1. Introduction

Climate change is an undeniable reality, and its consequences are being felt across the globe. Rising temperatures, frequent heat waves, and other extreme weather events are increasingly common [

1,

2]. At the same time, male factor-related infertility is a rising phenomenon among infertile couples, with 40-50% of fertility cases attributed to men [

3]. Today, approximately 2% of all men have suboptimal sperm according to at least one parameter of sperm quality [

4]. The decline in sperm quality was first reported in 1974 [

5], and since then, numerous studies have confirmed this trend among men worldwide [

6,

7,

8,

9], most recently in a 2022 widely-reported meta-analysis by Levine et al [

10]. Despite the concurrent decline of sperm quality and deepening understanding of the wide-ranging adverse health implications

of climate change, there is a lack of research about the impact of environmental exposures on sperm quality. In this project we focused on heat as one environmental factor that may be contributing to this trend.

Four of the main parameters in sperm quality analyses are percentage of motile sperm, percentage of progressively motile sperm, normal sperm count (millions per ejaculate), and sperm concentration (millions per milliliter of semen). Motility, or mobility, is the ability of the sperm cell to move, while

progressive motility is the ability of the cell to move toward the ovum, as opposed to vibrating in place. Sperm quality and its variation can be due to both the physiological and environmental factors that men are exposed to during the approximately 90 days of spermatogenesis [

11].

The relationship between ambient temperature and sperm quality is gaining attention [

12,

13,

14]. The male body is built to regulate the temperature of the testes through an adaptation mechanism called thermoregulation [

15]. When the temperature around the testes rapidly increases, thermoregulation may fail, and studies have shown that an increase in testicular temperature can lead to testicular hyperthermia and genital heat stress, resulting in decreased sperm concentration, motility, and viability [

16,

17]. However, there is a lack of research on the effects of environmental rather than directly applied heat on sperm quality.

A small number of studies have examined the impact of ambient temperature on sperm quality. In the first, researchers looked at the effect of ambient air temperature and pollution on sperm concentration and total sperm volume during the coldest months of the year in Northern Italy, reporting a slight inverse relationship between air temperature and sperm quality [

18] where increased temperature was linked to reduced sperm quality. The second study [

12], conducted in Wuhan, China in 2020, was one of the first to examine the effect of ambient temperature on sperm quality year-round. Wang et al found that an increase of one degree above a temperature threshold was associated with a decrease in normal sperm morphology. Motility and sperm concentration were affected only in the earliest stages of cell development.

Most recently, Reimer-Benaim et al reported on the impact of seasonality on the relationship between temperature and sperm quality in the Southern Israel [

19]. Specifically, researchers reported that this relationship differed between the sperm quality parameters and across stages of spermatogenesis. Motility and sperm concentration improved with increased temperatures until a temperature threshold of 23

0C was reached and they began to decline. Reiner-Benaim’s research focused on the mean daily temperatures, while this project zeroes in on the minimal and maximal daily temperatures in winter and summer, respectively. Additionally, this paper covers a longer study period (2009-2023) compared to Reiner-Benaim’s paper which included data from 2016 to 2022.

The Negev region of Israel provides a unique opportunity to study the effects of extreme temperature. The region is arid and semi-arid, spanning from Kiryat Gat south to Eilat, and covers more than half of Israel’s territory. Winters in this region are characterized by very cold nights and relatively warm days and summers are very hot. SUMC is the only tertiary hospital in the Southern Israel, a region that covers over 60% of the country. The men arriving for sperm analysis are covered by the universal healthcare law, ensuring that the sperm analysis results are representative of the population of couples requiring infertility treatment. The collection of sperm analysis values from men attending the fertility clinic at SUMC is an excellent resource for studying sperm quality over time and associated risk factors [

20,

21]. Given that the clinic's patient population seeks to determine the source of infertility, whether from the male or female partner, the male cohort includes both fertile and infertile individuals. This provides an opportunity to investigate these groups separately, with particular focus on the healthy group, which can serve as a representative sample of the general male population for comparative studies. Additional stratification can be made by the medical history of individuals attending the clinic, as well as demographic and socioeconomic factors.

In this analysis, our goal was to assess the relationship between extreme desert climate temperatures and sperm quality, with an emphasis on identifying at-risk subpopulations. Highlighting these groups could provide physicians with targeted recommendations for patients undergoing fertility treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective population-based study of 11,782 men who underwent semen analysis at Soroka University Medical Center between May 2009 and March 2023.

Clinical data, including comorbidities, past hospitalizations, medications, and sperm analysis results were collected through the SUMC fertility database and Chameleon EMR. Demographic data, including residential coordinates, age, smoking status, immigration status with place of birth, socioeconomic information, was sourced from the database of all Clalit HMO clinics in the region.

Environmental data, as in temperature and relative humidity records, were obtained from monitoring station reports from the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MoEP) and Israeli Meteorological Services (IMS). These stations report temperature readings in 5-minute increments, from which we calculated mean hourly temperatures. Outlier temperature readings, defined as exceeding a 15-degree difference and 3 standard deviations from the average temperature of that station’s district on that day, were coded as missing. We performed a spatial join, matching each patient with the closest five stations to his residents and collecting temperature and RH measurements for the 90 days preceding each sperm analysis test.

We sought to explore the association of high temperature exposure with sperm quality results throughout the 90-day period of spermatogenesis and identify the stage of spermatogenesis that is most sensitive to temperature. To do so, we built a Distributed Nonlinear Lag Model (DNLM) to model the lagged effects of temperature over the 90, 30, and 7 days before sperm analysis. We used a crossbasis matrix to predict the lag temperature and RH values and included these both in the generalized linear model (GLM) analysis, with the RH crossbasis matrix as a covariate. We used an Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) test for goodness of fit metrics.

