Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Scientific Basis

2.1. Bioelectric Signatures of Breast Cancer

- Membrane Potential: Malignant cells (e.g., MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, SK-BR-3) exhibit depolarized resting potentials (-10 to -30 mV) compared to normal mammary epithelial cells (-70 to -90 mV), driven by overexpressed voltage-gated sodium channels and altered ion transport [Salem et al., 2023; Fraser et al., 2005]. This depolarization enhances cellular excitability and proliferation, creating a detectable bioelectric signature.

- Conductivity and Permittivity: Malignant breast tissues have 3–5 times higher conductivity (0.8–1.5 S/m) and permittivity due to increased water content, sodium ions, and disrupted cellular architecture [Meani et al., 2023; Guiseppi-Elie, 2022]. These properties cause distinct impedance changes at 10 kHz–1 MHz, ideal for EIS.

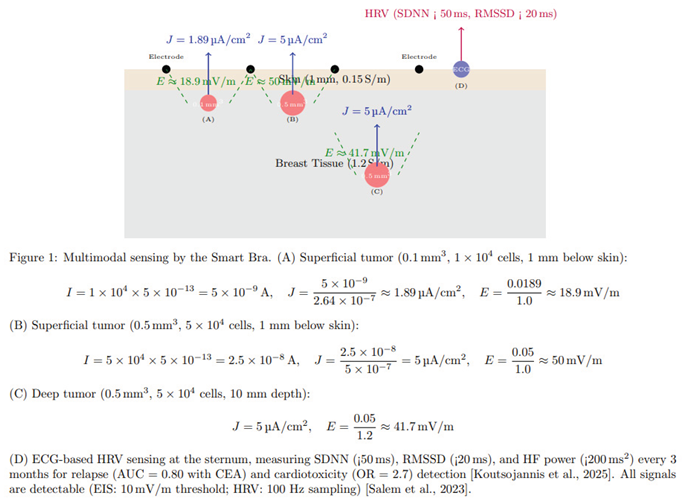

- Electric Field Generation: Tumors as small as 0.5 mm3 (~5 × 104 cells) produce a current density of 2–8 μA/cm2, generating electric fields of ~10–41.7 mV/m, detectable by high-sensitivity EIS [Kuzmin et al., 2025]. The calculation for a tumor of 5 × 104 cells is shown in Figure 1.

- Forward Modeling and Detectability Analysis: In the revised formulation of this work, the reported 0.1–0.5 mm3 tumor range is presented as a model-based detectability estimate rather than a clinically demonstrated diagnostic threshold. A finite-element forward model of a layered breast geometry (skin, adipose, glandular tissue, and parenchyma) was developed using frequency-dependent conductivity and permittivity values reported in ex-vivo studies. For each drive/measure pattern of the 3 × 4 electrode array, spatial sensitivity distributions were computed and the perturbation in complex impedance produced by inclusions of varying size, depth, and contrast was evaluated. Instrumentation constraints were incorporated via a variability model including contact-impedance modulation, electrode polarization, analog front-end noise, and phase uncertainty. Detectability is therefore expressed as signal-to-noise ratio and receiver-operating characteristics as a function of lesion depth and volume, rather than as a single deterministic limit. These findings inform the engineering target of 0.1–0.5 mm3 under modeled conditions; the clinical detection limit will be determined prospectively in the validation study.

- HRV Signatures: Reduced HRV (SDNN < 50 ms, RMSSD < 20 ms, HF < 200 ms2) correlates with advanced BC stages (III–IV), higher CEA, and worse prognosis (HR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.48–0.79). Chemotherapy reduces SDNN by ~20%, predicting cardiotoxicity (OR = 2.7). RMSSD < 20 ms predicts relapse, particularly in ER+ BC [Koutsojannis et al., 2025; Luna-Alcala et al., 2024; Ding et al., 2023].

