1. Introduction

Agriculture has changed radically over the period, starting in the 1850s with the Industrial Revolution and in the 1930s to 1960s with the Green Revolution. This development results in increasing dependence of modern agriculture on agricultural chemicals for productivity and efficiency in food production. Agricultural chemicals are a group of synthetic chemicals that include fertilizers, pesticides, and plant growth regulators (Rossetti et al. 2020). The Green Revolution heralded a period of rapid introduction of new farming approaches and technologies, such as heavy use of chemical fertilizers, agrochemicals and synthetic pesticides, and an increasing reliance on large-scale monoculture farming. Fossil fuel-based agrochemicals are byproducts of petrochemical manufacture, and therefore the manufacture and application of these agrochemicals significantly contribute to climate change influences, including direct emissions of CO2 during active production and emissions as a result of issues of soil ecology associated with it (Menegat et al. 2022). Pesticides have played a pivotal role in moulding the world’s food system. They've made possible the advent of industrial agriculture on a massive scale and the astronomical leap in crop yields that has taken place over the last half-plus century, and they’ve played a role in protecting crops from an array of pests, diseases and weed whackers. They are also responsible for enhancing the soil fertility level, pH control, and for obtaining higher crop productivity (Purohit et al. 2024). These developments have been crucial in providing to a rapidly growing world population as well as to persisting world population food security needs. Just consider global consumption of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers alone, which leapt from 12 million metric tons in 1961 to 112 million metric tons in 2020. As farming continues to evolve towards more controlled and technology-intensive environments, such as Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) (Shelford and Both 2020), the application and management of agricultural chemicals are becoming increasingly precise. This shift could lead to a reduction in runoff and leaching, potentially mitigating some of the environmental impacts traditionally associated with conventional field application. But it also poses a question about the energy demands of such systems, and dependence on petrochemical mineral salts. This chapter discusses the multifunctional features of agricultural chemicals in crop growth. It presents (i) their mechanisms, (ii) the analytical techniques for their detection, (iii) the main environmental impacts, (iv) the toxicological effects on human health, and (v) their complex influence on soil microbiota.

2. Agricultural Chemicals and their Mechanisms of Action

The agricultural products are designed to affect plant growth and defend against threats to crops in different ways. How these mechanisms are to be carried out is at the heart of understanding their effects. The modes of action of important agricultural chemicals are summarized in

Table 1.

Fertilizers

Fertilizers are substances, natural or artificial, that are placed in the soil or on land to be used by plants to promote their growth and repair. Current agronomic strategy mainly relies on additions to cocktails of three primary macronutrients i.e., N itrogen (N), P hosphorus (P) and K alium or Potassium (K) (Rodino et al. 2024). Plants require nitrogen for leaf and stem development, as it is a key component of both proteins and DNA. Phosphate, generally in the form of phosphate monoesters or phosphate transferred, is essential to the production of DNA, adenosine triphosphate (the molecule used in cells as a way of storing and transferring energy), and phospholipids (which form the cellular membrane). Potassium helps strengthen the stems of plants as well as open and close the stomata that facilitates water movement in and out of plant leaves.

During the Green Revolution, the fertilizers have been widely used in large-scale industrial agriculture, which has driven a significant increase in crop yields. Since they directly add nutrients, and some formulations even modify soil water and aeration properties, fertilizers contribute to plant growth (Davidson and Gu 2012). The application rates of fertilizers are usually based on some measure of soil fertility, which can be determined by soil test, or by crops taken off a field; as a general rule, non-leguminous crops will remove more nitrogen from the soil than such nitrogen-fixing plants as legumes. Fertilizer materials are commonly applied in solid form or liquid form. Liquid fertilizers have the benefit of being faster acting and capable of providing better uniform coverage (Mc Beath et al. 2005), whereas granulated shapes are often cheaper for transportation and storage. The practice of fertigation, adding fertilizers directly to irrigation water and foliar application, the spraying of fertilizers directly onto leaves, is routine with high-value crops, such as fruits. However, prolonged use of chemical fertilizer is a big challenge to the soil health. Although offering a quick stimulant to plant growth, long-term applications of chemicals can decrease soil organic matter (SOM), soil acidification, and change the community structure and activities of the beneficial microbes (Yang et al. 2025). In this regard, it is different form organic fertilizers, which are produced by composting animal manure, human waste, and plant waste. It has been reported that the application of organic fertilizers positively influences SOM, soil structure, aggregate stability, nutrient uptake, water retention ability, cation exchange capacity, nutrient use efficiency, and the activity of microorganisms (Liu et al. 2024). They also play a role in plant tolerance to abiotic stresses, provide resistance to drought, salinity, heat, and contamination with heavy metals. The availability of nutrients (due to synthetic fertilizers) could over time weaken the soil while increasing production that sustains these practices. Perpetuating the situation is the erosion of soil health that becomes casual, as if inevitable, relegating us to the treadmill of inputs that create a problematic cycle. This illustrates a fundamental trade-off between short-term productivity increases and long-term soil fertility and ecosystem resilience.

Pesticides

There are many types of pesticides, which work as biocides, and they are poisonous substances that are produced to deter, control or kill pests, plant organisms, animals or weeds. This is a collective terminology and includes different types such as insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, algaecides, rodenticides, molluscicides, nematicides etc., most of which are specific for certain pests. Insecticides act in a variety of ways, generally interfering with critical physiological functions of the pest, and effective act on the nervous system. For instance, organophosphates and carbamates work through the inhibition of AChE, an enzyme essential for the nerve impulses transmission (Patočka et al. 2004). This inhibition causes acetylcholine to accumulate at the neuromuscular junction and the affected muscle then shows effects of overstimulation, followed by paralysis. Other insecticides (e.g., lindane, endosulfan and fipronil) disrupt the GABA receptor in the insect, thereby blocking the entrance of chloride ions, thus leading to a hyperexcitable condition and, ultimately, tremors and convulsions (Bloomquist 2003). Others interfere with the normal conduction of nerve impulses by creating a sodium/potassium ion imbalance. Outside of the nervous system, pyrazoles and pyridazinones block the mitochondrial electron transport chain and inhibit the formation of ATP. However, quinazolines affect larval stages of insects, being known an inhibitor or a suppressor of chitin synthesis for being a constituent of exoskeleton (Guo et al. 2020). Some pesticides are also growth regulators; for example, neem oil is an insecticide that affects the moulting hormones of insects, that subsequently develop aberrant behaviour. Plants can take up pesticides from their leaves and roots, which are ultimately transported within the plant (systemic pesticides). Therefore, the plant becomes toxic to feeding insects. In contrast, contact pesticides are quick-acting, resulting in an "instantaneous" knock-down that the comes with contact. Novel insecticides with narrow spectra have been an advance in terms of reducing off-target physiological effects. One issue that remains is the use of broad-spectrum pesticides, some of which have been banned because of their high levels of toxicity to non-target species and demonstrates that full specificity is elusive. There is a need for balancing the instant and widespread control obtained from broad spectrum agents and the long-term effects of targeted approaches, such as decreased ecological impact and improved pest resistance management. This also implies that economic constraints may encourage less specific and cheaper choices.

Herbicides

Herbicides are chemicals that are formulated to kill unwanted plants; they are primarily used in row crop agriculture to optimize crop productivity by reducing competition from weeds. These compounds act by a variety of molecular mechanisms to inhibit weed growth. A widespread mechanism of action is the inhibition of amino acid biosynthesis. Herbicides, such as glyphosate imazethapyr and thifensulfuron, are taken up by the leaves and are translocated to the metabolic sites which inhibit the synthesis of the essential amino acids (Ray 2020). Symptoms will begin to show as leaf discoloration and distortion of new growth over a few weeks. Another important group of herbicides, such as atrazine and cyanazine, function as photosynthetic feed blockers after inhibition of electron transport on the reducing side of photosystem II in chloroplasts (Twitty and Dayan 2024). These non-selective herbicides are used as soil applications and are translocated to the leaves where they compete for binding with the quinone-binding protein D-1, hence inhibiting electron transfer in photosystem II. Artificial auxins or growth regulators such as 2,4-D are analogs of natural plant growth hormones (Song 2024). Sprayed on the leaves of dicots, they are carried to meristems, where they induce uncontrolled growth and distortion, sometimes within minutes. Other modes of action include inhibition of lipid synthesis, mainly in monocot weeds, and inhibition of mitosis, interfering with target plant's cell division. Herbicides may be used spray, soil or aquatic applications.

