Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

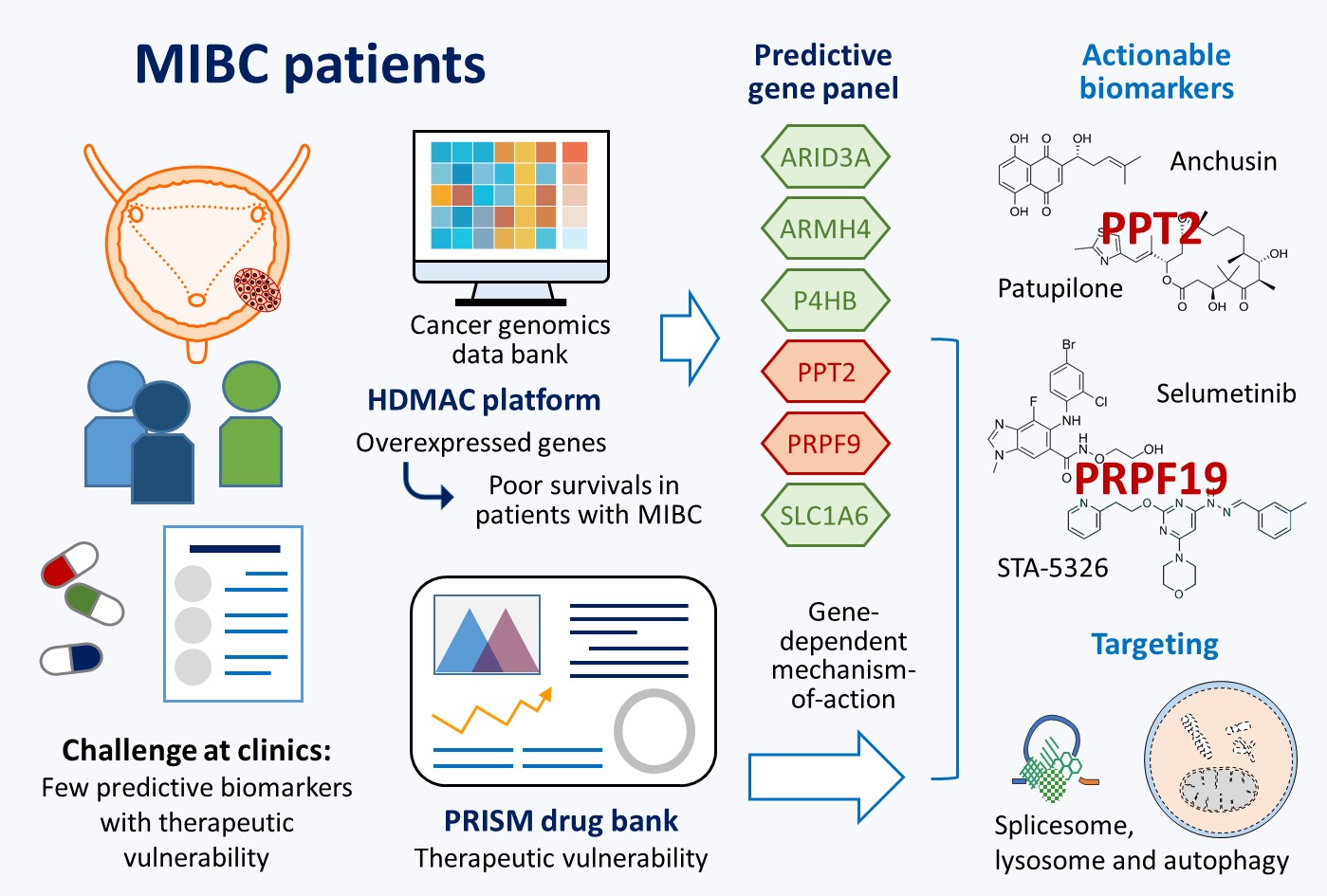

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

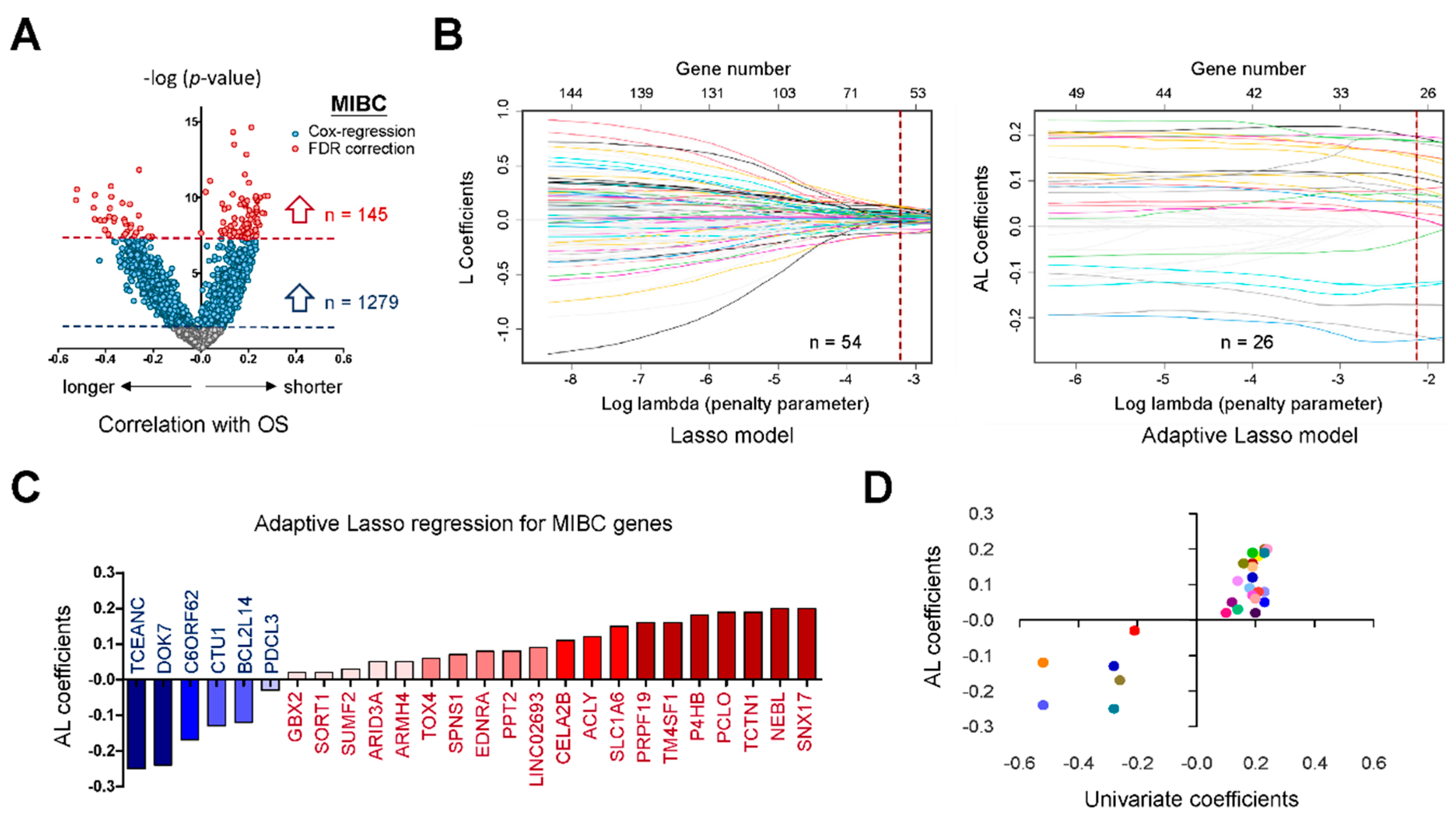

2.1. Potential Biomarkers for Aggressive MIBC Based on HDMAC Analysis