We used the average maximal temperature in the two days preceding sperm analysis as the primary exposure at study for summer months. The average minimal temperature in the two days preceding sperm analysis was the primary exposure for winter months.

We used a generalized additive mixed models (GAMM) with a cubic spline function to account for the nonlinear relationship between temperature, RH, SES and the outcome variables. Furthermore, individual patients were treated as clusters, and therefore assigned random intercepts, to account for repeated measurements taken on the same individuals. The results of sperm concentration analysis were log-transformed. Motility was our primary outcome as our literature review indicates that it is a critical sperm parameter for fertility and serves as a reliable indicator of overall health [

11]. Progressive motility, normal cells, sperm concentration, total sperm count, and semen volume were secondary outcome variables. We used a mixed-effect negative binomial regression to estimate the relative effect of exposure to the bottom 25

th percent of temperatures in the winter and the top 25

th percent of temperatures in the summer on sperm quality parameters.

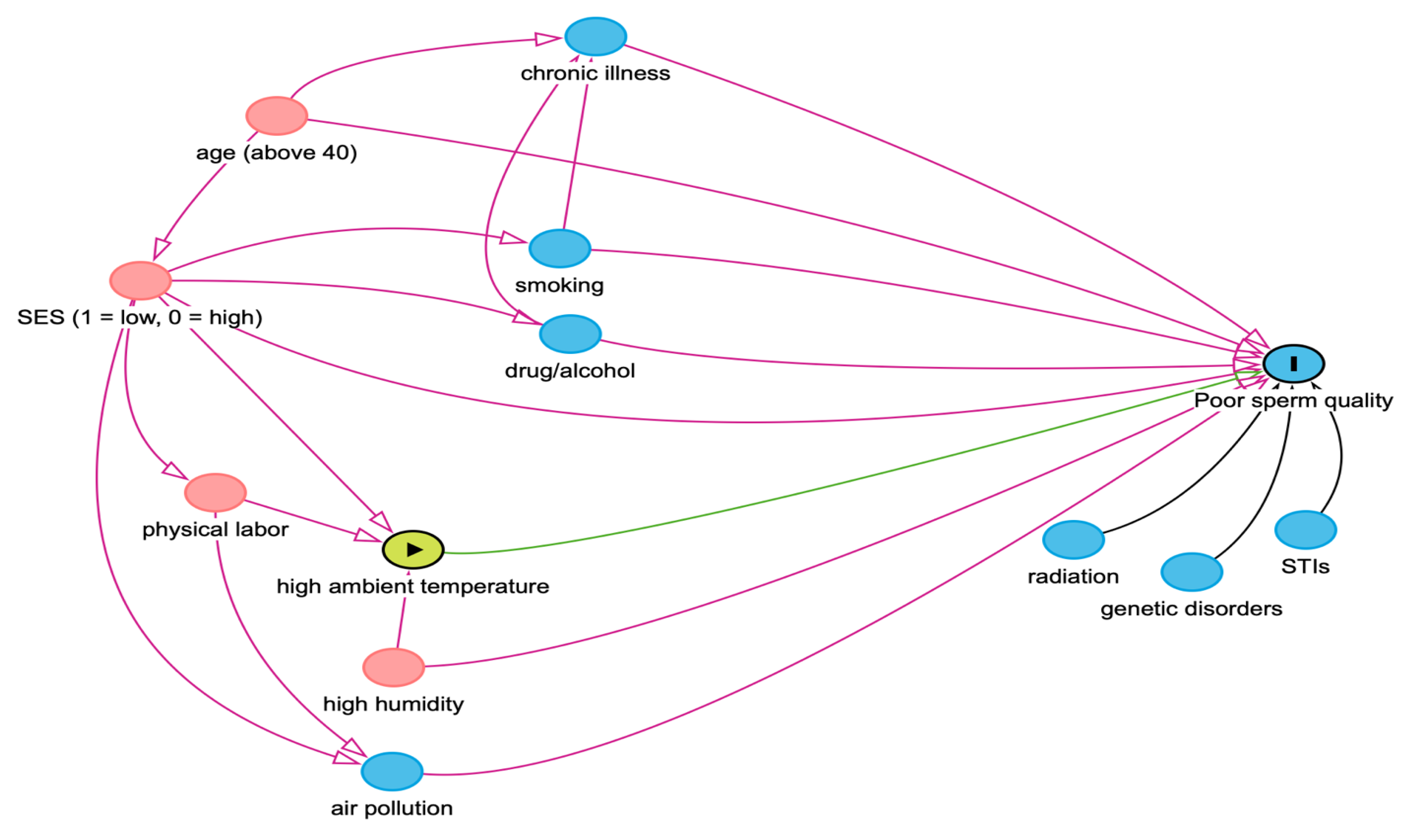

We used a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to assess potential confounding variables, which were included as covariates. Relative humidity and socioeconomic status were included as potential confounders for these analyses. We performed subgroup analyses to determine what groups are most impacted by exposure to the bottom 25th and top 25th percentiles of ambient temperatures and its impact on motility.

Men who had at least one sperm parameter classified as “out of range” according to the WHO sperm analysis standards [

11] were classified as “abnormal”. For our subgroup analysis of motility, those with low motility results (under 39%) were classified “abnormal”. Low socioeconomic status (SES) is defined as men receiving a score of 0-2 and high SES as a score above 8, a distinction made based on the distribution of SES among this population. Men who had at least one chronic diagnosis at any of their testing encounters were designated as having some comorbidity.