Growth Regulators

Plant growth regulating substances (PGRs) are natural or synthetic chemical compounds which have a significant role in regulating various physiological activities of the plant even at very low concentrations. These molecules are chemical messengers, responsible for coordinating many aspects of plant growth and development. The five major groups of plant growth regulators are auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, ethylene and abscisic acid (Thapa et al. 2024). Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) type of auxins are best known for being involved under the root forming conditions, fruit drop inhibition, increase in cell elongation, apical dominance (in which the plant's apical bud keeps lateral buds from growing), and playing a major role in phototropism (when plants bend toward light). Auxin signaling is propagated by several gene families, such as Aux/IAA, which encode short-lived nuclear proteins that control gene expression by interaction with auxin response factors (ARFs) (Luo et al., 2018). Gibberellins are known to stimulate stem elongation, leaf expansion, and fruit development, with gibberellic acid (GA3) as a representative. They can also break seed dormancy, and this increases fruit size and fruit quality in horticultural crops. They are synthesized either through the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) or mevalonate (MVA) pathways (Vranová et al. 2013). Cytokinins contribute to senescence delay (antiaging) in plants, increase the growth rate of leaves, increase the number of shoots produced in tissue culture, and are required for cell division. Their biosynthesis involves tRNA-IPT enzymes. Ethylene is a gas-like PGR, related to fruit ripening, leaf shedding, and responses to stress. Ethylene-releasing compounds including ethephon and ethrel are applied for simultaneously ripening of fruit in commercial crops. At last, Abscisic acid (ABA) is a kind of dormancy inducer, germination inhibitor and one stress resistance related substance for plants.

Apart from direct growth, PGRs also increase the plant tolerance against abiotic stress elements like drought, salinity and extreme temperatures by promoting photosynthesis, water use and nutrient use. They are also important for flowering and ripening time, flowering and ripening synchrony, large commercialization and control. Molecularly, PGRs mediate their action through binding to a receptor that localized in plant cells plasma membrane, cytosol and nucleus. This binding initiates a series of signaling events which finally culminate in altered gene transcription and protein activity. Examples are the TIR1/AFB family of F-box proteins for auxins, histidine kinases for cytokinins, and the PYR/PYL/RCAR family for abscisic acid (Kakimoto 2003; Dupeux et al. 2011; Salehin et al. 2015). These responses are mediated by signaling pathways that act both at post-transcriptional and transcriptional levels to control the expression of genes which are under the control of transcription factors (TFs) including ARFs, ERFs, and ABFs.

Fertilizers, Pesticides and Herbicides: How Do They Work with Plants and Pests?

The efficacy of agrochemicals depends on their interaction with plants and pests. For example, fertilizers supply vital nutrients to plants either as uptake by roots of the soil borne elements or through foliage application. These nutrients are subsequently added to organic molecules through different plant metabolic pathways including those associated to nitrogen metabolism, e.g., glutamine synthetase (GS) and glutamate synthase (GOGAT). According to Lam et al. (1996), the main route of N assimilation is the GS-GOGAT system, where ammonium is incorporated into glutamine and glutamate. They are part of large gene families with several isoforms which form the basis of plants being able to adapt nitrogen metabolism according to the environmental conditions (Zayed et al. 2023). Pesticides, on the other hand, are purposely made toxic to target pests. The systemics are taken up by the plant and moved in the plant and then kill the insects feeding on the plant (Cloyd et al. 2011). It has the advantage of protecting from the inside of the plants. By contrast, contact pesticides are those that kill on direct contact; a hit and run pesticide, like pyrethroids, kill but do not last long enough to clear the home of the pest. A herbicide disrupts plant metabolic processes, which can be molecule-specific, and affects growth of the plant or the blockage of a necessary plant process with causes defects or death within hours or days. Fertilizer encourages growth, but pesticides and herbicides are applied to manage impediments to that growth. It should be noted that the simultaneous use of herbicides as well as other pesticides may lead to additive or synergistic effect on non-target organisms, rendering their environmental impact complex.

Alternative Processes in Plant Growth Promotion and Pest Control

Apart from the endemic ones applied in a more or less direct mode, new alternatives to promote plant growth and pest control have been taking place, mainly the use of plant growth-promoting microorganisms (PGPMs). PGPMs, which include beneficial bacteria (Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria, PGPR) and fungi (Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi, PGPF), improve plant growth and health by several modes of action, including nutrient solubilization by which they make essential nutrients like phosphorus more readily available to plant. Such beneficial microorganisms use different strategies to solubilize and mobilize nutrients such as organic acid production, phosphatase activities, and mycorrhizal symbiosis (Pang et al. 2024). PGPMs are also able to produce plant hormones which directly affect the growth and development of the plant. Such hormones are, for example, auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, ethylene abscisic acid and plant growth regulators such as polyamines and nitric oxide (Cassán et al. 2014; Orozco-Mosqueda et al. 2023). Furthermore, PGPMs can use both direct and indirect ways to alleviate plant pathogens, providing a double benefit for disease suppression and growth promotion. PGPMs especially Bacillus and Pseudomonas species secret antimicrobial substance for example, antibiotics, hydrogen cyanide and secondary metabolites prevent the pathogen multiplication (Wang et al. 2024).

3. Analytical Detection of Residues

Residue testing is very important to food safety and regulatory purpose. It refers to the evaluation of chemical toxicants in food commodities and parts of the environment with a view to safeguard health and ecosystems (Oh, 2000). Rapid and efficient screening of agricultural and petrochemicals residues in crop, soil, and water bodies is crucial for present day food safety and environmental monitoring. This includes several advanced analyzing techniques, namely chromatographic and spectrometric methods (

Table 2). Prolonged exposure to higher levels of pesticide residue can lead to significant health problems such as hormone dysregulation, certain cancers, diseases of the nervous system, and defects of the reproductive system. Susceptible groups, such as the elderly, pregnant women, and children, are particularly susceptible. Similarly, the persistent residues in food even after washing or processing, must be meticulously tested to qualify whether the levels exceed Maximum Residue Levels (MRLs) which are the regulatory levels defining the highest concentration of pesticide residue, permitted in a food commodity following application of pesticide under correct conditions of Good Agricultural Practices (Dureja et al., 2015). MRLs are not toxicological thresholds but rather tools for monitoring the correct application of pesticides and for ensuring compliance with registered labelled directions.

Gas Chromatography (GC), sometimes combined with Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), is particularly well suited for the analysis of volatile and thermally stable pesticides, in complex matrices sample. Adsorption or dissolution characteristics of components in a stationary phase provide the basis for the operation of GC. For polar, nonvolatile, or thermally labile compounds, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), often coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), is the method of choice (Alder et al. 2006). HPLC is well known for its high detection sensitivity, excellent separation efficiency, and accuracy and has been widely used for the detection of pesticide residues and heavy metals in various matrix including rice and water. Reversed-phase liquid chromatography with ultraviolet (UV) is a dominant HPLC method used for pesticide determination. Samples are frequently submitted to a laborious preparation procedure before chromatographic analysis, that includes extraction and clean-up and concentration steps carried out, for example, by Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) or Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE). FTIR and Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy FTIR spectroscopy is used for substance identification, based on characteristic absorption values associated with molecular vibrations. NIRS enables fast non-destructive and low-cost detection due to the evaluating of vibrations from H-containing chemical bond (O-H, N-H, C-H). Surface-enhance Raman scattering (SERS) greatly improves weak Raman signals, facilitating the quantitative detection of trace substances, especially heavy metals on the surfaces of fruits and vegetables (as in the case of our interest) even though elaborative substrate construction and the issue of peak shifts remain. Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) are commonly used for elemental analysis of major/minor elements and heavy metals of soils and plants. XRF micro-analysis can also be applied for detailed characterization of element distribution even of single rice grains or leaves. Novel thermal analysis techniques (such as TGA, DSC, and DTA) are becoming useful for studying the thermal behavior and decomposition of the agricultural chemicals and their residues. These methods provide information on thermal stability, decomposition temperatures, and phase transitions, and are suitable for evaluating long term environmental fate, and the analysis of complex mixtures with little, if any, sample clean-up. In fact, the availability of the highly sophisticated detection methods able to reveal residues at the trace level is a precondition for protection of health of human, as well as for assurance in terms of regulatory and risk assessment (Lehotay 2001). The difficulty is that it has to do so not just to tell whether something is present or not, but very specifically how much and which types of residues there is, even as it tests the limits of scientific measurement.

