1. Introduction

Thermal infrared (IR) sensors are indispensable for a wide range of applications, including night vision, thermal imaging, environmental monitoring, gas sensing, and industrial process control [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The demand for compact, high-performance, and cost-effective uncooled IR detectors has spurred significant advancements in Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) fabricated on CMOS-compatible Silicon-On-Insulator (SOI) platforms. These CMOS-SOI-MEMS platforms offer exceptional thermal isolation, reduced parasitic effects, and seamless integration with on-chip electronics, enabling scalable and low-power sensing solutions [

5,

6,

7]. By leveraging standard CMOS fabrication processes, these platforms pave the way for affordable, high-volume production of IR sensors suitable for both consumer and industrial applications.

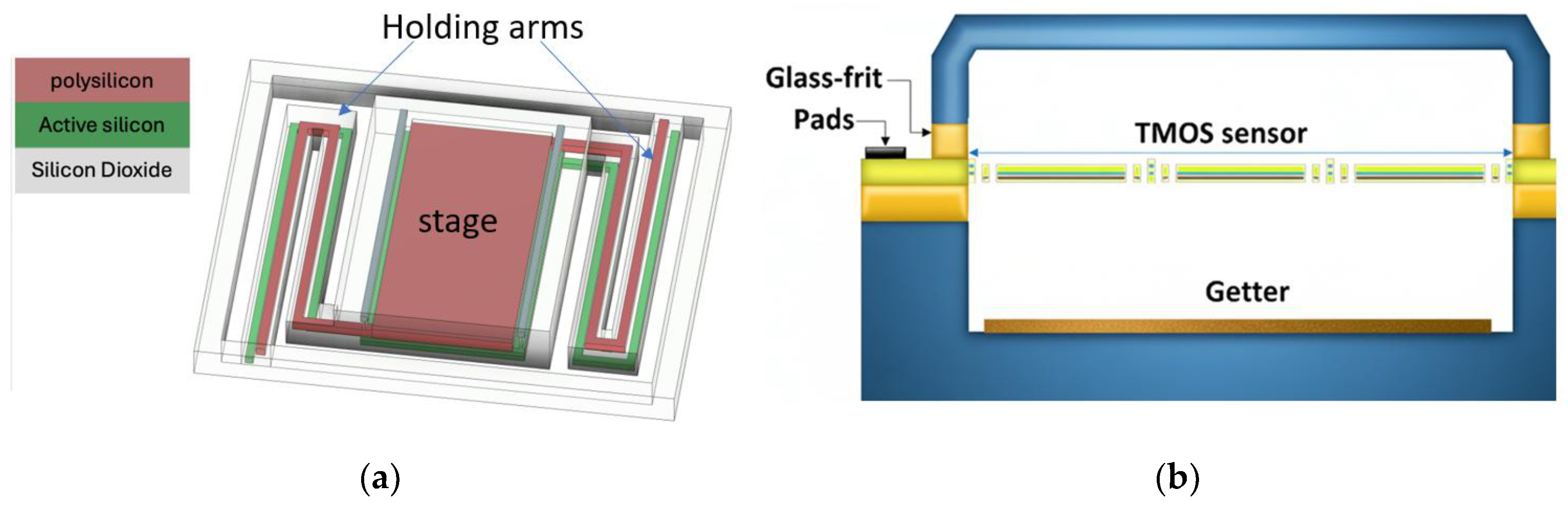

The Thermal CMOS-SOI-MEMS (TMOS) sensor represents a breakthrough in uncooled IR detection, utilizing a suspended MOSFET as the sensing element to transduce IR-induced temperature changes into highly sensitive electrical signals [

8,

9,

10,

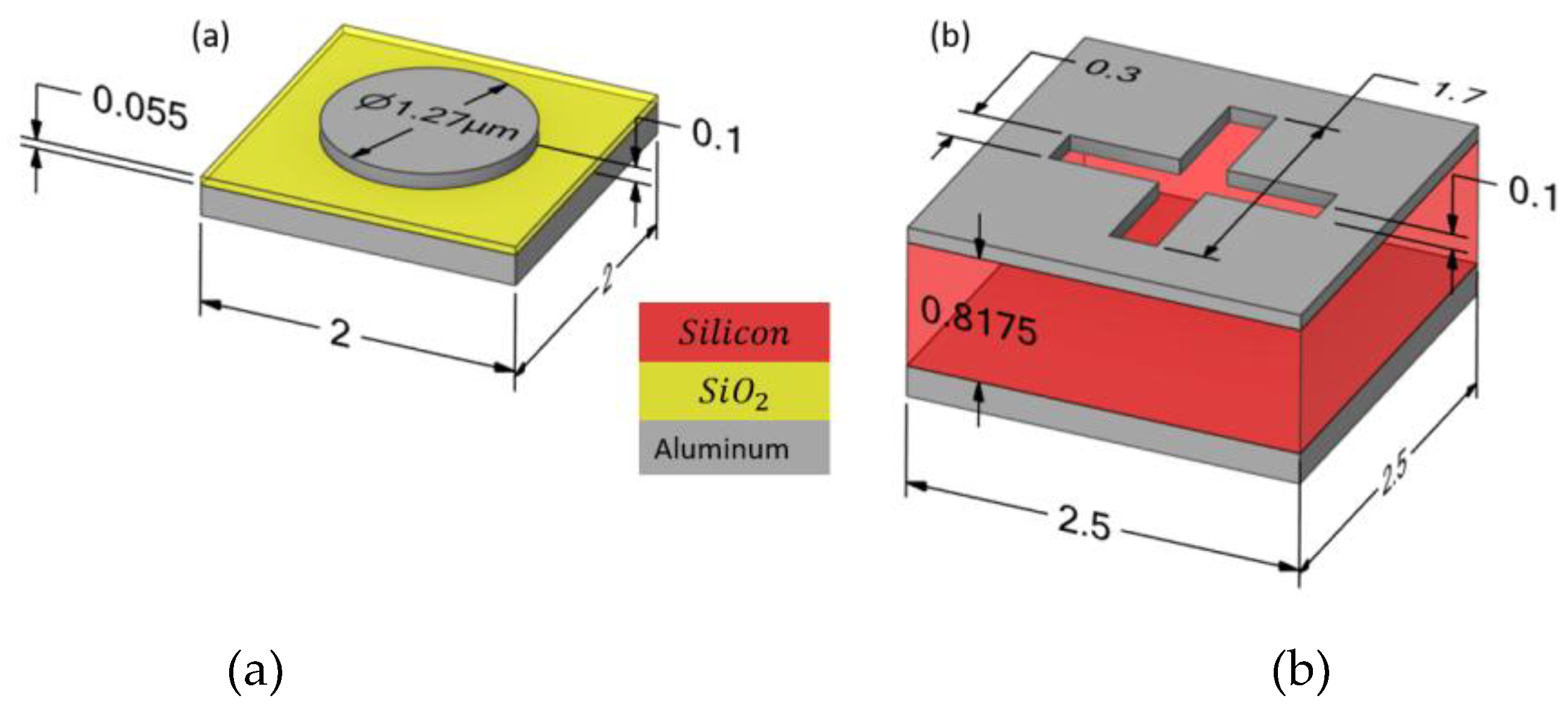

11]. The TMOS architecture achieves superior responsivity by maximizing the temperature rise (ΔT) on a thermally isolated micro-platform, supported by thin holding arms that minimize conductive heat losses. Key to its performance is efficient absorption of incident IR radiation across the 2–14 µm wavelength range, which is critical for applications such as CO₂ gas sensing (4.26 µm) and thermal imaging (8–14 µm). To address this, advanced nanophotonic components, such as Metasurface absorbers based on metal–insulator–metal (MIM) structures, have emerged as a powerful solution [

12,

13,

14,

15]. These Metasurfaces achieve near-unity absorption at targeted wavelengths while remaining fully compatible with CMOS fabrication, offering spectral selectivity for application-specific sensing.

In our previous work [

16], we investigated how incorporating MIM absorbers affects the optical and thermal performance of CMOS-SOI-MEMS thermal IR sensors, and we detailed the simulation methodology as well as the influence of MIM geometry on the absorption spectrum.

However, integrating Metasurface absorbers into CMOS-SOI-MEMS sensors introduces complex trade-offs across optical, thermal, and mechanical domains. Enhanced absorption increases thermal capacitance, potentially slowing the sensor’s temporal response, while added mass may alter the mechanical stability of the suspended microstructure. Existing studies often focus on isolated aspects, such as electromagnetic design of absorbers or simplified thermal modeling, failing to capture the coupled interactions that govern overall sensor performance [

17,

18]. This lack of a holistic multiphysics framework limits the ability to optimize responsivity, speed, and structural integrity simultaneously, hindering the translation of advanced optical concepts into manufacturable devices.

