Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Procedure

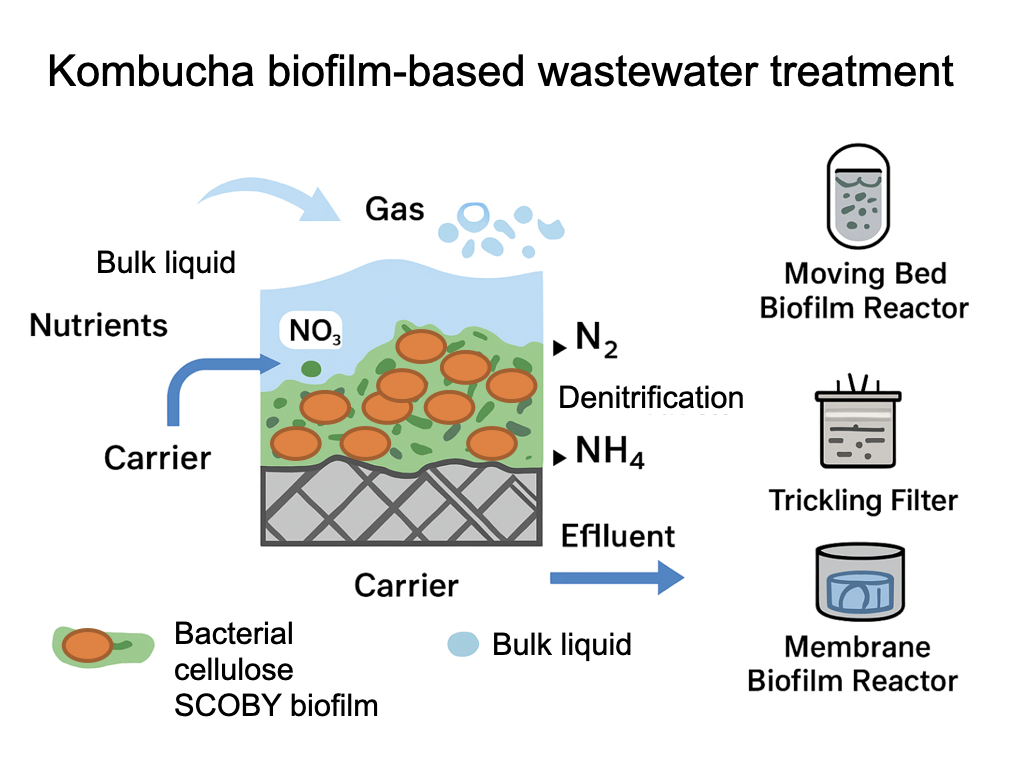

Principle of Operation

Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

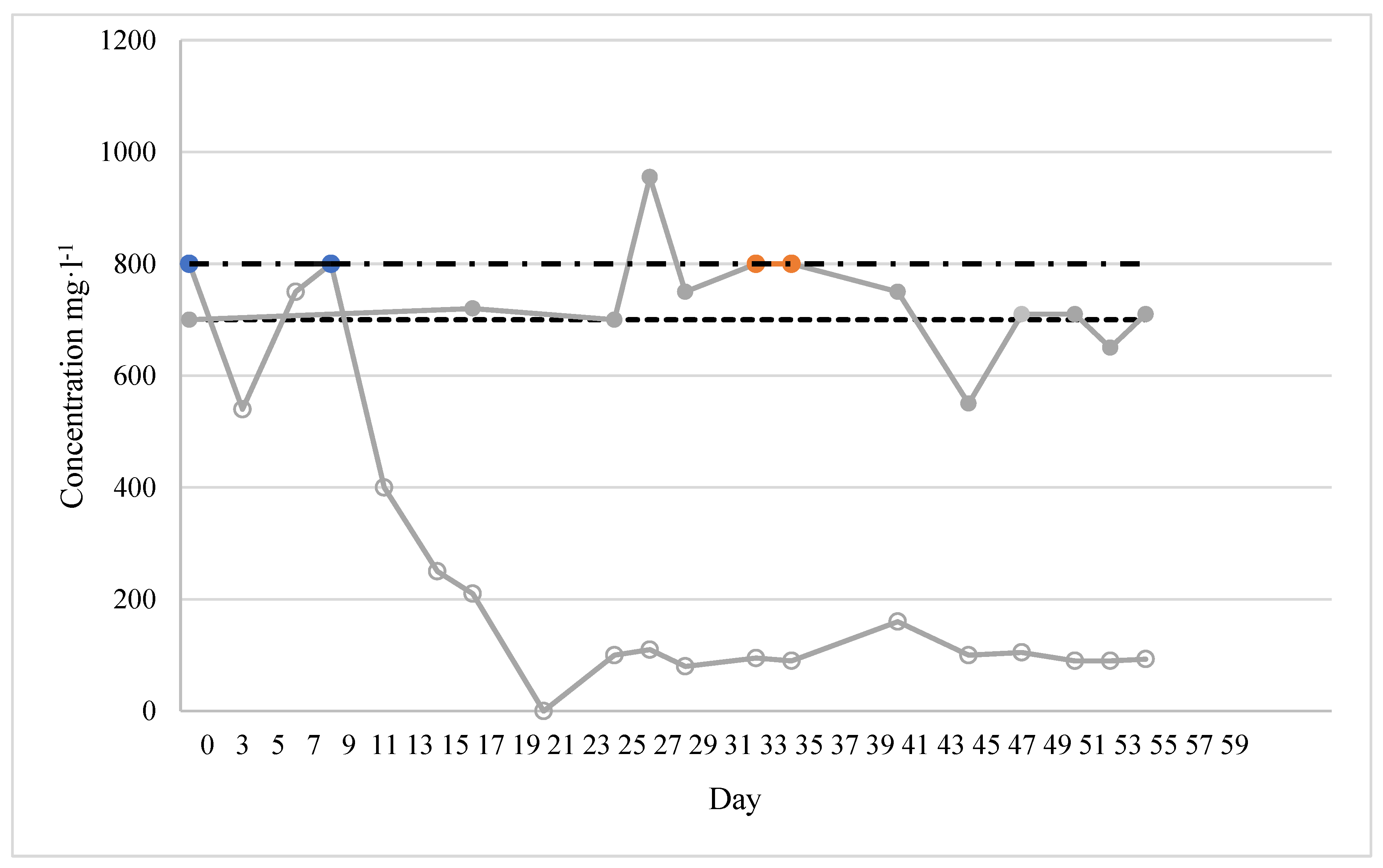

3.1. First Kombucha-PBR Experiment

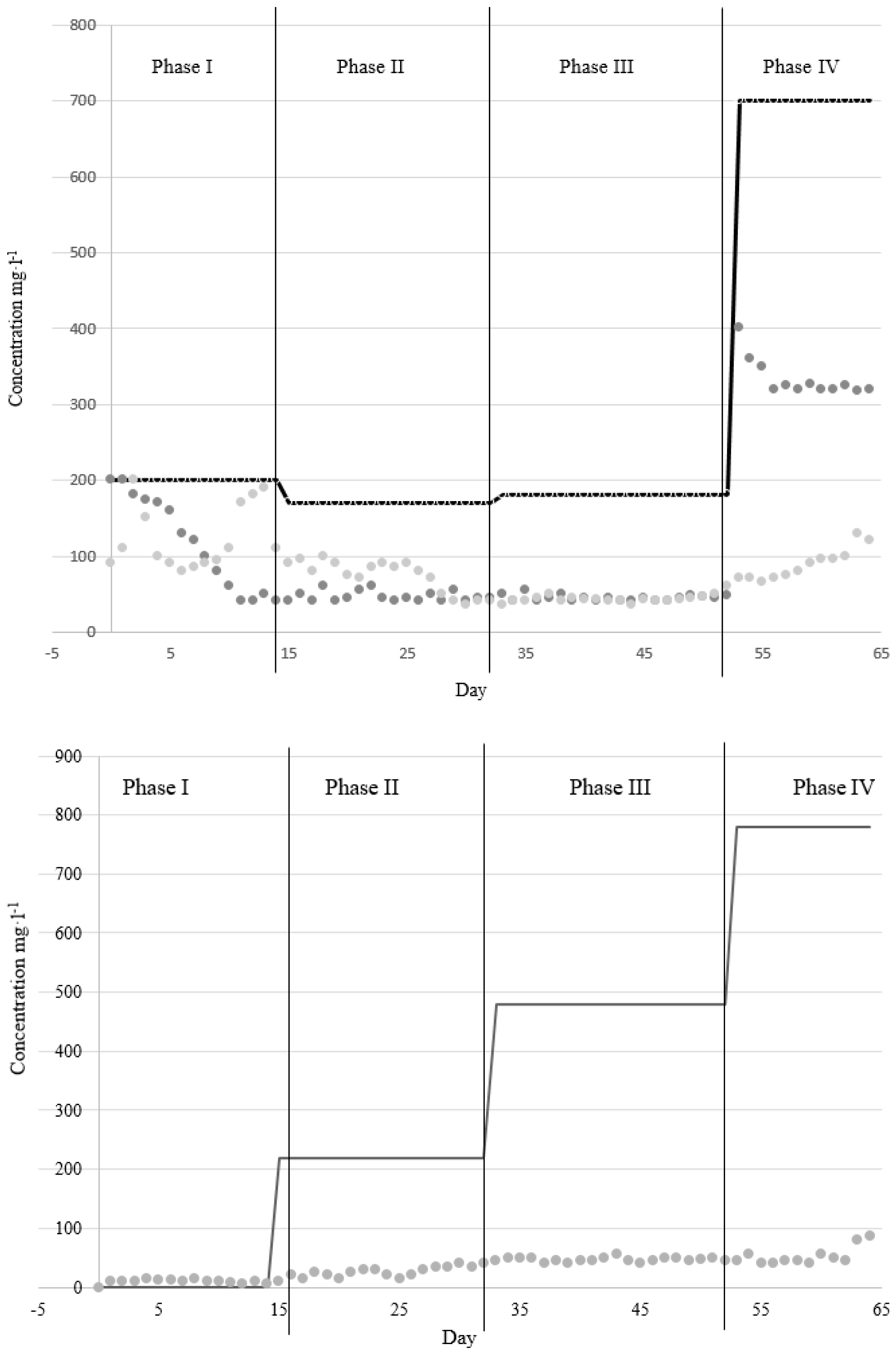

3.2. Second Kombucha-PBR Experiment

4. Conclusion

References

- Zhang K, Choi H, Dionysiou DD, Oerther DB. Application of membrane bioreactors in the preliminary treatment of early planetary base wastewater for long-duration space missions. Water Environ Res. 2008 Dec;80(12):2209-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque A, Kreuzberg K. Bioregenerative life support as self-sustaining ecosystem in space. Microgravity Sci Technol. 1993 Mar;6(1):43-54. [PubMed]

- Walther I. Space bioreactors and their applications. Adv Space Biol Med. 2002;8:197-213. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Ortiz EJ, Gerlach R, Peyton BM, Roberson L, Yeh DH. Biofilm reactors for the treatment of used water in space:potential, challenges, and future perspectives. Biofilm. 