3. Results

3.1.1. Demographic Results

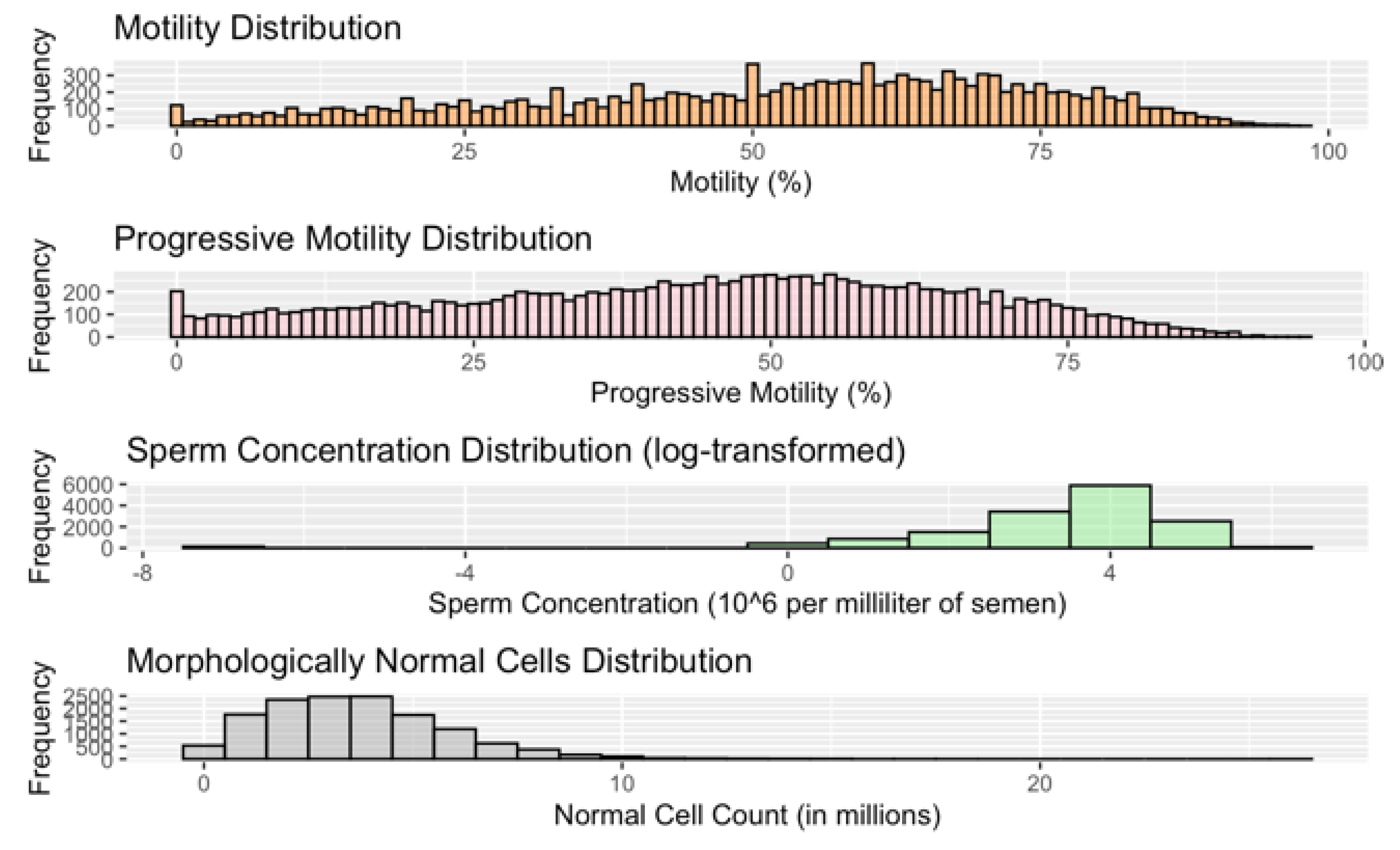

In all, 11,782 men were included in the study analysis. Almost all men were tested at least twice, resulting in 21,331 testing “encounters.” The age range of this population at the time of the semen analysis is 18 to 79, with an average age of 31 (

Table 1). Thirty-two percent (32%) of men were Arab and 68% were Jewish. Forty-seven percent (47%) of men had normal sperm quality results across all parameters, 42% among Arab and 54% among Jewish participants. Men with abnormal sperm were of lower socioeconomic status, slightly older, and smoked slightly more than those with normal sperm. The former group also had higher rates of every chronic illness that was assessed, especially diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. Jewish men had lower rates of comorbidity and significantly better sperm quality across all parameters (ibid). The median percentage of motile sperm in all testing encounters was 56% and 46% for progressively motile sperm (

Table 1 and

Figure A1).

