1. Introduction

Water is a vital resource in human spaceflight, accounting for approximately 65% of a crew member’s daily mass intake [

1]. As human exploration extends farther from Earth to destinations such as the Moon and Mars, the cost and risk associated with water resupply increase significantly. To enable long-term residence in space, the development of reliable and sustainable water recycling systems is essential. NASA has made significant advancements in water treatment technologies that convert reclaimed wastewater into potable water [

2]. One important source of reclaimable water is humidity condensate, which offers a sustainable input stream for water recovery systems supporting long-duration missions [

3,

4]. On the International Space Station (ISS), humidity condensate is derived from moisture in the cabin atmosphere, primarily produced through human respiration, perspiration, and other evaporative processes [

5,

6]. The Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) manages the collection and purification of this condensate to maintain safe environmental conditions for the crew. Humidity levels are regulated by the Temperature and Humidity Control (THC) subsystems, which utilize condensing heat exchangers to cool cabin air and remove excess water vapor [

5,

7]. The resulting liquid is separated from the air stream and transferred to the Water Recovery System (WRS) for further treatment. Effective collection and purification of humidity condensate are essential to water recovery and crew sustainability in microgravity environments [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Future extraterrestrial habitats, such as those envisioned on the Moon or Mars, will rely on partial gravity habitation (PGH) systems. These systems are likely to operate with limited or no water resupply, necessitating self-sufficiency through advanced water recycling [

8]. Wastewater sources in PGH environments will include humidity condensate, urine, hygiene water, and fluid from showers and laundry. Unlike in microgravity, density-driven processes in partial gravity environments behave similarly to those on Earth, impacting fluid dynamics and treatment strategies. In light of the spatial and resource constraints of spacecraft and extraplanetary habitats, proposed treatment technologies must prioritize minimal footprint, and low total system mass [

10].

Biological treatment offers a promising approach to stabilizing humidity condensate. It can minimize downstream biofilm formation, reduce reliance on hazardous chemical pretreatments, and lower pH, to suppress ammonia volatilization and reduce bicarbonate concentrations that reduce anion exchange media capacity. Membrane-aerated biological reactors (MABRs) are particularly well-suited for this application as they use bubbleless aeration (Oxygen diffusion through non-porous membranes) reducing odors and water vapor loss [

11,

12,

13]. MABRs have been extensively studied for habitation wastewater including treatment of urine (U), greywater (GW), HC, and combined wastewater (U+GW+HC) [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Reaction rates (10 – 60 g-C/m

3-d) were low compared to suspended growth systems but MABR have been operated for long periods (~ 5 years) without solids management systems which simplifies their operation and reduces secondary waste streams. Micro-gravity compatible MABRs treating HC were able to remove greater than 80 – 90% of OC and oxidize > 60% of the TAN while maintaining a pH < 7.

Reverse osmosis (RO) has been widely adopted in terrestrial water treatment, especially for desalination and growing interest in potable reuse. As a pressure-driven membrane separation process, RO effectively removes dissolved salts, organic materials, and other impurities, resulting in high-quality, reusable water. The integration of biological and membrane-based technologies—known as hybrid wastewater treatment systems—is an emerging strategy for habitation wastewater management [

14]. These systems combine the benefits of biological stabilization with the high rejection capacity of membrane separation, offering a compact and efficient solution for closed-loop life support in space environments [

14,

18] Previous work has shown that a low-pressure RO system was able to produce near potable water from the fluid of a MABR treating greywater and process up to 3000 L on a single membrane at 90% recovery [

14]. When applied to humidity condensate treatment in space systems, RO significantly enhance water recovery performance.

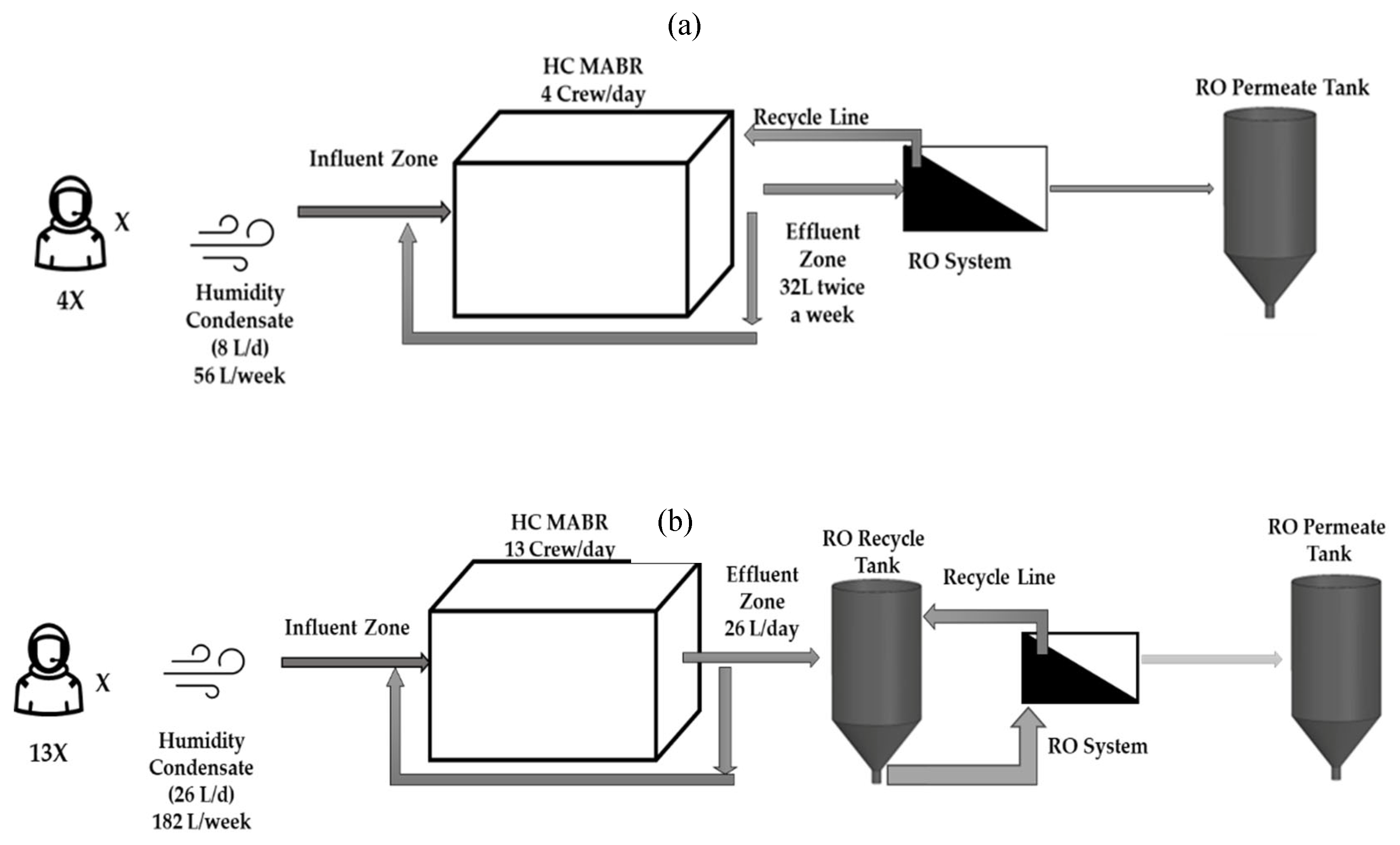

In this study, a full-scale hybrid treatment system for Humidity Condensate was evaluated, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The system integrates a variable volume membrane-aerated biological reactor (MABR) for pretreatment of the humidity condensate (HC) with a brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO) unit. Two configurations were assessed to determine system performance in terms of processing capacity, throughput, consumables, and water quality (

