1. Introduction

Nanotechnology—the manipulation of matter at the molecular and atomic scale—has unlocked transformative opportunities in energy production and materials engineering. With global energy demand and environmental concerns driving the shift away from fossil fuels, biotechnology has emerged as a route to produce clean power from organic waste streams [

1,

2]. Among the most promising solutions are microbial fuel cells (MFCs), which convert renewable organic matter directly into electricity [

3,

4,

5]. MFC is a set-up that uses bacteria to transform chemical energy into electricity by degrading organic material present in sewage [

6]. The advantages of applying MFC as an alternate energy source include synchronised treatment of sewage and electricity production from organic matter, demonstrating MFC as a cutting-edge and proactive research area. In MFC, the electrodes and the bacteria work together to create biofilms on the anodic surface. This kind of MFC simplifies the process for complex organic matter to be transformed into a resource for energy production via microbial metabolism. Potter, in 1911, introduced and brought forth the original idea of MFC [

7]. In principle, MFC consists of anodic and cathodic chambers segregated by a PEM. The anodic compartment consists of a substrate and bacterial solution made up of

Escherichia coli,

Shewanella,

Gammaproteo,

Geobacter, and/or

Deltaproteo.

By merging nanotechnology with MFCs, performance can be greatly enhanced through advanced electrode materials, nanoscale catalysts, and optimized electron-transfer processes. These innovations enable efficient bioenergy production from diverse substrates while minimizing environmental impact [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The new era of space exploration—encompassing the Artemis program, long-term lunar bases, and planned crewed missions to Mars—places a premium on compact, sustainable, and autonomous life-support and energy systems [

13]. Missions beyond low Earth orbit (LEO) face severe constraints on mass, volume, and resupply, making closed-loop resource utilization and in situ resource utilization (ISRU) essential. Biological systems, including microbial technologies, offer resilience, self-sufficiency, and lower energy demands compared to many physicochemical methods [

13,

14]. Within this context, MFCs acquire strategic importance. They can convert organic waste generated by crew or bioregenerative systems into electricity while simultaneously aiding in water recovery and nutrient recycling. Nanotechnology-enhanced MFCs, being lightweight, compact, and potentially low-maintenance, are especially attractive for spacecraft and extraterrestrial habitats with strict payload limits [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Experiments aboard the International Space Station with

Rhodoferax ferrireducens have confirmed that MFCs can operate under microgravity, producing electricity at levels comparable to those on Earth [

19]. NASA studies highlight further advantages: rapid waste processing, minimal biomass generation, and effective removal of organics, nitrogen, and phosphorus—qualities valuable for integration into Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) and ISRU architectures [

20]. Projects such as NASA’s “bioelectric space exploration” initiative have even demonstrated fuel cells powered by wastewater and electricity-breathing bacteria [

21].

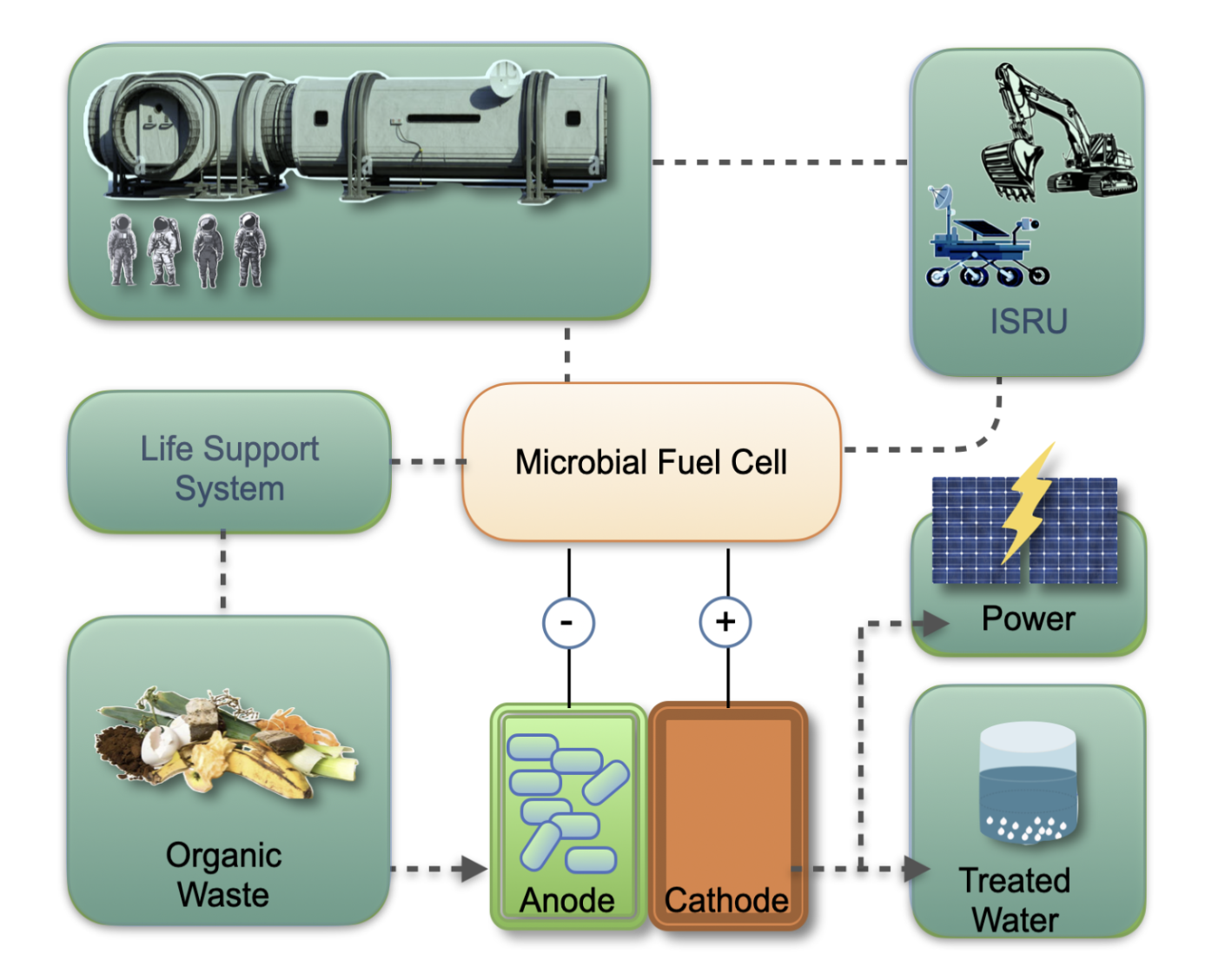

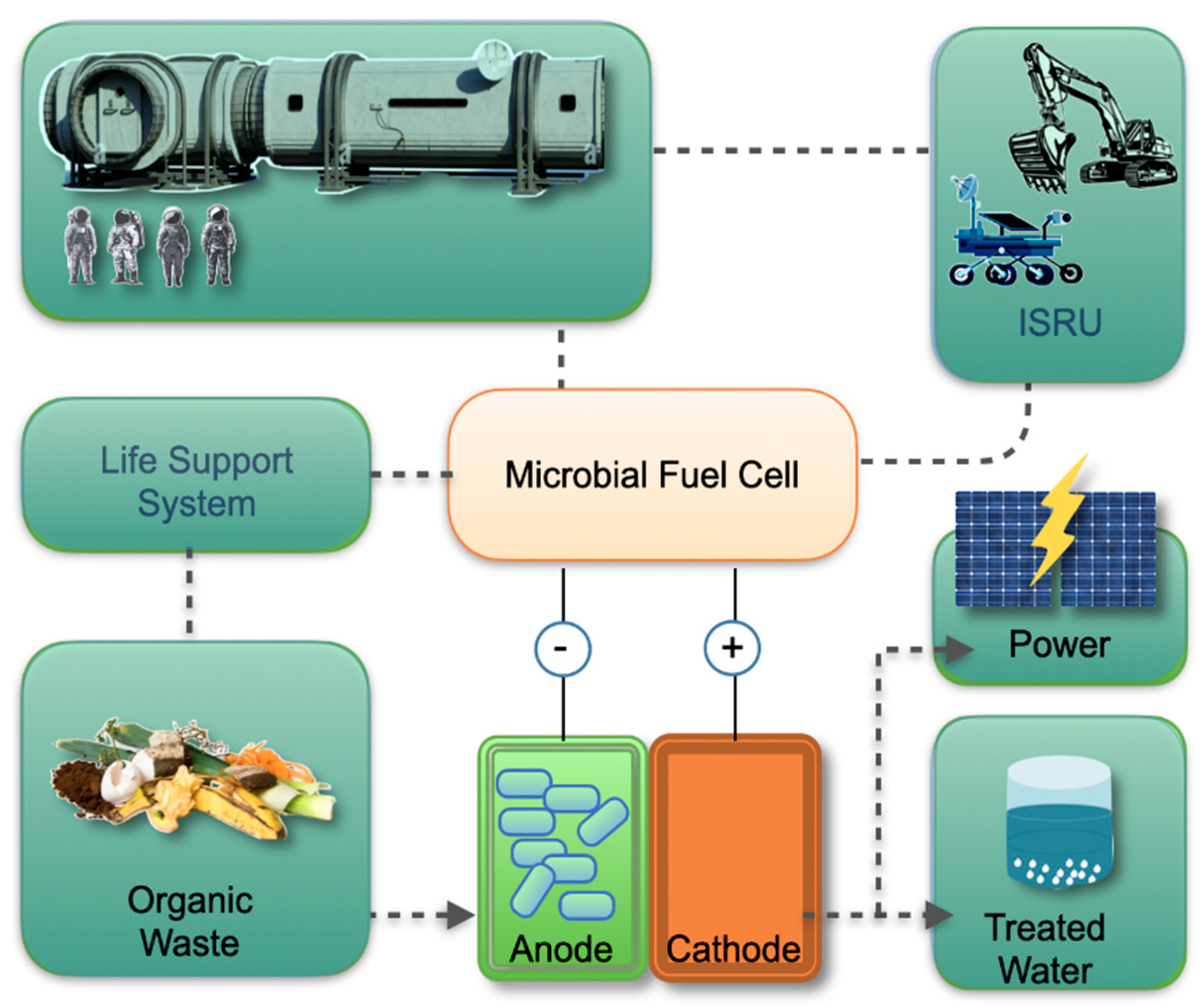

These advancements point to the integration of MFCs into space vehicles, habitats, and robotic platforms, where they could act as compact, multifunctional energy converters (

Figure 1). Beyond power generation, they contribute to closing resource loops, extending mission autonomy and enabling sustainable human presence in space.