- Tumor Location: 60–70% of tumors occur in the upper-outer quadrant, 10–15% superficial, enhancing EIS detectability [Berg et al., 2008].

2.2. Limitations of Current Diagnostic Approaches

- Mammography: Detects tumors ≥1000 mm3 (~10 mm diameter), with 70–85% sensitivity and 80–90% specificity. Its performance drops to 30–50% in dense breasts due to tissue overlap [Kerlikowske et al., 2011].

- Ultrasound: Detects ~65.4 mm3 (~5 mm diameter), with 80–90% sensitivity, but is operator-dependent and has moderate specificity (70–85%) [Kolb et al., 2002].

- MRI: Detects ~4.2 mm3 (~2 mm diameter), with 90–95% sensitivity, but is costly and requires gadolinium contrast, limiting its use for routine screening [Kuhl et al., 2007].

- Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT): Detects ~14.1 mm3 (~3 mm diameter), with 75–85% sensitivity and 60–80% specificity, limited by low spatial resolution [Mansouri et al., 2020].

- Microwave Imaging: Detects ~33.5 mm3 (~4 mm diameter), with 70–85% sensitivity and 65–80% specificity, constrained by complex reconstruction algorithms [Meaney et al., 2012].

- Emerging Modalities: Photoacoustic imaging (~4.2–14.1 mm3), thermography (~65.4 mm3), and wearable ultrasound (~14.1 mm3) offer improved sensitivity but lack specificity or electrophysiological data [Valluru et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023]. The smart bra’s target detection limit of 0.5 mm3 is 8–2000 times smaller than these modalities, enabling earlier detection critical for improving outcomes.

- HRV Studies: Heterogeneous protocols (5-minute vs. 24-hour ECG) and confounders (e.g., beta-blockers) limit comparability. No direct vagal-cytokine measurements exist [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

- Wearables: Ultrasound patches lack HRV integration.

2.3. Advancements Supporting the Proposed Approach

- EIS Sensitivity: Studies demonstrate EIS’s ability to detect tumors ≥0.5 mm3 in phantoms and small clinical cohorts, leveraging conductivity differences amplified by MNP-coated electrodes targeting biomarkers like HER2 or EGFR [Zheng et al., 2019; Kuzmin et al., 2025].

- AI Integration: A space-time attention neural network achieved 98.5% sensitivity and 97% specificity on EIS data, supporting the project’s AI-driven approach [Yu et al., 2025]. GAN augmentation addresses limited datasets, improving classification robustness [McDermott et al., 2024].

- Wearable Technology: Precedents like the TransScan TS2000 (72.2% sensitivity) and MIT’s conformal ultrasound bra (cUSBr-Patch) confirm the feasibility of wearable diagnostics [Du et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023]. The smart bra advances these with MNP-enhanced electrodes and multimodal sensing.

3. Related Work

3.1. Traditional Imaging Modalities

- Mammography: As the cornerstone of breast cancer screening, mammography relies on X-ray imaging to detect calcifications and masses. However, its resolution limits detection to ~1000 mm3, and dense breast tissue reduces sensitivity to 30–50% [Kerlikowske et al., 2011]. False positives lead to unnecessary biopsies, increasing patient anxiety and healthcare costs.

- Ultrasound: Used as an adjunct, ultrasound detects tumors ~65.4 mm3, with improved sensitivity in dense breasts (80–90%). However, its operator dependency and moderate specificity (70–85%) limit its utility for micro-tumors [Kolb et al., 2002].

- MRI: Contrast-enhanced MRI achieves high sensitivity (90–95%) for tumors ~4.2 mm3, making it ideal for high-risk women. However, its high cost, long scan times, and gadolinium-related risks restrict its use for routine screening [Kuhl et al., 2007].