Figure 1). The MABR continuously received simulated habitation HC which was the feed to the RO system. The RO system was operated in two configurations. In Configuration 1 (

Figure 1a), the MABR reactor fluid was processed directly from the MABR with the RO concentrate recycled directly back to the MABR. In this configuration no brine was wasted and rejected species were stored in the MABR and the system recovered 100% of the HC wastewater. In contrast, Configuration 2 (Figure 1b) employed a daily release of MABR fluid to the RO recycle tank, which was processed by the RO in batch mode. The final brine, representing 10% of the total batch volume, was drained for further processing. This study therefore tested both an external RO recycle tank and the direct use of the MABR as the recycle reservoir, enabling the evaluation of trade-offs in system mass, volume, consumables, and operational efficiency. This analysis provides insight into the application and evaluation of hybrid biological–membrane treatment systems for partial gravity habitats, particularly in managing humidity condensate wastewater streams [

14].

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Configuration and Process of the HC MABR and BWRO System

The treatment system is composed of two core components: the humidity condensate membrane aerated biological reactor (HC-MABR) and the brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO)units. This configuration is designed to treat low-strength wastewater - such as humidity condensate efficiently, with minimal maintenance and energy use [

14].

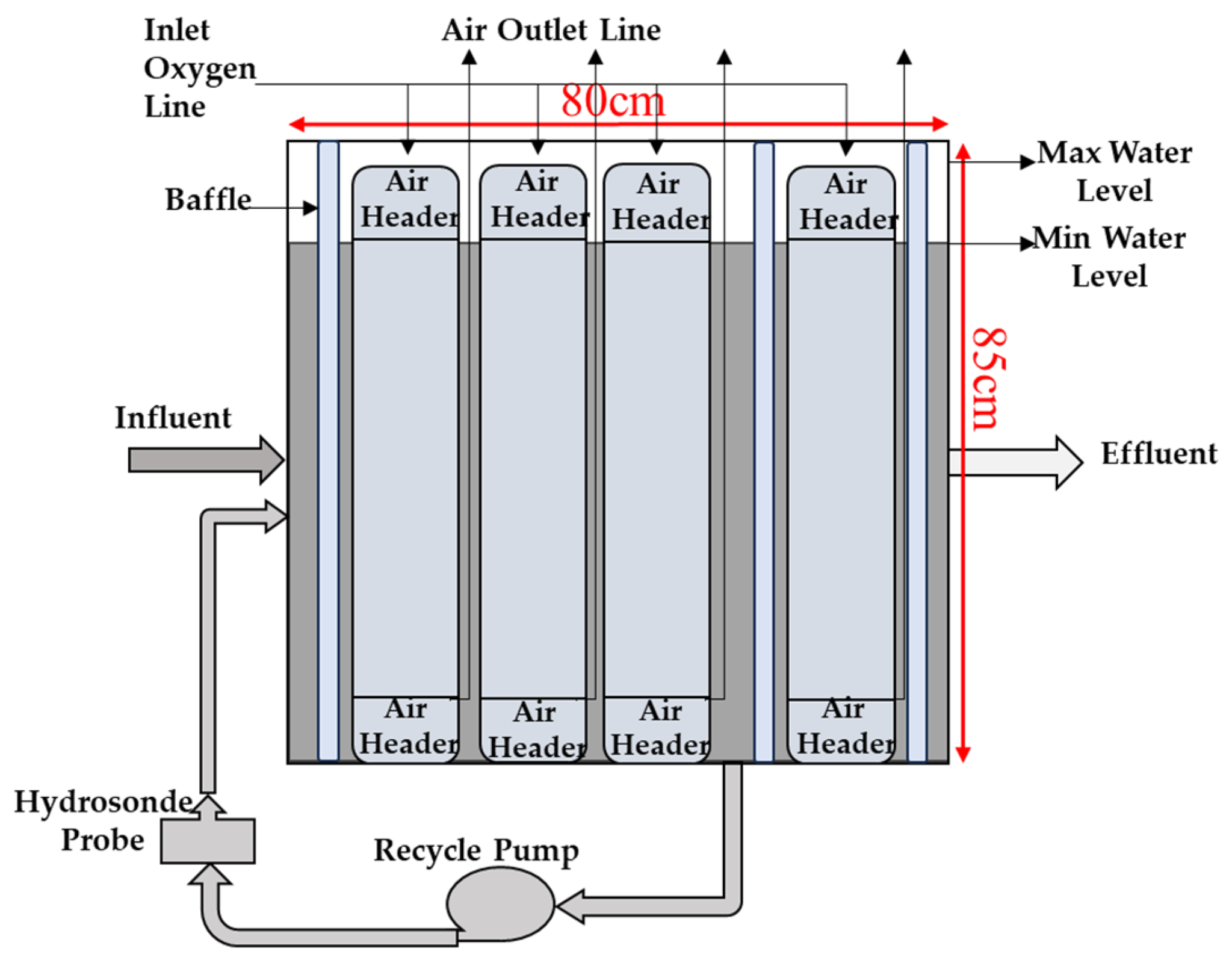

2.1.1. Attributes of the Humidity Condensate Membrane Aerated Biological Reactor

The humidity condensate membrane-aerated biological reactor (HC MABR) was engineered to support a treatment capacity of up to 26 liters (13 crew) per day. With an average nominal hydraulic retention time (HRT) of four days The MABR has been previously described in detail but is summarized here for convenience. The total and minimum wet volumes of the reactor were calculated as 238 liters and 169 liters, respectively. The reactor contained four independent siloxane membrane aeration modules, each equipped with dedicated inlet and outlet air headers. Each module consisted of 374 hollow, non-porous siloxane tubes with an internal diameter of 0.245 cm and an external diameter of 0.55 cm [

14]. Compressed oxygen was delivered to all four modules at a rate of 100 mL/min via Masterflex mass flow controllers (model number 32907-55). The effective membrane-specific surface area of the system was approximately 100 m² per m³ of reactor volume. Internal mixing was maintained by a Laing LHB08100092 recirculation pump operating at a flow rate of 22 L/min. During operation, wastewater was introduced into the reactor continuously as it would be produced in a PGH.

Figure 2.

Humidity Condensate MABR schematic (adapted from Hooshyari et al [

14]).

Figure 2.

Humidity Condensate MABR schematic (adapted from Hooshyari et al [

14]).

