1. Introduction

Infertility affects approximately 15 % of couples worldwide, with male factors implicated in about 40–50 % of cases either alone or in conjunction with female factors [

1,

2,

3].For many decades, male infertility was under-recognized due to limited diagnostic tools, social stigma, and a predominant focus on female reproductive health. However, improvements in semen analysis, molecular diagnostics, and large-scale epidemiological studies over the past two decades have recalibrated our understanding of infertility as a shared burden, with male contributions playing a central role in reproductive outcomes [

3].

In parallel, climate records and reanalysis products document a marked rise in the frequency, duration, and intensity of extreme heat events globally, including a sharply increasing number of days with air temperatures exceeding 33 °C, particularly across equatorial, subtropical, and densely urbanised regions [

4,

5]. Urban Heat Islands further amplify local maxima, often pushing ambient temperatures several degrees above regional climatic means. Increased exposure to such heat is now measurable not only in terms of calendar days but also in terms of population-weighted “person-days” of heat exposure, which have surged in the twenty-first century.

This convergence raises a compelling hypothesis: might the rising burden of ambient heat exposure, especially days exceeding the scrotal thermoregulatory threshold of about ~33-34 °C be a contributing driver of declining sperm quality and rising male infertility? Recent large, scale studies provide emerging support. A multi-center Chinese cohort of 33,234 men found a significant negative association between temperature anomalies during hot seasons and key semen parameters, including sperm concentration, progressive sperm count, and total motile sperm count [

6]. In addition, a recent review highlights the mechanistic plausibility of heat stress disrupting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in male adolescents and adults, including reductions in sex hormone synthesis and impaired spermatogenesis [

7].

Therefore, these trends, rising ambient heat exposure, heightened urbanisation, and the clearer emergence of male infertility in clinical and population studies, make the hypothesis of a heat-driven component of male infertility scientifically plausible. Further targeted research combining climate-health linkage analyses, mechanistic reproductive biology, and geospatial exposure assessments is warranted to ascertain the magnitude of this potential driver and guide appropriate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

In this article, we invistiage the emerging hypothesis that rising ambient air temperatures, driven by global climate change and amplified by urbanization, may represent a significant and underappreciated factor in the etiology of male infertility. Rather than providing definitive causal proof, our goal is to synthesize evidence across multiple domains, from thermophysiology and mechanistic biology to epidemiology and environmental exposure metrics, to propose a conceptual framework linking heat stress to impaired spermatogenesis. By doing so, we aim to stimulate further interdisciplinary research, refine experimental approaches, and encourage the integration of climate variables into reproductive health policy and clinical practice.

2. Thermoregulatory Physiology of the Scrotum: Heat Exposure and Male Fertility

2.1. Thermoregulatory Mechanisms and Spermatogenic Sensitivity

The anatomical placement of the testes within the scrotum, —away from the abdominal cavity, —is a fundamental biological adaptation that maintains testicular temperature roughly 2–4 °C below core body temperature (~37 °C) , a prerequisite for optimal spermatogenesis [

8] In humans, scrotal thermoregulation relies on several active and passive mechanisms, including the cremaster and dartos muscles adjusting testicular position, a counter-current vascular heat exchange in the spermatic cord, minimal insulating subcutaneous fat, and scrotal sweating or vasodilation of superficial blood vessels in warm conditions [

9,

10]

Spermatogenesis is most efficient at testicular temperatures of approximately 34–35 °C—a few degrees below core temperature. Elevation of scrotal temperature, even modestly, disrupts this finely tuned environment and impairs reproductive outcomes [

11,

12]. Heat stress, particularly when ambient air temperatures exceed the scrotal thermoregulatory threshold (~33–34 °C), can overwhelm physiological cooling mechanisms. In experimental and observational studies, sustained elevations in scrotal temperature have been linked to a series of adverse outcomes as follow:

First, sustained heat exposure causes increased spermatogenic cell apoptosis and reduced germ cell survival, especially during the sensitive meiotic and spermiogenic phases [

4]. This is accompanied by disruption of Sertoli cell function and the blood–testis barrier, leading to impaired support of developing germ cells and reduced spermatid maturation [

8]. Second, heat stress induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in spermatozoa, with decreased ATP production, reduced membrane potential, and impaired motility [

12]. These cellular disturbances also produce abnormal sperm morphology and structural defects, often attributable to disrupted cytoskeletal formation, heat-induced disruption of protein folding, and altered gene expression during spermiogenesis [

12,

13] . Additionally, elevated temperatures increase sperm DNA fragmentation and chromosomal abnormalities, stemming from meiotic failure, impaired recombination, and reduced efficacy of DNA repair processes [

12,

14]. Animal models further underscore this vulnerability. High ambient temperature in seasonal heat-stress studies (e.g., Angora rabbits) induces massive transcriptomic changes in testicular tissue, morphological damage to seminiferous tubules, and prolonged recovery periods for normal spermatogenesis [

15]. Additionally, testicular heat stress interventions in rodent models show that recovery of normal germ cell cycles may take multiple months, and repeated or chronic heat exposure can lead to persistent fertility impairment. In summary, the physiology indicates that prolonged exposure to ambient heat above the scrotal cooling threshold is not merely a nuisance but a potent, direct stressor on male fertility. In the context of climate-driven increases in high-temperature days, especially in urbanized or equatorial settings, this raises a plausible mechanistic link between environmental heat exposure and the observed global trends in declining male reproductive health.

2.2. Molecular Mechanisms: Temperature-Sensitive Reproductive Proteins (TSGA10)

TSGA10 (Testis Specific Gene 10) encodes a 698-amino acid protein that serves as a fundamental component in male reproductive biology [

16]. During post-translational processing, TSGA10 undergoes proteolytic cleavage, generating two functionally distinct domains: an N-terminal component (27-kDa) and a C-terminal component (55-kDa). This dual-domain architecture enables the protein to perform multiple cellular functions across different stages of spermatogenesis [

17].

Subcellular localization studies reveal TSGA10’s strategic positioning within sperm architecture. The protein demonstrates primary localization to the sperm tail region, where it functions as an integral component of the fibrous sheath, —a specialized cytoskeletal structure essential for flagellar motility and energy transfer. Additionally, TSGA10 exhibits perinuclear localization patterns, positioning it at the critical interface between nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments [

17].

The temporal and spatial expression profile of TSGA10 throughout spermatogenesis indicates its involvement in multiple cellular processes fundamental to male fertility. These include active cell division during mitotic proliferation of spermatogonia, cellular differentiation during meiotic progression, and directed migration of developing spermatids. This multifaceted role positions TSGA10 as a molecular coordinator of sperm development and function. Recent studies show TSGA10’s critical role extends beyond structural functions to encompass mitochondrial bioenergetics through its direct interaction with cytochrome c1 (CytC1) in mitochondrial Complex III. This interaction optimizes electron transport efficiency while minimizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and heat generation during ATP synthesis. Under thermal stress, TSGA10’s compromised function leads to mitochondrial uncoupling, resulting in electron leakage, excessive ROS accumulation, and increased heat production, —creating a destructive feedback loop that further impairs reproductive function [

18,

19,

20].