2. Biofuel Cells – Generating Power from Biology

2.1. What Are Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs)?

Biofuel cells (BFCs), particularly microbial fuel cells (MFCs), are bioelectrochemical devices that convert the chemical energy stored in organic matter directly into electricity via the catalytic activity of microorganisms [

22]. In the space context, they are uniquely suited to valorizing organic waste streams produced by the crew or other biological systems, thus coupling waste treatment with energy production [

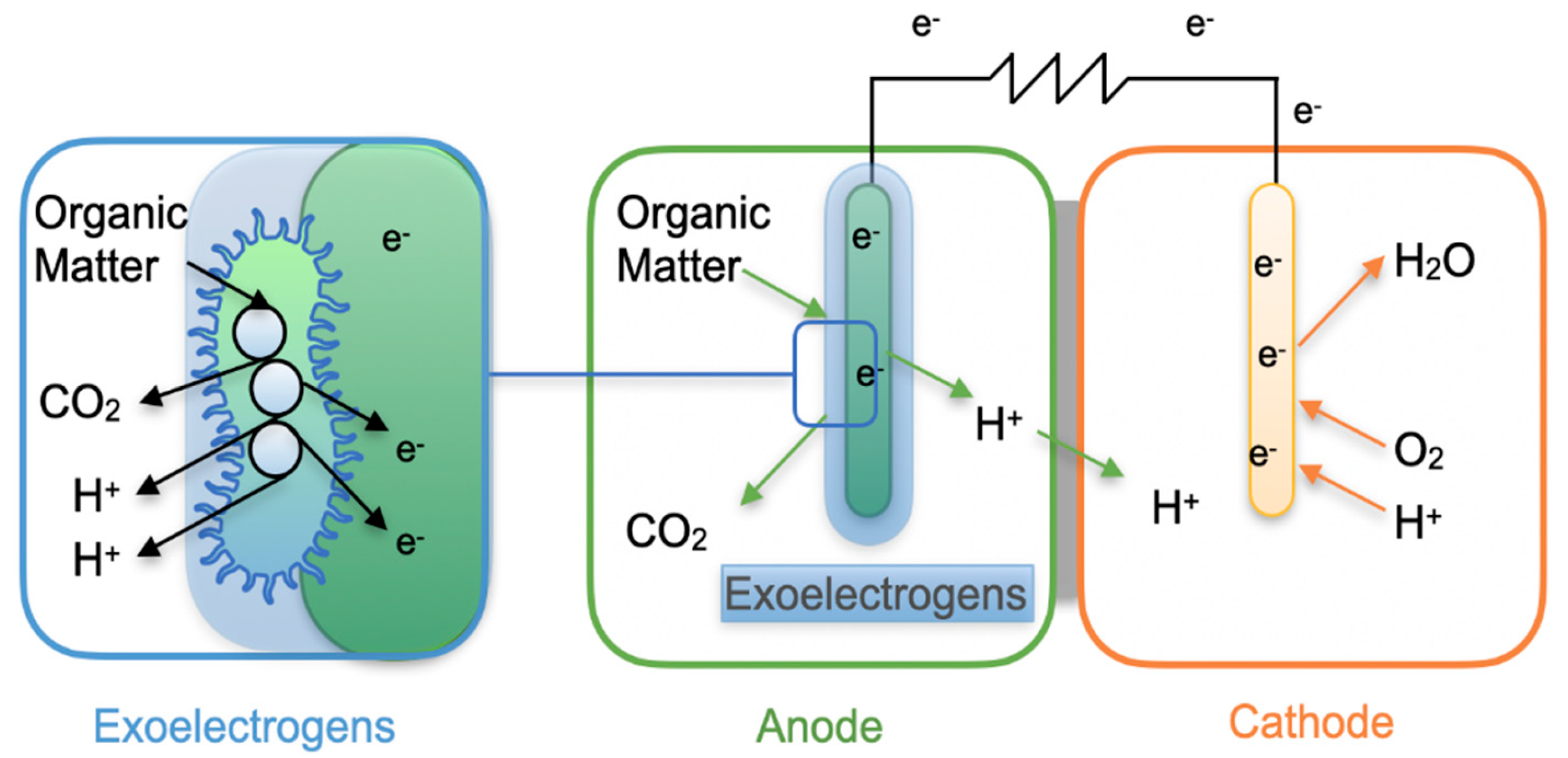

23]. MFCs are innovative bioelectrochemical devices that generate electricity through the metabolic activity of microorganisms. These bacteria perform microbial electrogenesis, oxidizing organic materials and transferring the released electrons to an electrode. The microorganisms involved in this electrochemical activity - known as exoelectrogens - can be found in diverse environments such as soil, wastewater, and activated sludge. Representative genera include

Pseudomonas [

24],

Shewanella [

25],

Geobacter [

26] and

Desulfuromonas [

27].

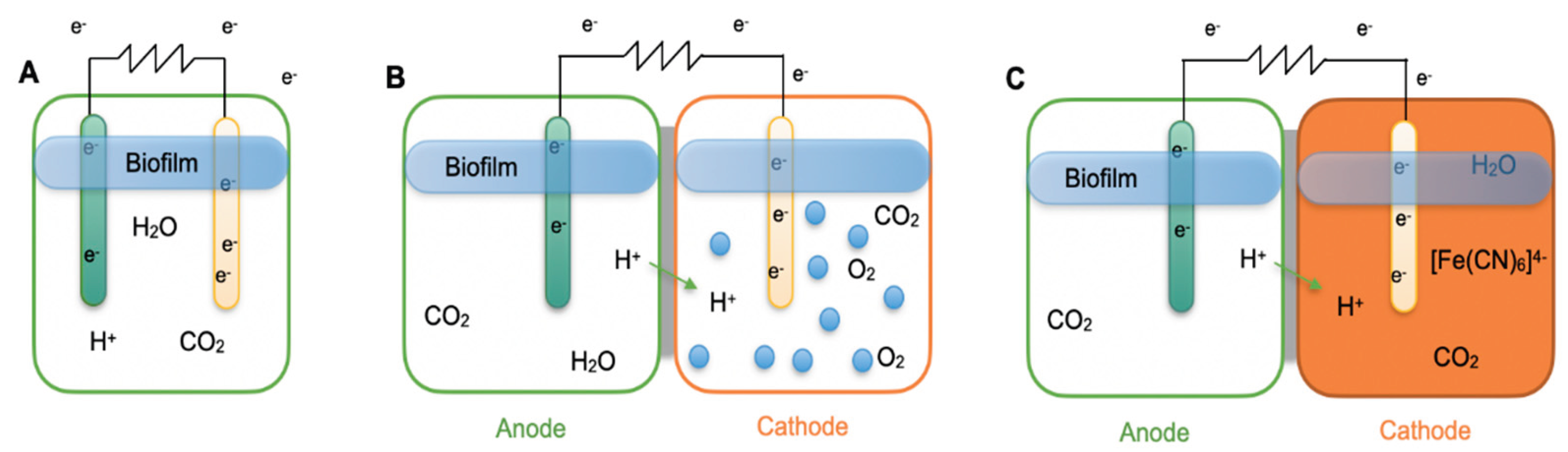

A typical MFC consists of four main components: an anode, a cathode, a proton exchange membrane (PEM) or ion-permeable separator, and an external circuit (

Figure 2). The bacteria attach to the anode surface via cytochromes or other redox-active proteins, oxidizing organic or inorganic matter from the substrate—often wastewater—and releasing electrons, protons, and CO₂ in the process [

28]. Electrons flow through the external circuit to the cathode, while protons migrate through the PEM. At the cathode, in the presence of a strong oxidizing agent such as oxygen, electrons and protons combine to produce clean water, and in some cases hydrogen gas, thereby closing the electrochemical loop [

29].

Wastewater serves as an ideal substrate for MFCs because it contains renewable biomass and a natural consortium of microorganisms that act as biocatalysts [

28]. Organic pollutants, typically in the form of carbonaceous compounds, are biochemically converted into electricity while simultaneously achieving wastewater treatment [

29]. This dual functionality makes MFC technology attractive for sustainable, cost-effective bioelectricity production. In the context of space exploration, MFCs offer an additional advantage: various waste streams—including urine, fecal matter, and inedible food residues—can be transformed into valuable resources [

13]. With the help of microorganisms, these wastes can be converted not only into electrical energy but also into nutrients and potable water, supporting closed-loop life-support systems critical for long-duration missions [

20].