2023 Jul 15;6:100140. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee H, Diao J, Tian Y, Guleria R, Lee E, Smith A, Savage M, Yeh D, Roberson L, Blenner M, Tang YJ, Moon TS. Developing an alternative medium for in-space biomanufacturing. Nat Commun. 2025 Jan 16;16(1):728. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farges B, Poughon L, Creuly C, Cornet JF, Dussap CG, Lasseur C. Dynamic aspects and controllability of the MELiSSA project: a bioregenerative system to provide life support in space. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2008 Dec;151(2-3):686-99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen RD, Semmens MJ, LaPara TM. Biological treatment of a synthetic space mission wastewater using a membrane-aerated, membrane-coupled bioreactor (M2BR). J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008 Jun;35(6):465-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D. P. et al. (2003). Treatment of Spacecraft Wastewater Using a Hollow Fiber Membrane Biofilm Redox Control Reactor. NASA Research Reports: NASA/ASEE Fellowship Program.

- Shull, S.; Meyer, C.; et al. (2014). Biological Water Processor and Forward Osmosis Secondary Treatment. NASA Technical Report (JSC-CN-32364).

- Espinosa-Ortiz EJ, Rene ER, Gerlach R. Potential use of fungal-bacterial co-cultures for the removal of organic pollutants. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2022 May;42(3):361-383. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strayer, R., Hummerick, M., Garland, J., Roberts, M. et al., “Treatment of Spacecraft Wastewater in a Submerged-Membrane Biological Reactor,” SAE Technical Paper 2003-01-2556, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Bovendeur J. 1989. Fixed-Biofilm Reactors applied for waste water treatment and aquacultural water recirculating systems. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/201970.