2.3. Climate Change and Biological Systems

Rising global temperatures have demonstrated profound effects on biological systems across multiple scales. From coral bleaching events to shifts in species migration patterns, temperature sensitivity appears to be a fundamental constraint on biological function. Recent work on the analysis and interpretation of critical temperatures demonstrates that organisms exhibit temperature thresholds, —quantified as critical thermal maxima (CTmax) and minima, —beyond which failure rates sharply increase, and essential biological processes begin to collapse. Male fertility, in particular, has long been recognized as temperature-sensitive. The evolution of external testes in mammals reflects this sensitivity, maintaining sperm production at temperatures 2-3 °C below core body temperature. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this sensitivity, particularly the role of specific proteins like TSGA10, remain poorly understood.

2.4. Impact of Temperature on Fertility

Heat exposure impairs reproductive health primarily through biological disruption, especially male spermatogenesis, rather than reduced sexual activity [

21] . Proteins like TSGA10, which are highly expressed in sperm, play dual roles in structuring mitochondria for ATP generation and contributing to thermogenesis. Elevated temperatures destabilize such proteins, compromising sperm energy metabolism and motility, thus reducing fertility. Empirical evidence supports these mechanisms globally. Ref. [

22] found that heat exposure lowers conception rates in Hungary, forecasting a 1% annual decline by 2050 due to climate-driven pregnancy loss. In South Korea, ref. [

23] reported reduced births nine months after heatwaves, confirming a biological rather than socioeconomic effect. Similarly, ref. [

24] showed that extreme heat in the U.S. shortens pregnancies, causing over 150,000 lost gestational days annually, disproportionately affecting Black mothers. A global meta-analysis of 198 studies [

25] confirmed that each 1°C rise increases preterm birth risk by 4%, with heatwaves raising it by 26%, alongside heightened risks for stillbirth and congenital anomalies.

Cold exposure can also threaten pregnancy outcomes. Ref. [

26] found that cold spells in China increased preterm births by up to 18%, particularly late-stage spontaneous cases. Earlier, ref. [

22] identified a 0.52% rise in early embryonic loss linked to post-conception heat exposure in 6.5 million Hungarian pregnancies, the first causal evidence that heat elevates embryo mortality.

At the individual level, ref. [

27] found that cumulative male heat exposures (e.g., hot baths, fever) reduced fecundability, especially in men over 30. From a global perspective, ref. [

28] reported a U-shaped relationship between ambient temperature and female infertility across 174 countries, with lowest risk near 15°C; both heat and cold deviations elevated infertility rates.

Mechanistically, heat stress induces oxidative damage, microbial imbalance, and disrupted testicular metabolism [

29] , impairing spermatogenesis and increasing DNA fragmentation [

30,

31]. For females, heat compromises ovarian function, oocyte quality, placental blood flow, and fetal development [

30,

32], consistent with findings in animal models where heat stress drastically lowers fertility [

33].

Beyond biology, refs. [

34,

35] highlight socioeconomic amplifiers—climate-induced fertility reductions in industrialized nations and divergent demographic pressures in low-income regions. As [

36] emphasize, reproductive decline at sublethal temperatures may be the most immediate threat climate change poses to biodiversity and human population stability.

Diverse evidence from physiological, epidemiological, and ecological data converges on a clear conclusion: rising global temperatures pose a pervasive threat to reproductive health, operating through oxidative, endocrine, and developmental pathways that span from sperm function to fetal survival. Climate change thus represents not only an environmental and public health emergency but also a profound reproductive crisis with lasting demographic and evolutionary implications.

2.5. Climate Change and the Expansion of Extreme Heat

In the 1950s the world population was roughly 2.5–2.6 billion, and days with very high ambient temperatures (e.g., >33 °C) were largely confined to deserts, some equatorial savannas, and brief seasonal extremes; most temperate and humid tropical rainforest zones experienced relatively few prolonged episodes above that threshold [

37]. World Population Prospects Crucially, instrumental and reanalysis records show that the frequency, intensity and seasonal length of hot extremes have increased since the mid-20th century, with heatwave days and extreme-temperature events becoming substantially more common across most land areas—a trend that is robustly documented in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment [

38].

By the 2010s–2020s, the global population had grown to about 8 billion, concentrating many more people in regions that are already climate hotspots. Population growth, urbanization and the rapid expansion of cities amplify exposure: city populations are larger and often experience local warming above regional background (the Urban Heat Island effect), which observational and review studies show can increase urban temperatures by several degrees relative to nearby rural areas (typical nighttime UHI intensities of a few °C and local peaks that exceed +3–6 °C in some cases). These urban increments act on top of the background climate warming and materially increase the number of days and nights when ambient air temperatures exceed physiologically important thresholds [

39].

The combination of climate warming and population/geographic concentration yields far larger population-weighted exposures than changes in raw climate alone. For example, a global study that combined high-resolution daily temperature fields with longitudinal urban population data found urban person-days of exposure to extreme heat rose from 40 billion in 1983 to 119 billion in 2016 (a 199% increase), with most of the increase driven by both warming and urban population growth. This “person-days” metric makes clear that even moderate increases in the frequency of hot days can translate into very large increases in human heat exposure [

40].

Regionally, the effects are already extreme. South Asia, parts of the Middle East and North Africa, and some equatorial and subtropical African regions now routinely experience dozens to many hundreds of days per year at very high temperatures; analyses and public-health assessments (including UNICEF and climate-attribution studies) report that large cohorts,—hundreds of millions,— already face many weeks to months per year of conditions above labor- and health-risk thresholds (e.g., 30–35 °C daytime or wet-bulb thresholds in humid zones), and attribution work shows human-caused warming has made recent deadly heat events much more likely and intense.

Taken together, the mid-20

th-century baseline (low population, fewer hot-day exposures) and the present (

billion people, expanded urban areas, and a climate with far more frequent, longer, and more intense hot spells) create a situation where person-days above physiological thresholds (such as

) have increased several-fold. That multi-fold increase in population heat exposure is the proximate environmental change underlying hypotheses that chronic or repeated ambient heat stress could drive population-level impacts on heat-sensitive biological systems (including spermatogenesis) [

41].