2.2. Electron Transfer Mechanisms

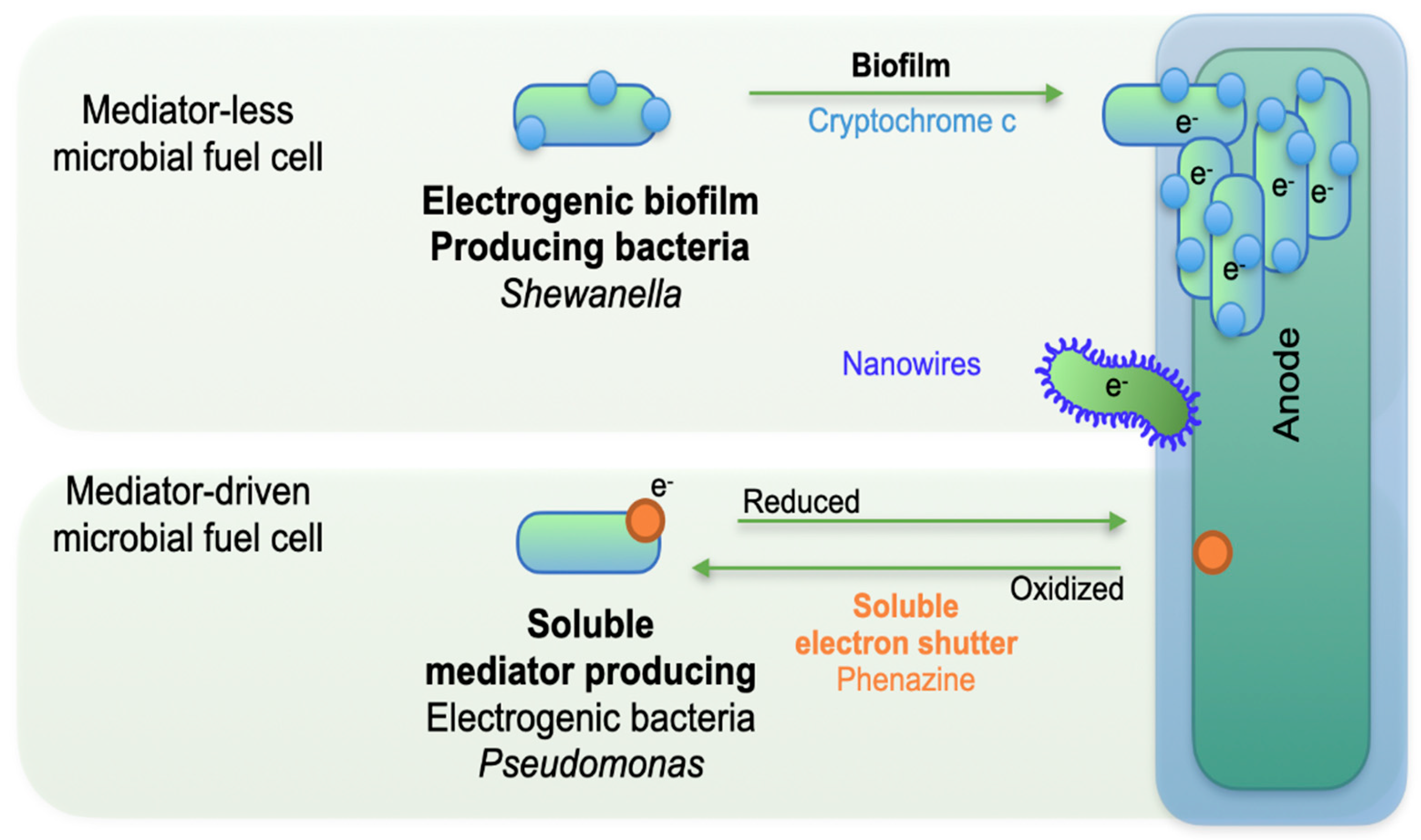

Electron transfer in MFCs occurs when bacterial biomolecules, such as proteins, facilitate the donation and acceptance of electrons between microorganisms and electrodes. This extracellular electron transfer (EET) takes place via two main mechanisms: Direct Electron Transfer (DET), also known as mediator-less transfer, and Mediated Electron Transfer (MET) [

31]. The bacteria

Geobacter spp. and

Shewanella spp. are among the most extensively studied for their EET capabilities [

32].

Figure 3 presents a schematic illustration of these mechanisms.

In MET, microorganisms lack electrochemically active surface proteins capable of transferring electrons directly to the anode. Instead, they rely on mediators - electroactive compounds that shuttle electrons between cells and electrodes. These mediators, which can be synthetic (e.g., neutral red) or naturally occurring (e.g., sulfate/sulfide) [

33], penetrate the bacterial cell membrane and wall to accept electrons from metabolic processes. Once reduced, the mediator leaves the cell, deposits the electrons onto the anode (causing it to become negatively charged), and returns to its oxidized state to repeat the cycle. Increasing mediator concentration can enhance electron availability, but the use of synthetic mediators adds cost and potential toxicity.

In case of DET, electron transport is mediated by metal-reducing bacteria that naturally possess electroactive enzymes and conductive structures. DET is particularly important in treating wastewater containing heavy metals [

34].

For both mechanisms, efficient electron transfer depends on factors such as the presence of electrochemically active enzymes, appropriate external circuit resistance, robust biofilm formation on the anode, and proper proton transport across the membrane. Insufficient proton transfer can slow cathodic reactions, alter pH, and limit both electron flow and microbial activity. From an energy production standpoint, DET is generally preferred over MET due to its safety, lower cost, and higher power output potential [

35].

2.2.1. Mediated Electron Transfer (MET)

Many microorganisms are unable to perform direct electron transfer because they either lack surface-active proteins or do not have direct physical contact with the electrode surface [

36]. In such cases, they rely on indirect electron transfer. This process, known as Mediated Electron Transfer (MET), involves the use of redox mediators — compounds that act as shuttles to carry electrons from microbial cells to the terminal electron acceptor. In MFCs, the mediator accepts electrons from the bacterial cell, becoming reduced, and then transfers these electrons to the anode. Once oxidized, the mediator is ready to repeat the cycle. According to Ieropoulos et al. [

37] an effective mediator should: (i) easily cross the bacterial cell membrane, (ii) be non-toxic to the microorganisms, (iii) be highly soluble in the anolyte, (iv) have a sufficiently positive redox potential to facilitate efficient electron transfer, and (v) be low-cost and readily available commercially. Redox mediators may be exogenous, meaning they are added externally, or endogenous, produced naturally by the bacteria themselves.

2.2.2. Mediator- Less Electron Transfer (DET)

The direct electron transfer (DET) mechanism involves the transfer of electrons directly from microorganisms to electrodes without the use of mediators. This process requires physical contact between the bacterial cell membrane and the electrode [

38]. DET is facilitated by outer membrane cytochromes (OMCs), conductive pili, or self-assembled nanowires (

Figure 2) [

32]. C-type cytochromes, located on the cell surface, act as redox proteins enabling electron transfer to the terminal electron acceptor. These multi-heme proteins exhibit a redox potential of approximately 1 V and are resistant to chemical modifications [

39].

2.3. Microorganisms in MFCs

Microorganisms are the key drivers of energy generation in microbial fuel cells (MFCs), as they mediate the necessary biochemical reactions. Two main groups of microorganisms are typically employed: electrode-reducing and electrode-oxidizing species. Electrode-reducing microbes facilitate electron transfer to the anode, often through reduction processes, while electrode-oxidizing microbes—commonly referred to as electricigens—oxidize organic substrates and transfer the resulting electrons to the electrode [

40]. Electron transfer can occur via soluble mediators, outer membrane proteins, or pili extending from the bacterial surface. In contrast, electrode-oxidizing microorganisms accept electrons from the cathode and use them to reduce compounds such as acetate or carbon dioxide. Therefore, the selection of microbial strains for MFCs must account for their electron transfer efficiency from substrates to the anode [

41].

Microbial cultures applied in MFCs can be either pure or mixed [

42]. Pure cultures, particularly species of

Geobacter [

43] and

Shewanella [

44], are among the most frequently used due to their strong electrochemical activity. Nonetheless, many other microorganisms with potential roles in electricity generation remain to be identified. Several well-studied groups of pure-cultured electricigens include: (1)

Archaebacteria, capable of surviving under extreme conditions such as high temperatures or salinity, and thus suitable for electricity generation in specialized environments [

45]; (2)

Acidobacteria, a metabolically versatile and acidophilic group able to utilize diverse substrates [

46]; (3)

Cyanobacteria, photosynthetic and environmentally friendly microbes that generate electricity via water oxidation driven by light [

47]; and (4)

Proteobacteria, one of the largest groups of electroactive microbes, with strains across α-, β-, γ-, and δ-classes capable of direct electron transfer to electrodes.

Although eukaryotic microorganisms are less studied in MFCs, yeasts have demonstrated potential due to their rapid growth, although their energy yields are generally lower compared to bacteria. Advances in strain engineering have, however, improved their bioenergy output [

44]. In addition, well-recognized exoelectrogens include

Geobacter [

48],

Shewanella [

49],

Pseudomonas, and

Clostridium [

47]. Mixed microbial communities are also widely applied, as they enhance biological stability and are readily obtained from sources such as soil, marine sediments, natural consortia, or brewery wastewater [

50]. Other viable inocula include activated sludge, domestic and municipal wastewater, and metal-reducing environments, all of which harbor diverse microbial species capable of bioelectricity production [

51].

Recent studies have also focused on photosynthetic bacteria as promising bioelectricity producers. These microbes provide a sustainable approach by coupling photosynthesis with electron transfer, simultaneously removing carbon dioxide while producing energy [

52]. Another innovative strategy involves synergistic consortia of heterotrophic and photosynthetic bacteria, where organic matter produced during photosynthesis serves as a substrate for heterotrophic partners. For example,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains used with the cofactor NAD show enhanced metabolism and higher energy yields [

53].