LC-MS/MS is the most common instrumental method to detect agricultural and petrochemical residues in crop, soil and water because of this low-cost, speed and sensitivity. Although GC−MS is excellent at the analysis of volatile compounds, LC-MS/MS has greater flexibility by detecting polar, non-volatile, and thermally unstable compounds, which are typical of modern pesticides and the petrochemical industry, without the need for derivatization, and it is able to speed up the sample preparation and the use of resources (Allwoods et al. 2010). It has very high sensitivity (residue concentration at part-per-billion levels) and specificity (low cross-reaction in comparison to false positives/negatives, which is especially important for regulatory purposes). While initial instrument prices are high (~US $150,000–US $300,000), LC-MS/MS’s high throughput and automation significantly reduce per-sample costs in comparison to slower methods, such as FTIR or XRF. Spectrometric based methods (e.g. NIR, SERS) are quick and inexpensive; however, they do not provide LC-MS/MS based quantitative accuracy or breadth of applicability in complex matrices, which is still the gold standard though emerging methods are gaining momentum. If costs and performance are influenced by the lab scale and complexity of samples, LC-MS/MS is the reference method of analysis for broad residue testing.

4. Environmental Implications

The massive application of agrochemical use has serious environmental impacts, especially when these are not completely absorbed by plants and leak after this release into natural ecosystems. When soil loaded with ag chemicals are introduced in the planting season, most, not just corn, but young plants, have difficulty extracting all nutrients needed for the plant to reach its full potential. Unabsorbed by full-fledged plants in fine form, such agrochemicals could then be lost from the fields of farms to the detriment of natural resources. This environmentally seeded interconnected contamination is, in a way, a “pollution multipler” - contamination in any given compartment will have to result in contamination in the others. For instance, soil pollutants can be easily transferred with runoff to rivers that will become polluted, and soil can be eroded after deforestation, with the pollutants released and sequestrated in it being spread and put in the atmosphere as dust. The systemic nature of this problem — it's all connected, and we must take care of it all if we're going to take care of the environment.

Soil

Over- dose and constant application of chemical fertilizers can nutrient mining of key components of the soil organic matter to a point where the plant becomes increasingly dependent on man-made sources for nutrition (Bisht and Chauhan 2020). It depletes the soil fertility and deteriorates its physical properties. Over time, chemical N fertilizers can reduce SOM, contribute to soil acidification (particularly that containing ammonium or sulfur), as well as modify the structure and function of beneficial microorganisms (Bai et al. 2020). Chemicals of this type lead to accumulation of nasty chemicals such as nitrates to hang around and unbalance the fancy microbial community so essential in the maintenance of a healthy soil. The misguided and overuse of pesticide may lead to direct poisoning of agricultural soil and the undermining and disturbance of important natural nutrient cycles. The same habit-producing residue can be found in dumps of outlawed farm chemicals that, in wholes swaths of the country, have left many soils toxic.

Water

Both nitrogen and phosphorous, which are commonly present in overabundance in fertilizer and animal manure, can be washed away during rain or snow melt events, or seep through the soil and enter the water over time. Inefficient irrigation, in addition, exacerbates the nutrient pollution by increasing runoff and leaching. High concentrations of these nutrients trigger eutrophication, a process characterized by rapid algal growth (algal blooms) (Wurtsbaugh et al. 2019). These blooms take up oxygen from waterbodies and create “dead zones” (hypoxia) that result in fish kills and a crisis in the health of the marine ecosystem. Harmful algal blooms can also produce toxins that are a public health threat. Herbicides and pesticides’ runoff—which require downstream adjustment—disturb aquatic systems, too, at the expense of fish, amphibians and invertebrates. They also can predispose algae by outcompeting plant competitors (turbidity, high siltation) and reducing top-down control of algae (e.g., grazers).

Air

Nitrogen can escape farm fields as volatile nitrogen-based compounds like ammonia and nitrogen oxides. Aquatic life can be compromised by ammonia, especially when it is widespread through the atmosphere as a gas. Another gaseous emission of fertilized soils is nitrous oxide, a strong greenhouse gas involved in climate change. Pesticide volatilization also contributes to farm worker and bystander exposure, separate from spray drift and windblown dust. Volatile (eg, fumigants) and even semivolatile agricultural pesticides add to air pollution. Volatilization is affected by the physical and chemical properties of the pesticide (i.e., especially its vapor pressure), soil properties, persistence on plant foliage, meteorological factors, and particular agricultural practices. Although some pesticides, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and chlordanes, were higher in urban areas, others, such as endosulfan and DDT, had greater concentrations in rural areas (Harner et al., 2004).

A major environmental problem is that many agricultural chemicals, especially older, cheaper pesticides, can persist in soil and water for years or decades. These chemicals are frequently referred to as Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), toxicants that are man-made, dangerous substances representing a threat to human health as well as to the planetary ecosystems and ultimately may result in loss of biodiversity (Kumari et al. 2021). POPs are distinguished by their long-term environmental persistence, high capability for bioaccumulation/biomagnification and long-range transport. Persistence is expressed quantitatively in terms of a chemical's half-life, with a chemical having a half-life in water, soil, or sediment longer than 60 days to be persistent and a half-life longer than 180 days to be very persistent 280. Half-life in air > 2 days indicates persistent.

5. Toxicological Effects on Human Health

The extensive use of agricultural chemicals, mainly pesticides, entails considerable toxicological risks to human populations, which may occur as acute and chronic exposure effects. Pesticides are inherently toxic compounds. Acute poisoning is a colloquial term used to describe severe acute exposure resulting in severe neurotoxic signs and is characterized by adverse effects or fatalities soon after a single exposure (oral, inhalation, or dermal exposure), with signs generally appearing within 48 hours (Sass 2000). Acute symptoms of exposure can include respiratory irritation (eg–sore throat, cough), allergic skin sensitization and eye and skin irritation (eg–burning/stinging, rash, blistering). General symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, severe weakness, dizziness, faintness, unconsciousness, seizures, life-threatening hypotension and cardiovascular collapse. People with asthma or other existing conditions may be particularly sensitive to some pesticide categories (e.g., pyrethrin/pyrethroid, organophosphate, or carbamate pesticides). Among the problems with correctly diagnosing acute poisoning from pesticides is the fact that symptoms can present as common illnesses such as colds or flu, and it is often misdiagnosed, contributing to the problem of underreporting. In the general population, farm workers and pesticide applicators have greater health risks than other persons because farmers have exposure to the chemicals when applying them. Meanwhile, chronic toxicity includes deleterious health effects that occur over time, usually as a result of repeated or continuous exposures to low dose of pesticides (Shekhar et al. 2024). These effects may not have occurred at the time of exposure, but could appear weeks, months, or even years following exposure, hence rendering it difficult for researchers to detect a direct causal relationship between pesticide exposure and the health effects that ensued. This phenomenon draws attention to something that can be labeled as the "invisible illness", i.e., the actual disease burden of low-dose, chronic exposure that is generally unaassessed as a result of the fact that symptoms are non-specific and occur late at the onset. The long latent intervals mean that the current exposures may be providing the conditions for future public health disasters.

Carcinogenicity

Pesticides have been associated with different types of cancer, such as leukemia, lymphoma, and brain, breast, prostate, testis, and ovary cancers (Alavanja et al. 2013). One exposure is unlikely to cause cancer, but exposure repeatedly to carcinogens at very low levels can be a cause of cancer over a long period of time. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) claims that pesticides authorized for global trade are not generally genotoxic (i.e. do not damage DNA which can result in mutation and ultimately cancer), they do have harmful effects if exposure exceeds what is considered to be safe.

Endocrine Disruption

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are chemicals that disrupt normal hormonal systems, and that are active even in minute quantities. Hormones are important little chemicals that tell our bodies how to behave and control a whole lot of important processes including growth, reproduction, metabolism, brain development, the body clock and stress response. Endocrine-disrupting pesticides can show up in different manner such as fertility decline, early puberty, ovarian cysts, disorders of metabolism, degenerative brain diseases, and the impairment of the thyroid function. These compounds may disrupt hormonemetabolism, release, binding, transport receptors and post-receptor activation (Bretveld et al., 2006).

Neurotoxicity

Several pesticides have finally been recognized to be associated with neurodevelopmental delays, neurodegenerative processes and synaptic disfunctions. Exposure for long periods of time can be linked with ailments including Parkinson’s disease, asthma, depression and anxiety, as well as the onset of Alzheimer’s and autism. The synapse is a major site of organophosphate-and organochlorine- and pyrethroid-induced vulnerability by inhibitorys effects on synaptic function (Vester & Caudle, 2016). These mechanisms include cholinergic deficiency, reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, neuro-inflammation, and epigenetic alterations (Mostafalou & Abdollahi, 2018).