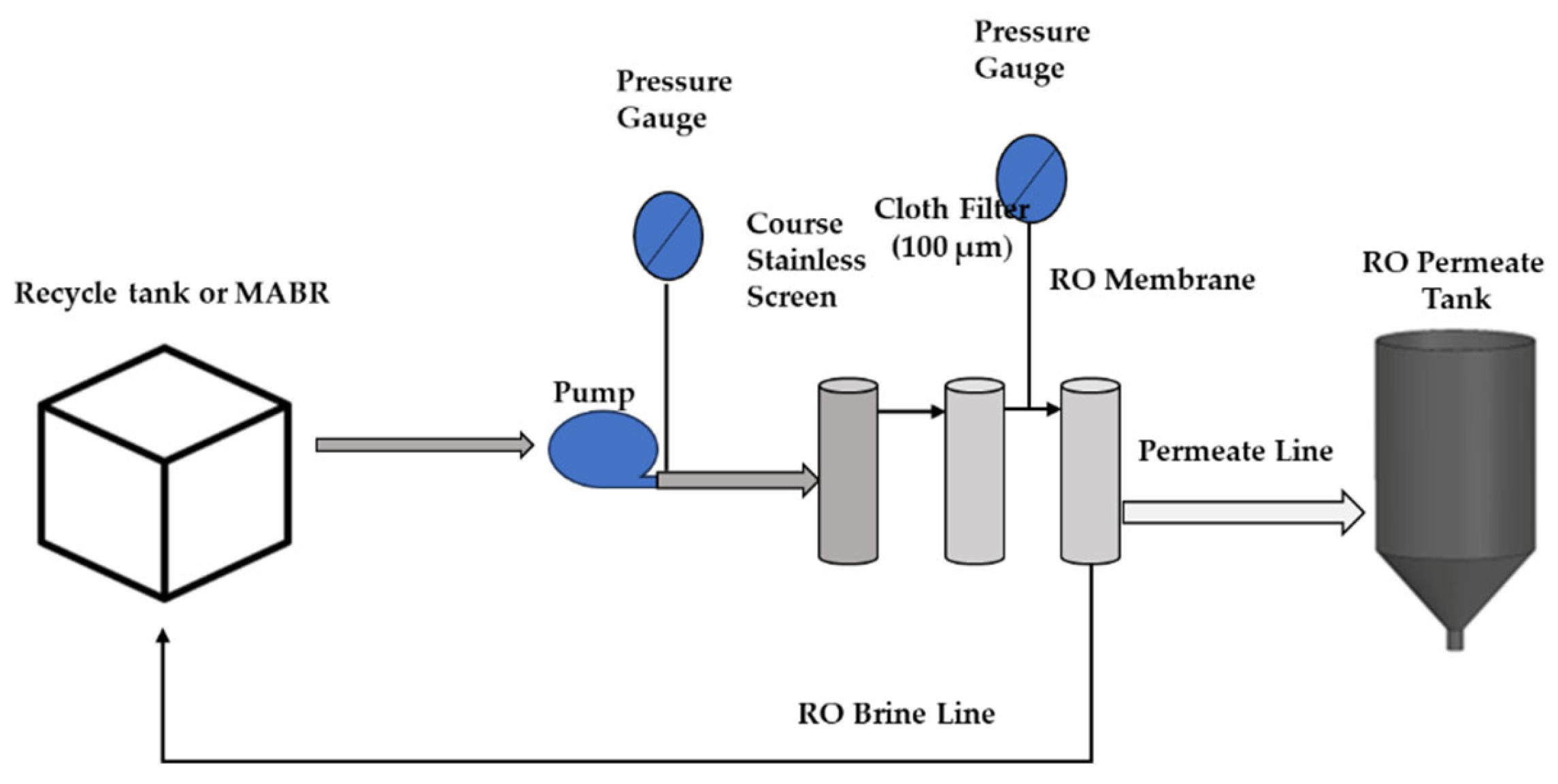

2.1.2. Attributes of Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis (BWRO) Unit

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO) unit consisted of a 115-liter conical recycle tank, a ClearPath MAP V2 recycle pump, a coarse stainless-steel screen, a cloth prefilter module (polypropylene fiber, 100 µm), an BWRO treatment unit, and a 115-liter conical permeate collection tank. The system was designed to facilitate batch-mode operation at 3.45 bar (50 lb/in²) and enable continuous monitoring of flow and filtration performance. The BWRO unit employed a commercial Genuine DuPont FilmTec Element (BW60-1812-75) membrane module with a membrane area of 0.67 m². These membranes are a classic spiral-wound configuration, consisting of multiple membrane sheets wrapped around central permeate tube with feed spacers between membrane layers and permeate carriers to collect treated water and guide it to the center tube.

2.1.3. Humidity Condensates Stream Composition and Feeding Regime

Humidity condensate was made daily from concentrated stock solutions (

Table 1). The HC composition was based on analysis of ISS samples and adapted from (Muirhead et al., [

4]). The HC has an OC concentration of 90 – 120 mg/L, TN of 19 – 40 mg/L and TDS of 170 – 230 mg/L.

2.2. BWRO Treatment Process Configuration Type

2.2.1. Configuration 1

In configuration 1 (

Figure 1a), the HC MABR was loaded with 8L of HC per day corresponding to the output of a crew of 4. The processing of HC MABR fluid by the brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO) system was performed at a constant inlet pressure of 3.45 bar (50 lb/in²). During operation, the flow rate through the RO membrane module varied based on membrane time of total operation, between 4.2 and 2.5 liters per hour, which corresponds to a flux range of ~6.0 to ~3.8 L hr

-1 m

-². A separate 115-liter conical tank was used to collect the RO permeate, while the brine stream was routed back into the HC MABR, allowing for complete recycle of the concentrate. The system was operated until 100% of the influent volume was recovered in the permeate tank, with no brine removed from the system. Each processing cycle was scheduled every four days, corresponding to a batch volume of approximately 32 liters. BWRO module pressure, permeate flow rate, and internal recycle rate were monitored throughout each batch run. Operational data were recorded manually at regular intervals to track system performance and ensure consistency in treatment conditions.

2.2.2. Configuration 2

In configuration 2 (

Figure 1b), the HC MABR was loaded with 26 L of HC per day corresponding to the output of a crew of 13. MABR fluid was transferred to the BWRO recycle tank as a batch and processed at a constant membrane inlet pressure of 3.45 bar (50 Ib/in²). The flow rate through the RO membrane varied with membrane total operation time, between 6.0 and 1.8 liters per hour, which corresponds to a flux range of ~8.9 to ~2.7 L hr

-1 m

-². RO permeate was collected in a separate conical storage tank, while the brine stream was recycled back to the feed tank. Each operational cycle continued until 90% of the influent volume was recovered as permeate. The remaining 10% designated as brine was processed and subsequently discharged to a drainage system. The system processed four to five days’ worth of MABR fluid per batch, depending on availability and system load. Key operational parameters, including RO module pressure, permeate production rate, and internal recycle rate, were monitored throughout each cycle. Manual data logging was conducted at regular intervals to ensure performance tracking and process control.

2.3. Testing and Evaluation of Treatment System

Water samples for water quality analyses were collected from the humidity condensate (HC) stream and the final RO permeate three times per week throughout the experiment. MABR fluid samples were taken immediately after being transferred to the RO recycle tank to capture representative conditions. During treatment tests, pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) levels within the reactor were measured using a portable Hach H11d multiparameter pH/ORP meter.