- Sheng GP, Yu HQ, Li XY. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of microbial aggregates in biological wastewater treatment systems: a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2010 Nov-Dec;28(6):882-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahto KU, Das S. Bacterial biofilm and extracellular polymeric substances in the moving bed biofilm reactor for wastewater treatment: A review. Bioresour Technol. 2022 Feb;345:126476. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy L, Zhu X, Dong G, Selli S, Kelebek H, Sullivan C, Tiwari U, Tiwari BK. Investigation into the use of novel pretreatments in the fermentation of Alaria esculenta by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and kombucha SCOBY. Food Chem. 2024 Jun 1;442:138335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi D, Liu T. Versatile Gas-Transfer Membrane in Water and Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Opportunities, and Challenges. ACS Environ Au. 2025 Jan 29;5(2):152-164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hupka M, Kedia R, Schauer R, Shepard B, Granados-Presa M, Vande Hei M, Flores P, Zea L. Morphology of Penicillium rubens Biofilms Formed in Space. Life (Basel). 2023 Apr 13;13(4):1001. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen HN, Sharp GM, Stahl-Rommel S, Velez Justiniano YA, Castro CL, Nelman-Gonzalez M, O’Rourke A, Lee MD, Williamson J, McCool C, Crucian B, Clark KW, Jain M, Castro-Wallace SL. Microbial isolation and characterization from two flex lines from the urine processor assembly onboard the international space station. Biofilm. 2023 Mar 2;5:100108. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim W, Tengra FK, Young Z, Shong J, Marchand N, Chan HK, Pangule RC, Parra M, Dordick JS, Plawsky JL, Collins CH. Spaceflight promotes biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One. 2013 Apr 29;8(4):e62437. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flores P, Luo J, Mueller DW, Muecklich F, Zea L. Space biofilms - An overview of the morphology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms grown on silicone and cellulose membranes on board the international space station. Biofilm. 2024 Feb 5;7:100182. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Checinska Sielaff A, Urbaniak C, Mohan GBM, Stepanov VG, Tran Q, Wood JM, Minich J, McDonald D, Mayer T, Knight R, Karouia F, Fox GE, Venkateswaran K. Characterization of the total and viable bacterial and fungal communities associated with the International Space Station surfaces. Microbiome. 2019 Apr 8;7(1):50. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gu JD, Roman M, Esselman T, Mitchell R. The role of microbial biofilms in deterioration of space station candidate materials. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 1998;41(1):25-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, A., Dixit, A. R., Khodadad, C. L. M., Hummerick, M. E., Justiano-Velez, Y. A., Li, W., O’Rourke, A., et al. (2023). Biofilm formation is correlated with low nutrient and simulated microgravity conditions in a Burkholderia isolate from the ISS Water Processor Assembly (WPA). Biofilm, 5, 100110. [CrossRef]

- Zea L, McLean RJC, Rook TA, Angle G, Carter DL, Delegard A, Denvir A, Gerlach R, Gorti S, McIlwaine D, Nur M, Peyton BM, Stewart PS, Sturman P, Velez Justiniano YA. Potential biofilm control strategies for extended spaceflight missions. Biofilm. 2020 May 30;2:100026. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ojo, A.O.; de Smidt, O. Microbial Composition, Bioactive Compounds, Potential Benefits and Risks Associated with Kombucha: A Concise Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolich O, Zaets I, Kukharenko O, Orlovska I, Reva O, Khirunenko L, Sosnin M, Haidak A, Shpylova S, Rabbow E, Skoryk M, Kremenskoy M, Demets R, Kozyrovska N, de Vera JP. Kombucha Multimicrobial Community under Simulated Spaceflight and Martian Conditions. Astrobiology. 2017 May;17(5):459-469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana de Carvalho D, Trovatti Uetanabaro AP, Kato RB, Aburjaile FF, Jaiswal AK, Profeta R, De Oliveira Carvalho RD, Tiwar S, Cybelle Pinto Gomide A, Almeida Costa E, Kukharenko O, Orlovska I, Podolich O, Reva O, Ramos PIP, De Carvalho Azevedo VA, Brenig B, Andrade BS, de Vera JP, Kozyrovska NO, Barh D, Góes-Neto A. The Space-Exposed Kombucha Microbial Community Member Komagataeibacter oboediens Showed Only Minor Changes in Its Genome After Reactivation on Earth. Front Microbiol. 2022 Mar 11;13:782175. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boavida-Dias, R.; Silva, J.R.; Santos, A.D.; Martins, R.C.; Castro, L.M.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M. A Comparison of Biosolids Production and System Efficiency between Activated Sludge, Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor, and Sequencing Batch Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor in the Dairy Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi N, Annous BA, Ezeji TC, Karcher P, Maddox IS. Biofilm reactors for industrial bioconversion processes: employing potential of enhanced reaction rates. Microb Cell Fact. 2005 Aug 25;4:24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forbis-Stokes AA, Rocha-Melogno L, Deshusses MA. Nitrifying trickling filters and denitrifying bioreactors for nitrogen management of high-strength anaerobic digestion effluent. Chemosphere. 2018 Aug;204:119-129. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen RD, Semmens MJ, LaPara TM. Biological treatment of a synthetic space mission wastewater using a membrane-aerated, membrane-coupled bioreactor (M2BR). J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008 Jun;35(6):465-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. E. Verostko, “Ersatz wastewater formulations for testing water recovery systems,” 34th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), Colorado Springs, CO, Society of Automotive Engineers, 2004, Paper #2004-01-2448. [CrossRef]