6. Impact on Soil Microbiome

The invisible microbial cosmos that resides in the soil is affected by the use of agrochemicals in a dramatic way, with far- reaching consequences for the health of ecosystems and ultimately for our environment. These particles are characterized by a high particle number and submicroscopic particles exhibiting a large specific oxidative capacity. Agricultural chemicals in general, and pesticide especially, are considered as important environmental stressors for the complex microbial communities naturally found in agricultural soils. The toxic effects of pesticides on the microorganisms following pesticide exposure can be harmful. But there are types of microorganisms, notably some species of bacteria, which can get nutrients from pesticides as a food source that can, sometimes, allow them to survive and grow in numbers. This creates feedback in which agrochemicals are not just antimicrobials; they are also potent selective agents, behind the scenes “designing” microbial communities. Ni et al. (2025) have demonstrated that a high rate of pesticides application is a potential environment stress factor influencing the soil microbe function negatively, and the soil microbe is more dependent on soil resources. This line of selection may promote the bacterial specialists and opportunists capable to degrading or to resist pesticides and decrease dominate of generalist bacteria population. However, such shifts in community composition may destabilize multitrophic microbial networks and could potentially be viewed as a driver of soil nutrient depletion. For instance, there may be a selection for resistance within a fungal population due to the use of some fungicides such as metalaxyl-M, and shifts in overall fungal community composition as more or less fungal will influence SOM formation (Sim et al. 2022). The contribution of N input, an element which is key to many crop production systems, can also influence pesticide performance and the net impacts of pesticides on soil microflora. The long-term implications of these effects for soil health and plant vigour are far-reaching and complex, perhaps setting up a vicious cycle in which impoverished microbes demand more chemical inputs.

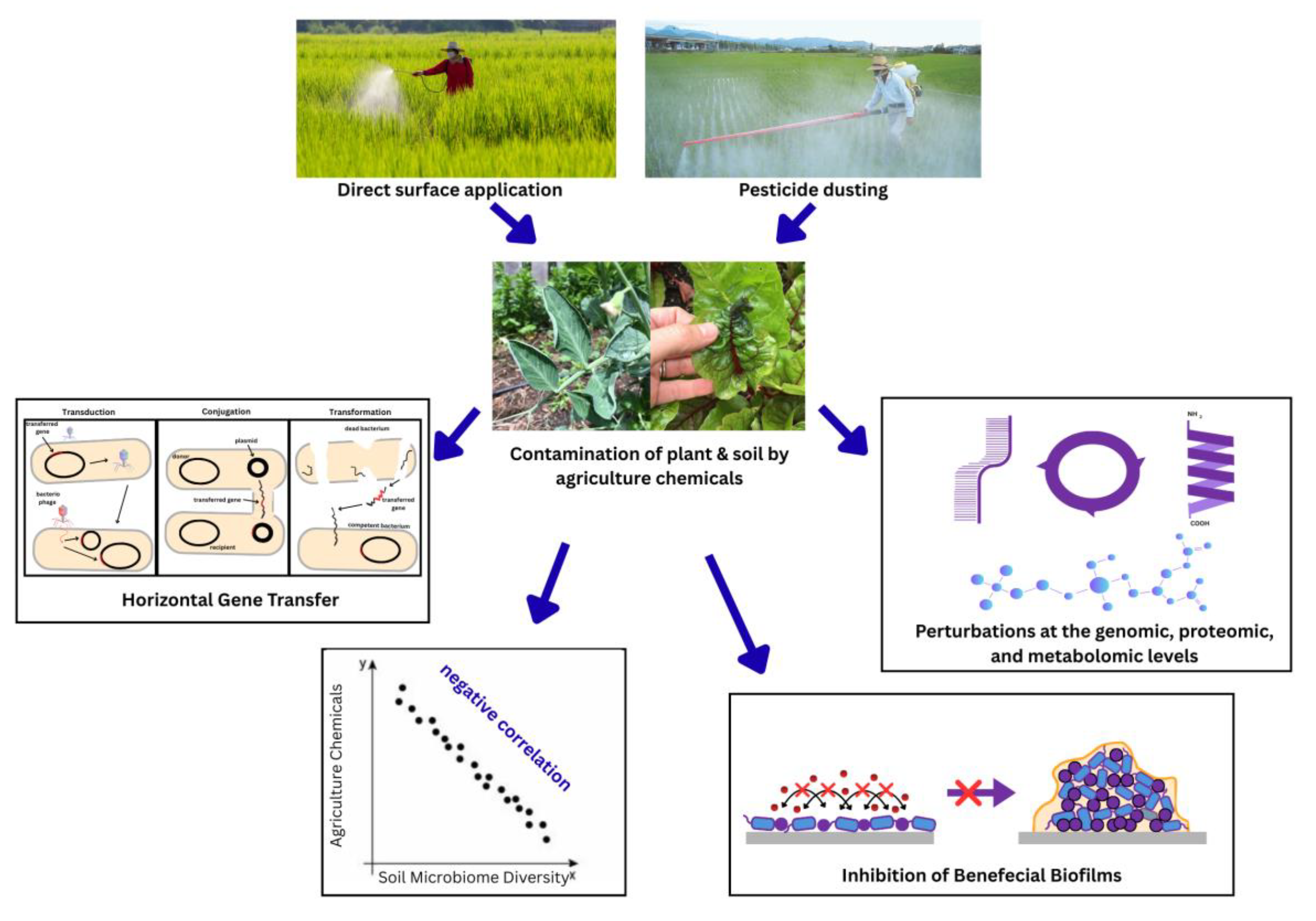

Figure 1 summarizes the impact of excessive use of agricultural chemicals on soil microbiome.

Effects on Beneficial Microflora and Microbial Biodiversity

Pesticides affect the beneficial microbiome and the microbiome diversity as a whole. Some microorganisms can be suppressed or eliminated while others can proliferate in the presence of pesticide, depopulating and impoverishing the microbiota in the agricultural soil. Another great concern is the inactivation of nitrogen-fixing and phosphorus-solubilizing microorganisms in pesticide contaminated soils (Cycon et al. 2007; Rathore et al. 2014). Nitrogen-fixing diazotrophs are also evidently the most sensitive to pesticides. On the other hand, some studies have indicated that some of the microbial populations may be using the applied pesticides as an energy source or nutrient and promote their growth. Under favorable circumstances, they can utilize pesticides as sources of energy in the form of carbon, sulfur, and electrons (Parte et al., 2017). This practice increases the abundance of some groups, yet leads to a decrease of general microbial diversity, even though it seems to increase the diversity of the functionalities in microbial communities by selecting those that may decay the chemicals. The specific effect is governed by numerous interrelated factors, including chemical structure of the pesticide, pesticide concentration, environmental parameters (pH, temperature, and others), soil moisture and microorganism species. Apart from the population dynamics, pesticides could also adversely influence the activity of certain useful microflora enzymes like dehydrogenase, urease and phosphatase that are involved in biochemical reactions and nutrient dynamic of the soil ecosystem (García and Hernández 1996; Jyot et al. 2015).

The Formation of Biofilm and Its Implications in Microbial Ecology

Biofilm is a complex, syntrophic population of microorganisms in which cells adhere to one another and, often, also to a surrogate surface; they are encased in an organic matrix, which is characterized by having extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and DNA (Yaacob et al. 2021; Johari et al. 2023; Hamdan et al. 2024). Such organized communities can develop on biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) surfaces and are a clearly differentiated physiological from the free-swimming (planktonic) form for microorganisms. The process of establishing a biofilm is initiated by reversible attachment and progressing into a more irreversible attachment typically aided by structures such as pili. Cell-cell communication (quorum sensing, QS) of the biofilm is essential for the colonization and development using measures (N-Acyl Homoserine Lactone, AHL) for the quorum sensing (Williams 2007). EPS matrix acts as a protective barrier retaining QS autoinducers thus assisting in the survival of the pathogen. In addition, the biofilm proteome serves as a rich source for discovering transformative benefits for sustainable agriculture. By comparing the proteomes of strong and weak biofilm formers, or of treated versus untreated biofilms, researchers can identify key proteins essential for biofilm integrity, reveal how the microbe establishes itself in the rhizosphere, identify the biosynthetic pathways which regulate plant growth, and understand complex plant-microbe interactions (Imam et al. 2017; Zawawi et al. 2020; Pudake et al. 2021; Abd Rashid et al. 2022; Isa et al. 2022).

Biofilms offer microorganisms considerable protection against antimicrobials and a variety of other adverse conditions. Nevertheless, the influence of pesticides for the development and maintenance of biofilms is considerable. For instance, specific synthetic (malathion) and natural (neem oil and pyrethrin) pesticides have been proved to inhibit the biofilm production of the beneficial bacteria Bacillus subtilis (Newton et al. 2020). This is a significant finding because B. subtilis biofilm on plant roots is crucial for symbiosis and inducing systemic resistance (ISR) induction in plants. If the results hold true in field conditions, dismantling these useful biofilms could leave pesticides defeating a plant’s native defenses and nutrient capabilities; that might also mean that plants would require more chemical help. On the converse, pesticides that promote the development of biofilms by pathogenic organisms cannot be made use of by certain extent to sponsor the diseased condition or perpetuation by undesirable organisms. For example, 2,4-D and Ridomil Gold, promote the production of biofilm in Clavibacter michiganensis sepedonicus as part of their plant-pathogenic repertoire (Perfileva et al., 2018). This represents a complex and often harmful interference with fundamental microbial ecological activities.