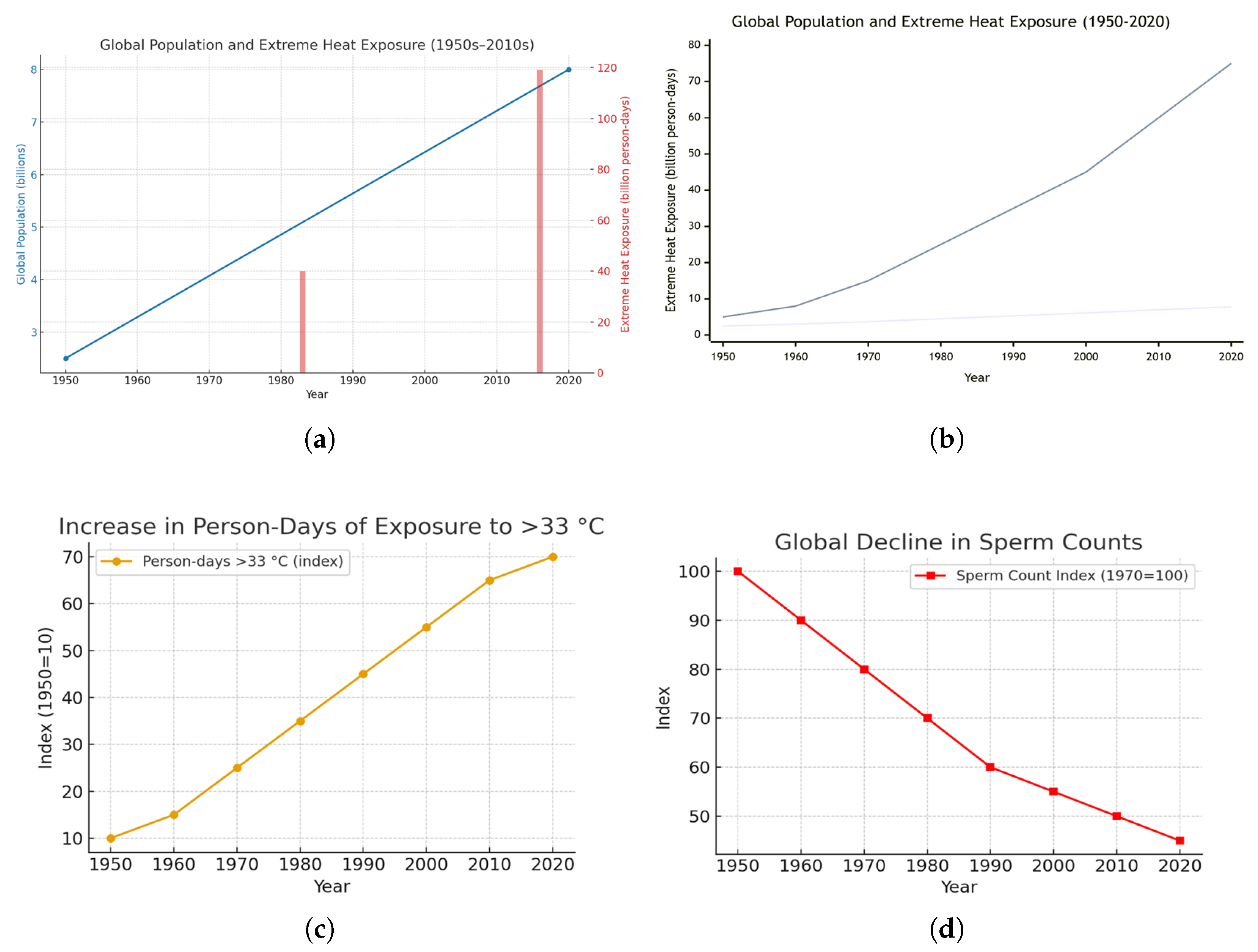

Figure 1 illustrates global population growth and the concurrent rise in population-weighted exposure to extreme heat, expressed as billions of person-days exceeding

. Panel (

a) shows the steady increase in global population from approximately 2.5 billion in 1950 to about 7.8 billion in 2020, based on UN DESA (2023) estimates. Panel (

b) demonstrates that, over the same period, exposure to extreme heat has accelerated sharply—particularly since the 1980s—reflecting the combined effects of population growth, rapid urbanization, and anthropogenic climate warming [

43,

44,

45]. Panel (

c) highlights that population exposure to ambient air temperatures above

has increased more than six-fold since the 1950s, far outpacing population growth alone and underscoring that global warming is the dominant driver of expanding heat-related risk.

Panel (

d) depicts the corresponding global decline in sperm counts from the 1970s to 2020s, indexed to 1970 = 100. These data are derived from a systematic review and meta-regression analysis aggregating 283 studies across 53 countries and more than 57,000 men, showing a significant and accelerating decline in sperm concentration (millions per mL), particularly after 2000 [

46].

Taken together, the panels illustrate a striking parallel between the intensification of global thermal exposure and the persistent decline in male reproductive health. Data sources include IPCC (2021), NOAA NCEI (2023), UN DESA (2022), and [

45], along with meta-analytic evidence from Levine

et al. ([

46],

Hum Reprod Update).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Fertility Data

We use Total Fertility Rate (TFR) data from the World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI) dataset for the period 1960–2023. The TFR is defined as the number of children a woman would bear if she experienced the age-specific fertility rates of a given year throughout her reproductive life [

47]. The indicator "Fertility rate, total (births per woman)" is compiled by the United Nations Population Division (World Population Prospects 2024 Revision) from national vital registration systems, censuses, and large-scale surveys. Where vital registration data were incomplete, model-based adjustments using demographic survey data were applied to ensure reliability. Fertility data were aggregated by continent (Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Arctic) using population-weighted means to align with global coverage.

3.2. Temperature Data

Temperature anomaly data were sourced from NOAA’s Global Surface Temperature Analysis (NOAAGlobalTemp) [

44]. We also used NASA’s GISTEMP v4 [

48] as a robustness check on global trends. GISTEMP v4 blends land-based records from the Global Historical Climatology Network-Monthly and ocean-based records from the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature. Anomalies were calculated relative to the 1951–1980 baseline, consistent with IPCC AR6 standards. Regional means for Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Arctic were extracted from NOAA’s Climate at a Glance interface, while global means were derived from NOAA and NASA combined datasets. These temperature records span 1850–present; annual means for 1960–2023 were used to align with the fertility data time frame.

3.3. Regional Aggregation

We analyzed both global and regional trends for four major regions: Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Arctic. Regional temperature anomalies are derived from NOAA’s area-weighted averages of gridded annual temperature anomalies, while fertility rates are aggregated using population weighting to capture each country’s relative demographic contribution. The Arctic region is defined as including countries with the majority of land area above 60°N latitude, following the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) classification.

3.4. Statistical Approach and Standardization

We examine the relationship between fertility and temperature anomalies using three complementary approaches: Pearson’s correlation, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, and lagged correlation analysis. We employ these methods to capture both immediate and delayed associations between temperature changes and fertility rates. We specify linear regression models as:

Linear regression models estimated the slope of fertility decline per increase in temperature anomaly, while locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) was used to visualize potential non-linear relationships. Statistical significance was assessed at . For each region, 95% confidence intervals were computed for correlation and regression estimates. Lagged correlations were tested at 1-, 2-, and 3-year intervals to assess the persistence of climate effects on fertility.

3.5. Data Standardization and Visualization

Because temperature and fertility have different scales and units, we standardize both series into zz z-scores to facilitate comparison across regions with differing baselines and variances. We calculate rolling five-year means to reduce interannual noise and highlight long-term trends. In our figures, we display both linear trends with 95% confidence bands and smoothed LOESS fits to visualize curvilinear components in the temperature–fertility association.