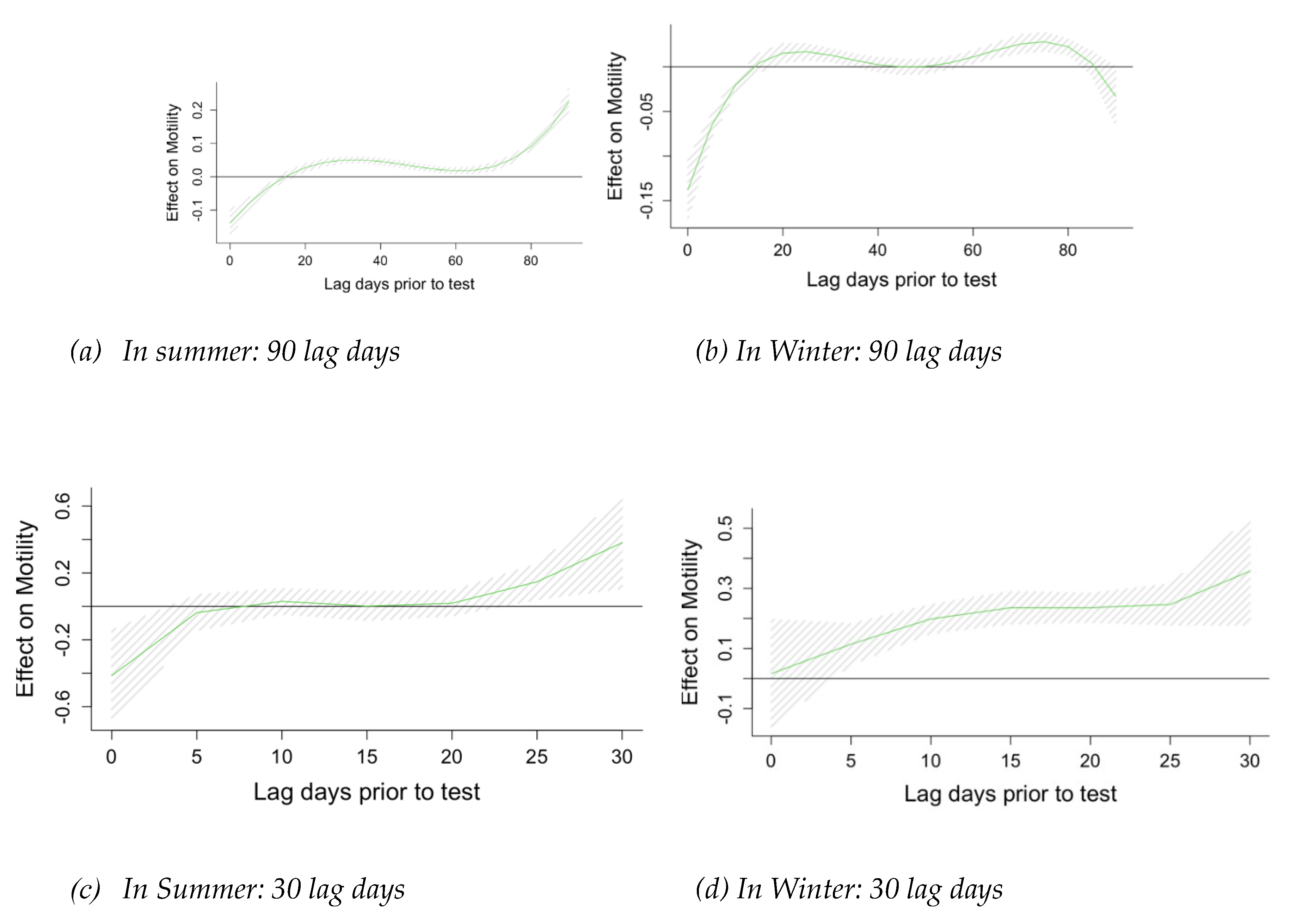

3.1.2. Confounder and Time Window Selection

Using the DAG methodology, we determined SES and RH to be potential confounders, as lower SES may lead to higher exposure to extreme temperature levels, as well as poorer sperm quality. Likewise, relative humidity is also related to ambient temperature and is thought to harm sperm quality (

Figure 1). Using DNLM analysis, we estimated the lagged effect of temperature on sperm quality 90, 30, and 7 days before the sperm analysis, controlling for RH and SES. We identified lag 0-1 days as the most relevant exposure window for the effect of temperature on motility, progressive motility, and sperm concentration (

Figure A2) and proceeded to estimate this relationship for the temperatures averaged over 0-1 lag window period.