3.2. Emerging Electrophysiological and Wearable Technologies

- Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT): EIT maps tissue conductivity using electrode arrays, detecting tumors ~14.1 mm3 with 75–85% sensitivity and 60–80% specificity. Its low resolution and complex reconstruction algorithms limit clinical adoption [Mansouri et al., 2020; Haeri et al., 2016].

- Microwave Imaging: This modality exploits dielectric differences, detecting tumors ~33.5 mm3 with 70–85% sensitivity. Machine learning improves performance, but resolution and validation challenges persist [Meaney et al., 2012; Piras et al., 2023].

- Bioimpedance Spectroscopy (BIS): BIS, a precursor to EIS, measures tissue impedance at multiple frequencies. Guiseppi-Elie (2022) highlights its ability to detect molecular changes in tissues, achieving 96.6% sensitivity for melanoma but lower specificity for breast cancer (67–82%) due to tissue heterogeneity [Du et al., 2020].

- Wearable Ultrasound: MIT’s cUSBr-Patch detects tumors ~14.1 mm3 with ~90% sensitivity, using conformal piezoelectric transducers. However, it lacks electrophysiological data and requires bulky components, limiting daily wear [Wang et al., 2023].

- Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensors: Zheng et al. (2019) developed an EIS-based biosensor with MNP-coated electrodes, detecting low quantities of breast cancer cells (MCF-7, SK-BR-3) by targeting HER2/EGFR. This approach enhances sensitivity but is not yet wearable.

- HRV in Cancer: Reduced HRV (SDNN < 50 ms, RMSSD < 20 ms) predicts relapse and cardiotoxicity in BC, with 3-month monitoring enhancing outcomes [Koutsojannis et al., 2025; Luna-Alcala et al., 2024].

- Wearables: MIT ultrasound patch and IcosaMed SmartBra lack ECG-based HRV.

3.3. AI in Cancer Diagnostics

- Machine Learning: Random forest and ANN models improve specificity for prostate cancer biomarkers (>99%) [Shajari et al., 2023]. Salem et al. (2023) report 92% accuracy using LSTM for EIS-based breast tissue classification, emphasizing features like I0 and DR.

- Deep Learning: Yu et al. (2025) achieved 98.5% sensitivity and 97% specificity with a space-time attention neural network (STABFNet) on EIS data, highlighting the power of attention mechanisms for multi-frequency analysis.

- Data Augmentation: GANs address limited datasets, improving classification robustness for bioimpedance data [McDermott et al., 2024].

3.4. Gaps Addressed by the Proposed Device

- Detection Limit: Current modalities detect tumors ≥4.2 mm3 (MRI), far larger than the smart bra’s 0.5 mm3 target, limiting early detection.

- Portability: Most EIS and EIT systems are non-portable, unlike the smart bra’s wearable design.

- Specificity: Traditional EIS specificity (67–82%) is improved by the smart bra’s AI model (>85%) [Haeri et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2025].

- Continuous Monitoring: Unlike intermittent imaging, the smart bra enables daily monitoring, critical for high-risk populations.

- Multimodal Sensing: Combining EIS with temperature sensing addresses single-modality limitations [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

4. Innovations of the Proposed Device

4.1. Micro-Tumor Detection (0.5 mm3)

- High-Sensitivity EIS: The AD5933 impedance analyzer (10 kHz–1 MHz, 1 μV resolution) detects subtle impedance changes from tumors with conductivity of 0.8–1.5 S/m [Kuzmin et al., 2025].

- MNP-Enhanced Electrodes: 24 silver-nylon electrodes coated with MNPs targeting HER2/EGFR amplify impedance signals, improving sensitivity for low cell counts [Zheng et al., 2019]. Biocompatible coatings ensure safety and washability.

- Field-Focusing: Canonical voltage patterns (Neumann-to-Dirichlet mapping) enhance spatial resolution, targeting specific tissue voxels [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

4.2. Multimodal Sensing and Follow-Up

- EIS Data: Measures impedance magnitude, phase, and Cole-Cole parameters (R0, R∞, characteristic frequency) to differentiate malignant, benign, and normal tissues [Salem et al., 2023].