4. Results

4.1. Global Trends in Temperature and Fertility (1960–2023)

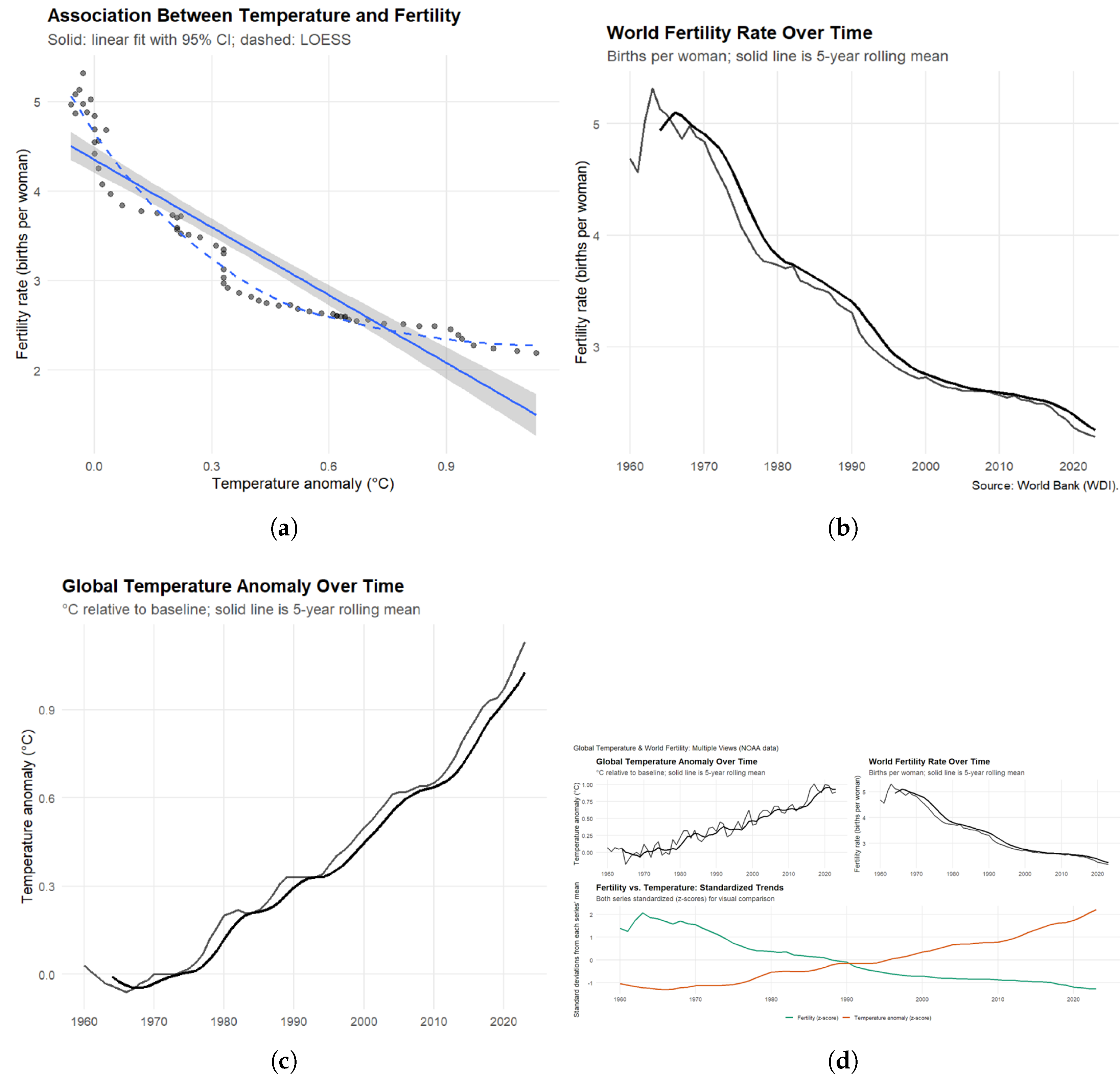

Figure 2 shows a strong negative association between global warming and reproductive outcomes. Mean global temperature increased by approximately

, while fertility rates fell by roughly half, from nearly five births per woman in the 1960s to just over two in recent years. We find a very strong correlation between temperature and fertility (

), explaining more than 80% of the variation in global fertility rates. Our lagged analyses confirm that this relationship persists across multiple years, indicating that climate effects on reproduction are lasting rather than short-term. Robustness checks using both NASA and NOAA datasets produce nearly identical results.

Rising temperatures and global warming may affect fertility through both direct physiological and indirect socioeconomic mechanisms. Physiologically, heat stress can impair sperm quality, disrupt ovulation, and increase pregnancy complications, thereby reducing reproductive success. Indirectly, climate-related economic strain, food insecurity, and migration may delay or limit family formation. The parallel timing of global fertility declines and accelerating anthropogenic warming suggests that climate change reinforces the broader demographic transition alongside education, urbanization, and economic development. If this pattern continues, it could alter population projections, labor force dynamics, and sustainability planning in the Anthropocene.

4.2. Arctic Region Temperature Anomalies and Fertility Rates (1960-2023)

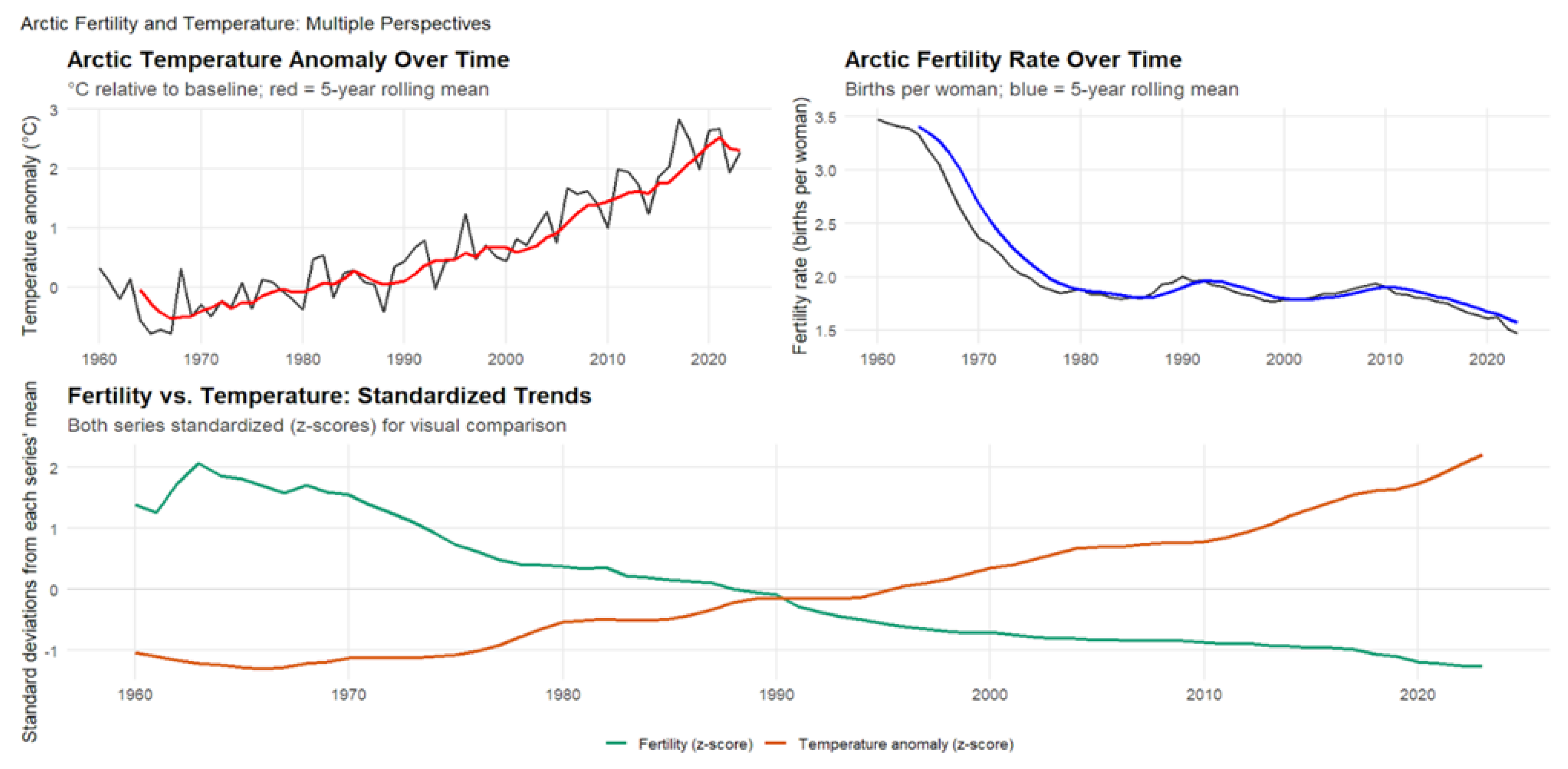

As shown in

Figure 3, temperature anomalies and fertility rates are strongly negatively correlated (

,

; 95% CI:

to

). Fertility declined by approximately 0.29 children per woman for each

increase in temperature anomaly (

,

). Arctic temperatures rose by roughly

, increasing at a rate of

per year, while fertility fell by about half, from 3.1 to 1.6 births per woman. Lagged correlations remained significant across one- to three-year lags (

), suggesting that warming exerts multi-year effects on reproductive outcomes rather than short-term fluctuations.