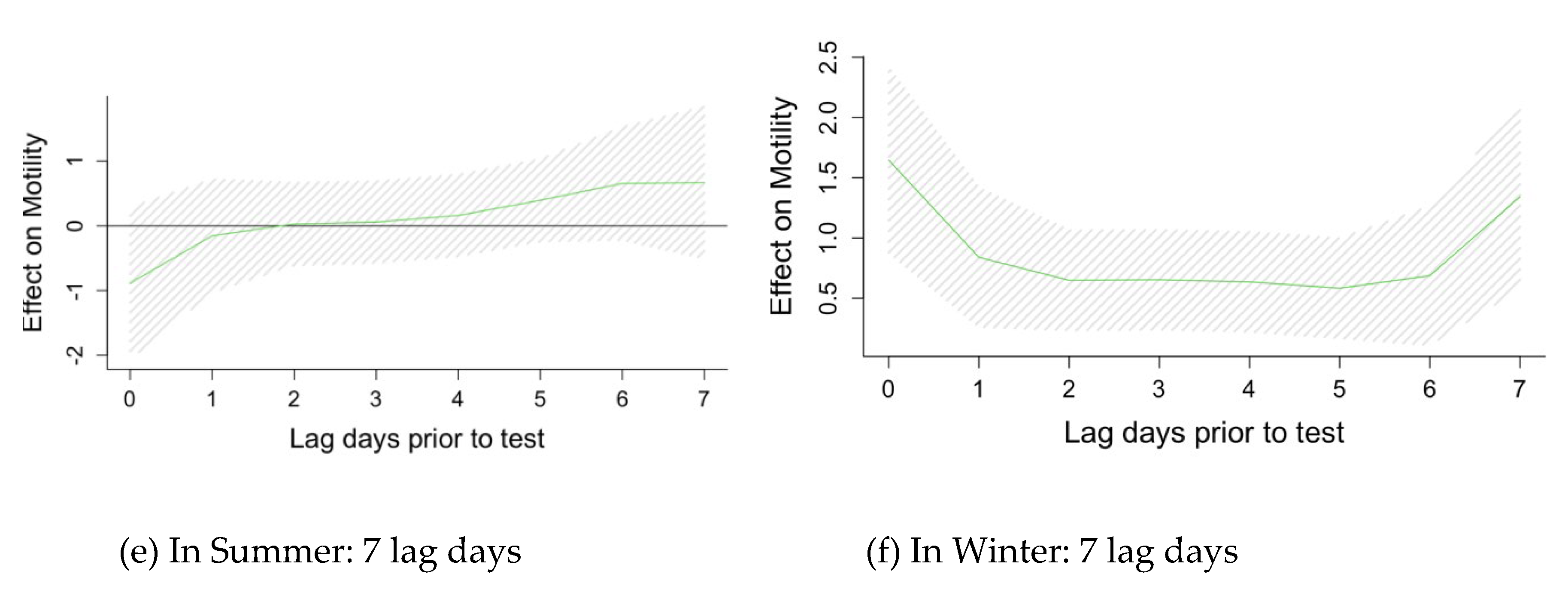

3.1.3. Seasonal Analysis

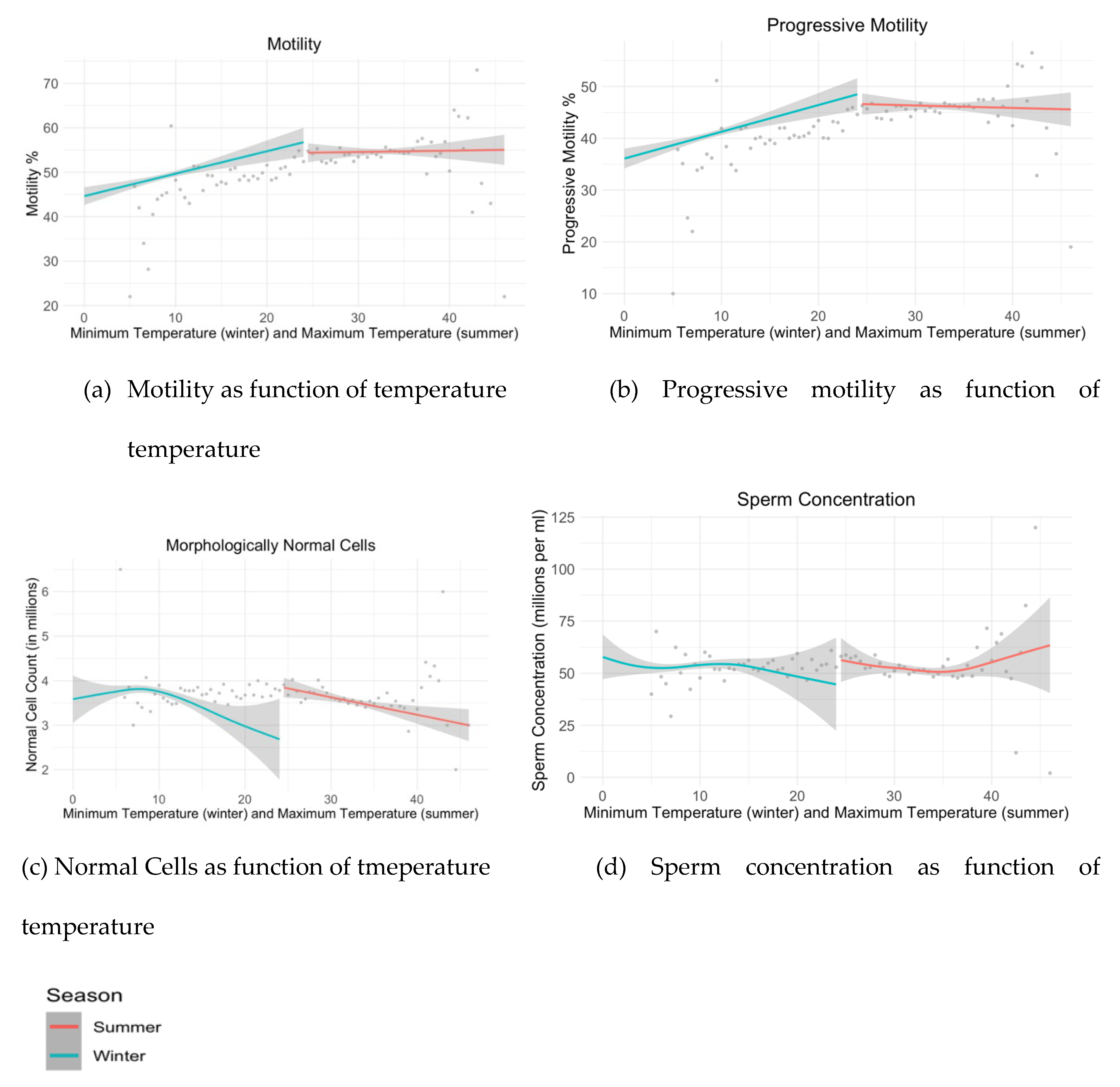

The impact of temperature varied between seasons, necessitating a stratification by seasons as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for summer and winter. Maximum daily temperatures in the summer months (May-September) ranged from 25.3-46.4 degrees Celsius, and minimal daily temperatures in winter (December-March) ranged from 0.7-20.7 degrees Celsius. The bottom 25% of minimum winter temperatures ranged from 0.7-7.1 degrees Celsius, and the top 25% of maximum daily summer temperatures ranged from 34.3-43.1 degrees Celsius. Test results of those who were exposed to the bottom quartile of minimum daily temperatures in the two days preceding testing in winter months showed 5.8% (p-value <0.001) fewer motile sperm cells, on average, than for those who were exposed to the higher 75% of winter temperatures (

Table 2). Progressive motility was similarly negatively associated with low temperatures in winter months, decreasing by 7.07% (p-value <0.001), on average, relative to higher minimum daily temperatures. Results for sperm concentration, semen volume, total cell, and normal cell count in winter months were not significant. Exposure to the top 25

th percent of maximum daily temperatures in the summer did not present a significant effect on motility (Percent Change= -0.62%, p-value 0.721).

Table 2 Yearlong and summer month analysis used daily maximum temperature and winter month analysis used minimum daily temperature. Controlled for RH and SES. Reported results are percent change in sperm parameter as function of exposure to bottom or top 25

th percentile of temperature, relative to other temperatures, in summer and winter months, respectively.

Figure 2 A graphical representation of sperm quality parameters as a function of temperature stratified by season.