- Temperature Sensing: The DS18B20 sensor detects thermal anomalies (~1–2 °C higher in malignant tissues), enhancing diagnostic accuracy [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022]. This multimodal approach improves specificity over single-modality systems like EIT.

- HRV: 3-lead ECG sensor measures SDNN (<50 ms), RMSSD (<20 ms), and HF power (<200 ms2) every 3 months, predicting relapse (AUC = 0.80 with CEA) and cardiotoxicity (OR = 2.7) [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

4.3. Advanced AI Integration

- Space-Time Attention: Inspired by Yu et al. (2025), the model prioritizes critical frequencies (e.g., 100 kHz) and spatial patterns across the 24-electrode array, improving classification of multi-frequency EIS data.

- Feature Selection: Incorporates I0 (baseline impedance), DR (dispersion ratio), and Cole-Cole parameters, identified as discriminative by Salem et al. (2023).

- GAN Augmentation: Generates synthetic impedance data to address limited datasets, achieving 94% accuracy [McDermott et al., 2024].

- Explainability: SHAP values highlight key features (e.g., low impedance at specific frequencies), ensuring clinical interpretability.

4.4. Wearable Design

- Textile Integration: 24 electrodes are sewn into a cotton-spandex fabric, connected via conductive threads (Shieldex, <1 Ω/m), ensuring comfort and flexibility for daily wear, 3-lead ECG sensor (AD8232), DS18B20.

- Compact Electronics: A 3 × 5 × 1 cm module houses the AD5933, OPA657 amplifier, Jetson Nano, and 1500 mAh battery, supporting 24-hour operation (<150 mW).

- Continuous Monitoring: Scans every 4–6 hours enable longitudinal data collection, unlike intermittent imaging modalities.

- User Interface: A HIPAA-compliant smartphone app provides real-time alerts, impedance plots, and longitudinal trends, enhancing patient engagement.

4.5. Safety and Regulatory Compliance

- Electrical Safety: Currents <0.5 mA and SAR <0.75 W/kg comply with IEC 60601-1, minimizing risks [Zheng et al., 2019].

- Biocompatibility: MNP coatings are designed for skin safety and durability, addressing ethical concerns [Haeri et al., 2016].

- Regulatory Pathway: The device targets FDA 510(k) clearance as an adjunct to mammography, leveraging robust clinical validation.

5. Technical Design

5.1. Device Architecture

- EIS Calibration and Stability: Calibration is performed using a two-stage procedure to ensure consistency across users and environments. Instrument-level calibration employs an open–short–load reference set to correct cable parasitics, gain, and phase offsets across the 10 kHz–1 MHz band. Prior to each recording session, a tissue-level self-calibration is performed using the contralateral breast as an internal reference, normalizing inter-subject variability related to breast density, hydration, and temperature. Frequency-specific normalization compensates for slow thermal drift, and longitudinal stability is monitored via baseline Cole–Cole parameter tracking, with recalibration triggered when deviation exceeds ±5% of prior baseline values.

- Electrodes: 24 MNP-coated silver-nylon electrodes (2 mm2) in a 3 × 4 grid per breast target HER2/EGFR, enhancing sensitivity for ~5 × 104 cells. Conductive threads (Shieldex, <1 Ω/m) connect to a 32-channel multiplexer (ADG732) [Zheng et al., 2019]. The magnetic-nanoparticle (MNP) coating remains in the pre-clinical materials-characterization phase. Coating composition, thickness, and binding chemistry are being evaluated with respect to polarization impedance, frequency response stability, wash-cycle durability, and potential nanoparticle shedding risk. Clinical deployment will proceed only following completion of formal biocompatibility testing.