The widely used herbicide and antimicrobial compound glyphosate exerts opposite effects on bacterial biofilm formation and inhibition which could influence the establishment of microbes on surfaces in or on hosts, for example bee gut endosymbionts (Motta et al. 2024). Environmental variables, such as hydrodynamics (e.g. flow velocity in streams), might change the tolerance of autotrophic biofilm communities to herbicides, where the EPS matrix can act by absorbing the herbicide, and protecting biofilms from chemical stress. Polst et al. (2018) suggested that polar and nonpolar regions of EPS mediate hydrophobic adsorption, and electrostatic binding of herbicides, resembling processes documented for dissolved organic carbon in soils. These biofilms play important roles in many environmental processes such as the formation and degradation of organic matter, degradation of environmental contaminants and the cycling of important nutrients such as nitrogen, sulfur, other metals.

Contribution to Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

The challenge of resistance antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the ability of bacteria to resist the effects of antibiotics, is an urgent and pressing threat to global health (Safini et al. 2024; Yahya et al. 2025). Contemporary intensive crop and animal production industries are also recognized as major anthropogenic forces driving AMR and are primarily practiced in non-traditional health area. Intensive farming practices, such as heavy application of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, can be responsible for abiotic stress that induce loss of biodiversity and promote AMR attaining development and dispersion in soil and aquatic microbial communities (Graham et al. 2025). The use of antibiotics and antifungals as pesticides on plants or crops, as well as for livestock production, humanely causes the selection and spread of germs that are resistant to these antimicrobials. Transmission and spread of AMR can be achieved through human and animal waste, which is commonly applied as fertilizer on farms. Such waste can contain drug residues and resistant germs, which in turn contaminate the soil nearby and neighboring water sources.

Standard wastewater-treatment plants that are not oriented toward removing these resistant organisms and genes from sewage can disperse them into rivers and ocean waters, and back into human populations downstream (Pazda et al. 2019). The development of ‘super bugs’ from the successive development of resistance to multiple antibiotics is particularly worrisome. The link between use of agricultural chemicals to the global public health crisis of antimicrobial resistance is obvious. But it goes beyond the oft-reported story of antibiotics in livestock, to illuminate the influence of crop chemicals in promoting and spreading resistance genes throughout environmental microbiomes. This requires a One Health perspective, an acknowledgment that health of humans, animals and the environment are inextricably linked (Sleeman et al. 2017). Agricultural practices do not occur in a vacuum; they actively contribute to the global reservoir of resistant pathogens that can impact human populations, even ones geographically distant from agricultural areas.

Genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic perturbations

The alterations in ecosystem processes are the consequence of subtle, yet significant, influx perturbations at the genomic, proteomic and metabolomic level in the microbial community. From a genomic perspective, agrochemicals serve as potent drivers of natural selection, bringing about rapid restructuring of the genetic composition of the soil microbiome. Selective pressure resulting from chemical exposure, particularly antibiotics and pesticides, is a key driver of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in microbial communities. This gives advantage to the microbes containing the in-built resistant genes or acquired via the horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Paul et al. 2019). Plasmids, integrons, and transposons serve as vectors to transfer genes encoding for efflux pumps, detoxifying enzymes (cytochrome P450 monooxygenases that detoxify insecticides) or changed target sites (mutant EPSPS enzyme imparting glyphosate resistance) among bacteria (Harbottle et al. 2006). This fuels fast accumulation and spread of these resistance determinants within the soil resistome, which is a component of the microbiome genome. This represents a major public health issue, since soil may act as a reservoir of clinical antibiotic-resistant genes (Lee et al. 2018). According to Zhao et al. (2025), their metagenomic analysis confirmed that herbicide exposure did increase antibiotic resistance genes, particularly multimodal resistance genes, and that the correlation patterns indicated HGT as being an obligatory step in resistance dissemination.

The proteome, the complement of all proteins expressed by the microbiome, is indicative of the function of the microbiome in response to chemical stress. This is where the instruction manual of life is manifested. When exposed to a toxicant, microorganisms use energy to produce stress proteins, as a defense mechanism. For instance, the treatment of Escherichia coli with sublethal doses of pyrethroid and carbamate pesticides resulted in the induction of 17-20 stress proteins within 30 min as detected by 2D-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Asghar et al., 2006). Also, the abundance of 32 protein spots changed in Bacillus megaterium strain Mes11 in response to herbicide mesotrione, and 17 non-redundant proteins related to stress, metabolic, and storage responses were identified (Bardot et al., 2015). Energy is a finite resource. The significant investment in stress response proteins often comes at a cost. These are frequently implicated in protein synthesis for housekeeping activities such as nutrient transport, cell division, and central carbon metabolic pathways. This proteomic shift is in line with the often-reported transient overall degradation of microbial activity (e.g., respiration) after chemical application (Stenrod et al. 2013). Other important extracellular enzymes are directly inhibited by many agricultural chemicals. For example, glyphosate can reduce the activity of enzymes such as acid phosphatases, which play an important role in the cycling of phosphorus. Butmee et al., (2021) have shown that glyphosate could influence acid phosphatase activity by a reversible competitive-type mechanism, with glyphosate predicted through structure-based docking to bind the substrate binding pocket of the enzyme.

The metabolome is the most changeable level, influenced by real-time biochemical interactions and signal factors in the microbiome. Plant health and physiology are modified by herbicide treatment, thus directly affecting the quantity and composition of root exudates, the main energetic source for the rhizosphere microbiome. Kremer et al. (2002) reported chemical alterations of the root exudates due to the application of herbicides, since the application of glyphosate to soybeans increases carbohydrates and amino acids in the exudates of roots, and glyphosate itself can be measured in exudates at concentrations of >1000 ng plant⁻¹. Changes in exudate profile differentially fuel various microbial taxa rebuilding the community from the ground level. The healthy soil microbiome, using syntrophy, consumes the metabolic waste products of one microbe as food for another (Morris et al 2013). These finely adjusted metabolic connections can be broken by a chemical shock. For instance, a key fungal decomposer can be suppressed by a fungicide, starving the bacteria that depend on the simpler compounds the fungus exudes, an impasse that can point a cascade of metabolic troubles and a buildup of undecomposed organic matter (Fernández et al. 2016). Biosynthesis of plant growth hormones (auxins, gibberellins) produced by microbes can also be repressed leading to inhibition of plant growth. The synthesis of natural soil antibiotics by soil microbes (e.g., Streptomyces, Pseudomonas) that suppress plant pathogens can be impaired and diminish the natural biocontrol potential of the microbiome. In 2020, Gieske and Kinkel showed that application of N fertilizer led to higher soil C, N and total, and actinomycetes densities, and also actinomycetes producing antibiotics were 50% lower among culturable actinomycetes in fertilized vs. non-fertilized plots.

7. Approaches to Risk Reduction: Environment and Health

To minimize unforeseen environmental and health-related challenges caused by agricultural chemicals, there is need for farmer, regulatory agencies and consumers led program of action. Manufacturers' directions for the storage, application and disposal of chemicals should be strictly followed by farmers. This would involve reviewing Safety Data Sheets (SDS), a knowledge of product labels, and specialized training in chemical use. Before preparing does an even mix and the necessary dilution of pesticides out there in the open, where there is sufficient air for the proper In the open where plenty of air is available for the correct aiming purposes, just enough for is to be mixed for use should be prepared. Personal protection equipments (PPE) are mandatory to wear.

Chemical Selection and minimal exposure

The studies of chemical alternatives that have been conducted are valuable to get a first selection of the best and less ecotoxic products, and to favor less toxic products to existing ones or safer formulations in cases were available. there needs to be prevention of the chemicals from spraying on any non-target animals/plant. Keep treatments away from children, pets and toys until the chemicals have dried or you have completed the safe waiting period indicated on the label. Consumers can also minimize exposure to pesticide residues by washing and peeling fruits and vegetables.

Waste management and pest management in combination

It is essential to take care of the chemical waste. This might include triple-rinsing, puncturing or other means of making empty containers unusable and safe disposal of rinsate (rinse water and remnants of product). An approach based on integrated pest management (IPM) with emphasis on reducing reliance on chemical pesticides through a judicious use of biological, cultural and mechanical methods supplemented by selective use of chemicals (Tiwari, 2024). Activation of non-chemical control including the used of beneficial bacteria, hand weeding, mulches, traps, crop rotation, cover crop, and plant spacing can offer considerable reductions for chemical control. Tools such as satellite surveillance, artificial intelligence and automatic sprays in the field allow farmers to spray pesticides when and where the pests appear. It’s the most effective by far and uses only a small fraction of the runoff and chemicals.