All collected samples were filtered through 0.45 µm membrane filters and stored at 4 °C until subsequent analysis. Anion concentrations—including chloride (Cl⁻), nitrite (NO₂⁻), nitrate (NO₃⁻), phosphate (PO₄³⁻), and sulfate (SO₄²⁻)— were determined using a Dionex ion chromatography (IC) sodium carbonate/bicarbonate eluent with a 4mm AS20 column and 4mm suppressor. Total nitrogen (TN) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) were quantified with a TOC-L CSH Shimadzu total organic carbon (TOC) analyzer. Before DOC analysis, samples were acidified and stored for a minimum of 24 hours to ensure the removal of inorganic carbon. In addition, biological oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) tests were conducted weekly on the influent and MABR fluid of the MABR as well as on the RO permeate to evaluate water quality and treatment efficiency.

3. Results

3.1. Organic, Nutrient, and Inorganic Salt Removal in the HC MABR-BWRO System

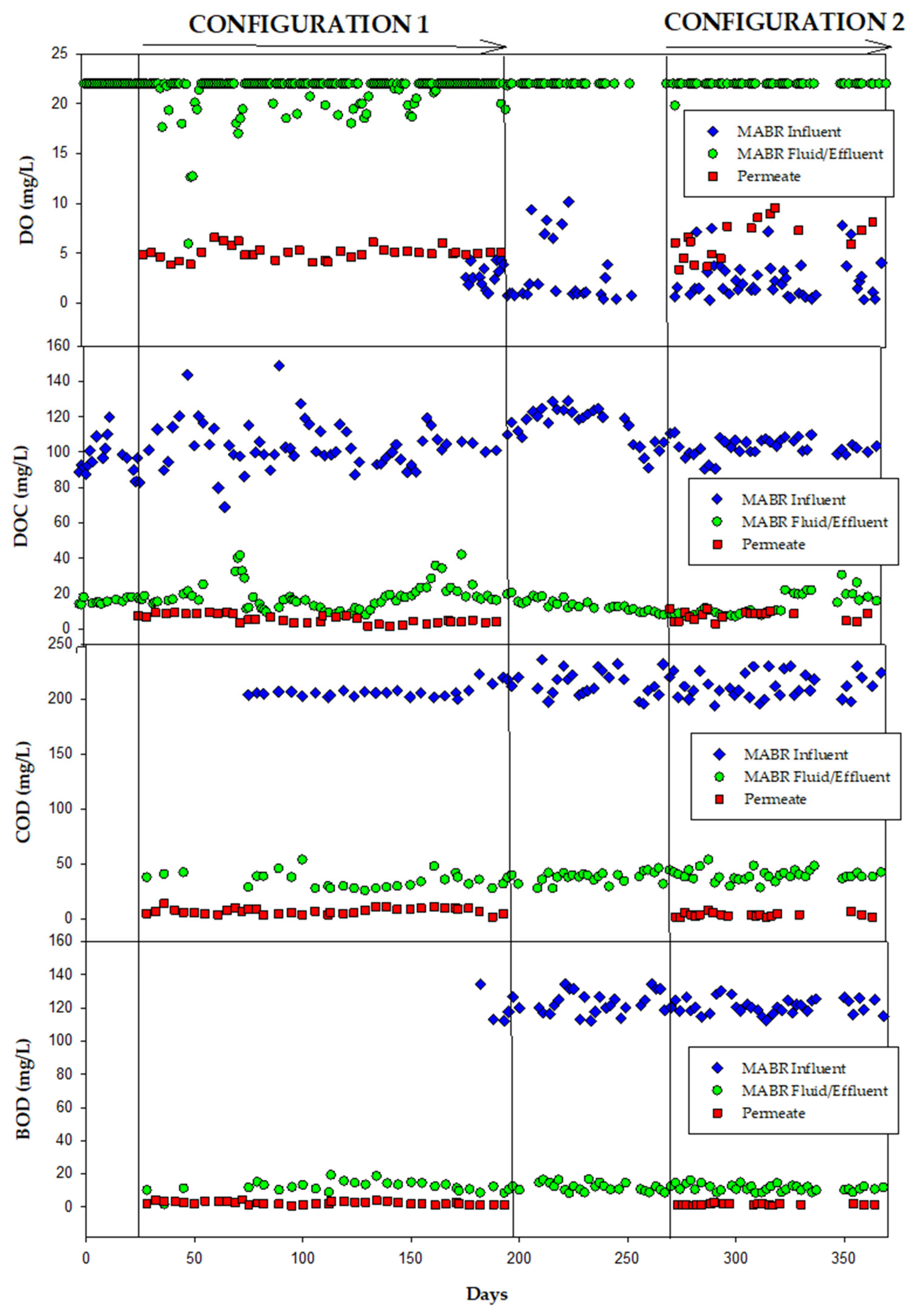

3.1.1. Configuration 1

The MABR reduced the influent DOC (80 – 140 mg/L), COD (202 – 230 mg/L), and BOD (105 – 130 mg/L) by greater than 80%, 85%, and 80%, respectively (

Figure 4). The steady state concentrations in the reactor were generally less than 20 mg/L, 40 mg/L, and 15mg/L, respectively. This strongly supports that most degradable organic matter was oxidized. In addition, the elevated oxygen concentrations, near saturation (~20 – 22 mg/L), suggest that the system was not operating at capacity and was not oxygen limited. The HC MABR system DOC, COD and BOD did not increase over time, despite that no brine was wasted during the BWRO process. RO Permeate DOC, COD and BOD concentrations were very low <7 mg/L, <10 mg/L and <4 mg/L, respectively and very stable with time. The OC carbon concentrations are near potable limits and indicate a stable solution with minimal biofilm formation potential. These results demonstrate the HC MABR’s capability to support

high efficiency organic removal under

zero liquid discharge conditions, reinforcing its suitability for long-duration or resource-constrained treatment systems.