- Impedance Analyzer: The AD5933 chip performs frequency sweeps (10 kHz–1 MHz, 50 steps), with an OPA657 trans-impedance amplifier converting currents (0.3–10 μA) to voltages for high-precision measurements [Salem et al., 2023].

- Multimodal Sensing: A DS18B20 temperature sensor detects thermal anomalies, complementing EIS data [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

- Microcontroller: NVIDIA Jetson Nano (quad-core ARM Cortex-A57, 4 GB RAM) runs AI inference and signal processing (<150 mW), with 4 GB flash for data storage.

- Power: A 1500 mAh lithium-ion battery with wireless charging (BQ51050B) supports 24-hour operation, with a BQ24074 management system.

- Connectivity: Nordic nRF52840 Bluetooth Low Energy module transmits data to a smartphone app over a secure 2.4 GHz connection.

5.2. Signal Processing and AI

- Signal Processing: Motion and contact artifacts are treated as multiplicative, non-stationary perturbations rather than additive noise. A controlled bench protocol was used to characterize artifact sources including micro-slip shear, sweat-film impedance, contact pressure modulation, and cable strain. Each scan is preceded by a contact-stability and impedance-consistency check, and segments failing stability criteria are excluded prior to filtering. Variance in impedance magnitude and phase is quantified across frequencies before and after artifact rejection to assess robustness, ensuring robust impedance measurements [Shajari et al., 2023].

- AI Model: The machine-learning pipeline is framed as a candidate architecture for prospective evaluation rather than a finalized clinical model. Baseline comparators include logistic regression, gradient-boosted trees using engineered spectral features, and a 1D CNN over frequency bins. Splits are performed at the subject level to prevent leakage, including when contralateral calibration is applied. Confidence intervals are reported for modeled performance metrics. A conditional Wasserstein GAN with gradient penalty is used only for exploratory robustness analysis; all final performance estimates will be computed exclusively on real, non-augmented test data [Yu et al., 2025]. GAN augmentation generates synthetic data, overcoming dataset limitations [McDermott et al., 2024].

- Firmware: FreeRTOS on the Jetson Nano controls frequency sweeps, multiplexer switching, and data transmission, with auto-calibration using contralateral breast data every 24 hours.

5.3. Safety and Usability

- Safety: Currents <0.5 mA and SAR <0.75 W/kg ensure compliance with IEC 60601-1. MNP coatings are biocompatible and washable, minimizing skin irritation [Zheng et al., 2019].

- Usability: The cotton-spandex fabric, adjustable straps, and compact module ensure comfort for sizes XS–XL. The smartphone app provides intuitive visualizations and alerts.

6. Comparison with Existing Modalities

- Mammography: ~1000 mm3, limited by radiation and poor sensitivity in dense breasts.

- Ultrasound: ~65.4 mm3, operator-dependent with moderate specificity.

- MRI: ~4.2 mm3, costly and non-portable, requiring contrast agents.

- EIT: ~14.1 mm3, constrained by low resolution and specificity.

- Microwave Imaging: ~33.5 mm3, limited by complex processing.

- Emerging Techniques: Photoacoustic imaging (~4.2–14.1 mm3), thermography (~65.4 mm3), and wearable ultrasound (~14.1 mm3) lack the smart bra’s resolution and electrophysiological insights [Valluru et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023]. The device’s continuous monitoring, AI-driven specificity (>85%), and multimodal sensing provide a unique advantage for early detection in high-risk populations.