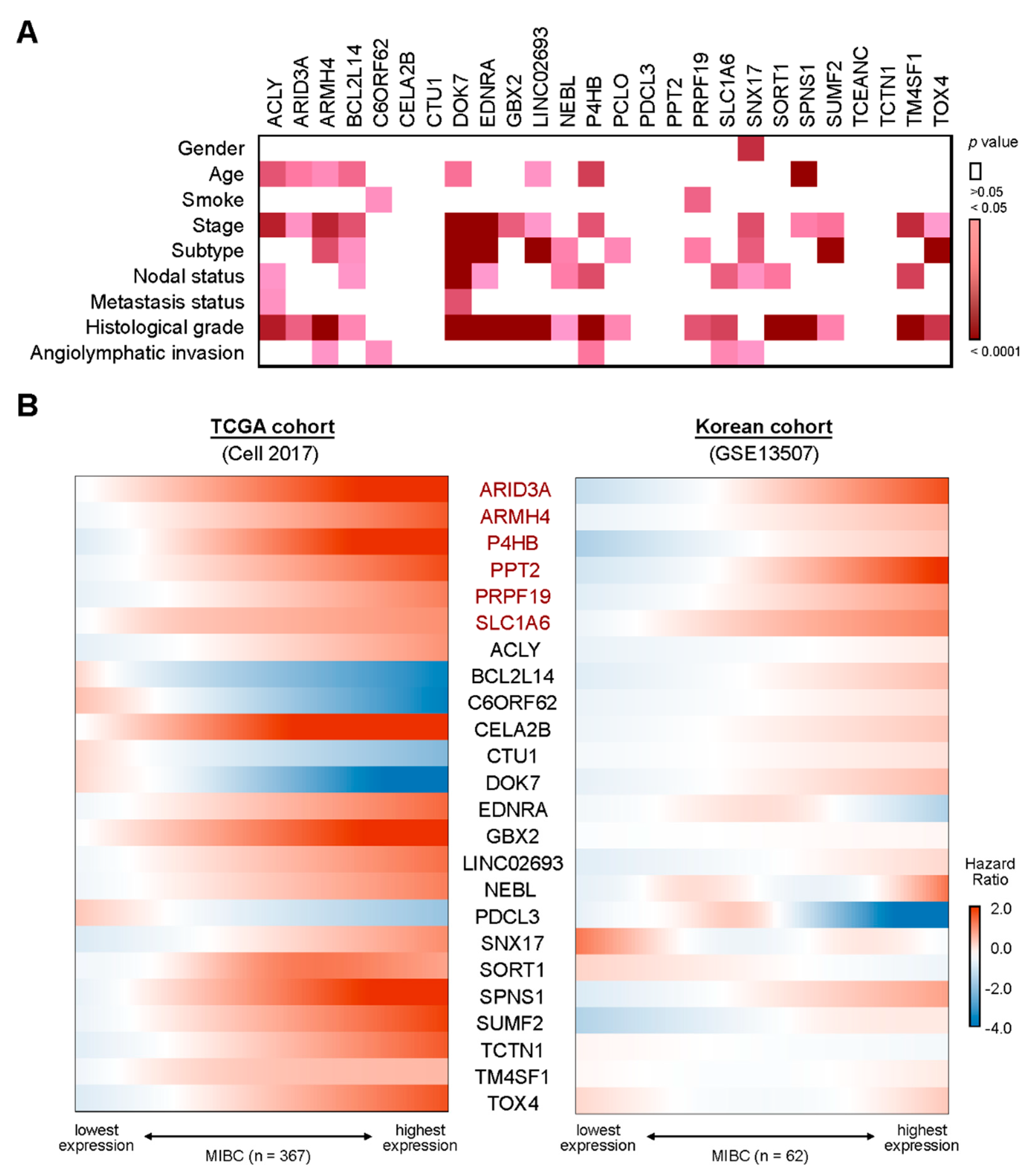

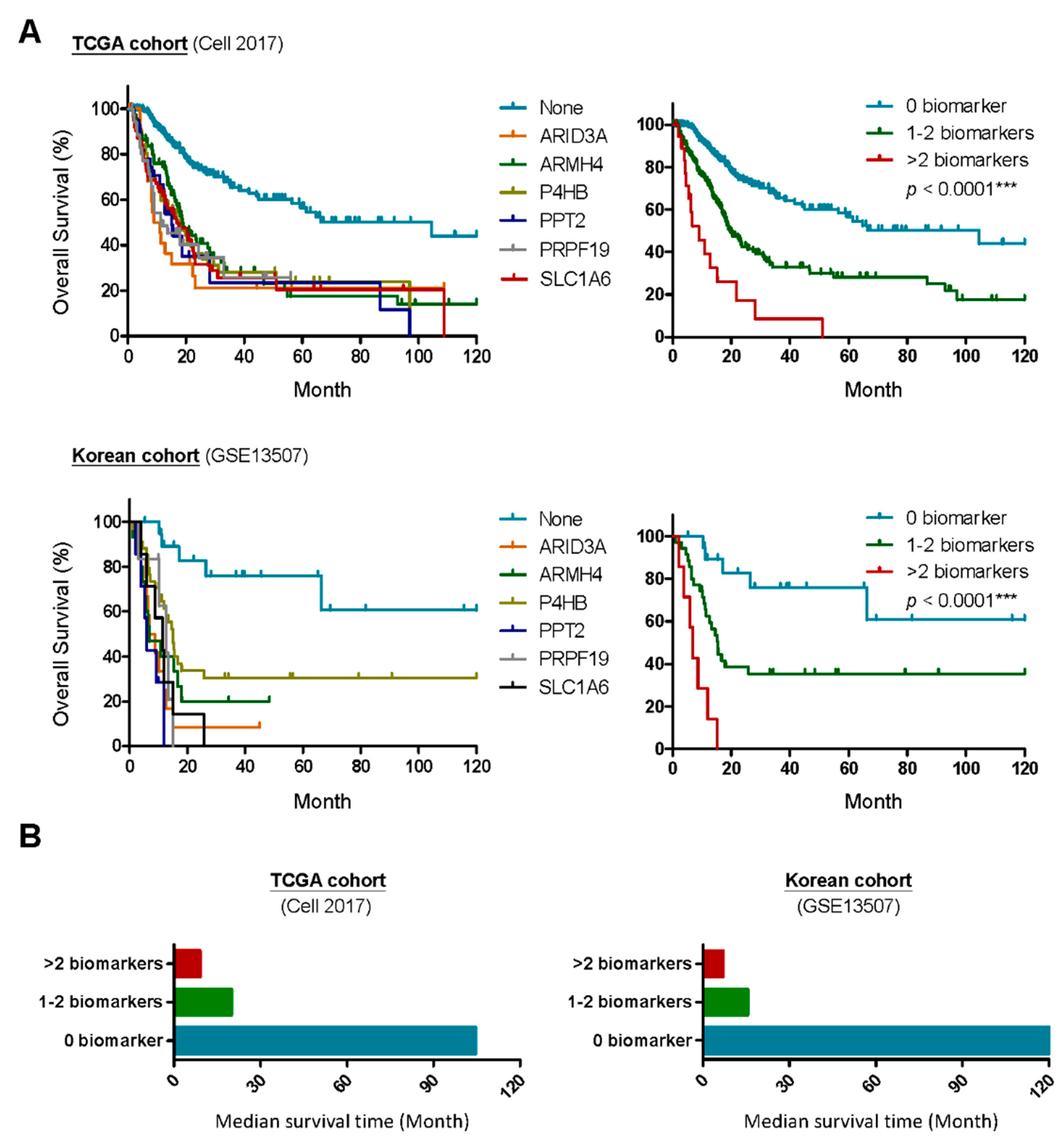

2.2. A Six-Gene Panel Serves as Novel Biomarkers for Predicting Poor Clinical Outcomes in Patients with MIBC

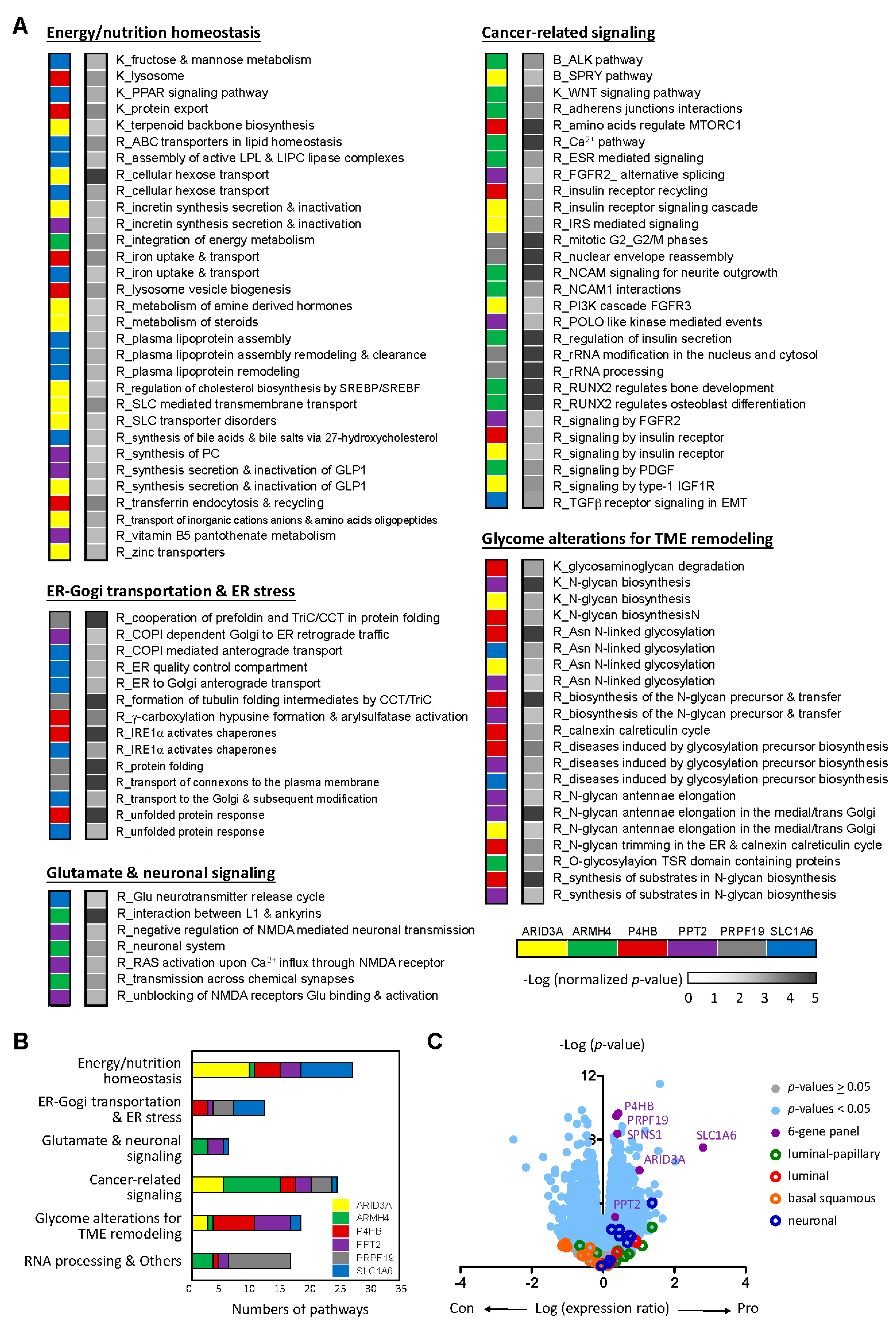

2.3. The Six-Gene Panel Shares Common Functional Features/Pathways