3.1.4. Subgroup Analysis of Motility

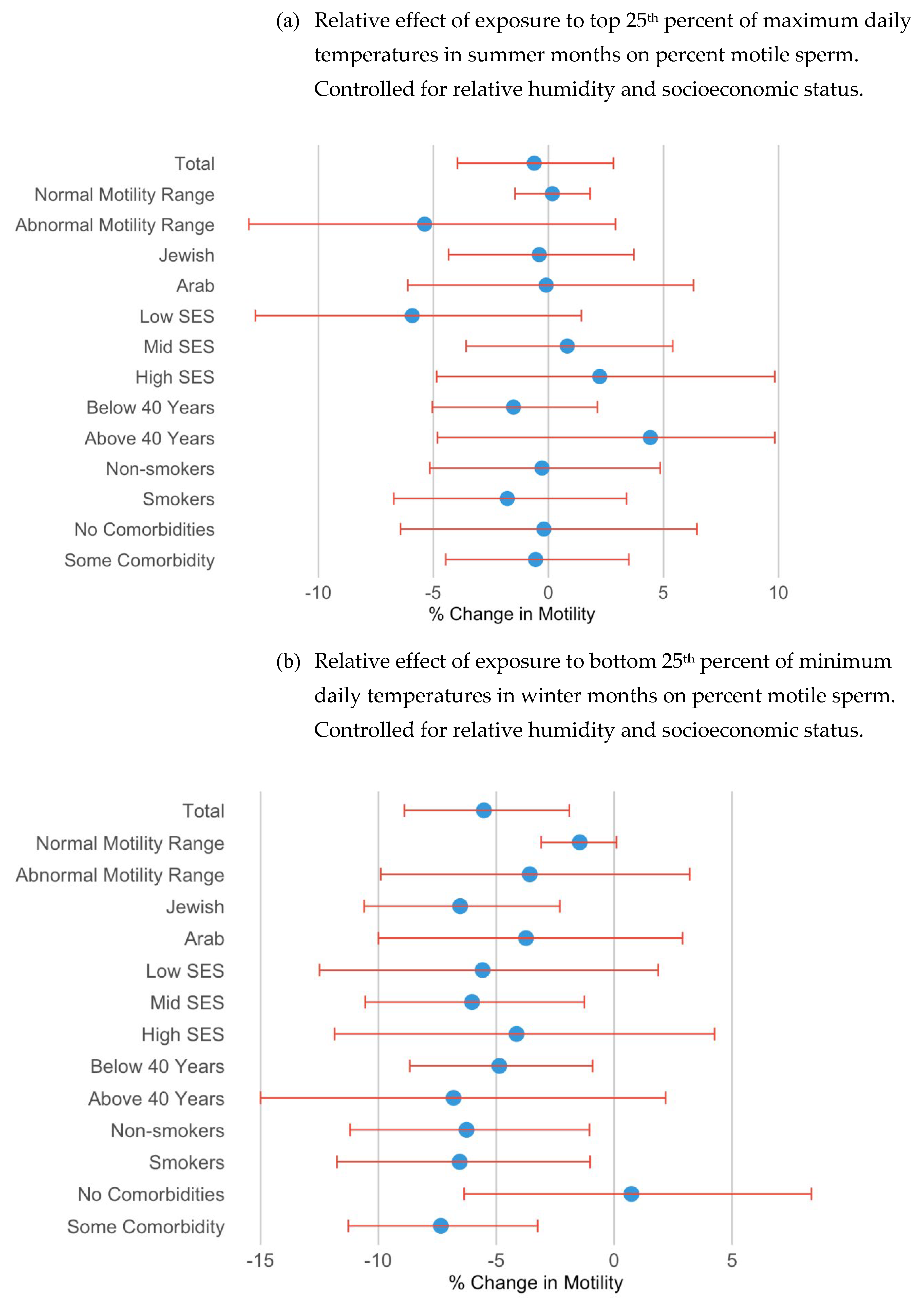

For the subgroup analysis, we focused on motility. Men with abnormal motility showed a greater negative impact from exposure to the lower temperatures, albeit with borderline significance, compared to those with normal motility (

Figure 3). Specifically, the decrease of motility among men with abnormal motility was of higher magnitude (Percent Change = -3.59% (p = 0.201), while the decrease was only 1.46% (p = 0.072) for men with normal motility. In the ethnic subgroup analysis, Jewish men exhibited a more pronounced reduction in motility due to low winter temperatures. Among Jewish men, motility decreased by 6.53% (p = 0.002), compared to a decrease of 3.74% (p = 0.366) in Arab men, on average. Additionally, older men (above 40) appeared to have a stronger negative correlation with lower temperatures, with borderline significance. Healthy men (without comorbidities) were not significantly impacted by exposure to the lowest 25% of daily minimum temperatures; however, motility among men with comorbidities decreased by over seven percent (-7.35%, p = 0.001).

As seen in

Figure 3 and

Table S1(a), exposure to the top quartile of maximum daily temperature in summer months had a borderline significant effect only among those in the lowest socioeconomic status, reducing motility by 5.92% (p-value 0.112). The motility results in other subgroups were not significantly impacted by exposure to the highest quartile of temperatures.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the effects of ambient temperature on sperm quality and to identify what demographic and clinical subgroups are most vulnerable to extreme temperatures. Contrary to our expectations, the results indicated that sperm quality is more adversely associated with cold temperatures than with heat.

The minimal association between increased temperature and lower sperm quality is in line with findings of previous studies, such as the 2010 case-control study conducted by Momen et al [

20]. In their research, they reported nonsignificant differences in semen analysis parameters between individuals exposed to excessive heat and a control group. The researchers attributed this finding to the body's adaptive mechanisms, emphasizing the scrotal region's efficacy in dissipating heat and self-regulating its temperature (ibid.). Similarly, studies conducted in Wuhan and Northern Italy found inverse relationships between temperature and normal sperm morphology and sperm concentration, but not for sperm motility [

12,

18]. Wang et al situates his findings amongst “most studies” on this topic which also came to unclear results regarding increased heat and sperm quality [

12]. Moreover, when significant relationships were identified in the Italian and Wuhan studies, they were primarily observed during the early stages of sperm development. Our DLM analysis indicated that the two days leading up to sperm testing were the most sensitive periods, contrasting with the 70–90-day lags explored in those studies.