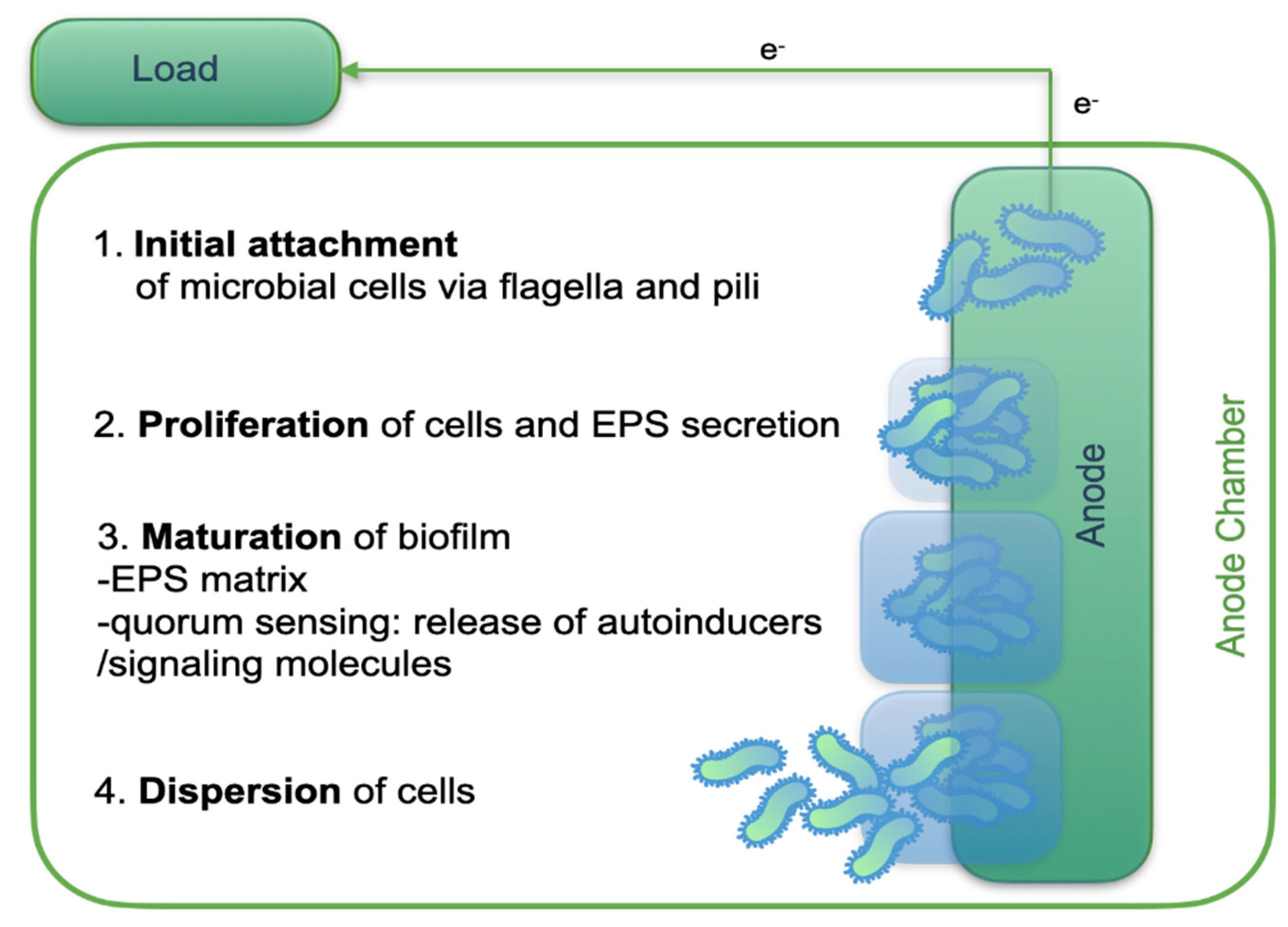

Electroactive bacteria often organize into biofilms on the anode to optimize substrate oxidation and electron transfer. These biofilms consist of cells embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix composed of proteins, polysaccharides, and other macromolecules that facilitate electron transport to the electrode surface [

54,

55]. Biofilm development is also supported by electrostatic interactions between negatively charged organic compounds in nutrient media and microbial by-products. Moreover, extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) form a major structural component of biofilms, influencing their physicochemical properties and enhancing electron transfer efficiency [

56,

57,

58]. The stages of anode biofilm formation are summarized in

Figure 4.

2.4. Types of MFC Design

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) can be designed in several different ways depending on their structure, mode of operation and intended application. The most common classification refers to single-chamber and dual-chamber systems, where the latter typically separate the anode and cathode compartments with a membrane, while single-chamber designs often eliminate the membrane for simplicity and reduced cost [

59,

60]. Another important distinction is whether the system operates with mediators, which facilitate electron transfer, or in mediator-less configurations relying on electroactive microorganisms. Designs may also differ in electrode arrangement, ranging from flat-plate setups to more advanced three-dimensional or tubular structures that maximize surface area and enhance biofilm growth [

61,

62]. Furthermore, MFCs can be categorized according to scale and purpose, from laboratory-scale devices used for research to pilot or full-scale systems developed for wastewater treatment, biosensing, or energy recovery. Each design type has its own advantages and limitations, and ongoing research continues to refine these approaches to improve performance, scalability, and economic feasibility [

63,

64].

Table 1 presents the main categories and design features of microbiologically driven electrochemical cell systems along with their schematic description.

3. Determinants of MFC Performance for Space Missions

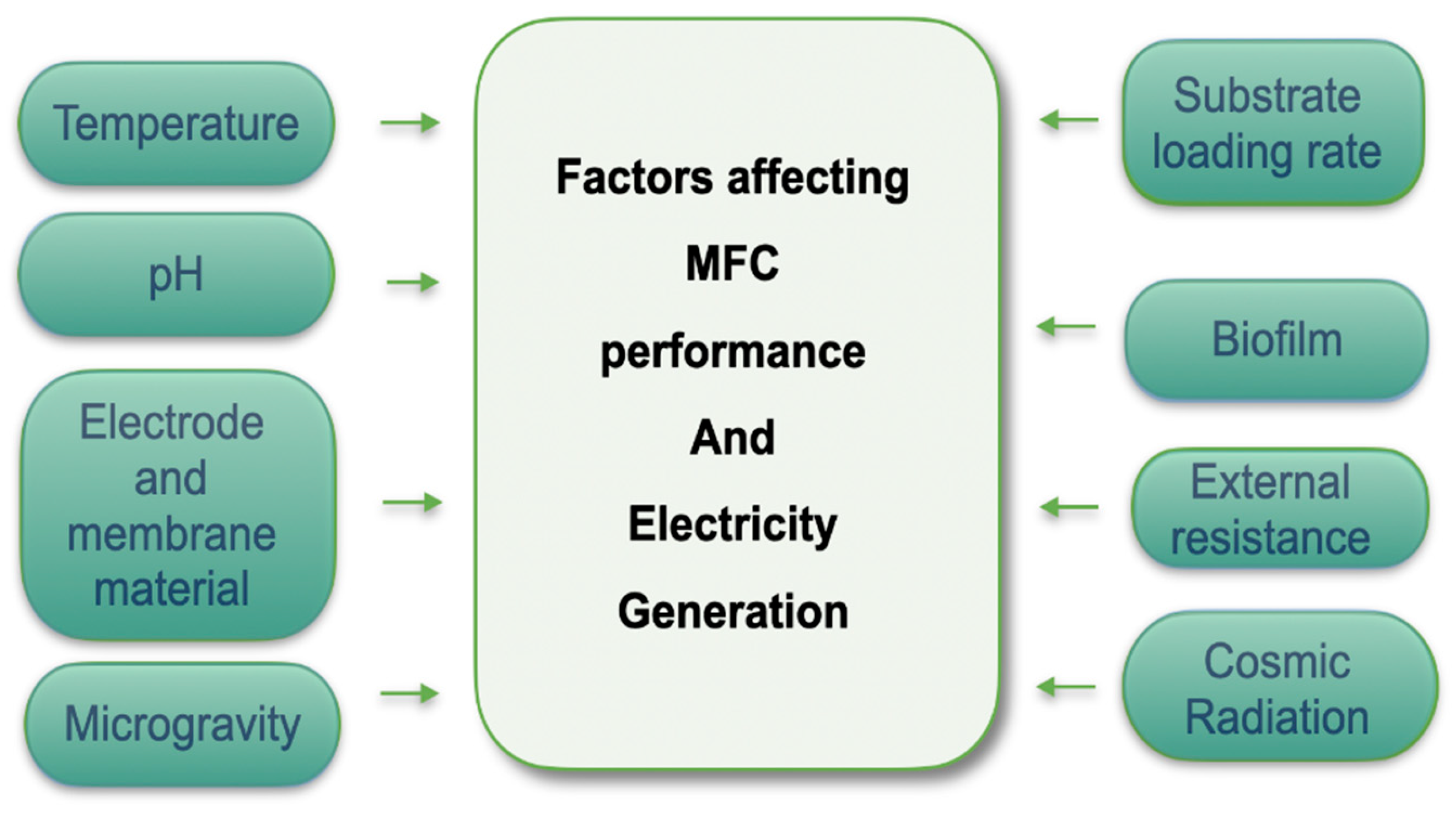

The performance of microbial fuel cells (MFCs) is influenced by a wide range of factors, including anodic and cathodic operating parameters, electroactive microbial (EAM) communities and their properties, substrate characteristics, proton exchange membranes (PEMs), temperature, electrode materials and pH levels. Pilot - scale studies have shown that controlling startup conditions - particularly chemical oxygen demand (COD) concentration, temperature, and pH - is crucial for effective biofilm formation and stable system operation. The variation of these parameters highlights the need for precise optimization and provides a basis for future investigations [

65]. In the context of space applications, where systems must function under microgravity and with limited resources, the careful selection of materials and operating parameters becomes even more critical to ensure both stability and efficient energy generation.