The consistency and strength of this association suggest that climate change may be contributing to fertility decline in high-latitude regions alongside socioeconomic modernization. Physiological stress induced by rising temperatures, disruption of traditional livelihoods, and increasing economic uncertainty may all contribute to reduced fertility. Given the Arctic’s rapid warming relative to global averages, these populations are especially vulnerable to climate-related demographic pressures. Combined with ongoing urbanization and migration, these dynamics could accelerate population decline and reshape settlement patterns across the region. Integrating climate projections with demographic models will be essential for anticipating population sustainability and informing adaptation strategies in the Arctic.

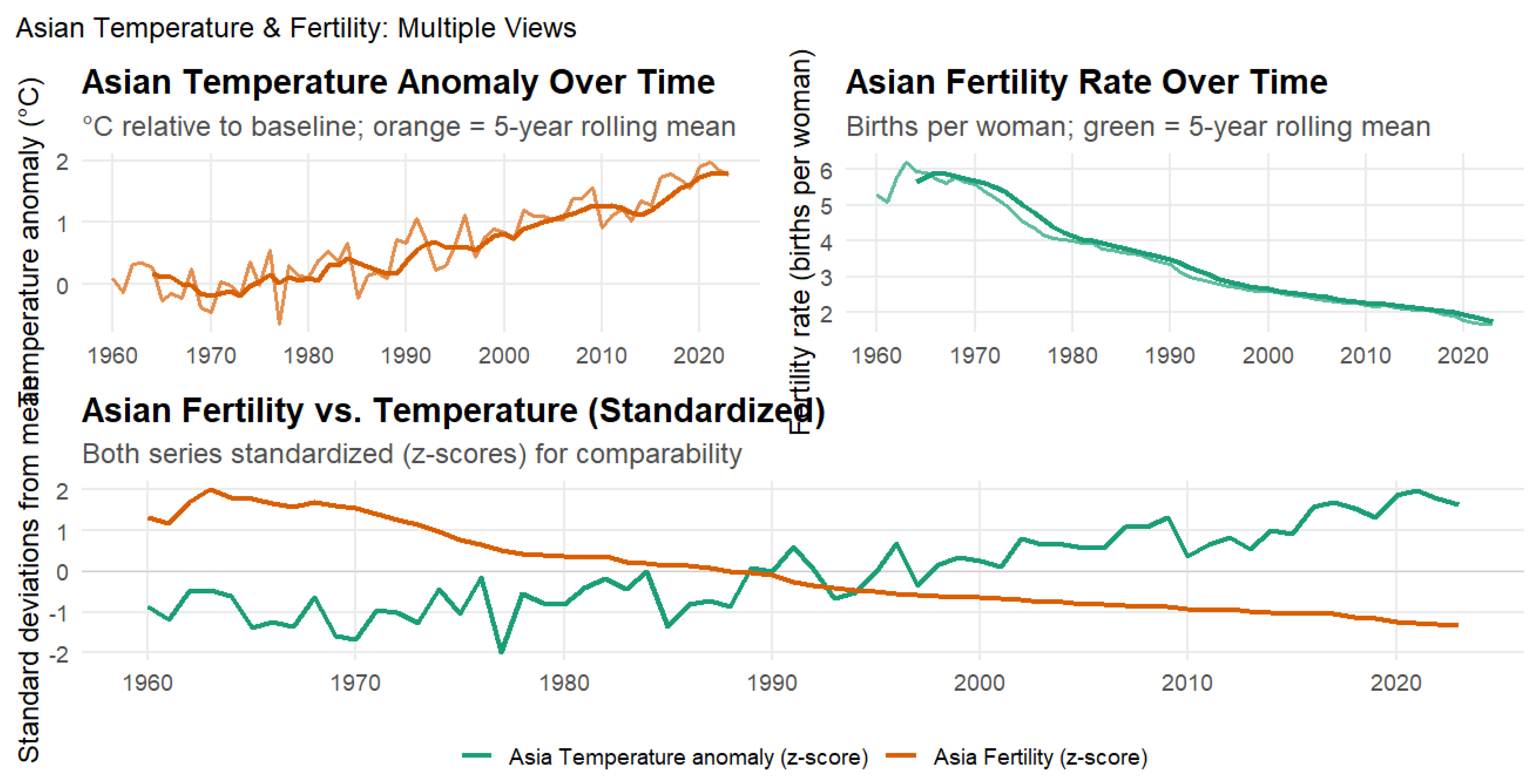

4.3. Asia Temperature Anomalies and Fertility Rates (1960-2023)

Figure 4 presents the relationship between temperature anomalies and fertility rates across Asia from 1960 to 2023. The analysis reveals a very strong negative correlation between regional warming and reproductive outcomes (

), explaining approximately 70% of the variance in fertility rates. This represents one of the strongest regional climate–fertility associations observed globally. The relationship remained robust over time, with lagged correlations persisting for up to three years (

for 1-, 2-, and 3-year lags, respectively), indicating that warming exerts prolonged rather than short-term effects on reproductive outcomes. The steady rise in temperature anomalies over six decades closely paralleled a sustained regional fertility decline, suggesting that climate change and demographic transition are progressing in tandem across Asia’s diverse economies.

The strength and persistence of this relationship have major implications for population dynamics in the world’s most populous continent. Asia’s high sensitivity to climate conditions likely reflects a combination of physiological, economic, and structural factors. Extreme heat exposure can directly affect reproductive health, while indirect pathways include reduced agricultural productivity, food insecurity, and delayed family formation caused by economic uncertainty. Many Asian societies are also undergoing rapid urbanization and modernization, processes that may amplify the demographic effects of environmental stress. The combination of rising temperatures, socioeconomic transition, and demographic aging could accelerate fertility decline in developing regions while deepening population challenges in countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea. These results underscore the need for integrated climate and demographic policies that consider both environmental and social dimensions of fertility change, as Asia’s climate–fertility dynamics will have far-reaching consequences for global population trends and sustainable development.