- Kosgey K, Zungu PV, Bux F, Kumari S. Biological nitrogen removal from low carbon wastewater. Front Microbiol. 2022 Nov 16;13:968812. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, Y., Lu, X., Zhao, M., Ding, X., Lv, H., Wang, L., & Wu, L. (2023). The impact of external plant carbon sources on nitrogen removal and microbial community structure in vertical flow constructed wetlands. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kosgey K, Zungu PV, Bux F, Kumari S. Biological nitrogen removal from low carbon wastewater. Front Microbiol. 2022 Nov 16;13:968812. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Component | Component Quantity (per L) |

|---|---|

| Shampoo (suave for kids) | 300 mg |

| Ammonium bicarbonate | 2.3 g |

| Ammonium hydroxide | 300 mg |

| Ammonium citrate | 370 mg |

| Ammonium formate | 45 mg |

| Ammonium oxalate monohydrate | 20 mg |

| Sodium chloride | 690 mg |

| Potassium chloride | 200 mg |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 200 mg |

| Potassium phosphate monobasic | 166 mg |

| Potassium sulfate | 690 mg |

| Urea | 160 mg |

| Lactic acid | 80 mg |

| Creatinine | 160 mg |

| Histidine | 29 mg |

| Taurine | 17 mg |

| Glutamic acid | 51 mg |

| Glucose | 78 mg |

| Acetic acid | 34 mL |

| Benzoic acid | 1 mg |

| Benzyl alcohol | 5 µL |

| Ethanol | 6.5 mL |

| Acetone | 0.5 µL |

| Caprolactam | 4 mg |

| Phenol | 0.6 mg |

| N,N-dimethylformamide | 0.7 µL |

| Ethylene glycol | 3.3 µL |

| 4-Ethyl morpholine | 1.5 µL |

| Formaldehyde | 3 µL |

| Formic acid | 4.4 µL |

| Methanol | 7.6 µL |

| 1,2-Propanediol | 2 µL |

| Propanol | 2.4 µL |

| Propionic acid | 15 µL |

| Reactor |

System configuration

and operational conditions |

|---|---|

| Pack-Bed reactor (PBR) |

System configuration Wastewater: modified EPB Ersatz (DOC 239–272 mg·L-1, 4:1 COD to N ratio, COD 800 mg·L-1, TN 700 mg·L-1). Packed-bed (Up-flow) Reactor: acrylic cylinder; dimensions: ID = X cm, L = Y cm; TV = V m3. Packing material: bacterial cellulose Z m2. Gas supplied: air (1.5 L·min-1); System operation Flow rate to the Kombucha-PBR was adjusted to maintain 1.2 L in the reactor. Different conditions were tested: Experiment 1. Full-strength EPB Ersatz; HRT: 24 h; operation time: 64 d; no biosolids removal. Experiment 2. three phases: phase 1: 21 d; COD 0 mg/L; NH3 200 mg N/L; phase 2: 18 d, COD 220 mg/L, NH3 170 mg N/L; phase 3: 28 d, COD 480 mg/L, NH3 180 mg N/L; |

| Reactor |

System configuration

and operational conditions |

Application and removal efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Pack-Bed reactor (PBR) |

System configuration Wastewater: modified EPB Ersatz (DOC 239–272 mg·L-1, 4:1 COD to N ratio, COD 800 mg·L-1, TN 700 mg·L-1). Packed-bed (Up-flow) Reactor: acrylic cylinder; dimensions: ID = X cm, L = Y cm; TV = V m3. Packing material: bacterial cellulose Z m2. Gas supplied: air (1.5 L·min-1); System operation Flow rate to the Kombucha-PBR was adjusted to maintain 1.2 L in the reactor. Different conditions were tested: Experiment 1. Full-strength EPB Ersatz; HRT: 24 h; operation time: 64 d; no biosolids removal. Experiment 2. three phases: phase 1: 14 d; COD 0 mg/L; NH3 200 mg N/L; phase 2: 18 d, COD 220 mg/L, NH3 170 mg/L; phase 3: 20 d, COD 480 mg/L, NH3 180 mg N/L; Phase 4: 12 d, COD 780 mg/L, NH3 700 mg/L; |

COD & N removal: 80%

Experiment 1: COD removal efficiency 81%; NH3 removal efficiency neglectable. Experiment 2:Phase 1: NH3 removal efficiency 80%. Phase 2: COD removal efficiency 80%. Phase 3: 80% removal efficiency COD and TN. Phase 4: COD80% removal efficiency. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).