Figure 5 illustrates these interrelated factors in a web diagram of MFC performance and electricity production (modified [

28]).

The anode, where oxidative degradation of organic substrates occurs, plays a central role in initiating electron flow. Anode materials such as graphite, activated carbon, carbon fibers, or coated metal alloys must exhibit high conductivity and large specific surface area to promote biofilm formation and facilitate efficient electron transfer [

66,

67]. A porous surface enhances microbial adhesion and stabilizes the biofilm, which is particularly important under microgravity, where adhesive forces are reduced. Additionally, the anode must demonstrate chemical resistance to microbial metabolites and variable pH to ensure long-term reliability.

The cathode serves as the electron acceptor and participates in reduction reactions, such as oxygen reduction in air-cathode systems. High cathodic activity requires appropriate catalysts, including platinum, activated carbon, or microbial biocatalysts, to accelerate redox reactions [

68,

69]. In the context of space missions, where oxygen availability may be limited, air-cathodes or regenerating electron acceptor systems are essential. A porous cathode structure facilitates gas and ion diffusion, directly enhancing overall cell performance.

An electroactive biofilm formed on the anode enables direct electron transfer and is a critical component of MFC function. Optimal biofilm density and thickness are essential for power generation - too thin a layer limits electron flow, whereas excessively thick biofilms can cause mass transport limitations [

70]. In space, biofilms must maintain structural integrity under microgravity, necessitating the use of microorganisms such as

Geobacter or

Shewanella, capable of direct or mediator-facilitated electron transfer [

70]. Supporting biofilm stability through high-adhesion anode materials or polymers is often necessary [

71].

The membrane separating the anode and cathode allows selective ion transport, typically of protons, while minimizing substrate crossover. Polymer membranes, such as Nafion, provide high ionic conductivity while maintaining chemical and mechanical resistance, crucial for long-duration space missions [

72]. Membrane thickness must be carefully optimized: excessively thick membranes increase internal resistance, whereas overly thin membranes risk leakage and substrate mixing [

73]. The external circuit and selection of electrical resistance determine the maximum power output of the MFC. In space applications, automated load management systems enable dynamic adjustment of resistance to match biofilm activity and substrate availability, enhancing the system’s energy efficiency [

74,

75]. Environmental factors such as temperature, pH, and organic substrate availability strongly influence microbial performance. Maintaining optimal biological conditions in space requires advanced climate control systems, while limited substrate supply necessitates the efficient utilization of crew-generated organic waste [

22]. Consequently, MFCs provide not only a sustainable energy source but also an integral component of waste recycling in closed-loop space habitats [

22].

4. Strategic Positioning of Bio-Biotechnology in Space Exploration

Multiple strategic roadmaps for sustainable space exploration identify biotechnology as a key enabling domain for off-world autonomy. Within these roadmaps, biofuel cells are recognized as complementary energy sources that also contribute to waste minimization and resource recovery. Their potential spans low - power continuous operation, coupling with water recovery units, and synergistic integration with photobioreactors or algal cultivation systems for enhanced substrate supply [

17,

76]. Technology readiness level (TRL) analyses suggest that certain BFC configurations could be flight-tested in the near term, particularly within experimental payloads on the International Space Station (ISS) or lunar surface demonstrators [

17].

4.1. The Role of Microorganisms in Space Systems

Microorganisms play a dual role in space habitats: while they can pose risks through biofilm formation, pathogenicity, or material degradation, they also offer unparalleled potential as biological catalysts in regenerative life-support systems. Their metabolic versatility enables the transformation of waste streams into valuable resources, such as clean water, oxygen, nutrients, and energy [

13]. Recent reviews have highlighted microbial applications not only for bioremediation and food production but also for the synthesis of functional materials and bioprotective agents in space [

13,

77]. The integration of microbial processes into bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) and bio-ISRU concepts represents a strategic shift toward self-sufficiency in extraterrestrial environments. In recent years MFCs have been proposed for incorporation into closed-loop life-support architectures and hybrid systems combining microbial bioreactors with electrochemical modules [

22,

78,

79].

4.2. Bioelectricity Generation from Wastewater via MFC in Space Habitats

During space travel, various types of waste can accumulate, including urine, fecal matter, and inedible food residues. With the aid of microorganisms, such waste can be converted into valuable resources — not only for energy production but also for nutrient recovery and the generation of potable water.

Urine is a particularly suitable substrate for microbial fuel cells (MFC), as it contains high concentrations of urea, organic ammonium salts, and other compounds readily metabolized by microbes to generate electricity [

80,

81,

82,

83]. This makes urine-based MFCs highly effective for energy production. In some designs, these systems can simultaneously recover nutrients. For example, Lu et al. [

82] developed a three-chamber MFC capable of removing organic pollutants from urine while recovering nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S), and producing electricity. Their system achieved a maximum power density of 1300 mW/m², with near-complete removal of contaminants — including over 97% of urea, total nitrogen, sulfate, phosphate, and chemical oxygen demand — as well as 40% of ammonium, 15% of salts, and 91–99% of organic compounds. The MFC also recovered essential nutrients, including 42% of total N, 37% of phosphate, 59% of sulfate and 33% of total salts. For urine MFCs to also serve as systems for converting urine into potable water, the high concentration of inorganic salts naturally present in urine (~14.2 g/L) [

84] must first be reduced, as these salts hinder efficient MFC operation [

82]. This can be achieved using a modified version of the technology known as a microbial desalination cell (MDC). The MDC operates on the same principle as a conventional MFC but incorporates an additional desalination chamber positioned between the anode and cathode [

85]. Cao et al. [

85] evaluated this approach for water desalination at salt concentrations similar to those found in urine — 5, 20, and 35 g/L — using a mixed bacterial culture. Salinity was monitored by measuring changes in the solution’s conductivity. The system achieved a maximum power density of 2 W/m² while removing approximately 88–94% of the salts, depending on the initial concentration.

Other organic components of wastewater, such as human feces, can also serve as a resource for electricity generation in MFC systems. Fangzhou et al. investigated the potential of MFCs to generate power from activated sludge obtained from a sewage treatment plant, with the aim of integrating the technology into Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) for future crewed space missions [

86]. Their tests compared several configurations: a standard two-chamber MFC, an adjustable two-chamber MFC, a single-chamber MFC with one or two membrane electrode assemblies, and a fermentation pre-treatment device. The two-chamber MFC achieved the highest peak power density at 70.8 mW/m², but the researchers concluded that the single-chamber configuration would be more suitable for space applications due to its more stable voltage output of 0.3 V [

86]. Pollutant removal efficiency was also assessed, showing approximately 44% removal of ammonium and 71% removal of organic matter across all configurations [

86]. To enhance both electricity production and toxin removal from fecal wastewater, the team proposed fermentation pre-treatment. This method used anaerobic sludge-filled reactors to break down fecal macromolecules into smaller organic molecules. Pre-treated wastewater generated 47% more power than untreated samples, indicating that exoelectrogens in the MFCs prefer smaller organic substrates (Fangzhou et al., 2011). Based on these findings, the researchers designed an automated human-feces wastewater MFC system incorporating a fermentation pre-treatment stage. This setup could process one day’s worth of fecal waste while generating electricity, achieving a maximum power density of 240 mW/m² — approximately 3.5 times higher than that of the standard two-chamber MFC [

86].

Inedible food waste will be an inevitable part of spaceflight and extraterrestrial outposts on the Moon and Mars that need to be disposed of, just as on Earth. This organic material can serve as a substrate for MFC-based energy production. Colombo et al. [

87] tested the energy-generation capabilities of MFCs using various food-industry organic wastes, including those rich in fibers, sugars, proteins, and acids. A one-chamber MFC was fed with each type of substrate, and the concentration of organic compounds was periodically measured to determine the degradation rate. The maximum power output recorded for each type was 50 mV for sugar, 40 mV for fiber, 30 mV for protein, and 10 mV for acid, with approximately 90% degradation of each organic compound.

A summary of the researchers’ findings is presented in

Table 2. Together, these results highlight the versatility of MFCs in converting diverse waste streams into electricity, making them promising candidates for both terrestrial waste-to-energy systems and closed-loop life-support architectures in space.

4.3. Optimization and Scaling of Microbial Fuel Cells for Space Applications

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) hold significant potential for generating energy and recycling organic waste beyond low Earth orbit (LEO), though ongoing research is focused on enhancing their efficiency and achieving a stable, higher power output. Various approaches are being explored, including different materials such as ceramics, as well as diverse configurations ranging from small to large or stacked to dispersed systems [

88].

Gajda et al. [

18] investigated terracotta MFCs of two sizes: a small unit (70 mm long, 15 mm diameter, 2 mm thickness) and a larger unit (100 mm long, 42 mm diameter, 3 mm thickness). Interestingly, the smaller MFC delivered a power density nearly three times higher than the larger one, with 20.4 W/m³ versus 7.0 W/m³, respectively. They also explored stacked configurations for small-scale multi-unit systems suitable for future crewed outposts.. In this setup, a small module of 28 MFC units was compared with a larger module of 560 units. Stacking 560 units resulted in a fivefold increase in power output, reaching 245 mW. Another practical application is the PeePower urinals, which directly collect urine and feces and generate energy using multiple ceramic MFCs [

89]. This approach provides concentrated wastewater to the MFCs rather than diluted samples, thereby improving efficiency. On a university campus, a 288-unit MFC system serving 5–10 users daily produced an average of 75 mW, enough to power LED lights directly connected to the MFC stack for 75 hours. During a large music festival with roughly 1,000 users per day, a 432-unit PeePower MFC produced an average of 300 mW, successfully powering internal lighting over a seven-day period [

89].