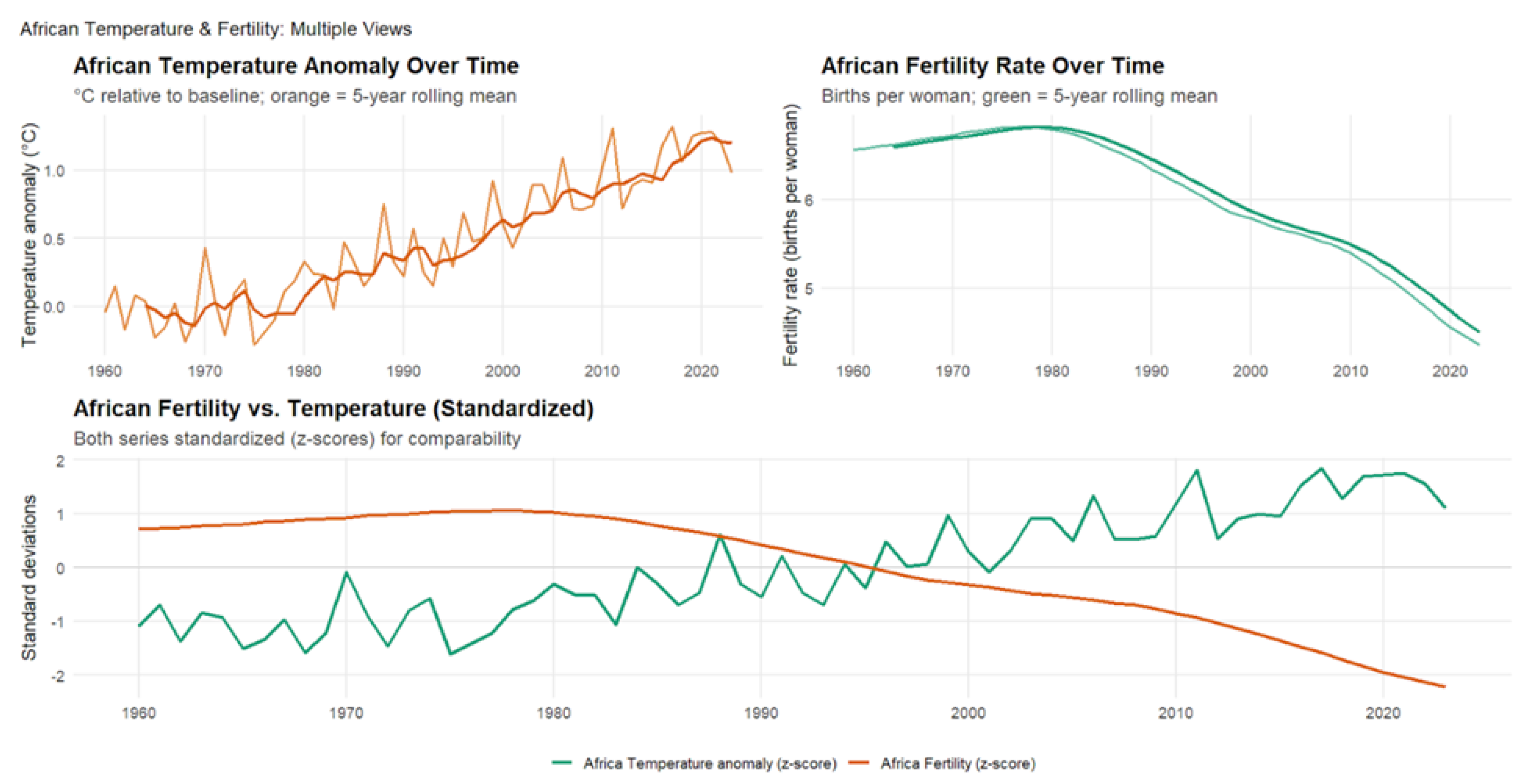

4.4. African Temperature Anomalies and Fertility Rates (1960-2023)

Figure 5 illustrates patterns consistent with those observed in other regions, showing the strongest negative correlation of all regional analyses from 1960 to 2023 (

). This relationship explains roughly 80% of the variance in fertility rates, indicating an exceptionally strong coupling between climatic and demographic change. Across the 64-year period, correlations remained highly stable and even intensified slightly over time, peaking at the two-year lag (

), suggesting that climatic impacts on fertility operate through multi-year processes rather than immediate effects. Africa’s rapid warming, coupled with pronounced fertility decline across several subregions, highlights the deep interconnection between environmental stress and demographic transition.

The exceptional strength of the climate-fertility relationship in Africa reflects both structural vulnerabilities and broader dynamics shared across the Global South. Many African societies remain heavily dependent on agriculture and other climate-sensitive livelihoods, where extreme heat, droughts, and erratic rainfall directly threaten economic stability, health, and family formation decisions. These populations face compounding disadvantages: limited adaptive capacity, inadequate healthcare and infrastructure, and restricted access to reproductive health services amplify climate impacts. Climate shocks often trigger cascading consequences, migration, food insecurity, and social disruption, that extend well beyond the initial event, leading to long-term demographic changes. As Africa is projected to drive more than half of global population growth by mid-century, these findings suggest that climate change could accelerate fertility transitions and reshape population structures across the continent. More broadly, they highlight how climate pressures may intensify existing inequalities between the Global North and South, making climate adaptation not only an environmental imperative but also a demographic and social one. Integrating reproductive health, gender equity, and climate resilience into development planning will be essential for ensuring sustainable population outcomes in a rapidly warming world.

