to 20% cost savings for organizations through smart resource management. These outcomes are supported by quantitative lifecycle assessments (LCA), case studies, and predictive modeling using tools like openLCA.

Replay Engineering not only contributes to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), but also offers practical pathways to improve disaster recovery logistics, resource redistribution in vulnerable communities, and supply chain transparency.

As global consumption continues to grow and environmental pressures intensify, Replay Engineering offers a transformative, tech-driven model that combines economic viability with social equity and environmental regeneration. Future work should focus on pilot implementations, AI-driven behavioral incentive systems, and institutional partnerships to mainstream this approach globally.

Ultimately, Replay Engineering offers not only a technical solution but also a socio-environmental vision for the future of sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.K.; methodology, T.K.K.; software, T.K.K.; validation, T.K.K.; formal analysis, T.K.K.; investigation, T.K.K.; resources, T.K.K.; data curation, T.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K.K.; visualization, T.K.K.; supervision, T.K.K.; project administration, T.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge [Institution/Individuals] for their contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, K.; Schnoor, J.L.; Zeng, E.Y. E-waste recycling: Where does it go from here? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 10861–10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Sarkis, J.; Shen, L. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Steenmans, K.; Steenmans, I. Blockchain technology for sustainable waste management. Front. Political Sci. 2020, 2, 590923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz Schneider, A.; Aanestad, M.; Carvalho, T.C. Exploring barriers in Brazil's e-waste system: A multiple-case study. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 1–21.

- Fu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, A.; & Jiang, G. E-waste recycling in China: a challenging field. 2018.

- Chi, X.; Streicher-Porte, M.; Wang, M.Y.; Reuter, M.A. Informal electronic waste recycling: A sector review. Waste Management 2011, 31, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha-Khetriwal, D.; Kraeuchi, P.; Schwaninger, M. E-waste recycling in Switzerland and India. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2005, 25, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.Y.; Schoenung, J.M. E-waste recycling: US infrastructure review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2005, 45, 368–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Y. DeepWaste: Applying deep learning to waste classification for a sustainable planet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.05960, 2021.

- Nguyen, H.; Stuchtey, M.; Zils, M. Remaking the industrial economy. McKinsey Quarterly 2014, 1, 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, N.; Thurston, M. Remanufacturing: A Key Enabler to Sustainable Product Systems. CIRP Life Cycle Eng. Conf. 2006.

- Kim, S.; Hur, Y. A Study on the Export Competitiveness of Used Cars in Korea. Journal of International Trade & Commerce 2023, 19, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chen, D.; Zhou, W.; Nasr, N.; Wang, T.; Hu, S.; Zhu, B. The effect of remanufacturing and direct reuse on resource productivity of China’s automotive production. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 194, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliuk, S.; et al. Resource efficiency and climate change. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.A. Life cycle assessment: Review and sustainability. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2013, 2, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; et al. E-waste classification via ML-assisted spectroscopy. Waste Management & Research 2024, 0734242X241248730.

- Ahmed MI, B.; Alotaibi, R.B.; Al-Qahtani, R.A.; Al-Qahtani, R.S.; Al-Hetela, S.S.; Al-Matar, K.A.; Krishnasamy, G. Deep learning approach to recyclable products classification: Towards sustainable waste management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, C.G.; et al. Determinants of e-waste recycling logistics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2016, 27, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M. Recovery of metals from e-waste via physical and chemical processes. Waste Management 2016, 57, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Stuchtey, M.; Zils, M. Remaking the industrial economy. McKinsey Quarterly 2014, 1, 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.M.; Keoleian, G.A. Value of remanufactured engines. J. Ind. Ecol. 2004, 8, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhilper, R. Remanufacturing: The Ultimate Form of Recycling. Fraunhofer IRB Verlag. 1998.

- Oyenuga, A.A.; et al. Upcycling ideas in construction & demolition waste. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Tech. 2017, 6, 4066–4079. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, S.; et al. Biological recovery of rare-earth elements. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 124596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H. Life cycle assessment–based comparative evaluation of originally manufactured and remanufactured diesel engines. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2014, 18, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).