8. Future Directions and Recommendations

The direction of agriculture is beaded in such a way where creative solutions will be essential for sustainability vs. productivity. This will involve advances in drug development, policy development and analytical capacity. Growing demand for sustainable agriculture is advancing several new and safer green agricultural chemicals. That’s a technological leapfrog where agriculture has the opportunity to skip over some of the worst mistakes of chemical-heavy agriculture if such advanced, precision-informed solutions become the norm.

Biopesticides

Biopesticides include natural substances, such as plants, bacteria, fungi, and minerals, which are eco-friendly alternatives to synthetic chemical pesticides. Define Biopesticides are predominantly of ecological nature, providing an important source to reduce pests and diseases, using some biologically occurring organisms or natural products as in an ecologically friendly way (Mazid et al. 2011). In contrast to popular belief, biopesticides have a specific action that is contrary to broad spectrum pesticides and can have in most cases little or no impact on the non-target organisms. Their degradability leads to low residual toxicity in soil and water and hence they form an integral part of integrated pest management (IPM) systems. Microbial bio-pesticides, like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), have narrow spectrum of influence and pose little or no risk of toxicity, and has been established to manage pests satisfactorily for non-target organisms’ retention. According to Melo et al. (2016), Bt leads to an osmotic imbalance because of pore formation in the cell membrane and cell death is forced by the opening of ion channels. Bt releases diverse insecticidal pore-forming toxins that lead to the death of the insects, as those are the case of the Cry proteins that degrade epithelial cells of insect gut larvae (Pacheco et al. 2023).

Nanotechnology in Pesticides

Nanotechnology is the manipulation of pesticides at a nano-dimensions to increase their accuracy and effectiveness. The basic concept is to improve the solubility, controlled release, and moderation of the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents, therefore minimizing the dosage of drugs needed and off-target effects. Nano-encapsulations prevent the pesticides from photo and thermal degradation, making it more effective (Kumar et al. 20219). Moreover, it is possible to design nanomaterials that only release active ingredients under environmental-based stimuli (e.g., pH, enzymes), thereby reducing environmental undesirable effects and increasing efficacy toward pests. Organophosphorous and carbamate pesticides can be successfully detected by graphene and their derivatives via both enzymatic and non-enzymatic strategies with high sensitivity and selectivity (Singh et al., 2019). The responsive mechanisms include changes in the structure and/or the degradation of nanocarriers, the breakage of bonds between therapeutics and carriers, or the introduction of certain responsive groups including photolabile groups and disulfide bonds (Shen et al., 2023). This contributes to improve efficiency of pesticides, reduce the number of applications, lessen the risks of environmental contamination and is adapted to precision agriculture objectives (Camara et al., 2019).

Microbial Inoculants

Microbial inoculants are formulations of selected beneficial microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi that promote plant growth or suppress disease. The mechanism works in two principal mechanisms; the first is through competitive exclusion mechanisms in which these organisms make competition with pathogenic organisms for nutrition and space, and the second one is through the promotion of systemic resistance in the plant by these organisms (Das et al. 2022). Some inoculants, such as mycorrhizal fungi, enhance nutrient uptake lessening the need for chemical fertilizers. Microbial inoculants also promote sustainable agriculture by improving soil health, as they reduce the risk of chemical runoff and soil erosion.

RNA Interference (RNAi) Technology

RNAi enables targeting of a particular gene in a pest or pathogen, knocking it down without affecting the non-target organism. The principle is based on the application of double stranded RNA (dsRNA) that induces gene silencing of pest genes after pest intake. RNAi can control the insect’s species-specifically, whereas the broad-spectrum pesticides have the adverse effects to the environment. RNAi has been shown to be a promising tool to manage different agri-food pests (i.e., insect pests, pathogens, and nematodes) (Zotti et al., 2018). However, practical issues such as delivery tools, as well as RNA stability in the environment remained as hurdles preventing large-scale implementation.

Pheromone-Based Insecticides

Pheromones are natural chemicals insects use to communicate; the synthetic forms either interrupt mating patterns or attract pests into traps. The main mode is competitive attraction or false plume following in which males are attracted but fail to mate females due to higher dose of pheromone source (Stelinski, 2007). Pheromone traps and mating disruption practices reduce pest populations for the long term, reducing the chance of resistance and maintaining beneficial insects such as pollinators. It has been effectively applied in the control of codling moths in apple orchards, showing his practical and environmental advantages (Witzgall et al., 2008).

Genetic Engineering

Genetic modification alters crop DNA to be more resistant to pest, disease or herbicide conditions instead of relying on chemical inputs. This has led to a reduction in pesticide application, which has been favorable to non-target organism populations and in minimizing water pollution (Mannion et al., 2013). The concept is to insert genes for inherent pest resistance or enhanced environmental sturdiness. Although disputed, the use of GM crops can reduce insecticides use, but environmental and regulatory issues are essential.

AI-Powered Advisory Systems

AI-run propositions that process and study data (for the weather, soil and pests’ outbreak) to propose the best timing and proportion for the application of chemicals. The guiding strategy is precision decision-making that minimizes overuse through predictive analytics and real-time monitoring. Farmers receive tailored recommendations, and the system has effectively compressed the information on chemical input and crop protection. Through advanced analytics and machine learning, these platforms can save tons of pesticide and fertilizers for the same crop health and get tons of yield. For example, AI-based spray timing and variable scale application maps have enabled 30% reduction in fungicide application rates in European grain cereals (Shankar et al., 2020).

Satellite-Based Crop Monitoring

Satellites provide high-resolution images early on to detect pest attacks, identify nutrient deficiencies and determine water stress. At stake is a practice called proactive intervention, in which issues are spotted before they develop but are not yet full irregularity, allowing targeted pesticide to be used instead of blanket spraying. This results in the reduced use of chemicals by the grower and indirectly environmentally load and an improved yield. Worldview-2 and -3 satellites can identify vascular plant diseases with accuracies ranging between 0.63-0.83 except for those in early phase (Poblete et al., 2023).

Automated Spraying Systems

Robotic, sensor-laden sprayers apply agrochemicals only where they are necessary, using computer vision and AI to spot pests or weeds. The concept is target, and with it comes fewer applications, less drift, less chemical waste. These systems are less time and cost consuming and the eco exposure to the hazardous material is minimized. Field trials have demonstrated good weed cover and high detection performance, where killing efficiency is also up to ∼90–93% (Upadhyay et al., 2024).

Drone Technology

Because the drones are so accurate when they spray from the air, they can reach hard-to-access areas high in the canopy of the forest, and they can avoid exposing humans as much to chemicals. It’s a combination of remote sensing and targeted application where drones equipped with multispectral cameras read the problem zones and sprayers target only those areas with chemicals. This reduces the total volume of chemicals applied and associated running costs to less than conventional processing. Smallholder farmers and vector control would benefit from drones as they can cover areas efficiently and provide access to inaccessible regions such as wetlands and steep vineyards (Matthews, 2021).

By combining these approaches, agriculture systems may be shifted to less dependency on chemicals, lower environmental risks and more sustainable crop production. The applicability of these approaches is country dependent (the economic setting, the nature of production processes and the prevailing environmental condition). We can foresee that those high-income countries with a mature technological infrastructure (e.g., U.S.A., Germany) may focus their re-search and development efforts more on AI-based advisory systems, auto-mated spraying, and drone concerning precision agriculture, whilst middle income countries (e.g., Brazil, India) might more acutely use cost-effective biopesticides, microbial inoculants, and pheromone-based control alternatives which require little investments to reduce chemical reliance (Jiang et al. 2025). Microbial inoculants and smart formulations could be much more affordable and better adapted to small-holder agriculture in resource-poor settings, such as sub-Saharan Africa, where there are also fewer resources for other strategies. Semi-desert regions that are deprived of water, such as the Middle East, could rely on satellite-based monitoring and nanotechnology-based slow-release pesticides to minimize resource use, while tropical countries struggling with prevailing pests may use RNAi or genetic manipulation to focus resistance efforts. As such, strategy may vary on a country’s financial capability, access to technology, climate and pest pressures and there is a need for unique strategy to be tailor made for each country to deliver sustainable and efficient agrochemicals management.