While PeePower has demonstrated practical success on Earth, similar MFC-based systems for processing urine and feces will need to be evaluated under microgravity conditions. Nonetheless, these studies lay a strong foundation for developing toilet-like MFCs for energy generation on deep space missions. The

Table 3 summarizes different configurations of microbial fuel cells (MFCs), their sizes, number of units, user context, and achieved power output, along with key observations on performance

5. Preliminary Investigation of Kombucha-Based Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs)

Inspired by the fact that several microorganisms were tested already in space, we investigated a symbiotic microbial consortium known as kombucha brewing, which was tested for 18 months on the external panel of the International Space Station [

90]. The wild form of kombucha consists of more than 20 bacteria and yeast species. Our interest in kombucha is related not only with its resistance to space conditions but also because it produces bacterial cellulose which can be used in space for several applications [

91,

92]. One of the problems in the bacterial cellulose production in space or in any isolated environment is carbon, which must be added to the production loop. Organic wastes seem to be one of its sources. During preliminary study we observed promising results to combine multiple functionalities of kombucha in space including generation of electric power in an alternative, sustainable way.

5.1. Experimental

Three laboratory - scale microbial fuel cell (MFC) prototypes were constructed to evaluate the electrochemical activity of kombucha culture (

Figure 6).

Single - chamber configuration: A 250 mL glass vessel filled with freshly prepared kombucha culture served simultaneously as anolyte and catholyte. In kombucha, the microbial cellulose biofilm (SCOBY - symbiotic consortium of bacteria and yeast) naturally develops at the air–liquid interface, where aerobic bacteria and yeasts form a dense layer of cells embedded in cellulose. To exploit this architecture, the anode (graphite, 7 cm²) was positioned directly beneath the biofilm at the surface, ensuring close contact with the metabolically active layer. The cathode (graphite, 7 cm²) was suspended deeper in the bulk liquid, exposed to dissolved oxygen present in the medium. Electrodes were connected through an external resistor (1 kΩ), and voltage was recorded with a digital multimeter.

Dual-chamber (aerated kombucha cathode): Two identical 250 mL chambers were connected by a salt bridge, consisting of a small tube filled with 1 M NaCl solution. The anode chamber contained kombucha culture with a visible cellulose biofilm, while the cathode chamber was filled with kombucha culture subjected to continuous aeration, ensuring oxygen availability as the terminal electron acceptor. Graphite electrodes were positioned analogously to the single-chamber system.

Dual-chamber (ferricyanide cathode – control): Identical to the dual-chamber setup above, except that the cathode chamber contained 50 mM potassium ferricyanide solution as a chemical electron acceptor, serving as a performance benchmark.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the three bioreactor configurations: (a) single-chamber system with natural SCOBY biofilm, (b) dual-chamber system with aerated kombucha cathode, and (c) dual-chamber system with ferricyanide cathode (control).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the three bioreactor configurations: (a) single-chamber system with natural SCOBY biofilm, (b) dual-chamber system with aerated kombucha cathode, and (c) dual-chamber system with ferricyanide cathode (control).

Two nutrient regimes were tested in both configurations:

High-substrate: kombucha supplemented with 10 g·L-1 glucose.

Low-nutrient: kombucha diluted in 0.5% tea infusion with 5 g·L-1 sucrose, simulating a waste-like substrate.

Measurements of voltage were carried out continuously for 7 days. Power density was calculated as:

where:

V is the voltage,

R the external resistance, and

A the electrode area. pH was measured daily.

5.2. Results

All three configurations generated measurable electricity from kombucha cultures, with clear differences in performance. The ferricyanide cathode provided the highest maximum power density, confirming its role as an efficient artificial electron acceptor. The dual-chamber kombucha–aerated system reached intermediate values, while the single-chamber setup demonstrated the longest operational stability, albeit at lower power density.

Table 4.

Performance of kombucha-based MFCs under different configurations.

Table 4.

Performance of kombucha-based MFCs under different configurations.

| Configuration |

Substrate regime |

Max. voltage (mV) |

Max. power density (mW/m²) |

Operational stability (days) |

Final pH |

| Single-chamber |

High-substrate |

410 ± 15 |

125 ± 6 |

5 |

4.9 |

| Single-chamber |

Low-nutrient |

285 ± 12 |

82 ± 5 |

7 |

5.2 |

Dual-chamber

(kombucha anode

+ aerated kombucha cathode)

|

High-substrate |

495 ± 18 |

154 ± 8 |

4 |

4.8 |

Dual-chamber

(kombucha anode

+ aerated kombucha cathode)

|

Low-nutrient |

345 ± 15 |

104 ± 6 |

6 |

5.1 |

Dual-chamber

(kombucha anode

+ ferricyanide cathode, control)

|

High-substrate |

530 ± 20 |

168 ± 9 |

4 |

4.7 |

Dual-chamber

(kombucha anode

+ ferricyanide cathode, control)

|

Low-nutrient |

360 ± 14 |

110 ± 7 |

6 |

5.1 |

The experiments confirmed that kombucha-based consortia are capable of functioning as active biocatalysts in microbial fuel cells. The high-substrate regimes produced higher maximum voltages and power densities, reflecting intensified microbial metabolism. However, they were limited by faster substrate depletion and acidification of the medium. In contrast, low-nutrient regimes yielded lower but more stable outputs, suggesting their potential relevance for space habitat conditions where waste-derived substrates are predominant.

The dual-chamber configuration enhanced peak performance due to improved separation of oxidation and reduction processes, but at the expense of system simplicity. Conversely, the single-chamber design represents a robust, low-maintenance option, demonstrating the feasibility of direct electricity generation from kombucha cultures without external mediators.

These preliminary findings highlight kombucha as a promising and resilient microbial consortium for MFC applications, with flexibility across different system architectures. Importantly, the aerated kombucha cathode configuration provides a more sustainable alternative to chemical catholytes, aligning with the goals of closed-loop biotechnologies in space exploration. However, these results are preliminary and warrant further investigation to fully understand their potential and limitations.

6. Future Prospects and Conclusions

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) and related bioelectrochemical systems offer promising solutions for energy generation and waste recycling in long-duration space missions, from the ISS to Artemis and future Mars expeditions. These systems can complement conventional power sources, converting crew - generated organic waste, metabolic byproducts, and algal biomass into electricity while supporting closed-loop life-support strategies.

Ground - based simulations of microgravity, radiation, and closed ecosystems, along with real - space experiments such as BioServe and ESA’s MELiSSA, demonstrate that selected microbial consortia maintain functionality under space - relevant stressors. These studies highlight the feasibility of MFC integration in extraterrestrial habitats, emphasizing critical factors including substrate availability, system design, and radiation protection. Overall, bioelectrochemical systems present a multifunctional approach to sustainable energy and waste management in space, warranting further research on stability, miniaturization, and operational reliability for future missions.

References

- M. Nasrollahzadeh, S.M. Sajadi, M. Sajjadi, Z. Issaabadi, Chapter 1 - An Introduction to Nanotechnology, Interface Science and Technology 28 (2019) 1-27. [CrossRef]

- M.H.K. Manesh, S. Davadgaran, S.A.M. Rabeti, Experimental study of biological wastewater recovery using microbial fuel cell and application of reliability and machine learning to predict the system behavior, Energy Conversion and Management 314 (2024) 118658. [CrossRef]

- E.T. Sayed, J.B.M. Parambath, M.A. Abdelkareem, H. Alawadhi, A.G. Olabi, Ni-based metal organic frameworks doped with reduced graphene oxide as an effective anode catalyst in direct ethanol fuel cell, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 970 (2024) 173194. [CrossRef]

- Unuofin, J.O., Iwarere, S.A. & Daramola, M.O. Embracing the future of circular bio-enabled economy: unveiling the prospects of microbial fuel cells in achieving true sustainable energy. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30, 90547–90573 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Xia, D. Zhang, W. Pedrycz, Y. Zhu, Y. Guo, Models for Microbial Fuel Cells: A critical review, Journal of Power Sources 373 (2018) 119–131. [CrossRef]

- R. Kaur, A. Marwaha, V.A. Chhabra, K.-H. Kim, S.K. Tripathi, Recent developments on functional nanomaterial-based electrodes for microbial fuel cells, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 119 (2020) 109551. [CrossRef]

- C. Santoro, C. Arbizzani, B. Erable, I. Ieropoulos, Microbial fuel cells: From fundamentals to applications. A review, Journal of Power Sources 356 (2017) 225–244. [CrossRef]

- R.S. Chouhan, S. Gandhi, S.K. Verma, I. Jerman, S. Baker, M. Štrok, Recent advancements in the development of Two-Dimensional nanostructured based anode materials for stable power density in microbial fuel cells, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 188 (2023) 113813. [CrossRef]

- N.K. Abd-Elrahman, N. Al-Harbi, N.M. Basfer, Y. Al-Hadeethi, A. Umar, S. Akbar, Applications of Nanomaterials in Microbial Fuel Cells: A Review, Molecules 27 (21) (2022) 7483. [CrossRef]