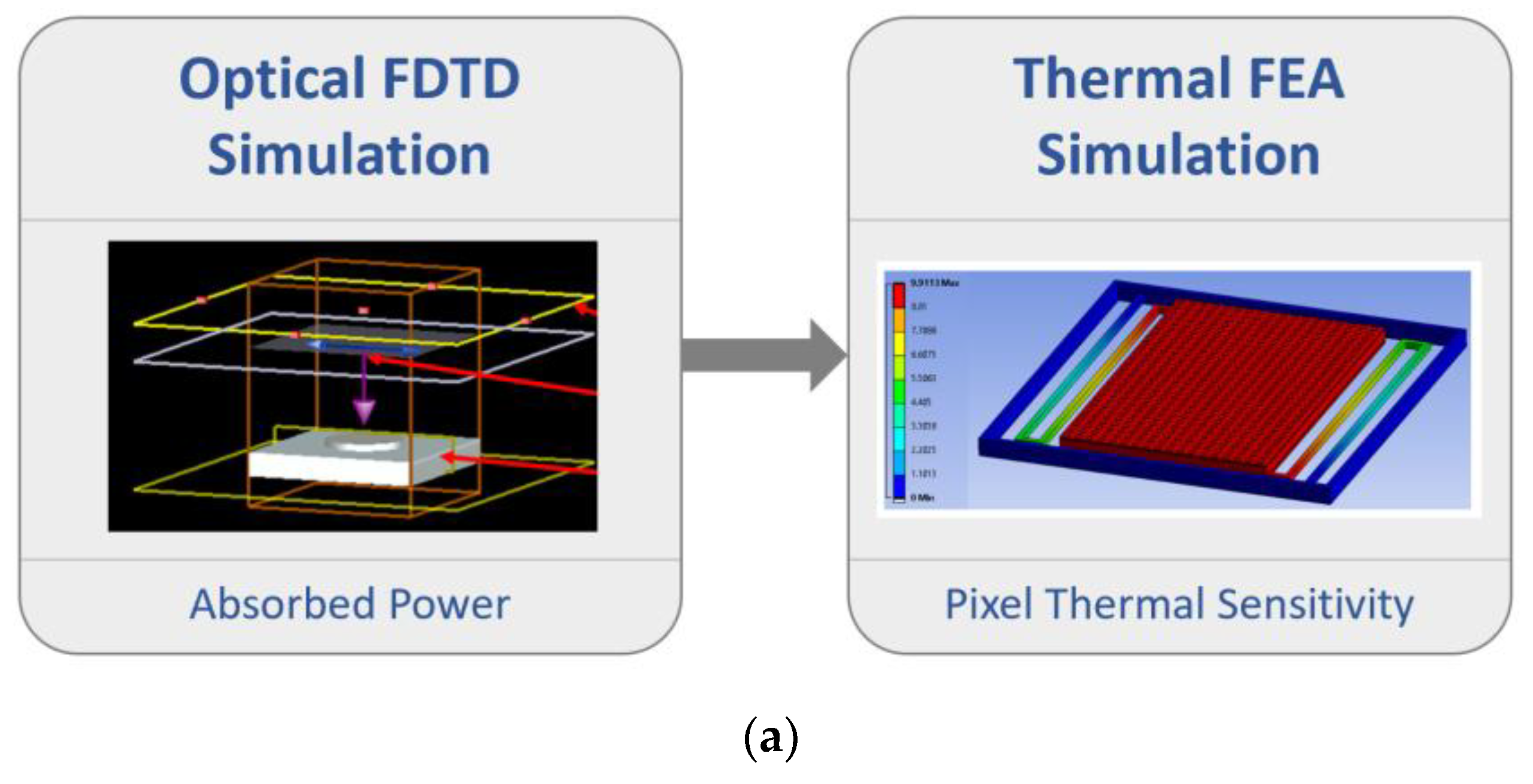

This work addresses this gap by developing a comprehensive multiphysics modeling framework for a TMOS sensor enhanced with Metasurface absorbers. The optical response was modeled using Lumerical FDTD Solutions [

19], where finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations quantified the absorption efficiency and incident radiation distribution, serving as input heat sources for the subsequent thermal finite element analysis (FEA). The thermal and mechanical simulations were conducted using ANSYS Mechanical [

20], with the thermal response validated against an analytical lumped-element RC circuit model to evaluate the sensor’s temperature rise and dynamic behavior, revealing the influence of Metasurface mass on the thermal time constant. Furthermore, mechanical modal and harmonic response analyses assessed the impact of Metasurface integration on natural frequencies and vibration modes, ensuring structural robustness under environmental excitations. As illustrated in

Figure 1, this integrated optical–thermal–mechanical modeling approach provides a predictive design framework that enables systematic exploration of trade-offs toward high-responsivity, fast, and mechanically stable CMOS-compatible IR sensors for advanced applications.

5. Mechanical Analysis

The dynamic mechanical integrity of MEMS is a fundamental determinant of sensor performance, stability, and reliability [

37]. Specifically, the natural frequencies and mode shapes dictate the susceptibility response to external vibrations, which can cause excessive displacement, structural fatigue, or noise-inducing signal distortion. This analysis verifies that the operational bandwidth is safely decoupled from the device’s mechanical resonances.

5.1. Modal and Harmonic Analysis

The dynamic behavior of the suspended micro-platform is often conceptually modeled as a mass-spring system to provide intuitive insight, with the equivalent system illustrated in

Figure 13. For the undamped, single-degree-of-freedom approximation, the governing equation is [

36,

38]:

With a harmonic solution

yielding the natural frequency:

For the complex, multi-material 3D MEMS microstructure a FEM eigenvalue problem is necessary to capture all vibration modes:

where

and

are the global stiffness and mass matrices,

are the natural angular frequencies, and

are the corresponding mode shapes. Each mode represents a distinct three-dimensional deformation of the suspended platform.

To assemble the stiffness

and mass

matrices, the FEM solver requires the

material properties of each structural component: density

, Young’s modulus

, and Poisson’s ratio

. These parameters define the inertial and elastic response of the microstructure. The mechanical properties are depicted in

Table 2.

The FEA model was constructed with a dense mesh for discretization, and fixed support boundary conditions were applied at the anchor points (

Figure 14), consistent with the methodology used for similar high-performance MEMS devices. This simulates the physical constraint where the suspending arms connect to the rigid substrate frame.

The harmonic response analysis quantifies the steady-state displacement when the MEMS device is subjected to a sinusoidal external force

, the general equation of motion for a single-degree-of-freedom system is:

With the steady-state displacement amplitude:

where

accounts for damping due to air, anchors, and internal dissipation. This frequency response function highlights resonance peaks near the natural frequencies. In practice, the MEMS sensor has many degrees of freedom, and its full dynamics are captured by the finite element formulation:

where

contains all nodal displacements. This multi-DOF analysis provides the accurate three-dimensional vibration characteristics, while the lumped single-DOF model offers intuitive insight into resonance behavior.

5.2. Mechanical Simulation Results and Physical Interpretation

The vibrational characteristics were investigated across three critical configurations: the baseline structure (Without MIM), and two configurations integrating the MIM absorber layer (With MIM 1 and With MIM 2). The addition of the absorber introduces mass loading that directly modifies the effective stiffness-mass balance, .

Table 3 summarizes the first six natural frequencies. A clear downward shift in the lower-order frequencies is observed with the inclusion and thickening of the MIM absorber layer.

Figure 15 illustrates the corresponding mode shapes, revealing a critical distinction in the dynamic response:

Low-Order Modes ( to ): Stage-Dominated Motion. These modes exhibit out-of-plane translation, torsional rotation, and combined deformation of the suspended platform itself (Figures 15a-d). The substantial frequency reduction (e.g., dropping from 31.03 kHz to 24.88 kHz with MIM 2) is a direct consequence of the MIM’s mass being concentrated on the suspended stage.

High-Order Modes (

and

): Arm-Dominated Motion. These modes, occurring at significantly higher frequencies (), primarily involve the bending and twisting of the support arms (

Figure 15e,f). Crucially, their frequencies are negligibly affected by the MIM layers. This confirms that the MIM integration selectively affects the stage’s inertial properties while preserving the high stiffness and mechanical integrity of the support structure. The high arm frequencies (the fundamental frequency) are essential for ensuring thermal isolation compliance without introducing low-frequency structural vulnerabilities.

The harmonic response analysis was then performed to evaluate the displacement amplitude of the suspended structure under sinusoidal excitation.

Figure 16 shows the frequency response for the three configurations. The resonance peaks correspond closely to the modal frequencies listed in

Table 2, confirming the consistency of the two approaches.