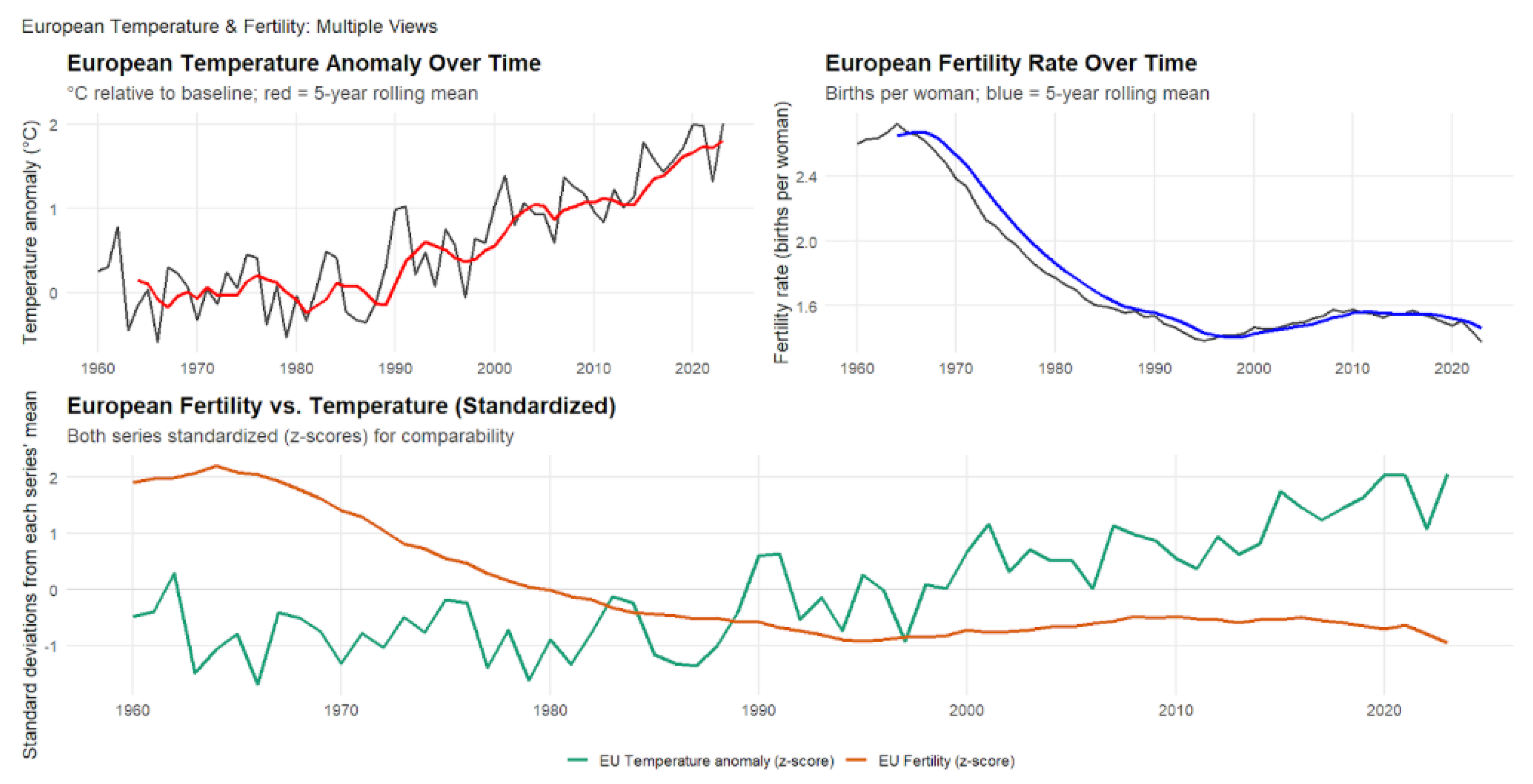

4.5. European Temperature Anomalies and Fertility Rates (1960-2023)

As shown in

Figure 6, European temperature anomalies and fertility rates from 1960 to 2023 exhibit a statistically significant negative correlation between regional warming and reproductive outcomes (

). Over this 64-year period, European temperatures increased by approximately

(

per year), while fertility rates declined from 2.6 to 1.4 births per woman—a reduction of roughly 1.2 children per woman. The steepest fertility declines occurred between the 1960s and 1980s, after which rates stabilized at sub-replacement levels despite continued warming. Lagged correlations remained consistently negative across one- to three-year intervals (

), indicating that climate effects on fertility persist across multiple years even in highly developed populations. However, this correlation is substantially weaker than that observed in African countries (

), likely reflecting Europe’s higher living standards, superior healthcare infrastructure, advanced social safety nets, and greater adaptive capacity to environmental stressors.

The European case provides important insight into how climate–demographic relationships operate in post-transitional societies. While Europe’s demographic transition was largely driven by socioeconomic development, expanding education, and increasing gender equality rather than direct climatic pressures, ongoing warming may be contributing to the persistence of low fertility and limiting recovery toward replacement levels. Several mechanisms could explain this relationship: physiological effects of heat stress on reproductive health, economic pressures associated with rising energy and adaptation costs, and heightened eco-anxiety influencing reproductive decisions and perceptions of future family stability. Unlike many populations in the Global South, Europe’s robust social welfare systems and healthcare infrastructure appear to mitigate the direct demographic consequences of climate change. Nevertheless, the persistent negative association suggests that even advanced economies are not immune to environmental influences on reproduction. As sub-replacement fertility converges with accelerated population aging, policymakers must increasingly consider how climate adaptation, immigration policy, and social welfare planning intersect with long-term demographic sustainability in an era of intensifying climate change.

5. Conclusion

Although correlation alone cannot establish causation, converging evidence from physiology, epidemiology, and climatology provides a strong and coherent case that rising ambient heat contributes meaningfully to declining fertility and male reproductive function. Across global and regional analyses, statistically significant negative correlations were observed between temperature anomalies and fertility rates, with the relationship strongest in Africa (), Asia (), and the Arctic (). These consistent patterns, together with persistent multi-year lag effects, suggest that heat exposure exerts sustained biological and social impacts on reproductive outcomes rather than short-term fluctuations. Physiological plausibility is well established: experimental and clinical studies demonstrate that scrotal temperatures above approximately impair spermatogenesis, inducing germ cell apoptosis, disrupting Sertoli cell function, and generating oxidative stress that compromises mitochondrial integrity and sperm motility. These mechanistic vulnerabilities mean that even modest increases in environmental temperature can translate into significant reproductive consequences, particularly in tropical and urban regions where ambient heat routinely exceeds physiological thresholds.

Epidemiological and social evidence reinforces these biological mechanisms. Meta-analyses document global declines in sperm count and motility, while occupational cohorts exposed to chronic heat (e.g., agricultural, manufacturing, and transportation workers) show higher rates of abnormal semen parameters. At the population level, the regions showing the strongest statistical correlations between temperature anomalies and fertility decline correspond closely to areas with rapid urbanization, agricultural dependence, and limited adaptive infrastructure—conditions characteristic of much of the Global South. The intensification of heat exposure since the mid-twentieth century, compounded by urban heat island effects and prolonged periods above , has dramatically increased population-level thermal stress. Climate-induced economic strain, food insecurity, and migration further interact with biological mechanisms, amplifying demographic and behavioral responses to environmental change.

In conclusion, this paper demonstrates that rising global temperatures can be considered a plausible and understudied driver of fertility declines and male infertility. The strength and persistence of statistically significant climate–fertility correlations, supported by well-documented physiological pathways, suggest that thermal stress may act as both a direct biological constraint and an indirect socioeconomic stressor shaping reproductive outcomes. In either case, climate change should therefore be recognized not only as an environmental and public health crisis but also as a reproductive and demographic challenge with profound implications for population sustainability and the future of humanity. Addressing this emerging threat will require integrated research that links climatology, reproductive physiology, and social science, alongside public health interventions and climate mitigation strategies designed to safeguard fertility and ensure demographic stability in a warming world.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.A. and B.B.; methodology, A.A. and B.B.; software,A.A.; validation, A.A. and B.B.; formal analysis, A.A. and B.B..; investigation, A.A. and B.B.; resources, B.B.; data curation, A.A. and B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A. and B.B..; writing—review and editing, A.A. and B.B.; visualization,A.A; supervision, B.B.; project administration, B.B.; funding acquisition, B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TFR |

Total Fertility Rate |

| NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| TSGA10 |

Testis-Specific Gene 10 |

| CytC1 |

Cytochrome c1 |

| COX |

Cytochrome c Oxidase |

| ERSST |

Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature |

| GHCN-M |

Global Historical Climatology Network-Monthly |

| LOESS |

Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing |

| OLS |

Ordinary Least Squares |

| UHI |

Urban Heat Island |

| UN DESA |

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

References

- Leslie, S.W.; Soon-Sutton, T.L.; Khan, M.A.B., Male Infertility. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Updated 2024 Feb 25; Cited 2025 Oct 13].

- Mitsunami, M.; Hart, J.E.; Chavarro, J.E. Environmental Hazards and Male Fertility: Why Don’t We Know More? Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 2024, 42, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Mo, C.; Si, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J. Temperature change and male infertility prevalence: an ecological study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climate Central. Pregnancy Heat-Risk Days Added by Climate Change in U.S. States. https://www.climatecentral.org/graphic/pregnancy-heat-risk-days?graphicSet=Pregnancy+Heat-Risk+Days+Added+by+Climate+Change+in+US+States&lang=en, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-13.