- A.V. Sonawane, S. Rikame, S.H. Sonawane, M. Gaikwad, B. Bhanvase, S.S. Sonawane, A.K. Mungray, R. Gaikwad, A review of microbial fuel cell and its diversification in the development of green energy technology, Chemosphere 350 (2024) 141127. [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.S. Role of Graphene-Silver Nanocomposite as Anode to Boost Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell Performance. Chemistry Africa 7, 4555–4567 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Q. Hassan, P. Viktor, T.J. Al-Musawi, B.M. Ali, S. Algburi, H.M. Alzoubi, A.K. Al-Jiboory, A.Z. Sameen, H.M. Salman, M. Jaszczur, The renewable energy role in the global energy transformations, Renewable Energy Focus 48 (2024) 100545. [CrossRef]

- Koehle, A.P., Brumwell, S.L., Seto, E.P. et al. Microbial applications for sustainable space exploration beyond low Earth orbit. npj Microgravity 9, 47 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Santomartino, R., Averesch, N.J.H., Bhuiyan, M. et al. Toward sustainable space exploration: a roadmap for harnessing the power of microorganisms. Nat Commun 14, 1391 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Keller, R. J. et al. Biologically-based and physiochemical life support and in situ resource utilization for exploration of the solar system—reviewing the current state and defining future development needs. Life 11, 844 1–41 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Nangle, S.N., Wolfson, M.Y., Hartsough, L. et al. The case for biotech on Mars. Nat Biotechnol 38, 401–407 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Averesch, N.J.H., Berliner, A.J., Nangle, S.N. et al. Microbial biomanufacturing for space-exploration—what to take and when to make. Nat Commun 14, 2311 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, C.A., Medina-Colorado, A.A., Barrila, J. et al. A vision for spaceflight microbiology to enable human health and habitat sustainability. Nat Microbiol 7, 471–474 (2022). [CrossRef]

- de Vet, S.J., Rutgers, R. From waste to energy: First experimental bacterial fuel cells onboard the international space station. Microgravity Sci. Technol 19, 225–229 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. R., & Johnson, J. A. (2014). Advanced propulsion systems for deep space missions (NASA/TM-2014-11263). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20140011263.

- Electrified bacteria clean wastewater, generate power. NASA Spinoff. (2019) https://spinoff.nasa.gov/Spinoff2019/ee_1.html.

- Dakal, T.C., Singh, N., Kaur, A. et al. New horizons in microbial fuel cell technology: applications, challenges, and prospects. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 18, 79 (2025). [CrossRef]

- K. Kižys, A. Zinovičius, B. Jakštys, I. Bružaitė, E. Balčiūnas, M. Petrulevičienė, A. Ramanavičius, I. Morkvėnaitė-Vilkončienė, Microbial Biofuel Cells: Fundamental Principles, Development and Recent Obstacles, Biosensors 13 (2) (2023) 221. [CrossRef]

- A. Arkatkar, A.K. Mungray, P. Sharma, Study of electrochemical activity zone of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in microbial fuel cell, Process Biochemistry 101 (2021) 213–217. [CrossRef]

- T. Lin, X. Bai, Y. Hu, B. Li, Y.-J. Yuan, H. Song, Y. Yang, J. Wang, Synthetic Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Shewanella oneidensis consortium enables glucose-fed high-performance microbial fuel cell, AIChE Journal (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kondaveeti, S., Lee, S.-H., Park, H.-D. & Min, B. Specific enrichment of different Geobacter sp. in anode biofilm by varying interspatial distance of electrodes in air-cathode microbial fuel cell (MFC). Electrochim. Acta 331, 135388 (2020). [CrossRef]

- O.M. Vasyliv, O.D. Maslovska, Y.P. Ferensovych, O.I. Bilyy, S.O. Hnatush, Interconnection between tricarboxylic acid cycle and energy generation in microbial fuel cell performed by Desulfuromonas acetoxidans IMV B-7384, Proceedings of SPIE 9493 (2015) 94930J. [CrossRef]

- A. Nawaz, I. ul Haq, K. Qaisar, B. Gunes, S. Ibadat Raja, K. Mohyuddin, H. Amin, Microbial fuel cells: Insight into simultaneous wastewater treatment and bioelectricity generation, Process Safety and Environmental Protection 161 (2022) 357–373. [CrossRef]

- M. Tatinclaux, K. Gregoire, A. Leininger, J.C. Biffinger, L. Tender, M. Ramirez, A. Torrents, B.V. Kjellerup, Electricity generation from wastewater using a floating air cathode microbial fuel cell, Water-Energy Nexus 1 (2) (2018) 97–103. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar, L. Singh, A.W. Zularisam, F.I. Hai, Microbial fuel cell is emerging as a versatile technology: a review on its possible applications, challenges and strategies to improve the performances, International Journal of Energy Research 42 (2) (2018) 369–394. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar, L. Singh, A.W. Zularisam, Exoelectrogens: recent advances in molecular drivers involved in extracellular electron transfer and strategies used to improve it for microbial fuel cell applications, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 56 (2016) 1322–1336. [CrossRef]

- G. Reguera, Microbial nanowires and electroactive biofilms, FEMS Microbiology Ecology 94 (7) (2018) fiy086. [CrossRef]

- M. Rahimnejad, A. Adhami, S. Darvari, A. Zirepour, S.-E. Oh, Microbial fuel cell as new technology for bioelectricity generation: A review, Alexandria Engineering Journal 54 (3) (2015) 745–756. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Patrick, Handbook of fuel cells. Fundamentals, technology and applications: Wolf Vielstich, Arnold Lamm, Hubert A. Gasteiger (Eds.), Fuel 83 (4–5) (2004) 623. [CrossRef]

- G.C. Gil, I.S. Chang, B.H. Kim, M. Kim, J.K. Jang, H.S. Park, H.J. Kim, Operational parameters affecting the performance of a mediator-less microbial fuel cell, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 18 (4) (2003) 327–334. [CrossRef]

- Reguera, G., McCarthy, K., Mehta, T. et al. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435, 1098–1101 (2005). [CrossRef]

- I.A. Ieropoulos, J. Greenman, C. Melhuish, J. Hart, Comparative study of three types of microbial fuel cell, Enzyme and Microbial Technology 37 (2) (2005) 238–245. [CrossRef]

- D.R. Lovley, Microbial fuel cells: novel microbial physiologies and engineering approaches, Current Opinion in Biotechnology 17 (3) (2006) 327–332. [CrossRef]

- X.M. Li, K.Y. Cheng, A. Selvam, J.W.C. Wong, Bioelectricity production from acidic food waste leachate using microbial fuel cells: Effect of microbial inocula, Process Biochemistry 48 (2) (2013) 283–288. [CrossRef]

- L.-P. Fan, S. Xue, Overview on Electricigens for Microbial Fuel Cell, The Open Biotechnology Journal 10 (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. Nawaz, A. Hafeez, S.Z. Abbas, I. ul Haq, H. Mukhtar, M. Rafatullah, A state of the art review on electron transfer mechanisms, characteristics, applications and recent advancements in microbial fuel cells technology, Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews 13 (4) (2020) 365–381. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Shehab, J.F. Ortiz-Medina, K.P. Katuri, A.R. Hari, G. Amy, B.E. Logan, P.E. Saikaly, Enrichment of extremophilic exoelectrogens in microbial electrolysis cells using Red Sea brine pools as inocula, Bioresource Technology 239 (2017) 82–86. [CrossRef]

- D.R. Lovley, S.J. Giovannoni, D.C. White, J.E. Champine, E.J. Phillips, Y.A. Gorby, S. Goodwin, Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals, Archives of Microbiology 159(4) (1993) 336–344. [CrossRef]

- Y.A. Gorby, S. Yanina, J.S. McLean, K.M. Rosso, D. Moyles, A. Dohnalkova, T.J. Beveridge, I.S. Chang, B.H. Kim, K.S. Kim, D.E. Culley, S.B. Reed, M.F. Romine, D.A. Saffarini, E.A. Hill, L. Shi, D.A. Elias, D.W. Kennedy, G. Pinchuk, K. Watanabe, S. Ishii, B. Logan, K.H. Nealson, J.K. Fredrickson, Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103(30) (2006) 11358–11363. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Mu, H., Liu, W. et al. Electricigens in the anode of microbial fuel cells: pure cultures versus mixed communities. Microb Cell Fact 18, 39 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S.N. Dedysh, J.S. Sinninghe Damsté, Acidobacteria, Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (2018). [CrossRef]

- O.N. Tiwari, B. Bhunia, A. Mondal, K. Gopikrishna, T. Indrama, System metabolic engineering of exopolysaccharide-producing cyanobacteria in soil rehabilitation by inducing the formation of biological soil crusts: A review, Journal of Cleaner Production, 211 (2019) 70–82. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao, H. Zhang, H. Liu, W. Liu, R. Zhang, M. Xian, H. Liu, Biosynthesis and production of sabinene: current state and perspectives, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102 (2018) 1535–1544. [CrossRef]

- G. Reguera, K.P. Nevin, J.S. Nicoll, S.F. Covalla, T.L. Woodard, D.R. Lovley, Biofilm and nanowire production leads to increased current in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72 (11) (2006) 7345–7348. 7345–7348.