Summers in the Negev are hot, and it is not uncommon that temperatures reach 40 degrees Celsius. During hot spells, people tend to seek refuge in air-conditioned environments, reducing their exposure to extreme heat. The body, especially the scrotal area, has its own adaptation mechanisms [

21]. When comparing these findings to those in the study performed in Italy [

18], differences in homes and access to air conditioning may explain the discrepancy. Most homes and office spaces in Italy do not have air conditioning [

22], rendering residents more vulnerable to extreme heat, thus increasing the risk of adverse health effects [

23], such as decreased sperm quality.

Other studies, including the recent Reimer-Benaim paper, identified an inverted U-shape relationship between ambient temperature and sperm quality, demonstrating the harmful effect of not just heat, but of cold as well [

19]. Reiner-Benaim’s research sought to identify the temperature that corresponds with optimal sperm quality, identifying 23-24 degrees Celsius as the threshold temperature below and above which sperm quality suffers.

The effect of cold temperatures in the winter months on sperm quality in this study population were much more pronounced. Cold temperatures in the winter months were associated with lower sperm quality (

Figure 2), particularly at the extreme (

Table 2). Higher minimum temperatures were positively associated with both motility and progressive motility throughout the year. In the arid climate of the Negev, nights are especially cold, so lower daily minimum temperature, which occurs at night, is expected to accelerate potential adverse health effects.

While most people in the Negev region have access to air conditioning, homes are ill-equipped to protect against cold weather, leaving residents more vulnerable to shifts in temperature in the winter than they may be in the summer. Homes in this region are often poorly isolated and fail to protect against the harsh desert winds. Given the biological and behavioral adaptation mechanisms to changing weather, it is reasonable that the coldest temperatures in winter have an especially harmful effect on health outcomes such as sperm quality, while the impact high heat in the summer is negligible.

The relationships between minimum temperature and motility across various demographic subgroups are illustrated in

Figure 3. The motility results of men with abnormal motility (under 39% motile sperm), Jewish men, men above 40, and those with some comorbidities were more adversely affected by exposure to extreme cold than men with normal motility results, Arab men, younger men, and men with no comorbidities. These findings suggest that the former groups may be more vulnerable to cold temperatures. Socioeconomic status was not a differentiating factor. Understanding what social and clinical factors increase an individual’s vulnerability to extreme cold may be crucial in improving his sperm quality and therefore overall fertility. Additionally, exposure to extreme cold is in many cases preventable and can be tackled by improving home insulation and increasing public awareness to potential risks of exposure.

4.1. Limitations

One major limitation of this study is the difficulty of estimating an individuals’ exposure to ambient temperature on a given day. We attempted to approximate exposure by matching individuals to their closest monitoring stations and controlling for SES. There is a potential for information bias as monitoring station temperature recordings contain errors. However, these errors are minimal, and we performed extensive cleaning of the data. Furthermore, relying on monitoring stations is the best method available to us for estimating exposure to ambient temperature. Ideally, we would also have access to indoor temperature readings, given that most people spend most of their time indoors. Further research should attempt to better assess individual exposure through prospective recruitment and monitoring.

5. Conclusions

The central finding of this study is that extreme cold in winter months can have a negative association with sperm motility. The effect of increased heat in the summer months is negligible, owing perhaps to the biological and behavioral adaptation of residents to the extreme heat of the Negev climate. The increasing occurrence of extreme temperatures, both cold and hot, is a central component of climate change. Exposure to extreme temperatures, however, can be prevented by improving home insulation in this desert region and educating the public on the potential dangers of such cold temperatures. The relationship between environmental exposures and declining sperm quality, particularly among men with sub-optimal sperm, older men, smokers, and those with chronic illness, warrants further investigation.

Author Contributions

Kineret Grant-Sasson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original draft Preparation, Visualization. Isabella Karakis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, Supervision. Naama Shteiner: Conceptualization, Writing- Review and Editing. Yuval Mizrakli: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review and Editing. Victor Novack: Conceptualization, Supervision. Lena Novack: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, Supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Soroka University Medical Center (0321-22 SOR)

Informed Consent Statement

This is a retrospective study, based on existing data in the medical record. Data files were coded, and participants remained anonymous.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to medical confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Soroka Clinical Research Center for their invaluable support in facilitating this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Sperm quality parameter distribution.

Figure A1.

Sperm quality parameter distribution.

Figure A2.

Incremental effects of 10-unit increase in temperature. Results of Distributed Lag Model.

Figure A2.

Incremental effects of 10-unit increase in temperature. Results of Distributed Lag Model.

Table A1.

Extended subgroup analysis: Mixed-effect Negative Binomial Results for Motility levels.

Table A1.