Of the strategies reviewed here, biopesticides are the most widely utilised because of their affordability, regulatory approval, and environmental profile (Marrone 2007). The worldwide market of biopesticides is expanding at a fast pace and its annual growth rates are estimated in the range of 10-20% (Marrone, 2019). Since biopesticides require less amount of inputs to achieve similar levels of control, and also applications are reduced in number and frequency, resistance management costs and the expenses for complying with regulatory restrictions are substantially reduced. They further reduce risks by cutting environmental clean-up costs with biodegradability, reducing health costs from harmful residues, and minimizing crop losses by increasing plant immunity and accelerating yield stability. According to Soyel et al. (2022), botanical pesticides containing alkaloids, tannins, steroids, phenols, flavonoids, terpenes have insecticidal activity at a far lower cost compared to that of the synthetic insecticides, biodegradable, environmentally safe and safe for human. This indicates that biopesticides are economically viable and environmentally friendly as compared with synthetic pesticides. Biopesticides are even more attractive compared to genetic modification, drone spraying, and AI advisory platforms because the logistics were not nearly as complex because they are ready to go, they are less expensive, and the regulators are used to them. Unlike biotechnology, heavily regulated by GMO rules which involves high R&D costs, biopesticides has been shown to increase crop yields by 15-30% and to reduce the risk of crop loss from 60-70% to 33% when compared to chemical pesticides (Arjjumend et al., 2021). Together, biopesticides are a scalable, sustainable approach to farming across all types of cultivation, from smallholder farming in the developing world to large-scale organic in the developed world.

9. Conclusion

This chapter illustrates the model of modern farming as contradictory and complex. The agricultural chemicals have certainly contributed significantly to our capacity to attain global food security and enhance overall agricultural productivity to historically unprecedented levels, thus facilitating high-yielding agriculture that feeds an expanding human population. But all this change has come at a deep and highly entangled cost to the environment and human health. Indeed, agrochemical use has alleviated short-term food insecurity, but at the same time has trapped agriculture in a form of unsustainable, non-renewable, and carbon-intensive energy regime. Its environmental impact is far reaching including rampant soil deterioration, extensive water pollution (dumped through run-off and leaching), and to air quality (through volatile emission of toxic substances). These effects are inter-associated, with the above described ‘pollution multiplier effect’, wherein pollution in one environmental compartment inevitably recruits others, demanding a unified approach in remediating them. The effect is devastating to the entire community of microorganisms, as well as the impact of such an action. Pesticides can “engineer” microbial communities by gentle culling of microbial diversity and driving selection forces in favor of resistant or opportunistic microbial species. This unintended ecological engineering can corrupt essential soil microbial processes and diminish ecosystem resistance. The shift of beneficial activities of microorganisms including biofilm formation by pesticides may also compromise natural plant defense and nutrient recovery. Importantly, the situation highlights a direct and startling connection between intensive agricultural practices and the global public health burden represented by AMR and underscores the “One Health” necessity that merge environment, animal, and human health.

Facing such an array of challenges requires a fit solution, operating in a balanced and dynamic fashion. It involves change from "control" to "management" of pests, something that can be seen in the emerging concept of the Integrated Pest Management (IPM). Efforts of amelioration should also include ongoing development for safer, eco-friendly agrochemicals including biopesticides, microbials and nanotechnology-based delivery systems. Precision agriculture tools, such as AI-powered advisory services and automated spraying, provide a “technological leapfrog” to use resources better and reduce chemicals. At the same time, policy instruments need to shift from pure detriments to enablers, offering incentives and skill development in favor of sustainable transitions.

10. Acknowledgement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepSeek and Grammarly to reduce spelling and grammar errors. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Abd Rashid, S. A., Yaacob, M. F., Anuar, N. R. T., Johari, N., Kamaruzaman, A. N. A., Yunus, N. M. & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. 2022. A combination of in silico subtractive and reverse vaccinology approaches reveals potential vaccine targets in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 17(1): 99-109. [CrossRef]

- Alavanja, M. C., Ross, M. K., & Bonner, M. R. (2013). Increased cancer burden among pesticide applicators and others due to pesticide exposure. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 63(2), 120-142. [CrossRef]

- Alder, L., Greulich, K., Kempe, G., & Vieth, B. (2006). Residue analysis of 500 high priority pesticides: better by GC–MS or LC–MS/MS?. Mass spectrometry reviews, 25(6), 838-865. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J. W., & Goodacre, R. (2010). An introduction to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry instrumentation applied in plant metabolomic analyses. Phytochemical Analysis: An International Journal of Plant Chemical and Biochemical Techniques, 21(1), 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Arjjumend, H., Koutouki, K., & Neufeld, S. (2021). Comparative advantage of using bio-pesticides in Indian agro-ecosystems. Ecosystems, 1-15.

- Asghar, M. N., Ashfaq, M., Ahmad, Z., & Khan, I. U. (2006). 2-D PAGE analysis of pesticide-induced stress proteins of E. coli. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry, 384(4), 946-950. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. C., Chang, Y. Y., Hussain, M., Lu, B., Zhang, J. P., Song, X. B., ... & Pei, D. (2020). Soil chemical and microbiological properties are changed by long-term chemical fertilizers that limit ecosystem functioning. Microorganisms, 8(5), 694. [CrossRef]

- Bardot, C., Besse-Hoggan, P., Carles, L., Le Gall, M., Clary, G., Chafey, P., ... & Batisson, I. (2015). How the edaphic Bacillus megaterium strain Mes11 adapts its metabolism to the herbicide mesotrione pressure. Environmental Pollution, 199, 198-208. [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N., & Chauhan, P. S. (2020). Excessive and disproportionate use of chemicals cause soil contamination and nutritional stress. In Soil contamination. IntechOpen.

- Bretveld, R. W., Thomas, C. M., Scheepers, P. T., Zielhuis, G. A., & Roeleveld, N. (2006). Pesticide exposure: the hormonal function of the female reproductive system disrupted?. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 4(1), 30. [CrossRef]

- Butmee, P., Tumcharern, G., Songsiriritthigul, C., Durand, M. J., Thouand, G., Kerr, M., ... & Samphao, A. (2021). Enzymatic electrochemical biosensor for glyphosate detection based on acid phosphatase inhibition. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 413(23), 5859-5869. [CrossRef]

- Camara, M. C., Campos, E. V. R., Monteiro, R. A., do Espirito Santo Pereira, A., de Freitas Proença, P. L., & Fraceto, L. F. (2019). Development of stimuli-responsive nano-based pesticides: emerging opportunities for agriculture. Journal of nanobiotechnology, 17(1), 100. [CrossRef]

- Cassán, F., Vanderleyden, J., & Spaepen, S. (2014). Physiological and agronomical aspects of phytohormone production by model plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) belonging to the genus Azospirillum. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 33(2), 440-459. [CrossRef]

- Casida, J. E., & Durkin, K. A. (2013). Neuroactive insecticides: targets, selectivity, resistance, and secondary effects. Annual review of entomology, 58(1), 99-117. [CrossRef]

- Cloyd, R. A., Bethke, J. A., & Cowles, R. S. (2011). Systemic insecticides and their use in ornamental plant systems. Floriculture and Ornamental Biotechnol, 5, 1-9.

- Cycon, M., & Piotrowska-Seget, Z. (2007). Effect of selected pesticides on soil microflora involved in organic matter and nitrogen transformations: pot experiment. Polish journal of ecology, 55(2), 207-220.

- Das, P. P., Singh, K. R., Nagpure, G., Mansoori, A., Singh, R. P., Ghazi, I. A., ... & Singh, J. (2022). Plant-soil-microbes: A tripartite interaction for nutrient acquisition and better plant growth for sustainable agricultural practices. Environmental Research, 214, 113821. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D., & Gu, F. X. (2012). Materials for sustained and controlled release of nutrients and molecules to support plant growth. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 60(4), 870-876. [CrossRef]

- Dupeux, F., Santiago, J., Betz, K., Twycross, J., Park, S. Y., Rodriguez, L., ... & Márquez, J. A. (2011). A thermodynamic switch modulates abscisic acid receptor sensitivity. The EMBO journal, 30(20), 4171-4184. [CrossRef]

- Dureja, P., Singh, S. B., & Parmar, B. S. (2015). Pesticide maximum residue limit (MRL): background, Indian scenario. Pesticide Research Journal, 27(1), 4-22.