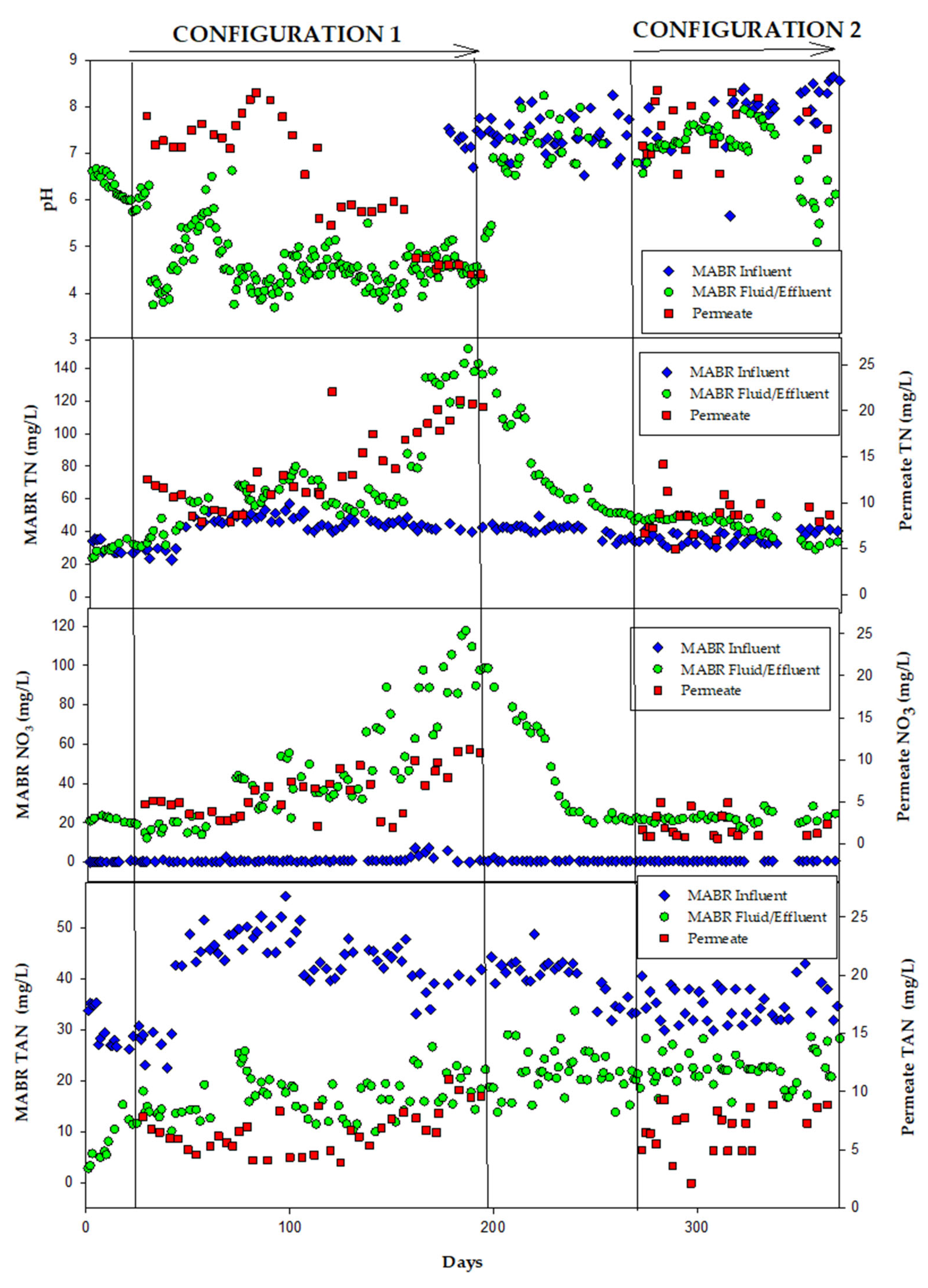

The MABR system achieved consistent

TAN oxidation reducing influent TAN ~50 mg/L to ~ 20 mg/L (

Figure 5). The oxidation of TAN produced NO

3⁻, the concentration of which increased throughout the test reaching ~120 mg/L by the test cessation, due to production in the MABR and rejection by the RO system. The relative production for NO₃⁻ and associated proton production, consumption of bicarbonate due to growth, and differential rejection of NO₃⁻ compared to NH₄⁺ resulted in a strong pH drop (<5 generally) in the MABR. The low pH through most of the test period likely limited TAN oxidation, due to a lack of alkalinity to support growth. This has been observed in other wastewater habitation studies as well in which an oxidation efficiency of 50-70% was generally observed [

15,

16,

19].

In the permeate TAN concentrations ranged from ~ 5-10 mg-N/L generally increase throughout the test period. Similarly, NO₃⁻ concentrations increased from ~5 mg-N/L initially to ~ 10 mg-N/L by the end of the test period. The relative rejection of NO₃⁻ increased from ~75% to >90% but TAN rejection decreased from ~75% to ~50% throughout the test period. The decrease in TAN rejection may be due to NO₃⁻ transport though the membrane which forced increased TAN passage to maintain charge neutrality. The increase in TAN concentrations in the permeate over the test run also caused the pH of the permeate to decrease from ~7 to ~4 throughout the test period, due to NH₄⁺ (dominant form in MABR) disassociation to NH₃ and H⁺. The lower pH of the permeate is beneficial for space habitation systems that use ion exchange to remove trace anions and cations, as it reduces the bicarbonate concentration which can consume exchange capacity.

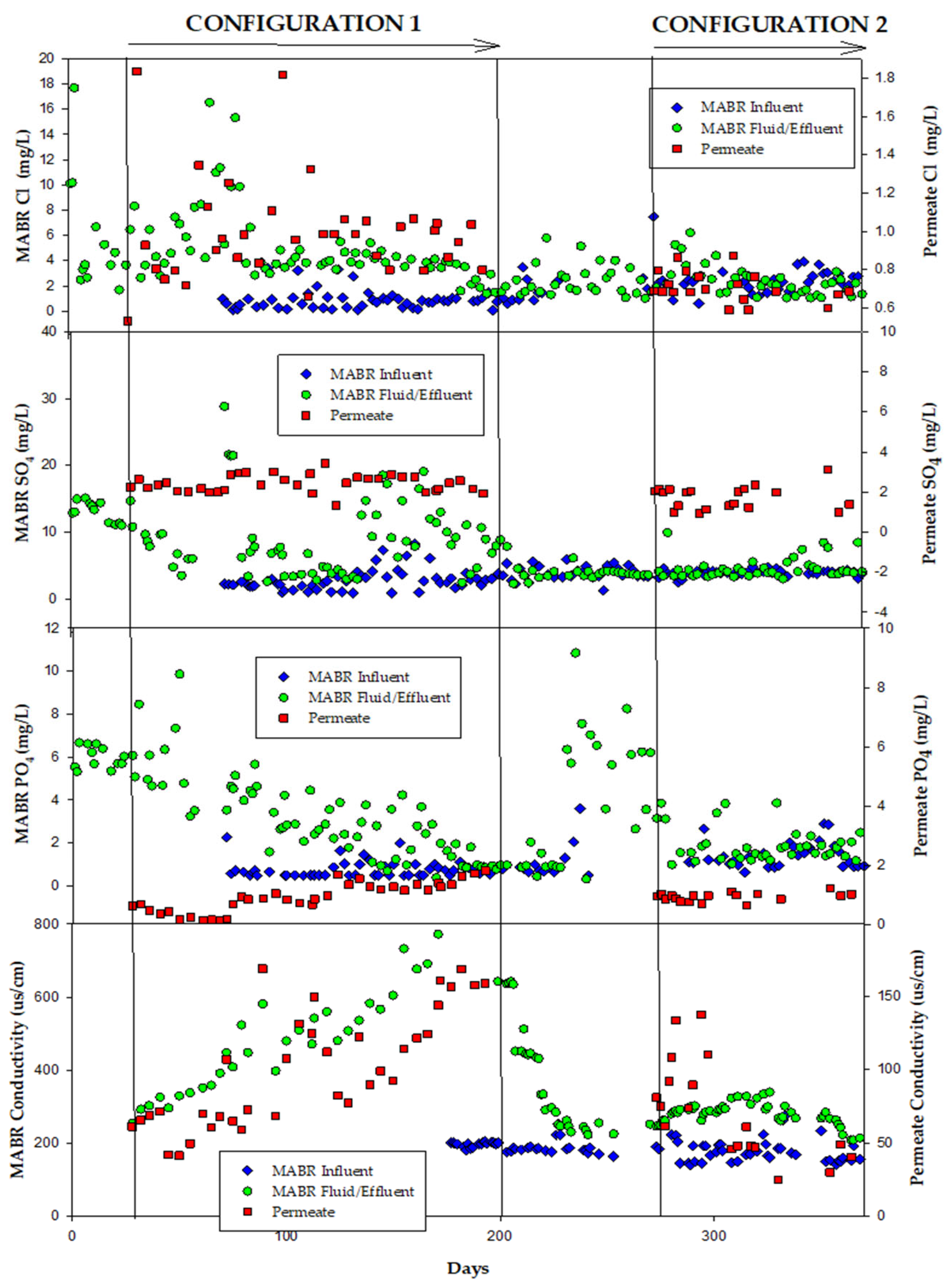

The influent HC has very low concentrations of Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻ and PO₄³⁻ (<2 mg/L). Concentrations of the species in the reactor were higher than influent concentrations due to residuals from past testing and generally decreased throughout the test period. The conductivity of the MABR fluid increased from ~ 200 µs/cm, similar to the conductivity of the influent feed, to > 800 µs/cm after processing ~ 1000 L of HC (