The simulation results confirm that the sensor’s operational bandwidth lies well below its fundamental resonance frequency, ensuring that normal operation remains unaffected by mechanical resonance effects. This verifies that the suspended stage maintains dynamic stability under typical excitation conditions.

Critically, the lowest natural frequency of the sensor with the MIM absorber is approximately 28 kHz, which is substantially higher than the frequency range of common environmental disturbances encountered in both indoor and outdoor settings (typically below 1 kHz). This indicates strong mechanical robustness, with minimal susceptibility to destructive vibrations or excessive noise coupling during operation.

Furthermore, while the metamaterial MIM layers slightly reduce the resonance frequencies due to their added mass, they do not significantly compromise the overall mechanical stability of the device. The modest frequency shift demonstrates that the MIM layers can be integrated without adversely affecting the structural integrity of the suspended platform. Thus, the metamaterial absorber enhances optical absorption performance while preserving the sensor’s mechanical characteristics.

By maintaining sufficiently high natural frequencies, the design ensures that environmental vibrations and mechanical impacts do not interfere with thermal signal detection. This provides confidence that the MEMS IR sensor can operate reliably in real-world deployment scenarios without mechanical resonance degrading sensitivity or stability.

6. Discussion

This study develops a comprehensive multiphysics modeling framework that integrates optical, thermal, and mechanical analyses to optimize CMOS-SOI-MEMS TMOS sensors with Metasurface absorbers. The following subsections synthesize the results, elucidate trade-offs, and highlight the framework’s utility for rapid design optimization, particularly through the efficient thermal analytical model.

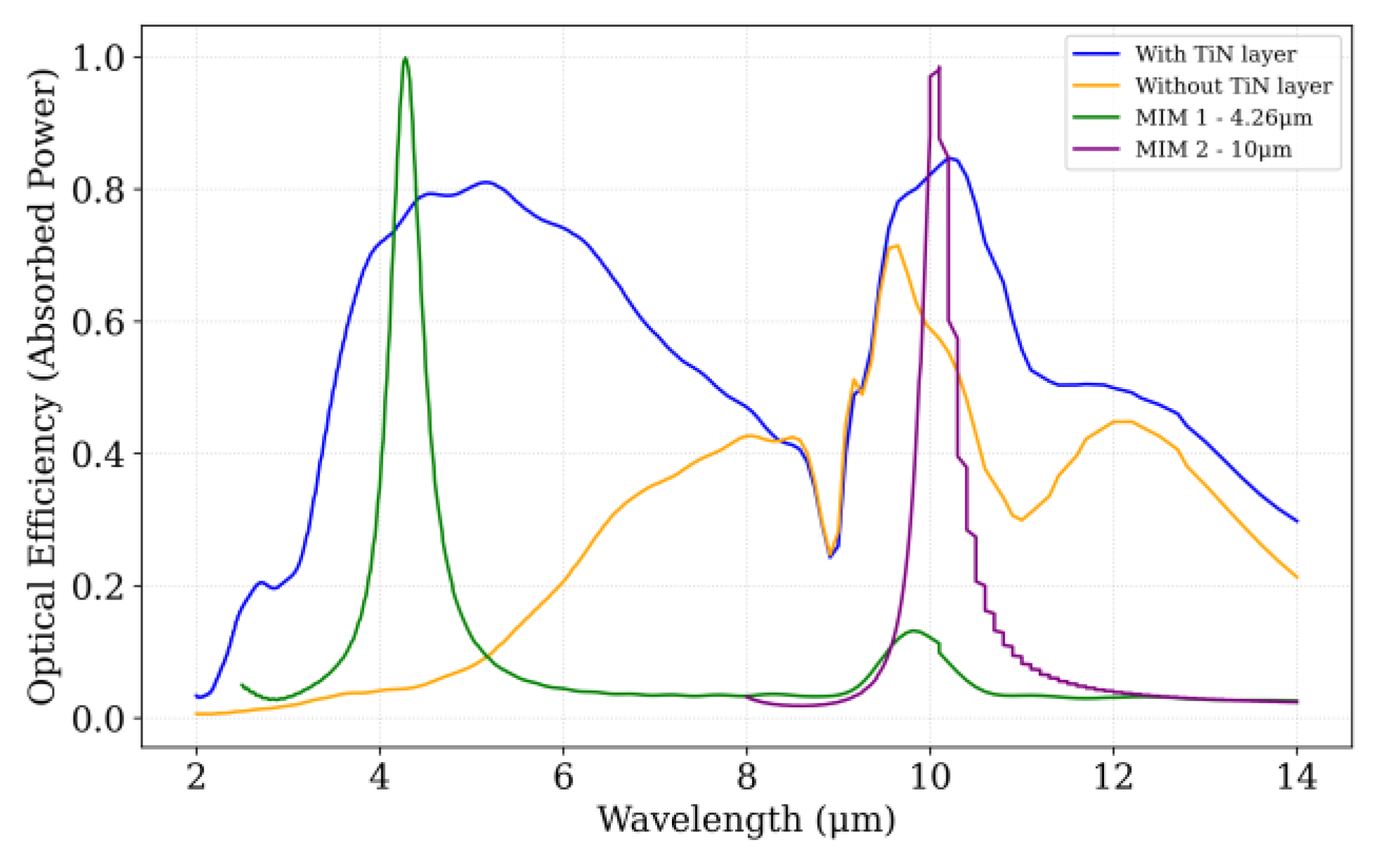

FDTD simulations demonstrate that Metasurface absorbers achieve near-unity absorption at targeted wavelengths (e.g., 0.99 at 4.26 µm for MIM 1, compared to 0.7564 with TiN layer and 0.032 without) (

Section 3.3.2). The TiN layer enhances broadband absorption across 2–14 µm, while MIM configurations enable spectral selectivity for applications like CO₂ sensing (4.26 µm) and thermal imaging (10 µm). The optical modeling framework’s versatility, applicable to any absorber architecture-narrowband, broadband, multilayer, or varied geometries-ensures broad utility for tailored IR sensor designs.