- Fernández, D., Tummala, M., Schreiner, V. C., Duarte, S., Pascoal, C., Winkelmann, C., ... & Schäfer, R. B. (2016). Does nutrient enrichment compensate fungicide effects on litter decomposition and decomposer communities in streams?. Aquatic Toxicology, 174, 169-178. [CrossRef]

- García, C., & Hernández, T. (1996). Effect of bromacil and sewage sludge addition on soil enzymatic activity. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 42(1), 191-195. [CrossRef]

- Gieske, M. F., & Kinkel, L. L. (2020). Long-term nitrogen addition in maize monocultures reduces in vitro inhibition of actinomycete standards by soil-borne actinomycetes. FEMS microbiology ecology, 96(11), fiaa181. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.C.; Zhang, Y.H.; Gao, W.B.; Pan, L.; Zhu, H.J.; Cao, F. Absolute Configurations and Chitinase Inhibitions of Quinazoline-Containing Diketopiperazines from the Marine-Derived Fungus Penicillium polonicum. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 479. [CrossRef]

- Graham, M. E., Wilson, B. A., Ramkumar, D., Rosencranz, H., & Ramkumar, J. (2025). Unseen Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance: The Role of Industrial Agriculture and Climate Change in This Global Health Crisis. Challenges, 16(2), 22. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, H. F., Ross, E. E. R., Jalil, M. T. M., Hashim, M. A., & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. (2024). Antibiofilm efficacy and mode of action of Etlingera elatior extracts against Staphylococcus aureus. Malaysian Applied Biology, 53(1), 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Harbottle, H., Thakur, S., Zhao, S., & White, D. G. (2006). Genetics of antimicrobial resistance. Animal biotechnology, 17(2), 111-124. [CrossRef]

- Harner, T., Shoeib, M., Diamond, M., Stern, G., & Rosenberg, B. (2004). Using passive air samplers to assess urban− rural trends for persistent organic pollutants. 1. Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides. Environmental science & technology, 38(17), 4474-4483.

- Hess, F. D. (2018). Herbicide effects on plant structure, physiology, and biochemistry. In Pesticide interactions in crop production (pp. 13-34). CRC Press.

- Imam, J., Shukla, P., Prasad Mandal, N., & Variar, M. (2017). Microbial interactions in plants: perspectives and applications of proteomics. Current Protein and Peptide Science, 18(9), 956-965. [CrossRef]

- Isa, S. F. M., Hamid, U. M. A., & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. (2022). Treatment with the combined antimicrobials triggers proteomic changes in P. aeruginosa-C. albicans polyspecies biofilms. ScienceAsia, 48 (2): 215-222.

- Jiang, L., Xu, B., Husnain, N., & Wang, Q. (2025). Overview of Agricultural Machinery Automation Technology for Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy, 15(6), 1471. [CrossRef]

- Johari, N. A., Aazmi, M. S., & Yahya, M. F. Z. R. (2023). FTIR spectroscopic study of inhibition of chloroxylenol-based disinfectant against Salmonella enterica serovar Thyphimurium biofilm. Malaysian Applied Biology, 52(2), 97-107. [CrossRef]

- Jyot, G., Mandal, K., & Singh, B. (2015). Effect of dehydrogenase, phosphatase and urease activity in cotton soil after applying thiamethoxam as seed treatment. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 187(5), 298. [CrossRef]

- Kakimoto, T. (2003). Perception and signal transduction of cytokinins. Annual review of plant biology, 54(1), 605-627. [CrossRef]

- Kira O, Linker R, Dubowski Y. Estimating drift of airborne pesticides during orchard spraying using active Open Path FTIR. Atmos Environ. 2016 Oct 1;142:264–70. [CrossRef]

- Keklik M, Golge O, González-Curbelo MÁ, Kabak B. Pesticide residues in peaches and nectarines: Three-year monitoring data and risk assessment. Food Control. 2025 May 1;171:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kremer, R., Means, N., & Kim, S. (2005). Glyphosate affects soybean root exudation and rhizosphere micro-organisms. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 85(15), 1165-1174. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K., Balbudhe, S., & Singh, A. (2021). Effects of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) on Human Health. In Persistent Organic Pollutants (pp. 91-122). CRC Press.

- Kundoo, A. A., Dar, S. A., Mushtaq, M., Bashir, Z., Dar, M. S., Gul, S., ... & Gulzar, S. (2018). Role of neonicotinoids in insect pest management: A review. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud, 6(1), 333-339.

- Lam, H. M., Coschigano, K. T., Oliveira, I. C., Melo-Oliveira, R., & Coruzzi, G. M. (1996). The molecular-genetics of nitrogen assimilation into amino acids in higher plants. Annual review of plant biology, 47(1), 569-593. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., Park, K. S., Jeon, J. H., & Lee, S. H. (2018). Antibiotic resistance in soil. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 18(12), 1306-1307. [CrossRef]

- Lehotay, S. J. (2001, March). Need for rapid screening methods to detect chemical residues in food. In Photonic Detection and Intervention Technologies for Safe Food (Vol. 4206, pp. 112-122). SPIE.

- Liu, Y., Lan, X., Hou, H., Ji, J., Liu, X., & Lv, Z. (2024). Multifaceted ability of organic fertilizers to improve crop productivity and abiotic stress tolerance: Review and perspectives. Agronomy, 14(6), 1141. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J., Zhou, J. J., & Zhang, J. Z. (2018). Aux/IAA gene family in plants: molecular structure, regulation, and function. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(1), 259. [CrossRef]

- Ma JK, Wei SL, Tang Q, Huang XC. A novel enrichment and sensitive method for simultaneous determination of 15 phthalate esters in milk powder samples. LWT. 2022 Jan 1;153:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mannion, A. M., & Morse, S. (2012). Biotechnology in agriculture: agronomic and environmental considerations and reflections based on 15 years of GM crops. Progress in Physical Geography, 36(6), 747-763. [CrossRef]

- Marrone, P. G. (2007). Barriers to adoption of biological control agents and biological pesticides. CABI Reviews, (2007), 12-pp.

- Marrone, P. G. (2019). Pesticidal natural products–status and future potential. Pest Management Science, 75(9), 2325-2340. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G. A. (2021). The role for drones in future aerial pesticide applications. Outlooks on Pest Management, 32(5), 221-224. [CrossRef]

- McBeath, T. M., Armstrong, R. D., Lombi, E., McLaughlin, M. J., & Holloway, R. E. (2005). Responsiveness of wheat (Triticum aestivum) to liquid and granular phosphorus fertilisers in southern Australian soils. Soil Research, 43(2), 203-212. [CrossRef]

- Melo, A. L. D. A., Soccol, V. T., & Soccol, C. R. (2016). Bacillus thuringiensis: mechanism of action, resistance, and new applications: a review. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 36(2), 317-326. [CrossRef]

- Menegat, S., Ledo, A., & Tirado, R. (2022). Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 14490. [CrossRef]

- Mganga, N. D., & Mwampaya, M. H. (2025). Influence of UREA and NPK Fertilizers on Selected Soil Properties that Could Control Nutrient Uptake in Local Maize Variety in a Semi-Arid Area of Tanzania. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 29(2), 459-465. [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou, S., & Abdollahi, M. (2018). The link of organophosphorus pesticides with neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases based on evidence and mechanisms. Toxicology, 409, 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Motta, E. V., de Jong, T. K., Gage, A., Edwards, J. A., & Moran, N. A. (2024). Glyphosate effects on growth and biofilm formation in bee gut symbionts and diverse associated bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 90(8), e00515-24. [CrossRef]

- Mukiibi S Ben, Nyanzi SA, Kwetegyeka J, Olisah C, Taiwo AM, Mubiru E, et al. Organochlorine pesticide residues in Uganda’s honey as a bioindicator of environmental contamination and reproductive health implications to consumers. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021 May 1;214:1–12.

- Newton, R., Amstutz, J., & Patrick, J. E. (2020). Biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis is altered in the presence of pesticides. Access microbiology, acmi000175. [CrossRef]

- Ni, B., Xiao, L., Lin, D., Zhang, T. L., Zhang, Q., Liu, Y., ... & Zhu, Y. G. (2025). Increasing pesticide diversity impairs soil microbial functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(2), e2419917122. [CrossRef]

- Oh, B. Y. (2000). Assessment of pesticide residue for food safety and environment protection. 농약과학회지, 4(4), 1-11.

- Orozco-Mosqueda, M. D. C., Santoyo, G., & Glick, B. R. (2023). Recent advances in the bacterial phytohormone modulation of plant growth. Plants, 12(3), 606. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, S., Gómez, I., Peláez-Aguilar, A. E., Verduzco-Rosas, L. A., García-Suárez, R., do Nascimento, N. A., ... & Bravo, A. (2023). Structural changes upon membrane insertion of the insecticidal pore-forming toxins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis. Frontiers in Insect Science, 3, 1188891. [CrossRef]

- Pang, F., Li, Q., Solanki, M. K., Wang, Z., Xing, Y. X., & Dong, D. F. (2024). Soil phosphorus transformation and plant uptake driven by phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15, 1383813. [CrossRef]