Figure 6), driven by the accumulation of ions rejected by the RO system and retained in the reactor. The permeate conductivity increased throughout the test period form ~ 50 µs/cm to 180 µs/cm at the end of the test. NO₃⁻ and TAN and H⁺ were the dominant measured species in the permeate. Other anions such as SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻ and PO₄³⁻ were generally less than 2 mg/L throughout the test period. On a charge equivalent basis, the permeate NO₃ and NH₄ each constituted 45% of the total permeate conductivity, H⁺ 6%, and all other species combined < 4%.

3.1.2. Configuration 2

In configuration 2, in which there was an external recycle tank, the MABR was loaded at a much higher rate (26 L/day) than in configuration 1 (8 L/day). Even at this increased loading rate DO concentrations in the MABR remained consistently

near saturation (~22 mg/L). DOC, COD and BOD influent concentrations were constant through the configuration test and very similar to influent concentrations throughout configuration 1 testing. MABR fluid DOC, COD, and BOD concentrations were also very similar (2

0 – 40 mg/L, 30 – 50 mg/L, and 15 – 20 mg/L, respectively) to MABR fluid concentrations in configuration 1 testing (

Figure 4). Similar concentrations between configurations, even though the loading was 3.25 times greater in configuration 2 and in configuration 1 no brine was removed, suggest that the reactor was not kinetically limited (e.g. could be smaller and achieve the same performance) and that a portion of the residual DOC is degradable over longer time periods. The permeate water quality, as reflected in

DOC, COD, and BOD concentrations (DOC < 5 mg/L, COD < 5 mg/L, BOD < 3 mg/L) were also very similar to permeate concentrations in Configuration 1 testing. These low concentrations confirm the effectiveness of the combined biological–membrane treatment and the

suitability of the system for long-term water recycling. Particularly with respect to producing a biologically stable permeate.

Total Ammoniacal Nitrogen (TAN) in the

MABR influent varied between 3

0–45 mg-N/L.

MABR fluid TAN concentrations were variable but generally ~ 20 mg/l which was similar to concentrations at the end of configuration 1 but higher than those during the initial period of configuration 1 (

Figure 5). NO₃⁻ concentrations in the MABR fluid remained relatively

stable ~20 mg-N/L and similar to the initial NO₃⁻ concentrations during configuration 1 prior to when rejection on NO3- by the RO caused an increase in concentrations, similar to the period of operation before configuration 1. Permeate NO₃⁻ and TAN concentrations (<5 mg-N/L and 5-10 mg-N/L, respectively) were stable during configuration 2 testing.

MABR fluid and permeate pH were stable between

6.5 and 7.5. The higher pH in the reactor is likely due to the lower overall TAN oxidation efficiency. The higher MABR fluid pH would have caused increased alkalinity and higher ratios of NH3/NH4 compared to Configuration 1 and are likely responsible for the higher permeate pH.

MABR fluid conductivity remained stable and consistently below 250 µS/cm, with limited fluctuation. Permeate conductivity was also stable and <100 µS/cm throughout the test. Chloride (Cl⁻), sulfate (SO₄²⁻), and phosphate (PO₄³⁻) were all very low <3 mg/l and similar to Configuration 1 testing (Figure 6).

3.2. Permeate Flux

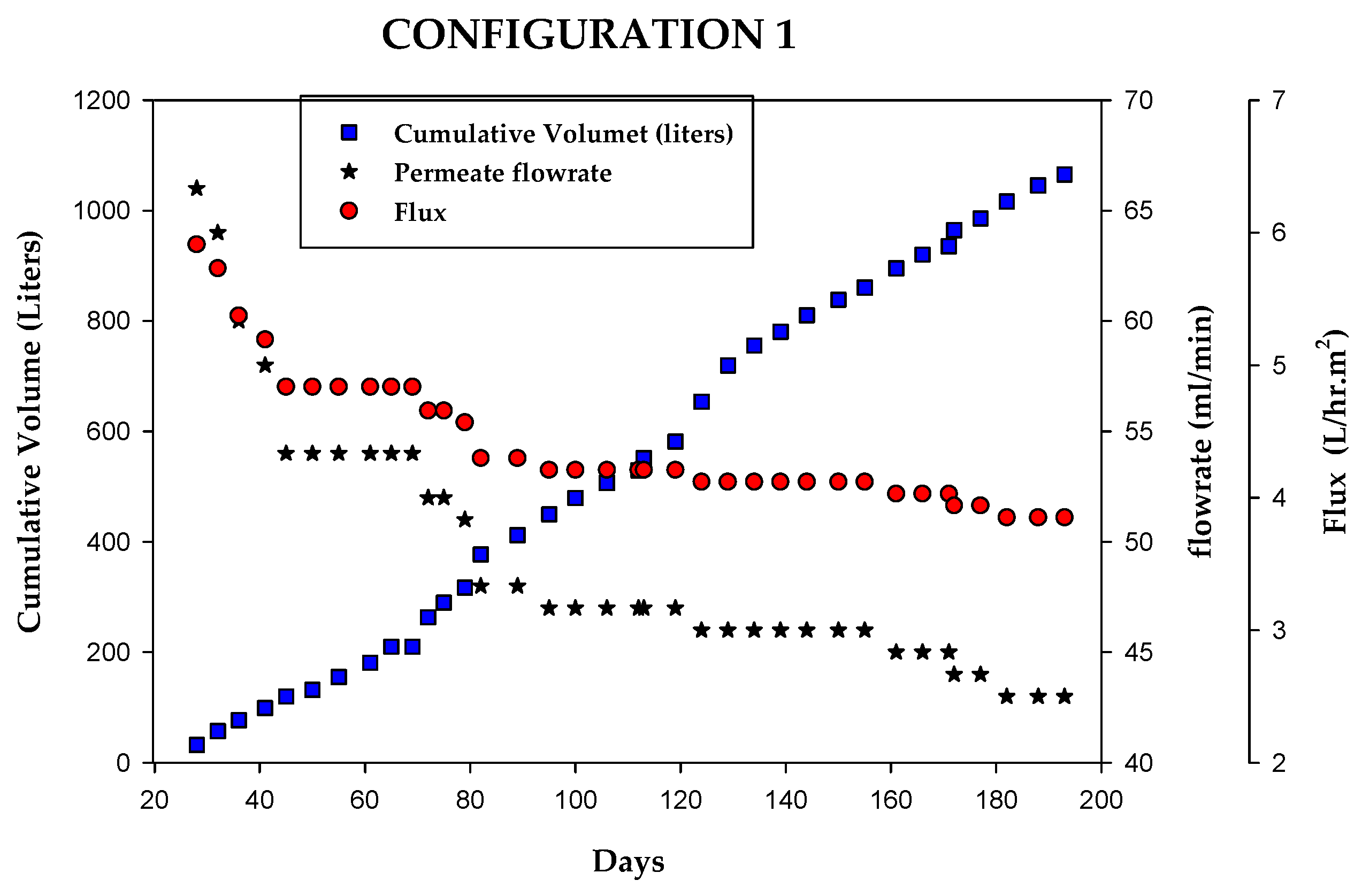

3.2.1. Configuration 1

During Configuration 1 testing the RO system processed ~ 1100 L (550 crew-days) over the 175-day operating period (