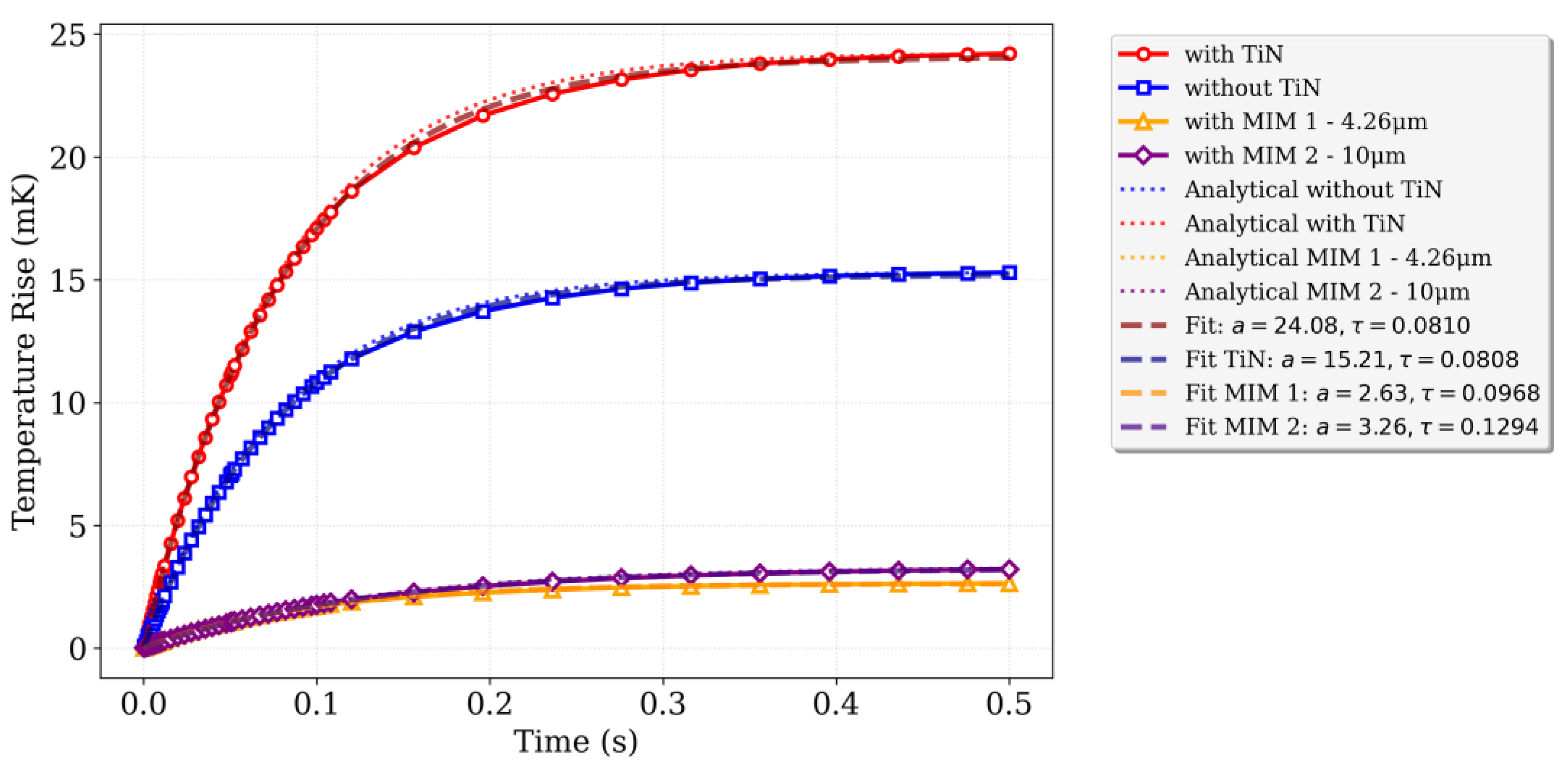

Thermal FEA confirms the TMOS sensor’s high thermal isolation, maximizing temperature rise (ΔT) for a given IR flux (

Section 4). Metasurface integration, however, increases thermal capacitance, extending the thermal time constant from 80 ms (TiN) to 95 ms (MIM 1) and 129 ms (MIM 2). While suitable for optical gas sensing, this may limit temporal bandwidth in fast-detection scenarios, necessitating careful absorber optimization. A key advancement is the analytical lumped-element RC circuit model, which exhibits excellent agreement with 3D FEA (e.g., 78.93 ms vs. 80.80 ms for TiN) (

Section 4.3). This model enables rapid evaluation of diverse layer and Metasurface absorber structures—narrowband, broadband, or multilayer—without the computational overhead of full 3D FEA simulations, which are significantly more resource-intensive [

34]. Mechanically, modal and harmonic analyses verify structural resilience, with natural frequencies remaining above 20 kHz despite Metasurface mass loading (e.g., 31.03 kHz to 24.88 kHz for MIM 2) (

Section 5.2), ensuring stability against environmental vibrations (<1 kHz).

This integrated framework advances beyond isolated domain analyses, providing a predictive tool to navigate trade-offs in absorption efficiency, thermal response, and mechanical stability. The RC circuit model’s computational efficiency facilitates rapid design iterations, enabling optimization of any absorber architecture for CMOS-compatible IR sensors. This versatility supports applications from gas sensing to biomedical diagnostics. Future work will focus on experimental validation with fabricated prototypes to refine model accuracy and explore control strategies to mitigate ambient temperature drifts, further enhancing manufacturability and performance.

7. Conclusions

This work has presented a comprehensive multiphysics modeling framework for CMOS-SOI-MEMS thermal infrared sensors integrated with Metasurface absorbers. By coupling optical, thermal, and mechanical analyses, the framework provides a predictive and quantitative approach for optimizing sensor performance across interdependent domains.

Optical simulations using the FDTD method demonstrated that Metasurface absorbers can achieve near-unity absorption at specific wavelengths, such as 4.26 µm for CO₂ detection and 10 µm for broadband thermal imaging, while maintaining CMOS process compatibility. Thermal FEA confirmed that the TMOS structure offers excellent thermal isolation and responsivity, though Metasurface integration increases thermal capacitance and extends the time constant. The validated analytical RC model effectively reproduces full 3D FEA results, enabling rapid evaluation of absorber geometries and materials with minimal computational cost. Mechanical modal and harmonic analyses verified that the device maintains sufficient stiffness and stability, with all natural frequencies well above environmental vibration ranges.

Overall, the developed framework unifies optical absorption design, thermal performance assessment, and mechanical reliability evaluation within a single simulation environment. This approach not only accelerates design iterations but also clarifies trade-offs between responsivity, speed, and structural integrity. The presented methodology can be extended to a wide range of uncooled IR detector architectures and Metasurface configurations. Future research will focus on experimental validation through fabricated prototypes and the integration of temperature compensation and feedback mechanisms to further enhance accuracy and robustness in real-world sensing applications.

Figure 1.

Multiphysics modeling framework for the CMOS-SOI-MEMS thermal IR sensor. (a) The sequential coupling of optical absorption efficiency and thermal domains: Optical FDTD Simulation computes the absorbed optical power, which is used as the heat source input for the Thermal FEA Simulation to determine the pixel’s thermal sensitivity. (b) Equivalent circuit model illustrating thermal dynamics, where the calculated thermal conductance and thermal capacitance are represented by an RC circuit driven by the theoretically absorbed optical power.

Figure 1.

Multiphysics modeling framework for the CMOS-SOI-MEMS thermal IR sensor. (a) The sequential coupling of optical absorption efficiency and thermal domains: Optical FDTD Simulation computes the absorbed optical power, which is used as the heat source input for the Thermal FEA Simulation to determine the pixel’s thermal sensitivity. (b) Equivalent circuit model illustrating thermal dynamics, where the calculated thermal conductance and thermal capacitance are represented by an RC circuit driven by the theoretically absorbed optical power.

Figure 2.

Schematic TMOS sensor (a) 3D schematic; (b) cross-section of a wafer-level processed (WLP) TMOS sensor array.

Figure 2.

Schematic TMOS sensor (a) 3D schematic; (b) cross-section of a wafer-level processed (WLP) TMOS sensor array.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Metasurface absorber unit cell configurations integrated into the TMOS sensor. (a) Configuration 1: MIM structure for absorption at 4.26 µm. (b) Configuration 2: MIM structure for absorption at 10 µm. Layer materials, thicknesses, and unit-cell dimensions are indicated (in µm).

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Metasurface absorber unit cell configurations integrated into the TMOS sensor. (a) Configuration 1: MIM structure for absorption at 4.26 µm. (b) Configuration 2: MIM structure for absorption at 10 µm. Layer materials, thicknesses, and unit-cell dimensions are indicated (in µm).

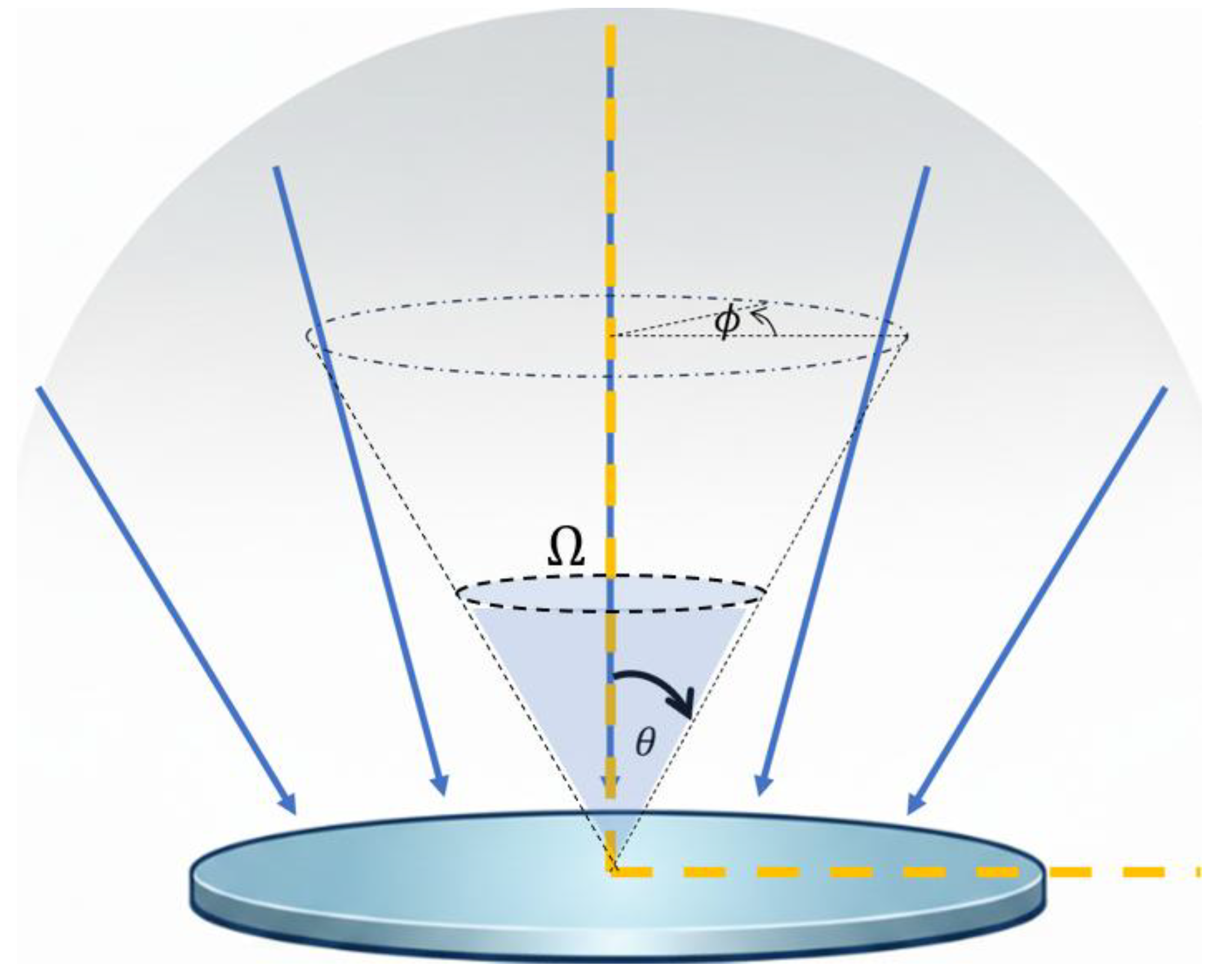

Figure 4.