- ECG-based HRV enhances relapse and cardiotoxicity monitoring, surpassing clinical ECG studies [Berg et al., 2008; Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

| Modality / Technology | Typical Detection Limit* | Primary Sensing Contrast | Reported Sensitivity / Specificity (Range) | Portability & Point-of-Care Use | Suitability for Longitudinal Monitoring (Follow-Up / Screening Frequency) | Radiation / Thermal Exposure | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography | ~5–10 mm lesion diameter (density-dependent) | X-ray attenuation / tissue density | 77–95% / 70–92% (population and density dependent) | Clinic-based, fixed system | Episodic (12–24 months) | Ionizing radiation | Established clinical standard; population-scale screening evidence | Reduced performance in dense breast tissue; not wearable |

| Ultrasound (Handheld / ABUS) | ~3–5 mm | Acoustic impedance / echogenicity | 80–95% / 75–90% (adjunct to mammography) | Clinic-based (operator dependent) | Episodic — not continuous | No ionizing exposure | Improves detection in dense tissue; good lesion localization | Limited reproducibility; user-dependent |

| MRI (Dynamic Contrast) | ~4–5 mm (≈4.2 mm3 reported lower estimate) | Gadolinium contrast kinetics | 90–99% / 72–90% | High-end clinical imaging | Episodic — typically high-risk cohorts | Contrast agent + high SAR constraints | Highest sensitivity; strong in high-risk surveillance | High cost; not portable; limited frequency of use |

| Microwave Imaging | ~5–10 mm (prototype dependent) | Dielectric permittivity contrast | Emerging / variable | Portable prototypes | Potentially repeatable | Non-ionizing | Non-invasive biophysical contrast | Still experimental; reconstruction complexity |

| Photoacoustic Imaging (Emerging systems) | ~2–4 mm (vascular-linked detectability) | Optical absorption + ultrasound response | Early clinical feasibility ranges | Cart-based research systems | Episodic clinical follow-up | Non-ionizing | Microvasculature contrast, complementary to US | Limited wearable implementation; localization focus |

| Wearable Ultrasound Systems | ~3–6 mm (conformal patch prototypes) | Acoustic impedance | Feasibility reports only | Semi-portable research devices | Semi-periodic scanning possible | No ionizing exposure | Continuous structural imaging potential | Requires precise placement; user-training |

| Thermal-Imaging / Thermography Wearables | Indirect physiological correlates (surface temperature gradients) | Heat-transfer / vascular thermoregulation | Performance varies by dataset | Portable / wearable | Suitable for frequent monitoring | No ionizing exposure | Non-contact; low burden | Indirect marker; high sensitivity to confounders |

| Proposed Smart-Bra (EIS + ECG-HRV Multimodal Platform) | Model-based detectability target: ~0.5 mm3 (pre-clinical forward-model estimate) | Electrical conductivity / permittivity + autonomic cardiac regulation (HRV) | To be established prospectively (STARD-aligned clinical validation) | Fully wearable, textile-integrated | Designed for repeated longitudinal monitoring (3-month intervals) | Non-ionizing; low-power bioimpedance | Combines local tissue bioelectric signatures with systemic physiological markers; portable and repeatable | Clinical detection limits and diagnostic accuracy pending validation |

- Detection limits are reported as typical practical ranges rather than theoretical minima and depend on tissue composition, lesion depth, system configuration, and acquisition protocol.

- For the proposed device, the 0.5 mm3 value reflects a model-based detectability estimate derived from forward-model sensitivity analysis and is not yet a clinically demonstrated diagnostic threshold; definitive performance will be determined in the prospective trial.

- The comparison emphasizes portability and monitoring capability, as requested by reviewers, to differentiate episodic imaging modalities from wearable approaches.

7. Clinical Validation Strategy

- Patients wear the Smart Bra 8–12 hours/day for 12 months post-diagnosis, with EIS scans every 4–6 hours and 5-minute ECG recordings every 3 months to measure SDNN, RMSSD, and HF power.

- Baseline HRV and CEA measurements at diagnosis, followed by 3-month interval assessments to detect SDNN reductions (~20%) for cardiotoxicity and RMSSD < 20 ms for relapse [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

- Confounders (e.g., beta-blockers, antidepressants) will be adjusted using multivariate regression to ensure HRV reliability [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

- Comparator tests include mammography, ultrasound, clinical 12-lead ECG, and CEA levels every 3 months.