- H.J. Kim, H.S. Park, M.S. Hyun, I.S. Chang, M. Kim, B.H. Kim, A mediator-less microbial fuel cell using a metal reducing bacterium, Shewanella putrefaciens, Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 30 (2002) 145–152. [CrossRef]

- D.H. Park, J.G. Zeikus, Electricity generation in microbial fuel cells using neutral red as an electronophore, Applied and Environmental Microbiology 66 (4) (2000) 1292–1297. [CrossRef]

- C. Munoz-Cupa, Y. Hu, C. Xu, A. Bassi, An overview of microbial fuel cell usage in wastewater treatment, resource recovery and energy production, Science of The Total Environment 754 (2021) 142429. [CrossRef]

- D. Cecconet, D. Molognoni, A. Callegari, A.G. Capodaglio, Agro-food industry wastewater treatment with microbial fuel cells: Energetic recovery issues, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 43 (1) (2018) 500–511. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosenbaum, U. Schröder, F. Scholz, In situ electrooxidation of photobiological hydrogen in a photobioelectrochemical fuel cell based on Rhodobacter sphaeroides, Environmental Science & Technology 39 (16) (2005) 6328–6333. [CrossRef]

- A.D. Tharali, N. Sain, W.J. Osborne, Microbial fuel cells in bioelectricity production, Frontiers in Life Science 9 (4) (2016) 252–266. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Marcus, B. Rittmann, New insights into fuel cell that uses bacteria to generate electricity from waste, News Archive of the Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University (2008).

- E. Marsili, J.B. Rollefson, D.B. Baron, R.M. Hozalski, D.R. Bond, Microbial biofilm voltammetry: direct electrochemical characterization of catalytic electrode-attached biofilms, Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74 (23) (2008) 7329–7337. [CrossRef]

- B. Gunes, A critical review on biofilm-based reactor systems for enhanced syngas fermentation processes, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 143 (2021) 110950. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Slate, K.A. Whitehead, D.A. Brownson, C.E. Banks, Microbial fuel cells: An overview of current technology, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 101 (2019) 60–81. [CrossRef]

- J. An, H.S. Lee, Occurrence and implications of voltage reversal in stacked microbial fuel cells, ChemSusChem 7 (6) (2014) 1689–1695. [CrossRef]

- S.G. Flimban, T. Kim, I.M.I. Ismail, S.E. Oh, Overview of Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC) Recent Advancement from Fundamentals to Applications: MFC Designs, Major Elements, and Scalability (2018). [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, J. Li, X. Zhu, D.D. Ye, Q. Fu, Q. Liao, Response of stacked microbial fuel cells with serpentine flow fields to variable operating conditions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 42 (45) (2017) 27641–27648. [CrossRef]

- S.G. Flimban, I.M. Ismail, T. Kim, S.E. Oh, Overview of recent advancements in the microbial fuel cell from fundamentals to applications: Design, major elements, and scalability, Energies 12 (17) (2019) 3390. [CrossRef]

- A. Vilajeliu-Pons, S. Puig, I. Salcedo-Dávila, M.D. Balaguer, J. Colprim, Long-term assessment of six-stacked scaled-up MFCs treating swine manure with different electrode materials, Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 3 (2017) 947–959. [CrossRef]

- H. Bird, E.S. Heidrich, D.D. Leicester, P. Theodosiou, Pilot-scale Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs): A meta-analysis study to inform full-scale design principles for optimum wastewater treatment, Journal of Cleaner Production 346 (2022) 131227. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Yaqoob, M.N.M. Ibrahim, M. Rafatullah, Y.S. Chua, A. Ahmad, K. Umar, Recent Advances in Anodes for Microbial Fuel Cells: An Overview, Materials (Basel) 13 (9) (2020) 2078. [CrossRef]

- P. Jalili, A. Ala, P. Nazari, B. Jalili, D.D. Ganji, A comprehensive review of microbial fuel cells considering materials, methods, structures, and microorganisms, Heliyon 10 (3) (2024) e25439. [CrossRef]

- S.Y. Sawant, T.H. Han, M.H. Cho, Metal-free carbon-based materials: Promising electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cells, International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18 (1) (2017) 25. [CrossRef]

- M. Kodali, S. Herrera, S. Kabir, A. Serov, C. Santoro, I. Ieropoulos, P. Atanassov, Enhancement of microbial fuel cell performance by introducing a nano-composite cathode catalyst, Electrochimica Acta 265 (2018) 56–64. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, Y. Wang, X. Han, Y. Shan, F. Li, L. Shi, Biofilm biology and engineering of Geobacter and Shewanella spp. for energy applications, Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 9 (2021) 786416. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R., Dash, J., Satpathy, S.S. et al. A brief review on factors affecting the performance of microbial fuel cell and integration of artificial intelligence. Discov Sustain 6, 702 (2025). [CrossRef]

- A. Banerjee, R.K. Calay, F.E. Eregno, Role and important properties of a membrane with its recent advancement in a microbial fuel cell, Energies 15 (2) (2022) 444. [CrossRef]

- R. Jenani, S. Karishmaa, A.B. Ponnusami, P.S. Kumar, G. Rangasamy, A recent development of low-cost membranes for microbial fuel cell applications, Desalination and Water Treatment 320 (2024) 100698. [CrossRef]

- R.P. Pinto, B. Srinivasan, S.R. Guiot, B. Tartakovsky, The effect of real-time external resistance optimization on microbial fuel cell performance, Water Research 45 (4) (2011) 1571–1578. [CrossRef]

- López Zavala, M. Á., & Cámara Gutiérrez, I. C. (2023). Effects of external resistance, new electrode material, and catholyte type on the energy generation and performance of dual-chamber microbial fuel cells. Fermentation, 9(4), 344. [CrossRef]

- R. Santomartino, N.J.H. Averesch, M. Bhuiyan, C.S. Cockell, J. Colangelo, Y. Gumulya, … R. Volger, Biologically facilitated processes towards sustainable space exploration. White paper prepared for NASEM Decadal Survey on Biological and Physical Sciences Research in Space 2023–2032, UK Centre for Astrobiology, University of Edinburgh, 2021. https://surveygizmoresponseuploads.s3.amazonaws.com/fileuploads/623127/6378869/143-04a1ffaf4358b71a08fc883758723d79_SantomartinoRosa.pdf.

- J. Fahrion, F. Mastroleo, C.-G. Dussap, N. Leys, Use of photobioreactors in regenerative life support systems for human space exploration, Frontiers in Microbiology 12 (2021) 699525. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Vishwanathan, Microbial fuel cells: A comprehensive review for beginners, 3 Biotech 11 (5) (2021) 248. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, K. Ren, Y. Zhu, J. Huang, S. Liu, A review of recent advances in microbial fuel cells: Preparation, operation, and application, BioTech 11 (4) (2022) 44. [CrossRef]

- I. Ieropoulos, J. Greenman, C. Melhuish, Urine utilisation by microbial fuel cells: Energy fuel for the future, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 14 (2012) 94–98. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Cid, A. Stinchcombe, I. Ieropoulos, M.R. Hoffmann, Urine microbial fuel cells in a semi-controlled environment for onsite urine pre-treatment and electricity production, Journal of Power Sources 400 (2018) 441–448. [CrossRef]

- S. Lu, X. Zhang, J. Li, Y. Wang, Y. Zhao, Resource recovery microbial fuel cells for urine-containing wastewater treatment without external energy consumption, Chemical Engineering Journal 373 (2019) 1072–1080. [CrossRef]

- N. Yang, H. Liu, X. Jin, D. Li, G. Zhan, One-pot degradation of urine wastewater by combining simultaneous halophilic nitrification and aerobic denitrification in air-exposed biocathode microbial fuel cells (AEB-MFCs), Science of The Total Environment 748 (2020) 141379. [CrossRef]

- D.F. Putnam, Composition and concentrative properties of human urine (NASA Contractor Report), McDonnell Douglas Astronautics Company – Western Division, Huntington Beach, CA, 1971.

- X. Cao, Y. Hou, H. Sun, Z. Wu, A new method for water desalination using microbial desalination, Environmental Science & Technology 43 (2009) 7148–7152. [CrossRef]

- F. Fangzhou, L. Zhenglong, Y. Shaoqiang, X. Beizhen, L. Hong, Electricity generation directly using human feces wastewater for life support system, Acta Astronautica 68 (2011) 1537–1547. [CrossRef]

- A. Colombo, F. Cid, I. Ieropoulos, Signal trends of microbial fuel cells fed with different food-industry residues, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 42 (2017) 1841–1852. [CrossRef]

- I. Gajda, Miniaturized ceramic-based microbial fuel cell for efficient power generation from urine and stack development, Frontiers in Energy Research 6 (2018) 84. [CrossRef]

- I.A. Ieropoulos, R. Greenman, C. Melhuish, Pee power urinal microbial fuel cell technology field trials in the context of sanitation, Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2 (2016) 336–343. [CrossRef]

- N. Kozyrovska, O. Reva, O. Podolich, O. Kukharenko, I. Orlovska, V. Terzova, G. Zubova, U. Trovatti, A.P. Uetanabaro, A. Góes-Neto, V. Azevedo, D. Barh, C. Verseux, D. Billi, A.M. Kołodziejczyk, B. Foing, R. Demets, J.-P. Vera, To other planets with upgraded millennial Kombucha in rhythms of sustainability and health support, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 8 (2021) 701158. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Kołodziejczyk, M. Silarski, M. Kaczmarek, M. Harasymczuk, K. Dziedzic-Kocurek, T. Uhl, Shielding properties of the kombucha-derived bacterial cellulose, Cellulose 32 (2025) 1017–1033. [CrossRef]

- O. Podolich, O. Kukharenko, A. Haidak, I. Zaets, L. Zaika, O. Storozhuk, L. Palchikovska, I. Orlovska, O. Reva, T. Borisova, L. Khirunenko, M. Sosnin, E. Rabbow, V. Kravchenko, M. Skoryk, M. Kremenskoy, R. Demets, K. Olsson-Francis, N. Kozyrovska, J.-P. de Vera, Multimicrobial kombucha culture tolerates Mars-like conditions simulated on low Earth orbit, Astrobiology 19 (2019) 123–136. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).