Collection cone of the TMOS sensor’s optical system. Incident radiation arrives within a solid angle defined by polar and azimuthal angles, with spectral irradiance.

Figure 4.

Collection cone of the TMOS sensor’s optical system. Incident radiation arrives within a solid angle defined by polar and azimuthal angles, with spectral irradiance.

Figure 5.

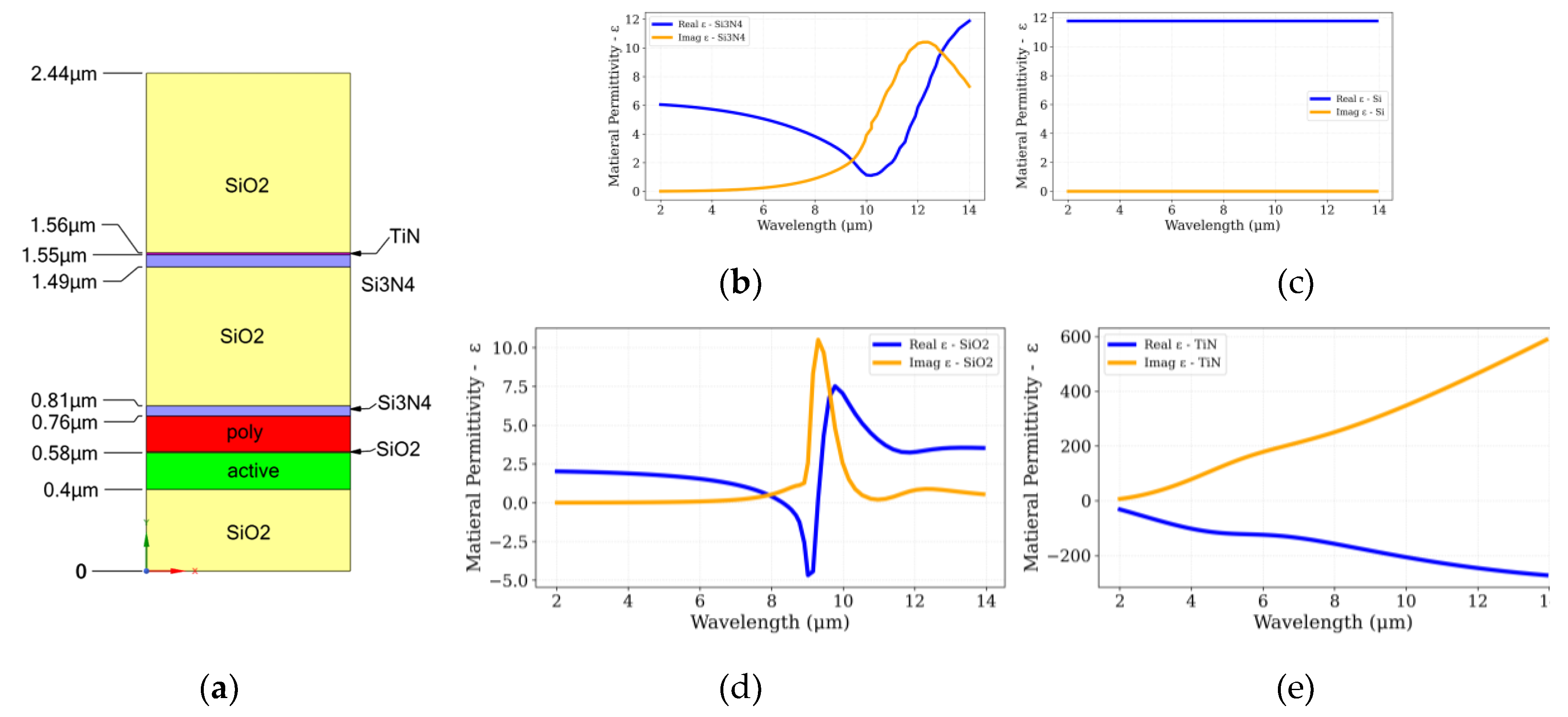

(a) Cross-sectional schematic of the CMOS-SOI multilayer stack used in the optical simulations, including Si, SiO₂, Si₃N₄, and an embedded TiN layer. (b–e) Wavelength-dependent complex permittivity, ε(λ) = Re(ε) + i·Im(ε), for the materials comprising the stack: (b) silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), (c) silicon (Si), (d) silicon dioxide (SiO₂), and (e) titanium nitride (TiN). The real part of the permittivity (blue lines) indicates refractive and dispersive properties, while the imaginary part (orange lines) highlights absorption characteristics critical to mid-infrared performance.

Figure 5.

(a) Cross-sectional schematic of the CMOS-SOI multilayer stack used in the optical simulations, including Si, SiO₂, Si₃N₄, and an embedded TiN layer. (b–e) Wavelength-dependent complex permittivity, ε(λ) = Re(ε) + i·Im(ε), for the materials comprising the stack: (b) silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), (c) silicon (Si), (d) silicon dioxide (SiO₂), and (e) titanium nitride (TiN). The real part of the permittivity (blue lines) indicates refractive and dispersive properties, while the imaginary part (orange lines) highlights absorption characteristics critical to mid-infrared performance.

Figure 6.

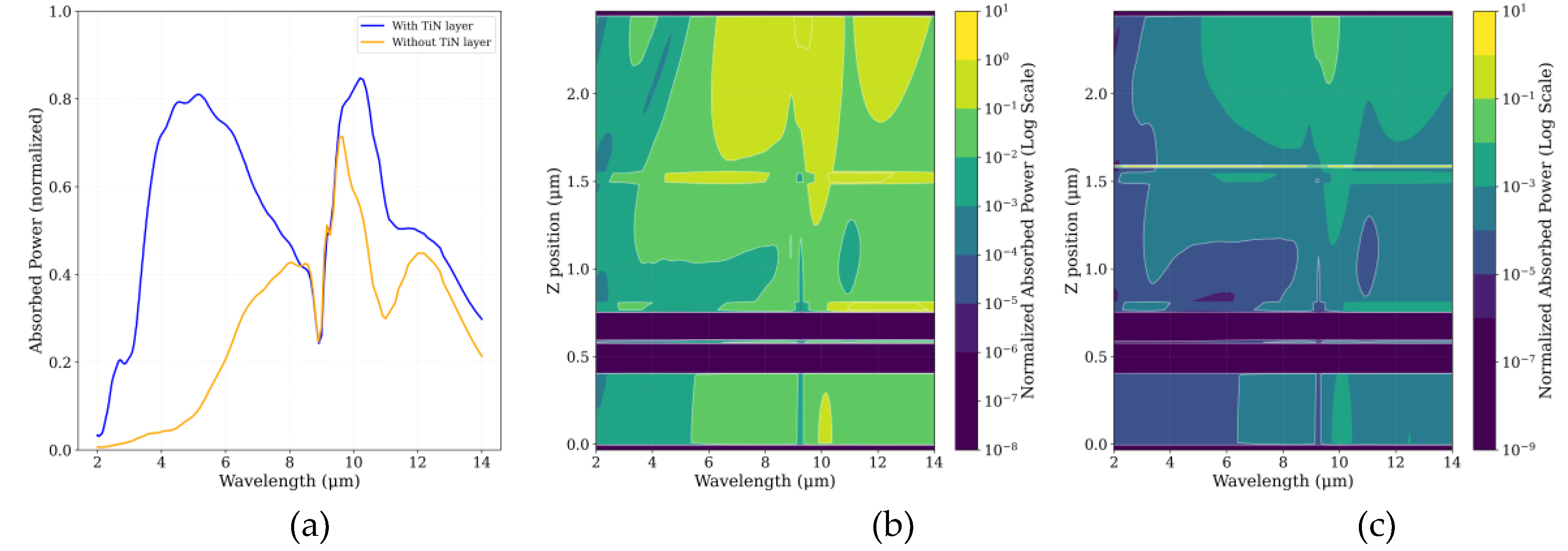

Role of Layer in Mid-Infrared Absorption Enhancement and Confinement. (a) Simulated normalized absorbed power versus wavelength. The inclusion of the embedded TiN (blue curve) yields a substantial and broadband enhancement of absorption across the entire mid-infrared spectrum, greatly surpassing the performance of the structure without the layer (orange curve). (b, c) Normalized absorbed power maps (Log Scale) across the detector cross-section, without (b) and with (c) the layer. Notably, the silicon substrate (deep blue/purple regions) exhibits negligible absorption, confirming its optical transparency in the studied IR range and the necessity of highly absorptive elements in the stage layers. The TiN layer in (c) is shown to induce strong field confinement and localized absorption, primarily within the active dielectric stack, validating its role as an effective, integrated light-trapping medium to compensate for the non-absorbing substrate.