Figure 7). As mentioned for this test, the membrane had previously been used to process biologically pretreated space habitation wastewater. As such the membrane flux was ~ 50% of a new membrane flux but the capacity was still much greater than the required flux rate. The permeate flowrate decreased from ~65 mL/min to ~55 ml/min after only ~ 100L and then further decreased to ~45 mL/min over the remaining test period in a non-linear manner. The operating pressure was maintained at 3.45 bar (50 lb/in²) which resulted in a flux range of 6.3 to 3.7 L hr

-1 m

-². It should be noted that when the test was terminated (due to increased conductivity) the RO system could still process the daily influent HC volume (8 L) in less than 3.2 hours. The decline in the permeation rate was likely mostly due to a combination of membrane fouling given the relatively small increase in conductivity which should have only increased osmotic pressure to a small extent.

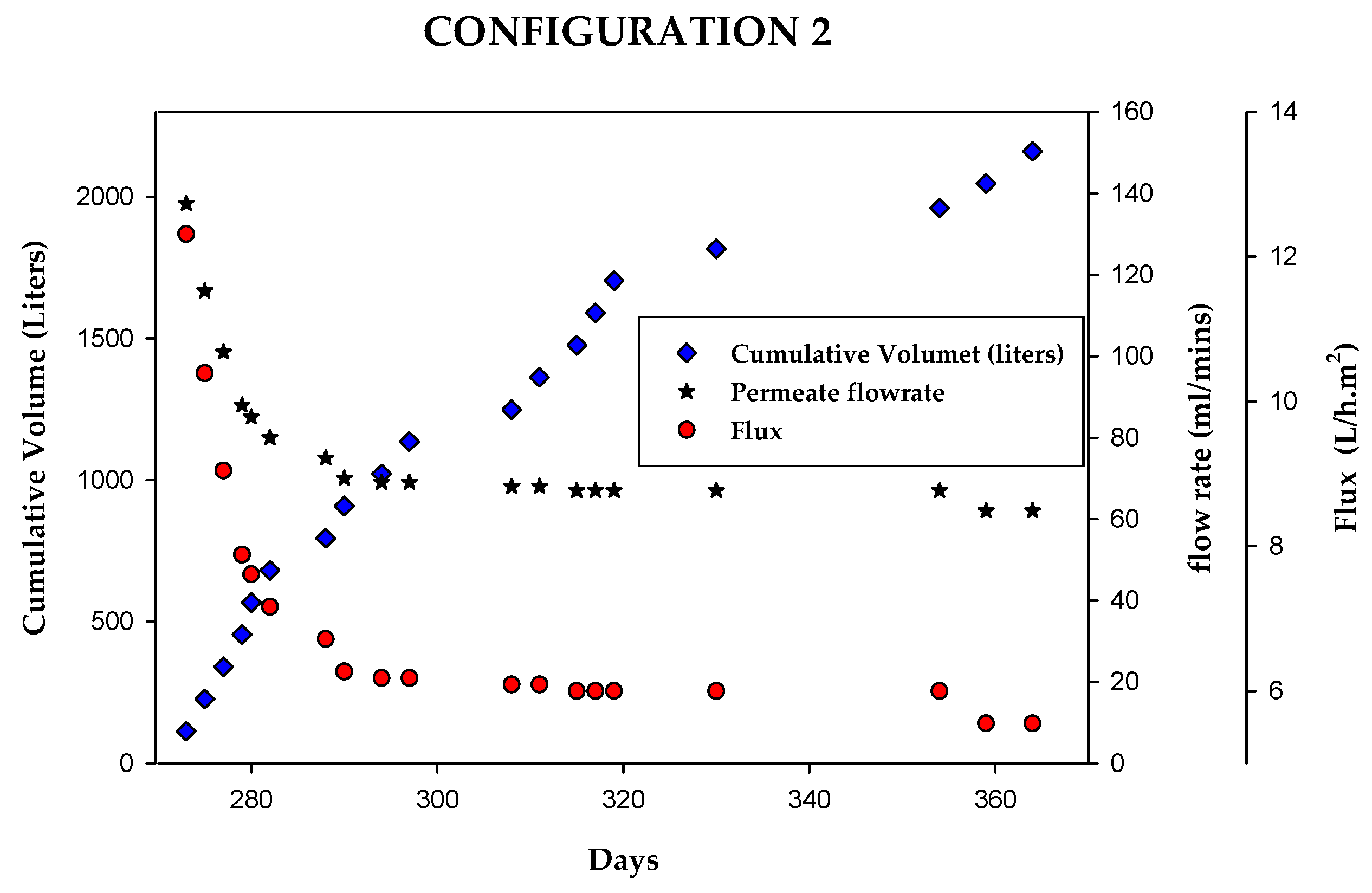

3.2.2. Configuration 2

During Configuration 2 testing the RO system processed ~ 2160 L (1080 crew-days) over the 180-day operating period (

Figure 8). The permeate flowrate decreased from ~140 mL/min to ~69 ml/min after ~1000L of produced water and then only slightly decreased to ~62 mL/min over the remaining operating period (~1000L of treated water). Similar to Configuration 1, the operating pressure was maintained at 3.45 bar (50 lb/in²) which resulted in a flux range of 5.55 to 12.3 L hr

-1 m

-. It should be noted that when the test was terminated the RO system could still process the daily influent HC volume (37.2 L) in less than 10 hours. While it is not advisable to extrapolate to predict the total membrane life, it does appear that in Configuration 2 the total life of the membrane could be substantially longer than the tested 1080 crew-days of processed HC.

4. Discussion

Configuration 1 (MABR as recycle tank with no brine wasting) was able to produce permeate with very low DOC and with reduced conductivity compared to the influent, for ~ 500 crew days. In addition, in this scenario, the permeate pH (4-6) was much lower than the feed water. Assuming future habitation systems will use polishing systems similar to ISS in the future, which are based on ion exchange, this could be a significant advantage. The lower pH would reduce bicarbonate concentration, which is a significant contributor to ion exchange (IX) consumption on ISS. Configuration 1 would not be stable over long periods, due to the accumulation of dissolved species in the reactor. However, it does demonstrate that the configuration could control downstream biofilm formation by near elimination of DOC and reduce system complexity by eliminating an intermediate recycle tank. However, for long term operation (>500 crew/days) to prevent increased conductivity in the permeate compared to the influent and reduce IX consumption modifications to the system or operation would be required. One possibility includes wasting small volumes of MABR fluid daily (~10% of the daily influent loading volume (

e.g., 0.2 L/crew-day)) which could be sent to more robust desalination systems used for urine desalination (e.g. distillation) [

8]. Another possibility would be to operate the system until the permeate conductivity became unacceptable (e.g. equal to influent conductivity) and then process the total volume of the reactor through the urine desalination system [

20]. Alternatively, using an RO system with a higher rejection such as a saltwater membrane could allow for much longer operation time before conductivity in the permeate was unacceptable [

14].