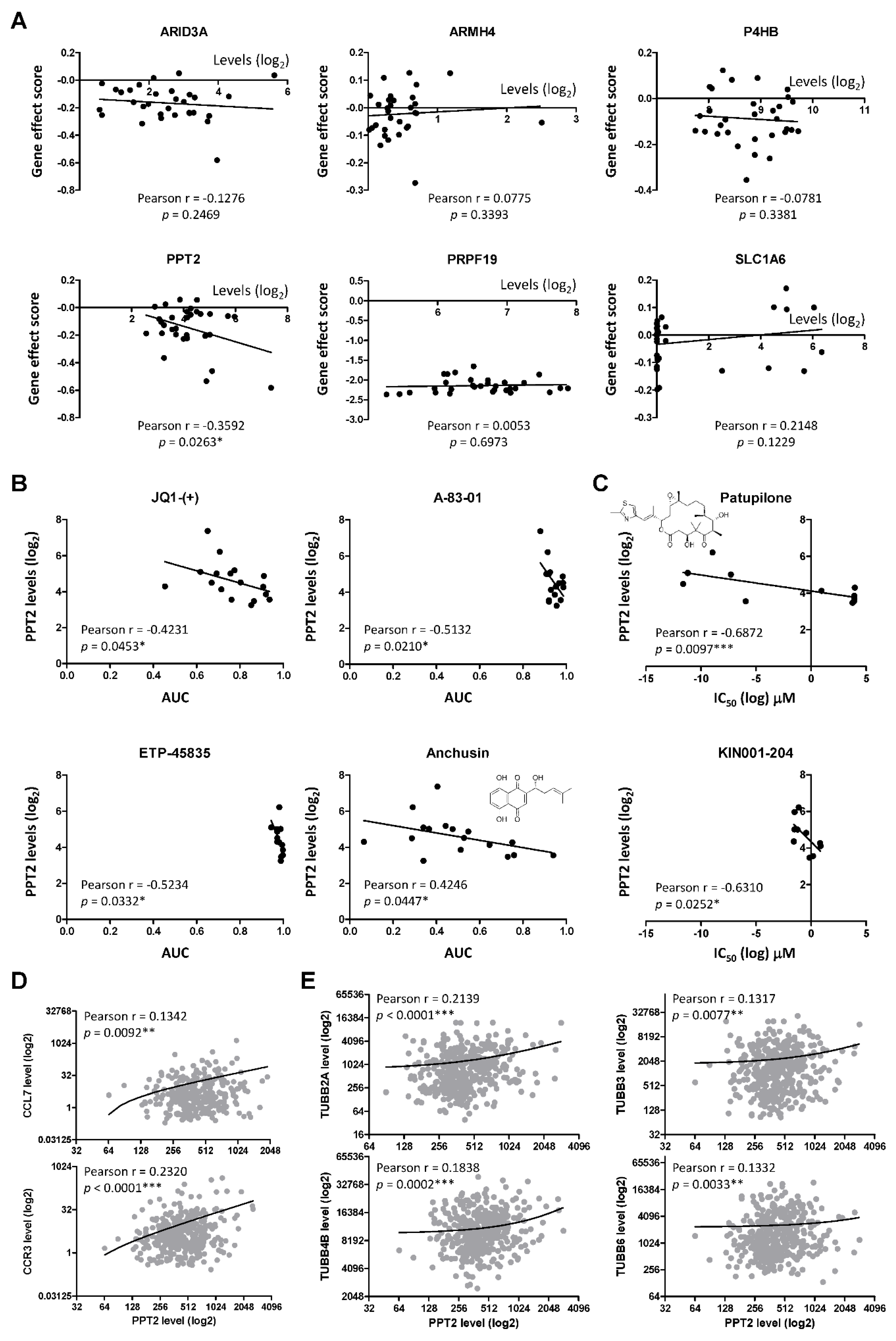

2.4. PPT2 Levels Determine Vulnerabilities of Cancer Cells

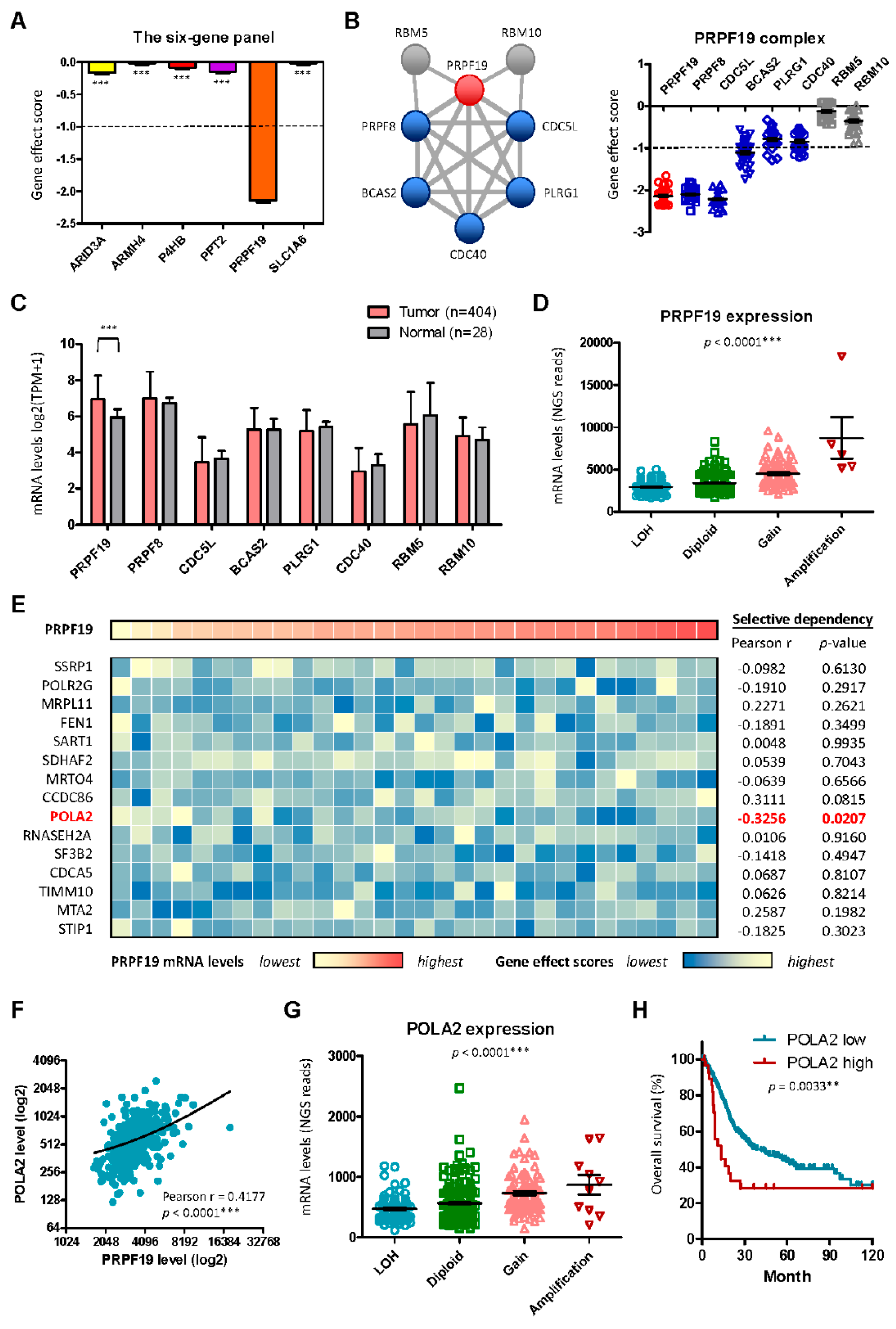

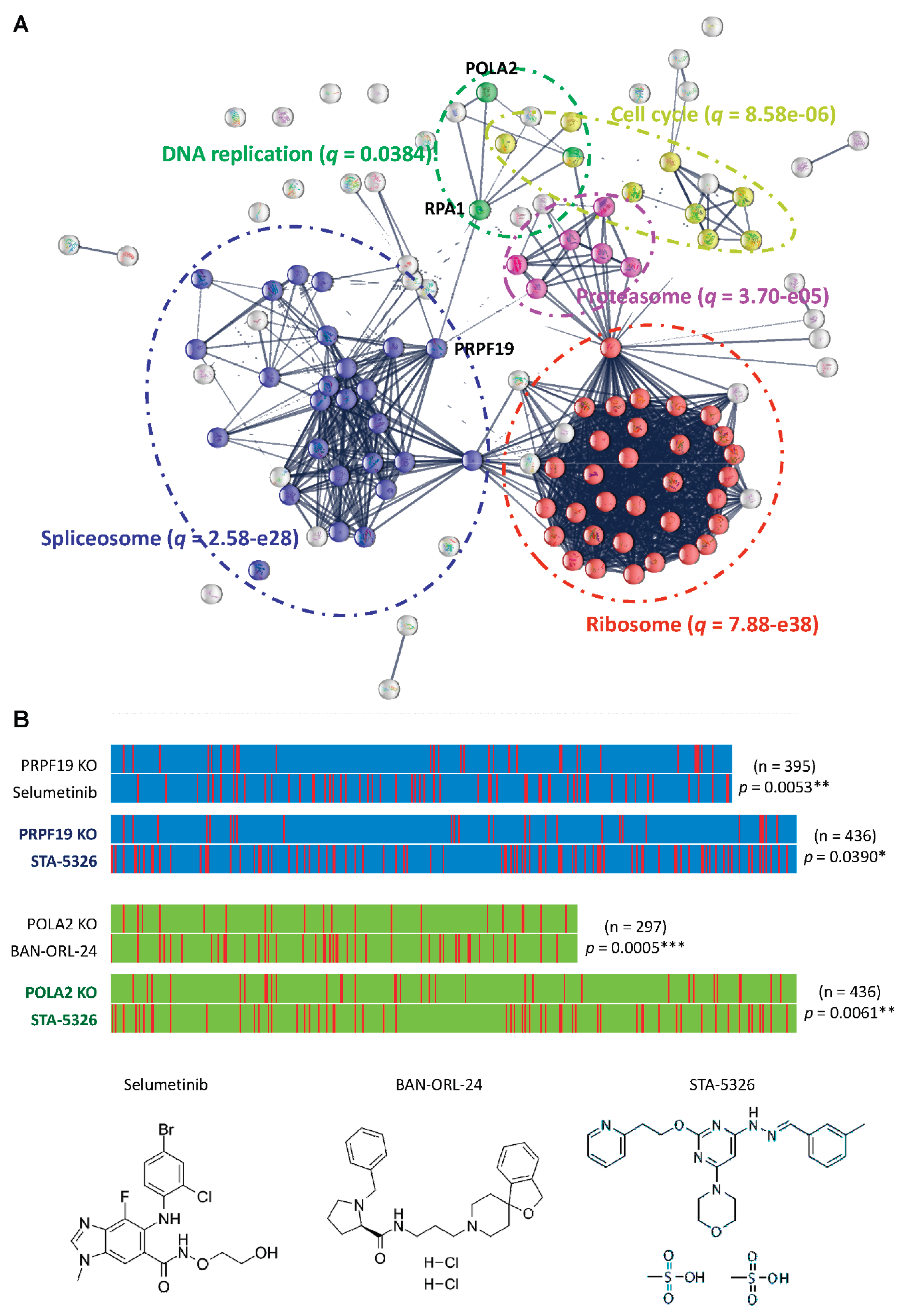

2.5. PRPF19 and Its Network Is a Potent Target for Treating Aggressive MIBC

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Gene Expression Data

4.2. Potential Biomarkers for Aggressive MIBC Based on HDMAC Analysis

4.3. Clinical Association Study and Statistical Analyses

4.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

4.5. Gene-Dependent Cell Vulnerabilities

4.6. High-Content Drug Screening

4.7. Drug Screening by Mechanism-of-Action Matching

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMIBC | Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer |

| MIBC | Muscle invasive bladder cancer |

| TURBT | Transurethral resection of bladder tumor |

| BCG | Bacillus-Calmette-Guerin |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| HDMAC | High-dimensional analysis of molecular alterations in cancer |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, S.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Znaor, A.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Overview and Recent Trends. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clin, B.; "RecoCancerProf" Working Group; Pairon, J. C. Medical follow-up for workers exposed to bladder carcinogens: the French evidence-based and pragmatic statement. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecca, C.; Abdeljalil, O.; Sridhar, S.S. Metastatic Urothelial Cancer: a rapidly changing treatment landscape. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2021, 13, 17588359211047352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audisio, A.; Buttigliero, C.; Delcuratolo, M.D.; Parlagreco, E.; Audisio, M.; Ungaro, A.; Stefano, R.F.D.; Prima, L.D.; Turco, F.; Tucci, M. New Perspectives in the Medical Treatment of Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Beyond. Cells 2022, 11, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reulen, R.C.; Kellen, E.; Buntinx, F.; Brinkman, M.; Zeegers, M.P. A meta-analysis on the association between bladder cancer and occupation. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl. 2008, 218, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouanne, M.; Bajorin, D.F.; Hannan, R.; Galsky, M.D.; Williams, S.B.; Necchi, A.; Sharma, P.; Powles, T. Rationale and Outcomes for Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 3, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Ou, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Yu, A.; Rui Cao; Zhang, E. ; et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and combination therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A multi-center real-world retrospective study. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.G.; Oh, W.K.; Galsky, M.D. Treatment of muscle-invasive and advanced bladder cancer in 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 404–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Loriot, Y.; Durán, I.; Ravaud, A.; Retz, M.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Nelson, B.; Wang, J.; Shen, X.; Powles, T. Atezolizumab Versus Chemotherapy in Patients with Platinum-treated Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Long-term Overall Survival and Safety Update from the Phase 3 IMvigor211 Clinical Trial. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamias, A.; Merseburger, A.; Loriot, Y.; James, N.; Choy, E.; Castellano, D.; Lopez-Rios, F.; Calabrò, F.; Kramer, M.; de Velasco, G.; et al. New prognostic model in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with second-line immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Leem, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.C.; Park, E.S.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.J.; Chu, I.S. Expression signature of E2F1 and its associated genes predict superficial to invasive progression of bladder tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2660–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödahl, G.; Eriksson, P.; Liedberg, F.; Höglund, M. Molecular classification of urothelial carcinoma: global mRNA classification versus tumour-cell phenotype classification. J. Pathol. 2017, 242, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.G.; Kim, J.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Bellmunt, J.; Guo, G.; Cherniack, A.D.; Hinoue, T.; Laird, P.W.; Hoadley, K.A.; Akbani, R.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Lee,S. R.; Roh, Y.G.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, J.S.; Seol, S.Y.; Lee, H.H.; Kim, W.T.; Kim, W.J.; Heo, J.; Cha, H.J.; et al. Activation of EZH2 and SUZ12 Regulated by E2F1 Predicts the Disease Progression and Aggressive Characteristics of Bladder Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5391–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselyov, A.; Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky, S.; Vladimir Startsev, V. Key signaling pathways in the muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma: Clinical markers for disease modeling and optimized treatment. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 2562–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Cheng Yu; Chien-Feng Li; I-Hsuan Chen; Ming-Tsung Lai; Zi-Jun Lin; Praveen K Korla; Chee-Yin Chai; Grace Ko; Chih-Mei Chen; Tritium Hwang; et al. YWHAZ amplification/overexpression defines aggressive bladder cancer and contributes to chemo-/radio-resistance by suppressing caspase-mediated apoptosis. J. Pathol. 2019, 248, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Sung, C.Y.; Hsiao, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, I.S.; Kuo, W.T.; Cheng, L.F.; Korla, P.K.; Chung, M.J.; Wu, P.J.; et al. HDMAC: A Web-Based Interactive Program for High-Dimensional Analysis of Molecular Alterations in Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsello, S.M.; Nagari, R.T.; Spangler, R.D.; Rossen, J.; Kocak, M.; Bryan, J.G.; Humeidi, R.; Peck, D.; Wu, X.; Tang, A.A.; et al. Discovering the anti-cancer potential of non-oncology drugs by systematic viability profiling. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, F.; Boehm, J.S. The Cancer Dependency Map enables drug mechanism-of-action investigations. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves E; Segura-Cabrera A; Pacini C; Picco G; Behan FM; Jaaks P; Coker EA; van der Meer D; Barthorpe A; Lightfoot H; et al. Drug mechanism-of-action discovery through the integration of pharmacological and CRISPR screens. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2020, 16, e9405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.; Segura-Cabrera, A.; Pacini, C.; Picco, G.; Behan, F.M.; Jaaks, P.; Coker, E.A.; van der Meer, D.; Barthorpe, A.; Lightfoot, H.; et al. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies, J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.H.; Lu, W. Adaptive Lasso for Cox's proportional hazards model. Biometrika 2007, 94, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Generalized additive models for medical research, Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1995, 4, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Hsieh, M.K.; Chang, W.Y.; Chiang, A.J.; Chen, J. Determining the optimal number and location of cutoff points with application to data of cervical cancer. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, R.M.; Bryan, J.G.; McFarland, J.M.; Weir, B,A,; Sizemore, A. E.; Xu, H.; Dharia, N.V.; Montgomery, P.G.; Cowley, G.S. ; Pantel, S.; et al. Computational correction of copy number effect improves specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.L.; Park, J.H.; Nishidate, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Katagiri, T. Involvement of maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) in mammary carcinogenesis through interaction with Bcl-G, a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9, R17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.J.; Rolland, T.; Adelmant, G.; Xia, X.; Owen, M.S.; Dricot, A.; Zack, T. I.; Sahni, N.; Jacob, Y.; Hao, T.; et al. Systematic screening reveals a role for BRCA1 in the response to transcription-associated DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 1957–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, C.; Bai, Y.; Piao, Y.; Liu, H. DOK7 Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Breast Cancer via the PI3K/PTEN/AKT Pathway. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 4035257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Tan, Z.; Lu, W.; Guo, J.; Yu, H.; Yu, J.; Sun, C.; Qi, X.; Li, Z.; Guan, F. Quantitative glycome analysis of N-glycan patterns in bladder cancer vs normal bladder cells using an integrated strategy. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshikazu Tanaka; Tohru Yoneyama; Daisuke Noro; Kengo Imanishi; Yuta Kojima; Shingo Hatakeyama; Yuki Tobisawa; Kazuyuki Mori; Hayato Yamamoto; Atsushi Imai; et al. Aberrant N-Glycosylation Profile of Serum Immunoglobulins is a Diagnostic Biomarker of Urothelial Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista da Costa, J.; Gibb, E.A.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Liu, Y.; Oo, H.Z.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Alshalalfa, M.; Davicioni, E.; Wright, J.; Dall'Era, M.A.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Neuroendocrine-like Bladder Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3908–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, S.J.; Hong, H.K.; Lee, Y.; Oh, B.Y.; Lee, W.Y.; Cho, Y.B. Crosstalk between CCL7 and CCR3 promotes metastasis of colon cancer cells via ERK-JNK signaling pathways. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 36842–36853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S,; Perrino, S. ; Miao, X.; Lamarche-Vane, N.; Brodt, P. The chemokine CCL7 regulates invadopodia maturation and MMP-9 mediated collagen degradation in liver-metastatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2020, 483, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérar, A.; Laurent, V.; Fromont, G.; Estève, D.; Gilhodes, J.; Bonnelye, E.; Gonidec, S.L.; Valet, P.; Malavaud, B.; Reina, N.; et al. The Chemokine Receptor CCR3 Is Potentially Involved in the Homing of Prostate Cancer Cells to Bone: Implication of Bone-Marrow Adipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, C.; Dempster, J.M.; Boyle, I.; Gonçalves, E.; Najgebauer, H.; Karakoc, E.; van der Meer, D.; Barthorpe, A.; Lightfoot, H.; Jaaks, P.; et al. Integrated cross-study datasets of genetic dependencies in cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, A.; Alanis-Lobato, G.; Voigt, A.; Kathi Zarnack, K.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Beli, P.; König, J. Interaction profiling of RNA-binding ubiquitin ligases reveals a link between posttranscriptional regulation and the ubiquitin system. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissou, M.; Alexandre Maréchal, A. The PRP19 Ubiquitin Ligase, Standing at the Cross-Roads of mRNA Processing and Genome Stability. Cancers 2022, 14, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondeson, D.P.; Paolella, B.R.; Asfaw, A.; Rothberg, M.V.; Skipper, T.A.; Langan, C.; Mesa, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Surface, L.E.; Ito, K.; et al. Phosphate dysregulation via the XPR1-KIDINS220 protein complex is a therapeutic vulnerability in ovarian cancer. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calero, G.; Gupta, P.; Nonato, M.C.; Tandel, S.; Biehl, E.R.; Hofmann, S.L.; Clardy, J. The crystal structure of palmitoyl protein thioesterase-2 (PPT2) reveals the basis for divergent substrate specificities of the two lysosomal thioesterases, PPT1 and PPT2. J. Biol. Chem. 2203, 78, 37957–37964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyombo, A.A.; Yi, W.; Hofmann, S.L. Structure of the human palmitoyl-protein thioesterase-2 gene (PPT2) in the major histocompatibility complex on chromosome 6p21.3. Genomics 1999, 56, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttlin, E.L.; Bruckner, R.J.; Navarrete-Perea, J.; Cannon, J.R.; Baltier, K.; Gebreab, F.; Gygi, M.P.; Thornock, A.; Zarraga, G.; Tam, S.; et al. Dual Proteome-Scale Networks Reveal Cell-Specific Remodeling of the Human Interactome. Cell 2021, 184, 3022–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.F.; Xiong, Z.Y.; Shi, J.; Peng, J.T.; Meng, X.G.; Wang, C.; Hu, W.J.; Ru, Z.Y.; Xie, K.R.; Yang, H.M.; et al. Overexpression of PPT2 Represses the Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Progression by Reducing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havugimana, P.C.; Hart, G.T.; Nepusz, T.; Yang, H.; Turinsky, A.L.; Li, Z.; Wang, P.I.; Boutz, D.R.; Fong, V.; Phanse, S.; et al. A Census of Human Soluble Protein Complexes. Cell 2012, 150, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourreddine, S.; Lavoie, G.; Paradis, J.; Ben El Kadhi, K.; Méant, A.; Aubert, L.; Grondin, B.; Gendron, P.; Chabot, B.; Bouvier, M.; et al. NF45 and NF90 Regulate Mitotic Gene Expression by Competing with Staufen-Mediated mRNA Decay. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Xia, T.; Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Piao, H.-L.; Qi, H.; Ma, Y.; et al. Metabolomic Characterization Reveals ILF2 and ILF3 Affected Metabolic Adaptions in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 721990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, M.D.; Vander Kooi, C.W.; Rosenberg, J.A.; Ren, L.; Hirsch, J.P.; Chazin, W.J.; et al. Structural and Functional Analysis of Essential Pre-mRNA Splicing Factor Prp19p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.P.; Kao, D.I.; Tsai, W.Y.; Cheng, S.C. The Prp19p-Associated Complex in Spliceosome Activation. Science 2003, 302, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanarat, S.; Sträßer, K. Splicing and Beyond: The Many Faces of the Prp19 Complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.; Shanmugam, I.; Bsaili, M.; Hromas, R.; Shaheen, M. The Role of the Human Psoralen 4 (hPso4) Protein Complex in Replication Stress and Homologous Recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 14009–14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, K. hPso4/hPrp19: A Critical Component of DNA Repair and DNA Damage Checkpoint Complexes. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2279–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Dellago, H.; Terlecki-Zaniewicz, L.; Karbiener, M.; Weilner, S.; Hildner, F.; Grillari, J. SNEVhPrp19/hPso4 Regulates Adipogenesis of Human Adipose Stromal Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 8, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, C.; Cai, K.; Liu, P.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.I.; Ming, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xie, Q.; Xia, X.; et al. PRPF19 Promotes Tongue Cancer Growth and Chemoradiotherapy Resistance. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2021, 53, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudova, E.A.; Krasnov, G.S.; Kobelyatskaya, A.A.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Fedorova, M.S.; Pavlov, V.S.; Nyushko, K.M.; Kaprin, A.D.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Trofimov, D.Y.; et al. Gene Expression Changes and Associated Pathways Involved in the Progression of Prostate Cancer Advanced Stages. Front. Genet. 