Figure 6.

Role of Layer in Mid-Infrared Absorption Enhancement and Confinement. (a) Simulated normalized absorbed power versus wavelength. The inclusion of the embedded TiN (blue curve) yields a substantial and broadband enhancement of absorption across the entire mid-infrared spectrum, greatly surpassing the performance of the structure without the layer (orange curve). (b, c) Normalized absorbed power maps (Log Scale) across the detector cross-section, without (b) and with (c) the layer. Notably, the silicon substrate (deep blue/purple regions) exhibits negligible absorption, confirming its optical transparency in the studied IR range and the necessity of highly absorptive elements in the stage layers. The TiN layer in (c) is shown to induce strong field confinement and localized absorption, primarily within the active dielectric stack, validating its role as an effective, integrated light-trapping medium to compensate for the non-absorbing substrate.

Figure 7.

Simulated spectral optical efficiency response showing the normalized absorbed power as a function of wavelength.

Figure 7.

Simulated spectral optical efficiency response showing the normalized absorbed power as a function of wavelength.

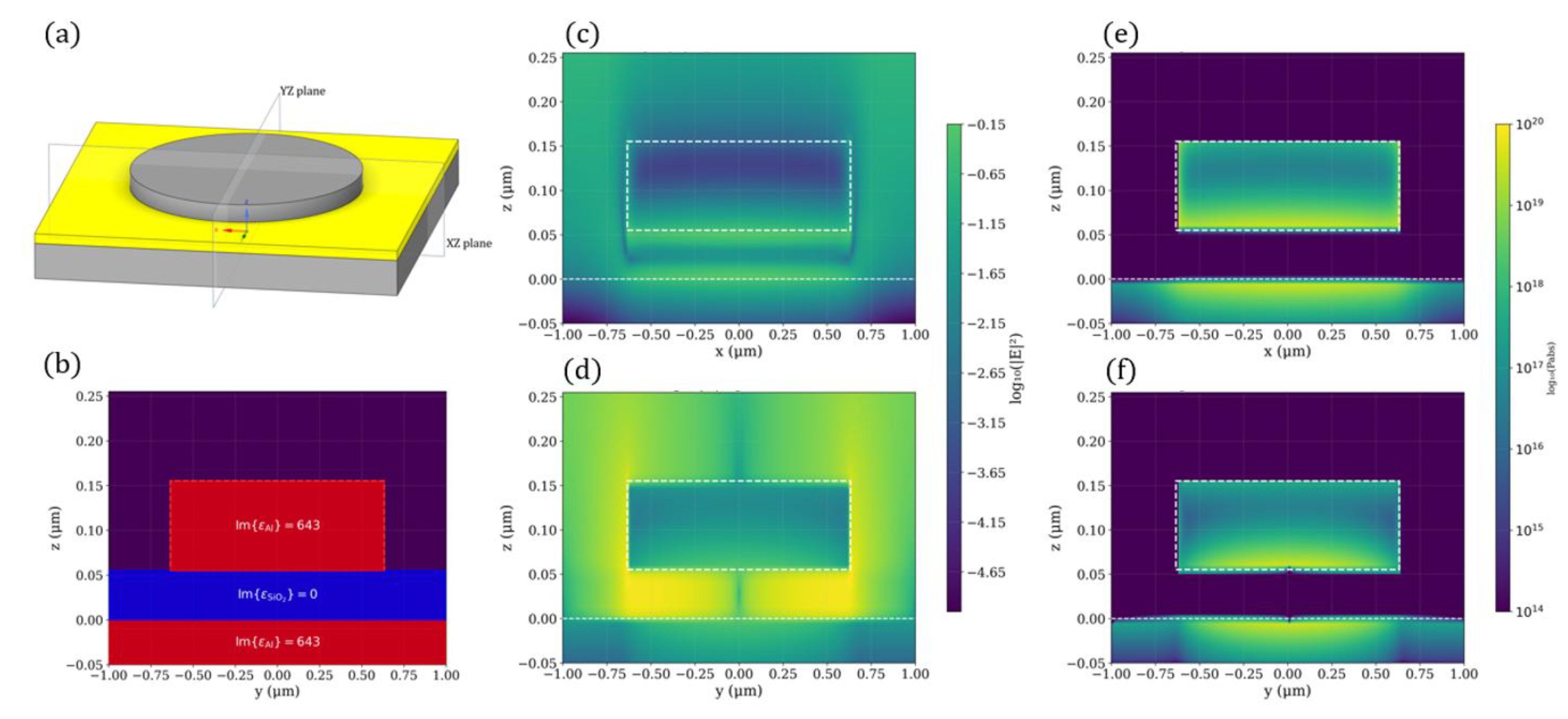

Figure 8.

Optical response and field distributions of the MIM metasurface at the peak absorption wavelength of 4.26 µm. (a) Three-dimensional schematic of the MIM unit cell, indicating the cross-sectional XZ and YZ planes used for field analysis; (b) Cross-sectional distribution of the imaginary part of the permittivity in the YZ plane, showing the layered configuration comprising the resonator (top), spacer (middle), and ground plane (bottom); (c–d) Electric field intensity distributions in the XZ (c) and YZ (d) planes, demonstrating strong field confinement within the resonant cavity; (e–f) Absorbed optical power distributions in the XZ (e) and YZ (f) planes, illustrating regions of maximum photon-to-heat conversion localized mainly within the metallic layers.

Figure 8.

Optical response and field distributions of the MIM metasurface at the peak absorption wavelength of 4.26 µm. (a) Three-dimensional schematic of the MIM unit cell, indicating the cross-sectional XZ and YZ planes used for field analysis; (b) Cross-sectional distribution of the imaginary part of the permittivity in the YZ plane, showing the layered configuration comprising the resonator (top), spacer (middle), and ground plane (bottom); (c–d) Electric field intensity distributions in the XZ (c) and YZ (d) planes, demonstrating strong field confinement within the resonant cavity; (e–f) Absorbed optical power distributions in the XZ (e) and YZ (f) planes, illustrating regions of maximum photon-to-heat conversion localized mainly within the metallic layers.