Configuration 2, while requiring an intermediate recycle tank, was able to consistently produce near potable water for over 1000 crew-days without any deterioration in permeate water quality and at a flux rate that was still 8X greater than needed to process a 4-crew daily load at the termination of the experiment. While the system total mass is higher due to the intermediate recycle tank, this is a fixed cost, and the tank size could be relatively small, as low as 8 L assuming daily processing. Given that this system reduces conductivity by ~75% as well essentially eliminated downstream biofouling potential, the mass savings based on extended IX life and reduced maintenance may more than justify the inclusion of the recycle tank.

5. Conclusions

Additional work is required to demonstrate and evaluate Configuration 1 as a long-term operating system to support space habitation systems. For Configuration 2, it is possible to evaluate system size and consumable mass. Given that the MABR was able to process a load of 13 crew/day, for projected missions with a crew of 4, the MABR size would be no larger than ~ 50 L (~ 6-day residence time). Based on the above, if the recycle tank has a volume of 8 L the total storage volume would be < 60 L. For comparison, on ISS the Water Processing Assembly storage tank has a volume of ~50 L. In terms of consumables, even assuming the RO membrane can only process ~2000 L, volume demonstrated in this study, the total consumable mass consisting of O2 (0.00024 kg/kg of processed water) and RO membrane (0.25 kg per 2100 kg of processed water) would be <1 kg per year for a crew of four.

Overall, the results suggest that a hybrid water processing system, which replaces a passive storage tank for HC with an engineered bioreactor which is coupled to a small scale (< 139 kg total system mass) low pressure (<50 lb/in²) RO system, could provide near potable water for extended periods (> 1000 crew-days). The increased system mass would be more than offset by reducing IX bed consumption (~25% of consumption W/O RO) and the system would eliminate downstream biofouling a significant issue observed on ISS. Additional work should be conducted to further explore the optimized configuration and extended RO life as well as demonstrate the total mass savings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A.; validation, S.A., W.A.J. and W.S.W.; formal analysis, S.A.; data curation, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, W.S.W. and W.A.J.; supervisor, W.A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), grant number 80NSSC21K0467.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the assistance of numerous student workers in our research Lab at Texas Tech University and funding from the Advanced Exploration Systems, Life Support Systems Project (Project 80NSSC21K0467).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Duda, K. R.; Newman, D. J.; Zhang, J.; Meirhaeghe, N.; Zhou, H. L. Human Side of Space Exploration and Habitation. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics 2021, 1480–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.; Schneider, W. NASA Advanced Explorations Systems: 2018 Advancements in Life Support Systems. In 2018 AIAA SPACE and Astronautics Forum and Exposition, 2018; p 5151.

- Lee, J. S.; Yelderman, J.; Cleaver, G. B. Water Management Considerations for a Self-Sustaining Moonbase. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14100 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, D. L.; Moller, S. L.; Adam, N.; Callahan, M. R. A Review of Baseline Assumptions and Ersatz Waste Streams for Partial Gravity Habitats and Orbiting Micro-gravity Habitats. In International Conference on Environmental Systems, 2022.

- Zapparrata, W. R. D. Innovative microgravity condenser for future fully closed Environmental Control and Life Support Systems. Politecnico di Torino, 2019.

- Williamson, J.; Wilson, J. P.; Luong, H. Status of ISS Water Management and Recovery. In 53rd International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), 2024.

- Salmaso, M.; Wang, Z.; Duenas-Osorio, L.; Jernigan, M. Sustainable Space Logistics for Artemis Missions and Deep Space Exploration. In AIAA SCITECH 2025 Forum, 2025; p 1479.

- Lutz, K.; Fairhart, A. Withdrawal: Mars Settlement Water Life Cycle: H2O Production, Infrastructure, Treatment, and Storage. In ASCEND 2021, 2021; p 4218. c4211.

- Jones, H. W. Would current international space station (iss) recycling life support systems save mass on a mars transit? In International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), 2017.

- Bullard, T.; Smith, A.; Delgado-Navarro, M.; Uman, A.; Hoque, B.; Bair, R.; Yeh, D.; Long, P.; Pickett, M.; Roberson, L. A prototype early planetary organic processor assembly (OPA) based on dual-stage anaerobic membrane bioreactor (AnMBR) for fecal and food waste treatment and resource recovery. In 50th International Conference on Environmental Systems, 2021.

- Prieto, A. L.; Futselaar, H.; Lens, P. N.; Bair, R.; Yeh, D. H. Development and start up of a gas-lift anaerobic membrane bioreactor (Gl-AnMBR) for conversion of sewage to energy, water and nutrients. Journal of membrane science 2013, 441, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.-W.; Zhang, T.; Tang, C.-Y. Y.; Wu, W.-M.; Wong, C.-Y.; Lee, Y. H.; Yeh, D. H.; Criddle, C. S. Membrane fouling in an anaerobic membrane bioreactor: differences in relative abundance of bacterial species in the membrane foulant layer and in suspension. Journal of Membrane Science 2010, 364, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, I. L.; Yeh, D. H. Membrane applications for microalgae cultivation and harvesting: a review. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2014, 13, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyari, G.; Bose, A.; Jackson, W. A. Integration of Full-Size Graywater Membrane-Aerated Biological Reactor with Reverse Osmosis System for Space-Based Wastewater Treatment. Membranes 2024, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourbavarsad, M. S.; Jalalieh, B. J.; Harkins, C.; Sevanthi, R.; Jackson, W. A. Nitrogen oxidation and carbon removal from high strength nitrogen habitation wastewater with nitrification in membrane aerated biological reactors. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Ru, Q.; Wang, Y.-f.; Ma, H.; Zhu, E. Development and application of membrane aerated biofilm reactor (MABR)—A review. Water 2023, 15, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. E.; Pensinger, S.; Adam, N.; Pickering, K. D.; Barta, D.; Shull, S. A.; Vega, L. M.; Lange, K.; Christenson, D.; Jackson, W. A. Results of the alternative water processor test, a novel technology for exploration wastewater remediation. In International Conference on Environmental Systems, 2016.

- Shah, M. P.; Rodriguez-Couto, S. Membrane-based Hybrid Processes for Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier, 2021.

- Hou, J.; Zhu, Y.; Meng, F.; Ni, B.-J.; Chen, X. Impact of comammox process on membrane-aerated biofilm reactor for autotrophic nitrogen removal. Water Research X 2025, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyari, G.; Jackson, W. A. Partial Gravity Habitation Water Recovery Using Hybrid Life Support Systems: Membrane Aerated Biological Reactor Integrated with a Distillation System for Urine Recycling. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 117081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).