2021, 11, 613162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, T.; Berberich, A.; Sadik, A.; Sahm, F.; Gorlia, T.; Meisner, C.; Stupp, R. Methylome Analyses of Three Glioblastoma Cohorts Reveal Chemotherapy Sensitivity Markers within DDR Genes. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 8373–8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.M.; Yu, Q.; Xue, R.Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.A.; Chen, Y.J.; Liu, T.T.; Dong, L.; et al. Prp19 Facilitates Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Twist1 Pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 21939–21951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y. Proteomics-Based Identification and Analysis of Proteins Associated with Helicobacter pylori in Gastric Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Kong, N.; Ye, L.; Han, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, C.; Pan, H. p38 and JNK MAPK Pathways Control the Balance of Apoptosis and Autophagy in Response to Chemotherapeutic Agents. Cancer Lett. 2014, 344, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, G.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Jiang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Qian, G.; Wang, X. Downregulation of LAPTM5 Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Viability Inducing Cell Cycle Arrest at G0/G1 Phase of Bladder Cancer Cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 50, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell, C.E.; Vassilev, A. Combined Inhibition of p38MAPK and PIKfyve Synergistically Disrupts Autophagy to Selectively Target Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2903–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, J.-C.; Yates, M.; Gaudreau-Lapierre, A.; Clément, G.; Cappadocia, L.; Gaudreau, L.; Zou, L.; Maréchal, A. A Phosphorylation-and-Ubiquitylation Circuitry Driving ATR Activation and Homologous Recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 8859–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, A.; Li, J.M.; Ji, X.Y.; Wu, C.S.; Yazinski, S.A.; Nguyen, H.D.; Zou, L. PRP19 Transforms into a Sensor of RPA-ssDNA after DNA Damage and Drives ATR Activation via a Ubiquitin-Mediated Circuitry. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Legerski, R.J. The Prp19/Pso4 Core Complex Undergoes Ubiquitylation and Structural Alterations in Response to DNA Damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 354, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, K.N.; Mitchell, B.S. Role of Human Pso4 in Mammalian DNA Repair and Association with Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 10746–10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Røe, O.D.; Szulkin, A.; Anderssen, E.; Flatberg, A.; Sandeck, H.; Amundsen, T; Erlandsen, S. E.; n Dobra, K.; Stein Harald Sundstrøm, S.H. Molecular Resistance Fingerprint of Pemetrexed and Platinum in a Long-Term Survivor of Mesothelioma. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billich, A. Drug Evaluation: Apilimod, an Oral IL-12/IL-23 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases and Common Variable Immunodeficiency. IDrugs 2007, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Xu, Y.; Cheung, A.K.; Tomlinson, R.C.; Alcázar-Román, A.; Murphy, L.; Billich, A.; Zhang, B.; Feng, Y.; Klumpp, M.; et al. PIKfyve, a class III PI kinase, is the target of the small molecular IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor apilimod and a player in Toll-like receptor signaling. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayle, S.; Landrette, S.; Beeharry, N.; Conrad, C.; Hernandez, M.; Beckett, P.; Martin, A.; Smith, J.; Jones, K.; Lee, H.; et al. Identification of Apilimod as a First-in-Class PIKfyve Kinase Inhibitor for Treatment of B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood 2017, 129, 1768–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Guardia, C.M.; Roy, A.; Vassilev, A.; Saric, A.; Griner, L.N.; Marugan, J.; Ferrer, M.; Bonifacino, J.S.; DePamphilis, M.L. A Family of PIKFYVE Inhibitors with Therapeutic Potential Against Autophagy-Dependent Cancer Cells Disrupt Multiple Events in Lysosome Homeostasis. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1694–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alroy, J.; Gould, V.E. Epithelial-Stromal Interface in Normal and Neoplastic Human Bladder Epithelium. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1980, 1, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.E.; Liu, B.C.; Ahlering, T.; Dubeau, L.; Droller, M.J. Mechanisms of Human Bladder Tumor Invasion: Role of Protease Cathepsin B. J. Urol. 1990, 144, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Matesic, L.E. The Nedd4-Like Family of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007, 26, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, M.; Gagos, S.; Petrolekas, A.; Roubelakis, M.G.; Bitsika, V.; Stravodimos, K.; Pavlakis, K; Anagnou N. P.; Coleman, J.; Vlahou, A. Chromosomal and Proteome Analysis of a New T24-Based Cell Line Model for Aggressive Bladder Cancer. Proteomics 2009, 9, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.Y.; Wang, M.D.; Zhang, N.Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.J.; Hu, X.J.; Lv, G.T.; Wang, J.Q.; Lv, M.Y.; Yi, L.; et al. A Lysosome-Targeting Self-Condensation Prodrug-Nanoplatform System for Addressing Drug Resistance of Cancer. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3983–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldetti, S.; Zhou, Q.; Abbott, J.M.; de Jong, F.C.; Esquer, H.; Costello, J.C.; Theodorescu, D.; LaBarbera, D.V. High-Content Drug Discovery Targeting Molecular Bladder Cancer Subtypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kwiatkowski, D.; McConkey, D.J.; Meeks, J.J.; Freeman, S.S.; Bellmunt, J.; Getz, G; Seth P Lerner, S. P. The Cancer Genome Atlas Expression Subtypes Stratify Response to Checkpoint Inhibition in Advanced Urothelial Cancer and Identify a Subset of Patients with High Survival Probability. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; He, M.; Chen, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, D; Jiang, Z; Wei, Q; Qiu, S; et al. A Single-Sample mRNA Molecular Classification of Bladder Cancer Predicting Prognosis and Response to Immunotherapy. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2022, 11, 943–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todenhöfer, T.; Seiler, R. Molecular Subtypes and Response to Immunotherapy in Bladder Cancer Patients. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2019, 8, S293–S295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, S.J. Personalised Medicine for Advanced Urothelial Cancer: What is the Right Way to Identify the Right Patient for the Right Treatment? Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 965–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, P.S.; Chen, D.S. Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity 2020, 52, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Hausdorf, D.; Altan, M.; Velcheti, V.; Gettinger, S.N.; Herbst, R.S.; Rimm, D.L.; et al. Expression and Clinical Significance of PD-L1, B7-H3, B7-H4 and TILs in Human Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC). J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Toubah, T.; Cives, M.; Strosberg, J. Novel Immunotherapy Strategies for Treatment of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).