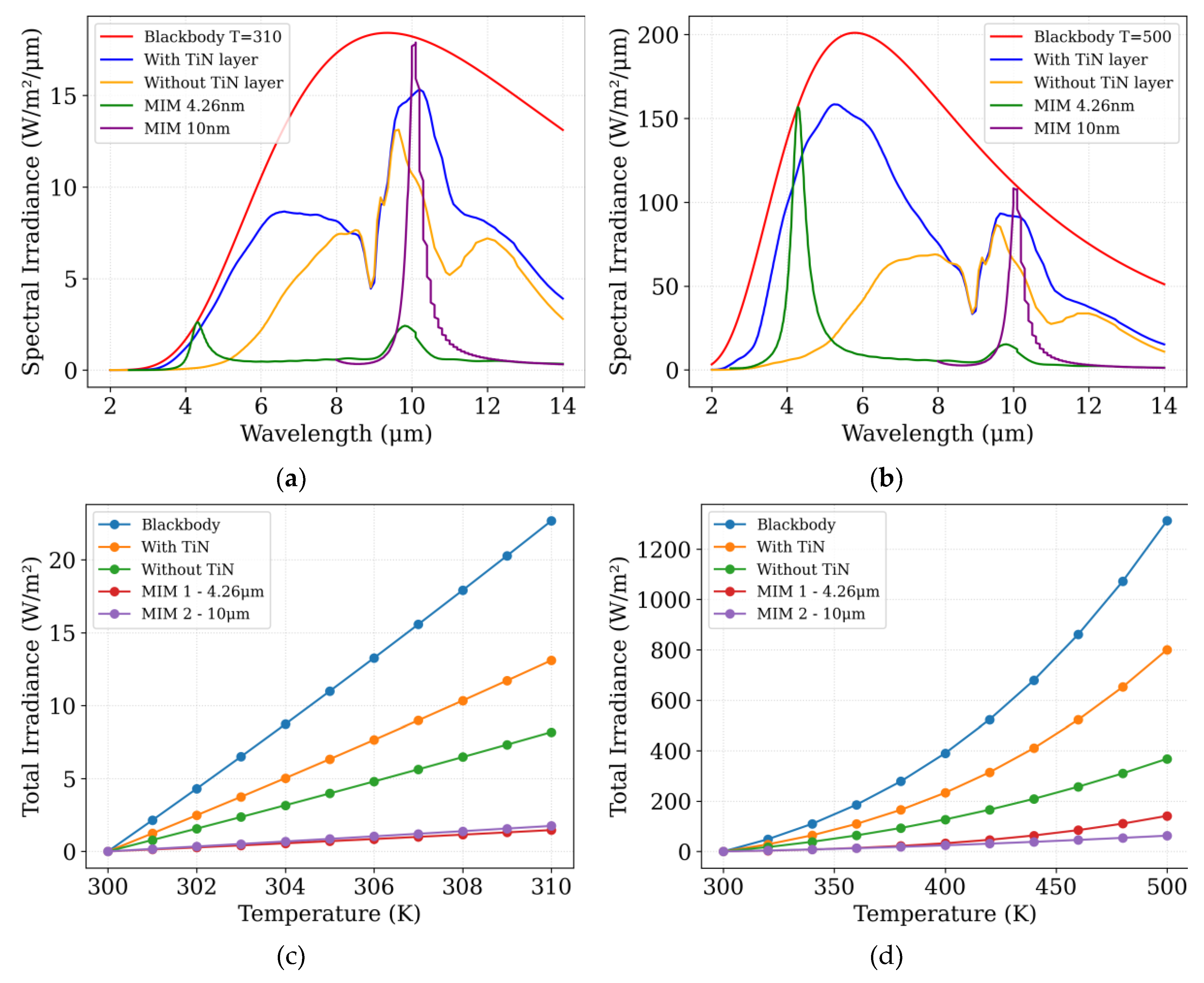

Figure 9.

Schematic Spectral and total irradiance incident on the sensor for different object temperatures. Panels (a) and (b) show the spectral irradiance for objects at 310 K and 500 K, respectively, while panels (c) and (d) present the total integrated irradiance for temperature ranges of 300–310 K and 300–500 K. These results highlight how both spectral content and total power incident on the sensor vary with object temperature.

Figure 9.

Schematic Spectral and total irradiance incident on the sensor for different object temperatures. Panels (a) and (b) show the spectral irradiance for objects at 310 K and 500 K, respectively, while panels (c) and (d) present the total integrated irradiance for temperature ranges of 300–310 K and 300–500 K. These results highlight how both spectral content and total power incident on the sensor vary with object temperature.

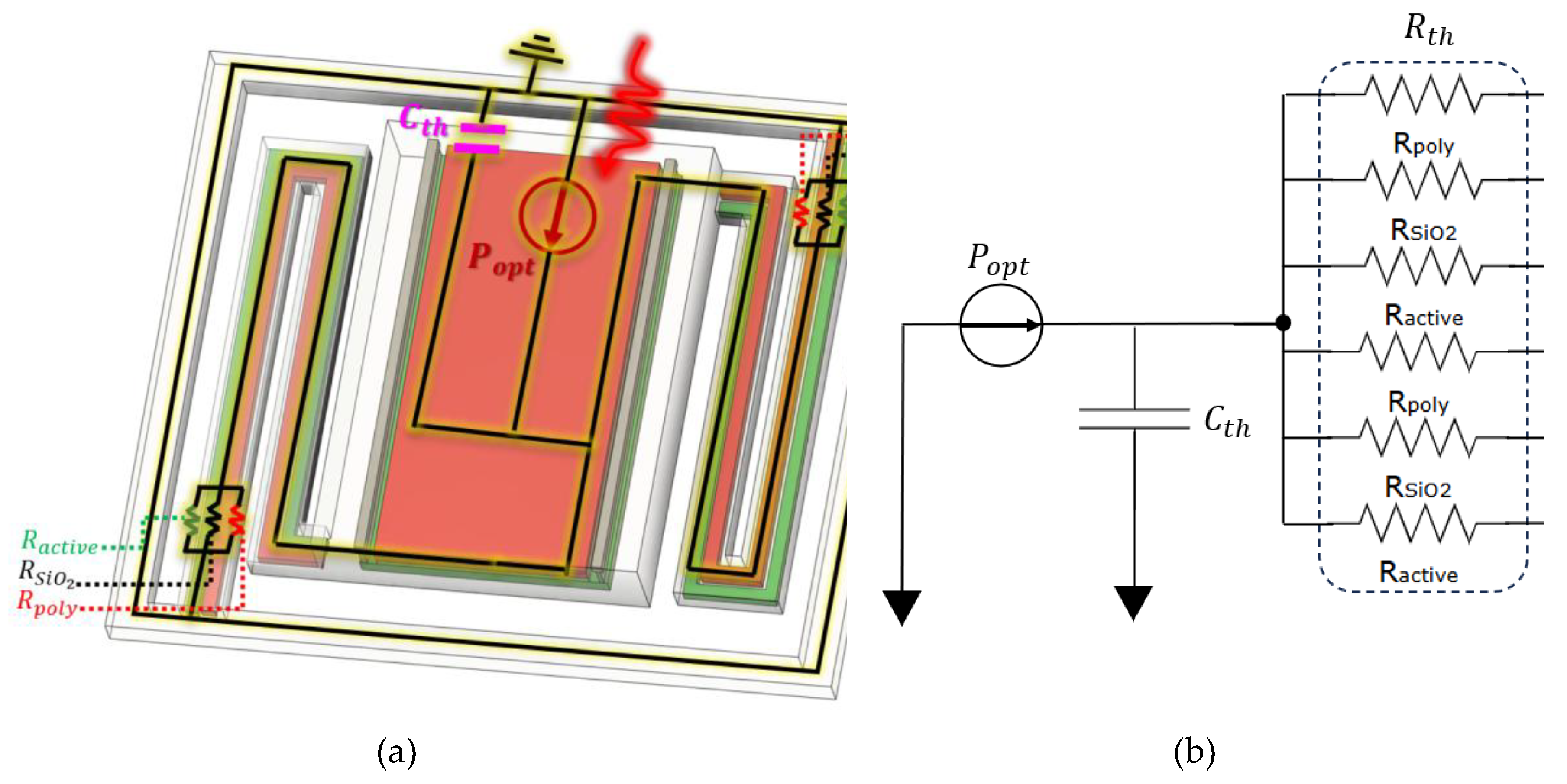

Figure 10.

Illustration of the lumped-element thermal model for the CMOS-SOI-MEMS sensor pixel: (a) 3D schematic of the sensor pixel with the stage and supporting arms, and (b) equivalent thermal circuit representation, where the stage is modeled as the dominant thermal capacitance and the arms as the primary thermal resistors.

Figure 10.

Illustration of the lumped-element thermal model for the CMOS-SOI-MEMS sensor pixel: (a) 3D schematic of the sensor pixel with the stage and supporting arms, and (b) equivalent thermal circuit representation, where the stage is modeled as the dominant thermal capacitance and the arms as the primary thermal resistors.