Extended subgroup analysis: Mixed-effect Negative Binomial Results for Motility levels.

| (a) Relative effect of exposure to top 25th percent of maximum daily temperatures in summer months on percent motile sperm |

| Subgroup |

Effect on Motility (%), 95% CI |

P value |

| Total |

-0.62% (-3.96, 2.83) |

0.721 |

| Sperm status |

|

|

| Normal Motility Range |

0.17% (-1.45, 1.81) |

0.842 |

| Abnormal Motility Range |

-5.38% (-13.02, 2.92) |

0.197 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| Jewish |

-0.4% (-4.34, 3.71) |

0.856 |

| Arab |

-0.1% (-6.11, 6.31) |

0.975 |

| SES |

|

|

| Low |

-5.92%% (-12.74, 1.43) |

0.112 |

| Mid |

0.82% (-3.58, 5.41) |

0.721 |

| High |

2.23% (-4.86, 9.84) |

0.547 |

| Age |

|

|

| Below 40 years |

-1.52% (-5.05, 2.13) |

0.409 |

| Above 40 years |

4.43% (-4.82, 14.58) |

0.360 |

| Smoking status |

|

|

| Non-smokers |

-0.28% (-5.16, 4.86) |

0.913 |

| Smokers |

-1.79% (-6.72, 3.40) |

0.491 |

| Co-morbidities |

|

|

| None |

-0.2% (-6.43, 6.45) |

0.951 |

| Some |

-0.56% (-4.46, 3.50) |

0.782 |

| (a) Relative effect of exposure to bottom 25th percent of minimum daily temperatures in winter months on percent motile sperm |

| Subgroup |

Effect on Motility (%), 95% CI |

P value |

| Total |

-5.52% (-8.9, -1.9) |

0.003 |

| Sperm status |

|

|

| Normal Motility Range |

-1.46% (-3.1, 0.1) |

0.072 |

| Abnormal Motility Range |

-3.58% (-9.9, 3.2) |

0.201 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| Jewish |

-6.53% (-10.6, -2.3) |

0.002 |

| Arab |

-3.74% (-10.0, 2.9) |

0.366 |

| SES |

|

|

| Low |

-5.58% (-12.5, 1.87) |

0.138 |

| Mid |

-6.03% (-10.56, -1.26) |

0.013 |

| High |

-4.14% (-11.86, 4.26) |

0.323 |

| Age |

|

|

| Below 40 years |

-4.87% (-8.66, -0.91) |

0.016 |

| Above 40 years |

-6.81% (-15.0, 2.18) |

0.133 |

| Smoking status |

|

|

| Non-smokers |

-6.26% (-11.20, -1.05) |

0.019 |

| Smokers |

-6.55% (-11.76, -1.02) |

0.021 |

| Co-morbidities |

|

|

| None |

0.73% (-6.36, 8.36) |

0.844 |

| Some |

-7.35% (-11.27, -3.25) |

<0.001 |

References

- Marx, W.; Haunschild, R.; Bornmann, L. Heat waves: a hot topic in climate change research. Theor Appl Climatol. 2021, 146, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehl, G.A.; Tebaldi, C. More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science. 2004, 305, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouannet, P.; Wang, C.; Eustache, F.; Kold-Jensen, T.; Auger, J. Semen quality and male reproductive health: the controversy about human sperm concentration decline. APMIS. 2001, 109, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, C.M.K.; Bunge, R.G. Semen Analysis: Evidence for Changing Parameters of Male Fertility Potential. Fertility and Sterility. 1974, 25, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, S.H.; Elkin, E.P.; Fenster, L. The question of declining sperm density revisited: an analysis of 101 studies published 1934-1996. Environ Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravitsky, V.; Kimmins, S. The forgotten men: rising rates of male infertility urgently require new approaches for its prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Biology of Reproduction. 2019, 101, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, M.Q.; Ge, P.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, D.X. Temporal trends in semen concentration and count among 327 373 Chinese healthy men from 1981 to 2019: a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2021, 36, 1751–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, U.; Shiff, B.; Patel, P. Reasons for worldwide decline in male fertility. Current Opinion in Urology. 2020, 30, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Mindlis I, et al. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017, 23, 646–659.

- Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Jolles M, et al. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of samples collected globally in the 20th and 21st centuries. Human Reproduction Update. 2022 Nov 15;dmac035.

- WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44261 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Wang X, Tian X, Ye B, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Huang S, et al. The association between ambient temperature and sperm quality in Wuhan, China. Environ Health. 2020, 19, 44.

- Appell, R.A.; Evans, P.R.; Blandy, J.P. The effect of temperature on the motility and viability of sperm. Br J Urol. 1977, 49, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperm in hot water: direct and indirect thermal challenges interact to impact on brown trout sperm quality | Journal of Experimental Biology | The Company of Biologists. Available online: https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/220/14/2513/18616/Sperm-in-hot-water-direct-and-indirect-thermal (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Kandeel, F.R.; Swerdloff, R.S. Role of temperature in regulation of spermatogenesis and the use of heating as a method for contraception. Fertil Steril. 1988, 49, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shadmehr, S.; Fatemi Tabatabaei, S.R.; Hosseinifar, S.; Tabandeh, M.R.; Amiri, A. Attenuation of heat stress-induced spermatogenesis complications by betaine in mice. Theriogenology. 2018, 106, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton TR dos S, Mendes CM, de Castro LS, de Assis PM, Siqueira AFP, Delgado J de C, et al. Evaluation of Lasting Effects of Heat Stress on Sperm Profile and Oxidative Status of Ram Semen and Epididymal Sperm. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 1687657.

- Santi D, Vezzani S, Granata AR, Roli L, De Santis MC, Ongaro C, et al. Sperm quality and environment: A retrospective, cohort study in a Northern province of Italy. Environ Res. 2016, 150, 144–153.

- Reimer-Benaim, A. The use of time-dynamic patterns of temperature and flexible generalized models to clarify the relations between temperature and semen quality – PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39025153/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Momen, M.N.; Ananian, F.B.; Fahmy, I.M.; Mostafa, T. Effect of high environmental temperature on semen parameters among fertile men. Fertility and Sterility. 2010, 93, 1884–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang C, McDonald V, Leung A, Superlano L, Berman N, Hull L, et al. Effect of increased scrotal temperature on sperm production in normal men. Fertil Steril. 1997, 68, 334–339.

- Hotter Summers Kill Thousands in a Europe With Scant Air Conditioning - WSJ. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/hotter-summers-kill-thousands-in-a-europe-with-scant-air-conditioning-9c8ab5d8 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022 | Nature Medicine. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-023-02419-z (accessed on 14 September 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).