8. Expected Outcomes and Impact

9. Critical Evaluation

9.1. Strengths

- Unprecedented Resolution: The 0.5 mm3 detection limit enables earlier detection than any current modality, critical for improving survival rates.

- Non-Invasive and Wearable: Continuous monitoring addresses the intermittent nature of traditional imaging, ideal for high-risk populations.

- AI-Driven Specificity: The LSTM-XGBoost model with space-time attention overcomes traditional EIS specificity limitations (67–82%), achieving >85% [Yu et al., 2025].

- Multimodal Innovation: Combining EIS and temperature sensing enhances diagnostic robustness [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

9.2. Limitations and Mitigation

- Clinical Validation: The 0.1 mm3 detection limit is based on phantom studies and small cohorts [Kuzmin et al., 2025]. The 1000-patient trial will confirm performance in diverse populations.

- Specificity Challenges: Traditional EIS specificity is limited by tissue heterogeneity. The AI model and contralateral calibration address this [Haeri et al., 2016].

- MNP Integration: Regulatory hurdles for MNP coatings require rigorous biocompatibility testing, which is planned in preclinical studies [Zheng et al., 2019].

- AI Generalizability: Overfitting risks are mitigated by GAN augmentation and diverse training data [McDermott et al., 2024].

10. Conclusion

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, W. A.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of mammography, clinical examination, and ultrasonography. Radiology 2008, 249, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buderer, N. M. Statistical methodology: I. incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Academic Emergency Medicine 1996, 3, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; et al. Systematic review of electrical impedance spectroscopy for malignant neoplasms. Medical Physics 2020, 47, e201–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S. P.; et al. Voltage-gated sodium channel expression and potentiation of human breast cancer metastasis. Clinical Cancer Research 2005, 11, 5381–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiseppi-Elie, A. Bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy for monitoring mammalian cells and tissues. Biosensors 2022, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeri, Z.; et al. EIS for breast cancer diagnosis: Clinical study. Journal of Medical Systems 2016, 40, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlikowske, K.; et al. Breast density and mammography performance. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, T. M.; et al. Comparison of ultrasound and mammography in dense breasts. Radiology 2002, 225, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsojannis, C.; et al. Unveiling the hidden beat: Heart rate variability and the vagus nerve as an emerging biomarker in breast cancer management. IgMin Research 2025, 3, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C. K.; et al. MRI for diagnosis of breast cancer. Radiology 2007, 244, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, A; Baranov, V. Bioimpedance spectroscopy of breast phantoms. J Electr Bioimpedance 2025, 16, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. Wearable Photonic Smart Wristband for Continuous Cardiorespiratory Monitoring and Biometric Identification. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2023, 12, 2202456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, S.; et al. Portable non-invasive technologies for breast cancer detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, B.; et al. Improved bioimpedance spectroscopy tissue classification through data augmentation from generative adversarial networks. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2024, 139, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meaney, P. M.; et al. Microwave imaging for breast cancer detection. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2012, 60, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meani, F; Barbalace, G; Meroni, D; Pagani, O; Perriard, U; Pagnamenta, A; Aliverti, A; Meroni, E. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy for Ex-Vivo Breast Cancer Tissues Analysis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2023, 51, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, D.; et al. Machine learning in microwave imaging for breast cancer detection. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2023, 22, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.; et al. Early breast cancer detection and differentiation tool based on tissue impedance characteristics and machine learning. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023, 27, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajari, S.; et al. Machine learning for bioimpedance-based cancer detection. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluru, K. S.; et al. Photoacoustic imaging in breast cancer. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2016, 42, 2839–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; et al. Wearable ultrasound patch for breast cancer detection. Nature Biotechnology 2023, 41, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; et al. BiaCanDet: Bioelectrical impedance analysis with space-time attention neural network. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 91, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; et al. Biosensor for low-quantity breast cancer cell detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 139, 111321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).