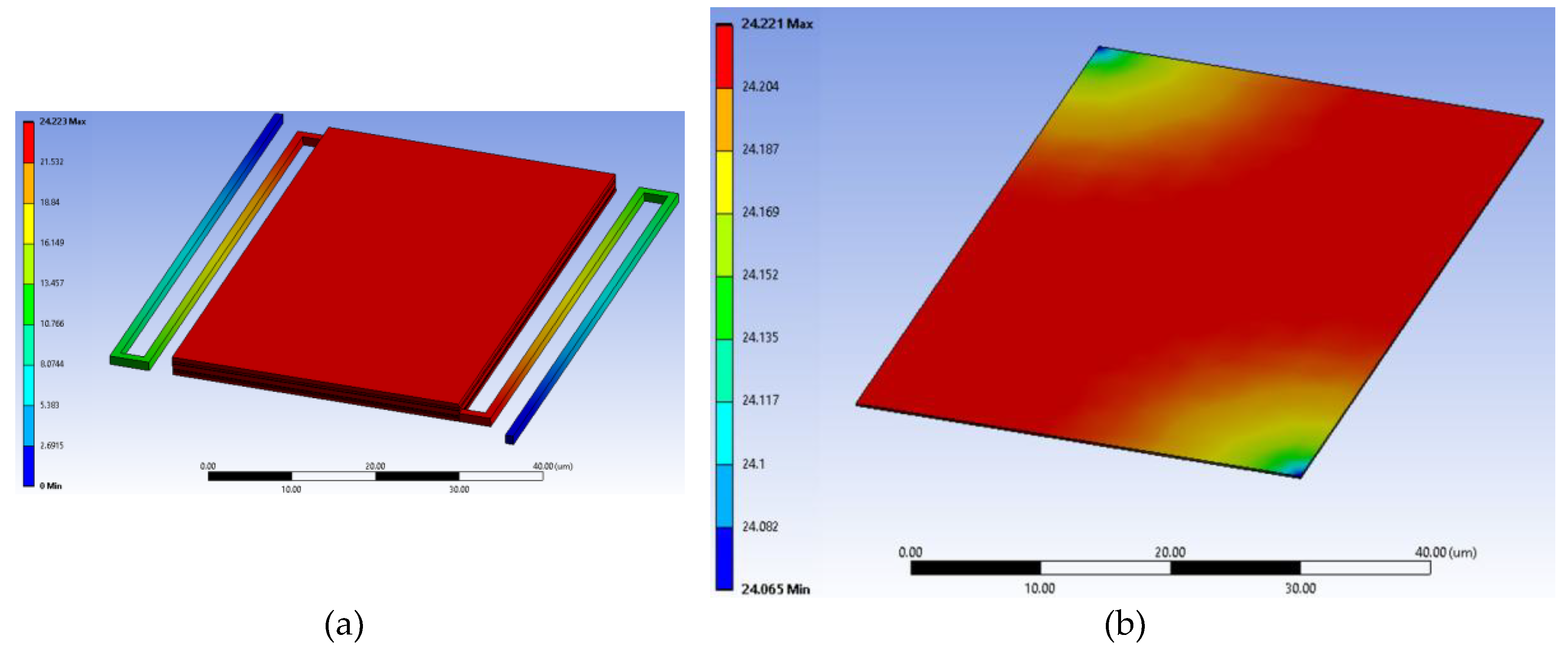

Figure 11.

Steady-state temperature rise of the CMOS-SOI-MEMS sensor pixel without MIM layers: (a) Full pixel, illustrating heat dissipation through the supporting arms. (b) Active silicon layer of the stage, highlighting the thermal uniformity. The very close limits on the color bar (Min: 24.065, Max: 24.221 mK) prove the temperature distribution is approximately uniform across the sensing area.

Figure 11.

Steady-state temperature rise of the CMOS-SOI-MEMS sensor pixel without MIM layers: (a) Full pixel, illustrating heat dissipation through the supporting arms. (b) Active silicon layer of the stage, highlighting the thermal uniformity. The very close limits on the color bar (Min: 24.065, Max: 24.221 mK) prove the temperature distribution is approximately uniform across the sensing area.

Figure 12.

Transient thermal response () of the sensor stage for different material configurations: without TiN, with TiN, with TiN and MIM configuration 1, and with TiN and MIM configuration 2. Analytical predictions from the lumped-element thermal model are included for comparison, illustrating the effects of TiN and MIM layers on the heating dynamics and validating the lumped thermal modeling approach.

Figure 12.

Transient thermal response () of the sensor stage for different material configurations: without TiN, with TiN, with TiN and MIM configuration 1, and with TiN and MIM configuration 2. Analytical predictions from the lumped-element thermal model are included for comparison, illustrating the effects of TiN and MIM layers on the heating dynamics and validating the lumped thermal modeling approach.

Figure 13.

Mechanical modeling of the suspended CMOS sensor. (a) 3D rendering of the MEMS pixel showing the suspended thermal mass and the supporting arms that provide the effective spring stiffness; (b) The equivalent single-degree-of-freedom mass-spring system, which simplifies the dynamic analysis and provides intuitive insight into the natural frequency.

Figure 13.

Mechanical modeling of the suspended CMOS sensor. (a) 3D rendering of the MEMS pixel showing the suspended thermal mass and the supporting arms that provide the effective spring stiffness; (b) The equivalent single-degree-of-freedom mass-spring system, which simplifies the dynamic analysis and provides intuitive insight into the natural frequency.

Figure 14.

FEA model of the suspended microbolometer pixel. The 3D geometry is discretized using a dense mesh for accurate mechanical simulation. Fixed support boundary conditions are applied at the anchor points where the suspending arms connect to the rigid sensor frame, simulating the physical constraints on the device.

Figure 14.

FEA model of the suspended microbolometer pixel. The 3D geometry is discretized using a dense mesh for accurate mechanical simulation. Fixed support boundary conditions are applied at the anchor points where the suspending arms connect to the rigid sensor frame, simulating the physical constraints on the device.

Figure 15.

First six vibration mode shapes of the MEMS IR sensor: (a-b) first and second modes showing out-of-plane and torsional motion of the suspended stage, (c-d) third and fourth modes with combined stage and slight arm deformation, and (e-f) fifth and sixth modes dominated by arm bending and twisting. The color scale represents displacement magnitude, with red indicating maximum displacement and blue indicating minimum displacement (fixed anchors). Note that the absolute displacement values are arbitrary and serve only to visualize the mode shapes; the modal analysis extracts the natural frequencies and relative deformation patterns under the assumption of linear elastic behavior and small displacements.

Figure 15.

First six vibration mode shapes of the MEMS IR sensor: (a-b) first and second modes showing out-of-plane and torsional motion of the suspended stage, (c-d) third and fourth modes with combined stage and slight arm deformation, and (e-f) fifth and sixth modes dominated by arm bending and twisting. The color scale represents displacement magnitude, with red indicating maximum displacement and blue indicating minimum displacement (fixed anchors). Note that the absolute displacement values are arbitrary and serve only to visualize the mode shapes; the modal analysis extracts the natural frequencies and relative deformation patterns under the assumption of linear elastic behavior and small displacements.

| |

(kHz) |

(kHz) |

(kHz)

|

(kHz)

|

(kHz)

|

(kHz)

|

| Without MIM |

31.029 |

34.276 |

191.61 |

220.22 |

305.33 |

306.52 |

| With MIM 1 |

28.87 |

31.89 |

183.79 |

213.17 |

305.35 |

306.38 |

| With MIM 2 |

24.878 |

27.478 |

167.05 |

197.21 |

305.38 |

306.14 |

Figure 16.

Harmonic displacement response of the MEMS thermal IR sensor for three configurations: without MIM, with MIM 1, and with MIM 2. The resonance peaks align with the modal frequencies reported in

Table 3, showing the expected downward frequency shift with increasing MIM thickness and a moderate reduction in peak amplitude due to the added mass loading.

Figure 16.

Harmonic displacement response of the MEMS thermal IR sensor for three configurations: without MIM, with MIM 1, and with MIM 2. The resonance peaks align with the modal frequencies reported in

Table 3, showing the expected downward frequency shift with increasing MIM thickness and a moderate reduction in peak amplitude due to the added mass loading.

Table 1.

physical and thermal properties of the sensor materials.

Table 1.

physical and thermal properties of the sensor materials.

| |

Silicon |

Silicon Nitride |

Silicon

Dioxide |

Aluminum |

Thin Silicon layers and

Polysilicon |

Titanium

Nitride |

|

2320 |

3200 |

2200 |

2689 |

2320 |

5210 |

|

|

140 |

25 |

1.4 |

237.5 |

40 |

29.1 |

|

700 |

700 |

730 |

951 |

678 |

586 |

Table 2.

mechanical properties of the sensor materials.

Table 2.

mechanical properties of the sensor materials.

| |

Silicon |

Silicon Nitride |

Silicon

Dioxide |

Aluminum |

Titanium

Nitride |

|

160 |

250 |

70 |

70 |

250 |

|

0.22 |

0.27 |

0.17 |

0.33 |

0.22 |

Table 3.

First six natural frequencies of the MEMS thermal IR sensor.

Table 3.

First six natural frequencies of the MEMS thermal IR sensor.

| |

(kHz) |

(kHz) |

(kHz)

|

(kHz)

|

(kHz)

|

(kHz)

|

| Without MIM |

31.029 |

34.276 |

191.61 |

220.22 |

305.33 |

306.52 |

| With MIM 1 |

28.87 |

31.89 |

183.79 |

213.17 |

305.35 |

306.38 |

| With MIM 2 |

24.878 |

27.478 |

167.05 |

197.21 |

305.38 |

306.14 |