- Kirchengast, G.; Haas, S.J.; Fuchsberger, J. Compound Event Metrics Detect and Explain Ten-Fold Increase of Extreme Heat over Europe. arXiv 2025. Version 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, Q.; Ni, H.; Xu, T.; Cai, X.; Dai, T.; Wang, L.; Song, C.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; et al. Effects of Temperature Anomaly on Sperm Quality: A Multi-Center Study of 33,234 Men. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.H. Effects of Heat Stress-Induced Sex Hormone Dysregulation on Reproduction and Growth in Male Adolescents and Beneficial Foods. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, L.; Finocchi, F.; Jawich, K.; Ferlin, A. Global Warming and Testis Function: A Challenging Crosstalk in an Equally Challenging Environmental Scenario. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2023, 10, 1104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, I.; Nanayakkara, S. A Review of Scrotal Temperature Regulation and Its Importance for Male Fertility. Sri Lanka Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2021, 43, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastelic, J.P.; Cook, R.B.; Coulter, G.H. Scrotal/Testicular Thermoregulation and the Effects of Increased Testicular Temperature in the Bull. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 1997, 13, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducreux, B.; Patrat, C.; Trasler, J.; Fauque, P. Transcriptomic Integrity of Human Oocytes Used in ARTs: Technical and Intrinsic Factor Effects. Human Reproduction Update 2024, 30, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, M.; Torvisco, S.N.; García-Merino, C.; Fernández-González, R.; Pericuesta, E. Mechanisms of Hormonal, Genetic, and Temperature Regulation of Germ Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, and Death During Spermatogenesis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailin, G.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Jing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Liao, T.; Shen, L.; Zhu, L. The RNA-seq Mapping of Testicular Development after Heat Stress in Sexually Mature Mice. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.; De Nardo, A.N.; Maggu, K.; Sbilordo, S.H.; Roy, J.; Snook, R.R.; Lüpold, S. Fertility Loss and Recovery Dynamics after Repeated Heat Stress across Life Stages in Male Drosophila melanogaster: Patterns and Processes. Royal Society Open Science 2024, 11, 241082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, D. Negative Effect of Seasonal Heat Stress on Testis Morphology and Transcriptomes in Angora Rabbit. BMC Genomics 2025, 26, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modarressi, M.H.; Cameron, J.; Taylor, K.E.; Wolfe, J. Identification and Characterisation of a Novel Gene, TSGA10, Expressed in Testis. Gene 2001, 262, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnam, B.; Modarressi, M.H.; Conti, V.; Taylor, K.E.; Puliti, A.; Wolfe, J. Expression of Tsga10 Sperm Tail Protein in Embryogenesis and Neural Development: From Cilium to Cell Division. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 344, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Bracht, J.; Behnam, B. TSGA10 as a Model of a Thermal Metabolic Regulator: Implications for Cancer Biology. Cancers 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, B. Investigation of TSGA10 Gene Expression, Localization, and Protein Interaction in Human and Mouse Spermatogenesis. Ph.d. thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2005.

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Ghadyani, M.; Kashanchi, F.; Behnam, B. Exploring TSGA10 Function: A Crosstalk or Controlling Mechanism in the Signaling Pathway of Carcinogenesis? Cancers 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.; Deschenes, O.; Guldi, M. Maybe Next Month? Temperature Shocks and Dynamic Adjustments in Birth Rates. Demography 2018, 55, 1269–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, T.; Hajdu, G. Temperature, Climate Change, and Human Conception Rates: Evidence from Hungary. J. Popul. Econ. 2022, 35, 1751–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. Ambient Temperature, Birth Rate, and Birth Outcomes: Evidence from South Korea. Popul. Environ. 2020, 41, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.; Schaller, J. The Impact of High Ambient Temperatures on Delivery Timing and Gestational Lengths. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhoo, D.P.; Brink, N.; Radebe, L.; et al. . A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Heat Exposure Impacts on Maternal, Fetal and Neonatal Health. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Shen, X.; Fan, L.; Zhang, J. Extreme Temperature Exposure and Risks of Preterm Birth Subtypes Based on a Nationwide Survey in China. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, C.J.; Joglekar, D.J.; Hatch, E.E.; Rothman, K.J.; Wesselink, A.K.; Willis, M.D.; Wang, T.R.; Mikkelsen, E.M.; Eisenberg, M.L.; Wise, L.A. Male Personal Heat Exposures and Fecundability: A Preconception Cohort Study. Andrology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Si, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Mo, C.; Ma, J. Ambient Temperature and Female Infertility Prevalence: An Ecological Study Based on the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2025, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, K.X.; Deng, Z.C.; Liu, M.; Huang, Y.X.; Yang, J.C.; Sun, L.H. Heat Stress Impairs Male Reproductive System with Potential Disruption of Retinol Metabolism and Microbial Balance in the Testis of Mice. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 3373–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M. Heat Stress on Reproductive Function and Fertility in Mammals. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2011, 11, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, C.; Melton, D.W.; Saunders, P.T.K. Do Heat Stress and Deficits in DNA Repair Pathways Have a Negative Impact on Male Fertility? Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, L.; Nakstad, B.; Roos, N.; Bonell, A.; Chersich, M.; Havenith, G.; Luchters, S.; Day, L.; Hirst, J.; Singh, T.; et al. Physiological Mechanisms of the Impact of Heat During Pregnancy and the Clinical Implications: Review of the Evidence from an Expert Group Meeting. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenson, D.; Roth, Z. Impact of Heat Stress on Cow Reproduction and Fertility. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A. Extreme Heat and Human Fertility: Amplified Challenges in the Era of Climate Change. J. Therm. Biol. 2025, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, G.; Shayegh, S.; Moreno-Cruz, J.; Bunzl, M.; Galor, O.; Caldeira, K. The Impact of Climate Change on Fertility. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.S.; et al. . The Effects of Climate Change on Fertility and Reproduction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. UN Population Division Data Portal: Interactive Access to Global Demographic Indicators. https://population.un.org/dataportal/home?df=6451d600-2a87-4a3b-9dd7-98d2c95d9577, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-13.

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al., Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1513–1766. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Gao, K.; Khan, H.; Ulpiani, G.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Yun, G.Y.; Santamouris, M. Overheating of Cities: Magnitude, Characteristics, Impact, Mitigation and Adaptation, and Future Challenges. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuholske, C.; Caylor, K.; Funk, C.; Verdin, A.; Sweeney, S.; Grace, K.; Peterson, P.; Evans, T. Global Urban Population Exposure to Extreme Heat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Weather Attribution. Climate change made the deadly heatwaves that hit millions of highly vulnerable people across Asia more frequent and extreme. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-made-the-deadly-heatwaves-that-hit-millions-of-highly-vulnerable-people-across-asia-more-frequent-and-extreme/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-13.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results, 2022. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/No. 3.

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; et al., Eds. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 2391. [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Global Climate Report – Annual 2023, 2023.

- Mukherjee, S.; Mishra, A.; Mann, M.E.; Raymond, C. Anthropogenic Warming and Population Growth May Double US Heat Stress by the Late 21st Century. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, H.; Jørgensen, N.; Martino-Andrade, A.; Mendiola, J.; Weksler-Derri, D.; Jolles, M.; Pinotti, R.; Swan, S.H. Temporal Trends in Sperm Count: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of Samples Collected Globally in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Hum. Reprod. Update 2023, 29, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Fertility rate, total (births per woman). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN, 2025. World Population Prospects, United Nations (UN), UN Population Division; Accessed: 2025-10-13.

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS). GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP v4). https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/, 2025. Dataset accessed 2025-10-13; monthly updates ceased due to federal funding lapse.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).